Home — Essay Samples — Law, Crime & Punishment — 2Nd Amendment — The Two Sides of the 2nd Amendment

The Two Sides of The 2nd Amendment

- Categories: 2Nd Amendment

About this sample

Words: 1740 |

Published: Sep 1, 2020

Words: 1740 | Pages: 4 | 9 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Law, Crime & Punishment

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1132 words

2 pages / 1103 words

6 pages / 3292 words

3 pages / 1488 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on 2Nd Amendment

First off let's start off with why the Left (Democrats, Progressives, Socialists, Communists) want to have very strict and or common sense gun laws. The Left wants gun laws because they think gun laws actually work they think [...]

The Second Amendment of the United States Constitution guarantees the right of citizens to keep and bear arms. In recent times, this amendment has become a controversial topic for debate. Some people argue that the Second [...]

Although the 2nd Amendment is only 27 words in its entirety, it has been the focus of controversy many times in the last 223 years. In 1791 when the second amendment was added to the bill of rights America did not have a well [...]

The issue of gun control came to worldwide attention when school and mass shooting started to happen more often and became a problem. The citizens of the United States keep coming back to the idea of repealing the Second [...]

Few topics provide more polarising opinions and heated debates than the topic of gun control in the USA. Established in December 1791, the second amendment states: ‘A well-regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a [...]

With different interpretations of the Second Amendment, as well as different opinions on it whether people want to support it or abolish it can come different questions on why it became an Amendment especially the second of [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Campus News

- Campus Events

- Devotionals and Forums

- Readers’ Forum

- Education Week

- Breaking News

- Police Beat

- Video of the Day

- Current Issue

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- The Daily Universe Magazine, December 2022

- The Daily Universe, November 2022

- The Daily Universe Magazine, October 2022

- The Daily Universe Magazine, September 2022 (Black 14)

- The Daily Universe Magazine, March 2022

- The Daily Universe Magazine, February 2022

- The Daily Universe Magazine, January 2022

- December 2021

- The Daily Universe Magazine, November 2021

- The Daily Universe, October 2021

- The Daily Universe Magazine, September 2021

- Hope for Lahaina: Witnesses of the Maui Wildfires

- Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial

- The Black 14: Healing Hearts and Feeding Souls

- Camino de Santiago

- A Poor Wayfaring Man

- Palmyra: 200 years after Moroni’s visits

- The Next Normal

- Called to Serve In A Pandemic

- The World Meets Our Campus

- Defining Moments of BYU Sports

- If Any of You Lack Wisdom

The ‘scope’ of the argument: Why the Second Amendment matters

The U.S. Constitution’s guarantee of the right to bear arms has been a primary conversation topic among Americans in 2020. As uncertainty and fear have plagued the world over the last eight months, there has been a surge in gun sales nationwide — many of them to first-time owners.

Austin and Danielle, one young couple in Utah, had always talked about owning a firearm. Austin grew up in a city where gun ownership was less common, but Danielle grew up in a small town where gun ownership was normal. They both said the events of 2020 lead them to buy a firearm.

“We always talked about having a gun,” Austin said. “I thought they were probably important to have for self-defense. Once COVID-19 hit , it made getting one feel like an important purchase to make.”

The couple bought their gun in early April. While they believe in gun ownership, they wanted to keep their last name anonymous to avoid the negative stigma some associate with gun owners.

“I feel like a lot of people have a mental image of gun owners as uneducated or having low IQs,” Danielle said. “I do feel like most gun owners are responsible and only want them for recreation and self-defense purposes, but some people think they are hillbillies.”

The two cited the case of the Orem wildfires in mid-October, which were caused by target practice at a local gun range. They also mentioned a few other reasons they didn’t want to be labeled as “gun owners.”

“We wanted to remain anonymous because we didn’t want to be targeted for our political beliefs or because we choose to own a gun,” Austin said. “Remaining anonymous is a safe choice. That’s the reason I bought a gun — it’s something to protect my family and keep us safe.”

While some Americans have sought to restrict gun ownership, for many others it is a cherished right they work to protect. According to The New York Times , demand for guns has surged since the start of the pandemic in March and hasn’t let up all year. The National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) recorded an estimated 28 million background checks were requested from January to the end of September.

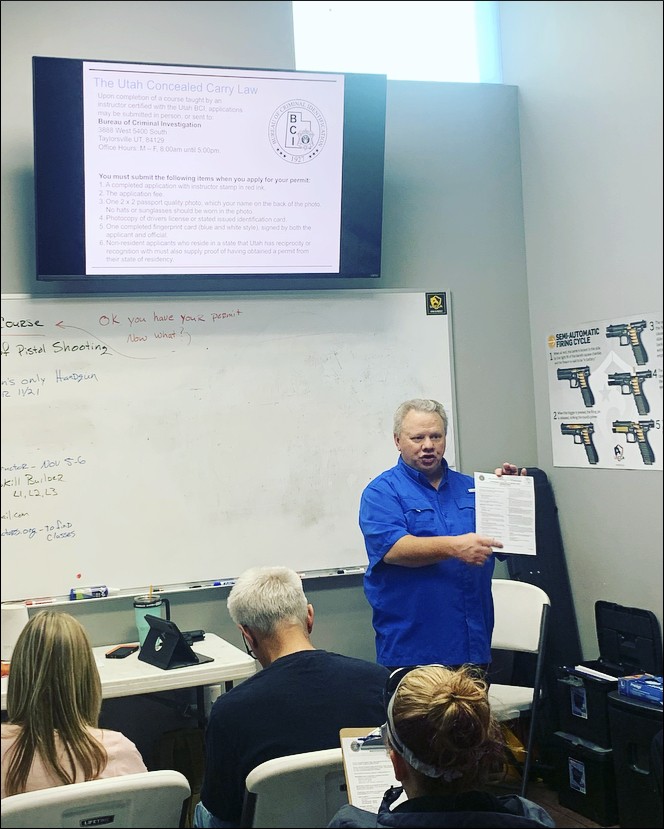

Jeffrey Denning, a Salt Lake City Police detective, teaches firearm safety classes to private parties. He has seen a dramatic increase in people wanting to exercise their Second Amendment rights.

“One gun store owner I talked to said the day after the Utah earthquake on March 13th, he received the most sales he had ever gotten,” Denning said. “After that, sales started going through the roof. The numbers are off the charts.”

According to the data reported by the NICS, the first spike (3.7 million background checks) in firearm demand happened in March likely because of the pandemic. The second spike (3.9 million background checks) was larger and occurred in June — right after acts of civil unrest began in major American cities.

“ People should be able to protect themselves individually and collectively,” Denning said. “We should be able to preserve our freedoms — this lets us have agency and a land of liberty.”

Denning said that while firearms are certainly good for personal protection, the reason the Second Amendment is considered a right is more complex than that.

“The Second Amendment was included in the Constitution so the government could not take over,” Denning said. “It’s to serve against government encroachments. The amendments were developed because of what the founding fathers saw in other parts of the world.”

Most historians agree that this was the premise of the Second Amendment. But some people have grown increasingly wary of the potential dangers of an armed population. Because of this fear, there has been heated debate in recent years over whether to update or reform the Second Amendment.

Lucy Williams, an assistant professor of political philosophy, said the conflict was most pronounced in the 2008 Supreme Court case D.C. v. Heller.

“For some time, there was a debate about whether the prefatory clause ‘A well-regulated Militia being necessary to the security of a free State’ was intended to limit the right to bear arms or if it merely explained why the right is important,” Williams said. “The debate is now largely settled.”

