- Skip to main content

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Study Today

Largest Compilation of Structured Essays and Exams

Essay on A Decision You Regret

January 1, 2018 by Study Mentor Leave a Comment

The word ‘regret’ means feeling remorse. This word is a very powerful word that sometimes defines a person’s whole life. Regret is a strong feeling that doesn’t easily go away in fact at some points it doesn’t go away at all. Feeling regret about something is not uncommon or unheard of.

Each and every human being at some point in their life has felt regret about one thing or the other. I myself had felt this unpleasant feeling that I am not very fond of. As a matter of fact no person is fond of this unpleasant feeling and yet at some point in their life they have felt it.

However regret with time has turned into a wish that we could have done instead of what we did. This wish is something we always think about and it doesn’t matter that we don’t want to think about it and in our subconscious mind somewhere we are always thinking about it.

Regret is something like I wish I could have handled a situation differently than the way I did in reality. Feeling regret about something that I did is not good at all. In fact, if a person’s life is full of regrets then that person can’t bear himself by thinking about them which impacts the health of that person.

Regret is something that has already occurred in our life and there is no way of going back and correcting it for us.

In my life there are a few situations about which I feel regret and really wish that just somehow I could reverse the time and change what I did. But that is not possible and I have accepted it, well not willingly but as I don’t have a choice but to accept it so I did.

In every person’s life there comes a time when they could have done something better and it does not matter how they handled the situation, there will always be an afterthought about it and it is safe to say that I do have a few situations like that in my life. However there is one thing which I regret the most. I just wish I had enough courage back then to do what I would have done now but at that time I didn’t.

Each and every people have a different definition of love. I have read about it and seen it a thousand times in movies and everything but never really understood it.

I still don’t and that is what I regret about. I once had a chance to understand this beautiful feeling on my own but unfortunately I did not take that chance and because of that till today I haven’t have the luck in experiencing it till today.

Everyone say that love is a beautiful feeling and that everyone deserves to be in love at least once in their whole life and people also say that people get only one chance at everything which makes me wonder that if I have lost my chance to fall in love because of my lack of courage then.

There was a friend in my life who is one of the main reason which made me who I am today. I can proudly say that he was one of my precious people in my life whom I can’t replace ever. However, I am no longer friends with him today because of my stupidity. I will start from the top.

He was my friend who was always there for me whenever I needed and never really asked for anything from me in return. He never asked for anything and because of that I got used to him and up to some extent took him for granted. I am really ashamed of that and regret doing it.

That was the mistake because of which I lost my friend and my only chance to fall in love. He used to understand me so well that he would have understood everything by just looking at me once.

Everything was going fine and yet I never realised that I have taken him for granted. For me I was having an awesome life and never realised the efforts that he put behind so that I can have this awesome life. Then came the fateful day when everything changed.

That day he asked me to meet him. When I reached in the coffee house, he laid his heart out in front of me. I was so stupid that I never saw the signs. I just wished I did because then I would have handled the situation differently.

When I first heard of his proposal, I was shocked and then I declined it quite rudely which I shouldn’t have done at all. After doing that I left. I never realised at that time that what I did. By the time I realised, it was too late and he was gone from my life. I never realised that the way he used to behave was like the way a boyfriend behaves. I do realise it now and I regret it with every breathe I take.

Now I know that the way he loved me, no one can ever love me like that. For him, I was the most important person in his life. He used to get this look in his face each time when he used to see me which reminds me of the way a moon lights up when it sees the sun.

I never realised this fact then but after he left I realised exactly what he did for me. Now I regret everything I did. Now I realise the fact that I could have given him a chance and somewhere, now I feel something for him. I doubt that what I feel for him is love but I can surely say that whatever it is, is something strong because of which I haven’t able to forget it.

It has been a few years since that day but I still remember everything. If I would have handled that situation differently then I have no doubt about the fact that today we would have been the best couple ever. I guess I will never be able to discover this feeling more and will never be able to feel love at that level again. I doubt that in future he will come back to me because it has been years and who knows he may hate me today for what I did. I hate myself for what I did.

Regret is something that is part of a person’s life and I am no different in this case. Without regret a person do not shape the way they are supposed to do. In fact because of the emotion regret, human being matures. I can also say that I have matured because of that incident.

Reader Interactions

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Top Trending Essays in March 2021

- Essay on Pollution

- Essay on my School

- Summer Season

- My favourite teacher

- World heritage day quotes

- my family speech

- importance of trees essay

- autobiography of a pen

- honesty is the best policy essay

- essay on building a great india

- my favourite book essay

- essay on caa

- my favourite player

- autobiography of a river

- farewell speech for class 10 by class 9

- essay my favourite teacher 200 words

- internet influence on kids essay

- my favourite cartoon character

Brilliantly

Content & links.

Verified by Sur.ly

Essay for Students

- Essay for Class 1 to 5 Students

Scholarships for Students

- Class 1 Students Scholarship

- Class 2 Students Scholarship

- Class 3 Students Scholarship

- Class 4 Students Scholarship

- Class 5 students Scholarship

- Class 6 Students Scholarship

- Class 7 students Scholarship

- Class 8 Students Scholarship

- Class 9 Students Scholarship

- Class 10 Students Scholarship

- Class 11 Students Scholarship

- Class 12 Students Scholarship

STAY CONNECTED

- About Study Today

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

Scholarships

- Apj Abdul Kalam Scholarship

- Ashirwad Scholarship

- Bihar Scholarship

- Canara Bank Scholarship

- Colgate Scholarship

- Dr Ambedkar Scholarship

- E District Scholarship

- Epass Karnataka Scholarship

- Fair And Lovely Scholarship

- Floridas John Mckay Scholarship

- Inspire Scholarship

- Jio Scholarship

- Karnataka Minority Scholarship

- Lic Scholarship

- Maulana Azad Scholarship

- Medhavi Scholarship

- Minority Scholarship

- Moma Scholarship

- Mp Scholarship

- Muslim Minority Scholarship

- Nsp Scholarship

- Oasis Scholarship

- Obc Scholarship

- Odisha Scholarship

- Pfms Scholarship

- Post Matric Scholarship

- Pre Matric Scholarship

- Prerana Scholarship

- Prime Minister Scholarship

- Rajasthan Scholarship

- Santoor Scholarship

- Sitaram Jindal Scholarship

- Ssp Scholarship

- Swami Vivekananda Scholarship

- Ts Epass Scholarship

- Up Scholarship

- Vidhyasaarathi Scholarship

- Wbmdfc Scholarship

- West Bengal Minority Scholarship

- Click Here Now!!

Mobile Number

Have you Burn Crackers this Diwali ? Yes No

I asked hundreds of people about their biggest life decisions. Here’s what I learned

Senior Lecturer in Marketing, University of Technology Sydney

Disclosure statement

Adrian R. Camilleri does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

University of Technology Sydney provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

You make decisions all the time. Most are small. However, some are really big : they have ramifications for years or even decades. In your final moments, you might well think back on these decisions — and some you may regret.

Part of what makes big decisions so significant is how rare they are. You don’t get an opportunity to learn from your mistakes. If you want to make big decisions you won’t regret, it’s important you learn from others who have been there before.

There is a good deal of existing research into what people regret in their lives. In my current project, I decided to approach the problem from the other end and ask people about their life’s biggest decisions.

What are life’s biggest decisions?

I have spent most of my career studying what you might call small decisions: what product to buy , which portfolio to invest in , and who to hire . But none of this research was very helpful when, a few years ago, I found myself having to make some big life decisions.

To better understand what life’s biggest decisions are, I recruited 657 Americans aged between 20 and 80 years old to tell me about the ten biggest decisions in their lives so far.

Each decision was classified into one of nine categories and 58 subcategories. At the end of the survey, respondents ranked the ten decisions from biggest to smallest. You can take the survey yourself here . (If you do, your answers may help develop my research further.)

