Content Search

Philippines + 1 more

Who are the real-life heroes in the time of COVID-19?

- HCT Philippines

Attachments

By Gustavo Gonzalez

On World Humanitarian Day (WHD), 19 August, we celebrate and honor frontline workers, who, despite the risks, continue to provide life-saving support and protection to people most in need. On this day, we also commemorate humanitarians killed, harassed, and injured while performing their duty. This year’s theme is “Real-Life Heroes”.

But, what does it mean to be a hero? What does it take to help those in need, the poor and at-risk communities, those who are most vulnerable when a disaster strike? Why should we hold up as heroic the deeds of those who everyday continue to extend a helping hand?

As I write this, I am mourning the death of a UN colleague. He died last Friday, struck down by COVID-19, at the age of 32. As a team member of the UN’s Migration Agency, he showed exemplary dedication and commitment to the situation of migrants amidst this pandemic.

He was a true frontline hero, and he is not alone.

In these extraordinary times, and despite the very real danger to themselves, Filipino front line workers, like my fallen colleague, everyday put their own safety and well-being aside to provide life-saving support and protection to people most in need.

In the Philippines, every day since the beginning of the year, humanitarian workers have stood on the front lines dealing with the challenges arising from COVID-19 and other disaster events, like the displacement from the Taal Volcano eruption, the damage wrought by Typhoon Ambo, as well as continuing relief efforts in Marawi City and responding to those affected by the Cotabato and Davao Del Sur earthquakes. Despite the many risks, humanitarians continue to do their work, diligently and selflessly providing assistance to those who need it most.

Through years of responding to various emergencies and capitalizing on national expertise and capacity, the humanitarian community in the country has embraced a truly localized approach by recognizing what at-risk communities themselves can do in these challenging times. The private sector in the Philippines has also stepped up in sharing its resources and capabilities, joining with other humanitarian actors to support affected local governments and communities.

As we give recognition to local real-life heroes, we also need to protect and keep them free from harassment, threats, intimidation and violence. Since 2003, some 4,961 humanitarians around the world have been killed, wounded or abducted while carrying out their life-saving duties. In 2019 alone, the World Health Organization reported 1,009 attacks against health-care workers and facilities, resulting in 199 deaths and 628 injuries.

The COVID-19 pandemic has unveiled an important number of vulnerabilities as well as exposed our weaknesses in preventing shocks. It has also shown that the magnitude of the challenge is exceeding the response capacity of any single partner or country. It represents, in fact, one of the most dramatic calls to work together. The success of this battle will greatly rely on our capacity to learn from experience and remain committed to the highest humanitarian values. Our real-life heroes are already giving the example.

On 4 August, a revised version of the largest international humanitarian response plan in the country since Typhoon Yolanda in 2013 was released by the United Nations and humanitarian partners in the Philippines. Some 50 country-based UN and non-governmental partners are contributing to the response, bringing together national and international NGOs, faith-based organizations as well as the private sector.

