William “Boss” Tweed and Political Machines

Written by: Bill of Rights Institute

By the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain the similarities and differences between the political parties during the Gilded Age

Suggested Sequencing

Use this Narrative with the Were Urban Bosses Essential Service Providers or Corrupt Politicians? Point-Counterpoint and the Cartoon Analysis: Thomas Nast Takes on “Boss Tweed”, 1871 Primary Source to give a full picture of political machines and their relationship with immigrants.

New York was a teeming place after the Civil War. The city’s unpaved streets were strewn with trash thrown from windows and horse manure from animals pulling carriages. Black smoke clogged the air, wafted from the burning coal and wood that heated homes and powered factories. Diseases like cholera and tuberculosis thrived in the unhealthy environment. More than one million people were crowded into the city; many in dilapidated tenements. Poverty, illiteracy, crime, and vice were rampant problems for the poor, and for the Irish and German immigrants who made up almost half the population. The city government offered a very few basic services to alleviate the suffering, and churches and private charities were often overwhelmed by the need. One politician discovered how to provide these services and get something in return.

William Magear “Boss” Tweed was the son of a furniture maker. From an early age, Tweed discovered he had a knack for politics, with his imposing figure and charisma. He soon began serving in local New York City political offices and was elected alderman for the Seventh Ward, joining the so-called 40 thieves who represented the city wards. He served a frustrating term in Congress during the sectional tensions of the 1850s and then happily returned to local politics, where he believed the action was. He quickly became one of the leading politicians in New York City, and one of the most corrupt.

William Tweed, the “boss” of Tammany Hall, played a major role in New York City politics during the mid-1800s.

By the late 1850s, Tweed had ascended through a variety of local offices, including volunteer firefighter, school commissioner, member of the county board of supervisors, and street commissioner. He learned to make political allies and friends and became a rising star. His friends selected him to head the city’s political machine, which was representative of others in major American cities in which a political party and a boss ran a major city. In New York City, Tammany Hall was the organization that controlled the Democratic Party and most of the votes.

One of Tweed’s first acts was to restore order after the New York City draft riots in 1863, when many Irishmen protested the draft while wealthier men paid $300 to hire substitutes to fight in the war. Tweed engineered a deal in which some family men (rather than just the rich) received exemptions and even a loan from Tammany Hall to pay a substitute. He had won a great deal of local autonomy and control, which the federal government had to accept. In 1870, the state legislature granted New York City a new charter that gave local officials, rather than those in the state capital in Albany, power over local political offices and appointments. It was called the “Tweed Charter” because Tweed so desperately wanted that control that he paid hundreds of thousands of dollars in bribes for it.

The corrupt “Tweed Ring” was raking in millions of dollars from graft and skimming off the top. Tweed doled out thousands of jobs and lucrative contracts as patronage, and he expected favors, bribes, and kickbacks in return. Some of that money was distributed to judges for favorable rulings. Massive building projects such as new hospitals, elaborate museums, marble courthouses, paved roads, and the Brooklyn Bridge had millions of dollars of padded costs added that went straight to Boss Tweed and his cronies. Indeed, the county courthouse was originally budgeted for $250,000 but eventually cost more than $13 million and was not even completed. The Tweed ring pocketed most of the money. The ring also gobbled up massive amounts of real estate, owned the printing company that contracted for official city business such as ballots, and received large payoffs from railroads. Soon, Tweed owned an extravagant Fifth Avenue mansion and an estate in Connecticut, was giving lavish parties and weddings, and owned diamond jewelry worth tens of thousands of dollars. In total, the Tweed Ring brought in an estimated $50 to $200 million in corrupt money. Boss Tweed’s avarice knew few boundaries.

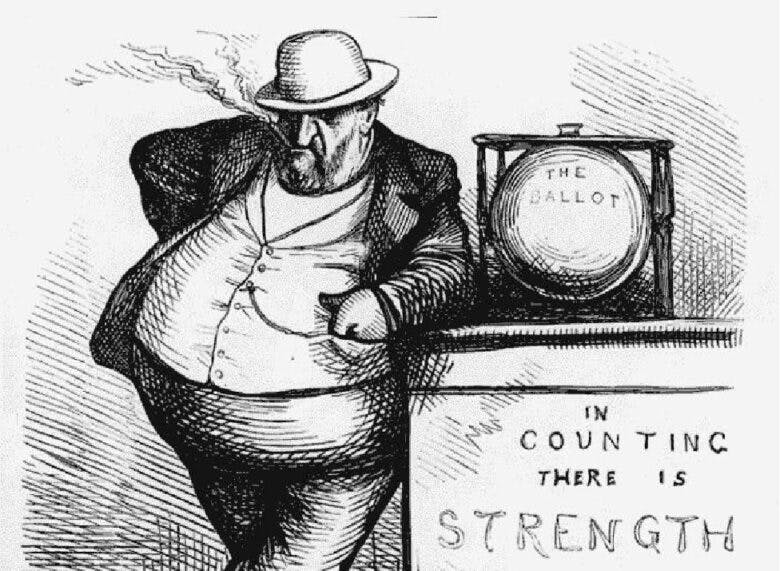

The corruption in New York City’s government went far beyond greed, however; it cheapened the rule of law and degraded a healthy civil society. Most people in local government received their jobs because of patronage rather than merit and talent. The Tweed Ring also manipulated elections in a variety of ways. It hired people to vote multiple times and had sheriffs and temporary deputies protect them while doing so. It stuffed ballot boxes with fake votes and bribed or arrested election inspectors who questioned its methods. As Tweed later said, The ballots made no result; the counters made the result. Sometimes the ring simply ignored the ballots and falsified election results. Tammany candidates often received more votes than there were eligible voters in a district. In addition, the ring used intimidation and street violence by hiring thugs or crooked cops to sway voters’ minds and received payoffs from criminal activities it allowed to flourish.

Tweed’s election manipulations were well known, with intimidation tactics keeping the ballot counts under the Tweed Ring’s control.

Although Boss Tweed and Tammany Hall engaged in corrupt politics, they undoubtedly helped the immigrants and poor of the city in many ways. Thousands of recent immigrants in New York were naturalized as American citizens and adult men had the right to vote. Because New York City, like other major urban areas, often lacked basic services, the Tweed Ring provided these for the price of a vote, or several votes. Tweed made sure the immigrants had jobs, found a place to live, had enough food, received medical care, and even had enough coal money to warm their apartments during the cold of winter. In addition, he contributed millions of dollars to the institutions that benefited and cared for the immigrants, such as their neighborhood churches and synagogues, Catholic schools, hospitals, orphanages, and charities. When dilapidated tenement buildings burned down, ring members followed the firetrucks to ensure that families had a place to stay and food to eat. Immigrants in New York were grateful for the much-needed services from the city and private charities. The Tweed Ring seemed to be creating a healthier society, and in overwhelming numbers, immigrants happily voted for the Democrats who ran the city.

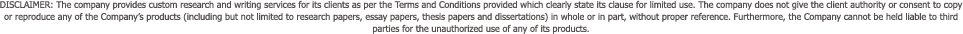

In the end, however, Boss Tweed’s greed was too great and his exploitation was too brazen. The New York Times exposed the rampant corruption of his ring and ran stories of the various frauds. Meanwhile, the periodical Harper’s Weekly ran the editorial cartoons of Thomas Nast, which lampooned the Tweed Ring for its illegal activities. Tweed was actually more concerned about the cartoons than about the investigative stories, because many of his constituents were illiterate but understood the message of the drawings. He offered bribes to the editor of the New York Times and to Nast to stop their public criticisms, but neither accepted.

