The Poem “My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning Research Paper

Introduction, speaker and tone, stylistic devices, other stylistic devices, other characteristics, works cited.

This research paper presents a literary analysis of the poem “My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning. The poem itself represents a separate story but it is only after its detailed analysis that one can realize its expressiveness and the whole essence.

The poem was written in 1841 and is a monologue of the duke of Ferrara in Italy whose wife died in 1561. The overall impression the poem produces is positive though the desire of the writer to separate the speaker from himself makes it a little confusing. The dramatic monologue of the duke, and especially his manner of presenting the events, makes it possible for the reader to find out some facts from his life. Imparting his story with the presumed listeners the duke lets them decipher the meaning of what he is saying in his intricate expressions and word-combinations. Some readers keep to the point that numerous literary devices used in the poem make it very complicated to comprehend whereas others state that they make the duke’s speech even more expressive. There is a need to analyze literary devices the author of the poem uses to convey its meaning in order to find out their significance for this piece of writing.

The first four words of the poem can be used as key words for comprehending it as a whole. ‘ That’s’ helps the reader understand that the style of the poem is conversational. ‘ My’ tells the reader about the duke’s possession and that it was namely his duchess he is going to tell about. ‘Last’ suggests that this woman was not the first wife of duke’s which forms a certain idea about him and helps the reader acquire the first impression about the character. And finally, ‘ Duchess’ presupposes that already reading this first line the reader must imagine what the duchess is supposed to look like and then compare this image to what will be described further.

It can be noticed that the speaker of “My Last Duchess” is addressing another person and lets the reader watch this conversation. By removing himself as the center of attention, the poet allows us to replace him (Joseph A. Dupras 3) and to view the presented story from the perspective of observers. The speaker’s tone gives the reader the impression of an arrogant person who treats his property rather selfishly; the tone makes it clear that the speaker did not like his wife’s flirting with other man and shows what it led to “Whene’er I passed her; but who passed without/Much the same smile? / This grew; I gave commands; /Then all smiles stopped together” (Robert Browning, Eileen Gillooly and Joel Spector 21).

The poem displays a frequent use of stylistic devices which make it more colorful and help the speaker express his emotion. Therefore, a number of simple cognitive metaphors is used: “spot of joy” which can be observed in lines fourteen and fifteen in order to turn attention to the beauty of the duchess’s cheeks which blushed easily; “depth and passion of its earnest glance” (Robert Browning, Eileen Gillooly and Joel Spector 20) is used to show that the painting indeed resembled the original and emphasizes the beauty of the duchess; “a heart […] too soon made glad, to easily impressed” (Robert Browning, Eileen Gillooly and Joel Spector 20) shows the duchess naivety and frivolity; “then all smiles stopped together” (Robert Browning, Eileen Gillooly and Joel Spector 21) is used by the author to show the abrupt change of the state of affairs.

The irony can be observed in duke’s describing the painting using personification and pointing at its “depth” and “passion” which clearly contradicts what he in fact says about the actual person. Another irony is realized in the lines where the duke speaks of his having no speech skills when indeed before that he was talking very eloquently and in rhymes. This is deliberately used by him in order to conceal his arrogance and selfishness. And, eventually, Browning uses a dramatic irony which completely reflects the callousness of the duke’s character when he is calling the girl “my object” which shows that he is treating her as another possession of his.

As for other stylistic devices in the poem, simile can be observed in the line ““Looking as if she were alive” (Robert Browning, Eileen Gillooly and Joel Spector 20) which both lets the reader know that the duchess is already dead and shows that the painting was performed by a talented artist. Parenthesis in lines nine and ten is another reminding of a selfish character of the duke who is pointing out that it is only his permission that lets to draw the curtains.

Ultimately, it should be mentioned that the poem is written in AABB rhyme scheme and its syntax has a loose and relaxed manner. The emotional climax is achieved by the line “Then all the smiles stopped” (Robert Browning, Eileen Gillooly and Joel Spector 21) when the overall tone of the poem is changing from enthusiastic description of beauty to a sad and serious telling about duke’s ordering to murder his wife.

Taken into consideration everything mentioned above it can be stated that numerous literary devices the author uses in the poem make it even more comprehensive and facilitates understanding of the concealed ideas. Literary devices make the poem bright and fresh and if they were absent, the poem would miss emotional coloring and expressiveness.

Robert Browning, Eileen Gillooly, Joel Spector. Robert Browning: Robert Browning. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., 2003

Dupras, Joseph A. “Browning’s “My Last Duchess”: Paragon and Parergon”. Papers on Language & Literature 32.1(1996): 3 Questia. 2009. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, March 10). The Poem “My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-poem-my-last-duchess-by-robert-browning/

"The Poem “My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning." IvyPanda , 10 Mar. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/the-poem-my-last-duchess-by-robert-browning/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'The Poem “My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning'. 10 March.

IvyPanda . 2024. "The Poem “My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning." March 10, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-poem-my-last-duchess-by-robert-browning/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Poem “My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning." March 10, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-poem-my-last-duchess-by-robert-browning/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Poem “My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning." March 10, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-poem-my-last-duchess-by-robert-browning/.

- Victorian Literature: "My Last Duchess" by Robert Browning

- "My Last Duchess" by Robert Browning Poem Analysis

- "My Last Duchess" Poem by Robert Browning

- Comparing Browning’s “My Last Duchess” With Poe’s “The Raven”

- “My Last Duchess” by Browning and “Daddy” by Plath

- Duke of Ferrara in “My Last Duchess” Poem by Browning

- Browning's "My Last Duchess" vs. Poe's "The Cask of Amontillado"

- "The Yellow Wallpaper" by Gilman and "My Last Duchess" by Browning

- Comparative Literature for Robert Browning and Elizabeth Barrett Browning

- Poems Comparison: "To His Coy Mistress" and "My Last Duchess"

- Italian Sonnets: The Structure and Thematic Organization

- T. S. Eliot’s “Hollow Men”

- The Theme of Hospitality on the Island of Ogygia with Calypso

- “Sylvia’s Death” by Anne Sexton

- Twentieth Century Literature: Derek Walcott and Lu Xun

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Literature › Analysis of Robert Browning’s My Last Duchess

Analysis of Robert Browning’s My Last Duchess

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on March 30, 2021 • ( 0 )

My Last Duchess

“My Last Duchess” appeared in Browning’s first collection of shorter poems, Dramatic Lyrics (1842). In the original edition, the poem is printed side-by-side with “Count Gismond” under the heading “Italy and France,” and the two poems share a similar concern with issues of aristocracy and honor. “My Last Duchess” is one of many poems by Browning that are founded, at least in part, upon historical fact. Extensive research lies behind much of Browning’s work, and “My Last Duchess” represents a confluence of two of Browning’s primary interests: the Italian Renaissance and visual art. Both the speaker of the poem and his “last Duchess” closely resemble historical figures. The poem’s duke is likely modeled upon Alfonso II, the last Duke of Ferrara, whose marriage to the teenaged Lucrezia de’ Medici ended mysteriously only three years after it began. The duke then negotiated through an agent to marry the niece of the Count of Tyrol.

True to the title of the volume in which the poem appears, “My Last Duchess” begins with a gesture performed before its first couplet—the dramatic drawing aside of a “curtain” in front of the painting. From its inception, the poem plays upon the notion of the theatrical, as the impresario duke delivers a monologue on a painting of his late wife to an envoy from a prospective duchess. That the poem constitutes, structurally, a monologue, bears significantly upon its meaning and effects. Browning himself summed up Dramatic Lyrics as a gathering of “so many utterances of so many imaginary persons, not mine,” and the sense of an authorial presence outside of “My Last Duchess” is indeed diminished in the wake of the control the duke seems to wield over the poem. The fact that the duke is the poem’s only voice opens his honesty to question, as the poem offers no other perspective with which to compare or contrast that of the duke. Dependence on the duke as the sole source of the poem invites in turn a temporary sympathy with him, in spite of his outrageous arrogance and doubtlessly criminal past. The poem’s single voice also works to focus attention on the duke’s character: past deeds pale as grounds for judgment, becoming just another index to the complex mind of the aristocrat.