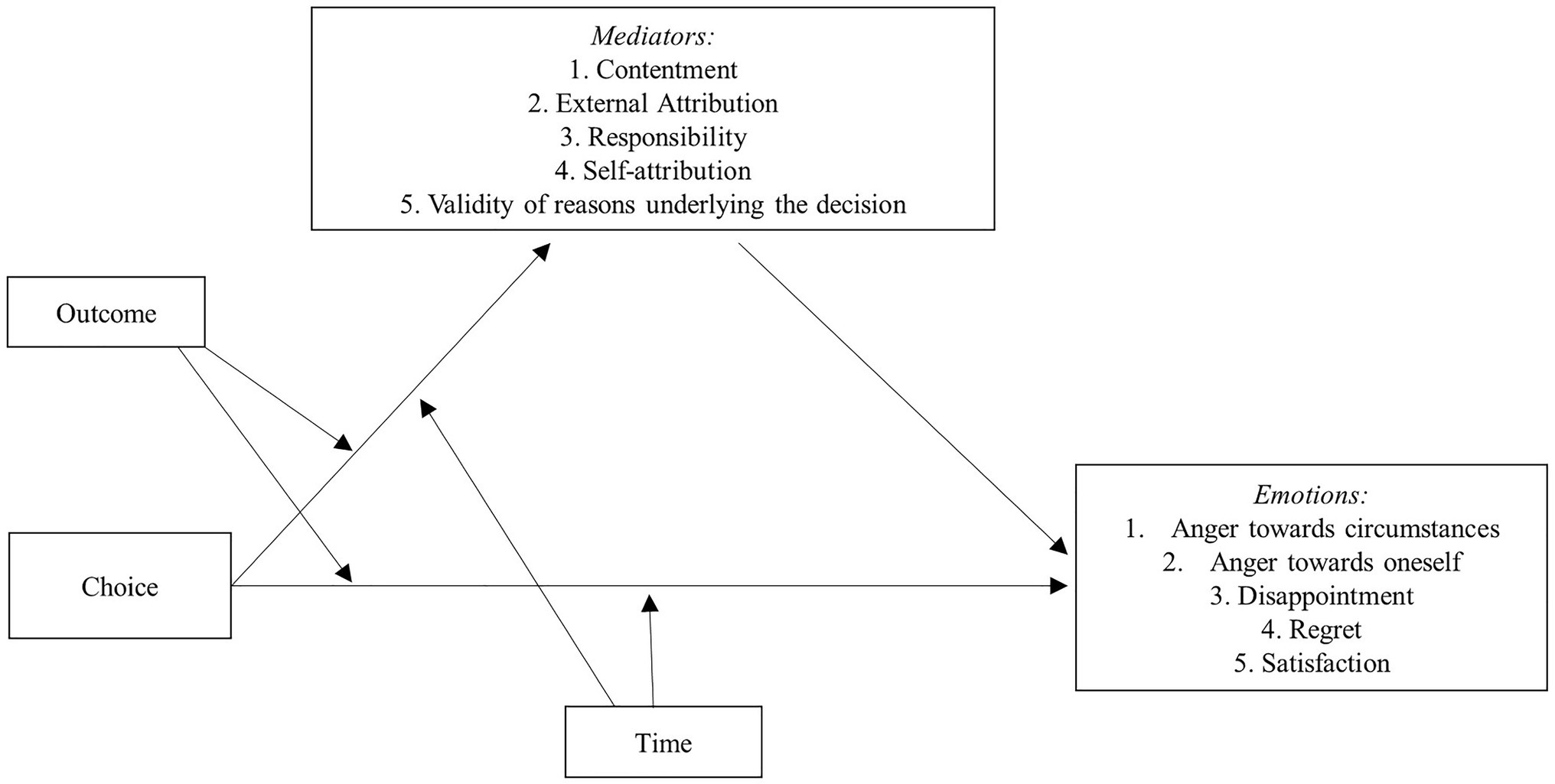

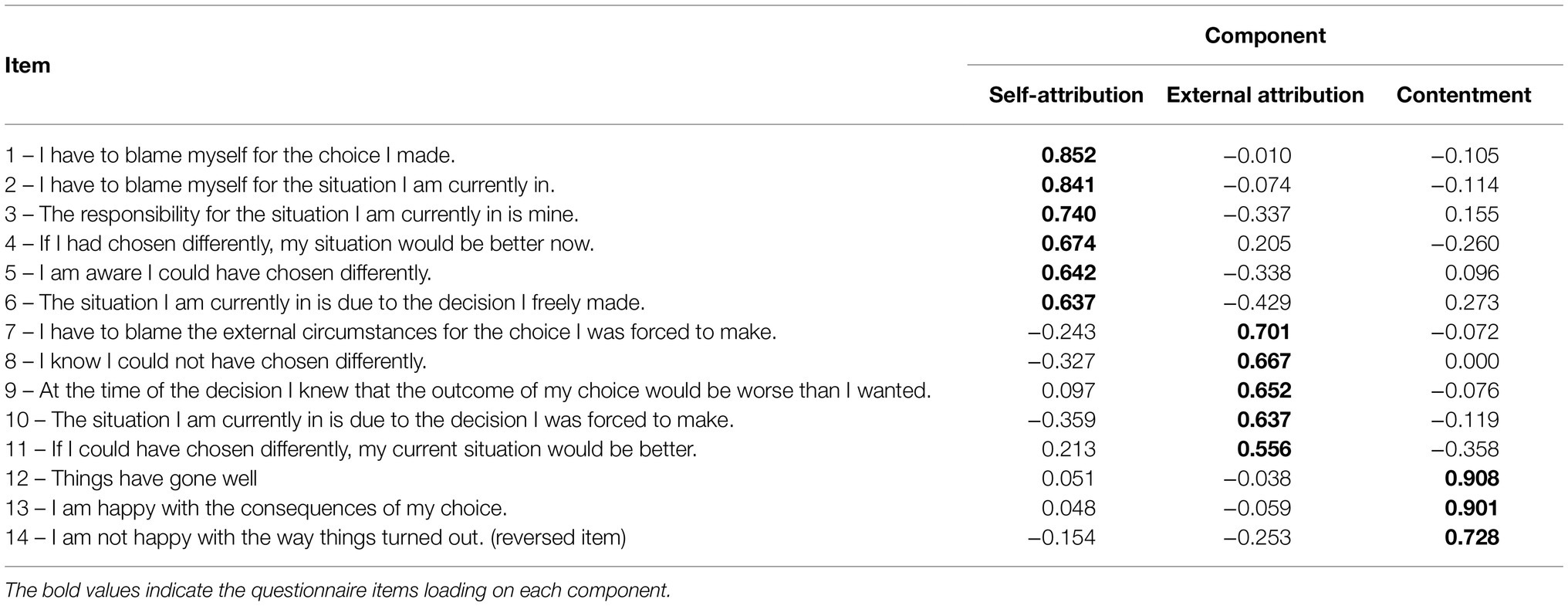

The following chart shows each of the 58 decision subcategories in terms of how often it was mentioned (along the horizontal axis) and how big the decision was considered in retrospect (along the vertical axis).

In the upper right of the chart we see decisions that are both very significant and very common. Getting married and having a child stand out clearly here.

Other fairly common big life decisions include starting a new job and pursuing a degree. Less common, but among the highest ranked life decisions, include ending a life – such as that of an unborn child or a dying parent – and engaging in self-harm.

Of course, the results depend on who you ask. Men in their 70s have different answers than women in their 30s. To explore this data more deeply, I’ve built a tool that allows you to filter these results down to specific types of respondents.

Read more: How to help take control of your brain and make better decisions

What are life’s biggest regrets?

