Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write a rhetorical analysis | Key concepts & examples

How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis | Key Concepts & Examples

Published on August 28, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

A rhetorical analysis is a type of essay that looks at a text in terms of rhetoric. This means it is less concerned with what the author is saying than with how they say it: their goals, techniques, and appeals to the audience.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Key concepts in rhetoric, analyzing the text, introducing your rhetorical analysis, the body: doing the analysis, concluding a rhetorical analysis, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about rhetorical analysis.

Rhetoric, the art of effective speaking and writing, is a subject that trains you to look at texts, arguments and speeches in terms of how they are designed to persuade the audience. This section introduces a few of the key concepts of this field.

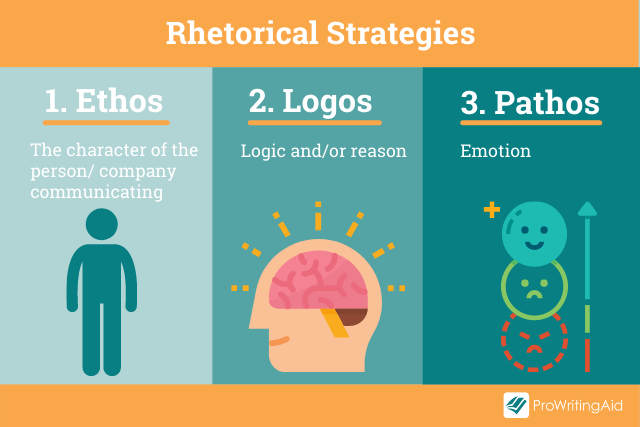

Appeals: Logos, ethos, pathos

Appeals are how the author convinces their audience. Three central appeals are discussed in rhetoric, established by the philosopher Aristotle and sometimes called the rhetorical triangle: logos, ethos, and pathos.

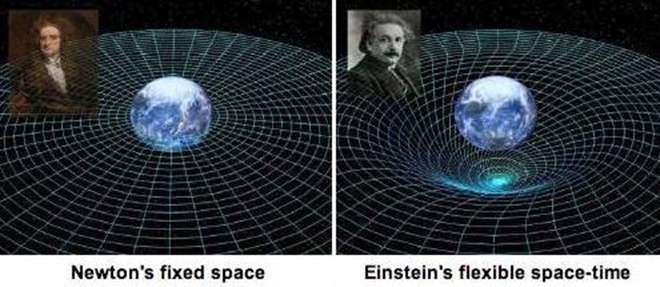

Logos , or the logical appeal, refers to the use of reasoned argument to persuade. This is the dominant approach in academic writing , where arguments are built up using reasoning and evidence.

Ethos , or the ethical appeal, involves the author presenting themselves as an authority on their subject. For example, someone making a moral argument might highlight their own morally admirable behavior; someone speaking about a technical subject might present themselves as an expert by mentioning their qualifications.

Pathos , or the pathetic appeal, evokes the audience’s emotions. This might involve speaking in a passionate way, employing vivid imagery, or trying to provoke anger, sympathy, or any other emotional response in the audience.

These three appeals are all treated as integral parts of rhetoric, and a given author may combine all three of them to convince their audience.

Text and context

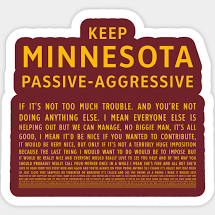

In rhetoric, a text is not necessarily a piece of writing (though it may be this). A text is whatever piece of communication you are analyzing. This could be, for example, a speech, an advertisement, or a satirical image.

In these cases, your analysis would focus on more than just language—you might look at visual or sonic elements of the text too.

The context is everything surrounding the text: Who is the author (or speaker, designer, etc.)? Who is their (intended or actual) audience? When and where was the text produced, and for what purpose?

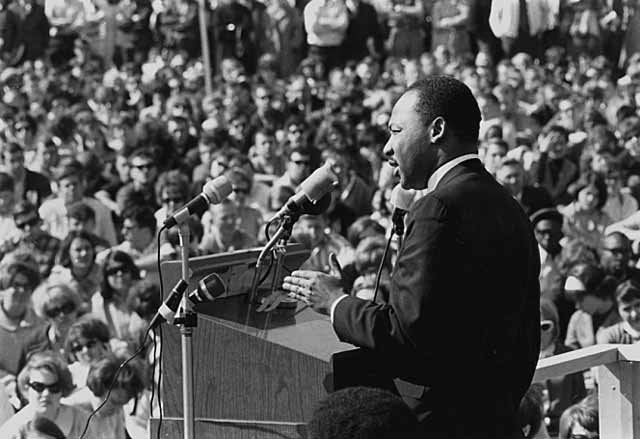

Looking at the context can help to inform your rhetorical analysis. For example, Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech has universal power, but the context of the civil rights movement is an important part of understanding why.

Claims, supports, and warrants

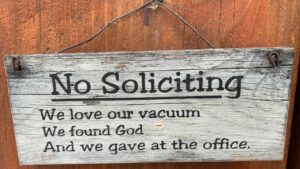

A piece of rhetoric is always making some sort of argument, whether it’s a very clearly defined and logical one (e.g. in a philosophy essay) or one that the reader has to infer (e.g. in a satirical article). These arguments are built up with claims, supports, and warrants.

A claim is the fact or idea the author wants to convince the reader of. An argument might center on a single claim, or be built up out of many. Claims are usually explicitly stated, but they may also just be implied in some kinds of text.

The author uses supports to back up each claim they make. These might range from hard evidence to emotional appeals—anything that is used to convince the reader to accept a claim.

The warrant is the logic or assumption that connects a support with a claim. Outside of quite formal argumentation, the warrant is often unstated—the author assumes their audience will understand the connection without it. But that doesn’t mean you can’t still explore the implicit warrant in these cases.

For example, look at the following statement:

We can see a claim and a support here, but the warrant is implicit. Here, the warrant is the assumption that more likeable candidates would have inspired greater turnout. We might be more or less convinced by the argument depending on whether we think this is a fair assumption.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Rhetorical analysis isn’t a matter of choosing concepts in advance and applying them to a text. Instead, it starts with looking at the text in detail and asking the appropriate questions about how it works:

- What is the author’s purpose?

- Do they focus closely on their key claims, or do they discuss various topics?

- What tone do they take—angry or sympathetic? Personal or authoritative? Formal or informal?

- Who seems to be the intended audience? Is this audience likely to be successfully reached and convinced?

- What kinds of evidence are presented?

By asking these questions, you’ll discover the various rhetorical devices the text uses. Don’t feel that you have to cram in every rhetorical term you know—focus on those that are most important to the text.

The following sections show how to write the different parts of a rhetorical analysis.

Like all essays, a rhetorical analysis begins with an introduction . The introduction tells readers what text you’ll be discussing, provides relevant background information, and presents your thesis statement .

Hover over different parts of the example below to see how an introduction works.

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech is widely regarded as one of the most important pieces of oratory in American history. Delivered in 1963 to thousands of civil rights activists outside the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., the speech has come to symbolize the spirit of the civil rights movement and even to function as a major part of the American national myth. This rhetorical analysis argues that King’s assumption of the prophetic voice, amplified by the historic size of his audience, creates a powerful sense of ethos that has retained its inspirational power over the years.

The body of your rhetorical analysis is where you’ll tackle the text directly. It’s often divided into three paragraphs, although it may be more in a longer essay.

Each paragraph should focus on a different element of the text, and they should all contribute to your overall argument for your thesis statement.

Hover over the example to explore how a typical body paragraph is constructed.

King’s speech is infused with prophetic language throughout. Even before the famous “dream” part of the speech, King’s language consistently strikes a prophetic tone. He refers to the Lincoln Memorial as a “hallowed spot” and speaks of rising “from the dark and desolate valley of segregation” to “make justice a reality for all of God’s children.” The assumption of this prophetic voice constitutes the text’s strongest ethical appeal; after linking himself with political figures like Lincoln and the Founding Fathers, King’s ethos adopts a distinctly religious tone, recalling Biblical prophets and preachers of change from across history. This adds significant force to his words; standing before an audience of hundreds of thousands, he states not just what the future should be, but what it will be: “The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.” This warning is almost apocalyptic in tone, though it concludes with the positive image of the “bright day of justice.” The power of King’s rhetoric thus stems not only from the pathos of his vision of a brighter future, but from the ethos of the prophetic voice he adopts in expressing this vision.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

The conclusion of a rhetorical analysis wraps up the essay by restating the main argument and showing how it has been developed by your analysis. It may also try to link the text, and your analysis of it, with broader concerns.

