- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 13, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

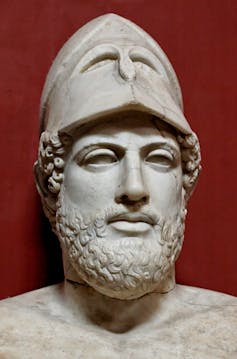

Viewed by many as the founding figure of Western philosophy, Socrates (469-399 B.C.) is at once the most exemplary and the strangest of the Greek philosophers. He grew up during the golden age of Pericles’ Athens, served with distinction as a soldier, but became best known as a questioner of everything and everyone. His style of teaching—immortalized as the Socratic method—involved not conveying knowledge, but rather asking question after clarifying question until his students arrived at their own understanding.

Socrates wrote nothing himself, so all that is known about him is filtered through the writings of a few contemporaries and followers, most notably his student Plato. Socrates was accused of corrupting the youth of Athens and sentenced to death. Choosing not to flee, he spent his final days in the company of his friends before drinking the executioner’s cup of poisonous hemlock.

Socrates: Early Years

Socrates was born and lived nearly his entire life in Athens. His father Sophroniscus was a stonemason and his mother, Phaenarete, was a midwife. As a youth, he showed an appetite for learning. Plato describes him eagerly acquiring the writings of the leading contemporary philosopher Anaxagoras and says he was taught rhetoric by Aspasia , the talented mistress of the great Athenian leader Pericles .

Did you know? Although he never outright rejected the standard Athenian view of religion, Socrates' beliefs were nonconformist. He often referred to God rather than the gods, and reported being guided by an inner divine voice .

His family apparently had the moderate wealth required to launch Socrates’ career as a hoplite (foot soldier). As an infantryman, Socrates showed great physical endurance and courage, rescuing the future Athenian leader Alcibiades during the siege of Potidaea in 432 B.C.

Through the 420s, Socrates was deployed for several battles in the Peloponnesian War , but also spent enough time in Athens to become known and beloved by the city’s youth. In 423 he was introduced to the broader public as a caricature in Aristophanes’ play “Clouds,” which depicted him as an unkempt buffoon whose philosophy amounted to teaching rhetorical tricks for getting out of debt.

Philosophy of Socrates

Although many of Aristophanes’ criticisms seem unfair, Socrates cut a strange figure in Athens, going about barefoot, long-haired and unwashed in a society with incredibly refined standards of beauty. It didn’t help that he was by all accounts physically ugly, with an upturned nose and bulging eyes.

Despite his intellect and connections, he rejected the sort of fame and power that Athenians were expected to strive for. His lifestyle—and eventually his death—embodied his spirit of questioning every assumption about virtue, wisdom and the good life.

Two of his younger students, the historian Xenophon and the philosopher Plato, recorded the most significant accounts of Socrates’ life and philosophy. For both, the Socrates that appears bears the mark of the writer. Thus, Xenophon’s Socrates is more straightforward, willing to offer advice rather than simply asking more questions. In Plato’s later works, Socrates speaks with what seem to be largely Plato’s ideas.

In the earliest of Plato’s “Dialogues”—considered by historians to be the most accurate portrayal—Socrates rarely reveals any opinions of his own as he brilliantly helps his interlocutors dissect their thoughts and motives in Socratic dialogue, a form of literature in which two or more characters (in this case, one of them Socrates) discuss moral and philosophical issues.

One of the greatest paradoxes that Socrates helped his students explore was whether weakness of will—doing wrong when you genuinely knew what was right—ever truly existed. He seemed to think otherwise: people only did wrong when at the moment the perceived benefits seemed to outweigh the costs. Thus the development of personal ethics is a matter of mastering what he called “the art of measurement,” correcting the distortions that skew one’s analyses of benefit and cost.

Socrates was also deeply interested in understanding the limits of human knowledge. When he was told that the Oracle at Delphi had declared that he was the wisest man in Athens, Socrates balked until he realized that, although he knew nothing, he was (unlike his fellow citizens) keenly aware of his own ignorance.

Trial and Death of Socrates

Socrates avoided political involvement where he could and counted friends on all sides of the fierce power struggles following the end of the Peloponnesian War. In 406 B.C. his name was drawn to serve in Athens’ assembly, or ekklesia, one of the three branches of ancient Greek democracy known as demokratia.

Socrates became the lone opponent of an illegal proposal to try a group of Athens’ top generals for failing to recover their dead from a battle against Sparta (the generals were executed once Socrates’ assembly service ended). Three years later, when a tyrannical Athenian government ordered Socrates to participate in the arrest and execution of Leon of Salamis, he refused—an act of civil disobedience that Martin Luther King Jr. would cite in his “ Letter from a Birmingham Jail .”

The tyrants were forced from power before they could punish Socrates, but in 399 he was indicted for failing to honor the Athenian gods and for corrupting the young. Although some historians suggest that there may have been political machinations behind the trial, he was condemned on the basis of his thought and teaching. In his “The Apology of Socrates,” Plato recounts him mounting a spirited defense of his virtue before the jury but calmly accepting their verdict. It was in court that Socrates allegedly uttered the now-famous phrase, “the unexamined life is not worth living.”

His execution was delayed for 30 days due to a religious festival, during which the philosopher’s distraught friends tried unsuccessfully to convince him to escape from Athens. On his last day, Plato says, he “appeared both happy in manner and words as he died nobly and without fear.” He drank the cup of brewed hemlock his executioner handed him, walked around until his legs grew numb and then lay down, surrounded by his friends, and waited for the poison to reach his heart.

The Socratic Legacy

Socrates is unique among the great philosophers in that he is portrayed and remembered as a quasi-saint or religious figure. Indeed, nearly every school of ancient Greek and Roman philosophy, from the Skeptics to the Stoics to the Cynics, desired to claim him as one of their own (only the Epicurians dismissed him, calling him “the Athenian buffoon”).

Since all that is known of his philosophy is based on the writing of others, the Socratic problem, or Socratic question–reconstructing the philosopher’s beliefs in full and exploring any contradictions in second-hand accounts of them–remains an open question facing scholars today.

Socrates and his followers expanded the purpose of philosophy from trying to understand the outside world to trying to tease apart one’s inner values. His passion for definitions and hair-splitting questions inspired the development of formal logic and systematic ethics from the time of Aristotle through the Renaissance and into the modern era.

Moreover, Socrates’ life became an exemplar of the difficulty and the importance of living (and if necessary dying) according to one’s well-examined beliefs. In his 1791 autobiography Benjamin Franklin reduced this notion to a single line: “Humility: Imitate Jesus and Socrates.”

HISTORY Vault: Ancient History

From the Sphinx of Egypt to the Kama Sutra, explore ancient history videos.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

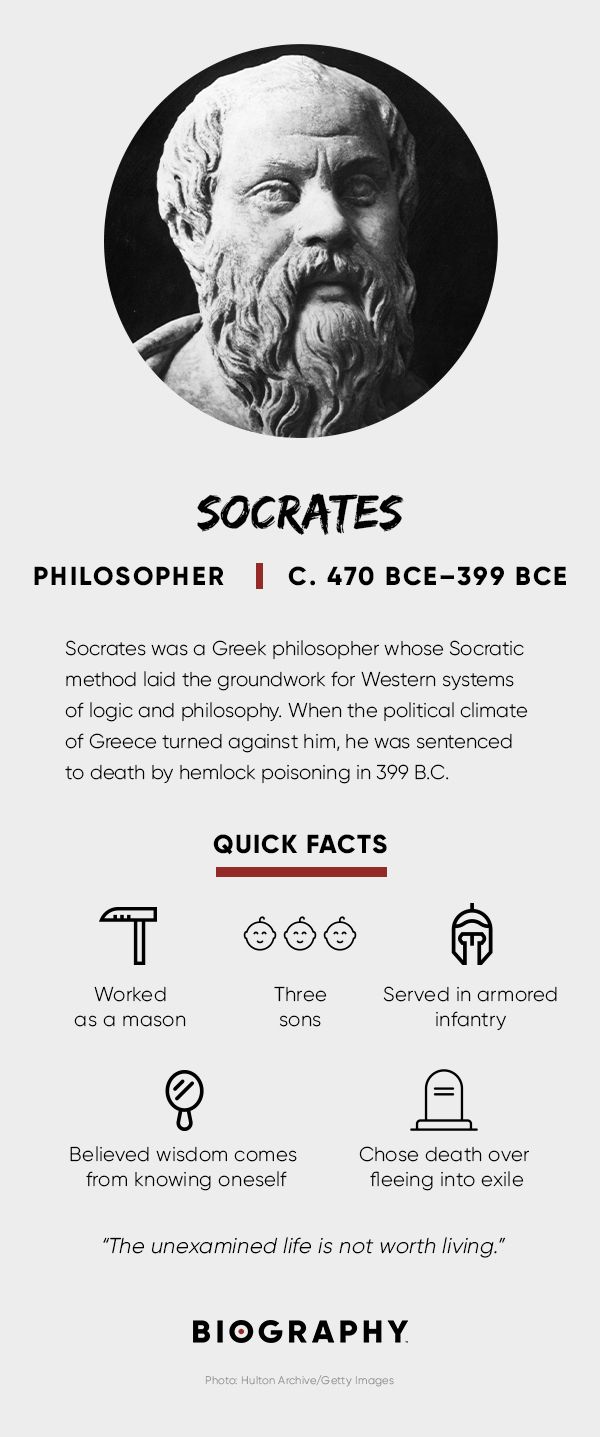

Socrates was an ancient Greek philosopher considered to be the main source of Western thought. He was condemned to death for his Socratic method of questioning.

