Find anything you save across the site in your account

13 Stunning Examples of Reflective Architecture

By Jessica Cherner

Though most appreciate the styles of baroque, gothic, and neoclassical, there’s something enticing about buildings—whether they be residences, offices, museums, or public works of art —that boast a more modern edge. And, of course, technological developments in architecture have allowed today’s designs to be all the more forward-thinking. That said, one material that instantly lends itself to modernity is reflective glass. Whether it’s the element of mystery or the aesthetic simplicity of mirrors, architects around the world are cladding their masterpieces in reflective glass, and people are loving it.

From quaint villages in Belgium to densely populated metropolises in the U.S., the world is chock-full of eye-catching reflective architecture. Here are 13 examples to reignite anyone’s love of shiny objects.

One World Trade (New York City)

Aside from 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, One World Trade is among the United States’ most famous addresses. Built in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attack in which nearly 3,000 Americans lost their lives, the Freedom Tower (as it’s also called) is the tallest building in the country and the Western Hemisphere. Today, while the soaring tower is a landmark that signifies the unbreakable human will to live, it wasn’t exactly well-received when it was built back in 2006. That said, over the last few years, the downtown landmark has become a well-loved building by the city and its residents alike.

Elbphilharmonie Hamburg (Hamburg, Germany)

One of the world’s largest concert halls, Elbphilharmonie Hamburg (appropriately nicknamed Elbphi), was built in 2017 by the architects at Herzog & de Meuron. The groundbreaking project, which looks like a hoisted glass sail in the middle of the Elbe River, cost a whopping €866 million to construct. Yet, some may consider it money well spent, as it’s become one of the most flocked-to musical venues in the world. Though it arrived years late and millions of euros over budget, it’s practically paying for itself with more than three million concert-goers since it opened.

Maraya Concert Hall (Al Atheeb, Saudi Arabia)

Elphi in Hamburg, Germany, may be one of the biggest music venues in the world, but Maraya Concert Hall in Al Atheeb, Saudi Arabia, actually sets that record. Set within the city’s desert landscape, the mirrored structure looks almost like a mirage. It may look simple—a rectangular box wrapped in giant mirrored panels—but the Maraya, designed by Milan studio Giò Forma was a massive undertaking that only further emphasized the cultural richness of the city. The concert hall is also home to an immersive theater and an interactive exhibition.

Steirereck (Wien, Austria)

Steirereck in Wien, Austria, may look more like an art installation than a restaurant, but with two Michelin stars, its success is undeniable. Designed by the Viennese studio PPAG Architects, Steirereck’s menu is as contemporary as its architecture, with seasonal dishes like apricot with soya, pineapple sage, and fermented honey in the shape of a rose. The building is even more striking, surrounded by the historic Stadtpark pavilion.

By Katie Schultz

By Audrey Lee

By Vaishnavi Nayel Talawadekar

Treehotel (Harads, Sweden)

The idea behind Treehotel was to do things a little differently than other luxurious hotels in the area. The architects of the seven suites—all of which have a different theme—wanted to offer guests the opportunity to connect with nature in an unconventional way. Enter the glass box, designed by architects Tham + Videgård Arkitekter. Dubbed The Mirrorcube, the unique structure almost disappears into its natural surroundings, and is accessible by a rope bridge that blends in with the forest.

Mirror Houses (Bolzano, Italy)

At the base of the South Tyrolean Dolomite mountains, among the apple trees, the Peter Pichler–designed Mirror Houses will set a new bar when it comes to vacation rental homes. Complete with a bedroom, living room, dining area, and fully functional kitchen (plus a private swimming pool in the summer months), the Mirror House is a must-visit.

LUMA Arles (Arles, France)

If there is one architect whose work has been lauded for decades, it’s Frank Gehry. One of his recent projects built in 2013, LUMA Arles, may not be clad in glass (in fact, it’s stainless steel), but it’s highly reflective—especially when the sun sets. Gehry’s inspiration? Arles’s plethora of Roman architecture, the city’s neighboring mountains, and Vincent van Gogh’s Starry Night painting, which the artist completed in Provence. Of course, Gehry put a massively contemporary twist on his awe-inspiring structure.

Invisible House (Joshua Tree, California)

Upon first glance, Invisible House does not look like a 22-story structure. But if you walk along its length, you’ll get it: It’s a skyscraper turned on its side. Complete with floor-to-ceiling sliding doors and windows that offer panoramic views of the surrounding desert, the property—available to rent on Airbnb —is set within 90 private acres. It also has a 100-foot-long indoor pool.

Summit One Vanderbilt (New York City)

Unveiled in 2021 next to New York City’s iconic Grand Central train station, the highly contrasting One Vanderbilt is a mirrored masterpiece that’s as immersive as it is artistic. Though there’s a lot to see, Summit’s centerpiece is the Snøhetta–designed 93rd-story observation deck whose walls, floors, and ceilings are outfitted in mirrors to distort visitors’ sense of place.

Casa Invisible (near Ljubljana, Slovenia)

Austrian studio Delugan Meissl designed a mirror-clad, low-cost housing unit in the supremely bucolic countryside of Slovenia. Its striking appearance is only one reason it’s so interesting—it’s also portable. It was built as a prototype to address the soaring housing prices in the country, but it’s also highly customizable, with the interior separated into three modules that can be configured however the residents choose.

Notariaat 2.0 (Horebeke, Belgium)

Architects Dries Vens and Maarten Vanbelle met while studying their degree in architecture in 2004. Two years later, the duo founded their eponymous firm. Together, they have completed more than 100 projects around the world. One of them is the reflective Notariaat 2.0. As its name implies, it’s the second iteration of a similar building the architects constructed several years earlier. However, they didn’t want to copy the original structure, so they took a totally different approach, making this one an abstract mirror box.

The Gherkin (London, England)

One of London’s most instantly recognizable landmarks, the 500,000-square-foot mirrored skyscraper is nicknamed The Gherkin because, as much as it looks like a torpedo, it also looks like a pickle. Designed by renowned architect Norman Foster, the pickle building completely transformed London’s financial district.

Château de Rentilly (Bussy-Saint-Martin, France)

About 30 minutes outside Paris, the shiny brainchild of artist Xavier Veilhan, architecture firm Bona-Lemercier, and stage designer Alexis Bertrand stands proud in the town of Bussy-Saint-Martin. Formerly a dilapidated château, the massive building is now a center for contemporary arts. Unlike many châteaux in France’s countryside, this one was crumbling so badly that it held no historical value, giving those who took over its redesign complete creative freedom to do just about anything they wanted.

- Reviews / Why join our community?

