- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

A War to End All Innocence

By A.O. Scott

- June 20, 2014

“I feel like a soldier on the morning after the Somme.” This line of dialogue, from an episode in the second season of the BBC series “ Call the Midwife ,” caught my ear recently as an especially piquant morsel of period detail. It is uttered by a doctor to a nurse after they have just assisted in a grueling home birth, an experience that is compared to the four-month battle in a muddy stretch of Picardy beginning on July 1, 1916, that was, at the time, the bloodiest episode of combat in human history, generating 60,000 casualties in a single day of fighting on the British side alone. The doctor’s comparison is surely metaphorical overkill, but it also represents a familiar style of wit, a habit of linking the challenges we regularly endure with calamities we can scarcely imagine.

But why choose that particular calamity? “Call the Midwife,” based on a popular series of memoirs by Jennifer Worth, takes place in the late 1950s, not long after a war that, in terms of the sheer scale and extent of global slaughter, far eclipsed its predecessor. It is interesting that for this youngish doctor and nurse, the earlier conflict comes more readily to mind. The Somme is more accessible, and perhaps more immediate, than Dunkirk or D-Day.

The allusion may require a footnote now, but its occurrence in a television program that is acutely sensitive to historical accuracy is a sign of just how deeply, if in some ways obscurely, World War I remains embedded in the popular consciousness. Publicized in its day as “the war to end all wars,” it has instead become the war to which all subsequent wars, and much else in modern life, seem to refer. Words and phrases once specifically associated with the experience of combat on the Western Front are still part of the common language. We barely recognize “in the trenches,” “no man’s land” or “ over the top “ as figures of speech, much less as images that evoke what was once a novel form of organized mass death. And we seldom notice that our collective understanding of what has happened in foxholes, jungles, mountains and deserts far removed in space and time from the sandbags and barbed wire of France and Belgium is filtered through the blood, smoke and misery of those earlier engagements.

One person who did notice the lasting and decisive cultural influence of World War I was Paul Fussell, a literary scholar and World War II infantry veteran whose 1975 book, “ The Great War and Modern Memory ,” remains a tour de force of passionate, learned criticism. Fussell, who died in 2012, combed through novels, memoirs and poems written in the wake of the war and found that they established a pattern that would continue to hold, consciously and not, for much of the 20th century.

Many British soldiers and officers arrived at the front steeped in a literary tradition that colored their perception — a tradition that included not only martial epics and popular adventure novels but also religious and romantic allegories like John Bunyan’s “The Pilgrim’s Progress.” The central character in that 17th-century tale of desperate hardship and ultimate redemption is first seen as “a man clothed in rags” with “a great burden upon his back,” a description that seemed uncannily to prefigure the trench-weary conscript with his tattered uniform and heavy pack.

That soldier, in turn, with some adjustments of outfit and equipment, would march through the subsequent decades, leaving behind a corpus of remarkably consistent firsthand testimony. Whether presented as memoir or fiction, post-1918 war writing returns again and again to the same themes and attitudes. Among them are an emphasis on the tedium and terror of ground combat; the privileging of the ordinary soldier’s perspective over that of officers or strategists; a suspicion of authority and a tendency to mock those who wield it; a strong sense of the unbridgeable existential division between those who fight and the people back home; a taste for absurdity, sarcasm and black humor; and the conclusion that, whatever the outcome or justice of the war as a whole, its legacy for the individual veteran will be cynicism and disillusionment.

Fussell found these traits in the literature of his own war — in “The Naked and the Dead,” “Catch-22” and “Gravity’s Rainbow” — and they saturate the Vietnam narratives that followed the publication of his book. The title of “The Things They Carried,” Tim O’Brien’s cycle of autobiographical stories about life before, during and after combat in Vietnam, carries an echo of “The Pilgrim’s Progress,” and its blend of economical prose, blunt naturalism and surreal terror makes it both a definitive account of its own war and a recapitulation of the Great One.

Like nearly every other male writer in English to have tackled the subject of war, Mr. O’Brien owes a clear debt to Hemingway, who came as close to anyone to striking a template for how it should be dealt with in a famous passage from “A Farewell to Arms”:

“There were many words that you could not stand to hear and finally only the names of places had dignity. Certain numbers were the same way and certain dates and these with the names of the places were all you could say and have them mean anything. Abstract words such as glory, honor, courage, or hallow were obscene beside the concrete names of villages, the numbers of roads, the names of rivers, the numbers of regiments and the dates.”

This tough wisdom — itself curiously abstract, in spite of its insistence on specificity — has remained in effect even as the geography has changed. The imperative to tell what really happened, even to a public or a posterity incapable of fully understanding, has produced a literature full of names and dates. Verdun, Passchendaele, Gallipoli, Guadalcanal, Monte Cassino, Stalingrad, Inchon, Khe Sanh, Kandahar, Fallujah. Nov. 11; June 6; Tet; Sept. 11.

In 1964, 50 years after the war began, Philip Larkin, born in 1922, published a memorial poem called “ MCMXIV .” Larkin’s subject is less the war as such than a faded England of “archaic faces” and bygone habits, an England that ceased to exist sometime between the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on June 28 and the commencement of full, continent-engulfing hostilities at the beginning of August. The poem tries to freeze the moment when the older world — a world his parents knew intimately but one that lay just beyond the horizon of his own memory — “changed itself to past without a word.”

“Never such innocence again,” Larkin concludes, summarizing what was, then and now, a crucial tenet of the conventional wisdom about the Great War, a notion that informed Hemingway’s rejection of the old, elevated language of honor and glory. Even as he acknowledges the seductive power of the idea of lost innocence, Larkin also suggests that it is complicated, even deceptive. Individuals like the anonymous children and husbands who populate his lines can easily be imagined as innocent. Imperial nation-states that have spent the last few centuries conquering most of the rest of the globe are another story.

This was clear enough to Larkin, whose patriotism rested on the notion that England was the worst place on earth with the possible exception of everywhere else. The first time he uses the phrase “Never such innocence” he qualifies it with “never before or since,” suggesting that the particular Edenic aura that hangs over the prewar months of 1914 may be its own kind of illusion. To imply that Britain (or for that matter any other combatant nation) was somehow more innocent than ever on the eve of catastrophe is to register an aftereffect of the catastrophe itself.

The war was so foul and terrible that it could only have erupted in a landscape of goodness and purity. That, at any rate, is one of the myths it leaves behind. Another, favored at the time by a handful of vanguard intellectuals (notably the Italian Futurists) and adapted by some later historians, was that the war accelerated tendencies already present in modern society: toward mechanized violence, total conflict and the fusion of technology and politics.

Accounts of that summer, especially in France and Britain, frequently emphasize beautiful weather and holiday pleasures. Gabriel Chevalier’s “ Fear ,” a novel of combat published in 1930, opens with “carefree France” in its “summer costumes.” “There wasn’t a cloud in the sky — such an optimistic, bright blue sky.” A lovely example of the interplay of empirical reality and literary embellishment: the meteorological record will attest to the color and clarity of the sky, but only the cruel, corrective irony of hindsight can summon the word “optimistic.”

And then: “In a few short days, civilization was wiped out.” This brutally concise sentence, a few pages into “Fear,” summarizes the loss of innocence that subsequent chapters of first-person narration will elaborate. But those chapters will also make clear the extent to which that “civilization,” so intoxicated by its own rhetoric of national glory and heroic destiny, was the author of its own extinction. The discrepancy between that lofty language and the horrific reality of war opens a chasm in human experience that, in Fussell’s account, has never closed: “I am saying,” he wrote, “that there seems to be one dominating form of modern understanding; that it is essentially ironic; and that it originates largely in the application of mind and memory to the events of the Great War.”