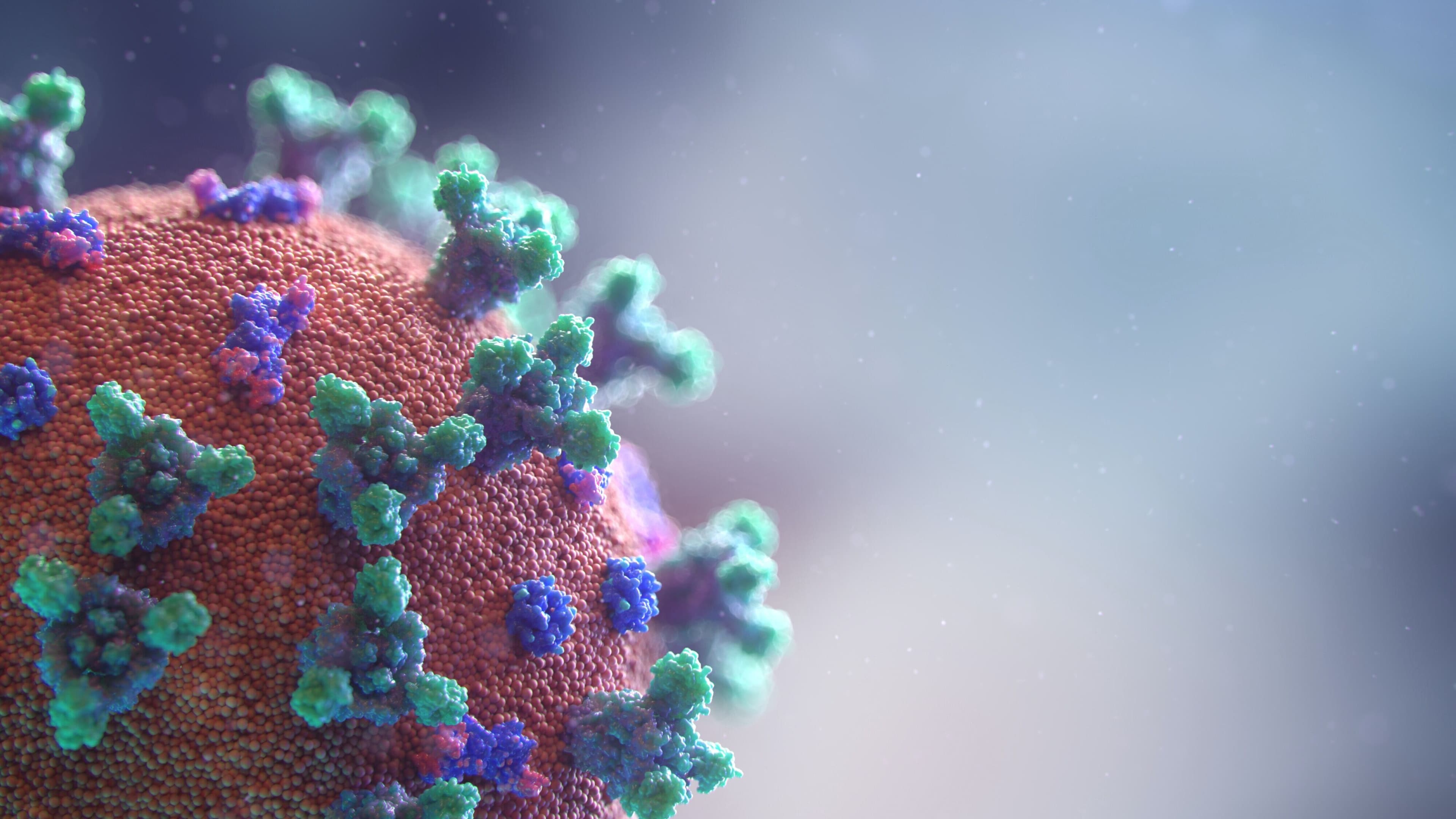

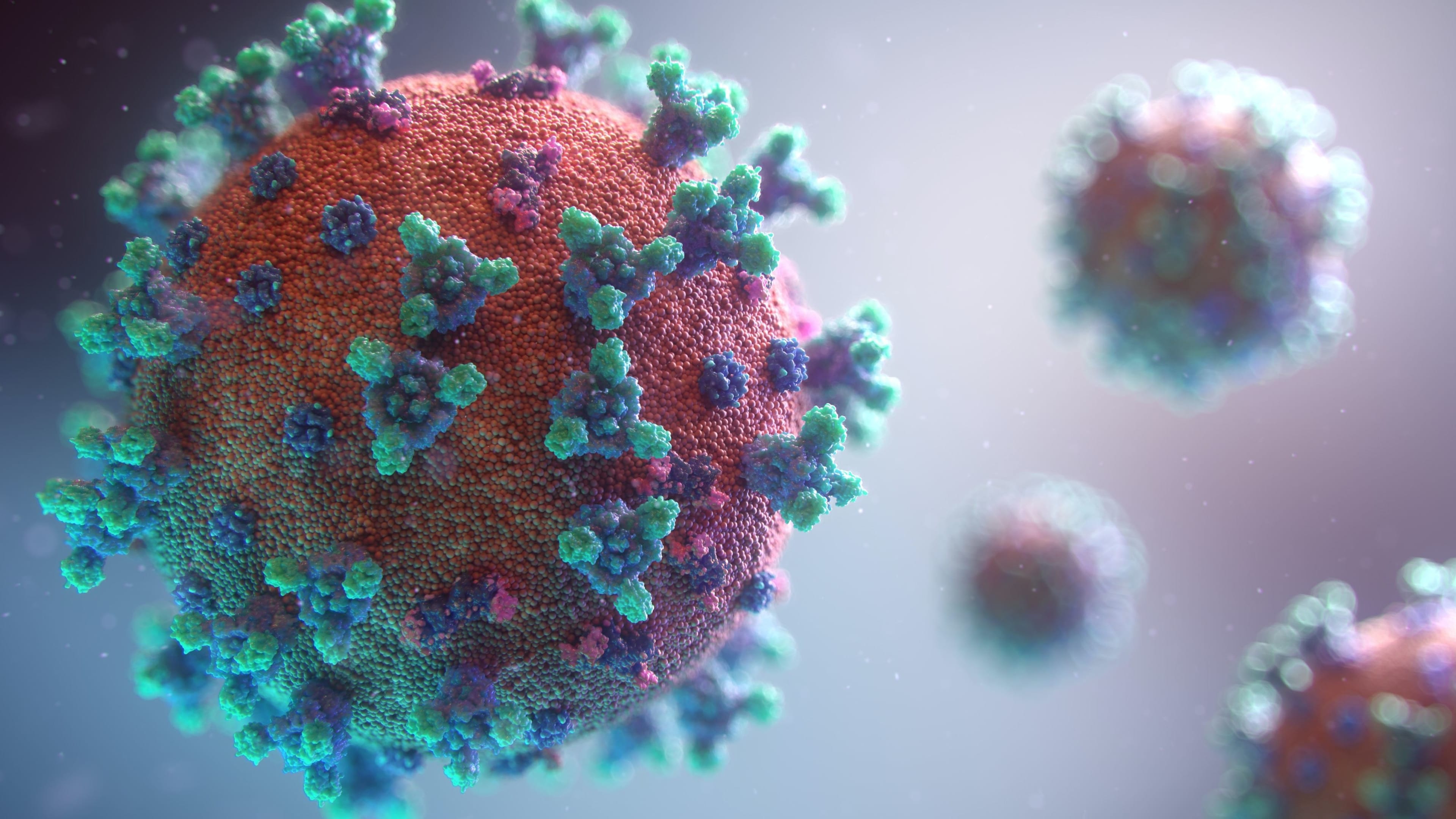

COVID-19 might be today’s super-villain, but it does not deter our real-life heroes from doing their job and tirelessly working to find ways to combat the threat and eventually beat the invisible nemesis. We mourn the thousands who have lost their lives to the virus across the globe, including my colleague whom I have spoken of.

At the same time, we join Filipinos in upholding—in the midst of great adversity-- the tradition of celebrating the best of human kindness, generosity, social justice, human rights, solidarity and Bayanihan spirit. We celebrate what makes our front liners and humanitarian real-life heroes. We salute them for continuously putting their lives on the line, despite the risks and uncertainties.

Their efforts must not be overlooked or forgotten.

Mabuhay ang Real-life Heroes! Happy World Humanitarian Day!

Gustavo Gonzalez is the United Nations Resident Coordinator and Humanitarian Coordinator in the Philippines

Related Content

World + 14 more

Policy Brief on the Security Council’s Consideration of the Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict (2019 - 2023)

World + 3 more

World Health Day: Health Workers are Under Attack Worldwide

Unicef deputy executive director ted chaiban’s remarks at the un security council briefing on children and armed conflict, who director-general's opening remarks at the media briefing - 3 april 2024 [en/ar].

Hail the warriors in white gowns

Widely praised as heroes for boosting the country's recovery rate from Covid-19, Thai health workers battling at the frontlines are the Post's person of the year

PUBLISHED : 29 Dec 2020 at 04:00

NEWSPAPER SECTION: News

WRITER: Apinya Wipatayotin and Anchalee Kongrut

In every crisis, there is a hero. And for the annus horibilis 2020, no one deserves the "Person of The Year" title more than the "Warriors in White Gowns" -- a term which the public use to praise medical workers and over a million health volunteers on the frontlines of looking after the ill.

These health workers have been a buttress in the war against Covid-19. The war started in Thailand on Jan 4 -- the day when the Department of Diseases Control opened its Emergency Operation Center (EOC).

The early days of the battle were married with problems -- a shortage of surgical masks amid collective fear and panic among people. Health workers managed to work calmly and stoically, risking their health on the frontlines.

Their sacrifice and grace under fire became a major source of hope and trust that somehow the country could survive the pandemic. People listened to the Public Health Ministry's advice.

On March 29, people across the country paid tribute to the warriors in white gowns by giving them a big round of applause for five minutes, expressing appreciation for their hard work.

According to the Global Covid-19 Index (GCI) released in July, Thailand is among nations with the highest Covid-19 recovery rate.

The performance of our healthcare workers did not only win the hearts of ordinary Thais.

In November, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director of the World Health Organization (WHO), praised Thailand as "an excellent example" of fighting the coronavirus.

In a tweet on Nov 14, the WHO director wrote: "Thailand is an excellent example of how #COVID19 can be contained with a comprehensive approach -- even without a vaccine. Bravo."

It was no accident, according to WHO's director. The country's impressive performance was the outcome of the country's consistent investment in public health over the past few decades. The investment paid off when it counted the most.

The decentralised public health care system enables medical workers, nurses and volunteers to reach every community. The best example is perhaps Mae Sot Hospital. In November, the district faced a partial lockdown as doctors managed to trace over 10,000 at-risk people and contain the disease from spreading.

But the secret weapon was village health volunteers. The Ministry of Public Health, served as coordinator and messenger between community villagers and state health officials. During Covid-19, these volunteers helped the ministry monitor Covid-19 in communities and educated people on how to protect themselves from the disease.

In May, the ministry launched a nationwide campaign, sending over one million village health workers to knock on 13 million houses, to educate locals about Covid-19 and monitor the disease at household level.

The ministry since May has contracted local manufacturers to supply masks and other items items to make sure health workers would not be affected by a shortage of protective equipment.

It has also ordered Favipiravir, one of the drugs used to treat Covid-19 patients.

In mid-year, the ministry order vaccines developed by the team from the University of Oxford and the pharmaceutical firm, AstraZeneca. It also secured a contract to produce the vaccine formula locally in Phathum Thani, for sale to Asean nations.

But the warriors in white gowns did not only fight the disease. While health workers work at the frontlines, doctors at the ministry are trying to win the war on information.

Amid mass panic and misinformation, the Centre for Covid-19 Situation Administration (CCSA) opened in April, launching daily press briefings on Covid-19.

The CCSA recruited professionals to work as volunteers -- professors in mass media and communications, and corporate PR executives to help the doctors with scripts and presentation.

Another noteworthy move was the decision to choose Taweesilp Visanuyothin as spokesman.

A psychologist at the Department of Mental Health, he knows how to deal with public fear and frustration and how to inspire trust among the public. Now, the CCSA is regarded as an authoritative and reliable source of information on Covid-19.

Apparently, the warriors in white gowns have won the war on information. The war against Covid-19 is far from over. After several months in which infection rates were low, the health workers returned to the battlefield this month as infections spiked.

The number of cases now exceeds 6,000 cases in total, with a total of 60 fatalities and only three seriously ill patients on a respirator.

The infection rate looks formidable, yet health workers calmly follow the playbook -- tracing, testing and containing risk areas.

It is hard to know when Thailand will win the war against Covid-19. But with the warriors in night gowns at work, Thais know they are in good hands.

A medical team from Mongkutwattana General Hospital collects swab samples from an elderly man at a mobile clinic in Pin Charoen 2 community in Don Muang district. Apichit Jinakul

RECOMMENDED

Heavy songkran traffic in korat, ferrari roma spider clinches top red dot award, illegal overseas worker kills daughter, 10, chinese teen jumps from car to seek police help, hat yai welcomes influx of malaysian revellers.

How to save the pandemic treaty

Covid outbreak at prachuap prison, flu, dengue fever pose risk.

12 Photo Essays Highlight the Heroes and Heartaches of the Pandemic

Pictures piece together a year into the COVID-19 pandemic.

Photos: One Year of Pandemic

Getty Images

A boy swims along the Yangtze river on June 30, 2020 in Wuhan, China.

