Table of Contents

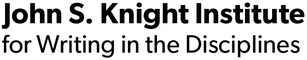

Collaboration, information literacy, writing process, coherence – how to achieve coherence in writing.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

Coherence refers to a style of writing where ideas, themes, and language connect logically, consistently, and clearly to guide the reader's understanding. By mastering coherence , alongside flow , inclusiveness , simplicity, and unity , you'll be well-equipped to craft professional or academic pieces that engage and inform effectively. Acquire the skills to instill coherence in your work and discern it in the writings of others.

What is Coherence?

Coherence in writing refers to the logical connections and consistency that hold a text together, making it understandable and meaningful to the reader. Writers create coherence in three ways:

- logical consistency

- conceptual consistency

- linguistic consistency.

What is Logical Consistency?

- For instance, if they argue, “If it rains, the ground gets wet,” and later state, “It’s raining but the ground isn’t wet,” without additional explanation, this represents a logical inconsistency.

What is Conceptual Consistency?

- For example, if you are writing an essay arguing that regular exercise has multiple benefits for mental health, each paragraph should introduce and discuss a different benefit of exercise, all contributing to your main argument. Including a paragraph discussing the nutritional value of various foods, while interesting, would break the conceptual consistency, as it doesn’t directly relate to the benefits of exercise for mental health.

What is Linguistic Consistency?

- For example, if a writer jumps erratically between different tenses or switches point of view without clear demarcation, the reader might find it hard to follow the narrative, leading to a lack of linguistic coherence.

Related Concepts: Flow ; Given to New Contract ; Grammar ; Organization ; Organizational Structures ; Organizational Patterns ; Sentence Errors

Why Does Coherence Matter?

Coherence is crucial in writing as it ensures that the text is understandable and that the ideas flow logically from one to the next. When writing is coherent, readers can easily follow the progression of ideas, making the content more engaging and easier to comprehend. Coherence connects the dots for the reader, linking concepts, arguments, and details in a clear, logical manner.

Without coherence, even the most interesting or groundbreaking ideas can become muddled and lose their impact. A coherent piece of writing keeps the reader’s attention, demonstrates the writer’s control over their subject matter, and can effectively persuade, inform, or entertain. Thus, coherence contributes significantly to the effectiveness of writing in achieving its intended purpose.

How Do Writers Create Coherence in Writing?

- Your thesis statement serves as the guiding star of your paper. It sets the direction and focus, ensuring all subsequent points relate back to this central idea.

- Acknowledge and address potential counterarguments to strengthen your position and add depth to your writing.

- Use the genres and organizational patterns appropriate for your rhetorical situation . A deductive structure (general to specific) is often effective, guiding the reader logically through your argument. Yet different disciplines may privilege more inductive approaches , such as law and philosophy.

- When following a given-to-new order, writers move from what the reader already knows to new information. In formal or persuasive contexts, writers are careful to vet new information for the reader following information literacy laws and conventions .

- Strategic repetition of crucial terms and your thesis helps your readers follow your main ideas and evidence for claims

- While repetition is useful, varying language with synonyms can prevent redundancy and keep the reader engaged.

- Parallelism in sentences can provide rhythm and clarity, making complex ideas easier to follow.

- Consistent use of pronouns avoids confusion and helps in maintaining a clear line of thought.

- Arrange your ideas in a sequence that naturally builds from one point to the next, ensuring each paragraph flows smoothly into the next .

- Signposting , or using phrases that indicate what’s coming next or what just happened, can help orient the reader within your argument.

- Don’t bother repeating your argument in your conclusion. Prioritize conciseness. Yet end with a call to action or appeal to kairos and ethos .

Recommended Resources

- Organization

- Organizational Patterns

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...

Information Literacy - Discerning Quality Information from Noise

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a...

Mindset refers to a person or community’s way of feeling, thinking, and acting about a topic. The mindsets you hold, consciously or subconsciously, shape how you feel, think, and act–and...

Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication

Learn about rhetoric and rhetorical practices (e.g., rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning, rhetorical situation, and rhetorical stance) so that you can strategically manage how you compose and subsequently produce a text...

Style, most simply, refers to how you say something as opposed to what you say. The style of your writing matters because audiences are unlikely to read your work or...

The Writing Process - Research on Composing

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about...

Writing Studies

Writing studies refers to an interdisciplinary community of scholars and researchers who study writing. Writing studies also refers to an academic, interdisciplinary discipline – a subject of study. Students in...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority – How to Establish Credibility in Speech & Writing

Achieving coherence

“A piece of writing is coherent when it elicits the response: ‘I follow you. I see what you mean.’ It is incoherent when it elicits the response: ‘I see what you're saying here, but what has it got to do with the topic at hand or with what you just told me above?’ ” - Johns, A.M

Transitions

Parallelism, challenge task, what is coherence.

Coherence in a piece of writing means that the reader can easily understand it. Coherence is about making everything flow smoothly. The reader can see that everything is logically arranged and connected, and relevance to the central focus of the essay is maintained throughout.

Repetition in a piece of writing does not always demonstrate cohesion. Study these sentences:

So, how does repetition as a cohesive device work?

When a pronoun is used, sometimes what the pronoun refers to (ie, the referent) is not always clear. Clarity is achieved by repeating a key noun or synonym . Repetition is a cohesive device used deliberately to improve coherence in a text.

In the following text, decide ifthe referent for the pronoun it is clear. Otherwise, replace it with the key noun English where clarity is needed.

Click here to view the revised text.

Suggested improvement

English has almost become an international language. Except for Chinese, more people speak it (clear reference; retain) than any other language. Spanish is the official language of more countries in the world, but more countries have English ( it is replaced with a key noun) as their official or unofficial second language. More than 70% of the world's mail is written in English ( it is replaced with a key noun). It (clear reference; retain) is the primary language on the Internet.

Sometimes, repetition of a key noun is preferred even when the reference is clear. In the following text, it is clear that it refers to the key noun gold , but when used throughout the text, the style becomes monotonous.

Improved text: Note where the key noun gold is repeated. The deliberate repetition creates interest and adds maturity to the writing style.

Gold , a precious metal, is prized for two important characteristics. First of all, gold has a lustrous beauty that is resistant to corrosion. Therefore, it is suitable for jewellery, coins and ornamental purposes. Gold never needs to be polished and will remain beautiful forever. For example, a Macedonian coin remains as untarnished today as the day it was made 23 centuries ago. Another important characteristic of gold is its usefulness to industry and science. For many years, it has been used in hundreds of industrial applications. The most recent use of gold is in astronauts’ suits. Astronauts wear gold -plated shields when they go outside spaceships in space. In conclusion, gold is treasured not only for its beauty but also its utility.

Pronoun + Repetition of key noun

Sometimes, greater cohesion can be achieved by using a pronoun followed by an appropriate key noun or synonym (a word with a similar meaning).

Transitions are like traffic signals. They guide the reader from one idea to the next. They signal a range of relationships between sentences, such as comparison, contrast, example and result. Click here for a more comprehensive list of Transitions (Logical Organisers) .

Test yourself: How well do you understand transitions?

Which of the three alternatives should follow the transition or logical organiser in capital letters to complete the second sentence?