More recent events, and the imaginative response to them might indicate the extent to which minds can change, and memories fade. Chevalier’s “bright blue sky” can’t help evoking a certain late-summer sky over Manhattan almost 13 years ago, at another moment that would come to mark a boundary between Before and After.

After Sept. 11, 2001, we were told — we told ourselves — that everything had changed. In a curious reversal of the logic of the Great War, the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon were widely and quickly understood to herald “the death of irony.” What this meant, at least at first, was that a cultural style dominated ( according to Roger Rosenblatt in Time , among others) by “detachment and personal whimsy” would give way to an ethic of seriousness and sincerity. But in retrospect, the obituaries for irony were not only premature; they were also part of an aggressive reassertion of innocence, a concerted attempt to refute the conclusion of Larkin’s “MCMXIV.”

There followed a rehabilitation of the abstract words that Hemingway and his lost generation had found so intolerable. Ordinary soldiers were routinely referred to as “heroes” and “warriors,” even as their deaths and injuries were kept from public view. Those at home were encouraged toward displays of patriotism and support but also urged to continue with the optimistic routines of work, leisure and shopping “as if it were all” (to quote Larkin) “an August Bank Holiday lark.”

But the Great War is not quite finished with us. As the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have wound down in bloody inconclusiveness, the men and women who served in them have started writing, and what they have produced should return us to the morning after the Somme. “ Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk ,” Ben Fountain’s award-winning 2012 novel, pushes past irony into farce as it juxtaposes the experiences of a battered platoon plunged from the chaos of Iraq into the vulgar spectacle of the Super Bowl, where their service is honored and exploited. The book belongs in the irreverent company of “Catch-22,” which is to say on the same shelf as “All Quiet on the Western Front” and Chevalier’s “Fear.”

Phil Klay’s “ Redeployment ,” meanwhile, published this year, follows in the hard-boiled, matter-of-fact line of Hemingway and “The Things They Carried.” A deceptively modest collection of linked short stories, “Redeployment” bristles with place names, military numbers and acronyms, grim humor, sexual frustration, sentimental friendship and contempt for authority. It could only have been written by someone who was there, even if “there,” with some adjustments of technology, idiom and climate, might just as well be Ypres as Ramadi. And the moral might have been written by the British memoirist Edmund Blunden, who derived a stark lesson from his own experience at the Battle of the Somme: “The War had won, and would go on winning.”

An article last Sunday about the effect World War I had on America’s cultural consciousness misidentified the era in which John Bunyan’s “The Pilgrim’s Progress” — an allegory of hardship and redemption that many British soldiers and officers were familiar with — came out. It was published in the 17th century, not during the medieval years.

How we handle corrections

October 24, 2005 | World Defense Review

The enduring consequences of the first world war, mark dubowitz.

Chief Executive

If the First World War was to be the “war to end all wars,” the Paris Peace Conference established a “peace to end all peace.” In both the scale of its devastation and in its political consequences for future generations, the 1914-1918 conflict and the settlement that followed were respectively a bad war and a bad peace. Both left an enduring legacy for future generations.

Despite the goal of a lasting peace, the post-WWI order fashioned by Wilson, Lloyd George and Clemenceau proved unviable. Disputed borders, punitive reparations compounded by global financial distress, public aversion to the use of force, growing isolationism, a political preference for appeasement over war, and belligerent German, Japanese and Italian nationalism and irredentism provided the preconditions for the outbreak of the even more devastating Second World War. The sufficient condition was provided by a German Fuhrer looking for any pretext to justify another European conflagration.

Despite the success of European integration in the post-WWII period, problems in Europe as a result of the post-WWI order remained: The violent dissolution of the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s (Europe's first genocide since WWII), the unresolved status of Kosovo, and the peaceful break-up of Czechoslovakia were the most recent manifestations.

Outside Europe, the Middle East saw conflicting promises on political inheritances and the creation of artificial states with little national identity and deep-seated ethnic and religious divisions. Compounded by decisions and events in the pre and post-WWII period, these promises have resulted in enduring problems and have exploded in hot wars (fought between Arabs, Arabs and Jews, and Arabs and the West), confrontation between the Cold War superpowers, the struggle over oil as a political weapon, and the growth and internationalization of terrorism and Islamic fundamentalism.

Today, the legacy of the First World War and the resulting territorial decisions endure with the US-led war in Iraq and the specter of the dissolution of the country into three former Ottoman provinces; the Israeli-Palestinian conflict with its seemingly irreconcilable claims; the ongoing struggle to truly liberate Lebanon from Syrian occupation; and the war of militant Islamists against the secular order.

The First World War also contributed to the Russian Revolution and the rise of revolutionary Communism, which haunted the peacemakers at Paris and future political leaders. If not for WWI, and an Imperial Russia weakened by war and economic dislocation, Russia might never have gone Communist and the USSR may never have formed as an existential threat to the democratic west.

The post-First World War era saw a focus on the ideal of collective security organizations represented by the failed League of Nations, with questions about the legitimacy and efficacy of such institutions still lingering today on the role of the UN (and to a lesser extent NATO). The decision to go to war and the peace settlements revealed the importance of the role of public opinion in the fashioning of foreign policy, both in war and in peace. With a European population increasingly pacifistic as a result of two world wars, disagreements on questions of national security between the US and European Union remain an enduring consequence of WWI and its aftermath. Finally, Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points, and its calls for self-determination, political independence and territorial integrity are still a rallying cry for nationalist independence movements worldwide.

Devastation and Pacifism

The war left almost 9.5 million combatants dead and millions more wounded, costing the Western allies alone 3.6 million lives and over $130 billion dollars, according to David Stevenson in his book, Cataclysm: The First World War as Political Tragedy. The enormity of those losses, even for the victors, propelled a shift in political and public opinion. While the European political elites and their publics initially embraced the war, when it came with such surprising ferocity and devastation on an industrial scale, opinion shifted significantly. “Those who started the First World War had expected it to resemble the short wars of their childhood, not understanding the capacity of the industrial age to deliver men and munitions endlessly to the front,” writes Robert Cooper in The Breaking of Nations: Order and Chaos in the Twenty-First Century. The resulting destruction created a deep aversion to future wars, a growing isolationism (particularly in the United States and Great Britain) and a pacifism, which found expression in policies of appeasement and an unwillingness to “bear any burden.” The First World War, “shook forever the supreme self-confidence that had carried Europe to world domination,” writes Margaret Macmillan in Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World. “Europeans could no longer talk of a civilizing mission to the world.” With a belligerent nationalism rising in Europe and Asia, the British and American publics were at their most isolationist during the 1930s (motivated in part, in the case of Britain's appeasement of Germany, by a desire to safeguard the British empire) just as the necessity of stopping fascism's rise in Germany, Italy and Japan was at its most urgent.