A year has passed since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic on March, 11, 2020. A virus not visible to the human eye has left its mark in every corner of the world. No single image can define the loss and heartache of millions of global citizens, but photojournalists were there to document the times as best they could. From the exhaustion on the faces of frontline medical workers to vacant streets once bustling with life, here is a look back at photo essays published by U.S. News photo editors from the past year. When seen collectively, these galleries stitch together a year unlike any other.

In January of 2020, empty streets, protective masks and makeshift hospital beds became the new normal in Wuhan, a metropolis usually bustling with more people than New York City. Chinese authorities suspended flights, trains and public transportation, preventing locals from leaving the area, and placing a city of 11 million people under lockdown. The mass quarantine invokes surreal scenes and a grim forecast.

Photos: The Epicenter of Coronavirus

Photojournalist Krisanne Johnson documented New Yorkers in early March of 2020, during moments of isolation as a climate of uncertainty and tension hung over the city that never sleeps.

Coronavirus in NYC Causes Uncertainty

For millions of Italians, and millions more around the globe, the confines of home became the new reality in fighting the spread of the coronavirus. Italian photojournalist Camila Ferrari offered a visual diary of intimacy within isolation.

Photos: Confined to Home in Milan

Around the world, we saw doctors, nurses and medical staff on the front lines in the battle against the COVID-19 pandemic.

Photos: Hospitals Fighting Coronavirus

As the pandemic raged, global citizens found new ways of socializing and supporting each other. From dance classes to church services, the screen took center stage.

Photos: Staying Connected in Quarantine

In April of 2020, photographer John Moore captured behind the scene moments of medical workers providing emergency services to patients with COVID-19 symptoms in New York City and surrounding areas.

Photos: Paramedics on the Front Lines

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately impacted undocumented communities that often lack unemployment protections, health insurance and at times, fear deportation.

Photos: Migrants and the Coronavirus

Aerial views showed startlingly desolate landscapes and revealed the scale of the pandemic.

Photos: COVID-19 From Above

With devastating death tolls, COVID-19 altered the rituals of mourning loved ones.

Photos: Final Farewells

In recognition of May Day in 2020, these portraits celebrated essential workers around the globe.

Photos: Essential Workers of the World

In May 2020, of the 10 counties with the highest death rates per capita in America, half were in rural southwest Georgia, where there are no packed apartment buildings or subways. And where you could see ambulances rushing along country roads, just fields and farms in either direction, carrying COVID-19 patients to the nearest hospital, which for some is an hour away.

Photos: In Rural Georgia, Devastation

In January of 2021, as new variants of the virus emerged, Pfizer-BioNTech, Moderna and other vaccines led a historic global immunization rollout, offering hope.

Photos: COVID-19 Vaccinations

Join the Conversation

Tags: Coronavirus , public health , Photo Galleries , New York City , pandemic

Health News Bulletin

Stay informed on the latest news on health and COVID-19 from the editors at U.S. News & World Report.

Sign in to manage your newsletters »

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

You May Also Like

The 10 worst presidents.

U.S. News Staff Feb. 23, 2024

Cartoons on President Donald Trump

Feb. 1, 2017, at 1:24 p.m.

Photos: Obama Behind the Scenes

April 8, 2022

Photos: Who Supports Joe Biden?

March 11, 2020

Trump Gives Johnson Vote of Confidence

Aneeta Mathur-Ashton April 12, 2024

U.S.: Threat From Iran ‘Very Credible’

Cecelia Smith-Schoenwalder April 12, 2024

Inflation Up, Consumer Sentiment Steady

Tim Smart April 12, 2024

House GOP Hands Johnson a Win

A Watershed Moment for America

Lauren Camera April 12, 2024

The Politically Charged Issue of EVs

The hazards of 'heroism' in the time of COVID-19

How does it feel to be called a hero - and who is really being served? Image: REUTERS/Tom Brenner

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Robert Waldinger

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} COVID-19 is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

- The word "hero" has been used a great deal during the pandemic.

- But this label is not always helpful, and can have negative consequences.

- Here are some suggestions for how we might better acknowledge the courage shown by so many at this time.

When the world is under threat, we look for heroes. We point to women and men who face the dangers that all of us fear, and we tell their stories with pride and gratitude. Identifying heroes can rally us, inspire us, and bring us together at times when unity is desperately needed. Not surprisingly, we are now finding heroes in the time of COVID-19: we are praising healthcare workers, first responders, those who deliver our mail and bring us our food. But what is it like to be called a hero? And who is served when we call some people heroes and others not?

We looked back to another time of crisis – World War II – to a group of soldiers who faced the horrors of war in Europe and the Pacific. The Harvard Study of Adult Development has tracked the lives of hundreds of men from the time they were teenagers all the way into old age, and more than 250 of them served in World War II. When these men came home from the war, we asked them how their wartime experiences changed their view of life, and whether they felt that the world owed them something for their military service. Not a single person said that the world owed them anything for their service. And no one said that they felt like a hero. Most said they were just doing their jobs.

Have you read?

Migrants and mayors are the unsung heroes of covid-19. here's why, stories from the medical staff on the frontline in the united states, what's needed now to protect health workers: who covid-19 briefing.

Why this disconnect?

The “hero” often feels like an imposter. Heroism is an ideal that few of us can live up to. Consider, for example, the nurse caring for COVID-19 patients in the hospital who feels she is neglecting her children by not being at home. Or the man working in a food processing plant who must work to feed his family, but who would much rather stay at home where he feels safe.

Calling some people heroes leaves other people feeling unappreciated. A doctor who must stay at home to care for her demented husband makes a sacrifice that no one may notice. During World War II, many soldiers felt guilty about doing desk jobs far away from combat.

When I praise someone as a hero, it serves my needs, not the needs of the “hero”. Calling someone else a hero – a nurse, a politician, a factory worker – can make us feel better. In a time of uncertainty and danger, imagining that someone else has special powers lets us feel a bit less helpless and vulnerable. Many of us are desperate to find this kind of relief.

We all want to be seen and appreciated by others for who we are and what we are doing. During this time of crisis, people need to feel appreciated more than ever.

How can we express gratitude in a way that feels genuine? A good place to begin is by paying close attention. What exactly do we appreciate about someone’s behaviour? What are the actions that take courage? When we appreciate the fact that a grocery store clerk reports for work every day in the midst of a dangerous pandemic, we are naming and expressing gratitude for a specific action. When we thank the nurse who cannot hug her children because she works with COVID-19 patients, we are appreciating a sacrifice that is both simple and profound.

Valuing each other is exactly what we need to do in this time of crisis. Labels like “hero” have their uses, but history tells us that those in the spotlight often do not feel seen when we put them on a pedestal, and many who behave with courage are hidden from view. Noticing and naming our many courageous gifts to each other can be the most inspiring and unifying way to keep hope alive during dark times.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on COVID-19 .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Winding down COVAX – lessons learnt from delivering 2 billion COVID-19 vaccinations to lower-income countries

Charlotte Edmond

January 8, 2024

Here’s what to know about the new COVID-19 Pirola variant

October 11, 2023

How the cost of living crisis affects young people around the world

Douglas Broom

August 8, 2023

From smallpox to COVID: the medical inventions that have seen off infectious diseases over the past century

Andrea Willige

May 11, 2023

COVID-19 is no longer a global health emergency. Here's what it means

Simon Nicholas Williams

May 9, 2023

New research shows the significant health harms of the pandemic

Philip Clarke, Jack Pollard and Mara Violato

April 17, 2023

The Hero’s Journey in the Time of COVID

Why stories of a hero’s adventures may resonate during the current pandemic..

Posted August 30, 2020

In only seven months, we have watched the dissolution of our familiar world. The viral outbreak has fractured our social order and dismantled the scaffolding which has held our society intact. Institutions we have come to rely on for our well-being—health care, education , government itself—are altered in ways we couldn’t have predicted.

We wonder how our future will look. Some of us even wonder if we will be alive in the future. What will survive? Will there be restaurants? Movie theaters? Malls and sports arenas? Will our children have human teachers, or will tele-teaching and tele-medical visits become the norm? Social instability appears to be chronic and unfixable and our psyches are suffering greatly. How could we not be swept up by feelings of abandonment, worry, anger , fear , hopelessness, helplessness, disorientation and loss, or numbed out and grieving? If any of these feelings ring true for you, you’re not alone.

