- Advanced Search

Version 1.0

Last updated 08 october 2014, nationalism.

This article offers an overview of the progress of nationalism and the national idea starting with its origins as a mass political programme during the French Revolution and tracing its passage up to the beginning of the First World War. It looks at a number of "pivotal" points in the history of nationalism: notably the French Revolution itself and its aftermath, the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the European Revolutions of 1848-49, the unifications of Germany and Italy in the latter-part of the 19 th century, and the apparent rising tide of nationalism in the Ottoman Balkans, especially in the last quarter of the 19 th century. Throughout, the idea of nationalism's uni-linear and irresistible rise is challenged, and this article shows instead the role of accident and contingency, as well as alternative programmes of political organization that challenged the national idea.

Table of Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Ideologies of Nationalism, 1789-1815

- 3 The Era of Metternich, 1815-1848

- 4 The “Springtime of Peoples”, 1848 and its Aftermath

- 5 German and Italian Unification, 1860-1871

- 6 The Eastern Question up to 1878

- 7 Towards Sarajevo

- 8 Conclusion

Selected Bibliography

Introduction ↑.

The history of nationalism in the pre-1914 period has often been refracted through the outcome of the First World War: 1918 is the point of departure, and preceding events and developments are selected and laid out in order to explain our arrival at this final station. The historiographies of the new nation-states of eastern and central Europe, and especially the war’s “victor states” of Poland , Romania , Czechoslovakia , and Yugoslavia , are very often representative of such national teleologies. Like the English Whig tradition, they tell of the forward and irresistible march of the national spirit, overcoming myriad obstacles and difficulties en route to its final affirmation. A corollary to the irresistible rise of the national idea is the decline of its imperial counterpart. Thus, historians have often looked for and found harbingers of imperial doom in the pre-war years. An early and influential study of Austria-Hungary’s last years saw a “multi-national” state wracked by “centrifugal” and “centripetal” forces, with the latter eventually proving terminal. [1] Even more dire was the case of the Ottoman Empire , whose decline was evident perhaps as soon as the early-modern period and could not be arrested by the various attempts at political, military, and bureaucratic reform in the 19 th century. [2] The Sarajevo assassination that sparked the First World War becomes an over-determined event: Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este’s (1863-1914) death at the hands of Gavrilo Princip (1894-1918) symbolizes the death blow dealt to Austria-Hungary by Serbia , which in turn symbolizes the death of the imperial, dynastic principle and its replacement with nationalism.

In reality the story is not so uni-linear: nationalism was one of many political forces at play in the pre-war period; a potent force, to be sure, but one with powerful opponents, and one whose all-conquering victory in 1918 was far from pre-ordained, owing as it did much to the war itself and its unexpected outcome. This article charts the expansions and contractions of nationalism and the national idea throughout the 19 th century by highlighting a series of pivotal points in the modern period (post-1789), wherein nationalism as ideology and political programme took shape. Those points are: the revolution in France and its impact throughout Europe, 1789-1815; the liberal and national revolutions of 1848-1849 and their aftermath (especially in the Habsburg lands); the national unifications of Italy and Germany in the second half of the 19 th century and their consequences on the system of alliances in international relations in the latter-half of the 19 th century; and, in the same period, the “Eastern Question”, that is, the diminishing authority of the Ottoman Empire in Europe and the attempts of the remaining Great Powers to manage the changes to the balance of power in international relations that this caused. The final section covers the decade before the outbreak of the war, focusing primarily on developments in the Balkans (especially during the wars of 1912-1913 ) and this region’s role in international relations on the eve of the First World War. The intention throughout is to undercut the “inevitability” thesis of both the rise of nationalism and the decline of empire , and to show instead that whilst nationalism seriously unsettled internal politics and international relations in Europe before the war, there were many who believed it could be suppressed, or managed, or even reconciled to the existing order. Only the violence of the war and its outcome shattered such beliefs.

Ideologies of Nationalism, 1789-1815 ↑

The ideology of nationalism is intimately connected to the revolutionary turmoil that began in France at the end of the 18 th century and thereafter spread across Europe. The end of Bourbon rule in France offered a glimpse of a political order in which sovereignty was not concentrated in a single monarch, divinely ordained, but instead resided at a popular level, with the people: the “nation.” The levée en masse and the Napoleonic wars that followed the revolution swept these ideas throughout the continent and beyond, bringing the revolutionary programme as far as Spain in the west, partitioned Poland in the east, and Dalmatia in the south. The many locations inscribed unto the Arc de Triomphe in Paris are a testament to the military prowess of the levée en masse and the Napoleonic armies; they also give a partial sense of how many lands and peoples came into contact with the revolution’s programme and ideals. Partial, because the Arc does not include any locations in the Habsburg, Russian and Ottoman Empires, regions that were not occupied by the Napoleonic armies, but where the ideals of the French Revolution also spread. The radical challenge of the French Revolution to the absolutist order throughout Europe provoked a response, a “counter-revolution”, in which various international coalitions attempted to halt the revolution’s progress. In these conflicts at the beginning of the 19 th century, the counter-revolution was eventually triumphant, and absolutist rule was re-asserted and confirmed at the Congress of Vienna in 1815. However, as we shall see, the men who conducted the Congress of Vienna could not erase the memory of the revolutionary years, and the forces of revolution and counter-revolution, of absolutism and Enlightenment, and of nation and empire would continue to collide throughout the 19 th century. Political sovereignty and political organization were now hotly contested spheres, and this was true not only in Paris, but also in Vienna, Warsaw, Moscow, and Constantinople. Nationalism, then, introduced a disequilibrium into the political order throughout Europe, one that would continue to shape international relations until the outbreak of the First World War.

The French Revolution was the child of the Enlightenment, but it was also the parent of modern and mass politics. The notion that sovereignty was the property of the people obviously called for a much broader level of political participation and mobilization than had existed previously. No longer were the people the passive subjects of absolutist rule, they were the “nation”, the very life-blood of the body politic. The success of the levée en masse and the French army’s victories throughout Europe (at least until 1815) seemed to provide a living example of this maxim. Indeed, the orthodox opinion (not entirely undisputed) amongst theorists is that nationalism is a modern phenomenon. [3] Moreover, its successful dissemination and promotion at a mass level requires a modern infrastructure of communicative technologies and institutions, literacy, print culture, at least a primary level of education, and perhaps some form of associational life. [4] Thus, according to the influential study by Eugen Weber (1925-2007) , Peasants into Frenchmen , the spread of the national idea throughout France was not achieved until towards the end of the 19 th century, when education, print culture, and literacy, the vessels of the national idea, had taken root across the country, dissolving the local and regional identities of French men and women and replacing them with a unitary sense of national identity. [5]

The men of the French Revolution were educated bourgeoisie, lawyers, journalists, acting and speaking on behalf of the masses, but themselves part of a social elite. Their job, and that of their successors, was to help the national idea trickle down to the broader strata of the nation itself: “the masses.” This was true wherever a national programme existed. In an important sociological study of the spread of nationalism in East Central Europe, Miroslav Hroch identifies a three-stage process to the dissemination of the national idea, starting with its incubation within a tiny group of intellectuals, moving to a broader strata of patriots and nationalist activists, and finally permeating the population at large. [6]

The spread of nationalism, then, could be helped or hindered depending on the extent to which the lands in question had been touched by modernization. Nationalism penetrated more slowly, or not at all, in pre-industrial and agrarian parts of the country, East Central and South Eastern Europe, Russia, the Ottoman lands in Anatolia, and so on. [7] Thus, nationalist activists, promoters of the national cause in “pre-awakened” societies, might face two obstacles: on the one hand, from above, the conservative forces of empire and absolutism, attempting to suppress the national idea, and on the other, the people themselves, the material of the nationalists' political project who did not (at least not yet) acknowledge their national identity, embracing instead local or regional identities. Moreover, nationalist activists in central and eastern Europe were both impressed by the progress of national programmes in the industrialized and modern parts of Europe to their west, and were also somewhat ashamed that their own societies were falling behind. National ideologies spread unevenly throughout Europe in the 19 th century, but the states in which they had made most advances (France, and later Italy and Germany ) became the blueprint for less developed “nations.” Looking forward, the post-war settlement of 1918 reflects to a great extent the aspirations of nationalist activists in central and eastern Europe to “catch up” with their western neighbors, a desire which had remained constant throughout much of the 19 th century.

