If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 8

- John F. Kennedy as president

- Bay of Pigs Invasion

- Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis

- Lyndon Johnson as president

- Vietnam War

- The Vietnam War

- The student movement and the antiwar movement

- Second-wave feminism

- The election of 1968

- 1960s America

- In October 1962, the Soviet provision of ballistic missiles to Cuba led to the most dangerous Cold War confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union and brought the world to the brink of nuclear war.

- Over the course of two extremely tense weeks, US President John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev negotiated a peaceful outcome to the crisis.

- The crisis evoked fears of nuclear destruction, revealed the dangers of brinksmanship , and invigorated attempts to halt the arms race.

The Cuban Revolution

Origins of the cuban missile crisis, negotiating a peaceful outcome, consequences of the cuban missile crisis, what do you think.

- Sergo Mikoyan, The Soviet Cuban Missile Crisis: Castro, Mikoyan, Kennedy, Khrushchev, and the Missiles of November (Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2012), 225-226.

- Strobe Talbott, ed. Khrushchev Remembers (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1970), 494.

- See Michael Dobbs, One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev, and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War (New York: Random House, 2008); and Timothy Naftali and Aleksandr Fursenko, One Hell of a Gamble: Khrushchev, Castro, and Kennedy, 1958-1964: The Secret History of the Cuban Missile Crisis (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997).

- See James G. Blight and Philip Brenner, Sad and Luminous Days: Cuba’s Struggle with the Superpowers after the Cuban Missile Crisis (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002).

- Paul S. Boyer, Promises to Keep: The United States since World War II (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1999), 179.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Cuban Missile Crisis

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 20, 2023 | Original: January 4, 2010

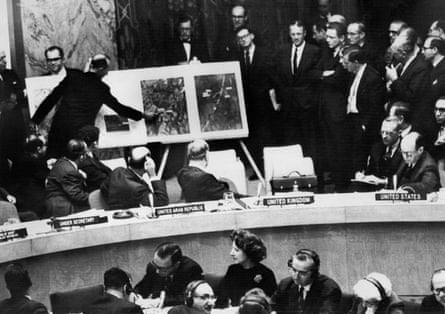

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, leaders of the U.S. and the Soviet Union engaged in a tense, 13-day political and military standoff in October 1962 over the installation of nuclear-armed Soviet missiles on Cuba, just 90 miles from U.S. shores. In a TV address on October 22, 1962, President John F. Kennedy (1917-63) notified Americans about the presence of the missiles, explained his decision to enact a naval blockade around Cuba and made it clear the U.S. was prepared to use military force if necessary to neutralize this perceived threat to national security. Following this news, many people feared the world was on the brink of nuclear war. However, disaster was avoided when the U.S. agreed to Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev’s (1894-1971) offer to remove the Cuban missiles in exchange for the U.S. promising not to invade Cuba. Kennedy also secretly agreed to remove U.S. missiles from Turkey.

Discovering the Missiles

After seizing power in the Caribbean island nation of Cuba in 1959, leftist revolutionary leader Fidel Castro (1926-2016) aligned himself with the Soviet Union . Under Castro, Cuba grew dependent on the Soviets for military and economic aid. During this time, the U.S. and the Soviets (and their respective allies) were engaged in the Cold War (1945-91), an ongoing series of largely political and economic clashes.

Did you know? The actor Kevin Costner (1955-) starred in a movie about the Cuban Missile Crisis titled Thirteen Days . Released in 2000, the movie's tagline was "You'll never believe how close we came."

The two superpowers plunged into one of their biggest Cold War confrontations after the pilot of an American U-2 spy plane piloted by Major Richard Heyser making a high-altitude pass over Cuba on October 14, 1962, photographed a Soviet SS-4 medium-range ballistic missile being assembled for installation.

President Kennedy was briefed about the situation on October 16, and he immediately called together a group of advisors and officials known as the executive committee, or ExComm. For nearly the next two weeks, the president and his team wrestled with a diplomatic crisis of epic proportions, as did their counterparts in the Soviet Union.

A New Threat to the U.S.

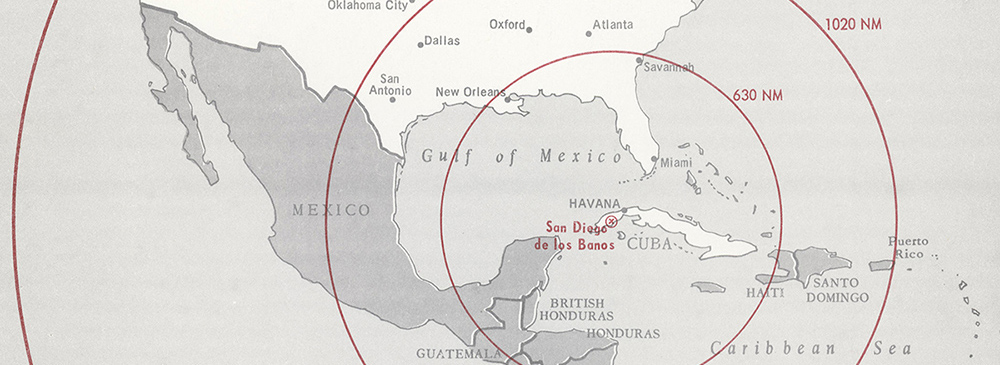

For the American officials, the urgency of the situation stemmed from the fact that the nuclear-armed Cuban missiles were being installed so close to the U.S. mainland–just 90 miles south of Florida . From that launch point, they were capable of quickly reaching targets in the eastern U.S. If allowed to become operational, the missiles would fundamentally alter the complexion of the nuclear rivalry between the U.S. and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), which up to that point had been dominated by the Americans.

Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev had gambled on sending the missiles to Cuba with the specific goal of increasing his nation’s nuclear strike capability. The Soviets had long felt uneasy about the number of nuclear weapons that were targeted at them from sites in Western Europe and Turkey, and they saw the deployment of missiles in Cuba as a way to level the playing field. Another key factor in the Soviet missile scheme was the hostile relationship between the U.S. and Cuba. The Kennedy administration had already launched one attack on the island–the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961–and Castro and Khrushchev saw the missiles as a means of deterring further U.S. aggression.

Watch the three-episode documentary event, Kennedy . Available to stream now.

Kennedy Weighs the Options

From the outset of the crisis, Kennedy and ExComm determined that the presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba was unacceptable. The challenge facing them was to orchestrate their removal without initiating a wider conflict–and possibly a nuclear war. In deliberations that stretched on for nearly a week, they came up with a variety of options, including a bombing attack on the missile sites and a full-scale invasion of Cuba. But Kennedy ultimately decided on a more measured approach. First, he would employ the U.S. Navy to establish a blockade, or quarantine, of the island to prevent the Soviets from delivering additional missiles and military equipment. Second, he would deliver an ultimatum that the existing missiles be removed.

In a television broadcast on October 22, 1962, the president notified Americans about the presence of the missiles, explained his decision to enact the blockade and made it clear that the U.S. was prepared to use military force if necessary to neutralize this perceived threat to national security. Following this public declaration, people around the globe nervously waited for the Soviet response. Some Americans, fearing their country was on the brink of nuclear war, hoarded food and gas.

HISTORY Vault: Nuclear Terror

Now more than ever, terrorist groups are obtaining nuclear weapons. With increasing cases of theft and re-sale at dozens of Russian sites, it's becoming more and more likely for terrorists to succeed.

Showdown at Sea: U.S. Blockades Cuba

A crucial moment in the unfolding crisis arrived on October 24, when Soviet ships bound for Cuba neared the line of U.S. vessels enforcing the blockade. An attempt by the Soviets to breach the blockade would likely have sparked a military confrontation that could have quickly escalated to a nuclear exchange. But the Soviet ships stopped short of the blockade.

Although the events at sea offered a positive sign that war could be averted, they did nothing to address the problem of the missiles already in Cuba. The tense standoff between the superpowers continued through the week, and on October 27, an American reconnaissance plane was shot down over Cuba, and a U.S. invasion force was readied in Florida. (The 35-year-old pilot of the downed plane, Major Rudolf Anderson, is considered the sole U.S. combat casualty of the Cuban missile crisis.) “I thought it was the last Saturday I would ever see,” recalled U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara (1916-2009), as quoted by Martin Walker in “The Cold War.” A similar sense of doom was felt by other key players on both sides.

A Deal Ends the Standoff

Despite the enormous tension, Soviet and American leaders found a way out of the impasse. During the crisis, the Americans and Soviets had exchanged letters and other communications, and on October 26, Khrushchev sent a message to Kennedy in which he offered to remove the Cuban missiles in exchange for a promise by U.S. leaders not to invade Cuba. The following day, the Soviet leader sent a letter proposing that the USSR would dismantle its missiles in Cuba if the Americans removed their missile installations in Turkey.