Boss Tweed was arrested in October 1871 and indicted shortly thereafter. He was tried in 1873, and after a hung jury in the first trial, he was found guilty in a second trial of more than 200 crimes including forgery and larceny. He was sentenced to 12 years in prison.

One of Thomas Nast’s cartoons, called The Brains, argued that Boss Tweed won his elections thanks to money, not brains.

While he was in jail, Tweed was allowed to visit his family at home and take meals with them while a few guards waited at his doorstep. He seized an opportunity at one of these meals to escape in disguise across the Hudson to New Jersey, and then by boat to Florida, from there to Cuba, and finally to Spain. Because Spain’s government wanted the United States to end its support for Cuban rebels, it agreed to cooperate with U.S. authorities and apprehend Tweed. Aided by Nast’s cartoons in obtaining at least a close approximation of Tweed’s appearance, Spanish law enforcement recognized and arrested him and returned him to the United States. With his health broken and few remaining supporters, Tweed died in jail in 1878.

Watch this BRI Homework Help video on Boss Tweed for a look at his rise and fall and how Tammany Hall affect Gilded Age New York City.

Tammany Hall and the Tweed Ring are infamous models of Gilded Age urban corruption. Political machines corruptly ran several major cities throughout the United States, particularly in the Northeast and Midwest where millions of immigrants had settled. The machines may have provided essential services for immigrants, but their corruption destroyed good government and civil society by undermining the rule of law. By the early twentieth century, Progressive reformers had begun to target the bosses and political machines to reform city government in the United States.

Review Questions

1. Before becoming known as “Boss” Tweed, William Tweed served briefly as

- mayor of New York City

- governor of New York

- a member of Congress

- chair of the Board of Elections in New York

2. Tammany Hall’s treatment of immigrants who lived in New York City can be best described as

- leading the fight for nativism

- aiding immigrants with basic services

- encouraging immigrants to live in ethnic enclaves in the city

- providing job training for skilled laborers

3. Tammany Hall and Boss Tweed were most closely associated with which political party?

- Republicans

4. The Tweed Ring made most of its money from graft. One major example was

- charging businesses money to protect them from crime bosses

- unfairly taxing immigrants

- inflating the cost of major city projects such as the courthouse

- inflating the tolls charged to cross the Brooklyn Bridge

5. During the late nineteenth century, Thomas Nast was best known as

- a political opponent of William Tweed’s who served as governor of New York

- a critic of the Tweed Ring who published exposés about Boss Tweed

- an immigrant who was helped by Tweed and went on to a successful political career

- a critic of Tweed who sketched political cartoons exposing his corruption

6. An event that propelled William Tweed to a position of respect and more power in New York City was his

- first successful election as mayor of New York in 1864

- success in restoring order after the draft riots in 1863

- ability to authorize public works to benefit large numbers of immigrants

- success at providing comfortable housing for lower-income families

Free Response Questions

- Explain the positive and negative effect of the Tweed Ring on New York City.

- Evaluate the impact of the political machine on U.S. cities in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

AP Practice Questions

Thomas Nast depicts Boss Tweed in Harper’s Weekly (October 21, 1871).

1. Thomas Nast’s intent in drawing the political cartoon was to

- demonstrate the generosity of the political boss in the late nineteenth century

- show how corrupt Boss Tweed and Tammany Hall were in New York politics

- illustrate the greed of industrialists during the late nineteenth century

- show how honest politicians were

2. Which of the following emerged to seek to correct the problems created by the situation lampooned in the cartoon?

- The Populist movement

- The Progressive Era

- The Know Nothings

- The Second Great Awakening

3. Which group probably benefited most from the situation portrayed in the cartoon?

- Immigrants to the United States

- Members of labor unions

- African Americans

- Supporters of women’s suffrage

Primary Sources

Nast, Thomas. Thomas Nast Cartoons on Boss Tweed . Bill of Rights Institute. https://resources.billofrightsinstitute.org/heroes-and-villains/boss-tweed-avarice/

Suggested Resources

Ackerman, Kenneth D. Boss Tweed: The Rise and Fall of the Corrupt Pol Who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York . New York: Carroll and Graf, 2005.

Allswang, John M. Bosses, Machines, and Urban Votes . Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986.

Brands, H.W. American Colossus: The Triumph of Capitalism, 1865-1900 . New York: Doubleday, 2010.

Lynch, Dennis Tilden. Boss Tweed: The Story of a Grim Generation . New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, 2002.

Trachtenberg, Alan. The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in the Gilded Age . New York: Hill and Wang, 1982.

White, Richard. The Republic for Which It Stands: The United States during Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865-1896 . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Related Content

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness

In our resource history is presented through a series of narratives, primary sources, and point-counterpoint debates that invites students to participate in the ongoing conversation about the American experiment.

State and Local Government: US Political Machines Essay

Introduction, works cited.

In the late 19 th and early 20 th century, the larger cities in the United States were governed according to the principles of political machines politics. This unofficial system of a political organization is based on patronage. The latter implies the ability to do favors when holding public office.

Political machines often had bosses. The rapid urbanization brought changes that the boss and his/her machine should have coped with. Especially it is true concerning the problems that the official city government could not solve. Still, there is a view according to which the political machines were parallel governments. Their function was to meet the needs of the public and the public, in its turn, offered its allegiance and votes (Urban Bosses and Machine Politics). Sometimes the system of something for something was supplemented by threats of various kinds towards those who attempted to step outside it.

One of the functions of political machines was serving immigrants to the USA. For the immigrants, the machines were vehicles for political enfranchisement. The immigrants did not have a sense of civic duty and traded votes for power. Irish immigrants were the brightest example of how immigrants could benefit from the machines. Still, the party machines’ care of immigrants was not permanent, as machines were simply interested in maintaining a minimally winning amount of support. When this support was acquired there was no necessity any longer to recruit new members.

The constant corruption that was the basis for the political machines gave rise to many reform movements. American citizens were ready to tolerate some “reasonable” level of corruption, but when the level appeared to be too high, they balked it. Observing this pattern urban reformers had more power to succeed in seizing the power from the machines. They used to cost as a trigger for their reforms. But even successful reform movements did not always lead to efficient and less expensive government. During the Progressive Era, for instance, inflation led to costs that resulted in higher taxes (Urban Bosses and Machine Politics).

Still, reformers had other goals apart from the establishment of a less expensive government. The morale of the community was also a point of their concern. The reforms that they advocated were directed at prostitution, drinking, commercial issues, and leisure activities. The reform movement supported a set of social reforms such as factory safety laws, minimum-wage and maximum-hour laws, and protective legislation for women and children (Urban Bosses and Machine Politics).

In general, the changes that the political machines and the reformists advocated were rather similar. Though the machines cared less about the citizens’ morality than the reformists did, both systems of the political organization brought about improving the quality of urban life as it guaranteed them community support during elections. There was never a sharp line between the machines and the reformers that contributed to their long existence up to the twentieth century.

“Urban Bosses And Machine Politics.” Answers.com. 2008. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, October 24). State and Local Government: US Political Machines. https://ivypanda.com/essays/state-and-local-government-us-political-machines/

"State and Local Government: US Political Machines." IvyPanda , 24 Oct. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/state-and-local-government-us-political-machines/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'State and Local Government: US Political Machines'. 24 October.