Who Was Socrates?

When the political climate of Greece turned against him, Socrates was sentenced to death by hemlock poisoning in 399 B.C. He accepted this judgment rather than fleeing into exile.

Early Years

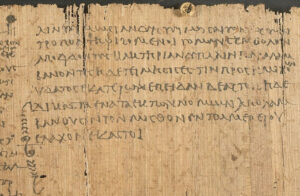

Born circa 470 B.C. in Athens, Greece, Socrates's life is chronicled through only a few sources: the dialogues of Plato and Xenophon and the plays of Aristophanes.

Because these writings had other purposes than reporting his life, it is likely none present a completely accurate picture. However, collectively, they provide a unique and vivid portrayal of Socrates's philosophy and personality.

Socrates was the son of Sophroniscus, an Athenian stonemason and sculptor, and Phaenarete, a midwife. Because he wasn't from a noble family, he probably received a basic Greek education and learned his father's craft at a young age. It's believed Socrates worked as mason for many years before he devoted his life to philosophy.

Contemporaries differ in their account of how Socrates supported himself as a philosopher. Both Xenophon and Aristophanes state Socrates received payment for teaching, while Plato writes Socrates explicitly denied accepting payment, citing his poverty as proof.

Socrates married Xanthippe, a younger woman, who bore him three sons: Lamprocles, Sophroniscus and Menexenus. There is little known about her except for Xenophon's characterization of Xanthippe as "undesirable."

He writes she was not happy with Socrates's second profession and complained that he wasn’t supporting family as a philosopher. By his own words, Socrates had little to do with his sons' upbringing and expressed far more interest in the intellectual development of Athens' other young boys.

Life in Athens

Athenian law required all able-bodied males serve as citizen soldiers, on call for duty from ages 18 until 60. According to Plato, Socrates served in the armored infantry — known as the hoplite — with shield, long spear and face mask.

He participated in three military campaigns during the Peloponnesian War , at Delium, Amphipolis and Potidaea, where he saved the life of Alcibiades, a popular Athenian general.

Socrates was known for his fortitude in battle and his fearlessness, a trait that stayed with him throughout his life. After his trial, he compared his refusal to retreat from his legal troubles to a soldier's refusal to retreat from battle when threatened with death.

Plato's Symposium provides the best details of Socrates' physical appearance. He was not the ideal of Athenian masculinity. Short and stocky, with a snub nose and bulging eyes, Socrates always seemed to appear to be staring.

However, Plato pointed out that in the eyes of his students, Socrates possessed a different kind of attractiveness, not based on a physical ideal but on his brilliant debates and penetrating thought.

Socrates always emphasized the importance of the mind over the relative unimportance of the human body. This credo inspired Plato’s philosophy of dividing reality into two separate realms, the world of the senses and the world of ideas, declaring that the latter was the only important one.

Socrates believed that philosophy should achieve practical results for the greater well-being of society. He attempted to establish an ethical system based on human reason rather than theological doctrine.

Socrates pointed out that human choice was motivated by the desire for happiness. Ultimate wisdom comes from knowing oneself. The more a person knows, the greater his or her ability to reason and make choices that will bring true happiness.

Socrates believed that this translated into politics with the best form of government being neither a tyranny nor a democracy. Instead, government worked best when ruled by individuals who had the greatest ability, knowledge and virtue, and possessed a complete understanding of themselves.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S SOCRATES FACT CARD

Socratic Method

For Socrates, Athens was a classroom and he went about asking questions of the elite and common man alike, seeking to arrive at political and ethical truths. Socrates didn’t lecture about what he knew. In fact, he claimed to be ignorant because he had no ideas, but wise because he recognized his own ignorance.

He asked questions of his fellow Athenians in a dialectic method — the Socratic Method — which compelled the audience to think through a problem to a logical conclusion. Sometimes the answer seemed so obvious, it made Socrates' opponents look foolish. For this, his Socratic Method was admired by some and vilified by others.

During Socrates' life, Athens was going through a dramatic transition from hegemony in the classical world to its decline after a humiliating defeat by Sparta in the Peloponnesian War. Athenians entered a period of instability and doubt about their identity and place in the world.

As a result, they clung to past glories, notions of wealth and a fixation on physical beauty. Socrates attacked these values with his insistent emphasis on the greater importance of the mind.

While many Athenians admired Socrates' challenges to Greek conventional wisdom and the humorous way he went about it, an equal number grew angry and felt he threatened their way of life and uncertain future.

Trial of Socrates

In 399 B.C., Socrates was accused of corrupting the youth of Athens and of impiety, or heresy. He chose to defend himself in court.

Rather than present himself as wrongly accused, Socrates declared he fulfilled an important role as a gadfly, one who provides an important service to his community by continually questioning and challenging the status quo and its defenders.

The jury was not swayed by Socrates' defense and convicted him by a vote of 280 to 221. Possibly the defiant tone of his defense contributed to the verdict and he made things worse during the deliberation over his punishment.

Athenian law allowed a convicted citizen to propose an alternative punishment to the one called for by the prosecution and the jury would decide. Instead of proposing he be exiled, Socrates suggested he be honored by the city for his contribution to their enlightenment and be paid for his services.

The jury was not amused and sentenced him to death by drinking a mixture of poison hemlock.

Socrates' Death

Before Socrates' execution, friends offered to bribe the guards and rescue him so he could flee into exile.

He declined, stating he wasn't afraid of death, felt he would be no better off if in exile and said he was still a loyal citizen of Athens, willing to abide by its laws, even the ones that condemned him to death.

Plato described Socrates' execution in his Phaedo dialogue: Socrates drank the hemlock mixture without hesitation. Numbness slowly crept into his body until it reached his heart. Shortly before his final breath, Socrates described his death as a release of the soul from the body.

"],["

"]]" tml-render-layout="inline">

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Socrates

- Birth Year: 470

- Birth City: Athens

- Birth Country: Greece

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Socrates was an ancient Greek philosopher considered to be the main source of Western thought. He was condemned to death for his Socratic method of questioning.

- Education and Academia

- Nacionalities

- Death Year: 399

- Death City: Athens

- Death Country: Greece

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

Philosophers

Francis Bacon

Auguste Comte

Charles-Louis de Secondat

Saint Thomas Aquinas

William James

John Stuart Mill

Jean-Paul Sartre

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Constantin Brancusi. Socrates Image © The Museum of Modern Art; Licensed by Scala/Art Resource, NY ©2005 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris reproduced with permission of the Brancusi Estate

The philosopher Socrates remains, as he was in his lifetime (469–399 B.C.E.), [ 1 ] an enigma, an inscrutable individual who, despite having written nothing, is considered one of the handful of philosophers who forever changed how philosophy itself was to be conceived. All our information about him is second-hand and most of it vigorously disputed, but his trial and death at the hands of the Athenian democracy is nevertheless the founding myth of the academic discipline of philosophy, and his influence has been felt far beyond philosophy itself, and in every age. Because his life is widely considered paradigmatic not only for the philosophic life but, more generally, for how anyone ought to live, Socrates has been encumbered with the adulation and emulation ordinarily reserved for religious figures – strange for someone who tried so hard to make others do their own thinking and for someone convicted and executed on the charge of irreverence toward the gods. Certainly he was impressive, so impressive that many others were moved to write about him, all of whom found him strange by the conventions of fifth-century Athens: in his appearance, personality, and behavior, as well as in his views and methods.

So thorny is the difficulty of distinguishing the historical Socrates from the Socrateses of the authors of the texts in which he appears and, moreover, from the Socrateses of scores of later interpreters, that the whole contested issue is generally referred to as the Socratic problem . Each age, each intellectual turn, produces a Socrates of its own. It is no less true now that, “The ‘real’ Socrates we have not: what we have is a set of interpretations each of which represents a ‘theoretically possible’ Socrates,” as Cornelia de Vogel (1955, 28) put it. In fact, de Vogel was writing as a new analytic paradigm for interpreting Socrates was about to become standard—Gregory Vlastos’s model (§2.2), which would hold sway until the mid 1990s. Who Socrates really was is fundamental to virtually any interpretation of the philosophical dialogues of Plato because Socrates is the dominant figure in most of Plato’s dialogues.