Officially, the Kennedy administration decided to accept the terms of the first message and ignore the second Khrushchev letter entirely. Privately, however, American officials also agreed to withdraw their nation’s missiles from Turkey. U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy (1925-68) personally delivered the message to the Soviet ambassador in Washington , and on October 28, the crisis drew to a close.

Both the Americans and Soviets were sobered by the Cuban Missile Crisis. The following year, a direct “hot line” communication link was installed between Washington and Moscow to help defuse similar situations, and the superpowers signed two treaties related to nuclear weapons. The Cold War was and the nuclear arms race was far from over, though. In fact, another legacy of the crisis was that it convinced the Soviets to increase their investment in an arsenal of intercontinental ballistic missiles capable of reaching the U.S. from Soviet territory.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Cuban Missile Crisis

For thirteen days in october 1962 the world waited—seemingly on the brink of nuclear war—and hoped for a peaceful resolution to the cuban missile crisis..

In October 1962, an American U-2 spy plane secretly photographed nuclear missile sites being built by the Soviet Union on the island of Cuba. President Kennedy did not want the Soviet Union and Cuba to know that he had discovered the missiles. He met in secret with his advisors for several days to discuss the problem.

After many long and difficult meetings, Kennedy decided to place a naval blockade, or a ring of ships, around Cuba. The aim of this "quarantine," as he called it, was to prevent the Soviets from bringing in more military supplies. He demanded the removal of the missiles already there and the destruction of the sites. On October 22, President Kennedy spoke to the nation about the crisis in a televised address.

Click here to listen to the Address in the Digital Archives (JFKWHA-142-001)

No one was sure how Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev would respond to the naval blockade and US demands. But the leaders of both superpowers recognized the devastating possibility of a nuclear war and publicly agreed to a deal in which the Soviets would dismantle the weapon sites in exchange for a pledge from the United States not to invade Cuba. In a separate deal, which remained secret for more than twenty-five years, the United States also agreed to remove its nuclear missiles from Turkey. Although the Soviets removed their missiles from Cuba, they escalated the building of their military arsenal; the missile crisis was over, the arms race was not.

Click here to listen to the Remarks in the Digital Archives (JFKWHA-143-004)

In 1963, there were signs of a lessening of tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States. In his commencement address at American University, President Kennedy urged Americans to reexamine Cold War stereotypes and myths and called for a strategy of peace that would make the world safe for diversity. Two actions also signaled a warming in relations between the superpowers: the establishment of a teletype "Hotline" between the Kremlin and the White House and the signing of the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty on July 25, 1963.

In language very different from his inaugural address, President Kennedy told Americans in June 1963, "For, in the final analysis, our most basic common link is that we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children's future. And we are all mortal."

Visit our online exhibit: World on the Brink: John F. Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis

National Archives News

Cuban Missile Crisis

At the height of the Cold War, for two weeks in October 1962, the world teetered on the edge of thermonuclear war. Earlier that fall, the Soviet Union, under orders from Premier Nikita Khrushchev, began to secretly deploy a nuclear strike force in Cuba, just 90 miles from the United States. President John F. Kennedy said the missiles would not be tolerated and insisted on their removal. Khrushchev refused. The standoff nearly caused a nuclear exchange and is remembered in this country as the Cuban Missile Crisis. For 13 agonizing days—from October 16 through October 28—the United States and the Soviet Union stood on the brink of nuclear war. The peaceful resolution of the crisis with the Soviets is considered to be one of Kennedy’s greatest achievements.

Events in October 2022

- Friday, October 14, at 1 p.m.: The Abyss: Nuclear Crisis Cuba 1962 (author lecture, online only)

- Saturday, October 22, at 1 p.m. and 3 p.m: The Cuban Missile Crisis: Lessons for Today (conference, in person and online)

Research Resources

- Military Resources: Bay of Pigs Invasion & Cuban Missile Crisis

- John F. Kennedy Library Research Subject Guide: Cuban Missile Crisis

- Cuban Missile Crisis Chronology

- Department of Defense Cuban Missile Crisis Briefing Materials

- CIA-prepared personality studies of Nikita Khrushchev and Fidel Castro

- Satellite images of missile sites under construction

- Secret correspondence between Kennedy and Khrushchev

- National Archives Catalog Subject Finding Aid for Cuban Missile Crisis (Still Picture Branch)

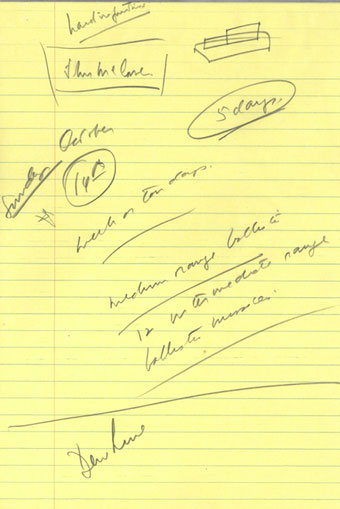

- JFK’s doodles from October 1962

- Aerial Photograph of Missiles in Cuba (1962) , Milestone Documents

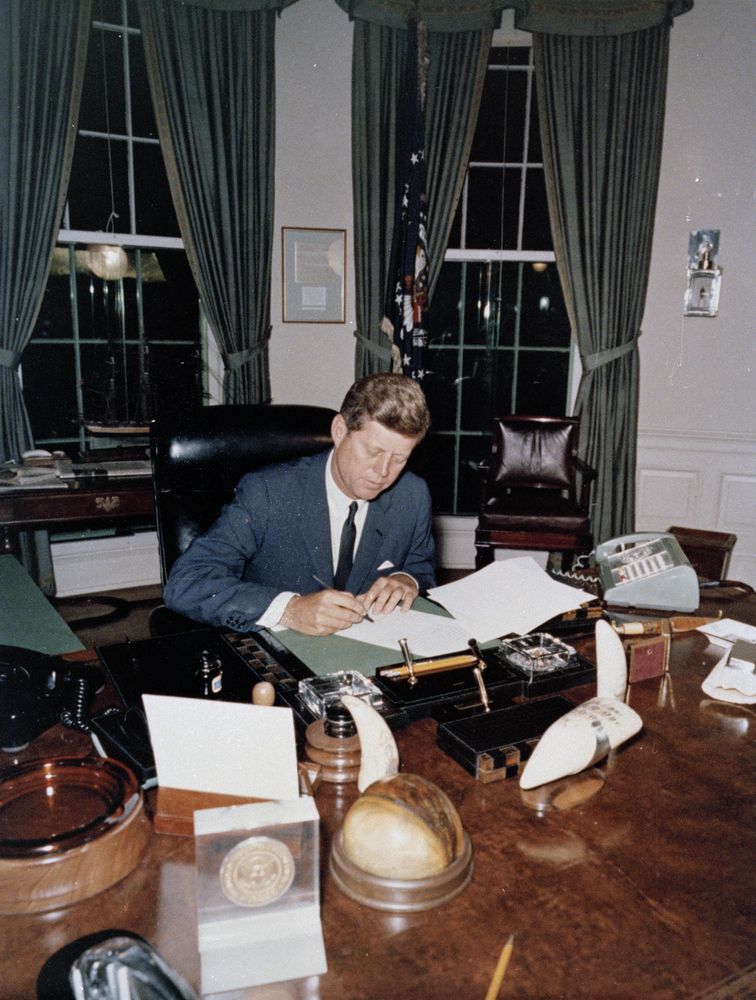

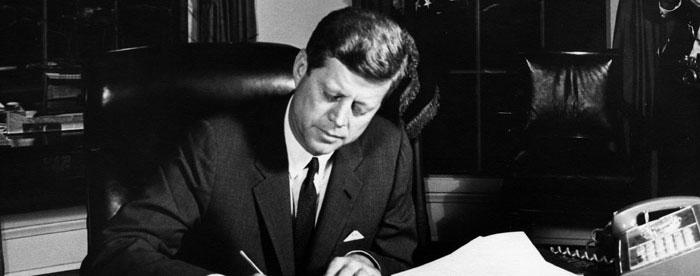

President John F. Kennedy signs the Cuba Quarantine Order, October 23, 1962. ( Kennedy Library )

Audio and Video

- President Kennedy’s radio and television address to the American people on the Soviet arms build-up in Cuba, October 22, 1962

- President Kennedy’s radio and television remarks on the dismantling of Soviet missile bases in Cuba, November 2, 1962