Where can we find strength and resilience when hardships proliferate and we need to accommodate even more change? One way is to turn inward to our heroic self who seeks our greatest potential and guides us toward authentic wholeness. Here’s how depth psychologist Carl Jung described this inner companion: “Inside each of us is another who we do not know who speaks to us in dreams and tells us how differently he sees us from how we see ourselves.”

These days most everyone knows about the hero’s journey, whether they are aware of it or not. Popular culture brims with stories structured around the hero’s journey, including some of our most popular fictional characters like Harry Potter or Atticus Finch. The film industry has notably co-opted the hero’s journey to plot movies like Star Wars , The Lion King , Frozen , and all the James Bond films.

Mythologist Joseph Campbell first wrote about the hero’s journey in 1949 in his book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces . Campbell compared myths from around the world, some dating back thousands of years, and found that many of them shared a common structure, which he called “the hero’s adventure.” On an outer level, Campbell noted a sequence of events each hero/heroine encountered and he outlined their stages: departure and separation in which the hero/heroine leaves their safe world; initiation and ordeal in which the hero faces obstacles and ordeals that test her wisdom and skills; and the return , in which, having successfully overcome hardships, the hero returns to where she started, changed by her experience. On an inner psychological level, the hero’s journey depicts a maturation process of discovering one’s potential and becoming one’s true self; it is a portrait of profound transformation.

Hard times spur us to embody our hero-self. As Campbell and others discovered, many classic fairytale motifs as well as myths begin with a statement of misfortune, then progress through challenge and struggle, and finish in triumph. These stories chart the call to a higher purpose that catapults the hero/heroine out of the ordinary world into the unknown where she is tasked with a series of tests and tribulations and ultimately secures a treasure or elixir for herself and the collective world.

The Brothers Grimms' version of “Little Brother and Little Sister” illustrates how the initiating journey starts with misfortune:

Little Brother took his little sister by the hand and said, “Since our mother died we have had no happiness ; our step-mother beats us every day, and if we come near her she kicks us away with her foot. Our meals are the hard crusts of bread that are left over; and the little dog under the table is better off, for she often throws it a nice bit. May Heaven pity us. If our mother only knew! Come, we will go forth together into the wide world.”

Likewise, “The Knapsack, the Hat, and the Horn” begins:

There were once three brothers who had fallen deeper and deeper into poverty, and at last their need was so great that they had to endure hunger, and had nothing to eat or drink. Then said they, “We cannot go on thus, we had better go into the world and seek our fortune.”

In both stories, bad luck leads to good fortune as it does in “The Six Swans”:

Once upon a time, a certain king was hunting in a great forest, and he chased a wild beast so eagerly that none of his attendants could follow him. When evening drew near he stopped and looked around him, and then he saw that he had lost his way. He sought a way out, but could find none. Then he perceived an aged woman with a head which nodded perpetually, who came towards him, but she was a witch ...

In each story, we hold our breath as the hero faces impossible odds that seem unsurmountable and deadly. We read on, hoping against hope that some unseen force or influence will save the day. As in fairytales, so in life, but the helpers that come to our aid are not good fairies or friendly animals, they are our own brilliant but latent resources, instincts stirred to assist us.

Like dreams, these tales and their variants express the universal experiences of our inner worlds. The life of the soul comes to us through story. When we dream or dream our way into a tale, we are being shown the archetypal images latent in our souls that are bound by neither time nor place. To be in touch with this deep personal resource allows us to be lifted from the familiar and every day to view our lives from a God’s-eye perspective—and to see that the wasteland of today may be only a stage in the renewal of a new world.

What images are currently emerging in your dreams that speak of inner fears and challenges? Do you feel yourself abandoned by our government and leaders? Do you see yourself as a child lost in a wood, or freezing to death on a snowy evening ignored by the happy celebrants who pass you by, as in Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Match Girl”? Do you feel unseen in a society that doesn’t seem to care? Do you dream you have an impossible task to complete and not enough time? Do you arrive too late to take the exam or your driver’s test? Have you missed the train, forgotten your suitcase, misplaced the ticket, or can’t start the car? Do you dial for help only to discover your phone battery is dead? These are dream images of difficult beginnings, the conflict, or misfortune that sets you on the path. Carl Jung summed up the mystery and importance of dreams when he wrote, “A dream is a product of nature, the patient has not made it, it is like a letter dropped from Heaven, something he knows nothing of.” (ETH Lecture V 23, Nov1934. Page 156.)

Did you have a favorite fairytale growing up? (Preferably not the Disney version, which has usually been altered quite a bit from the original.) If “Rapunzel” or “The Frog King” or “Jack and the Beanstalk” enraptured you then, reread the story and note what stands out for you. What emotions do you feel? Is there something in your life now that has a similar theme? Does a different fairytale capture your attention ? Ask yourself how this particular tale affects you now.

Many of us are now managing anxiety , depression , anger, and fear through psychological and spiritual support. Working consciously with a creative channel by dream journaling, reading, or writing your own fairytale, or simply thinking about the stages of the hero’s journey can complement more conventional ways of managing difficult feelings. They could even bring fresh insights and creative solutions and restore energy to our feelings of “battle fatigue.”

The more you honor and stay in contact with feelings and images that arrive unbidden and give them space, the more they will share their wisdom with you. This is what Jung discovered during his decades-long exploration of soul and psyche. “The privilege of a lifetime,” he writes, “is to become who you truly are.”

Dale M. Kushner, MFA , explores the intersection of creativity, healing, and spirituality in her writing: her poetry collection M ; novel, The Conditions of Love ; and essays, including in Jung’s Red Book for Our Time .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Support Group

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- 2024 election

- Solar eclipse

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

Artists, novelists, critics, and essayists are writing the first draft of history.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Read these 12 moving essays about life during coronavirus

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66606035/1207638131.jpg.0.jpg)

The world is grappling with an invisible, deadly enemy, trying to understand how to live with the threat posed by a virus . For some writers, the only way forward is to put pen to paper, trying to conceptualize and document what it feels like to continue living as countries are under lockdown and regular life seems to have ground to a halt.

So as the coronavirus pandemic has stretched around the world, it’s sparked a crop of diary entries and essays that describe how life has changed. Novelists, critics, artists, and journalists have put words to the feelings many are experiencing. The result is a first draft of how we’ll someday remember this time, filled with uncertainty and pain and fear as well as small moments of hope and humanity.

At the New York Review of Books, Ali Bhutto writes that in Karachi, Pakistan, the government-imposed curfew due to the virus is “eerily reminiscent of past military clampdowns”:

Beneath the quiet calm lies a sense that society has been unhinged and that the usual rules no longer apply. Small groups of pedestrians look on from the shadows, like an audience watching a spectacle slowly unfolding. People pause on street corners and in the shade of trees, under the watchful gaze of the paramilitary forces and the police.

His essay concludes with the sobering note that “in the minds of many, Covid-19 is just another life-threatening hazard in a city that stumbles from one crisis to another.”

Writing from Chattanooga, novelist Jamie Quatro documents the mixed ways her neighbors have been responding to the threat, and the frustration of conflicting direction, or no direction at all, from local, state, and federal leaders:

Whiplash, trying to keep up with who’s ordering what. We’re already experiencing enough chaos without this back-and-forth. Why didn’t the federal government issue a nationwide shelter-in-place at the get-go, the way other countries did? What happens when one state’s shelter-in-place ends, while others continue? Do states still under quarantine close their borders? We are still one nation, not fifty individual countries. Right?

Award-winning photojournalist Alessio Mamo, quarantined with his partner Marta in Sicily after she tested positive for the virus, accompanies his photographs in the Guardian of their confinement with a reflection on being confined :

The doctors asked me to take a second test, but again I tested negative. Perhaps I’m immune? The days dragged on in my apartment, in black and white, like my photos. Sometimes we tried to smile, imagining that I was asymptomatic, because I was the virus. Our smiles seemed to bring good news. My mother left hospital, but I won’t be able to see her for weeks. Marta started breathing well again, and so did I. I would have liked to photograph my country in the midst of this emergency, the battles that the doctors wage on the frontline, the hospitals pushed to their limits, Italy on its knees fighting an invisible enemy. That enemy, a day in March, knocked on my door instead.