- For companies

- Frequently asked questions

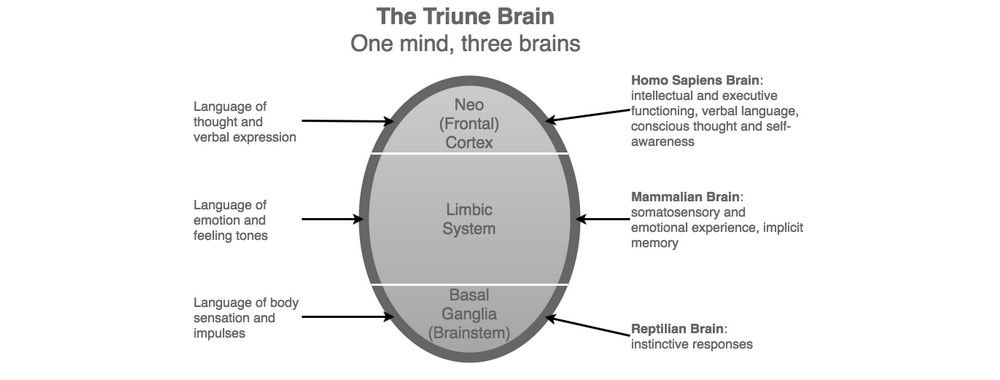

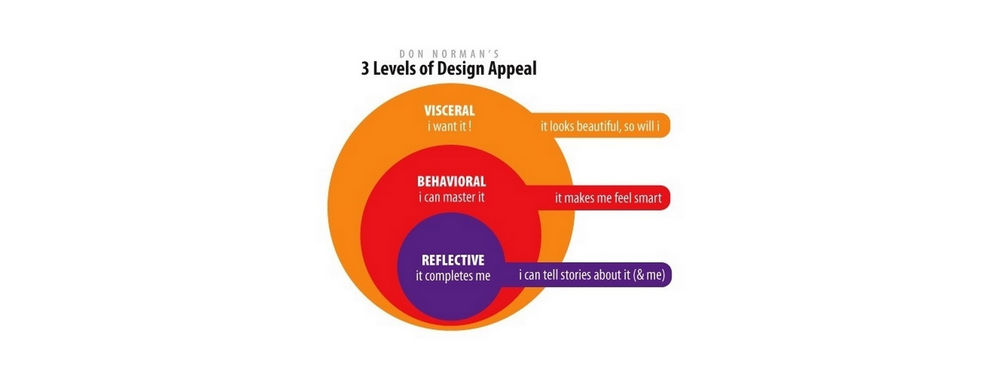

Norman's Three Levels of Design

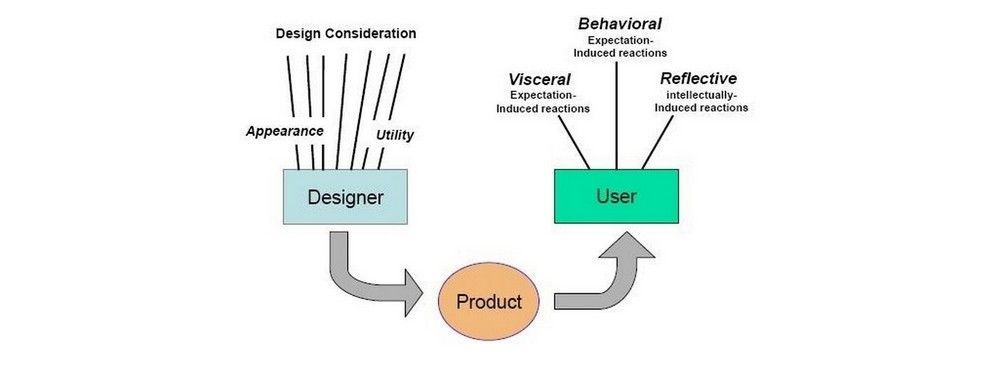

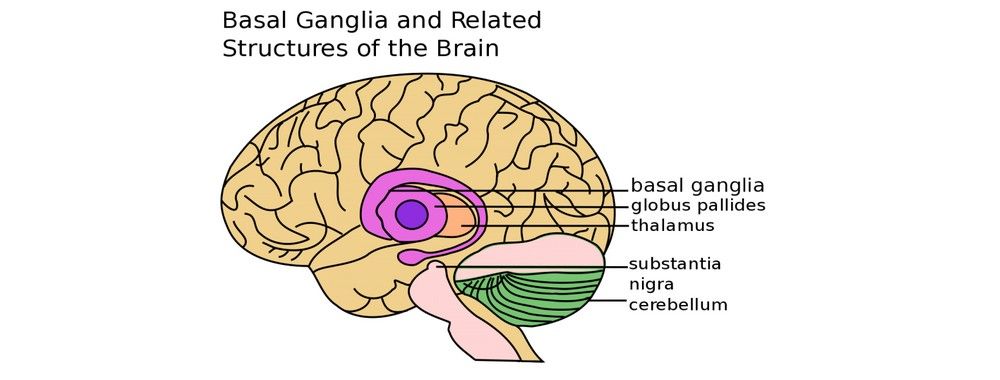

In the human mind there are numerous areas responsible for what we refer to as emotion ; collectively, these regions comprise the emotional system. Don Norman proposes the emotional system consists of three different, yet interconnected levels, each of which influences our experience of the world in a particular way. The three levels are visceral, behavioral, and reflective. The visceral level is responsible for the ingrained, automatic and almost animalistic qualities of human emotion, which are almost entirely out of our control. The behavioral level refers to the controlled aspects of human action, where we unconsciously analyze a situation so as to develop goal-directed strategies most likely to prove effective in the shortest time, or with the fewest actions, possible. The reflective level is, as Don Norman states, "...the home of reflection, of conscious thought, of learning of new concepts and generalisations about the world". These three levels, while classified as separate dimensions of the emotional system, are linked and influence one another to create our overall emotional experience of the world.

In Emotional Design : Why we love (or hate) everyday things , Don Norman (a prominent academic in the field of cognitive science , design, and usability engineering) distinguishes between three aspects, or levels, of the emotional system (i.e. the sum of the parts responsible for emotion in the human mind), which are as follows: the visceral, behavioral and reflective levels. Each of these levels or dimensions, while heavily connected and interwoven in the emotional system, influences design in its own specific way. The three corresponding levels of design are outlined below:

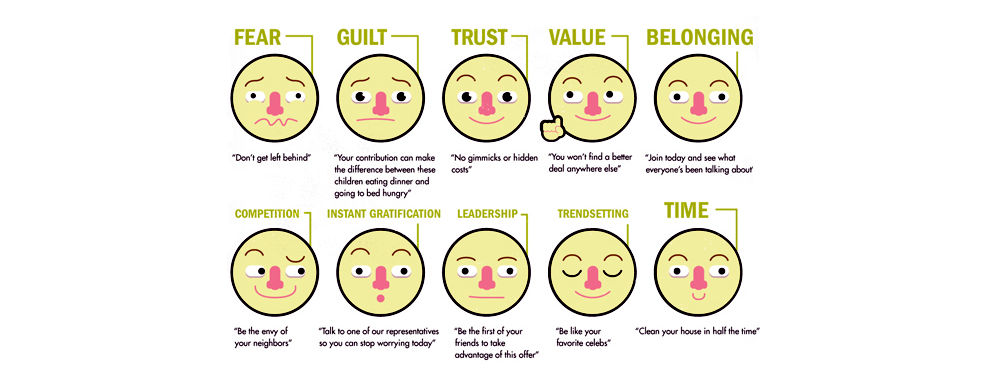

Visceral Design – "Concerns itself with appearances". This level of design refers to the perceptible qualities of the object and how they make the user/observer feel. For example, a grandfather clock offers no more features or time-telling functions than a small, featureless mantelpiece clock, but the visceral (deep-rooted, unconscious, subjective, and automatic feelings) qualities distinguish the two in the eyes of the owner. Much of the time spent on product development is now dedicated to visceral design, as most products within a particular group (e.g., torches/flashlights, kettles, toasters, and lamps) tend to offer the same or a similar set of functions, so the superficial aspects help distinguish a product from its competitors. What we are essentially referring to here is 'branding'—namely, the act of distinguishing one product from another, not by the tangible benefits it offers the user but by tapping into the users’ attitudes , beliefs , feelings , and how they want to feel, so as to elicit such emotional responses . This might be achieved by using pictures of children, animals or cartoon characters to give something the appearance of youthfulness, or by using colors (e.g., red for 'sexy' and black for 'powerful'), shapes (e.g., hard-lined shapes) or even styles (e.g., Art Deco) that are evocative of certain eras. Visceral design aims to get inside the user's/customer's/observer's head and tug at his/her emotions either to improve the user experience (e.g., improving the general visual appeal) or to serve some business interest (e.g., emotionally blackmailing the customer/user/observer to make a purchase, to suit the company's/business's/product owner's objectives).

Behavioral Design – "...has to do with the pleasure and effectiveness of use." Behavioural design is probably more often referred to as usability , but the two terms essentially refer to the practical and functional aspects of a product or anything usable we are capable of using in our environment. Behavioral design (we shall use this term in place of usability from now on) is interested in, for example, how users carry out their activities, how quickly and accurately they can achieve their aims and objectives, how many errors the users make when carrying out certain tasks, and how well the product accommodates both skilled and inexperienced users. Behavioral design is perhaps the easiest to test, as performance levels can be measured once the physical (e.g., handles, buttons, grips, levers, switches, and keys) or usable parts of an object are changed or manipulated in some way. For instance, buttons responsible for two separate operations might be positioned at varying distances from one another so as to test how long it takes the user to carry out the two tasks consecutively. Alternatively, error rates might be measured using the same manipulation(s). Examples of experiences at the behavioral level include the pleasure derived from being able to find a contact and make a call immediately on a mobile phone, the ease of typing on a computer keyboard, the difficulty of typing on a small touchscreen device, such as an iPod Touch, and the enjoyment we feel when using a well-designed computer game controller (such as, in my humble opinion, the N64 control pad). The behavioral level essentially refers to the emotions we feel as a result of either accomplishing or failing to complete our goals. When products/objects enable us to complete our goals with the minimum of difficulty and with little call for conscious effort, the emotions are likely to be positive ones. In contrast, when products restrict us, force us to translate or adjust our goals according to their limitations, or simply make us pay close attention when we are using them, we are more inclined to experience some negative emotion.

Reflective Design – "...considers the rationalization and intellectualization of a product. Can I tell a story about it? Does it appeal to my self-image, to my pride?" This is the highest level of emotional design; representing the conscious thought layer, where we consciously approach a design; weighing up its pros and cons, judging it according to our more nuanced and rational side, and extracting information to determine what it means to us as an individual. Reflective thinking allows us to rationalise environmental information to influence the behavioural level. Take for example smartwatches. On that note, researchers Jaewon Choi and Songcheol Kim at the University of Korea examined users’ intentions to adopt smartwatches under two major factors, namely a user’s perception of the device as a technological innovation and as a luxury fashion product . Users’ view of the smartwatch as a technological innovation relates to their perception of the device’s usefulness and ease of use (the behavioral level). On the other hand, the users’ view of the smartwatch as a luxury fashion product relates to their perception of how much they would enjoy the smartwatch and the levels of self-expressiveness the device will afford to them, i.e. the ability to express themselves and to enhance their image. Both enjoyment and self-expressiveness are influenced by the visceral level ("Does the watch look beautiful?") but also very much by the reflective level ("What will my friends think when they see me wearing this watch? "). The reflective level mediates the effects of the behavioral level – users may well put up with difficulties and shortcomings in the usability of the smartwatch because they believe they will gain other, non-functional benefits from it. Apple’s first version of their smartwatch was riddled with functional problems and usability issues , but that didn’t stop the company from generating the second largest worldwide revenue in the watch industry within the first year of selling it!

The Take Away

Here, we have introduced Don Norman's three levels of design: The visceral, behavioral, and reflective level of design. The visceral level of design refers to the first impression of a design, both in terms of how the user perceives the product and how it makes the user feel. The behavioral level refers to the experience of the product in use. We often think of this level when we think of user experience. The reflective level refers to the user's reflections about the product, both before, during, and after use. The three levels all combine to form the entire product experience.

The perfect follow-up video: The three ways good design makes us happy from Don Norman

References & Where to Learn More

Choi, J., & Kim, S. (2016). “Is the smartwatch an IT product or a fashion product? A study on factors affecting the intention to use smartwatches”. Computers in Human Behavior , 63, 777-786.