Using transitions/logical organisers

Improve the coherence of the following paragraph by adding transitions in the blank spaces. Use the italicised hint in brackets to help you choose an apporpriate transition for each blank. If you need to, review the list of Transitions (Logical Organisers) before you start.

Using transitions

Choose the most appropriate transition from the options given to complete the article:

Overusing transitions

While the use of appropriate transitions can improve coherence (as the previous practice activity shows), it can also be counterproductive if transitions are overused. Use transitions carefully to enhance and clarify the logical connection between ideas in extended texts. Write a range of sentences and vary sentence openings.

Study the following examples:

Identifying cohesive devices

Table Of Contents

Introduction.

- What is coherence?

- What is cohesion?

- Lexical cohesion

- Grammatical cohesion

- Cohesive but not coherent texts

- 1. Start with an outline

- 2. Structure your essay

- 3. Structure your paragraphs

- 4. Relevance to the main topic

- 5. Stick to the purpose of the type of essay you”re-writing

- 6. Use cohesive devices and signposting phrases

- 7. Draft, revise, and edit

Please enable JavaScript

Coherent essays are identified by relevance to the central topic. They communicate a meaningful message to a specific audience and maintain pertinence to the main focus. In a coherent essay, the sentences and ideas flow smoothly and, as a result, the reader can follow the ideas developed without any issues.

To achieve coherence in an essay, writers use lexical and grammatical cohesive devices. Examples of these cohesive devices are repetition, synonymy, antonymy, meronymy, substitutions , and anaphoric or cataphoric relations between sentences. We will discuss these devices in more detail below.

This article will discuss how to write a coherent essay. We will be focusing on the five major points.

- We will start with definitions of coherence and cohesion.

- Then, we will give examples of how a text can achieve cohesion.

- We will see how a text can be cohesive but not coherent.

- The structure of a coherent essay will also be discussed.

- Finally, we will look in detail at ways to improve cohesion and write a coherent essay.

Before illustrating how to write coherent essays, let us start with the definitions of coherence and cohesion and list the ways we can achieve cohesion in a coherent text.

Definitions Cohesion And Coherence

In general, coherence and cohesion refer to how a text is structured so that the elements it is constituted of can stick together and contribute to a meaningful whole. In coherent essays, writers use grammatical and lexical cohesive techniques so that ideas can flow meaningfully and logically.

What Is Coherence?

Coherence refers to the quality of forming a unified consistent whole. We can describe a text as being coherent if it is semantically meaningful, that is if the ideas flow logically to produce an understandable entity.

If a text is coherent it is logically ordered and connected. It is clear, consistent, and understandable.

Coherence is related to the macro-level features of a text which enable it to have a sense as a whole.

What Is Cohesion?

Cohesion is commonly defined as the grammatical and lexical connections that tie a text together, contributing to its meaning (i.e. coherence.)

While coherence is related to the macro-level features of a text, cohesion is concerned with its micro-level – the words, the phrases, and the sentences and how they are connected to form a whole.

If the elements of a text are cohesive, they are united and work together or fit well together.

To summarize, coherence refers to how the ideas of the text flow logically and make a text semantically meaningful as a whole. Cohesion is what makes the elements (e.g. the words, phrases, clauses, and sentences) of a text stick together to form a whole.

How To Achieve Cohesion And Coherence In Essay Writing?

There are two types of cohesion: lexical and grammatical. Writers connect sentences and ideas in their essays using both lexical and grammatical cohesive devices.

Lexical Cohesion

We can achieve cohesion through lexical cohesion by using these techniques:

- Repetition.

Now let”s look at these in more detail.

Repeating words may contribute to cohesion. Repetition creates cohesive ties within the text.

- Birds are beautiful. I like birds.

You can use a word or phrase that means exactly or nearly the same as another word to achieve cohesion.

- Paul saw a snake under the mattress. The serpent was probably hiding there for a long time.

Antonymy refers to the use of a word of opposite meaning. This is often used to create links between the elements of a text.

- Old movies are boring, the new ones are much better.

This refers to the use of a word that denotes a subcategory of a more general class.

- I saw a cat . The animal was very hungry and looked ill.

Relating a superordinate term (i.e. animal) to a corresponding subordinate term (i.e. cat) may create more cohesiveness between sentences and clauses.

Meronymy is another way to achieve cohesion. It refers to the use of a word that denotes part of something but which is used to refer to the whole of it for instance faces can be used to refer to people as in “I see many faces here”. In the following example, hands refer to workers.

- More workers are needed. We need more hands to finish the work.

Grammatical Cohesion

Grammatical cohesion refers to the grammatical relations between text elements. This includes the use of:

- Cataphora .

- Substitutions.

- Conjunctions and transition words.

Let us illustrate the above devices with some examples.

Anaphora is when you use a word referring back to another word used earlier in a text or conversation.

- Jane was brilliant. She got the best score.

The pronoun “she” refers back to the proper noun “Jane”.

Cataphora is the opposite of anaphora. Cataphora refers to the use of a word or phrase that refers to or stands for a following word or phrase.

- Here he comes our hero. Please, welcome John .

The pronoun “he” refers back to the proper noun “John”.

Ellipsis refers to the omission from speech or writing of a word or words that are superfluous or able to be understood from contextual clues.

- Liz had some chocolate bars, and Nancy an ice cream.

In the above example, “had” in “Nancy an ice cream” is left because it can be understood (or presupposed) as it was already mentioned previously in the sentence.

Elliptic elements can be also understood from the context as in:

- A: Where are you going?

Substitutions

Substitutions refer to the use of a word to replace another word.

- A: Which T-shirt would you like?

- B: I would like the pink one .

Conjunctions transition words

Conjunctions and transition words are parts of speech that connect words, phrases, clauses, or sentences.

- Examples of conjunctions: but, or, and, although, in spite of, because,

- Examples of transition words: however, similarly, likewise, specifically, consequently, for this reason, in contrast to, accordingly, in essence, chiefly, finally.

Here are some examples:

- I called Tracy and John.

- He was tired but happy.

- She likes neither chocolates nor cookies.

- You can either finish the work or ask someone to do it for you.

- He went to bed after he had done his homework.

- Although she is very rich, she isn’t happy.

- I was brought up to be responsible. Similarly , I will try to teach my kids how to take responsibility for their actions.

Cohesive But Not Coherent Texts

Sometimes, a text may be cohesively connected, yet may still be incoherent.

Learners may wrongly think that simply linking sentences together will lead to a coherent text.

Here is an example of a text in which sentences are cohesively connected, yet the overall coherence is lacking:

The player threw the ball toward the goalkeeper. Balls are used in many sports. Most balls are spheres, but American football is an ellipsoid. Fortunately, the goalkeeper jumped to catch the ball. The crossbar in the soccer game is made of iron. The goalkeeper was standing there.

The sentences and phrases in the above text are decidedly cohesive but not coherent.

There is a use of:

- Repetition of: the ball, goalkeeper, the crossbar.

- Conjunctions and transition words: but, fortunately.

The use of the above cohesive devices does not result in a meaningful and unified whole. This is because the writer presents material that is unrelated to the topic. Why should a writer talk about what the crossbar is made of? And is talking about the form balls in sports relevant in this context? What is the central focus of the text?

A coherent essay has to be cohesively connected and logically expressive of the central topic.

How To Write A Coherent Essay?

1. start with an outline.