1. Socrates’s strangeness

2.1 three primary sources: aristophanes, xenophon, and plato, 2.2 contemporary interpretative strategies, 2.3 implications for the philosophy of socrates, 3. a chronology of the historical socrates in the context of athenian history and the dramatic dates of plato’s dialogues.

Resources for Teaching

General overviews and reference

Analytic philosophy of socrates, continental interpretations, interpretive issues, specialized studies, other internet resources, related entries.

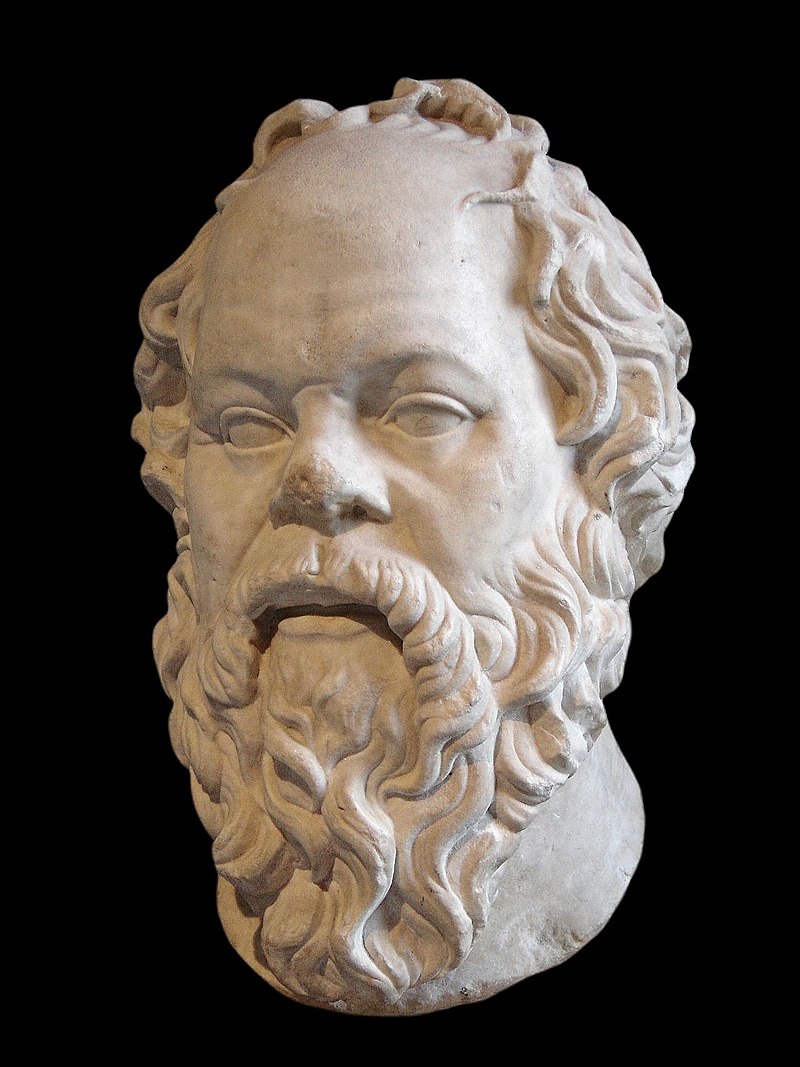

Standards of beauty are different in different eras, and in Socrates’s time beauty could easily be measured by the standard of the gods, stately, proportionate sculptures of whom had been adorning the Athenian acropolis since about the time Socrates reached the age of thirty. Good looks and proper bearing were important to a man’s political prospects, for beauty and goodness were linked in the popular imagination. The extant sources agree that Socrates was profoundly ugly, resembling a satyr more than a man—and resembling not at all the statues that turned up later in ancient times and now grace Internet sites and the covers of books. He had wide-set, bulging eyes that darted sideways and enabled him, like a crab, to see not only what was straight ahead, but what was beside him as well; a flat, upturned nose with flaring nostrils; and large fleshy lips like an ass. Socrates let his hair grow long, Spartan-style (even while Athens and Sparta were at war), and went about barefoot and unwashed, carrying a stick and looking arrogant. He didn’t change his clothes but efficiently wore in the daytime what he covered himself with at night. Something was peculiar about his gait as well, sometimes described as a swagger so intimidating that enemy soldiers kept their distance. He was impervious to the effects of alcohol and cold weather, but this made him an object of suspicion to his fellow soldiers on campaign. We can safely assume an average height (since no one mentions it at all), and a strong build, given the active life he appears to have led. Against the iconic tradition of a pot-belly, Socrates and his companions are described as going hungry (Aristophanes, Birds 1280–83). On his appearance, see Plato’s Theaetetus 143e, and Symposium 215a–c, 216c–d, 221d–e; Xenophon’s Symposium 4.19, 5.5–7; and Aristophanes’s Clouds 362. Brancusi’s oak sculpture, standing 51.25 inches including its base, captures Socrates’s appearance and strangeness in the sense that it looks different from every angle, including a second “eye” that cannot be seen if the first is in view. (See the Museum of Modern Art’s page on Brancusi’s Socrates which offers additional views.) Also true to Socrates’s reputation for ugliness, but less available, are the drawings of the contemporary Swiss artist, Hans Erni.

In the late fifth century B.C.E., it was more or less taken for granted that any self-respecting Athenian male would prefer fame, wealth, honors, and political power to a life of labor. Although many citizens lived by their labor in a wide variety of occupations, they were expected to spend much of their leisure time, if they had any, busying themselves with the affairs of the city. Men regularly participated in the governing Assembly and in the city’s many courts; and those who could afford it prepared themselves for success at public life by studying with rhetoricians and sophists from abroad who could themselves become wealthy and famous by teaching the young men of Athens to use words to their advantage. Other forms of higher education were also known in Athens: mathematics, astronomy, geometry, music, ancient history, and linguistics. One of the things that seemed strange about Socrates is that he neither labored to earn a living, nor participated voluntarily in affairs of state. Rather, he embraced poverty and, although youths of the city kept company with him and imitated him, Socrates adamantly insisted he was not a teacher (Plato, Apology 33a–b) and refused all his life to take money for what he did. The strangeness of this behavior is mitigated by the image then current of teachers and students: teachers were viewed as pitchers pouring their contents into the empty cups that were the students. Because Socrates was no transmitter of information that others were passively to receive, he resists the comparison to teachers. Rather, he helped others recognize on their own what is real, true, and good (Plato, Meno , Theaetetus )—a new, and thus suspect, approach to education. He was known for confusing, stinging, and stunning his conversation partners into the unpleasant experience of realizing their own ignorance, a state sometimes superseded by genuine intellectual curiosity.

It did not help matters that Socrates seemed to have a higher opinion of women than most of his companions had, speaking of “men and women,” “priests and priestesses,” likening his work to midwifery, and naming foreign women as his teachers: Socrates claimed to have learned rhetoric from Aspasia of Miletus, the de facto spouse of Pericles (Plato, Menexenus ); and to have learned erotics from the priestess Diotima of Mantinea (Plato, Symposium ). Socrates was unconventional in a related respect. Athenian citizen males of the upper social classes did not marry until they were at least thirty, and Athenian females were poorly educated and kept sequestered until puberty, when they were given in marriage by their fathers. Thus the socialization and education of males often involved a relationship for which the English word ‘pederasty’ (though often used) is misleading, in which a youth approaching manhood, fifteen to seventeen, became the beloved of a male lover a few years older, under whose tutelage and through whose influence and gifts, the younger man would be guided and improved. It was assumed among Athenians that mature men would find youths sexually attractive, and such relationships were conventionally viewed as beneficial to both parties by family and friends alike. A degree of hypocrisy (or denial), however, was implied by the arrangement: “officially” it did not involve sexual relations between the lovers and, if it did, then the beloved was not supposed to derive pleasure from the act—but ancient evidence (comedies, vase paintings, et al.) shows that both restrictions were often violated (Dover 1989, 204). What was odd about Socrates is that, although he was no exception to the rule of finding youths attractive (Plato, Charmides 155d, Protagoras 309a–b; Xenophon, Symposium 4.27–28), he refused the physical advances of even his favorite, Alcibiades (Plato, Symposium 219b–d), and kept his eye on the improvement of their, and all the Athenians’, souls (Plato, Apology 30a–b), a mission he said he had been assigned by the oracle of Apollo at Delphi, if he was interpreting his friend Chaerephon’s report correctly (Plato, Apology 20e–23b), a preposterous claim in the eyes of his fellow citizens. Socrates also acknowledged a rather strange personal phenomenon, a daimonion or internal voice that prohibited his doing certain things, some trivial and some important, often unrelated to matters of right and wrong (thus not to be confused with the popular notions of a superego or a conscience). The implication that he was guided by something he regarded as divine or semi-divine was all the more reason for other Athenians to be suspicious of Socrates.