Design for the 21st Century with Don Norman

Get Weekly Design Insights

Topics in this article, what you should read next, self-actualization: maslow's hierarchy of needs.

- 1.1k shares

- 4 years ago

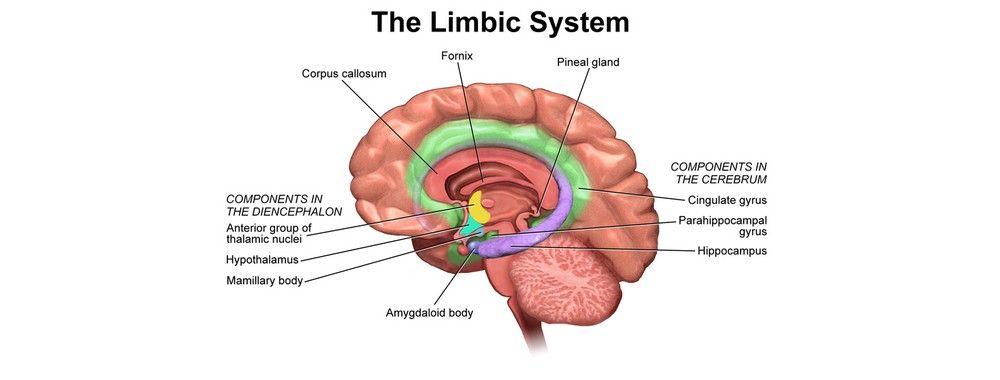

Our Three Brains - The Reptilian Brain

- 3 years ago

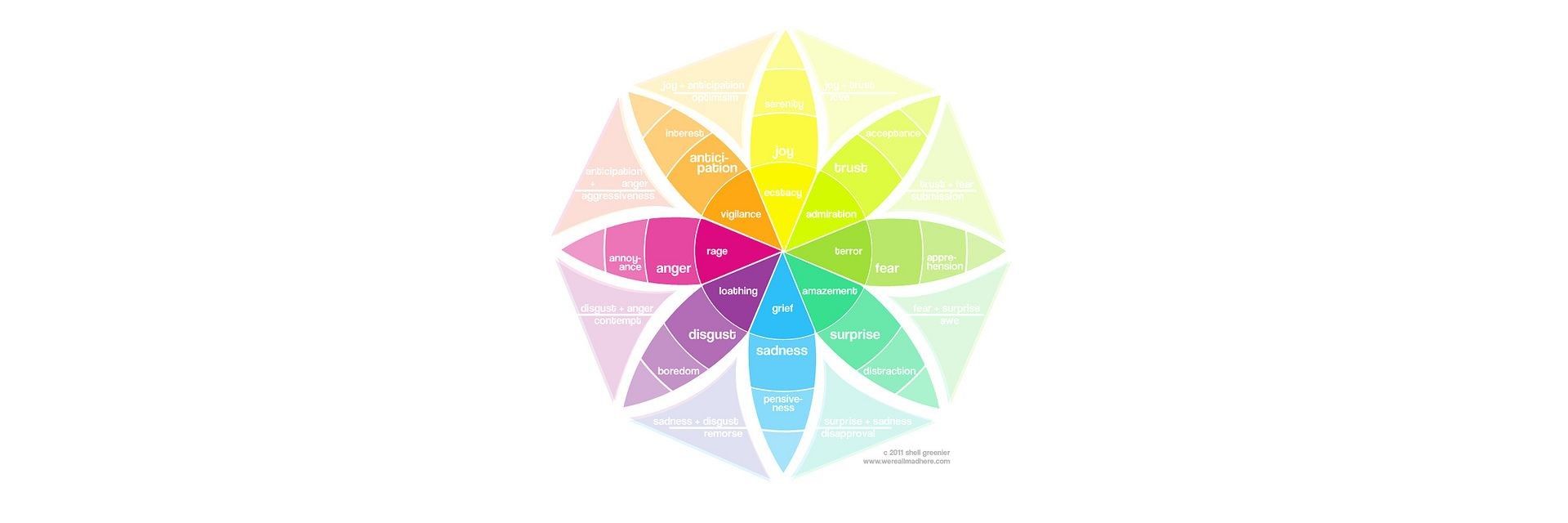

Putting Some Emotion into Your Design – Plutchik’s Wheel of Emotions

Esteem: Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs

The Concept of the "Triune Brain"

Our Three Brains - The Emotional Brain

How to Prevent Negative Emotions in the User Experience of Your Product

The Reflective Level of Emotional Design

Creating Emotional Connections

Our Three Brains - The Rational Brain

Open Access—Link to us!

We believe in Open Access and the democratization of knowledge . Unfortunately, world-class educational materials such as this page are normally hidden behind paywalls or in expensive textbooks.

If you want this to change , cite this article , link to us, or join us to help us democratize design knowledge !

Privacy Settings

Our digital services use necessary tracking technologies, including third-party cookies, for security, functionality, and to uphold user rights. Optional cookies offer enhanced features, and analytics.

Experience the full potential of our site that remembers your preferences and supports secure sign-in.

Governs the storage of data necessary for maintaining website security, user authentication, and fraud prevention mechanisms.

Enhanced Functionality

Saves your settings and preferences, like your location, for a more personalized experience.

Referral Program

We use cookies to enable our referral program, giving you and your friends discounts.

Error Reporting

We share user ID with Bugsnag and NewRelic to help us track errors and fix issues.

Optimize your experience by allowing us to monitor site usage. You’ll enjoy a smoother, more personalized journey without compromising your privacy.

Analytics Storage

Collects anonymous data on how you navigate and interact, helping us make informed improvements.

Differentiates real visitors from automated bots, ensuring accurate usage data and improving your website experience.

Lets us tailor your digital ads to match your interests, making them more relevant and useful to you.

Advertising Storage

Stores information for better-targeted advertising, enhancing your online ad experience.

Personalization Storage

Permits storing data to personalize content and ads across Google services based on user behavior, enhancing overall user experience.

Advertising Personalization

Allows for content and ad personalization across Google services based on user behavior. This consent enhances user experiences.

Enables personalizing ads based on user data and interactions, allowing for more relevant advertising experiences across Google services.

Receive more relevant advertisements by sharing your interests and behavior with our trusted advertising partners.

Enables better ad targeting and measurement on Meta platforms, making ads you see more relevant.

Allows for improved ad effectiveness and measurement through Meta’s Conversions API, ensuring privacy-compliant data sharing.

LinkedIn Insights

Tracks conversions, retargeting, and web analytics for LinkedIn ad campaigns, enhancing ad relevance and performance.

LinkedIn CAPI

Enhances LinkedIn advertising through server-side event tracking, offering more accurate measurement and personalization.

Google Ads Tag

Tracks ad performance and user engagement, helping deliver ads that are most useful to you.

Share the knowledge!

Share this content on:

or copy link

Cite according to academic standards

Simply copy and paste the text below into your bibliographic reference list, onto your blog, or anywhere else. You can also just hyperlink to this article.

New to UX Design? We’re giving you a free ebook!

Download our free ebook The Basics of User Experience Design to learn about core concepts of UX design.

In 9 chapters, we’ll cover: conducting user interviews, design thinking, interaction design, mobile UX design, usability, UX research, and many more!

New to UX Design? We’re Giving You a Free ebook!

Introduction

- Part I. Instructional Design Practice

- Understanding

- 1. Becoming a Learning Designer

- 2. Designing for Diverse Learners

- 3. Conducting Research for Design

- 4. Determining Environmental and Contextual Needs

- 5. Conducting a Learner Analysis

- 6. Problem Framing

- 7. Using Task Analysis to Inform Instructional Design

- 8. Documenting Instructional Design Decisions

- 9. Generating Ideas

- 10. Instructional Strategies

- 11. Instructional Design Prototyping Strategies

- 12. Design Critique

- 13. The Role of Design Judgment and Reflection in Instructional Design

- 14. Instructional Design Evaluation

- 15. Continuous Improvement of Instructional Materials

- Part II. Instructional Design Knowledge

- Sources of Design Knowledge

- 16. Learning Theories

- 17. The Role of Theory in Instructional Design

- 18. Making Good Design Judgments via the Instructional Theory Framework

- 20. The Nature and Use of Precedent in Designing

- 21. Standards and Competencies for Instructional Design and Technology Professionals

- Instructional Design Processes

- 22. Design Thinking

- 23. Robert Gagné and the Systematic Design of Instruction

- 24. Designing Instruction for Complex Learning

- 25. Curriculum Design Processes

- 26. Agile Design Processes and Project Management

- Designing Instructional Activities

- 27. Designing Technology-Enhanced Learning Experiences

- 28. Designing Instructional Text

- 29. Audio and Video Production for Instructional Design Professionals

- 30. Using Visual and Graphic Elements While Designing Instructional Activities

- 31. Simulations and Games

- 32. Designing Informal Learning Environments

- 33. The Design of Holistic Learning Environments

- 34. Measuring Student Learning

- Design Relationships

- 35. Working With Stakeholders and Clients

- 36. Leading Project Teams

- 37. Implementation and Instructional Design

- Author Biographies

- Translations

The Role of Design Judgment and Reflection in Instructional Design

Choose a sign-in option.

