Essays About Depression: Top 8 Examples Plus Prompts

Many people deal with mental health issues throughout their lives; if you are writing essays about depression, you can read essay examples to get started.

An occasional feeling of sadness is something that everyone experiences from time to time. Still, a persistent loss of interest, depressed mood, changes in energy levels, and sleeping problems can indicate mental illness. Thankfully, antidepressant medications, therapy, and other types of treatment can be largely helpful for people living with depression.

People suffering from depression or other mood disorders must work closely with a mental health professional to get the support they need to recover. While family members and other loved ones can help move forward after a depressive episode, it’s also important that people who have suffered from major depressive disorder work with a medical professional to get treatment for both the mental and physical problems that can accompany depression.

If you are writing an essay about depression, here are 8 essay examples to help you write an insightful essay. For help with your essays, check out our round-up of the best essay checkers .

- 1. My Best Friend Saved Me When I Attempted Suicide, But I Didn’t Save Her by Drusilla Moorhouse

- 2. How can I complain? by James Blake

- 3. What it’s like living with depression: A personal essay by Nadine Dirks

- 4. I Have Depression, and I’m Proof that You Never Know the Battle Someone is Waging Inside by Jac Gochoco

- 5. Essay: How I Survived Depression by Cameron Stout

- 6. I Can’t Get Out of My Sweat Pants: An Essay on Depression by Marisa McPeck-Stringham

- 7. This is what depression feels like by Courtenay Harris Bond

8. Opening Up About My Struggle with Recurring Depression by Nora Super

1. what is depression, 2. how is depression diagnosed, 3. causes of depression, 4. different types of depression, 5. who is at risk of depression, 6. can social media cause depression, 7. can anyone experience depression, the final word on essays about depression, is depression common, what are the most effective treatments for depression, top 8 examples, 1. my best friend saved me when i attempted suicide, but i didn’t save her by drusilla moorhouse.

“Just three months earlier, I had been a patient in another medical facility: a mental hospital. My best friend, Denise, had killed herself on Christmas, and days after the funeral, I told my mom that I wanted to die. I couldn’t forgive myself for the role I’d played in Denise’s death: Not only did I fail to save her, but I’m fairly certain I gave her the idea.”

Moorhouse makes painstaking personal confessions throughout this essay on depression, taking the reader along on the roller coaster of ups and downs that come with suicide attempts, dealing with the death of a loved one, and the difficulty of making it through major depressive disorder.

2. How can I complain? by James Blake

“I wanted people to know how I felt, but I didn’t have the vocabulary to tell them. I have gone into a bit of detail here not to make anyone feel sorry for me but to show how a privileged, relatively rich-and-famous-enough-for-zero-pity white man could become depressed against all societal expectations and allowances. If I can be writing this, clearly it isn’t only oppression that causes depression; for me it was largely repression.”

Musician James Blake shares his experience with depression and talks about his struggles with trying to grow up while dealing with existential crises just as he began to hit the peak of his fame. Blake talks about how he experienced guilt and shame around the idea that he had it all on the outside—and so many people deal with issues that he felt were larger than his.

3. What it’s like living with depression: A personal essay by Nadine Dirks

“In my early adulthood, I started to feel withdrawn, down, unmotivated, and constantly sad. What initially seemed like an off-day turned into weeks of painful feelings that seemed they would never let up. It was difficult to enjoy life with other people my age. Depression made typical, everyday tasks—like brushing my teeth—seem monumental. It felt like an invisible chain, keeping me in bed.”

Dirks shares her experience with depression and the struggle she faced to find treatment for mental health issues as a Black woman. Dirks discusses how even though she knew something about her mental health wasn’t quite right, she still struggled to get the diagnosis she needed to move forward and receive proper medical and psychological care.

4. I Have Depression, and I’m Proof that You Never Know the Battle Someone is Waging Inside by Jac Gochoco

“A few years later, at the age of 20, my smile had fallen, and I had given up. The thought of waking up the next morning was too much for me to handle. I was no longer anxious or sad; instead, I felt numb, and that’s when things took a turn for the worse. I called my dad, who lived across the country, and for the first time in my life, I told him everything. It was too late, though. I was not calling for help. I was calling to say goodbye.”

Gochoco describes the war that so many people with depression go through—trying to put on a brave face and a positive public persona while battling demons on the inside. The Olympic weightlifting coach and yoga instructor now work to share the importance of mental health with others.

5. Essay: How I Survived Depression by Cameron Stout

“In 1993, I saw a psychiatrist who prescribed an antidepressant. Within two months, the medication slowly gained traction. As the gray sludge of sadness and apathy washed away, I emerged from a spiral of impending tragedy. I helped raise two wonderful children, built a successful securities-litigation practice, and became an accomplished cyclist. I began to take my mental wellness for granted. “

Princeton alum Cameron Stout shared his experience with depression with his fellow Tigers in Princeton’s alumni magazine, proving that even the most brilliant and successful among us can be rendered powerless by a chemical imbalance. Stout shares his experience with treatment and how working with mental health professionals helped him to come out on the other side of depression.

6. I Can’t Get Out of My Sweat Pants: An Essay on Depression by Marisa McPeck-Stringham

“Sometimes, when the depression got really bad in junior high, I would come straight home from school and change into my pajamas. My dad caught on, and he said something to me at dinner time about being in my pajamas several days in a row way before bedtime. I learned it was better not to change into my pajamas until bedtime. People who are depressed like to hide their problematic behaviors because they are so ashamed of the way they feel. I was very ashamed and yet I didn’t have the words or life experience to voice what I was going through.”

McPeck-Stringham discusses her experience with depression and an eating disorder at a young age; both brought on by struggles to adjust to major life changes. The author experienced depression again in her adult life, and thankfully, she was able to fight through the illness using tried-and-true methods until she regained her mental health.

7. This is what depression feels like by Courtenay Harris Bond

“The smallest tasks seem insurmountable: paying a cell phone bill, lining up a household repair. Sometimes just taking a shower or arranging a play date feels like more than I can manage. My children’s squabbles make me want to scratch the walls. I want to claw out of my own skin. I feel like the light at the end of the tunnel is a solitary candle about to blow out at any moment. At the same time, I feel like the pain will never end.”

Bond does an excellent job of helping readers understand just how difficult depression can be, even for people who have never been through the difficulty of mental illness. Bond states that no matter what people believe the cause to be—chemical imbalance, childhood issues, a combination of the two—depression can make it nearly impossible to function.

“Once again, I spiraled downward. I couldn’t get out of bed. I couldn’t work. I had thoughts of harming myself. This time, my husband urged me to start ECT much sooner in the cycle, and once again, it worked. Within a matter of weeks I was back at work, pretending nothing had happened. I kept pushing myself harder to show everyone that I was “normal.” I thought I had a pattern: I would function at a high level for many years, and then my depression would be triggered by a significant event. I thought I’d be healthy for another ten years.”

Super shares her experience with electroconvulsive therapy and how her depression recurred with a major life event despite several years of solid mental health. Thankfully, Super was able to recognize her symptoms and get help sooner rather than later.

7 Writing Prompts on Essays About Depression

When writing essays on depression, it can be challenging to think of essay ideas and questions. Here are six essay topics about depression that you can use in your essay.