- Telephone conversation between President Kennedy and former President Eisenhower, October 28, 1962

- Telephone recordings, Cuban Missile Crisis Update, October 22, 1962

- Atomic Gambit: JFK Library podcast for 60th anniversary

- Poise, Professionalism and a Little Luck, the Cuban Missile Crisis 1962 (panel discussion)

- Nuclear Folly: A History of the Cuban Missile Crisis (author lecture)

Kennedy Library Forums

- Cuban Missile Crisis: An Historical Perspective (October 6, 2002)

- On the Brink: The Cuban Missile Crisis (October 20, 2002)

- The Cuban Missile Crisis: An Eyewitness Perspective (October 17, 2007)

- Presidency in the Nuclear Age: Cuban Missile Crisis and the First Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (October 12, 2009)

- 50th Anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis (October 14, 2012)

Articles and Blog Posts

- One Step from Nuclear War - The Cuban Missile Crisis at 50 (Prologue)

- Forty Years Ago: The Cuban Missile Crisis (Prologue)

- Cuban Missile Crisis, Revisited (Text Message blog)

Education Resources

- The Cuban Missile Crisis: How to Respond? (high school curriculum resource)

- World on the Brink: JFK and the Cuban Missile Crisis (online exhibit)

Find answers to your questions on History Hub

United States Institute of Peace

Home ▶ Publications

Looking Back on the Cuban Missile Crisis, 50 Years Later

Friday, October 19, 2012 / By: Bruce W. MacDonald

Publication Type: Analysis

Fifty years ago this month, world attention was fixed on a U.S.-Soviet confrontation over the placement of Soviet nuclear-armed missiles in Cuba, probably the most dangerous and perhaps the most studied moment of the Cold War. This iconic crisis has left us a legacy of lessons and insights for the future, many only recognized in recent years as previously classified materials have become available.

The crucial role of diplomacy in peacefully resolving this historic test of Cold War wills is described here by Bruce W. MacDonald, senior adviser to the Nonproliferation and Arms Control Program with the U.S. Institute of Peace’s Office of Special Initiatives. In this capacity, MacDonald developed and leads instruction of 21st Century Issues in Strategic Arms Control and Nonproliferation , a series of courses for USIP’s Academy for International Conflict Management and Peacebuilding , and advises on issues related to nuclear, space, and cyber strategy and policy as well as missile defense, arms control and nonproliferation. Earlier, he was senior director of the Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States , a bipartisan body headed by former Defense Secretaries William Perry and James Schlesinger. MacDonald has also served at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, the National Security Council, the staff of the House Armed Services Committee and the State Department’s Bureau of Political-Military Affairs.

What was the Cuban Missile Crisis all about?

Based on what we now know—as more and more previously closely-held information from both sides has become available—we can see that the United States and the USSR were coming from quite different perspectives. In the fall of 1962, the Soviet Union, led by Premier Nikita Khrushchev, saw itself in an increasingly precarious strategic situation. Facing a wide and still growing U.S. advantage in nuclear weapons, especially those that could strike the Soviet homeland, and ringed by many U.S. nuclear bomber bases within allied countries around the USSR’s perimeter, the Politburo in Moscow believed it needed to take a dramatic step. That perception was reinforced by the failed invasion of Cuban exiles at Cuba’s Bay of Pigs, reinforcing Soviet views that the United States would invade the USSR’s one ally in the Western Hemisphere. So Khrushchev decided to position medium-range nuclear-armed missiles in Cuba, increasing the threat to the United States and thus strengthening the Soviet ability to deter American actions—such as invading Cuba—that worried Soviet leaders.

President John Kennedy considered such a new threat intolerable and outrageous, as well as a complete surprise. The Soviets conducted their missile deployments in secret and lied to the U.S. government about them; the missiles were only discovered by U.S. intelligence after the deployment process was well underway. From an American perspective, in the early 1960s the Soviets and their proxies were pushing forward on all fronts—Berlin, Southeast Asia, Africa and Cuba—to advance their own area of control and spheres of influence, while the United States had foresworn any effort to “roll back” communism. As it became clear that Fidel Castro, who had seized power in Cuba in 1959, was a Communist and a Soviet ally, the impression in the United States was that the Soviets were pressing forward across the globe and trying to outflank America in the Western Hemisphere. Consequently, Kennedy ordered a U.S. “quarantine” of Cuba before additional, longer-range Soviet missiles could be shipped to Cuba. Both countries substantially raised their nuclear-alert levels, and the world quickly moved toward the precipice of all-out nuclear war.

What made the crisis really dangerous?

Both sides had much at stake. The United States suddenly faced a significant escalation of the nuclear threat from the USSR, and the American public would expect and demand Washington to take action. In addition, many countries relied on the United States for security guarantees; if the United States took no action to so direct a threat to its own homeland, that could undercut belief that Washington would honor its security commitments to others. The Soviet Union, having made this move, was very reluctant to back down, both for its own global reasons and because doing so could undercut Castro. With so much at stake, and nuclear weapons at the core of the controversy, all-out nuclear war became a real possibility—by design or by miscalculation. The Cuban missile crisis was the closest the world has ever come to nuclear war.

How close did we come to nuclear war?

We’ll never really know, but the indications were ominous. During the crisis, the United States raised its nuclear war footing to the highest level it has ever been (DEFCON 2), one step below “nuclear war is imminent.” U.S. nuclear-armed bombers were placed on airborne alert, and some of the Soviet missiles and bombers in Cuba were not under the direct control of senior leadership in Moscow and thus could have been launched by less cautious military officers. It would not have taken much of a misunderstanding or misinterpreted command to trigger at least an isolated use of nuclear weapons, which could then have ignited a full nuclear exchange. Some participants in the crisis believed they might not ever see their loved ones again.

What were the key elements in resolving the crisis?

There were several, which are also common to resolving other crises and conflict situations today.

- The first: Buy time to give diplomacy a chance to work, which entails refraining from the direct use of force but not taking that option off the table. Kennedy’s decision to impose a “quarantine,” (an actual “blockade” could have been considered an act of war) of Cuba meant that a number of days would pass before additional Soviet ships with more missiles would approach the island and a confrontation between U.S. and Soviet naval forces could occur. Kennedy ruled against military advice to use conventional weapons to bomb the missile sites at this stage, a move that would have caused Russian and Cuban casualties and further escalated the crisis. The quarantine Kennedy chose was an option that demonstrated U.S. resolve but created space for intense bilateral diplomacy to find solutions to the crisis before those additional missile-carrying Soviet ships would arrive at Cuba. High-level, high-intensity diplomacy, both formal and informal, could and did proceed.

- The second element was the willingness of each side to allow the other a face-saving way out of the crisis. For the United States, the Soviet missiles had to be removed. For the Soviet Union, something had to be done to provide at least the appearance of addressing both the U.S.-Soviet strategic imbalance and concerns about a U.S. invasion of Cuba. In the solution reached, the Soviets removed the missiles already deployed in Cuba, and Soviet ships under sail with missile cargoes returned to Soviet ports. In return, the United States agreed to remove a squadron of already obsolete medium-range Jupiter missiles based in Turkey as long as that part of the deal was kept secret. In addition, the United States publicly pledged it would not invade Cuba. The compromise was not painless: Cuba was not happy with only a U.S. pledge on paper not to invade, and Turkey had believed that the Jupiter missiles improved their security. Both the Soviet Union and the United States recognized that much larger issues were at stake and managed their allies’ concerns in other ways. Thus, both sides emerged from the crisis with their core concerns intact, though public perception at the time saw the United States as the greater winner.

- The fourth, and somewhat surprising, element was the willingness of top leadership on both sides, at last, to come to grips with the devastating consequences of a nuclear war. Senior civilian leadership in Washington and Moscow realized that a way had to be found to avoid nuclear war, which resulted in compromises that under lesser pressures may not have been politically feasible. While all recognized that nuclear war would be devastating, this was probably the first time that leaders had to look at the monster of nuclear war straight in the eye—and they both feared what they saw.

What was the aftermath of the crisis?

The Cuban missile crisis both directly and indirectly led to a number of improvements in the international strategic environment, including agreements to begin to restrain the competition in nuclear arms. One of the first results was the establishment of the Washington-Moscow “hotline” less than seven months after the crisis, giving leaders of both countries a direct link during crises and thereby reducing chances for misunderstanding. This hotline continues in operation to this day.

