Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.3 Social Class in the United States

Learning objectives.

- Distinguish objective and subjective measures of social class.

- Outline the functionalist view of the American class structure.

- Outline the conflict view of the American class structure.

- Discuss whether the United States has much vertical social mobility.

There is a surprising amount of disagreement among sociologists on the number of social classes in the United States and even on how to measure social class membership. We first look at the measurement issue and then discuss the number and types of classes sociologists have delineated.

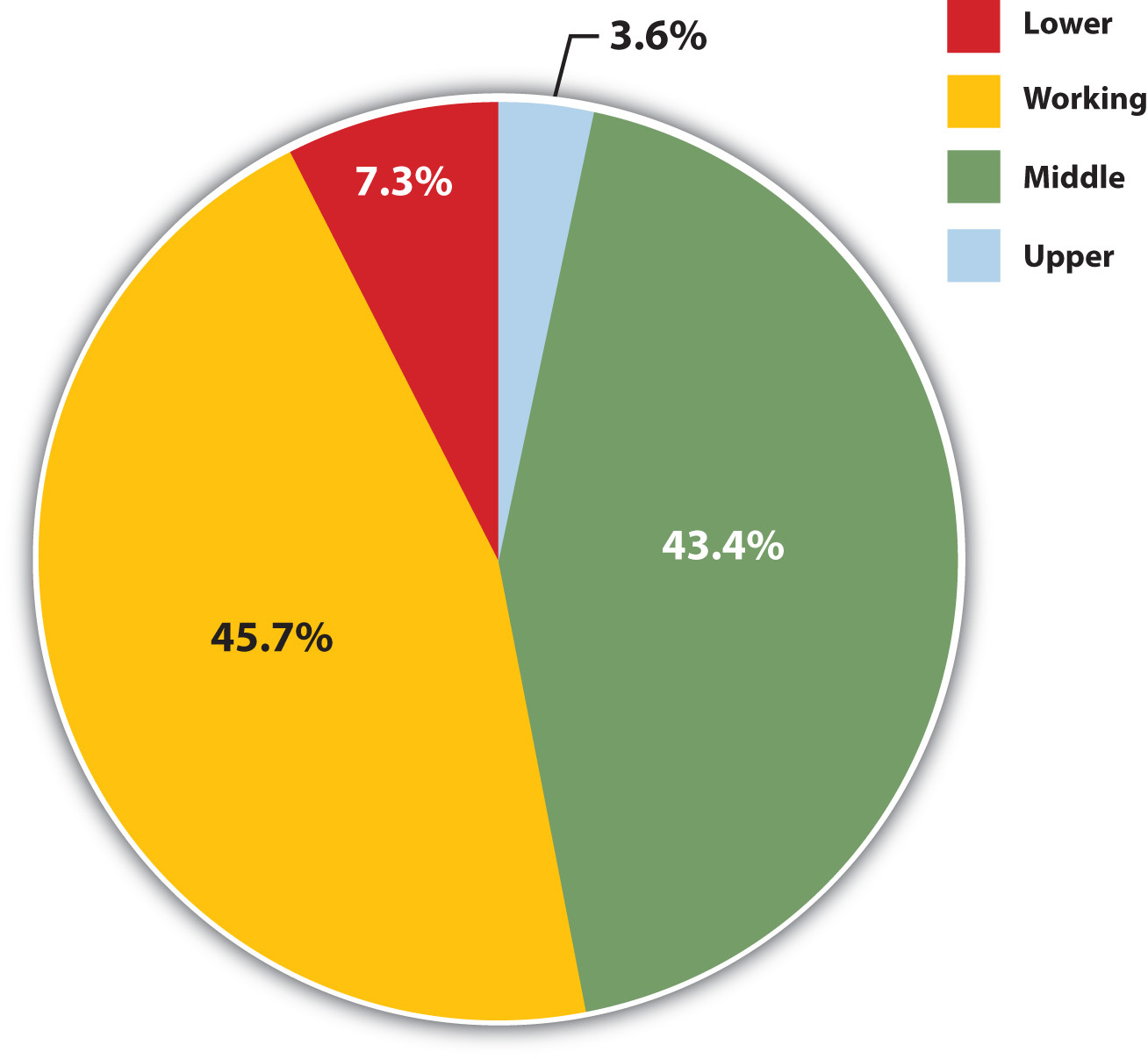

Measuring Social Class

We can measure social class either objectively or subjectively . If we choose the objective method, we classify people according to one or more criteria, such as their occupation, education, and/or income. The researcher is the one who decides which social class people are in based on where they stand in regard to these variables. If we choose the subjective method, we ask people what class they think they are in. For example, the General Social Survey asks, “If you were asked to use one of four names for your social class, which would you say you belong in: the lower class, the working class, the middle class, or the upper class?” Figure 8.3 “Subjective Social Class Membership” depicts responses to this question. The trouble with such a subjective measure is that some people say they are in a social class that differs from what objective criteria might indicate they are in. This problem leads most sociologists to favor objective measures of social class when they study stratification in American society.