Williams said reformers proposed that the Constitution only protects a right to bear arms in relation to military service. People who took the other position argued the right was not connected to military service. The Supreme Court sided with the latter position.

After this Supreme Court decision, it seems that the debate has shifted. Instead of asking whether individuals should be allowed to have firearms, the debate is focused on whether the government has the ability to regulate and restrict specific weapons from entering the public sphere.

This threat of potential regulation has made some Americans nervous, and conservative politicians say the Second Amendment is under attack, or will be eliminated because of their political opponents. Williams said this is not likely.

“Although the scope of (the Second Amendment) may change, it’s hard to imagine that the right could ever be eliminated entirely,” Williams said.

Though reform may happen in the future, more people are making use of their Second Amendment right. Background checks, first-time gun purchases and training classes are increasing in demand. It remains to be seen whether gun sales will trend downward anytime soon.

“If you haven’t had a gun in 70 years, and are only interested in one because you’re scared, there is no reason to buy one now,” Denning said. “You are going to be fine.”

Despite this, Denning said individuals who have considered buying a gun and want to educate themselves should do so.

“It’s ignorant and foolish not to have a plan for preparation and protection,” Denning said. “You can think all day long that something won’t happen ‘here’ or ‘to you’ but if it does, you’re not going to be prepared.”

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Double taps, tourist traps: how to find hiking spots in the era of gatekeeping, building byu’s defense for year two in the big 12, byu life sciences professor encourages students to forge their own paths with god’s help.

Explore the Constitution

- The Constitution

- Read the Full Text

Dive Deeper

Constitution 101 course.

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders' Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

Constitution Daily Blog

- America's Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs.

- Education Overview

Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

Explore our new 15-unit high school curriculum.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

New exhibit

The first amendment, interactive constitution: the second amendment’s meaning.

February 19, 2018 | by NCC Staff

In this essay from the National Constitution Center’s Interactive Constitution project, scholars Nelson Lund and Adam Winkler look at the Second Amendment’s origins and the modern debates about it.

In the Interactive Constitution, scholars from across the legal and philosophical spectrum interact with each other to explore the meaning of each provision of the Constitution. They are selected with guidance from leaders of the American Constitution Society and the Federalist Society—two prominent constitutional law organizations that represent different viewpoints on the Constitution. Pairs of scholars find common ground, writing a joint statement of what they agree upon about that provision’s history and meaning. Then the scholars write individual statements describing their divergent views on that part of the Constitution. For more about the project, go to https://constitutioncenter.org/interactive-constitution

Modern debates about the Second Amendment have focused on whether it protects a private right of individuals to keep and bear arms, or a right that can be exercised only through militia organizations like the National Guard. This question, however, was not even raised until long after the Bill of Rights was adopted.

Many in the Founding generation believed that governments are prone to use soldiers to oppress the people. English history suggested that this risk could be controlled by permitting the government to raise armies (consisting of full-time paid troops) only when needed to fight foreign adversaries. For other purposes, such as responding to sudden invasions or other emergencies, the government could rely on a militia that consisted of ordinary civilians who supplied their own weapons and received some part-time, unpaid military training.

The onset of war does not always allow time to raise and train an army, and the Revolutionary War showed that militia forces could not be relied on for national defense. The Constitutional Convention therefore decided that the federal government should have almost unfettered authority to establish peacetime standing armies and to regulate the militia.

This massive shift of power from the states to the federal government generated one of the chief objections to the proposed Constitution. Anti-Federalists argued that the proposed Constitution would take from the states their principal means of defense against federal usurpation. The Federalists responded that fears of federal oppression were overblown, in part because the American people were armed and would be almost impossible to subdue through military force.

Implicit in the debate between Federalists and Anti-Federalists were two shared assumptions. First, that the proposed new Constitution gave the federal government almost total legal authority over the army and militia. Second, that the federal government should not have any authority at all to disarm the citizenry. They disagreed only about whether an armed populace could adequately deter federal oppression.

The Second Amendment conceded nothing to the Anti-Federalists’ desire to sharply curtail the military power of the federal government, which would have required substantial changes in the original Constitution. Yet the Amendment was easily accepted because of widespread agreement that the federal government should not have the power to infringe the right of the people to keep and bear arms, any more than it should have the power to abridge the freedom of speech or prohibit the free exercise of religion.

Much has changed since 1791. The traditional militia fell into desuetude, and state-based militia organizations were eventually incorporated into the federal military structure. The nation’s military establishment has become enormously more powerful than eighteenth century armies. We still hear political rhetoric about federal tyranny, but most Americans do not fear the nation’s armed forces and virtually no one thinks that an armed populace could defeat those forces in battle. Furthermore, eighteenth century civilians routinely kept at home the very same weapons they would need if called to serve in the militia, while modern soldiers are equipped with weapons that differ significantly from those generally thought appropriate for civilian uses. Civilians no longer expect to use their household weapons for militia duty, although they still keep and bear arms to defend against common criminals (as well as for hunting and other forms of recreation).

The law has also changed. While states in the Founding era regulated guns—blacks were often prohibited from possessing firearms and militia weapons were frequently registered on government rolls—gun laws today are more extensive and controversial. Another important legal development was the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Second Amendment originally applied only to the federal government, leaving the states to regulate weapons as they saw fit. Although there is substantial evidence that the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment was meant to protect the right of individuals to keep and bear arms from infringement by the states, the Supreme Court rejected this interpretation in United States v. Cruikshank (1876).

Until recently, the judiciary treated the Second Amendment almost as a dead letter. In District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), however, the Supreme Court invalidated a federal law that forbade nearly all civilians from possessing handguns in the nation’s capital. A 5–4 majority ruled that the language and history of the Second Amendment showed that it protects a private right of individuals to have arms for their own defense, not a right of the states to maintain a militia.

The dissenters disagreed. They concluded that the Second Amendment protects a nominally individual right, though one that protects only “the right of the people of each of the several States to maintain a well-regulated militia.” They also argued that even if the Second Amendment did protect an individual right to have arms for self-defense, it should be interpreted to allow the government to ban handguns in high-crime urban areas.

Two years later, in McDonald v. City of Chicago (2010), the Court struck down a similar handgun ban at the state level, again by a 5–4 vote. Four Justices relied on judicial precedents under the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause. Justice Thomas rejected those precedents in favor of reliance on the Privileges or Immunities Clause, but all five members of the majority concluded that the Fourteenth Amendment protects against state infringement of the same individual right that is protected from federal infringement by the Second Amendment.

Notwithstanding the lengthy opinions in Heller and McDonald , they technically ruled only that government may not ban the possession of handguns by civilians in their homes. Heller tentatively suggested a list of “presumptively lawful” regulations, including bans on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill, bans on carrying firearms in “sensitive places” such as schools and government buildings, laws restricting the commercial sale of arms, bans on the concealed carry of firearms, and bans on weapons “not typically possessed by law-abiding citizens for lawful purposes.” Many issues remain open, and the lower courts have disagreed with one another about some of them, including important questions involving restrictions on carrying weapons in public.

For more on this subject from our scholars:

The Second Amendment By Nelson Lund and Adam Winkler

More from the National Constitution Center

Constitution 101

Explore our new 15-unit core curriculum with educational videos, primary texts, and more.

Search and browse videos, podcasts, and blog posts on constitutional topics.

Founders’ Library

Discover primary texts and historical documents that span American history and have shaped the American constitutional tradition.

Modal title

Modal body text goes here.