Depression can be difficult to define and understand. Discuss the definition of depression, and delve into the signs, symptoms, and possible causes of this mental illness. Depression can result from trauma or personal circumstances, but it can also be a health condition due to genetics. In your essay, look at how depression can be spotted and how it can affect your day-to-day life.

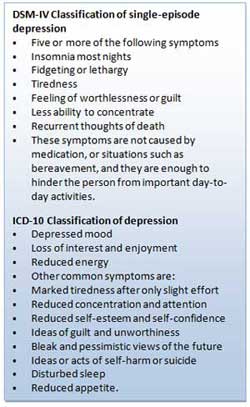

Depression diagnosis can be complicated; this essay topic will be interesting as you can look at the different aspects considered in a diagnosis. While a certain lab test can be conducted, depression can also be diagnosed by a psychiatrist. Research the different ways depression can be diagnosed and discuss the benefits of receiving a diagnosis in this essay.

There are many possible causes of depression; this essay discusses how depression can occur. Possible causes of depression can include trauma, grief, anxiety disorders, and some physical health conditions. Look at each cause and discuss how they can manifest as depression.

There are many different types of depression. This essay topic will investigate each type of depression and its symptoms and causes. Depression symptoms can vary in severity, depending on what is causing it. For example, depression can be linked to medical conditions such as bipolar disorder. This is a different type of depression than depression caused by grief. Discuss the details of the different types of depression and draw comparisons and similarities between them.

Certain genetic traits, socio-economic circumstances, or age can make people more prone to experiencing symptoms of depression. Depression is becoming more and more common amongst young adults and teenagers. Discuss the different groups at risk of experiencing depression and how their circumstances contribute to this risk.

Social media poses many challenges to today’s youth, such as unrealistic beauty standards, cyber-bullying, and only seeing the “highlights” of someone’s life. Can social media cause depression in teens? Delve into the negative impacts of social media when writing this essay. You could compare the positive and negative sides of social media and discuss whether social media causes mental health issues amongst young adults and teenagers.

This essay question poses the question, “can anyone experience depression?” Although those in lower-income households may be prone to experiencing depression, can the rich and famous also experience depression? This essay discusses whether the privileged and wealthy can experience their possible causes. This is a great argumentative essay topic, discuss both sides of this question and draw a conclusion with your final thoughts.

When writing about depression, it is important to study examples of essays to make a compelling essay. You can also use your own research by conducting interviews or pulling information from other sources. As this is a sensitive topic, it is important to approach it with care; you can also write about your own experiences with mental health issues.

Tip: If writing an essay sounds like a lot of work, simplify it. Write a simple 5 paragraph essay instead.

FAQs On Essays About Depression

According to the World Health Organization, about 5% of people under 60 live with depression. The rate is slightly higher—around 6%—for people over 60. Depression can strike at any age, and it’s important that people who are experiencing symptoms of depression receive treatment, no matter their age.

Suppose you’re living with depression or are experiencing some of the symptoms of depression. In that case, it’s important to work closely with your doctor or another healthcare professional to develop a treatment plan that works for you. A combination of antidepressant medication and cognitive behavioral therapy is a good fit for many people, but this isn’t necessarily the case for everyone who suffers from depression. Be sure to check in with your doctor regularly to ensure that you’re making progress toward improving your mental health.

If you’re still stuck, check out our general resource of essay writing topics .

Amanda has an M.S.Ed degree from the University of Pennsylvania in School and Mental Health Counseling and is a National Academy of Sports Medicine Certified Personal Trainer. She has experience writing magazine articles, newspaper articles, SEO-friendly web copy, and blog posts.

View all posts

- Essay Samples

- College Essay

- Writing Tools

- Writing guide

↑ Return to College Essay

Definition Essay – Defining depression

Depression is a mental illness under the psychological sector “Clinical psychology.” It has a few facets to it, and has numerous causes. It is also known as a mental state that most people undergo at some point in their lives. However, there are some people that get chronic depression, or forms of depression that need intervention to help bring them out of it.

A low mood is not depression

Some people think that because they are in a low mood they are depressed. Women seem to use the word depression as often as they use the toilet. Depression is a state of mind whereby there appears no future, past or hope for a person. The person feels nothing but a void and will not envision a happy future or pleasant present without provocation. It is a default position that a person takes on a conscious level that bores its way into the subconscious, which creates a negative feedback loop.

Bi-Polar (Manic Depressive) has a deeper root

People may go through a tough time and become temporarily depressed. In fact, depression is one of the five stages of the Kublar Ross grieving process, and yet a tough time, even a very bad time, does not create bi-polar disorder. This is because the condition has a deeper root that is either nestled in psychology, brought on by biochemistry, brought on by something physical, or all three.

People with Bi-polar depression go through psychological cycles that to the outside observer appear to be polar opposites. A sufferer will undergo periods of extreme sadness and hopelessness where he or she only sees a void in their past, present and future. The sufferer is often unwilling and unable to do anything productive and will feel low and horrible most of the time.

The polar opposite also occurs where the person experiences great degrees of optimism and even excitement and passivity. The person is often highly motivated and pushes him or herself to do things that they wouldn’t do otherwise. For example, if that person has been putting off re-paving the patio, then he or she may start right away by taking up the paving slabs and putting them on the drive to be collected. Many times, people undergoing such positive highs are often stricken with a negative low and their half-completed tasks remain uncompleted.

Causes can be environmental, biological, physical, genetic and psychological

Depression is not a mood, but it has as many causes as a mood. For example, if you were to define yourself as happy, which is a mood, it could be due to your environment, a drug, through a physical sensation, a psychological reason, and may even be because there is a gene that makes people predisposed to happiness. Depression works in a very similar way, except that the state of being depressed is far more serious and can be very difficult to get out of. Conclusion

Depression has a number of causes and is more than just a low or a bad mood. It can be easy to get into, though it is sometimes thrust upon people without their prior knowledge, expectation or understanding. Furthermore, it is sometimes easy to get out of depression, but many ex-sufferers have trouble “staying” un-depressed.

Follow Us on Social Media

Get more free essays

Send via email

Most useful resources for students:.

- Free Essays Download

- Writing Tools List

- Proofreading Services

- Universities Rating

Contributors Bio

Find more useful services for students

Free plagiarism check, professional editing, online tutoring, free grammar check.

Depression: A Cognitive Perspective Essay

Depression is one of the mood disorders and is a distorted mood or negative mood caused by complex imbalance in the activity in the brain or external circumstances. Therefore, those factors causing the aforementioned imbalance or negative mood can be considered as causing depression or contributing to it. It is not yet clear according to Barlow & Durand (2005) because depression has been evidenced even in 3-month old babies. However, 60% to 80% of the causes of depression can be attributed to psychological experiences according to Barlow & Durand (2005), who also adds that the cases are unique to individuals. According to the author, the major reasons that could be blamed for psychological disorders are stress and trauma resulting from life events such as loss of a job, having a child, getting divorced, and starting a career, but more importantly, individual reactions and the settings play a very important role in determining the developments. For example, some individuals sees loosing a job as opportunity to working out their hobbies, while others may be depressed because they already have a family to care for after loosing a job.