Explore the example below to get a sense of the conclusion.

It is clear from this analysis that the effectiveness of King’s rhetoric stems less from the pathetic appeal of his utopian “dream” than it does from the ethos he carefully constructs to give force to his statements. By framing contemporary upheavals as part of a prophecy whose fulfillment will result in the better future he imagines, King ensures not only the effectiveness of his words in the moment but their continuing resonance today. Even if we have not yet achieved King’s dream, we cannot deny the role his words played in setting us on the path toward it.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

The goal of a rhetorical analysis is to explain the effect a piece of writing or oratory has on its audience, how successful it is, and the devices and appeals it uses to achieve its goals.

Unlike a standard argumentative essay , it’s less about taking a position on the arguments presented, and more about exploring how they are constructed.

The term “text” in a rhetorical analysis essay refers to whatever object you’re analyzing. It’s frequently a piece of writing or a speech, but it doesn’t have to be. For example, you could also treat an advertisement or political cartoon as a text.

Logos appeals to the audience’s reason, building up logical arguments . Ethos appeals to the speaker’s status or authority, making the audience more likely to trust them. Pathos appeals to the emotions, trying to make the audience feel angry or sympathetic, for example.

Collectively, these three appeals are sometimes called the rhetorical triangle . They are central to rhetorical analysis , though a piece of rhetoric might not necessarily use all of them.

In rhetorical analysis , a claim is something the author wants the audience to believe. A support is the evidence or appeal they use to convince the reader to believe the claim. A warrant is the (often implicit) assumption that links the support with the claim.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write a Rhetorical Analysis | Key Concepts & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/rhetorical-analysis/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write an argumentative essay | examples & tips, how to write a literary analysis essay | a step-by-step guide, comparing and contrasting in an essay | tips & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Rhetorical Situations

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This presentation is designed to introduce your students to a variety of factors that contribute to strong, well-organized writing. This presentation is suitable for the beginning of a composition course or the assignment of a writing project in any class.

This resource is enhanced by a PowerPoint file. If you have a Microsoft Account, you can view this file with PowerPoint Online .

Understanding and being able to analyze rhetorical situations can help contribute to strong, audience-focused, and organized writing. The PowerPoint presentation in the Media box above is suitable for any classroom and any writing task. The resource below explains in more detail how to analyze rhetorical situations.

Understanding Rhetoric

Writing instructors and many other professionals who study language use the phrase “rhetorical situation.” This term refers to any set of circumstances that involves at least one person using some sort of communication to modify the perspective of at least one other person. But many people are unfamiliar with the word “rhetoric.” For many people, “rhetoric” may imply speech that is simply persuasive. For others, “rhetoric” may imply something more negative like “trickery” or even “lying.” So to appreciate the benefits of understanding what rhetorical situations are, we must first have a more complete understanding of what rhetoric itself is.

In brief, “rhetoric” is any communication used to modify the perspectives of others. But this is a very broad definition that calls for more explanation.

The OWL’s “ Introduction to Rhetoric ” vidcast explains more what rhetoric is and how rhetoric relates to writing. This vidcast defines rhetoric as “primarily an awareness of the language choices we make.” It gives a brief history of the origins of rhetoric in ancient Greece. And it briefly discusses the benefits of how understanding rhetoric can help people write more convincingly. The vidcast provides an excellent primer to some basic ideas of rhetoric.

A more in-depth primer to rhetoric can be found in the online video “In Defense of Rhetoric: No Longer Just for Liars.” This video dispels some widely held misconceptions about rhetoric and emphasizes that, “An education of rhetoric enables communicators in any facet of any field to create and assess messages effectively.” This video should be particularly helpful to anyone who is unaware of how crucial rhetoric is to effective communication.

“ In Defense of Rhetoric: No Longer Just for Liars ” is a 14-minunte video created by graduate students in the MA in Professional Communication program at Clemson University, and you are free to copy, distribute, and transmit the video with the understanding: 1) that you will attribute the work to its authors; 2) that you will not use the work for commercial purposes; and 3) that you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.

Listening to the above podcast and watching the above video should help anyone using this resource to better understand the basics of rhetoric and rhetorical situations.

A Review of Rhetoric: From “Persuasion” to “Identification”

Just as the vidcast and video above imply, rhetoric can refer to just the persuasive qualities of language. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle strongly influenced how people have traditionally viewed rhetoric. Aristotle defined rhetoric as “an ability, in each particular case, to see the available means of persuasion” (Aristotle Rhetoric I.1.2, Kennedy 37). Since then, Aristotle’s definition of rhetoric has been reduced in many situations to mean simply “persuasion.” At its best, this simplification of rhetoric has led to a long tradition of people associating rhetoric with politicians, lawyers, or other occupations noted for persuasive speaking. At its worst, the simplification of rhetoric has led people to assume that rhetoric is merely something that manipulative people use to get what they want (usually regardless of moral or ethical concerns).

However, over the last century or so, the academic definition and use of “rhetoric” has evolved to include any situation in which people consciously communicate with each other. In brief, individual people tend to perceive and understand just about everything differently from one another (this difference varies to a lesser or greater degree depending on the situation, of course). This expanded perception has led a number of more contemporary rhetorical philosophers to suggest that rhetoric deals with more than just persuasion. Instead of just persuasion, rhetoric is the set of methods people use to identify with each other—to encourage each other to understand things from one another’s perspectives (see Burke 25). From interpersonal relationships to international peace treaties, the capacity to understand or modify another’s perspective is one of the most vital abilities that humans have. Hence, understanding rhetoric in terms of “identification” helps us better communicate and evaluate all such situations.

Works Cited

Aristotle. On Rhetoric: A Theory of Civic Discourse . 2nd ed. Trans. George A. Kennedy. New York: Oxford UP, 2007.

Burke, Kenneth. A Rhetoric of Motives . Berkeley: U of California P, 1969.

Johnson-Sheehan, Richard and Charles Paine. Writing Today . New York: Pearson Education, 2010.

Get 25% OFF new yearly plans in our Spring Sale

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

What Is a Rhetorical Analysis and How to Write a Great One

Helly Douglas

Do you have to write a rhetorical analysis essay? Fear not! We’re here to explain exactly what rhetorical analysis means, how you should structure your essay, and give you some essential “dos and don’ts.”

What is a Rhetorical Analysis Essay?

How do you write a rhetorical analysis, what are the three rhetorical strategies, what are the five rhetorical situations, how to plan a rhetorical analysis essay, creating a rhetorical analysis essay, examples of great rhetorical analysis essays, final thoughts.

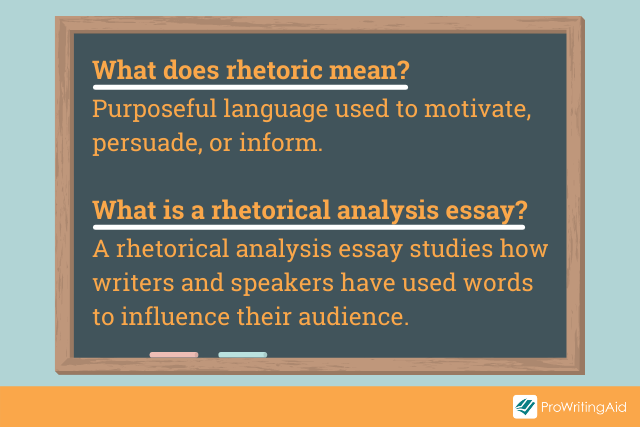

A rhetorical analysis essay studies how writers and speakers have used words to influence their audience. Think less about the words the author has used and more about the techniques they employ, their goals, and the effect this has on the audience.

In your analysis essay, you break a piece of text (including cartoons, adverts, and speeches) into sections and explain how each part works to persuade, inform, or entertain. You’ll explore the effectiveness of the techniques used, how the argument has been constructed, and give examples from the text.

A strong rhetorical analysis evaluates a text rather than just describes the techniques used. You don’t include whether you personally agree or disagree with the argument.