The Rise of Belligerent Nationalism in Europe and Asia

While the painful consequences of the world war had undermined public support in Allied countries for the future use of force, the peace treaties – with harsh financial and territorial terms including the war guilt clause; reparations from Germany of $40 billion, according to Henry Kissinger in Diplomacy (the exact figure was only arrived at two years after the Peace Conference); military disarmament; and territorial concessions – fueled a belligerent nationalist sentiment amongst the vanquished. In Europe, the allies signed peace treaties with Germany, Bulgaria, the Ottoman Empire, Austria and Hungary that were deeply unpopular in these defeated countries. While Turkey threw off the hated Sèvres peace treaty, the treaties had long-term consequences for the others: revisionism, defiance of the international order, and the rise of right-wing parties committed to avenging their losses from WWI.

In addition, the disappearance of the Hapsburg and Ottoman Empires meant that Europe now had nation states in Eastern and Central Europe, such as Romania, Poland, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia with restless minority populations. The new nation state – by definition one ethnic nation within a state – was at odds with the multiethnic makeup of the imperial state, which left minorities in the new nation state or an ethnic group's brethren in neighboring states. These new nation states proved unwilling and unable to accommodate these minority groups and became increasingly authoritarian and repressive. States like Germany, Hungary, Austria and Bulgaria became increasingly irredentist and used the protection of their brethren in other countries as a pretext for invasion of their neighbors. As this irredentism became increasingly pronounced, the Western powers did little to check it. Opposed to the use of force, they allowed Germany to march into the Rhineland and Sudetenland until it became clear that only another war could stop Hitler. In Asia, the post-WWI order left a strengthened and militaristic Japan emboldened by its victory in WWI against Russia. With Russia defeated, Japan emerged as the dominant power in Asia, which fuelled the rise of Japanese imperialist militarism. Once again, the Western powers refused to enforce promises of collective security, allowing Japan to occupy Manchuria and setting the stage for Tokyo's territorial expansionism of the 1930s.

While a common enemy had unified the allies against the Axis threat in war, divisions between the allies, on display in Paris in 1919, intensified in the 1920s and 1930s. With disunity amongst the European allies, and the US showing little interest in continuing its entanglements in Europe, the opportunity to contain Hitler and the rise of fascism, without a return to the terrible bloodshed of WWI, slipped away. While the Paris peace treaty was, as Macmillan says, “a godsend for his propaganda,” Hitler did not wage war against the Allies, the Jews and democracy because of any treaty. Rather, the Treaty of Versailles provided him with a convenient pretext around which to justify his expansionist goals. In German, Italy and Japan, in particular, peace treaties were seized on by right-wing populists committed to reversing territorial losses, challenging financial reparations, undermining fledging democracies, and, in the case of Germany, exposing the traitors who had – it was said – betrayed their nations at Paris.

In the end, the international order that the post-WWI treaties set up in Europe was destroyed by the rise of revanchist regimes in Germany, Italy, Austria, Hungary and Bulgaria, committed to war, and Allies unwilling take the difficult decision to commit force or to credibly threaten force to prevent another European conflict. The Second World War, as a result, was a consequence of “twenty years of decisions taken or not taken, not of arrangements made in 1919,” says Macmillan. In this regard, the First World War and the decisions in Paris were a necessary condition though not sufficient for the next world war to come. Setting in motion a chain of events leading to WWII, the Great War and the Paris peace conference remain defining events in the shape of the modern political order almost a century later.

The Middle East

The post-WWI developments left an imprint on the Middle East as well. The dismemberment of the Ottoman after WWI, and the establishment of British and French mandates resulted in a number of politically artificial states including Trans-Jordan, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf States. The legitimacy of the boundaries separating these states, and indeed the legitimacy of these states themselves, fueled further conflict.

Iraq never relinquished its designs on oil-rich Kuwait; Syria invaded, and occupied Lebanon while still hungrily eyeing Jordan, both of which it considered part of a greater Syria; the British (and then the Americans) struggled to hold Iraq's Kurdish, Sunni and Shia regions together; and the Sunni Hashemites and Shias throughout the region never accepted the legitimacy of Wahhabi rule in Saudi Arabia (a view reciprocated by the Wahhabis). The struggle over Palestine, with contradictory promises made by Britain to both Jews and Arabs, fueled four Arab-Israeli wars, brought the US and Soviet Union to the brink of nuclear war during the 1973 Arab-Israeli war, contributed to the use of oil and terrorism as political weapons, and was used as a pretext (amongst others) for Islamists dedicated to Israel's and the West's destruction.

Collective Security

The post First World War era also saw an emphasis on security not through the old European system of balance of power – of Metternich, Castlereagh, and the Congress of Vienna – but through the collective security of Wilson's League of Nations. Under the League of Nations, the international community would enforce the peace and commit each member state to the protection of the territorial integrity and political independence of all other member states. In the face of Republican opposition and Wilson's unwillingness to compromise with a Republican-controlled Congress, the US never joined the League and the institution proved incapable of resisting German, Japanese, and Italian territorial aggression. By providing a false sense of security to the Western powers, and a poor substitute for the military resources and power alliances required to confront German, Italian and Japanese militarism, the League also undermined the psychological readiness required to deal with the gathering storm in Europe.

While the League failed, the modern world is still living through a collective security debate on its successor organization, the United Nations. While many outside the US (and some in the US) demand the UN's imprimatur to legitimize military action by a UN member, and see the institution as an essential part of a multilateral strategy of crisis management, others disagree. They emphasize the UN's ineffectual response to genocides in Rwanda, Yugoslavia and the Sudan, the corruption revealed in the Oil-for-Food scandal, the appointment of human-rights abusers to key positions on the UN human rights commission, the litany of anti-Israel and anti-American resolutions and the UN's silence on the behavior of rogue regimes. As importantly, with the growth in influence of institutions like the International Court of Justice and International Criminal Court in the Hague, and calls from some for the UN to function as a world government, these critics refuse to permit American sovereignty and security to undermined by supranational institutions. For them, only America could guarantee its own security, in coalitions of preferred partners where desired, and alone and through pre-emption if necessary.

The Role of Public Opinion

A further enduring consequence of WWI and its aftermath is the role of public opinion in the shaping of foreign policy. The decisions and deliberations, both in rumors and in fact, of the Paris Peace Conference were reported by an international press corps. An appeal to public opinion, both as a negotiating tactic and as a genuine concern by conference delegates, was a frequent occurrence. In the post-WWI period, a public aversion to war was a crucial factor in the failure of the Western allies to confront growing fascism.

Since WWI, public opinion has remained a crucial factor in influencing policy decisions. The failures of American leaders to secure continued public support for the war in Vietnam, the difficulty in maintaining European public support for an aggressive containment strategy of the Soviet Union, the enormous European public resistance and the growing US public disillusionment to the War in Iraq – these are all examples of how wars can be won or lost on the basis of whether or not policy makers succeed in maintaining public support. Since 9/11, Jihadist terrorists have understood the role of the media, and the power that televised images of suicide bombings, roadside bombings, and beheadings can have in undermining public support for the War in Iraq.

The EU, the US and Divergent Approaches to Security

In its destruction of men, territory and economies, the First World War (reinforced by the even greater devastation of the Second World War) resulted in a European public wary of war and committed to the peaceful resolution of conflict. In the First World War, while the US had lost 114,000 men, the losses of Germany (2.037 million), Russia (1.8 million), France (1.4 million), Austria-Hungary (1.1 million), Bulgaria and Turkey (892,000), the UK (723,000) and Italy (578,000) were staggering in comparison.