IvyPanda . 2021. "State and Local Government: US Political Machines." October 24, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/state-and-local-government-us-political-machines/.

1. IvyPanda . "State and Local Government: US Political Machines." October 24, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/state-and-local-government-us-political-machines/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "State and Local Government: US Political Machines." October 24, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/state-and-local-government-us-political-machines/.

- The Struggle of the Minimum-Wage Workers and the Ideas of Worker Engagement

- The Veil and Muslim: How the Veil Became the Symbol of Muslim Civilization and What the Veil Meant to Islamic Reformists

- Teamwork and Motivation: Woowooo Inc.

- Reforms in the Gilded Age

- Civilization’s ‘Blooming’ and Liberty Relationship

- The Influence of Patronage on the History of Music

- Chinese Government’s Control over Salt and Iron Industries

- Urban Political Machines

- Douglas's Speech “What the Black Man Wants”

- The Art of Photography: Seizing the Moment Flying

- Government-Business Relations in China & Australia

- Hugo Chavez and Control Over Citgo Gas Corporation

- Comparative Governments. British Political System

- The Role Ethnic Affairs Played With Vietnamese Governments From 1975 to 2000

- US Government: Privacy and Presidential Power

Internet Explorer 11 is not supported

The rise, fall and mutation of political machines, they’ve been around a lot longer than you might think. they keep changing, but they still run on loyalty, as they always have..

- Archive When Does Politicians' Unethical Behavior Become a Crime? March 24, 2015 · Alan Ehrenhalt

Political Machines in the US Urban Politics

Introduction, birth of political machines, role of political machines in city modernization, role of immigrants, city governments, source of funding for local governments, city government budgeting, works cited.

Most of the US cities were run by political machines in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century (Tuckel & Maisel 99). A political machine is an organization controlled by a powerful boss or group of people who enjoy the support of a section of the population (Tuckel & Maisel 100-101). The support base is large enough to deliver victory during elections. Political machines exist for mutual benefits to the members. In this case, politicians get votes while voters are rewarded with jobs and money. Business people contribute campaign funds and they are rewarded with government contracts (Tuckel & Maisel 101).

In the US, political machines had membership at three levels. There was a party boss or group of people at the top who controlled all members and activities in the organization (Tuckel & Maisel 103). There were electoral district captains operating under the command of the boss. Electoral district captains were responsible for mobilising, organising and soliciting support from a section of the electorate. At the bottom there were voters who made their contribution by voting for the machine’s selected candidates in return for favours. Most political scientists have rated political machines as most corrupt and unfortunate form of leadership (Tuckel & Maisel 104)). However, a closer look at the activities of political machines reveals that they played a crucial role in infrastructural modernization and political reforms in US cities.

Most of the US cities experienced high population growth rates in the19 th century due to arrival of immigrants from Europe and other parts of the world. As Tuckel and Maisel notes, this population growth led to over-stretching of services provided by city authorities (105). As a result, city governments became infamous, forcing politicians to devise other methods of gaining and retaining political power. In this regard, politicians resorted to political machines (Tuckel & Maisel 107-108).

Political machines were introduced at the time when most city governments were experiencing inefficiencies and lack of faith among the constituents. For example, one of the most talked about political machine was the Tammany Hall of New York City (Tuckel & Maisel 87). Tammany Hall was a Democratic Party political machine that controlled political activities in New York from late 19 th to early 20 th century. As Tuckel & Maisel observes, the machine experienced most memorable times under the command of William Tweed who was famously known as “Boss” (88). Under the command of Tweed, this machine won the mayor’s post and majority seats in the legislature (Tuckel & Maisel 89). Tweed was appointed together with other members of the machine to occupy important positions in the city government. He engineered the government to embark on streamlining service delivery.

Tweed manipulated the legislature to formulate a new charter that brought the city budget under control of the city government (Tuckel & Maisel 91). He was able to leverage the city with municipal bonds and start the crucial process of modernization. This brought some efficiency even though the city population was still growing. Tuckel & Maisel (92) notes that other cities that had political machines such as Boston, Chicago and Cleveland had the same experience.

Although political machines were strong and well organised, they were also highly corrupt. Members of the machine were well rewarded while non-members were intimidated. This led to formation of reform movements to fight the injustices perpetrated against a section of the population (Tuckel & Maisel 93). As a result, more efficiency was realized, leading to further modernization of infrastructure.

Political machines were majorly used by immigrants to access political power. Majority of the immigrants were Irish people who had relocated to pursue jobs (Tuckel & Maisel 93). The population of Irish immigrants in the US had increased to a level where they could challenge for political power. As new immigrants arrived, they were recruited into the machine and rewarded with gifts. This further angered the nativist Protestants who advocated for Civil Service rather than patronage (Tuckel & Maisel 99). The federal government under Theodore Roosevelt also mobilized citizens to vote against political machines. This led to elimination of most machines by the year 1960.

In the US, state governments have significant influence on the running of city governments. According to Hannarong & Akoto (40), the powers that city governments enjoy are donated by state governments. In this case, state governments can change the operations of city governments provided that such changes are in agreement with the state laws. However, organization of city governments may differ from one state to another (Hannarong & Akoto 41-42). In this regard, different states may have different laws governing local governments. It is also worth mentioning that some states have given more powers to city governments than others. Sometimes states make laws that frustrate the operations of local governments.

Most of the funds used by US city governments come from direct taxation (Hannarong & Akoto 43). These include property tax, personal income tax, general sales tax, business income tax, and tax on real estates. In most states, taxation laws are made by state governments. City governments also get funding from state and federal governments (Hannarong & Akoto 44). Contributions from state and federal governments make the second largest source of funding for most of the city governments. Direct investment also contributes to the funding of city governments (Hannarong & Akoto 45).

City government budgeting is done by the mayor (Tannenwald 467). After preparing preliminary estimates, the budget is taken to the city council for approval. Before accepting or rejecting the proposed budget, it is taken for public hearing by the relevant council committee to have the opinion of tax payers and other stakeholders (Tannenwald 467). Budget making is not always a smooth process.

During public hearing, stakeholders may make a lot of demands; some of which may be unrealistic. As Tannenwald notes, common demands include cutting taxes and delivery of quality services (468). At this point, budget makers also get the opportunity to explain to stakeholders some of the constraints that may be guiding their budget decisions. After public hearing, the council makes a decision on whether to accept or reject the budget. This is normally done through voting.

Sometimes approved budgets may have to be adjusted. This may happen due to changes done on taxation laws by the state (Tannenwald 469). Under such circumstances, the city government can look for alternative funding or adjust the budget. Alternative revenues can be raised through borrowing which has to be done in accordance with the state rules. This dilemma can be addressed by giving city councils more control on taxation laws.

Political machines were invented by politicians as a survival mechanism at the time when their performance was in question. The machines were strong, highly organised but very corrupt. They were mostly used to obtain political power by Irish immigrants. The corrupt ways of political machines attracted reforms that led to their elimination. On the other hand, US cities are run differently in different states. Most of them still operate under strict control by the mother states. Sometimes this causes confusion, especially in the budget making process. Since city councils are in close proximity with the working of city governments, they should be in charge of the laws that govern local government taxation.

Hannarong, Shamsub & Akoto Joseph. State and Local Fiscal Structure and Fiscal Stress, Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management , 16.1(2004): 40-61. Print.