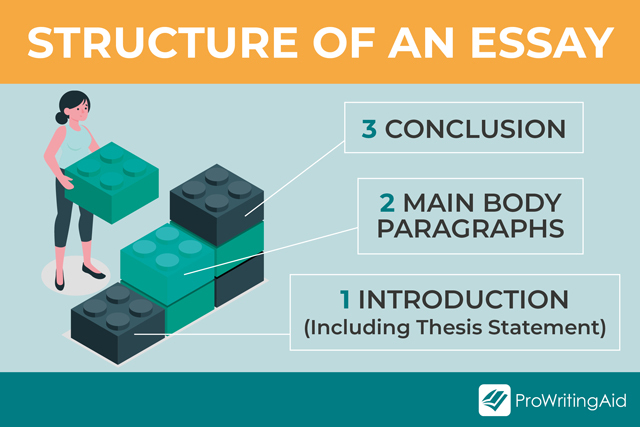

Structure a rhetorical analysis in the same way as most other types of academic essays . You’ll have an introduction to present your thesis, a main body where you analyze the text, which then leads to a conclusion.

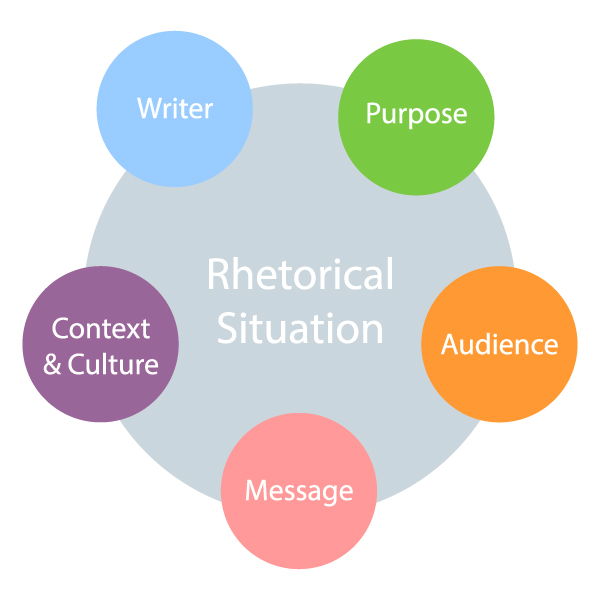

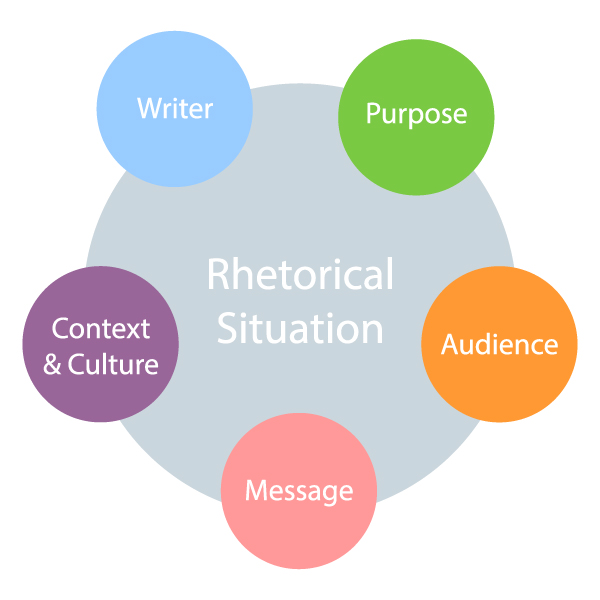

Think about how the writer (also known as a rhetor) considers the situation that frames their communication:

- Topic: the overall purpose of the rhetoric

- Audience: this includes primary, secondary, and tertiary audiences

- Purpose: there are often more than one to consider

- Context and culture: the wider situation within which the rhetoric is placed

Back in the 4th century BC, Aristotle was talking about how language can be used as a means of persuasion. He described three principal forms —Ethos, Logos, and Pathos—often referred to as the Rhetorical Triangle . These persuasive techniques are still used today.

Rhetorical Strategy 1: Ethos

Are you more likely to buy a car from an established company that’s been an important part of your community for 50 years, or someone new who just started their business?

Reputation matters. Ethos explores how the character, disposition, and fundamental values of the author create appeal, along with their expertise and knowledge in the subject area.

Aristotle breaks ethos down into three further categories:

- Phronesis: skills and practical wisdom

- Arete: virtue

- Eunoia: goodwill towards the audience

Ethos-driven speeches and text rely on the reputation of the author. In your analysis, you can look at how the writer establishes ethos through both direct and indirect means.

Rhetorical Strategy 2: Pathos

Pathos-driven rhetoric hooks into our emotions. You’ll often see it used in advertisements, particularly by charities wanting you to donate money towards an appeal.

Common use of pathos includes:

- Vivid description so the reader can imagine themselves in the situation

- Personal stories to create feelings of empathy

- Emotional vocabulary that evokes a response

By using pathos to make the audience feel a particular emotion, the author can persuade them that the argument they’re making is compelling.

Rhetorical Strategy 3: Logos

Logos uses logic or reason. It’s commonly used in academic writing when arguments are created using evidence and reasoning rather than an emotional response. It’s constructed in a step-by-step approach that builds methodically to create a powerful effect upon the reader.

Rhetoric can use any one of these three techniques, but effective arguments often appeal to all three elements.

The rhetorical situation explains the circumstances behind and around a piece of rhetoric. It helps you think about why a text exists, its purpose, and how it’s carried out.

The rhetorical situations are:

- 1) Purpose: Why is this being written? (It could be trying to inform, persuade, instruct, or entertain.)

- 2) Audience: Which groups or individuals will read and take action (or have done so in the past)?

- 3) Genre: What type of writing is this?

- 4) Stance: What is the tone of the text? What position are they taking?

- 5) Media/Visuals: What means of communication are used?

Understanding and analyzing the rhetorical situation is essential for building a strong essay. Also think about any rhetoric restraints on the text, such as beliefs, attitudes, and traditions that could affect the author's decisions.

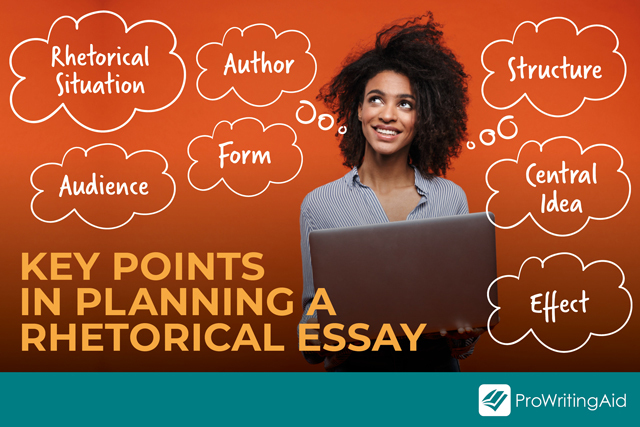

Before leaping into your essay, it’s worth taking time to explore the text at a deeper level and considering the rhetorical situations we looked at before. Throw away your assumptions and use these simple questions to help you unpick how and why the text is having an effect on the audience.

1: What is the Rhetorical Situation?

- Why is there a need or opportunity for persuasion?

- How do words and references help you identify the time and location?

- What are the rhetoric restraints?

- What historical occasions would lead to this text being created?

2: Who is the Author?

- How do they position themselves as an expert worth listening to?

- What is their ethos?

- Do they have a reputation that gives them authority?

- What is their intention?

- What values or customs do they have?

3: Who is it Written For?

- Who is the intended audience?

- How is this appealing to this particular audience?

- Who are the possible secondary and tertiary audiences?

4: What is the Central Idea?

- Can you summarize the key point of this rhetoric?

- What arguments are used?

- How has it developed a line of reasoning?

5: How is it Structured?

- What structure is used?

- How is the content arranged within the structure?

6: What Form is Used?

- Does this follow a specific literary genre?

- What type of style and tone is used, and why is this?

- Does the form used complement the content?

- What effect could this form have on the audience?

7: Is the Rhetoric Effective?

- Does the content fulfil the author’s intentions?

- Does the message effectively fit the audience, location, and time period?

Once you’ve fully explored the text, you’ll have a better understanding of the impact it’s having on the audience and feel more confident about writing your essay outline.