Share with Students

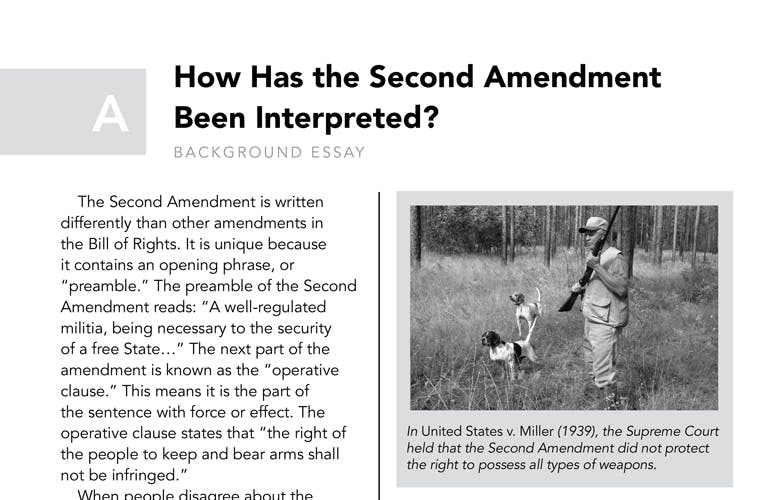

Handout A: How Has the Second Amendment Been Interpreted? (Background Essay)

The Second Amendment is written differently than other amendments in the Bill of Rights. It is unique because it contains an opening phrase, or “preamble.” The preamble of the Second Amendment reads: “A well-regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free State…” The next part of the amendment is known as the “operative clause.” This means it is the part of the sentence with force or effect. The operative clause states that “the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.”

When people disagree about the meaning of the Second Amendment, it is usually because they disagree about the meaning and purpose of the preamble of the Amendment.

How Has the Supreme Court Ruled?

In Presser v. Illinois (1886), the Court held that states could not disarm citizens because that would reduce with the federal government’s ability to raise a militia. But the Court added, “We think it clear that [laws] which…forbid bodies of men to associate together as military organizations, or to drill or parade with arms in cities and towns unless authorized by law, do not infringe the right of the people to keep and bear arms.” The Court also interpreted the word “militia.” They stated that a militia was “all citizens capable of bearing arms.”

In United States v. Miller (1939), the Supreme Court held that the Second Amendment did not protect the right to possess all types of weapons. The Court upheld a federal law that regulated sawed-off shotguns [one type of gun that is easily concealed and often used by criminals].

The Court reasoned that since that type of weapon was not related to keeping up a militia, the Second Amendment did not protect the right to own it. In other words, the Second Amendment protected a right to own weapons. The question was how far that right went.

Why Is District of Columbia v. Heller (2008) Important?

District of Columbia v. Heller (2008) was the first time the Supreme Court interpreted what the Second Amendment meant for an individual’s right to possess weapons for private uses like self defense.

The District of Columbia had one of the strictest gun laws in the country. It included a total ban on handguns. Further, long guns had to be kept unloaded and disassembled or trigger-locked. Heller believed the law made it impossible for him to defend himself in his home. He argued that it violated the Second Amendment.

The District of Columbia argued that the preamble of the Second Amendment, which refers to militia service, secured the “right of the people” to have weapons only in connection with militia service. The city also pointed out that the law did not ban all guns, and that it was a reasonable way to prevent crime.

The Court agreed with Heller and overturned three parts of the District’s law. The Court reasoned that the preamble gave one reason for the amendment, but did not limit the right. The Court also reasoned that elsewhere in the Constitution, like in the First, Fourth, and Ninth Amendments, the phrase “the right of the people” is used only to refer to rights held by people as individuals.

Finally, the Court reasoned that the right to own weapons for self-defense was an “inherent” [natural] right of all people. “It has always been widely understood that the Second Amendment, like the First and Fourth Amendments, codified a preexisting right,” the majority stated.

Four of the nine Supreme Court Justices disagreed with the Court’s ruling. The dissenters agreed that the Second Amendment protected an individual right. However, they argued that an individual’s right to bear arms was limited by the amendment’s preamble. One dissenting Justice argued that the Second Amendment’s preamble showed the Founders’ “single-minded focus” on protecting “military uses of firearms, which they viewed in the context of service in state militias.”

One thing is certain. Like all other rights in the Bill of Rights (such as freedom of speech and press), the right to keep and bear arms is not an absolute right. Working out the limits of the Second Amendment’s protection continues to challenge society.

Comprehension Questions:

- In Presser v. Illinois (1886), what did the Supreme Court decide about militias?

- What are the possible results from the Court’s ruling in United States v. Miller (1939)?

- What did the Supreme Court rule in District of Columbia v. Heller (2008)? How did this change or confirm the interpretation of the Second Amendment?

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Second Amendment

By: History.com Editors

Updated: July 27, 2023 | Original: December 4, 2017

The Second Amendment, often referred to as the right to bear arms, is one of 10 amendments that form the Bill of Rights, ratified in 1791 by the U.S. Congress. Differing interpretations of the amendment have fueled a long-running debate over gun control legislation and the rights of individual citizens to buy, own and carry firearms.

Right to Bear Arms

The text of the Second Amendment reads in full: “A well-regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” The framers of the Bill of Rights adapted the wording of the amendment from nearly identical clauses in some of the original 13 state constitutions.

During the Revolutionary War era, “militia” referred to groups of men who banded together to protect their communities, towns, colonies and eventually states, once the United States declared its independence from Great Britain in 1776.

Many people in America at the time believed governments used soldiers to oppress the people, and thought the federal government should only be allowed to raise armies (with full-time, paid soldiers) when facing foreign adversaries. For all other purposes, they believed, it should turn to part-time militias, or ordinary civilians using their own weapons.

State Militias

But as militias had proved insufficient against the British, the Constitutional Convention gave the new federal government the power to establish a standing army, even in peacetime.

However, opponents of a strong central government (known as Anti-Federalists) argued that this federal army deprived states of their ability to defend themselves against oppression. They feared that Congress might abuse its constitutional power of “organizing, arming and disciplining the Militia” by failing to keep militiamen equipped with adequate arms.

So, shortly after the U.S. Constitution was officially ratified, James Madison proposed the Second Amendment as a way to empower these state militias. While the Second Amendment did not answer the broader Anti-Federalist concern that the federal government had too much power, it did establish the principle (held by both Federalists and their opponents) that the government did not have the authority to disarm citizens.

Well-Regulated Militia

Practically since its ratification, Americans have debated the meaning of the Second Amendment, with vehement arguments being made on both sides.

The crux of the debate is whether the amendment protects the right of private individuals to keep and bear arms, or whether it instead protects a collective right that should be exercised only through formal militia units.

Those who argue it is a collective right point to the “well-regulated Militia” clause in the Second Amendment. They argue that the right to bear arms should be given only to organized groups, like the National Guard, a reserve military force that replaced the state militias after the Civil War .

On the other side are those who argue that the Second Amendment gives all citizens, not just militias, the right to own guns in order to protect themselves. The National Rifle Association (NRA) , founded in 1871, and its supporters have been the most visible proponents of this argument, and have pursued a vigorous campaign against gun control measures at the local, state and federal levels.

Those who support stricter gun control legislation have argued that limits are necessary on gun ownership, including who can own them, where they can be carried and what type of guns should be available for purchase.

Congress passed one of the most high-profile federal gun control efforts, the so-called Brady Bill , in the 1990s, largely thanks to the efforts of former White House Press Secretary James S. Brady, who had been shot in the head during an assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan in 1981.