Tannenwald, Robert. Are State and Local Revenue Systems becoming Obsolete?, National Tax Journal , 3(2002):467-489. Print

Tuckel, P. & Maisel, R. Nativity Status and Voter Turnout in Early Twentieth-Century Urban United States. Journal of Historical Methods , 41.2(2008): 87–108. Print.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2020, May 27). Political Machines in the US Urban Politics. https://studycorgi.com/political-machines-in-the-us-urban-politics/

"Political Machines in the US Urban Politics." StudyCorgi , 27 May 2020, studycorgi.com/political-machines-in-the-us-urban-politics/.

StudyCorgi . (2020) 'Political Machines in the US Urban Politics'. 27 May.

1. StudyCorgi . "Political Machines in the US Urban Politics." May 27, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/political-machines-in-the-us-urban-politics/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Political Machines in the US Urban Politics." May 27, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/political-machines-in-the-us-urban-politics/.

StudyCorgi . 2020. "Political Machines in the US Urban Politics." May 27, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/political-machines-in-the-us-urban-politics/.

This paper, “Political Machines in the US Urban Politics”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: November 3, 2020 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

A Political Machine for the 21st Century

The trump organization as platform capitalism.

This essay was originally published on August 22 2019.

Today, the Trump Organization lies at the epicenter of political power in the American state. How should we make sense of the family business and its relationship to politics? Ethics watchdogs and journalists speak of “ conflicts of interest ” when the president governs from Mar-a-Lago or promotes his golf properties and brands. Most conspicuously, the president flaunts the Emoluments Clause of the Constitution by accepting payments from domestic states and foreign governments. Critics denounce the potential for quid pro quo corruption by big spenders looking to court favor at Trump venues or by extending the president’s family lucrative business opportunities. But even anxieties about public corruption miss the big picture.

Donald Trump is building his company into a “platform.” By this, I mean the president has positioned the Trump Organization as the indispensable medium through which the party-government linkage is valorized. Roughly $10 billion circulated throughout the political system in 2016, a conservative estimate that adds up the publicly reported cost of the election cycle with that of lobbying . Although small in comparison to other sectors, the political-industrial complex is increasingly financialized and growing rapidly. The rents extracted by political professionals are actually minor relative to the policy windfall. Companies receive a taxpayer bailout. A new pharmaceutical drug is brought to market. Or, if cryptocurrencies are allowed to flourish. Out of this swamp has grown something novel: a party business that governs.

Platform capitalism is a term that describes our new age of digital monopolies . Like Facebook, Google, or Amazon, the Trump Organization aspires to operate as a ‘platform’, exerting monopolistic control over an industry or sector. (At least, insofar as the political market is organized by the Republican party.) By gaining a commanding position, platforms disrupt business as usual by flexing market-making powers with the potential to extract super-profits. We have become accustomed to hear startups pitched as “Uber, but for x.” (One satirical Twitter bot generates ideas “ Like Uber, but for…noodle ”). What matters to platforms is not any particular content or commodity — on Facebook, users post whatever they desire. Rather, the gambit lies in control over the infrastructure through which various types of content flow. You buy or sell books on Amazon, but also diapers, clothing — anything. You watch TV there. The Seattle-based company recently moved into shipping packages, cloud computing, and banking services. Platforms are not the car (initially, at least) but the road upon which you drive.

By bringing platform capitalism into the party system, Trump is experimenting with a new mode of political organization. Presidents historically govern by centralizing party activity through the Republican National Committee (RNC) or Democratic National Committee (DNC). More recently, SuperPACs run by political advisors have played an important role as the president’s official voice (think of Priorities USA or Obama For America). Donald Trump’s approach differs. A wide constellation of political actors — from officeholders, campaign committees, affinity groups, donors, and companies, to trade associations and foreign governments — are now marshaling their activity through the president’s family business. What began as a marketing ploy has evolved into a platform upon which partisans and favor-seekers must compete.

From Party Machine To Platform

“ We don’t want nobody nobody sent ,” one machine politician famously quipped. The axiom exemplifies how coordination is one of the few imperatives in democracy, and that influence is predicated upon closing ranks. Political parties first emerged as a way to promote careers, work in concert with others, and place a common agenda before voters. With the rise of mass politics in the nineteenth century, however, a question arose. If the party coordinates the government, who or what coordinates the party? Bosses and the political machines they built took on the role of coordinating the coordinators. Just as parties were an extra-constitutional form of organization, machines developed unexpectedly as shadow institutions that were vital but one-step removed.

The personalities and institutional expressions of political machines varied widely. Some twentieth century cases were built upon the charisma of populist leaders like James Curley of Boston or Huey Long of Louisiana. Others, like Chicago’s Daley Machine , tracked closer to bureaucratic authoritarianism . What all the machines held in common was a monopoly right to speak and act on behalf of the party, secured by control over the means of election and public administration. Public and private sources of patronage — from the parks department, for example, or a shady land deal — were leveraged into nominations and offices. If you wanted a career in politics, or a policy fix, you simply had to work through the boss or his adjuncts. This is what “practical politics” meant in the industrial era of mass politics.

Today, party competition and patronage flows through Trump’s private company rather than a classic-style machine. The new party monopoly is not about absolute control over nominations or parochial territory. Instead, what matters is shaping where and how investment moves through the political system: the way in which domestic or global capital materializes within national political institutions; how it connects to the political-industrial complex, from election campaigns to lobby shops; where Republicans meet and spend party money; and influence over the means by which personal relationships are formed fundamental to career ambitions. This last point on political socialization, by the way, is elemental for a party trending toward patrimonial-style rule .

As a capital-intensive platform, the Trump Organization has brought order to the chaotic internal Republican party market. The Supreme Court’s decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010) gave rise to innumerable advocacy groups that decentered the traditional party apparatus, from the Tea Party and Koch network, to fly-by night scamPACs, and billionaire donors going it alone. That ‘warring states’ period of internal conflict is over. What now constitutes the boundary of legitimate party competition is policed by the extent to which disparate groups are willing and able to work through the president’s myriad businesses, by courting official favor. Those who patronize the Trump Organization expect to be first in line.

Luxury Organization

If the classic machines coordinated a mix of public and private resources within the shadow of the party state, how does this look today? Party committees, SuperPACs, and ideological groups are some of the biggest spenders at Trump properties, especially the Trump International Hotel, located just down the street from the White House. Clients follow public signaling from the president himself, his own campaign spending , and patronage from high-ranking administration officials. Frequent travel to Mar-a-Lago has pulled the orbit of corporate lobbying into his private club. Before the presidential election, regulars at the Palm Beach resort largely consisted of the nouveau riche and celebrities. Since 2016, membership fees have doubled and Mar-a-Lago has transformed into a luxury political clubhouse filled with influencers and apparatchiks. Trump’s daughter Ivanka, formerly a top executive at the Trump Organization, works in the White House as one of her father’s main advisors. Meanwhile, Don Jr. and Eric continue to expand the company at home and abroad . Three years into the Trump Administration, doing business with the First Family is doing business with the United States.

In some ways, times have changed since the old machines. Daniel Schlozman and Sam Rosenfeld argue that parties today are “ hollow ,” in the sense that they have few grassroots mechanisms characteristic of mass participation. The centrality of petty officeholding is also different. Back in the 1880s, the reformer William Ivins referred to public offices distributed throughout the spoils system as the “capital” of the machine. Allocating coveted jobs allowed party machines to embed themselves deeply in social life at the neighborhood or ward level. Patronage workers then returned a portion of salary (or time) back into a common pot that served as the machine’s working capital. Monetary tithes were called assessments . Technically, the cash was a voluntary donation of partisans to their party. But lack of payment meant loss of party standing, and therefore, your job. It took reformers nearly a century to ban assessments at the federal level.