After centuries of bloodshed on the continent, with reconstruction after WWII financed by the American Marshall plan and protection provided by the American military during the Cold War, old adversaries in Europe achieved reconciliation and integration. Led by France and Germany, bitter European enemies created a common market and common institutions, including a European Union, a joint currency and shared European institutions. The enduring legacy of both world wars is a Western Europe which has enjoyed over six decades of peace and integrated many Eastern and Central European countries without violence. With Yugoslavia as the glaring exception (an artificial nation that never successfully addressed the consequences of post-WWI peacemaking), Europe has been a glowing political success.

Yet transatlantic tensions between the Continent and the US (and to a lesser extent the UK) since the fall of Communism, and most pronounced over the War in Iraq, reveal the divergence between a postmodern European Union, skeptical of the use of force to protect state sovereignty and interests, and the mostly modern and still nationalistic United States, willing and capable of projecting force to protect its interests against other modern and pre-modern states and non-state actors. In Robert Kagan's formulation (Paradise and Power), a fundamental disagreement exists between a Europe focused on process, diplomacy and treaties in a “Kantian paradise” and a United States reliant on power to protect its interests in a “Hobbesian jungle.”

Policy makers like Cooper have argued for a “Third Way,” an aggressive multilateralism backed by the credible threat or application of force if necessary, a close cooperation between transatlantic allies against common threats, and a reformed and effective UN.

Despite this proposed strategic synthesis, Europe and the US still perceive and manage threats differently. Europeans see a responsible and democratic Germany, integrated into a common European destiny thanks to complex and multilateral political and economic arrangements. Americans see a Germany that was wounded in WWI, destroyed in WWII, and then rehabilitated and protected (in the case of West Germany) in the post-war period thanks to American military might and American money. As a result of these different interpretations of history, the enduring legacy of a 20th century of devastating world wars, which began with the industrialization of death in WWI and which still influences a pacifistic European public today, will likely shape diverse national security approaches for the foreseeable future.

In its brutality on the battlefield, and its far-reaching political consequences, the First World War scarred combatants, civilians, and politicians as well as generations since who continued to struggle with its enduring legacy. Today, with Kosovo, a UN protectorate in the heart of Europe; the festering conflicts in the Middle East and Africa; Chinese-Japanese antagonism in East Asia; significant skepticism about the legitimacy and efficacy of collective security institutions like the UN; transatlantic disagreements over the use of force; and a battle for public opinion in the media no less important than the war on the ground, the modern world is still living through a post-WWI conjuncture.

— Mark Dubowitz is the chief operating officer of the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies (FDD) in Washington, D.C. Currently a candidate for a Masters in International Public Policy in Chinese studies at The Johns Hopkins University's School of Advanced International Studies, Dubowitz has combined JD/MBA degrees from the University of Toronto and has also studied at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Ecole Supèrieure de Commerce de Paris and McGill University. He speaks three languages and has lived in the Middle East, Europe, Africa and North America. The Foundation for the Defense of Democracies is a policy institute focused on promoting democratic values and defeating terrorist ideologies.

- Curriculum Development Team

- Content Contributors

- Getting Started: Baseline Assessments

- Getting Started: Resources to Enhance Instruction

Getting Started: Instructional Routines

- Unit 9.1: Global 1 Introduction

- Unit 9.2: The First Civilizations

- Unit 9.3: Classical Civilizations

- Unit 9.4: Political Powers and Achievements

- Unit 9.5: Social and Cultural Growth and Conflict

- Unit 9.6: Ottoman and Ming Pre-1600

- Unit 9.7: Transformation of Western Europe and Russia

- Unit 9.8: Africa and the Americas Pre-1600

- Unit 9.9: Interactions and Disruptions

- Unit 10.0: Global 2 Introduction

- Unit 10.1: The World in 1750 C.E.

- Unit 10.2: Enlightenment, Revolution, and Nationalism

- Unit 10.3: Industrial Revolution

- Unit 10.4: Imperialism

- Unit 10.5: World Wars

- Unit 10.6: Cold War Era

- Unit 10.7: Decolonization and Nationalism

- Unit 10.8: Cultural Traditions and Modernization

- Unit 10.9: Globalization and the Changing Environment

- Unit 10.10: Human Rights Violations

- Unit 11.0: US History Introduction

- Unit 11.1: Colonial Foundations

- Unit 11.2: American Revolution

- Unit 11.3A: Building a Nation

- Unit 11.03B: Sectionalism & the Civil War

- Unit 11.4: Reconstruction

- Unit 11.5: Gilded Age and Progressive Era

- Unit 11.6: Rise of American Power

- Unit 11.7: Prosperity and Depression

- Unit 11.8: World War II

- Unit 11.9: Cold War

- Unit 11.10: Domestic Change

- Resources: Regents Prep: Global 2 Exam

- Regents Prep: Framework USH Exam: Regents Prep: US Exam

- Find Resources

10.5 Enduring Issues Check-in

Getting Started

Enduring Issues Check-In: Enduring Issues Check-Ins

Teacher Feedback

Please comment below with questions, feedback, suggestions, or descriptions of your experience using this resource with students.

If you found an error in the resource, please let us know so we can correct it by filling out this form .

- Upload Document

- Public Docs & Collections

- Free Accounts

- Videos and Overviews

- Tech Support

Please choose from the list of thinking partners to the left

Description

Choose a tab, then select your Thinking Partner

Remember: Everything the GPT Thinking Partners say is made up! Edit the AI results before you hit Start Conversation. Revise the message to make it helpful (to other readers), honest (about any facts) and harmless (avoiding biases).

Which is more helpful, honest, and harmless?

Resubmission

Add comment at:.

Format: HH:MM:SS

Invalid Timestamp

Enduring Issues Essay Bundle Gl4 WWI - Cold War

0 changes , most recent less than a minute ago.

Part III (Question 35)

ENDURING ISSUES ESSAY

This question is based on the accompanying documents. The question is designed to test your ability to work with historical documents. Some of these documents have been edited for the purposes of this question. As you analyze the documents, take into account the source of each document and any point of view that may be presented in the document. Keep in mind that the language and images used in a document may reflect the historical context of the time in which it was created.

Directions : Read and analyze each of the five documents and write a well-organized essay that includes an introduction, several paragraphs, and a conclusion. Support your response with relevant facts, examples, and details based on your knowledge of social studies and evidence from the documents.

An enduring issue is a challenge or problem that has been debated or discussed across time. An enduring issue is one that many societies have attempted to address with varying degrees of success.

• Identify and define an enduring issue raised by this set of documents

• Argue why the issue you selected is significant and how it has endured across time

In your essay, be sure to

• Identify the enduring issue based on a historically accurate interpretation of at least three documents

• Define the issue using relevant evidence from at least three documents

• Argue that this is a significant issue that has endured by showing:

– How the issue has affected people or has been affected by people

– How the issue has continued to be an issue or has changed over time

• Include relevant outside information from your knowledge of social studies

In developing your answer to Part III, be sure to keep these explanations in mind:

Identify —means to put a name to or to name.

Define —means to explain features of a thing or concept so that it can be understood.

Argue —means to provide a series of statements that provide evidence and reasons to support a conclusion.

Global Hist. & Geo. II – Jan. ’20 [24]

Global 4 Documents for Essay

OPTIONAL PLANNING PAGE

Enduring Issues Essay Planning Page

You may use the Planning Page organizer to plan your response if you wish, but do NOT write your essay response on this page. Writing on this Planning Page will NOT count toward your final score.

My Enduring Issue is:__________________________________________________________________

Refer back to page 24 to review the task.