Depression is a negative emotional state arising from, usually, subconscious thoughts pulled out of the “store of thoughts” to explain circumstances. Perhaps, the implication can be well understood in considering that the cognitive therapy modules are designed to help individuals change the ways one think. This is a systematic process because, for example, negative thoughts may have been repeated overtime and for long, thus becoming automatic thoughts applied by people to respond to most conditions and circumstances or happenings in life. Maladaptive and erroneous processing of information causes depression. The individuals have faulty assumptions and beliefs arising from the biased thinking. Family experiences which are traumatic and historic may cause people to develop negative memories and cognition which cause sadness, depression or anxiety (Sarasola Mental Health Institute, 2008).

Negative core beliefs, low self-esteem and family history have been indicated as causatives of depressions. Family history has been connected to the changing in the structure of the brain and its functioning. Negative core beliefs are implicated in causing depression in that it influence thoughts, which in turn generate negative emotional states.

Cognitive approach to depression focuses on the self-repressive critical self-evaluations, pessimism, and unrealistic expectations and perceptions. These do not only establish depression but also sustain it. Cognitive approach to treating depression helps individuals change these behaviors and feelings, develop more positive assessment and develop positive life goals. Defense mechanisms expresses unconscious id whose impulses’ expression in behavior cause anxiety. When an individual represses conflict issues or has a decay of memory, unconscious thoughts (which are any mental contents and functions that are out of awareness) may emanate, according (Kihlstrom, Barnhardt & Tetaryn, 1992; Buci, 1997; qtd. in Blatt & Auerbach, 2000). Cognitive elements such as desires, personal evaluations, fears, attitudes, and expectations have been linked to human behavior and each affect the other. Therefore, cognitive approach to depression may link with behavioral explanations as well.

Historically, depression has been indicated to occur as a response to a perceived loss or imaginary loss and self-critic of ego according to Freud (1917). Cognitive approach to depression explain the causes of maladaptive cognitions as variety of life experiences such as distressful life events, family experiences, lack of proper social learning and shortage of adaptive learning.

When a person is depressed, he has a tendency of taking responsibility for all that goes wrong while he gives others credit for positive-appearing things. According to psychologists, the result of self-criticism in depressed persons may be a sense of failure, low self-esteem and criticism. Negative self-evaluation in Mary is well evident in her comments that she can’t find anyone who love her and has nothing special to offer. Negative self-evaluation may be as a result of perceived loss and family experiences that make one feel inadequate.

Another cognitive aspect of depression is identification of skill deficits where, in addition to identifying the shortage of skills, the person assumes that he or she cannot learn to act differently or achieve better results. Shortage of skills may be right, and this makes the person under depression assume that other deficits are real too. Therefore, the cause of depression on this line may be a real shortage of skills, accompanied by negative self-evaluation because the individual is more likely to see the negative aspects or the skills he lacks than those that he has. In the case study, Mary cannot see the achievement of being a graduate but recognizes that the award is without honors, he is not beautiful but was only referred to as being pretty. Causes of depression attacking an individual in this way have an influence on individuals’ values and how they feel about themselves. Life experiences and traumatic incidences may also make the individual to identify mostly with the negative aspects in his life than the positive aspects, or feel inadequate.

Unrealistic expectations cause individuals to always focus on the negative aspects of life even when the overall experience was good. In other words, these individuals focus almost always on the negative events, conditions, practices or thoughts. They evaluate incidences on an overall, based on the happening of a few bad incidences or only one incidence. These individuals may always want and expect perfection, and hence the frustration after failure, because life ahead of them may be full of imperfect situations. The individuals fail to consider or appreciate the fact that wrong things, incidences, practices and results can be repaired, corrected, started again or mended and that mostly in most of life incidences on an average scale, only a little things may be amiss. Negative self-talks may be a way of immobilizing someone to solve problems, and may result in depression. Although self-talk is normal, sometimes healthy, a process of thinking and helpful if positive, negative self-talk may impact negatively to our ability to solve problems arising and see ourselves as incapable. Negative automatic thoughts can also influence someone’s perspective of the surrounding, the people he meets with and how they relate to him. Negative automatic thoughts, like positive ones may not offer a chance for an analysis of the encountered situation or incidence, and goes ahead to judge them as presumed. If negative, automatic thoughts may cause individuals to reach a quick analysis of a situation such as people hate them or dislike them, for example when people smile at them talking, a quick negative thought would estimate that they are laughing at them rather than for example, being impressed by them. The impact of quick negative thoughts may be low self-evaluation and low attitude which have been linked to depression.

Because every person needs to cope to the world not only through physical encounter but also assumptions, perceptions and judgment, cognitive distortion manifesting through wrong or false evaluation of situations may cause depression or worsen the state of a person under depression. People may carry false assumptions about how people think about them, may over-generalize simple mistakes, or carry irrational ideas about incidences or situations (Donald, 2003).

According to Blatt and Auerbach (2000), dynamic unconsciousness which have intentionally been excluded from awareness by the individual, may manifest through unusual circumstances like dream formation, experimental primation, therapeutic process and free association. As individuals conflict with their personality issues, they may adopt defense mechanisms that repress dynamic unconsciousness. The dynamic unconscious mental contents so excluded include certain wishes or feelings that contradict with his or her other wishes or feelings. The drive of the id is suppressed by the superego (personality component holding all internalized moral standards and ideals) which is implanted in individuals by their parents. Shortly after birth, ego (personality component responsible for dealing with reality) is developed. Some individual states such as anxiety would develop when the id or the superego challenges the conscious ego. Freud’s conceptualization of development of defense mechanisms that are applied to ward off anxiety may be implicated in the theory of depression, specifically because those individuals who are depressed may show denial objective reality that is apparent to others even through erroneous interpretation of events, conditions, or circumstances. For example, loss of an immediate family member may cause people to develop most of the symptoms of major depressive episode: denial, anxiety an emotional numbness (Barlow & Durand, 2005). When severe grieving proceeds for more than a year, there is low likelihood of recovery without treatment. In addition, repression-which is the blocking of disturbing wishes, thoughts or experiences from conscious awareness-may be present in the depression status. Under such circumstance, depression may occur because the grieving process was ineffective.

- Allen Josiah. (2003). An Overview of Beck’s Cognitive Theory of Depression in Contemporary Literature . Web.

- Barlow, D.H. & Durand, V.M. (2005). Abnormal Psychology: An Integrative Approach. (5th Edition). Australia: Wadsworth

- Blatt Sidney and Auerbach John. (2000). Psychoanalytic Models of the Mind and their Contributions to Personality Research. European Journal of Personality. 14: 429-447

- Bucci W.1997. Psychoanalysis and Cognitive Science: A Multiple Code Theory. Guilford: New York

- Donald Franklin. Cognitive therapy for depression. Web.

- Gonca, S., & Savasir, I. (2001). The relationship between interpersonal schemas and depressive symptomatology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 48, 359-364

- Freud S.(1957). The Unconscious, Strachey J. (ed.), orig.workpubl.1915, Vol.14. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud . Hogarth: London; 166204

- Kihlstrom JF., Barnhardt TM., Tetaryn DJ.1992.The psychological unconscious: found, lost, and regained. American Psychologist 47:788791.