Socrates was usually to be found in the marketplace and other public areas, conversing with a variety of different people—young and old, male and female, slave and free, rich and poor, citizen and visitor—that is, with virtually anyone he could persuade to join with him in his question-and-answer mode of probing serious matters. Socrates’s lifework consisted in the examination of people’s lives, his own and others’, because “the unexamined life is not worth living for a human being,” as he says at his trial (Plato, Apology 38a). Socrates pursued this task single-mindedly, questioning people about what matters most, e.g., courage, love, reverence, moderation, and the state of their souls generally. He did this regardless of whether his respondents wanted to be questioned or resisted him. Athenian youths imitated Socrates’s questioning style, much to the annoyance of some of their elders. He had a reputation for irony, though what that means exactly is controversial; at a minimum, Socrates’s irony consisted in his saying that he knew nothing of importance and wanted to listen to others, yet keeping the upper hand in every discussion. One further aspect of Socrates’s much-touted strangeness should be mentioned: his dogged failure to align himself politically with oligarchs or democrats; rather, he had friends and enemies among both, and he supported and opposed actions of both (see §3).

2. The Socratic problem: Who was Socrates really?

The Socratic problem is a rat’s nest of complexities arising from the fact that various people wrote about Socrates whose accounts differ in crucial respects, leaving us to wonder which, if any, are accurate representations of the historical Socrates. “There is, and always will be, a ‘Socratic problem’. This is inevitable,” said Guthrie (1969, 6), looking back on a gnarled history between ancient and contemporary times that is narrated in detail by Press (1996), but barely touched on below. The difficulties are increased because all those who knew and wrote about Socrates lived before any standardization of modern categories of, or sensibilities about, what constitutes historical accuracy or poetic license. All authors present their own interpretations of the personalities and lives of their characters, whether they mean to or not, whether they write fiction or biography or philosophy (if the philosophy they write has characters), so other criteria must be introduced for deciding among the contending views of who Socrates really was. A look at the three primary ancient sources of information about Socrates (§2.1) will provide a foundation for appreciating how contemporary interpretations differ (§2.2) and why the differences matter (§2.3).

One thing is certain about the historical Socrates: even among those who knew him in life, there was profound disagreement about what his actual views and methods were. This is evident in the three contemporaneous sources below; and it is hinted at in the few titles and scraps by other authors of the time who are now lumped together as ‘minor Socratics’, not for the quality of their work but because so little or none of it is extant. We shall probably never know much about their views of Socrates (see Giannantoni 1990). [ 2 ] After Socrates’s death, the tradition became even more disparate. As Nehamas (1999, 99) puts it, “with the exception of the Epicureans, every philosophical school in antiquity, whatever its orientation, saw in him either its actual founder or the type of person to whom its adherents were to aspire.”

Aristophanes (±450–±386)

Our earliest extant source—and the only one who can claim to have known Socrates in vigorous midlife—is the playwright Aristophanes. His comedy, Clouds , was produced within a year of the battle of Delium (423) at which Socrates fought as a hoplite, and when both Xenophon and Plato were infants. In the play, the character called Socrates heads a Think-o-Rama in which young men study the natural world, from insects to stars, and study slick argumentative techniques as well, lacking all respect for the Athenian sense of propriety. The actor wearing the mask of Socrates makes fun of the traditional gods of Athens (lines 247–48, 367, 423–24), mimicked later by the young protagonist, and gives naturalistic explanations of phenomena Athenians viewed as divinely directed (lines 227–33; cf. Theaetetus 152e, 153c–d, 173e–174a; Phaedo 96a–100a). Worst of all, he teaches dishonest techniques for avoiding repayment of debt (lines 1214–1302) and encourages young men to beat their parents into submission (lines 1408–46).

Comedy by its very nature is a tricky source for information about anyone. Yet, in favor of Aristophanes as a source for Socrates is that Xenophon and Plato were some forty-five years younger than Socrates, so their acquaintance could only have been during Socrates’s later years. Could Socrates really have changed so much? Can the lampooning of the younger Socrates found in Clouds and other comic poets be reconciled with Plato’s characterization of a philosopher in his fifties and sixties? Some have said yes, pointing out that the years between Clouds and Socrates’s trial (399) were years of war and upheaval, changing everyone. The Athenian intellectual freedom of which Pericles been so proud at the beginning of the war (Thucydides 2.37–39) had been eroded completely by the end (see §3). Thus, what had seemed comical a quarter century earlier, Socrates hanging in a basket on-stage, talking nonsense, was ominous in memory by then. A good reason to believe that Aristophanes’s representation of Socrates is not merely a comic exaggeration but systematically misleading in retrospect is Kenneth Dover’s view that Clouds amalgamates in one character, Socrates, features now well known to be unique to specific other fifth-century intellectuals (1968, xxxii-lvii). Perhaps Aristophanes chose Socrates to represent garden-variety intellectuals because Socrates’s physiognomy was strange enough by itself to get a laugh. Aristophanes sometimes speaks in his own voice in his plays, giving us good reason to believe he genuinely objected to social instability brought on by the freedom Athenian youths enjoyed to study with professional rhetoricians, sophists (see §1), and natural philosophers, e.g., those who, like the presocratics, studied the cosmos or nature. Such professions could be lucrative. That Socrates eschewed any earning potential in philosophy does not seem to have been significant to the great writer of comedies.

Aristophanes’s depiction of Socrates is important because Plato’s Socrates says at his trial ( Apology 18a–b, 19c) that most of his jurors have grown up believing the falsehoods attributed to him in the play. Socrates calls Aristophanes more dangerous than the three men who brought charges against him because Aristophanes had poisoned the jurors’ minds while they were young. Aristophanes did not stop accusing Socrates in 423 when Clouds placed third behind another play in which Socrates was mentioned as barefoot; rather, he soon began writing a revision, which he circulated but never produced. Complicating matters, the revision is our only extant version of the play. Aristophanes appears to have given up on reviving Clouds in about 416, but his comic ridicule of Socrates continued. Again in 414 with Birds , and in 405 with Frogs , Aristophanes complained of Socrates’s deleterious effect on the youths of the city, including Socrates’s neglect of the poets. Aristophanes even coins a verb, to socratize , conveying a range of unsavory behaviors. [ 3 ]

Xenophon (±425–±386)

Another source for the historical Socrates is the soldier-historian, Xenophon. Xenophon says explicitly of Socrates, “I was never acquainted with anyone who took greater care to find out what each of his companions knew” ( Memorabilia 4.7.1); and Plato corroborates Xenophon’s statement by illustrating throughout his dialogues Socrates’s adjustment of the level and type of his questions to the particular individuals with whom he talked. If it is true that Socrates succeeded in pitching his conversation at the right level for each of his companions, the striking differences between Xenophon’s Socrates and Plato’s is largely explained by the differences between their two personalities. Xenophon was a practical man whose ability to recognize philosophical issues is almost imperceptible, so it is plausible that his Socrates is a practical and helpful advisor. That is the side of Socrates Xenophon experienced. Xenophon’s Socrates differs additionally from Plato’s in offering advice about subjects in which Xenophon was himself experienced, but Socrates was not: moneymaking (Xenophon, Memorabilia 2.7) and estate management (Xenophon, Oeconomicus ), suggesting that Xenophon may have entered into the writing of Socratic discourses (as Aristotle labeled the genre, Poetics 1447b11) making the character Socrates a mouthpiece for his own views. His other works mentioning or featuring Socrates are Anabasis , Apology , Hellenica , and Symposium .

Something that has strengthened Xenophon’s prima facie claim as a source for Socrates’s life is his work as a historian; his Hellenica ( History of Greece ) is one of the chief sources for the period 411–362, after Thucydides’s history abruptly ends in the midst of the Peloponnesian wars. Although Xenophon tends to moralize and does not follow the superior conventions introduced by Thucydides, still it is sometimes argued that, having had no philosophical axes to grind, Xenophon may have presented a more accurate portrait of Socrates than Plato does. But two considerations have always weakened that claim: (1) The Socrates of Xenophon’s works is so pedestrian that it is difficult to imagine his inspiring fifteen or more people to write Socratic discourses in the period following his death. (2) Xenophon could not have chalked up many hours with Socrates or with reliable informants. He lived in Erchia, about 15 kilometers and across the Hymettus mountains from Socrates’s haunts in the urban area of Athens, and his love of horses and horsemanship (on which he wrote a still-valuable treatise) took up considerable time. He left Athens in 401 on an expedition to Persia and, for a variety of reasons (mercenary service for Thracians and Spartans; exile), never resided in Athens again. And now a third is in order. (3) It turns out to have been ill-advised to assume that Xenophon would apply the same criteria for accuracy to his Socratic discourses as to his histories. [ 4 ] The biographical and historical background Xenophon deploys in his memoirs of Socrates fails to correspond to such additional sources as we have from archaeology, history, the courts, and literature. The widespread use of computers in classical studies, enabling the comparison of ancient persons, and the compiling of information about each of them from disparate sources, has made incontrovertible this observation about Xenophon’s Socratic works. Xenophon’s memoirs are pastiches, several of which simply could not have occurred as presented.