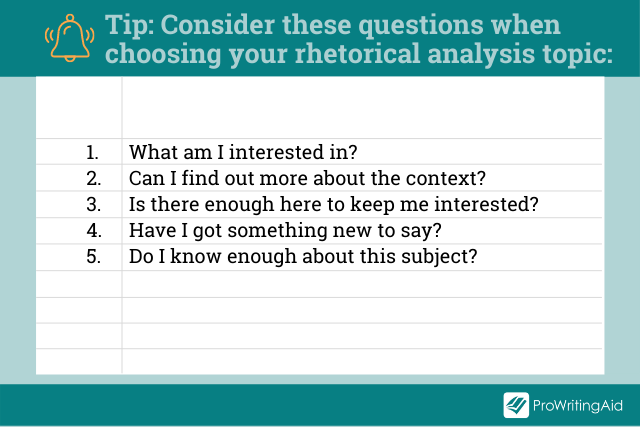

A great essay starts with an interesting topic. Choose carefully so you’re personally invested in the subject and familiar with it rather than just following trending topics. There are lots of great ideas on this blog post by My Perfect Words if you need some inspiration. Take some time to do background research to ensure your topic offers good analysis opportunities.

Remember to check the information given to you by your professor so you follow their preferred style guidelines. This outline example gives you a general idea of a format to follow, but there will likely be specific requests about layout and content in your course handbook. It’s always worth asking your institution if you’re unsure.

Make notes for each section of your essay before you write. This makes it easy for you to write a well-structured text that flows naturally to a conclusion. You will develop each note into a paragraph. Look at this example by College Essay for useful ideas about the structure.

1: Introduction

This is a short, informative section that shows you understand the purpose of the text. It tempts the reader to find out more by mentioning what will come in the main body of your essay.

- Name the author of the text and the title of their work followed by the date in parentheses

- Use a verb to describe what the author does, e.g. “implies,” “asserts,” or “claims”

- Briefly summarize the text in your own words

- Mention the persuasive techniques used by the rhetor and its effect

Create a thesis statement to come at the end of your introduction.

After your introduction, move on to your critical analysis. This is the principal part of your essay.

- Explain the methods used by the author to inform, entertain, and/or persuade the audience using Aristotle's rhetorical triangle

- Use quotations to prove the statements you make

- Explain why the writer used this approach and how successful it is

- Consider how it makes the audience feel and react

Make each strategy a new paragraph rather than cramming them together, and always use proper citations. Check back to your course handbook if you’re unsure which citation style is preferred.

3: Conclusion

Your conclusion should summarize the points you’ve made in the main body of your essay. While you will draw the points together, this is not the place to introduce new information you’ve not previously mentioned.

Use your last sentence to share a powerful concluding statement that talks about the impact the text has on the audience(s) and wider society. How have its strategies helped to shape history?

Before You Submit

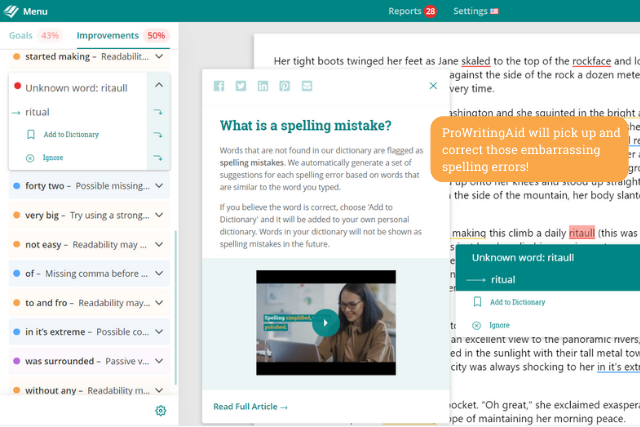

Poor spelling and grammatical errors ruin a great essay. Use ProWritingAid to check through your finished essay before you submit. It will pick up all the minor errors you’ve missed and help you give your essay a final polish. Look at this useful ProWritingAid webinar for further ideas to help you significantly improve your essays. Sign up for a free trial today and start editing your essays!

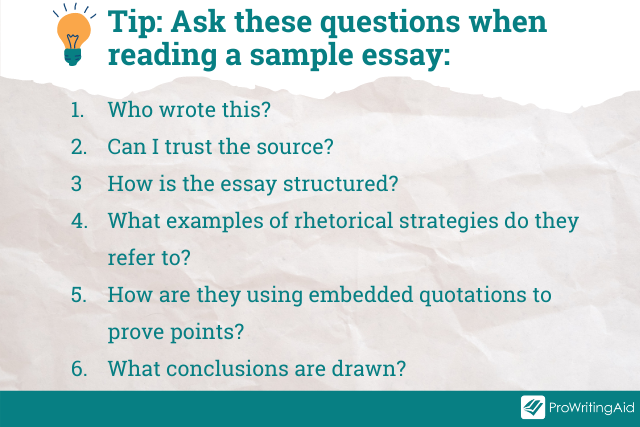

You’ll find countless examples of rhetorical analysis online, but they range widely in quality. Your institution may have example essays they can share with you to show you exactly what they’re looking for.

The following links should give you a good starting point if you’re looking for ideas:

Pearson Canada has a range of good examples. Look at how embedded quotations are used to prove the points being made. The end questions help you unpick how successful each essay is.

Excelsior College has an excellent sample essay complete with useful comments highlighting the techniques used.

Brighton Online has a selection of interesting essays to look at. In this specific example, consider how wider reading has deepened the exploration of the text.

Writing a rhetorical analysis essay can seem daunting, but spending significant time deeply analyzing the text before you write will make it far more achievable and result in a better-quality essay overall.

It can take some time to write a good essay. Aim to complete it well before the deadline so you don’t feel rushed. Use ProWritingAid’s comprehensive checks to find any errors and make changes to improve readability. Then you’ll be ready to submit your finished essay, knowing it’s as good as you can possibly make it.

Try ProWritingAid's Editor for Yourself

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Helly Douglas is a UK writer and teacher, specialising in education, children, and parenting. She loves making the complex seem simple through blogs, articles, and curriculum content. You can check out her work at hellydouglas.com or connect on Twitter @hellydouglas. When she’s not writing, you will find her in a classroom, being a mum or battling against the wilderness of her garden—the garden is winning!

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Table of Contents

Collaboration, information literacy, writing process, rhetorical situation.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

The rhetorical situation refers to the contextual variables (e.g. audience , purpose , and topic ) that influence composing and interpretation . Learn how to engage in rhetorical analysis of your rhetorical situation so you can create texts that your readers find to be clear and cogent, even if they don't necessarily agree with your argument , thesis , research question or hypothesis.

What is the Rhetorical Situation?

The rhetorical situation refers to

- Exigence — the driving force behind the call to write or speak. It’s the situation that prompts the need for communication , urging the speaker or writer to use discourse to respond to a particular matter

- Audience — the specific individuals or groups (aka discourse communities) to whom the discourse is directed

- Constraints — the effects of rhetorical affordances and constraints on communication, composing and style

The Rhetorical Situation may also be called occasion; rhetorical situation ; rhetorical occasion ; situational constraints; the spin room; the no-spin room, the communication situation.

Rhetorical Situations are sometimes described as formal, semi-formal, or informal. They may also be described as home-based, school-based, or work-based .

Related Concepts: Epistemology ; Rhetoric ; Rhetorical Analysis ; Rhetorical Stance

We are always situated, in situations, in the world, in a context, living in a certain way with others, trying to achieve this and avoid that. Eugene Gendlin, p.2

Why Does the Rhetorical Situation Matter?

Writers, speakers, and knowledge workers . . . need a robust understanding of the rhetorical situation in order to respond appropriately to an exigency , a call for discourse.

Having “rhetorical knowledge” and being able to In order to determine the available means of persuasion., successful communicators analyze their rhetorical situation .

Rhetorical Theory has been a major subject of study and conversation among writers and speakers since the 5th century BCE, when sophists taught persuasive techniques to young aristocrats who hoped to succeed in legal and political arenas. Rhetorical theories provide insights into ways writers and speakers can craft their messages so they are persuasive.

Rhetorical theory has had a profound impact on writing instruction in the U.S. The CWPA (Council of Writing Program Administrators) defines rhetorical knowledge as a foundational competency in college-level writing:

“The assertion that writing is “rhetorical” means that writing is always shaped by a combination of the purposes and expectations of writers and readers and the uses that writing serves in specific contexts. To be rhetorically sensitive, good writers must be flexible. They should be able to pursue their purposes by consciously adapting their writing both to the contexts in which it will be read and to the expectations, knowledge, experiences, values, and beliefs of their readers. They also must understand how to take advantage of the opportunities with which they are presented and to address the constraints they encounter as they write. In practice, this means that writers learn to identify what is possible and not possible in diverse writing situations. Writing an email to a friend holds different possibilities for language and form than does writing a lab report for submission to an instructor in a biology class. Instructors emphasize the rhetorical nature of writing by providing writers opportunities to study the expectations, values, and norms associated with writing in specific contexts. This principle is fundamental to the study of writing and writing instruction. It informs all other principles in this document” (Conference 2015).