In the New York Times Magazine, deputy editor Jessica Lustig writes with devastating clarity about her family’s life in Brooklyn while her husband battled the virus, weeks before most people began taking the threat seriously:

At the door of the clinic, we stand looking out at two older women chatting outside the doorway, oblivious. Do I wave them away? Call out that they should get far away, go home, wash their hands, stay inside? Instead we just stand there, awkwardly, until they move on. Only then do we step outside to begin the long three-block walk home. I point out the early magnolia, the forsythia. T says he is cold. The untrimmed hairs on his neck, under his beard, are white. The few people walking past us on the sidewalk don’t know that we are visitors from the future. A vision, a premonition, a walking visitation. This will be them: Either T, in the mask, or — if they’re lucky — me, tending to him.

Essayist Leslie Jamison writes in the New York Review of Books about being shut away alone in her New York City apartment with her 2-year-old daughter since she became sick:

The virus. Its sinewy, intimate name. What does it feel like in my body today? Shivering under blankets. A hot itch behind the eyes. Three sweatshirts in the middle of the day. My daughter trying to pull another blanket over my body with her tiny arms. An ache in the muscles that somehow makes it hard to lie still. This loss of taste has become a kind of sensory quarantine. It’s as if the quarantine keeps inching closer and closer to my insides. First I lost the touch of other bodies; then I lost the air; now I’ve lost the taste of bananas. Nothing about any of these losses is particularly unique. I’ve made a schedule so I won’t go insane with the toddler. Five days ago, I wrote Walk/Adventure! on it, next to a cut-out illustration of a tiger—as if we’d see tigers on our walks. It was good to keep possibility alive.

At Literary Hub, novelist Heidi Pitlor writes about the elastic nature of time during her family’s quarantine in Massachusetts:

During a shutdown, the things that mark our days—commuting to work, sending our kids to school, having a drink with friends—vanish and time takes on a flat, seamless quality. Without some self-imposed structure, it’s easy to feel a little untethered. A friend recently posted on Facebook: “For those who have lost track, today is Blursday the fortyteenth of Maprilay.” ... Giving shape to time is especially important now, when the future is so shapeless. We do not know whether the virus will continue to rage for weeks or months or, lord help us, on and off for years. We do not know when we will feel safe again. And so many of us, minus those who are gifted at compartmentalization or denial, remain largely captive to fear. We may stay this way if we do not create at least the illusion of movement in our lives, our long days spent with ourselves or partners or families.

Novelist Lauren Groff writes at the New York Review of Books about trying to escape the prison of her fears while sequestered at home in Gainesville, Florida:

Some people have imaginations sparked only by what they can see; I blame this blinkered empiricism for the parks overwhelmed with people, the bars, until a few nights ago, thickly thronged. My imagination is the opposite. I fear everything invisible to me. From the enclosure of my house, I am afraid of the suffering that isn’t present before me, the people running out of money and food or drowning in the fluid in their lungs, the deaths of health-care workers now growing ill while performing their duties. I fear the federal government, which the right wing has so—intentionally—weakened that not only is it insufficient to help its people, it is actively standing in help’s way. I fear we won’t sufficiently punish the right. I fear leaving the house and spreading the disease. I fear what this time of fear is doing to my children, their imaginations, and their souls.

At ArtForum , Berlin-based critic and writer Kristian Vistrup Madsen reflects on martinis, melancholia, and Finnish artist Jaakko Pallasvuo’s 2018 graphic novel Retreat , in which three young people exile themselves in the woods:

In melancholia, the shape of what is ending, and its temporality, is sprawling and incomprehensible. The ambivalence makes it hard to bear. The world of Retreat is rendered in lush pink and purple watercolors, which dissolve into wild and messy abstractions. In apocalypse, the divisions established in genesis bleed back out. My own Corona-retreat is similarly soft, color-field like, each day a blurred succession of quarantinis, YouTube–yoga, and televized press conferences. As restrictions mount, so does abstraction. For now, I’m still rooting for love to save the world.

At the Paris Review , Matt Levin writes about reading Virginia Woolf’s novel The Waves during quarantine:

A retreat, a quarantine, a sickness—they simultaneously distort and clarify, curtail and expand. It is an ideal state in which to read literature with a reputation for difficulty and inaccessibility, those hermetic books shorn of the handholds of conventional plot or characterization or description. A novel like Virginia Woolf’s The Waves is perfect for the state of interiority induced by quarantine—a story of three men and three women, meeting after the death of a mutual friend, told entirely in the overlapping internal monologues of the six, interspersed only with sections of pure, achingly beautiful descriptions of the natural world, a day’s procession and recession of light and waves. The novel is, in my mind’s eye, a perfectly spherical object. It is translucent and shimmering and infinitely fragile, prone to shatter at the slightest disturbance. It is not a book that can be read in snatches on the subway—it demands total absorption. Though it revels in a stark emotional nakedness, the book remains aloof, remote in its own deep self-absorption.

In an essay for the Financial Times, novelist Arundhati Roy writes with anger about Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s anemic response to the threat, but also offers a glimmer of hope for the future:

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

From Boston, Nora Caplan-Bricker writes in The Point about the strange contraction of space under quarantine, in which a friend in Beirut is as close as the one around the corner in the same city:

It’s a nice illusion—nice to feel like we’re in it together, even if my real world has shrunk to one person, my husband, who sits with his laptop in the other room. It’s nice in the same way as reading those essays that reframe social distancing as solidarity. “We must begin to see the negative space as clearly as the positive, to know what we don’t do is also brilliant and full of love,” the poet Anne Boyer wrote on March 10th, the day that Massachusetts declared a state of emergency. If you squint, you could almost make sense of this quarantine as an effort to flatten, along with the curve, the distinctions we make between our bonds with others. Right now, I care for my neighbor in the same way I demonstrate love for my mother: in all instances, I stay away. And in moments this month, I have loved strangers with an intensity that is new to me. On March 14th, the Saturday night after the end of life as we knew it, I went out with my dog and found the street silent: no lines for restaurants, no children on bicycles, no couples strolling with little cups of ice cream. It had taken the combined will of thousands of people to deliver such a sudden and complete emptiness. I felt so grateful, and so bereft.

And on his own website, musician and artist David Byrne writes about rediscovering the value of working for collective good , saying that “what is happening now is an opportunity to learn how to change our behavior”:

In emergencies, citizens can suddenly cooperate and collaborate. Change can happen. We’re going to need to work together as the effects of climate change ramp up. In order for capitalism to survive in any form, we will have to be a little more socialist. Here is an opportunity for us to see things differently — to see that we really are all connected — and adjust our behavior accordingly. Are we willing to do this? Is this moment an opportunity to see how truly interdependent we all are? To live in a world that is different and better than the one we live in now? We might be too far down the road to test every asymptomatic person, but a change in our mindsets, in how we view our neighbors, could lay the groundwork for the collective action we’ll need to deal with other global crises. The time to see how connected we all are is now.

The portrait these writers paint of a world under quarantine is multifaceted. Our worlds have contracted to the confines of our homes, and yet in some ways we’re more connected than ever to one another. We feel fear and boredom, anger and gratitude, frustration and strange peace. Uncertainty drives us to find metaphors and images that will let us wrap our minds around what is happening.

Yet there’s no single “what” that is happening. Everyone is contending with the pandemic and its effects from different places and in different ways. Reading others’ experiences — even the most frightening ones — can help alleviate the loneliness and dread, a little, and remind us that what we’re going through is both unique and shared by all.

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In Culture

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Iran’s retaliatory attack against Israel, briefly explained

Life is hard. Can philosophy help?

Don’t sneer at white rural voters — or delude yourself about their politics

You probably shouldn’t panic about measles — yet

Biden’s student loan forgiveness plan, explained

A hack nearly gained access to millions of computers. Here’s what we should learn from this.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

current events conversation

Students Describe Their Pandemic Experience in Six-Word Memoirs

Wake up, get on Zoom, repeat.

By The Learning Network

Illustration by Nicholas Konrad

This post is part of The Learning Network’s weekly Current Events Conversation feature, in which we publish a selection of notable student comments on our daily writing prompts .

How would you describe pandemic life … in just six words?

Inspired by “ The Pandemic in Six-Word Memoirs ,” an Opinion piece by Larry Smith, the creator of Six-Word Memoirs , we challenged students to capture their experiences over the last 19 months in their own six-word stories.

We asked them: What comes to mind when you think about the last year, or even the 19 months since quarantines first began? What small details of your life seem especially interesting, poignant, funny or relatable?

Teenagers rose to the occasion with pandemic memoirs that brought humor, introspection and deep feeling to this moment. While short, these miniature stories convey much bigger ideas about online school, being trapped inside, missing friends, the political landscape, the “longest two weeks ever,” personal growth and hope.