Plato (424/3–347)

Philosophers have usually privileged the account of Socrates given by their fellow philosopher, Plato. Plato was about twenty-five when Socrates was tried and executed, and had probably known the old man most of his life. It would have been hard for a boy of Plato’s social class, registered in the political district (deme) of Collytus within the city walls, to avoid Socrates. The extant sources agree that Socrates was often to be found where youths of the city spent their time. Further, Plato’s representation of individual Athenians has proved over time to correspond remarkably well to both archaeological and literary evidence: in his use of names and places, familial relations and friendship bonds, and even in his rough dating of events in almost all the authentic dialogues where Socrates is the dominant figure. The dialogues have dramatic dates that fall into place as one learns more about their characters and, despite incidental anachronisms, it turns out that there is more realism in the dialogues than most have suspected. [ 5 ] The Ion , Lysis , Euthydemus , Meno , Menexenus , Theaetetus , Euthyphro , Cratylus , the frame of Symposium , Apology , Crito , Phaedo (although Plato says he was not himself present at Socrates’s execution), and the frame of Parmenides are the dialogues in which Plato had greatest access to Athenians he depicts.

It does not follow, however, that Plato represented the views and methods of Socrates (or anyone, for that matter) as he recalled them, much less as they were originally uttered. There are a number of cautions and caveats that should be in place from the start. (i) Plato may have shaped the character Socrates (or other characters) to serve his own purposes, whether philosophical or literary or both. (ii) The dialogues representing Socrates as a youth and young man took place, if they took place at all, before Plato was born and when he was a small child. (iii) One should be cautious even about the dramatic dates of Plato’s dialogues because they are calculated with reference to characters whom we know primarily, though not only, from the dialogues. (iv) Exact dates should be treated with a measure of skepticism for numerical precision can be misleading. Even when a specific festival or other reference fixes the season or month of a dialogue, or birth of a character, one should imagine a margin of error. Although it becomes obnoxious to use circa or plus-minus everywhere, the ancients did not require or desire contemporary precision in these matters. All the children born during a full year, for example, had the same nominal birthday, accounting for the conversation at Lysis 207b, odd by contemporary standards, in which two boys disagree about who is the elder. Philosophers have often decided to bypass the historical problems altogether and to assume for the sake of argument that Plato’s Socrates is the Socrates who is relevant to potential progress in philosophy. That strategy, as we shall soon see, gives rise to a new Socratic problem (§2.2).

What, after all, is our motive for reading a dead philosopher’s words about another dead philosopher who never wrote anything himself? This is a way of asking a popular question, Why do history of philosophy? —which has no settled answer. One might reply that our study of some of our philosophical predecessors is intrinsically valuable , philosophically enlightening and satisfying. When we contemplate the words of a dead philosopher, a philosopher with whom we cannot engage directly—Plato’s words, say—we seek to understand not merely what he said and assumed, but what his statements imply, and whether they are true. Others’ words can prompt the exploration of new and rich veins of philosophy. Sometimes, making such judgments about the text requires us to learn the language in which the philosopher wrote, more about his predecessors’ ideas and those of his contemporaries. The truly great philosophers, and Plato was one of them, are still capable of becoming our companions in philosophical conversation, our dialectical partners. Because he addressed timeless, universal, fundamental questions with insight and intelligence, our own understanding of such questions is heightened whether we agree or disagree. That explains Plato, one might say, but where is Socrates in this picture? Is he interesting merely as a predecessor to Plato? Some would say yes, but others would say it is not Plato’s but Socrates’s ideas and methods that mark the real beginning of philosophy in the West, that Socrates is the better dialectical guide, and that what is Socratic in the dialogues should be distinguished from what is Platonic (§2.2). But how? That again is the Socratic problem .

If it were possible to confine oneself exclusively to Plato’s Socrates, the Socratic problem would nevertheless reappear because one would soon discover Socrates himself defending one position in one Platonic dialogue, its contrary in another, and using different methods in different dialogues to boot. Inconsistencies among the dialogues seem to demand explanation, though not all philosophers have thought so (Shorey 1903). Most famously, the Parmenides attacks various theories of forms that the Republic , Symposium , and Phaedo develop and defend. In some dialogues (e.g., Laches ), Socrates only weeds the garden of its inconsistencies and false beliefs, but in other dialogues (e.g., Phaedrus ), he is a planter as well, advancing structured philosophical claims and suggesting new methods for testing those claims. There are differences on smaller matters as well. For example, Socrates in the Gorgias opposes, while in the Protagoras he supports, hedonism; the details of the relation between erotic love and the good life differ from Phaedrus to Symposium ; the account of the relation between knowledge and the objects of knowledge in Republic differs from the Meno account; despite Socrates’s commitment to Athenian law, expressed in the Crito , he vows in the Apology that he will disobey the lawful jury if it orders him to stop philosophizing. A related problem is that some of the dialogues appear to develop positions familiar from other philosophical traditions (e.g., that of Heraclitus in Theaetetus and Pythagoreanism in Phaedo ). Three centuries of efforts to solve versions of the Socratic problem are summarized in the following supplementary document:

Early Attempts to Solve the Socratic Problem

Contemporary efforts recycle bits and pieces—including the failures—of these older attempts.

The Twentieth Century

Until relatively recently in modern times, it was hoped that confident elimination of what could be ascribed purely to Socrates would leave standing a coherent set of doctrines attributable to Plato (who appears nowhere in the dialogues as a speaker). Many philosophers, inspired by the nineteenth century scholar Eduard Zeller, expect the greatest philosophers to promote grand, impenetrable schemes. Nothing of the sort was possible for Socrates, so it remained for Plato to be assigned all the positive doctrines that could be extracted from the dialogues. In the latter half of the twentieth century, however, there was a resurgence of interest in who Socrates was and what his own views and methods were. The result is a narrower, but no less contentious, Socratic problem. Two strands of interpretation dominated views of Socrates in the twentieth century (Griswold 2001; Klagge and Smith 1992). Although there has been some healthy cross-pollination and growth since the mid 1990s, the two were so hostile to one another for so long that the bulk of the secondary literature on Socrates, including translations peculiar to each, still divides into two camps, hardly reading one another: literary contextualists and analysts. The literary-contextual study of Socrates, like hermeneutics more generally, uses the tools of literary criticism—typically interpreting one complete dialogue at a time; its European origins are traced to Heidegger and earlier to Nietzsche and Kierkegaard. The analytic study of Socrates, like analytic philosophy more generally, is fueled by the arguments in the texts—typically addressing a single argument or set of arguments, whether in a single text or across texts; its origins are in the Anglo-American philosophical tradition. Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900–2002) was the doyen of the hermeneutic strand, and Gregory Vlastos (1907–1991) of the analytic.

Literary contextualism

Faced with inconsistencies in Socrates’s views and methods from one dialogue to another, the literary contextualist has no Socratic problem because Plato is seen as an artist of surpassing literary skill, the ambiguities in whose dialogues are intentional representations of actual ambiguities in the subjects philosophy investigates. Thus terms, arguments, characters, and in fact all elements in the dialogues should be addressed in their literary context. Bringing the tools of literary criticism to the study of the dialogues, and sanctioned in that practice by Plato’s own use of literary devices and practice of textual critique ( Protagoras 339a–347a, Republic 2.376c–3.412b, Ion , and Phaedrus 262c–264e), most contextualists ask of each dialogue what its aesthetic unity implies, pointing out that the dialogues themselves are autonomous, containing almost no cross-references. Contextualists who attend to what they see as the aesthetic unity of the whole Platonic corpus, and therefore seek a consistent picture of Socrates, advise close readings of the dialogues and appeal to a number of literary conventions and devices said to reveal Socrates’s actual personality. For both varieties of contextualism, the Platonic dialogues are like a brilliant constellation whose separate stars naturally require separate focus.

Marking the maturity of the literary contextualist tradition in the early twenty-first century is a greater diversity of approaches and an attempt to be more internally critical (see Hyland 2004).