Tools and Settings

Questions and Tasks

Citation and Embed Code

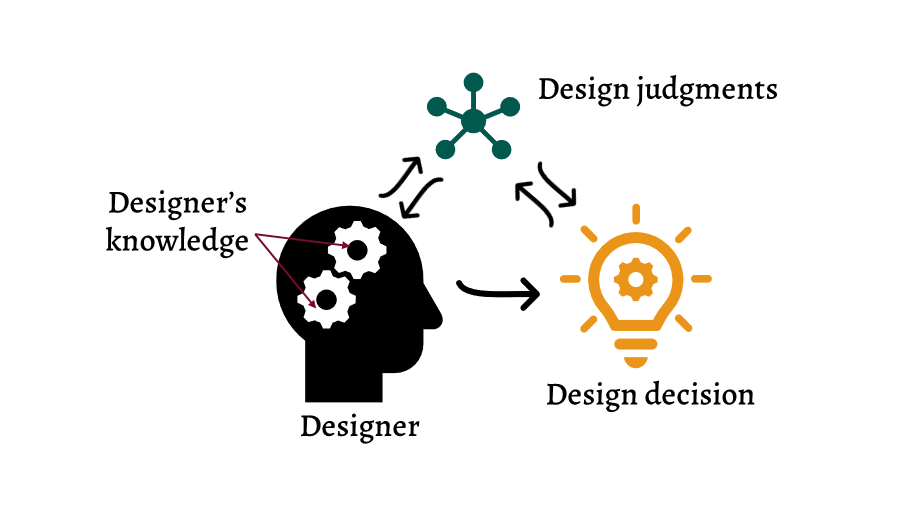

As a student of instructional design (ID), or as a future ID practitioner, you will have to make many decisions that allow you to move forward in your design work. Such decisions will be informed in part by the particular situation you are dealing with, influenced by precedent design experience ( see more about design precedent here ), and inflected with your values and ideals. Making decisions is a fundamental human capacity. When designing, designers make decisions specific to design. The capacity to make solid design decisions is what distinguishes excellent designers from mediocre designers. So how can designers make solid decisions? The answer is through evoking good design judgments and constantly reflecting on their design work.

What is Design Judgment?

When designers face complex situations—a constraint, a problem with a client or another design stakeholder, a block in the design process—they need to make design judgments to reduce the complexity of the situation or solve the issue that has been encountered. Depending on the situation, a specific design judgment is invoked to make design decisions. In the area of general design theory, Nelson and Stolterman (2012) have identified design judgment as “essential to design. It does not replicate decision making but it is necessary” (p. 139). In this definition, the authors distinguish judgment from decision-making. Design judgments for them are the means to achieve “wise action” (p. 139), or—in other words—good design decisions. In this way, designers can think about design decisions as the “what and how,” of design, whereas design judgments have to do with the “why” a design decision has been made (see Figure 1).

How Are Design Judgments Related to Design Decisions?

The second is instrumental judgment —“interaction with their [designers’] materials and the tools” (p. 152). Instrumental is used here to mean ‘instrument’ and not to mean ‘important.’ Designers invoke instrumental judgments to decide on which design tools to use or not, and how to use them for their design projects (e.g., drawing icons using a digital tool or using a paper and pencil). This judgment is one of the most invoked judgments as it is concerned with design tools—all kinds of means that designers use to design, regardless of their form—and because design tools encompass almost every design activity. Design tools could be abstract/theoretical or tangible, analog, or digital. If you are curious, you can read more about design tools in instructional design practice in Lachheb and Boling (2018).

The third is framing judgment —“defining and embracing the space of potential design outcomes … [it] forms the limits that delineate the conceptual container” (Nelson & Stolterman, 2012, p. 148). In evoking this design judgment, designers discuss the goal of their design project (e.g., designing an academic course, a workshop, a performance-support handout, etc.) in order to frame what the design project is about. Framing judgment is also invoked throughout the progress of a project that involves deciding what is important to focus on next.

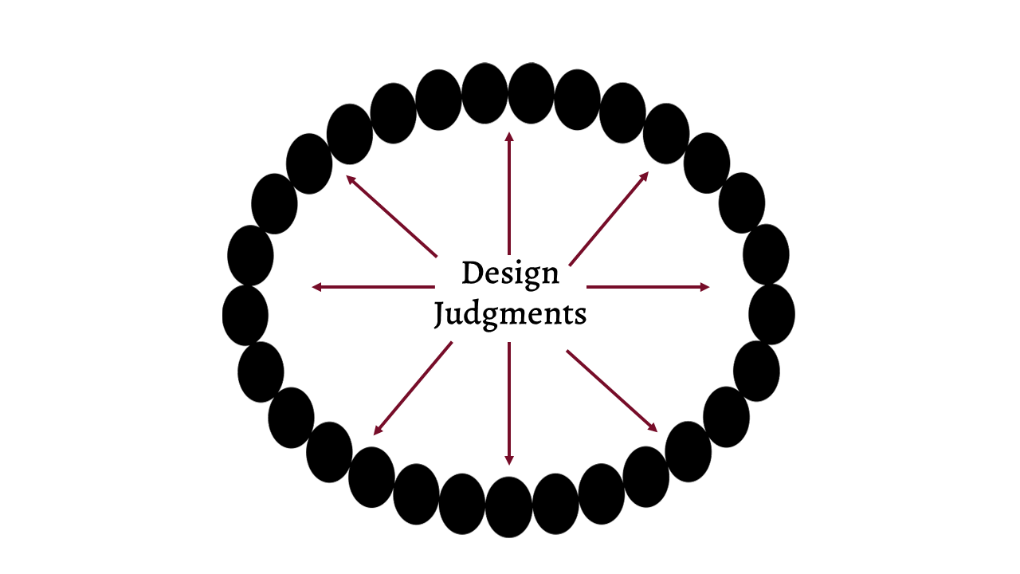

Guidance to Develop and Invoke Design Judgments

You might be asking now, “What design judgments should I make? Which ones are the best design judgments? How will I know? How does a designer learn to make good design judgments?” These are very legitimate and important questions. Frankly, these questions are what actually spark many research studies on design practice; answering them is not as straightforward as one sometimes wishes.

First, it is important to think about these design judgments as not isolated units, but rather like pearls that are connected to each other with strings. If you take one pearl and you hold it up, then the other ones just hang as a cluster underneath because they are connected to each other (E. Stolterman, personal communication, November 18, 2013). Designers often invoke a number of design judgments together—always interconnected and often overlapping (see Figure 2). That being said, as you are practicing design, you will be making these design judgments at all times, most of the time unconsciously. Now that you read about them, you can think about them in a conscious manner and watch for when a design judgment you invoke does not lead to the desired result.

How Are Design Judgments Interconnected?

As you can see in this example, the student expressed how hard it was for them to make design decisions. The student reflected on what they believe to be the appropriate design moves, how to begin, and what the design should be focused on. Toward the end of the reflection, the student expressed a set of values and ideals—core design judgments.

Design Judgments and Reflection: Recommendations for Instructional Design Students

The reflection journal.

Some designers keep a journal. Some designers turn parts of their journal into a blog or a website where they reflect on their design work publicly. Commit to a journal in the format you prefer–a simple notebook, a Google document, a blog, a video, a podcast. Start your first entry about the last design project you completed in class and address the following prompt (adapted from Tracey et al, 2014):

Describe a time when you felt totally uncertain while working on this design project. Try to remember how you felt and what was the greatest challenge(s) you faced because of the uncertainty you felt. What actions did you take to overcome such uncertainty? How did it go? Why did you take certain actions and not other actions? What did you believe to be happening vs. what actually happened? Knowing that you will feel uncertain in future design projects, how do you feel about becoming a designer?

Start writing the reflection post using descriptive language. You should not worry about grammar and typos at this stage. Let the words and thoughts flow and make their way from your head to the journal. Pay attention to how you felt and what thoughts you had at the moment. Think about if someone reads this reflection, will they understand what was going on in the design project? Will they get to feel how you felt? Don’t limit yourself to formal writing. Write as you think and speak. Once you complete this first entry, share it with your ID faculty or another designer if you feel comfortable.

The following are some ways to document design reflections:

- Pick what you want to focus on for each reflection—a challenge with a designer, a moment of design failure, a harsh critique from a client, or an SME; you pick.

- Describe your design actions by addressing the Five Ws (What, When, Where, Why, Who).

- Elaborate on the “Why” part so you can reveal the design judgments you made that led to these design actions.

- Speculate on the “Why” when speaking about other’s actions, unless you are certain.

- Conclude with what you have learned from this design project—what you will not forget to do next time? To what extent this design project will be similar to future projects you anticipate?

Exploring Your Core Design Judgments

People are surrounded by designs they use every day, and some they cannot live without. Commit to a week of noticing and collecting—through photographs—designs that you appreciate and designs that you do not like at all. These could be the items you use every day, such as your phone, the showerhead in your bathroom, a specific app, or a favorite frying pan in your kitchen, or anything else. Challenge yourself to notice as many designs as possible. Such design could include instruction or performance support materials around you (e.g., a flyer that teaches people how to wash their hands or the instructional book that comes with IKEA furniture). Take about an hour or more to write down notes about each design—why you appreciate it and why you do not. Keep asking yourself “why do I like/dislike this?” and record your answers. Repeat this activity until you cannot think of any more answers to. For example, the authors appreciate public libraries. We like them because we find the books we like to borrow and not buy, they are accessible to us, they are free, they are diverse, and they provide quiet places for us to concentrate. We can say more why we like public libraries, but essentially we like public libraries because we believe in the noble cause of public goods, and public libraries represent such a cause .