Figure 8.3 Subjective Social Class Membership

Source: Data from General Social Survey, 2008.

Yet even here there is disagreement between functionalist theorists and conflict theorists on which objective measures to use. Functionalist sociologists rely on measures of socioeconomic status (SES) , such as education, income, and occupation, to determine someone’s social class. Sometimes one of these three variables is used by itself to measure social class, and sometimes two or all three of the variables are combined (in ways that need not concern us) to measure social class. When occupation is used, sociologists often rely on standard measures of occupational prestige. Since the late 1940s, national surveys have asked Americans to rate the prestige of dozens of occupations, and their ratings are averaged together to yield prestige scores for the occupations (Hodge, Siegel, & Rossi, 1964). Over the years these scores have been relatively stable. Here are some average prestige scores for various occupations: physician, 86; college professor, 74; elementary school teacher, 64; letter carrier, 47; garbage collector, 28; and janitor, 22.

Despite SES’s usefulness, conflict sociologists prefer different, though still objective, measures of social class that take into account ownership of the means of production and other dynamics of the workplace. These measures are closer to what Marx meant by the concept of class throughout his work, and they take into account the many types of occupations and workplace structures that he could not have envisioned when he was writing during the 19th century.

For example, corporations have many upper-level managers who do not own the means of production but still determine the activities of workers under them. They thus do not fit neatly into either of Marx’s two major classes, the bourgeoisie or the proletariat. Recognizing these problems, conflict sociologists delineate social class on the basis of several factors, including the ownership of the means of production, the degree of autonomy workers enjoy in their jobs, and whether they supervise other workers or are supervised themselves (Wright, 2000).

The American Class Structure

As should be evident, it is not easy to determine how many social classes exist in the United States. Over the decades, sociologists have outlined as many as six or seven social classes based on such things as, once again, education, occupation, and income, but also on lifestyle, the schools people’s children attend, a family’s reputation in the community, how “old” or “new” people’s wealth is, and so forth (Coleman & Rainwater, 1978; Warner & Lunt, 1941). For the sake of clarity, we will limit ourselves to the four social classes included in Figure 8.3 “Subjective Social Class Membership” : the upper class, the middle class, the working class, and the lower class. Although subcategories exist within some of these broad categories, they still capture the most important differences in the American class structure (Gilbert, 2011). The annual income categories listed for each class are admittedly somewhat arbitrary but are based on the percentage of households above or below a specific income level.

The Upper Class

Depending on how it is defined, the upper class consists of about 4% of the U.S. population and includes households with annual incomes (2009 data) of more than $200,000 (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, & Smith, 2010). Some scholars would raise the ante further by limiting the upper class to households with incomes of at least $500,000 or so, which in turn reduces this class to about 1% of the population, with an average wealth (income, stocks and bonds, and real estate) of several million dollars. However it is defined, the upper class has much wealth, power, and influence (Kerbo, 2009).

The upper class in the United States consists of about 4% of all households and possesses much wealth, power, and influence.

Steven Martin – Highland Park Mansion – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Members of the upper-upper class have “old” money that has been in their families for generations; some boast of their ancestors coming over on the Mayflower . They belong to exclusive clubs and live in exclusive neighborhoods; have their names in the Social Register ; send their children to expensive private schools; serve on the boards of museums, corporations, and major charities; and exert much influence on the political process and other areas of life from behind the scenes. Members of the lower-upper class have “new” money acquired through hard work, lucky investments, and/or athletic prowess. In many ways their lives are similar to those of their old-money counterparts, but they do not enjoy the prestige that old money brings. Bill Gates, the founder of Microsoft and the richest person in the United States in 2009, would be considered a member of the lower-upper class because his money is too “new.” Because he does not have a long-standing pedigree, upper-upper class members might even be tempted to disparage his immense wealth, at least in private.

The Middle Class

Many of us like to think of ourselves in the middle class, as Figure 8.3 “Subjective Social Class Membership” showed, and many of us are. The middle class includes the 46% of all households whose annual incomes range from $50,000 to $199,999. As this very broad range suggests, the middle class includes people with many different levels of education and income and many different types of jobs. It is thus helpful to distinguish the upper-middle class from the lower-middle class on the upper and lower ends of this income bracket, respectively. The upper-middle class has household incomes from about $150,000 to $199,000, amounting to about 4.4% of all households. People in the upper-middle class typically have college and, very often, graduate or professional degrees; live in the suburbs or in fairly expensive urban areas; and are bankers, lawyers, engineers, corporate managers, and financial advisers, among other occupations.