Part of the process of making nationalism a programme attractive and comprehensible to the masses involved veiling its modern and novel character. Often national activists would cast the nation and the national idea back into a primordial past, asserting that the nation had existed always and throughout time, instead of owning that it was a product of the modern age. Theorists of nationalism have almost uniformly rejected the idea of the nation as a perennial and primordial force; although a significant few have noted that the historical materials out of which national identities are constructed are not produced out of thin air, and that modern nationalisms have at least some basis in pre-national and pre-modern “myths” and “memories.” [8]

Such myths and memories were especially prevalent in central and eastern Europe: during the early-modern period the Habsburg, Ottoman, and Russian Empires had defeated and subsumed numerous medieval states in this region, upon whose ruins they now stood. Thus, Serbian nationalist awakeners stoked the embers of the medieval Serbian kingdom/empire, lost to the Serbs following the defeat of “Tsar” Lazar Hrebeljanović (1329?–1389) to the Ottomans at the Field of Blackbirds (Kosovo polje) in 1389. Bulgarian national awakeners spoke of Simeon I, King of Bulgaria’s (864?-927) great state, the largest of the medieval Balkan kingdoms. [9] Czech historian and “father of the nation” František Palacký (1798-1876) , speaking of his own nation, told of how “we were in existence before Austria and we will still be here after she is gone.” [10] The history that these nationalists selected was usually of a certain kind, as Timothy Snyder has noted: they most frequently evoked the medieval period, choosing a romanticized and, importantly, ethnically exclusive conceptions of nation over a multi-confessional or latitudinarian one. This move was most apparent in the case of Poland, where, in the 19 th century, nationalists overlooked the “multi-national” and noble early-modern kingdom of Poland-Lithuania in favor of the medieval Polish state, highlighting its victories against the Teutonic Knights. [11]

This, of course, was an eminently usable history for nations that were still subsumed into empires (Habsburg, Ottoman, Russian). Romantic nationalism of this kind tended to take the form of a triptych: the first panel depicted the glory of a golden age; the second panel, its fall; and the third, still to be painted, its restoration, which would be achieved in the near future at the expense of imperial masters. The goal was not cohabitation, which was, in most cases, already in existence, but rather the creation of an autonomous or even independent nation. The goal was to break out of the “prison of nations”, not to co-exist with other groups within it. Nationalism and national identity was in this way established as an oppositional force against empire, and was thus seen, quite correctly, as a potential threat to the imperial status quo in the Habsburg and Ottoman lands. As we shall see, this threat became ever starker as nationalism gained traction throughout Europe following the integrations of Italy and Germany in the latter part of the 19 th century.

The Era of Metternich, 1815-1848 ↑

As noted, the French Revolution sent shockwaves throughout the continent, both in terms of the immediate military successes of the Napoleonic armies and in the longer-term example of its popular challenge to the absolutist order in Europe, an example which could be emulated by peoples across the continent, even after the original revolutionary flames had been dowsed. Nowhere was this truer than in the Habsburg empire, which was at the beginning of the 19 th century an absolutist state held together through its imperial institutions and the dynastic principle, but whose subjects were divided by numerous languages, religions, and historical traditions , all of which had the potential to serve as the material for nationalist awakening in the wake of 1789. To an extent, this apparent fragmenting of imperial rule during the 19 th century along national lines was related to modernization; since nationalism and national identity are closely linked to modernity and modernization, the passing of the Habsburg monarchy into the modern era was also the passing of the traditional means of imperial rule and life and the rise of discrete national forces.

The Habsburg Empire was a member of the international coalition that defeated Napoleon in 1815, and it was in the Habsburg capital, Vienna, in the same year that the victorious forces of “counter-revolution” met to agree on the re-establishment of absolutism in post-Napoleonic Europe. One of the guiding forces behind this re-establishment was Klemens von Metternich (1773-1859) , the Austrian chancellor who saw in the French Revolution and its legacy as both a foreign and a domestic threat to the Habsburg Empire. In the wake of the revolutionary turmoil that had engulfed Europe, Metternich hoped to establish a system of international relations, a “concert”, wherein the states of Europe, in spite of their many differences and rivalries, could work together to ensure revolutionary forces were kept in check. The “Concert of Europe” became the governing factor in international relations for the entire 19 th century and up to the outbreak of the First World War. [12] It was, in fact, simply an informal arrangement between the conservative powers of Europe based on an understanding that their mutual interests outweighed their various economic and political rivalries, and that it was therefore in their interests to work together. [13]

Yet as the 19 th century wore on and the rivalries between the Great Powers became more entrenched, Metternich’s concert was increasingly unharmonious. The Great Power rivalries and vested interests tied up with the Eastern Question (see below), and the establishment of entrenched and adversarial political and (potentially) military alliances at the end of the 19 th and beginning of the 20 th century, drastically diminished the common ground upon which the Concert of Europe had once stood. This, then, was Metternich’s first legacy, a less than sturdy system of international relations that, despite its successes, was perhaps incapable of bypassing the realist political and economic concerns of its members, and certainly incapable of bringing Europe back from the brink in 1914.

Metternich’s second legacy was domestic, for the Austrian chancellor recognized that the revolutionary spirit of 1789 was an example to many subjects within the Austrian Empire. The challenge of nationalism to the Habsburgs was, potentially, very severe, for the monarchy, dominated politically and culturally by its Germanic subjects, was, as noted, made up of disparate “peoples” with various languages, religions, and historical traditions. Nationalism, should it seep into the Habsburg monarchy, threatened to turn the empire from an integral state into a multi-national and fragmented empire. Metternich’s answer to this challenge was a comprehensive system of surveillance, policing, and censorship that has made his domestic policies a byword for oppression and reaction. [14] Yet Metternich’s chief concern was the risk of nationalism (and liberalism) manifesting themselves in the politics of the Habsburg empire: the chancellor considered cultural and literary expressions of national identity to be more innocuous and manageable. [15] Thus, the period of absolutist reaction after 1815 is also the period of the first flickers of cultural national renaissance in the Habsburg lands, especially among the Slav population. It marked the appearance of vernacular newspapers and reading rooms, for example, as well as early forms of nationalist associational life, sporting and singing societies, and gymnastic organizations. The impact of these initiatives was often very restricted: the actual and indeed potential readership for vernacular newspapers was in most cases very low, given the levels of literacy in certain parts of the monarchy, and membership to nationalist associations was not nearly as high as many activists had hoped. Metternich’s absolutism was often not the only obstacle standing in the nationalists’ path: there was also the “national indifference” of the very people being targeted. As Pieter Judson and others have shown, national identity in the 19 th century was very often subordinate, or even non-existent, with people turning instead to local, regional, or other forms of identification. [16]

The “Springtime of Peoples”, 1848 and its Aftermath ↑

Metternich’s energetic censorship and policing did not render the Habsburgs immune to the transnational revolutionary temper in Europe during the so-called “Springtime of Peoples” of 1848-1849, which challenged the absolutist order that had been established at the Congress of Vienna almost everywhere. [17] In many parts of Europe, the challenges to the absolutist status quo came from liberals demanding, for example, a constitution that curtailed imperial or monarchic rule, or a parliament that allowed for some kind of popular representation. The turmoil of 1848-1849 in the Habsburg lands, however, was also an attempt at national revolution, with many of the non-Germanic peoples in the Habsburg Empire calling for some kind of autonomy, even independence.

The most serious threat to the Habsburgs in this respect came from Hungary, where, during the unrest of 1848-1849, the nationalist torch passed from István Széchenyi (1791-1860) to Lajos Kossuth (1802-1892) , that is, from an evolutionary and pragmatic approach to the Hungarian national question, to a revolutionary one. [18] Just as in 1815, the international forces of counter-revolution eventually defeated the men and women of 1848-1849. Nevertheless, after the military successes of 1848-1849, and a subsequent period of “Neo-Absolutism” lasting from 1849-1860, Habsburg rulers could no longer hope to exclude outright the national question from the political sphere in the manner attempted by Metternich (who fell from power as a result of the events of 1848). A fact that was essentially acknowledged with the Ausgleich (Compromise) of 1867, when, following a disastrous defeat at the hands of Prussia (see below), the Habsburg Empire was reorganized on a dualist basis as “Austria-Hungary”, devolving large amounts of political and economic power to the Hungarians.