Now examine your answers to the “why” questions and try to think about how such answers represent values you hold. These could be transparency, ease of use, elegance, democratic, accessible, inclusive/exclusive, soft, strong, and so on. These values constitute your core judgments and influence all kinds of design judgments you make. You may not be able to access all of them completely, but you are aiming to heighten your awareness of what your design values really are. Once you have spent some time on this exercise, consider revisiting it in the future to see any change you might notice in terms of the values you have—write a reflection post on such change. You can focus the noticing experience on specific types of designs (e.g., phone apps), or you can mix designs together that you see belong to each other (e.g., instructional posters and cooking books). Essentially, noticing designs and why you appreciate them will become a somewhat automatic habit for you. By these means you can question and refine your judgement across a whole career.

Additional Information

Ways to document design judgments and decisions:

- Document your design through documents and project management tools—you will have an audit trail at the end of the project that helps you or anyone else to trace back what design decisions you have made.

- Use the margins of such documents to add comments/thoughts and explanations on design decisions you have made.

- Archive written conversations (emails, chats, etc.…) between you and other design stakeholders that include design decisions (and most likely your “defense” or such decisions).

- Leverage your design reflections, notes, and design documents to write a design a case which you can publish in the International Journal of Designs for Learning (IJDL) .

You may have heard the common wisdom that to become a better professional, you should engage in at least 10,000 hours of practice in your profession. While there is truth in the advice that many, many hours of practice are required to develop expertise, the authors are also confident in an additional claim that there is more to expertise than just putting in a certain number of hours. Without deliberately reflecting on your design actions and the design judgments that lead to those actions, not even 10,000 hours of instructional design practice will be enough to make you an expert designer. Explicitly reflecting on your design judgments, in addition to reflecting on your practice, is what will help you become a more engaged and expert designer. Make reflection on your design judgments an intentional aspect of your efforts to develop your growing competence as a member of the instructional design profession.

References and Suggested Readings

Boling, E., Alangari, H., Hajdu, I. M., Guo, M., Gyabak, K., Khlaif, Z., Kizilboga, R., Tomita, K., Alsaif, M., Lachheb, A., Bae, H., Ergulec, F., Zhu, M., Basdogan, M., Buggs, C., Sari., R., & Techawitthayachinda, R. I. (2017). Core judgments of instructional designers in practice. Performance Improvement Quarterly , 30 (3), 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1002/piq.21250

Boling, E., & Gray, C. M. (2015). Designerly tools, sketching, and instructional designers and the guarantors of design. In B. Hokanson, G. Clinton, & M. Tracey (Eds.), The design of learning experience: Creating the future of educational technology (pp. 109–126). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16504-2

Cross, N. (2001). Designerly ways of knowing: Design discipline versus design science. Design Issues , 17 (3), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1162/074793601750357196

Dabbagh, N. & Blijd, C. W. (2010). Students’ perceptions of their learning experiences in an authentic instructional design context. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning , 4 (1), 6–29. https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1092

Demiral-Uzan, M. (2017). The Development of Design Judgment in Instructional Design Students During a Semester in Their Graduate Program (Doctoral dissertation, Indiana University).

Demiral‐Uzan, M. (2015). Instructional design students’ design judgment in action. Performance Improvement Quarterly , 28 (3), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/piq.21195

Ericsson, K. A. (2006). Protocol analysis and expert thought: Concurrent verbalizations of thinking during experts’ performance on representative tasks. The Cambridge handbook of expertise and expert performance, 223–241.

Gray, C. M., Dagli, C., Demiral‐Uzan, M., Ergulec, F., Tan, V., Altuwaijri, A. A., Gyabak, K., Hilligoss, M., Kizilboga, R., Tomita, K. & Boling, E. (2015). Judgment and instructional design: How ID practitioners work in practice. Performance Improvement Quarterly , 28 (3), 25–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/piq.21198

Kaminski, K., Johnson, P., Otis, S., Perry, D., Schmidt, T., Whetsel, M., & Williams, H. (2018). Personal Tales of Instructional Design from the Facilitator’s Perspective. In B. Hokanson, G. Clinton & K. Kaminski (Eds.), Educational Technology and Narrative (pp. 87–101). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69914-1

Korkmaz, N., & Boling, E. (2014). Development of design judgment in instructional design: Perspectives from instructors, students, and instructional designers. Design in Educational Technology (pp. 161–184). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-00927-8_10

Lachheb, A., & Boling, E. (2018). Design tools in practice: instructional designers report which tools they use and why. Journal of Computing in Higher Education , 30 (1), 34–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-017-9165-x

Nelson, H. G., & Stolterman, E. (2012). The design way: Intentional change in an unpredictable world (2nd ed.). The MIT Press.

Schön, D. (1983). The Reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Temple-Smith.

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. John Wiley & Sons.

Smith, K. M., & Boling, E. (2009). What do we make of design? Design as a concept in educational technology. Educational Technology , 49 (4), 3–17.

Stolterman, E., McAtee, J., Royer, D., & Thandapani, S. (2009). Designerly tools. http://shura.shu.ac.uk/id/eprint/491

Tracey, M. W., Hutchinson, A., & Grzebyk, T. Q. (2014). Instructional designers as reflective practitioners: Developing professional identity through reflection. Educational Technology Research and Development , 62 (3), 315–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-014-9334-9

Yanchar, S. C., South, J. B., Williams, D. D., Allen, S., & Wilson, B. G. (2010). Struggling with theory? A qualitative investigation of conceptual tool use in instructional design. Educational Technology Research and Development , 58 (1), 39–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-009-9129-6

This content is provided to you freely by BYU Open Learning Network.

Access it online or download it at https://open.byu.edu/id/design_judgment .

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Student Guide to Reflection

introduction.

Reflection is a means of extracting more learning from our experiences, leading to deep understanding of knowledge, connections to other contexts, and an improved sense of self-efficacy.

This module provides students with essential knowledge of written reflection, including the topics of fundamental reflection and strategies in writing reflection.

Modes of Learning

In this module, students will use the following modes of learning:

- A short assessment

- A writing activity

This module will take approximately 60 minutes to complete.

Intended Learning Outcomes

By the end of this module, participants will be able to…

- Identify the fundamental components of written reflections

- Write a simple, written reflection using the ‘What? So what? Now what?’ framework

Key Terms & Concepts

Topic 1: basics of reflection.

It is important to understand th e essential principles behind written reflection. The following video will walk you through the fundamental process of reflection , examples of what reflection looks like, and why we should reflect as lifelong learners.

Watch Basics of Reflection in full screen.

Complete the short quiz below by matching the statements on the right with the corresponding section of the ‘What? So What? Now What?’ model on the left.

Topic 2: Writing a Reflection

Now that you’ve gained a better understanding of what reflection is and why we do it, it’s your turn to practice . The following video will provide you will an example of a student’s written reflection to prepare you for writing your own.

Watch Writing a Reflection in full screen.

Reflection Example

Below is a text copy of the reflection example provided in the video:

In the fourth year of my undergraduate program, I participated in a laboratory activity in which we were to compare the theoretical levels of xenon in the McMaster Nuclear Reactor (MNR) with the actual data logs recorded by the reactor operators. This lab report was done individually. One aspect that made me nervous was that I was not comparing theoretical xenon level directly to recorded x enon level, but rather I had to calculate the measured xenon levels based on the activities recorded by the operators. I was nervous that I would not be able to interpret the operators’ notes correctly, which would then make it very hard to compare to a theoretical model.

Initially after converting the operator records, I found that the data was not fitting the theoretical levels whatsoever. I was really discouraged by this, so I referred to the course readings to see where I might have missed vital information. After looking back, I had realized that I missed two important, yet subtle, steps in converting the data. I had not accounted for the fact that the polarity of the two measurements were reversed, and so I needed to flip one of the graphs. I also missed an offset, meaning I had to shift one of the graphs down. After making these corrections, the data was a perfect fit! Seeing the two graphs line up was very fulfilling, and it was the result of applying knowledge that I had learned, while also identifying knowledge that I had misunderstood or missed entirely the first time.

This lab was important to nuclear engineering because xenon levels are what dictates whether a reactor can be powered on or not. By going through this lab, I am now aware how, as a reactor operator, I would be able to judge the status of reactor based on these readings. Having recognized the calculations that I did not do properly the first time, I feel much more confident about never forgetting those steps again.

Reflection Writing Activity

Think of an important educational experience that you’ve had and, on a separate piece of paper or in a Word document, write a reflection about it. Be sure to address each point of the ‘What? So what? Now what?’ model.

Use the questions below to guide your thinking and writing about each section of the model.

Here is an example of a student working through the reflective process.

References

Ambrose, S. A. (2013). Undergraduate engineering curriculum: The ultimate design challenge. The Bridge, 43 (2), 16-23

Ash, S. L., & Clayton, P. H. (2009). Generating, deepening, and documenting learning: The power of critical reflection in applied learning. Journal of Applied Learning in Higher Education, 1 (1), 25-48.

Borton, T. (1970). Reach, touch, and teach (pp. 75-91). New York. McGraw-Hill.

CPREE. (n.d.) What is Reflection? Consortium to Promote Reflection in Engineering Education (CPREE). http://cpree.uw.edu/what-is-reflection/

Dewey, J. (1966). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education . The Free Press.

Driscoll, J. (1994). Reflective practice for practice. Senior Nurse, 14 (1), 47-50.

Rolfe, G., Freshwater, D., & Jasper, M. (2001). Critical Reflection for Nursing and the Helping Professions: A User’s Guide . Palgrave.

Ryan, M. (2013). The pedagogical balancing act: Teaching reflection in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 18 (2), 144-155.