District of Columbia v. Heller

Since the passage of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act, which mandated background checks for gun purchases from licensed dealers, the debate on gun control has changed dramatically.

This is partially due to the actions of the Supreme Court , which departed from its past stance on the Second Amendment with its verdicts in two major cases, District of Columbia v. Heller (2008) and McDonald v. Chicago (2010).

For a long time, the federal judiciary held the opinion that the Second Amendment remained among the few provisions of the Bill of Rights that did not fall under the due process clause of the 14th Amendment , which would thereby apply its limitations to state governments. For example, in the 1886 case Presser v. Illinois , the Court held that the Second Amendment applied only to the federal government, and did not prohibit state governments from regulating an individual’s ownership or use of guns.

But in its 5-4 decision in District of Columbia v. Heller , which invalidated a federal law barring nearly all civilians from possessing guns in the District of Columbia, the Supreme Court extended Second Amendment protection to individuals in federal (non-state) enclaves.

Writing the majority decision in that case, Justice Antonin Scalia lent the Court’s weight to the idea that the Second Amendment protects the right of individual private gun ownership for self-defense purposes.

McDonald v. Chicago

Two years later, in McDonald v. Chicago , the Supreme Court struck down (also in a 5-4 decision) a similar citywide handgun ban, ruling that the Second Amendment applies to the states as well as to the federal government.

In the majority ruling in that case, Justice Samuel Alito wrote: “Self-defense is a basic right, recognized by many legal systems from ancient times to the present day, and in Heller , we held that individual self-defense is ‘the central component’ of the Second Amendment right.”

Gun Control Debate

The Supreme Court’s narrow rulings in the Heller and McDonald cases left open many key issues in the gun control debate.

In the Heller decision, the Court suggested a list of “presumptively lawful” regulations, including bans on possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill; bans on carrying arms in schools and government buildings; restrictions on gun sales; bans on the concealed carrying of weapons; and generally bans on weapons “not typically possessed by law-abiding citizens for lawful purposes.”

Mass Shootings

Since that verdict, as lower courts battle back and forth on cases involving such restrictions, the public debate over Second Amendment rights and gun control remains very much open, even as mass shootings became an increasingly frequent occurrence in American life.

To take just three examples, the Columbine Shooting , where two teens killed 13 people at Columbine High School, prompted a national gun control debate. The Sandy Hook shooting of 20 children and six staff members at the Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut in 2012 led President Barack Obama and many others to call for tighter background checks and a renewed ban on assault weapons.

And in 2017, the mass shooting at country music concert in Las Vegas in which 60 people died (to date the largest mass shooting in U.S. history, overtaking the 2016 attack on the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Florida ) inspired calls to restrict sales of “bump stocks,” attachments that enable semiautomatic weapons to fire faster.

On the other side of the ongoing debate of gun control measures are the NRA and other gun rights supporters, powerful and vocal groups that views such restrictions as an unacceptable violation of their Second Amendment rights.

Bill of Rights, The Oxford Guide to the United States Government . Jack Rakove, ed. The Annotated U.S. Constitution and Declaration of Independence. Amendment II, National Constitution Center . The Second Amendment and the Right to Bear Arms, LiveScience . Second Amendment, Legal Information Institute .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Second Amendment

Primary tabs.

The Second Amendment of the United States Constitution reads: "A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed."

Such language has created considerable debate regarding the Amendment's intended scope . On the one hand, some believe that the Amendment's phrase "the right of the people to keep and bear Arms" creates an individual constitutional right to possess firearms. Under this "individual right theory," the United States Constitution restricts legislative bodies from prohibiting firearm possession, or at the very least, the Amendment renders prohibitory and restrictive regulation presumptively unconstitutional. On the other hand, some scholars point to the prefatory language "a well regulated Militia" to argue that the Framers intended only to restrict Congress from legislating away a state's right to self-defense. Scholars call this theory "the collective rights theory." A collective rights theory of the Second Amendment asserts that citizens do not have an individual right to possess guns and that local, state, and federal legislative bodies therefore possess the authority to regulate firearms without implicating a constitutional right.

In 1939 the U.S. Supreme Court considered the matter in United States v. Miller , 307 U.S. 174. There, the Court adopted a collective rights approach , determining that Congress could regulate a sawed-off shotgun which moved in interstate commerce under the National Firearms Act of 1934 because the evidence did not suggest that the shotgun "has some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia . . . ." The Court then explained that the Framers included the Second Amendment to ensure the effectiveness of the military.

This precedent stood for nearly 70 years until 2008, when the U.S. Supreme Court revisited the issue in the case of District of Columbia v. Heller , 478 F.3d 370. The plaintiff in Heller challenged the constitutionality of a Washington D.C. law which prohibited the possession of handguns. In a 5-4 decision, the Court struck down the D.C. handgun ban as violative of that right. The Court meticulously detailed the history and tradition of the Second Amendment at the time of the Constitutional Convention and proclaimed that the Second Amendment established an individual right for U.S. citizens to possess firearms. The Court carved out Miller as an exception to the general rule that Americans may possess firearms, claiming that law-abiding citizens cannot use sawed-off shotguns for any law-abiding purpose. Similarly, the Court in dicta stated that firearm regulations would not implicate the Second Amendment if that weaponry cannot be used for law-abiding purposes. Further, the Court suggested that the United States Constitution would not disallow regulations prohibiting criminals and the mentally ill from firearm possession.

In 2010, the Court further strengthened Second Amendment protections in McDonald v. City of Chicago , 567 F.3d 856. The plaintiff in McDonald challenged the constitutionality of the Chicago handgun ban, which prohibited handgun possession by almost all private citizens. In a 5-4 decision, the Court, citing the intentions of the framers and ratifiers of the Fourteenth Amendment , held that the Second Amendment applies to the states through the incorporation doctrine . The Court lacked a majority on which specific clause of the Fourteenth Amendment incorporates the fundamental right to keep and bear arms for the purpose of self-defense. While Justice Alito and his supporters looked to the Due Process Clause , Justice Thomas in his concurrence stated that the Privileges and Immunities Clause should justify incorporation.

Several questions still remain unanswered, however, such as whether regulations less stringent than the D.C. statute implicate the Second Amendment, whether lower courts will apply their dicta regarding permissible restrictions, and what level of scrutiny the courts should apply when analyzing a statute that infringes on the Second Amendment. Generally, in constitutional law, courts subject statutes and ordinances to three levels of scrutiny, depending on the issue at hand:

- strict scrutiny

- intermediate scrutiny

- rational basis

Circuit Court opinions following Heller suggests that courts are willing to uphold the following:

- Regulations prohibiting weapons on government property. US v Dorosan , 350 Fed. Appx. 874 (5th Cir. 2009) (upholding defendant’s conviction for bringing a handgun onto post office property).

- Regulations prohibiting possession of a handgun as a juvenile delinquent. US v Rene E. , 583 F.3d 8 (1st Cir. 2009) (holding that the Juvenile Delinquency Act ban of juvenile possession of handguns did not violate the Second Amendment).

- Regulations requiring a permit to carry concealed weapon. Kachalsky v County of Westchester , 701 F.3d 81 (2nd Cir. 2012) (holding that a New York law preventing individuals from obtaining a license to possess a concealed firearm in public for general purposes unless the individual showed proper cause did not violate the Second Amendment).

More recently, the U.S. Supreme Court reinforced its Heller ruling in Caetano v. Massachusetts , 136 S.Ct. 1027 (2016). The Court struck down a Massachusetts statute which prohibited the possession or use of “stun guns” by finding that “stun guns” are protected under the Second Amendment. While ruling largely on the reasoning of Heller , the opinion was per curiam and therefore did not significantly add to Second Amendment jurisprudence.