- Moilanen, D. L. (1993). Depressive information processing among nonclinic, nonreferred college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 40, 340-347

- Sarasola Mental Health Institute. (2008). Cognitive Therapy is Effective in Treating Depression and Anxiety.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, May 13). Depression: A Cognitive Perspective. https://ivypanda.com/essays/depression-and-causes/

"Depression: A Cognitive Perspective." IvyPanda , 13 May 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/depression-and-causes/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Depression: A Cognitive Perspective'. 13 May.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Depression: A Cognitive Perspective." May 13, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/depression-and-causes/.

1. IvyPanda . "Depression: A Cognitive Perspective." May 13, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/depression-and-causes/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Depression: A Cognitive Perspective." May 13, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/depression-and-causes/.

- Self-Evaluation of Students' Achievements

- Leadership: Self-Evaluation and Comparison

- Self-Evaluation of Understanding Knowledge Development in Nursing

- Judge and Bono on Relationships of Core Self-Evaluation Traits to Job Satisfaction and Performance

- The Contraceptives Project Self-Evaluation

- Personal Cultural Awareness in Management: Self-Evaluation

- Zara Company and the Automatic ID System

- Distinction between automatic and controlled processing

- Social Psychology: Cognitive Dissonance

- Reducing Cognitive Dissonance by Restoring Positive Self-Evaluations

- Posttraumatic Stress Symptom Disease

- Analyzing Psychological Disorders: Schizophrenia

- Various Limitations Upon Clear Thinking in the Halpern “Thought and Knowledge”

- Depression, Substance Abuse and Suicide in Elderly

- Psychological Disorder Analysis: A Case of Bipolar Disorder

Psychological Theories of Depression

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Depression is a mood disorder that prevents individuals from leading a normal life at work, socially, or within their family. Seligman (1973) referred to depression as the ‘common cold’ of psychiatry because of its frequency of diagnosis.

Depending on how data are gathered and how diagnoses are made, as many as 27% of some population groups may be suffering from depression at any one time (NIMH, 2001; data for older adults).

Behaviorist Theory

Behaviorism emphasizes the importance of the environment in shaping behavior. The focus is on observable behavior and the conditions through which individuals” learn behavior, namely classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and social learning theory.

Therefore, depression is the result of a person’s interaction with their environment.

For example, classical conditioning proposes depression is learned through associating certain stimuli with negative emotional states. Social learning theory states behavior is learned through observation, imitation, and reinforcement.

Operant Conditioning

Operant conditioning states that depression is caused by the removal of positive reinforcement from the environment (Lewinsohn, 1974). Certain events, such as losing your job, induce depression because they reduce positive reinforcement from others (e.g., being around people who like you).

Depressed people usually become much less socially active. In addition, depression can also be caused by inadvertent reinforcement of depressed behavior by others.

For example, when a loved one is lost, an important source of positive reinforcement has lost as well. This leads to inactivity. The main source of reinforcement is now the sympathy and attention of friends and relatives.

However, this tends to reinforce maladaptive behavior, i.e., weeping, complaining, and talking of suicide. This eventually alienates even close friends leading to even less reinforcement and increasing social isolation and unhappiness. In other words, depression is a vicious cycle in which the person is driven further and further down.

Also, if the person lacks social skills or has a very rigid personality structure, they may find it difficult to make the adjustments needed to look for new and alternative sources of reinforcement (Lewinsohn, 1974). So they get locked into a negative downward spiral.

Critical Evaluation

Behavioral/learning theories make sense in terms of reactive depression, where there is a clearly identifiable cause of depression. However, one of the biggest problems for the theory is that of endogenous depression. This is depression that has no apparent cause (i.e., nothing bad has happened to the person).

An additional problem of the behaviorist approach is that it fails to consider cognitions (thoughts) influence on mood.

Psychodynamic Theory

During the 1960s, psychodynamic theories dominated psychology and psychiatry. Depression was understood in terms of the following:

- inwardly directed anger (Freud, 1917),

- introjection of love object loss,

- severe super-ego demands (Freud, 1917),

- excessive narcissistic , oral, and/or anal personality needs (Chodoff, 1972),

- loss of self-esteem (Bibring, 1953; Fenichel, 1968), and

- deprivation in the mother-child relationship during the first year (Kleine, 1934).

Freud’s psychoanalytic theory is an example of the psychodynamic approach . Freud (1917) proposed that many cases of depression were due to biological factors.

However, Freud also argued that some cases of depression could be linked to loss or rejection by a parent. Depression is like grief in that it often occurs as a reaction to the loss of an important relationship.

However, there is an important difference because depressed people regard themselves as worthless. What happens is that the individual identifies with the lost person so that repressed anger towards the lost person is directed inwards towards the self. The inner-directed anger reduces the individual’s self-esteem and makes him/her vulnerable to experiencing depression in the future.

Freud distinguished between actual losses (e.g., the death of a loved one) and symbolic losses (e.g., the loss of a job). Both kinds of losses can produce depression by causing the individual to re-experience childhood episodes when they experience loss of affection from some significant person (e.g., a parent).

Later, Freud modified his theory stating that the tendency to internalize lost objects is normal and that depression is simply due to an excessively severe super-ego. Thus, the depressive phase occurs when the individual’s super-ego or conscience is dominant. In contrast, the manic phase occurs when the individual’s ego or rational mind asserts itself, and s/he feels control.

In order to avoid loss turning into depression, the individual needs to engage in a period of mourning work, during which s/he recalls memories of the lost one.

This allows the individual to separate himself/herself from the lost person and reduce inner-directed anger. However, individuals very dependent on others for their sense of self-esteem may be unable to do this and so remain extremely depressed.

Psychoanalytic theories of depression have had a profound impact on contemporary theories of depression.

For example, Beck’s (1983) model of depression was influenced by psychoanalytic ideas such as the loss of self-esteem (re: Beck’s negative view of self), object loss (re: the importance of loss events), external narcissistic deprivation (re: hypersensitivity to loss of social resources) and oral personality (re: sociotropic personality).

However, although highly influential, psychoanalytic theories are difficult to test scientifically. For example, its central features cannot be operationally defined with sufficient precision to allow empirical investigation. Mendelson (1990) concluded his review of psychoanalytic theories of depression by stating:

“A striking feature of the impressionistic pictures of depression painted by many writers is that they have the flavor of art rather than of science and may well represent profound personal intuitions as much as they depict they raw clinical data” (p. 31).

Another criticism concerns the psychanalytic emphasis on the unconscious, intrapsychic processes, and early childhood experience as being limiting in that they cause clinicians to overlook additional aspects of depression. For example, conscious negative self-verbalization (Beck, 1967) or ongoing distressing life events (Brown & Harris, 1978).

Cognitive Explanation of Depression

This approach focuses on people’s beliefs rather than their behavior. Depression results from systematic negative bias in thinking processes.

Emotional, behavioral (and possibly physical) symptoms result from cognitive abnormality. This means that depressed patients think differently from clinically normal people. The cognitive approach also assumes changes in thinking precede (i.e., come before) the onset of a depressed mood.

Beck’s (1967) Theory

One major cognitive theorist is Aaron Beck. He studied people suffering from depression and found that they appraised events in a negative way.