In addition to foregrounding the monologic and theatrical nature of the poem, the poem’s first dozen lines also thematize notions of repetition and sequence, which are present throughout the poem. “That’s my last Duchess,” the duke begins, emphasizing her place in a series of attachments that presumably include a “first” and a “next.” The stagy gesture of drawing aside the curtain is also immanently repeatable: the duke has shown the painting before and will again. Similarly, the duke locates the envoy himself within a sequence of “strangers” who have “read” and been intrigued by the “pictured countenance” of the duchess. What emerges as the duke’s central concern—the duchess’s lack of discrimination—also relates to the idea of repetition, as the duke outlines a succession of gestures, events, and individuals who “all and each/Would draw from her alike the approving speech.” The duke’s very claim to aristocratic status rest upon a series—the repeated passing on of the “nine-hundred-years-old name” that he boasts. The closing lines of “My Last Duchess” again suggest the idea of repetition, as the duke directs the envoy to a statue of Neptune: “thought a rarity,” the piece represents one in a series of artworks that make up the duke’s collection. The recurrent ideas of repetition and sequence in the poem bind together several of the poem’s major elements—the duke’s interest in making a new woman his next duchess and the vexingly indiscriminate quality of his last one, the matter of his aristocratic self-importance and that of his repugnant acquisitiveness, each of which maps an aspect of the duke’s obsessive nature.

This obsessiveness also registers in the duke’s fussy attention to his own rhetoric, brought up throughout the poem in the form of interjections marked by dashes in the text. “She had/a heart—how shall I say—too soon made glad,” the duke says of his former duchess, and his indecision as to word choice betrays a tellingly careful attitude toward discourse. Other such self-interruptions in the poem describe the duke’s uncertainty as to the duchess’s too easily attained approval, as well as his sense of being an undiplomatic speaker. On the whole, these asides demonstrate the duke’s compulsive interest in the pretence of ceremony, which he manipulates masterfully in the poem. Shows of humility strengthen a sense of the duke’s sincerity and frank nature, helping him build a rapport with his audience. The development of an ostensibly candid persona works to cloak the duke’s true “object”—the dowry of his next duchess.

Lucrezia de’ Medici by Bronzino, generally believed to be the subject of the poem/Wikimedia

Why the duke broaches the painful matter of his sordid past in the first place is well worth considering and yields a rich vein of psychological speculation. Such inquiry should be tempered, however, by an awareness of the duke’s overt designs in recounting his past. On the surface, for instance, the poem constitutes a thinly veiled warning: the duke makes a show of his authority even as he lets out some of the rather embarrassing details surrounding his failed marriage. The development of the duchess’s seeming disrespect is cut short by the duke’s “commands”—almost certainly orders to have her quietly murdered. In the context of a meeting with the envoy of a prospective duchess, the duke’s confession cannot but convey a threat, a firm declaration of his intolerance toward all but the most respectful behavior.

But the presence of an underlying threat cannot fully account for the duke’s rhetorical exuberance, and the speech the poem embodies must depend for its impetus largely upon the complex of emotional tensions that the memory calls up for the duke. As critic W. David Shaw remarks, the portrait of the last duchess represents both a literal and a figurative “hang-up” for the duke, who cannot resist returning to it repeatedly to contemplate its significance. So eager is the duke to enlarge upon the painting and its poignance that he anticipates and thus helps create the envoy’s interest in it, assuming in him a curiousity as to “how such a glance came” to the countenance of the duchess. The duke then indulges in obsessive speculation on the “spot of joy” on the “Duchess’ cheek,” elaborating different versions of its genesis. Similarly, the duke masochistically catalogues the various occasions the duchess found to “blush” or give praise: love, sunsets, cherries, and even “the white mule/She rode with round the terrace.”

Language itself occupies a particularly troubled place in the duke’s complex response to his last duchess and her memory. The duke’s modesty in declaiming his “skill/In speech” is surely false, as the rhetorical virtuosity of his speech attests. Yet he is manifestly averse to resolving the issue through discussion. In the duke’s view, “to be lessoned” or lectured is to be “lessened” or reduced, as his word choice phonetically implies. Rather than belittle himself or his spouse through the lowly practice of negotiation, the duke sacrifices the marriage altogether, treating the duchess’s “trifling” as a capital offense. The change the duke undergoes in the wake of disposing of his last duchess is in large part a rhetorical one, as he “now” handles discursively what he once handled with set imperatives.

The last lines of the poem abound in irony. As they rise to “meet/The company below,” the duke ominously reminds the envoy that he expects an ample dowry by way of complimenting the “munificence” of the Count. The duke then tells the envoy that not money but the Count’s daughter herself remains his true “object,” suggesting the idea that the duke’s aim is precisely the contrary. The duke’s intention to “go/Together down” with the envoy, meant on the surface as a kind of fraternal gesture, ironically underscores the very distinction in social status that it seems to erase. “Innsbruck” is the seat of the Count of Tyrol whose daughter the duke means to marry, and he mentions the bronze statue with a pride that is supposed to flatter the Count. But the lines can also be interpreted as an instance of self-flattery, as Neptune, who stands for the duke, is portrayed in the sculpture as an authorial figure, “taming a sea-horse.”

“My Last Duchess” marks an early apex of Browning’s art, and some of the elements of the poem—such as the monologue form, the discussion of visual art, and the Renaissance setting—were to become staples of Browning’s aesthetic. “My Last Duchess” also inaugurates Browning’s use of the lyric to explore the psychology of the individual. As many critics have suggested, character for Browning is always represented as a process, and the attitudes of his characters are typically shown in flux. The duke of “My Last Duchess” stands as a testimony to Browning’s ability to use monologue to frame an internal dialogue: the duke talks to the envoy but in effect talks to himself as he compulsively confronts the enigmas of his past.

Further Reading Bloom, Harold, ed. Robert Browning. New York: Chelsea House, 1985. Bloom, Harold, and Adrienne Munich, eds. Robert Browning: A Collection of Critical Essays. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1979. Chesterton, G. K. Robert Browning. London: Macmillan, 1903. Cook, Eleanor. Browning’s Lyrics: An Exploration. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1974. Crowell, Norton B. The Convex Glass: The Mind of Robert Browning. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1968. De Vane, William Clyde, and Kenneth Leslie Knickerbocker, eds. New Letters. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1950. De Vane, William Clyde. A Browning Handbook. New York: F. S. Crofts and Co., 1935. Drew, Philip. The Poetry of Robert Browning: A Critical Introduction. London: Methuen, 1970. Jack, Ian. Browning’s Major Poetry. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973. Jack, Ian, and Margaret Smith, eds. The Poetical Works of Robert Browning. New York: Oxford University Press, 1983. Wagner-Lawlor, Jennifer A. “The Pragmatics of Silence, and the Figuration of the Reader in Browning’s Dramatic Monologues.” Victorian Poetry 35, no. 3 (1997): 287–302. Source: Bloom, H., 2001. Broomall, PA: Chelsea House Publishers.

Share this:

Categories: Literature

Tags: Analysis of Robert Browning's My Last Duchess , Critical Analysis of Robert Browning's My Last Duchess , Criticism of Robert Browning's My Last Duchess , Essays of Robert Browning's My Last Duchess , Literary Criticism , My Last Duchess , My Last Duchess character study , My Last Duchess dramatic monologue , My Last Duchess poem , My Last Duchess poem summary , My Last Duchess themes , Notes of Robert Browning's My Last Duchess , Plot of Robert Browning's My Last Duchess , Poetry , Robert Browning , Robert Browning's My Last Duchess , Robert Browning's My Last Duchess Summary , Robert Browning's My Last Duchess essays , Robert Browning's My Last Duchess notes , Robert Browning's My Last Duchess plot , Robert Browning's My Last Duchess structure , Robert Browning's My Last Duchess themes , Structure of Robert Browning's My Last Duchess , Summary of Robert Browning's My Last Duchess , Themes of Robert Browning's My Last Duchess , Victorian Literature

Related Articles

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

My Last Duchess Summary & Analysis by Robert Browning

- Line-by-Line Explanation & Analysis

- Poetic Devices

- Vocabulary & References

- Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme

- Line-by-Line Explanations

“My Last Duchess” is a dramatic monologue written by Victorian poet Robert Browning in 1842. In the poem, the Duke of Ferrara uses a painting of his former wife as a conversation piece. The Duke speaks about his former wife's perceived inadequacies to a representative of the family of his bride-to-be, revealing his obsession with controlling others in the process. Browning uses this compelling psychological portrait of a despicable character to critique the objectification of women and abuses of power.