Thank you to all those who participated in this exercise this week, including teenagers from Layton, Utah ; Riverside University High School in Milwaukee ; and Pittsburgh .

Please note: Student comments have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

“Congratulations on graduating!” *closes Chromebook* — Jack, Hoggard High School

Dusty backpacks, my life on pause. — Charlotte, J.R. Masterman

I love sleeping. Not this much! — Reece, Hoggard High School

Don’t cough. It scares people now. — Vay, Utah

Day 582 of two-week masking. — Will, Illinois

Glazed donuts, glazed eyes, glazed life. — Cassidy, Hoggard High School

Google search: How to survive apocalypse? — La, NUAMES High School

Day three: I need more shows. — Terrell, J.R. Masterman

Sounds fun, but what about Covid? — Alexandra, J.R. Masterman

Sleep and procrastination: my closest friends. — Nicole, Cary High School

Technology. An escape, but not education. — Gwyneth, Kempner High School

Eyes open, but never really awake. — Kara, J.R. Masterman

Close with family, far from friends. — Shalom, Houston

48th time I’ve seen this video. — Jonathan, J.R. Masterman

every day is the same day — Hsamu, Milwaukee, Wis.

Wake up, get on Zoom, repeat. — Jack, GB

Together now, but still all alone. — Sophie, Union High School

netflix, missing assignments, doordash, sleep deprived — Joah, Glenbrook North

Productiveness overcomes bad feelings and thoughts. — Manar, Kempner High School

Sleeping, eating, strolling. Nothing to do. — Jasmine, Riverside University High School

Trapped inside, empty streets, empty me. — Klajdi, J.R. Masterman

Tired of being in my room. — Valeria, New Mexico

TikTok, YouTube, Netflix; mind goes numb. — Maya, NUAMES High School

I’m six feet away from normal. — Abbey, J.R. Masterman

Learned how to smile without smiling. — Gabriel, Northbrook

Watching history being made; it’s bad. — Payton, Illinois

Political polarity, ravaging ‘rona, deliberate deceit — Caden, Utah

“In this together,” says comfortable billionaire. — Mya, NUAMES High School

Covid danger zones: parks and schools. — Chris, Hoggard High School

Spent 10 minutes picking out mask. — Lillian, Hoggard High School

Birthday ruined, schedule ruined, trust ruined. — Garrison, J.R. Masterman

“Covid is a hoax,” they said. — Jackson, Layton, Utah

a long, harsh, challenging, roller coaster — Hyan, Atrisco Heritage Academy High School

if we could flick a wand — Zebo, J.R. Masterman

Quit old habits, to heal inward. — Da’Jah, City High Charter School

I caught Covid; I’m better now. — Micaela, J.R. Masterman

Clenched jaws underneath disposable masks. — Pragati, Farmington High School

Offline, online, offline … Present? Not really. — Celia, Cary High School

Lacking sleep, lacking emotion, lacking connection. — Lorenzo, TNCS, Richmond, Va.

Trapped in my head, no escape. — Claire, J.R. Masterman

Lonely, but content; I grew tremendously. — Haven, Kempner High School

everyday is yesterday, my new life — Christoper, J.R. Masterman

Empty town, empty wallet, empty mind. — Ed, Mass.

My home soon became a chrysalis. — Sofia, California

Physical seclusion resulted in lonesome ideation. — Darlene, Kempner High School

Fail my classes. Eat Doritos. Repeat. — Dylan, Hoggard High School

A different person emerged from quarantine. — Tracy, Kempner High School

Lost my mask, need another one. — Jonah, J.R. Masterman

Friends? No, just games and screens. — Michael, City High, Pittsburgh

The vaccine works, please get it. — Eoin, J.R. Masterman

Depressed. Stressed. What is coming next?! — Taisen, Pittsburgh

I need to see the world. — Vrishab, J.R. Masterman

Time for reflection, time to question. — Gabrielle, Connecticut

Loneliness, anxiety, fear. Oh look, hope. — Audrey, Miami Country Day School

Learn more about Current Events Conversation here and find all of our posts in this column .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- SAGE - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Me? A Hero? Gendered Work and Attributions of Heroism among Volunteers during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Braden leap.

Mississippi State University, USA

Kimberly Kelly

Marybeth c stalp.

University of Northern Iowa, USA

The gendered features of adults’ attributions of heroism to themselves and others has received substantially less scholarly attention than the gendered dynamics of media representations of (super)heroes. Utilizing 78 interviews and 569 self-administered questionnaires completed by adults in the United States who were voluntarily making personal protective equipment during the COVID-19 pandemic, we show how respondents effectively deployed popularized assessments of the relative value of gendered labour in the private and public spheres to shift attributions of heroism from themselves to others. Though media portrayals at the outset of the pandemic depicted these volunteers working in their homes as heroes, respondents insisted that the real heroes were those working in the public sphere. Even if media representations increasingly frame women as heroes, these results suggest that the long-standing associations between men and heroism will likely remain in place if feminized labour associated with the private sphere of households remains devalued.

Introduction

Heroes are especially important to communities and societies because they enhance the well-being of others and personify who and what are considered worthy of emulation ( Kinsella et al., 2015a ). Like ‘cultural constellations’ ( Dyson, 1996 ), those labelled heroes provide individuals with ‘moral beacons’ ( Porpora, 1996 : 210) for how they should look, act and relate to others. In western contexts, heroism is generally associated with voluntarily acting to benefit others despite the physical, emotional and/or social risks incurred by taking such actions ( Franco et al., 2018 ; Kinsella et al., 2015b ). In addition to prominent public figures, ordinary individuals are fully capable of being heroes ( Franco and Zimbardo, 2006 ). Heroism can entail dramatic, death-defying feats, yet heroism also regularly involves caring for others and generosity ( Becker and Eagly, 2004 ).

Heroism can also present drawbacks for individuals, communities and societies ( Frisk, 2019 ). Prominent associations between heroism, men and masculinities facilitate the reproduction of inequitable gender orders by justifying men’s power over supposedly weak and vulnerable women ( Cocca, 2016 ; Cree, 2020 ; Lorber, 2002 ). Although the gendered features of media representations of (super)heroes have received substantial scholarly attention, significant work remains to be done in examining the links between gender and heroism ( Frisk, 2019 ; Kinsella et al., 2015b ). Regarding attributions of heroism, Kinsella et al. (2017 : 9) provocatively ask, ‘Do women have to achieve more to be recognized as heroes?’

We answer this question with an emphatic yes, but with a twist. We argue that women and men must achieve more to be recognized as heroes if their heroism is based on feminized labour associated with the private sphere of households. The ideology of separate spheres cleaves space into two distinct categories differentially associated with women and men. The private sphere of homes, care work and unpaid labour is associated with women and femininities. The public sphere of businesses, politics and paid labour is associated with men and masculinities. Following its initial development in the 19th century, how the spheres interface in practice has regularly been reorganized in response to shifting political-economic conditions and policies ( Hochschild and Machung, 1989 ; Laslett and Brenner, 1989 ). Although women increasingly entered the public sphere in the United States following the passage of civil rights legislation in the 1960s, the ideology of separate spheres is still centrally important to how gendered labour is accomplished and understood in both spheres. Paid work in the public sphere is still strongly associated with men and masculinities, for example, but women in the United States complete more unpaid labour on behalf of volunteer organizations outside their households at least in part because this unpaid work is associated with caring dispositions and skillsets commonly linked to women and feminized labour in the private sphere ( Gerstel, 2000 ; Leap, 2019 ).

By analysing 78 semi-structured interviews and 569 self-administered questionnaires completed by those who voluntarily made personal protective equipment (PPE) at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, we show how individuals who were labelled heroes at the outset of the pandemic shifted attributions of heroism from themselves to others by repeatedly drawing on the ideology of separate spheres. Although our respondents, whom we refer to as ‘makers’, were voluntarily subjecting themselves to a range of risks by producing and distributing PPE to help others during the pandemic, they overwhelmingly rejected the idea that they were heroes even though they were being lauded as such in the news media (e.g. Congresswoman Abigail Spanberger, 2020 ; Heloise, 2020 ). Drawing on understandings of heroism that associate it with masculinized work in the public sphere ( Featherstone, 1992 ), makers generally insisted there was nothing heroic about the sewing and 3D printing they were doing in their homes to protect others from a deadly virus. They emphasized that the hero label should be reserved for businesses and individuals working in the public sphere during the pandemic. Echoing popular assessments of gendered labour that have repeatedly elevated the value of masculinized work in the public sphere over feminized work in the private sphere ( Daniels, 1987 ; DeVault, 1991 ), men and women respondents lionized others’ work in the public sphere while deploying devalued assessments of work completed in their households to shift attributions of heroism from themselves to others.