What is Rhetorical Analysis?

Since antiquity, rhetoricians have exhorted writers and speakers to think deeply and carefully about their audience , purpose , and topic . In the rhetorical tradition, this process—this activity of considering what you want to say, your purpose , and then adjusting what you want to say based on your evaluation of your audience —is called rhetorical analysis .

Rhetorical Analysis begins with a careful consideration of the contextual variables that need to be considered to respond with clarity and persuasion to the communication situation.

Scholarly conversations about what those contextual variables are have evolved over time.

Loyd Bitzer’s Rhetorical Model

In 1968, Loyd Bitzer, a rhetorician, articulated a theoretical model of the rhetorical situation.

Bitzer depicts the rhetorical situation as

- “a complex of persons, events, objects, and relations presenting an actual or potential exigence [emphasis added] which can be completely or partially removed if discourse, introduced into the situation, can so constrain human decision or action as to bring about the significant modification of the exigence” (p.9).

Thus, Bitzer imagines the rhetorical situation as a dynamic between three primary forces:

- Constraints

For Bitzer, the impetus for writing or speaking is the situation:

- “Rhetorical discourse is called into existence by situation” (p. 9).

- The situation gives rise to an exigency , which is “an imperfection marked by urgency; it is a defect, an obstacle, something waiting to be done, a thing that is other than it should be” (p. 6)

Moreover, Bitzer argues the situation presumes a response:

- “the situation dictates the sorts of observations to be made; it dictates the significant physical and verbal responses. . . .” (p. 5)

Bitzer’s theory of the rhetorical situation, published as the first article in a new academic journal ( Rhetoric and Philosophy ) initiated an academic conversation that is still ongoing. To this day, Bitzer is credited for introducing the concept of exigency and for questioning how constraints — persons, events, objects, and relations –impinge on composing.

Furthermore, Bitzer deserves credit for introducing the notion that writing occurs in a sociocultural context–i.e., that there are rhetorical constraints that exist in the material world that shape how writers and speakers should respond to exigencies, situations.

However, in contemporary Writing Studies (as well as other academic disciplines), Bitzer’s argument that “Rhetorical discourse is called into existence by situation” (p. 9) has been disputed on theoretical and empirical grounds :

- Empirical Grounds Bitzer’s model presumes that the writer or speaker lacks agency, that they are merely reactive to situations, that the situation determines whether or not something is translated to discourse/text or not. In contrast to this view, empirical research has found that writers and speakers bring their own agendas and desires to writing situations. When people enter a new rhetorical situation, they have aims/purposes, personalities, literacy histories, past experiences. All of those histories and more shape the their perception of the rhetorical situation, their invention, research, and reasoning processes. Rhetors experience an incessant flow of occasions and problems during their lives. And it is the rhetor who chooses to focus on any one particular rhetorical situation.

- linguistic constraints

- material constraints (e.g., timing, economics, governments, technology)

- ideological constraints (especially gender, class, and race).

The Ecological Model

From the 1980s to 2000s, scholars from across disciplines (e.g., Rhetoric, Writing Studies, Gender Studies, and Philosophy) further problematized models of the rhetorical situation that

- implied communication is a simple process of transmitting a message, information, from sender to receiver

- portrayed rhetorical situations as “unique, unconnected with other situations” (Cooper, p. 367).

- oversimplified ways interpretation is an act of imagination, a social construction.

By the close of the 20th century, thanks to postmodernism , constructivism , and feminism , the discipline of Writing Studies embraced a new theory of the rhetorical situation: the ecological model.

The ecological model conceptualizes the rhetorical situation as composed of a universe of variables that interact with one another, rhetors, and audiences. Thus, rather than conceptualizing the rhetorical situation as a one-to-one dialog between the writer and the writer’s audience, the ecological model attempts to conceptualize the rhetorical situation with greater complexity–i.e., as a milieu of rhetorical elements that occur in a multi-dimensional space.

First introduced to Writing Studies by Greg Myers (1985) and then developed by Marilyn Cooper (1986), the ecological model of the rhetorical situation assumes “writing is an activity through which a person is continually engaged with a variety of socially constituted systems” Cooper p. 367).

“The metaphor for writing suggested by the ecological model is that of a web, in which anything that affects one strand of the web vibrates throughout the whole” (Cooper p, 370).

Rather than debate either the situation invokes the rhetoric or the writer/speaker invokes the rhetoric, the ecological view assumes both the rhetor and the sociocultural context are in dialog, in co-creation with one another:

“all organisms–but especially human beings-are not simply the results but are also the causes of their own environments. . . . While it may be true that at some instant the environment poses a problem or challenge to the organism, in the process of response to that challenge the organism alters the terms of its relation to the outer world and recreates the relevant aspects of that world. The relation between organism and environment is not simply one of interaction of internal and external factors, but of a dialectical development of organism and milieu in response to each other. (Lewontin et al ., p. 275)

The Psychological Model

In psychology, the STEM community, and the learning sciences, investigators explore the role of mindset and personality on interpretation , creativity, and composing .

For example, research has found that people’s mindset about their competencies as writers and public speakers influence how they interact with rhetorical situations. People who hold a growth mindset about their potential as writers and communicators are more likely than people who hold a fixed mindset to engage in rhetorical analysis and rhetorical reasoning . Being preoccupied with negative thoughts when composing makes writing aversive.

Being intellectually open is crucial to putting aside one’s own perspective and living in the shoes of the Other . Being narrow minded about a topic undermines efforts at research, rhetorical analysis and rhetorical reasoning . Being able to engage in metacognition & self-regulation is crucial to successfully navigating rhetorical contexts. We all don’t know what we don’t know. That’s unavoidable, that’s human. However, openness , metacognition and regulation are needed to question how our own experiences and observations shape our interpretations, research methods , and knowledge claims.

So, on the Topic of the Rhetorical Situation, What’s Next?

Moving forward, as bots emerge, as Artificial Intelligence reaches consciousness, technorhetoricians are beginning to explore ways nonhuman elements enter the communication situation and assert agency.

Bitzer, Lloyd. (1968). “The Rhetorical Situation.” Philosophy and Rhetoric 1:1: 1-14.

Gendlin, Eugene T (1978). “Befindlichkeit: Heidegger and the philosophy of psychology” (PDF) . Review of Existential Psychology and Psychiatry . 16 (1–3): 43–71.

Lewontin, R. C., Steven Rose, and Leon J. Kamin. Not in Our Genes: Biology, Ideology, and Human Nature. New York: Pantheon Books, 1984.

Marilyn M. Cooper College English , Vol. 48, No. 4 (Apr., 1986), pp. 364-375

Myers, Greg. “The Social Construction of Two Biologists’ Proposals.” Written Communication 2 (1985): 219-45.

Vatz, Richard (1973). “The Myth of the Rhetorical Situation.” Philosophy & Rhetoric 6:3: 154-161.

Related Articles:

Audience - Audience Awareness

Medium, media.

Occasion, Exigency, Kairos - How to Decode Meaning-Making Practices

Perspective - What is the Role of Perspective in Reading & Writing?

Purpose - Aim of Discourse - Intention

Subject, topic.

Text - Composition

Writer, speaker, knowledge worker . . ., suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Joseph M. Moxley

If your text doesn’t appeal to your audience, then all is lost. Awareness of your audience (as well as purpose and context) is crucial to writing well. Learn how to...

Medium refer to the materials and tools Rhetors use to compose, archive, and convey messages. For 21st Century Writers, messages often have to be remediated in multiple media.

This article explores ‘perspective’ in interpretation, reasoning, and composition. It questions how a reader’s or writer’s background — personal experiences, cultural and academic influences, and their chosen viewpoint — shapes...

What is purpose? How does purpose shape the processes? When composing, how can I best identify and express my purpose?

Learn to analyze the register of a communication situation so you know when you need to code switch. Use register as a measure of audience awareness and clarity in communication....