Much can also be learned about how to make good life decisions by asking people what their biggest regrets are. Regret is a negative emotion you feel when reflecting on past decisions and wishing you had done something differently.

In 2012, Australian caregiver Bronnie Ware wrote a book about her experiences in palliative care. There were five regrets that dying people told her about most often:

- I wish I’d had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me

- I wish I hadn’t worked so hard

- I wish I’d had the courage to express my feelings

- I wish I’d stayed in touch with my friends

- I wish I had let myself be happier.

This anecdotal evidence has received support from more rigorous academic research. For example, a 2011 study asked a nationally representative sample of 270 Americans to describe one significant life regret. The six most commonly reported regrets involved romance (19.3%), family (16.9%), education (14.0%), career (13.8%), finance (9.9%), and parenting (9.0%).

Although lost loves and unfulfilling relationships were the most common regrets, there was an interesting gender difference. For women, regrets about love (romance/family) were more common than regrets about work (career/education), while the reverse was true for men.

What causes regret?

Several factors increase the chances you will feel regret.

In the long run it is inaction — deciding not to pursue something — that generates more regret . This is particularly true for males, especially when it comes to romantic relationships . If only I had asked her out, we might now be happily married.

Poor decisions produce greater regret when it is harder to justify those decisions in retrospect. I really value my friends and family so why did I leave them all behind to take up that overseas job?

Given that we are social beings, poor decisions in domains relevant to our sense of social belonging — such as romantic and family contexts — are more often regretted . Why did I break up my family by having a fling?

Regrets tend to be strongest for lost opportunities : that is, when undesirable outcomes that could have been prevented in the past can no longer be affected. I could have had a better relationship with my daughter if I had been there more often when she was growing up.

The most enduring regrets in life result from decisions that move you further from the ideal person that you want to be . I wanted to be a role model but I couldn’t put the wine bottle down.

Making big life decisions without regrets

These findings provide valuable lessons for those with big life decisions ahead, which is nearly everyone. You’re likely to have to keep making big decisions over the whole course of your life.

The most important decisions in life relate to family and friends. Spend the time getting these decisions right and then don’t let other distractions — particularly those at work — undermine these relationships.

Seize opportunities. You can apologise or change course later but you can’t time travel. Your education and experience can never be lost.

Read more: Running the risk: why experience matters when making decisions

Avoid making decisions that violate your personal values and move you away from your aspirational self. If you have good justifications for a decision now, no matter what happens, you’ll at least not regret it later.

I continue to ask people to tell me about their biggest life decisions. It’s a great way to learn about someone. Once I have collected enough stories, I hope to write a book so that we can all learn from the collective wisdom of those who have been there before.

- Decision making

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Data and Reporting Analyst

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

- Have your assignments done by seasoned writers. 24/7. Contact us:

- +1 (213) 221-0069

- [email protected]

How to Write College Essay about Regret: Reflect on Mistakes

How to Write an Engaging Essay on Personal Regret

We all experience regret, from the smallest decision to the biggest error of our life. Regret has a way of creeping up on us, making us question our actions.

It is important we avoid letting these feelings fester and grow into something worse, such as bitterness or resentment.

This post has tips that will make it easier to write a college essay on regret and make it a reflective and insightful read.

Why is Your Regret a Good Topic for College Essays?

1. interesting .

Students are often required to write essays containing personal experiences. Such an essay can be extremely interesting and exciting. Even so, describing something that has changed your life or taught you a lesson is quite a good idea.

Many students choose to write about regrets in their lives. Regret can be an excellent topic for an essay because it teaches you so much about yourself and the world around you.

2. Unchangeable facts

A regretful experience shows you that the past is unchangeable.

Regretful experiences teach people many lessons, such as dealing with failure and adapting to adverse situations.

Going through something regretful is often extremely difficult, but it usually pays off in the end because you will have learned something from it.

3. Inspiring

Sharing your regretful experience with others can also be inspiring and helpful to them. Reading about another person’s unfortunate situation can help us realize that we are not alone in our struggles.

It shows that someone is always willing to listen if we need help or advice.

4. Educative

Learning from other people’s mistakes can also help us avoid making our own mistakes. If we can learn from the mistakes of others instead of having to learn from our own mistakes, we will save ourselves a lot of trouble.

You might even want to share your regrets with friends and family.

Does your college essay matter

How to Write a College Essay about a Decision you Regret

1. explain your regret.

Write down the regretful experiences that impacted you and shaped your values, beliefs, or character.

It is important to consider your essay’s tone, style, and voice. The essay’s first sentence should be interesting, engaging, or even exciting. The last sentence should leave a strong impression on the reader.

As you draft, consider your mood. What are you feeling as you write? Are you feeling regretful? Sad? Angry? Or are you feeling happy? If so, how can you express that with language? Use sensory details and imagery to create this mood.

At the same time, think about how your audience might read or react to your story. What emotions will they feel as they read it? What images will they see in their mind as they read your essay’s opening line?

2. Write Intro and Thesis about it

When you are writing an essay and are trying to prove a point, show, or prove something. It is important to use an introduction that states what you are trying to prove.

Writing essays and papers can be very difficult to make the reader believe what you are writing about.

You can use your introduction to tell the reader how you would like them to feel about what you are saying.

The thesis statement is the brief articulation of your paper’s central argument and purpose. You might hear it referred to as simply a “thesis.” Every scholarly paper should have a thesis statement, and strong thesis statements are concise, specific, and arguable.

3. Write Why You Regret it

If you regret something you did, the best way to get over it is to write about it. In this case, you can use your college essay as an opportunity to explain the story behind your mistake and why you have learned from it.

A great regret might have changed your life. It might have influenced who you are as a person today or your future goals. It might even have affected where you end up going to college!

4. Explain the Lessons you picked

Talk about the learning experience rather than just recounting the event itself. Admissions officers read thousands of essays every year, so steer clear of anything that might come across as cliché. For instance, think about how an immigrant story can be enlightening to someone else who recently moved to the States as an immigrant.

Avoid writing about common experiences like scoring the winning goal, losing a championship game, or winning a student election. Instead, focus on specific moments that led to unique growth opportunities in your life.

Here, choose arguments from each side that you can easily oppose or prove false. You must clearly understand what points your opponent will cite and how you can refuse them.

Once again, consider that if there are many such arguments on both sides, you should choose another topic; otherwise, you risk getting stuck in the middle of the work.

What Do you Think about the Regret?

No matter what you decide to do with your life, there will always be something that you could have done differently. There will always be things that you wish you could change. You will always regret something.

Yet, there is nothing wrong with that! Regret is human nature! It is part of what makes us interesting! We are not perfect! And we all make mistakes! We are imperfect people who live in an imperfect world!

9 Examples of Regret Decisions to Write About

People make wrong choices every day. Most of the time, these decisions are small and have little consequence on their lives. But sometimes, these choices lead to serious problems such as losing a job, getting divorced, or going to jail.

If you are looking for regret decision examples to write about in your memoir, here are nine ideas:

1. Getting married too young

2. Not getting married young enough

3. Having children too soon

4. Not having children soon enough

5. Staying in an abusive relationship

6. Going out with someone you shouldn’t have dated

7. Putting off a medical procedure that ultimately led to complications or death

8. Smoking cigarettes or doing drugs over an extended period of time

9. Not putting yourself through college.

James Lotta

Related posts.

what Respondus Records

Does Respondus Record you, Sound or Screen? Is it Safe?

writing Single-spaced Essay

Single Spaced Essay in Word: What it is, Meaning and Format

Comparing Thesis and a Claim

Is a Thesis the same as a Claim: How to Write Each

- Relationships

The 6 Most Common Regrets People Experience

Research reveals life's most common regrets..