In 2022, the Supreme Court further expanded upon the precedent set by Heller in New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen . In Bruen , the Court struck down a New York law requiring parties interested in purchasing a handgun for the use of self-defense outside of the home to obtain a license because the law issued licenses on a “may-issue” rather than a “shall issue” basis. This “may issue” licensing method allowed state authorities to deny interested parties public use licenses for firearms if the interested party was unable to show “proper cause” as to why they have a heightened need for self-protection over the general population.

Furthermore, the Court disavowed the use of “means-end tests” many jurisdictions had adopted for the purposes of interpreting the Second Amendment, instead ruling that a Second Amendment analysis is limited to evaluating the historical nature of the right and whether a given use of a firearm or other weapon is deeply rooted in the history of the United States. Post- Bruen , courts can no longer use a standard scrutiny analysis like the one seen in Kachalsky v. County of Westchester to determine if a gun regulation is constitutional. Instead, a government wishing to place restrictions on firearm ownership must “affirmatively prove that its firearms regulation is part of the historical tradition that delimits the outer bounds of the right to keep and bear arms.”

In a concurrence, Justice Kavanaugh joined by Justice Roberts emphasizes that Bruen is not intended to invalidate “shall-issue” licensing structures or other restrictions on firearm ownership including fingerprinting, background checks, mental health evaluations, mandatory training requirements, and potential other requirements. Additionally, this concurrence draws a line between objective gun control measures, where an individual must pass a set of predetermined requirements, which are constitutional, and subjective gun control measures, such as licensing at a state official’s discretion, which are not.

It remains to be seen how the ruling in Bruen and the sentiments espoused in this concurrence will influence cases going forward.

See also: C onstitutional Amendment .

[Last updated in June of 2022 by the Wex Definitions Team ]

Menu of Sources

Federal material, u.s. constitution.

- Table of Contents

- CRS Annotated Constitution

Erwin Chemerinsky, Constitutional Law: Principles and Policies 26-28 (2006).

Federal Decisions:

- United States v. Miller (1939)

- District of Columbia v. Heller (2008)

- civil rights

- the Constitution

- THE LEGAL PROCESS

- courts and procedure

- group rights

- legal education and practice

- wex articles

- United States Constitution

- Bill of Rights

- constitution

- D.C. v. Heller

- constitutional law

Editorial: ‘History, tradition’ poor test for gun safety laws

By The Herald Editorial Board

Among several pieces of firearms safety legislation passed by the state Legislature in recent years — including a ban last year on the sale of assault-style semiautomatic firearms — was 2022’s ban on high-capacity magazines that hold more than 10 rounds of ammunition.

There is common sense and public support behind the restrictions on such magazines. A 2020 poll by Cascade PBS (formerly Crosscut)/Elway found that 65 percent of state registered voters polled supported regulating or banning high-capacity magazines. As well, a 2019 study found that states that did not ban large-capacity magazines suffered more than twice the number of high-fatality mass shootings compared with states with such restrictions. Those states saw fewer overall shootings and fewer deaths from mass shootings.

Yet, Monday, Cowlitz County Superior Court Judge Gary Bashor ruled — in Washington v. Gator’s Custom Guns — that the two-year-old law violated both the state constitution’s right to bear arms for self-defense and U.S. Constitution’s Second Amendment. The ruling briefly ended the ban until a state Supreme Court commissioner put the lower court ruling on hold while the state seeks review by full state Supreme Court.

The state law was challenged by a Kelso gun dealer, who faced enforcement by Attorney General Bob Ferguson after the shop continued to sell the magazines. Ferguson has defended the law as constitutional, pointing to past court cases upholding it and similar laws in other states on constitutional grounds.

Bashor bases much of his decision on the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in New York Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen , announced the same month that Washington state’s magazine ban took effect.

Writing for the 6-3 majority in Bruen, Justice Clarence Thomas broadened the right to keep and bear arms beyond the court’s 2008 Heller ruling, which affirmed the right to keep firearms in the home for self-defense, expanding it to public areas outside the home.

But that ruling went even further, declaring that state and federal gun laws must comply with an originalist interpretation of the U.S. Constitution and the Second Amendment that focuses not on public safety but on its consistency “with the nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation” as the Framers understood it, requiring that legislation could only be based on a similar 18th-century law.

As the editorial board wrote following the ruling: “We await word from the Constitution’s Framers regarding the ‘history and tradition’ of semi-automatic AR-15s and 30-round ammo clips.”

That’s the standard, however, applied by Bashor.

“Bruen was not an invitation to take a stroll through the forest of historical firearms regulation throughout American history to find a historical analogue from any random time period,” Bashor wrote. Instead, the state would have to find a historical gun regulation from 1791, just after the Bill of Rights was adopted, the judge wrote.

Yet, Ferguson said in a statement after Bashor’s ruling that — even after Bruen — every court that has heard challenges to laws restricting high-capacity magazines around the country has thus far either rejected the challenge or overruled it. Only two federal courts have ruled against such laws, Ferguson’s statement said, and both have been stayed by higher courts pending review, one of which is a California case before the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, which covers Washington state.

At the same time, the U.S. Supreme Court majority in Bruen may now be chafing under its earlier decision. Its originalist interpretation in Bruen and its “history and tradition” test may now be tested itself by two cases before the high court, writes a law professor in a recent guest essay in The New York Times.

Nelson Lund, a professor at the Antonin Scalia Law School at George Mason University, in the commentary lays out the problems with expecting 18th century laws to meet the challenges of 21st century public safety.

The first case in Lund’s review is U.S. v. Rahimi , which regards a Second Amendment challenge to federal law employed by state courts that bars possession of firearms by those subject to domestic violence restraining orders. Under Bruen’s test, Lund writes, the government during oral argument was unable to show a single law written before the 20th century that would bar someone convicted of a violent crime from owning a firearm.

The second case before it, Garland v. Cargill , involves the ban on bump stocks — devices that allow a semi-automatic weapon to fire at rates similar to automatic weapons — adopted after the 2017 massacre in Las Vegas that killed 60 people and injured hundreds more.

Here, Lund writes, the court will have to choose between making its own policy on firearms or ruling against the constitutional provision that only Congress can amend the text of a law, here the 1934 National Firearms Act, which instituted the ban on machine guns and updated it in 1986 and its description of machine guns as any weapon that shoots “automatically more than one shot, without manual reloading, by a single function of the trigger,” which is what a bump stock accomplishes.

The conundrum the court faces in the two cases, Lund writes: “No judge can relish being accused of siding with domestic abusers or of allowing a weapon to remain on the market that facilitated mass murder.”

Yet, that’s what Bruen’s “history and tradition” test appears to demand.

And that’s the folly in forcing today’s laws to fit a narrow reading of documents — that the Founders entrusted to us 233 years ago to provide a framework for our rights and responsibilities — that we now seek to apply to the challenges we face today.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

We Clerked for Justices Scalia and Stevens. America Is Getting Heller Wrong.

By Kate Shaw and John Bash

Ms. Shaw is a professor of law at Cardozo Law School. Mr. Bash is an attorney in private practice in Austin, Texas.

In the summer of 2008, the Supreme Court decided District of Columbia v. Heller, in which the court held for the first time that the Second Amendment protected an individual right to gun ownership. We were law clerks to Justice Antonin Scalia, who wrote the majority opinion, and Justice John Paul Stevens, who wrote the lead dissent.