Today, political assessments have reemerged without patronage armies. The parties operate more like brands that market a collective image and cue partisan voters with messaging on TV spots or social media. Thus, in order to centralize management over producer services in the political sector, the Trump Organization has little need to employ a modern army of ward heelers. Butlers at Mar-a-Lago are not directly involved in the election canvass in the way clerks or messengers at the nation’s ports were once upon a time. Yet, it would be a mistake to presume there lacks a material basis to Trump’s mode of political organization similar to the patronage mills of yore.

The platform’s capital is whatever inputs into the Trump Organization are necessary to gain the ear and favor of the president. T-Mobile dropped $195,000 at the Trump International Hotel in Washington D.C. while regulatory approvals were pending for its merger with AT&T . Saudi lobbyists spent $270,000 there, right after the election time. And so on . The public does not have a full picture of private transactions. Still, transparency databases compiled by the Center For Responsive Politics , Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington , and other investigative reports , suggest that payments are systematic . What is this money but a political assessment? Clients must again tithe a portion of their earnings back to the party leader who, in this instance, is president. Recent financial disclosures show the Trump International Hotel alone earned more than $40 million in revenue last year. The hotel’s political clientele makes it by far the most promising new asset in the Trump Organization’s 500-large portfolio of limited liability corporations.

Clubhouse Rules

Capital accumulation as a mode of governance is “ very legal & very cool ,” according to President Trump. Here, another parallel is apt with the business model of Silicon Valley platforms. Trump Organization profits are only possible via the political equivalent of regulatory evasion. Airbnb or Uber set up shop in a city first, or Facebook rolls out a new service with privacy implications, and then dare regulators to react. Trump has brazenly violated long standing campaign finance law and conflict of interest rules in similar fashion by using his company to electioneer , by making political contributions through his charitable foundation , and by refusing to divest from personal business once in office. Federal oversight and enforcement, weakened by court rulings and party polarization , is non-functional. The strategy is risky. So far it has been more than vindicated . Judge Paul Niemeyer and the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals recently dismissed one of the many emoluments suits, reasoning that it would be inconceivable and impractical to separate the president from a family business that carries his name. Any cases that do reach the Supreme Court are likely to ratify political innovations that entrepreneurs have already brought into existence. Why?

Let us not forget that political finance is but recently deregulated. The post-Watergate consensus about limiting the influence of money in politics only unraveled in the wake of Citizens United v. FEC (2010). Along with a permissive approach to unlimited funds and corporate electioneering, the landmark case established that “ingratiation” is not tantamount to public corruption. McCutcheon v. FEC (2014), McDonnell v. U.S. (2015) and the 2017 corruption mistrial of Senator Bob Menendez (D-NJ) reflect the federal court’s skepticism that favors, gifts, payments or special privileges given to public officials result in quid pro quo behavior . The First Amendment right of individuals and corporations to deploy private wealth, as they wish, in politics is given wide berth by the Roberts Court.

In this way, Trump is the first Citizens United president. Mick Mulvaney explained to a conference of bankers that he never held a meeting with lobbyists during his tenure in Congress, until they donated to one of his political committees. The fee-for-access method is clarifying. Mulvaney is now Trump’s chief of staff, and it is reasonable to ask whether the approach is generalized in the White House. For the Roberts Court, property qualifications like this are desirable barriers that promote the health of national political institutions. The logic harkens back to a long history of property and taxpayer qualifications that once restricted the electorate by race and class . Few people have the money, let alone the time or skills, to contest roadblocks to political participation. In the last cycle when an incumbent president was up for re-election, more than a quarter of reported political donations came from the tiniest sliver of the population — a mere one percent of the one percent. The court’s approach assures the most propertied interests in society will be first in line. If the line gets too long, the gates of Mar-a-Lago, a private club where the Trump has conducted one third of his presidency , can always be shut.

Even if you have money to burn there is no ‘sure thing.’ In business, as in politics, you need to know where and how to invest wisely. That vehicle is the Trump Organization. This does not imply that anyone who drops money at Trump International Hotel or rents space at Trump Tower will get exactly what they want, or when they want it, as if selecting candy from a vending machine. Instead, the president’s company looks to structure the political marketplace. Clients pay to walk through Mar-a-Lago’s veranda or to be on the terrace at the right moment, and catch the attention of someone who matters. And what is the hospitality industry — of which the Trump International Hotel and Mar-a-Lago are exemplar — if not the business of ingratiation ? By granting expansive rights to private capital, the Roberts Court invited a risk-taking entrepreneur to run their family business from the White House. After all, Donald Trump is the first president who is also a company. Corporations are people , too.

Jeffrey D. Broxmeyer is an Assistant professor of Political Science and Public Administration at The University of Toledo. His first book, Electoral Capitalism: The Party System In New York’s Gilded Age, is forthcoming from the University of Pennsylvania Press. @JeffBroxmeyer

Jeffrey D. Broxmeyer

Assistant professor of Political Science and Public Administration at The University of Toledo

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Latest + Beyond the Issues

Public Seminar is a journal of ideas, politics, and culture published by the Public Seminar Publishing Initiative at The New School. We are a non-profit organization, wholly supported by The New School, and by the generosity of our sponsors and readers.

Connect With Us

Module 2: Industrialization and Urbanization (1870-1900)

Historical arguments and machine politics, learning objectives.

- Evaluate the thesis statements and supporting evidence used to make claims in historical arguments

- Compare historical arguments about the pros and cons of political machines

The Necessity of Machine Politics

Life in a nineteenth-century urban center in America was tough, to put it mildly. Working-class people toiled for long hours in poor conditions and had virtually no one at the higher levels of society tasked with looking after their interests. Workplace health and safety laws did not exist, nor did zoning regulations for the shoddy tenement buildings where they crowded entire families into a single room. Sanitation and public health were largely an afterthought with no readily available health care, no regulations on food, and no such thing as vaccinations.

The rapid rate of urban growth meant that city officials struggled to keep up with infrastructure improvements such as gutters and sidewalks, improvements which were more desperately needed in areas without running water. Unfortunately, residents of working-class neighborhoods were often sidelined by officials in favor of business owners or wealthy industrialists who could donate to their campaign funds. The necessity of garnering City Hall’s attention was not lost on the urban working-class, however, and they eventually landed on a system that sometimes worked out in their favor and sometimes did not: machine politics.

The leaders of these political “Machines,” which were actually political party organizations, were usually wealthy leaders in the community who were appointed to various city boards or commissions. This gave them access to power. Their leaders were known as bosses, and a boss would offer favors or incentives to his constituents in exchange for their votes during the next election cycle. Sometimes, he might direct those votes toward a person higher-up on the political ladder who had called in a favor.

Many contemporary writers and modern historians have argued that machine bosses were an essential part of urban life and that they provided a type of service that the working class would not have been able to access any other way. They argue that the political machine was the only way that many immigrants could assimilate into American society and become leaders, or that this corruption actually helped poor Americans, whereas all other corruption simply boosted those who were already on top. On the other hand, some argue that machine bosses did not actually care about their working-class constituents or the quality of life that they lacked, but that their only aim was more money and more power and they simply used this desperate group to help them achieve these goals.