In addition, the following year the United States and the Soviet Union signed an agreement to ban above-ground nuclear testing. While this pact was also driven by increasing worldwide concerns over radioactive nuclear fallout in milk and other food supplies, a desire to reduce nuclear threats was the overriding factor. Over the following few years, the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), designed to halt the spread of nuclear weapons to other countries, was negotiated and signed, and the United States and Soviet Union took their first direct steps in nuclear arms control, starting with diplomatic discussions and then a summit in Glassboro, New Jersey, in 1967. Late 1969 saw the beginning of negotiations that led to the first Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT I) and the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty. The outcome was also a shot in the arm for U.S. diplomacy more generally and reinforced the notion that effective diplomacy has a central role to play in U.S. security policy.

What lessons from the crisis are relevant today, and how might those lessons influence nuclear peacemaking in the years ahead?

One is the need to avoid major strategic surprise. Where a country’s vital national interests are concerned, strategic surprise can be destabilizing and lead to rushed and possibly unwise decisions by the surprised party. Second is the need to identify one’s own core interests that need to be protected and one’s objectives in interactions with an opponent, along with the need to convey as much clarity on them as possible with one’s opponent. Third, it is essential that each party in a nuclear interaction put itself in the shoes of its opponent and ask why that country is behaving the way that it is. As successful as the missile crisis outcome was, more than one scholar has noted the failure of Kennedy and his senior advisers to ponder more fully why the Soviet Union was introducing the missiles to Cuba in the first place. This does not mean that the Soviet Union should have been allowed to do so, but understanding where the Soviets were coming from would have added clarity in choosing among Washington’s diplomatic and military options. Clearly, the Soviets also had not thought through how the Americans would react if their clandestine scheme came to light. Further, each party needs to emerge from a high-stakes confrontation with a face-saving outcome. A confrontation can come to be seen as an end in itself, without recognition that other issues in the future will be indirectly influenced by the outcome of a current crisis. Knowing that the other side is not bent on absolute triumph and humiliation of the adversary improves the chances for win-win outcomes in the future.

In major-power confrontations, a strong military posture is essential for a country and can favorably influence diplomacy, as the American fleet did in this case. But it should always be used in support of diplomatic and political goals, and resorts to actual armed action should generally be considered as a later-stage instrument to be drawn upon only as necessary. Premature recourse to what are now called “kinetic” operations can spark premature escalation and poor decision making. Skillful diplomacy can also make military issues easier to resolve when military steps are required, such as winning agreement by allies and others to assist. The tendency in a complex crisis to take the seemingly easy way out with a quick turn to military force should be avoided, and time allowed to give diplomacy a chance. As Winston Churchill, who understood better than most that under extreme circumstances war can be necessary, observed late in his life, “to jaw-jaw always is better than to war-war.”

Related Publications

Lavrov in Latin America: Russia’s Bid for a Multipolar World

Thursday, April 27, 2023

By: Kirk Randolph

This past week, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov completed a four-country tour of Latin America to reinforce Moscow’s alliances and foster growing partnerships in the region. During the trip, Lavrov met with the heads of state of Brazil, Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba in their respective countries, as well as another meeting with Bolivian emissaries during his stop in Venezuela. Lavrov used the opportunity to emphasize the key tenet of Russia’s newest foreign policy concept that was launched in the past month and is shared by regional powers like Brazil: The world is experiencing a revolution in which Western power is weakening and a new multipolar world is emerging.

Type: Analysis

Global Policy

U.S. National Security Chiefs Talk Leadership, Partners

Wednesday, January 11, 2017

By: USIP Staff

The national security advisors to President Barack Obama and President-elect Donald Trump stood shoulder-to-shoulder on a stage at the U.S. Institute of Peace yesterday and shook hands to a standing ovation at a two-day conference on foreign and national security policy. In speeches, National Security Advisor Susan Rice and her designated successor, retired U.S. Army Lieutenant General Michael Flynn, struck a tone of cooperation on the transition between administrations.

Summit of the Americas

Thursday, April 5, 2012

By: Virginia M. Bouvier

The theme of the sixth summit of the Americas to be held in Cartagena, Colombia from April 14-15, 2012, is “Connecting the Americas: Partners for Prosperity.” USIP's Colombia expert, Virginia Bouvier, previews the summit.

Conflict Analysis & Prevention ; Environment ; Economics

On the Issues: Iran and P5+1 Talks

Tuesday, January 18, 2011

By: Dan Brumberg

USIP expert Dan Brumberg previews the upcoming talks with Iran and provides background on the current situation.

Help inform the discussion

JFK and the Cuban Missile Crisis

Listen in on the signature crisis of JFK's presidency

The Cuban Missile Crisis was the signature moment of John F. Kennedy's presidency. The most dramatic parts of that crisis—the famed "13 days"—lasted from October 16, 1962, when President Kennedy first learned that the Soviet Union was constructing missile launch sites in Cuba, to October 28, when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev publicly announced he was removing the missiles from the island nation.

Tensions continued, however, until November 20, when Kennedy lifted the blockade he had placed around Cuba after confirming that all offensive weapons systems had been dismantled, and that Soviet nuclear-capable bombers were to be removed from the island.

The potential for a nuclear war was real, and the following Miller Center exhibits from our Kennedy collection capture the president's thoughts and the advice he was receiving.

Date : Oct 19, 1962 Time : 9:45 a.m. Participants : John Kennedy, Curtis LeMay

While discussing various options for dealing with the threat posed by Soviet missiles in Cuba, Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. Curtis E. LeMay, after criticizing calls to blockade the island, sums up the president's political and military troubles.

Date: Oct 22, 1962 Participants: John Kennedy, Dwight Eisenhower

President Kennedy had taken pains to be sure Eisenhower was briefed on the Cuban Missile Crisis by John McCone, first on October 17 to give him the news of the deployment and then again on October 21 to tell the former president about the blockade-ultimatum decision. Having already heard from McCone about Eisenhower's supportive reaction, President Kennedy wants to discuss his dilemma directly with one of the few living men who will truly understand what he faces. Despite the distance between the two men in age, experience, and political stance, it is not the first time they have confided in each other, and it will not be the last.

Date : Oct 24, 1962 Time : 10:00 a.m. Participants : John F. Kennedy, McGeorge Bundy, C. Douglas Dillon, Roswell Gilpatric, U. Alexis Johnson, Robert Kennedy, Robert G. Kreer, Arthur Lundahl, John McCone, General McDavid, Robert McNamara, Paul Nitze, Kenneth O’Donnell, Dean Rusk, Theodore Sorensen, Maxwell Taylor, Jerome Wiesner

In this recording, President Kennedy consults with the Executive Committee of the National Security Council (commonly referred to as simply the Executive Committee or ExComm) about possible reactions to the growing Cuban Missile Crisis.

Date : Oct 26, 1962 Time : 9:59 a.m. Participants : John F. Kennedy, McGeorge Bundy, C. Douglas Dillon, Roswell Gilpatric, U. Alexis Johnson, Robert Kennedy, Robert G. Kreer, Arthur Lundahl, John McCone, General McDavid, Robert McNamara, Paul Nitze, Kenneth O’Donnell, Dean Rusk, Theodore Sorensen, Maxwell Taylor, Jerome Wiesner

In this recording, President Kennedy consults with the ExComm about the unfolding of the Cuban Missile Crisis and how the situation might be resolved.

Date : Oct 26, 1962 Time : 6:30 p.m. Participants : John F. Kennedy, Harold Macmillan

Kennedy placed this call after having held crisis meetings with advisers all day. Macmillan received the call around midnight London time. U Thant, acting secretary-general of the United Nations, had been holding round-the-clock talks in New York. In the latest development, US Ambassador to the United Nations, Adlai Stevenson, had met with U Thant earlier that day in New York. U Thant, in turn, had been talking Soviet Ambassador to the United Nations Valerian Zorin.

Date : Oct 27, 1962 Time : 4:00 p.m. Participants : John F. Kennedy, McGeorge Bundy, Alexis Johnson

President Kennedy and his advisers consider the ramifications of trading Jupiter missiles in Turkey for Soviet missiles in Cuba.

Epic Misadventure

"who would want to read a book on disasters”.

Miller Center expert Marc Selverstone examines Kennedy's foreign policy struggles

Cuban Missile Crisis Management Essay

Introduction, managing of cuban missile crisis, reference list.

The Cuban Missile Crisis was a battle that arose between the United States, Cuba and Soviet Union in 1962. United States unsuccessful efforts to overthrow Cuban regime (Operation Mongoose) prompted Soviet to furtively erect bases in Cuba to provide medium and intermediate range of airborne nuclear artilleries to prove to the world its military supremacy.

The artilleries had a capability of striking continental America. The installation of missiles in Cuba was a Soviet mission done privately to facilitate surprise attack to continental America (White, 1997, p.69).