Posted June 11, 2021 | Reviewed by Devon Frye

- Intense, long-term regrets often stem from poorly made big life decisions.

- The biggest regrets tend to relate to social relationships, research suggests, while the most enduring regrets tend to be for actions not taken.

- Regrets can potentially be avoided by making decisions consistent with your values.

Have you ever made a decision that you later regretted? You’re not alone. Most people are familiar with that feeling of emptiness mixed with a hint of anger . Your mind speeds through alternative timelines in which you did something different and things turned out better.

Although many regrets are small and quickly forgotten—such as the stupid comment you made on social media —there are some regrets that endure. They become salient “sliding door” moments for which you can easily envision a better storyline for your life.

Reflecting on the most enduring regrets is important because they usually link back to big life decisions. Each of us is are in control of these decisions—so we can potentially avoid the worst regrets by having a plan. But what are the decisions we’re most likely to regret, and why?

What Do We Regret?

One way that we can learn about life’s biggest regrets is to directly ask people.

A nationally representative study, which asked 270 Americans to describe a significant life regret, found the most commonly reported regrets involved romance (19.3%), family (16.9%), education (14.0%), career (13.8%), finance (9.9%), and parenting (9.0%) (Morrison & Roese, 2011).

Another way that we can learn about life’s biggest regrets is to listen to those who care for the dying. These carers, who spend much of their time in discussion with those in their last act, have a unique perspective.

Perhaps the most well-known example is Bronnie Ware, an Australian palliative carer who wrote a book called The Top Five Regrets of the Dying . In it, she describes the five most common wishes she heard from her soon-to-depart clients.

- I wish I’d had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me. Stringently adhering to cultural norms at the expense of your own passions will result in disappointment and bitterness.

- I wish I hadn’t worked so hard . Time is non-refundable so if you spend it working, then you can’t spend it doing more meaningful things.

- I wish I’d had the courage to express my feelings . It is only by being open and honest about your thoughts and feelings can you form genuine bonds with other people.

- I wish I’d stayed in touch with my friends . It is dispiriting to be disconnected from those who truly understand you and accept you as you are.

- I wish I had let myself be happier . The expectations and opinions of others should not prevent you from being happy with who you are. Moreover, happiness can be found in the journey, not just the destination, which you often never reach.

What Leads to Regret?

A number of features increase the likelihood that a decision will lead to regret.

Feelings of regret in the long-term are more likely for decisions involving inaction; that is, choosing not to do something (Gilovich & Medvec, 1994)—for example, that overseas job you never took or that person you never had the courage to ask out. This kind of regret is enhanced by our imagination , which compares the real world with visions of the best alternative world. You can never know how things would have turned out but your mind can easily paint a rosy picture.

Decisions resulting in poor outcomes produce greater regret when it is harder to justify those decisions in retrospect (Connolly & Zeelenberg, 2002). Some decisions are made quickly, without consulting others or thinking through the options and their possible consequences. When these decisions turn out poorly, you are more likely to lament how easily you could have done something differently.

Regrets often result from decisions that move you further from the ideal version of yourself (Davidai & Gilovich, 2018). The person you want to be is grounded by your values, which reflect the things that are important to you. Some value power, others conformity , others security. Whatever it is, decisions that compromise your values expose you to the risk of regret.

There are a few important take-homes from this discussion. First, the most enduring regrets relate to social relationships. Humans have a biological need to belong and decisions that threaten this sense of belonging are particularly fraught with risk. Nurture your relationships.

Second, the most intense regrets are for decisions that are hard to justify in retrospect. To avoid regrets, it is important to make decisions that are consistent with your personal life rules and values. Even if things turn out poorly, you will know why the decision made sense for you at the time.

Third, the biggest regrets tend to relate to the things you didn’t do, perhaps because you were scared or were too busy working. It’s easier to course correct after taking action than time travel and pursue opportunities you left behind. Give things a go.

Facebook image: True Touch Lifestyle/Shutterstock

Connolly, T., & Zeelenberg, M. (2002). Regret in decision making. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11(6) , 212-216.

Davidai, S., & Gilovich, T. (2018). The ideal road not taken: The self-discrepancies involved in people’s most enduring regrets. Emotion, 18(3) , 439.

Gilovich, T., & Medvec, V. H. (1994). The temporal pattern to the experience of regret. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 67(3) , 357.

Morrison, M., & Roese, N. J. (2011). Regrets of the typical American: Findings from a nationally representative sample. Social Psychological and Personality Science , 2(6) , 576-583.

Adrian R. Camilleri, Ph.D. , is a behavioral scientist who currently works at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) Business School.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Home — Essay Samples — Life — Personal Experience — A Personal Experience of the Meaning of Regret

A Narrative About Regrets in Life

- Categories: Personal Experience Regret

About this sample

Words: 1117 |

Published: Oct 4, 2018

Words: 1117 | Pages: 2 | 6 min read

My biggest regret (essay)

Works cited.

- Davis, T. (2015). The Power of Regret: Reflection and Action. American Journal of Public Health, 105(12), e17–e19. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302907

- Roese, N. J. (2005). Counterfactual Thinking. Psychological Bulletin, 131(1), 133–167. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.1.133

- Zeelenberg, M., van Dijk, W. W., Manstead, A. S. R., & van der Pligt, J. (2000). On bad decisions and disconfirmed expectancies: The psychology of regret and disappointment. Cognition and Emotion, 14(4), 521–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999300402745

- Gilovich, T., & Medvec, V. H. (1995). The Experience of Regret: What, When, and Why. Psychological Review, 102(2), 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.102.2.379

- Linley, P. A., & Joseph, S. (2004). Positive change following trauma and adversity: A review. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17(1), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014671.27856.7e

- Ersner-Hershfield, H., Garton, M. T., Ballard, K., Samanez-Larkin, G. R., & Knutson, B. (2009). Don’t Stop Thinking About Tomorrow: Individual Differences in Future Self-Continuity Account for Saving. Judgment and Decision Making, 4(4), 280–286.

- Folkman, S., & Greer, S. (2000). Promoting psychological well-being in the face of serious illness: When theory, research and practice inform each other. Psycho-Oncology, 9(1), 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(200001/02)9:13.0.CO;2-6

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Newman, D. B., & Whiteman, M. L. (2018). Missing Out: The Effects of Missed Opportunities on Regret and Motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114(3), 437–461. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000135

- Zeelenberg, M., Nelissen, R. M. A., Breugelmans, S. M., & Pieters, R. (2008). On Emotion Specificity in Decision Making: Why Feeling Is for Doing. Judgment and Decision Making, 3(1), 18–27.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Life

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 754 words

2 pages / 1035 words

3 pages / 1282 words

5 pages / 2232 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Personal Experience

What i learned in english class? I’ve learned many things through the course of this class: how to write a good essay, how to get batter at some essays I’ve already written in the past. I’ve learned how to locate my resources to [...]

It never can get better than getting involved in your own community. Just to know that you are helping your community become a better place. One action at a time. From picking up a little piece of garbage to starting a [...]

This is a short story about myself. My essay is particularly about me in third grade. In third grade, my family and I moved to Morgan, Utah. I had to go to a different school, where I knew nobody. I had to make new [...]

In the context of my autobiography essay, it's essential to understand my background. My name is Tharun, and I was born on December 18, 2004, in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. My parents are Suresh and Karolina. Unfortunately, both of [...]

It was Saturday, a busy day for me, I got up earlier that ay so as to pack up luggage. It was a little confuse because I was going to travel somewhere I have never heard of before_Tamanart, a small village which is 80 km to [...]

Obstacles are often faced by each one of us in our day to day life, as we make each and every effort to reach the pinnacle of success. One must strive hard with great perseverance and resolution besides being very challenging [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

It’s Time to Make Peace with Your Regrets

- Vasundhara Sawhney

Learn to leave things in the past — where they happened.