Write your essay on the lined pages in the essay booklet.

Global Hist. & Geo. II – Jan. ’20 [31] [OVER]

DMU Timestamp: November 12, 2020 20:50

0 General Document comments 0 Sentence and Paragraph comments 0 Image and Video comments

Comments are due December 21, 2020 00:00

You've made 0 of the 5 requested

0 archived comments

Thanks for sharing valuable info. I have been looking for a long time where I can write my papers. And this is what I managed to find https://www.devdiscourse.com/article/agency-wire/2145325—write-an-essay-for-me-custom-writing-services—-reviewed where I found a review of the best writing service. When it comes to academic assignments, I think it is better to entrust it to qualified professionals.

As only 2.8 square miles survived the Atomic bomb out of 6.9 miiles. Hiroshima became a be-rend land asoonest the bomb ended. Releasing toxic waste

How many bombs where dropped on Hiroshima?

1962 How was soviets able to have a nuclear site in cuba. when U.S had leased most of the land?

The US controlled much of the land in Cuba when Batista was in power. But after Castro’s revolution the Americans were limited to Guantanamo Bay

he following year, a direct “hot line” communication link was installed between Washington and Moscow to help defuse similar situations, and the superpowers signed two treaties related to nuclear weapons.

The Soviet Union attempt to stop the U.S from supplying the Americans in the city failed, the Soviet Union also lost their standoff with Kennedy, and wound up withdrawing from the war with Afghanistan.

Did Marshalls policy, led to Russia’s opening up their border in West Berlin. Lifting much of the hate from the allies

This makes me wonder because after the 13 days of standoff between the Soviet and John F. Kennedy. Russia dismantles the nuclear missiles, avoiding another mass casualty.

That in term to managing themselves this made china become so wealthy yet technological behind by not being influence at social modernity

The economic and technology systems were backwards because China had been under the rule of foreigners and warlords for a number of years. China lacked the stability to thrive economically and technologically. What Enlightenment ideal was violated by the foreigners and warlords?

For the science and technology of modern Taiwan, see Ministry of Science and Technology (Republic of China).

Why was the Chinese so advanced? What did the have that we didn’t?

This is when Russia started to take over weaker populations for more resources

That during 1989 Cuba was accustomed to women doing household chores

Income inequality in the United States expanded from 2017 to 2018, with several heartland states among the leaders of the increase, even though several wealthy coastal states still had the most inequality overall, according to figures released Thursday by the U.S. Census Bureau.

General Document Comments 0

- Join an existing conversation — click the “Reply” button of the appropriate right pane comment

- Start a new conversation on an existing area — Double click on the existing highlighted area or its comment balloon

- Define and comment on a new area — Draw a box around the desired area by clicking and then holding + dragging your mouse

Quickstart: Commenting and Sharing

- Desktop/Laptop: double-click any text, highlight a section of an image, or add a comment while a video is playing to start a new conversation. Tablet/Phone: single click then click on the "Start One" link (look right or below).

- Click "Reply" on a comment to join the conversation.

- "Upload" a new document.

- "Invite" others to it.

- Constitution

- Staff and Directors

- SGR Patrons

- Funding policy

- 30th anniversary

- Martin Ryle Trust

- Annual reports

- Environmental policy

- Affiliations

- Data Protection

- Climate change & the military

- Fair Lifestyle Targets

- Nuclear weapons threat

- Globally Responsible Careers

- Science oath for the climate

- Military influence on science & technology

- Corporate influence on science & technology

- AI & robotics

- Arms conversion for a sustainable society

- Science4Society Week

- One Planet One Life

- Other projects

- Security and disarmament

- Climate change and energy

- Who controls science and technology?

- Emerging technologies

- Other issues

- Reports and briefings

- Responsible Science Journal

- SGR Newsletters

- SGR conferences

- Other events

- Forthcoming events

Dr Stuart Parkinson, SGR, examines how technological innovation contributed to one of the most devastating wars in human history – and asks what lessons we should take from this.

Article from SGR Newsletter no.44; online publication: 5 April 2016

Download pdf of article

2016 is the centenary of two of the bloodiest battles of World War I: the Somme and Verdun. And WWI itself is one of the most destructive wars in human history. As an example of the carnage, the total death toll of the war has been estimated at over 15 million people between July 1914 and November 1918 – an average of about 3.5m per year. Only the Russian Civil War and World War II had higher annual death rates. [1] [2] The centenary is therefore an important opportunity to reflect on a conflict in which rapid developments in technology led to a huge increase in the devastation that could be caused by war.

In this article, I examine which technological developments led to the most casualties and what lessons we can draw about science, technology and the military today.

Harnessing the Industrial Revolution for war

The late 18th and 19th centuries saw a rapid development in technology which we now, of course, refer to as the Industrial Revolution. Starting in Europe, major developments transformed a wide range of industries. Growing exploitation of minerals like coal and iron were especially important, as was the advent of the steam engine – especially in ships and trains.

It was not long before the military started harnessing some of these inventions. Mass production in factories churned out not only large numbers of standardised guns and bullets, but also boots, uniforms and tents. [3] The guns were more reliable and hence more accurate. A bullet was 30 times more likely to strike its target. Developments in transport were also utilised, with steel becoming standard in battleships and trains starting to be used to quickly ferry large numbers of troops to war zones. Advances in chemistry led to new high explosives.

The first wars in which these new military technologies were used on a large scale included the Crimean War (1854-56) and the American Civil War (1861-65). Both of these provided a taster for the carnage of WWI, being characterised by trench warfare in which frontal assaults against well-defended positions led to massacres of infantry soldiers.

Pre-1914 arms races

In the years running up to the outbreak of WWI, there were several key developments in military technologies that would lead to high casualties during the war itself.

Arguably the most important were new high explosives. Gunpowder had been the explosive of choice in war for around 500 years, but new developments in organic chemistry by Alfred Nobel and others led to new materials, initially used in mining. Further work in the late 19th century especially in Prussia/Germany, Britain and France refined the materials for use in hand-guns and artillery. Most successful were Poudre B and Cordite MD which burnt in such a way as to provide the required directed pressure needed to propel a projectile, without blowing up the weapon. [4]

Developments in gun manufacture were also crucial. Muskets were being replaced by rifles, which were more accurate. Machine guns were also brought onto the scene, first invented in the USA. By 1914, the most widely used machine gun was the British Maxim, capable of firing a shocking 666 rounds per minute. [5]

New artillery was also developed to use the new explosives. By the outbreak of WWI, a single shell weighing one tonne could be propelled more than 30 kilometres. However, smaller and more mobile guns were preferred as these could accurately fire a shell every three seconds. [6]

The development of weapons using poisonous gases was limited by the Hague peace conference of 1899. However, this only limited the development of the delivery systems rather than the gases themselves, in which Germany, Britain and France all had active research programmes. [7]

The development of the submarine and the torpedo would also prove to be crucial. Work in France and the USA led to the first successful military submarines, with Britain, Germany and Italy quickly commissioning their own. At the start of the 20th century, there were about 30 military submarines. This number would rapidly grow. The main weapon of the submarine immediately became the torpedo, invented in Britain. An early demonstration of the effectiveness of this weapon was in a Japanese attack on the Russian fleet in 1904. It was then rapidly deployed by all the major powers. [8]

The other major development in military technology that occurred in the years running up to 1914 was the steam-driven battleship. The first was the Dreadnought , launched by the British in 1906. Heavily armed and fast, it helped to cement Britain’s naval dominance. However, other naval powers, especially Germany, developed their own more powerful battleships during a rapid naval arms race in the pre-war years. [9]

Helping to fuel these arms races were not just competition between national militaries and technological innovation, but also international commerce. Major private corporations such as Vickers and Armstrong in the UK and Krupp in Germany made huge profits from arms sales, including major contracts with governments which would later become the ‘enemy’. [10]

Key technological developments during the war

After WWI broke out, in summer 1914, the pressure rapidly grew for the warring nations and their scientists and engineers to try to create ‘military advantage’ through innovation. The main areas were diverse, including trench construction, artillery and its targeting, poisonous gases, submarines, tanks and planes.