The US administration of the time believed that Moscow‘s activities in Cuba were a threat to International security, hence; the ballistic missiles deployed in Cuba enhanced a major security blow to the leadership of United States. To curb potential danger caused by the situation, John F. Kennedy effected strategies which proved useful in calming the situation

Managing the Cuban Missile Crisis was a complex issue by John F. Kennedy administration. Perhaps, the United States intelligence was convinced that Soviet would not succeed in installing nuclear missiles in Cuba. However, this was not the case; the Soviet had gone ahead and installed the missiles without prior knowledge of United States security intelligent.

To mitigate the risk, the Kennedy administration discussed various options to reduce the likelihood of a full blown crisis. Mitigation measures adopted included; military, quarantine and diplomacy among other measures

The John Kennedy administration embraced using military to designate Missile sites in Cuba by using military prowess. United States Military interventions were well developed thus the Kennedy administration found it easy to order posting to strategic sites on the Atlantic Ocean. Besides, the Army, marine, and navy had a tough program if they were not engaged; they were systematically ordered to the sea (White, 1997, p.79).

Concentrated air monitoring in Atlantic was instigated, tracking more than 2,000 foreign ships in the area. The government was determined in case the Soviet Union launched nuclear assault; United States military was standby to answer.

Beginning 20th October, 1962, The United States’ Strategic Air Command began diffusing its aircraft, fully equipped on an upgraded alert. According to White (1997, p.109), heavy aircraft such as B-52 began a significant aerial vigilance that involved 24 hour flights and instant standby response for every aircraft that landed.

Besides, Intercontinental Ballistic Missile troops assumed analogous vigilant authority. Moreover, the POLARIS submarines were deployed to reassigned locations in the sea bordering United States and Cuba. The supreme nuclear weapons of Kennedy administration were installed to forestall any hasty battle poised by the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Divine (1998,p.97) points out that United States air defense troops, under the operational control of North America Defense Command, were also organized. Combatant interceptors, NIKE-HERCULES and HAWK missile hordes, were tactically relocated to southeast part to enhance local air defense (White, 1997, p.118).

The John Kennedy constituted its Air Force, Army and Navy in October. When command organizations were officially constituted, the Commander in Chief Atlantic was chosen to lead the team and provide a unified authority.

The John F. Kennedy administration implemented all these plans through the Joint Chiefs of Staff who later named Chief of Naval Operations to administer all necessary actions and subsequent execution.

Military intervention instituted by John Kennedy administration deterred Soviet Union intention of installing Missile center in Cuba of which would have posed a serious threat not only to America but entire America’s continent (Divine, 1998, p.123).

The John F. Kennedy administration imposed a quarantine to exert more pressure on Soviet Union with a view of subverting possible war. This was one of the flexible methods unlike others that US government embraced. Quarantine was aimed at constraining buildup of offensive military weapons en-route to Cuba.

To thoroughly execute the strategy, all kinds of ships en-route to Cuba from whichever country or port were scrutinized to confirm the presence of aggressive artilleries. Byrne (2006, p.29) explains that if toxic artillery were located, the ship was forced to unwind the voyage or risk being confiscated.

This quarantine was stretched to other kinds of cargoes and carriers. Quarantine provided more opportunity to Soviet Union to reconsider their position and destroy all offensive military apparatus in Cuba. Quarantine was believed as a precise strategy in solving the Cuban Missile Crisis because, the US government thought that it will be easier to start with a limited steps towards stringent measures for implementation (Byrne, 2006, p 86).

Though it started at a low pace, it exerted more pressure on Soviet Union thus yielding to United States demands. This proved to be an effective strategy. Soviet Union sentiment was that United States was contravening international law.

However, it was hard for the Soviet to test the applicability of this strategy. They knew if they dare rise the situation at hand would become even worse. The Soviets acknowledged installing missiles in Cuba to secure it against the US invasion. The Kennedy administration accordingly accepted to invade Cuba.

John Kennedy and ExComm (John F. advisers) team prodded every probable diplomatic system to truncate a nuclear holocaust. The Cuban Missile Crisis deepened diplomatic relations between the United States and Soviet Union with a choice of evading more emergency or perhaps war.

According to Byrne (2006, p.125), Kennedy himself was skillful and embraced compulsion to gain a diplomatic success. He sustained emphasis upon Khrushchev vehemently but adeptly. Potency was used shrewdly by Kennedy administration as a powerful, discreet component to urge Soviets cede the plan without embarrassment. His persistence was unwavering.

United States and the Soviet exchanged letters and intensified communication both formal and informal. The Soviet through Khrushchev dispatched letters to Kennedy administration explaining the circumstances of Missiles in Cuba and peaceful intention of Soviet Union.

Further, diplomatic efforts were strengthened by more letters from Soviet Union explaining the intent of dismantling the missile installations in Cuba and subsequent personnel relocation. This was only after United States dismantled its missile it had installed in Italy and Turkey.

Kennedy’s respond to crisis diplomacy is lauded as a contributory factor which barred the Cuban Missile Crisis resulting in nuclear conflict.

Byrne (2006, p.132) alleges that, if Kennedy’s responses were altered, it would have led to another world war. hence his diplomatic finesse succeeded in convincing Soviet Union to dismantle its Missiles in Cuba under United Nations supervision whereas the honoring its commitment in removing its missile installations in the continental Europe.

John F. Kennedy administration amicably responded to Cuban Missile Crisis in an effective way. Measures undertaken such as; military intervention, quarantine and skillful diplomacy necessitated subversion of the crisis.

Failure of which would have resulted in another World War. Besides, the plans facilitated the Kennedy administration to effectively prove to the world it was capable of handling similar magnitude of threats to enhance world peace and security.

Byrne, P. J. (2006). The Cuban Missile Crisis: To the Brink of War , Minneapolis: Compass Point Books

Divine, R. A. (1988). The Cuban Missile Crisis. New Jersey: Markus Wiener Publishers

White, M. J. (1997). Missiles In Cuba: Kennedy, Khrushchev, Castro, And The 1962 Crisis , Texas: University of Texas

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, April 13). Cuban Missile Crisis Management. https://ivypanda.com/essays/cuban-missile-crisis-essay/

"Cuban Missile Crisis Management." IvyPanda , 13 Apr. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/cuban-missile-crisis-essay/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Cuban Missile Crisis Management'. 13 April.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Cuban Missile Crisis Management." April 13, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/cuban-missile-crisis-essay/.

1. IvyPanda . "Cuban Missile Crisis Management." April 13, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/cuban-missile-crisis-essay/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Cuban Missile Crisis Management." April 13, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/cuban-missile-crisis-essay/.

- The Cuban Missile Crisis: The Causes and Effects

- "The Secret" by Rhonda Byrne

- The Soviet Union Missiles Deployment in Cuba

- USSR's Missiles on Cuba: Protection or Provocation

- The Secret by Rhoda Byrne

- Cuban Missile Crisis and Administrations Negotiation

- Cuban Missile Crisis: Why Was There No War?

- Cuban Missile Crisis: Three Men Go to War - History in Documentaries

- Cuban Missile Crisis Documentary

- The United States Confrontation to Communism

- The Role of Sea Power in International Trade

- History of Modern South Africa Began With the Discovery of Diamonds and Gold

- The Survival of the Sotho Under Moshoeshoe

- Lessons Learned From the History of the Marshall Plan About the Importance of the USA in the Process of European Integration

- Total War in Modern World History

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Cuban missile crisis, 60 years on: new papers reveal how close the world came to nuclear disaster

In 1962, a Soviet submarine commander nearly ordered a nuclear launch, newly translated accounts show, with modern parallels over Ukraine all too clear

T he commander of a nuclear-armed Soviet submarine panicked and came close to launching a nuclear torpedo during the Cuban missile crisis 60 years ago, after being blinded and disoriented by aggressive US tactics, according to newly translated documents.

Many nuclear historians agree that 27 October 1962, known as “Black Saturday”, was the closest the world came to nuclear catastrophe, as US forces enforced a blockade of Cuba to stop deliveries of Soviet missiles. On the same day a U-2 spy plane was shot down over the island, and another went missing over Siberia when the pilot lost his way.

Six decades on from the “world’s most dangerous day”, last week’s revelation that a Russian warplane fired a missile near a British Rivet Joint surveillance plane over the Black Sea has once more heightened concerns that miscalculation or accident could trigger uncontrolled escalation.

In October 1962, the US sent its anti-submarine forces to hunt down Soviet submarines trying to slip through the “quarantine” imposed on Cuba. The most perilous moment came when one of those submarines, B-59, was forced to surface late at night in the Sargasso Sea to recharge its batteries and found itself surrounded by US destroyers and anti-submarine planes circling overhead.