The Austro-Hungarian agreement showed that nationalism was not necessarily an irresistibly corrosive force seeping through the sinews of the Habsburg State. The Ausgleich complicates the notion, long-held in the historiography of the origins of the First World War, that nation and empire were diametrically opposed forces, irreconcilable to each other and thus bound to clash violently. To be sure, and as already noted, many national activists set out their programmes in strict opposition to empire, but many were also ready to accept that the national idea would need to accommodate itself within the empire, just as the more far-sighted of the monarchy’s rulers accepted the existence of nationalism and the need for it to be managed within the imperial framework. The example of Hungary’s compromise with Vienna in 1867 showed precisely this (although admittedly there had been much blood and toil on the path towards this arrangement). Timothy Snyder’s biography of Wilhelm von Habsburg, Archduke of Austria (1895-1948) , a minor figure in the Habsburg dynasty, shows how the royal family understood, at least after 1849, that nationalism could not be smothered under oppressive policing and censorship, and rather that the empire, in order to survive, would have to adapt to this new ideology. For Wilhelm’s family, this meant the sponsoring of a “friendly” nation such as the Poles, who could be enticed to work towards national goals within the empire. [19]

German and Italian Unification, 1860-1871 ↑

In the last quarter of the 19 th century, the Habsburg approach of squaring nationalist forces with imperial realities was looking increasingly anachronistic. This was not only because of the ever-greater appeal of nationalism to the subject peoples of the Habsburg Empire; it was also due to the emergence, in quick succession but under very different circumstances, of two powerful new national states onto the European stage: Italy and Germany. The emergence of Germany, in particular, dramatically altered the balance of power in Europe and changed the nature of international relations in the last quarter of the 19 th century.

The unification of Italy, however, came first in 1859-1860, following important military victories for Italian nationalist forces (in alliance with imperial France) over the Habsburgs at Magenta and Solferino. It marked the culmination of the Italian “Risorgimento” [20] of the second-half of the 19 th century, [21] a nationalist awakening with political, social, and cultural dimensions. The Risorgimento had two main tributaries in the political sphere: the liberal, political vision of Camillo di Cavour (1810-1861) , Prime Minister of Piedmont-Sardinia (the Kingdom of Sardinia), who hoped that the economically and socially disparate Italian territories would coalesce under the liberal tutelage of Piedmont; and the popular, romantic, and revolutionary vision of Giuseppe Mazzini (1805-1872) , founder of the secret society “Young Italy”, a group that hoped to galvanize the Italian masses through revolutionary action. Whereas Cavour believed that Piedmont, with its liberal politics and its constitutional monarchy, should serve as the nucleus of the new unitary Italy, enlarging its political system and institutions so as to cover the entire country, Mazzini saw such political traditions as too sterile to ignite the passions of the masses.

The unification, achieved with assistance in Sicily from the colourful adventurer and Mazzinian Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882) , left a number of matters still unresolved. The Roman Papal States, which rejected the secular forces of the Risorgimento, were now a Catholic and autonomous zone “imprisoned” in the Vatican. There were also many territories coveted by the men of the Risorgimento that remained outside of the unified Italian state: the unredeemed lands, or Italia Irredenta : the Trentino in the Austria Tyrol and various cities and towns on the Adriatic coast, most importantly the key port of Trieste. The desire for “repossession” of these lands would strongly influence the decision in favour of intervention in the war in 1915, and would continue to shape Italian foreign policy throughout the interwar period and even into the Cold War. Of even greater urgency was the fact that, in spite of the political union of Italy, many subjects of the new state did not identify strongly - or indeed at all - with the Italian nation. The great differences in social and economic fortunes in the various parts of the new state, the prevalence of regional, local, or confessional identities, were all great enemies of the Cavourian and Mazzinian dream of a united and integral Italy. The Italian statesman, novelist and painter Massimo d’Azeglio (1798-1866) wrote plaintively in his memoirs in the wake of the unification of 1861 that, “Italy has been made, now it remains to make Italians.” No doubt national activists of all stripes and from across the continent could sympathize with d’Azeglio’s desire to awaken in the masses a coherent and permanent sense of national affiliation. No doubt also there were many national activists who would have settled for a national state of the Italian kind regardless of whether the masses knew what it was or why they should be loyal to it: the work of national awakening could be carried out to great effect when the political, bureaucratic, and educational institutions of a national state were at one’s disposal.

Both the Cavourian and Mazzinian approaches to state- and nation-building served as inspiration and example to national activists throughout Europe. “Piedmont” became synonymous with the process of a political and national integration carried out under the benign and paternal leadership of a large, politically advanced region that would serve as the instrument of national unification. Many Poles came to see Galicia, in Austrian Poland, as the “Piedmont” that would embrace and assimilate the lands of Prussian and Russian Poland. [22] Once Serbia had achieved national independence in the last quarter of the 19 th century (see below), many Serbs believed it was their country’s historic role to act as the “Piedmont” of South Slav unification. There was also a Mazzinian legacy. Mazzini had seen nationalism as the way of the future not just for Italians but for all peoples throughout the continent: a universal and propulsive “young” force that would sweep away the aging and moribund European empires. “Young Italy” in this sense was just one part of a larger network of nationalist groups included in “Young Europe.” In the Mazzinian vision, Europe would achieve true harmony and equilibrium through its reorganization along national lines and into nation-states. Here was a dream of peaceful coexistence, not of violent confrontation. It was not far removed from the Wilsonian vision that was applied to Europe after the First World War. Indeed, many Europeans were duly impressed with the vigour of Mazzini and the success of this underground, conspiratorial network. Perhaps the most notorious group to try and emulate Mazzini’s example was “Young Bosnia”, the loosely-knit group of revolutionary South Slav youths whose number included Gavrilo Princip, the assassin of the Habsburg Archduke Franz Ferdinand. [23]

The other great national unification of the second-half of the 19 th century, that of Germany, took place under very different circumstances. Whereas Italy was unified largely through the efforts of the constitutional monarchy of Piedmont-Sardinia, and thus came to adopt the liberal traditions of that state at a national level, the German principalities came together by the force of the largest pre-1871 German state, Prussia, and with the political, diplomatic, and military efforts of the Prussian Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898) , Prime Minister from 1862. Prussia was a far more conservative state than Piedmont, and a far more conservative state than many of the remaining German principalities, which it dwarfed in terms of political and industrial might. The sources of political power in Prussia were almost uniformly conservative in outlook: the ruling Hohenzollern dynasty was supported by the ambitious and powerful “Junker” class, a group of large landowners vehemently opposed to liberal politics within their own state. This class was well represented in the officer corps of the Prussian army, a disproportionately large institution that enjoyed great prestige within the state. [24] Bismarck’s goal of national unification was not shared by all Junkers, many of whom remained sceptical about the subversion of Prussia within Germany.

Bismarck, himself the heir of a Junker family, sought to create a strong, unified German state under Prussian auspices, in which the autocratic political tradition from which he hailed would not be too diluted. He was an exponent, then, of the Kleindeutsch solution to the question of German unification, in which the putative German state, once unified, would exclude the Austrian lands and be dominated by Prussia. The alternate vision, the Großdeutsch solution, sought a larger German state that would include, and therefore be dominated by, Austria. Ultimately, it was Bismarck’s vision that sealed the unification of Germany. Following a series of wars that the Prussian army and government prosecuted successfully from 1864-1871, beginning in Schleswig-Holstein against the Danes , then against Austria in 1866, and finally, most spectacularly, against France in 1870-1871, the unification of the German states was completed. [25]

The triumph of the Kleindeutsch over the Großdeutsch solution to German unification was also a great triumph of the Bismarckian programme of integral nationalism over the Habsburgs’ multinational imperialism . Seen in comparison to the dynamism and potency of the newly unified German national state, Austria-Hungary looked increasingly out of step with the times, which seemed to belong to the likes of Bismarck, Mazzini, Kossuth, to name but some. The arrival of a powerful industrial state hailed a new balance of power in European international relations: a new force with which the Great Powers would have to reckon.

The Eastern Question up to 1878 ↑

The new sources of military and industrial power in Europe following the unification of Italy and, especially, Germany, also created a new climate in international relations. The Concert system established by Metternich in the first half of the 19 th century, despite its numerous successes in maintaining an equilibrium in the continent, was looking increasingly incapable of meeting the challenges of the Realpolitik of the late 19 th century and of the more solid and potentially antagonistic alliance blocks which were formed around this time. The most pressing concern in international relations in the latter part of the 19 th century was the weakening of the Ottoman Empire, a state which was apparently unable to compete in the power politics of the period. The crisis this caused was known as the “Eastern Question”, and for each of the remaining Great Powers the Eastern Question meant at best expanding their own interests and influence into the vacuum that Ottoman decline would inevitably create, especially in the Balkans. At worst, it meant maintaining equilibrium in the international balance of power by preventing any other of the Great Powers from capitalizing on the Ottoman Empire’s difficulties.