“Text,” traditionally associated with printed materials, has evolved to encapsulate anything that conveys symbolic meaning – signifying that in the lens of modern semiotics, the world is a text. Texts...

Writers, Speakers, Knowledge Workers . . . are authors. They may also be called called actors, artists, creators, investigators, knowledge makers, researchers, rhetors, senders.

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority – How to Establish Credibility in Speech & Writing

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

What is the Rhetorical Situation?

A key component of rhetorical analysis involves thinking carefully about the “rhetorical situation” of a text. You can think of the rhetorical situation as the context or set of circumstances out of which a text arises. Any time anyone is trying to make an argument, one is doing so out of a particular context, one that influences and shapes the argument that is made. When we do a rhetorical analysis, we look carefully at how the rhetorical situation (context) shapes the rhetorical act (the text).

We can understand the concept of a rhetorical situation if we examine it piece by piece, by looking carefully at the rhetorical concepts from which it is built. The philosopher Aristotle organized these concepts as the author, audience, setting, purpose, and text. Answering the questions about these rhetorical concepts below will give you a good sense of your text’s rhetorical situation – the starting point for rhetorical analysis.

We will use the example of President Trump’s inaugural address (the text) to sift through these questions about the rhetorical situation (context).

The “author” of a text is the creator – the person who is communicating to try to effect a change in his or her audience. An author doesn’t have to be a single person or a person at all – an author could be an organization. To understand the rhetorical situation of a text, one must examine the identity of the author and his or her background.

- What kind of experience or authority does the author have in the subject he or she is speaking about?

- What values does the author have, either in general or about this particular subject?

- How invested is the author in the topic of the text? In other words, what affects the author’s perspective on the topic?

In any text, an author is attempting to engage an audience. Before we can analyze how effectively an author engages an audience, we must spend some time thinking about that audience. An audience is any person or group who is the intended recipient of the text and also the person/people the author is trying to influence. To understand the rhetorical situation of a text, one must examine who the intended audience is by thinking about these things:

- Sometimes this is the hardest question of all. We can get this information of “who is the author addressing” by looking at where an article is published. Pay attention to the newspaper, magazine, website, or journal title where the text is published. Often, you can research that publication to get a good sense of who reads that publication.

- What is the audience’s demographic information (age, gender, etc.)?

- What is/are the background, values, and interests of the intended audience?

- How open is this intended audience to the author?

- What assumptions might the audience make about the author?

- In what context is the audience receiving the text?

Thinking about the audience can be a bit tricky. Your audience is the person or group that you intend to reach with your writing. We sometimes call this the intended audience – the group of people to whom a text is intentionally directed. But any text likely also has an unintended audience, a reader (or readers) who read it even without being the intended recipient. The reader might be the person you have in mind as you write, the audience you’re trying to reach, but they might be some random person you’ve never thought of a day in your life. You can’t always know much about random readers, but you should have some understanding of who your audience is. It’s the audience that you want to focus on as you shape your message.

Nothing happens in a vacuum, and that includes the creation of any text. Essays, speeches, photos, political ads, etc. were written in a specific time and/or place, all of which can affect the way the text communicates its message. To understand the rhetorical situation of a text, we can identify the particular occasion or event that prompted the text’s creation at the particular time it was created.

- Was there a debate about the topic that the author of the text addresses? If so, what are (or were) the various perspectives within that debate?

- Did something specific occur that motivated the author to speak out?

The purpose of a text blend the author with the setting and the audience. Looking at a text’s purpose means looking at the author’s motivations for creating it. The author has decided to start a conversation or join one that is already underway. Why has he or she decided to join in? In any text, the author may be trying to inform, to convince, to define, to announce, or to activate. Can you tell which one of those general purposes your author has?

- What is the author hoping to achieve with this text?

- Why did the author decide to join the “conversation” about the topic?

- What does the author want from their audience? What does the author want the audience to do once the text is communicated?

In what format or medium is the text being made: image? written essay? speech? song? protest sign? meme? sculpture?

- What is gained by having a text composed in a particular format/medium?

- What limitations does that format/medium have?

- What opportunities for expression does that format/medium have (that perhaps other formats do not have?)

Attributions

A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing by Melanie Gagich & Emilie Zickel is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

What is the Rhetorical Situation? Copyright © by James Charles Devlin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

III. Rhetorical Situation

3.3 What is the Rhetorical Situation?

Robin Jeffrey; Emilie Zickel; and Terri Pantuso

A key component of rhetorical analysis involves thinking carefully about the rhetorical situation of a text. You can think of the rhetorical situation as the context or set of circumstances out of which a text arises. Any time anyone is trying to make an argument, one is doing so out of a particular context, one that influences and shapes the argument that is being made. When we do a rhetorical analysis, we look carefully at how the rhetorical situation (context) shapes the rhetorical act (the text).

We can understand the concept of a rhetorical situation if we examine it piece by piece, by looking carefully at the rhetorical concepts from which it is built. The philosopher Aristotle organized these concepts as author, audience, setting, purpose, and text. Answering the questions about these rhetorical concepts below will give you a good sense of your text’s rhetorical situation – the starting point for rhetorical analysis.

We will use the example of Kamala Harris’s vice presidential acceptance speech (the text) delivered November 7, 2020 to sift through these questions about the rhetorical situation (context). [1]

The author of a text is the creator – the person who is communicating in order to try to effect a change in their audience. An author doesn’t have to be a single person or a person at all – an author could be an organization. To understand the rhetorical situation of a text, one must examine the identity of the author and their background.

- What kind of experience or authority does the author have in the subject about which they are speaking?

- What values does the author have, either in general or with regard to this particular subject?

- How invested is the author in the topic of the text? In other words, what affects the author’s perspective on the topic?

Example of Author Analysis for the Rhetorical Situation (Kamala Harris’s VP Acceptance Speech)

At the time she delivered this speech, Kamala Harris was a first-term vice-presidential nominee, a former US Senator, former Attorney General of California, and the first woman ever elected to the second highest office in the country. Ethnically, Harris identifies as both African American and South Asian American. She became the first person of color, and first woman, to be elected to the office of Vice President. Her political affiliation is with the Democratic party – the liberal political party in America.

In any text, an author is attempting to engage an audience. Before we can analyze how effectively an author engages an audience, we must spend some time thinking about that audience. An audience is any person or group who is the intended recipient of the text and also the person/people the author is trying to influence. To understand the rhetorical situation of a text, one must examine who the intended audience is by thinking about these things:

- Who is the author addressing? Sometimes this is the hardest question of all. We can get this information of who the author is addressing by looking at where an article is published. Be sure to pay attention to the newspaper, magazine, website, or journal title where the text is published. Often, you can research that publication to get a good sense of who reads it.

- What is the audience’s demographic information (age, gender, etc.)?

- What is/are the background, values, interests of the intended audience?

- How open is this intended audience to the author?

- What assumptions might the audience make about the author?

- In what context is the audience receiving the text?

Example of Audience Analysis for the Rhetorical Situation (Kamala Harris’s VP Acceptance Speech)

Harris was addressing the American people (and the world) at-large; since her acceptance speech was broadcast on major news networks and the internet, she was speaking to people of all ethnicities, genders, religions, nationalities. Harris was the VP candidate for Joe Biden. Biden’s election was contested by the incumbent , Donald Trump, and this contributed to tension already present among the country that was enduring a global pandemic. Members of the intended audience included health care workers, first responders, poll workers, etc., as well as women of all ages and demographics. While much of the intended audience was receptive to Harris’s speech and the significance of her election, a portion of the audience was in disbelief and felt that the election was fraudulent . Given this tension, some audience members might assume that Harris was not legally elected and therefore would not represent them. Some audience members might assume that her gender would impact her ability to perform the duties of her office, while others might assume that Harris would be a conduit for change in the country.

Nothing happens in a vacuum, and that includes the creation of any text. Essays, speeches, photos, political ads – any text – was written in a specific time and/or place, all of which can affect the way the text communicates its message. To understand the rhetorical situation of a text, we can identify the particular occasion or event that prompted the text’s creation at the particular time it was created. When considering the setting in terms of rhetorical analysis, consider the following:

- Was there a debate about the topic that the author of the text addresses? If so, what are (or were) the various perspectives within that debate?

- Did something specific occur that motivated the author to speak out?