For some of us, good things have happened this past year. We’ve been able to spend more time with loved ones, get back into hobbies, and learn new things. But for others, so much has been lost — in work, in social capital, and in life. Many of us are also feeling regret.

- Regret is an emotion we’re all familiar with and it surfaces with action as well as inaction. We tend to feel regret about the things we haven’t done (missed opportunities) more intensely than regret about the things we did do.

- Regret, like all difficult emotions, is neither intrinsically good nor bad. It is the actions we carry out in response to feeling regret that impact our long-term wellbeing.

- To cope with regret and leave the past where it happened we need to: 1) Recognize our feelings and let them out. 2) Look at the past with gratitude rather than the lost opportunity costs. 3) Make regret productive by thinking about what we value and what actions we can take to get closer to the things that matter to us.

Where your work meets your life. See more from Ascend here .

Do we still need to talk about the many ways this pandemic has impacted our lives? I think I’m past that stage. But I do occasionally sit with myself and feel sad, mostly for something that I’ve lost: time. While chatting with a friend recently — over Zoom, of course — we spoke about how we had made so many plans when 2020 began: We set goals for our careers, booked elaborate travel arrangements, and were prepared to celebrate milestone birthdays, including the day I would meet my nephew and my sister’s first child.

- Vasundhara Sawhney is a senior editor at Harvard Business Review.

Partner Center

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Articles & More

How regrets can help you make better decisions, a new book explains what makes people prone to regret and how it affects our lives, for better and worse..

Have you ever regretted something you did or didn’t do in life?

If you’ve lived a long life, you probably carry many regrets, large and small. Some of my own regrets relate to my career ( why did I never apply to medical school? ), past relationships ( why did I lose a good friend over a small spat? ), and parenting ( why didn’t I respond well to my son’s anxiety? ). No matter the regret, it’s hard not to wonder how things might have turned out if I’d only made a different—and better—choice at the time.

Ruminating on past mistakes is a downer and can lead to depression or anxiety if it continues unabated. But a new book by psychologist Robert Leahy, If Only…Finding Freedom from Regret , suggests that regrets don’t always have to bog you down. If you understand how regrets work, recognize their effect on your decision making, and find ways to manage life’s inevitable disappointments, you can suffer less from regret and, instead, use your regrets as helpful guideposts for your life.

“Regret is a part of life, but it doesn’t have to take over and hijack you,” he writes.

The nature of regret

Regret can come in different forms—for something we did (like overeating or hurting our loved one) or something we didn’t do (like not graduating from college or not asking someone out on a date). Most people have a mixture of both types, though the latter tends to make us feel worse, writes Leahy.

According to research , the most common sources of regret involve our education, career, romance, and parenting (in that order). That’s because we tend to regret things that reflect bigger concerns and opportunities in life, rather than what we ate for breakfast.

Culture can affect how people experience regret, too, with people from more individualistic cultures usually having more regrets about their personal situation (like achievement or career) and those in collectivist cultures having more regrets about their relationships. And women and men differ some in how they experience regret, with women typically regretting romantic and sexual relationships more than men and men regretting inaction more than action.

Regret is associated with unpleasant emotions, like sadness, disappointment, guilt, and shame. But people also regard it as one of the most beneficial negative emotions, because it can be instructive. For example, if we regret how we behaved the last time we drank too much, we’re less likely to order a third round the next time we’re at the bar. Or, if we regret yelling at our child when angry, we may take a breath the next time we’re upset and respond with compassion.

Our regrets can teach us about ourselves, help us to avoid repeating mistakes, and encourage us to make better decisions in the future. On the other hand, if we use our regrets to beat ourselves up, or if we ignore them completely, they will not lead to growth. The key is finding the right balance, says Leahy.

“Regret doesn’t have to lead directly to self-recrimination,” he writes. But “never feeling regret is not a sign of wisdom or righteousness. It may be a sign you don’t learn from your mistakes.”

Why some people suffer from regret more

Some of us are more prone to regret than others, and Leahy provides multiple questionnaires within his book to help you identify where you fall on that scale. Though there is no way to eliminate regret completely—and the world would be worse if we did—there are factors that increase our chances of experiencing regret in a more negative way and suffering from it, says Leahy. Here are some of those risk factors.

Not tolerating ambivalence. Many life choices have pros and cons, and there are no guarantees about the future. But, if you can’t stand uncertainty, you are bound to avoid making hard choices, leaving you vulnerable to later regrets.

Falling prey to biases. We all have cognitive biases, but some influence regret more than others. If you suffer a lot from negativity bias (discounting or not even seeing the positives in your life), black-and-white thinking (thinking things are either all good or all bad), or catastrophizing (thinking that if something goes wrong, you won’t be able to handle it), it’s bound to affect how much you suffer regret.

Worrying about “buyer’s remorse” or how bad we’ll feel in the future. If you’re the kind of person who often anticipates feeling awful for making a choice, it may keep you from deciding on a course of action that could bring you happiness, increasing the potential for regret.

Having too many choices. “Regret is an opportunity emotion—the more opportunity we see, the more likely we are to regret something,” writes Leahy. For example, a college graduate with multiple job offers might regret taking one over another, especially if it doesn’t pan out. Having too many choices increases your potential for making the “wrong” one.

Being a perfectionist. If you expect to have an ideal, happy life all of the time and are not easily satisfied, you will be more prone to regret. “Maximizers” (people who seek out optimal outcomes) tend to feel more regret than “satisficers” (people who are content with good-enough outcomes), unless they can take steps to lessen their maximizing tendencies.

How regret can guide our decisions

“Regret is a possible element of any decision that we make,” writes Leahy. “But the likelihood that you will regret your decisions will depend on how you think about making your decisions and how you cope with living with the result.”

If you’re someone who lets past regrets fester in your mind, Leahy recommends that you fight against irrational thinking and think more realistically about where you are in life. He suggests using approaches from cognitive-behavioral therapy to question your assumptions. Here are some of his tips.

Remember that you don’t know things would have turned out better. If you imagine your life would have been better “if only…,” keep in mind that your assumption is not based on real evidence. Instead of focusing on where you might have been, turn toward the future and remember it can change based on the choices you make now.

Focus on the positive aspects of your current life , to balance out the negative feelings that come with regret. Your negativity bias can keep you preoccupied with what’s wrong rather than what’s right. So, it’s a good idea to practice gratitude for the good in your life—even for the small, simple things.

Don’t forget that sometimes things don’t turn out the way you wanted them to , even with your most thoughtful planning. Life can hand you lemons, but that’s not necessarily your fault. You cannot be omniscient; so, you need to accept that sometimes you will regret your choices. But that doesn’t mean you should criticize yourself endlessly. Better to learn from your mistakes than to punish yourself.

Accept tradeoffs and compromises. Not everything has to turn out just the way you wanted it to. You will stymie your progress if you insist otherwise and make yourself miserable in the process. So, aim to be a satisficer rather than a maximizer.

Overall, Leahy advises that, once you’ve learned whatever lessons regret can teach you, you can let go of unrealistic expectations about what might have been, enjoy your life as it is, and start planning for a better future.

“Look around you at what is in the present moment and hold on to it with a warm embrace,” he writes. “Because your regrets will only keep you from what you have and who you are and trap you in a fictional world that never was—and never could have been.”

About the Author

Jill Suttie

Jill Suttie, Psy.D. , is Greater Good ’s former book review editor and now serves as a staff writer and contributing editor for the magazine. She received her doctorate of psychology from the University of San Francisco in 1998 and was a psychologist in private practice before coming to Greater Good .

You May Also Enjoy

This article — and everything on this site — is funded by readers like you.