An outline is the general plan of your essays. It contains the ideas you will include in each paragraph and the sequence in which these ideas will be mentioned.

It is important to have an outline before starting to write. Spending a few minutes on the outline can be rewarding. An outline will organize your ideas and the end product can be much more coherent.

Here is how you can outline your writing so that you can produce a coherent essay:

- Start with the thesis statement – the sentence that summarizes the topic of your writing.

- Brainstorm the topic for a few minutes. Write down all the ideas related to the topic.

- Sift the ideas brainstormed in the previous step to identify only the ideas worth including in your essay.

- Organize ideas in a logical order so that your essay reflects the unified content that you want to communicate.

- Each idea has to be treated in a separate paragraph.

- Think of appropriate transitions between the different ideas.

- Under each idea/paragraph, write down enough details to support your idea.

After identifying and organizing your ideas into different paragraphs, they have to fit within the conventional structure of essays.

2. Structure Your Essay

It is also important to structure your essay so that you the reader can identify the organization of the different parts of your essay and how each paragraph leads to the next one.

Here is a structure of an essay

3. Structure Your Paragraphs

Paragraphs have to be well-organized. The structure of each paragraph should have:

- A topic sentence that is usually placed at the beginning,

- Supporting details that give further explanation of the topic sentence,

- And a concluding sentence that wraps up the content of the paragraph.

The supporting sentences in each paragraph must flow smoothly and logically to support the purpose of the topic sentence. Similarly, each paragraph has to serve the thesis statement, the main topic of the essay.

4. Relevance To The Main Topic

No matter how long the essay is, we should make sure that we stick to the topic we want to talk about. Coherence is about making everything flow smoothly to create unity. So, sentences and ideas must be relevant to the central thesis statement.

The writer has to maintain the flow of ideas to serve the main focus of the essay.

5. Stick To The Purpose Of The Type Of Essay You”Re-Writing

Essays must be clear and serve a purpose and direction. This means that the writer’s thoughts must not go astray in developing the purpose of the essay.

Essays are of different types and have different purposes. Accordingly, students have to stick to the main purpose of each genre of writing.

- An expository essay aims to inform, describe, or explain a topic, using essential facts to teach the reader about a topic.

- A descriptive essay intends to transmit a detailed description of a person, event, experience, or object. The aim is to make the reader perceive what is being described.

- A narrative essay attempts to tell a story that has a purpose. Writers use storytelling techniques to communicate an experience or an event.

- In argumentative essays, writers present an objective analysis of the different arguments about a topic and provide an opinion or a conclusion of positive or negative implications. The aim is to persuade the reader of your point.

6. Use Cohesive Devices And Signposting Phrases

Sentences should be connected using appropriate cohesive devices as discussed above:

Cohesive devices such as conjunctions and transition words are essential in providing clarity to your essay. But we can add another layer of clarity to guide the reader throughout the essay by using signpost signals.

What is signposting in writing?

Signposting refers to the use of phrases or words that guide readers to understand the direction of your essay. An essay should take the reader on a journey throughout the argumentation or discussion. In that journey, the paragraphs are milestones. Using signpost signals assists the reader in identifying where you want to guide them. Signposts serve to predict what will happen, remind readers of where they are at important stages along the process, and show the direction of your essay.

Essay signposting phrases

The following are some phrases you can use to signpost your writing:

It should be noted though that using cohesive devices or signposting language may not automatically lead to a coherent text. Some texts can be highly cohesive but remain incoherent. Appropriate cohesion and signposting are essential to coherence but they are not enough. To be coherent, an essay has to follow, in addition to using appropriate cohesive devices, all the tips presented in this article.

7. Draft, Revise, And Edit

After preparing the ground for the essay, students produce their first draft. This is the first version of the essay. Other subsequent steps are required.

The next step is to revise the first draft to rearrange, add, or remove paragraphs, ideas, sentences, or words.

The questions that must be addressed are the following:

- Is the essay clear? Is it meaningful? Does it serve the thesis statement (the main topic)?

- Are there sufficient details to convey ideas?

- Are there any off-topic ideas that you have to do without?

- Have you included too much information? Does your writing stray off-topic?

- Do the ideas flow in a logical order?

- Have you used appropriate cohesive devices and transition words when needed?

Once the revision is done, it is high time for the editing stage. Editing involves proofreading and correcting mistakes in grammar and mechanics. Pay attention to:

- Verb tense.

- Subject-verb agreement.

- Sentence structure. Have you included a subject a verb and an object (if the verb is transitive.)

- Punctuation.

- Capitalization.

Coherent essays are identified by relevance to the thesis statement. The ideas and sentences of coherent essays flow smoothly. One can follow the ideas discussed without any problems. Lexical and grammatical cohesive devices are used to achieve coherence. However, these devices are not sufficient. To maintain relevance to the main focus of the text, there is a need for a whole process of collecting ideas, outlining, reviewing, and editing to create a coherent whole.

More writing lessons here .

Quick Links

Awesome links you may like.

What are idioms? And how can idioms help you become a fluent speaker? Discover a list of the most widely used idiomatic expressions!

Phrasal verbs are generally used in spoken English and informal texts. Check out our list of hundreds of phrasal verbs classified in alphabetical order.

Do you want to provide emphasis, freshness of expression, or clarity to your writing? Check out this list of figures of speech!

Do you need to learn the irregular verbs in English? Here is a list of irregular verbs with definitions and examples!

Free English Grammar Lessons and Exercises

Study pages.

- Phrasal verbs

- Figures of speech

- Study Skills

- Global tests

- Business English

- Dictionaries

- Studying in the USA

- Visit the world

- Shared resources

- Teaching materials

Latest Blog Posts

Learn english the fun way, efl and esl community.

Subscribe and get the latest news and useful tips, advice and best offer.

Pasco-Hernando State College

- Unity and Coherence in Essays

- The Writing Process

- Paragraphs and Essays

- Proving the Thesis/Critical Thinking

- Appropriate Language

Test Yourself

- Essay Organization Quiz

- Sample Essay - Fairies

- Sample Essay - Modern Technology

Related Pages

- Proving the Thesis

Unity is the idea that all parts of the writing work to achieve the same goal: proving the thesis. Just as the content of a paragraph should focus on a topic sentence, the content of an essay must focus on the thesis. The introduction paragraph introduces the thesis, the body paragraphs each have a proof point (topic sentence) with content that proves the thesis, and the concluding paragraph sums up the proof and restates the thesis. Extraneous information in any part of the essay which is not related to the thesis is distracting and takes away from the strength of proving the thesis.

An essay must have coherence. The sentences must flow smoothly and logically from one to the next as they support the purpose of each paragraph in proving the thesis. .

Just as the last sentence in a paragraph must connect back to the topic sentence of the paragraph, the last paragraph of the essay should connect back to the thesis by reviewing the proof and restating the thesis.

Example of Essay with Problems of Unity and Coherence

Here is an example of a brief essay that includes a paragraph that does not support the thesis “Many people are changing their diets to be healthier.”

People are concerned about pesticides, steroids, and antibiotics in the food they eat. Many now shop for organic foods since they don’t have the pesticides used in conventionally grown food. Meat from chicken and cows that are not given steroids or antibiotics are gaining in popularity even though they are much more expensive. More and more, people are eliminating pesticides, steroids, and antibiotics from their diets.