Turns, J. A., Sattler, B., Yasuhara, K., Borgford-Parnell, J. L., & Atman, C. J. (2014). Integrating reflection into engineering education. [Paper Presentation]. 121st ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Indianapolis. https://depts.washington.edu/cpreeuw/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Integrating-Reflection-ASEE-2014.pdf

Engineering Reflection Guidebook Copyright © 2022 by Kyle Ansilio, Shelir Ebrahimi, and Alanna Carter is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Advertisement

Reflection in design education

- Open access

- Published: 25 June 2019

- Volume 30 , pages 885–897, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Louis Lousberg 1 ,

- Remon Rooij 1 ,

- Sylvia Jansen 2 ,

- Elise van Dooren 1 ,

- John Heintz 1 &

- Engbert van der Zaag 1

7898 Accesses

10 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

In this article we evaluate the manner in which we at the Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment at the Delft University of Technology encourage the development of the capacity of reflection among our undergraduate students. First we explore the concept of reflection in relation to respectively experiential/reflective learning, reflection in/on action, reflection in higher education and reflection in design education. Next we describe our research object, our Bachelor course in Academic Design Reflection. Two research questions are at hand: (1) does the level of reflection increase during our course and (2) Can the operationalisation in our questionnaire of the definitions of reflection derived from theory statistically be confirmed? We measured and processed statistically the level of reflection of 100 students in 3 of their papers on their design. Results show there is a significant slight increase of this level among the three papers. Results also show that our model of classification is not statistically confirmed in the data. We conclude with a discussion on the implications for further research and for design education.

Similar content being viewed by others

The ReflecTable: Bridging the Gap between Theory and Practice in Design Education

Reflection and professional identity development in design education.

Monica W. Tracey & Alisa Hutchinson

Design Requirements of Tools Supporting Reflection on Design Impact

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

‘The first challenge for engineering education is to anticipate the capabilities our graduates will need in their future jobs’ (Kamp 2016a , b : p. 12). Professionals with the combined skill of analysis and synthesis are becoming more and more pivotal in a complex and uncertain world, which asks for answers and solutions for today’s and tomorrow’s questions of sustainable and equitable (urban) development. To prepare engineers for their future jobs we need to emphasize not only the academic skills of analysis and research, but also, and more and more, the academic skills of synthesis (Kamp 2016a , b ). In designing, reflection can be added to that as a third skill (cf. van Doorn 2004 : p. 32; Boekholt 1984 ) Our proposition is that rigorous and thorough attention for reflection in design education plays a key role in developing these skills.

Contrary to reflection-in-learning in health professions (e.g. Mann et al. 2009 ) or higher education in general (e.g. Mittendorff 2014 ), little is known of reflection in design education, especially on the effectiveness of learning to reflect. Even though the importance of the development of a reflective practitioner is supported in the literature on (construction) projects (e.g. Ojiako et al. 2008 ; Sage et al. 2010 ). This article contributes to filling this knowledge gap.

Our research object is our third (and final) year Bachelor course in Academic Design Reflection at our Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment at the Delft University of Technology. The objective of the research is to check if our course contributes to the development of the capacity of reflection among our undergraduate students. Two research questions are at hand: (1) does the level of reflection increase during our course and (2) Can the operationalisation in our questionnaire statistically confirm the definition of reflection derived from theory?

In the article we first explore the concept of reflection in learning (Kolb 1984 ; Moon 2004 ), in practice (Schön 1982 ; Moon 2004 ) and in higher education (Brockbank 1989 ; Fry et al. 2003 ; Cowan 2006 ). After presenting the case we next, based on the four levels of reflection developed by Moon ( 2004 )—descriptive writing, descriptive reflection, dialogic reflection, critical reflection—evaluate the development of the level of reflection on design in papers of over a hundred of final year B.Sc. students in Architecture, Urbanism and Building Sciences (AUBS). Over a 10 week period, these students (about 150 two times per academic year) develop both an integral design for a museum and a series of four academic papers underpinning and evaluating (1) the design situation, (2) the design theme, (3) the design process and (4) the relation between design and academic research. From this evaluation we draw conclusions on the effectiveness of the reflection and derive implications for design education.

Exploring reflection

Since the early eighties of the last century reflection has become an issue in literature on professional education (e.g. Schön 1982 ). Depending on their underlying view reflection can be defined in different ways. Reflection can be seen as Dewey’s ( 1933 ) ‘thinking to encompass feelings and emotions in practice settings’ (in: Boud and Garrick 1999 : p. 4), as ‘thinking about doing something while doing it’ (Schön 1982 : p. 54), as ‘reflective learning’ (Moon 2004 : p. 80) or as ‘a means to engage in making sense of experience in situations that are rich and complex and which do not lend themselves to being simplified by the use of concepts and frameworks that can be taught’ (Boud and Garrick 1999 : p. 4). Trying to be applicable to different context’s these definitions are necessarily general. Within the context of reflection in design education in our course we define it for our students, close to the definition of Reflection (in Action) of Schön but broader, as ‘thinking about your own work’.

Experiential learning or reflective learning

Departing from this ‘thinking about your own work’, for our students in AUBS it is thinking about your own design. Design is an object here (to think about), similar to experience as an object (to think about). This brings us to the theory of experiential learning as coined by Kolb ( 1984 ). Kolb defines experiential learning as ‘the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience’ (Kolb 1984 : p. 38).

Moon ( 2004 ) distinguishes experiential learning from reflective learning. Reflection is ‘a form of mental processing—like a form of thinking- that we may use to fulfil a purpose or to achieve some anticipated outcome or we may simply ‘be reflective’ and then an outcome can be unexpected.‘(ibid: 82) and in an academic context ‘reflection/reflective learning or reflective writing (-), is also likely to involve a conscious and stated purpose for the reflection, with an outcome specified in terms of learning, action or clarification. It may be preceded by a description of the purpose and/or subject matter of the reflection. The process and outcome of reflective work are most likely to be in a represented (e.g., written) form, to be seen by others and to be assessed (-).‘(ibid: 83).

In literature several definitions of experiential learning are suggested for educational contexts; unanimity from this range of views is not possible. The root cause of this seems to be lying in the variety of views of experience (ibid: 109). Here, in our cause, the experience was the experience of design(ing). Hence we define experiential learning as ‘a process in which an experience is reflected upon and then translated into concepts (-)’ (ibid: 109), supported by the proposition that experiential learning in academic contexts seems to occur in situations wherein ‘the material of learning is ill-structured and challenging to a learner’ (ibid: 129), designing is exactly such a situation (Simon 1969 ).

The difference between experiential learning and reflective learning seems to be lying in an immediate reflection in experiential learning and a reflection afterwards in reflective learning in an academic context as Moon defined it. Because students in our course were not asked to record their findings immediately while designing, but to reflect afterwards, the concept of reflective learning is more appropriate in this case.

Reflection in action or on action

Similar to this distinction between experiential and reflective learning is the distinction between reflection-in-action (Schön 1982 ) and reflection-on-action (Schon 1987 ). Schön’s in the architectural world well received work from 1982 ‘The reflective practitioner’ describes based on only a few cases how professionals in general and architects in particular think while they do. Schön coins this as Reflection in Action (ibid: 54). He clearly distinguishes this from reflection-on-action that relates to the evaluation of the effects of the act according to predetermined goals (Schön 1987). Because we didn’t ask students to record their thoughts while designing but immediately afterwards and taking Schön’s distinction strictly, reflection-in-action is not applicable in our case but reflection-on-action is.

Regarding this reflection-on-action as we applied in our case a distinction can be made between analytical reflection and evaluative reflection (Cowan 2006 : p. 66, 81). Analytical reflection reflects on how e.g. things are done and evaluative reflection is ‘a process which leads to the making of a judgement in relation to a set of values or criteria, and one in which the judgement often leads to a consequent decision’ (ibid: 81). In this research paper 3 on the design process is an example of analytical and paper 4 an example of evaluative reflection. Although both types occur, they are not evaluated separately in this research.

Reflection in higher education

In literature on more or less similar courses as ours often no distinction is made between reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action. e.g. ‘becoming a reflective practitioner’ (Fry et al. 2003 : p. 215 etc.) assumes that learning how to reflect on action or reflective learning as defined by Moon, will develop reflection-in-action. In literature courses are described that assume to develop reflective practice by letting the student use direct reflective dialogue (Schön 1982 ) as a start to develop reflection on a higher level. Reflective dialogue is characteristic for e.g. the design process wherein ill-structured problems are contextualised and framed in an ‘inner dialogue’ between the design as designed by the designer and the designers thoughts about this design. e.g. Brockbank et al. ( 1989 ) describe the process by which student learners engage in critically reflective learning through reflective dialogue. They lean heavily on the theory of single- and double loop learning as proposed by Argyris ( 1977 ), where single loop learning as ‘instrumental learning which leaves underlying values and theories unchanged’ can provoke double loop learning as ‘learning where assumptions are challenged and underlying values are changed’ by questioning these assumptions (Brockbank et al. 1989 : p. 43, 45). In our course we asked the students first to register their design decisions in a log called ‘Design and Research-scheme’ and base their afterwards written reflections on that scheme.