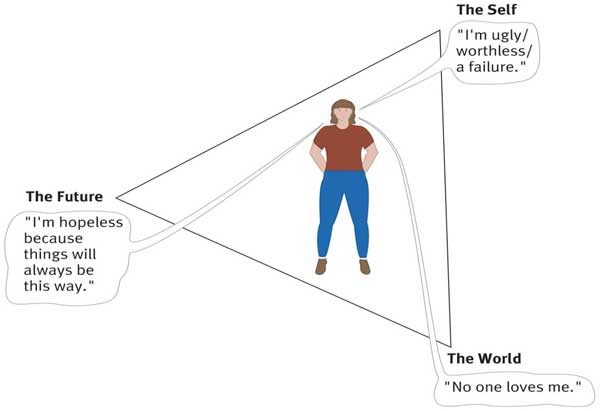

Beck (1967) identified three mechanisms that he thought were responsible for depression:

The cognitive triad (of negative automatic thinking) Negative self schemas Errors in Logic (i.e. faulty information processing)

The cognitive triad is three forms of negative (i.e., helpless and critical) thinking that are typical of individuals with depression: namely, negative thoughts about the self, the world, and the future. These thoughts tended to be automatic in depressed people as they occurred spontaneously.

For example, depressed individuals tend to view themselves as helpless, worthless, and inadequate. They interpret events in the world in an unrealistically negative and defeatist way, and they see the world as posing obstacles that can’t be handled.

Finally, they see the future as totally hopeless because their worthlessness will prevent their situation from improving.

As these three components interact, they interfere with normal cognitive processing, leading to impairments in perception, memory, and problem-solving, with the person becoming obsessed with negative thoughts.

Beck believed that depression-prone individuals develop a negative self-schema . They possess a set of beliefs and expectations about themselves that are essentially negative and pessimistic. Beck claimed that negative schemas might be acquired in childhood as a result of a traumatic event. Experiences that might contribute to negative schemas include:

- Death of a parent or sibling.

- Parental rejection, criticism, overprotection, neglect, or abuse.

- Bullying at school or exclusion from a peer group.

However, a negative self-schema predisposes the individual to depression, and therefore someone who has acquired a cognitive triad will not necessarily develop depression.

Some kind of stressful life event is required to activate this negative schema later in life. Once the negative schema is activated, a number of illogical thoughts or cognitive biases seem to dominate thinking .

People with negative self-schemas become prone to making logical errors in their thinking, and they tend to focus selectively on certain aspects of a situation while ignoring equally relevant information.

Beck (1967) identified a number of systematic negative biases in information processing known as logical errors or faulty thinking. These illogical thought patterns are self-defeating and can cause great anxiety or depression for the individual. For example:

- Arbitrary Inference: Drawing a negative conclusion in the absence of supporting data.

- Selective Abstraction: Focusing on the worst aspects of any situation.

- Magnification and Minimisation: If they have a problem, they make it appear bigger than it is. If they have a solution they make it smaller.

- Personalization: Negative events are interpreted as their fault.

- Dichotomous Thinking: Everything is seen as black and white. There is no in between.

Such thoughts exacerbate and are exacerbated by the cognitive triad. Beck believed these thoughts or this way of thinking become automatic.

When a person’s stream of automatic thoughts is very negative, you would expect a person to become depressed. Quite often these negative thoughts will persist even in the face of contrary evidence.

Alloy et al. (1999) followed the thinking styles of young Americans in their early 20s for six years. Their thinking style was tested, and they were placed in either the ‘positive thinking group’ or ‘negative thinking group’.

After six years, the researchers found that only 1% of the positive group developed depression compared to 17% of the ‘negative’ group. These results indicate there may be a link between cognitive style and the development of depression.

However, such a study may suffer from demand characteristics. The results are also correlational. It is important to remember that the precise role of cognitive processes is yet to be determined. The maladaptive cognitions seen in depressed people may be a consequence rather than a cause of depression.

Learned Helplessness

Martin Seligman (1974) proposed a cognitive explanation of depression called learned helplessness .

According to Seligman’s learned helplessness theory, depression occurs when a person learns that their attempts to escape negative situations make no difference.

Consequently, they become passive and will endure aversive stimuli or environments even when escape is possible.

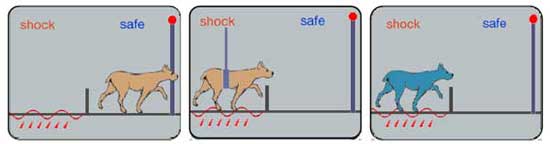

Seligman based his theory on research using dogs.

A dog put into a partitioned cage learns to escape when the floor is electrified. If the dog is restrained whilst being shocked, it eventually stops trying to escape.

Dogs subjected to inescapable electric shocks later failed to escape from shocks even when it was possible to do so. Moreover, they exhibited some of the symptoms of depression found in humans (lethargy, sluggishness, passive in the face of stress, and appetite loss).

This led Seligman (1974) to explain depression in humans in terms of learned helplessness , whereby the individual gives up trying to influence their environment because they have learned that they are helpless as a consequence of having no control over what happens to them.

Although Seligman’s account may explain depression to a certain extent, it fails to take into account cognitions (thoughts). Abramson, Seligman, and Teasdale (1978) consequently introduced a cognitive version of the theory by reformulating learned helplessness in terms of attributional processes (i.e., how people explain the cause of an event).

The depression attributional style is based on three dimensions, namely locus (whether the cause is internal – to do with a person themselves, or external – to do with some aspect of the situation), stability (whether the cause is stable and permanent or unstable and transient) and global or specific (whether the cause relates to the “whole” person or just some particular feature characteristic).

In this new version of the theory, the mere presence of a negative event was not considered sufficient to produce a helpless or depressive state. Instead, Abramson et al. argued that people who attribute failure to internal, stable, and global causes are more likely to become depressed than those who attribute failure to external, unstable, and specific causes.

This is because the former attributional style leads people to the conclusion that they are unable to change things for the better.

Gotlib and Colby (1987) found that people who were formerly depressed are actually no different from people who have never been depressed in terms of their tendencies to view negative events with an attitude of helpless resignation.

This suggests that helplessness could be a symptom rather than a cause of depression. Moreover, it may be that negative thinking generally is also an effect rather than a cause of depression.

Humanist Approach

Humanists believe that there are needs that are unique to the human species. According to Maslow (1962), the most important of these is the need for self-actualization (achieving our potential). The self-actualizing human being has a meaningful life. Anything that blocks our striving to fulfill this need can be a cause of depression. What could cause this?

- Parents impose conditions of worth on their children. I.e., rather than accepting the child for who s/he is and giving unconditional love , parents make love conditional on good behavior. E.g., a child may be blamed for not doing well at school, develop a negative self-image and feel depressed because of a failure to live up to parentally imposed standards.

- Some children may seek to avoid this by denying their true selves and projecting an image of the kind of person they want to be. This façade or false self is an effort to please others. However, the splitting off of the real self from the person you are pretending to cause hatred of the self. The person then comes to despise themselves for living a lie.

- As adults, self-actualization can be undermined by unhappy relationships and unfulfilling jobs. An empty shell marriage means the person is unable to give and receive love from their partner. An alienating job means the person is denied the opportunity to be creative at work.

Abramson, L. Y., Seligman, M. E., & Teasdale, J. D. (1978). Learned helplessness in humans: critique and reformulation . Journal of abnormal psychology, 87(1) , 49.

Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Whitehouse, W. G., Hogan, M. E., Tashman, N. A., Steinberg, D. L., … & Donovan, P. (1999). Depressogenic cognitive styles : Predictive validity, information processing and personality characteristics, and developmental origins. behavior research and therapy, 37(6) , 503-531.

Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: Causes and treatment . Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., & Harrison, R. (1983). Cognitions, attitudes and personality dimensions in depression. British Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy .

Bibring, E. (1953). The mechanism of depression .

Brown, G. W., & Harris, T. (1978). Social origins of depression: a reply. Psychological Medicine, 8(04) , 577-588.

Chodoff, P. (1972). The depressive personality: A critical review. Archives of General Psychiatry, 27(5) , 666-673.

Fenichel, O. (1968). Depression and mania. The Meaning of Despair . New York: Science House.

Freud, S. (1917). Mourning and melancholia. Standard edition, 14(19) , 17.

Gotlib, I. H., & Colby, C. A. (1987). Treatment of depression: An interpersonal systems approach. Pergamon Press.

Klein, M. (1934). Psychogenesis of manic-depressive states: contributions to psychoanalysis . London: Hogarth.

Lewinsohn, P. M. (1974). A behavioral approach to depression .

Maslow, A. H. (1962). Towards a psychology of being . Princeton: D. Van Nostrand Company.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2001). Depression research at the National Institute of Mental Health http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/depression/complete-index.shtml.

Seligman, M. E. (1973). Fall into helplessness. Psychology today, 7(1) , 43-48.

Seligman, M. E. (1974). Depression and learned helplessness . John Wiley & Sons.

Further Information

- List of Support Groups

- Campaign against Living Miserably

- Men do cry: one man’s experience of depression

- NHS Self Help Guides

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Depression (major depressive disorder)

- What is depression? A Mayo Clinic expert explains.

Learn more about depression from Craig Sawchuk, Ph.D., L.P., clinical psychologist at Mayo Clinic.

Hi, I'm Dr. Craig Sawchuk, a clinical psychologist at Mayo Clinic. And I'm here to talk with you about depression. Whether you're looking for answers for yourself, a friend, or loved one, understanding the basics of depression can help you take the next step.

Depression is a mood disorder that causes feelings of sadness that won't go away. Unfortunately, there's a lot of stigma around depression. Depression isn't a weakness or a character flaw. It's not about being in a bad mood, and people who experience depression can't just snap out of it. Depression is a common, serious, and treatable condition. If you're experiencing depression, you're not alone. It honestly affects people of all ages and races and biological sexes, income levels and educational backgrounds. Approximately one in six people will experience a major depressive episode at some point in their lifetime, while up to 16 million adults each year suffer from clinical depression. There are many types of symptoms that make up depression. Emotionally, you may feel sad or down or irritable or even apathetic. Physically, the body really slows down. You feel tired. Your sleep is often disrupted. It's really hard to get yourself motivated. Your thinking also changes. It can just be hard to concentrate. Your thoughts tend to be much more negative. You can be really hard on yourself, feel hopeless and helpless about things. And even in some cases, have thoughts of not wanting to live. Behaviorally, you just want to pull back and withdraw from others, activities, and day-to-day responsibilities. These symptoms all work together to keep you trapped in a cycle of depression. Symptoms of depression are different for everyone. Some symptoms may be a sign of another disorder or medical condition. That's why it's important to get an accurate diagnosis.

While there's no single cause of depression, most experts believe there's a combination of biological, social, and psychological factors that contribute to depression risk. Biologically, we think about genetics or a family history of depression, health conditions such as diabetes, heart disease or thyroid disorders, and even hormonal changes that happen over the lifespan, such as pregnancy and menopause. Changes in brain chemistry, especially disruptions in neurotransmitters like serotonin, that play an important role in regulating many bodily functions, including mood, sleep, and appetite, are thought to play a particularly important role in depression. Socially stressful and traumatic life events, limited access to resources such as food, housing, and health care, and a lack of social support all contribute to depression risk. Psychologically, we think of how negative thoughts and problematic coping behaviors, such as avoidance and substance use, increase our vulnerability to depression.

The good news is that treatment helps. Effective treatments for depression exist and you do have options to see what works best for you. Lifestyle changes that improve sleep habits, exercise, and address underlying health conditions can be an important first step. Medications such as antidepressants can be helpful in alleviating depressive symptoms. Therapy, especially cognitive behavioral therapy, teaches skills to better manage negative thoughts and improve coping behaviors to help break you out of cycles of depression. Whatever the cause, remember that depression is not your fault and it can be treated.

To help diagnose depression, your health care provider may use a physical exam, lab tests, or a mental health evaluation. These results will help identify various treatment options that best fit your situation.

Help is available. You don't have to deal with depression by yourself. Take the next step and reach out. If you're hesitant to talk to a health care provider, talk to a friend or loved one about how to get help. Living with depression isn't easy and you're not alone in your struggles. Always remember that effective treatments and supports are available to help you start feeling better. Want to learn more about depression? Visit mayoclinic.org. Do take care.

Depression is a mood disorder that causes a persistent feeling of sadness and loss of interest. Also called major depressive disorder or clinical depression, it affects how you feel, think and behave and can lead to a variety of emotional and physical problems. You may have trouble doing normal day-to-day activities, and sometimes you may feel as if life isn't worth living.

More than just a bout of the blues, depression isn't a weakness and you can't simply "snap out" of it. Depression may require long-term treatment. But don't get discouraged. Most people with depression feel better with medication, psychotherapy or both.

Depression care at Mayo Clinic

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Begin Exploring Women's Health Solutions at Mayo Clinic Store

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Although depression may occur only once during your life, people typically have multiple episodes. During these episodes, symptoms occur most of the day, nearly every day and may include:

- Feelings of sadness, tearfulness, emptiness or hopelessness

- Angry outbursts, irritability or frustration, even over small matters

- Loss of interest or pleasure in most or all normal activities, such as sex, hobbies or sports

- Sleep disturbances, including insomnia or sleeping too much

- Tiredness and lack of energy, so even small tasks take extra effort

- Reduced appetite and weight loss or increased cravings for food and weight gain

- Anxiety, agitation or restlessness

- Slowed thinking, speaking or body movements

- Feelings of worthlessness or guilt, fixating on past failures or self-blame

- Trouble thinking, concentrating, making decisions and remembering things

- Frequent or recurrent thoughts of death, suicidal thoughts, suicide attempts or suicide

- Unexplained physical problems, such as back pain or headaches

For many people with depression, symptoms usually are severe enough to cause noticeable problems in day-to-day activities, such as work, school, social activities or relationships with others. Some people may feel generally miserable or unhappy without really knowing why.

Depression symptoms in children and teens

Common signs and symptoms of depression in children and teenagers are similar to those of adults, but there can be some differences.

- In younger children, symptoms of depression may include sadness, irritability, clinginess, worry, aches and pains, refusing to go to school, or being underweight.

- In teens, symptoms may include sadness, irritability, feeling negative and worthless, anger, poor performance or poor attendance at school, feeling misunderstood and extremely sensitive, using recreational drugs or alcohol, eating or sleeping too much, self-harm, loss of interest in normal activities, and avoidance of social interaction.