Eating healthier also is beneficial to the environment since there are less pesticides poisoning the earth. Pesticides getting into the waterways is creating a problem with drinking water. Historically, safe drinking water has been a problem. It is believed the Ancient Egyptians drank beer since the water was not safe to drink. Brewing beer killed the harmful organisms and bacteria in the water from the Nile.

There is a growing concern about eating genetically modified foods, and people are opting for non-GMO diets. Some people say there are more allergic reactions and other health problems resulting from these foods. Others are concerned because there are no long-term studies which clearly show no adverse health effects such as cancers or other illnesses. Avoiding GMO food is another way people are eating healthier food.

See how just one paragraph can take away from the effectiveness of the essay in showing how people are changing to healthier food since the unity and coherence are affected. There is no longer unity among all the paragraphs. The thought pattern is disjointed and the essay loses its coherence.

Transitions and Logical Flow of Ideas

Transitions are words, groups of words, or sentences that connect one sentence to another or one paragraph to another.

They promote a logical flow from one idea to the next and overall unity and coherence.

While transitions are not needed in every sentence or at the end of every paragraph, they are missed when they are omitted since the flow of thoughts becomes disjointed or even confusing.

There are different types of transitions:

Time – before, after, during, in the meantime, nowadays

Space – over, around, under

Examples – for instance, one example is

Comparison – on the other hand, the opposing view

Consequence – as a result, subsequently

These are just a few examples. The idea is to paint a clear, logical connection between sentences and between paragraphs.

- Printer-friendly version

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

5 Coherent Paragraphs

When you think about it, there’s no contradiction in the advice of these two American writers. You should respond with genuine feeling and without inhibition to what stimulates you – in our case, a set of texts. But feeling isn’t enough. When Gustave Flaubert asked “Has a drinking song ever been written by a drunken man?” he meant a coherent song. Between “getting it down” and “handing it in” good writers show respect for their readers by organizing their material into recognizable patterns. An important benefit of this is that by distancing yourself from your ideas and putting them in order for your reader, you are forced to shape your own nebulous feelings into clear thoughts.

This brings us to the well-known (but apparently not well enough known) paragraph: the basic unit of composition. The traditional and still useful rule that a paragraph must have unity, coherence, and emphasis only means that it must make sense, that the sentences should fit together smoothly, and that not all the sentences function in the same way.

When you see that its purpose is to support your thesis by developing and connecting your ideas meaningfully, then paragraph structure should appeal to your common sense. As a point of emphasis a topic sentence – whether you choose to put it at the beginning, middle, or end – allows you to control your writing and guide your reader by expressing the main idea of the paragraph. Remember, you’re not writing a mystery novel. There will be relatively few instances in this type of essay when you’ll want to surprise your reader.

Must every paragraph have a topic sentence? Not necessarily: if the main idea is obvious, then a topic sentence may be omitted. But even if it is only implied by your paragraph, you and your reader should be able to state easily the main idea . Whether explicit or implicit, the topic sentence of each of your paragraphs should come out of your thesis statement and lead to your conclusion. Like the paragraph, the whole essay should have unity, coherence, and emphasis. Try this: next time you read an essay, underline only the topic sentences of each paragraph; then reread only what you’ve underlined. In many cases you’ll see that the underlined sentences make up a coherent paragraph all by themselves (this is an easy way to write an abstract, incidentally). That’s because most topic sentences are more specific than the thesis statement that generates them, but still more general than the supporting sentences in the paragraphs that illustrate them. Thus they are transitions between the writer’s promise to the reader and the keeping of that promise.

Examples: Opening Paragraphs

From a student essay discussing Kafka’s The Metamorphosis :

When Nietzsche declared that “God is dead,” he did so with an air of optimism. No longer could man be led about on the tight leash of religion; a man liberated could strive for the status of Overman. But what happens if a man refuses to let go of his “dead” God and remains too fearful to evolve into an Overman? Rejecting the concept of the Christian God means renouncing the scapegoat for the sins of man and accepting responsibility for one’s own actions. In The Metamorphosis Gregor Samsa plays the god-like role of financial provider for his family. However, when his transformation renders him useless in this role, the rest of Samsa’s family undergoes a change of its own: Kafka uses the metamorphoses of both Gregor and his family to illustrate a modern crisis.

Some comments on the structure: Two provocative introductory sentences, then a transition question and a response that presents the central idea of the essay. Next, introduction of the text and characters under discussion. Finally, the topic sentence of the paragraph, which, as the thesis statement, promises an interpretation. A paragraph such as this engages the reader’s interest right away and makes the reader look forward to the rest of the essay.

From a student essay on the question, “What Do Historians of Childhood Do?”

In his 1982 book The Disappearance of Childhood , Neil Postman argues that the concept of childhood is a recent invention of literate society, enabled by the invention of moveable-type printing. Postman says as a result of television, literate adulthood and preliterate childhood are both vanishing. While Postman’s indictment of TV-culture is provocative, he ignores race, class, ideology, and economic circumstance as factors in the experience of both children and adults. Worse, he ignores history, making sweeping generalizations such as the claim that the pre-modern Greeks had no concept of children. These claims are contradicted by the appearance of children in classical Greek literature and in the Christian Gospels, written in Greek, which admonish their readers to “be as children.” A more useful and much more interesting observation might be that the idea of childhood and the experience of young people has changed significantly since ancient times, and continues to change.

Some comments on the structure: Like the previous example, this essay begins with a statement from a text (this time with a paraphrase rather than a quotation) and builds towards a thesis statement. In this case the build-up, where the writer disagrees with one of the class texts, is stronger than the thesis. The writer has not stated exactly what he will argue, aside from saying he finds at least some of the ideas of childhood advanced in the course materials unsatisfactory. Keeping the reader in suspense may add to the interest of the essay, but in a short paper it might also waste valuable time and leave the reader unsure whether the writer has really thought things through.

From an essay on Crime and Punishment :

“Freedom depends upon the real…It is as impossible to exercise freedom in an unreal world as it is to jump while you are falling” (Colin Wilson, The Outsider, p. 39). Even without God, modern man is still tempted to create unreal worlds. In Feodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment Raskolnikov conceives the fantastic theory of the “overman.” After committing murder in an attempt to satisfy his theory, Raskolnikov falls into a delirious, death-like state; then, Lazarus-like, he is raised from the “dead.” His “resurrection” is not, as some critics suggest, a consequence of his love for Sonya and Sonya’s God. Rather, his salvation results from the freedom he gains when he chooses to live without illusions.

Comments: Once more, a stimulating opening. Between the first and last sentences, which frame the paragraph (the last one, as well as being the thesis sentence, is the specific application of the general first sentence), the writer makes her transition to the central idea and introduces the text and character she wishes to discuss. The reader is given enough information to know what to expect. It promises to be an interesting essay.

Each of the writers above chooses to open with a quotation or reference that helps to focus the reader’s attention and reveal the point of view from which a specific interpretation will be made. Movement from the general to the specific is very common in introductory thesis paragraphs, but it is not obligatory. You can begin with your thesis statement as the first sentence; start with a question; or use the entire opening paragraph to set the scene and provide background, then present your thesis in the second paragraph. Make choices and even create new options, so long as your sentences move to create a dominant impression on the reader.

Examples: Middle Paragraphs

From a student essay comparing P’u Sung-ling’s (17th century) The Cricket Boy and Franz Kafka’s (20th century) The Metamorphosis , two stories that deal with a son’s relationship to his family. (The writer’s thesis: according to these authors, one must connect in meaningful ways with other human beings in order to achieve what Virginia Woolf calls “health,” “truth,” and “happiness.”)

The most obvious similarity between Kiti and Gregor is that they both take the forms of insects; however, their and their families’ reactions to the changes account for the essential difference between the characters. Whereas Kiti thinks a cricket represents “all that [is] good and strong and beautiful in the world ( Cricket Boy , p. 2), Gregor is repulsed by his insect body and “closes his eyes so as not to have to see his squirming legs” ( Metamorphosis , p, 3). Their situations also affect their families differently. Kiti’s experience serves as a catalyst that brings his family closer together: “For the first time, his father had become human, and he loved his father then” ( CB , p. 2). Gregor’s transformation, on the other hand, succeeds in further alienating him from his family: his parents “could not bring themselves to come in to him” ( M , p. 31). While Kiti and his parents develop a bond based on understanding and mutual respect, Gregor becomes not only emotionally estranged from his family, but also physically separated from them.

Some comments on the structure: The writer is clearly on her way, with specific examples from the texts, to supporting her argument concerning the need for self-respect and communication. Notice that she uses transitions such as “however,” “whereas,” “also,” “on the other hand,” while,” and “not only…, but also…” to connect her thoughts and make her sentences cohere. Transitional words and phrases are the “glue” both within and between paragraphs: they help writers stick to the point, and also allow readers to stay on the path the writer intends.

Transitions

Writers use transitional words and expressions as markers to guide readers on their exploratory journey. They can express relationships very explicitly , which is often exactly what is needed. However, experienced writers can also build more subtle bridges between ideas, hinting at relationships with implicit transitions. These relationships may change from vague impressions to a very concrete statement, as the argument develops, allowing the reader to “discover” the writer’s conclusion as the essay builds to its final paragraph.

Examples of explicit transitional expressions

- Comparison: such as, like, similarly, likewise, in the same way, in comparison, correspondingly, analogous to

- Contrast: but, however, in contrast, although, different from, opposing, another distinction, paradoxically

- Cause-effect: because, as a result, consequently, for this reason, produced, generated, yielded

- Sequence: initially, subsequently, at the onset, next, in turn, then, ultimately

- Emphasis: above all, of major interest, unequivocally, significantly, of great concern, notably

- Examples: for example, in this instance, specifically, such as, to illustrate, in particular

- Adding points: as well as, furthermore, also, moreover, in addition, again, besides

If you find that you are overusing explicit connectors and your transitions are beginning to feel mechanical (How many times have you used “furthermore” or “however”? How many “other hands” do you have?), you can improve the flow of your writing either by changing up the transitional expressions, or by shifting toward more implicit transitions. One technique is, in the first sentence of the new paragraph, refer (either explicitly or implicitly) to material in the preceding paragraph. For example:

When Alcibiades does give his speech, we see that his example is Socrates himself.

While this interpretation still seems reasonable, I was surprised at the difficulty of uncovering useable data in the records of past societies.

This sometimes sickening detail that Dante uses to draw the reader emotionally into the Inferno also stimulates the reader to think about what he or she feels.

The Greek system is much more relaxed; obeisance and respect for the gods is not required, although in most cases it seems to make life easier.

Each of these implicit transition sentences builds on the previous paragraph and calls for support in the new paragraph. Even more subtle (that is, more difficult) would be to make the last sentence of the paragraph indicate the direction the next paragraph will take. If you try this, be careful you do not at the same time change the subject. You do not want to introduce a new idea at the end of a paragraph, and destroy its unity. Since it suggests a change in direction, we see this device used most commonly with thesis sentences at the end of introductory paragraphs, or in transitional paragraphs like the example above.

Other examples of hinges writers use to make connections include pronouns referring back to nouns in the previous paragraphs and synonyms to avoid repetition and overuse of pronouns. A good rule is not to overuse any device.

Concluding Paragraphs

From a student essay on Crime and Punishment :

Raskolnikov finally finds a new life:

Indeed he [is] not consciously reasoning at all; he [can] only feel . Life [has] taken the place of logic and something quite different must be worked out in his mind. (Epi. II, p. 464)

Thus he ends his suffering by abandoning intelligence and reasoning. Jean-Jacques Rousseau said that “above all the logic of the head is the feeling of the heart.” Ultimately, Raskolnikov transcends the “logic of the head” by discovering love and freedom.

Some comments on the structure: The paragraph works well as a conclusion because you can tell immediately that the writer has said all that she wants to say about the subject. She uses a quotation from another source, to “rub up against” Dostoevsky, expanding the dialogue between the text, the writer, and the reader by adding another voice. The answer to the “so what?” question is implied in the last sentence: love and freedom are values we all can share. Note that although this is a different conclusion from that of the earlier essay discussing Crime and Punishment , both interpretations are interesting and valid because both writers supported their arguments with careful readings of the text.

From a History essay analyzing the influence of Philippe Ariès’s book Centuries of Childhood on later historians:

In the end, Centuries of Childhood did not establish a conceptual framework for children’s history. Nor did the rival philosophies of history create a new paradigm for children’s history. Ariès identified a subject of study. He was a prospector who uncovered a rich vein of material. Subsequent miners should use whatever tools and techniques are best suited to getting the ore out of the ground. Historians should stop fighting over theories and get to work uncovering the lives of children and families. This will involve, as Jordanova suggested, self-awareness and sensitivity. But it should not be sidetracked by ideological debates. As Cunningham observed, the stakes for modern children and families are high. To make children’s history useful for the present, historians of children and families need to put aside their differences and get back to work.

Some comments on the structure: As in the previous example, the writer includes the perspectives of other commentators. This is especially common in essays on secondary sources in history, because “historiography” is often imagined as an ongoing conversation about primary and important secondary texts. The “so what” statement is more explicit this time, relating the study of children in the past to improving the lives of children and families today. The importance of connecting with the needs of today is problematic (many historians would criticize this as “presentism”); so the writer includes a supporting perspective from a sympathetic commentator.

From an essay in which the writer compares and contrasts the character she is examining with a character from another work:

Like Ophelia, Gretchen has moments of confusion and despair, but she decides to give in to her feelings and take responsibility for them. By having Gretchen freely stay behind to face her execution, Goethe casts aside any similarities that his character shares with Shakespeare’s Ophelia. Along with the empowering freedom of Gretchen’s striving comes the struggle to act rightly. But if no objective absolutes exist, according to Goethe’s God, on what basis can Gretchen make her decisions in order to be saved? She comes to the realization that the only absolutes exist within herself. Goethe’s God saves her, not for being a penitent Christian, but for staying true to these self-imposed absolutes.

Some comments on the structure: Another strong conclusion. The writer’s interpretation could be contested, but she has argued it well and convincingly throughout the essay and concluded strongly. Incidentally, note also that by specifying “Goethe’s God” in her interpretation she avoids any distracting discussion of religion and keeps her writing focused on literary analysis. We don’t argue the nature of “God” in an essay about literature; only the nature of the “God” in the text.

A Short Handbook for writing essays in the Humanities and Social Sciences Copyright © 2019 by Salvatore F. Allosso and Dan Allosso is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- WRITING SKILLS

Coherence in Writing

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Writing Skills:

- A - Z List of Writing Skills

The Essentials of Writing

- Common Mistakes in Writing

- Introduction to Grammar

- Improving Your Grammar

- Active and Passive Voice

- Punctuation

- Clarity in Writing

- Writing Concisely

- Gender Neutral Language

- Figurative Language

- When to Use Capital Letters

- Using Plain English

- Writing in UK and US English

- Understanding (and Avoiding) Clichés

- The Importance of Structure

- Know Your Audience

- Know Your Medium

- Formal and Informal Writing Styles

- Note-Taking from Reading

- Note-Taking for Verbal Exchanges

- Creative Writing

- Top Tips for Writing Fiction

- Writer's Voice

- Writing for Children

- Writing for Pleasure

- Writing for the Internet

- Journalistic Writing

- Technical Writing

- Academic Writing

- Editing and Proofreading

Writing Specific Documents

- Writing a CV or Résumé

- Writing a Covering Letter

- Writing a Personal Statement

- Writing Reviews

- Using LinkedIn Effectively

- Business Writing

- Study Skills

- Writing Your Dissertation or Thesis

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Have you ever read a piece of writing and wondered what point the writer was trying to make? If so, that piece of writing probably lacked coherence. Coherence is an important aspect of good writing—as important as good grammar or spelling. However, it is also rather harder to learn how to do it, because it is not a matter of simple rules.

Coherent writing moves smoothly between ideas. It guides the reader through an argument or series of points using signposts and connectors. It generally has a clear structure and consistent tone, with little or no repetition. Coherent writing feels planned —usually because it is. This page provides some tips to help you to develop your ability to write coherently.

Defining Coherence

Dictionary definition of coherence

cohere , v. to stick together, to be consistent, to fit together in a consistent, orderly whole.

coherence , a sticking together, consistency.

Source: Chambers English Dictionary, 1989 edition.

The dictionary definition of coherence is clear enough—but what does that mean in practical terms for writers?

Once you have achieved coherence in your writing, you will find that:

Your sentences and ideas are connected and flow together;

Readers can move easily through the text from one sentence, paragraph or idea to the next; and

Readers will be able to follow the ideas and main points of the text.

On the other hand, a text that is NOT coherent jumps between ideas without making clear connections between them. It is often hard to follow the argument. Readers may find themselves unclear about the point of particular paragraphs or even whole sections. There may be odd sentences that do not fit well with the previous or following sentence, or paragraphs that repeat earlier ideas.

All these issues provide pointers for how to develop coherence.

Elements of Coherence

There are several different elements that contribute to coherence, or are closely linked to the concept.

They include:

Cohesion , or whether ideas are linked within and between sentences.

Unity , or the extent to which a sentence, paragraph or section focuses on a single idea or group or ideas. In any given paragraph, every sentence should be relevant to a single focus.

A joint effort

Together, cohesion and unity mean that sentences and paragraphs are connected around a central theme.

- Flow , or how the reader is led through the text. Some of this is about the ordering of ideas, but it also takes into account issues like phrasing, rhythm and style. Some people define flow as the quality that makes writing engaging and easy to read.

Levels of Coherence

We can consider coherence at several different levels. These include:

Within sentences. A sentence is coherent when it flows naturally, and uses correct grammar , spelling and punctuation . Coherence also includes the use of the most appropriate words, and avoidance of redundancy.

Between sentences . Coherence between sentences means that each sentence flows logically and naturally from the previous one. Connections are made between them so that readers can see the flow of ideas, and how each sentence is linked to the previous one.

Within paragraphs . This is a logical extension of coherence between sentences. Coherence within a paragraph means that the sentences within the paragraph work together as a whole to present a complete thesis or idea.

Why single-sentence paragraphs don’t work

This definition of ‘within paragraph’ coherence explains why you should (almost) never use single-sentence paragraphs. A single sentence is (almost) never going to be able to provide a complete summary of your thesis or idea.

Between paragraphs . For most pieces of writing, you will also need to consider how the paragraphs fit together. Each paragraph covers an idea or thesis—and must then be connected logically to the next paragraph, so that your overall thesis is built step-by-step.

Between subsections or sections . This final level of coherence is only really important for longer documents. You must create a logical flow between different sections, to guide your reader from one to the next so that they can follow the development of your ideas.

Techniques to Improve Coherence

The first step to improving coherence is to plan your writing in advance.

Decide on the main point that you want to make, and the ideas that will lead your reader towards your point. It is also helpful to consider your planned audience, and what they want from your text.

There is more about this in our page on Know Your Audience . You may also find it helpful to read our page on Know Your Medium , to check whether there is anything about your publishing medium that you need to consider ahead of starting to write.

There are some techniques that you can use to help improve coherence within your writing. These include:

Using transitional expressions and phrases to signal connections

Words and phrases like ‘however’, ‘because’, ‘therefore’, ‘additionally’, and ‘on the one hand... on the other’ can be used to signal connections between sentences and paragraphs.

WARNING! Real connections needed!

Transitional phrases and words should only be used where the ideas really are connected.

Just inserting transitional expressions will not connect your ideas. Instead, you need to create a reasonable progression of ideas through a paragraph or section.

You also need to use transitional expressions sparingly. Not all ideas need an obvious link—and sometimes putting one in can seem awkward and contrived.

Using repeating forms or parallel structures to emphasise links between ideas

Generally speaking, repetition of words and phrases is unadvisable.

However, used sparingly, you may be able to harness repetition as a way to signal connections between sentences or ideas.

For example, many research papers have a section setting out the limitations of the study. These limitations can often be quite diverse, which makes for a rather disjointed section. To overcome this issue, writers often use the form ‘First... Second... Finally...’ to demonstrate the links between the disparate ideas.

Using pronouns and synonyms to eliminate unnecessary repetition

Repetition is often the enemy of coherence because it interrupts your movement through the writing. You tend to get distracted by the repeated words, and lose the thread of the argument or idea.

Pronouns and synonyms are a good way to avoid repeating words and phrases. However, care is needed when using them, to avoid ambiguity. It is advisable NOT to use pronouns following a sentence with two elements that might take the same pronoun.

For example:

John was sure that Tom was wrong. He had made the same argument last week.

Who made the same argument last week? John or Tom?

It is better to use at least one name again than create ambiguity.

TOP TIP! Come back later

It is often hard to detect ambiguity in your own writing because you know what you wanted to say.

It is therefore a good idea to leave any piece of writing overnight, and read it again in the morning. This will often identify problems such as ambiguous pronouns, and give you a chance to revise them.

Revisit, Revise and Review

Alongside planning, the single most important thing that you can do to improve the coherence of a piece of writing is to review and revise it with the reader’s needs in mind.

When you have finished a piece of writing, put it aside for a while. Overnight is ideal, but longer is fine. Once you have had a chance to forget precisely what you meant, read it over again as if you were coming to it for the first time.

As you start to read, consider the focus of your text: the main point that you want to make.

With that in mind, consciously examine whether the ideas flow clearly through your sentences, paragraphs and sections. Can the reader grasp your argument and follow it through the text? Is there an obvious conclusion?

While you are reading, you should also consider whether there are any very long sentences. If so, shorten them, using transitional words or phrases to link them together effectively. This will make your writing easier to read, and it will naturally flow better.

A Final Thought

It is not always easy to know how to create more coherent writing.

The best way to do so is to plan your writing, and then review it carefully. You should particularly consider your focus, and your readers’ needs. In doing so, you may find it helpful to use some of the techniques described on this page—but they will not, in themselves, be sufficient without the planning and review.

Continue to: Writing Concisely Using Plain English

See also: The Importance of Structure in Writing Editing and Proofreading Copywriting

- Literary Terms

- Definition & Examples

- When & How to Write Coherently

I. What is Coherence?

Coherence describes the way anything, such as an argument (or part of an argument) “hangs together.” If something has coherence, its parts are well-connected and all heading in the same direction. Without coherence, a discussion may not make sense or may be difficult for the audience to follow. It’s an extremely important quality of formal writing.

Coherence is relevant to every level of organization, from the sentence level up to the complete argument. However, we’ll be focused on the paragraph level in this article. That’s because:

- Sentence-level coherence is a matter of grammar, and it would take too long to explain all the features of coherent grammar.

- Most people can already write a fairly coherent sentence, even if their grammar is not perfect.

- When you write coherent paragraphs, the argument as a whole will usually seem coherent to your readers.

Although coherence is primarily a feature of arguments, you may also hear people talk about the “coherence” of a story, poem, etc. However, in this context the term is extremely vague, so we’ll focus on formal essays for the sake of simplicity.

Coherence is, in the end, a matter of perception. This means it’s a completely subjective judgement. A piece of writing is coherent if and only if the reader thinks it is.

II. Examples of Coherence

There are many distinct features that help create a sense of coherence. Let’s look at an extended example and go through some of the features that make it seem coherent. Most people would agree that this is a fairly coherent paragraph:

Credit cards are convenient , but dangerous . People often get them in order to make large purchases easily without saving up lots of money in advance. This is especially helpful for purchases like cars, kitchen appliances, etc., that you may need to get without delay . However, this convenience comes at a high price : interest rates. The more money you put on your credit card, the more the bank or credit union will charge you for that convenience . If you’re not careful, credit card debt can quickly break the bank and leave you in very dire economic circumstances!

- Topic Sentence . The paragraph starts with a very clear, declarative topic sentence, and the rest of the paragraph follows that sentence. Everything in the paragraph is tied back to the statement in the beginning.

- Key terms . The term “credit card” appears repeatedly in this short paragraph. This signals the reader that the whole paragraph is about the subject of credit cards. Similarly, the word convenience (and related words) are also peppered throughout. In addition, the key term “ danger ” appears in the topic sentence and is then explained fully as the paragraph goes on.

- Defined terms . For most readers, the terms in this paragraph will be quite clear and will not need to be defined. Some readers, however, might not understand the term “interest rates,” and they would need an explanation. To these readers, the paragraph will seem less coherent !

Clear transitions . Each sentence flows into the next quite easily, and readers can follow the line of logic without too much effort.

III. The Importance of Coherence

Say you’re reading a piece of academic writing – maybe a textbook. As you read, you find yourself drifting off, having to read the same sentence over and over before you understand it. Maybe, after a while, you get frustrated and give up on the chapter. What happened?

Nine times out of ten, this is a symptom of incoherence. Your brain is unable to find a unified argument or narrative in the book. This may become frustrating and often happens when a book is above your current level of understanding. To someone else, the writing might seem perfectly coherent, because they understand the concepts involved. But from your perspective, the chapter seems incoherent. And as a result, you don’t get as much out of it as you otherwise would.

How can you avoid this in your own writing? How can you make sure that readers don’t misunderstand you (or just give up altogether)? The answer is to work on coherent writing. Coherence is perhaps the most important feature of argumentative writing. Without it, everything falls apart. If an argument is not coherent, it doesn’t matter how good the evidence is, or how beautiful the writing is: an incoherent argument will never persuade anyone or even hold their attention.

V. Examples in Literature and Scholarship

Since coherence is subjective, people will disagree about the examples. This is especially true in scholarly fields , where authors are writing for a very specific audience of experts; anyone outside that audience is likely to see the work as incoherent. For example, the various fields of analytic philosophy are a great place to look for coherence in scholarly work. Analytic philosophers are trained to write very carefully, with all the steps in the argument carefully laid out ahead of time. So their arguments usually have a remarkable internal coherence. However, analytic philosophy is a very obscure topic, and very few people are trained to understand the terms these scholars use! Thus, ironically, some of the most coherent writers in academia (from an expert perspective) usually come across as incoherent to the majority of readers.

For writing Indian Schools: a Nation’s Neglect , journalist Jill Burcum was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in the editorial writing category. An excellent example of coherence in journalistic writing, the editorial deals with the shabby federal schools that are meant for Native Americans on reservations. The essay’s paragraphs are much shorter than they would be in an essay. Yet each one still revolves around a single, tightly focused set of ideas. You can find key concepts (such as “neglect”) that run as themes throughout the piece. The whole editorial is also full of smooth and clear transitions.

VI. Examples in Media and Pop Culture

You can often see something like argumentative coherence in political satire. Good satire always focuses on a single question and lampoons it in a highly coherent manner. Watch, for example, Jon Stewart’s opening monologues on The Daily Show. Whatever your opinion on Stewart’s politics, it’s hard to argue with the fact that he uses terms carefully. He transitions smoothly and focuses on a single, tightly controlled set of concepts in each monologue.

Sports debates can also provide a good example of coherence. When you watch a show about sports (like SportsCenter or First Take), pay attention to the attributes of coherence. How do the hosts and guests use their terms? Do they repeat key terms? Do they start each monologue with a “topic sentence”? Do they stick to one topic, or do they go off on tangents?

VII. Related Terms

“Cogency” sounds like “coherence,” but means convincing or persuasive . The two terms are related, though: an argument cannot be cogent if it’s not coherent, because coherence is essential to persuasion. However, an argument could be coherent but not cogent (i.e. it’s clear, unified, and easy to read, but the argument does not persuade its reader).

Focus is also related to coherence. Often, coherence problems emerge when the focus is too broad. When the focus is broad, there are just too many parts to cover all at once, and writers struggle to maintain coherence.

List of Terms

- Alliteration

- Amplification

- Anachronism

- Anthropomorphism

- Antonomasia

- APA Citation

- Aposiopesis

- Autobiography

- Bildungsroman

- Characterization

- Circumlocution

- Cliffhanger

- Comic Relief

- Connotation

- Deus ex machina

- Deuteragonist

- Doppelganger

- Double Entendre

- Dramatic irony

- Equivocation

- Extended Metaphor

- Figures of Speech

- Flash-forward

- Foreshadowing

- Intertextuality

- Juxtaposition

- Literary Device

- Malapropism

- Onomatopoeia

- Parallelism

- Pathetic Fallacy

- Personification

- Point of View

- Polysyndeton

- Protagonist

- Red Herring

- Rhetorical Device

- Rhetorical Question

- Science Fiction

- Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Synesthesia

- Turning Point

- Understatement

- Urban Legend

- Verisimilitude

- Essay Guide

- Cite This Website

British Council Malaysia

- English schools

- myClass Login

- Show search Search Search Close search

How to write a cohesive essay

When it comes to writing, people usually emphasise the importance of good grammar and proper spelling. However, there is a third element that actually helps authors get their thoughts across to readers, that is cohesiveness in writing.