Become a subscribing member today. Help us continue to bring “the science of a meaningful life” to you and to millions around the globe.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Cope With Regret

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Daniel B. Block, MD, is an award-winning, board-certified psychiatrist who operates a private practice in Pennsylvania.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/block-8924ca72ff94426d940e8f7e639e3942.jpg)

Ridvan_celik / Getty Images

What Is Regret?

Tips for coping with regret, what causes regret, what do people regret most, impact of regret.

Life is full of choices and paths not taken, so it isn’t surprising that people sometimes feel regret over both the decisions they made and the ones they didn’t.

Regret can be an incredibly painful emotion. While rooted in feelings of contrition, disappointment, guilt, or remorse for things that have happened in the past, such feelings can have a powerful influence over your life in the here and now. The problem is that when you are feeling regret over past choices or past mistakes, you might sometimes miss out on the joys of the present moment.

Learn more about the power of regret, what causes it, and what you can do to cope.

Get Help Now

We've tried, tested, and written unbiased reviews of the best online therapy programs including Talkspace, BetterHelp, and ReGain. Find out which option is the best for you.

Regret is defined as an aversive emotion focused on the belief that some event from the past could have been changed in order to produce a more desirable outcome.

It is a type of counterfactual thinking , which involves imagining the ways your life might have gone differently. Sometimes counterfactual thinking might mean appreciating your good luck at avoiding disaster, but at other times it focuses on being disappointed or regretful.

Characteristics of Regret

- It focuses on the past

- It is a negative, aversive emotion

- It focuses on aspects of the self

- It leads to upward comparisons

- It often involves self-blame

The reason why regret feels so awful is because, by its nature, it implies that there is something you could have done, some choice you could have made, or some action you might have taken that would have made something good happen or avoided something terrible.

Regret isn't just wishing events had gone differently; it also involves an inherent aspect of self-blame and even guilt.

Regret is a difficult thing to feel, but some experts suggest it can also have a positive impact if you cope with it well and allow it to help you make better choices going forward.

"No regrets" has become a popular mantra for many, signifying the idea that regret is a waste of time and energy. It's a worldview repeated in popular culture and touted by everyone from social media influencers to celebrities to self-help gurus.

And, according to psychologist Daniel Pink, author of "The Power of Regret," it is 100% wrong. He suggests that regret is not only perfectly normal, it can even be healthy. According to Pink, regret can act as a source of valuable information. When utilized well, it can guide, motivate, and inspire you to make better choices in the future.

While you can’t avoid regret, there are things that you can do to minimize these feelings. Or take the negativity out of these feelings and turn your regrets into opportunities for growth and change.

Regret is most often characterized as a negative emotion , but it can serve an important function and even act as a positive force in your life at times. For example, regret can be motivating. It can drive you to overcome past mistakes or take action to correct them

Research has also found that both experienced regret and anticipated regret can influence the decisions that you make in the future. Efforts to avoid future regrets can help you make better decisions .

Practice Self-Acceptance

Acknowledging and accepting what you are feeling is essential. When you accept yourself and what you are feeling, you are able to recognize that your value isn't defined by your mistakes or failures.

Accepting yourself and your feelings does not mean you don't want to change things or do better. It just means that you are able to recognize that you are always learning, changing, and growing.

Remind yourself that the events of the past don't determine your future, and you are capable of making better choices in the future.

Forgive Yourself

Because regret involves a component of guilt and self-recrimination, finding ways to forgive yourself can help relieve some of the negative feelings associated with regret. Forgiving yourself involves making a deliberate choice to let go of the anger, resentment, or disappointment you feel about yourself.

Accepting your mistakes is one part of this process, but forgiveness also requires you to practice self-compassion. Rather than punishing yourself for mistakes, treat yourself with the same kindness and forgiveness that you would show a loved one.

You can do this by taking responsibility for what happened, expressing remorse for your errors, and taking action to make amends. You might not be able to change the past, but taking steps to do better in the future can help you forgive yourself and move forward instead of looking back.

Apologize for Mistakes

In addition to forgiving yourself, you may find it helpful to apologize to other people who may have also been affected. This can be particularly important if your regrets are centered on conflicts in relationships or other problems that have caused emotional distress and pain.

A sincere apology can let the other person know that you feel remorse about what happened and that you empathize with their feelings.

Take Action

One way to help cope with feelings of regret is to use those experiences to fuel future action. Consider what you might have changed and done differently, but instead of ruminating over what cannot be changed, reframe it as a learning opportunity that will allow you to make better choices in the future.

In reality, you may not have been capable of making a "better" choice in the past simply because you didn't have the knowledge, experience, or foresight to predict the outcome. You made the choice you did based on what you knew then and the tools and information you had at your disposal.

Remind yourself that now that because of what you learned in the past, you now have the knowledge you need to make a better choice the next time you encounter a similar dilemma.

Remember that the events of the past don't determine your future, and you are capable of making better choices in the future.

Cognitive reframing is a strategy that can help you change your mindset and shift how you think about a situation. This approach can help you change your perspective, show compassion for yourself, and validate the emotions that you are feeling. It can also help you to see situations in a more positive way and overcome some of the cognitive distortions that often play a role in negative thinking .

As Pink notes in his book, the popular “no regrets’ philosophy isn’t so much about denying regret as it is about reframing it, or as he calls it, optimizing it. It is an acknowledgment that mistakes of the past have shaped who you are today.

It is about reframing that regret and seeing it as a learning opportunity that helps build resilience and wisdom. It’s not that you wouldn’t change past decisions if you could–it’s about recognizing that those choices helped you learn and can help you make better decisions in the future.

Changing how you think about things that have happened in the past can also help you see regret in a different way. Instead of dwelling on negative feelings, you can see it as information that can guide you going forward.

Anytime you are required to make a choice, there is an opportunity for regret. Did you make the right decision? Could things have turned out better? Would you be happier if you’d chosen differently?

Such regrets sometimes center on the mundane (like whether you should have had the soup or the sandwich for lunch) to the life-altering (like whether you should have picked a different career or married a different partner).

But what exactly causes people to regret some decisions and not others? According to researchers, opportunity itself plays a major role.

If the decision was out of your hands or largely influenced by outside forces, you're less likely to feel regretful about what happened. The reason for this is that processes such as cognitive dissonance and rationalization kick in to unconsciously minimize your personal responsibility for the outcome.

For example, if you buy an item knowing you cannot return it, you're less likely to regret your purchase. According to researchers, people often unconsciously suppress or distort many of life's daily regrets without even realizing that it is happening.

It is when you have more opportunities to change your mind, such as when you know you can return an item and pick something different, that you are more likely to wish you had chosen differently. Researchers refer to this as the opportunity principle, which suggests that more opportunity leads to more regrets.

Control and opportunity can play a role in whether or not you experience regret. When your ability to control the outcome is out of your hands, you may be less likely to regret your choice. But when many different options are present, you're more likely to regret your choice.

In an older study published in 2008, researchers analyzed archival data to learn more about which areas were most likely to trigger feelings of regret. The results indicated that the six most common regrets were centered in the areas of education, career, romance, parenting, the self, and leisure. Beyond those top six, regrets then centered on the topics of finance, family, health, friends, spirituality, and community.

Interestingly, people are often more likely to regret inaction than action. For example, you're more likely to regret not choosing a certain career or not asking out someone you were interested in than to feel regret over the job and partner you did choose. This is because actions not taken are more subject to imagined outcomes.

The consequences of the actions you did take are set in stone and readily apparent, but the ones you didn't take seem like boundless opportunities wasted. In other words, the perceived gains of the choices you didn’t make seem to outweigh the actual consequences of your actions, so the sting of regret for missed opportunities looms much larger in your mind.

Common regrets center on areas of life including education, career, and romance. In addition to regretting choices, people often regret not taking certain actions in the past.