- Read the full text of “My Last Duchess”

The Full Text of “My Last Duchess”

FERRARA

1 That’s my last Duchess painted on the wall,

2 Looking as if she were alive. I call

3 That piece a wonder, now; Fra Pandolf’s hands

4 Worked busily a day, and there she stands.

5 Will’t please you sit and look at her? I said

6 “Fra Pandolf” by design, for never read

7 Strangers like you that pictured countenance,

8 The depth and passion of its earnest glance,

9 But to myself they turned (since none puts by

10 The curtain I have drawn for you, but I)

11 And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst,

12 How such a glance came there; so, not the first

13 Are you to turn and ask thus. Sir, ’twas not

14 Her husband’s presence only, called that spot

15 Of joy into the Duchess’ cheek; perhaps

16 Fra Pandolf chanced to say, “Her mantle laps

17 Over my lady’s wrist too much,” or “Paint

18 Must never hope to reproduce the faint

19 Half-flush that dies along her throat.” Such stuff

20 Was courtesy, she thought, and cause enough

21 For calling up that spot of joy. She had

22 A heart—how shall I say?— too soon made glad,

23 Too easily impressed; she liked whate’er

24 She looked on, and her looks went everywhere.

25 Sir, ’twas all one! My favour at her breast,

26 The dropping of the daylight in the West,

27 The bough of cherries some officious fool

28 Broke in the orchard for her, the white mule

29 She rode with round the terrace—all and each

30 Would draw from her alike the approving speech,

31 Or blush, at least. She thanked men—good! but thanked

32 Somehow—I know not how—as if she ranked

33 My gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name

34 With anybody’s gift. Who’d stoop to blame

35 This sort of trifling? Even had you skill

36 In speech—which I have not—to make your will

37 Quite clear to such an one, and say, “Just this

38 Or that in you disgusts me; here you miss,

39 Or there exceed the mark”—and if she let

40 Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set

41 Her wits to yours, forsooth, and made excuse—

42 E’en then would be some stooping; and I choose

43 Never to stoop. Oh, sir, she smiled, no doubt,

44 Whene’er I passed her; but who passed without

45 Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands;

46 Then all smiles stopped together. There she stands

47 As if alive. Will’t please you rise? We’ll meet

48 The company below, then. I repeat,

49 The Count your master’s known munificence

50 Is ample warrant that no just pretense

51 Of mine for dowry will be disallowed;

52 Though his fair daughter’s self, as I avowed

53 At starting, is my object. Nay, we’ll go

54 Together down, sir. Notice Neptune, though,

55 Taming a sea-horse, thought a rarity,

56 Which Claus of Innsbruck cast in bronze for me!

“My Last Duchess” Summary

“my last duchess” themes.

The Objectification of Women

- See where this theme is active in the poem.

Social Status, Art, and Elitism

Control and Manipulation

Line-by-line explanation & analysis of “my last duchess”.

That’s my last Duchess painted on the wall, Looking as if she were alive. I call That piece a wonder, now; Fra Pandolf’s hands Worked busily a day, and there she stands. Will’t please you sit and look at her?

I said “Fra Pandolf” by design, for never read Strangers like you that pictured countenance, The depth and passion of its earnest glance, But to myself they turned (since none puts by The curtain I have drawn for you, but I) And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst, How such a glance came there; so, not the first Are you to turn and ask thus.

Lines 13-19

Sir, ’twas not Her husband’s presence only, called that spot Of joy into the Duchess’ cheek; perhaps Fra Pandolf chanced to say, “Her mantle laps Over my lady’s wrist too much,” or “Paint Must never hope to reproduce the faint Half-flush that dies along her throat.”

Lines 19-24

Such stuff Was courtesy, she thought, and cause enough For calling up that spot of joy. She had A heart—how shall I say?— too soon made glad, Too easily impressed; she liked whate’er She looked on, and her looks went everywhere.

Lines 25-31

Sir, ’twas all one! My favour at her breast, The dropping of the daylight in the West, The bough of cherries some officious fool Broke in the orchard for her, the white mule She rode with round the terrace—all and each Would draw from her alike the approving speech, Or blush, at least.

Lines 31-34

She thanked men—good! but thanked Somehow—I know not how—as if she ranked My gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name With anybody’s gift.

Lines 34-43

Who’d stoop to blame This sort of trifling? Even had you skill In speech—which I have not—to make your will Quite clear to such an one, and say, “Just this Or that in you disgusts me; here you miss, Or there exceed the mark”—and if she let Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set Her wits to yours, forsooth, and made excuse— E’en then would be some stooping; and I choose Never to stoop.

Lines 43-47

Oh, sir, she smiled, no doubt, Whene’er I passed her; but who passed without Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands; Then all smiles stopped together. There she stands As if alive.

Lines 47-53

Will’t please you rise? We’ll meet The company below, then. I repeat, The Count your master’s known munificence Is ample warrant that no just pretense Of mine for dowry will be disallowed; Though his fair daughter’s self, as I avowed At starting, is my object.

Lines 53-56

Nay, we’ll go Together down, sir. Notice Neptune, though, Taming a sea-horse, thought a rarity, Which Claus of Innsbruck cast in bronze for me!

“My Last Duchess” Symbols

The Painting

- See where this symbol appears in the poem.

The Statue of Neptune

“my last duchess” poetic devices & figurative language.

- See where this poetic device appears in the poem.

Personification

“my last duchess” vocabulary.

Select any word below to get its definition in the context of the poem. The words are listed in the order in which they appear in the poem.

- Fra Pandolf

- Countenance

- Munificence

- See where this vocabulary word appears in the poem.

Form, Meter, & Rhyme Scheme of “My Last Duchess”

Rhyme scheme, “my last duchess” speaker, “my last duchess” setting, literary and historical context of “my last duchess”, more “my last duchess” resources, external resources.

Robert Browning's Answers to Some Questions, 1914 — In March of 1914, Cornhill Magazine interviewed Robert Browning about some of his poems, including "My Last Duchess." He briefly explains his thoughts on the duchess.

Chris de Burgh, "The Painter" (1976) — Chris de Burgh (a Northern Irish singer-songwriter, best known for "Lady in Red") wrote a song from the perspective of the Duke of Ferrara about his former wife, in which the duchess was having an affair with Fra Pandolf.

My Last Duchess Glass Window — The Armstrong Browning Library and Museum at Baylor University has a stained glass window inspired by "My Last Duchess."

Julian Glover performs "My Last Duchess" — Actor Julian Glover performs "My Last Duchess" with a suitably dramatic tone of voice. Note how he emphasizes the conversational quality of the poem.

Nikolaus Mardruz to his Master Ferdinand, Count of Tyrol, 1565 by Richard Howard, 1929 — This poem by American poet Richard Howard provides the Ferrara's guest's perspective on the meeting between himself and the duke.

LitCharts on Other Poems by Robert Browning

A Light Woman

Among the Rocks

A Toccata of Galuppi's

A Woman's Last Word

Confessions

Home-Thoughts, from Abroad

How they Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix

Life in a Love

Love Among the Ruins

Love in a Life

Meeting at Night

Pictor Ignotus

Porphyria's Lover

Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister

The Bishop Orders His Tomb at Saint Praxed's Church

The Laboratory

The Last Ride Together

The Lost Leader

The Lost Mistress

The Patriot

The Pied Piper of Hamelin

Women and Roses

Everything you need for every book you read.

A Summary and Analysis of Robert Browning’s ‘My Last Duchess’

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

Probably Robert Browning’s most famous (and widely studied) dramatic monologue, ‘My Last Duchess’ is spoken by the Duke of Ferrara, chatting away to an acquaintance (for whom we, the reader, are the stand-in) and revealing a sinister back-story lurking behind the portrait of his late wife, the Duchess, that adorns the wall.