In writing, cohesiveness is the quality that makes it easier for people to read and understand an essay’s content. A cohesive essay has all its parts (beginning, middle, and end) united, supporting each other to inform or convince the reader.

Unfortunately, this is an element that even intermediate or advanced writers stumble on. While the writer’s thoughts are in their compositions, all too often readers find it difficult to understand what is being said because of the poor organisation of ideas. This article provides tips on how you can make your essay cohesive.

1. Identify the thesis statement of your essay

A thesis statement states what your position is regarding the topic you are discussing. To make an essay worth reading, you will need to make sure that you have a compelling stance.

However, identifying the thesis statement is only the first step. Each element that you put in your essay should be included in a way that supports your argument, which should be the focus of your writing. If you feel that some of the thoughts you initially included do not contribute to strengthening your position, it might be better to take them out when you revise your essay to have a more powerful piece.

2. Create an outline

One of the common mistakes made by writers is that they tend to add a lot of details to their essay which, while interesting, may not really be relevant to the topic at hand. Another problem is jumping from one thought to another, which can confuse a reader if they are not familiar with the subject.

Preparing an outline can help you avoid these difficulties. List the ideas you have in mind for your essay, and then see if you can arrange these thoughts in a way that would make it easy for your readers to understand what you are saying.

While discursive essays do not usually contain stories, the same principle still applies. Your writing should have an introduction, a discussion portion and a conclusion. Again, make sure that each segment supports and strengthens your thesis statement.

As a side note, a good way to write the conclusion of your essay is to mention the points that you raised in your introduction. At the same time, you should use this section to summarise main ideas and restate your position to drive the message home to your readers.

3. Make sure everything is connected

In connection to the previous point, make sure that each section of your essay is linked to the one after it. Think of your essay as a story: it should have a beginning, middle, and end, and the way that you write your piece should logically tie these elements together in a linear manner.

4. Proofread before submitting your essay

Make sure to review your composition prior to submission. In most cases, the first draft may be a bit disorganised because this is the first time that your thoughts have been laid out on paper. By reviewing what you have written, you will be able to see which parts need editing, and which ones can be rearranged to make your essay more easily understood by your readers. Try to look at what you wrote from the point of view of your audience. Will they be able to understand your train of thought, or do you need to reorganise some parts to make it easier for them to appreciate what you are saying? Taking another look at your essay and editing it can do wonders for how your composition flows.

Writing a cohesive essay could be a lot easier than you think – especially when you follow these steps. Don’t forget that reading complements writing: try reading essays on various topics and see if each of their parts supports their identified goal or argument.

Writing Resources: Developing Cohesion

Cohesion is a characteristic of a successful essay when it flows as a united whole ; meaning, there is unity and connectedness between all of the parts. Cohesion is a writing issue at a macro and micro level. At a macro-level, cohesion is the way a paper uses a thesis sentence, topic sentences, and transitions across paragraphs to help unify and focus a paper. On a micro-level, cohesion happens within the paragraph unit between sentences; when each sentence links back to the previous sentence and looks ahead to the next, there is cohesion across sentences. Cohesion is an important aspect of writing because it helps readers to follow the writer’s thinking.

Misconceptions & Stumbling Blocks

Many writers believe that you should avoid repetition at all costs. It’s true that strong writing tends to not feel repetitive in terms of style and word choice; however, some repetition is necessary in order to build an essay and even paragraphs that build on each other and develop logically. A pro tip when you’re drafting an essay would be to build in a lot of repetition and then as you revise, go through your essay and look for ways you can better develop your ideas by paraphrasing your argument and using appropriate synonyms.

Building Cohesion

Essay focus: macro cohesion.

Locate & read your thesis sentence and the first and last sentence of each paragraph. You might even highlight them and/or use a separate piece of paper to make note of the key ideas and subjects in each (that is, making a reverse outline while you’re reading).

- How do these sentences relate?

- How can you use the language of the thesis statement again in topic sentences to reconnect to the main argument?

- Does each paragraph clearly link back to the thesis? Is it clear how each paragraph adds to, extends, or complicates the thesis?

- Repetition of key terms and ideas (especially those that are key to the argument)

- Repetition of central arguments; ideally, more than repeating your argument, it evolves and develops as it encounters new supporting or conflicting evidence.

- Appropriate synonyms. Synonyms as well as restating (paraphrasing) main ideas and arguments both helps you to explain and develop the argument and to build cohesion in your essay.

Paragraph Focus: Micro Cohesion

For one paragraph, underline the subject and verb of each sentence.

- Does the paragraph have a consistent & narrow focus?

- Will readers see the connection between the sentences?

- Imagine that the there is a title for this paragraph: what would it be and how would it relate to the underlined words?

- Repetition of the central topic and a clear understanding of how the evidence in this paragraph pushes forward or complicates that idea.

- Variations on the topic

- Avoid unclear pronouns (e.g., it, this, these, etc.). Rather than using pronouns, try to state a clear and specific subject for each sentence. This is an opportunity to develop your meaning through naming your topic in different ways.

- Synonyms for key terms and ideas that help you to say your point in slightly new ways that also push forward your ideas.

Sentence to Sentence: Micro Cohesion

Looking at one paragraph, try to name what each sentence is doing to the previous: is it adding further explanation? Is it complicating the topic? Is it providing an example? Is it offering a counter-perspective? Sentences that build off of each other have movement that is intentional and purposeful; that is, the writer knows the purpose of each sentence and the work that each sentence accomplishes for the paragraph.

- Transition words (look up a chart) to link sentence and to more clearly name what you’re doing in each sentence (e.g., again, likewise, indeed, therefore, however, additionally, etc.)

- Precise verbs to help emphasize what the writer is doing and saying (if you’re working with a source/text) or what you’re doing and saying.

- Again, clear and precise subjects that continue to name your focus in each sentence.

A Link to a PDF Handout of this Writing Guide

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11 Unity & Coherence

Preserving unity.

Academic essays need unity, which means that all of the ideas in an essay need to relate to the thesis, and all of the ideas in a paragraph need to relate to the paragraph’s topic. It can be easy to get “off track” and start writing about an idea that is somewhat related to your main idea, but does not directly connect to your main point.

All of the sentences in a paragraph should stay “on track;” that is, they should connect to the topic. One way to preserve unity in a paragraph is to start with a topic sentence that shows the main idea of the paragraph. Then, make sure each sentence in the paragraph relates to that main idea.

If you find a sentence that goes off track, perhaps you need to start a separate paragraph to write more about that different idea. Each paragraph should generally have only one main idea.

As you pre-write and draft an essay, try to pause occasionally. Go back to the assignment prompt and re-read it to make sure you are staying on topic. Use the prompt to guide your essay; make sure you are addressing all of the questions. Do not just re-state the words in the prompt. Instead, respond to the questions with your own ideas, in your own words, and make sure everything connects to the prompt and your thesis.

Activity A ~ Finding Breaks in Unity

Consider the following paragraphs. Is there a topic sentence? If so, do all of the other sentences relate to the topic sentence? Can you find any sentences that don’t relate?