Within the Ottoman Empire itself there were a number of national activists who hoped also to capitalize on the declining power of the empire. Their work, however, was cut out by the social structure of the empire itself. It had never been a requirement of the subject peoples of the Ottoman Empire to convert to their rulers’ religion, Islam. Instead, the Ottoman Empire organized its non-Muslim peoples into broad confessional categories that were subordinate to Islamic institutions and subjects, the so-called “Millet” system. [26] Once this subordinate position in the social and political hierarchy was accepted, non-Muslim subjects could expect a level of autonomy and tolerance that was unmatched in the Christian empires (especially during the early modern period). Without the threat and practice of force there were few examples of mass and sustained conversion of Ottoman subject peoples to Islam (with notable exceptions in Bosnia, Albania and parts of Bulgaria ). The broad confessional categories created and upheld by the Millet system also stymied the development of discrete national identities and national groups, since it divided peoples not by language or territory but by religion. Greek Orthodox Christians shared a Millet with Bulgarian and Serbian Christians. Thus, national awakeners of the kind we have encountered previously were, in the Ottoman lands, faced with the challenge of disaggregating their putative national group from subject peoples with whom they shared a Millet. This was in addition to the challenges of separating their group from imperial rule itself. For this reason, the struggles of the national awakeners in the Ottoman lands were waged both against the Ottoman state and against rival programmes of national awakening. This second aspect of the national conflict became ever more pronounced in the last quarter of the 19 th century, since the entropy of Ottoman institutions and rule in Europe was becoming ever more apparent, and nationalists saw the greatest threats to the realization of their goals as coming not from the empire itself, but from other nationalists.

The first stirrings of what would become known as the “Balkan revolutionary tradition” took place in Serbia at the beginning of the 19 th century. In these parts, an absence of centralized Ottoman control and severe corruption of local administrators created the conditions for a largely spontaneous uprising on the part of the peasant Christian subjects. This uprising, which began in 1804, was directed in the first instance not against Ottoman rule itself, but rather against the Janissaries, the Ottoman military caste who were using their considerable powers to prey upon the local population. Eventually this transformed from a local dispute against the Janissaries into a more concerted attempt to gain political autonomy from the Ottomans. A subsequent revolt lasted from 1815-1817, and ended with the Porte conceding significant measures of self-government to the Serbs, thus creating the basis for what would become the Serbian national state. Yet another attempt at “national revolution” took place in the Greek lands during the 1820s, the so-called “Greek War of Independence”. This revolt was inspired by, and related to, the Serbian uprisings of the previous decades, but in many respects it was a more sophisticated and concerted challenge to Ottoman authority. The Greeks had better cultural and political representation than the largely socially undifferentiated Serbs. Notably, the Phanariot Greeks of Constantinople (so-called because they were based in the Phanar district of the imperial capital), were able to support and direct the efforts of the Greek revolution from outside its staging ground. Importantly, the Greek war had the support of France, Britain, and Russia, who, after initial hesitation, intervened militarily on behalf of the Greeks, a decisive factor that led to the creation of an autonomous Greek kingdom in 1830. [27]

For many enlightened Europeans the national revolutions in the Balkans represented the casting off of oriental and backward Ottoman despotism and the redemption of Christian subjects through national revolution. Coming so soon after the revolutionary transformations in France, the uprisings in Serbia and Greece were seen by many as an example of the kind of universal and progressive revolution that had taken place in France. This was especially true in the case of the Greek revolution, which was understood by many Westerners as a battle of a once great, classical civilization to throw of the shackles of an infidel and primitive imperial master. Thus, for example, George Gordon Byron, Lord Byron (1788-1824) travelled to Greece in order to take part in its struggles, seeing in the War of Independence the poetry of national emancipation and the redemption of Greece’s classical heritage. As the 19 th century progressed, the cadres of national awakeners did indeed internalize the ideals of the French Revolution, and hoped that they would be able to enact them among their own peoples and in their own lands. They also internalized the romance of their own nation’s imagined past, recasting the medieval period as a time of proto-national independence, caricaturing the period of Ottoman rule as centuries-long dark age of vegetation under foreign rule, and pointing towards the redemptive future, at once a new national beginning and a return to lost glories.

The Greek War also established the pattern of Great Power intervention and involvement in Ottoman affairs and therefore, also, of Great Power involvement in the Balkan national revolutionary movements, which would continue until 1914. For this reason the national revolutions in the Ottoman Balkans were inextricably linked to the foreign policy interests of the Great Powers: they could be made and unmade through the sponsorship and support of one or more of the Great Powers. Thus, Andrew Rossos points out that Macedonia’s “non-emergence” as a national state has less to do with a lack of Macedonian national identity and a Macedonian national movement than it does with the absence of powerful foreign support of the kind enjoyed by, for example, Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece, during the period in question. [28] To be sure, the development/non-development of nationalism in the Ottoman Balkans owed much to local and situational factors, as historians such as Isa Blumi have argued, [29] but, as the Treaty of Berlin and the subsequent creation of an Albanian state in 1912 demonstrated, the Great Powers still had enormous sway over the borders and even the existence of the Balkan national states.

The confluence of foreign, Great Power interests and native revolution can be seen during an uprising of Christian peasants in Ottoman Bosnia which quickly spread to Serbia and Bulgaria, becoming a matter of international concern and foreign intervention when Russia declared war on the Ottomans in 1877. [30] Western leaders expressed concern at the violence of the Ottoman army’s reprisals on its Christian subjects, just as they had done during the Greek War of Independence. [31] The Great Powers’ concerns in the Balkans were not exclusively humanitarian however: the deep involvement of Russia in the military and political aspects of the Eastern Question raised the issue of competing Great Power interests in the Balkans. So too did the initial Russian-sponsored settlement, the “Treaty of San Stefano” (March 1878), which created a large Bulgarian national state, a powerful regional client for Russian interests. But the remaining Great Powers arranged for the hasty revision of San Stefano with the “Treaty of Berlin” (July 1878), a settlement intended to undo many of Russia’s gains from the previous treaty, and to create a greater balance between the interests of the Great Powers in the region. The significance of the Treaty of Berlin is great and varied: the settlement was, in a sense, a blueprint for the settlements that would decide the borders in central and Eastern Europe after the First World War. They established the nation-state as the principle of post-Ottoman political organization in the region, just as the Paris peace treaties at the end of the First World War established nation-states as the principle of post-Habsburg political organization. They also enhanced the rivalries of the Balkan states themselves, creating overlapping territorial claims and the tantalizing prospect that still more gains at the expense of the Ottoman Empire would be tolerated and perhaps even encouraged. Serbian, Greek and Bulgarian nationalists all coveted Ottoman lands in Macedonia and Thrace, and each now attempted to stake a claim on these lands through the promotion of cultural work, including the establishment of churches and schools , and so on. The revision of Bulgaria’s borders established a ready-made programme of irredentism that would shape the political culture and foreign policy of the Bulgarian state all the way up to the First World War, and even beyond.

Towards Sarajevo ↑

We have already seen that the ascendant forces of nationalism in the second half of the 19 th century called into question the very fundamentals of the Austrian and Ottoman Empires, namely, the dynastic principle and the possibility of a state being able to contain numerous national groups within a single imperial framework. The decline of the Ottoman Empire as a force to be feared and reckoned with in Europe also meant the loss of the Habsburg Empire’s importance as an Antemurale Christianitatis; whilst the unification of Germany and its emergence of as a front-rank power in Europe relegated the monarchy to an even lower position in the hierarchy of the Great Powers. Austria-Hungary faced an additional problem with the establishment of an independent Serbian national state on its borders, since this risked inflaming nationalist sentiment among the monarchy’s large South Slav population.