Regret can take both a physical and emotional toll on your body and mind. Feelings of regret can often lead to physical symptoms such as muscle tension, sleep disturbances, changes in appetite, headaches, muscle pain, joint pain, and chronic stress .

Studies have shown that persistent regret can increase your risk of problems with breathing issues, chest pain, joint pain, and poorer overall health.

Constantly ruminating on past regret can lead to symptoms such as anxiety, depression, poor self-esteem , helplessness , and feelings of hopelessness .

Fear of future regret can also affect your behavior. Anticipated regret, or the belief that you will regret something in the future, can also play a role in risk-taking and health-related behaviors you engage in today.

When people think taking an action will lead to greater regret, they are less likely to engage in risky behavior. And when people think that not taking action will lead to feelings of regret (such as not taking care of their health or not engaging in regular exercise), they become more likely to take steps to avoid those anticipated regrets.

Studies have also found that concern about anticipated regret can influence the decisions that people make on the behalf of others. When people are worried that people are going to be disappointed or regretful, they are more likely to make more conservative choices.

Coping poorly with regret can lead to stress and emotional pain. It can also affect your future behavior. Anticipated regret often leads people to avoid risky behavior or engage in certain actions in order to avoid consequences that they might eventually regret.

Regret is an aversive emotion that can be difficult to overcome. "Accept life, and you must accept regret," said the philosopher Henri-Frédéric Amiel. While regret is an unavoidable consequence of living life and making choices, you can find ways to cope with these feelings and even turn them into opportunities for growth.

Learning to accept your feelings, forgiving yourself for mistakes, and taking steps to learn from your experiences can help minimize many of the negative feelings associated with regret. While you may not truly be able to live life with "no regrets," you can change how you think about the things you might have changed and learn to focus on the present moment instead of ruminating over the past.

Roese NJ, Summerville A. What we regret most... and why . Pers Soc Psychol Bull . 2005;31(9):1273-1285. doi:10.1177/0146167205274693

Pink D. The Power of Regret .

Joseph-Williams N, Edwards A, Elwyn G. The importance and complexity of regret in the measurement of 'good' decisions: a systematic review and a content analysis of existing assessment instruments . Health Expect . 2011;14(1):59-83. doi:10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00621.x

Cornish MA, Wade NG. A therapeutic model of self-forgiveness with intervention strategies for counselors . Journal of Counseling & Development . 2015;93(1):96-104. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2015.00185.x

Papé L, Martinez LF. Past and future regret and missed opportunities: an experimental approach on separate evaluation and different time frames . Psicol Reflex Crit . 2017;30(1):20. doi:10.1186/s41155-017-0074-8

Gilovich T, Medvec VH, Chen S. Commission, omission, and dissonance reduction: Coping with the “Monty Hall” problem . Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1995;21:182–190. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00353

Wrosch C, Bauer I, Miller GE, Lupien S. Regret intensity, diurnal cortisol secretion, and physical health in older individuals: Evidence for directional effects and protective factors . Psychology and Aging . 2007;22(2):319-330. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.22.2.319

Brewer NT, DeFrank JT, Gilkey MB. Anticipated regret and health behavior: A meta-analysis . Health Psychol . 2016;35(11):1264-1275. doi:10.1037/hea0000294

Kumano S, Hamilton A, Bahrami B. The role of anticipated regret in choosing for others . Sci Rep . 2021;11(1):12557. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-91635-z

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Personal Narrative Essay about Regrets

Regret is the emotion of wishing one had made a different decision because the consequence of the decision was unfavorable. I've felt the emotion of regret many times have you?

Regret is a normal and common emotion everyone has when making decisions. No matter whether you sit back and think before making a decision or just jump to it, there's still an equal chance of you regretting your decision later.

Nobody's perfect, everyone has once made a decision that made them feel a sort of shame, dissatisfaction, disappointment , and even maybe remorse because of past episodes. A past episode that constantly replays in my head and makes me so ashamed and disappointed in myself is the time in middle school me and my best friend were finally accepted in the big friend group with our other school mates . We were so excited it was like our middle school experience was finally going to happen. At times me and my best friend would see how the friend group would constantly mistreat others but we didn't speak up we just let it be but at one point there was no one really left for the friend group to mistreat so they started to turn on my bestfriend and it hurt to see them mistreat the girl that has been my side since day one and I've always had her back but this time it was different because I was so worried about me being bullied next So when my best friend had to suffer alone, I stood quietly.

Although my bestfriend and I are still friends and she always tells me it was fine that I didn't defend her and she says she forgives me every time I apologize for it, that doesn't change the fact that it happened. Looking back at it now there are so many things I could have done to help her. One thing that i shouldve have done was be less selfless. I was too worried about myself being mistreated by the friend group. I turned my back when my friend needed me the most. If I would have just defended her yes i would have gotten mistreated too but at least she wouldn't have been alone.

I've definitely grown a lot since then and it's now more rare if I'm sitting back while something wrong is happening right in front of me. From that episode I definitely learned to speak up for what's right instead of agreeing with the bad things others were doing. Just the way I turned my back on my best friend just for others validation and so that I wouldn't get mistreated too just makes me feel such shame now. I will never not forget this and I know she won't either but that's the way it is. Some regrets can be forgotten if they're simple and even if they're not simple it's fine because no matter what you do differently next time there's still a chance of you regretting it.

Yes, even though regret is an emotion that doesn't always feel too good and at times makes you feel disappointed in yourself at the end of the time regret helps us learn and it makes us realize we need to think carefully when making decisions and it helps us grow and learn from our mistakes.

Related Samples

- Moving to America Essay Example

- Essay Sample on What is Happiness and How is It Measured?

- The Rewarding Truth Goodbyes Hold. My Life Experience Essay Example

- The Benefits of Hard Work Essay Example

- My Personal Growth Essay Example

- Grasping Happiness (Argumentative Essay Sample)

- WOMS 302 - WOMEN IN MUSIC (Evaluation Essay)

- Personal Narrative Essay: Dance Is My Harmony

- Why Is It Important Not to Lose Hope Essay Example

- The Greatest Showman Review. Essay on Circus Industry

Didn't find the perfect sample?

You can order a custom paper by our expert writers

clock This article was published more than 2 years ago

How to deal with regret and forgive yourself for making imperfect decisions

During the past year, we have had to make consequential decisions, often based on insufficient information and amid unparalleled uncertainty. These conditions are ripe for generating one of the most common emotions that I see in my psychology practice: regret.

Many of my patients struggle with the results of pandemic-related decisions. Some regret decisions they made about the care of their aging relatives. Others are haunted by the knowledge that they inadvertently transmitted covid-19 to people they love. Parents who decided to keep their kids at home now feel guilty because their children struggle with mental health issues.

Barbara Roberts, clinical psychologist and director of wellness and clinical services for the Washington Football Team, said her clients expressed regrets during the pandemic about being “stuck in a bad relationship, or that they hadn’t taken a trip or done something important to them when they had a chance.”

Christine Le, a 27-year-old from San Francisco, is kicking herself for not getting enough done during the past 15 months. “What I regret the most during the pandemic is that I didn’t focus more on self-development with the extra amount of time that I had,” she said. “I should have put more time into writing my blog, self-care and strengthening my relationships with others.”

A study from Turkey , which is yet to be peer reviewed, suggests that regret is a common issue tied to the pandemic. But it is an emotion that can lead people to spiral into a pernicious mix of shame, anger and depression, unless they take steps to prevent that.

Find time you didn’t know you had with A Better Week, a 7-day email course

Of course, regret was a pervasive emotion long before the pandemic. In one study, it was found to be the second-most frequently mentioned emotion in everyday conversation (after love). Romantic regrets tend to be most common, and those centered on social relationships in general are felt more strongly than nonsocial ones — lending credence to the saying that nobody on their deathbed wishes they had spent more time working.