Design can be described as reflection in action (Schön 1983). This is confirmed by Roozenburg and Dorst ( 1998 : p. 35) as they write ‘modelling design as reflection in action works particularly well for conceptual stages in a design process’. As indicated above, according to Schön (1983) distinctions can be made between reflection-in- and reflection-on-action; but also between reflection on the design and reflection on the design process. Congruent with it in our course the students were asked in their paper 2 for the benefit of reflecting on the design to generate knowledge over a particular design theme based on scientific literature and in their paper 3 to reflect on their own design process on the basis of five generic elements of Van Dooren et al. ( 2014 ). Both kinds of reflection, reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action are believed to contribute to the level of doing while designing (Van Dooren et al. 2017 ), exactly the reason why we organize the course Academic Design Reflection for our undergraduate students. Also the reason why we would like to know if the level of reflection of the students is rising while following this course. Hence our first research question: Does the level of reflection increases during the course?

Our course is the third 5EC course of a learning line called Academic Skills (AC; 3 × 5EC), consisting of a first year starting course in academic writing AC1, a second year Empirical Research Project AC2 and a third year course AC3 Academic Design Reflection. During the second and third year students are expected to use and deepen their acquired academic skills, such as academic writing, presenting, augmenting and underpinning, and evaluating and positioning in all kinds of design and research work in the other five learning lines: (1) Technology (5 × 5EC), (2) Fundamentals (4 × 5EC), (3) Society, Process and Practice (3 × 5EC), (4) Design (6 × 10EC), and (5) Visualisation, Representation and Form (3 × 5EC).

AC1 offers the student the overarching framework of how AUBS could be understood as a scientific discipline. In addition, the module provides very concrete academic skills, such as setting up and write a report of a literature review, the conventions of academic writing, searching in literature, presentation and debating skills. AC2 offers the student the knowledge and skills to an empirical research for the improvement of an existing design proposal to set up, perform, and report in a research report. The learning goal of AC3 is to relate research directly to design, and to take an argued position in this. AC3 Academic Design Reflection is a course that goes parallel to a 10EC design course, the sixth and final one before students can obtain their Bachelor degree. We explicitly work close together with the architectural supervisors and as a matter of fact we have the same groups of students that follow the design course in our group to teach them how to reflect in an academic way—that is using scientific knowledge and applying scientific ways of working- on their design. To reach the learning goal the student has to write 4 papers, one about the assignment, one about a self-chosen design theme, one on the design process and finally one on the relationship between design and research.

For instance and as indicated in “ Reflection in design education ” section, in the paper on the design process students use a framework particularly developed for making explicit in design education by Van Dooren et al. ( 2014 ). Van Dooren et al. provide an intermediate to make the communication between student and architectural supervisor about the students design effective. Key to this effectiveness is making things explicit. Based on research of the design process, on differences between novices and experts designers and on personal experience in design education practice, Van Dooren et al. have developed a conceptual framework consisting of five generic elements in the design process: (1) exploring and deciding, (2) guiding theme, (3) domains, (4) library of references, and (5) the design language. For the third paper in our research students were asked to reflect on their own design (process) based on these five elements.

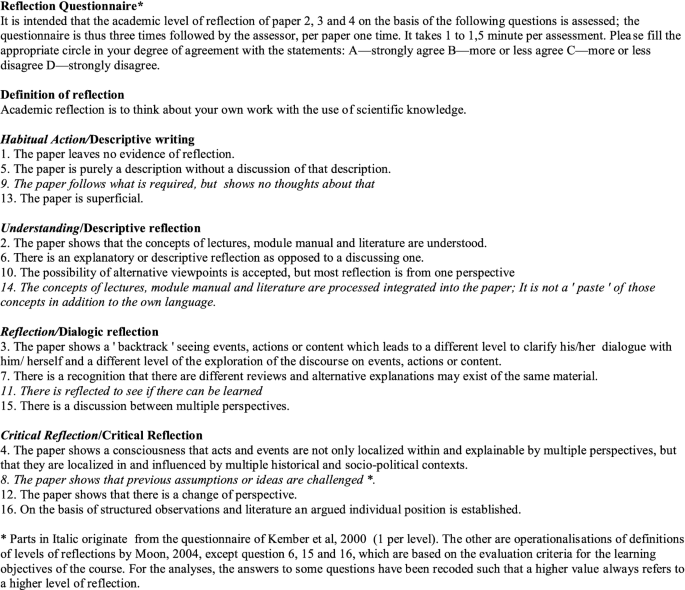

In the sequence of paper 1, 2, 3 and 4 we assume there is an increasing level of abstraction, hence in the level of reflection. To measure this level we adapted the four levels of reflection developed by Kember et al. ( 2000 ) and Moon ( 2004 : p. 96, 97)—descriptive writing, descriptive reflection, dialogic reflection, critical reflection. See Fig. 1 . To avoid misinterpretations we used a rather simple definition of academic reflection for the questionnaire: ‘Academic reflection is to think about your own work with the use of scientific knowledge’.

The design of the questionnaire

As in the questionnaire of Kember et al. ( 2000 ) we mixed Moon’s four levels of reflection by altering the sequence of questions. Italic questions are from the questionnaire of Kember et al. ( 2000 ) (1 per level). The other operationalisations are by definitions of level of reflection by Moon 2004 , except question 6, 15 and 16, which are based on the evaluation criteria of the learning objective of AC3: the students can reflect in an academic way on their own design project and design process.

We deliberately skipped the possibility of an answer between B and C in order to force a choice by the assessors. Finally we didn’t assume the four levels of reflection to correspond with our division in four papers and regarded the first paper as a kind of a finger exercise. Therefore, we decided to skip the first paper from the research and test the next three on their level of reflection.

The evaluation of the level of reflection of the papers was done by the own AC3-supervisor of the students group and a second AC3 supervisor of another group. So each paper was evaluated by two different evaluators.

Eventually we were interested into what extent it was correct to operationalize the four categories into the questions arranged under these categories. Hence our second research question is: can the operationalisation in our questionnaire of the definitions of reflection derived from theory statistically be confirmed?

Results for research question 1: Does the level of reflection increases during the course Academic Design Reflection?

As explained above, the responses to 16 questions were collected. The analyses for the first research question are performed on the composite sum scores, i.e., the general level of reflection. For this purpose, the homogeneity of the composite sum scores is tested, using Cronbach’s Alpha. The 16 questions show good homogeneity, as shown in Table 1 . Usually, a value for Cronbach’s α of 0.70 or higher is considered to reflect a reliable scale. Because of this result, the scores are summed over the responses to the 16 questions.

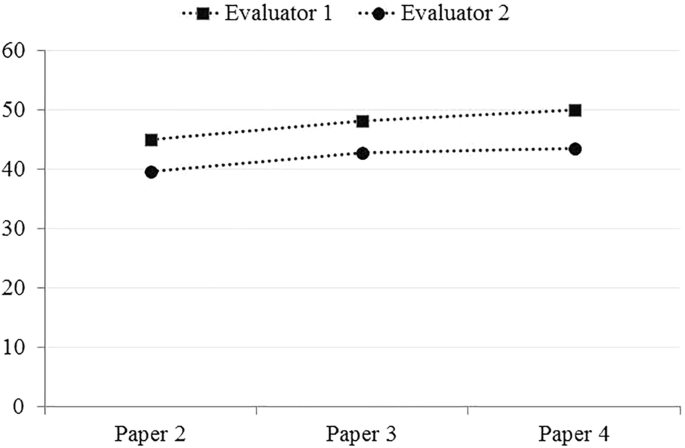

The mean sumscores for all three measurement points are provided in Table 2 . The dataset of paper 2 includes 293 cases, of which 155 concern the first evaluator and 138 the second evaluator. After deleting cases with only one evaluator, 129 students remain in the dataset, each of which is evaluated by two evaluators (258 cases). The sumscores range from 16 to 64 and the mean score is 41.9 (std = 10.5).

The dataset of paper 3 includes 297 cases, of which 157 concern the first evaluator and 139 the second evaluator (one is unknown). After deleting cases with only one evaluator, 131 students remain in the dataset (262 cases). The scores range from 20 to 64 and the mean score is 45.4 (std = 10.1).

The dataset of paper 4 includes 296 cases, of which 153 concern the first evaluator and 142 the second evaluator (one is unknown). After deleting cases with only one evaluator, 129 students remain in the dataset (258 cases). The scores range from 16 to 64 and the mean score is 46.9 (std = 11.0).

Table 2 shows that the mean sumscores increase between paper 2 and paper 3 and also between paper 3 and paper 4. This points to an increase in the students’ level of reflection. What is also shown is a difference in the mean evaluation of the first and the second evaluator. This difference is observed at all three measurement points.

The increase in the mean level of reflection over time can be statistically tested using a repeated measures analysis of variance. This is a statistical test that compares several means when these means have come from the same participants (Field 2013 : p 565). In our analysis, the mean sumscores for the students at the three measurement points are compared. This is called the “within-subjects” factor. We also included a variable in the analysis that indicated whether the sumscore was calcaluted for the first or for the second evaluator. This is called the “between-subjects” factor. For the examination of the scores over time it is important that only students are selected that have observations for both evaluators at each one of the three measurement points. This applies to 100 students.

The results for the 100 students are provided in Table 3 and in Fig. 2 . The results resemble the results described above for the total data set. The table shows that the mean sumscore increases over time. This result is supported by the repeated measures anova that shows that the mean sumscore differs statistically significantly over time ( p < 0.01). Furthermore, the table shows that the mean sumscore is higher for the first evaluator than for the second evaluator on each of the three measurement points. This effect is also statistically significant ( p < 0.01). Finally, there is no interaction effect between time and evaluator ( p = 0.48). This means that both first and second evaluator show a similar increase in mean scores over time. This can be clearly seen from Fig. 2 .

The increase of level of reflection in subsequently paper 2, 3 and 4 for both evaluators for students without missing observations (n = 100)

Based on Table 3 the total average of the level of reflection of the papers on a scale from 16 minimum to 64 maximum is 44.9.

Answering the first research question ‘Does the level of reflection increases during the course Academic Design Reflection?’ we conclude there is a statistically significant but slight increase of the level of reflection. Further we conclude that the scores of the first evaluator, who was also the supervisor of the student, are slightly higher than the more ‘neutral’ second evaluator. A statistical analysis of the differences in the average level of reflection between all groups of students was unjustified because all the groups were too small.

Finally we wanted to show the results of the analysis on the frequency of the scores (1, 2, 3 and 4) related to the classification that we made in four groups of questions: Descriptive Writing, Reflective Writing, Dialogic Reflection and Critical Reflection (see Fig. 1 ). The frequency of the scores related to the separate questions is statistical normal, meaning that the distribution shows a high frequency of the middle scores 2 and 3 and a low frequency of the extreme scores 1 and 4.

Results for research question 2: Can the operationalisation in our questionnaire of the definitions of reflection derived from theory statistically be confirmed?

For the second research question we explored whether the four levels of reflection that we adapted from the models by Kember et al. ( 2000 ) and Moon ( 2004 : p. 96, 97) could be confirmed in our dataset. This concerns the levels: Descriptive Writing, Reflective Writing, Dialogic Reflection and Critical Reflection (see Fig. 1 ). We used Cronbach’s Alpha to determine the reliability of the various levels, followed by a Principal Component Analyis (PCA) to check the assumed pattern of four different levels of reflection.

The results of the Cronbach’s Alpha test are presented in Table 4 . Taking into account that a scale is judged to be reliable when the coefficient for Cronbach’s Alpha is at least 0.70, all levels of reflection can be considered to have sufficient internal consistency.

To further falsify the validity of the division into four levels we executed an explorative factor analysis, i.e., Principal Components Analysis (PCA). A PCA is a statistical method that can be used to understand the structure of a set of variables (Field 2013 , p. 666). It means that we examined which pattern is prevalent in the sixteen responses to the questions. Responses to questions that highly correlate with each other form a “factor”. Multiple factors can be established. We performed the PCA for each of the three papers, including only cases for which two observations were present. The Varimax rotation method was used. This means that we obtained factors that are independent of each other and that are relatively easy to interpret (Field 2013 , p. 681).

The results showed that for all three measurement points, two factors could be discerned. Together these factors explain 61 (paper 2), 62 (paper 3) and 66 (paper 4) percent of the variance, which is a good result. The items that primarily and consistently load on one of the two factors are question: 1, 2, 3, 11, 14 and 16. This means that these items correlate relatively high with each other. The items relate to “evidence of reflection”, “understanding of the concepts of lectures, module manual and literature”, “the paper shows a backtrack”, “reflected to see if there can be learned”, “integration of lectures, module manual and literature” and “establishment of an argued individual position”. We read the descriptions of the six items carefully to search for a common underlying theme. However, we did not find such a theme. Furthermore, an inspection of these six items shows that they theoretically belong to all four different levels of reflection.

The items that primarily and consistently load on the other factor are question: 4, 6, 9 and 10. Two of these items (“no discussing reflection” and “most reflection is from one perspective”) theoretically belong to the same level of reflection, i.e., the Understanding/Descriptive reflection level. The other two items (“consciousness that acts and events are localized in and influenced by multiple historical and socio-political contexts” and “follows what is required”) belong to different levels. Again, we do not believe that these four items reflect an underlying common theme.

The other questions did not show consistent results; they sometimes showed the highest loading on the one factor and sometimes on the other factor.

Our results differ from the four factor-structure as hypothesized based on the theory of Moon ( 2004 ). First, our results pointed consistently to only two factors instead of four. Besides from that, the questions that made up the two factors differed from what was expected on the basis of the theory by Moon ( 2004 ) and the previous study by Kember et al. ( 2000 ). Moreover, we were unable to explain the results of the PCA, meaning that we could not find a theoretical or logical explanation for the supposed relationships between the items belonging to each one of the factors. Apparently, in this case, the operationalisations of Moon’s definitions and the operationalisations of the learning objectives of the course, do not match statistically with the classification of Moons and Kember et al.

So answering our second research question ‘Can the operationalisation in the questionnaire of the definitions of reflection derived from theory statistically be confirmed?’ we conclude that our model of classification is not statistically confirmed in the data.

The results from the Cronbach’s Alpha test and the PCA seem contradictory as quite reliable results were found with the first method, but the underlying structure could not be confirmed using PCA. We believe that this finding might be explained by the fact that all items show relatively high intercorrelations. This can also been seen from the high value of Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.94/0.95 that we presented for all sixteen items examined at once. Seen from a qualitative point of view, the setup of the questionnaire seems sensible, however not supported by statistical analysis. We assume that the multi interpretability of the questions plays an important role in this. Further research e.g. a test on the difference in interpretation of the questions by asking the evaluators to group the several questions into each of the four levels of reflection instead of giving it in advance, could provide insight.

Conclusions and implications

Conclusions.

Our research object was our Bachelor course in Academic Design Reflection. Two research questions were at hand: (1) does the level of reflection increase during our course and (2) Can the operationalisation in our questionnaire of the definitions of reflection derived from theory statistically be confirmed? The research shows that the average level of reflection of the students papers increases per successively paper and that the total average level of reflection of the papers is sufficient,. Further, we conclude that de scores of the first evaluator, who was also the supervisor of the student, are slightly higher than the more ‘neutral’ second evaluator. Finally the research shows that the classification of the questionnaire into four groups of questions with an ascending reflection level is not supported by statistical analysis, the model doesn’t fit the data, contrary to expectations based on literature. Further research is therefore required, but we already can say a number of things about the implications for our design education.

Implications for design education

Many of the TU Delft fields of engineering and design, such as architecture and the built environment, are positioned in the heart of the so called ‘practical sciences’ (Klaasen 2004 ; Rooij and Frank 2016 ) or ‘engineering sciences’ (Kamp 2016a , b ). Today’s and tomorrow’s complex socio-technical challenges in the built environment, such as sustainable, resilient, fair and healthy spatial development need well considered and integrated (design) solutions. These challenges are the backbone, the rationale and the motivation behind our Architecture &Built Environment academic sub disciplines and our curriculum specialisation tracks, such as architecture, urbanism, landscape architecture, building technology, and management in the built environment. The main knowledge question in our field therefore focuses to a large extent on ‘does it work?’ (e.g. a design, a plan, a solution proposal, a strategy) in contrast to empirical sciences which—via the construction of theories and the formulation of hypotheses—focus on the knowledge question ‘is it true?’.

This specific nature of built environment engineering education requires a specific set of academic design skills in order to (be able to) assess whether or not designs ‘work’. Important umbrella-skills are related to:

the critical assessment of design situations,

the creative development of meaningful design alternatives,

the thorough ex-ante evaluation of the design products,

the andante evaluation of dynamic design processes,

positioning yourself as designer and your design work in the academic and professional debate, and

relating design to (methods of) scientific research.

There is a call and a need from both inside and outside the faculty to significantly improve the academic skills of design students. At the Delft faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment this is for example apparent from quality assurance programmes (e.g. student questionnaires), dialogues with student bodies (e.g. student council and study association, Stylos) and the Board of Studies. Footnote 1 While students learn a lot from the current curricula, they also see room to raise the academic bar substantially. Teaching staff expresses similar views in education evaluation reports. The 2012 QANU visitation committee and the 2017 (self-organised) external audit committee advised the faculty to make better use of the academic design environment (defining it as a missed potential).

Students learn design best by doing —like most skills are learned best by doing them over and over again. But design might be understood better by academic reflection .

We showed that there is significant room for improvement for our bachelor design students. But this also holds for our master students. The faculty is convinced that such an academic reflection skills programme will only be successful, when it is closely related to, or even better, fully integrated into the design projects.

The A&BE faculty already works with a line of actions to evaluate, discuss and improve the academic skills programmes of our design curricula. Two key actions are relevant to present here. First. We are developing a (bilingual) book on Academic skills for architects (‘Academische vaardigheden voor bouwkundigen’) which will explicitly set the exit level of our undergraduate programme and at the same time the entrance level of our master (design) curricula. The idea is that the book will support the undergraduate students during their full 3 year bachelor programme. And it will not only be relevant for our students, but also a help for our design mentors as many of them—we work with a large body of design teachers from practice—explicitly ask for guidance in teaching academic skills and in particular design reflection. Second. We are redeveloping the academic skills programme of our 2 year master curriculum Architecture: both the first year research methods and/or methodology courses and the second year graduation project. For example: all final thesis students developing designs are asked to write a number of small papers reflecting on their graduation project during the year. They are assessed by the full mentor team, including the so called external examiner representing the faculty board of examiners. The structure is in place but still quite some work needs to be done for a fruitful delivery.

Implications for further research

We believe the total average score of reflection can be improved. We assume a higher level of reflection skills is both possible and desirable for our student body. We dedicate an important role to the teachers. The supervisors who take care of the reflection-education now in our course, are design supervisors who have had to learn reflection themselves as in their graduation training only minor attention was paid to their reflection skills. They would, however, be better trained in reflective thinking itself, but also as part of reflection in action. That should give the concept of reflection more depth and make it more clear for them. Instead of the out of educational considerations fairly simple definition of ‘ thinking about your own work ‘ that we have used here, in particular, more attention should be given to ‘(re)considering’ because ‘ reflection on action ‘ after all is about looking back.