In terms of artillery, perhaps the most important development during the war was the scaling up of production of the heavy guns which had begun to be deployed by militaries before 1914. Many thousands of these weapons, such as the British 18 Pounder and the French 75mm, were produced. [11] Also important was the development of improved targeting – such as ‘sound-ranging’. These developments led to artillery use on an unprecedented scale. For example, during the Meuse-Argonne campaign – part of the final Allied advance in 1918 – US forces were firing an incredible 40,000 tonnes of shells each day . [12]

Mass production also led to the machine gun being a widely used and devastating weapon, especially in defending trenches. For example, the British favoured the Lewis gun whose numbers increased nine-fold between 1915 and 1918. [13]

German research resulted in the first use of lethal gas in the war – in this case, chlorine – in April 1915. [14] Further development work led to Germany deploying phosgene and mustard gas later in the war. Britain’s first use of lethal gas was in September 1915, although it never used it on the scale that Germany did. However, poisonous gases proved to have limited military value – due to their dependence on weather conditions and their countering through, for example, gas masks. Gases also proved to be significantly less lethal than more conventional weapons. [15]

There was rapid development of military aircraft during WWI, although their role in the conflict remained largely marginal. [16] Planes and airships were adapted to drop bombs, but their main role was reconnaissance, especially spotting the location of enemy artillery.

Submarine development also proceeded quickly during WWI. Germany, in particular, favoured this sort of weapons system, given British superiority in surface warships. By the war’s end they had built 390 ‘U-boats’, and used them to devastating effect, especially from early 1917 onwards when they resorted to ‘unrestricted’ submarine warfare to try to cut off Britain’s maritime supply routes. About four million tonnes of shipping – much of it crewed by civilians – was sunk in little over a year. [17]

In military terms, arguably the most decisive new technology of the war was the tank. First deployed by Britain in 1916 with the aim of overrunning trenches defended by barbed wire and machine guns, it did not initially prove effective. However, further innovation and mass production led to Britain and France each deploying several hundred from the summer of 1918. They proved critical in driving back German forces. [18]

Which weapons were the biggest killers?

Estimating casualty rates in war is a notoriously difficult exercise, especially when analysing data from a century ago. Nevertheless, World War I historians and other researchers have uncovered a range of information which allows some assessment to be made of the most lethal technologies.

Overall, based on a range of sources, researcher Matthew White has estimated that approximately 8.5 million military personnel and around 6.5m civilians died in World War I. [19] Wikipedia researchers have provided comparable estimates. [20]

Within the military totals, the overwhelming majority of deaths (and injuries) were borne by armies, with naval deaths being only a few percent of the total. [21] Of land-based deaths, the evidence points to artillery being by far the leading cause, followed by machine guns. For example, historians Stephen Bull, [22] Gary Sheffield, [23] and Stephane Audoin-Rouzeau [24] quote a range of official figures that indicate between 50% and 85% of casualties on the battlefield were due to artillery fire.

Civilian deaths – which are much less certain – were overwhelmingly caused by malnutrition and disease, as a result of shortages due to the effect of battlefields, blockades and damage to infrastructure caused by the war. Hence, no single weapons system can be identified as the cause in those cases. Nevertheless, artillery and machine gun fire still resulted in large numbers of civilian casualties.

Drawing on sources already quoted, I estimate the following overall numbers of deaths due to different weapons systems. I must emphasise these have high levels of uncertainty.

- Artillery: 6m (5m military and 1m civilian)

- Machines guns: 3m (2m military and 1m civilian)

- Submarines; rifles: 0.5m each

- Tanks; chemical weapons; warships; planes: 0.1m each

A further 5m civilians are thought to have died due to malnutrition and disease.

Some lessons

Lessons from the carnage of the World War I continue to be hotly debated, but I want to offer some especially related to science and technology.

Historian John Keegan points out that there was rapid technological development in weapons systems in the years before WWI, in contrast to that in communications. [25] As such, the means to wage war on an unprecedented scale was readily at hand when the international political crisis struck in summer 1914, whereas technologies which political leaders could use to clarify and defuse the situation (e.g. high quality person-to-person phones) were not.

Today, the rapid pace of development in communications technologies is outpacing much in the military field – indicating that perhaps some lessons have been learned about the importance of communication in helping different peoples understand and trust one another. However, militaries are harnessing some of those communications technologies to help revolutionise warfare, an obvious example being the remote piloting of ‘drones’. New international arms controls are urgently needed in this area.

This brings me to another key lesson. 100 years on from the Battle of the Somme, artillery is still being used to devastating effect in many parts of the world – with the carnage of the Syrian war being an obvious example. Campaigners are attempting to get their use restricted under existing international disarmament treaties, but governments are currently showing little interest. [26]

A further lesson concerns the international arms trade. A lack of controls in the years before WWI allowed private corporations to profit from arming both sides. While a new international Arms Trade Treaty was agreed in 2013, its currently weak provisions still allow a major trade which fuels war and repression across the world. [27]

The overarching conclusion is that allowing militaries to play a significant role in scientific research and technological development was a major driver of world war 100 years ago, and it still creates major dangers today. We need to prioritise using science and technology to support and strengthen disarmament processes across the world – that would be the best way of commemorating the fallen from the century past.

Dr Stuart Parkinson is Executive Director of Scientists for Global Responsibility, and has written widely on the links between science, technology and militarism.

Thanks to Daniel Cahn for valuable help with research for this article.

[1] Figures and calculations based on data from: White M (2011). Atrocitology. Canongate, London. Death rate of World War II (1939-45): approx 6.5m/y; Russian Civil War (1918-20): approx 4m/y.

[2] See also figures in: Wikipedia (2015). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/World_War_I_casualties

[3] p295 of: White (2011) – as note 1.

[4] Chap. 14 of: Williams T (1999). A history of invention: from stone axes to silicon chips. TimeWarner books.

[5] As note 4.

[6] As note 4.

[7] Bull S (2014). Trench: A History of Trench Warfare on the Western Front. Osprey Publishing.

[8] As note 4.

[9] As note 4.

[10] On the Record/ Campaign Against Arms Trade (2014). Arming All Sides. http://armingallsides.on-the-record.org.uk/

[11] History Learning Site (undated). http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/artillery_and_world_war_one.htm

[12] McKenny J (2007). The Organizational History of Field Artillery: 1775-2003. US Government Printing Office.

[13] Sheffield G (ed.) (2007). War on the Western Front. Osprey Publishing.

[14] As note 7.

[15] As note 7.

[16] As note 4.

[17] p.361 of: Keegan J (1998). The First World War. Random House.

[18] As note 4.

[19] As note 1.

[20] As note 2.

[21] As note 2.

