Paper Mills: An Old Crisis in Academia Made New

A recent article by Jeffrey Brainard at Science Magazine has put the spotlight on both the prominence and the role of paper mills in academic publishing.

The article highlights the work of neuropsychologist Bernhard Sabel, who screened some 5,000 neuroscience papers, finding that 34% of them were likely either made up or plagiarized from other sources. In the field of medicine, that number was 24%.

The culprit for this massive percentage of questionable papers is paper mills, companies that generate or plagiarize for academics who want or feel the need to publish papers, but don’t want to actually do the research that goes into them.

By Sabel’s admission, his tool is simplistic and is prone to a high false positive rate. However, even if half the papers are found to be false positives, that still leaves the number many times higher than the 2% estimated for most journals by the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and the International Association of Scientific, Technical, and Medical Publishers (STM).

However, while that is what the report says, COPE and STM’s message was actually more nuanced. It said, “Most journals will see 2% suspected fake papers submitted and then for journals where paper mills have been successful in getting papers accepted, they see a sharp increase in suspect submissions”

According to that report, the highest percentage is actually 46%, with an average percentage of 14%.

However, that still puts the 34% found by Brainard in a shocking light, far higher than any estimate for an average rate.

In response to this issue, the academic publishing industry is working to fight back. Twenty publishers, including Elsevier, Springer Nature, and Wiley, are working together to develop Integrity Hub, a set of tools that, among other things, is expected to help weed out essay mill papers.

Likewise, STM, which represents 120 publishers, is preparing to launch its own tool that it hopes will detect manuscripts that were sent to multiple journals, an unethical practice that is often a warning sign of a paper mill work.

But while the publishing industry is finding ways to fight back, it’s facing a foe that is both very old and very young at the same time. It’s a nimble industry that has proved, if anything, very adaptable.

Making an Old Problem New

To be clear, the problem of paper mills in academic publishing is nothing new. I covered the topic in depth in March 2021 , and highlighted that it was an issue that was being tracked as far back as 2007.

Simply put, paper mills exist in academic publishing for the exact same reason that essay mills exist in the classroom: To enable “authors” to gain the benefits of a paper without requiring them to do the work.

Both have had similar arcs. They increased rapidly as the internet grew and improved the ease of access to such mills and made it easier for would-be plagiarists to connect with inexpensive labor all over the world. Likewise, they both face existential challenges from AI, which may provide easier and cheaper ways for unethical authors to bypass the system.

However, one area where the paper mill industry has stood out has been its adaptability.

The Science Magazine article also highlighted the research of Adam Day, who owns Clear Skies , a company that offers a service named Papermill Alarm.

According to a blog post by Day , paper mills are incredibly quick to adapt and pivot. For example, when one journal was added to a Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) list of questionable journals, paper mill publications to the journal dropped to almost zero within months.

Another journal began to see a marked increase in paper mill submissions in 2021 and 2022, only to drop to almost nothing mere weeks after it was added to a CAS list.

Ironically, according to Day, the CAS lists are probably not reliable as journals featured in it likely have the fewer paper mill papers, simply because the mills have moved on.

Day does note that he does not know the criteria for the CAS and if paper mills are part of the process. That said, the impact those lists have is very clear.

But this puts academic publishing in a difficult position: How do you stop paper mills?

Fixing the Issue

Academic paper mills have a great in common with internet spammers . Since their product requires almost no work, they’re free to send out large quantities of garbage content, knowing that nearly all of it will be rejected or ignored.

Then, they simply make note of what did work and then repeat those steps until they stop working and then find new approaches.

What this means is that, even if the publishing industry manages to be 99% effective at detecting and stopping paper mill works, 1% will get through, and the mills will focus future efforts around that.

As several have described it, it’s a game of cat and mouse. Technological solutions can and should be used to mitigate the problem, but it’s not enough to actually stop it.

What has to change is the “ publish or perish ” environment many in academia work under. Such an environment puts the focus on quantity, not quality, of publications.

To that end, paper mills are just one of the symptoms of the problem. Predatory journals routinely dupe researchers into paying high open access fees for little benefit, researchers add their names to papers they had little to do with ( sometimes for a joke ) and researchers will break apart one paper into multiple smaller ones, taking up valuable publication space.

Without a change on the incentive side of research, there will be no change in all these practices. When researchers are rewarded for the quantity of their work, the quality inevitably suffers as the focus is racking up big numbers, not doing meaningful work.

Bottom Line

To be clear, there’s no simple answer here. While it’s easy for someone like me to say, “We have to fix the publish-or-perish environment,” doing so is incredibly difficult.

Gauging the quality of research is difficult and requires significant time from experts in that field. It’s much easier to look at a tally of publications and call that a “good enough” estimation of output. This is especially true for schools, where resources are often very limited.

However, it’s important to always be mindful of what our incentives are rewarding and how those incentive systems can be gamed. The current system rewards a variety of unethical behaviors, including paper mills.

If it weren’t for these incentives, paper mills wouldn’t be the multi-million dollar industry that it is today. It wouldn’t be a problem that potentially impacts 34% of neuroscience papers. It would be nothing more than an outlier, a problem that rarely comes up and is rarely discussed.

To that end, if paper mills do disappear, it won’t be because publishers beat them, it will be because AI replaced them. Simply put, there will always be journals that will publish mill papers and the paper mills will find them, through trial and error if needed.

Simply put, paper mills have been around for decades and have proven themselves resourceful and quick to pivot. That isn’t going to change any time soon.

The only thing that will change is what weaknesses they exploit…

Want to Reuse or Republish this Content?

If you want to feature this article in your site, classroom or elsewhere, just let us know! We usually grant permission within 24 hours.

Click Here to Get Permission for Free

Himmelfarb Library News

Resources, tools & health news from GW Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

A Tale of Two Publishing Models: The Impact of Paper Mills and the Guest Editor Model

Hindawi, an Open Access journal publisher once identified by Jeffrey Beall as a potentially predatory publisher and later labeled as a “borderline case” by Beall, has made great efforts to transform its reputation into that of a reputable, scholarly publisher. The publisher was purchased by Wiley in January 2021, and many hoped that the purchase would add a layer of trustworthiness and legitimacy to the once-questionable publisher’s practices. Recent developments have proved that the path toward implementing scholarly publishing best practices is a long, uphill struggle for Hindawi and Wiley.

In late March 2023, Clarivate removed 19 Hindawi journals from Web of Science when they released the monthly update of their Master Journal List . These 19 journals published 50% of articles published in Hindawi journals in 2022 (Petrou, 2023). The removal of these journals from Web of Science comes after Wiley disclosed they were suspending the publication of special issues due to “compromised articles” (Kincaid, 2023).

Web of Science dropped 50 journals from its index in March for failure to meet 24 of the quality criteria required to be included in Web of Science. Common quality violations included: adequate peer review, appropriate citations, and content that was irrelevant to the scope of the journal. The 19 Hindawi journals removed from Web of Science accounted for 38% of the total 50 journals removed from the index! Health sciences titles published by Hindawi that were removed from Web of Science include:

- Biomed Research International

- Disease Markers

- Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Journal of Environmental and Public Health

- Journal of Healthcare Engineering

- Journal of Oncology

- Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity

The potential impact of this decision could be significant for authors. When a journal is no longer included in Web of Science, Clarivate no longer indexes the papers published in the journal, no longer counts citations from papers published in the journal, and no longer calculates an impact factor for the journal (Kincaid, 2023). Authors who publish in these journals will be negatively impacted as many universities factor in these types of metrics into promotion and tenure decisions (Kincaid, 2023).