It’s easy enough to summarise ‘My Last Duchess’ in a one-sentence synopsis like this, but how Browning unnerves us with the Duke’s account of the portrait, and his relationship with his wife, lies in what he hints or reveals as much as in what he simply states. So a few words of analysis would perhaps help elucidate how Browning uses the dramatic monologue form to such great effect here.

Let’s go through the poem, stopping to summarise and analyse what’s going on, stage by stage.

My Last Duchess

That’s my last Duchess painted on the wall, Looking as if she were alive. I call That piece a wonder, now; Fra Pandolf’s hands Worked busily a day, and there she stands.

We’re given the location first of all: Ferrara, a city in northern Italy. Given the words ‘my last Duchess’, the first line immediately reveals to us that this is the Duke of Ferrara speaking to us.

Because of the performative gesture implicit within that opening line (‘That’s my last Duchess painted on the wall’ being almost accompanied by an imagined flourish, as the Duke’s finger points at the portrait hanging on the wall), we can say we’re in dramatic monologue territory: the speaker of the poem is addressing us as his audience (a man, whom the Duke addresses as ‘Sir’ at several points), in a specific setting.

Thereafter, we learn that the Duke’s wife is dead: again, this is implied by the use of the subjunctive mood in the second line (‘Looking as if she were alive’: i.e., she isn’t any more). Fra Pandolf, we deduce, is the artist who painted the Duchess’s portrait. He worked hard at the painting for a day and this portrait, which the Duke considers ‘a wonder’, is the result.

Will’t please you sit and look at her? I said ‘Fra Pandolf’ by design, for never read Strangers like you that pictured countenance, The depth and passion of its earnest glance, But to myself they turned (since none puts by The curtain I have drawn for you, but I) And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst, How such a glance came there; so, not the first Are you to turn and ask thus.

More performance and posturing that show we’re in the realm of the dramatic monologue: the Duke encourages his audience, this other man, to sit there and admire the portrait of his ‘last Duchess’. (We’ve glossed over the sinister implication in the phrase ‘ last Duchess’: i.e., his dead wife was not his first wife, and he seems to be in the habit of losing them. What happens to all of them? How come they die so soon after marrying him?)

The Duke admits, in a sort of humblebrag, that he name-dropped the artist, Fra Pandolf, on purpose, because it took a brilliant painter to capture the distinctive expression or ‘glance’ in the Duchess’s face. How did she come to have such an expression?

Many other guests of the Duke’s, before his present guest, have asked him, and he usually keeps the painting concealed behind a curtain; but when people enquire about his wife, he will pull aside the curtain and show her to them.

Note also the continual conflation of the Duchess herself (now dead) with her portrait: she has become art, and an object, embodied by Fra Pandolf’s painting of her on canvas. But was the real duchess similarly viewed as an object by her husband?

Sir, ’twas not Her husband’s presence only, called that spot Of joy into the Duchess’ cheek; perhaps Fra Pandolf chanced to say, ‘Her mantle laps Over my lady’s wrist too much,’ or ‘Paint Must never hope to reproduce the faint Half-flush that dies along her throat.’ Such stuff Was courtesy, she thought, and cause enough For calling up that spot of joy. She had A heart—how shall I say?— too soon made glad, Too easily impressed; she liked whate’er She looked on, and her looks went everywhere.

The Duke uses the look on his dead wife’s face as a way into discussing her character, and telling his guests about her personality.

It wasn’t simply the Duke’s presence in the room as she sat for the portrait that caused her to look so pleased; indeed, even the most neutral and professional requests and pleasantries from the painter would have made her blush with delight, because she was easily flattered when people praised her beauty.

What’s more, she had a roving eye (‘her looks went everywhere’), so even though she was married to the Duke, she sought out praise and flattery from other people (especially men).

Sir, ’twas all one! My favour at her breast, The dropping of the daylight in the West, The bough of cherries some officious fool Broke in the orchard for her, the white mule She rode with round the terrace—all and each Would draw from her alike the approving speech, Or blush, at least.

All of the trivial gifts and tokens people brought the Duchess were greeted with the same blush of joy, whether it was a ‘favour’ (e.g. a flower) the Duke himself brought to her for her to wear on her dress, or even the beautiful sunset (and the coming of night – when people’s thoughts might turn in an amorous direction), some cherries from the orchard someone who worked for the Duke had brought for her to eat, or a mule (‘white’ suggesting purity, but the sterility of the mule – which cannot breed – perhaps hinting that the Duke himself, when the Duchess ‘rode’ him, was too old to get her pregnant).

In short, the Duchess was easily pleased – too easily pleased for the Duke’s liking.

She thanked men—good! but thanked Somehow—I know not how—as if she ranked My gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name With anybody’s gift.

Now we get to the thrust of the Duke’s grievance with his dead wife. He reveals perhaps more than he intends to with this remark, showing that he was proud, haughty, perhaps even slightly insecure and jealous (that potential sexual impotence or sterility again), and didn’t like the fact that his wife, who had married a Duke with a noble lineage stretching back almost a millennium, treated his gifts the same as those from ‘anybody’.

And by these ‘anybodies’ the Duke really means, nobodies , for that is what he considers them to be next to him. He is a Duke; who are they? Yet their gifts inspire the same response from the Duchess as the Duke’s lavish gifts.

Who’d stoop to blame This sort of trifling? Even had you skill In speech—which I have not—to make your will Quite clear to such an one, and say, ‘Just this Or that in you disgusts me; here you miss, Or there exceed the mark’—and if she let Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set Her wits to yours, forsooth, and made excuse— E’en then would be some stooping; and I choose Never to stoop.

The Duke (rhetorically) addresses his guest. He asks him: which nobleman should lower himself by seeking to instruct his wife about how she should behave? As a duke, you shouldn’t have to deal with such petty trivialities (‘trifling’).

Oh, sir, she smiled, no doubt, Whene’er I passed her; but who passed without Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands; Then all smiles stopped together. There she stands As if alive.

The Duchess smiled whenever she saw her husband, but she smiled at everyone else, too. It got worse, so he ‘gave commands’. This is a stroke of real skill from Browning: at first, we might deduce that he ‘gave commands’ to her to stop smiling at everyone who looked at her.

But hang about, wouldn’t that go against his previous statement that he refused to ‘stoop’, to debase himself by addressing such matters with her? No: we realise that there is something more sinister going on: the commands the Duke gave were orders to others, perhaps hired henchmen or assassins, who killed the Duchess and thus ‘stopped’ ‘all smiles’ (both those from her admirers, and from her in return).

Will’t please you rise? We’ll meet The company below, then. I repeat, The Count your master’s known munificence Is ample warrant that no just pretence Of mine for dowry will be disallowed;

And then, presumably as calm and collected as can be as though he hasn’t just confessed to organising his wife’s murder, the Duke calls for his guest to stand up so they can both go downstairs to meet the rest of their companions.

We then realise that the Duke is already arranging for his next marriage: indeed, the Duke’s guest is a representative of another nobleman, a Count, whose daughter the Duke is planning to make his next duchess (with the Count paying a handsome dowry to the Duke for marrying her: this is a marriage for money, of course, and given how many duchesses the Duke has married and disposed of, we deduce that he is quite advanced in years). Poor girl doesn’t know what she’s letting herself in for …

Though his fair daughter’s self, as I avowed At starting, is my object.

This declaration now rings with a menacing overtone: his ‘object’ for what? He’s saying he wants to marry the Count’s daughter for her, not for her big dowry that will bring him lots of land or cash. But ‘object’ suggests a trinket to be shown off and then, perhaps, discarded when the Duke starts to feel another pang of jealousy about how many young men are admiring his young, pretty wife.

Nay, we’ll go Together down, sir. Notice Neptune, though, Taming a sea-horse, thought a rarity, Which Claus of Innsbruck cast in bronze for me!

The Duke’s final words to his listener are about a bronze sculpture which another artist made for him. The symbolism of this sculpture is obvious: the depiction of Neptune the Roman sea god using his divine force to tame or subdue a wild seahorse obviously mirrors the Duke’s own attitudes and temperament. He uses his power and might to crush those who oppose or displease him. The beautiful seahorse is being destroyed by the much more powerful god, much as the Duke’s young, beautiful wife was crushed by him.

‘My Last Duchess’ is a masterpiece because it does what Browning’s dramatic monologues do best: invites us into the confidence of a speaker whose conversation reveals more about their personality and actions than they realise. The poem is not a narrative poem because it has a speaker rather than a narrator, but it nevertheless tells a story of a doomed marriage, a man capable only of irrational jealousy and possessive force, and male pride (indeed, arrogance and privilege too) that barely conceals the fragile masculinity just lurking beneath.

We should feel thoroughly uncomfortable when we finish reading the poem for the first time, because we have just heard a man confessing to the murder of his wife – and, perhaps, other wives – without actually confessing. Compare, here, the calm, even proud tone of the speaker of another of Browning’s great dramatic monologues, ‘ Porphyria’s Lover ’.

Finally, it’s worth mentioning, as a sort of footnote to this analysis, the form Browning employs. He uses iambic pentameter , which is handy for conveying the rhythms of ordinary English speech, but he doesn’t deploy blank verse .

Instead, he offers us the more stately and grand rhyming couplets or ‘heroic couplets’ associated with grander themes. These heroic couplets convey the Duke’s need for order in his life, his possessive control over everything around him (especially his wife), but also his self-importance.

8 thoughts on “A Summary and Analysis of Robert Browning’s ‘My Last Duchess’”

Two additions to an otherwise helpful analysis: First, a duke is higher than a count, so if the count could marry his daughter to a duke, he would be raising his own status and that of his whole family very considerably. The hierarchy from high to low is as follows: duke, marquis, count and earl (equal), viscount and baron.

The girl is question is thus seen as nothing more than a commodity from both sides of the equation, not merely from the Duke’s side!

Second, attention must be paid to a few crucial words that the analysis leaves out of consideration: “Nay, we’ll go / Together down, Sir!” What is being implied here? Namely that the count’s emissary has understood from the whole monolgue what we also understand, that the Duke is a monster and the count’s daughter would be greatly endangered if she married him! He tries to go downstairs immediately to warn the Count himself or his high-ranking officials (“the company below”) about what he has just heard, but is prevented from doing so by the Duke, who is too fast for him!

The fate of the next “my last Duchess” is already sealed!

By placing the poem in Ferrara Browning is pretty well identifying his speaker with Alfonso II d’Este, the fifth Duke of Ferrara, who did marry a young, and if her portrait can be trusted, beautiful girl. He left her after one year of marriage, and she died 2 years later, at only 17. He was 25 when he married, so he was neither elderly, nor (presumably) impotent, nor had he had a string of wives before her, (the word ‘last’ can indicate ‘previous’), although he did marry twice more – he was 63 when he died, which gave him plenty of time. Popular gossip did ascribe his first wife’s death to poison, although TB seems to have been a more likely cause. However, the fact that his grandmother was Lucrezia Borgia probably didn’t help his reputation.

I have taught this poem as a work of mystery, asking my students to form a defensible thesis of the duchess’s fate based on evidence found in the poem.

One of my ‘party pieces’! Gains much from being ‘acted’.

- Pingback: Sunday Post – 14th June, 2020 #Brainfluffbookblog #SundayPost | Brainfluff

- Pingback: A Short Analysis of Robert Browning’s ‘Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister’ - Interesting Literature

- Pingback: 10 of the Best Robert Browning Poems Everyone Should Read - Interesting Literature

- Pingback: 10 of the Best Ekphrastic Poems about Pictures – Interesting Literature

Comments are closed.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

21 “My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning (Dramatic Monologue)

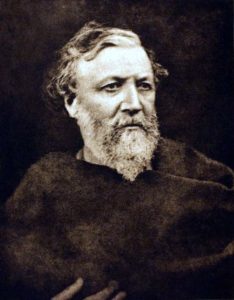

Robert Browning was born on May 7, 1812, in Camberwell, England. His mother was an accomplished pianist and a devout evangelical Christian. His father worked as a bank clerk and was also an artist, scholar, antiquarian, and collector of books and pictures. His rare book collection of more than 6,000 volumes included works in Greek, Hebrew, Latin, French, Italian, and Spanish. Much of Browning’s education came from his well-read father. It is believed that he was already proficient at reading and writing by the age of five. A bright and anxious student, Browning learned Latin, Greek, and French by the time he was fourteen. From fourteen to sixteen, he was educated at home, attended to by various tutors in music, drawing, dancing, and horsemanship.

At the age of twelve, he wrote a volume of Byronic verse entitled Incondita , which his parents attempted, unsuccessfully, to have published. In 1825, a cousin gave Browning a collection of Shelley’s poetry; Browning was so taken with the book that he asked for the rest of Shelley’s works for his thirteenth birthday, and declared himself a vegetarian and an atheist in emulation of the poet. Despite this early passion, he apparently wrote no poems between the ages of thirteen and twenty. In 1828, Browning enrolled at the University of London, but he soon left, anxious to read and learn at his own pace. The random nature of his education later surfaced in his writing, leading to criticism of his poems’ obscurities.

In 1833, Browning anonymously published his first major published work, Pauline , and in 1840, he published Sordello , which was widely regarded as a failure. He also tried his hand at drama, but his plays, including Strafford , which ran for five nights in 1837, and the Bells and Pomegranates series, were for the most part unsuccessful. Nevertheless, the techniques he developed through his dramatic monologues—especially his use of diction, rhythm, and symbol—are regarded as his most important contribution to poetry, influencing such major poets of the twentieth century as Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, and Robert Frost.

After reading Elizabeth Barrett’s Poems (1844) and corresponding with her for a few months, Browning met her in 1845. They were married in 1846, against the wishes of Barrett’s father. The couple moved to Pisa and then Florence, where they continued to write. They had a son, Robert “Pen” Browning, in 1849, the same year Browning’s Collected Poems was published. Elizabeth inspired Robert’s collection of poems Men and Women (1855), which he dedicated to her. Now regarded as one of Browning’s best works, the book was received with little notice at the time; its author was then primarily known as Elizabeth Barrett’s husband.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning died in 1861, and Robert and Pen Browning moved to London soon after. Browning went on to publish Dramatis Personae (1864), and The Ring and the Book (1868). The latter, based on a seventeenth century Italian murder trial, received wide critical acclaim, finally earning Browning renown and respect in the twilight of his career. The Browning Society was founded in 1881, and he was awarded honorary degrees by Oxford University in 1882 and the University of Edinburgh in 1884. Robert Browning died on the same day that his final volume of verse, Asolando , was published, in 1889.

My Last Duchess

FERRARA [1]

That’s my last Duchess [2] painted on the wall, Looking as if she were alive. I [3] call That piece a wonder, now; Fra Pandolf’s [4] hands Worked busily a day, and there she stands. 5 Will’t please you sit and look at her? I said “Fra Pandolf” by design, for never read Strangers like you that pictured countenance, The depth and passion of its earnest glance, But to myself they turned (since none puts by 10 The curtain I have drawn for you, but I) And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst, How such a glance came there; so, not the first Are you to turn and ask thus. Sir, ’twas not Her husband’s presence only, called that spot 15 Of joy into the Duchess’ cheek; perhaps Fra Pandolf chanced to say, “Her mantle [5] laps Over my lady’s wrist too much,” or “Paint Must never hope to reproduce the faint Half-flush that dies along her throat.” [6] Such stuff 20 Was courtesy, she thought, and cause enough For calling up that spot of joy. She had A heart—how shall I say?— too soon made glad, Too easily impressed; she liked whate’er She looked on, and her looks went everywhere. 25 Sir, ’twas all one! My favour at her breast, The dropping of the daylight in the West, The bough of cherries some officious fool Broke in the orchard for her, the white mule She rode with round the terrace—all and each 30 Would draw from her alike the approving speech, Or blush, at least. She thanked men—good! but thanked Somehow—I know not how—as if she ranked My gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name With anybody’s gift. Who’d stoop to blame 35 This sort of trifling? Even had you skill In speech—which I have not—to make your will Quite clear to such a one, and say, “Just this Or that in you disgusts me; here you miss, Or there exceed the mark”—and if she let 40 Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set Her wits to yours, forsooth, [7] and made excuse— E’en then would be some stooping; and I choose Never to stoop. Oh, sir, she smiled, no doubt, Whene’er I passed her; but who passed without 45 Much the same smile? This grew; I gave commands; Then all smiles stopped together. There she stands As if alive. Will’t please you rise? We’ll meet The company below, then. I repeat, The Count your master’s known munificence 50 Is ample warrant that no just pretense Of mine for dowry will be disallowed; [8] Though his fair daughter’s self, as I avowed At starting, is my object. Nay, we’ll go Together down, sir. Notice Neptune, [9] though, 55 Taming a sea-horse, thought a rarity, Which Claus of Innsbruck [10] cast in bronze for me!

The Duke’s speech reveals his character, and from his character emerges the theme of the poem. The Duke’s late wife displeased him, because he thinks she took joy in the simple pleasures of life at the expense of the attention and reverence she should have granted exclusively to him and to his “nine-hundred-years-old name.” His last Duchess chatted with Fra Pandolf, who painted her portrait; she loved the sunset; she loved the bough of cherries the gardener brought her; she loved riding around the estate on her white mule. The Duke believes, on the basis of no evidence, that his Duchess flirted with men. And so he “gave commands / Then all smiles stopped together.” He has her executed. The Duke reveals himself to be pathologically jealous, a product of his own deep-seated insecurities. And herein lies the main theme of the poem: the destructive power of jealousy arising from an arrogance that masks low self-esteem.

“My Last Duchess” is a dramatic monologue. It is a monologue in the sense that it consists of words spoken by one person. It is dramatic in the sense that another person is present, listening to the speaker’s words, which are shared with a wider audience, the poem’s readers. A dramatic monologue is, in a sense, a very short one-act play.

This is a regular verse dramatic monologue, in rhyming couplet iambic pentameter.

Figurative Language

The Duke comes across as a blunt, plain-spoken man, not one to use imagery or metaphor. The striking image of lines 18–19, noting that a painter would have trouble reproducing “the faint / Half-flush that dies along [the Duchess’s] throat,” is in the voice of the artist. It does foreshadow the Duchess’s fate.

The bronze sculpture of Neptune taming a sea horse, which the Duke points out to the Count’s ambassador before they rejoin the other guests, is a symbol of the control the Duke intends to exert upon his new bride. He has an ulterior motive in pointing out the statue.

Irony, as an element of literature, is a behaviour or an event which is contrary to readers’ or audience expectations. We say it is “ironic” when the Chief of Police is convicted of a crime. “My Last Duchess” rings with irony. The Duke condemns his wife’s behaviour but reveals her to be an innocent free spirit. He believes he is an honourable man, acting appropriately in the interest of preserving the integrity of his “nine-hundred-years-old name.” Readers soon understand the truth: the Duke is an insecure control freak and a murderer.

“My Last Duchess” was published in 1842, in Browning’s poetry collection Dramatic Lyrics . Browning was a student of the history, literature, and culture of Renaissance Italy, which is the poem’s setting, though he had not yet eloped with Elizabeth and settled with her in Italy.

Related Activities and Questions for Study and Discussion

- “My Last Duchess” was published in 1842 and is set in Italy in 1561. Consider how, if at all, the story it tells and the character of the Duke continue to be relevant today.

- Watch a dramatic reading of “My Last Duchess” by Robert Pennant Jones .

- Watch a dramatic reading of “My Last Duchess” by Ed Peed .

Text Attributions

- Biography: “Robert Browning” from poets.org © All Rights Reserved. Biography reprinted with the permission of the Academy of American Poets, 75 Maiden Lane, Suite 901, New York, NY, www.poets.org

- “My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning is free of known copyright restrictions in Canada.

Media Attributions

- Robert Browning by Cameron, 1865 © Julia Margaret Cameron is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Browning identifies the speaker, who delivers the lines which form the poem. He is Alfonso II, the Duke of Ferrara, a Province in northeast Italy. ↵

- In 1558, Ferrara married 14-year-old Lucrezia de Medici, daughter of the Grand Duke of another Italian province, Tuscany. She died in 1561. She may have died from tuberculosis, but Browning suggests in the poem she was murdered—poisoned or strangled—on the orders of her husband. ↵

- The Duke is based upon Alfonso II, fifth Duke of Ferrara (1533–97). In 1558, he married 14-year-old Lucrezia de’ Medici, who died in 1561 under suspicious circumstances. ↵

- Brother or Friar Pandolf, a fictitious painter from a monastic order. ↵

- Her shawl. ↵

- Perhaps a hint, a foreshadowing, of the Duchess’s death by strangulation. ↵

- We learn now that the listener is the ambassador for another Duke or, in this case, a Count, whose daughter Ferrara wishes to marry, as long as the dowry is sufficient. (In the interest of historical accuracy, it was more likely Tyrol’s niece whom Ferrara wished to marry.) ↵

- Roman sea god, here depicted as subduing a mythical beast, half horse, half fish. ↵

- An imaginary sculptor. The reference may be an indirect compliment to Ferdinand of Innsbruck, Count of Tyrol, whose daughter Alfonso married in 1565. ↵

Composition and Literature Copyright © 2019 by James Sexton and Derek Soles is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

“My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning

Introduction.

“My Last Duchess” is a beautiful poem written by Robert Browning and it also reveals the poet’s style of using dramatic monologue in writing his poems. The sixteenth century Italian background of the story adds richness to the theme, as Italy was the centre of arts. The attention of the readers has been taken away by the sentiments emerging from the story of the poem, ignoring the greatness of the portrait of the Duchess as a great piece of art. Though it is true that the portrait exposes the selfishness and the sexual greed of the Duke, the basic quality of the story and the poem is in the great skill of the poet in capturing the wicked nature of the Duke through the portrait of the Duchess. This brief paper takes a critical look at the poem.

The place is the palace of the Duke of Ferrara in the year 1564. The speaker in the poem is the Duke. He is talking to a representative of the Count of Tyrol, who has come to negotiate with the Duke about his next marriage to a daughter of another great family. This gentleman is shown the portrait of his last duchess and the way he narrates his relationship with her is the focus of the poem. The Duke says that she was looking as if she were alive. He tells his visitor that “That depth and passion of its earnest glance, /But to myself they turned” (Duchess). His emphasis on “myself” exposes his possessive nature. Like the inquisitive visitor the reader becomes anxious to know the Duke’s involvement in shaping the fate of the Duchess. “She had/ A heart – how shall I say? – too soon made glad”, says the Duke. What then went wrong is the obvious doubt hovering over the readers’ (or the visitor’s) mind. The Duke explains it: “her looks went everywhere”, something which, as her husband, the Duke could not bear. The character of he Duke becomes clear as the poem moves. He is possessive. He looks at his wife as a mere object, and not as person or individual.

The intensive emotion of the Duke comes to light as he narrates the event further. He says, “Oh sir, she smiled, no doubt, / Whene’er I passed her; but who passed without/ Much the same smile? “ The poet brings out the wicked nature of the Duke very slowly through his own words. She gives him her hearty smile whenever he passes, but he cannot bear to see her smile thrown to every passerby. These words of the Duke carry the existing nature of the Italian lovers in the sixteenth century. It is difficult for a modern woman to accept these words of the Duke. “This grew I gave commands”, tells the Duke. Though it is not made explicit what command he gave, it is obvious that he killed her. It is shocking to hear the Duke casually telling his visitor that “There she stands/ As if alive. Will ‘t please you rise?” At last the Duke takes him downstairs to negotiate for his next wife: “Nay, we’ll go/ Together down, sir”.

Browning’s superb ability in blending sex, violence, and art in this small poem is excellent. The way it is presented, using his usual style of dramatic monologue is what makes the poem unique. The pressure the poem puts on the reader to hate the Duke for his domineering nature gets nullified by his love of art. That he caught the most emotional moment of his last Duchess in the form of an artistic portrait with the help of a painter is what softens the readers’ dislike towards him. In other words, Browning has succeeded in taking a touching historical event to transform it into a beautiful piece of art. It is the captured moment in art which is lasting becomes the message of the poem.

The gripping quality of the poem has been highly praised by the scholars.

Browning, Robert. “My Last Duchess”.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2021, October 21). “My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning. https://studycorgi.com/my-last-duchess-by-robert-browning/

"“My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning." StudyCorgi , 21 Oct. 2021, studycorgi.com/my-last-duchess-by-robert-browning/.

StudyCorgi . (2021) '“My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning'. 21 October.

1. StudyCorgi . "“My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning." October 21, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/my-last-duchess-by-robert-browning/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "“My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning." October 21, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/my-last-duchess-by-robert-browning/.

StudyCorgi . 2021. "“My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning." October 21, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/my-last-duchess-by-robert-browning/.

This paper, ““My Last Duchess” by Robert Browning”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: November 11, 2023 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The Emotional and Psychological Condition of “My Last Duchess”’s the Duke and J. Alfred Prufrock Depicted through Poetic Devices

Related Papers

This study dive into the Victorian men's supremacy over the Victorian women in Robert Browning's poem, "My Last Duchess" (1842). Robert Browning is one of the major poets of the Victorian Era who attempted to renew the suppress Victorian atmosphere, via the panel of poetry, through which Victorian women lived desolated and unhappily. This study targets at proving that females were passively presented as slaves. In Victorian Age women were known as ignorant beings without any knowledge of the world outsides their homes. Rather they were desired to be innocent and simple. A. Orr remarks, "Intellect in a woman should conduce to her being loved, that it should even be comparatively with it, it must be thus subordinated to her womanhood." Women, if compared with men and at the same time symbolized the colonized nations. This poem as being one of Browning's volume Men and Women (1855), put-on brutality of Victorian men against women via Browning's taste of dramatic monologue that roundabout criticized the treatment of women as puppets and inferior.

Melisa Bayraktar

New criticism has had a vital place within the scope of critical studies and mainly literary criticism. Having specific characteristics which will be later on mentioned in this paper, new criticism analyzes the text from a broad perspective of view by focusing on various aspects. Just as new criticism can be applied to many poetic or dramatic works, one of the poems that can be studied with the application of new criticism can be regarded as T. S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” which is modernist poem and has the characteristics of new criticism. The aim of this paper is to discuss the poem “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” by T. S. Eliot from the perspective of new criticism and focusing on specific references.

Shahadat Hussein

T.S Eliot stands out as one of the chief exponents of modern literature. He delineates the anxiety and disorder of his age through his keen and realistic spectacles. Literature is considered to be the mirror of a society and Eliot is a master painter who skillfully sketches the true picture of modern era. His poems are not simply rhythmic verses but the archive of depressing history and events that profoundly molded the shapes and forms of his literary career. He depicts Prufrock as a prototypical modern hero in the poem, '' The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock'' and exposes the story of failure, frustration, uncertainty, conscious-inertia, self effacement, spiritual barrenness and utter hollowness of modern men and civilization through him. This paper attempts to substantiate Prufrock as a prototypical modern hero by analyzing images, allusions, and philosophical basis which have been closely ingrained in the very fabric of the poem.

Journal of History Culture and Art Research

SAMET GÜVEN

Alyssa MacKenzie

Alyssa’s essay points to a central issue in understanding modernism: its vexed relationship with romanticism, and its constant, nervous attempts to delineate the boundaries of that relationship, particularly by claiming for itself a radical newness. While, as she points out, much modernist critical writing stated an implacable opposition to some central romantic tenets, that purported opposition was always a lot less clear – and more interesting – in the poetry. Newness, as she suggests, is never pure, and is always most interesting when it is murky. -Dr. Leonard Diepeveen

sudipta sampriti

English Studies in Canada

Shyamal Bagchee

Lovely Majumdar

Khulna University Studies

Abdur Rahman Shahin

Usually an aesthete has a love for and understanding of art and beauty, and his aesthetic perception helps to develop ethical values that govern his behaviour. It is assumed that an aesthete will not show any cruelty to the beautiful aspects of life. But a heinous murder is observed in the artistic realm of the Duke in ‘My Last Duchess’ by Robert Browning. The Duchess is killed in a very cruel manner by the Duke because of her apparently indifferent attitude towards him. The aim of this article is to explore the nature of the triumph of cruelty that makes the appeal of aesthetic values dim.

RELATED PAPERS

European Journal of Human Genetics

Sonja Vernes

Archivos argentinos …

josette brawerman

Lubna Khalil

gaurav mittal

Surface Science

Obed Martinez

Journal of the Royal Society, Interface / the Royal Society

Thao Nguyen

Journal of Chemical Research

24.Nabila Adelia Ibrahim

Annals of Oncology

Jacobien M Kieffer

Ibrahim Hassounah

Applied Sciences

Sjoerd Duiker

azaini ibrahim

Jurnal Ilmu Kebidanan (Journal of Midwivery Science)

ENY Retna Ambarwati

Nursing Research and Practice

Abdul-Ganiyu Fuseini

Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry

Jyoti Shekhawat

Citrus Research Report

Glenn Wright

Gabriela Dudek

Ömer Halisdemir Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Dergisi

Stratigraphy and Geological Correlation

Svetlana Nikolaeva

Revista de investigación clínica; organo del Hospital de Enfermedades de la Nutrición

Sofia Paz Diaz Roman

Gustavo M . C . Mello

International Journal of Advances in Scientific Research and Engineering

Perfil de …

MAURICIO LOPEZ GONZALEZ

Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene

Matthew Little

Białostockie Studia Literaturoznawcze

Magda Nabialek

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

European Journal of English Language and Literature Studies (EJELLS)

- +44(0)1634 560711

- [email protected]

- 124 City Road, London, EC1V 2NX. UK

Psychoanalysis of Duke of Ferrara from ‘My Last Duchess’

() , , (), –

Robert Browning encapsulates the cosmos of a character within the microcosm of a moment. The dramatic monologue ‘My Last Duchess’ by the poet is a presentation of an egoistic, narcissistic and self centered duke. Throughout the poem there is a clear image of a psyche, overprotective, jealous and possessive personality who has executed his wife for his own narrow mentality. Browning has also portrayed the duke as someone extremely powerful who can change everything with a single command.

Keywords: Duke of Ferrara , Last Duchess’ , Psychoanalysis

This work by European American Journals is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 Unported License

Recent Publications

Manifestations of the utilization of the magical realism technique in john updike’s novel brazil, the stages and aims of a listening lesson, a systemic functional linguistic analysis of spousal conflictual language in a nigerian play, investigating the perceptions of saudi efl supervisors and teachers towards the effect of post-observation conferences on teachers’ professional development through assessing teachers’ reflection.

Author Guidelines Submit Papers Review Status

British Journal of Marketing Studies (BJMS) European Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance Research (EJAAFR) European Journal of Business and Innovation Research (EJBIR) European Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research (EJHTR) European Journal of Logistics, Purchasing and Supply Chain Management (EJLPSCM) Global Journal of Human Resource Management (GJHRM) International Journal of Business and Management Review (IJBMR) International Journal of Community and Cooperative Studies (IJCCS) International Journal of Management Technology (IJMT) International Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship Research (IJSBER)

British Journal of Education (BJE) European Journal of Training and Development Studies (EJTDS) International Journal of Education, Learning and Development (IJELD) International Journal of Interdisciplinary Research Methods (IJIRM) International Journal of Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods (IJQQRM) International Journal of Vocational and Technical Education Research (IJVTER)

British Journal of Earth Sciences Research (BJESR) British Journal of Environmental Sciences (BJES) European Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology (EJCSIT) European Journal of Material Sciences (EJMS) European Journal of Mechanical Engineering Research (EJMER) European Journal of Statistics and Probability (EJSP) Global Journal of Pure and Applied Chemistry Research (GJPACR) International Journal of Civil Engineering, Construction and Estate Management (IJCECEM) International Journal of Electrical and Electronics Engineering Studies (IJEEES) International Journal of Energy and Environmental Research (IJEER) International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology Studies (IJEATS) International Journal of Environment and Pollution Research (IJEPR) International Journal of Manufacturing, Material and Mechanical Engineering Research (IJMMMER) International Journal of Mathematics and Statistics Studies (IJMSS) International Journal of Network and Communication Research (IJNCR) International Research Journal of Natural Sciences (IRJNS) International Research Journal of Pure and Applied Physics (IRJPAP)

British Journal of English Linguistics (BJEL) European Journal of English Language and Literature Studies (EJELLS) International Journal of African Society, Cultures and Traditions (IJASCT) International Journal of Asian History, Culture and Tradition (IJAHCT) International Journal of Developing and Emerging Economies (IJDEE) International Journal of English Language and Linguistics Research (IJELLR) International Journal of English Language Teaching (IJELT)

International Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development Studies (IJAERDS) International Journal of Animal Health and Livestock Production Research (IJAHLPR) International Journal of Cancer, Clinical Inventions and Experimental Oncology (IJCCEO) International Journal of Cell, Animal Biology and Genetics (IJCABG) International Journal of Dentistry, Diabetes, Endocrinology and Oral Hygiene (IJDDEOH) International Journal of Ebola, AIDS, HIV and Infectious Diseases and Immunity (IJEAHII) International Journal of Entomology and Nematology Research (IJENR) International Journal of Environmental Chemistry and Ecotoxicology Research (IJECER) International Journal of Fisheries and Aquaculture Research (IJFAR) International Journal of Horticulture and Forestry Research (IJHFR) International Journal of Micro Biology, Genetics and Monocular Biology Research (IJMGMR) International Journal of Nursing, Midwife and Health Related Cases (IJNMH) International Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism Research (IJNMR) International Journal of Public Health, Pharmacy and Pharmacology (IJPHPP) International Journal of Weather, Climate Change and Conservation Research (IJWCCCR) International Journal Water Resources Management and Irrigation Engineering Research (IJWEMIER)

British Journal of Psychology Research (BJPR) European Journal of Agriculture and Forestry Research (EJAFR) European Journal of Biology and Medical Science Research (EJBMSR) European Journal of Botany, Plant Sciences and Phytology (EJBPSP) European Journal of Educational and Development Psychology (EJEDP) European Journal of Food Science and Technology (EJFST) Global Journal of Agricultural Research (GJAR) International Journal of Health and Psychology Research (IJHPR)

Global Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences (GJAHSS) Global Journal of Political Science and Administration (GJPSA) Global Journal of Politics and Law Research (GJPLR) International Journal of Development and Economic Sustainability (IJDES) International Journal of History and Philosophical Research (IJHPHR) International Journal of International Relations, Media and Mass Communication Studies (IJIRMMCS) International Journal of Music Studies (IJMS) International Journal of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and Essays (IJNGOE) International Journal of Physical and Human Geography (IJPHG) International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology Research (IJSAR)

International Journal of Biochemistry, Bioinformatics and Biotechnology Studies (IJBBBS) International Journal of Coal, Geology and Mining Research (IJCGMR) International Journal of Geography and Regional Planning Research (IJGRPR) International Journal of Library and Information Science Studies (IJLISS) International Journal of Petroleum and Gas Engineering Research (IJPGER) International Journal of Petroleum and Gas Exploration Management (IJPGEM) International Journal of Physical Sciences Research (IJPSR) International Journal of Scientific Research in Essays and Case Studies (IJSRECS)

Don't miss any Call For Paper update from EA Journals

Fill up the form below and get notified everytime we call for new submissions for our journals.

--> My Last Duchess Essay

Introduction.

Browning’s “My Last Duchess” is a poem about a Duke and his wife. The duchess has an outstanding personality that threatens the insecure duke. The Duke has his wife killed because he is not pleased with her, and he is afraid he will not be able to control her.

Suppression of women and male dominance

The relationship between the Duke and the Duchess illustrates how men are obsessed with dominating and controlling women. The poem shows that the power to control women is in the hands of men. The duke feels he had taken back his control over the duchess once he killed her, but the duke does not realize that he only portrays his imminent weakness. Browning’s poem shows that, men silence women so that only their point of view is heard, thus there is no competition or opposition for them. Men such as the Duke become dependent on women’s silence.

Because of his insecurity, the Duke feels he has more control over the Duchess because only a portrait of her is hung on the wall, and not her real self. “Man-made objects displace divinely constructed ones in terms of importance” (Mitchell 74). The manmade portrait puts out of place the beautifully created human being in terms of importance. This shows men in society do not respect life; men are ready to end the life of another human being just so that they may gain power and control.

Though men played an enormous role in suppressing women, women are also to blame for their bondage. In an attempt to please men and society, women do not seek to find their identity. They seem to enjoy the fact that, men are taking control over them. The duke speaks of the duchess and says, “She had a heart, how shall I say? Too soon made glad, too easily impressed” (Browning lines 21-23). The Duke refers to the Duchess as someone who could not differentiate between an ordinary event and an event that should evoke joy. The Duke’s statement symbolizes the child-like behavior of women which makes it easy for men to take advantage of their innocence. Browning’s poem, “My Last Duchess” shows women that there are consequences of behaving child-like and conforming to men’s will.

The Duke wanted to control the Duchess in every way when she was still alive. He wanted to ensure that her smiles and laughter were only directed to him. The Duchess’s sociable personality threatened the Duke and made him feel insecure. The Duke says that he was “disgust[ed]” by the Duchess’s interest in anybody else other than himself (Browning 39). The Duke was so insecure that he used his power to control the Duchess so that she could not see other people. He did not want the Duchess’s warmth to be directed to anyone else. Control over what the Duchess was exposed to was one of the Duke’s vital role. After the Duchess died, the Duke feels that he has recovered complete control over her. The Duke seems to be happier when the Duchess dies. This shows that he has a weak personality and is threatened by the existence of the Duchess.

The Duke says that,” her looks went everywhere” (Browning line 24). Since only her portrait remains now, the Duke can open and close the curtain whenever he wants, and he makes sure that only he can access that curtain. This way, he is sure that her looks will go nowhere, and she will always be there for him. “None puts by the curtain I have drawn for you, but I” (Browning line 9). This way the Duke has complete control over the Duchess and only he enjoy her smile on the painting.

The Duke was uncomfortable with the fact that the Duchess did not entirely depend on him. The Duchess treated everyone with respect, and this did not please the Duke. The Duke felt that the Duchess should give him her undivided attention and should place him above everything because of his status. He states that, “I know not how, as if she ranked my gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name with anybody’s gift” (Browning lines 32-34). The Duke feels that Duchess does not consider being married to him as the most valuable thing in her life. According to Dukes statement the Duchess is supposed to worship him like a god simply because he is the Duke. This is how society expects women to act as a commitment to their marital life.

The Duke felt that the Duchess no longer smiled at him. The Duke was irritated because he was unable to control the Duchess’s smile. “I gave commands, then all smiles stopped together” (Browning line 45). The Duchess smile was a symbol of her connection to the outside world, outside her marriage. The Duchess was able to use her smile to bond and communicate with others. The Duke was not happy because the Duchess no longer reserved her “smiles” and attention for him. “My Last Duchess” reveals that women are expected to reserve all their lives and attention for their husbands.

Women will continue to be subjected to the urge of men until they stop worshiping them. The Duchess did not worship the Duke, for this reason the Duke had her murdered. The Duchess viewed her husband as a man and not a god. The Duke killing his wife is a threat to all women in society. He states that, if his future Duchess does not flatter him as he expects, she will lose what power she will achieve by getting married to him. Even after having his wife killed, the Duke does not make any attempt to conceal his possessiveness and jealousy that led to this murder. This is a threat to all future Duchesses and shows that men are not remorseful for subjecting women to suppression.

Related essays

- Mulatto Girl Beauty

- London’s Greatest Landmarks

- The Little Black Dress

Authorization

Our Specialization

- Plagiarism-Free Papers

- Free revisions

- Free outline

- Free bibliography page

- Free formatting

- Free title page

- 24/7/365 customer support

- 300 words per page

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Poems — My Last Duchess

Essays on My Last Duchess

The power of voice in "my last duchess", comparative analysis of the poems ozymandias by percy shelly and my last duchess by robert browning, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online