[22] As note 7.

[23] As note 13.

[24] Audoin-Rouzeau S (2012). Combat. Pp.173-187 in: Horne J (2012). A Companion to World War I. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

[25] As note 17.

[26] Article 36 (2011). http://www.article36.org/explosive-weapons/introduction-explosive-weapo…

[27] War Resisters International (2013). http://www.wri-irg.org/node/21654/

Filed under:

- Have your assignments done by seasoned writers. 24/7

- Contact us:

- +1 (213) 221-0069

- [email protected]

How to Write an Enduring Issues Essay: Guide with Topics and examples

Writing Enduring Issues Essay

Writing an enduring issues essay is not easy. You must discuss a topic that can get people to discuss and think long after they read your paper.

This guide will teach you how to write an enduring issues essay. You will find the topics list and examples of each one. In addition, we go over the different types of essays used for this purpose and give you a brief overview.

What is an Enduring Issues Essay?

An enduring issues essay is a written task where the author identifies and describes a historically significant challenge that endured for a long duration and has been addressed with different degrees of success.

You should describe the challenge, explain why it has endured and how different people successfully addressed it at different times.

Mostly, this can be either by a group or an individual, but it must be historically significant so that the argument you present can be backed up with historical evidence.

An enduring issues essay is a written task where you are to identify and describe a historically significant challenge that has endured over time and has been addressed with varying degrees of success.

For example, if you were asked to write an enduring issues essay on women’s rights in America, you would need to determine if women’s rights have improved or not since the beginning of the nation.

You could then compare these results from past times with present-day trends. This task can happen by looking at how women were treated in colonial times compared to now.

You could also compare them to those who came before us, such as those who were slaves during slavery, compared to today’s race relations which do not discriminate based on race but rather on merit.

Typically, an enduring issues essay allows for historical analysis to see how our society has changed over time and what is still relevant today.

How to Write an Enduring Issues Essay

1. choose your topic.

When you are writing an essay, you need to choose a topic that is interesting and interesting enough to draw the attention of your readers. The topic should be something that can get discussed in several different ways.

To ensure that your essay is successful, it needs a clear structure.

An outline will help you plan exactly what you want to say in each section of your essay and how they relate to one another. In addition to planning your essay, several tips can help you write an enduring issues essay.

First, write down some ideas for the essay. Write down what questions or topics you would like to discuss; for example, if you wanted to write about global warming in your essay, then write down all the things happening worldwide on this issue.

You must consider something that impacts everyone, not just someone specific or something local such as pollution.

Next, think about where these ideas come from. For example: do you have friends who are interested in this issue? Can they help you find information about it? Can they give examples of others who have written about this topic before?

2. Choose your Thesis Statement

The best way to write an enduring issues paper is to start with a thesis statement. This sentence or two summarizes your argument and explains why you are writing.

The thesis statement should be a strong one that states your main point clearly and concisely but also broad enough to encompass many other points of view. It should be like: “All of us need to find ways to improve our communication skills.”

You can then support this thesis by using examples from your own life or others in your family, school or community. You might also use statistics or other research materials from books or online resources, such as Wikipedia.

3. Write your Introduction

You should write your introduction in an engaging and emotional tone. You can achieve this by writing about a personal connection, experience or something that makes you feel strongly about the issue.

If you are writing about a social issue, discussing how it affects people and what it means for those involved or affected by it is important.

You can use examples to illustrate this point and help your readers understand the importance of your argument.

For example:

In this essay, I will discuss how climate change is affecting our future generations by highlighting some of the problems they face due to climate change, such as rising sea levels and ocean acidification, droughts and wildfires, extreme weather events and food shortages (Klein and Sams).

In addition, I will discuss how we can tackle these issues by implementing new technologies that reduce carbon emissions and help us adapt to climate change (Klein and Sams).

4. Include body sections

The body section is where you will elaborate further on the issue, giving examples and evidence that support your argument. You may also include an additional supporting quote if you have any. The body section should be no less than three paragraphs long.

The essay’s body sections should explain each issue’s causes and effects. The body section should not be longer than three paragraphs unless you are going for a detailed explanation of your chosen topic.

A good way to structure your body section is by using a question-and-answer format. You can ask yourself questions such as: ‘What are the causes?’ or ‘How does it affect me?’ and answer them with your own opinion or research findings.

The body section is where you need to explain what you have learned about the topic and why it matters to you personally. You can use quotes from others who have experienced similar problems or relevant statistics on how many people are affected by these issues worldwide.

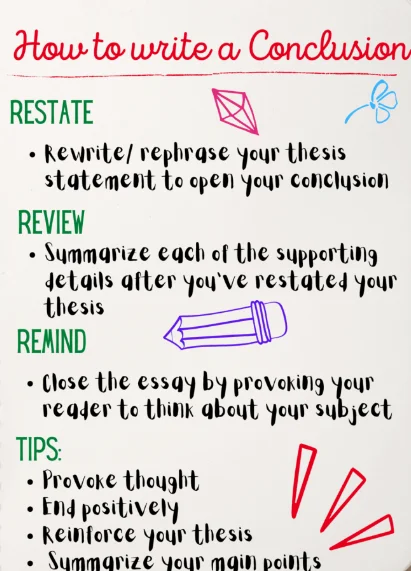

5. Conclusion

The conclusion is the final part of a written essay, which can be either a paragraph or a point, and it should give you a summary of your main points. It should not be too long and should include some conclusion statement.

The conclusion is the last line of your essay that summarizes all the points previously discussed in your writing. The best way to conclude an essay is by stating your main points, followed by an explanation.

Enduring Issues Essay Example Topics

A) climate change.

For example;

The issue of climate change has been a topic that has been discussed in the past and will continue to be discussed in the future.

Climate change is a global phenomenon affecting all parts of Earth’s life. It is caused by human activities such as fossil fuel burning, deforestation and agriculture. It devastates agriculture, water supply, food production and human health.

The causes of climate change can be attributed to human activities such as fossil fuel burning, deforestation and agriculture (UNFCCC).

Fossil fuels are the main contributors to greenhouse gases (GHG) which are responsible for trapping heat within the atmosphere through a process known as radiative forcing.

Deforestation is another cause of climate change as it contributes to land-use changes, which results in increased carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions into the atmosphere.

Agriculture contributes to CO2 emissions because it releases methane gas into the atmosphere when animals eaten by humans are released back into the environment after being consumed by humans.

Climate change has serious consequences for all life on earth, including humans, who have become a major contributor to climate change through their consumption habits, such as over-fishing or consuming meat from animals raised using non-sustainable practices such as intensive farming methods and fertilizers.

b) The Great Depression

One example of this kind of essay is “The Great Depression,” which was written by John Steinbeck in 1939. In this essay, he talked about how people worldwide suffered during this time because they had no jobs, money or food.

He also talked about how people turned to crime to survive financially, which brought down society’s values even more than before.

c) The Nazi Holocaust

Another example would be “The Nazi Holocaust” by Hannah Arendt, which discusses the systematic genocide done by Adolf Hitler’s Nazi party against Jews during World War II.

In this essay, she talks about how many German citizens were happy when Hitler took control of their country because they thought it would bring glory to Germany again after losing wars with other countries such as France.

With over 10 years in academia and academic assistance, Alicia Smart is the epitome of excellence in the writing industry. She is our chief editor and in charge of the writing department at Grade Bees.