Other scholars contend the lack of representations of women acting heroically in news and popular media is a key reason why heroism is more commonly attributed to men ( Becker and Eagly, 2004 ; Cocca, 2016 ; Rankin and Eagly, 2008 ). We argue that the link between men and heroism is also informed by gendered assessments of labour that obscure the importance and risks of feminized work in the private sphere. Even when the news media were portraying men and women who were voluntarily making and distributing PPE as heroes, those doing this work drew from devalued depictions of feminized work to insist they were not heroes. Disrupting the cultural links between men, masculinities and heroism, we show, can require more than just increased public attention to women acting heroically. It also requires acknowledging the complexities and significance of feminized work completed in the private sphere so that it can be recognized for what it often is – heroism that involves voluntarily placing one’s self at risk to enhance others’ well-being.

We utilize this analysis to synthesize and extend the literatures on pandemic heroism and the gendered contours of heroism. Although scholars have critically engaged with attributions of heroism at the outset of the pandemic ( Halberg et al., 2021 ; Kinsella et al., 2022 ), this scholarship has not considered either the gendered contours of heroism or heroes beyond the public sphere. Further, although there is an extensive collection of content analyses examining the gendered dynamics of representations of heroes, fewer studies focus on the gendered dynamics of attributing heroism to others. This is especially true in respect to adults’ assessments of heroism ( Kinsella et al., 2015b ). This deserves closer analysis because attributions of heroism are closely coupled with the reproduction, and potential subversion, of hegemonic gender orders that empower some men at the expense of women and other men ( Cocca, 2016 ; Cree, 2020 ; Lorber, 2002 ).

Gendered Representations of Heroes and Gendered Inequalities

Media representations of heroes inform how individuals and groups do gender by legitimating certain behaviours as appropriate for men or women ( Coyne et al., 2014 ; Pennell and Behm-Morawitz, 2015 ). Representations of heroes have long provided powerful symbolic models against which actual men and women were judged as worthy of status and respect ( Connell, 1995 ; Cree, 2020 ). Although individuals can challenge the gendered dynamics of such representations ( Connell and Messerschmidt, 2005 ; Dallacqua and Low, 2021 ), others often still hold them accountable to expectations legitimated by these representations ( Marsh, 2000 ; Moeller, 2011 ). By engaging with these representations, individuals and groups situate themselves within inequitable gender orders ( Cocca, 2016 ; Dyson, 1996 ).

Although evidence suggests women have been more likely to act heroically in some situations ( Becker and Eagly, 2004 ), across a range of national contexts heroism is generally associated with men and masculinities ( Cocca, 2016 ; Danilova and Kolpinskaya, 2020 ; Lorber, 2002 ). Even the fictional worlds of superheroes, which provide opportunities to celebrate ‘ultimate androgyny’ ( Taylor, 2007 : 346), regularly feature powerful men rescuing vulnerable damsels in distress ( Burch and Johnsen, 2020 ; Scott, 2013 ). Female characters such as Wonder Woman provide exceptions to this trend, but they can still facilitate the reproduction of a hegemonic gender order because these heroic women are often dependent on men to validate their (hetero)sexual desirability and vanquish evil ( Avery-Natale, 2013 ; Cocca, 2016 ; Gilpatric, 2010 ; Magoulik, 2006 ). Consequently, such depictions can promote a patriarchal gender order closely linked to heterosexuality even though female heroes may kick some ass ( Cocca, 2016 ; Magoulik, 2006 ).

Representations of heroes also legitimate hierarchies among men and masculinities. Particular men are represented as heroes worthy of status because of their unique bravery, selflessness or abilities to utilize exceptional skills – often to protect women from men portrayed as exceptionally evil ( Cree, 2020 ; Kelly, 2012 ; Lorber, 2002 ). Even when not fighting bad guys, depictions of heroic men equate certain practices and body types with status and respectability ( Avery-Natale, 2013 ; Burch and Johnsen, 2020 ). In short, representations of heroes have regularly provided exemplary hegemonic masculinities that justify hierarchal gender relations between, and among, men and women ( Connell, 1995 ; Connell and Messerschmidt, 2005 ).

Gendered Perceptions of Heroes and Work

Although Porpora (1996) encouraged greater attention to adults’ attributions of heroism over two decades ago, studies examining individuals’ assessments of heroism have continued to focus on children and adolescents ( Estrada et al., 2015 ; Gash and Bajd, 2005 ; Holub et al., 2008 ). This is especially true in respect to analyses of the gendered features of hero attribution ( Danilova and Kolpinskaya, 2020 ; Kinsella et al., 2015b ). The limited studies focusing on adults diverge from and parallel studies on youth. In contrast to children, adults regularly indicate that they either do not have a hero or express reservations about identifying one ( Danilova and Kolpinskaya, 2020 ; Porpora, 1996 ; Yair et al., 2014 ). Nevertheless, laboratory studies show that popular depictions of heroes can influence adults’ understandings of themselves ( Pennell and Behm-Morawitz, 2015 ) and whether men or women can be heroic ( Rankin and Eagly, 2008 ). Echoing research on children, women are more likely than men to indicate that a woman is their hero ( Danilova and Kolpinskaya, 2020 ; Donoghue and Tranter, 2018 ; Rankin and Eagly, 2008 ). Nevertheless, overall, adults are more likely to identify men as heroes ( Danilova and Kolpinskaya, 2020 ; Donoghue and Tranter, 2018 ; Rankin and Eagly, 2008 ) or associate masculinized occupations such as ‘fireman’ with heroism ( Keczer et al., 2016 ). Men and women also sometimes associate different characteristics with heroism. Kinsella et al. (2015b) found that men were more likely than women to associate fearlessness, strength and saving others with heroism.

The gendered dynamics of hero attribution are related to whether and under what circumstances men and women are depicted as heroes in news and popular media ( Cocca, 2016 ). Becker and Eagly (2004) contend that heroism tends to be associated with masculinity because men are generally overrepresented in occupations in the public sphere whose death-defying rescues of people in distress receive consistent public recognition. Consequently, although women also routinely risk their well-being to help others, men are more strongly associated with heroism because men’s heroism gains more public recognition ( Becker and Eagly, 2004 ). A follow-up study by Rankin and Eagly (2008) supports this contention. Respondents were more likely to name men when asked to identify public figures who were heroes. However, when respondents were asked to identify heroes whom they personally knew, they were equally likely to identify men and women as heroes. When presented with a hypothetical rescue scenario, male and female respondents were equally likely to consider the fictional rescuer as heroic whether the rescuer were depicted as a man or woman ( Rankin and Eagly, 2008 ).

Becker and Eagly (2004) are right that men are overrepresented in occupations in the public sphere that are often lauded for heroic work, yet what is unclear is why work commonly associated with women in the private sphere is not considered heroic. Featherstone (1992) , for example, explicitly frames feminized work in households as the antithesis of heroism. Presumably, if attributions of heroism are contingent on recognizing that individuals’ actions benefitted others at the risk of harming their own well-being, work associated with the private sphere and femininities must be understood as either failing to benefit others or being risk free. Given that work associated with femininity and the private sphere is widely considered central to caring for others ( Laslett and Brenner, 1989 ), failing to consider this work heroic must be at least partially because it is not considered risky. Featherstone (1992 : 165) seemingly confirms this when he notes, ‘A basic contrast then, is that the heroic life is the sphere of danger, violence and the courting of risk whereas everyday life is the sphere of women, reproduction and care.’

Because the meanings associated with heroism, work and gender are social constructs, there is nothing inevitable about the conceptual links between heroism and work in the public sphere associated with men and masculinities. Seale’s (1995 , 2002 ) analyses of terminal illness are illustrative. Seale (1995 : 598) frames those who care for those dying from such illnesses as engaging in ‘specifically female heroics’. Further, newspaper coverage of cancer patients deployed gendered representations to frame women as heroes who were uniquely capable of utilizing emotional labour to effectively cope with devastating cancer diagnoses ( Seale, 2002 ). In both cases, Seale (1995 , 2002 ) portrays women as heroic due to their skilled utilization of caring and emotional labour commonly associated with the feminized private sphere.

Heroic Work during the COVID-19 Pandemic

Contrary to the general trend of focusing on the positive features of heroism ( Frisk, 2019 ), initial analyses of the COVID-19 pandemic have emphasized its potential drawbacks ( Kinsella et al., 2022 ). Emphasizing how heroic acts are undertaken within institutions that inequitably distribute risks and social obligations to address them ( Halberg et al., 2021 ), neoliberal policies and ideologies shaped the need for and portrayal of pandemic heroes ( Lohmeyer and Taylor, 2021 ). Labelling first responders, healthcare workers and other ‘essential’ personnel heroes positioned them as individually responsible for addressing problems exacerbated by decades of neoliberal policies ( Lohmeyer and Taylor, 2021 ). Meanwhile, the culpability of state institutions in helping to create conditions of suffering and any responsibility to effectively address them was minimized ( Cox, 2020 ; Halberg et al., 2021 ; Kinsella and Sumner, 2022 ; Lohmeyer and Taylor, 2021 ).

These portrayals also threatened to undermine the well-being of workers, as attributions of heroism made it more difficult to acknowledge workers’ needs for institutional supports, personal protective equipment, adequate pay and boundaries delineating how much they should sacrifice for others who often refused to participate in collective efforts to blunt transmission rates ( Cox, 2020 ). Analyses of frontline workers’ responses to public efforts to label them heroes are especially notable. Danish nurses reported that their experiences did not align with their understandings of heroism ( Halberg et al., 2021 ). They reported feeling overwhelmed, afraid and largely unprepared to work with COVID patients. Like a variety of frontline workers in the UK and Ireland ( Kinsella et al., 2022 ), Danish nurses also reported that being labelled a hero facilitated the expectation that they should endlessly sacrifice their own well-being on behalf of others.

Cox (2020) advocates ceasing labelling healthcare workers heroes, but others conclude that the label can still be useful for describing responses to the pandemic. Instead of portraying pandemic heroes as endless wells of sacrifice and bravery, it is necessary to acknowledge the social institutions that worked to facilitate the need for heroic acts, the negative consequences that can stem from sacrificing on behalf of others and how attributions of heroism can create unrealistic, potentially harmful expectations ( Halberg et al., 2021 ; Kinsella and Sumner, 2022 ). In short, heroes must be contextualized within institutions and considered fully human.

Methods and Data

This analysis utilizes 569 self-administered online questionnaires and 78 semi-structured phone interviews completed by US adults between July 2020 and January 2021. Both data generation techniques were approved by the authors’ institutional review boards. Inviting PPE makers to complete either a questionnaire or a telephone interview accommodated their time constraints and comfort with different technologies. There was a greater risk of social desirability bias during interviews because respondents were required to talk with a person. When asked whether they considered themselves heroes for making PPE, for example, interview respondents could have been more inclined to indicate that they did not because they wanted to avoid seeming narcissistic to the interviewer. However, responses across data generation techniques were consistent in content on this and all other questions utilized in this analysis. Consequently, we do not suspect social desirability bias had a more substantive impact on interview responses. On average, respondents completed questionnaires in 36 minutes and interviews in 53 minutes.

We used professional, personal and virtual networks to distribute flyers and invitations to participate in the study. Paralleling prior analyses of disaster responses ( Penta et al., 2020 ), social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and Reddit were especially useful for identifying potential participants because makers often used social media to organize PPE production. Because individuals who acquired raw materials and organized distribution networks were just as important as makers in getting PPE into the hands of users, they were included in the study.

As Table 1 illustrates, women, whites and relatively well-educated individuals are overrepresented in the sample as compared with the population of the United States. Other analyses that distributed online calls to participate during the pandemic reported similarly skewed samples ( Craig and Churchill, 2021 ; Friedman et al., 2021 ). The dynamics of making and volunteering in the USA could also help explain the sample composition. Sewing and 3D printing requires specialized equipment that presents classed barriers to participation ( Stalp, 2015 ), and the gendered and racialized dynamics of volunteerism in the USA have often encouraged white women to engage in volunteering at higher rates than other groups ( Pham, 2020 ). Although we purposefully contacted maker groups comprised primarily of people of colour to try to further diversify our sample, non-response bias could have also skewed the sample.

Demographic composition of interview and questionnaire respondents.

Notes : a Age was structured as an ordinal variable on questionnaires and an interval variable during interviews.

We cannot generalize our findings beyond our sample, but our dataset does have some notable strengths. The regional composition of questionnaire respondents is within +/– 5% of population estimates of the four Census Bureau regions of the USA ( US Census Bureau, 2022 ). Our data are also comprised solely of individuals’ first-hand assessments of their responses to the pandemic as it unfolded . As a result, it is an emotionally evocative dataset with detailed descriptions of makers’ efforts to survive a worsening disaster.

Following analyses of hero attribution that advocate utilizing open-ended questions to assess individuals’ attributions of heroism ( Danilova and Kolpinskaya, 2020 ; Donoghue and Tranter, 2018 ), we focus primarily on data generated through open questions. In addition to asking makers to detail the who, what, where, why and how of PPE production, we asked respondents whether they believed they or anyone else was a hero for their responses to the pandemic. Following Charmaz (2003) , we utilized an open, iterative approach to data analysis. We first read and re-read responses to identify themes respondents regularly invoked. After identifying and analysing key themes such as ‘risks incurred through making’ and ‘attributing heroism to PPE group organizers’ in greater detail, we determined that the ideology of separate spheres was centrally important to makers’ attributions of heroism because it effectively integrated the themes that emerged during the initial stages of data analysis.

Respondents are identified by their gender and region in the ensuing analysis. Each quote comes from a different maker. We begin by focusing on makers’ descriptions of fabricating PPE to highlight that their actions were heroic. We then illustrate how makers overwhelmingly rejected the suggestion that their work was heroic even though they incurred a multitude of risks to enhance others’ safety. Finally, we illustrate how makers deployed the gendered ideology of separate spheres to shift attributions of heroism from their work in the private sphere to other individuals and entities working in the public sphere.

Heroic PPE Production: Voluntarily Incurring Risks to Bolster Others’ Safety

Supplies of PPE were quickly exhausted in the USA in early 2020. After decades of neoliberal reforms had weakened public health infrastructure and encouraged for-profit production facilities to be moved out of the United States, neither state institutions nor private businesses could provide adequate PPE supplies ( Leap et al., 2022a , 2022b ). Individuals and civic organizations were encouraged to voluntarily produce and distribute substantial amounts of masks, face shields, hand sanitizer and other protective equipment. Across the USA, makers who answered this call were publicly lauded as heroes by news media and state officials. A June 2020 article in the Washington Post portrayed makers as heroes ( Heloise, 2020 ) and US House Representative Abigail Spanberger officially recognized makers as heroes ( Congresswoman Abigail Spanberger, 2020 ), for example.

Nevertheless, it may not be readily apparent that makers met the definition of heroes who were voluntarily risking their well-being to assist others. Pham (2020) , for example, echoes Featherstone (1992) when she contrasts the working conditions of low-paid garment workers with the supposedly safe working conditions enjoyed by volunteer PPE makers. She notes, ‘[Garment workers are] not making masks in the safety and comfort of their homes’ ( Pham, 2020 : 322). However, makers often exposed themselves to a multitude of physical, emotional, financial and social risks to get PPE to those who desperately needed it.

Repeatedly, makers indicated that they incurred aches, pains and repetitive motion injuries from spending hours on end producing PPE. One interviewee had even gone to the hospital after her legs became swollen following an especially intense mask production session. Makers also placed themselves at risk of infection as they sought out materials for production and then distributed finished PPE. In response to a questionnaire item that asked makers to detail any drawbacks associated with producing PPE, a Midwestern woman remarked, ‘Some people do not realize the time it takes and the risks I took with my own health when I stood in line for hours to get fabric. The assumptions that it was easy made me feel undervalued.’

Beyond physical risks, makers regularly indicated that it was emotionally overwhelming to know that others might die if they did not produce enough PPE. This caused considerable emotional turmoil for a man in the Western United States who was helping organize a network of makers that was producing tens of thousands of pieces of PPE. During his interview, he explained: