An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Psychology’s Status as a Science: Peculiarities and Intrinsic Challenges. Moving Beyond its Current Deadlock Towards Conceptual Integration

School of Human Sciences, University of Greenwich, Old Royal Naval College, Park Row, London, SE10 9LS UK

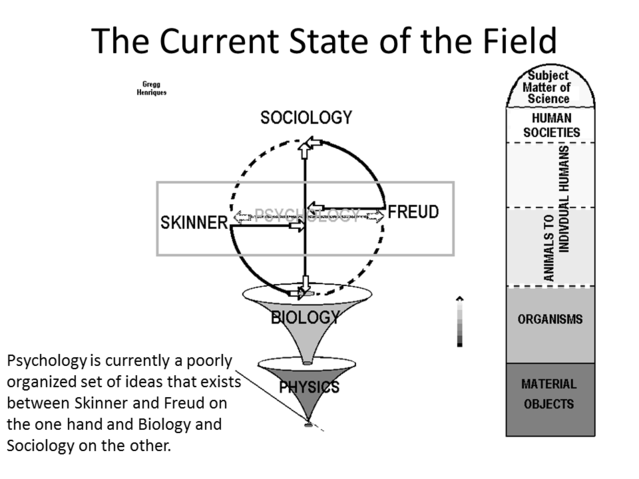

Psychology holds an exceptional position among the sciences. Yet even after 140 years as an independent discipline, psychology is still struggling with its most basic foundations. Its key phenomena, mind and behaviour, are poorly defined (and their definition instead often delegated to neuroscience or philosophy) while specific terms and constructs proliferate. A unified theoretical framework has not been developed and its categorisation as a ‘soft science’ ascribes to psychology a lower level of scientificity. The article traces these problems to the peculiarities of psychology’s study phenomena, their interrelations with and centrality to everyday knowledge and language (which may explain the proliferation and unclarity of terms and concepts), as well as to their complex relations with other study phenomena. It shows that adequate explorations of such diverse kinds of phenomena and their interrelations with the most elusive of all—immediate experience—inherently require a plurality of epistemologies, paradigms, theories, methodologies and methods that complement those developed for the natural sciences. Their systematic integration within just one discipline, made necessary by these phenomena’s joint emergence in the single individual as the basic unit of analysis, makes psychology in fact the hardest science of all. But Galtonian nomothetic methodology has turned much of today’s psychology into a science of populations rather than individuals, showing that blind adherence to natural-science principles has not advanced but impeded the development of psychology as a science. Finally, the article introduces paradigmatic frameworks that can provide solid foundations for conceptual integration and new developments.

Psychology’s Status as a Discipline

Psychology holds an exceptional position among the sciences—not least because it explores the very means by which any science is made, for it is humans who perceive, conceive, define, investigate, analyse and interpret the phenomena of the world. Scientists have managed to explore distant galaxies, quantum particles and the evolution of life over 4 billion years—phenomena inaccessible to the naked eye or long deceased. Yet, psychology is still struggling with its most basic foundations. The phenomena of our personal experience, directly accessible to everyone in each waking moment of life, remain challenging objects of research. Moreover, psychical phenomena are essential for all sciences (e.g., thinking). But why are we struggling to scientifically explore the means needed to first make any science? Given the successes in other fields, is this not a contradiction in itself?

This article outlines three key problems of psychology (poor definitions of study phenomena, lack of unified theoretical frameworks, and an allegedly lower level of scientificity) that are frequently discussed and at the centre of Zagaria, Andò and Zennaro’s ( 2020 ) review. These problems are then traced to peculiarities of psychology’s study phenomena and the conceptual and methodological challenges they entail. Finally, the article introduces paradigmatic frameworks that can provide solid foundations for conceptual integration and new developments.

Lack of Proper Terms and Definitions of Study Phenomena

Introductory text books are supposed to present the corner stones of a science’s established knowledge base. In psychology, however, textbooks present definitions of its key phenomena—mind (psyche) and behaviour—that are discordant, ambiguous, overlapping, circular and context-dependent, thus inconclusive (Zagaria et al. 2020 ). Tellingly, many popular text books define ‘mind’ exclusively as ‘brain activity’, thus turning psychology’s central object of research into one of neuroscience. What then is psychology as opposed to neuroscience? Some even regard the definition of mind as unimportant and leave it to philosophers, thus categorising it as a philosophical phenomenon and shifting it again out of psychology’s own realm. At the same time, mainstream psychologists often proudly distance themselves from philosophers (Alexandrova & Haybron, 2016 ), explicitly referring to the vital distinction between science and philosophy. Behaviour, as well, is commonly reduced to ill-defined ‘activities’, ‘actions’ and ‘doings’ and, confusingly, often even equated with mind (psyche), such as in concepts of ‘inner and outer behaviours’ (Uher 2016b ). All this leaves one wonder what psychology is actually about.

As if to compensate the unsatisfactory definitional and conceptual status of its key phenomena in general, psychology is plagued with a chaotic proliferation of terms and constructs for specific phenomena of mind and behaviour (Zagaria et al. 2020 ). This entails that different terms can denote the same concept (jangle-fallacies; Kelley 1927 ) and the same terms different concepts (jingle-fallacies; Thorndike 1903 ). Even more basically, many psychologists struggle to explain what their most frequent study phenomena—constructs—actually are (Slaney and Garcia 2015 ). These deficiencies and inconsistencies involve a deeply fragmented theoretical landscape.

Lack of Conceptual Integration Into Overarching Frameworks

Like no other science, psychology embraces an enormous diversity of established epistemologies, paradigms, theories, methodologies and methods. Is that a result of the discipline’s unparalleled complexity and the therefore necessary scientific pluralism (Fahrenberg 2013 ) or rather an outcome of mistaking this pluralism for the unrestrained proliferation of perspectives (Zagaria et al. 2020 )?

The lack of a unified theory in psychology is widely lamented. Many ‘integrative theories’ were proposed as overarching frameworks, yet without considering contradictory presuppositions underlying different theories. Such integrative systems merely provide important overviews of the essential plurality of research perspectives and methodologies needed in the field (Fahrenberg 2013 ; Uher 2015b ). Zagaria and colleagues ( 2020 ) suggested evolutionary psychology could provide the much-needed paradigmatic framework. This field, however, is among psychology’s youngest sub-disciplines and its most speculative ones because (unlike biological phenomena) psychical, behavioural and social phenomena leave no fossilised traces in themselves. Their possible ancestral forms can only be reconstructed indirectly from archaeological findings and investigations of today’s humans, making evolutionary explorations prone to speculations and biases (e.g., gender bias in interpretations of archaeological findings; Ginge 1996 ). Cross-species comparative psychology offers important correctives through empirical studies of today’s species with different cognitive, behavioural, social and ecological systems and different degrees of phylogenetic relatedness to humans. This enables comparisons and hypothesis testing not possible when studying only humans but still faces limitations given human ancestors’ unavailability for direct study (Uher 2020a ).

But most importantly, evolutionary psychology does not provide consistent terms and concepts either; its key constructs ‘psychological adaptations’ and ‘evolved psychological mechanisms’ are as vague, ambiguous and ill-defined as ‘mind’ and ‘behaviour’. Moreover, the strong research heuristic formulated in Tinbergen’s four questions on the causation, function, development and evolution of behaviour is not an achievement of evolutionary psychology but originates from theoretical biology, thus again from outside of psychology.

Psychology—a ‘Soft Science’ in Pre-scientific Stage?

The pronounced inconsistencies in psychology’s terminological, conceptual and theoretical landscape have been likened to the pre-scientific stage of emerging sciences (Zagaria et al. 2020 ). Psychology was therefore declared a ‘soft science’ that can never achieve the status of the ‘hard sciences’ (e.g., physics, chemistry). This categorisation implies the belief that some sciences have only minor capacities to accumulate secured knowledge and lower abilities to reach theoretical and methodological consensus (Fanelli and Glänzel 2013 ; Simonton 2015 ). In particular, soft sciences would have only limited abilities to apply ‘the scientific method’, the general set of principles involving systematic observation, experimentation and measurement as well as deduction and testing of hypotheses that guide scientific practice (Gauch 2015 ). The idea of the presumed lack of methodological rigor and exactitude of ‘soft sciences’ goes back to Kant ( 1798 / 2000 ) and is fuelled by recurrent crises of replication, generalisation, validity, and other criteria considered essential for all sciences.

But classifying sciences into ‘hard’ and ‘soft’, implying some would be more scientific than others, is ill-conceived and misses the point why there are different sciences at all. Crucially, the possibilities for implementing particular research practices are not a matter of scientific discipline or their ascribed level of scientificity but solely depend on the particular study phenomena and their properties (Uher 2019 ). For study phenomena that are highly context-dependent and continuously changing in themselves, such as those of mind, behaviour and society, old knowledge cannot have continuing relevance as this is the case for (e.g., non-living) phenomena and properties that are comparably invariant in themselves. Instead, accurate and valid investigations require that concepts, theories and methods must be continuously adapted as well (Uher 2020b ).

The classification of sciences by the degree to which they can implement ‘the scientific method’ as developed for the natural sciences is a reflection of the method-centrism that has taken hold of psychology over the last century, when the craft of statistical analysis became psychologists’ dominant activity (Lamiell 2019 ; Valsiner 2012 ). The development of ever more sophisticated tools for statistical analysis as well as of rating scales enabling the efficient generation of allegedly quantitative data for millions of individuals misled psychologists to adapt their study phenomena and research questions to their methods, rather than vice versa (Omi 2012 ; Toomela and Valsiner 2010 ; Uher 2013 ). But methods are just a means to an end. Sciences must be phenomenon-centred and problem-centred, and they must develop epistemologies, theories, methodologies and methods that are suited to explore these phenomena and the research problems in their field.

Psychology’s Study Phenomena and Intrinsic Challenges

Psychology’s exceptional position among the sciences and its key problems can be traced to its study phenomena’s peculiarities and the conceptual and methodological challenges they entail.

Experience: Elementary to All Empirical Sciences

Experience is elementary to all empirical sciences, which are experience-based by definition (from Greek empeiria meaning experience). The founder of psychology, Wilhelm Wundt, already highlighted that every concrete experience has always two aspects, the objective content given and individuals’ subjective apprehension of it—thus, the objects of experience in themselves and the subjects experiencing them. This entails two fundamental ways in which experience is treated in the sciences (Wundt 1896a ).

Natural sciences explore the objective contents mediated by experience that can be obtained by subtracting from the concrete experience the subjective aspects always contained in it. Hence, natural scientists consider the objects of experience in their properties as conceived independently of the subjects experiencing them, using the perspective of mediate experience (mittelbare Erfahrung; Wundt 1896a ). Therefore, natural scientists develop theories, approaches and technologies that help minimise the involvement of human perceptual and conceptual abilities in research processes and filter out their effects on research outcomes. This approach is facilitated by the peculiarities of natural-science study phenomena (of the non-living world, in particular), in which general laws, immutable relationships and natural constants can be identified that remain invariant across time and space and that can be measured and mathematically formalised (Uher 2020b ).

Psychologists, in turn, explore the experiencing subjects and their understanding and interpretation of their experiential contents and how this mediates their concrete experience of ‘reality’. This involves the perspective of immediate experience (unmittelbare Erfahrung), with immediate indicating absence of other phenomena mediating their perception (Wundt 1896a ). Immediate experience comprises connected processes, whereby every process has an objective content but is, at the same time, also a subjective process. Inner experience, Wundt highlighted, is not a special part of experience but rather constitutes the entirety of all immediate experience; thus, inner and outer experience do not constitute separate channels of information as often assumed (Uher 2016a ). That is, psychology deals with the entire experience in its immediate subjective reality. The inherent relation to the perceiving and experiencing subject— subject reference —is therefore a fundamental category in psychology. Subjects are feeling and thinking beings capable of intentional action who pursue purposes and values. This entails agency, volition, value orientation and teleology. As a consequence, Wundt highlighted, research on these phenomena can determine only law-like generalisations that allow for exceptions and singularities (Fahrenberg 2019 ). Given this, it is meaningless to use theories-to-laws ratios as indicators of scientificity (e.g., in Simonton 2015 ; Zagaria et al. 2020 ).

Constructs: Concepts in Science AND Everyday Psychology

The processual and transient nature of immediate experience (and many behaviours) imposes further challenges because, of processual entities, only a part exists at any moment (Whitehead 1929 ). Experiential phenomena can therefore be conceived only through generalisation and abstraction from their occurrences over time, leading to concepts, beliefs and knowledge about them , which are psychical phenomena in themselves as well but different from those they are about (reflected in the terms experien cing versus experien ce ; Erleben versus Erfahrung; Uher 2015b , 2016a ). Abstract concepts, because they are theoretically constructed, are called constructs (Kelly 1963 ). All humans implicitly develop constructs (through abduction, see below) to describe and explain regularities they observe in themselves and their world. They use constructs to anticipate the unknown future and to choose among alterative actions and responses (Kelly 1963 ; Valsiner 2012 ).

Constructs about experiencing, experience and behaviour form important parts of our everyday knowledge and language. This entails intricacies because psychologists cannot simply put this everyday psychology aside for doing their science, even more so as they are studying the phenomena that are at the centre of everyday knowledge and largely accessible only through (everyday) language. Therefore, psychologists cannot invent scientific terms and concepts that are completely unrelated to those of everyday psychology as natural scientists can do (Uher 2015b ). But this also entails that, to first delineate their study phenomena, psychologists need not elaborate scientific definitions because everyday psychology already provides some terms, implicit concepts and understanding—even if these are ambiguous, discordant, circular, overlapping, context-dependent and biased. This may explain the proliferation of terms and concepts and the lack of clear definitions of key phenomena in scientific psychology.

Constructs and language-based methods entail further challenges. The construal of constructs allowed scientists to turn abstract ideas into entities, thereby making them conceptually accessible to empirical study. But this entification misguides psychologists to overlook their constructed nature (Slaney and Garcia 2015 ) by ascribing to constructs an ontological status (e.g., ‘traits’ as psychophysical mechanisms; Uher 2013 ). Because explorations of many psychological study phenomena are intimately bound to language, psychologists must differentiate their study phenomena from the terms, concepts and methods used to explore them, as indicated by the terms psych ical versus psych ological (from Greek -λογία, -logia for body of knowledge)—differentiations not commonly made in the English-language publications dominating in contemporary psychology (Lewin 1936 ; Uher 2016a ).

Psychology’s Exceptional Position Among the Sciences and Philosophy

The concepts of mediate and immediate experience illuminate psychology’s special interrelations with the other sciences and philosophy. Wundt conceived the natural sciences (Naturwissenschaften; e.g., physics, physiology) as auxiliary to psychology and psychology, in turn, as supplementary to the natural sciences “in the sense that only together they are able to exhaust the empirical knowledge accessible to us“ (Fahrenberg 2019 ; Wundt 1896b , p. 102). By exploring the universal forms of immediate experience and the regularities of their connections, psychology is also the foundation of the intellectual sciences (Geisteswissenschaften, commonly (mis)translated as humanities; e.g., philology, linguistics, law), which explore the actions and effects emerging from humans’ immediate experiences (Fahrenberg 2019 ). Psychology also provides foundations for the cultural and social sciences (Kultur- und Sozialwissenschaften; e.g., sociology; anthropology), which explore the products and processes emerging from social and societal interactions among experiencing subjects who are thinking and intentional agents pursuing values, aims and purposes. Moreover, because psychology considers the subjective and the objective as the two fundamental conditions underlying theoretical reflection and practical action and seeks to determine their interrelations, Wundt regarded psychology also a preparatory empirical science for philosophy (especially epistemology and ethics; Fahrenberg 2019 ).

Psychology’s exceptional position at the intersection with diverse sciences and with philosophy is reflected in the extremely heterogeneous study phenomena explored in its diverse sub-disciplines, covering all areas of human life. Some examples are individuals’ sensations and perceptions of physical phenomena (e.g., psychophysics, environmental psychology, engineering psychology), biological and pathological phenomena associated with experience and behaviour (e.g., biopsychology, neuropsychology, clinical psychology), individuals’ experience and behaviour in relation to others and in society (e.g., social psychology, personality psychology, cultural psychology, psycholinguistics, economic psychology), as well as in different periods and domains of life (e.g., developmental psychology, educational psychology, occupational psychology). No other science explores such a diversity of study phenomena. Their exploration requires a plurality of epistemologies, methodologies and methods, which include experimental and technology-based investigations (e.g., neuro-imaging, electromyography, life-logging, video-analyses), interpretive and social-science investigations (e.g., of texts, narratives, multi-media) as well as investigations involving self-report and self-observation (e.g., interviews, questionnaires, guided introquestion).

All this shows that psychology cannot be a unitary science. Adequate explorations of so many different kinds of phenomena and their interrelations with the most elusive of all—immediate experience—inherently require a plurality of epistemologies, paradigms, theories, methodologies and methods that complement those developed for the natural sciences, which are needed as well. Their systematic integration within just one discipline, made necessary by these phenomena’s joint emergence in the single individual as the basic unit of analysis, makes psychology in fact the hardest science of all.

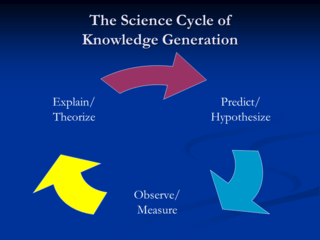

Idiographic and Nomothetic Strategies of Knowledge Generation

Immediate experience, given its subjective, processual, context-dependent, and thus ever-changing nature, is always unique and unprecedented. Exploring such particulars inherently requires idiographic strategies, in which local phenomena of single cases are modelled in their dynamic contexts to create generalised knowledge from them through abduction. In abduction, scientists infer from observations of surprising facts backwards to a possible theory that, if it were true, could explain the facts observed (Peirce 1901 ; CP 7.218). Abduction leads to the creation of new general knowledge, in which theory and data are circularly connected in an open-ended cycle, allowing to further generalise, extend and differentiate the new knowledge created. By generalising from what was once and at another time as well, idiographic approaches form the basis of nomothetic approaches, which are aimed at identifying generalities common to all particulars of a class and at deriving theories or laws to account for these generalities. This Wundtian approach to nomothetic research, because it is case-by-case based , allows to create generalised knowledge about psychical processes and functioning, thus building a bridge between the individual and theory development (Lamiell 2003 ; Robinson 2011 ; Salvatore and Valsiner 2010 ).

But beliefs in the superiority of natural-science principles misled many psychologists to interpret nomothetic strategies solely in terms of the Galtonian methodology, in which many cases are aggregated and statistically analysed on the sample-level . This limits research to group-level hypothesis testing and theory development to inductive generalisation, which are uninformative about single cases and cannot reveal what is, indeed, common to all (Lamiell 2003 ; Robinson 2011 ). This entails numerous fallacies, such as the widespread belief between-individual structures would be identical to and even reflect within-individual structures (Molenaar 2004 ; Uher 2015d ). Galtonian nomothetic methodology has turned much of today’s psychology into a science exploring populations rather than individuals. That is, blind adherence to natural-science principles has not advanced but, instead, substantially impeded the development of psychology as a science.

Moving Psychology Beyond its Current Conceptual Deadlock

Wundt’s opening of psychology’s first laboratory marked its official start as an independent science. Its dynamic developments over the last 140 years testify to psychology’s importance but also to the peculiarities of its study phenomena and the intricate challenges that these entail for scientific explorations. Yet, given its history, it seems unlikely that psychology can finally pull itself out of the swamps of conceptual vagueness and theoretical inconsistencies using just its own concepts and theories, in a feat similar to that of the legendary Baron Münchhausen. Psychology can, however, capitalise on its exceptional constellation of intersections with other sciences and philosophy that arises from its unique focus on the individual. Although challenging, this constitutes a rich source for perspective-taking and stimulation of new developments that can meaningfully complement and expand its own genuine achievements as shown in the paradigm outlined now.

The Transdisciplinary Philosophy-of-Science Paradigm for Research on Individuals (TPS-Paradigm)

The Transdisciplinary Philosophy-of-Science Paradigm for Research on Individuals ( TPS-Paradigm 2 ) is targeted toward making explicit and scrutinising the most basic assumptions that different disciplines make about research on individuals to help scientists critically reflect on; discuss and refine their theories and practices; and to derive ideas for new developments (therefore philosophy-of–science ). It comprises a system of interrelated philosophical, metatheoretical and methodological frameworks that coherently build upon each other (therefore paradigm ). In these frameworks, concepts from various lines of thought, both historical and more recent, and from different disciplines (e.g., psychology, life sciences, social sciences, physical sciences, metrology, philosophy of science) that are relevant for exploring research objects in (relation to) individuals were systematically integrated, refined and complemented by novel ones, thereby creating unitary frameworks that transcend disciplinary boundaries (therefore transdisciplinary ; Uher 2015a , b , 2018c ).

The Philosophical Framework: Presuppositions About Research on Individuals

The philosophical framework specifies three sets of presuppositions that are made in the TPS-Paradigm about the nature and properties of individuals and the phenomena studied in (relations to) them as well as about the notions by which knowledge about them can be gained.

- All science is done by humans and therefore inextricably entwined with and limited by human’s perceptual and conceptual abilities. This entails risks for particular fallacies of the human mind (e.g., oversimplifying complexity, Royce 1891 ; reifying linguistic abstractions, Whitehead 1929 ). Scientists researching individuals face particular challenges because they are individuals themselves, thus inseparable from their research objects. This entails risks for anthropocentric, ethnocentric and egocentric biases influencing metatheories and methodologies (Uher 2015b ). Concepts from social, cultural and theoretical psychology, sociology, and other fields (e.g., Gergen 2001 ; Valsiner 1998 ; Weber 1949 ) were used to open up meta-perspectives on research processes and help scientists reflect on their own presuppositions, ideologies and language that may (unintentionally) influence their research.

- Individuals are complex living organisms , which can be conceived as open (dissipative) and nested systems. On each hierarchical level, they function as organised wholes from which new properties emerge not predictable from their constituents and that can feed back to the constituents from which they emerge, causing complex patterns of upward and downward causation. With increasing levels of organisation, ever more complex systems emerge that are less rule-bound, highly adaptive and historically unique. Therefore, dissecting systems into elements cannot reveal the processes governing their functioning and development as a whole; assumptions on universal determinism and reductionism must be rejected. Relevant concepts from thermodynamics, physics of life, philosophy, theoretical biology, medicine, psychology, sociology and other fields (e.g., Capra 1997 ; Hartmann 1964 ; Koffka 1935 ; Morin 2008 ; Prigogine and Stengers 1997 ; Varela et al. 1974 ; von Bertalanffy 1937 ) about dialectics, complexity and nonlinear dynamic systems were used to elaborate their relevance for research on individuals.

- The concept of complementarity is applied to highlight that, by using different methods, ostensibly incompatible information can be obtained about properties of the same object of research that are nevertheless all equally essential for an exhaustive account of it and that may therefore be regarded as complementary to one another. Applications of this concept, originating from physics (wave-particle dilemma in research on the nature of light; Bohr 1937 ; Heisenberg 1927 ), to the body-mind problem emphasise the necessity for a methodical dualism to account for observations of two categorically different realities that require different frames of reference, approaches and methods (Brody and Oppenheim 1969 ; Fahrenberg 1979 , 2013 ; Walach 2013 ). Complementarity was applied to specify the peculiarities of psychical phenomena and to derive methodological concepts (Uher, 2016a ). It was also applied to develop solutions for the nomothetic-idiographic controversy in ‘personality’ research (Uher 2015d ).

These presuppositions underlie the metatheoretical and the methodological framework.

Metatheoretical Framework

The metatheoretical framework formalises a phenomenon’s accessibility to human perception under everyday conditions using three metatheoretical properties: internality-externality, temporal extension, and spatiality conceived complementarily as physical (spatial) and “non-physical” (without spatial properties). The particular constellations of their forms in given phenomena were used to metatheoretically define and differentiate from one another various kinds of phenomena studied in (relation to) individuals: morphology, physiology, behaviour, psyche, semiotic representations (e.g., language), artificial outer-appearance modifications (e.g., clothing) and contexts (e.g., situations; Uher 2015b ).

These metatheoretical concepts allowed to integrate and further develop established concepts from various fields to elaborate the peculiarities of the phenomena of the psyche 3 and their functional connections with other phenomena (e.g., one-sided psyche-externality gap; Uher 2013 ), to trace their ontogenetic development and to explore the fundamental imperceptibility of others’ psychical phenomena and its role in the development of agency, language, instructed learning, culture, social institutions and societies in human evolution (Uher 2015a ). The metatheoretical definition of behaviour 4 enabled clear differentiations from psyche and physiology, and clarified when the content-level of language in itself constitutes behaviour, revealing how language extends humans’ behavioural possibilities far beyond all non-language behaviours (Uher 2016b ). The metatheoretical definition of ‘personality’ as individual-specificity in all kinds of phenomena studied in individuals (see above) highlighted the unique constellation of probabilistic, differential and temporal patterns that merge together in this concept, the challenges this entails and the central role of language in the formation of ‘personality’ concepts. This also enabled novel approaches for conceptual integrations of the heterogeneous landscape of paradigms and theories in ‘personality’ research (Uher 2015b , c , d , 2018b ). The semiotic representations concept emphasised the composite nature of language, comprising psychical and physical phenomena, thus both internal and external phenomena. Failure to consider the triadic relations among meaning, signifier and referent inherent to any sign system as well as their inseparability from the individuals using them was shown to underly various conceptual fallacies, especially regarding data generation and measurement (Uher 2018a , 2019 ).

Methodological Framework

The metatheoretical framework is systematically linked to the methodological framework featuring three main areas.

- General concepts of phenomenon-methodology matching . The three metatheoretical properties were used to derive implications for research methodology, leading to new concepts that help to identify fallacies and mismatches (e.g., nunc-ipsum methods for transient phenomena, intro questive versus extro questive methods to remedy methodological problems in previous concepts of introspection; Uher 2016a , 2019 ).

- Methodological concepts for comparing individuals within and across situations, groups and species were developed (Uher 2015e ). Approaches for taxonomising individual differences in various kinds of phenomena in human populations and other species were systematised on the basis of their underlying rationales. Various novel approaches, especially behavioural ones, were developed to systematically test and complement the widely-used lexical models derived from everyday language (Uher 2015b , c , d , 2018b , c ).

- Theories and practices of data generation and measurement from psychology, social sciences and metrology, the science of measurement and foundational to the physical sciences, were scrutinised and compared. These transdisciplinary analyses identified two basic methodological principles of measurement underlying metrological concepts that are also applicable to psychological and social-science research (data generation traceability, numerical traceability; Uher 2020b ). Further analyses explored the involvement of human abilities in data generation across the empirical sciences (Uher 2019 ) and raters’ interpretation and use of standardised assessment scales (Uher 2018a ).

Empirical demonstrations of these developments and analyses in various empirical studies involving humans of different sociolinguistic backgrounds as well as several nonhuman primate species (e.g., Uher 2015e , 2018a ; Uher et al. 2013a , b ; Uher and Visalberghi 2016 ) show the feasibility of this line of research. Grounded in established concepts from various disciplines, it offers many possibilities for fruitful cross-scientific collaborations waiting to be explored in order to advance the fascinating science of individuals.

Author Contributions

I declare I am the sole creator of this research.

Funding Information

This research was conducted without funding.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

I declare to have no conflicting or competing interests.

2 http://researchonindividuals.org .

3 The psyche is defined as the “entirety of the phenomena of the immediate experiential reality both conscious and non-conscious of living organisms” (Uher 2015c , p. 431, derived from Wundt 1896a ).

4 Behaviours are defined as the “external changes or activities of living organisms that are functionally mediated by other external phenomena in the present moment” (Uher 2016b , p. 490).

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Alexandrova, A., & Haybron, D. M. (2016). Is construct validation valid? Philosophy of Science, 83(5), 1098–1109. 10.1086/687941

- Bohr N. Causality and complementarity. Philosophy of Science. 1937; 4 (3):289–298. doi: 10.1086/286465. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brody N, Oppenheim P. Application of Bohr’s principle of complementarity to the mind-body problem. Journal of Philosophy. 1969; 66 (4):97–113. doi: 10.2307/2024529. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Capra F. The web of life: A new synthesis of mind and matter. New York: Anchor Books; 1997. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fahrenberg, J. (1979). The complementarity principle in psychophysiological research and somatic medicine. Zeitschrift für Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie, 27 (2), 151–167. [ PubMed ]

- Fahrenberg J. Zur Kategorienlehre der Psychologie: Komplementaritätsprinzip; Perspektiven und Perspektiven-Wechsel. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fahrenberg, J. (2019). Wilhelm Wundt (1832 – 1920). Introduction, quotations, reception, commentaries, attempts at reconstruction . Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers.

- Fanelli D, Glänzel W. Bibliometric evidence for a hierarchy of the sciences. PLoS ONE. 2013; 8 (6):e66938. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066938. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gauch, H. G. J. (2015). Scientific method in practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gergen, K. J. (2001). Psychological science in a postmodern context. American Psychologist, 56(10) , 803–813. 10.1037/0003-066X.56.10.803. [ PubMed ]

- Ginge, B. (1996). Identifying gender in the archaeological record: Revising our stereotypes. Etruscan Studies, 3, Article 4.

- Hartmann N. Der Aufbau der realen Welt. Grundriss der allgemeinen Kategorienlehre (3. Aufl.) Berlin: Walter de Gruyter; 1964. [ Google Scholar ]

- Heisenberg, W. (1927). Über den anschaulichen Inhalt der quantentheoretischen Kinematik und Mechanik. Zeitschrift für Physik, 43 (3–4), 172–198. 10.1007/BF01397280.

- Kant, I. (1798/2000). Anthropologie in pragmatischer Hinsicht (Reinhard Brandt, ed.). Felix Meiner.

- Kelley TL. Interpretation of educational measurements. Yonkers: World; 1927. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kelly, G. (1963). A theory of personality: The psychology of personal constructs . W.W. Norton.

- Koffka K. Principles of Gestalt psychology. New York: Harcourt, Brace, & World; 1935. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lamiell, J. (2003). Beyond individual and group differences: Human individuality, scientific psychology, and William Stern’s critical personalism . Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications. 10.4135/9781452229317.

- Lamiell, J. (2019). Psychology’s misuse of statistics and persistent dismissal of its critics . Springer International. 10.1007/978-3-030-12131-0.

- Lewin K. Principles of topological psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1936. [ Google Scholar ]

- Molenaar PCM. A manifesto on psychology as idiographic science: Bringing the person back into scientific psychology, this time forever. Measurement: Interdisciplinary Research & Perspective. 2004; 2 (4):201–218. doi: 10.1207/s15366359mea0204_1. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morin E. On complexity. Cresskill: Hampton Press; 2008. [ Google Scholar ]

- Omi Y. Tension between the theoretical thinking and the empirical method: Is it an inevitable fate for psychology? Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science. 2012; 46 (1):118–127. doi: 10.1007/s12124-011-9185-4. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Peirce, C. S. (1901/1935). Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce (CP 7.218—1901, On the logic of drawing history from ancient documents especially from testimonies) . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Prigogine, I., & Stengers, I. (1997). The end of certainty: Time, chaos, and the new laws of nature . Free Press.

- Robinson OC. The idiographic/nomothetic dichotomy: Tracing historical origins of contemporary confusions. History & Philosophy of Psychology. 2011; 13 :32–39. [ Google Scholar ]

- Royce, J. (1891). The religious aspect of philosophy: A critique of the bases of conduct and of faith. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin.

- Salvatore S, Valsiner J. Between the general and the unique. Theory & Psychology. 2010; 20 :817–833. doi: 10.1177/0959354310381156. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Simonton DK. Psychology as a science within Comte’s hypothesized hierarchy: Empirical investigations and conceptual implications. Review of General Psychology. 2015; 19 (3):334–344. doi: 10.1037/gpr0000039. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Slaney KL, Garcia DA. Constructing psychological objects: The rhetoric of constructs. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology. 2015; 35 (4):244–259. doi: 10.1037/teo0000025. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thorndike EL. Notes on child study. 2. New York: Macmillan; 1903. [ Google Scholar ]

- Toomela, A., & Valsiner, J. (2010). Methodological thinking in psychology: 60 years gone astray? Information Age Publishing.

- Uher J. Personality psychology: Lexical approaches, assessment methods, and trait concepts reveal only half of the story-Why it is time for a paradigm shift. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science. 2013; 47 (1):1–55. doi: 10.1007/s12124-013-9230-6. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Uher, J. (2015a). Agency enabled by the psyche: Explorations using the Transdisciplinary Philosophy-of-Science Paradigm for Research on Individuals. In C. W. Gruber, M. G. Clark, S. H. Klempe, & J. Valsiner (Eds.), Constraints of agency: Explorations of theory in everyday life. Annals of Theoretical Psychology (Vol. 12) (pp. 177–228). 10.1007/978-3-319-10130-9_13.

- Uher J. Conceiving “personality”: Psychologist’s challenges and basic fundamentals of the Transdisciplinary Philosophy-of-Science Paradigm for Research on Individuals. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science. 2015; 49 (3):398–458. doi: 10.1007/s12124-014-9283-1. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Uher J. Developing “personality” taxonomies: Metatheoretical and methodological rationales underlying selection approaches, methods of data generation and reduction principles. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science. 2015; 49 (4):531–589. doi: 10.1007/s12124-014-9280-4. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Uher J. Interpreting “personality” taxonomies: Why previous models cannot capture individual-specific experiencing, behaviour, functioning and development. Major taxonomic tasks still lay ahead. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science. 2015; 49 (4):600–655. doi: 10.1007/s12124-014-9281-3. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Uher, J. (2015e). Comparing individuals within and across situations, groups and species: Metatheoretical and methodological foundations demonstrated in primate behaviour. In D. Emmans & A. Laihinen (Eds.), Comparative Neuropsychology and Brain Imaging (Vol. 2), Series Neuropsychology: An Interdisciplinary Approach (pp. 223–284). 10.13140/RG.2.1.3848.8169

- Uher, J. (2016a). Exploring the workings of the Psyche: Metatheoretical and methodological foundations. In J. Valsiner, G. Marsico, N. Chaudhary, T. Sato & V. Dazzani (Eds.), Psychology as the science of human being: The Yokohama Manifesto (pp. 299–324). 10.1007/978-3-319-21094-0_18.

- Uher J. What is behaviour? And (when) is language behaviour? A metatheoretical definition. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour. 2016; 46 (4):475–501. doi: 10.1111/jtsb.12104. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Uher J. Quantitative data from rating scales: An epistemological and methodological enquiry. Frontiers in Psychology. 2018; 9 :2599. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02599. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Uher J. Taxonomic models of individual differences: A guide to transdisciplinary approaches. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2018; 373 (1744):20170171. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2017.0171. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Uher, J. (2018c). The Transdisciplinary Philosophy-of-Science Paradigm for Research on Individuals: Foundations for the science of personality and individual differences. In V. Zeigler-Hill & T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Personality and Individual Differences: Volume I: The science of personality and individual differences (pp. 84–109). 10.4135/9781526451163.n4.

- Uher J. Data generation methods across the empirical sciences: differences in the study phenomena’s accessibility and the processes of data encoding. Quality & Quantity. International Journal of Methodology. 2019; 53 (1):221–246. doi: 10.1007/s11135-018-0744-3. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Uher J. Human uniqueness explored from the uniquely human perspective: Epistemological and methodological challenges. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour. 2020; 50 :20–24. doi: 10.1111/jtsb.12232. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Uher, J. (2020b). Measurement in metrology, psychology and social sciences: data generation traceability and numerical traceability as basic methodological principles applicable across sciences. Quality & Quantity. International Journal of Methodology, 54 , 975-1004. 10.1007/s11135-020-00970-2.

- Uher J, Addessi E, Visalberghi E. Contextualised behavioural measurements of personality differences obtained in behavioural tests and social observations in adult capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) Journal of Research in Personality. 2013; 47 (4):427–444. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2013.01.013. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Uher J, Visalberghi E. Observations versus assessments of personality: A five-method multi-species study reveals numerous biases in ratings and methodological limitations of standardised assessments. Journal of Research in Personality. 2016; 61 :61–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2016.02.003. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Uher J, Werner CS, Gosselt K. From observations of individual behaviour to social representations of personality: Developmental pathways, attribution biases, and limitations of questionnaire methods. Journal of Research in Personality. 2013; 47 (5):647–667. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2013.03.006. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Valsiner, J. (1998). The guided mind : A sociogenetic approach to personality. Harvard University Press.

- Valsiner J. A guided science: History of psychology in the mirror of its making. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers; 2012. [ Google Scholar ]

- Varela FG, Maturana HR, Uribe R. Autopoiesis: The organization of living systems, its characterization and a model. BioSystems. 1974; 5 (4):187–196. doi: 10.1016/0303-2647(74)90031-8. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- von Bertalanffy L. Das Gefüge des Lebens. Leipzig: Teubner; 1937. [ Google Scholar ]

- Walach, H. (2013). Psychologie: Wissenschaftstheorie, Philosophische Grundlagen und Geschichte (3. Aufl.) . Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

- Weber, M. (1949). On the methodology of the social sciences (E. Shils & H. Finch, Eds.). New York: Free Press.

- Whitehead AN. Process and reality. New York: Harper; 1929. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wundt, W. (1896a). Grundriss der Psychologie . Stuttgart: Körner. Retrieved from https://archive.org/ .

- Wundt W. Über die Definition der Psychologie. Philosophische Studien. 1896; 12 :9–66. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zagaria, A., Andò, A., & Zennaro, A. (2020). Psychology: A giant with feet of clay. Integrative Psychological & Behavioral Science. 10.1007/s12124-020-09524-5. [ PubMed ]

Is Psychology a Science?

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Psychology is a science because it employs systematic methods of observation, experimentation, and data analysis to understand and predict behavior and mental processes, grounded in empirical evidence and subjected to peer review.

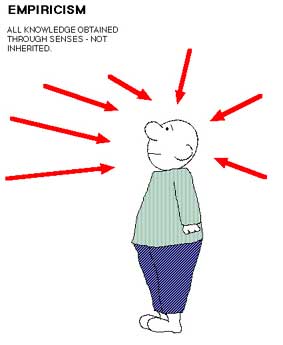

Science uses an empirical approach. Empiricism (founded by John Locke) states that the only source of knowledge is our senses – e.g., sight, hearing, etc.

In psychology, empiricism refers to the belief that knowledge is derived from observable, measurable experiences and evidence, rather than from intuition or speculation.

This was in contrast to the existing view that knowledge could be gained solely through the powers of reason and logical argument (known as rationalism). Thus, empiricism is the view that all knowledge is based on or may come from experience.

Through gaining knowledge through experience, the empirical approach quickly became scientific and greatly influenced the development of physics and chemistry in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The idea that knowledge should be gained through experience, i.e., empirically, turned into a method of inquiry that used careful observation and experiments to gather facts and evidence.

The nature of scientific inquiry may be thought of at two levels:

1. That to do with theory and the foundation of hypotheses. 2. And actual empirical methods of inquiry (i.e. experiments, observations)

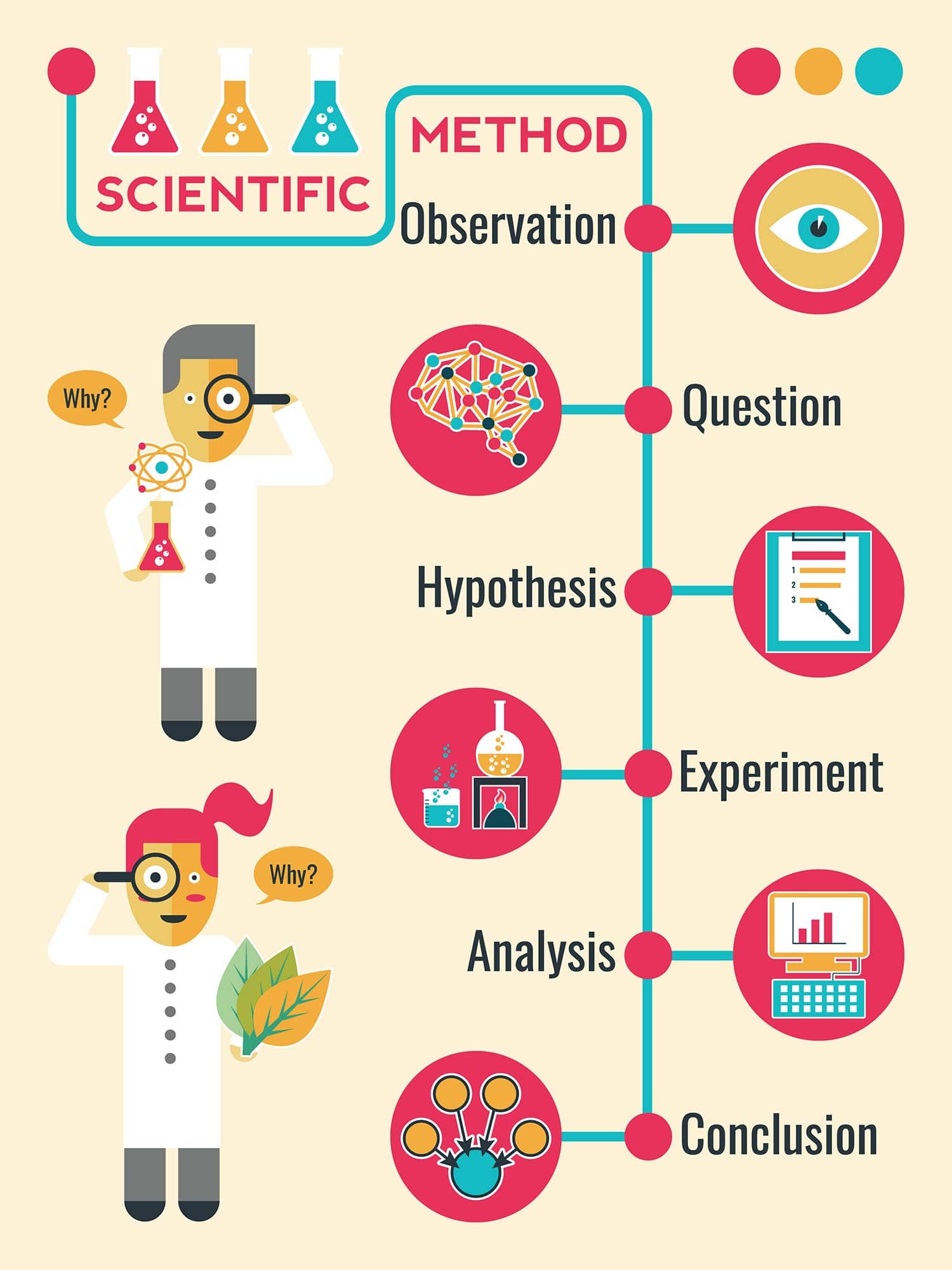

The prime empirical method of inquiry in science is the experiment.

The key features of the experiment are control over variables ( independent, dependent , and extraneous ), careful, objective measurement, and establishing cause and effect relationships.

Features of Science

Empirical evidence.

- Refers to data being collected through direct observation or experiment.

- Empirical evidence does not rely on argument or belief.

- Instead, experiments and observations are carried out carefully and reported in detail so that other investigators can repeat and attempt to verify the work.

Objectivity

- Researchers should remain value-free when studying; they should try to remain unbiased in their investigations. I.e., Researchers are not influenced by personal feelings and experiences.

- Objectivity means that all sources of bias are minimized and that personal or subjective ideas are eliminated. The pursuit of science implies that the facts will speak for themselves, even if they differ from what the investigator hoped.

- All extraneous variables need to be controlled to establish the cause (IV) and effect (DV).

Hypothesis testing

- E.g., a statement made at the beginning of an investigation that serves as a prediction and is derived from a theory. There are different types of hypotheses (null and alternative), which need to be stated in a form that can be tested (i.e., operationalized and unambiguous).

Replication

- This refers to whether a particular method and finding can be repeated with different/same people and/or on different occasions to see if the results are similar.

- If a dramatic discovery is reported, but other scientists cannot replicate it, it will not be accepted.

- If we get the same results repeatedly under the same conditions, we can be sure of their accuracy beyond a reasonable doubt.

- This gives us confidence that the results are reliable and can be used to build up a body of knowledge or a theory: which is vital in establishing a scientific theory.

Predictability

- We should aim to be able to predict future behavior from the findings of our research.

The Scientific Process

Before the twentieth century, science largely used induction principles – making discoveries about the world through accurate observations, and formulating theories based on the regularities observed.

Newton’s Laws are an example of this. He observed the behavior of physical objects (e.g., apples) and produced laws that made sense of what he observed.

The scientific process is now based on the hypothetico-deductive model proposed by Karl Popper (1935). Popper suggested that theories/laws about the world should come first, and these should be used to generate expectations/hypotheses, which observations and experiments can falsify.

As Popper pointed out, falsification is the only way to be certain: ‘No amount of observations of white swans can allow the conclusion that all swans are white, but the observation of a single black swan is sufficient to refute that conclusion.

Darwin’s theory of evolution is an example of this. He formulated a theory and tested its propositions by observing animals in nature. He specifically sought to collect data to prove his theory / disprove it.

Thomas Kuhn argued that science does not evolve gradually towards truth, science has a paradigm that remains constant before going through a paradigm shift when current theories can’t explain some phenomenon, and someone proposes a new theory. Science tends to go through these shifts; therefore, psychology is not a science as it has no agreed paradigm.

There are many conflicting approaches, and the subject matter of Psychology is so diverse; therefore, researchers in different fields have little in common.

Psychology is really a very new science, with most advances happening over the past 150 years or so. However, it can be traced back to ancient Greece, 400 – 500 years BC. The emphasis was a philosophical one, with great thinkers such as Socrates influencing Plato, who in turn influenced Aristotle.

Plato argued that there was a clear distinction between body and soul, believed very strongly in the influence of individual differences on behavior, and played a key role in developing the notion of “mental health,” believing that the mind needed stimulation from the arts to keep it alive.

Aristotle firmly believed that the body strongly affected the mind – you might say he was an early biopsychologist.

Psychology as a science took a “back seat” until Descartes (1596 – 1650) wrote in the 17th century. He believed strongly in the concept of consciousness, maintaining that it was that that separated us from animals.

He did, however, believe that our bodies could influence our consciousness and that the beginnings of these interactions were in the pineal gland – we know now that this is probably NOT the case!

From this influential work came other important philosophies about psychology, including the work by Spinoza (1632 – 1677) and Leibnitz (1646 – 1716). But there still was no single, scientific, unified psychology as a separate discipline (you could certainly argue that there still isn’t”t!).

When asked, “Who is the parent of psychology?” many people answer, “Freud.” Whether this is the case or not is open to debate, but if we were to ask who the parent of experimental psychology is, few would likely respond similarly. So, where did modern experimental psychology come from, and why?

Psychology took so long to emerge as a scientific discipline because it needed time to consolidate. Understanding behavior, thoughts, and feelings are not easy, which may explain why it was largely ignored between ancient Greek times and the 16th century.

But tired of years of speculation, theory, and argument, and bearing in mind Aristotle’s plea for scientific investigation to support the theory, psychology as a scientific discipline began to emerge in the late 1800s.

Wilheim Wundt developed the first psychology lab in 1879. Introspection was used, but systematically (i.e., methodologically). It was really a place from which to start thinking about how to employ scientific methods to investigate behavior.

The classic movement in psychology to adopt these strategies was the behaviorists, who were renowned for relying on controlled laboratory experiments and rejecting any unseen or subconscious forces as causes of behavior.

And later, cognitive psychologists adopted this rigorous (i.e., careful), scientific, lab-based approach.

Psychological Approaches

Psychoanalysis has great explanatory power and understanding of behavior. Still, it has been accused of only explaining behavior after the event, not predicting what will happen in advance, and being unfalsifiable.

Some have argued that psychoanalysis has approached the status more of a religion than a science. Still, it is not alone in being accused of being unfalsifiable (evolutionary theory has, too – why is anything the way it is? Because it has evolved that way!), and like theories that are difficult to refute – the possibility exists that it is actually right.

Kline (1984) argues that psychoanalytic theory can be broken down into testable hypotheses and tested scientifically. For example, Scodel (1957) postulated that orally dependent men would prefer larger breasts (a positive correlation) but, in fact, found the opposite (a negative correlation).

Although Freudian theory could be used to explain this finding (through reaction formation – the subject showing exactly the opposite of their unconscious impulses!), Kline has nevertheless pointed out that no significant correlation would have refuted the theory.

Behaviorism has parsimonious (i.e., economic / cost-cutting) theories of learning, using a few simple principles (reinforcement, behavior shaping, generalization, etc.) to explain a wide variety of behavior from language acquisition to moral development.

It advanced bold, precise, and refutable hypotheses (such as Thorndike’s law of effect ) and possessed a hard core of central assumptions such as determinism from the environment (it was only when this assumption faced overwhelming criticism by the cognitive and ethological theorists that the behaviorist paradigm/model was overthrown).

Behaviorists firmly believed in the scientific principles of determinism and orderliness. They thus came up with fairly consistent predictions about when an animal was likely to respond (although they admitted that perfect prediction for any individual was impossible).

The behaviorists used their predictions to control the behavior of both animals (pigeons trained to detect life jackets) and humans (behavioral therapies), and indeed Skinner , in his book Walden Two (1948), described a society controlled according to behaviorist principles.

Cognitive psychology – adopts a scientific approach to unobservable mental processes by advancing precise models and conducting experiments on behavior to confirm or refute them.

Full understanding, prediction, and control in psychology are probably unobtainable due to the huge complexity of environmental, mental, and biological influences upon even the simplest behavior (i.e., all extraneous variables cannot be controlled).

You will see, therefore, that there is no easy answer to the question, “is psychology a science?”. But many approaches of psychology do meet the accepted requirements of the scientific method, whilst others appear to be more doubtful in this respect.

Alternatives

However, some psychologists argue that psychology should not be a science. There are alternatives to empiricism, such as rational research, argument, and belief.

The humanistic approach (another alternative) values private, subjective conscious experience and argues for the rejection of science.

The humanistic approach argues that objective reality is less important than a person’s subjective perception and subjective understanding of the world. Because of this, Carl Rogers and Maslow placed little value on scientific psychology, especially using the scientific laboratory to investigate human and other animal behavior.

A person’s subjective experience of the world is an important and influential factor in their behavior. Only by seeing the world from the individual’s point of view can we really understand why they act the way they do. This is what the humanistic approach aims to do.

Humanism is a psychological perspective that emphasizes the study of the whole person. Humanistic psychologists look at human behavior not only through the eyes of the observer but through the eyes of the person doing the behavior. Humanistic psychologists believe that an individual’s behavior is connected to his inner feelings and self-image.

The humanistic approach in psychology deliberately steps away from a scientific viewpoint, rejecting determinism in favor of free will, aiming to arrive at a unique and in-depth understanding. The humanistic approach does not have an orderly set of theories (although it does have some core assumptions).

It is not interested in predicting and controlling people’s behavior – the individuals themselves are the only ones who can and should do that.

Miller (1969), in “Psychology as a Means of Promoting Human Welfare,” criticizes the controlling view of psychology, suggesting that understanding should be the main goal of the subject as a science since he asks who will do the controlling and whose interests will be served by it?

Humanistic psychologists rejected a rigorous scientific approach to psychology because they saw it as dehumanizing and unable to capture the richness of conscious experience.

In many ways, the rejection of scientific psychology in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s was a backlash to the dominance of the behaviorist approach in North American psychology.

Common Sense Views of Behavior

In certain ways, everyone is a psychologist. This does not mean that everyone has been formally trained to study and be trained in psychology.

People have common sense views of the world, of other people, and of themselves. These common-sense views may come from personal experience, from our upbringing as a child, and through culture, etc.

People have common-sense views about the causes of their own and other people’s behavior, personality characteristics they and others possess, what other people should do, how to bring up your children, and many more aspects of psychology.

Informal psychologists acquire common-sense knowledge in a rather subjective (i.e., unreliable) and anecdotal way. Common-sense views about people are rarely based on systematic (i.e., logical) evidence and are sometimes based on a single experience or observation.

Racial or religious prejudices may reflect what seems like common sense within a group of people. However, prejudicial beliefs rarely stand up to what is actually the case.

Common sense, then, is something that everybody uses in their day-to-day lives, guides decisions and influences how we interact with one another.

However, because it is not based on systematic evidence or derived from scientific inquiry, it may be misleading and lead to one group of people treating others unfairly and in a discriminatory way.

Limitations of Scientific Psychology

Despite having a scientific methodology worked out (we think), some further problems and arguments doubt psychology is ever a science.

Limitations may refer to the subject matter (e.g., overt behavior versus subjective, private experience), objectivity, generality, testability, ecological validity, ethical issues, and philosophical debates, etc.

Science assumes that there are laws of human behavior that apply to each person. Therefore, science takes both a deterministic and reductionist approach.

Science studies overt behavior because overt behavior is objectively observable and can be measured, allowing different psychologists to record behavior and agree on what has been observed. This means that evidence can be collected to test a theory about people.

Scientific laws are generalizable, but psychological explanations are often restricted to specific times and places. Because psychology studies (mostly) people, it studies (indirectly) the effects of social and cultural changes on behavior.

Psychology does not go on in a social vacuum. Behavior changes over time and in different situations. These factors, and individual differences, make research findings reliable for a limited time only.

Are traditional scientific methods appropriate for studying human behavior? When psychologists operationalize their IV, it is highly likely that this is reductionist, mechanistic, subjective, or just wrong.

Operationalizing variables refers to how you will define and measure a specific variable as it is used in your study. For example, a biopsychologist may operationalize stress as an increased heart rate. Still, it may be that in doing this, we are removed from the human experience of what we are studying. The same goes for causality.

Experiments are keen to establish that X causes Y, but taking this deterministic view means that we ignore extraneous variables and the fact that at a different time, in a different place, we probably would not be influenced by X. There are so many variables that influence human behavior that it is impossible to control them effectively. The issue of ecological validity ties in really nicely here.

Objectivity is impossible. It is a huge problem in psychology, as it involves humans studying humans, and it is very difficult to study people’s behavior in an unbiased fashion.

Moreover, in terms of a general philosophy of science, we find it hard to be objective because a theoretical standpoint influences us (Freud is a good example). The observer and the observed are members of the same species are this creates problems of reflectivity.

A behaviorist would never examine a phobia and think in terms of unconscious conflict as a cause, just like Freud would never explain it as a behavior acquired through operant conditioning.

This particular viewpoint that a scientist has is called a paradigm (Kuhn, 1970). Kuhn argues that most scientific disciplines have one predominant paradigm that the vast majority of scientists subscribe to.

Anything with several paradigms (e.g., models – theories) is a pre-science until it becomes more unified. With a myriad of paradigms within psychology, it is not the case that we have any universal laws of human behavior. Kuhn would most definitely argue that psychology is not a science.

Verification (i.e., proof) may be impossible. We can never truly prove a hypothesis; we may find results to support it until the end of time, but we will never be 100% confident that it is true.

It could be disproved at any moment. The main driving force behind this particular grumble is Karl Popper, the famous philosopher of science and advocator of falsificationism.

Take the famous Popperian example hypothesis: “All swans are white.” How do we know for sure that we will not see a black, green, or hot pink swan in the future? So even if there has never been a sighting of a non-white swan, we still haven’t really proven our hypothesis.

Popper argues that the best hypotheses are those which we can falsify – disprove. If we know something is not true, then we know something for sure.

Testability: much of the subject matter in psychology is unobservable (e.g., memory) and, therefore, cannot be accurately measured. The fact that there are so many variables that influence human behavior that it is impossible to control the variables effectively.

So, are we any closer to understanding a) what science is and b) if psychology is a science? Unlikely. There is no definitive philosophy of science and no flawless scientific methodology.

When people use the term “Scientific,” we all have a general schema of what they mean, but when we break it down in the way that we just have done, the picture is less certain. What is science? It depends on your philosophy. Is psychology a science? It depends on your definition. So – why bother, and how do we conclude all this?

Slife and Williams (1995) have tried to answer these two questions:

1) We must at least strive for scientific methods because we need a rigorous discipline. If we abandon our search for unified methods, we’ll lose a sense of what psychology is (if we knew it in the first place).

2) We need to keep trying to develop scientific methods that are suitable for studying human behavior – it may be that the methods adopted by the natural sciences are not appropriate for us.

Further Information

- Psychology as a Science (PDF)

The “Is Psychology a Science?” Debate

Reviewing the ways in which psychology is and is not a science..

Posted January 27, 2016 | Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

If one is a psychologist or even has a passing interest in the field, one has likely encountered the question about whether psychology is truly a science or not. The debate has been prominent since psychology’s inception in the second half of the 19th century, and is evident in comments like that by William James who referred to it as “that nasty little subject." Scholars of the field know this debate has continued on and off, right up through the present day. The debate flared in the blogosphere a couple of years ago, after an op-ed piece by a microbiologist in the LA Times declared definitively that psychology was not a science , followed by several pieces in Psychology Today and Scientific American declaring definitively that psychology is, in fact, a science. Just last month, a long time scholar of the field authored the paper, Why Psychology Cannot Be an Empirical Science , and once again the blogosphere was debating the issue .

So what is the right answer? Is psychology a science or not? The answer is that it is complicated and the reason is that both science and psychology are complex, multifaceted constructs. As such, binary, blanket “yes” or “no” answers to the question fail. The answer I offer is that yes, it is largely a science, but there are important ways that it fails to live up to this description. To get a handle on why this is the right answer, let’s start with the construct of science, because if we are going to talk about the ways in which psychology is or is not a science, we had better have an idea of what we mean by both of these confusing terms.

Defining Science and Its Key Elements

For clarity of communication, it is often a good idea to start with some basic definitions, so let’s start with some generally agreed-upon definitions of science from reputable organizations.

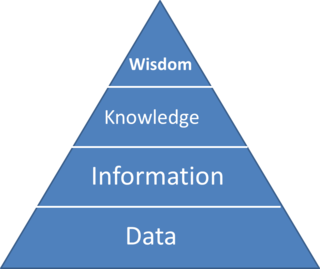

Science is the pursuit and application of knowledge and understanding of the natural and social world following a systematic methodology based on evidence .

Science refers to a system of acquiring knowledge [based on] observation and experimentation to describe and explain natural phenomena .

These are solid definitions, but we need to flesh them out a bit. I consider science to be made up of four elements: 1) the scientific mindset; 2) the scientific method; 3) the knowledge system of science and 4) science as a rhetorical label. The first three are fairly straightforward and the fourth is particularly relevant for this debate and debates like it (i.e., involving what does or does not get classified as a science). These elements are crucial to understanding the ways in which psychology is and is not a science.

The first point to make is that the scientific mindset involves a set of assumptions about causality and complexity and how an observer can know things about the way the world works (technically, this is called a scientific epistemology). When one is thinking scientifically, one assumes that the natural world is a closed system that follows cause-effect processes that are lawful and discoverable (i.e., that there is no supernatural interference). The scientific mindset also includes the following characteristics: emphasis on empirical evidence (i.e., data collection) to develop explanations; attitudes of openness to possible (natural) explanations and a skepticism about tradition, revelation and authority; an emphasis on objectivity (i.e., independent from the bias of the observer); an emphasis on logical coherence; and the belief that humans can build systems of knowledge that do, in fact, correspond to the way the world actually works.

Another defining feather of science is its reliance on systematic methods of data collection and critical analyses of the ideas of science. These are the methods that students learn about when they are introduced to “doing science," and include elements such as systematic observation, measurement and quantification, data gathering, hypothesis testing, controlled experimentation (where possible), and theory construction.

Although the scientific method is often touted as the sin qua non of science, it is not. Indeed, if science were solely a method, then it would not be all that valuable, a point that is sometimes lost on empiricists enamored with the scientific method. Thus, it is crucial to keep in mind that the scientific method is not an end unto itself, but rather is a means to an end. The ultimate desired product of the method is a cumulative body of knowledge that offers an approximate description of how the world works. In concrete terms, this refers to the body of peer-reviewed journals, textbooks, and academic courses and domains of inquiry. Ideally, the body of knowledge will have a center that is consensually agreed upon (e.g., the Periodic Table in chemistry) and peripheral domains that represent the edges of scientific inquiry and where one will find much debate, innovation , and differences of the opinion.

A final element that is particularly relevant in this context is that the term science has much rhetorical value in our culture. If something falls under the heading “science” then it is justified in receiving respect in the knowledge that it offers. Indeed, it is the “justifiability” argument that is at play in many of the debates about whether psychology warrants the title. For example, Alex Bezerow’s op-ed piece on Why Psychology Isn’t a Science explicitly hits on this issue:

The dismissive attitude scientists have toward psychologists isn't rooted in snobbery; it's rooted in intellectual frustration. It's rooted in the failure of psychologists to acknowledge that they don't have the same claim on secular truth that the hard sciences do. It's rooted in the tired exasperation that scientists feel when non-scientists try to pretend they are scientists.

Thus for Bezerow, (real) scientists dismiss psychologists because they are rightfully defending their turf. In contrast, defenders of psychology as science have told haters to “shut up already” about psychology not being a science because, although messy, psychology clearly has the “chops” to warrant the term .

Defining Psychology as a Science

Let’s turn from defining science to defining psychology. In what follows, I will be referring to psychology as it is presented in the academy, such as in Psych 101 textbooks. I mention this because it is different than the psychology that many people have in mind when they hear the term, which is the professional they might go see to talk with about their personal problems (note, the profession and practice of psychology is a whole separate issue).

There can be little doubt that academic psychology values and aspires to be a science, views itself as a science and, in many ways, looks and acts like a science. For starters, virtually every definition of psychology from every major group of psychologists define the field as a science. In addition, academic psychologists have long adopted the scientific mindset when it comes to their subject matter and have long employed scientific methods. Indeed, the official birth of psychology (Wundt’s lab) was characterized by virtue of the fact that it employed the methods of science (i.e., systematic observation, measurement, hypothesis testing, etc.) to understanding human conscious experience. And to this day, training in academic psychology is largely defined by training in the scientific method, measurement and data gathering, research design, and advanced statistical techniques, such as structural equation modeling, meta-analyses, and hierarchical linear regression . Individuals get their PhD in academic psychology by conducting systematic research and, if they want a career in the academy, they need to publish in peer reviewed journals and often need to have a program of (fundable) research. To see how much the identity of a scientist is emphasized, consider that a major psychological organization (APS) profiles its members, ending with the catch phrase “and I am a psychological scientist !” Indeed, mainstream academic psychologists are so focused on empirical data collection and research methods that I have accused them of being “methodological fundamentalists,” meaning that they often act as if the only questions that are worthy of attention in the field are reducible to empirical methods.

In sum, academic psychology looks like a scientific discipline and it has a home in the academy largely as a science, and psychologists very much behave like scientists and employ the scientific method to answer their questions. So, at this level, it seems like a pretty closed case. If something looks like a science and acts like a science, then it likely should be considered a science. But we are not quite done with the debate because the question remains: If all these things are true, then what is the problem? Why are there still so many skeptics? And why has psychology had such a long period of critics both inside and outside the discipline claiming that there is a “crisis” at the core of our field?

How Psychology Fails as a Science

From where I sit, the reasons for the skepticism are very clear. And it is NOT found in the methods nor the mindsets of psychologists, both of which are “scientific.” Nor is the primary problem found in the fact that what psychologists study can be very difficult to measure, nor is it because people are too complicated, nor because humans make choices, nor because it involves consciousness. Nor is it because psychology is a young science (note that this is a myth—there are many ‘real’ sciences that are much younger than psychology). These are all red herrings to the “Is psychology a science?” debate.

The reason many are rightfully skeptical about its status is found in the body of scientific knowledge—psychology has failed to produce a cumulative body of knowledge that has a clear conceptual core that is consensually agreed upon by mainstream psychological experts. The great scholar of the field, Paul Meehl, captured this perfectly when he proclaimed that the sad fact that in psychology:

theories rise and decline, come and go, more as a function of baffled boredom than anything else; and the enterprise shows a disturbing absence of that cumulative character that is so impressive in disciplines like astronomy, molecular biology and genetics .

Another great scholar of the field, Kenneth Gergen, likened acquiring psychological knowledge to building castles in the sand; the information gained from our methods might be impressive, but it is temporary, contextual, and socially dependent, and will be washed away when new cultural tides come in. Even mainstream icons, like Daniel Gilbert, readily acknowledge the cumulative knowledge problem. In this clip, he comments that one of psychology's big problems is that new paradigms simply “throw the babies out with the bathwater” and he wonders whether psychology as we know it will even be around in 10 or 15 years.