This is just one of the more recent examples of the struggles Hindawi and Wiley have grappled with since Wiley purchased Hindawi in 2021. Last year, Wiley announced the retraction of more than 500 Hindawi papers that had been linked to peer review rings . Hindawi has also been involved in paper mill activity, publishing articles coming out of paper mills in at least nine of the journals that were delisted. Paper mills are “unethical outsourcing agencies proficient in fabricating fraudulent manuscripts submitted to scholarly journals” (Pérez-Neri et al., 2022).

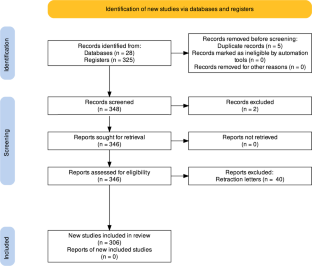

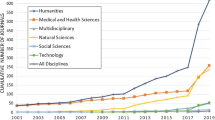

In the early days of paper mills, plagiarism was the biggest concern. However, paper mills have become more sophisticated and are now capable of fabricating data, and images, and producing fake study results (Pérez-Neri et al., 2022). Pérez-Neri et al. reviewed 325 retracted articles with suspected paper mill involvement from 31 journals and found that these retracted articles produced 3,708 citations (Pérez-Neri et al., 2022). The study also found a marked increase in retracted paper mill articles with the number of paper mill articles increasing from nine articles in 2016, to 44 articles in 2017, 88 articles in 2018, and 109 articles in 2019 (Pérez-Neri et al., 2022). Nearly half of the analyzed retracted papers (45%) were from the health sciences fields (Pérez-Neri et al., 2022). In a pre-print analysis of Hindawi’s paper mill activity , Dorothy Bishop found that paper mills target journals “precisely because they are included in WoS [Web of Science], which gives them kudos and means that any citations count towards indicators such as H-index, which is used by many institutions in hiring and promotion” (Bishop, 2023).

Another model that has become popular among questionable journals is the “guest editor” model, in which a journal invites a scholar or group of scholars to serve as guest editors for a specific issue of papers on the same topic or theme. MDPI is another publisher once identified by Jeffrey Beall as potentially predatory and has made efforts to turn around its reputation and become known as a reputable scholarly publisher. MDPI has used the guest editor model to help grow its business. In a recent post in The Scholarly Kitchen , Christos Petrou wrote that “the Guest Editor model fueled MDPI’s rise, yet it pushed Hindawi off a cliff” (Petrou, 2023). According to Petrou, the guest editor model accounts for at least 60% of MDPI’s papers. Hindawi has also embraced this model in recent years increasing the number of papers published under the guest editor model from 17% of papers in 2019 to 53% of papers published in 2022 (Petrou, 2023). Hindawi’s use of the guest editor model contributed to its exploitation by paper mills, which lead to more than 500 retractions between November 2022 and March 2023 (Petrou, 2023).

MDPI was not left unscathed by Clarivate’s decision to delist 50 journals from Web of Science. MDPI’s largest journal, the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health (IJERPH) , which had an Impact Factor above 4.0, was among the titles delisted in March. IJERPH was delisted for publishing content that was not relevant to the journal’s scope. Petrou argued that while this is likely a problem for hundreds of other journals, Web of Science “sent a message by going after the largest journal of MDPI” (Petrou, 2023).

The guest editor model is no longer used exclusively by questionable publishers and has slowly been embraced by traditional scholarly publishers. Petrou encourages publishers interested in the guest editor model to implement transparent safeguards into this model to uphold editorial integrity. While the scholarly publishing landscape continues to evolve and formerly questionable publishers attempt to gain legitimacy and stabilize their reputations, we must remain vigilant in evaluating the journals in which we choose to publish. Likewise, scholarly publishers must address the research integrity of the articles they publish by ensuring safeguards are in place to prevent the proliferation of paper mill-produced papers from making it through the peer review and screening process and ending up as published papers in trusted journals, only to be retracted once they have been exposed as fraudulent.

References:

Bishop, D. V. M. (2023, February 6). Red flags for paper mills need to go beyond the level of individual articles: a case study of Hindawi special issues. PsyArXiv Preprints . https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/6mbgv

Kincaid, E. (2023, March 21). Nearly 20 Hindawi journals delisted from leading index amid concerns of papermill activity. Retraction Watch . https://retractionwatch.com/2023/03/21/nearly-20-hindawi-journals-delisted-from-leading-index-amid-concerns-of-papermill-activity/#more-126734

Pérez-Neri, I., Pineda, C., & Sandoval, H. (2022). Threats to scholarly research integrity arising from paper mills: A rapid scoping review. Clinical Rheumatology, 41(7), 2241-2248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-022-06198-9

Petrou, C. (2023, March 30). Guest post: Of special issues and journal purges. The Scholarly Kitchen . https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2023/03/30/guest-post-of-special-issues-and-journal-purges/?informz=1&nbd=c6b4a896-51b7-4c2b-abe8-f0c60236adc9&nbd_source=informz

Share this post:

- Campus Advisories

- EO/Nondiscrimination Policy (PDF)

- Website Privacy Notice

- Accessibility

- Terms of Use

GW is committed to digital accessibility. If you experience a barrier that affects your ability to access content on this page, let us know via the Accessibility Feedback Form .

Subscribe By Email

Get every new post delivered right to your inbox.

Your Email Leave this field blank

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

This site uses cookies to offer you a better browsing experience. Visit GW’s Website Privacy Notice to learn more about how GW uses cookies.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 19 January 2024

Science’s fake-paper problem: high-profile effort will tackle paper mills

- Katharine Sanderson 0

Katharine Sanderson is a reporter for Nature in London.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

A high-profile group of funders, academic publishers and research organizations has launched an effort to tackle one of the thorniest problems in scientific integrity: paper mills , businesses that churn out fake or poor-quality journal papers and sell authorships. In a statement released on 19 January, the group outlines how it will address the problem through measures such as closely studying paper mills, including their regional and topic specialties, and improving author-verification methods.

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Nature 626 , 17-18 (2024)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-00159-9

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

Nature is committed to diversifying its journalistic sources

Editorial 27 MAR 24

Numbers highlight US dominance in clinical research

Nature Index 13 MAR 24

Peer-replication model aims to address science’s ‘reproducibility crisis’

The corpse of an exploded star and more — March’s best science images

News 28 MAR 24

How papers with doctored images can affect scientific reviews

Tenure-track Assistant Professor in Ecological and Evolutionary Modeling

Tenure-track Assistant Professor in Ecosystem Ecology linked to IceLab’s Center for modeling adaptive mechanisms in living systems under stress

Umeå, Sweden

Umeå University

Faculty Positions in Westlake University

Founded in 2018, Westlake University is a new type of non-profit research-oriented university in Hangzhou, China, supported by public a...

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Westlake University

Postdoctoral Fellowships-Metabolic control of cell growth and senescence

Postdoctoral positions in the team Cell growth control by nutrients at Inst. Necker, Université Paris Cité, Inserm, Paris, France.

Paris, Ile-de-France (FR)

Inserm DR IDF Paris Centre Nord

Zhejiang Provincial Hospital of Chinese Medicine on Open Recruitment of Medical Talents and Postdocs

Director of Clinical Department, Professor, Researcher, Post-doctor

The First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University

Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Warmly Welcomes Talents Abroad

“Qiushi” Distinguished Scholar, Zhejiang University, including Professor and Physician

No. 3, Qingchun East Road, Hangzhou, Zhejiang (CN)

Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital Affiliated with Zhejiang University School of Medicine

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Threats to scholarly research integrity arising from paper mills: a rapid scoping review

- Perspectives in Rheumatology

- Published: 06 May 2022

- Volume 41 , pages 2241–2248, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Iván Pérez-Neri ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0190-7272 1 na1 ,

- Carlos Pineda ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0544-7461 2 na1 &

- Hugo Sandoval ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9622-1558 2

1111 Accesses

12 Citations

15 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

“Paper mills” are unethical outsourcing agencies proficient in fabricating fraudulent manuscripts submitted to scholarly journals. In earlier years, the activity of such companies involved plagiarism, but their processes have gained complexity, involving the fabrication of images and fake results. The objective of this study is to examine the main features of retracted paper mills’ articles registered in the Retraction Watch database, from inception to the present, analyzing the number of articles per year, their number of citations, and their authorship network. Eligibility criteria for inclusion: retracted articles in any language due to paper mill activity. Retraction letters, notes, and notices, for exclusion. We collected the associated citations and the journals’ impact factors of the retracted papers from Web of Science (Clarivate) and performed a data network analysis using VOSviewer software. This scoping review complies with PRISMA 2020 statement and main extensions. After a thorough analysis of the data, we identified 325 retracted articles due to suspected operations published in 31 journals (with a mean impact factor of 3.1). These retractions have produced 3708 citations. Nearly all retracted papers have come from China. Journal’s impact factor lower than 7, life sciences journals, cancer, and molecular biology topics were common among retracted studies. The rapid increase of retractions is highly challenging. Paper mills damage scientific research integrity, exacerbating fraud, plagiarism, fake images, and simulated results. Rheumatologists should be fully aware of this growing phenomenon.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Perceptions of and attitudes toward plagiarism and factors contributing to plagiarism: a review of studies.

Fauzilah Md Husain, Ghayth Kamel Shaker Al-Shaibani & Omer Hassan Ali Mahfoodh

Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach

Zachary Munn, Micah D. J. Peters, … Edoardo Aromataris

Open peer review: promoting transparency in open science

Dietmar Wolfram, Peiling Wang, … Hyoungjoo Park

Data availability

Data and materials are available at:

https://osf.io/mnezt/?view_only=9dce5e2e2102451884f37782860defc5

https://osf.io/9wqfy/?view_only=e87dfe394ac34fa090115d2d394c9137

Code availability

Not applicable.

Campbell CR, Swift CO, Denton L (2000) Cheating goes hi-tech: online term paper mills. J Manag Educ 24(6):726–740

Article Google Scholar

Hersey C, Lancaster T (2015) The online industry of paper mills, contract cheating services, and auction sites. In: Clute Institute Education Conference, London

COPE Systematic manipulation of the publishing process via “paper mills”. Discussion documents. https://publicationethics.org/publishing-manipulation-paper-mills . Accessed Jan 12, 2021

Seifert R (2021) How Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology deals with fraudulent papers from paper mills. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 394(3):431–436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00210-021-02056-8

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hong ST (2017) Plagiarism continues to affect scholarly journals. J Korean Med Sci 32(2):183–185. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2017.32.2.183

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Forest C, Haiech J, Hervé C (2020) Les fabriques à articles : un moyen pour publier plus en expérimentant moins et être évalué positivement. Ethics, Medicine and Public Health 15:100592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemep.2020.100592

Byrne JA, Christopher J (2020) Digital magic, or the dark arts of the 21(st) century-how can journals and peer reviewers detect manuscripts and publications from paper mills? FEBS Lett 594(4):583–589. https://doi.org/10.1002/1873-3468.13747

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

COPE Potential “paper mills” and what to do about them – a publisher’s perspective. https://publicationethics.org/publishers-perspective-paper-mills . Accessed Jan 12, 2021

Leonid Schneider (2020) The full-service paper mill and its Chinese customers. https://forbetterscience.com/2020/01/24/the-full-service-paper-mill-and-its-chinese-customers/ . Accessed Jan 28, 2021

Christopher J (2021) The raw truth about paper mills. In. Wiley Online Library, pp 1751–1757

Calver M (2021) Combatting the rise of paper mills. Pac Conserv Biol 27(1):1–2. https://doi.org/10.1071/PCv27n1_ED

Hvistendahl M (2013) China’s publication bazaar. Science 342(6162):1035–1039. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.342.6162.1035

September 2020) Systematic manipulation of the publishing process via “paper mills”. https://publicationethics.org/publishing-manipulation-paper-mills . Accessed 21 Mar 2021

Moore A (2020) Predatory preprint servers join predatory journals in the paper mill industry...: plagiarism and malpractice breed rampantly in money-making incubators. Bioessays 42(11):e2000259. https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.202000259

Qi C, Zhang J, Luo P (2021) Emerging concern of scientific fraud: deep learning and image manipulation. bioRxiv:2020.2011.2024.395319. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.24.395319

Jennifer Byrne And Jana Christopher (2020) How can editors detect manuscripts and publications from paper mills? https://www.wiley.com/network/archive/how-can-editors-detect-manuscripts-and-publications-from-paper-mills . Accessed Mar 21, 2021

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Godfrey CM, Macdonald MT, Langlois EV, Soares-Weiser K, Moriarty J, Clifford T, Tuncalp O, Straus SE (2018) PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 169(7):467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Teixeira da Silva JA (2021) A reality check on publishing integrity tools in biomedical science. Clin Rheumatol 40(5):2113–2114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-021-05668-w

Booth A, Sutton A, Papaioannou D (2016) Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. SAGE Publications

Rethlefsen ML, Kirtley S, Waffenschmidt S, Ayala AP, Moher D, Page MJ, Koffel JB (2021) PRISMA-S: an extension to the PRISMA statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews(). J Med Libr Assoc 109(2):174–200. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2021.962

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C (2016) PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol 75:40–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021

Serghiou S, Marton RM, Ioannidis JPA (2021) Media and social media attention to retracted articles according to Altmetric. PLoS ONE 16(5):e0248625. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248625

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A (2016) Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 5(1):210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

McKeown S, Mir ZM (2021) Considerations for conducting systematic reviews: evaluating the performance of different methods for de-duplicating references. Syst Rev 10(1):38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01583-y

Polhemus AM, Bergquist R, Bosch de Basea M, Brittain G, Buttery SC, Chynkiamis N, Dalla Costa G, Delgado Ortiz L, Demeyer H, Emmert K, Garcia Aymerich J, Gassner H, Hansen C, Hopkinson N, Klucken J, Kluge F, Koch S, Leocani L, Maetzler W, Micó-Amigo ME, Mikolaizak AS, Piraino P, Salis F, Schlenstedt C, Schwickert L, Scott K, Sharrack B, Taraldsen K, Troosters T, Vereijken B, Vogiatzis I, Yarnall A, Mazza C, Becker C, Rochester L, Puhan MA, Frei A (2020) Walking-related digital mobility outcomes as clinical trial endpoint measures: protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open 10(7):e038704. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038704

Kumar MR, Veeraprasad M, Babu PR, Kumar SS, Subrahmanyam BV, Rammohan P, Srinivas M, Agrawal A (2014) A retrospective review of snake bite victims admitted in a tertiary level teaching institute. Ann Afr Med 13(2):76–80. https://doi.org/10.4103/1596-3519.129879

Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA (2015) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 350:g7647. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647

Garritty C, Gartlehner G, Nussbaumer-Streit B, King VJ, Hamel C, Kamel C, Affengruber L, Stevens A (2021) Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. J Clin Epidemiol 130:13–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.10.007

Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors (2020) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis.

van Eck NJ, Waltman L (2010) Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 84(2):523–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3

Gasparyan AY, Nurmashev B, Udovik EE, Koroleva AM, Kitas GD (2017) Predatory publishing is a threat to non-mainstream science. J Korean Med Sci 32(5):713–717. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2017.32.5.713

Das N, Das S (2014) Hiring a professional medical writer: is it equivalent to ghostwriting? Biochem Med (Zagreb) 24(1):19–24. https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2014.004

Jacobs A, Wager E (2005) European Medical Writers Association (EMWA) guidelines on the role of medical writers in developing peer-reviewed publications. Curr Med Res Opin 21(2):317–322. https://doi.org/10.1185/030079905X25578

Gasparyan AY (2013) Authorship and contributorship in scholarly journals. J Korean Med Sci 28(6):801–802. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2013.28.6.801

Misra DP, Ravindran V, Agarwal V (2018) Integrity of authorship and peer review practices: challenges and opportunities for improvement. J Korean Med Sci 33(46):e287. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2018.33.e287

Gasparyan AY (2017) Reflecting on the achievements and looking to the future of an established rheumatology journal. Rheumatol Int 37(11):1771–1772. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-017-3822-2

Battisti WP, Wager E, Baltzer L, Bridges D, Cairns A, Carswell CI, Citrome L, Gurr JA, Mooney LA, Moore BJ, Pena T, Sanes-Miller CH, Veitch K, Woolley KL, Yarker YE, International Society for Medical Publication P (2015) Good publication practice for communicating company-sponsored medical research: GPP3. Ann Intern Med 163(6):461-464. https://doi.org/10.7326/M15-0288

Download references

Author information

Iván Pérez-Neri and Carlos Pineda contributed equally.

Authors and Affiliations

Department of Neurochemistry, National Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery Manuel Velasco Suárez, Insurgentes Sur 3877, La Fama, Tlalpan, Ciudad de Mexico, 14269, México

Iván Pérez-Neri

General Directorate, National Institute of Rehabilitation Luis Guillermo Ibarra Ibarra, Calzada México-Xochimilco 289, Arenal de Guadalupe, Ciudad de México, 14389, México

Carlos Pineda & Hugo Sandoval

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

I. P. N. provided methodological expertise and contributed to designing review methodology (including the search strategy), data analysis, coordinating co-author’s participation and activities, correcting, and approving the final draft, documenting, and implementing protocol amendments. C. P. provided topic expertise and contributed to supervising the reviewer team, revising, and approving methodology and final draft. H. S. provided methodological expertise, contributed to the original idea, concept, and design of the study, drafted the manuscript, revised, corrected, and approved the review’s methodology and final draft, including peer-reviewing the search strategy, and is the guarantor of the review.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Hugo Sandoval .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval, consent to participate, consent for publication, disclosures, additional information, publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (PDF 82 KB)

Supplementary file2 (pdf 54 kb), supplementary file3 (pdf 63 kb), supplementary file4 (pdf 99 kb), rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Pérez-Neri, I., Pineda, C. & Sandoval, H. Threats to scholarly research integrity arising from paper mills: a rapid scoping review. Clin Rheumatol 41 , 2241–2248 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-022-06198-9

Download citation

Received : 08 February 2022

Revised : 30 April 2022

Accepted : 02 May 2022

Published : 06 May 2022

Issue Date : July 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-022-06198-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Ethics in publishing

- Paper mills

- Retraction of publication

- Scientific misconduct

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Forget plagiarism: there’s a new and bigger threat to academic integrity

Professor of Management, University of Johannesburg

Disclosure statement

Adele Thomas does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Johannesburg provides support as an endorsing partner of The Conversation AFRICA.

View all partners

Academic plagiarism is no longer just sloppy “cut and paste” jobs or students cribbing large chunks of an assignment from a friend’s earlier essay on the same topic. These days, students can simply visit any of a number of paper or essay mills that litter the internet and buy a completed assignment to present as their own.

These shadowy businesses are not going away anytime soon. Paper mills can’t be easily policed or shut down by legislation. And there’s a trickier issue at play here: they provide a service which an alarming number of students will happily use.

Managing this newest form of academic deceit will require hard work from established academia and a renewed commitment to integrity from university communities.

Unmasking the “shadow scholar”

In November 2010, the Chronicle of Higher Education published an article that rocked the academic world. Its anonymous author confessed to having written more than 5000 pages of scholarly work per year on behalf of university students. Ethics was among the many issues this author had tackled for clients.

The practice continues five years on. At a conference about plagiarism held in the Czech Republic in June 2015, one speaker revealed that up to 22% of students in some Australian undergraduate programmes had admitted to buying or intending to buy assignments on the Internet.

It also emerged that the paper mill business was booming . One site claims to receive two million hits each month for its 5000 free downloadable papers. Another allows cheats to electronically interview the people who will write their papers. Some even claim to employ university professors to guarantee the quality of work.

Policing and legislation becomes difficult because the company selling assignments may be domiciled in the US while its “suppliers”, the ghostwriters, are based elsewhere in the world. The client, a university student, could be anywhere in the world – New York City, Lagos, London, Nairobi or Johannesburg.

No quick fixes

If the companies and writers are all shadows, how can paper mills be stopped? The answers most likely lie with university students – and with the academics who teach them.

The anonymous writer whose paper mill tales shocked academia explained in the piece which kinds of students were using these services and just how much they were willing to pay. At the time of writing, he was making about US$66,000 annually. His three main client groups were students for whom English is a second language; students who are struggling academically and those who are lazy and rich.

His criticism is stinging:

I live well on the desperation, misery, and incompetence that your educational system has created.

Ideally, lecturers in the system of which he’s so dismissive should know their students and therefore be able to detect abnormal patterns of work. But with large undergraduate classes of 500 students or more, this level of engagement is impossible. The opportunity for greater direct engagement with students rises at postgraduate levels as class sizes drop.

Academics should also carefully design their methods of assessment because these could serve to deter students from buying assignments and dissertations. Again, this option is more feasible with smaller numbers of postgraduate students and live dissertation defences.

This isn’t foolproof. Students may still take the time to familiarise themselves with the contents of the documents they’ve bought so they can answer questions without exposing their dishonesty.

At the conference, some academics suggested that students should write assignments on templates supplied by their university which will track when work is undertaken and when it’s incorporated into the document. However, this sort of remedy is still being developed.

There is another problem with calling on academics alone to tackle plagiarism. Research suggests that many may themselves be guilty of the same offence or may ignore their students’ dishonesty because they feel investigating plagiarism takes too much time.

It has also been proved that cheating behaviour thrives in environments where there are few or no consequences. But perhaps herein lies a solution that could help in addressing the problem of plagiarism and paper mills.

The role of universities

Universities exist to advance thought leadership and moral development in society.