Analytic developmentalism

Beginning in the 1950s, Vlastos (1991, 45–80) recommended a set of mutually supportive premises that together provide a plausible framework in the analytic tradition for Socratic philosophy as a pursuit distinct from Platonic philosophy. [ 6 ] Although the premises have deep roots in early attempts to solve the Socratic problem (see the supplementary document linked above), the beauty of Vlastos’s particular configuration is its fecundity. The first premise marks a break with a tradition of regarding Plato as a dialectician who held his assumptions tentatively and revised them constantly; rather,

- Plato held philosophical doctrines , and

- Plato’s doctrines developed over the period in which he wrote,

accounting for many of the inconsistencies and contradictions among the dialogues (persistent inconsistencies are addressed with a complex notion of Socratic irony.) In particular, Vlastos tells a story “as hypothesis, not dogma or reported fact” describing the young Plato in vivid terms, writing his early dialogues while convinced of “the substantial truth of Socrates’s teaching and the soundness of its method.” Later, Plato develops into a constructive philosopher in his own right but feels no need to break the bond with his Socrates, his “father image.” (The remainder of Plato’s story is not relevant to Socrates.) Vlastos labels a small group of dialogues ‘transitional’ to mark the period when Plato was beginning to be dissatisfied with Socrates’s views. Vlastos’s third premise is

- It is possible to determine reliably the chronological order in which the dialogues were written and to map them to the development of Plato’s views.

The evidence Vlastos uses varies for this claim, but is of several types: stylometric data, internal cross references, external events mentioned, differences in doctrines and methods featured, and other ancient testimony (particularly that of Aristotle). The dialogues of Plato’s Socratic period, called “elenctic dialogues” for Socrates’s preferred method of questioning, are Apology, Charmides, Crito, Euthyphro, Gorgias, Hippias Minor, Ion, Laches, Protagoras, and book 1 of the Republic. The developmentalists’ Platonic dialogues are potentially a discrete sequence, the order of which enables the analyst to separate Socrates from Plato on the basis of different periods in Plato’s intellectual evolution. Finally,

- Plato puts into the mouth of Socrates only what Plato himself believes at the time he writes each dialogue.

“As Plato changes, the philosophical persona of his Socrates is made to change” (Vlastos 1991, 53)—a view sometimes referred to as the “mouthpiece theory.” Because the analyst is interested in positions or doctrines (particularly as conclusions from, or tested by, arguments), the focus of analysis is usually on a particular philosophical view in or across dialogues, with no special attention given to context or to dialogues considered as wholes; and evidence from dialogues in close chronological proximity is likely to be considered more strongly confirming than that from dialogues of other developmental periods. The result of applying the premises is a firm list (contested, of course, by others) of ten theses held by Socrates, all of which are incompatible with the corresponding ten theses held by Plato (1991, 47–49).

Many analytic ancient philosophers in the late twentieth century mined the gold Vlastos had uncovered, and many of those who were productive in the developmentalist vein in the early days went on to constructive work of their own (see Bibliography).

It is a risky business to say where ancient philosophy is now, but an advantage of an entry in a dynamic reference work is that authors are allowed, nay, encouraged to update their entries to reflect recent scholarship and sea changes in their topics. For many analytic philosophers, John Cooper (1997, xiv) sounded the end of the developmentalist era when he described the early- and middle-period dialogue distinctions as “an unsuitable basis for bringing anyone to the reading of these works. To use them in that way is to announce in advance the results of a certain interpretation of the dialogues and to canonize that interpretation under the guise of a presumably objective order of composition—when in fact no such order is objectively known. And it thereby risks prejudicing an unwary reader against the fresh, individual reading that these works demand.” When he added, “it is better to relegate thoughts about chronology to the secondary position they deserve and to concentrate on the literary and philosophical content of the works, taken on their own and in relation to the others,” he proposed peace between the literary contextualist and analytic developmentalist camps. As in any peace agreement, it takes some time for all the combatants to accept that the conflict has ended—but that is where we are.

In short, one is now more free to answer, Who was Socrates really? in the variety of ways that it has been answered in the past, in one’s own well-reasoned way, or to sidestep the question, philosophizing about the issues in Plato’s dialogues without worrying too much about the long toes of any particular interpretive tradition. Those seeking the views and methods of Plato’s Socrates from the perspective of what one is likely to see attributed to him in the secondary literature (§2.2) will find it useful to consult the related entry on Plato’s shorter ethical works .

The larger column on the left below provides some of the biographical information from ancient sources with the dramatic dates of Plato’s dialogues interspersed [in boldface] throughout. In the smaller column on the right are dates of major events and persons familiar from fifth century Athenian history. Although the dates are as precise as allowed by the facts, some are estimated and controversial (Nails 2002).

This brings us to the spring and summer of 399, to Socrates’s trial and execution. Twice in Plato’s dialogues ( Symposium 173b, Theaetetus 142c–143a), fact-checking with Socrates took place as his friends sought to commit his conversations to writing before he was executed. [spring 399 Theaetetus ] Prior to the action in the Theaetetus , a young poet named Meletus had composed a document charging Socrates with the capital crime of irreverence ( asebeia ): failure to show due piety toward the gods of Athens. This he delivered to Socrates in the presence of witnesses, instructing Socrates to present himself before the king archon within four days for a preliminary hearing (the same magistrate would later preside at the pre-trial examination and the trial). At the end of the Theaetetus , Socrates was on his way to that preliminary hearing. As a citizen, he had the right to countersue, the right to forgo the hearing, allowing the suit to proceed uncontested, and the right to exile himself voluntarily, as the personified laws later remind him ( Crito 52c). Socrates availed himself of none of these rights of citizenship. Rather, he set out to enter a plea and stopped at a gymnasium to talk to some youngsters about mathematics and knowledge.

When he arrived at the king archon’s stoa, Socrates fell into a conversation about reverence with a diviner he knew, Euthyphro [399 Euthyphro ] , and afterwards answered Meletus’s charge. This preliminary hearing designated the official receipt of the case and was intended to lead to greater precision in the formulation of the charge. In Athens, religion was a matter of public participation under law, regulated by a calendar of religious festivals; and the city used revenues to maintain temples and shrines. Socrates’s irreverence, Meletus claimed, had resulted in the corruption of the city’s young men ( Euthyphro 3c–d). Evidence for irreverence was of two types: Socrates did not believe in the gods of the Athenians (indeed, he had said on many occasions that the gods do not lie or do other wicked things, whereas the Olympian gods of the poets and the city were quarrelsome and vindictive); Socrates introduced new divinities (indeed, he insisted that his daimonion had spoken to him since childhood). Meletus handed over his complaint, and Socrates entered his plea. The king-archon could refuse Meletus’s case on procedural grounds, redirect the complaint to an arbitrator, or accept it; he accepted it. Socrates had the right to challenge the admissibility of the accusation in relation to existing law, but he did not, so the charge was published on whitened tablets in the agora and a date was set for the pre-trial examination—but not before Socrates fell into another conversation, this one on the origins of words (Smith 2022). [399 Cratylus ] From this point, word spread rapidly, probably accounting for the spike of interest in Socratic conversations recorded in Theaetetus and Symposium . [399 Symposium frame] But Socrates nevertheless is shown by Plato spending the next day in two very long conversations promised in Theaetetus (210d). [399 Sophist , Statesman ]

At the pre-trial examination, Meletus paid no court fees because it was considered a public duty to prosecute irreverence. To discourage frivolous suits, however, Athenian law imposed a heavy fine on plaintiffs who failed to obtain at least one fifth of the jury’s votes, as Socrates later points out ( Apology 36a–b). Unlike closely timed jury trials, pre-trial examinations encouraged questions to and by the litigants, to make the legal issues more precise. This procedure had become essential because of the susceptibility of juries to bribery and misrepresentation. Originally intended to be a microcosm of the citizen body, juries by Socrates’s time were manned by elderly, disabled, and impoverished volunteers who needed the meager three-obol pay.

In the month of Thargelion [May-June 399 Apology ] a month or two after Meletus’s initial summons, Socrates’s trial occurred. On the day before, the Athenians had launched a ship to Delos, dedicated to Apollo and commemorating Theseus’s legendary victory over the Minotaur ( Phaedo 58a–b). Spectators gathered along with the jury ( Apology 25a) for a trial that probably lasted most of the day, each side timed by the water clock. Plato does not provide Meletus’s prosecutorial speech or those of Anytus and Lycon, who had joined in the suit; or the names of witnesses, if any ( Apology 34a implies Meletus called none). Apology —the Greek ‘ apologia ’ means ‘defense’—is not edited as are the court speeches of orators. For example, there are no indications in the Greek text (at 35d and 38b) that the two votes were taken; and there are no breaks (at 21a or 34b) for witnesses who may have been called. Also missing are speeches by Socrates’s supporters; it is improbable that he had none, even though Plato does not name them.

Socrates, in his defense, mentioned the harm done to him by Aristophanes’s Clouds (§2.1). Though Socrates denied outright that he studied the heavens and what is below the earth, his familiarity with the investigations of natural philosophers and his own naturalistic explanations of such phenomena as earthquakes and eclipses make it no surprise that the jury remained unpersuaded. And, seeing Socrates out-argue Meletus, the jury probably did not make fine distinctions between philosophy and sophistry. Socrates three times took up the charge that he corrupted the young, insisting that, if he corrupted them, he did so unwillingly; but if unwillingly, he should be instructed, not prosecuted ( Apology 25e–26a). The jury found him guilty. By his own argument, however, Socrates could not blame the jury, for it was mistaken about what was truly in the interest of the city (cf. Theaetetus 177d–e) and thus required instruction.

In the penalty phase of the trial, Socrates said, “If it were the law with us, as it is elsewhere, that a trial for life should not last one but many days, you would be convinced, but now it is not easy to dispel great slanders in a short time” ( Apology 37a–b). This isolated complaint stands opposed to the remark of the personified laws that Socrates was “wronged not by us, the laws, but by men” ( Crito 54c). It had been a crime since 403/2 for anyone even to propose a law or decree in conflict with the newly inscribed laws, so it was ironic for the laws to tell Socrates to persuade or obey them ( Crito 51b–c). In a last-minute capitulation to his friends, he offered to allow them to pay a fine of six times his net worth (Xenophon Oeconomicus 2.3.4–5), thirty minae . The jury rejected the proposal. Perhaps the jury was too incensed by Socrates’s words to vote for the lesser penalty; after all, he needed to tell them more than once to stop interrupting him. It is more likely, however, that superstitious jurors were afraid that the gods would be angry if they failed to execute a man already found guilty of irreverence. Sentenced to death, Socrates reflected that it might be a blessing: either a dreamless sleep, or an opportunity to converse in the underworld.

While the sacred ship was on its journey to Delos, no executions were allowed in the city. Although the duration of the annual voyage varied with conditions, Xenophon says it took thirty-one days in 399 ( Memorabilia 4.8.2); if so, Socrates lived thirty days beyond his trial, into the month of Skirophorion. A day or two before the end, Socrates’s childhood friend Crito tried to persuade Socrates to escape. [June–July 399 Crito ] Socrates replied that he “listens to nothing … but the argument that on reflection seems best” and that “neither to do wrong or to return a wrong is ever right, not even to injure in return for an injury received” ( Crito 46b, 49d), not even under threat of death (cf. Apology 32a), not even for one’s family ( Crito 54b). Socrates could not point to a harm that would outweigh the harm he would be inflicting on the city if he now exiled himself unlawfully when he could earlier have done so lawfully ( Crito 52c); such lawbreaking would have confirmed the jury’s judgment that he was a corrupter of the young ( Crito 53b–c) and brought shame on his family and friends.

The events of Socrates’s last day, when he “appeared happy both in manner and words as he died nobly and without fear” ( Phaedo 58e) were related by Phaedo to the Pythagorean community at Phlius some weeks or months after the execution. [June–July 399 Phaedo ] The Eleven, prison officials chosen by lot, met with Socrates at dawn to tell him what to expect ( Phaedo 59e–60b). When Socrates’s friends arrived, Xanthippe and their youngest child, Menexenus, were still with him. Xanthippe commiserated with Socrates that he was about to enjoy his last conversation with his companions; then, performing the ritual lamentation expected of women, was led home. Socrates spent the day in philosophical conversation, defending the soul’s immortality and warning his companions not to restrain themselves in argument, “If you take my advice, you will give but little thought to Socrates but much more to the truth. If you think that what I say is true, agree with me; if not, oppose it with every argument” ( Phaedo 91b–c). On the other hand, he warned them sternly to restrain their emotions, “keep quiet and control yourselves” ( Phaedo 117e).

Socrates had no interest in whether his corpse was burned or buried, but he bathed at the prison’s cistern so the women of his household would be spared from having to wash his corpse. After meeting with his family again in the late afternoon, he rejoined his companions. The servant of the Eleven, a public slave, bade Socrates farewell by calling him “the noblest, the gentlest, and the best” of men ( Phaedo 116c). The poisoner described the physical effects of the Conium maculatum variety of hemlock used for citizen executions (Bloch 2001), then Socrates cheerfully took the cup and drank. Phaedo, a former slave echoing the slave of the Eleven, called Socrates, “the best, … the wisest and the most upright” ( Phaedo 118a).

4. Socrates outside philosophy

Socrates is an inescapable figure in intellectual history worldwide. Readers interested in tracking this might start with Trapp’s two volumes (2007). Strikingly, Socrates is invoked also in nonacademic contexts consistently over centuries, across geographical and linguistic boundaries globally, and throughout a wide range of media and forms of cultural production.

Though not commonplace today, Socrates was once routinely cited alongside Jesus. Consider Benjamin Franklin’s pithy maxim in his Autobiography, “Humility: Imitate Jesus and Socrates,” and the way the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., defends civil disobedience in Letter from Birmingham Jail by arguing that those who blame him for bringing imprisonment on himself are like those who would condemn Socrates for provoking the Athenians to execute him or condemn Jesus for having triggered his crucifixion. In the visual arts, artist Bror Hjorth celebrates Walt Whitman by giving him Jesus and Socrates as companions. This wood relief, Love, Peace and Work, was commissioned in the early 1960s by the Swedish Workers’ Educational Association for installation in its new building in Stockholm and was selected to appear on a 1995 postage stamp. A more light-hearted linking is Greece’s entry into the 1979 Eurovision Song Contest, Elpida’s Socrates Supersta r, the lyrics of which mention that Socrates was earlier than Jesus.

At times, commending Socrates asserted the distinctiveness of Western Civilization. For example, an illustrated essay on Socrates inaugurates a 1963 feature called “They Made Our World” in LOOK , a popular U.S. magazine. Today Socrates remains an icon of the Western ideal of an intellectual and is sometimes invoked as representative of the ideal of a learned person more universally. Whether he is being poked fun at, extolled, pilloried, or just acknowledged, Socrates features in a wide range of projects intended for broad audiences as a symbol of the very idea of the life of the mind, which, necessarily from a Socratic viewpoint, is also a moral life (but not necessarily a conventionally successful life).

There may be no more succinct expression of this standing than James Madison’s comments on the tyrannical impulses of crowds in Federalist 55: “Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates; every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob.” The persistence of this position in the cultural imagination is clear in his many appearances as a sober knower (e.g., Roberto Rossellini’s 1971 film) and a giant among giants, as in, for example, his imagined speech, penned by Gilbert Murray, where he is placed first among the “immortals” featured in the 1953 recording, This I Believe ,compiled by journalist Edward R. Murrow and linked to his wildly successful radio broadcast of the same name. But Socrates also persistently appears in funny settings. For example, an artist makes the literally brainless, good-natured scarecrow featured in the 1961 animation, Tales from the Wizard of Oz , answer to the name ‘Socrates’; and the Beatles make Jeremy Hillary Boob, Ph.D., their sweet fictional character in the 1968 film Yellow Submarine , respond to a question with the quip, “A true Socratic query, that!” A more robust recent example that mobilizes the longevity of Socrates’ association with reflection and ethical behavior is Walter Mosley’s crime fiction featuring Socrates Fortlow. His three books follow a Black ex-con in Los Angeles with a violent past and a fierce determination to live life as a thinking person and to do good; the character says his mother named him ‘Socrates’ because she wanted him to grow up smart, a reference to a naming custom practiced by former slaves. The association of Socrates with great intellect and moral rectitude is still kicking, as a quick glance at the collection of Socrates-themed merchandise available from a wide array of vendors will attest. Further, in the mode of “the exception proves the rule,” observe that in DC Comics, Mr. Socrates is a criminal genius able to control Superman by subduing him with a device that disables him mentally.

In antiquity, Socrates did not act as a professional teacher of doctrines; he did, however, self-identify as a knowledge-seeker for the sake of himself and the benefit of those with whom he engaged, young or not. So firmly entrenched internationally in today’s vernacular is his association with education that his name is used to brand professional enterprises as varied as curricula designed for elementary school, college, law school, institutional initiatives that serve multiple disciplines, think tank retreats, café gatherings, electronic distance learning platforms, training programs for financial and marketing consultants, some parts of cognitive behavioral therapy, and easy-to-use online legal services. We find a less commercial example in Long Walk to Freedom (1994) in which the great South African statesman Nelson Mandela reports that, during his incarceration for anti-apartheid activism, his fellow prisoners educated themselves while laboring in rock quarries and that “the style of teaching was Socratic in nature;” a leader would pose a question for them to discuss in study sessions. Another example is Elliniko Theatro’s S ocrates Now, a solo performance based on Plato’s Apology that integrates audience discussion.

In U.S. education at all levels these days, Socratic questioning implies no effort on the part of a leading figure to elicit from the participants any severe discomfort with current opinions (that is, to sting like a gadfly or to expose a disquieting truth), but instead uses the name ‘Socrates’ to invest with gravitas collaborative learning that addresses moral questions and relies on interactive techniques. The unsettling and dangerous aspects of Socratic practice turn up in politicized contexts where a distinction between dissent and disloyalty is at issue. Appeals to Socrates in these settings most often highlight the personal risks run by an intellectually exemplary critic of the unjust acts of an established authority. This is a recurring theme in politically minded allusions to Socrates globally. A wave of such work took hold in the U.S., Britain and Canada around WWII, the McCarthy Era, and Cold War. Creative artists in literature, radio, theater, and television summoned Socrates to probe what it means to be an unyielding advocate of free speech and free inquiry—even a martyr to belief in the necessity of these freedoms to meaningful and virtuous human life. In these sources, his strange appearance, behavior, and views, especially his relentlessly critical, even irritating, truth-seeking, and anti-ideological posture are presented as testing Athenian democracy’s capacity to abide by these ideals. They suggest that the indictment, trial, and execution are stains on Athenian democracy and that a worrisome historical parallel is unfolding. These full-blown interpretations of the life of Socrates require wrestling with the whole issue of the historical Socrates; a claim to historical accuracy was a crucial part of any case for his story’s being credible as a warning.

Visually, we find monuments and other sculptural tributes to a less overtly political Socrates in cities and small towns across the globe in public spaces devoted to learning and contemplation. A stand-out for its unusual focus is Antonio Canova’s 1797 bas-relief, “Socrates rescues Alcibiades in the battle of Potidaea,” in which Socrates strikes a powerful pose as a hoplite. An 1875 piece by Russian imperial sculptor Mark Antokolski foregrounds the personal cost of Socrates’s commitment to philosophy, portraying him alone, a drained cup of hemlock at his side, slumped over dead. Reproductions of, and drawings based on, ancient copies of what are thought to be a fourth-century B.C.E. statue of Socrates by the Athenian Lysippus (e.g., the British Museum’s Statuette of Socrates) are also in wide circulation. A particularly interesting one can be found in graphic artist Ralph Steadman’s Paranoids , a 1986 book of Polaroid caricatures of famous people. But the most influential image of the philosopher today is the riveting, widely reproduced, 1787 painting, “The Death of Socrates,” by Jacques Louis David, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It captures the philosopher’s own claim to be reverent, his courageous decision to take the cup of hemlock in his own hand, and the grief his unjust fate stirred in others.

David’s neo-classical history-painting has come to be a defining image of Socrates. This is curious because, while the design of the painting abounds with careful references to the primary sources, it ignores those sources’ description of Socrates himself — the ones cited in section 1 on Socrates’s strangeness — rendering the old philosopher classically handsome instead. Attending to the primary sources has led some readers to wonder whether Socrates might have had an African heritage. For example, in the 1921 “The Foolish and the Wise: Sallie Runner is Introduced to Socrates,” a short story in the NAACP journal edited by W. E. B. Du Bois, author Leila Amos Pendleton tackles the issue. Her character, a bright girl employed as a maid, responds to her employer’s account of the physical appearance of the great man born before Jesus that Miss Audrey intends to tell Sallie all about: “He was a cullod gentmun, warn’t he?” This prompts the following exchange: “Oh no, Sallie, he wasn’t colored.” “Wal, ef he been daid all dat long time, Miss Oddry, how kin yo’ tell his color?” “Why he was an Athenian, Sallie. He lived in Greece.” Nails (1989) depicted Socrates as an African village elder in a recreation of Republic 1. In the visual arts, drawings and watercolors by the Swiss artist Hans Erni resolutely portray Socrates as ugly as the sources describe him. Socrates also sometimes resonates as Black (or queer, or touched), independent of any discussion of physical attributes; this follows from his renown for refusing to be defined by the stultifying norms of his day.

In Plato’s Phaedo , Socrates says a recurring dream instructs him to “compose music and work at it” and that he had always interpreted it to mean something like keep doing philosophy because “philosophy was the greatest kind of music and that’s what I was working at” (60e–61a). In prison awaiting execution, he says he experimented with new ways of doing philosophy; he tried turning some of Aesop’s fables into verse. We might view some of the deeply thoughtful, even loving, engagements with Socrates in music and dance in light of this passage. “Socrates” is the fifth movement of Leonard Bernstein’s Serenade after Plato’s Symposium (1954). He is the explicit inspiration for two works of choreography by Mark Morris, Death of Socrates in 1983, and Socrates in 2010, both of which work with 1919 compositions by Erik Satie that directly reference Socrates. And we have a work produced in 2022 at HERE in New York, The Hang, the stunning product of a collaboration by playwright Taylor Mac and composer Matt Ray.

Conjurings of Socrates appear outside philosophy as both brief but dense references to discrete features of this puzzling figure, and sustained portraits that wrestle with his enigmatic character. Details of the sources mentioned above, and other sources that may be useful, are included in the following supplementary document.

- Ahbel-Rappe, Sara, and Rachana Kamtekar (eds.), 2005, A Companion to Socrates , Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- Bussanich, John, and Nicholas D. Smith (eds.), 2013, The Bloomsbury Companion to Socrates , London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Cooper, John M. (ed.), 1997, Plato: Complete Works , Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

- Giannantoni, Gabriele, 1990, Socratis et Socraticorum Reliquiae . 4 vols. Elenchos 18. Naples, Bibliopolis.

- Guthrie, W. K. C., 1969, A History of Greek Philosophy III, 2: Socrates , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nails, Debra, 2002, The People of Plato: A Prosopography of Plato and Other Socratics , Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

- Morrison, Donald R., 2010, The Cambridge Companion to Socrates , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rudebusch, George, 2009, Socrates , Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Taylor, A[lfred] E[dward], 1952, Socrates , Boston: Beacon.

- Trapp, Michael (ed.), 2007, Socrates from Antiquity to the Enlightenment and Socrates in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries , London: Routledge.

- Vander Waerdt (ed.), 1994, The Socratic Movement , Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Waterfield, Robin, 2009, Why Socrates Died , New York: Norton.

- Benson, Hugh H. 2000, Socratic Wisdom: The Model of Knowledge in Plato’s Early Dialogues , New York: Oxford University Press.

- –––, 2015, Clitophon’s Challenge: Dialectic in Plato’s Meno, Phaedo, and Republic, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Benson, Hugh H., (ed.), 1992, Essays on the Philosophy of Socrates , New York: Oxford University Press.

- Beversluis, John, 2000, Cross-Examining Socrates: A Defense of the Interlocutors in Plato’s Early Dialogues , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brickhouse, Thomas C., and Nicholas D. Smith, 1989, Socrates on Trial , Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- –––, 1994, Plato’s Socrates , New York: Oxford University Press.

- –––, 2015, “Socrates on the Emotions” Plato: The Internet Journal of the International Plato Society , Volume 15 [ available online ].

- Burnyeat, M[yles] F., 1998, “The Impiety of Socrates,” Ancient Philosophy , 17: 1–12.

- Jones, Russell E., 2013, “Felix Socrates?” Philosophia (Athens), 43: 77–98 [ available online ].

- Nehamas, Alexander, 1999, Virtues of Authenticity , Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Penner, Terry, 1992, “Socrates and the Early Dialogues,” in Richard Kraut (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Plato , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Santas, Gerasimos, 1979, Socrates: Philosophy in Plato’s Early Dialogues , Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Teloh, Henry, 1986, Socratic Education in Plato’s Early Dialogues , Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Vlastos, Gregory, 1954, “The Third Man Argument in Plato’s Parmenides ,” Philosophical Review 63: 319–49.

- –––, 1983, “The Historical Socrates and Athenian Democracy,” Political Theory , 11: 495–516.

- –––, 1989, “Socratic Piety,” Proceedings of the Boston Area Colloquium in Ancient Philosophy , 5: 213–38.

- –––, 1991, Socrates: Ironist and Moral Philosopher , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bloom, Allan, 1974, “Leo Strauss September 20, 1899–October 18, 1973,” Political Theory , 2(4): 372–92.

- Gadamer, Hans-Georg, 1980, Dialogue and Dialectic: Eight Hermeneutical Studies on Plato , tr. from the German by P. Christopher Smith, New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Heidegger, Martin, 1997, Plato’s Sophist , tr. from the German by Richard Rojcewicz and Andre Schuwer, Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Hyland, Drew A., 2004, Questioning Platonism: Continental Interpretations of Plato , Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Kierkegaard, Søren, 1989, The Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates , tr. from the Danish by H. V. Hong and E. H. Hong, Princeton: Princeton University Press.