The upper-middle class in the United States consists of about 4.4% of all households, with incomes ranging from $150,000 to $199,000.

Alyson Hurt – Back Porch – CC BY-NC 2.0.

The lower-middle class has household incomes from about $50,000 to $74,999, amounting to about 18% of all families. People in this income bracket typically work in white-collar jobs as nurses, teachers, and the like. Many have college degrees, usually from the less prestigious colleges, but many also have 2-year degrees or only a high school degree. They live somewhat comfortable lives but can hardly afford to go on expensive vacations or buy expensive cars and can send their children to expensive colleges only if they receive significant financial aid.

The Working Class

The working class in the United States consists of about 25% of all households, whose members work in blue-collar jobs and less skilled clerical positions.

Lisa Risager – Ebeltoft – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Working-class households have annual incomes between about $25,000 and $49,999 and constitute about 25% of all U.S. households. They generally work in blue-collar jobs such as factory work, construction, restaurant serving, and less skilled clerical positions. People in the working class typically do not have 4-year college degrees, and some do not have high school degrees. Although most are not living in official poverty, their financial situation is very uncomfortable. A single large medical bill or expensive car repair would be almost impossible to pay without going into considerable debt. Working-class families are far less likely than their wealthier counterparts to own their own homes or to send their children to college. Many of them live at risk for unemployment as their companies downsize by laying off workers even in good times, and hundreds of thousands began to be laid off when the U.S. recession began in 2008.

The Lower Class

The lower class or poor in the United States constitute about 25% of all households. Many poor individuals lack high school degrees and are unemployed or employed only part time.

Chris Hunkeler – Trailer Homes – CC BY-SA 2.0.

Although lower class is a common term, many observers prefer a less negative-sounding term like the poor, which is the term used here. The poor have household incomes under $25,000 and constitute about 25% of all U.S. households. Many of the poor lack high school degrees, and many are unemployed or employed only part time in semiskilled or unskilled jobs. When they do work, they work as janitors, house cleaners, migrant laborers, and shoe shiners. They tend to rent apartments rather than own their own homes, lack medical insurance, and have inadequate diets. We will discuss the poor further when we focus later in this chapter on inequality and poverty in the United States.

Social Mobility

Regardless of how we measure and define social class, what are our chances of moving up or down within the American class structure? As we saw earlier, the degree of vertical social mobility is a key distinguishing feature of systems of stratification. Class systems such as in the United States are thought to be open, meaning that social mobility is relatively high. It is important, then, to determine how much social mobility exists in the United States.

Here we need to distinguish between two types of vertical social mobility. Intergenerational mobility refers to mobility from one generation to the next within the same family. If children from poor parents end up in high-paying jobs, the children have experienced upward intergenerational mobility. Conversely, if children of college professors end up hauling trash for a living, these children have experienced downward intergenerational mobility. Intragenerational mobility refers to mobility within a person’s own lifetime. If you start out as an administrative assistant in a large corporation and end up as an upper-level manager, you have experienced upward intragenerational mobility. But if you start out from business school as an upper-level manager and get laid off 10 years later because of corporate downsizing, you have experienced downward intragenerational mobility.

Sociologists have conducted a good deal of research on vertical mobility, much of it involving the movement of males up or down the occupational prestige ladder compared to their fathers, with the earliest studies beginning in the 1960s (Blau & Duncan, 1967; Featherman & Hauser, 1978). For better or worse, the focus on males occurred because the initial research occurred when many women were still homemakers and also because women back then were excluded from many studies in the social and biological sciences. The early research on males found that about half of sons end up in higher-prestige jobs than their fathers had but that the difference between the sons’ jobs and their fathers’ was relatively small. For example, a child of a janitor may end up running a hardware store but is very unlikely to end up as a corporate executive. To reach that lofty position, it helps greatly to have parents in jobs much more prestigious than a janitor’s. Contemporary research also finds much less mobility among African Americans and Latinos than among non-Latino whites with the same education and family backgrounds, suggesting an important negative impact of racial and ethnic discrimination (see Chapter 7 “Deviance, Crime, and Social Control” ).