Figure 1 . The Tammany Tiger Loose—”What are you going to do about it?”, published in Harper’s Weekly in November 1871, just before election day. “Boss” Tweed is depicted in the audience as the Emperor.

Often, the political machine was able to implement public projects faster than if they had to navigate bureaucratic red tape, but the cost was that the boss would line his own pockets with some of the funding. It was a trade-off that most working-class Americans were willing to accept if it made their day-to-day lives easier, since the machinations of the political elite were not something that they concerned themselves with. In fact, many of New York City’s most famous features, such as Central Park and the Brooklyn Bridge, were products of machine politics. So what role did bosses play in the life of the urban working class? Were they heroes or villains? First, we’ll learn about historical argumentation and we’ll read a historian’s argument about political machines.

Understanding Arguments

In its most basic form, an argument is a statement that is supported by one or more facts. For example, I could make the argument that “Michigan is a better place to live than California.” I could support this argument with facts like:

- “Michigan has the lowest risk of natural disasters of any U.S. state, while California has one of the highest.”

- “Michigan’s cost of living is far lower than California’s.”

- “Both Michigan and California have beaches.”

A more detailed argument might include information about weather, school quality, population density, the job market, political climate, or diversity as it pertains to each state. The conclusion, that Michigan is a better place to live than California, would have to be supported by those facts. For every argument, however, there is a counter-argument. The counter-argument in this scenario would be “California is a better place to live than Michigan,” and could be supported by facts like:

- “California has better weather year-round,”

- “California has better schools.”

- “California has more public beaches than Michigan does.”

The tricky thing about this scenario above is that each person will find a different argument more convincing based simply on their personal preferences or experiences. Someone who has actually lived in both states might have a different perspective than someone who has only lived in California, or a person who loves beaches might come to a different conclusion than someone who doesn’t care for them.

Dissecting Historical Arguments

It is similar with historical arguments—because we are often seeing the arguments and the facts through the lenses of historical actors, through our own understanding of the time period (which could be incomplete), or through our own personal or cultural lens, we may come to different conclusions than someone else. When reading and assessing historical arguments, it is also important to remember that, like in the scenario above, there is sometimes no correct answer. The nuances of historical interpretation are often such that no single conclusion is possible and we will likely never have a definite answer.

Argument #1: The Value of Machine Politics

Now, it is your turn to analyze and identify arguments. First, we are going to look at this argument made by historian Stephanie Hinnershitz of Cleveland State University (note that she authored the response, but it does not necessarily reflect her views). She responded to the following question:

- Were urban bosses corrupt politicians who manipulated the political system for their own control and gain, or were they providing essential services for immigrants and enabling the growth of cities despite corrupt means?

“So, you see, these fool critics don’t know what they’re talking about when they criticize Tammany Hall, the most perfect political machine on earth,” explained George Washington Plunkitt, the son of Irish immigrants who grew up in squalor in New York City’s Five Points neighborhood and later became a prominent figure in Tammany Hall, the most well-known urban political circle in American history. William “Boss” Tweed was the powerful leader of Tammany, the machine that eventually became synonymous with the Democratic Party of New York City. Bosses like Tweed worked their way up to the top of well-run political circles by securing political positions through patronage and the spoils system. By delivering on promises of socioeconomic and political improvement in exchange for votes, bosses built urban empires with supporters in various city (and, at times, state-level) positions working continuously to ensure a voter base. In return, voters afforded the bosses power to secure their own political and, in many cases, financial gains. Bosses typically had no qualms with engaging in questionable and often downright corrupt money-for-politics schemes, securing political positions to guarantee financial benefits to their supporters in the form of contracts for public building projects or favorable city tax and regulation codes. Plunkitt responded to the charge of corruption from many of the growing army of muckraking journalists; however, it is the characterization of the bosses as criminals who preyed on the many immigrants in cities in return for votes—“buying” political support from those who were most economically, politically, and socially vulnerable and in the process tainting America’s democratic process—that encourages historians to describe them as vultures of the Gilded Age. Urban bosses bribed and exploited immigrants for political gain and tossed them to the side when they were no longer needed. But this simplistic view of men like Boss Tweed ignores the social services that urban bosses provided to the downtrodden in the complex and often labyrinthine environment of America’s Gilded Age cities.

Urban bosses assisted immigrants in ways beyond simply providing food, jobs, and shelter in exchange for votes. Assistance for immigrants was more rooted in providing ways for immigrants to function in the cities rather than just providing them with material goods. Gilded Age cities were dangerous, unscrupulous, and exclusionary spaces for newly arriving immigrants. Neighborhoods such as Five Points were often cut off from basic services and resources provided to the wealthier inhabitants of the more upper- and middle-class sections of New York, leaving immigrants stranded and isolated. Long before the bosses gained power, politics in cities was ironclad and run and operated by elites, a pattern that became more engrained as industrial capitalists and millionaires gained influence in the political system by the late nineteenth century. Furthermore, with little legal assistance and lacking a clear path to naturalization, many immigrants remained voiceless and powerless to change the environment they lived in and the dangers they faced daily.

Enter the urban bosses who allowed immigrants to gain a foothold in American society through increased political participation (albeit a monetary and perverted form of political participation). Tweed’s influential political “ring” included various judges in New York’s municipal courts, and before the election of 1868, Tweed used these connections to turn the courts into “naturalization mills” to produce approximately 1,000 new American citizens per day—providing him with a new voter base. Many historians simply focus on Tweed’s practice of “buying” votes or having immigrants commit voter fraud to explain his rise to power, but more commonly, he assisted immigrants with the naturalization process and ensured the victory of his machine in a way that also provided immigrants with long-term benefits. Once naturalized, immigrants were now on a path to obtain jobs in city government as the Irish did in droves during the late nineteenth century. In return, these immigrants-turned-citizens were required to drum up continuous support for the political machine. Nonetheless, bosses provided immigrants with an opportunity for socioeconomic advancement, a pattern that created, as Plunkitt noted, political machines in various cities across the United States that lasted long into the twentieth century.

Finding the Thesis

One of the first steps to dissecting historical arguments is to locate the thesis statement. This is a single statement, sometimes only a single sentence, that clearly states the core argument being made. It does not necessarily present the supporting facts (since that is the next step in making an argument), but succinctly lets the reader know what is being argued.

When analyzing historical arguments, locating the thesis statement can be a bit trickier because it might be “hidden” next to supporting facts or it might be far more complex than simply “this is what happened.” The thesis statement usually appears within the introduction of the essay or article and then reappears in the conclusion.

Read through the excerpt from Argument #1 again and see if you can find the thesis statement. Remember, it could be one sentence or two, and it might be bookended by supporting facts or even counter-arguments. Make sure that you are looking for the introductory thesis statement and not skipping ahead to the conclusion! This practice will help when you write your own historical arguments.

Find the Thesis

Write 1-2 of your ideas about what the thesis statement could be here:

Summarizing & Supporting Arguments

While it is always important to know how to locate a thesis statement in a historical argument, it is equally important to know how to describe the argument in your own words and to identify the supporting evidence used by the author. When you summarize the argument, you can combine the thesis statement with some of the supporting evidence to explain what the author is arguing and why that is their position. In order to help you practice your argument summarizing skills, use a narrative form and write your summary in your own words (rather than direct quotes from the text).

Going back to our example argument (Michigan vs. California), we can think of it as a mathematical formula: Thesis Statement + Supporting Facts = Summary of Argument

- Thesis: Michigan is a better place to live than California +

- Fact: Michigan has a lower cost of living +

- Fact: Michigan has fewer natural disasters +

- Summary: Due to the lower cost of living and comparatively infrequent natural disasters, Michigan is a far more attractive state for American families to live than California.