As such, their academics must be role models and must promote ethical behaviour within the academy. There should be a zero tolerance policy for academics who cheat. Extensive instruction should be provided to students about the pitfalls of cheating and they must be taught techniques to improve their academic writing skills .

Universities must develop a culture of integrity and maintain this through ongoing dialogue about the values on which academia is based. They also need to develop institutional moral responsibility by really examining how student cheating is dealt with, confronting academics’ resistance to reporting and dealing with such cheating, and taking a tough stand on student teaching.

If this is done well then institutional values will become internalised and practised as the norm. Developing such cultures requires determined leadership at senior university levels.

- Higher education

- Essay mills

- Academic cheating

- Academic integrity

Biocloud Project Manager - Australian Biocommons

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

Deputy Editor - Technology

Paper Mills- A Rising Concern in the Academic Community

This article is also available in Japanese

A good publishing record is one of the essential criteria for promotion, tenure, and grant acquisition for future projects. The pressure to publish more papers drives researchers towards unethical practices such as purchasing fictitious research papers. Academic frauds including data falsification, image manipulation, fabricated peer review have plagued the research publishing landscape for years together! The research community is working hard to maintain research integrity. Despite strict measures and vigilance, research misconduct and academic foul play has been discovered in manuscripts accepted by publishing powerhouses such as the Nature Publishing Group, Wiley, Taylor & Francis, etc. In addition to concerns related to plagiarism, ethical issues, and authorship disputes, the scientific community is now bracing to fight against the act of systematic manipulation of manuscripts by “paper mills”.

What is a Paper Mill?

Paper Mill is a potentially illegal organization that produces and sells fraudulent scientific manuscripts written by ghostwriters on demand! Researchers who require publications for furthering their career or meeting institutional criteria for promotion buy publication ready manuscripts. The service is purely profit-oriented. Researchers pay hefty amounts for authorships on ready-to-submit manuscripts. Their potential clients include researchers who wish an easy way out to publish in international journals without actually engaging in research. Some of the paper mills might have actual laboratories that perform experiments and produce actual data and images. Further, several authors buy these data to use in different experiments.

Hallmarks of Paper Mill Generated Manuscripts

Peculiar characteristics of manuscripts produced by paper mills include a generic hypothesis and experimental strategies, textual and organizational resemblances, and images that reflect duplication or manipulation. Let us go through them one-by-one.

- Manuscripts produced using paper mills have a set template having unusual similarity of text. They may also contain phrases that are almost identical or have been phrased in an awkward manner. Consider the following sentences: This study allowed us to have a better and in-depth understanding of the association between mutations in gene X and colon cancer risk. B. This study assisted in having an in-depth and better understanding of the association between gene Y and cervical cancer risk.

Both these statements have minor variations in wording. Authors simply plug in names of different genes and diseases into appropriate positions.

- Although the images can be real photos of cells/tissues, gels, flow cytometry profiles, they are fabricated to suit the experimental requirements.

For examples, western blot images presented in paper mill-generated manuscripts inexplicably contain similar background patterns and peculiarly shaped bands. A similar background across images published in manifold manuscript suggests either computer generated or copy-pasted images from other sources. The gel images also lack stains, dots, or fine smears that are normally present in such images.

Guillaume Filion, a biologist at the Center for Genomic Regulation in Barcelona has claimed that several manuscripts report the use of ‘Beggers funnel plot’ . It is a statistical test that does not exist. Furthermore, it is highly unlikely that multiple scientists working in different research labs independently invent the same name.

- They often have authors with non-institutional or personal email addresses.

- Manuscripts produced by paper mills provide very superficial explanations for methods or analyses used.

Concerns Associated with Identifying Manuscripts Produced by Paper Mills

- Spotting dubious manuscripts is not an easy task! Although several advanced tools such as iThenticate and PlagScan , that detect plagiarized text are available these days, tools that can detect plagiarized or fake data are not very common. On their own, these manuscripts appear legitimate, common patterns and shared features come to light only when editors compare multiple papers authored by different researchers with nothing in common.

- Journals’ editors may request for raw data if they are suspicious about a manuscript. However, checking data credibility is not straightforward, especially if analysis of data files requires specialist software. This process can be time consuming and expensive. In addition, it may be difficult to find out if the data is manipulated until you are an expert in that field. For instance, to judge whether a flow cytometry file has been made-up, you have to be a flow cytometry expert.

- Tracking correspondence can be problematic because it is uncertain whether the editors are approaching original authors or paper mill representatives.

Approaches to Detect Manuscripts Generated by Paper Mills

Editors and reviewers have become highly vigilant about submissions that are churned out of paper mills. An extensive investigation by RSC Advances led to retraction of about 68 articles on the grounds of falsified research. Following are the various means used to ensure no foul play is involved.

- Editors may request the authors to submit raw data associated with manuscript results and images.

- Reviewers may verify the identities of chemicals and reagents. They may also check for fully disclosed identities.

- Reviewers would check for valid study hypothesis and experiments drafted in accordance with study hypothesis.

What Should Researchers Do to Boost Journals’ Confidence in Their Manuscripts?

- Researchers must fully declare all the externally provided research results, if the experiments have been outsourced.

- Completely disclose the identities of all the raw materials, chemicals and reagents used in the study.

- Provide supplemental original source files (raw data/ individual data points) in a readable format.

- Authors may declare in the “Author’s Contributions” section that all the data were generated in their own laboratories using fair means and no paper mill was used.

As researchers would you only be concerned about increasing your publication count even at the cost of losing authenticity of papers? Wouldn’t citing of such papers mislead other researchers to falsified results and eventually hamper the growth of scholastic reasoning in science? Please let us know your thoughts on this in the comments section below. You can also visit our Q&A forum for frequently asked questions related to other unethical practices and how to avoid them to enhance your publishing record answered by our team that comprises subject-matter experts, eminent researchers, and publication experts.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- AI in Academia

- Industry News

Controversy Erupts Over AI-Generated Visuals in Scientific Publications

In recent months, the scientific community has been grappling with a growing trend: the integration…

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Trending Now

The Silent Struggle: Confronting gender bias in science funding

In the 1990s, Dr. Katalin Kariko’s pioneering mRNA research seemed destined for obscurity, doomed by…

ICMJE Updates Guidelines for Medical Journal Publication, Emphasizes on Inclusivity and AI Transparency

The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) recently updated its recommendations for best practices…

Addressing Barriers in Academia: Navigating unconscious biases in the Ph.D. journey

In the journey of academia, a Ph.D. marks a transitional phase, like that of a…

China’s Ministry of Education Spearheads Efforts to Uphold Academic Integrity

In response to the increase in retractions of research papers submitted by Chinese scholars to…

Understanding the Difference Between Research Ethics and Compliance

Understanding Researcher Awareness and Compliance With Ethical Standards – A global…

Increasing Threat of Scientific Misconduct and Data Manipulation With AI

Mitigating Survivorship Bias in Scholarly Research: 10 tips to enhance data integrity

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

Industrialized Cheating in Academic Publishing: How to Fight “Paper Mills”

A growing problem in research and publishing involves “paper mills”: organizations that produce and sell fraudulent manuscripts that resemble legitimate research articles. This form of fraud affects the integrity of academic publishing, with repercussions for science as well as the general public. How can fake articles be detected? And how can paper mills be counteracted?