Example of Setting Analysis for the Rhetorical Situation (Kamala Harris’s VP Acceptance Speech)

The occasion of Kamala Harris giving this speech was the confirmation that Joe Biden had won enough electoral college votes to be considered the winner of the election. While it is customary for the President-elect to make an acceptance speech, it is less common for a Vice-President-elect to do so. However, given the historical significance of Harris’s election, millions of people wanted to hear from her.

The purpose of a text blends the author with the setting and the audience. Looking at a text’s purpose means looking at the author’s motivations for creating it. The author has decided to start a conversation or join one that is already underway. Why have they decided to join in? In any text, the author may be trying to inform, to convince, to define, to announce, or to activate a debate or discussion. When determining rhetorical purpose, consider the following in regard to the author:

- What is the author hoping to achieve with this text?

- Why did the author decide to join the conversation about the topic?

- What does the author want from their audience? What does the author want the audience to do once the text is communicated?

Harris’s purpose in this speech was to set the tone for the Biden presidency, to acknowledge the hardships many had been enduring, and to attempt to unite the country and prepare it for moving forward with peaceful acceptance.

When analyzing the rhetorical situation of a given text, it is important to consider the format, or medium, in which the text is being made. If you are analyzing an image for rhetorical context, elements such as shading, color, and placement are part of the argument being presented. Other forms of media that a text might take include a written essay, speech, song, protest sign, meme, or sculpture. When examining the rhetorical situation of a text’s medium, ask yourself the following:

- What is gained by having a text composed in a particular format/medium?

- What limitations does that format/medium have?

- What opportunities for expression does that format/medium have (that perhaps other formats do not have?)

Example of Text Analysis for the Rhetorical Situation (Kamala Harris’s VP Acceptance Speech)

Acceptance speeches are intended to celebrate victories while uniting across political lines. While the tone may be formal, oftentimes candidates use this opportunity to express gratitude. Given that they are broadcast internationally, there are two ways to examine the text: the written form and the spoken word.

A Note About Audience

What is the difference between an audience and a reader? Thinking about audience can be a bit tricky. Your audience is the person or group that you intend to reach with your writing. We sometimes call this the intended audience – the group of people to whom a text is intentionally directed. But any text likely also has an unintended audience, a reader (or readers) who read it even without being the intended recipient. The reader might be the person you have in mind as you write, the audience you’re trying to reach, but they might be some random person you’ve never thought of a day in your life. You can’t always know much about random readers, but you should have some understanding of who your audience is. It’s the audience that you want to focus on as you shape your message.

This section contains material from:

Jeffrey, Robin, and Emilie Zickel. “What is the Rhetorical Situation?” In A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing , by Melanie Gagich and Emilie Zickel. Cleveland: MSL Academic Endeavors. Accessed July 2019. https://pressbooks.ulib.csuohio.edu/csu-fyw-rhetoric/chapter/rhetorical-situation-the-context/ . Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

OER credited in the text above include:

Burnell, Carol, Jaime Wood, Monique Babin, Susan Pesznecker, and Nicole Rosevear. The Word on College Reading and Writing . Open Oregon Educational Resources. Accessed December 18, 2020. https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/wrd/ . Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License .

Jeffrey, Robin. About Writing: A Guide . Portland, OR: Open Oregon Educational Resources. Accessed December 18, 2020. https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/aboutwriting/ . Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

- Kamala Harris, “Vice Presidential Acceptance Speech,” speech, Wilmington, Delaware, November 7, 2020, in “Read Kamala Harris’s Vice President-Elect Acceptance Speech,” by Matt Stevens, New York Times , November 8, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/article/watch-kamala-harris-speech-video-transcript.html ↵

A classical Greek philosopher and orator who lived from 384-322 B.C. A student of Plato, he is known for creating his own branch of philosophy known as Aristotelianism which is based on the use of inductive reasoning and deductive logic in order to study nature and natural law. Aristotle also wrote on various subjects including biology, physics, ethics, poetry, politics, linguistics, mathematics, and rhetoric. Aristotle’s rhetorical triangle is based on ethos, pathos, and logos and is considered the basis for understanding the rhetorical situation.

To occupy or attract the attention of someone or something.

A receiver or beneficiary.

Taking something for granted; an expected result; to be predisposed towards a certain outcome.

The set of circumstances that frame a particular idea or argument; the background information that is necessary for an audience to know about in order to understand why or how a text was written or produced.

The person who currently holds an office or position. The term is usually associated with political office.

Involving deception, dishonesty, or duplicity.

Someone or something that allows something tangible, such as money, or intangible, such as ideas, to go from one place to another; can also indirectly refer to a catalyst for change.

3.3 What is the Rhetorical Situation? Copyright © 2022 by Robin Jeffrey; Emilie Zickel; and Terri Pantuso is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Writing Center

- Current Students

- Online Only Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Parents & Family

- Alumni & Friends

- Community & Business

- Student Life

- Video Introduction

- Become a Writing Assistant

- All Writers

- Graduate Students

- ELL Students

- Campus and Community

- Testimonials

- Encouraging Writing Center Use

- Incentives and Requirements

- Open Educational Resources

- How We Help

- Get to Know Us

- Conversation Partners Program

- Workshop Series

- Professors Talk Writing

- Computer Lab

- Starting a Writing Center

- A Note to Instructors

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review

- Research Proposal

- Argument Essay

Rhetorical Analysis

Almost every text makes an argument. Rhetorical analysis is the process of evaluating elements of a text and determining how those elements impact the success or failure of that argument. Often rhetorical analyses address written arguments, but visual, oral, or other kinds of “texts” can also be analyzed.

Rhetorical Features—What to Analyze

Asking the right questions about how a text is constructed will help you determine the focus of your rhetorical analysis. A good rhetorical analysis does not try to address every element of a text; discuss just those aspects with the greatest [positive or negative] impact on the text’s effectiveness.

The Rhetorical Situation

Remember that no text exists in a vacuum. The rhetorical situation of a text refers to the context in which it is written and read, the audience to whom it is directed, and the purpose of the writer.

The Rhetorical Appeals

A writer makes many strategic decisions when attempting to persuade an audience. Considering the following rhetorical appeals will help you understand some of these strategies and their effect on an argument. Generally, writers should incorporate a variety of different rhetorical appeals rather than relying on only one kind.

Ethos (appeal to the writer’s credibility)

- What is the writer’s purpose (to argue, explain, teach, defend, call to action, etc.)?

- Do you trust the writer? Why?

- Is the writer an authority on the subject? What credentials does the writer have?

- Does the writer address other viewpoints?

- How does the writer’s word choice or tone affect how you view the writer?

Pathos (appeal to emotion or to an audience’s values or beliefs)

- Who is the target audience for the argument?

- How is the writer trying to make the audience feel (i.e., sad, happy, angry, guilty)?

- Is the writer making any assumptions about the background, knowledge, values, etc. of the audience?

Logos (appeal to logic)

- Is the writer’s evidence relevant to the purpose of the argument? Is the evidence current (if applicable)? Does the writer use a variety of sources to support the argument?

- What kind of evidence is used (i.e., expert testimony, statistics, proven facts)?

- Do the writer’s points build logically upon each other?

- Where in the text is the main argument stated? How does that placement affect the success of the argument?

- Does the writer’s thesis make that purpose clear?

Kairos (appeal to timeliness)

- When was the argument originally presented?

- Where was the argument originally presented?

- What circumstances may have motivated the argument?

- Does the particular time or situation in which this text is written make it more compelling or persuasive?

- What would an audience at this particular time understand about this argument?

Writing a Rhetorical Analysis Essay

No matter the kind of text you are analyzing, remember that the text’s subject matter is never the focus of a rhetorical analysis. The most common error writers make when writing rhetorical analyses is to address the topic or opinion expressed by an author instead of focusing on how that author constructs an argument.

You must read and study a text critically in order to distinguish its rhetorical elements and strategies from its content or message. By identifying and understanding how audiences are persuaded, you become more proficient at constructing your own arguments and in resisting faulty arguments made by others.

A thesis for a rhetorical analysis does not address the content of the writer’s argument. Instead, the thesis should be a statement about specific rhetorical strategies the writer uses and whether or not they make a convincing argument.

Incorrect: Smith’s editorial promotes the establishment of more green space in the Atlanta area through the planting of more trees along major roads.

This statement is summarizing the meaning and purpose of Smith’s writing rather than making an argument about how – and how effectively – Smith presents and defends his position.

Correct: Through the use of vivid description and testimony from affected citizens, Smith makes a powerful argument for establishing more green space in the Atlanta area.