Note: This is a very simplistic argument and summary. Once you start doing this with more complex historical arguments, you can include more supporting facts in your summary and the thesis statement will probably be longer.

Complete the activity below using the thesis statement and supporting facts from Argument #1 about machine bosses.

Supporting and Summarizing Arguments

Great work so far! In the next section, you will read an opposing article and work on identifying and summarizing counterarguments.

- Historical Arguments and Machine Politics. Authored by : Lillian Wills for Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Preview Course, Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness. Provided by : OpenStax. Located at : https://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:8Bxo13ss@5/9-17-%F0%9F%92%AC-Were-Urban-Bosses-Essential-Service-Providers-or-Corrupt-Politicians . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]

- Tammany Hall Tiger. Authored by : Thomas Nast. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Nast#/media/File:Nast-Tammany.jpg . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

June 7, 2023

How AI Could Take Over Elections—And Undermine Democracy

An AI-driven political campaign could be all things to all people

By Archon Fung , Lawrence Lessig & The Conversation US

Douglas Rissing/Getty Images

The following essay is reprinted with permission from The Conversation , an online publication covering the latest research. It has been modified by the writers for Scientific American and may be different from the original .

Could organizations use artificial intelligence language models such as ChatGPT to induce voters to behave in specific ways?

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Sen. Josh Hawley asked OpenAI CEO Sam Altman this question in a May 16, 2023, U.S. Senate hearing on artificial intelligence. Altman replied that he was indeed concerned that some people might use language models to manipulate, persuade and engage in one-on-one interactions with voters.

Here’s the scenario Altman might have envisioned/had in mind: Imagine that soon, political technologists develop a machine called Clogger – a political campaign in a black box. Clogger relentlessly pursues just one objective: to maximize the chances that its candidate – the campaign that buys the services of Clogger Inc. – prevails in an election.

While platforms like Facebook, Twitter and YouTube use forms of AI to get users to spend more time on their sites, Clogger’s AI would have a different objective: to change people’s voting behavior.

How Clogger would work

As a political scientist and a legal scholar who study the intersection of technology and democracy, we believe that something like Clogger could use automation to dramatically increase the scale and potentially the effectiveness of behavior manipulation and microtargeting techniques that political campaigns have used since the early 2000s. Just as advertisers use your browsing and social media history to individually target commercial and political ads now, Clogger would pay attention to you – and hundreds of millions of other voters – individually.

It would offer three advances over the current state-of-the-art algorithmic behavior manipulation. First, its language model would generate messages — texts, social media and email, perhaps including images and videos — tailored to you personally. Whereas advertisers strategically place a relatively small number of ads, language models such as ChatGPT can generate countless unique messages for you personally – and millions for others – over the course of a campaign.

Second, Clogger would use a technique called reinforcement learning to generate messages that become increasingly more likely to change your vote. Reinforcement learning is a machine-learning, trial-and-error approach in which the computer takes actions and gets feedback about which work better in order to learn how to accomplish an objective. Machines that can play Go, Chess and many video games better than any human have used reinforcement learning. And last, over the course of a campaign, Clogger’s messages could evolve to take into account your responses to prior dispatches and what it has learned about changing others’ minds. Clogger would carry on dynamic “conversations” with you – and millions of other people – over time. Clogger’s messages would be similar to ads that follow you across different websites and social media.

The nature of AI

Three more features – or bugs – are worth noting.

First, the messages that Clogger sends may or may not be political. The machine’s only goal is to maximize vote share, and it would likely devise strategies for achieving this goal that no human campaigner would have considered.

One possibility is sending likely opponent voters information about nonpolitical passions that they have in sports or entertainment to bury the political messaging they receive. Another possibility is sending off-putting messages – for example incontinence advertisements – timed to coincide with opponents’ messaging. And another is manipulating voters’ social media groups to give the sense that their family, neighbors, and friends support its candidate.

Second, Clogger has no regard for truth. Indeed, it has no way of knowing what is true or false. Language model “hallucinations” are not a problem for this machine because its objective is to change your vote, not to provide accurate information.

Finally, because it is a black box type of artificial intelligence , people would have no way to know what strategies it uses.

If the Republican presidential campaign were to deploy Clogger in 2024, the Democratic campaign would likely be compelled to respond in kind, perhaps with a similar machine. Call it Dogger. If the campaign managers thought that these machines were effective, the presidential contest might well come down to Clogger vs. Dogger, and the winner would be the client of the more effective machine.

The content that won the day would have come from an AI focused solely on victory, with no political ideas of its own, rather than from candidates or parties. In this very important sense, a machine would have won the election rather than a person. The election would no longer be democratic, even though all of the ordinary activities of democracy – the speeches, the ads, the messages, the voting and the counting of votes – will have occurred.

The AI-elected president could then go one of two ways. He or she could use the mantle of election to pursue Republican or Democratic party policies. But because the party ideas may have had little to do with why people voted the way that they did – Clogger and Dogger don’t care about policy views – the president’s actions would not necessarily reflect the will of the voters. Voters would have been manipulated by the AI rather than freely choosing their political leaders and policies.

Another path is for the president to pursue the messages, behaviors and policies that the machine predicts will maximize the chances of reelection. On this path, the president would have no particular platform or agenda beyond maintaining power. The president’s actions, guided by Clogger, would be those most likely to manipulate voters rather than serve their genuine interests or even the president’s own ideology.

Avoiding Clogocracy

It would be possible to avoid AI election manipulation if candidates, campaigns and consultants all forswore the use of such political AI. We believe that is unlikely. If politically effective black boxes were developed, competitive pressures would make their use almost irresistible. Indeed, political consultants might well see using these tools as required by their professional responsibility to help their candidates win. And once one candidate uses such an effective tool, the opponents could hardly be expected to resist by disarming unilaterally.

Enhanced privacy protection would help . Clogger would depend on access to vast amounts of personal data in order to target individuals, craft messages tailored to persuade or manipulate them, and track and retarget them over the course of a campaign. Every bit of that information that companies or policymakers deny the machine would make it less effective.

Another solution lies with elections commissions. They could try to ban or severely regulate these machines. There’s a fierce debate about whether such “replicant” speech , even if it’s political in nature, can be regulated. The U.S.’s extreme free speech tradition leads many leading academics to say it cannot .

But there is no reason to automatically extend the First Amendment’s protection to the product of these machines. The nation might well choose to give machines rights, but that should be a decision grounded in the challenges of today , not the misplaced assumption that James Madison’s views in 1789 were intended to apply to AI.

European Union regulators are moving in this direction. Policymakers revised the European Parliament’s draft of its Artificial Intelligence Act to designate “AI systems to influence voters in campaigns” as “high risk” and subject to regulatory scrutiny.

One constitutionally safer, if smaller, step, already adopted in part by European internet regulators and in California , is to prohibit bots from passing themselves off as people. For example, regulation might require that campaign messages come with disclaimers when the content they contain is generated by machines rather than humans.

This would be like the advertising disclaimer requirements – “Paid for by the Sam Jones for Congress Committee” – but modified to reflect its AI origin: “This AI-generated ad was paid for by the Sam Jones for Congress Committee.” A stronger version could require: “This AI-generated message is being sent to you by the Sam Jones for Congress Committee because Clogger has predicted that doing so will increase your chances of voting for Sam Jones by 0.0002%.” At the very least, we believe voters deserve to know when it is a bot speaking to them, and they should know why, as well.

The possibility of a system like Clogger shows that the path toward human collective disempowerment may not require some superhuman artificial general intelligence . It might just require overeager campaigners and consultants who have powerful new tools that can effectively push millions of people’s many buttons.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

This article was originally published on The Conversation . Read the original article .

Dissertation

Research Paper

- Testimonials

Research Papers

Dissertations

Term Papers

Essay Paper on Political Machines

Being an unofficial political system, political machine founds its activities on the basis of patronage, using the structure of representative democracy. Their important integrating role in American society is clearly viewed through country’s history and successful implementation of its main principles.

The main difference between trade unions and political machines consisted in the fact that the electors of this system tended to be unskilled workers, unionized skilled workers and middle-class elements united. The sites of organization were in the neighbourhoods where workers lived at that time, and their mayor demands involved the following: allocation of public jobs among the city’s various ethnic groups and of public facilities among its various neighbourhoods. Public machine in its turn was a solid secure of benefits for its followers that united them for the fight in the electoral arena.

On the national level the Republicans and Democrats were strong parties and rather strong leaders, but on the local level in order to attract more and more votes, they constructed public machines that efficiently provided them with what they needed. The machine politicians who moved to the fore of American urban politics late in the century established their political hegemony by arranging an accommodation among the major political forces in the city. The precise terms varied from city to city, as did the process through which the locally dominant machine became institutionalized. It is not feasible to describe these variations here; the account below will focus upon a single city, New York. However, the events that led to the institutionalization of New York’s Tammany machine were basically similar to those that took place in other large American cities…

This is just a free sample of the research paper, or part of the research paper on the given topic you have found at ProfEssays.com. If you feel you need professional writing assistance contact us! We will help you to create perfect research paper on any topic. ProfEssays.com – Leading custom essay and dissertation writing company and we are 24/7 open to serve you writing needs!

Don ‘ t hesitate! ORDER NOW !

Looking for an exceptional company to do some custom writing for you? Look no further than ProfEssays.com! You simply place an order with the writing instructions you have been given, and before you know it, your essay or term paper, completely finished and unique, will be completed and sent back to you. At ProfEssays.com, we have over 500 highly educated, professional writers standing by waiting to help you with any writing needs you may have! We understand students have plenty on their plates, which is why we love to help them out. Let us do the work for you, so you have time to do what you want to do!

- Customers' Testimonials

- Custom Book Report

- Help with Case Studies

- Personal Essays

- Custom Movie Review

- Narrative Essays

- Argumentative Essays

- Homework Help

- Essay Format

- Essay Outline

- Essay Topics

- Essay Questions

- How to Write a Research Paper

- Research Paper Format

- Research Paper Introduction

- Research Paper Outline

- Research Paper Abstract

- Research Paper Topics

Client Lounge

Deadline approaching.

- Free Samples

- Premium Essays

- Editing Services Editing Proofreading Rewriting

- Extra Tools Essay Topic Generator Thesis Generator Citation Generator GPA Calculator Study Guides Donate Paper

- Essay Writing Help

- About Us About Us Testimonials FAQ

- Studentshare

- Political Machines - Theodore Lowi

Political Machines - Theodore Lowi - Essay Example

- Subject: History

- Type: Essay

- Level: Ph.D.

- Pages: 4 (1000 words)

- Downloads: 4

- Author: candidolynch

Extract of sample "Political Machines - Theodore Lowi"

- Cited: 0 times

- Copy Citation Citation is copied Copy Citation Citation is copied Copy Citation Citation is copied

CHECK THESE SAMPLES OF Political Machines - Theodore Lowi

Political ideologies, the dynamics of the material and ideological conditions in society, metropolis movie and the industrial revolution, discussing theodore roosevelt's views of american nationalism and imperialism, why did progressive reformers believe it essential to curb the power of american capitalism, immigration in the 19th century, americanisation of media campaigns by british political parties.

- TERMS & CONDITIONS

- PRIVACY POLICY

- COOKIES POLICY

- study guides

- lesson plans

- homework help

Political machine Essay | Essay

Political Machines

FOLLOW BOOKRAGS:

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

political machine, in U.S. politics, a party organization, headed by a single boss or small autocratic group, that commands enough votes to maintain political and administrative control of a city, county, or state. The rapid growth of American cities in the 19th century, a result of both immigration and migration from rural areas, created huge ...

William Tweed, the "boss" of Tammany Hall, played a major role in New York City politics during the mid-1800s. By the late 1850s, Tweed had ascended through a variety of local offices, including volunteer firefighter, school commissioner, member of the county board of supervisors, and street commissioner. He learned to make political allies ...

Introduction. Machine politics is an exchange process in which it is seen as an essential way for those who would like to win the elections and the political machines encouraged the favors and the benefits of the votes in America. Political machines operated during the time when the public life was different from the home life.

Review a political machine definition to see why political machines were effective. Explore political machine examples, corruption, and impacts in U.S. history. Updated: 11/21/2023

Main body. One of the functions of political machines was serving immigrants to the USA. For the immigrants, the machines were vehicles for political enfranchisement. The immigrants did not have a sense of civic duty and traded votes for power. Irish immigrants were the brightest example of how immigrants could benefit from the machines.

The Democratic Party machine commanded in the southern part of the state by the political boss George Norcross, possibly the last powerful state machine operating anywhere in America, suffered ...

A political machine is an organization controlled by a powerful boss or group of people who enjoy the support of a section of the population (Tuckel & Maisel 100-101). The support base is large enough to deliver victory during elections. Political machines exist for mutual benefits to the members. In this case, politicians get votes while ...

A political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by the use of tangible incentives—money, political jobs—and that is characterized by a high degree of leadership control over member activity. Political machines started as grass roots organizations to gain the patronage needed to win the modern election. Having strong ...

The personalities and institutional expressions of political machines varied widely. Some twentieth century cases were built upon the charisma of populist leaders like James Curley of Boston or Huey Long of Louisiana. Others, like Chicago's Daley Machine, tracked closer to bureaucratic authoritarianism.

Compare historical arguments about the pros and cons of political machines; ... The thesis statement usually appears within the introduction of the essay or article and then reappears in the conclusion. Read through the excerpt from Argument #1 again and see if you can find the thesis statement. Remember, it could be one sentence or two, and it ...

the internal structure of political machines. The structure of this chapter broadly follows the structure of chapter 2. First I test if parties do in fact rely on large numbers of brokers. Next I test if these brokers can use the relationships that they have developed with voters to make voters more responsive to targeted goods.

Summer Eldred-Evans April 16, 2016 U.S. Urban History Essay: Urban America Discuss the political machine and its operations in the city, 1865 - 1939 The political machine is very powerful in the city and because of how powerful it is that urban United States was able to develop so much and increase in power in the late 1800's and early 1900's.

The political machine is very powerful in the city and because of how powerful it is that urban United States was able to develop so much and increase in power in the late 1800's and early 1900's. A political machine is system of political organization based on patronage, the spoils system, and political ties.

The following essay is reprinted with permission from The Conversation, ... Imagine that soon, political technologists develop a machine called Clogger - a political campaign in a black box ...

Essay Paper on Political Machines. Being an unofficial political system, political machine founds its activities on the basis of patronage, using the structure of representative democracy. Their important integrating role in American society is clearly viewed through country's history and successful implementation of its main principles.