In a newly translated account , one of the senior officers on board, Captain Second Class Vasily Arkhipov, described the scene.

“Overflights by planes just 20-30 metres above the submarine’s conning tower, use of powerful searchlights, fire from automatic cannons (over 300 shells), dropping depth charges, cutting in front of the submarine by destroyers at a dangerously [small] distance, targeting guns at the submarine,” Arkhipov, the chief of staff of the 69th submarine brigade, recalled.

In his account, first given in 1997 but published for the first time in English by the National Security Archive at George Washington University, the submarine’s commander, Valentin Savitsky, lost his nerve.

Arkhipov said one of the US planes “turned on powerful searchlights and blinded the people on the bridge so that their eyes hurt”.

“It was a shock,” he said. “The commander physically could not give any orders, could not even understand what was happening.”

The risk was, Arkhipov added: “The commander could have instinctively, without contemplation ordered an ‘emergency dive’; then after submerging, the question whether the plane was shooting at the submarine or around it would not have come up in anybody’s head. That is war.”

In his account, Arkhipov played down his role and how close the B-59 submarine commander, Savitsky, came to launching the submarine’s one nuclear-tipped torpedo. However, Svetlana Savranskaya, the director of the National Security Archive’s Russian programmes, interviewed another submarine commander from the same brigade, Ryurik Ketov, who said Savitsky was convinced they were under attack and that the war with the US had started.

The commander panicked, calling for an “urgent dive” and for the number one torpedo with the nuclear warhead to be prepared. However, because the signalling officer was in the way, Savitsky could not immediately get down the narrow stairway through the conning tower, and during those few moments of hesitation, Arkhipov realised that the US forces were signalling rather than attacking, and deliberately firing off to the side of the submarine.

“He called to Savitsky and said: ‘calm down, look they are signalling, not attacking, let’s signal back.’ Savitsky turned back, saw the situation, ordered the signalling officer to signal back,” Savranskaya said. She added that two other officers would have had to confirm any order from Savitsky before the nuclear torpedo could have been launched.

Tom Blanton, the director of the National Security Archive, said the aggressive tactics used by the American submarine hunters contributed to the close shave.

At a conference in Havana in 2002, John Peterson, a lieutenant on the USS Beale, the destroyer closest to the Russian submarine, said he and his crew resented their orders to use only practice depth charges, which just made a loud bang. So they stuffed hand grenades into toilet roll tubes which would hold the pin down for a couple of hundred metres before disintegrating, and causing the grenade to explode next to the submarine’s hull.

The Russian signals intelligence officer on the B-59, Vadim Orlov, said the experience was like being inside an oil drum beaten by a sledgehammer.

The officers and crew were already exhausted. They had sailed all the way from the Russian far north, in submarines that were not adapted for warm waters. Internal temperatures in the engine compartment rose to up to 65 degrees Celsius, with carbon dioxide levels several times normal, and there was very little drinking water, Arkhipov recalled.

Saved ‘primarily because of luck’

The B-59 incident was just one of a cascade of crises that day. A U-2 went missing over Siberia when the pilot lost his bearings, blinded by the aurora borealis and misled by compass malfunction close to the north pole.

Some F-102 interceptor jets were scrambled to protect the U-2, but the joint chiefs of staff who gave the order for their launch were not aware they had been armed with nuclear missiles as a matter of course once the alert level was raised to Defcon 2.

Minutes later, the joint chiefs heard that another U-2 had been shot down over Cuba and assumed it was a deliberate escalation by Moscow. In fact, the order had been given independently by two Soviet generals in Cuba. The joint chiefs were also unaware that there were 80 nuclear warheads on the missiles already in Cuba when they gave their recommendation for the US to carry out airstrikes and then an invasion of Cuba.

The recommendation was overruled by president John Kennedy, as negotiations with Soviet representatives, some of them in a Washington Chinese restaurant, were making progress, leading ultimately to the withdrawal of Soviet missiles from Cuba while US missiles were pulled back from Turkey.

Tom Collina, the director of policy at the Ploughshares Fund, a disarmament advocacy group, said Black Saturday “reminds us that the reason we’ve gotten out of things like that in the past is primarily because of luck”.

“We had some good management, we had some good thinkers,” Collina, co-author of The Button, a book on the nuclear arms race, said. “But basically, we got lucky in the closest situations where we could have gotten involved in nuclear war.”

In the incident over the Black Sea on 29 September this year, two Russian Su-27 fighter aircraft shadowed a Royal Air Force Rivet Joint electronic surveillance plane, and one of the Russian planes released a missile .

The Russian air force investigated and claimed it was the result of a technical malfunction. British officials are not convinced it was an accident, but intercepted communications made clear that Russian ground controllers were shocked at what happened, suggesting that if it was a deliberate show of force it was the decision of the pilot, rather than an order from Moscow.

The close encounter prompted an unscheduled visit to Washington on 18 October by the UK defence minister, Ben Wallace, to coordinate responses in the event of a miscalculation or accidental clash between Nato and Russian forces, and to ask for Washington’s agreement for the UK to restart Rivet Joint patrols with fighter escorts.

Collina said the danger of disaster would remain as long as nuclear weapons were part of the military equation.

“The lesson we should have learned in 1962 is that humans are fallible, and we should not combine crises with fallible humans with nuclear weapons,” Collina said. “Yet here we are again.”

- Nuclear weapons

Most viewed

- About WordPress

- Get Involved

- WordPress.org

- Documentation

- Learn WordPress

- Cuban Missile Crisis

Contextual Essay

Topic: How did the Cuban Missile Crisis affect the United States’ foreign policy in Cuba during the Cold War?

- Introduction

Despite the short geographical distance between the two countries, Cuba and the United States have had a complicated relationship for more than 150 years owing to a long list of historical events. Among all, the Cuban Missile Crisis is considered as one of the most dangerous moments in both the American and Cuban history as it was the first time that these two countries and the former Soviet Union came close to the outbreak of a nuclear war. While the Crisis revealed the possibility of a strong alliance formed by the former Soviet Union and Cuba, two communist countries, it also served as a reminder to U.S. leaders that their past strategy of imposing democratic ideology on Cuba might not work anymore and the U.S. needed a different approach. It was lucky that the U.S. was able to escape from a nuclear disaster in the end, how did the Cuban Missile Crisis affect the U.S. foreign policy in Cuba during the Cold War?

To answer my research question, I searched on different academic databases related to Latin American studies, history, and political science. JSTOR, Hispanic American Historical Review, and Journal of American History were examples of databases that I used. I also put in keywords like “Cuban Missile Crisis,” “Cuba and the U.S.,” and “U.S. cold war foreign policy” to find sources that are related to my research focus. Furthermore, I have included primary and secondary sources that address the foreign policies the U.S. implemented before and after the Cuban Missile Crisis. In order to provide a more comprehensive picture of the impact of the Crisis on the U.S. foreign policy in Cuba, the primary sources used would include declassified CIA documents, government memos, photos, and correspondence between leaders. These sources would be the best for my project because they provided persuading first-hand information for analyzing the issue. I cut sources that were not trustworthy and did not relate to my topic. This research topic was significant because it reflected the period when Cuban-U.S. relations became more negative. By understanding the change in foreign policy direction after the Cuban Missile Crisis, we could gain a better understanding of the development of Cuban-U.S. relations since the Cold War. On top of that, it was also a chance for us to reflect upon the decision-making process and learn from the past.

In my opinion, the Cuban Missile Crisis affected U.S. foreign policy in Cuba during the Cold War in three ways. First, the Crisis allowed the U.S. government to realize the importance of flexible and planned crisis management. Second, the Crisis reinforced the U.S. government’s belief in the Containment Policy. Third, the Crisis reminded the U.S. of the importance of multilateralism when it came to international affairs.

In October 1962, the United States detected that the former Soviet Union had deployed medium-range missiles in Cuba. This discovery then led to a tense standoff that lasted for 13 days, which was later known as the Cuban Missile Crisis. In response to the Soviet Union’s action, the Kennedy administration quickly placed a “quarantine” naval blockade around Cuba and demanded the destruction of missile sites. [1] This decision was made carefully by the U.S. government because any miscalculation would lead to a nuclear war between Cuba, the U.S.S.R. and the U.S. After weighing possible options, the former Soviet Union finally announced the removal of missiles for an American pledge not to reinvade Cuba. [2] On the other hand, the U.S. also agreed to secretly remove its nuclear missiles from Turkey in a separate deal. [3] The Crisis was then over and the three countries involved were able to escape from a detrimental nuclear crisis.

After World War II, the United States and the former Soviet Union began battling indirectly through a plethora of ways like propaganda, economic aid, and military coalitions. This was known as the period of the Cold War. [4] The Cuban Missile Crisis happened amid the Cold War then caused the escalation of tension between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. Despite the removal of nuclear missiles by the U.S.S.R., Moscow still decided to upgrade the Soviet nuclear strike force. This decision allowed the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. to further their nuclear arms race as a result. [5] The Cold War tensions only softened after the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty was negotiated and signed by both superpowers. [6] Additionally, both the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. reflected upon the dangerous nuclear crisis and established the “Hotline” to reduce the possibility of war by miscalculation. [7]

- Crisis management

To begin, the success of solving the Cuban Missile Crisis has proven to the U.S. the importance of planning and flexibility when it came to crisis management with a tight time limit. This was supported by the CIA document “Major Consequences of Certain U.S. Courses of Action on Cuba” and the Dillon group discussion paper “Scenario for Airstrike Against Offensive Missile Bases and Bombers in Cuba.” Rather than devoting to existing plans, the Kennedy administration came up with flexible plans. Depending on the potential reactions of Cuba towards different hypothetical scenarios of the United States’ response after the deployment of Soviet nuclear weapons in Cuba, the CIA document listed several modes of blockade and warnings that the U.S. could use to avoid a nuclear war. [8] The CIA document also presented the meanings of different military strategies to the U.S., the U.S.S.R., and Cuba.[9] In addition, the Dillon group discussion paper included the advantages and disadvantages of using airstrikes against Cuba.[10] Not only did these documents reveal the careful planning process that the U.S. government underwent under a pressurized time limit, but they also allowed the U.S. government to realize the uncertainty in the U.S.-Cuban relations and the U.S.-Soviet relations. The U.S. would need to have flexible military plans prepared to protect itself from a similar crisis and to sustain harmonious relationships with the U.S.S.R. and Cuba in the long run.

- Containment Policy

Furthermore, the Cuban Missile Crisis has allowed the U.S. government to reflect upon the extent of the application of the Containment Policy to prevent the spread of communism. Since the U.S. became a superpower after World War II, it seldom faced threat from countries that were close to its border. The Crisis then was an opportunity for the U.S. to learn that it was possible that itself could be trapped by the “containment policy” by other communist countries like the Soviet Union and Cuba. This could explain why the U.S. chose not to invade or attack Cuba but to compromise with the U.S.S.R. by trading nuclear missiles for those in Cuba, despite intended to actively suppress communism. [11]

As mentioned in the White House document, “two extreme views on the proper role of force in the international relations were wrong – the view which rejects force altogether as an instrument of foreign policy; and the view that force can solve everything,” the Crisis made the U.S. understand that forceful use of containment policy on communist countries might not work all the time. [12] The U.S. would need to change its focus and turn to other diplomatic strategies to better protect its national interest.

- Multilateralism

In addition, the success of solving the Cuban Missile Crisis allowed the United States to understand the importance of multilateralism when it came to international conflicts with communist countries. Amid the Crisis, the U.S. actively sought support from different countries. This was clearly noted in the CIA daily report “The Crisis USSR/Cuba” that many countries like Spain, France, and Venezuela showed public support for the U.S. quarantine blockade policy on Cuba.[13] On top of the support of other countries, the U.S. also sought justification of the quarantine through the Organization of American States and made good use of the United Nations to communicate with the Soviets on the size of the quarantine zone.[14] All these measures made it difficult for Moscow or Cuba to further escalate the Crisis or interpret American actions as a serious threat to their interests. With the clever use of multilateralism, the U.S. was able to minimize the danger of the Crisis smoothly before any escalation of tensions. This experience also served as a good resource for solving troubling diplomatic problems with Cuba or other communist countries in the future.

In conclusion, the Cuban Missile Crisis has several effects on the United States’ foreign policy in Cuba during the Cold War. To begin, the success of solving the Cuban Missile Crisis has proven to the U.S. the importance of planning and flexibility when it came to crisis management with a tight time limit. Additionally, the Cuban Missile Crisis has allowed the U.S. government to reflect upon the extent of the application of the Containment Policy to prevent the spread of communism. Furthermore, the Cuban Missile Crisis provided the United States a chance to understand the importance of multilateralism when it came to solving international conflicts with communist countries. By understanding more about the effects that the Cuban Missile Crisis had on U.S. foreign policy in Cuba, we were able to realize the vulnerability and insecurity in Cuban-U.S. relations. This allowed us to gain a more diverse view of the causes of the conflicting U.S.-Cuban relations in the 20th and 21st centuries.

- Primary Sources (10-15 sources)

CIA Special National Intelligence Estimate, “Major Consequences of Certain U.S. Courses of Action on Cuba,” October 20, 1962. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/19621020cia.pdf.

CIA daily report, “The Crisis USSR/Cuba,” October 27, 1962. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/621027%20The%20Crisis%20USSR-Cuba.pdf

Dillon group discussion paper, “Scenario for Airstrike Against Offensive Missile Bases and Bombers in Cuba,” October 25, 1962. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/19621025dillon.pdf

White House, “Post Mortem on Cuba,” October 29, 1962. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/19621029mortem.pdf

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. “Cuban Missile Crisis,” Accessed February 25, 2020. https://microsites.jfklibrary.org/cmc/ .

The U-2 Plane. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/19.jpg

October 5, 1962: CIA chart of “reconnaissance objectives in Cuba.”

Graphic from Military History Quarterly of the U.S. invasion plan, 1962.

CIA reference photograph of Soviet cruise missile in its air-launched configuration.

October 17, 1962: U-2 photograph of first IRBM site found under construction.

[1] “The Cold War,” JFK Library, accessed May 5, 2020, https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/the-cold-war .

[3] “Cuban Missile Crisis.” JFK Library. Accessed May 5, 2020. https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/cuban-missile-crisis.

[4] “The Cold War,” JFK Library, accessed May 5, 2020, https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/the-cold-war .

[8] CIA Special National Intelligence Estimate, “Major Consequences of Certain U.S. Courses of Action on Cuba,” October 20, 1962. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/19621020cia.pdf .

[10] Dillon group discussion paper, “Scenario for Airstrike Against Offensive Missile Bases and Bombers in Cuba,” October 25, 1962. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/19621025dillon.pdf

[11] CIA Special National Intelligence Estimate, “Major Consequences of Certain U.S. Courses of Action on Cuba,” October 20, 1962. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/19621020cia.pdf .

[12] White House, “Post Mortem on Cuba,” October 29, 1962. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/19621029mortem.pdf

[13] CIA daily report, “The Crisis USSR/Cuba,” October 27, 1962. https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/nsa/cuba_mis_cri/621027%20The%20Crisis%20USSR-Cuba.pd

[14] “TWE Remembers: The OAS Endorses a Quarantine of Cuba (Cuban Missile Crisis, Day Eight).” Council on Foreign Relations. Accessed May 4, 2020. https://www.cfr.org/blog/twe-remembers-oas-endorses-quarantine-cuba-cuban-missile-crisis-day-eight.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

I’ve Studied 13 Days of the Cuban Missile Crisis. This Is What I See When I Look at Putin.

By Michael Dobbs

Mr. Dobbs is a former foreign correspondent who covered the collapse of communism and the author of “One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War.”

Two nuclear-armed states on a collision course with no obvious exit ramp. An erratic Russian leader using apocalyptic language — “if you want us to all meet in hell, it’s up to you.” Showdowns at the United Nations, with each side accusing the other of essentially gambling with Armageddon.

For six decades, the Cuban missile crisis has been viewed as the defining confrontation of the modern age, the world’s closest brush with nuclear annihilation. The war in Ukraine presents perils of at least equal magnitude, particularly now that Vladimir Putin has backed himself into a corner by declaring large chunks of neighboring Ukraine as belonging to Russia “forever.”

As two countries proceed up an escalatory ladder, mistakes become increasingly likely — as the Cuban missile crisis made clear. In a conventional war, it is possible for political leaders to make significant mistakes and for the human race to survive, battered but intact. In a nuclear standoff, even a minor misunderstanding or miscommunication can have catastrophic consequences.

In October 1962, it was President John Kennedy who declared a naval blockade, or quarantine, of Cuba to prevent reinforcement of the Soviet military position on the island. This put the onus on his Kremlin counterpart, Nikita Khrushchev, to either accept the clearly signaled American condition for ending the crisis (a full withdrawal of Soviet missiles from Cuba) or risk nuclear war.

This time, the roles are reversed: Mr. Putin is seeking to enforce a red line by insisting he will use “ all available means ,” including his nuclear arsenal, to defend the newly, unilaterally expanded borders of Mother Russia. President Biden has promised to support Ukraine’s attempts to defend itself. It is unclear how Mr. Putin will react to his red line being ignored.

Even if we assume Mr. Putin is a rational actor who wishes to avoid nuclear annihilation, that is not necessarily reassuring. Contrary to popular belief, the biggest danger of nuclear war in October 1962 did not arise from the so-called eyeball-to-eyeball confrontation between Khrushchev and Kennedy but from their inability to control events that they themselves had set in motion.

As I discovered when I assembled a minute-by-minute chronology of the most dangerous phase of the crisis, there were times when both leaders were unaware of developments on the battlefield that assumed a logic and momentum of their own.

Khrushchev never authorized the shooting down of an American U-2 spy plane over Cuba by a Soviet missile on Oct. 27, 1962, the most dangerous day of the crisis. Kennedy was unaware that another U-2 strayed over Russian airspace the same day, triggering Soviet air defenses. “There’s always some sonofabitch that doesn’t get the word,” was how he put it later.

While the war in Ukraine is obviously different from the Cuban missile crisis, it is not hard to imagine comparable failures and miscalculations. A stray shell from either side could cause an accident at a nuclear power plant, spewing radioactive fallout over much of Europe. A bungled attempt by Russia to interdict Western military supplies to Ukraine could spill over into NATO countries like Poland, triggering an automatic U.S. response. A Russian decision to use tactical nuclear weapons against Ukrainian troop formations could escalate into a full-blown nuclear exchange with the United States.

While the U.S. intelligence community has chalked up some impressive successes in Ukraine, most notably its accurate prediction of Russia’s invasion, which occurred on Feb. 24, the 1962 crisis should serve as a reminder of the limits of intelligence gathering. Kennedy was belatedly informed about the deployment of medium-range Soviet missiles to Cuba, but was left in the dark about other equally important matters. He was unaware, for example, of the presence of nearly 100 Soviet tactical nuclear missiles in Cuba targeted on the Guantánamo naval base and a potential American invading force. The C.I.A. underestimated Soviet troop strength on the island and was unable to track the movement of any of the nuclear warheads.

What both Kennedy and Khrushchev did possess was an intuitive understanding of the peril confronting not just their own countries but the entire world if the crisis was allowed to escalate. That is why they maintained a back channel to communicate with each other privately (through the president’s brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, and the Soviet ambassador to Washington, Anatoly Dobrynin) even as they denounced each other publicly. It is also why they acted swiftly to reach a compromise deal (kept secret for decades) that involved the dismantling of U.S. medium-range missiles in Turkey in exchange for a Soviet nuclear withdrawal from Cuba.

Like Kennedy, Khrushchev had experienced the horror of World War II. He knew that nuclear war would be many times more destructive. Kremlin archives show that for all his bloodcurdling rhetoric, Khrushchev was determined to find a peaceful solution as soon as it became clear that his nuclear gamble had failed. Mr. Putin, by contrast, has chosen to raise the stakes at every critical point. Escalation has become his preferred tactic.

All this is taking place against the background of a communications revolution that has sped up the pace of warfare and diplomacy, resolving some of the technological challenges faced by Kennedy and Khrushchev but creating new ones in their place. It no longer takes 12 hours to transmit a coded telegram from Washington to Moscow. These days, news travels from the battlefield almost instantaneously, putting pressure on political leaders to make hasty decisions. A U.S. president no longer has the luxury that Kennedy enjoyed in October 1962 of taking six days to consider his response to the discovery of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba.

We have not begun to approach the nuclear alert levels that characterized the Cuban missile crisis. While Mr. Putin has talked about putting his nuclear forces on heightened alert , there appears to be no confirmation of unusual movements in that direction. The most dangerous phase of the Cuban missile crisis lasted just 13 days; we are already in the eighth month of the war in Ukraine, with no end in sight. The longer it drags on, the greater the threat of some terrible miscalculation.

Michael Dobbs is a former foreign correspondent who covered the collapse of communism and is the author of “One Minute to Midnight: Kennedy, Khrushchev and Castro on the Brink of Nuclear War.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram .

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Cuban missile crisis, major confrontation at the height of the Cold War that brought the United States and the Soviet Union to the brink of a shooting war in October 1962 over the presence of Soviet nuclear-armed missiles in Cuba. The crisis was a defining moment in the presidency of John F. Kennedy.

The origins of the Cuban Missile Crisis lie in the failed Bay of Pigs invasion, during which US-supported Cuban exiles hoping to foment an uprising against Castro were overpowered by the Cuban armed forces. ... Contingency plans were drawn up for a full-scale invasion of Cuba and a nuclear attack on the Soviet Union, in the event that the ...

The Cuban Missile crisis was a 13-day political and military standoff in October 1962 over Soviet missiles in Cuba. ... including a bombing attack on the missile sites and a full-scale invasion of ...

The Cuban missile crisis began for the United States on the morning of October 16, when President Kennedy was informed of the discovery of missile sites in Cuba by U-2 surveillance aircraft. Kennedy convened an informal group of cabinet officials and top civilian and military advisors (the Ex Comm) to consider and plan an appropriate response.

Stein, C. (2008). Cuban missile crisis: In the shadow of nuclear war. USA: Enslow Publishers, Inc. This essay, "The Cuban Missile Crisis: The Causes and Effects" is published exclusively on IvyPanda's free essay examples database. You can use it for research and reference purposes to write your own paper.

For thirteen days in October 1962 the world waited—seemingly on the brink of nuclear war—and hoped for a peaceful resolution to the Cuban Missile Crisis. In October 1962, an American U-2 spy plane secretly photographed nuclear missile sites being built by the Soviet Union on the island of Cuba. President Kennedy did not want the Soviet ...

Cuban Missile Crisis 1962. The Central Intelligence Agency is pleased to declassify and publish this collection of documents on the Cuban Missile Crisis, as the First Intelli gence History Symposium marks the thirtieth anniversary of that event. We hope that both the Symposium and this volume will help fill the large gaps in information ...

The Cuban Missile Crisis, also known as the October Crisis ( Spanish: Crisis de Octubre) in Cuba, or the Caribbean Crisis ( Russian: Карибский кризис, romanized :Karibskiy krizis ), was a 13-day confrontation between the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union, when American deployments of nuclear missiles in Italy ...

Castro, the Missile Crisis, and the Soviet Collapse (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littleton, 2002); and James A. Blight and David A. Welch, On the Brink: Americans and Soviets Reexamine the Cuban Missile Crisis (New York: Hill and Wang, 1989). in Moscow, Plokhy filled in some blank areas in the historical record.6

Cuban Missile Crisis. At the height of the Cold War, for two weeks in October 1962, the world teetered on the edge of thermonuclear war. Earlier that fall, the Soviet Union, under orders from Premier Nikita Khrushchev, began to secretly deploy a nuclear strike force in Cuba, just 90 miles from the United States.

Fifty years ago this month, world attention was fixed on a U.S.-Soviet confrontation over the placement of Soviet nuclear-armed missiles in Cuba, probably the most dangerous and perhaps the most studied moment of the Cold War. This iconic crisis has left us a legacy of lessons and insights for the future, many only recognized in recent years as ...

Legacies and Lessons. Twenty years ago this autumn, halfway through the 1962 foot-ball season, Americans learned from their President, John F. Kennedy, that Nikita Khrushchev had secretly placed nuclear missiles in Castro's Cuba and that an unprecedented U.S. show-down with Moscow was at hand.

Sixty years ago this week, the United States and the Soviet Union narrowly averted catastrophe over the installation of nuclear-armed Soviet missiles on Cuba, just 90 miles from U.S. shores ...

The Cuban Missile Crisis was the signature moment of John F. Kennedy's presidency. The most dramatic parts of that crisis—the famed "13 days"—lasted from October 16, 1962, when President Kennedy first learned that the Soviet Union was constructing missile launch sites in Cuba, to October 28, when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev publicly ...

The Cuban Missile Crisis deepened diplomatic relations between the United States and Soviet Union with a choice of evading more emergency or perhaps war. According to Byrne (2006, p.125), Kennedy himself was skillful and embraced compulsion to gain a diplomatic success. He sustained emphasis upon Khrushchev vehemently but adeptly.

A Soviet R12 medium range ballistic missile deployed during the Cuban missile crisis of 1962. Newly translated accounts show how a Russian B-59 submarine commander came close to launching a ...

In my opinion, the Cuban Missile Crisis affected U.S. foreign policy in Cuba during the Cold War in three ways. First, the Crisis allowed the U.S. government to realize the importance of flexible and planned crisis management. Second, the Crisis reinforced the U.S. government's belief in the Containment Policy.