Justices Scalia and Stevens clashed over the meaning of the Second Amendment. Justice Scalia’s majority opinion held that the amendment protected an individual right to keep a usable handgun at home, which meant the District of Columbia law prohibiting such possession was unconstitutional. Justice Stevens argued that those protections extended only to firearm ownership in conjunction with service in a “well-regulated militia,” in the words of the Second Amendment.

We each assisted a boss we revered in drafting his opinion, and we’re able to acknowledge that work without breaching any confidences. Justice Scalia had a practice of signing one opinion for a clerk each term, which permitted the clerk to disclose having worked on that case, and for John, that was Heller; Justice Stevens noted in his 2019 autobiography, “ The Making of a Justice ,” that Kate was the Heller clerk in his chambers.

We continue to hold very different views about both gun regulation and how the Constitution should be interpreted. Kate believes in a robust set of gun safety measures to reduce the unconscionable number of shootings in this country. John is skeptical of laws that would make criminals out of millions of otherwise law-abiding citizens who believe that firearm ownership is essential to protecting their families, and he is not convinced that new measures like bans on widely owned firearms would stop people who are willing to commit murder from obtaining guns.

Kate believes that Justice Stevens’s dissent in Heller provided a better account of both the text and history of the Second Amendment and that in any event, the method of historical inquiry the majority prescribes should lead to the court upholding most gun safety measures, including the New York law pending before the Supreme Court. John believes that Heller correctly construed the original meaning of the Second Amendment and is one of the most important decisions in U.S. history. We disagree about whether Heller should be extended to protect citizens who wish to carry firearms outside the home for self-defense and, if so, how states may regulate that activity — issues that the Supreme Court is set to decide in the New York case in the next month or so.

But despite our fundamental disagreements, we are both concerned that Heller has been misused in important policy debates about our nation’s gun laws. In the 14 years since the Heller decision, Congress has not enacted significant new laws regulating firearms, despite progressives’ calls for such measures in the wake of mass shootings. Many politicians cite Heller as the reason. But they are wrong.

Heller does not totally disable government from passing laws that seek to prevent the kind of atrocities we saw in Uvalde, Texas. And we believe that politicians on both sides of the aisle have (intentionally or not) misconstrued Heller. Some progressives, for example, have blamed the Second Amendment, Heller or the Supreme Court for mass shootings. And some conservatives have justified contested policy positions merely by pointing to Heller, as if the opinion resolved the issues.

Neither is fair. Rather, we think it’s clear that every member of the court on which we clerked joined an opinion, either majority or dissent, that agreed that the Constitution leaves elected officials an array of policy options when it comes to gun regulation.

Justice Scalia — the foremost proponent of originalism, who throughout his tenure stressed the limited role of courts in difficult policy debates — could not have been clearer in the closing passage of Heller that “the problem of handgun violence in this country” is serious and that the Constitution leaves the government with “a variety of tools for combating that problem, including some measures regulating handguns.” Heller merely established the constitutional baseline that the government may not disarm citizens in their homes. The opinion expressly recognized “presumptively lawful” regulations such as “laws imposing conditions and qualifications on the commercial sale of arms,” as well as bans on carrying weapons in “sensitive places,” like schools, and it noted with approval the “historical tradition of prohibiting the carrying of ‘dangerous and unusual weapons.’” Heller also recognized the immense public interest in “prohibitions on the possession of firearms by felons and the mentally ill.”

Nothing in Heller casts doubt on the permissibility of background check laws or requires the so-called Charleston loophole, which allows individuals to purchase firearms even without completed background checks. Nor does Heller prohibit giving law enforcement officers more effective tools and greater resources to disarm people who have proved themselves to be violent or mentally ill, as long as due process is observed. Heller also gives the government at least some leeway to restrict the kinds of firearms that can be purchased — few would claim a constitutional right to own a grenade launcher, for example — although where that line could be constitutionally drawn is a matter of disagreement, including between us. Indeed, President Donald Trump banned bump stocks in the wake of the mass shooting in Las Vegas.

Most of the obstacles to gun regulations are political and policy based, not legal; it’s laws that never get enacted, rather than ones that are struck down, because of an unduly expansive reading of Heller. We are aware of no evidence that any perpetrator of a mass shooting was able to obtain a firearm because of a law struck down under Heller. But Heller looms over most debates about gun regulation, and it often serves as a useful foil for those who would like to deflect responsibility — either for their policy choice to oppose a particular gun regulation proposal or for their failure to convince their fellow legislators and citizens that the proposal should be enacted.

The closest we’ve come to major new federal gun regulation in recent years came in the post-Sandy Hook effort to create expanded background checks. The most common reason offered by opponents of that legislation? That it would violate the Second Amendment. But that’s just not supported by the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the amendment in Heller. If opponents of background checks for firearm sales believe that such requirements are unlikely to reduce violence while imposing unwarranted burdens on lawful gun owners, they should make that case openly, not rest on a mistaken view of Heller.

Justices don’t control the way their writings are interpreted by later courts and other institutions; certainly law clerks don’t. So we’re not asserting that our views on Heller are in any way authoritative. But we know the opinions in the case inside and out.

As the nation enters yet another agonizing conversation about gun regulation in the wake of the Uvalde tragedy, all sides should focus on the value judgments and empirical assumptions at the heart of the policy debate, and they should take moral ownership of their positions. The genius of our Constitution is that it leaves many of the hardest questions to the democratic process.

Kate Shaw is a professor of law at Cardozo Law School and a host of the Supreme Court podcast “Strict Scrutiny.” She served as a law clerk to Justice John Paul Stevens from 2007 to 2008. John Bash is an attorney in private practice in Austin, Texas. He served in the Department of Justice, including as the U.S. attorney for the Western District of Texas from 2017 to 2020, and as a law clerk to Justice Antonin Scalia from 2007 to 2008.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram .

Kate Shaw is a contributing Opinion writer, a professor of law at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School and a host of the Supreme Court podcast “Strict Scrutiny.” She served as a law clerk to Justice John Paul Stevens and Judge Richard Posner.

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

I Served on the Florida Supreme Court. What the New Majority Just Did Is Indefensible.

On April 1, the Florida Supreme Court, in a 6–1 ruling, overturned decades of decisions beginning in 1989 that recognized a woman’s right to choose—that is, whether to have an abortion—up to the time of viability.

Anchored in Florida’s own constitutional right to privacy, this critical individual right to abortion had been repeatedly affirmed by the state Supreme Court, which consistently struck down conflicting laws passed by the Legislature.

As explained first in 1989:

Florida’s privacy provision is clearly implicated in a woman’s decision of whether or not to continue her pregnancy. We can conceive of few more personal or private decisions concerning one’s body in the course of a lifetime.

Tellingly, the justices at the time acknowledged that their decision was based not only on U.S. Supreme Court precedent but also on Florida’s own privacy amendment.

I served on the Supreme Court of Florida beginning in 1998 and retired, based on our mandatory retirement requirement, a little more than two decades later. Whether Florida’s Constitution provided a right to privacy that encompassed abortion was never questioned, even by those who would have been deemed the most conservative justices—almost all white men back in 1989!

And strikingly, one of the conservative justices at that time stated: “If the United States Supreme Court were to subsequently recede from Roe v. Wade , this would not diminish the abortion rights now provided by the privacy amendment of the Florida Constitution.” Wow!