Correct: Although Smith’s editorial includes vivid descriptions of the destruction of green space in the Atlanta area, his argument will not convince his readers because his claim is not backed up with factual evidence.

These statements are both focused on how Smith argues, and both make a claim about the effectiveness of his argument that can be defended throughout the paper with examples from Smith’s text.

Introduction

The introduction should name the author and the title of the work you are analyzing. Providing any relevant background information about the text and state your thesis (see above). Resist the urge to delve into the topic of the text and stay focused on the rhetorical strategies being used.

Summary of argument

Include a short summary of the argument you are analyzing so readers not familiar with the text can understand your claims and have context for the examples you provide.

The body of your essay discusses and evaluates the rhetorical strategies (elements of the rhetorical situation and rhetorical appeals – see above) that make the argument effective or not. Be certain to provide specific examples from the text for each strategy you discuss and focus on those strategies that are most important to the text you are analyzing. Your essay should follow a logical organization plan that your reader can easily follow.

Go beyond restating your thesis; comment on the effect or significance of the entire essay. Make a statement about how important rhetorical strategies are in determining the effectiveness of an argument or text.

Analyzing Visual Arguments

The same rhetorical elements and appeals used to analyze written texts also apply to visual arguments. Additionally, analyzing a visual text requires an understanding of how design elements work together to create certain persuasive effects (or not). Consider how elements such as image selection, color, use of space, graphics, layout, or typeface influence an audience’s reaction to the argument that the visual was designed to convey.

This material was developed by the KSU Writing Center and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License . All materials created by the KSU Writing Center are free to use and can be adopted, remixed, and shared at will as long as the materials are attributed. Please keep this information on materials you adapt or adopt for attribution purposes.

Contact Info

Kennesaw Campus 1000 Chastain Road Kennesaw, GA 30144

Marietta Campus 1100 South Marietta Pkwy Marietta, GA 30060

Campus Maps

Phone 470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

kennesaw.edu/info

Media Resources

Resources For

Related Links

- Financial Aid

- Degrees, Majors & Programs

- Job Opportunities

- Campus Security

- Global Education

- Sustainability

- Accessibility

470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

© 2024 Kennesaw State University. All Rights Reserved.

- Privacy Statement

- Accreditation

- Emergency Information

- Reporting Hotline

- Open Records

- Human Trafficking Notice

9.5 Writing Process: Thinking Critically about Rhetoric

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Develop a rhetorical analysis through multiple drafts.

- Identify and analyze rhetorical strategies in a rhetorical analysis.

- Demonstrate flexible strategies for generating ideas, drafting, reviewing, collaborating, revising, rewriting, and editing.

- Give and act on productive feedback for works in progress.

The ability to think critically about rhetoric is a skill you will use in many of your classes, in your work, and in your life to gain insight from the way a text is written and organized. You will often be asked to explain or to express an opinion about what someone else has communicated and how that person has done so, especially if you take an active interest in politics and government. Like Eliana Evans in the previous section, you will develop similar analyses of written works to help others understand how a writer or speaker may be trying to reach them.

Summary of Assignment: Rhetorical Analysis

The assignment is to write a rhetorical analysis of a piece of persuasive writing. It can be an editorial, a movie or book review, an essay, a chapter in a book, or a letter to the editor. For your rhetorical analysis, you will need to consider the rhetorical situation—subject, author, purpose, context, audience, and culture—and the strategies the author uses in creating the argument. Back up all your claims with evidence from the text. In preparing your analysis, consider these questions:

- What is the subject? Be sure to distinguish what the piece is about.

- Who is the writer, and what do you know about them? Be sure you know whether the writer is considered objective or has a particular agenda.

- Who are the readers? What do you know or what can you find out about them as the particular audience to be addressed at this moment?

- What is the purpose or aim of this work? What does the author hope to achieve?

- What are the time/space/place considerations and influences of the writer? What can you know about the writer and the full context in which they are writing?

- What specific techniques has the writer used to make their points? Are these techniques successful, unsuccessful, or questionable?

For this assignment, read the following opinion piece by Octavio Peterson, printed in his local newspaper. You may choose it as the text you will analyze, continuing the analysis on your own, or you may refer to it as a sample as you work on another text of your choosing. Your instructor may suggest presidential or other political speeches, which make good subjects for rhetorical analysis.

When you have read the piece by Peterson advocating for the need to continue teaching foreign languages in schools, reflect carefully on the impact the letter has had on you. You are not expected to agree or disagree with it. Instead, focus on the rhetoric—the way Peterson uses language to make his point and convince you of the validity of his argument.

Another Lens. Consider presenting your rhetorical analysis in a multimodal format. Use a blogging site or platform such as WordPress or Tumblr to explore the blogging genre, which includes video clips, images, hyperlinks, and other media to further your discussion. Because this genre is less formal than written text, your tone can be conversational. However, you still will be required to provide the same kind of analysis that you would in a traditional essay. The same materials will be at your disposal for making appeals to persuade your readers. Rhetorical analysis in a blog may be a new forum for the exchange of ideas that retains the basics of more formal communication. When you have completed your work, share it with a small group or the rest of the class. See Multimodal and Online Writing: Creative Interaction between Text and Image for more about creating a multimodal composition.

Quick Launch: Start with a Thesis Statement

After you have read this opinion piece, or another of your choice, several times and have a clear understanding of it as a piece of rhetoric, consider whether the writer has succeeded in being persuasive. You might find that in some ways they have and in others they have not. Then, with a clear understanding of your purpose—to analyze how the writer seeks to persuade—you can start framing a thesis statement : a declarative sentence that states the topic, the angle you are taking, and the aspects of the topic the rest of the paper will support.

Complete the following sentence frames as you prepare to start:

- The subject of my rhetorical analysis is ________.

- My goal is to ________, not necessarily to ________.

- The writer’s main point is ________.

- I believe the writer has succeeded (or not) because ________.

- I believe the writer has succeeded in ________ (name the part or parts) but not in ________ (name the part or parts).

- The writer’s strongest (or weakest) point is ________, which they present by ________.

Drafting: Text Evidence and Analysis of Effect

As you begin to draft your rhetorical analysis, remember that you are giving your opinion on the author’s use of language. For example, Peterson has made a decision about the teaching of foreign languages, something readers of the newspaper might have different views on. In other words, there is room for debate and persuasion.

The context of the situation in which Peterson finds himself may well be more complex than he discusses. In the same way, the context of the piece you choose to analyze may also be more complex. For example, perhaps Greendale is facing an economic crisis and must pare its budget for educational spending and public works. It’s also possible that elected officials have made budget cuts for education a part of their platform or that school buildings have been found obsolete for safety measures. On the other hand, maybe a foreign company will come to town only if more Spanish speakers can be found locally. These factors would play a part in a real situation, and rhetoric would reflect that. If applicable, consider such possibilities regarding the subject of your analysis. Here, however, these factors are unknown and thus do not enter into the analysis.

Introduction

One effective way to begin a rhetorical analysis is by using an anecdote, as Eliana Evans has done. For a rhetorical analysis of the opinion piece, a writer might consider an anecdote about a person who was in a situation in which knowing another language was important or not important. If they begin with an anecdote, the next part of the introduction should contain the following information:

- Author’s name and position, or other qualification to establish ethos

- Title of work and genre

- Author’s thesis statement or stance taken (“Peterson argues that . . .”)

- Brief introductory explanation of how the author develops and supports the thesis or stance

- If relevant, a brief summary of context and culture

Once the context and situation for the analysis are clear, move directly to your thesis statement. In this case, your thesis statement will be your opinion of how successful the author has been in achieving the established goal through the use of rhetorical strategies. Read the sentences in Table 9.1 , and decide which would make the best thesis statement. Explain your reasoning in the right-hand column of this or a similar chart.

The introductory paragraph or paragraphs should serve to move the reader into the body of the analysis and signal what will follow.

Your next step is to start supporting your thesis statement—that is, how Octavio Peterson, or the writer of your choice, does or does not succeed in persuading readers. To accomplish this purpose, you need to look closely at the rhetorical strategies the writer uses.

First, list the rhetorical strategies you notice while reading the text, and note where they appear. Keep in mind that you do not need to include every strategy the text contains, only those essential ones that emphasize or support the central argument and those that may seem fallacious. You may add other strategies as well. The first example in Table 9.2 has been filled in.