Depression symptoms in older adults

Depression is not a normal part of growing older, and it should never be taken lightly. Unfortunately, depression often goes undiagnosed and untreated in older adults, and they may feel reluctant to seek help. Symptoms of depression may be different or less obvious in older adults, such as:

- Memory difficulties or personality changes

- Physical aches or pain

- Fatigue, loss of appetite, sleep problems or loss of interest in sex — not caused by a medical condition or medication

- Often wanting to stay at home, rather than going out to socialize or doing new things

- Suicidal thinking or feelings, especially in older men

When to see a doctor

If you feel depressed, make an appointment to see your doctor or mental health professional as soon as you can. If you're reluctant to seek treatment, talk to a friend or loved one, any health care professional, a faith leader, or someone else you trust.

When to get emergency help

If you think you may hurt yourself or attempt suicide, call 911 in the U.S. or your local emergency number immediately.

Also consider these options if you're having suicidal thoughts:

- Call your doctor or mental health professional.

- Contact a suicide hotline.

- In the U.S., call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Or use the Lifeline Chat . Services are free and confidential.

- U.S. veterans or service members who are in crisis can call 988 and then press “1” for the Veterans Crisis Line . Or text 838255. Or chat online .

- The Suicide & Crisis Lifeline in the U.S. has a Spanish language phone line at 1-888-628-9454 (toll-free).

- Reach out to a close friend or loved one.

- Contact a minister, spiritual leader or someone else in your faith community.

If you have a loved one who is in danger of suicide or has made a suicide attempt, make sure someone stays with that person. Call 911 or your local emergency number immediately. Or, if you think you can do so safely, take the person to the nearest hospital emergency room.

More Information

Depression (major depressive disorder) care at Mayo Clinic

- Male depression: Understanding the issues

- Nervous breakdown: What does it mean?

- Pain and depression: Is there a link?

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

It's not known exactly what causes depression. As with many mental disorders, a variety of factors may be involved, such as:

- Biological differences. People with depression appear to have physical changes in their brains. The significance of these changes is still uncertain, but may eventually help pinpoint causes.

- Brain chemistry. Neurotransmitters are naturally occurring brain chemicals that likely play a role in depression. Recent research indicates that changes in the function and effect of these neurotransmitters and how they interact with neurocircuits involved in maintaining mood stability may play a significant role in depression and its treatment.

- Hormones. Changes in the body's balance of hormones may be involved in causing or triggering depression. Hormone changes can result with pregnancy and during the weeks or months after delivery (postpartum) and from thyroid problems, menopause or a number of other conditions.

- Inherited traits. Depression is more common in people whose blood relatives also have this condition. Researchers are trying to find genes that may be involved in causing depression.

- Marijuana and depression

- Vitamin B-12 and depression

Risk factors

Depression often begins in the teens, 20s or 30s, but it can happen at any age. More women than men are diagnosed with depression, but this may be due in part because women are more likely to seek treatment.

Factors that seem to increase the risk of developing or triggering depression include:

- Certain personality traits, such as low self-esteem and being too dependent, self-critical or pessimistic

- Traumatic or stressful events, such as physical or sexual abuse, the death or loss of a loved one, a difficult relationship, or financial problems

- Blood relatives with a history of depression, bipolar disorder, alcoholism or suicide

- Being lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender, or having variations in the development of genital organs that aren't clearly male or female (intersex) in an unsupportive situation

- History of other mental health disorders, such as anxiety disorder, eating disorders or post-traumatic stress disorder

- Abuse of alcohol or recreational drugs

- Serious or chronic illness, including cancer, stroke, chronic pain or heart disease

- Certain medications, such as some high blood pressure medications or sleeping pills (talk to your doctor before stopping any medication)

Complications

Depression is a serious disorder that can take a terrible toll on you and your family. Depression often gets worse if it isn't treated, resulting in emotional, behavioral and health problems that affect every area of your life.

Examples of complications associated with depression include:

- Excess weight or obesity, which can lead to heart disease and diabetes

- Pain or physical illness

- Alcohol or drug misuse

- Anxiety, panic disorder or social phobia

- Family conflicts, relationship difficulties, and work or school problems

- Social isolation

- Suicidal feelings, suicide attempts or suicide

- Self-mutilation, such as cutting

- Premature death from medical conditions

- Depression and anxiety: Can I have both?

There's no sure way to prevent depression. However, these strategies may help.

- Take steps to control stress, to increase your resilience and boost your self-esteem.

- Reach out to family and friends, especially in times of crisis, to help you weather rough spells.

- Get treatment at the earliest sign of a problem to help prevent depression from worsening.

- Consider getting long-term maintenance treatment to help prevent a relapse of symptoms.

- Brown AY. Allscripts EPSi. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Nov. 17, 2016.

- Research report: Psychiatry and psychology, 2016-2017. Mayo Clinic. http://www.mayo.edu/research/departments-divisions/department-psychiatry-psychology/overview?_ga=1.199925222.939187614.1464371889. Accessed Jan. 23, 2017.

- Depressive disorders. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5. 5th ed. Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. http://www.psychiatryonline.org. Accessed Jan. 23, 2017.

- Depression. National Institute of Mental Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/depression/index.shtml. Accessed Jan. 23, 2017.

- Depression. National Alliance on Mental Illness. http://www.nami.org/Learn-More/Mental-Health-Conditions/Depression/Overview. Accessed Jan. 23, 2017.

- Depression: What you need to know. National Institute of Mental Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/depression-what-you-need-to-know/index.shtml. Accessed Jan. 23, 2017.

- What is depression? American Psychiatric Association. https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/depression/what-is-depression. Accessed Jan. 23, 2017.

- Depression. NIH Senior Health. https://nihseniorhealth.gov/depression/aboutdepression/01.html. Accessed Jan. 23, 2017.

- Children’s mental health: Anxiety and depression. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/depression.html#depression. Accessed. Jan. 23, 2017.

- Depression and complementary health approaches: What the science says. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/providers/digest/depression-science. Accessed Jan. 23, 2017.

- Depression. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/databases/medical-conditions/d/depression.aspx. Accessed Jan. 23, 2017.

- Natural medicines in the clinical management of depression. Natural Medicines. http://naturaldatabase.therapeuticresearch.com/ce/CECourse.aspx?cs=naturalstandard&s=ND&pm=5&pc=15-111. Accessed Jan. 23, 2017.

- The road to resilience. American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/helpcenter/road-resilience.aspx. Accessed Jan. 23, 2017.

- Simon G, et al. Unipolar depression in adults: Choosing initial treatment. http://www.uptodate.com/home. Accessed Jan. 23, 2017.

- Stewart D, et al. Risks of antidepressants during pregnancy: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). http://www.uptodate.com/home. Accessed Jan. 23, 2017.

- Kimmel MC, et al. Safety of infant exposure to antidepressants and benzodiazepines through breastfeeding. http://www.uptodate.com/home. Accessed Jan. 23, 2017.

- Bipolar and related disorders. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5. 5th ed. Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. http://www.psychiatryonline.org. Accessed Jan. 23, 2017.

- Hirsch M, et al. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) for treating depressed adults. http://www.uptodate.com/home. Accessed Jan. 24, 2017.

- Hall-Flavin DK (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Jan. 31, 2017.

- Krieger CA (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. Feb. 2, 2017.

- Antidepressant withdrawal: Is there such a thing?