This population, in fact, had expanded in the aftermath of the Bosnian uprising and the Treaty of Berlin. The settlement of 1878 had called for the occupation of Bosnia-Hercegovina (as it became known after the Berlin Treaty), still de jure a province of the Ottoman Empire, by Austria-Hungary. After the Austro-Hungarian army waged a costly military campaign to bring the region under imperial control, the monarchy set out its long-term occupation goals in Bosnia. Its chief concerns were the rising tides of Croatian, and (especially) Serbian nationalist sentiment, among the Catholic and Orthodox Christian populations within Bosnia, which would compete with imperial attempts to win the loyalty of the population. The monarchy’s solution to this problem was to attempt to construct and promote a Bosnian “national identity”, chiefly among the province’s Slavic Muslim population, as a means of securing the province and its population to the remainder of the monarchy. This, in fact, was an attempt to synthesize nationalist forces with imperial interests. Bosnia, then, served as a kind of laboratory wherein the Habsburgs could experiment with the process of “taming Balkan nationalism” (and perhaps taming nationalism more generally) so that it could co-exist and even strengthen the monarchy itself. [32]

Another prong of Austria-Hungary’s policies towards the Eastern Question was a diplomatic alliance with the new Kingdom of Serbia and its ruling dynasty, the Obrenovićs, according to which the Serbs would abandon territorial claims in Bosnia in favor of those in the Ottoman Balkans (principally in Macedonia). This suited the ruling houses of both states (although certain militarist and nationalist societies within Serbia sought a more belligerent line in Bosnia), but the arrangement ended soon after a military coup in Serbia in 1903 deposed the autocratic Alexander Obrenović, King of Serbia (1876-1903) , who was replaced by the exiled claimant Petar Karadjordjević (1844-1921) . [33] This change of guard in Belgrade ushered in a more aggressive stance within Serbia towards its unredeemed territories, and also a change in the foreign policy alignment of the Balkan kingdom, away from the tutelage of Austria-Hungary and towards that of Russia. This, in turn, introduced new tensions into the Eastern Question, as now Austria-Hungary was faced with a potentially antagonistic neighbour with designs on imperial territories in Bosnia, and which enjoyed the support of Russia, a great rival to Austro-Hungarian interests in the region. The years after 1903 are marked by a series of confrontations between Austria-Hungary and Serbia, the most serious of which came following Austria-Hungary’s decision to annex outright occupied Bosnia (1908). [34] For many Serbs, Austria-Hungary’s annexation rudely disabused any notions that the occupation of Bosnia was a temporary measure that might be rescinded should the winds of international diplomacy change. The monarchy’s possession of these lands now seemed like a permanent arrangement, a fait accompli . In fact, after some initial bluster, the Serbian government pragmatically accepted the new realities to the west of the country and decided instead to pursue with greater vigour the “unredeemed” Ottoman lands to the south. The same could not be said of the militarist and nationalist societies in Serbia, many of which were inspired by Mazzini’s Young Italy, and many of which saw the annexation as a terrible affront to the national dignity of the Serbian state. [35]

The cycle of conflict which led to the First World War began in the Ottoman Balkans in 1912 following the formation of a shaky military alliance of the Balkan states (Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro , the so-called “Balkan League”) directing against the Ottoman Empire. This empire was significantly weakened following its defeat by Italy in Tripoli, for the purpose of “liberating” the Christian Balkans from imperial rule. [36] The rapid successes of the Balkan League soon exposed the absence of common interests between the states, aside from a mutual desire to expel the Ottoman Empire from Europe. With this largely achieved, pre-existing rivalries between the Balkan states once again came to the fore. A particularly severe dispute soon opened up between Serbia and Bulgaria over which country was entitled to territories in Macedonia that were claimed by both states. The dispute showed how inter-communal rivalries, that is, rivalries between the Christian Balkan states themselves, were just as important on the eve of the First World War as were rivalries between nation-states and empire. Bulgaria experienced its first “national catastrophe” in the summer of 1913 when it attacked Serbian positions in Macedonia and its armies were quickly routed by a combined force of Serbian, Montenegrin, Greek, Romanian and even Ottoman armies, a defeat which lost Bulgaria almost all its Macedonian territory to Serbia. Serbia, on the other hand, emerged from the two Balkan wars greatly expanded, almost doubling the size of its territory and leaving only Habsburg Bosnia among the its un-redeemed territories. The political leaders of Serbia, their state replete in victory and their army spent on the battlefield, would have looked forward to a period of consolidation and preparation for future expansion. However, such patience was not a characteristic of certain militarist and youth groups in the South Slav lands. The fruits of their collaborations fell in Sarajevo, June 1914, and with consequences felt by the entire world.

Conclusion ↑

There can be no doubt that nationalism was a potent political force in 19 th century Europe: a means of mass mobilization embraced by many millions of people; an ideology of transformation and revolution born in the French Revolution, intrinsically linked to the rapid modernization of the continent, whose spread threatened to alter the political, social, and cultural landscape of Europe. The political map of Europe in the 21 st century has changed, but it is not beyond recognition when held alongside the political map of 1918. The Europe that emerged from the First World War was utterly unlike that of 1815. Everywhere changes were wrought by the forces of nationalism: the unifications of Germany and Italy and the rise of national-states in the Balkans are prime examples of this. So it is quite right that we recognize in nationalism an historical agent of great force and consequence. It is also right, however, that we acknowledge the role played by contingency and accident in its rise. After all, the political map of Europe in 1918 was also very different from that of 1914: the War itself effected the many of the most momentous changes to Europe’s political landscape, especially in eastern and central Europe. The reforms within Austria-Hungary, the compromise with the Hungarians and the occupation of Bosnia, demonstrate that nationalism and imperialism were perhaps, after all, not irreconcilable forces. The political sphere of Europe in the 19 th century was a contested space, and in the early 20 th century, nationalism and the nation-state were the almost undisputed victors of this contest. It has been the intention of this article to show that its victory was far from inevitable.

John Paul Newman, National University of Ireland, Maynooth

Section Editors: Annika Mombauer ; William Mulligan

- ↑ Jaszi, Oscar: The Dissolution of the Habsburg Monarchy, Chicago 1929. The inevitability of the decline of the monarchy is challenged in Sked, Alan: The Decline and Fall of the Habsburg Empire, 1815-1918, London 1989 and in Okey, Robin: The Habsburg Monarch c. 1765-1918, New York 2001.

- ↑ See, e.g., Lewis, Bernard: The Emergence of Modern Turkey, New York/Oxford 2002.

- ↑ The father of the modernist interpretation of nationalism is Ernest Gellner (1925-1995) . See his Nations and Nationalism, Ithaca 1983. For this approach, see also Anderson, Benedict: Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, London/New York 1991; Giddens, Anthony: The Consequences of Modernity, Stanford 1990; Hobsbawm, Eric: Nations and Nationalism since 1870, Cambridge/New York 1992. For a useful overview on the various theories and debates in the study of nationalism, see Lawrence, Paul: Nationalism, History and Theory, London 2005. For a brief summary of nationalism debates see Lawrence, Paul: Nationalism. History and Theory, London 2005.

- ↑ See Anderson, Imagine Communities 1991.

- ↑ Weber, Eugen: Peasants into Frenchmen: the Modernization of Rural France, 1870-1914, Stanford 1976.

- ↑ Hroch, Miroslav: Social Preconditions of National Revival in Europe. a Comparative Analysis of the Social Composition of Patriotic Groups among the Smaller European Nations, Cambridge/New York 1985.

- ↑ For an historical survey of these areas, see Armour, Ian: A History of Eastern Europe, 1740-1918, London 2006.

- ↑ See, ee.g, Smith, Anthony: Myths and Memories of Nation, Oxford 1999.

- ↑ On the role of myth and memory in the formation of Balkan national identity, see Todorova, Maria: Balkan Identities: Nation and Memory, New York 2004; and in the Bulgarian context, Todorova, Maria: Bones of Contention. The Living Archive of Vasil Levski and the Making of a Modern National Hero, Budapest/New York 2009.

- ↑ Cited in Sugar, Peter F.: “External and Domestic Roots of Eastern European Nationalism, in: Sugar, Peter F./Lederer, Ivo John (eds.): Nationalism in Eastern Europe, Seattle 1994, p. 38.

- ↑ Snyder, Timothy: The Reconstruction of Nations. Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569-1999, New Haven 2003.

- ↑ On this period, see Krüger, Peter/Schroeder, Paul W.: The Transformation of European Politics, 1763-1848. Episode or Model in Modern History, New York 2002.

- ↑ See Taylor, A.J.P.: The Struggle for Mastery in Europe, 1848-1918, Oxford 1954, pp. 1-3.

- ↑ Kann, Robert A.: A History of the Habsburg Empire, 1526-1918, Berkeley 1974, p. 283.

- ↑ Taylor, A.J.P.: The Habsburg Monarchy, 1809-1918, London 1990, p. 49.

- ↑ Judson, Pieter M.: Guardians of the Nation. Activists on the Language Frontiers of Imperial Austria, Cambrdige, MA 2006. See also Zahra, Tara: Kidnapped Souls. National Indifference and the Battle for Children in the Bohemian Lands, 1900-1948, Ithaca 2008.

- ↑ On the revolutions of 1848-1849, see Pogge von Strandmann, H./ Evans, Robert John Weston: The Revolutions in Europe, 1848-1849. From Reform to Reaction, Oxford/New York 2000; Sperber, Jonathan: The European Revolutions, 1848-1851, Cambridge 2005.

- ↑ See Deák, István: The Lawful Revolution: Louis Kossuth and the Hungarians, 1848-1849, New York 1979.

- ↑ Snyder, Timothy: The Red Prince, The Secret Lives of a Habsburg Archduke, New York 2008.

- ↑ “Risorgimento”, from the Italian risorgere means “to rise again”, a term that implied the rebirth of a primordial and pre-existing national identity and state.

- ↑ On the history of the Risorgimento, see Riall, Lucy: The Italian Risorgimento: State, Society, and National Unification, London/New York 1994.

- ↑ Davies, Norman: The Heart of Europe: The Past in Poland’s Present, Oxford 2001, p. 150.

- ↑ See Dedijer, Vladimir: The Road to Sarajevo, New York 1966.

- ↑ On Prussia throughout history, see Clark, Christopher: Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947, London 2007.

- ↑ See Showalter, Dennis: The Wars of German Unification, London 2004.

- ↑ See Sugar, Peter: Southeastern Europe under Ottoman rule, 1354-1804, Seattle 1977.

- ↑ On the Serbian and Greek revolutions, see Jelavich, Charles/Jelavich, Barbara: The Establishment of the Balkan National States, Seattle 2000, pp. 26-52.

- ↑ Rossos, Andrew: Macedonia and the Macedonians. A History, Stanford 2008.

- ↑ Blumi, Isa: Reinstating the Balkans: Alternative Balkan Modernities 1800-1912, New York 2011.

- ↑ On this critical juncture in Balkan history, see: Jelavich and Jelavich, The Establishment of the Balkan National States 2000, pp. 141-157.

- ↑ A notable example is the British Liberal politician William Gladstone’s (1809-1898) influential pamphlet The Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East, published in 1876.

- ↑ On the Habsburg occupation of Bosnia, see the detailed study by Okey, Robin: Taming Balkan Nationalism. The Habsburg ‘Civilizing Mission’ in Bosnia, 1878-1914, Oxford/New York 2007.

- ↑ On the coup and its aftermath, see Vucinich, Wayne: Serbia between East and West. The Events of 1903-1908, Stanford 1954.

- ↑ The classic work on the annexation crisis is Schmitt, Bernadotte: The Annexation of Bosnia, 1908-1909, Cambridge 1937. See also Malcolm, Noel: Bosnia: A Short History, New York 1994; and Okey, Robin: Taming Balkan Nationalism 2007.

- ↑ The controversy about the relationship between Serbian militarist associations and the Serbian government continues into the present-day, as shown by the response to Christopher Clark’s important new work on the Balkan origins of the First World War, The Sleepwalkers: How Europe went to War in 1914, New York 2013.

- ↑ For a useful military history of the Balkan Wars, see Hall, Richard C.: The Balkan Wars, 1912-1913. Prelude to the First World War, London/New York 2000.

- Armour, Ian D.: A history of Eastern Europe 1740-1918 , London; New York 2006: Hodder Arnold; Oxford University Press.

- Blumi, Isa: Reinstating the Ottomans. Alternative Balkan modernities, 1800-1912 , New York 2011: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Clark, Christopher M.: The sleepwalkers. How Europe went to war in 1914 , New York 2013: Harper.

- Gellner, Ernest: Nations and nationalism , Ithaca 1983: Cornell University Press.

- Hroch, Miroslav: Social preconditions of national revival in Europe. A comparative analysis of the social composition of patriotic groups among the smaller European nations , Cambridge; New York 1985: Cambridge University Press.

- Jelavich, Charles / Jelavich, Barbara: The establishment of the Balkan national states, 1804-1920 , Seattle 1977: University of Washington Press.

- Judson, Pieter M.: Guardians of the nation. Activists on the language frontiers of imperial Austria , Cambridge 2006: Harvard University Press.

- Lewis, Bernard: The emergence of modern Turkey , London, New York 1961: Oxford University Press.

- Okey, Robin: The Habsburg monarchy c.1765-1918. From enlightenment to eclipse , Basingstoke 2001: Macmillan.

- Riall, Lucy: The Italian Risorgimento. State, society and national unification , London 1994: Routledge.

- Showalter, Dennis: The wars of German unification , London; New York 2004: Arnold; Oxford University Press.

- Sked, Alan: The decline and fall of the Habsburg Empire, 1815-1918 , London; New York 1989: Longman.

- Smith, Anthony David: Myths and memories of the nation , Oxford 2009: Oxford University Press.

- Snyder, Timothy: The reconstruction of nations. Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569-1999 , New Haven; London 2004: Yale University Press.

- Sperber, Jonathan: The European revolutions, 1848-1851 , Cambridge; New York 1994: Cambridge University Press.

- Weber, Eugen: Peasants into Frenchmen. The modernization of rural France, 1870-1914 , Stanford 1976: Stanford University Press.

Newman, John Paul: Nationalism , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2014-10-08. DOI : 10.15463/ie1418.10222 .

This text is licensed under: CC by-NC-ND 3.0 Germany - Attribution, Non-commercial, No Derivative Works.

Related Articles

External links.

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

The History Hit Miscellany of Facts, Figures and Fascinating Finds

- 20th Century

The 4 M-A-I-N Causes of World War One

Alex Browne

28 sep 2021.

It’s possibly the single most pondered question in history – what caused World War One? It wasn’t, like in World War Two, a case of a single belligerent pushing others to take a military stand. It didn’t have the moral vindication of resisting a tyrant.

Rather, a delicate but toxic balance of structural forces created a dry tinder that was lit by the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo . That event precipitated the July Crisis, which saw the major European powers hurtle toward open conflict.

The M-A-I-N acronym – militarism, alliances, imperialism and nationalism – is often used to analyse the war, and each of these reasons are cited to be the 4 main causes of World War One. It’s simplistic but provides a useful framework.

The late nineteenth century was an era of military competition, particularly between the major European powers. The policy of building a stronger military was judged relative to neighbours, creating a culture of paranoia that heightened the search for alliances. It was fed by the cultural belief that war is good for nations.

Germany in particular looked to expand its navy. However, the ‘naval race’ was never a real contest – the British always s maintained naval superiority. But the British obsession with naval dominance was strong. Government rhetoric exaggerated military expansionism. A simple naivety in the potential scale and bloodshed of a European war prevented several governments from checking their aggression.

A web of alliances developed in Europe between 1870 and 1914 , effectively creating two camps bound by commitments to maintain sovereignty or intervene militarily – the Triple Entente and the Triple Alliance.

- The Triple Alliance of 1882 linked Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy.

- The Triple Entente of 1907 linked France, Britain and Russia.

A historic point of conflict between Austria Hungary and Russia was over their incompatible Balkan interests, and France had a deep suspicion of Germany rooted in their defeat in the 1870 war.

The alliance system primarily came about because after 1870 Germany, under Bismarck, set a precedent by playing its neighbours’ imperial endeavours off one another, in order to maintain a balance of power within Europe

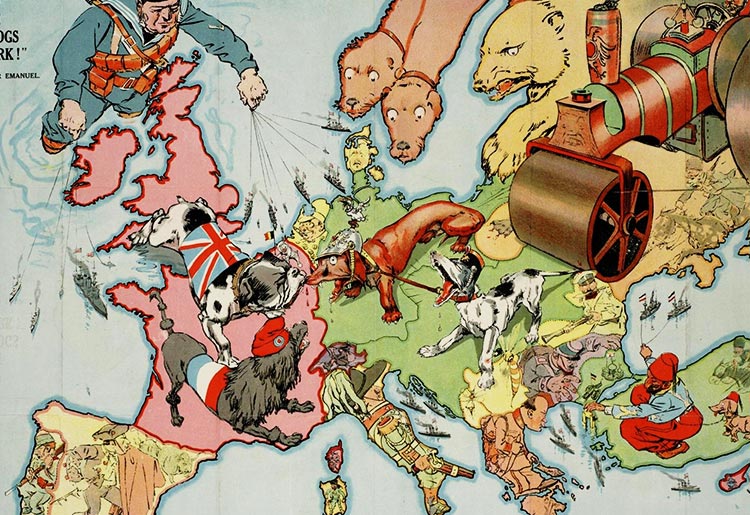

‘Hark! hark! the dogs do bark!’, satirical map of Europe. 1914

Image Credit: Paul K, CC BY 2.0 , via Wikimedia Commons

Imperialism

Imperial competition also pushed the countries towards adopting alliances. Colonies were units of exchange that could be bargained without significantly affecting the metro-pole. They also brought nations who would otherwise not interact into conflict and agreement. For example, the Russo-Japanese War (1905) over aspirations in China, helped bring the Triple Entente into being.

It has been suggested that Germany was motivated by imperial ambitions to invade Belgium and France. Certainly the expansion of the British and French empires, fired by the rise of industrialism and the pursuit of new markets, caused some resentment in Germany, and the pursuit of a short, aborted imperial policy in the late nineteenth century.

However the suggestion that Germany wanted to create a European empire in 1914 is not supported by the pre-war rhetoric and strategy.

Nationalism

Nationalism was also a new and powerful source of tension in Europe. It was tied to militarism, and clashed with the interests of the imperial powers in Europe. Nationalism created new areas of interest over which nations could compete.

For example, The Habsburg empire was tottering agglomeration of 11 different nationalities, with large slavic populations in Galicia and the Balkans whose nationalist aspirations ran counter to imperial cohesion. Nationalism in the Balkan’s also piqued Russia’s historic interest in the region.

Indeed, Serbian nationalism created the trigger cause of the conflict – the assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

The spark: the assassination

Ferdinand and his wife were murdered in Sarajevo by Gavrilo Princip, a member of the Bosnian Serbian nationalist terrorist organization the ‘Black Hand Gang.’ Ferdinand’s death, which was interpreted as a product of official Serbian policy, created the July Crisis – a month of diplomatic and governmental miscalculations that saw a domino effect of war declarations initiated.

The historical dialogue on this issue is vast and distorted by substantial biases. Vague and undefined schemes of reckless expansion were imputed to the German leadership in the immediate aftermath of the war with the ‘war-guilt’ clause. The notion that Germany was bursting with newfound strength, proud of her abilities and eager to showcase them, was overplayed.

The first page of the edition of the ‘Domenica del Corriere’, an Italian paper, with a drawing by Achille Beltrame depicting Gavrilo Princip killing Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in Sarajevo

Image Credit: Achille Beltrame, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The almost laughable rationalization of British imperial power as ‘necessary’ or ‘civilizing’ didn’t translate to German imperialism, which was ‘aggressive’ and ‘expansionist.’ There is an on-going historical discussion on who if anyone was most culpable.

Blame has been directed at every single combatant at one point or another, and some have said that all the major governments considered a golden opportunity for increasing popularity at home.

The Schlieffen plan could be blamed for bringing Britain into the war, the scale of the war could be blamed on Russia as the first big country to mobilise, inherent rivalries between imperialism and capitalism could be blamed for polarising the combatants. AJP Taylor’s ‘timetable theory’ emphasises the delicate, highly complex plans involved in mobilization which prompted ostensibly aggressive military preparations.

Every point has some merit, but in the end what proved most devastating was the combination of an alliance network with the widespread, misguided belief that war is good for nations, and that the best way to fight a modern war was to attack. That the war was inevitable is questionable, but certainly the notion of glorious war, of war as a good for nation-building, was strong pre-1914. By the end of the war, it was dead.

You May Also Like

The Peasants’ Revolt: Rise of the Rebels

10 Myths About Winston Churchill

Medusa: What Was a Gorgon?

10 Facts About the Battle of Shrewsbury

5 of Our Top Podcasts About the Norman Conquest of 1066

How Did 3 People Seemingly Escape From Alcatraz?

5 of Our Top Documentaries About the Norman Conquest of 1066

1848: The Year of Revolutions

What Prompted the Boston Tea Party?

15 Quotes by Nelson Mandela

The History of Advent

The Princes in the Tower: Solving History’s Greatest Cold Case

How Did Nationalism Lead to WW1?

The rising nationalism that was apparent throughout Europe in the early twentieth century is often cited as one of the four longterm causes of World War One; and with its natural links to both militarism and imperialism is considered by many historians to be the single biggest cause.

In this article, we shall attempt to define what nationalism was, in the context of nineteenth and twentieth century Europe, and have a look at how exactly nationalism contributed to the outbreak of World War I.

What is Nationalism?

Nationalism can be defined as a feeling of immense pride in one’s country or in one’s people. It is a fierce form of patriotism and at its most extreme can lead to negative attitudes towards other nations or even feelings of superiority over other peoples.

The Origins of Nationalism in Europe

A likely origin of the wave of nationalism that spread through Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century was the Spring of Nations, in 1848.

The Spring of Nations (also known as the Springtime of the Peoples) consisted of a series of political upheavals, although mostly democratic in nature, which had the aim of removing the old monarchical structures to create independent nation-states.

This national awakening grew out of a cultural revolution of nationhood and a national identity, where the notion of foreign rule began to be resented more and more by those citizens who were governed by a different nationality to their own; and in the thirty years after the Spring of Nations, a total of seven new national states were created within Europe.

Examples of Nationalism Before WW1

Nationalism took many different forms within Europe, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. As well as those nations still seeking their independence, there were also those newly created nations looking to forge a place for themselves on the world stage.

Finally, there was a different type of nationalism, seen in those countries that had enjoyed a sustained period of prosperity and influence, both at home and abroad, and where some nationalists felt a certain superiority over most other countries and peoples.

British Nationalism

By the end of the nineteenth century, Britain had enjoyed two hundred years as the richest and most powerful nation on the planet, with the greatest empire the world had ever seen. Perhaps not surprisingly, a feeling of nationalist pride swept through the country during this time and there were many in the country who believed the British to be superior to all other nations in Europe.

This idea of nationalism was spurred on by the British press, who regularly published satirical cartoons of foreign countries and their monarchs, often depicting them as greedy, arrogant or lazy.

A particularly dangerous form of popular press in Britain, towards the end of the century, was the Invasion genre of literature, which scared their readers into believing that the enemy was just about to invade this Sceptred Isle. As well as fuelling the flames of militarism in the country, these serialised novellas depicted foreign nations such as Germany and France in the worst possible light.

Pan-Germanism

Nationalism and xenophobia were just as rife in Germany, although the root of this patriotism was not from centuries of world dominance, but rather the overzealous optimism of a new nation-state.

In order to consolidate the newly unified Germany and strengthen the national identity of the German people, the government employed various strategies to help create a nationalist sentiment.

Pan-Germanism sought to unify all of the German-speaking people in Europe, and was very successful in building a German national identity. Unfortunately, Pan-Germanism at its most extreme, such as the Pan-German League, which was founded in 1891, led to openly ethnocentric and racist ideologies, which would really come to the fore in the nineteen thirties and forties, with diabolical consequences.

German nationalism in the late nineteenth century was also intrinsically linked with German militarism—it was believed that the strength of the nation was mirrored by the strength of its military. And when the young and ambitious Wilhelm II became Kaiser, in 1888, he became the epitome of a nationalistic and militaristic Germany.

The Kaiser’s policy of Weltpolitik, the aim of which was to transform Germany into a global power, led the country to be envious of the other more established empires, especially that of Great Britain. As a result, Britain became a target for the German press, where she was portrayed as selfish and greedy, thus encouraging anti-British sentiments throughout the country.

Austro-Slavism

A very different type of nationalism emerged within Central Europe during the middle of the nineteenth century. Austro-Slavism was a political concept that originated within the Czech lands, which sought to solve the problems that the Slavs faced with the Habsburg Monarchy at that time.

Seen as a more peaceful alternative to the concept of pan-Slavism, the policy of Austro-Slavism proposed a federation of eight national regions, with a degree of self-rule. Austro-Slavism gained support from Slovaks, Slovenes, Croats and Poles, but was ultimately dismissed following the formation of Austria-Hungary, in 1867, which honoured Hungarian demands, but not Slavic ones.

The political concept of Austro-Slavism helped lay the foundations for the The First Czechoslovak Republic, in 1918, following the end of World War One and the collapse of Austria-Hungary.

Pan-Slavism

The roots of Pan-Slavism were similar to Pan-Germanism in that they originated from the nationalism of an ethnic group who wished to unite—in this case the Slavic people.

Again originating in the Czech lands, Pan-Slavism was especially embraced by the Slovak people, following the creation of Austria-Hungrary, when it became clear the preferred concept of Austro-Slavism was not going to be accepted by Austrian Emperor, Franz Jozeph I.

Ľudovít Štúr, who codified the first official Slovak language, wrote in his book, Slavdom and the World of the Future , that Austro-Slavism was no longer possible and he looked towards Russia, the only Slavic nation-state, to one day annexe the land of the Slovaks.

Pan-Slavism also had some supporters amongst the Czech and Slovak politicians, especially the nationalistic and far-right parties.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, Pan-Slavism had become especially popular amongst South Slavs, who often looked towards Russia for support. Here, the Pan-Slavism movement sought Slavs from both the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Ottoman Empire to unite together.

The notion of a united nation of Southern Slavs was particular strong within the newly independent country of Serbia, who eventually sought to create a South Slav (Yugoslav) nation-state.

The link between nationalism and WW1 is arguably the strongest of the 4 main longterm causes of World War One. But even then, certainly for the major European powers, nationalism was intrinsically linked with two of the other causes—imperialism and militarism. Meanwhile, the sense of nationalism for many of the smaller European countries, can be strongly linked to independence and self-rule.

Nationalism Linked to Imperialism

The link between nationalism and imperialism was twofold. While nationalists would take great pride from their nation’s empire building, they were also quick to condemn the other European powers as being greedy, cruel and insensitive for their imperial aspirations.

Meanwhile, imperialism had probably given the major powers a false idea of what war was really about. Apart from the Crimean War and the Franco-Prussian war, there had not really been a major conflict between two of the European powers for almost a century.

With the exception of France, none of the major powers had experienced defeat in the half century prior to WW1; and victories against less equipped armies in Africa and Asia had no doubt led to a naive overconfidence in each nation’s ability to win a war in Europe.

Nationalism Linked to Militarism

Another of the effects of the growing nationalism in Europe was an inflated confidence in one’s nation when it came to the country’s military power.

In the decades leading up to the First World War, there had been a strong link between nationalism and militarism, where the citizens of many European nations felt immense pride in how strong and powerful their country was in military terms.

This led to governments being pressured by their peoples and the popular press to build more and more battleships, stockpile more and more weapons and enlist more and more men, so as to whet this patriotic appetite running through the nation of needing to be the most powerful—not only to defend the country from would-be aggressors, but also as a source of national pride.

Such was this military fervour amongst the populace that by the time 1914 came around, and Europe found itself on the brink of war, many of the major European powers had almost a feeling of invincibility about them, completely certain in the belief that their nation could not possibly lose a war.

Nationalism Linked to Independence

While there was obviously no link between nationalism and imperialism or militarism for the smaller nations in Europe, there was a link to something that was perhaps more worth fighting for—namely, a national identity and for many, independence and self-rule.

Following the Spring of Nations, in 1848, more and more nations in Europe won their independence and became nation-states, including Germany, Italy, Serbia and Bulgaria.

However, by 1914, there were still many more nations with ambitions of self-rule on the continent, especially within Austria-Hungary.

In particular, this awakening of a national identity was causing tensions in the Balkans, where things were just about to come to a head.

Nationalism in WW1

There is no doubting the strong nationalistic feelings of patriotic citizens throughout Europe, which were also evident once the war had started as well. An example of nationalism in WW1 would be the numbers of young men in Britain from all classes, who clamoured to volunteer for king and country at the beginning of the war.

Of course, it was a different time when honour and doing one’s duty was still very much a thing, but nonetheless there is no doubt that WW1 nationalism also played its part.

It is much easier to recruit an army of patriotic men, who are convinced they are fighting for the right cause and who believe they are going to fight in a war, which they can’t lose.

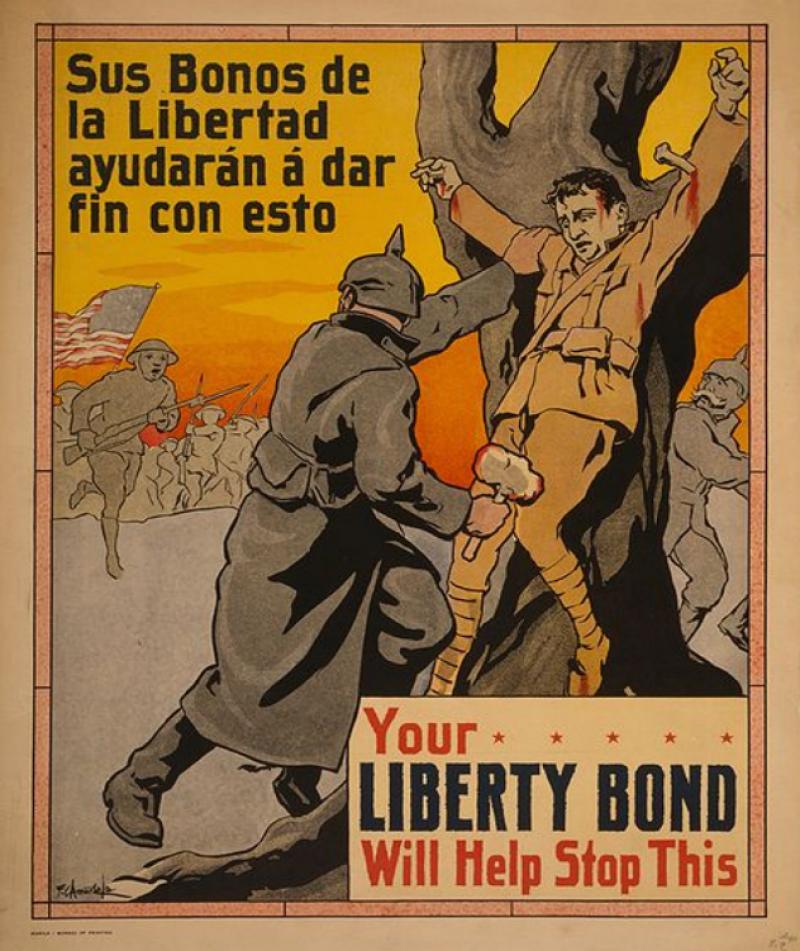

When the reality of war began to set in, however, and it became harder and harder to attract new recruits, the government turned to different methods to pull on the nationalistic heart strings of the British people.

Propaganda posters painted the enemy as almost subhuman, who had committed unspeakable war crimes against our innocent allies—an evil that only Britain could defeat.

Other examples of nationalism in WW1 involved those patriotic citizens back home, who although were not directly involved in the fighting, were still needed by their country to win the war.

Older men and especially women fought the good fight at home, working in factories to help arm and supply the young lions; and even children and the elderly played their part by foregoing certain foodstuffs and other creature comforts, so that the men at the front had everything they needed to defeat the enemy.

Everything considered, nationalism was arguably the strongest of the four main causes of WW1 , especially considering its links with two of the other main causes, militarism and imperialism. However, it is important to note that as well as the so-called M.A.I.N Causes of World War One, there were also a number of immediate causes, without which the Great War of 1914 may very well have not taken place at all.

Why not check out 4 M.A.I.N. Causes of WW1: NATIONALISM – PowerPoint Lesson with Speaker Notes

Test Your Knowledge with our FREE WebQuest

Now it’s time to test your knowledge of Nationalism as well as the other M.A.I.N. Causes of WW1.

4 M.A.I.N. Causes of WW1

The 4 M.A.I.N. Causes of WW1 WebQuest (Student Version) – This 5 page teaching resource consists of a webquest that covers the four main longterm causes of World War One.

The webquest comprises of 5 worksheets, which contain 24 questions, as well as 4 jigsaw puzzles (with secret watermarks) and an online quiz (requiring a pass of 70% to reveal a secret phrase).

Ohio State nav bar

Ohio state navigation bar.

- BuckeyeLink

- Search Ohio State

Why did they fight? Understanding Nationalism, Imperialism and Militarism during World War I

Lesson Plan

Duration: , summary/objective: , benchmarks:.

P.I.S. A; S.S.S.M. A

Materials needed:

Introduction: (day 1) .

- After explaining the causes of World War I, present students with national scenario “What would you do” (handout here and text in “Causes of WWI” powerpoint presentation). File Causes of WWI PowerPoint File 1.29 MB

- Have students answer this question as a journal entry and discuss answers. Would you go to war? Why? Why not? What country do you think this represents?