In this episode of Under the Cortex , Dorothy Bishop talks with APS’s Ludmila Nunes about the metascience of fraud detection, industrial-scale fraud and why it is urgent to tackle the fake-article factories known as “paper mills.” Bishop, a professor of neurodevelopmental psychology at Oxford University, is also known for her breakthrough research on developmental disorders affecting language and communication.

Unedited transcript:

[00:00:12.930] – Ludmila Nunes

In research and publishing, “paper mills” are organizations that produce and sell fraudulent manuscripts that resemble legitimate research articles. This form of fraud affects the integrity of academic publishing with repercussions for the science itself, but also for the general public. How can these fake articles be detected? And how can paper mills be counteracted? Today’s episode will explore these questions. This is under the cortex. I am Ludmila Nunes with the association for Psychological Science. Today I have with me Dorothy Bishop, professor of Neurodevelopmental Psychology at Oxford University. Dr. Bishop is known for her breakthrough research on developmental disorders affecting language and communication, which has helped to build and advance the developmental language impairment field. But Dr. Bishop’s interests go well beyond neurodevelopmental psychology, as her blog, Bishop Blog, illustrates. At the APS International Convention of Psychological Science, held last March in Brussels, dr. Bishop presented her work on the meta science of fraud detection, discussing industrial scale fraud and why it is urgent to tackle the so called paper mills, or fake articles factories. I invited Dr. Bishop to join us today and tell us more about the battle against industrialized cheating in academic publications. Dorothy, thank you for joining me today.

[00:01:50.400] – Ludmila Nunes

Welcome to Under the Cortex.

[00:01:52.360] – Dorothy Bishop

Thank you very much for inviting me, Ludmila, it’s lovely to be here.

[00:01:56.870] – Ludmila Nunes

So I was lucky enough to see your presentation at ICPS, and I thought this topic was fascinating because it’s a different type of fraud than what we usually talk about in psychology. We talked a lot about replication crisis. Some researchers faking their data, but this is different. Do you want to explain us what paper mills are?

[00:02:23.950] – Dorothy Bishop

Yes. As you said before, they’re this sort of industrial scale fraud. I think perhaps initially started out as helping people write papers for language reasons, but then sort of veered into actually creating fake papers that they would then sell to people that needed publications and then place them in journals. So you have these strange papers that really you can divide into two types. The first type is like the plausible paper mill paper, which is often made from a template of a genuine paper. So they’ve taken a genuine paper and then just tweaked it a bit so that it looks like a perfectly decent piece of work, but has had some changes. And then there’s another kind which seems to be very weird papers that anybody who reads them will think they’re extremely strange, and they possibly are computer generated, or in some cases, they seem to be plagiarized or possibly just based on very basic things like undergraduate essays. So they’re a bit of a mishmash, but they are things that would not normally pass peer review. And so the question that really started to interest me is, how did these things even get into the literature?

[00:03:39.910] – Dorothy Bishop

The first kind of paper mill paper, which looks plausible, you can imagine, would have just have fooled a regular editor. But this second kind that look very weird and don’t often make much sense and may have all sorts of bizarre features, suggests that we’ve got a situation in some journals where the editorial process has been compromised and where editors may even be complicit with the paper mill.

[00:04:07.150] – Ludmila Nunes

And to make it clear, we are talking about articles that can make their way into more prestigious peer reviewed journals.

[00:04:14.840] – Dorothy Bishop

Yes, I mean, again, there’s a very wide range and it’s an evolving scenario. I sometimes draw parallels with things like COVID because it’s a bit like being suddenly attacked by some virus that mutates. But what people have discovered is that there’s a lot of money in this. And of course, if you can place a paper in a prestigious journal, that’s more valuable. And indeed, if you go online, these tend to not be in English, but there are some of these adverts in English, but mostly in other languages where the papers are actively advertised. So they’ll say authorship for sale and the amount you pay will depend on the caliber of the journal and on your authorship position. So there’s always a pressure from the paper mills. They regard it as a great success if they can get a paper into a prestigious journal, or at least into a journal that’s featured in, say, Web of Science at Clarivate, which means it gets indexed so that your citations would count in an H index. And I should say that you might say, well, who would cite these if they’re really rubbish? But they also do look after the citations.

[00:05:22.990] – Dorothy Bishop

So what will happen if you get a paper mill paper in one of these journals? A whole load of citations will be added, often of very little relevance to the content of the paper, but it’s clearly to boost citations of other paper mill papers. So there’s this entire industry which is rather like a sort of parallel universe where they’re playing at doing science and the outputs have all the hallmarks of regular science, but the content is just rubbish.

[00:05:51.810] – Ludmila Nunes

And so what made you aware and interest in this topic? Was it a specific event or you just started seeing these articles and thinking this seems weird that these even got published?

[00:06:05.970] – Dorothy Bishop

Yes, I’m trying to think back actually to exactly how it happened. But I think I was already interested after I retired. I retired last year, this time last year, and I decided I wanted to look a bit more at fraud because I’d been focusing on the reproducibility crisis that you’d mentioned and on questionable research practices and how to improve science more generally. But like most people, I think I regarded fraud as relatively rare and much more difficult to prove and so on. And I think it was probably the person that a Russian woman who co authored a paper on this with me, Anna Abalkina, who I knew from a Slack channel where we exchanged information, and she mentioned that she was aware of a paper mill and that some of the papers in it were psychology papers. But she is an economist, and she didn’t really feel she could evaluate these. So I offered to look at them. And then we found a little nest of six of these papers in a perfectly reputable psychology journal, which really surprised me that they really raised questions about how did they get in there, because these were of the kind that they were probably based on original projects or something, but they were no way of a caliber that would get into a journal.

[00:07:22.040] – Dorothy Bishop

It was often quite hard to work out what they were actually about. They sort of meandered around and talked in great generalities, and you might say, well, how do you know it was not just the editor having an off day? Well, Anna’s strategy for identifying these paper mill papers and these six came from a much bigger paper mill, but it was that you could find papers where the email address of the authors was a fake email address. So the domain looked like an academic domain, but you can track it back, and it’s a domain that is available for purchase on the web. So you can buy these email domains, and then you can make loads and loads of email addresses. And typically, they were email domain addresses that didn’t match the country of the author. So you’d have somebody with a UK or Irish looking email address, but from Kazakhstan, for example. That can happen if somebody’s moved jobs. But it kept happening in all these papers, and then I looked at them, and they clearly didn’t look as if they should be published anywhere. But you could say, well, I’m just being difficult there.

[00:08:31.910] – Dorothy Bishop

But the real interesting point with these was that in most cases, they had open peer review. And so you could look at the peer review, and the peer review did not look like normal peer review. It was incredibly superficial. So it would say things like, the paragraphs are too long, break them up. Or it would say, the reference list needs refreshing. And the same terminology used across these six papers, very short referee reports asking for very superficial changes, not engaging at all with the content. And the peer reviewers who are in some cases listed were people if you tried to find them online, they didn’t seem to exist, or they had very shady presences. You couldn’t find that they’d ever published anything. So it looked as if the whole business of peer review had been compromised by using fake peer reviewers with fake email addresses and fake authors with these fake email addresses to get these publications accepted in the journal.

[00:09:31.750] – Ludmila Nunes

So you started by looking at this set of six articles, and then you went beyond that.

[00:09:37.910] – Dorothy Bishop

Well, Anna had already gone well beyond that, I have to say. She’s got a spreadsheet with I think now it’s gone to a couple of thousand papers, all with these same sorts of characteristics. And of course the difficulty is you do tend to have to go through carefully. You don’t want to accuse somebody who’s written a perfectly legitimate paper. So it’s quite painstaking work. She’s found, more recently another journal. This one was the Journal of Community Psychology. It’s a Wiley journal. There was another journal, I can’t remember the publisher, but another psychology journal that looked thoroughly reputable where another little cluster occurred. And of course, one of the things we wanted to do was to say, how did this happen? Because it does suggest that the editor was either asleep at the job or was involved in the paper mill. And it was hard to believe this because it looked again like a perfectly reputable editor. So the way we tried to test that was by actually submitting a paper to the Journal in which we described the paper mill to sort of like act as a sort of sting operation, in the sense that we thought if he was really just not reading the papers and delegating to somebody to just sort of go through the motions, it maybe he wouldn’t notice that our paper was highly critical of his journal.

[00:10:49.460] – Dorothy Bishop

In fact, he did notice and he just desk rejected our paper and said it was a very superficial paper, which is hilarious given what he did. So that to us did seem evidence that something was seriously wrong with the way he was treating papers. And we did complain and write to the integrity person in Wiley and eventually those papers were all retracted, I’m pleased to say. But yes, I also then around the same time did start looking at other journals. I mean, there are a number of people doing this and it’s painstaking work. You sort of could trawl through some of these journals. But there’s another way in which things are getting into less reputable journals, perhaps, although still journals that were listed in Clarabay and that’s via special issues. So some journals have realized that a good way to get a lot of submissions and if you’re charging people for submissions, this makes a lot of money, is to have a special issue. And so they advertised in the journal saying, would you like to edit a special issue? In fact, some of your listeners may have had emails from such journals saying, would you like to edit a special issue?

[00:12:00.010] – Dorothy Bishop

We’re very keen on this. And then it seems that they didn’t do sufficient quality control on the people who replied. And there were people in paper mills who clearly realized this was an amazing opportunity to get somebody in as an editor and then they can just accept whatever they like. And this was on a different scale to that previous case I mentioned. So there are a number of hindawi journals in particular, which is again a subgroup of Wiley, unfortunately, but they were really expanding the number of special issues massively. And they had articles in there that were even worse than the ones in the Journal of Community Psychology in the sense that they really made no sense. So I invented a term for some of them which was AI Gobbledygoop, because you would have a few paragraphs that made sort of sense but were just bit boring and not very you didn’t really know where it was going, but they were about something. In some cases, they were about something that had nothing to do with the journal, like Marxism in a Journal of Environmental Health. So you’d have your bit about Marxism, then you’d suddenly get in the middle a whole load of very, very technical artificial intelligence stuff, full of formulae and technical terms which didn’t relate to anything else very much as far as you could see, and then it would revert at the end to the more standard stuff.

[00:13:22.910] – Dorothy Bishop

And it was like a sandwich with this strange stuff in the middle that was you couldn’t necessarily with competence, say it was rubbish. But what you can often do is then track it to Wikipedia. It was often just lifted from Wikipedia. And these things were at scale. I mean, we’re talking about literally sometimes more than 100 such papers in a special issue with a particular editor. And so I started doing big analyses of those by really just combing the website of certain journals to see how many had these special issues with numerous papers who were the editors. And then looking at actually the response times between the submission to the journal.

[00:14:05.810] – Ludmila Nunes

I bet they were much faster than.

[00:14:08.340] – Dorothy Bishop

Usual, they tended to be very fast. And then I could tie that in with whether these papers had had comments on the website pub peer. Now, Pubier is a very useful post publication peer review website where anybody can put in a statement or comment on a paper. And of course there’s not huge quality control, although they do weed out completely crazy things or stuff that’s libel us. But basically a lot of people had started picking up on paper mills and making comments about things like the references bear no relationship to the paper, or the paper doesn’t bear any relationship to the topic of the journal, or picking up on duplication or plagiarized material and things like this. And so I could show that there were massive amounts of these Pub peer comments, particularly for the special issues, which had things accepted very, very fast. And it identified about 30 journals that were, I think, pretty problematic on the there’s no one indicator that something’s a paper mill, but when you get enough of these different indicators, you can start to be and particularly when it’s across a number of papers in the journal, you realize it’s a problem.

[00:15:22.420] – Dorothy Bishop

So rather to my surprise, I mean, I just had no idea how much of this stuff there was out there. But you could have a full time job investigating this because it’s getting worse, I think, and it’s going to get worse as artificial intelligence gets worse. And it’s easier to generate papers that are fake but that don’t look as crazy as some of the ones that I’ve been looking at.

[00:15:43.940] – Ludmila Nunes

That’s exactly what I was going to ask you, if you think that the amount of these fake papers is increasing and what role artificial intelligence might play in masking them better and making them harder to detect.

[00:16:01.000] – Dorothy Bishop

Yeah, I think it’s very frightening because we’ve just recently, I mean, there’s been such a lot of excitement just in the past couple of months about the new AI systems that are coming out that can generate people are worried about student essays and things. Anybody can cheat, and it’s very hard to pick it up. That’s going to apply as well to academic articles. And previously, some of the attempts to use AI have led to very unintentionally hilarious consequences because what they were trying to do, they were plagiarizing stuff and then running it through some AI that put it through a sort of thesaurus to change some of the words because they were trying to avoid plagiarism detectors. And that sometimes led to very strange turns of phrase, particularly in statistical things. So that instead of the sort of standard error of the mean, it would be the standard blunder of the mean. If you know of statistics, this is bad, it’s not what is called. And then breast cancer becomes bosom peril. And there’s a guy and team, in fact a guy running a little team of people in France who have been gathering examples of these and then doing the opposite.

[00:17:06.830] – Dorothy Bishop

They’re actually running articles, picking up these, what they call tortured phrases to identify paper mill products. And that’s a very good way at the moment of identifying them. But of course, I doubt it will have much longevity because the odds are that as soon as the paper mill people realize that you can do that, they’ll move it to something else and they’ll stop using and indeed, that they’ll probably no longer find it necessary to use that system. But I have to say it causes a lot of merriment in looking at some of the things that people put into papers when they don’t know what the words actually mean.

[00:17:41.410] – Ludmila Nunes

Okay, so we’ve been talking about this way of cheating and getting articles published, articles that aren’t real. But who is benefiting from these?

[00:17:52.550] – Dorothy Bishop

Very good question. Lots of people are benefiting, unfortunately. The sad reality is that there are a number of countries where you are required to have publications to progress in your career. And the earlier paper mills were from China, where in the medical profession, if you wanted to be a hospital doctor and you weren’t interested in doing research, you nevertheless had to have a publication to, I think, advance to be the next level consultant or whatever. And so, of course, the motivation for people to buy such a publication was really high and in fact, I think in some cultures people don’t regard it as doing anything wrong to do this. So there’s a sort of whole cultural thing that well, of course you do this because this is something you’re required to do and there’s no way you’re really going to generate a publication. The Chinese academic system, I think, is beginning to realize that they have a massive problem and they’re trying now to take measures to prevent this. But it’s been going on and a lot of these ones in the Hindawi journals that I mentioned do come from China and there are other countries too where there is this sort of system.