- Antidepressants and alcohol: What's the concern?

- Antidepressants and weight gain: What causes it?

- Antidepressants: Can they stop working?

- Antidepressants: Selecting one that's right for you

- Antidepressants: Side effects

- Antidepressants: Which cause the fewest sexual side effects?

- Atypical antidepressants

- Clinical depression: What does that mean?

- Depression in women: Understanding the gender gap

- Depression, anxiety and exercise

- Depression: Supporting a family member or friend

- MAOIs and diet: Is it necessary to restrict tyramine?

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

- Natural remedies for depression: Are they effective?

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

- Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

- Treatment-resistant depression

- Tricyclic antidepressants and tetracyclic antidepressants

Associated Procedures

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

- Psychotherapy

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation

- Vagus nerve stimulation

News from Mayo Clinic

- Mayo Clinic Q and A: How to support a loved one with depression Oct. 23, 2022, 11:00 a.m. CDT

- Mayo study lays foundation to predict antidepressant response in people with suicide attempts Oct. 03, 2022, 03:30 p.m. CDT

- Science Saturday: Researchers validate threshold for determining effectiveness of antidepressant treatment Aug. 27, 2022, 11:00 a.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic expert explains differences between adult and teen depression May 24, 2022, 12:19 p.m. CDT

Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, has been recognized as one of the top Psychiatry hospitals in the nation for 2023-2024 by U.S. News & World Report.

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Let’s celebrate our doctors!

Join us in celebrating and honoring Mayo Clinic physicians on March 30th for National Doctor’s Day.

Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Depression — Depression: Definition, Risks, Symptoms and Treatment

Depression: Definition, Risks, Symptoms and Treatment

- Categories: Depression

About this sample

Words: 585 |

Published: Jan 29, 2019

See expert comments

Words: 585 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

- Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs),

- Atypical antidepressants,

- Tricyclic antidepressants,

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), or other medications.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1087 words

1 pages / 605 words

1 pages / 618 words

2 pages / 834 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Depression

Pessimism and depression are two psychological phenomena that often go hand in hand, creating a complex and challenging experience for those who grapple with them. While pessimism is a general outlook characterized by a negative [...]

Nurse burnout has become a pressing issue in the healthcare industry, with detrimental effects on both nurses and patient care. Understanding the causes and effects of burnout, as well as implementing strategies for prevention, [...]

Depression is a prevalent mental health condition that affects millions of people worldwide. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), depression is the leading cause of disability globally, and it is a major contributor [...]

Depression is a common mental health disorder that affects millions of people worldwide. It can have a significant impact on an individual's quality of life and overall well-being. Understanding the causes, symptoms, and [...]

In the world of psychology, the case study of Ileana Chivescu stands out as a compelling and complex examination of the human mind. This tale of a young woman's struggle with anxiety, depression, and self-doubt offers a poignant [...]

Obesity and Depression today are one of the biggest issues that our societies are facing. These two problems are looked differently upon by the masses however they both share common links and connections between in which both [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Essay On Depression: Causes, Symptoms And Effects

Our life is full of emotional ups and downs, but when the time of down lasts too long or influences our ability to function, in this case, probably, you suffer from common serious illness, which is called depression. Clinical depression affects your mood, thinking process, your body and behaviour. According to the researches, in the United States about 19 million people, i.e. one in ten adults, annually suffer from depression, and about 2/3 of them do not get necessary help. An appropriate treatment can alleviate symptoms of depression in more than 80% of such cases. However, since depression is usually not recognized, it continues to cause unnecessary suffering.

Depression is a disease that dominates you and weakens your body, it influences men as well as women, but women experience depression about two times more often than men.

Since this issue is very urgent nowadays, we decided to write this cause and effect essay on depression to attract the public attention one more time to this problem. I hope it will be informative and instructive for you. If you are interested in reading essays on similar or any other topic, you should visit our website . There you will find not only various essays, but also you can get help in essay writing . All you need is to contact our team, and everything else we will do for you.

Depression is a strong psychological disorder, from which usually suffers not only a patients, but also his / hers family, relatives, friends etc.

General information

More often depression develops on the basis of stress or prolonged traumatic situation. Frequently depressive disorders hide under the guise of a bad mood or temper features. In order to prevent severe consequences it is important to figure out how and why depression begins.

Symptoms and causes of depression

As a rule, depression develops slowly and insensibly for a person and for his close ones. At the initial stage most of people are not aware about their illness, because they think that many symptoms are just the features of their personality. Experiencing inner discomfort, which can be difficult to express in words, people do not ask for professional help, as a rule. They usually go to doctor at the moment, when the disease is already firmly holds the patient causing unbearable suffering.

Risk factors for depression:

- being female;

- the presence of depression in family anamnesis;

- early depression in anamnesis;

- early loss of parents;

- the experience of violence in anamnesis;

- personal features;

- stressors (parting, guilt);

- alcohol / drug addiction;

- neurological diseases (Parkinson's disease, apoplexy).

Signs of depression

Depression influences negatively all the aspects of human life. Inadequate psychological defense mechanisms, in their turn, affect destructively not only psychological, but also biological processes.

The first signs of depression are apathy, not depending on the circumstances, indifference to everything what is going on, weakening of motor activity; these are the main clinical symptoms of depression . If their combination is observed for more than two weeks, urgent professional help is required.

Psychological symptoms:

- depressed mood, unhappiness;

- loss of interest, reduced motivation, loss of energy;

- self-doubt, guilt, inner emptiness;

- decrease in speed of thinking, inability to make decisions;

- anxiety, fear and pessimism about the future;

- daily fluctuations;

- possible delirium;

- suicidal thoughts.

Somatic symptoms:

- vital disorders;

- disturbed sleep (early waking, oversleeping);

- eating disorders;

- constipation;

- feeling of tightness of the skull, dizziness, feeling of compression;

- vegetative symptoms.

Causes of depression

It is accepted to think in modern psychiatry that the development of depression, as well as most of other mental disorders, requires the combined effect of three factors: psychological, biological and social.

Psychological factor (“Personality structure”)

There are three types of personality especially prone to depression:

1) “Statothymic personality” that is characterized by exaggerated conscientiousness, diligence, accuracy;

2) Melancholic personality type with its desire for order, constancy, pedantry, exessive demands on itself;

3) Hyperthymic type of personality that is characterized by self-doubt, frequent worries, with obviously low self-esteem.

People, whose organism biologically tends to depression development, due to education and other social environmental factors form such personality features, which in adverse social situations, especially while chronic stress, cause failure of psychological adaptation mechanisms, skills to deal with stress or lack of coping strategies.

Such people are characterized by:

- lack of confidence in their own abilities;

- excessive secrecy and isolation;

- excessive self-critical attitude towards yourself;

- waiting for the support of the close ones;

- developed pessimism;

- inability to resist stress situations;

- emotional expressiveness.

Biological factor:

- the presence of unfavorable heredity;

- somatic and neurological head injury that violated brain activity;

- changes in the hormonal system;

- chronobiological factors: seasonal depressive disorders, daily fluctuations, shortening of REM sleep;

- side effects of some medications.

- Heredity and family tendency to depression play significant role in predisposition to this disease. It is noticed that relatives of those who suffer from depression usually have different psychosomatic disorders.

Social factor: