- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Uvalde elementary school shooting

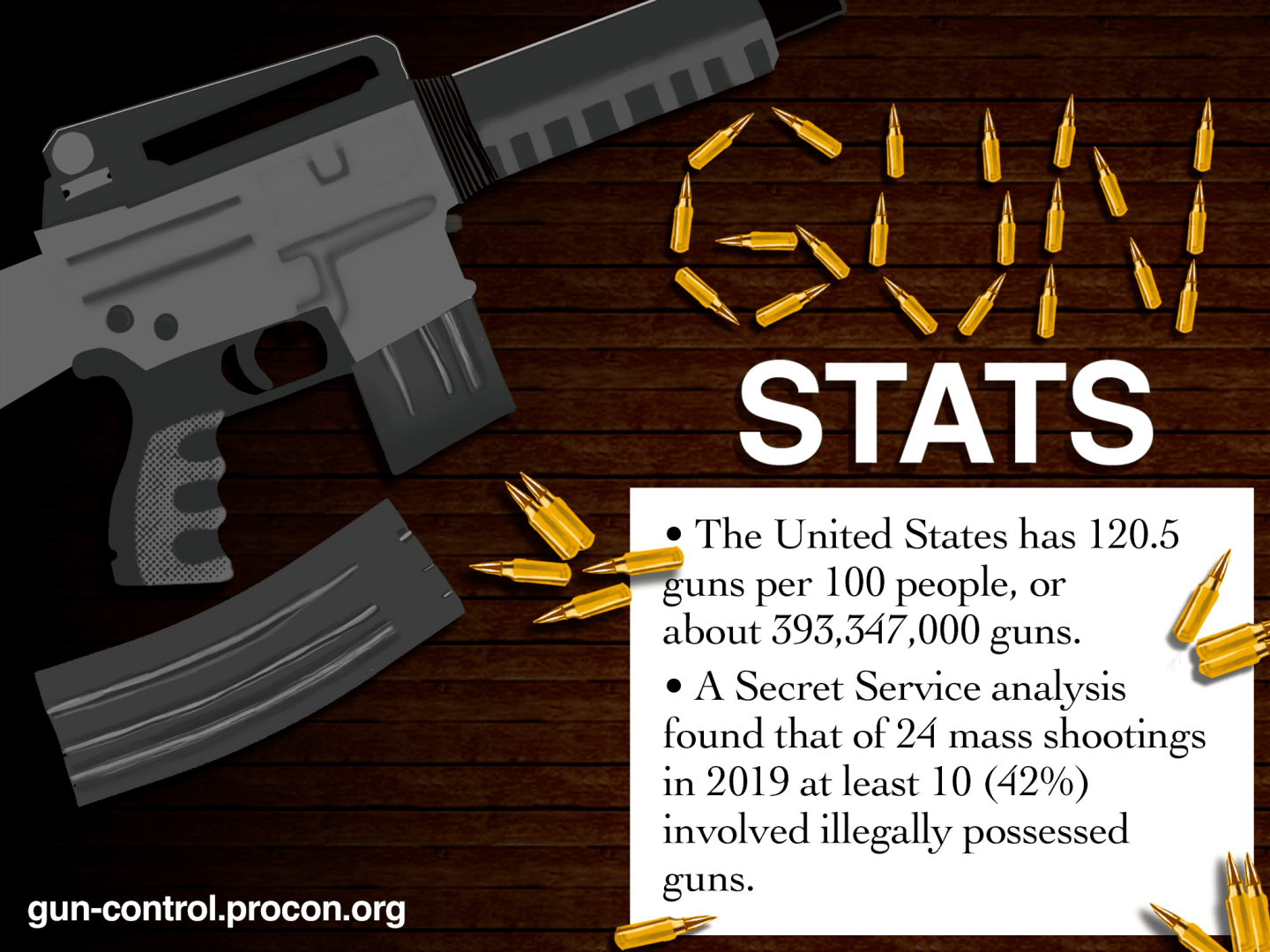

12 stats to help inform the gun control debate.

Britt Cheng

Gun control advocates hold signs during a protest at Discovery Green across from the National Rifle Association Annual Meeting at the George R. Brown Convention Center on Friday in Houston, Texas. Eric Thayer/Getty Images hide caption

Gun control advocates hold signs during a protest at Discovery Green across from the National Rifle Association Annual Meeting at the George R. Brown Convention Center on Friday in Houston, Texas.

The nationwide gun control debate resurfaced on Tuesday, after an 18-year-old shooter entered Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, and killed 19 students and two adults in the second deadliest school shooting in U.S. history . The mass shooting came just 10 days after another 18-year-old gunman opened fire at a Buffalo, N.Y. grocery store , killing 10 people and injuring three others.

In the aftermath, prominent voices have urged Congress to pass gun control laws and universal background checks, from Sen. Chris Murphy , who represents Connecticut where the Sandy Hook school shooting happened, to NBA coach Steve Kerr to the Pope . Meanwhile, some Republican lawmakers said they won't back laws that limit gun rights.

The evolving narrative of what happened in the Uvalde shooting

While the push for accountability intensifies as details emerge from what happened in the hour after police officers arrived at the shooting up until they killed the gunman, let's look at these statistics that help inform the gun control debate in the United States.

Number of people killed by guns in the U.S., every day

Number of children who die every day from gun violence in the U.S.

School shootings since Sandy Hook , including 27 school shootings so far this year.

Peak ages for violent offending with firearms

Number of AR-15s and its variations in circulation

Number of people who will die after attempting suicide with a gun

Percentage of mass shooters who are men

Percentage of gun owners who favor preventing the "mentally ill" from purchasing guns

Percentage of gun owners who favor background checks at private sales and gun shows

Percentage of gun deaths that are suicides; 43% are murders

Percentage of murders that involved a firearm

Percentage of people who defended themselves with their guns in violent crimes

Did you know we tell audio stories, too? Listen to our podcasts like No Compromise, our Pulitzer-prize winning investigation into the gun rights debate, on Apple Podcasts and Spotify .

Op-Ed: 5 arguments against gun control — and why they are all wrong

- Show more sharing options

- Copy Link URL Copied!

The National Rifle Association and its allies have their post-shooting routine down cold. They wait a day or two and then respond with a blistering array of attacks against gun-safety advocates calling for reform. No matter what the circumstances — a husband and wife at a Christmas party, a deranged teenager at a movie theater, or a sniper targeting police officers at a peaceful demonstration — they make the same points, which, unsurprisingly, often appear detached from the realities on the ground. After the attack at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Fla., they marshaled five common pro-gun arguments, all of which crumble under scrutiny:

A good guy with a gun would have stopped it

In discussing Orlando, Donald Trump, the presumptive Republican nominee, mused, “If you had guns on the other side, you wouldn’t have had the tragedy that you had.” It was a clear homage to the NRA’s mantra that the “only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.”

In this instance, however, we don’t have to ponder how different the outcome would have been had a “good guy with a gun” been present at Pulse, as there was one : a police officer working extra duty. Despite being armed and even exchanging gunfire with the shooter, the officer was unable to prevent him from gaining entrance to the club.

Most armed citizens fare worse than their police counterparts. In an independent study commissioned by the National Gun Victims Action Council, researchers put 77 participants with varying levels of firearms training through three realistic self-defense scenarios. In the first, seven of the participants shot an innocent bystander. Almost all of the participants in the first and second scenarios who engaged the “bad guy” were killed. And in the final scenario, 23% of the participants fired at a suspect who didn’t actually pose a threat.

Overwhelming empirical evidence corroborates the simulation. Of the 160 active shooting incidents identified by the FBI from 2000 to 2013, only one was stopped by an armed civilian. In comparison, two were stopped by off-duty police, four by armed guards and 21 by unarmed civilians.

Shooters target gun-free zones

Even before most of the details about the Orlando shooting were released, John Lott , a pro-gun commentator, already was proclaiming the dangers of so called “gun-free zones.” Lott argued that “the police only arrived on the scene after the attack occurred.” He also claimed, “Since at least 1950, only slightly over 1% of mass public shootings have occurred where general citizens have been able to defend themselves.” He concluded: “It is hard to ignore how these mass public shooters consciously pick targets where they know victims won’t be able to defend themselves.”

All of this is demonstrably false. There was an armed police officer at Pulse, and he was very quickly joined by two fellow officers. Lott consistently mislabels many of the targets he studies as gun-free zones, ranging from Umpqua Community College in Oregon to Hialeah, Fla., and many others . Further, if we examine the 33 mass public shootings in which four or more people were killed between January 2009 and June 2014, the evidence reveals that 18 occurred in areas where guns were not banned or had armed security present.

The clear pattern that emerges from these incidents is that shooters have a personal connection to their target locations — some grudge against them, no matter how misguided. And when shooters choose a place at random, there is no substantive evidence that they gravitate specifically to gun-free zones. The Aurora, Colo., shooter, for example, left a diary spelling out his motivations and plans for the attack, in which he appeared far more concerned about finding a good parking spot than facing resistance. And in Orlando, the shooter clearly knew he was going to face armed resistance as he was a regular customer of Pulse and even tried to purchase body armor with his firearms.

No laws could have prevented the tragedy

Sounding another familiar theme, conservative writer David French opined after Orlando: “The gun-control debate is nothing more than a destructive distraction” and asked rhetorically, “Is there a single viable gun-control proposal of the last decade that would keep a committed jihadist from arming himself?”

In the case of Orlando, the answer is a clear “yes.” In Canada , the gunman could not have obtained a license to purchase a firearm because of his history of domestic violence , signs of mental instability and vocal support for terrorist organizations. If gun-shop owners had to notify the FBI when somebody on or previously on one of the terror watch lists purchased a weapon, agents could have investigated and perhaps prevented the attack. And if there were restrictions on magazine size, the shooter would have had to reload more frequently, which would have given clubgoers a better opportunity to escape or disarm the assailant, mitigating the carnage.

Terrorists and criminals aren’t deterred by laws

The NRA’s first public response to the Orlando shooting was an op-ed by Executive Director Chris Cox, in which he stated: “Radical Islamic terrorists are not deterred by gun control laws.” This is the newest iteration of the popular talking point that gun laws cannot work because criminals won’t follow them. As Marco Rubio often proclaimed during the primary campaign: “My skepticism about gun laws is criminals don’t follow the law.”

Applying this logic, why have any laws? If criminals are just going to run red lights, why have traffic penalties? The NRA’s reasoning is a prescription for chaos — and it doesn’t withstand contact with empirical reality.

There’s clear evidence that laws do influence criminal behavior.

Whatever Rubio believes, there’s clear evidence that laws do influence criminal behavior . One study , for instance, found that over the past two decades, terrorists in the U.S. have largely abandoned bombs. Why? One reason is that in the aftermath of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, federal legislation made it more difficult for consumers to obtain bomb-making ingredients and easier for law enforcement to monitor purchases. This new oversight led terrorists to revamp their tactics, replacing bombs with guns. An investigation by the Trace revealed that 95% of terrorism deaths in the U.S. between January 2002 and August 2015 were caused by firearms.

Guns are just a tool, like knives and hammers

In response to the Orlando shooting, Philip Van Cleave, leader of the Virginia Citizens Defense League, said: “Blame the bad guy, not the tool he uses. If you don’t do that, you’re just wasting your time looking for a solution where none will ever be found.” Similarly, in the wake of the Sandy Hook tragedy, Rep. Louis Gohmert pontificated : “I refuse to play the game of ‘assault weapon.’ That’s any weapon. It’s a hammer. It’s the machetes. In Rwanda that killed 800,000 people, an article that came out this week, the massive number that are killed with hammers.”

Here’s the rather obvious problem with such thinking: Firearms are more lethal than knives, machetes and hammers. Gunshot wounds frequently cause catastrophic damage . And the ability to maintain a quick and steady rate of fire allows a gunman to maximize casualties. There is a reason that American mass killers choose assault-style rifles to carry out their attacks, not knives or hammers.

On Dec. 14, 2012, a man wielding a knife assaulted people at a school in Chempeng, China, stabbing 23 children and one adult. Hours later, a man armed with an AR-15 attacked an elementary school in Newtown , Conn., shooting 20 students and eight adults. At Sandy Hook, all 20 children and six of the eight adults died. In China, there wasn’t a single fatality. The gun made all the difference.

Even the most heart-wrenching acts of gun violence are now so ordinary and routine that writing a timely article about the subject has become almost impossible. One mass shooting replaces another, permitting little time for meaningful reflection or catharsis. While details about the tragedy in Dallas are still emerging, some facts are painfully clear: The shooter was reportedly armed with high-powered weaponry, was clearly undeterred by good guys with guns and indeed specifically targeted those good guys. Yet again, our country’s lax gun laws helped a bad guy unleash horrific carnage.

Evan DeFilippis and Devin Hughes are the founders of the gun violence prevention site Armed With Reason .

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

Republicans accuse Obama of pushing gun control agenda after Dallas shootings

Gun control takes center stage in new L.A. play ‘Church & State’

House Democrats keep up gun control push as they return from recess

More to Read

Granderson: Can the Chiefs parade shooting inspire enough Republican voters to make a change?

Feb. 15, 2024

Don’t bring a moral argument to a gunfight, Jonathan Metzl tells liberals in new book

Feb. 2, 2024

Letters to the Editor: I’m too old to aim a gun. Does the Constitution let me defend myself with artillery?

Oct. 24, 2023

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More From the Los Angeles Times

Opinion: A deadly but curable disease is thriving in L.A.’s jails. That’s unacceptable

Granderson: Caitlin Clark is having a moment in women’s basketball. She shouldn’t be the only one

April 1, 2024

Opinion: Laken Riley’s killing does reflect a broader danger. But it isn’t ‘immigrant crime’

Opinion: The real AI nightmare: What if it serves humans too well?

March 31, 2024

In gun debate, both sides have evidence to back them up

Ph.D. Student in Political Science, University of Missouri-Columbia

Kinder Institute Assistant Professor of Constitutional Democracy, University of Missouri-Columbia

Disclosure statement

Jennifer Selin has received funding for her research on the executive branch from the Administrative Conference of the United States. In addition, she has received funding for her research on Congress from the Dirksen Congressional Center and the Center for Effective Lawmaking.

Zach Lang does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

Gun control is back in the U.S. political debate, in the wake of mass shootings in California, Boulder and Atlanta.

Democrats see stricter gun control as a step toward addressing the problem. In March 2021, as the House of Representatives passed two gun control bills, Speaker Nancy Pelosi claimed that the “ solutions will save lives .”

Many Republicans disagree, arguing as Sen. Ted Cruz has that proposed laws seeking to require background checks on all firearms sales and transfers and to ban assault weapons are “ ridiculous theater ” that fail to reduce mass shootings.

As two political scientists trained in data analysis , we set out to determine whether gun control legislation actually prevents mass shootings. We collected data on all mass shootings that occurred between February 1980 and February 2020. We then examined key information on the perpetrators, weapons used and laws in effect at the time of shooting.

Our research, which is yet to be published in an academic journal, suggests that there is statistical evidence to support both parties’ positions about gun control legislation.

While stricter gun control laws may make mass shootings slightly less common, our research suggests that the rhetoric of both parties may not tell the full story. Rather than federal gun control laws, policies that focus on violence prevention at the community or individual levels may be more effective at preventing mass shooting deaths.

Mass shootings in the past 40 years

We defined a mass shooting as a single incident in which a perpetrator with no connection to gang activity or organized crime shot and killed three or more people. This is similar to the definition Congress uses .

We found there were 112 of these events between 1980 and 2020; the number of mass shootings each year has increased over time. An overwhelming majority of mass shooters – 87% of them – obtained their firearms legally. Nearly all shooters – 93% – shot their victims in the same state where they obtained their weapons.

These facts suggest that existing gun laws and regulations governing gun purchases and firearms that cross state lines may not be working to reduce mass shootings. Our study did not address whether or how other forms of gun violence might be affected by those laws.

In fact, mass shootings tended to occur in states with stricter regulations. Of the states with the highest per capita rates of mass shootings, many – like Connecticut, Maryland and California – employ background checks and assault weapons bans.

By contrast, 18 states did not have a single mass shooting event over the entire 40-year period. Many of these states – like West Virginia, Wyoming and South Dakota – have high rates of gun ownership and relatively loose gun control laws.

But those data patterns don’t tell the full story of our analysis.

The effects of gun laws

Gun laws aren’t the only factors that affect where and when mass shootings occur. The number of police officers per capita, a community’s population density and crime rate, and other demographic characteristics such as unemployment rates and average income can also matter.

We used statistical methods to control for those factors, narrowing our analysis to find out whether various types of gun control laws affected the number of mass shootings or number of mass shooting deaths in each state each year.

Specifically, we examined the effects of four different types of gun control legislation: background checks; assault weapons bans; high-capacity magazine bans; and “ extreme risk protection order ” or “red flag laws” that let a court determine whether to confiscate the guns of someone deemed a threat to themselves or others.

We found that background check requirements, assault weapons bans and high-capacity magazine bans each reduce the number of mass shootings in the United States – but only by a small amount. For instance, enacting a statewide assault weapons ban decreases the number of mass shootings in the state by one shooting every six years. And none of the four types of gun control legislation correlate with fewer total mass shooting deaths.

And laws that remove an individual’s right to own firearms if that individual poses a risk to the community do not affect the number of mass shooting events.

Beyond gun control

Our analysis suggests that Americans who want to make mass shootings less frequent and less deadly may want to think beyond gun control legislation.

Statistically, mass shootings tend to occur in large, densely populated states with higher income and education levels per capita. While these states often respond to mass shootings by passing gun control legislation, it may be that alternative avenues are more successful.

For example, we find that increasing the number of police officers per capita decreases the number of mass shootings.

There is a wide variety of policy options designed to prevent mass shootings. The American Psychological Association suggests a comprehensive community approach that works to identify prevention strategies that bring public safety officials, schools, public health systems and faith-based groups together to reduce gun violence.

Aaron Stark , who says he was almost a mass shooter, explains that mass shootings can be an act of desperation resulting from frustration, stress and an individual’s perception that they lack power. This is in line with a new U.S. Secret Service report that suggests politicians may need to think beyond the accessibility of guns. Violence prevention strategies that focus on interpersonal and community relations may be more effective than gun control legislation.

Framing the debate

Many policy options involve value judgments stemming from beliefs about the U.S. Constitution and the power of government to regulate guns.

Among people who think that restricting gun access reduces mass shootings, people disagree over whether the country should prioritize the individual freedoms of gun owners or the safety and peace of mind of non-gun owners. These differing views can reflect different interpretations of the extent to which the Constitution protects the rights of individuals to keep and bear arms.

States have a role to play, too. Federal gun policy covers the entire nation. But our data indicates that attention to state and local factors can play an important role in preventing mass shootings.

In the end, gun control remains a debate about facts and context, complicated by a disagreement over constitutional values.

[ Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter .]

- Gun control

- Gun violence

- Mass shootings

- Second Amendment

- Gun policy US

- Gun research

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Initiative Tech Lead, Digital Products COE

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

- Share full article

Gun Control, Explained

A quick guide to the debate over gun legislation in the United States.

By The New York Times

As the number of mass shootings in America continues to rise , gun control — a term used to describe a wide range of restrictions and measures aimed at controlling the use of firearms — remains at the center of heated discussions among proponents and opponents of stricter gun laws.

To help understand the debate and its political and social implications, we addressed some key questions on the subject.

Is gun control effective?

Throughout the world, mass shootings have frequently been met with a common response: Officials impose new restrictions on gun ownership. Mass shootings become rarer. Homicides and suicides tend to decrease, too.

After a British gunman killed 16 people in 1987, the country banned semiautomatic weapons like the ones he had used. It did the same with most handguns after a school shooting in 1996. It now has one of the lowest gun-related death rates in the developed world.

In Australia, a 1996 massacre prompted mandatory gun buybacks in which, by some estimates , as many as one million firearms were then melted into slag. The rate of mass shootings plummeted .

Only the United States, whose rate and severity of mass shootings is without parallel outside conflict zones, has so consistently refused to respond to those events with tightened gun laws .

Several theories to explain the number of shootings in the United States — like its unusually violent societal, class and racial divides, or its shortcomings in providing mental health care — have been debunked by research. But one variable remains: the astronomical number of guns in the country.

America’s gun homicide rate was 33 per one million people in 2009, far exceeding the average among developed countries. In Canada and Britain, it was 5 per million and 0.7 per million, respectively, which also corresponds with differences in gun ownership. Americans sometimes see this as an expression of its deeper problems with crime, a notion ingrained, in part, by a series of films portraying urban gang violence in the early 1990s. But the United States is not actually more prone to crime than other developed countries, according to a landmark 1999 study by Franklin E. Zimring and Gordon Hawkins of the University of California, Berkeley. Rather, they found, in data that has since been repeatedly confirmed , that American crime is simply more lethal. A New Yorker is just as likely to be robbed as a Londoner, for instance, but the New Yorker is 54 times more likely to be killed in the process. They concluded that the discrepancy, like so many other anomalies of American violence, came down to guns. More gun ownership corresponds with more gun murders across virtually every axis: among developed countries , among American states , among American towns and cities and when controlling for crime rates. And gun control legislation tends to reduce gun murders, according to a recent analysis of 130 studies from 10 countries. This suggests that the guns themselves cause the violence. — Max Fisher and Josh Keller, Why Does the U.S. Have So Many Mass Shootings? Research Is Clear: Guns.

Every mass shooting is, in some sense, a fringe event, driven by one-off factors like the ideology or personal circumstances of the assailant. The risk is impossible to fully erase.

Still, the record is confirmed by reams of studies that have analyzed the effects of policies like Britain’s and Australia’s: When countries tighten gun control laws, it leads to fewer guns in private citizens’ hands, which leads to less gun violence.

What gun control measures exist at the federal level?

Much of current federal gun control legislation is a baseline, governing who can buy, sell and use certain classes of firearms, with states left free to enact additional restrictions.

Dealers must be licensed, and run background checks to ensure their buyers are not “prohibited persons,” including felons or people with a history of domestic violence — though private sellers at gun shows or online marketplaces are not required to run background checks. Federal law also highly restricts the sale of certain firearms, such as fully automatic rifles.

The most recent federal legislation , a bipartisan effort passed last year after a gunman killed 19 children and two teachers at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, expanded background checks for buyers under 21 and closed what is known as the boyfriend loophole. It also strengthened existing bans on gun trafficking and straw purchasing.

— Aishvarya Kavi

Advertisement

What are gun buyback programs and do they work?

Gun buyback programs are short-term initiatives that provide incentives, such as money or gift cards, to convince people to surrender firearms to law enforcement, typically with no questions asked. These events are often held by governments or private groups at police stations, houses of worship and community centers. Guns that are collected are either destroyed or stored.

Most programs strive to take guns off the streets, provide a safe place for firearm disposal and stir cultural changes in a community, according to Gun by Gun , a nonprofit dedicated to preventing gun violence.

The first formal gun buyback program was held in Baltimore in 1974 after three police officers were shot and killed, according to the authors of the book “Why We Are Losing the War on Gun Violence in the United States.” The initiative collected more than 13,000 firearms, but failed to reduce gun violence in the city. Hundreds of other buyback programs have since unfolded across the United States.

In 1999, President Bill Clinton announced the nation’s first federal gun buyback program . The $15 million program provided grants of up to $500,000 to police departments to buy and destroy firearms. Two years later, the Senate defeated efforts to extend financing for the program after the Bush administration called for it to end.

Despite the popularity of gun buyback programs among certain anti-violence and anti-gun advocates, there is little data to suggest that they work. A study by the National Bureau of Economic Research , a private nonprofit, found that buyback programs adopted in U.S. cities were ineffective in deterring gun crime, firearm-related homicides or firearm-related suicides. . Evidence showed that cities set the sale price of a firearm too low to considerably reduce the supply of weapons; most who participated in such initiatives came from low-crime areas and firearms that were typically collected were either older or not in good working order.

Dr. Brendan Campbell, a pediatric surgeon at Connecticut Children’s Medical Center and an author of one chapter in “Why We Are Losing the War on Gun Violence in the United States,” said that buyback programs should collect significantly more firearms than they currently do in order to be more effective.

Dr. Campbell said they should also offer higher prices for handguns and assault rifles. “Those are the ones that are most likely to be used in crime,” and by people attempting suicide, he said. “If you just give $100 for whatever gun, that’s when you’ll end up with all these old, rusted guns that are a low risk of causing harm in the community.”

Mandatory buyback programs have been enacted elsewhere around the world. After a mass shooting in 1996, Australia put in place a nationwide buyback program , collecting somewhere between one in five and one in three privately held guns. The initiative mostly targeted semiautomatic rifles and many shotguns that, under new laws, were no longer permitted. New Zealand banned military-style semiautomatic weapons, assault rifles and some gun parts and began its own large-scale buyback program in 2019, after a terrorist attack on mosques in Christchurch. The authorities said that more than 56,000 prohibited firearms had been collected from about 32,000 people through the initiative.

Where does the U.S. public stand on the issue?

Expanded background checks for guns purchased routinely receive more than 80 or 90 percent support in polling.

Nationally, a majority of Americans have supported stricter gun laws for decades. A Gallup poll conducted in June found that 55 percent of participants were in favor of a ban on the manufacture, possession and sale of semiautomatic guns. A majority of respondents also supported other measures, including raising the legal age at which people can purchase certain firearms, and enacting a 30-day waiting period for gun sales.

But the jumps in demand for gun control that occur after mass shootings also tend to revert to the partisan mean as time passes. Gallup poll data shows that the percentage of participants who supported stricter gun laws receded to 57 percent in October from 66 percent in June, which was just weeks after mass shootings in Uvalde, Texas, and Buffalo. A PDK poll conducted after the shooting at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde found that 72 percent of Republicans supported arming teachers, in contrast with 24 percent of Democrats.

What do opponents of gun control argue?

Opponents of gun control, including most Republican members of Congress, argue that proposals to limit access to firearms infringe on the right of citizens to bear arms enshrined in the Second Amendment to the Constitution. And they contend that mass shootings are not the result of easily accessible guns, but of criminals and mentally ill people bent on waging violence.

— Annie Karni

Why is it so hard to push for legislation?

Polling suggests that Americans broadly support gun control measures, yet legislation is often stymied in Washington, and Republicans rarely seem to pay a political price for their opposition.

The calculation behind Republicans’ steadfast stonewalling of any new gun regulations — even in the face of the kind unthinkable massacres like in Uvalde, Texas — is a fairly simple one for Senator Kevin Cramer of North Dakota. Asked what the reaction would be from voters back home if he were to support any significant form of gun control, the first-term Republican had a straightforward answer: “Most would probably throw me out of office,” he said. His response helps explain why Republicans have resisted proposals such as the one for universal background checks for gun buyers, despite remarkably broad support from the public for such plans — support that can reach up to 90 percent nationwide in some cases. Republicans like Mr. Cramer understand that they would receive little political reward for joining the push for laws to limit access to guns, including assault-style weapons. But they know for certain that they would be pounded — and most likely left facing a primary opponent who could cost them their job — for voting for gun safety laws or even voicing support for them. Most Republicans in the Senate represent deeply conservative states where gun ownership is treated as a sacred privilege enshrined in the Constitution, a privilege not to be infringed upon no matter how much blood is spilled in classrooms and school hallways around the country. Though the National Rifle Association has recently been diminished by scandal and financial turmoil , Democrats say that the organization still has a strong hold on Republicans through its financial contributions and support, hardening the party’s resistance to any new gun laws. — Carl Hulse, “ Why Republicans Won’t Budge on Guns .”

Yet while the power of the gun lobby, the outsize influence of rural states in the Senate and single-voter issues offer some explanation, there is another possibility: voters.

When voters in four Democratic-leaning states got the opportunity to enact expanded gun or ammunition background checks into law, the overwhelming support suggested by national surveys was nowhere to be found. For Democrats, the story is both unsettling and familiar. Progressives have long been emboldened by national survey results that show overwhelming support for their policy priorities, only to find they don’t necessarily translate to Washington legislation and to popularity on Election Day or beyond. President Biden’s major policy initiatives are popular , for example, yet voters say he has not accomplished much and his approval ratings have sunk into the low 40s. The apparent progressive political majority in the polls might just be illusory. Public support for new gun restrictions tends to rise in the wake of mass shootings. There is already evidence that public support for stricter gun laws has surged again in the aftermath of the killings in Buffalo and Uvalde, Texas. While the public’s support for new restrictions tends to subside thereafter, these shootings or another could still produce a lasting shift in public opinion. But the poor results for background checks suggest that public opinion may not be the unequivocal ally of gun control that the polling makes it seem. — Nate Cohn, “ Voters Say They Want Gun Control. Their Votes Say Something Different. ”

If You Want Gun Control, You Need To Understand These Pro-Gun Arguments

As I write this, we are between mass shootings in the United States. I don’t mean mass shootings in the way that statisticians use the term — referring to four or more people injured or killed (besides the shooter) — because there has been literally no breathing room between gun incidents of that variety this year. I’m talking about mass shootings in the “demand widespread public attention” definition of the term. Shootings with simple, chilling designations: Kip Kinkel, Sandy Hook, Columbine, Pulse Nightclub, Vegas, San Bernadino, Isla Vista, Parkland. (These are out of order and off the top of my head.)

The fact that we are between mass shootings by its nature implies that public outcry for a remedy to gun violence is at a low. Though Parkland’s students have done a valiant job pushing their agenda forward and keeping people focused , this is the cycle we’re in. People fighting for social justice on a variety of fronts are always going to struggle going up against a singularly-focused organization like the NRA . Gun zealots use the calm between shootings to pass small-scale gun bills (like the silencer bill in Arizona ); those fighting for gun control would be wise to do the same. Part of that means deepening their knowledge of the issues they’re up against.

You remember the end of 8 Mile when Eminem’s B-Rabbit predicts what everyone is gonna say to beat him? It’s a hell of an argument tactic and one well worth paying attention to if you’re fighting for reasonable gun control. To win the battle, you have to be ready to parry the other side’s attacks. You even have to be able to see some degree of logic to their thinking. Sure, you can act totally baffled that they believe what they believe and mock them to your private echo chamber, but… how’s that been working out over the past two decades?

If you really want gun control — and plan to be vocal about it — you need to understand these pro-gun arguments.

1. Mass shooters are statistical anomalies.

There have been 250 mass shootings (four or more shot, not including the shooter) so far in 2018. We don’t know how many people own guns in the US (it’s against the law!), but the rock-bottom estimate is 40.4 million . That’s less than a 0.0007% chance that one of America’s gun owners has been involved in a mass shooting this year. It’s statistically negligible. We’re talking lightning strike-level odds.

If you include all 36,378 gun incidents this year (in which a gun was discharged leading to injury or death), you’re still down at less than a 0.09% chance of any given gun owner being involved. You can play with these stats all you want, but what you’ll find is that when grouped in with gun owners as a whole, mass shooters are statistical anomalies. If that’s your sample size (total population of civilian gun owners), this sort of violence is indeed exceedingly rare.

THE ARGUMENT AGAINST — For a pro-gun advocate to act as if you are in contention with all gun ownership and thereby contrast statistics on shootings with a sample size of “all guns in circulation” or “all gun owners” is disingenuous. You’re not fighting those battles. Because — most likely — you don’t want all guns removed from circulation. You simply want tighter rules and regulations, more oversight and licensing, mental health evaluations for certain gun owners, and the restriction of specific weapons.

In these cases, there really is no way to parse statistics because we’ve never tried things any other way in America. So your argument against the “mass shooters are an anomaly” line is to say: “Right, but they are a preventable (or at-least semi-manageable) anomaly. Throughout history our government has always tried to prevent/ minimize the effect of disasters (earthquakes, hurricanes, wildfire), there is no reason we wouldn’t do it with mass shootings.”

Or, if the person you’re arguing with just won’t let go of statistics, “The U.S. has no useable statistics because things have always been this way — there’s no ‘experiment in progress.’ If you won’t allow us to compare gun statistics from literally any other country on earth, then let us try things another way for 10 years so we can have data to study.”

2. The Second Amendment protects gun owners. End of story.

Our nation is governed by a constitution. It is the framework of our democracy and the document that irrevocably separates us from monarchies, communist-states, and dictatorships. That constitution protects the right to bear arms. It is clear and unwavering in that point.

Yes, people have died and yes, that is a tragedy. But because those various tragedies are essentially anomalies (see above), they aren’t worth sacrificing the constitution for. This sacred document is the foundation of everything we do. To alter it in order to prevent an absolute statistical improbability is absurd.

Do we change the first amendment every time someone yells “fire” in a movie theater?

THE ARGUMENT AGAINST — We absolutely should not abolish the second amendment. It has a place in the constitution for a reason and belongs there. But the “‘fire’ in a movie theater” example reminds us that the Constitution itself (via further amendments, state laws, and the Supreme Court) is always being reinterpreted to reflect changing times.

When the document was written there were no AR-15s. Putting restrictions on gas-operated assault rifles, high-capacity magazines, and gun purchasing for those with a history of mental instability is not a gutting of the second amendment. It’s the sort of clarification that our Supreme Court has made since it was founded. States are usually left in control of these decisions (which is why the NRA so often fights on the state level), but if the conversation gets stuck on the federal government, so be it. In 2014, the Supreme Court modified the first amendment with a ruling about the speech of public employees — so don’t pretend like this is some unheard of constitutional doomsday scenario. It’s literally part of our governmental system.

3. The threat of tyranny is real.

This is a more common argument than you might think . In fact, if you’re unwilling to fully fathom any other pro-gun argument, do yourself a favor and savvy out this one . Like the second amendment itself, the idea of protecting the right of the people to bear arms in order to resist tyranny is rooted in the English Bill of Rights of 1689. The section pertaining to this subject was interpreted by Sir William Blackstone with the following:

The natural right of resistance and self-preservation, when the sanctions of society and laws are found insufficient to restrain the violence of oppression.

That line sums the issue up pretty neatly, and the response to this argument by liberals or anyone who is pro-gun control is often an eye roll. To talk as if the citizenry may need weapons to revolt against a tyrannical government is treated like some conspiracy-brand mania.

If you’ve done this — waved off arguments of “freedom from tyranny” with regard to guns — shame on you. Think of the marginalized people in this nation who could make a compelling case that the nation’s government has treated them tyrannically.

- Native Americans could make an excellent case that this government has been tyrannical to them from its founding days until the present.

- Black Americans could make an excellent case that this government was tyrannical to them from the days of the transatlantic slave trade to the redlining era (or perhaps until the present).

- Women could make an excellent case that this government was tyrannical to them from its founding days until 1973 when Roe v Wade was decided (or perhaps until the present).

- The poor could make an excellent case that this government has been tyrannical to them from its founding days until the present.

You can not fight for social justice in this world on one hand and completely discount the right of people to protect themselves from a government which they believe — with ample evidence — has treated them unjustly. If you do, or if you somehow think every “militia” is made up of angry white men, it’s time you read up on The Deacons for Defense and Justice — who literally changed the entire landscape of the city of Jonesboro, Lousiana by forming a militia to combat the Klan. Spoiler: It worked.

THE ARGUMENT AGAINST — Sir William Blackstone wrote that the right to bear arms to fight tyranny required “due restrictions.” The Second Amendment allows for a “well regulated” militia. Those modifiers are important. Because it’s not like five angry dudes with AKs are going to overthrow a government that insists on spending so much money to arm itself that its allies gleefully cut their programs to the bone . More importantly, we have an entire system of checks and balances, the constitution, plus strong state rights to secure us against this sort of systemic villainy .

To completely discount the idea that America might one day have a revolution is to know nothing of the wealth gap or to be unable to fathom how it will eventually connect all people who feel powerless. America is not a true democracy. The rich have a disproportionate amount of power, making it more akin to an oligarchy or plutocracy . But until you’re ready to throw the proverbial tea into the Boston Harbor and get things really revved up, you have to follow the laws of the land and the laws of the land make allowances for the militia to be “well regulated.”

Someone who is pro-gun control shouldn’t write off the “defense of tyranny” argument, it is indeed a right of the people — but it doesn’t supersede the right of the people to regulate the shit out of said militia to keep our children from getting killed at school.

4. A good guy with a gun can prevent a bad guy with a gun.

Good guys with guns have indeed stopped bad guys with guns over the years — dating back to the Wild West. There’s Jeanne Assam, who stopped a church shooting in Colorado ; Alton Nolen, who protected a clerk at his grocery story by shooting her assailant with his private sidearm ; and a healthy smattering of bold grandmothers staring down intruders.

The logic here is that a person with a gun and a level-head can save people from an armed maniac. Or that a well-armed adult can protect his or her family from intruders. Not surprisingly, a Gallup poll found that protection was the #1 reason Americans gave for wanting guns .

THE ARGUMENT AGAINST — This is literally the easiest of all pro-gun arguments to defeat. Sure, there have been cases of good guys with guns stopping bad guys with guns, but they are 1) exceedingly rare and 2) typically concern people who have extensive gun training ( Assam was ex-police , working on-site as a security guard; Nolen was military trained). Regardless, these are all pieces of anecdotal evidence. Anecdotal evidence is fun and emotional and splashy but it’s not real . Cherry picking cases proves nothing.

The truth is, no statistics get anywhere close to suggesting that the number of “good guys with guns shooting bad guys with guns” outweighs the risk of in-home shooting accidents and impulsive suicides.

Good guys with guns are real, but they’re far too rare to build a cogent argument around. It’s silly.

“Sure,” the gun advocate says, “but I’m different. I’m smart and steady and know what I’m doing.”

Statistically speaking, that’s not true . And if you are a male, there is a significant possibility that your very desire to own a gun comes from feelings of powerlessness in your day-to-day life , like the open carry advocates who videotape themselves making the public squirm. In short, you may trust yourself, but we don’t trust you and there is literally no metric on earth that supports the claim that we ought to.

5. “Fuck off, I like Guns” – Jim Jefferies.

This is big. It’s actually a relatively strong argument.

- My constitution protects them.

- My state allows them (under rules which I follow).

- My paid advocates (the NRA) help protect them.

- And I think they’re fun.

So fuck off, I like guns.

THE ARGUMENT AGAINST — Fair enough. But fuck off back, because your toy does not come before my rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. I get to live. I get to feel safe. These are unalienable protections under the Constitution.

The “fuck off, I like guns” argument is counteracted by essentially saying, “Great, but you liking something doesn’t mean you get to do it without restrictions.” Speaking personally, I was recently thwarted in an attempt to bring a vacuum-sealed cured pork butt ( culatello ) from Italy to the United States. My love for cured meat was blocked by government regulations.

“Fuck off, I like cured meat.” I could have said to the customs officer. But he would have still been within his rights to take my culatello from me. He has a higher law to answer to than my passions.

This is a good time to say to someone:

“Virtually every hobby on earth has regulations. Why is yours different? Rock climbers, pot smokers, home cooks, surfers… we all deal with restrictions and rules with regards to our hobbies. And our hobbies aren’t inextricably tied to violence.”

Which opens the door to remind people that very few gun-control activists want to snatch guns from everyone’s cold dead hands. Instead, we want to manage them in a way that takes the anomaly of mass shootings and makes it even rarer. So rare that writers can no longer rattle them off like a shopping list without having to turn to Google. So rare that families aren’t routinely shattered and communities aren’t forever changed. Sure, maybe we want to take your gas-powered AR15 from you , but you’re welcome to replace it with a different rifle.

The arguments for guns aren’t crazy. They aren’t even inherently evil. They deserve to be taken seriously and debated. Once debated, it becomes clear: Though pro-gun arguments are based on logic, they are also frail and weak. They stretch anecdotes in order to battle unassailable facts.

By understanding these arguments and the fears and ideas that give birth to them, you’ll better understand the conversation as a whole. In doing so, the window to actually shift someone else’s thinking is eased opened a millimeter more than it was before. That’s not a sea change, but it’s something.

A Case Against Gun Control

Previously in this series:

- “ The Cultural Roots of a Gun-Massacre Society ”

- “ A Veteran on the Need to Control Civilian Arms ”

- “ Show Us the Carnage, Continued ”

- “ Only in America ”

- “ Show Us the Carnage ”

- “ The Empty Rituals of an American Massacre ” and before that:

- “ Why the AR-15 Is So Lethal ”

- “ The Nature of the AR-15 ”

- “ Why the AR-15 Was Never Meant to be in Civilian Hands ”

- “ More on the Military and Civilian History of the AR-15 ” and

- “ The Certainty of More Shootings ,” from back after the Aurora massacre

- “ Two Dark American Truths from Las Vegas ,” with included video.

What’s the mail like from those who reject the need for new gun laws? Here are two samples. The first is — unfortunately, but realistically—representative in its tone and argumentative style of most of the dissenting messages that have arrived:

No mass shootings else where? China...Mao...unarmed public....millions killed Russia....gulag....KGB...unknown number killed....unarmed public Balkans....Serb nationalism....thousands killed....unarmed public You can argue both sides until you are blue in the face, but the way this country's government acts I want to be able to protect those I love and my property. I also believe that this country has turned away from the concepts that made it great. The media has been complicit in this by promoting "headline" horror stories to increase market share or to scoop others. The latest shooting has just as much or more to do with the mental health crisis in this country than guns, but let's blame an inanimate item and not the user. It's part of the failure to make people take responsibility for their actions that is condoned by politicians and media both. To truly fix societies problems is our greatest challenge, using a type of firearm to blame ALL societies ills is not going to solve anything. If you are not promoting a broad fix to a social problem then you are promoting a narrow "headline" grabbing stance, then on to the next"headline". Americans are letting others think for them i.e. jump on any bandwagon. People need to think for themselves, the most underused human organ these days is the brain

To the reader’s last point I say: Amen.

A different kind of argument comes from a reader who contrasts my enthusiasm, as a small-plane pilot, for the “right to fly,” with my skepticism of AR-15 owners’ right to enjoy, use, or even possess their weapons. The reader says:

In response to your notes on the AR-15’s I think the pro-AR or at least neutral AR position comes down to that despite the high profile shooting, the actual deaths from AR’s are a small portion of total deaths and the lawful owners of AR’s don’t see why they should be deprived of their rights due to the illegal actions of others.

You, who do not shoot AR’s (or at all as far as I know) do not see these rights as important, and therefore see it as no big deal to take them away, regardless if it infringes on any rights, which you reject anyway. To give you an example of why the gun people disagree with you, consider something you do enjoy: Flying. Most people who shoot AR’s view it like you view flying—something that they enjoy; the act of going to the range and shooting targets or “plinking” cans at home or whatever, is just an activity they like to do. It then gives them the added benefit of being usable for home protection and the admittedly whacked out perspective that they will fight the oppressive government should it ever come to that. Again, the last is probably ridiculous, but it is a psychic benefit important to many people; the home protection aspect is real and the enjoyment of shooting is real. You would probably say that all may be true, but is not worth the deaths. The pro-gun response is that the deaths from AR’s are a small, small proportion of overall gun homicides, despite the high profile cases. Again, lets compare it to flying, something you love. Every year, roughly 400-450 people die in general aviation accidents. For rifles total, not AR rifles alone, but total rifles, the latest year (2014) had 248 people murdered. (suicides are unknown, I’d suspect they are a similar percentage with homicides, i.e. under 5%; accidental death are almost exclusively handguns). To put this in context, there are somewhere around 5,000,000 AR style rifles in circulation, meaning in any given year, there is (at most) about 1 murder per 20,161 AR rifles in 2014. By contrast, there are roughly 210,000 private planes, so that would equal 1 death per 525 planes. So from a purely statistical standpoint, private planes are about 80 times more deadly than AR rifles. I realize that these stats are not apples to apples and if you include suicides and accidental deaths the AR might be as deadly or more deadly than private planes (although on a per unit basis, I would say owning a plane is far likelier to kill someone than owning an AR). But imagine if the government took these statistics and banned private planes and non-commercial aircraft. What would your response be? I’m sure you can come up with all kinds of reasons why flying is important and useful and banning planes would be a complete over-reaction, but I can also point out that the vast majority of people don’t fly private planes and do just fine (plus you destroy the environment and suck up gobs of government money with regional airports and below market landing fees). What if [the Las Vegas murdered] instead of buying a bunch of AR’s instead rented a Beechcraft Barron 58 (or something much larger, I’m not a plane guy), filled it up that barrels of gasoline and flew into an NFL stadium or concert full of people, something it seems he had every capability of doing? Could there have been as many deaths? If there had been, and the government banned private aircraft and you could no longer fly, wouldn’t that piss you off? You are now prevented from doing something you love (and you only do it because you love it, there is no economic case to be made for private planes) because some evil act committed by someone unknown to you. Again, I’m sure you don’t see it this way because you see no use to AR rifles. But I see no use to private planes; I think there is no reason for people who are not commercial aircraft carriers to fly, not to mention the vast and ridiculous subsidies private planes receive. One of the great things about America is you can do things other people don’t approve of; that you can do things like shooting guns or flying just because you enjoy it. I realize planes are heavily regulated, I guess my point is that despite the heavy regulation there are still deaths and despite the low regulation of AR’s there are relatively few deaths compared to other weapons. Again, God forbid the Vegas shooter flew his plane into an airliner (which is actually quite difficult to do, but you get my point. None of those regulations can prevent that sort of act). That is what frustrates many gun folks is the attention on AR’s when the vast majority of gun deaths come from cheap handguns in the hands of criminals (which is illegal anyway) but the focus is banning guns used by legal gunowners, who are responsible for a fraction of a fraction of the harm. And as many people have mentioned, with 300 million guns in circulation, regulation is largely futile; the focus should be enforcing current laws IMO. If it makes you feel any better, I’d imagine we’ll be heading for a ban in the next 40 years or so if for no other reason that the hard core gun people are such profound assholes (as I’m sure your e-mails will attest to) they will alienate everyone eventually, so give it time. I like to shoot guns for enjoyment and use them for personal protection and the only AR I own is a 22LR which on a good day can kill a large rabbit, but seriously think the left focuses on symbols (scary looking guns) in the gun debate rather than facts.

I appreciate the reader laying it out in this detail. Here are two obvious differences in the plane-versus-AR-15 comparison, from my (no doubt biased) point of view:

Number 1: small airplanes kill a lot of people, but they very rarely hurt anyone who hasn’t chosen to get on board .

Several years ago near my then-home airport, the Montgomery County Airpark in Gaithersburg, Maryland, a private jet crashed, in bad weather, into a nearby house and killed a mother and two children who were inside. (In addition to killing the pilot and two others aboard the plane.) It was so horrific an incident, and so universally understood as a grotesquely “unfair” extension of damage to people who had not knowingly accepted the risk, that the entire flying community recognized it might change the future of the airport and flying practices there. (This was so even though the airport had been up and running many years before the nearby subdivisions went in and people moved to the area.)

The episode was horrific—and rare. On average, there’s about one fatal crash a day, year round, involving small airplanes in the United States — a rate that has slowly but steadily decreased . But in the course of an average year, very few of those episodes involve anyone on the ground. Some years it’s four or five people. Some years it’s none. By contrast: an average of around 90 people per day die of gunshot wounds, or a little under four per hour (not per year). Even after you remove gunshot suicides, which are around 60 percent of all U.S. gun deaths, there’s still an enormous difference between the damage done by guns to people who hadn’t knowingly accepted that risk, and the damage done by planes.

So: the undeniable dangers of small-plane aviation are almost completely limited to their own pilots and passengers. In this way aviation is like scuba diving, or motorcycle riding, or other statistically risky pursuits whose risks are concentrated on the practitioner. If the same were true of guns—that people using them were the only ones getting hurt or killed—the public debate would be quite different.

Number 2: If gun use and ownership were even 1 percent as tightly regulated as anything involving aviation, the landscape would also be entirely different.

Pilots are licensed, registered, subject to recurrent checks of everything from what prescription drugs they are taking to whether they have had any brushes with the law, apart from myriad regular checks of proficiency. (Sample: want to come with me for a night-time plane ride? Fine—but I need to have made three full takeoff-and-landing cycles at night time, in the previous 90 days, before I can legally take anyone with me in a plane at night. Do I want to use my instrument rating to make a flight when the weather is bad? Fine — but only if I have maintained legal “currency” by doing a certain number of instrument-conditions approaches and maneuvers in the previous six months. Do I want to fly at all? Let me tell you about the Biennial Flight Review, and the mandatory annual very detailed inspections of the plane itself.) Even a few of the federal regulations that apply to pilots would, if applied to gun ownership, be portrayed by today’s NRA as a catastrophic step toward totalitarian state control.

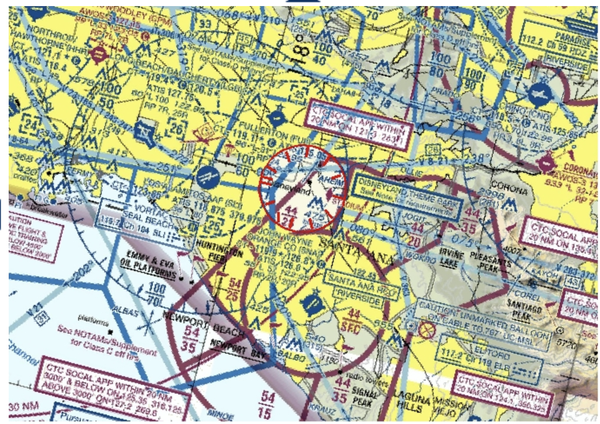

To answer the specific hypothetical: I couldn’t fly a gasoline- or bomb-laden plane over a crowd at a sports stadium, because there are no-fly zones over most such places now . Just as an illustration, from the FAA’s real-time map, here’s the (permanent) no-fly zone shown right over Disneyland. It’s the bright red circle with lines radiating inward from its border:

Yes, a determined and suicidal pilot could fly right through that and do damage. But everyone in the flying world knows that if that happened even one time, everything about flying “rights” and restrictions would change. Society would figure that it could not take that risk again. Here’s a real world illustration: after the 9/11 attacks, even though small airplanes had nothing to do with it, small airports around the country were shuttered for extended periods. Gaithersburg, where my propeller plane was at the time, was totally closed for about three months. No one could land or take off from there. The flight schools, maintenance shops, charter operations, and other businesses there were cut off cold, and of course many failed. Such is the public-risk/individual-privilege balance as it applies in aviation. Imagine the parallel with guns.

The balance between public risk and individual right/privilege is again coming into focus with guns. People who did not choose to expose themselves to gun risks, who were just going to a day at school, now lie dead, barely into their teens. That’s different from airplanes, it’s different from anything else. And it’s wrong.

The Reflector News

Featured stories, pros and cons of gun control in the united states, pro by lindsey wormuth | distribution manager.

Stricter gun control can sometimes seem like a never-ending argument against the Second Amendment and about whether gun laws can really keep people safe. The Second Amendment states that because a well-regulated militia is necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed upon. I never thought gun laws were too weak until I was in a situation involving a minor who had access to guns.

In May of 2018, I was at Noblesville High School the day that a school shooting took place at Noblesville West Middle School, nearly eight minutes away. I remember being told to barricade the door and windows and take cover in a corner. Although the shooting was not at my high school, not knowing what was going on and whether there also would be an active shooter at the high school was terrifying. The middle school shooter was a 13-year-old boy who injured a teacher and a student. According to The Washington Post , there were 90 school shootings nationwide in the two years of 2020-2022. Parents should be able to send their children to school and not worry about their children having to barricade themselves because their school has an active shooter.

“When the Post analyzed these [school] shootings, it found that more than two-thirds were committed by shooters under the age of 18,” according to the Austin American-Statesman . “The analysis found that the median age for school shooters was 16.” To gain more control over who has access to guns, they need to be less accessible to teenagers.

Besides school shootings, a gunman at the Greenwood Park Mall on July 17 “fired shots inside the food court . . . killing three people,” according to WTHR. The gunman was 20 years old, another young shooter.

Gun safety will always be an issue in the United States. To reduce shootings and gun-related suicides, we need to raise the minimum age to purchase guns, ban assault weapons, and require a permit in all states to carry a handgun. Despite the ongoing arguments, gun control legislation must be passed. People are suffering mass tragedies as a result of legislators’ inaction. According to the Indiana Government website , as of July 1, 2022 the State of Indiana will no longer require a handgun permit to legally carry, conceal or transport a handgun within the state. A common misconception about the law is that it allows anyone to be able to carry a handgun. There are still standards you have to meet to be able to legally carry. For example, anyone who was convicted of domestic violence or battery charges, was imprisoned for a federal offense “exceeding one year” or anyone under the age of 18 will not be able to legally carry a gun in Indiana, according to the Indiana Government website.

According to the National Rifle Association , “Even if criminals did submit to background checks, we’ve seen that these checks aren’t effective at stopping those who intend to use guns to commit crimes.” The NRA-ILA has created scenarios showing how background checks can be ineffective. One NRA-ILA scenario says this: “A drug addict lies about their addiction on a federal background check form. Although this individual is committing a federal crime, a background check most likely won’t stop them.” Another NRA-ILA scenario says this: “A person with no criminal history walks into a store to buy a gun they’ll use to commit a crime. A background check most likely won’t stop them.”Ultimately, there is no guaranteed way to identify whether someone who is purchasing a gun will commit a crime, but minimizing the people who can access guns can. Increasing the amount of steps with a background check could help eliminate the people who buy them to commit crimes. People should be able to go to school, the mall, or a club without the fear or threat of a shooting. The only way to reduce shootings is to change the laws.

Con by Olivia Pastrick | Staff Writer

Many proponents of an increase in gun control in the United States do not take into consideration the ineffectiveness of the current laws in place regarding citizens’ rights to bear arms. For example, the Gun Control Act of 1968 prohibits holders of Federal Firearms Licenses from transferring licenses to certain groups of people classified as irresponsible or potentially dangerous, according to the U.S. Department of Justice . However, this small form of gun control is clearly not doing its supposed job to stop or limit gun violence in the United States, as indicated by the 110 homicides in Indianapolis alone this year as of June 30, according to Fox59 . The question is still whether federally imposed gun control laws can be effective in reducing gun violence in the United States.

For starters, the root of the problem is not guns, it is people. Criminals with the intent to kill people would not likely be swayed from committing crime by additional laws when they are already breaking other laws. According to the National Rifle Association’s Institute for Legislative Action , 43.2% of prisoners in state or federal prison got their guns “off the street or on the underground market,” which would not be affected by additional gun control laws. Similar logic can be applied in examining the effectiveness of background checks for people who purchase firearms with the intent to harm others. These individuals already intend to break the law, so they would not likely be deterred by having to lie on a government form to pass a background check to obtain a gun.

Similarly, homicide rates in countries where guns are banned have not gone down. According to the California Rifle and Pistol Association , the United Kingdom’s homicide rate in 1996, before handguns were banned, was 1.12 per 100,000 people. In 1997, the year handguns were banned, it rose to 1.24, and in 2002 it peaked at 2.1 homicides per 100,000 people.

There have been times when, in U.S. cities, bans have been placed on the purchase and possession of guns. For example, the city of Chicago enacted a handgun ban in 1982 that prohibited residents from owning handguns for their own use even in their homes and required existing gun owners to re-register their weapons every year, according to ABC7 . This law made Chicago the city with the strictest gun laws in the country at that time, yet it did not curb murders in the city. According to the Chicago Tribune , in the decade after it banned handguns, murders jumped by 41 percent, compared with an 18 percent increase throughout the country. Again, this ban did not deter criminals with the intent to cause harm from obtaining firearms. The law was effectively made unenforceable by a 2010 Supreme Court decision that the Second Amendment protection of the individual’s right to possess firearms applies to cities and states, according to ABC7.

Additionally, there have been situations in the United States in which citizens armed with guns have helped take down people trying to inflict harm. For example, the Greenwood Park Mall shooting on July 17 was stopped within 15 seconds after it began by a citizen with a gun, according to WTHR . A ban on guns, or even stricter gun control laws, might have prevented the bystander from carrying a gun in the mall; and the shooting could have been much worse. Finally, with distrust in the government so high in the United States, pro-gun citizens consider their guns a level of protection against tyrannical government practices, according to NPR . People fighting for their right to bear arms also worry that if the government infringes upon the Second Amendment, nothing will stop the government from changing or taking away other rights that are seen as cornerstones of American life.

Recommended for You

Indianapolis Potholes

Why We Should Not Observe Presidents Day

Daylight Saving Time Should Stay for Good

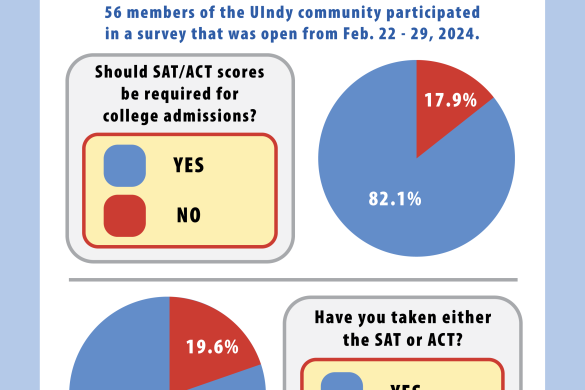

Requiring Standardized Tests Should be a Thing of the Past

Living in Indianapolis

‘BookTok’ Thrives on Marketability Rather than Artistic Integrity

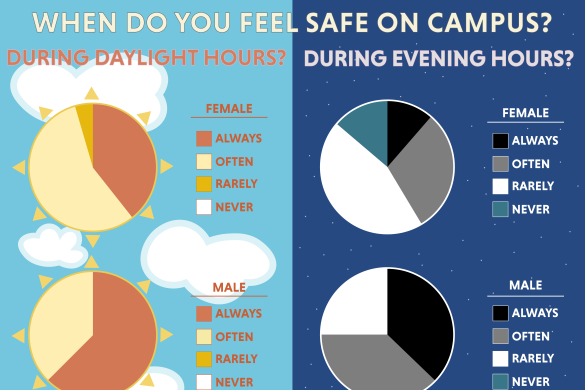

Let’s Change the Campus Security Narrative

I Am Tired of Being a Hoosier in the Current Political Climate

Advertisement

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- Home ›

- Reviews ›

In Defense of Gun Control

Hugh LaFollette, In Defense of Gun Control , Oxford University Press, 2018, 237pp., $99.00 (hbk), ISBN 9780190873363.

Reviewed by Firmin DeBrabander, Maryland Institute College of Art

Hugh LaFollette has offered an informative, compelling and readable contribution to the philosophical literature on America's gun debate, which, as of yet, is still relatively small. He gives an overview of three major sets of arguments for and against gun control: armchair arguments, rights based arguments, and empirical arguments. He appraises each in turn, and ultimately points out how and where the gun rights position is wanting, and why the case for gun control is stronger. He concludes by detailing several proposals for gun control. These include some well-known (and much debated) regulations, like gun registration and background checks on gun purchases, but one idea that is rather novel and little discussed, mandatory liability insurance for gun owners.

LaFollette leads off with what he calls 'armchair arguments' -- arguments for easy access to guns, or arguments against. By 'armchair arguments,' he means "common sense" arguments, where "the empirical elements of the reasoning lay in the background rather than the foreground," and are "supported by robust background knowledge of science, history, politics, and human behavior" (24-5). On the gun rights side, armchair arguments include the following: we will cause unanticipated and excessive costs in restricting the popular practice of gun collecting and gun use; we need unfettered access to guns in order to protect ourselves from harm, and from crime; and citizens require broad gun ownership in order to protect against government tyranny. Gun control armchair arguments, LaFollette says, are basically grounded in the conviction that widespread ownership of guns and easy access to firearms cause "an unacceptable level of harm" to society at large (40). Easy access to firerarms, gun control advocates claim, leads to higher incidences of violent crime, homicide, gun accidents and suicide.

In assessing rights-based arguments for or against gun control, LaFollette distinguishes between Fundamental Rights and Derivative Rights. In this section, he responds to philosophers who have written in support of the gun rights position, and notes that few support the fundamental rights position -- which would hold, for example, that I have a basic and natural right to own or carry a gun. If this sounds strange to hear, this is because gun rights are hardly ever articulated this way; it is more common to hear them articulated as derivative rights. For example, advocates will claim that my right to gun ownership derives from my right to be free from totalitarian government. Guns are the tools I require to free myself from or prevent such a regime. Or gun rights are derivative of my "right of self-defense against individual aggressors," and they are "the only (or best or most reliable or most effective or most reasonable) means of self-defense against aggression, either in or away from one's home" (77).

Here, LaFollette offers some compelling critiques. For one thing, he asks if guns are a necessary means to self-defense. That may not be the case, of course. Are guns handy tools, and useful in certain -- dire -- situations? Sure. But as a rule, they may not be, and are not in fact, necessary for the vast majority. I have written elsewhere that this gun rights claim -- that guns are a necessary means of self-defense -- makes sense only in a society where guns are prevalent, and gun laws lax -- so that gun owners can shoot me if I so much as appear threatening (thanks to Stand your Ground Laws). [1] In other words, we have needlessly produced a society rife with guns and lax gun laws, where one may indeed require a gun for self-protection; but it does not have to be that way. We could envision, and create, a different society. LaFollette notes that owning guns is not "generally and usually vital for an individual's security. The majority of people living in Europe and in the United States do not own guns and they flourish" (88). This latter point invokes another rebuttal to claims that the right to gun ownership is an important derivative right: gun rights advocates say we require guns to enjoy our freedoms, and the rights we have as democratic citizens -- freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, freedom from totalitarian government. And yet, most citizens of industrial democracies patently enjoy those freedoms, though they have few or no guns. Indeed, I have also argued, widespread gun ownership poses a greater threat to the rights and freedoms we enjoy as democratic citizens. Open carry, for example, is not going to make people more likely to speak with one another, or assemble, or engage in sometimes raucous protests against the government. [2]

LaFollette does not spend much time considering rights-based gun control arguments, which is not entirely surprising, since the gun rights movement is most insistent on this front. He briefly mentions one rights-based gun control argument: David DeGrazia's argument that prevalent gun ownership compromises our right not to be harmed. Our right not to be harmed is of course a necessary prerequisite for all the other rights we enjoy in a democratic society. [3] LaFollette announces that he sympathizes with DeGrazia's argument, but "will not discuss it here; those interested should read his discussion. I think the objections I raise here and later are sufficient to undercut the pro-gun advocates' argument" (90). But it might be helpful to look at an argument like DeGrazia's in this context, to understand what a rights-based gun control argument might look like, what sources it draws on, how it will be constructed, how it will fare, and how it may be vulnerable. Especially since LaFollette proposes to look at the gun issue from both sides, and with a strong degree of fairness and objectivity -- which he demonstrates in what I consider charitable treatment of gun rights arguments (see below) that have been thoroughly and widely questioned, if not debunked.

In any case, turning next to empirical arguments for or against gun control, gun rights advocates believe they have strong candidates on this front. LaFollette deals with two prominent figures in this vein: Gary Kleck and John Lott. Kleck has engaged in studies that, he claims, prove that guns are essential in the lives of ordinary Americans, because they are used in millions of incidents each year, to fend off criminal attack, and ensure personal protection. Kleck's survey "shows that there are 2.5 million DGUs (defensive gun uses) annually and also finds that defensive gun users have 'certainly or almost certainly saved' 400,000 lives annually"(141). Lott, by contrast, points to research that supports "shall-issue laws -- laws requiring authorities to issue carry permits to all but a small number of people," because they reduce "violent crime without significantly increasing accidental deaths" (144, his emphasis). Gun control advocates also believe they have drawn powerful and compelling arguments from empirical evidence, carried out by public health researchers. The "prohealth" approach, as LaFollette labels it, aims to propose regulations that can reduce the number of injuries and fatalities from the use of guns (147). Among empirical arguments are the following: gun control advocates note that jurisdictions with high gun ownership rates see higher gun fatality rates, on average; they also claim that high gun ownership rates correlate with higher rates of suicide; and widespread gun ownership, combined with lax gun storage and transfer laws, lead to higher incidences of accidental deaths and serious injuries.

LaFollette devotes a lot of time to discussions surrounding the empirical evidence. This is because he is alert to the problems of gathering and trusting empirical evidence, though gun control and gun rights advocates claim to rely heavily on it. It is very difficult to "find reliable empirical evidence," he notes (113). It is unclear whom to study, how, and for what -- as a general rule for empirical research; such decisions invariably frame, and limit, the study at hand. And empirical studies can go awry in many ways. But these problems are even more serious when it comes to "public policy issues," which "are neither practically nor morally amenable to [a high] degree of control and manipulation" (125). What's more, gun control studies are apt to lean on terms like 'safe' and 'risky' that are intolerably vague. By pointing this out, LaFollette means to say that empirical arguments in support of gun control are on equally shaky ground as those offered by gun rights opponents.

That said, Lott's and Kleck's work is liable to questions that are especially troubling -- and their findings are more dubious, as a result. For one thing, Kleck's study is supposed to correct for underreporting on DGUs in another well-regarded study, the NCVS or National Crime Victimization Study -- but Kleck's findings say that the NCVS underreported DGUs by 96%, which seems improbable. Kleck is also unfairly critical of the medical and public health community, who engage in similar and competing studies, considering them "rank amateurs employing primitive analytical tools" (171). Finally, Kleck makes the dubious claim that the 2.5 million DGUs per year have saved 400,000 lives -- without which, the US murder rate would be "nearly thirty times higher" than it is already (178). Our murder rate is already double that of Europe. Is Kleck really willing to accept that Americans are 60 times more murderous than our European counterparts? [4]