In 2017 I authored an opinion holding unconstitutional an additional 24-hour waiting period after a woman chooses to terminate her pregnancy. Pointing out that other medical procedures did not have such requirements, the majority opinion noted, “Women may take as long as they need to make this deeply personal decision,” adding that the additional 24 hours stipulated that the patient make a second, medically unnecessary trip, incurring additional costs and delays. The court applied what is known in constitutional law as a “strict scrutiny” test for fundamental rights.

Interestingly, Justice Charles Canady, who is still on the Florida Supreme Court and who participated in the evisceration of Florida’s privacy amendment last week, did not challenge the central point that abortion is included in an individual’s right to privacy. He dissented, not on substantive grounds but on technical grounds.

So what can explain this 180-degree turn by the current Florida Supreme Court? If I said “politics,” that answer would be insufficient, overly simplistic. Unfortunately, with this court, precedent is precedent until it is not. Perhaps each of the six justices is individually, morally or religiously, opposed to abortion.

Yet, all the same, by a 4–3 majority, the justices—three of whom participated in overturning precedent—voted to allow the proposed constitutional amendment on abortion to be placed on the November ballot. (The dissenters: the three female members of the Supreme Court.) That proposed constitutional amendment:

Amendment to Limit Government Interference With Abortion: No law shall prohibit, penalize, delay, or restrict abortion before viability or when necessary to protect the patient’s health, as determined by the patient’s healthcare provider. This amendment does not change the Legislature’s constitutional authority to require notification to a parent or guardian before a minor has an abortion.

For the proposed amendment to pass and become enshrined in the state constitution, 60 percent of Florida voters must vote yes.

In approving the amendment to be placed on the ballot at the same time that it upheld Florida’s abortion bans, the court angered those who support a woman’s right to choose as well as those who are opposed to abortion. Most likely the latter groups embrace the notion that fetuses are human beings and have rights that deserve to be protected. Indeed, Chief Justice Carlos Muñiz, during oral argument on the abortion amendment case, queried the state attorney general on precisely that issue, asking if the constitutional language that defends the rights of all natural persons extends to an unborn child at any stage of pregnancy.

In fact, and most troubling, it was the three recently elevated Gov. Ron DeSantis appointees—all women—who expressed their views that the voters should not be allowed to vote on the amendment because it could affect the rights of the unborn child. Justice Jamie Grosshans, joined by Justice Meredith Sasso, expressed that the amendment was defective because it failed to disclose the potential effect on the rights of the unborn child. Justice Renatha Francis was even more direct, writing in her dissent:

The exercise of a “right” to an abortion literally results in a devastating infringement on the right of another person: the right to live. And our Florida Constitution recognizes that “life” is a “basic right” for “[a]ll natural persons.” One must recognize the unborn’s competing right to life and the State’s moral duty to protect that life.

In other words, the three dissenting justices would recognize that fetuses are included in who is a “natural person” under Florida’s Constitution.

What should be top of mind days after the dueling decisions? Grave concern for the women of our state who will be in limbo because, following the court’s ruling, a six-week abortion ban—at a time before many women even know they are pregnant—will be allowed to go into effect. We know that these restrictions will disproportionately affect low-income women and those who live in rural communities.

But interestingly, there is a provision in the six-week abortion ban statute that allows for an abortion before viability in cases of medical necessity: if two physicians certify that the pregnant patient is at risk of death or that the “fetus has a fatal fetal abnormality.”

The challenge will be finding physicians willing to put their professional reputations on the line in a state bent on cruelly impeding access to needed medical care when it comes to abortion.

Yet, this is the time that individuals and organizations dedicated to women’s health, as well as like-minded politicians, will be crucial in coordinating efforts to ensure that abortions, when needed, are performed safely and without delay. This is the time to celebrate and support organizations, such as Planned Parenthood and Emergency Medical Assistance , as well as our own RBG Fund , which provides patients necessary resources and information. Floridians should also take full advantage of the Repro Legal Helpline .

We all have a role in this—women and men alike. Let’s get out, speak out, shout out, coordinate our efforts, and, most importantly, vote . Working together, we can make a difference.

Arizona Supreme Court ruling clears way for near-total abortion ban

Arizona’s conservative Supreme Court on Tuesday revived a near-total ban on abortion , invoking an 1864 law that forbids the procedure except to save a mother’s life and punishes providers with prison time.

The 4-2 decision supersedes the previous rule, which guarded the right to end a pregnancy by the 15-week mark, resetting policy to the pre- Roe v. Wade era and adding Arizona to the roster of 16 other states where abortion is virtually outlawed.

The ruling cannot be enforced for 14 days, the judges wrote, during which Planned Parenthood Arizona, as a party to the court case, could raise constitutionality questions before a lower court. And because of a separate ruling in a parallel case that sets a second clock ticking, the organization expects to provide abortion services through May, officials said during a Tuesday briefing.

Under the 1864 territorial law, which went into effect 48 years before Arizona became a state, anyone who administers an abortion could face a mandatory prison sentence of two to five years. That could compel Arizona’s licensed abortion clinics to ramp down dramatically or shutter — though it’s unclear how the decision will be enforced.

The attorney general in charge of overseeing abortion laws, Democrat Kris Mayes, has vowed not to enforce any bans. Her decision, however, could be challenged at the county level.

Eight of Arizona’s nine abortion clinics temporarily closed two years ago when the U.S. Supreme Court struck down Roe , ending national protections for abortion rights.

Where is abortion legal and illegal?

The legal upheaval comes as reproductive-rights advocates push for a November ballot measure that would protect access to abortion in the Arizona state constitution. Campaigners have already gathered more than enough signatures to qualify, according to the Arizona Republic.

“Arizonans deserve the right to make our own decisions about pregnancy and abortion without politicians and judges interfering,” said Chris Love, a Phoenix lawyer and spokeswoman for the ballot measure campaign.

Doctors across the country have complained that the post- Roe landscape of restrictions makes it hard to know when they can legally intervene to save a pregnant person’s life. Waiting too long, some have argued, could lead to permanent damage, including infertility.

“We will see more women who are told to wait in the parking lot or go back home until they are sicker, closer to death, to receive health care,” said Jill Habig, president of the Public Rights Project, which represented the county attorney opposing the ban.

Marjorie Dannenfelser, president of the antiabortion group SBA Pro-Life America, called the court’s decision an “enormous victory.”

“Today’s state Supreme Court decision is a major advancement in the fight for life in Arizona,” she said in a statement.

Critics of the November campaign to enshrine abortion rights in Arizona skipped over a response to the court judgment Tuesday, writing that “reasonable people can have different opinions on abortion and policy.”

A proposed amendment that “expands abortion beyond what voters support is not the answer,” Leisa Brug, campaign manager for that movement, said in a statement.

The question of abortion legality landed before Arizona’s Supreme Court after the state’s former attorney general, a Republican, asked the justices to restore the 160-year-old ban, setting off a litigation battle with Planned Parenthood.

Jill Gibson, chief medical officer for Planned Parenthood Arizona, said she was seeing patients at a clinic in Tempe when the ruling sparked “an atmosphere of chaos.”

The impact could worsen physician shortages in the state, she said: Confusion over what doctors can do and when without risking prison could motivate them to relocate to states without restrictions.

“It just completely wreaks havoc on our ability to do our jobs,” Gibson said, “and patients are going to be the ones that suffer.”

Arizona’s court judgment follows a move by Florida’s right-leaning Supreme Court to all but prohibit abortion, effective next month. In a separate decision, however, the high court in Tallahassee allowed an amendment enshrining the right to the procedure to go on the November ballot.