Studies have found that a high level of regret is related to depression , anxiety and worse sleep and problem-solving. Most people feel a pang of regretted action (I wish I hadn’t done that!) quickly and intensely, but regret over inaction (I should have done that) lingers longer . When looking back on life, we tend to most regret not taking chances and opportunities that could have brought us closer to being the person we want to be.

If you tend to get stuck on the things you could have done better in the past, here are strategies to help shift your focus to a better future.

Accept reality and your emotions

Regret is uncomfortable, so we often try to mentally run away from it. But denial, distraction or suppression do not work for long — and the pain returns with a vengeance. For example, drinking heavily each evening to drown out your guilt about going on a pandemic vacation that led to your family contracting the coronavirus will amplify the regret in the long run.

First, try to acknowledge the full reality of what is regretted, including your role in it. As you open up to regret, you might notice different emotions coming to the surface.

“Try to identify and name what you are feeling — name it to tame it,” suggested Chris Germer, clinical psychologist and co-author of “ The Mindful Path to Self-Compassion: Freeing Yourself from Destructive Thoughts and Emotions .” “Notice the body sensations associated with guilt, remorse, anger, sadness, shame, and see if you can make space for them.”

Tell us about the hardest parts of life after social distancing

To increase your emotion vocabulary, try using an emotion wheel . Observe the feelings nonjudgmentally, with curiosity, letting them ebb and flow — this is an essence of mindfulness.

You also can observe any judgments your mind is making about these feelings and sensations. Allowing both emotions and thoughts to be there, without fighting them or buying into them, teaches you that you can tolerate the pain without identifying with it. Strength can be cultivated through vulnerability.

Practice self-compassion

A prominent feature of regret, especially the kind that sticks around, is rumination about all the different ways you could have made a better decision or action. This obsessing can turn guilt (an emotion that stems from believing you did something wrong) into shame (the belief that you are wrong or defective).

Although guilt can motivate rectifying action, shame invites wallowing in self-reproach and self-criticism. “Unfortunately, many believe that punishing yourself will lead to positive change. But nothing can be further from the truth,” said Germer.

Research shows that self-compassion is related to the pursuit of important goals, lower procrastination and less fear of failure.

“Self-blame shuts down learning centers in the brain,” said Tara Brach, a Washington-area meditation teacher, clinical psychologist and author of “ Radical Acceptance .” It hardens your heart and isolates you. It doesn’t make what happened okay, nor does it improve your future.”

Instead, remember that to be human is to make mistakes. “Actively offer yourself forgiveness by, for example, whispering ‘forgiven’ or putting a hand on your heart. If that seems like a tall order, having an intention to forgive can be a start,” said Brach.

In addition to engaging in whatever self-care routine works for you (exercise, meditation, spending time outdoors), other suggestions for fostering self-compassion include embracing yourself, asking yourself what you would say to a friend in a similar situation, or trying to channel the emotions of someone who deeply cares about you. You could also reach out to loving people in real life; studies found that sharing regret with others can bring you closer to people .

Make amends when possible

Accepting reality, and yourself, allows you to face your responsibility and take corrective action. “After you acknowledge what happened, own it, do what needs doing, and seek forgiveness if possible,” said Marine Corps Maj. Thomas Schueman, who teaches courses focused on moral injury, homecoming and belonging at the U.S. Naval Academy, and who led troops in two deployments, losing some of them in action.

Niche Brislane, 32, a farmer from Max, Neb., said she has worked to minimize the damage that resulted from bad choices she made as a young woman. “I made bad financial, relationship, and education decisions, and failed to listen to well-meaning people who had more life experience than me,” she said. “I have salvaged what could be salvaged, and I’m now in a better place.”

Even if you cannot do anything concrete to repair the situation, you can focus on behaving with integrity going forward. “If you’re solely focused on past regrets, you are unable to be a loving and caring person now and contribute to the society the way we’d like,” said Russ Harris, therapist and author of “ The Reality Slap ” from Melbourne, Australia.

Expand your thinking

The pandemic brought extreme uncertainty, danger and the disruption of routines. “When you are scared, your thinking and decision-making are affected. You become more reactive and less deliberate,” said Brach. “And we have all been in a constant state of fear for more than a year.”

It is thus not surprising that your decision-making was not at its best, so give yourself a break. “Realize that what happened was a result of many factors and conditions,” said Germer. “And you did the best that you could in that moment, with the information available to you.”

Challenge the unhelpful thinking patterns that can magnify regret. Some of the common patterns tackled in cognitive therapy include:

● All-or-nothing thinking: “If I couldn’t protect my kids from getting depressed, I am a bad parent.”

● Catastrophizing: “This mistake has doomed me forever!”

● Minimizing the positives: “I forgot my friend’s birthday,” while disregarding all the ways you’ve shown her care and kindness over the years.

● Fortunetelling: “I should have known better,” even when it was impossible to predict what was coming.

Learn from your regrets

Regret provides us with unprecedented opportunities for learning and improving. Roberts recommends always asking yourself, “What can I learn from this experience?” and “How can I do better next time?”

Harris suggests that regret can reveal what matters to you most and what kind of person you want to be. For example, you wouldn’t feel bad about not finishing your part of a project on time if you didn’t care about your teammates and take pride in your work. “When you are not consumed by fighting regret or by self-critical judgments and rumination, you can learn a lot about yourself,” Harris said.

“Productive regret is a teacher,” said Brach. “You learn how to turn failures into feedback that helps you improve your decisions and behaviors in the future. You learn to make good decisions by making bad ones.” Research indicates that exploring regrets is related to the search for meaning in life and psychological growth .

“Real tragedy is when you don’t find meaning in your mistakes,” Schueman said. “When you find gratitude for what you learned, growth happens.”

Do you have questions about home improvement or homeownership?

Jelena Kecmanovic is the founding director of the Arlington/DC Behavior Therapy Institute and an adjunct professor of psychology at Georgetown University. Find her @DrKpsychologist.

Your Life at Home

The Post’s best advice for living during the pandemic.

Health & Wellness: What to know before your vaccine appointment | Creative coping tips | What to do about Zoom fatigue

Newsletter: Sign up for Eat Voraciously — one quick, adaptable and creative recipe in your inbox every Monday through Thursday.

Parenting: Guidance for vaccinated parents and unvaccinated kids | Preparing kids for “the return” | Pandemic decision fatigue

Food: Dinner in Minutes | Use the library as a valuable (and free) resource for cookbooks, kitchen tools and more

Arts & Entertainment: Ten TV shows with jaw-dropping twists | Give this folk rock duo 27 minutes. They’ll give you a musically heartbreaking world.

Home & Garden: Setting up a home workout space | How to help plants thrive in spring | Solutions for stains and scratches

Travel: Vaccines and summer travel — what families need to know | Take an overnight trip with your two-wheeled vehicle

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Thinking Skills

- Decision Making

How to Stop Regretting Your Decisions

Last Updated: September 21, 2022 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Trudi Griffin, LPC, MS . Trudi Griffin is a Licensed Professional Counselor in Wisconsin specializing in Addictions and Mental Health. She provides therapy to people who struggle with addictions, mental health, and trauma in community health settings and private practice. She received her MS in Clinical Mental Health Counseling from Marquette University in 2011. There are 12 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 257,188 times.

Regret is something we all experience from time to time. While regret has some benefits to your personal growth and development, ruminating too long on the past can have negative impacts on your physical and emotional health. There are a variety of steps you can take, from altering your mindset to changing your lifestyle, that help you cope with regret and ultimately leave it behind.

Altering Your Mindset

- Regret is negative feelings of guilt, sadness, or anger over past decisions. Everyone experiences regret at some point in life, especially young people, but regret becomes a problem when ruminating over past mistakes results in disengagement with your life, career, and personal relationships. [1] X Research source