[00:19:02.940] – Dorothy Bishop

So unfortunately, Kazakhstan, Ukraine also to some extent, Iran. So they tend to be countries where the pressures on people who want to advance are extreme and the resources are perhaps not so good. And sometimes you can trace the paper mills, unfortunately, to people in senior positions who’ve found this is a good money making enterprise. So once you get corruption in the system, unfortunately it really can encourage this. Now, of course, the people that make huge sums of money are the people who are selling the papers and they are just straightforward crooks, but they are making huge amounts of money. If you’re producing these things and you’re charging people $1,000 per paper published in just one journal you’ve got perhaps 100 special issues each with 50 odd papers in. You can do the sums and start to realize that the income is huge. And then the publishers you see that there’s been a lot of criticism of the idea that the publishers may have been complicit because they’re making so much money from the article processing charges. But for them, the chickens have now come home to roost just recently in a very big way because Clarivate has delisted a whole load of Hindawi journals for exactly this.

[00:20:24.090] – Dorothy Bishop

So I think what they say is they’ve been using their own again, everybody’s using AI, but they’ve been using their own developed AI systems to try and spot paper mill products and have identified patterns that are clearly abnormal in some of these journals and realized that it’s doing a lot of harm to have them in the main scientific literature. And that’s very damaging to the publisher whose profits, in fact, visibly have sunk. People have been documenting how much they’ve lost. So ultimately, I think people say, oh, well, the publishers went into it for the money but I think they must know that it’s not in their interest to get a very bad reputation for publishing rubbish. I think the problem has been not so much that they’ve been doing it on purpose, but that they’ve taken their eye off the ball and they have really not paid sufficient attention to the importance of vetting editors. The editor has a role as a gatekeeper, which is very important. And I think editors have just been assumed that anybody can do it and you don’t really need much in the way of qualifications or background. And in fact you obviously do need people not only with some publications but with integrity and some sort of track record and you know, who are doing it for the right reasons.

[00:21:40.850] – Dorothy Bishop

And I’m afraid that you’ve got the impression that almost anybody would be accepted as an editor for a period during sort of 2021, 2022.

[00:21:51.570] – Ludmila Nunes

So this is a problem, of course, because it’s an ethical problem, but it’s also a scientific problem because having these articles around can impair the development of science.

[00:22:05.040] – Dorothy Bishop

Absolutely.

[00:22:06.330] – Ludmila Nunes

And I’m thinking, for example, undergrad students or very young students who are not so used to read scientific articles and are not used to scrutinize the articles can get the wrong idea and think that this research is actually good research.

[00:22:26.590] – Dorothy Bishop

Another thing to bear in mind is that we’re now in the world of big data and there’s an awful lot of research is now involving metaanalyses or in the biological sphere, massive sort of big data things where they are pulling in from the internet lots. I mean, it feels like cancer biology, which are plagued by paper mills. A lot of people’s research involves automating processes for trawling the literature to find studies that work on a particular gene or a particular compound of some sort and then just sort of putting them all in a big database of associations between genes and phenotypes. Now, if this stuff gets in there, you can imagine it plays havoc with the people who then want to use those databases for, say, drug development. So I don’t think there’s probably quite a parallel for that in psychology. But that’s the kind of worry that one has and even the really rubbishy ones. I mean, if you’re trying to do a metaanalysis and it throws up loads and loads of papers, you have to check each of those papers, you’re just wasting your time. Even if you come to the conclusion that it’s a rubbish paper, you can’t include it’s clogging up people’s attention span and clogging up the literature.

[00:23:36.300] – Dorothy Bishop

And as you say, some people may also not have the ability to tell that it’s rubbish. But even those of us that do, you still have to read it long enough to tell that it’s rubbish.

[00:23:46.010] – Ludmila Nunes

It’s still a waste of our time. And as you mentioned in many cases now if we are doing a meta analysis, we can just scrub the data and pull that from the articles. And if we are trusting that the sources are good sources, normal journals, these articles just make their way into a meta analysis.

[00:24:04.270] – Dorothy Bishop

For example, I mean, the other victims of this I would say, which is rather indirect, but you could argue that the victims are the honest people in the science. And I have had emails from clearly honest people from Iran, from China who are trying to report to me because I’ve somehow now identified as somebody who picks up on this stuff, colleagues who are doing this. And quite often, as I said before, these are quite senior people that might be doing this. And they’re desperate for it to be stopped because from their perspective, it’s awful because A, they can’t get on if they’ve got a boss who’s doing this and B, their entire country and all the research coming out of that country then gets denigrated as being flawed in this way. And it must be awful to be somebody who’s an honest scientist working in an environment where this stuff is happening at scale.

[00:24:57.790] – Ludmila Nunes

Exactly. We mentioned paper mills in China and of course we might start paying more attention to an article that comes from Chinese authors and trying to scrutinize, is this a real paper? Is this a fake paper? And that’s very unfair for the serious researchers, for people who are actually doing their job. But this issue also has repercussions for the general public and can contribute to the mistrust in science, which is already a problem.

[00:25:30.650] – Dorothy Bishop

Yeah. And I mean, some people then say, well, we shouldn’t talk about it because it will impair public trust in science. But I have the opposite view, which is that we should talk about it and show that we’re tackling it because we can’t expect people to trust us. If this sort of stuff is going on. We have to show that we can deal with it and that we take it seriously because unless we show that it really matters to us and we’re going to take it on, we don’t really deserve the trust of the public.

[00:26:00.710] – Ludmila Nunes

Exactly. I completely agree with you. I think hiding the problem is not going to help science and it’s not going to help the public to trust scientists at all.

[00:26:11.350] – Dorothy Bishop

But it’s a real problem that when the trust is eroded, because we’ve seen that very much with COVID that people do reach the point where they don’t know what to believe and they know there’s some misinformation out there and they know there’s some good information out there. If peer review is not, or supposed peer review is not a reliable signal anymore as to what is more trustworthy, then it’s very, very difficult because none of us can be experts in all these areas that are involved in judging whether things like a vaccine is effective or whether a disease is associated with symptoms. And we have to have some mechanism whereby we know that certain types of work are trustworthy. So it’s very, very important to keep this from polluting the journals and the sources that should be trustworthy.

[00:26:57.830] – Ludmila Nunes

So just to summarize to our listeners, are there any and I know you’ve already mentioned some, but which strategies can we use to evaluate an article? And I’m thinking mostly of the general public, if they find this random article online? Can they identify if this is a real article or if it might come from a paper mill?

[00:27:23.870] – Dorothy Bishop

Well, I think it’s very difficult. There are a few things that are obvious, like the tortured phrases. I mean, if you have a paper on Parkinson’s disease and instead of talking about Parkinson’s disease, it talks about Parkinson’s ailment or Parkinson’s malady, there’s quite a lot of literature that does that. It’s important to be aware that’s very unlikely to be just because somebody’s not got English as their first language. Because even if you don’t have that, you’ll be reading the literature. It’s all about Parkinson’s disease. So that sort of substitution suggests that something fishy has gone on and somebody’s deliberately trying to obscure the fact that work is plagiarized. So torture phrases is one good clue. A very rapid turnaround time, which isn’t always reported in a journal, but is sometimes reported in a journal, I regard as suspicious. I mean, you could just get lucky. This is probably it’s not 100% watertime. You could submit your paper and it’s immediately sent out for review and people immediately agree to review it. But anybody who has published papers knows that the usual thing is that it hangs around a bit before they can find reviewers and then the reviewers sit on it for a bit.

[00:28:32.680] – Dorothy Bishop