The justices behind the Arizona decision, four men and two women, were all appointed by Republicans. A fifth male judge had recused himself after reporters resurfaced a Facebook post in which he called abortion “the greatest genocide known to man.” Their views Tuesday did not split by gender: The majority opinion was supported by one woman and three male justices, while a male and female justice dissented.

Since the fall of Roe v. Wade , the fate of abortion access has roused the left, boosting Democratic turnout practically everywhere the issue has been on the ballot and putting Republicans, from presumptive presidential nominee Donald Trump on down, in a defensive posture.

In a statement soon after the court released its decision, President Biden cast it in dire terms.

“Millions of Arizonans will soon live under an even more extreme and dangerous abortion ban, which fails to protect women even when their health is at risk or in tragic cases of rape or incest,” Biden’s statement said. “This cruel ban was first enacted in 1864 — more than 150 years ago, before Arizona was even a state and well before women had secured the right to vote.”

Most Americans disagree with revoking the option to end a pregnancy, and swelling numbers of political moderates have indicated in surveys that the issue is likely to influence which candidates they support.

Republicans felt the sting last November when five states across the political spectrum voted on abortion referendums, and each one elected to maintain access .

Trump urged his party this week to step away from the goal of a national abortion ban, at least through the election, igniting public clashes with some of his GOP allies.

“We cannot let our Country suffer any further damage by losing Elections on an issue that should always have been decided by the States,” he wrote in a social media post.

U.S. abortion access, reproductive rights

Tracking abortion access in the United States: Since the Supreme Court struck down Roe v. Wade , the legality of abortion has been left to individual states. The Washington Post is tracking states where abortion is legal, banned or under threat.

Abortion and the election: Voters in a dozen states in this pivotal election year could decide the fate of abortion rights with constitutional amendments on the ballot. Biden supports legal access to abortion , and he has encouraged Congress to pass a law that would codify abortion rights nationwide. After months of mixed signals about his position, Trump said the issue should be left to states . Here’s how Trump’s abortion stance has shifted over the years.

New study: The number of women using abortion pills to end their pregnancies on their own without the direct involvement of a U.S.-based medical provider rose sharply in the months after the Supreme Court eliminated a constitutional right to abortion , according to new research.

Abortion pills: The Supreme Court seemed unlikely to limit access to the abortion pill mifepristone . Here’s what’s at stake in the case and some key moments from oral arguments . For now, full access to mifepristone will remain in place . Here’s how mifepristone is used and where you can legally access the abortion pill .

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The debate over the Second Amendment is how the interpretation is in the first place. The Second Amendment in the Bill of Rights states, 'A well-regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed'. It is giving the right for people to bear arms.

Jamie Raskin, a Democrat, represents Maryland's Eighth Congressional District in the House of Representatives. He served as lead impeachment manager in Donald Trump's second impeachment trial ...

The U.S. Constitution's guarantee of the right to bear arms has been a primary conversation topic among Americans in 2020. As uncertainty and fear have plagued the world over the last eight months ...

The Second Amendment originally applied only to the federal government, leaving the states to regulate weapons as they saw fit. Although there is substantial evidence that the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment was meant to protect the right of individuals to keep and bear arms from infringement by the states, the ...

Gun violence is perpetuated by the Second Amendment, which asserts a constitutional right to obtain a firearm, yet this right culminates in gun violence dominating the United States. In 2020, gun violence alone comprised 79% of all homicides.[5] Still, proponents of the Second Amendment stress the importance of citizens' right to bear arms.

Implicit in the debate between Federalists and Anti-Federalists were two shared assumptions. First, that the proposed new Constitution gave the federal government almost total legal authority over the army and militia. Second, that the federal government should not have any authority at all to disarm the citizenry.

Footnotes Jump to essay-1 United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 (1875); Presser v. Illinois, 116 U.S. 252 (1886); Miller v. Texas, 153 U.S. 535 (1894).The Fourteenth Amendment, through which the Second Amendment was later held to be applicable to the states, was ratified following the Civil War, in 1868.

"It has always been widely understood that the Second Amendment, like the First and Fourth Amendments, codified a preexisting right," the majority stated. Four of the nine Supreme Court Justices disagreed with the Court's ruling. The dissenters agreed that the Second Amendment protected an individual right.

Jump to essay-12 See Steven J. Heyman, Natural Rights and the Second Amendment, in The Second Amendment in Law and History: Historians and Constitutional Scholars on the Right to Bear Arms 200-01 (Carl T. Bogus ed., 2000) (collecting anti-federalist objections regarding power over militia and to raise a standing army that could be used to ...

The Second Amendment, ratified in 1791, is one of 10 amendments that form the Bill of Rights. It establishes the right to bear arms and figures prominently in the long-running debate over gun control.

A concurring opinion by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, joined by Chief Justice John Roberts, emphasized that "properly interpreted, the Second Amendment allows a variety of gun regulations," and ...

Jump to essay-7 This view of the Second Amendment has been invalidated by subsequent Supreme Court precedent. ... One judge on the panel wrote a special concurrence refusing to join in the section of the opinion concluding that the Second Amendment protected an individual right, characterizing it as dicta and unnecessary to resolve the case.

The Second Amendment of the United States Constitution reads: "A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed." Such language has created considerable debate regarding the Amendment's intended scope.On the one hand, some believe that the Amendment's phrase "the right of the people to keep and bear ...

Mr. Lund is a professor at the Antonin Scalia Law School at George Mason University and has written widely on constitutional law, including the Second Amendment. The Supreme Court reputedly has a ...

The Second Amendment (Amendment II) to the United States Constitution protects the right to keep and bear arms.It was ratified on December 15, 1791, along with nine other articles of the Bill of Rights. In District of Columbia v.Heller (2008), the Supreme Court affirmed for the first time that the right belongs to individuals, for self-defense in the home, while also including, as dicta, that ...

The Second Amendment reads, "A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.". Referred to in modern times as an individual's right to carry and use arms for self-defense, the Second Amendment was envisioned by the framers of the Constitution ...

The Second Amendment states that the country needs to have a well-regulated militia in order to ensure the overall security of the nation, and it gives individuals the right to bear arms. Over ...

John Paul Stevens: Repeal the Second Amendment. A musket from the 18th century, when the Second Amendment was written, and an assault rifle of today. Top, MPI, via Getty Images, bottom, Joe Raedle ...

The Second Amendment is making headlines these days. The Second Amendment states, A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed. This Amendment was ratified in December of 1791. This amendment was proposed by James Madison, after the constitution ...

Reflection on Second Amendment: Opinion Essay. This essay sample was donated by a student to help the academic community. Papers provided by EduBirdie writers usually outdo students' samples. The constitution was initially established September 17, 1787 at the constitutional convention. The constitution was created to establish a government ...

The first case in Lund's review is U.S. v. Rahimi, which regards a Second Amendment challenge to federal law employed by state courts that bars possession of firearms by those subject to ...

In the summer of 2008, the Supreme Court decided District of Columbia v. Heller, in which the court held for the first time that the Second Amendment protected an individual right to gun ownership.

What the New Majority Just Did Is Indefensible. We all have a role in this—women and men alike. Chandan Khanna/AFP/Getty Images. On April 1, the Florida Supreme Court, in a 6-1 ruling ...

The majority declined to weigh in on whether the prevailing historical understanding for analytical purposes should be pegged to when the Second Amendment was adopted in 1791 or when the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868, as the majority opinion concluded that the public understanding was the same at both points for relevant purposes ...

Arizona's conservative Supreme Court on Tuesday revived a near-total ban on abortion, invoking an 1864 law that forbids the procedure except to save a mother's life and punishes providers with ...