Related posts

Chegg Plagiarism Checker

Chegg Plagiarism: Review of Chegg Plagiarism Checker and its Service

Titles for Essay about Yourself

Good Titles for Essays about yourself: 31 Personal Essay Topics

How to Write a Diagnostic Essay

How to Write a Diagnostic Essay: Meaning and Topics Example

Enduring Issues Paragraph- Causes of World War 1 (Militarism)

- Google Docs™

Description

A perfect activity for students to assess their understanding of long-term WWI causes and practice their Enduring Issues skills without writing an entire essay! Students will analyze military spending leading up to Word War I.

Social Studies Practices:

A. Gathering, Interpreting, and Using Evidence

1. Define and frame questions about events and the world in which we live, form hypotheses

as potential answers to these questions, use evidence to answer these questions, and

consider and analyze counter-hypotheses.

3. Analyze evidence in terms of content, authorship, point of view, bias, purpose, format, and

5. Make inferences and draw conclusions from evidence.

6. Deconstruct and construct plausible and persuasive arguments, using evidence.

7. Create meaningful and persuasive understandings of the past by fusing disparate and

relevant evidence from primary and secondary sources and drawing connections to the

B. Chronological Reasoning and Causation

1. Articulate how events are related chronologically to one another in time and explain the

ways in which earlier ideas and events may influence subsequent ideas and events.

2. Identify causes and effects using examples from different time periods and courses of study

across several grade levels.

3. Identify, analyze, and evaluate the relationship between multiple causes and effects

4. Distinguish between long-term and immediate causes and multiple effects (time, continuity,-

and change).

5. Recognize, analyze, and evaluate dynamics of historical continuity and change over periods

of time and investigate factors that caused those changes over time.

6. Recognize that choice of specific periodizations favors or advantages one narrative, region,

or group over another narrative, region, or group.

7. Relate patterns of continuity and change to larger historical processes and themes.

8. Describe, analyze, evaluate, and construct models of historical periodization that historians

use to categorize events.

Questions & Answers

The marvelous miss g.

- We're hiring

- Help & FAQ

- Privacy policy

- Student privacy

- Terms of service

- Tell us what you think

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

A correction was made on. June 29, 2014. : An article last Sunday about the effect World War I had on America's cultural consciousness misidentified the era in which John Bunyan's "The ...

This enduring issue essay is formatted as it appears on the NYS Regents exam. It can be completed by students after covering the causes of World War I. Documents include: - Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. - Cartoon depicting the unification of Germany and dissolution of Austria-Hungary. - Charts and a reading passage on the ...

A further enduring consequence of WWI and its aftermath is the role of public opinion in the shaping of foreign policy. The decisions and deliberations, both in rumors and in fact, of the Paris Peace Conference were reported by an international press corps. An appeal to public opinion, both as a negotiating tactic and as a genuine concern by ...

Enduring Issue Essay Sample. This question is based on the accompanying documents. The question is designed to test your ability to work with historical documents. Some of these documents have been edited for the purposes of this question. As you analyze the documents, take into account the source of each document and any point of view that may ...

A Detailed Enduring Issues Essay Outline. This enduring issues essay outline is a possible solution to help you develop the constructed response questions. In 90% of cases, a paper on enduring problems is an extended essay. It means it can be a 2-3-page piece with a more complicated structure than a simple essay. Here is a basic structure of an ...

Enduring Issues Essay Prewriting Process: How to Annotate and Contextualize Documents, Identify an Enduring Issue, and Construct a Pre-Writing Chart A process for students to follow when preparing to write an Enduring Issues Essay sketched out step-by-step. Resources:

In this video, Mr. Cellini explains how to write strong introduction, body, and conclusion paragraphs for the Enduring Issues Essay task found on the Global ...

Enduring Issues Essay) on this exam after each question has been rated the required number of times as specified in the rating guides, regardless of the final exam score. Schools are required to ensure that the raw scores have been added correctly and that the resulting scale score has been determined accurately.

The procedures on pages 2 and 3 are to be used in rating papers for this examination. More detailed directions for the organization of the rating process and procedures for rating the examination are included in the Information Booklet for Scoring the Regents Examination in Global History and Geography II. Rating the CRQ (open-ended) Questions.

10.5 Enduring Issues Check-in | New Visions - Social Studies. Unit 10.5: World Wars.

Document that houses resources related to the Enduring Issues Essay including Enduring Issues and Questions List, the prompt, description of question alignment to the Enduring Issues, identification of resources in each unit related to Enduring Issues, a progression of skills related to the Enduring Issues Essay, and a list of instructional strategies to engage students and give equal access ...

World War I, an international conflict that in 1914-18 embroiled most of the nations of Europe along with Russia, the United States, the Middle East, and other regions. The war pitted the Central Powers —mainly Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Turkey —against the Allies—mainly France, Great Britain, Russia, Italy, Japan, and, from 1917 ...

In this video, Mr. Cellini reads and analyzes the five documents as part of the enduring issues essay from the June 2019 Regents in Global History and Geogra...

In your essay, be sure to. • Identify the enduring issue based on a historically accurate interpretation of at least three documents. • Define the issue using relevant evidence from at least three documents. • Argue that this is a significant issue that has endured by showing:

Practice the skills needed for the enduring issues essay. NYS Social Studies Framework: Key Idea 10.7 DECOLONIZATION AND NATIONALISM (1900-2000) : Nationalism and decolonization movements employed a variety of methods, including nonviolent resistance and armed struggle. Tensions and conflicts often continued after independence as new ...

News. The industrialisation of war: lessons from World War I. Dr Stuart Parkinson, SGR, examines how technological innovation contributed to one of the most devastating wars in human history - and asks what lessons we should take from this. Article from SGR Newsletter no.44; online publication: 5 April 2016.

2. Choose your Thesis Statement. The best way to write an enduring issues paper is to start with a thesis statement. This sentence or two summarizes your argument and explains why you are writing. The thesis statement should be a strong one that states your main point clearly and concisely but also broad enough to encompass many other points of ...

A perfect activity for students to assess their understanding of long-term WWI causes and practice their Enduring Issues skills without writing an entire essay! Students will analyze military spending leading up to Word War I.Social Studies Practices:A. Gathering, Interpreting, and Using Evidence1. ...

An enduring issue is a challenge or problem that a society has faced and debated or discussed across time. An enduring issue is one that many societies have attempted to address with varying degrees of success. Enduring Issues are often nested, e.g., conflict (war, competition, armed struggle, resistance, invasions, threats to balance of power ...

PART 3—EXTENDED ESSAY An enduring issue is an issue that exists across time. It is one that many societies have attempted to address with varying degrees of success. In your essay Identify and define an enduring issue raised by this set of documents. Using your knowledge of Social Studies and evidence from the documents, argue why the issue you selected is significant and how it has endured ...

Resource: Enduring Issues Essay Resource: Enduring Issues Outline and Checklist. Regents Readiness. Resources: Regents Prep: Global 2 Exam. Resources for Part III: Enduring Issues Essay: Enduring Issues Essay Outline and Grading Checklist. Preview Resource Add a Copy of Resource to my Google Drive. File. Google Doc.

Allison Valenti Mrs. Gualtiere Global II Friday, February 12, 2021 World War I Enduring Issues Essay Conflict is a serious disagreement or argument. There can be conflict between individuals, groups of people, and even nations. Many treaties were made after WWI concluded as a way to stop further conflict. A treaty is a formally concluded and ratified agreement between countries.