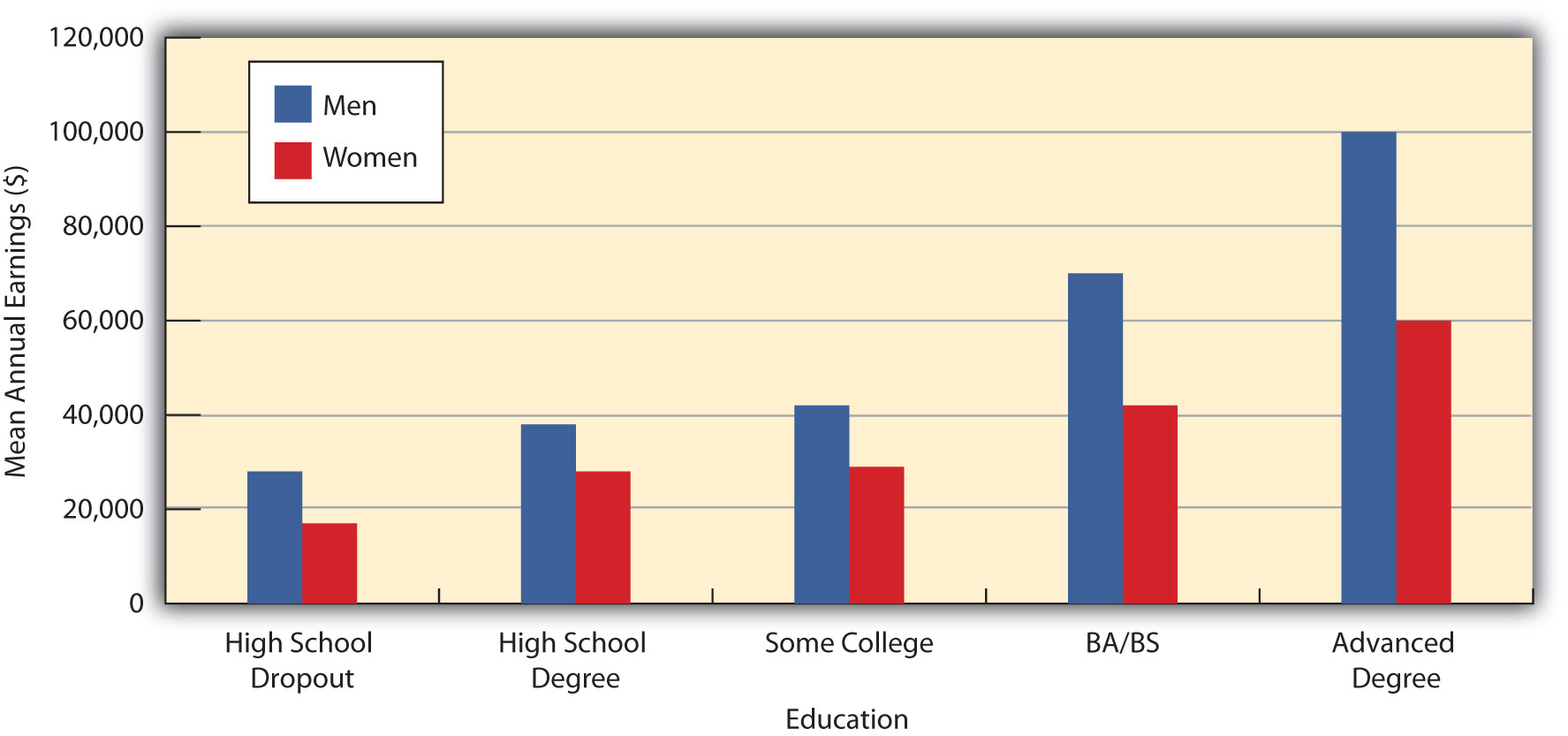

A college education is a key step toward achieving upward social mobility. However, the payoff of education is often higher for men than for women and for whites than for people of color.

Nazareth College – Commencement 2013 – CC BY 2.0.

A key vehicle for upward mobility is formal education. Regardless of the socioeconomic status of our parents, we are much more likely to end up in a high-paying job if we attain a college degree or, increasingly, a graduate or professional degree. Figure 8.4 “Education and Median Earnings of Year-Round, Full-Time Workers, 2007” vividly shows the difference that education makes for Americans’ median annual incomes. Notice, however, that for a given level of education, men’s incomes are greater than women’s. Figure 8.4 “Education and Median Earnings of Year-Round, Full-Time Workers, 2007” thus suggests that the payoff of education is higher for men than for women, and many studies support this conclusion (Green & Ferber, 2008). The reasons for this gender difference are complex and will be discussed further in Chapter 11 “Gender and Gender Inequality” . To the extent vertical social mobility exists in the United States, then, it is higher for men than for women and higher for whites than for people of color.

Figure 8.4 Education and Median Earnings of Year-Round, Full-Time Workers, 2007

Source: Data from U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). Statistical abstract of the United States: 2010 . Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab .

Certainly the United States has upward social mobility, even when we take into account gender and racial discrimination. Whether we conclude the United States has a lot of vertical mobility or just a little is the key question, and the answer to this question depends on how the data are interpreted. People can and do move up the socioeconomic ladder, but their movement is fairly limited. Hardly anyone starts at the bottom of the ladder and ends up at the top. As we see later in this chapter, recent trends in the U.S. economy have made it more difficult to move up the ladder and have even worsened the status of some people.

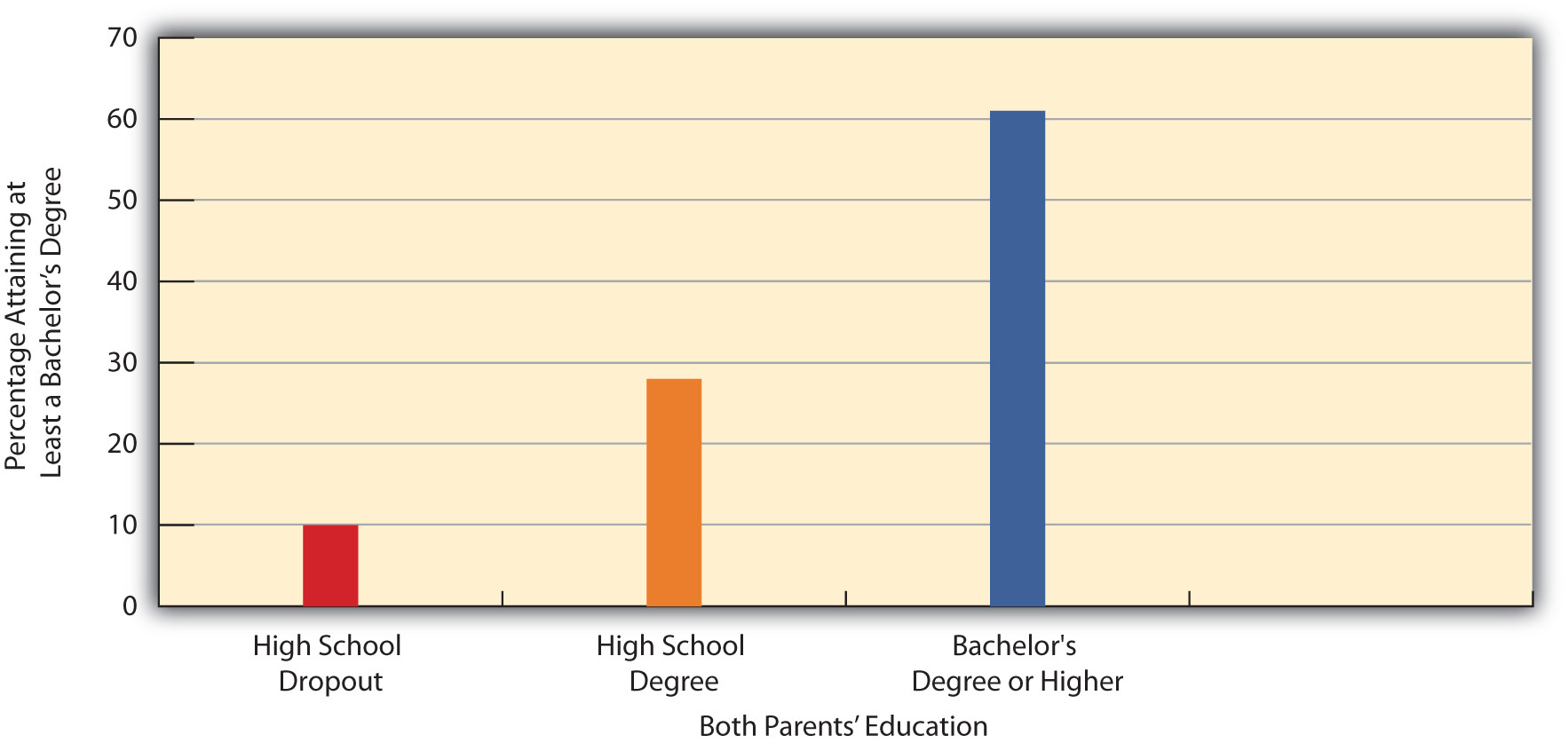

One way of understanding the issue of U.S. mobility is to see how much parents’ education affects the education their children attain. Figure 8.5 “Parents’ Education and Percentage of Respondents Who Have a College Degree” compares how General Social Survey respondents with parents of different educational backgrounds fare in attaining a college (bachelor’s) degree. For the sake of clarity, the figure includes only those respondents whose parents had the same level of education as each other: they either both dropped out of high school, both were high school graduates, or both were college graduates.

Figure 8.5 Parents’ Education and Percentage of Respondents Who Have a College Degree

As Figure 8.5 “Parents’ Education and Percentage of Respondents Who Have a College Degree” indicates, we are much more likely to get a college degree if our parents had college degrees themselves. The two bars for respondents whose parents were high school graduates or dropouts, respectively, do represent upward mobility, because the respondents are graduating from college even though their parents did not. But the three bars taken together also show that our chances of going to college depend heavily on our parents’ education (and presumably their income and other aspects of our family backgrounds). The American Dream does exist, but it is much more likely to remain only a dream unless we come from advantaged backgrounds. In fact, there is less vertical mobility in the United States than in other Western democracies. As a recent analysis summarized the evidence, “There is considerably more mobility in most of the other developed economies of Europe and Scandinavia than in the United States” (Mishel, Bernstein, & Shierholz, 2009, p. 108).

Key Takeaways

- Several ways of measuring social class exist. Functionalist and conflict sociologists disagree on which objective criteria to use in measuring social class. Subjective measures of social class, which rely on people rating their own social class, may lack some validity.

- Sociologists disagree on the number of social classes in the United States, but a common view is that the United States has four classes: upper, middle, working, and lower. Further variations exist within the upper and middle classes.

- The United States has some vertical social mobility, but not as much as several nations in Western Europe.

For Your Review

- Which way of measuring social class do you prefer, objective or subjective? Explain your answer.

- Which objective measurement of social class do you prefer, functionalist or conflict? Explain your answer.

Blau, P. M., & Duncan, O. D. (1967). The American occupational structure . New York, NY: Wiley.

Coleman, R. P., & Rainwater, L. (1978). Social standing in America . New York, NY: Basic Books.

DeNavas-Walt, C., Proctor, B. D., & Smith, J. C. (2010). Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2009 (Current Population Report P60-238). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.

Featherman, D. L., & Hauser, R. M. (1978). Opportunity and change . New York, NY: Academic Press.

Gilbert, D. (2011). The American class structure in an age of growing inequality (8th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Green, C. A., & Ferber, M. A. (2008). The long-term impact of labor market interruptions: How crucial is timing? Review of Social Economy, 66 , 351–379.

Hodge, R. W., Siegel, P., & Rossi, P. (1964). Occupational prestige in the United States, 1925–63. American Journal of Sociology, 70 , 286–302.

Kerbo, H. R. (2009). Social stratification and inequality . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Mishel, L., Bernstein, J., & Shierholz, H. (2009). The state of working America 2008/2009 . Ithaca, NY: ILR Press [An imprint of Cornell University Press].

Warner, W. L., & Lunt, P. S. (1941). The social life of a modern community . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Wright, E. O. (2000). Class counts: Comparative studies in class analysis . New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

What Is Social Stratification, and Why Does It Matter?

How Sociologists Define and Study This Phenomenon

Corbis / Getty Images

- Key Concepts

- Major Sociologists

- News & Issues

- Research, Samples, and Statistics

- Recommended Reading

- Archaeology

- Ph.D., Sociology, University of California, Santa Barbara

- M.A., Sociology, University of California, Santa Barbara

- B.A., Sociology, Pomona College

Social stratification refers to the way people are ranked and ordered in society. In Western countries, this stratification primarily occurs as a result of socioeconomic status in which a hierarchy determines the groups most likely to gain access to financial resources and forms of privilege. Typically, the upper classes have the most access to these resources while the lower classes may get few or none of them, putting them at a distinct disadvantage.

Key Takeaways: Social Stratification

- Sociologists use the term social stratification to refer to social hierarchies. Those higher in social hierarchies have greater access to power and resources.

- In the United States, social stratification is often based on income and wealth.

- Sociologists emphasize the importance of taking an intersectional approach to understanding social stratification; that is, an approach that acknowledges the influence of racism, sexism, and heterosexism, among other factors.

- Access to education—and barriers to education such as systemic racism—are factors that perpetuate inequality.

Wealth Stratification

A look at wealth stratification in the U.S. reveals a deeply unequal society in which the top 10% of households control 70% of the nation's riches , according to a 2019 study released by the Federal Reserve. In 1989, they represented just 60%, an indication that class divides are growing rather than closing. The Federal Reserve attributes this trend to the richest Americans acquiring more assets; the financial crisis that devastated the housing market also contributed to the wealth gap.

Social stratification isn't just based on wealth, however. In some societies, tribal affiliations, age, or caste result in stratification. In groups and organizations, stratification may take the form of a distribution of power and authority down the ranks. Think of the different ways that status is determined in the military, schools, clubs, businesses, and even groupings of friends and peers.

Regardless of the form it takes, social stratification can manifest as the ability to make rules, decisions, and establish notions of right and wrong. Additionally, this power can be manifested as the capacity to control the distribution of resources and determine the opportunities, rights, and obligations of others.

The Role of Intersectionality

Sociologists recognize that a variety of factors, including social class , race , gender , sexuality, nationality, and sometimes religion, influence stratification. As such, they tend to take an intersectional approach to analyzing the phenomenon. This approach recognizes that systems of oppression intersect to shape people's lives and to sort them into hierarchies. Consequently, sociologists view racism , sexism , and heterosexism as playing significant and troubling roles in these processes as well.

In this vein, sociologists recognize that racism and sexism affect one's accrual of wealth and power in society. The relationship between systems of oppression and social stratification is made clear by U.S. Census data that show a long-term gender wage and wealth gap has plagued women for decades , and though it has narrowed a bit over the years, it still thrives today. An intersectional approach reveals that Black and Latina women, who make 61 and 53 cents, respectively, for every dollar earned by a white male , are affected by the gender wage gap more negatively than white women, who earn 77 cents on that dollar , according to a report by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

Education as a Factor

Social science studies show that one’s level of education is positively correlated with income and wealth. A survey of young adults in the U.S. found that those with at least a college degree are nearly four times as wealthy as the average young person. They also have 8.3 times as much wealth as those who just completed high school. These findings show that education clearly plays a role in social stratification, but race intersects with academic achievement in the U.S. as well.

The Pew Research Center has reported that completion of college is stratified by ethnicity. An estimated 63% of Asian Americans and 41% of whites graduate from college compared to 22% of Blacks and 15% of Latinos. This data reveals that systemic racism shapes access to higher education , which, in turn, affects one's income and wealth. According to the Urban Institute , the average Latino family had just 20.9% of the wealth of the average white family in 2016. During the same timeframe, the average Black family had a mere 15.2% of the wealth of their white counterparts. Ultimately, wealth, education, and race intersect in ways that create a stratified society.

- The Sociology of Race and Ethnicity

- Biography of Patricia Hill Collins, Esteemed Sociologist

- Visualizing Social Stratification in the U.S.

- Understanding the Gender Pay Gap and How It Affects Women

- Understanding Socialization in Sociology

- What You Need to Know About Economic Inequality

- Combahee River Collective in the 1970s

- Understanding Segregation Today

- How Intervening Variables Work in Sociology

- Famous Sociologists

- How to Tell If You've Been Unintentionally Racist

- The Concept of Social Structure in Sociology

- Defining Racism Beyond its Dictionary Meaning

- Definition of Systemic Racism in Sociology

- What Is Social Class, and Why Does it Matter?

- The Sociology of Social Inequality

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

9: Social Stratification in the United States

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 164508

- 9.1: Introduction

- 9.2: What Is Social Stratification? Sociologists use the term social stratification to describe the system of social standing. Social stratification refers to a society’s categorization of its people into rankings of socioeconomic tiers based on factors like wealth, income, race, education, and power.

- 9.3: Social Stratification and Mobility in the United States Most sociologists define social class as a grouping based on similar factors like wealth, income, education, and occupation. These factors affect how much power and prestige a person has. Social stratification reflects an unequal distribution of resources. In most cases, having more money means having more power or more opportunities. Stratification can also result from physical and intellectual traits. Categories that affect social standing include ancestry, race, ethnicity, age, & gender.

- 9.4: Global Stratification and Inequality Global stratification compares the wealth, economic stability, status, and power of countries across the world. Global stratification highlights worldwide patterns of social inequality. In the early years of civilization, hunter-gatherer and agrarian societies lived off the earth and rarely interacted with other societies. When explorers began traveling, societies began trading goods, as well as ideas and customs.

- 9.5: Theoretical Perspectives on Social Stratification

- 9.6: Key Terms

- 9.7: Section Summary

- 9.8: Section Quiz

- 9.9: Short Answer

- 9.10: Further Research

- 9.11: References

Thumbnail: This house, formerly owned by the famous television producer, Aaron Spelling, was for a time listed for $150 million dollars. It is considered one of the most extravagant homes in the United States, and is a testament to the wealth generated in some industries. (Photo courtesy of Atwater Village Newbie/flickr).

Introduction to Social Stratification in the United States

Chapter outline.

Eric grew up on a farm in rural Ohio, left home to serve in the Army, and returned a few years later to take over the family farm. He moved into the same house he had grown up in and soon married a young woman with whom he had attended high school. As they began to have children, they quickly realized that the income from the farm was no longer sufficient to meet their needs. Eric, with little experience beyond the farm, accepted a job as a clerk at a local grocery store. It was there that his life and the lives of his wife and children were changed forever.

One of the managers at the store liked Eric, his attitude, and his work ethic. He took Eric under his wing and began to groom him for advancement at the store. Eric rose through the ranks with ease. Then the manager encouraged him to take a few classes at a local college. This was the first time Eric had seriously thought about college. Could he be successful, Eric wondered? Could he actually be the first one in his family to earn a degree? Fortunately, his wife also believed in him and supported his decision to take his first class. Eric asked his wife and his manager to keep his college enrollment a secret. He did not want others to know about it in case he failed.

Eric was nervous on his first day of class. He was older than the other students, and he had never considered himself college material. Through hard work and determination, however, he did very well in the class. While he still doubted himself, he enrolled in another class. Again, he performed very well. As his doubt began to fade, he started to take more and more classes. Before he knew it, he was walking across the stage to receive a Bachelor’s degree with honors. The ceremony seemed surreal to Eric. He couldn’t believe he had finished college, which once seemed like an impossible feat.

Shortly after graduation, Eric was admitted into a graduate program at a well-respected university where he earned a Master’s degree. He had not only become the first from his family to attend college but also he had earned a graduate degree. Inspired by Eric’s success, his wife enrolled at a technical college, obtained a degree in nursing, and became a registered nurse working in a local hospital’s labor and delivery department. Eric and his wife both worked their way up the career ladder in their respective fields and became leaders in their organizations. They epitomized the American Dream—they worked hard and it paid off.

This story may sound familiar. After all, nearly one in three first-year college students is a first-generation degree candidate, and it is well documented that many are not as successful as Eric. According to the Center for Student Opportunity, a national nonprofit, 89 percent of first-generation students will not earn an undergraduate degree within six years of starting their studies. In fact, these students “drop out of college at four times the rate of peers whose parents have postsecondary degrees” (Center for Student Opportunity quoted in Huot 2014).

Why do students with parents who have completed college tend to graduate more often than those students whose parents do not hold degrees? That question and many others will be answered as we explore social stratification.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology

- Authors: Heather Griffiths, Nathan Keirns

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Introduction to Sociology 2e

- Publication date: Apr 24, 2015

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-sociology

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/introduction-sociology-2e/pages/9-introduction-to-social-stratification-in-the-united-states

© Feb 9, 2022 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Social stratification is a common aspect of human life all over the world. The major social classes that are equivalently evident in the United States of America are the upper class, the middle class and the lower class. The classes play a major role in defining peoples’ lives both in the current and the future times.

The upper class is considered the top, and only the powerful elite get to see the view from there. In the United States, people with extreme wealth make up one percent of the population, and they own roughly one-third of the country’s wealth (Beeghley 2008).

Social Stratification in the United States of America: In this article, different paradigms presented by scholars like Michael Omi, Howard Winant on race, Patricia Hill Collins, Joan Acker on gender and Julian A. Pitt-Rivers on race, colour and class have been presented. Questions such as: what leads to the promotion and maintenance of these stratified pillars in the society, how does it ...

The American Class Structure. As should be evident, it is not easy to determine how many social classes exist in the United States. Over the decades, sociologists have outlined as many as six or seven social classes based on such things as, once again, education, occupation, and income, but also on lifestyle, the schools people’s children attend, a family’s reputation in the community, how ...

Social class seems to be the most appropriate type of stratification to describe inequality in America. Social stratification certainly exists in United States although most Americans believe only in the three class model – the rich, middle class and the poor. Some sociologist proposed more complex structure and yet others deny its very ...

Social stratification refers to a society’s categorization of its people into rankings based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and power. Geologists also use the word “stratification” to describe the distinct vertical layers found in rock. Typically, society’s layers, made of people, represent the uneven ...

Key Takeaways: Social Stratification. Sociologists use the term social stratification to refer to social hierarchies. Those higher in social hierarchies have greater access to power and resources. In the United States, social stratification is often based on income and wealth. Sociologists emphasize the importance of taking an intersectional ...

Social stratification refers to a society’s categorization of its people into rankings of socioeconomic tiers based on factors like wealth, income, race, education, and power. 9.3: Social Stratification and Mobility in the United States. Most sociologists define social class as a grouping based on similar factors like wealth, income ...

Figure 9.1 This house, formerly owned by the famous television producer, Aaron Spelling, was for a time listed for $150 million dollars. It is considered one of the most extravagant homes in the United States, and is a testament to the wealth generated in some industries.