- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Advertising →

- 20 Jun 2023

- Cold Call Podcast

Elon Musk’s Twitter Takeover: Lessons in Strategic Change

In late October 2022, Elon Musk officially took Twitter private and became the company’s majority shareholder, finally ending a months-long acquisition saga. He appointed himself CEO and brought in his own team to clean house. Musk needed to take decisive steps to succeed against the major opposition to his leadership from both inside and outside the company. Twitter employees circulated an open letter protesting expected layoffs, advertising agencies advised their clients to pause spending on Twitter, and EU officials considered a broader Twitter ban. What short-term actions should Musk take to stabilize the situation, and how should he approach long-term strategy to turn around Twitter? Harvard Business School assistant professor Andy Wu and co-author Goran Calic, associate professor at McMaster University’s DeGroote School of Business, discuss Twitter as a microcosm for the future of media and information in their case, “Twitter Turnaround and Elon Musk.”

- 06 Jan 2021

- Working Paper Summaries

Aggregate Advertising Expenditure in the US Economy: What's Up? Is It Real?

We analyze total United States advertising spending from 1960 to 2018. In nominal terms, the elasticity of annual advertising outlays with respect to gross domestic product appears to have increased substantially beginning in the late 1990s, roughly coinciding with the dramatic growth of internet-based advertising.

- 15 Sep 2020

Time and the Value of Data

This paper studies the impact of time-dependency and data perishability on a dataset's effectiveness in creating value for a business, and shows the value of data in the search engine and advertisement businesses perishes quickly.

- 19 May 2020

- Research & Ideas

Why Privacy Protection Notices Turn Off Shoppers

It seems counterintuitive, but website privacy protection notices appear to discourage shoppers from buying, according to Leslie John. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 02 Mar 2020

- What Do You Think?

Are Candor, Humility, and Trust Making a Comeback?

SUMMING UP: Have core leadership values been declining in recent years? If so, how do we get them back? James Heskett's readers provide answers. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 06 Aug 2019

Super Bowl Ads Sell Products, but Do They Sell Brands?

Super Bowl advertising is increasingly about using storytelling to sell corporate brands rather than products. Shelle Santana discusses why stories win (or fumble) on game day. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 27 Jul 2019

Does Facebook's Business Model Threaten Our Elections?

America's 2016 presidential election was the target of voter manipulation via social media, particularly on Facebook. George Riedel thinks history is about to repeat itself. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 10 Oct 2018

The Legacy of Boaty McBoatface: Beware of Customers Who Vote

Companies that encourage consumers to vote online should be forewarned—they may expect more than you promise, according to research by Michael Norton, Leslie John, and colleagues. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 27 Sep 2018

Large-Scale Demand Estimation with Search Data

Online retailers face the challenge of leveraging the rich data they collect on their websites to uncover insights about consumer behavior. This study proposes a practical and tractable model of economic behavior that can reveal helpful patterns of cross-product substitution. The model can be used to simulate optimal prices.

- 18 Jun 2018

Warning: Scary Warning Labels Work!

If you want to convince consumers to stay away from unhealthy diet choices, don't be subtle about possible consequences, says Leslie John. These graphically graphic warning labels seem to do the trick. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 18 Sep 2017

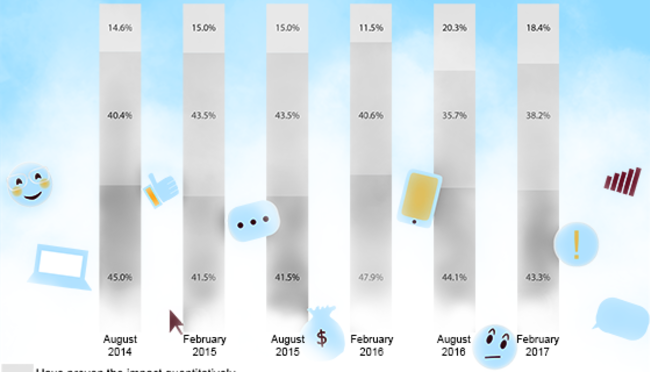

'Likes' Lead to Nothing—and Other Hard-Learned Lessons of Social Media Marketing

A decade-and-a-half after the dawn of social media marketing, brands are still learning what works and what doesn't with consumers. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 26 Jul 2017

The Revolution in Advertising: From Don Draper to Big Data

The Mad Men of advertising are being replaced by data scientists and analysts. In this podcast, marketing professor John Deighton and advertising legend Sir Martin Sorrell discuss the positives and negatives of digital marketing. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 13 Mar 2017

Hiding Products From Customers May Ultimately Boost Sales

Is it smart for retailers to display their wares to customers a few at a time or all at once? The answer depends largely on the product category, according to research by Kris Johnson Ferreira and Joel Goh. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 06 Mar 2017

Why Comparing Apples to Apples Online Leads To More Fruitful Sales

The items displayed next to a product in online marketing displays may determine whether customers buy that product, according to a new study by Uma R. Karmarkar. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 13 Feb 2017

Paid Search Ads Pay Off for Lesser-Known Restaurants

Researchers Michael Luca and Weijia Dai wanted to know if paid search ads pay off for small businesses such as restaurants. The answer: Yes, but not for long. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 08 Dec 2016

How Wayfair Built a Furniture Brand from Scratch

What was once a collection of 240 home furnishing sites is now a single, successful brand, Wayfair.com. How that brand developed over time and the challenges and opportunities presented by search engine marketing are discussed by Thales Teixeira. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 04 May 2016

What Does Boaty McBoatface Tell Us About Brand Control on the Internet?

SUMMING UP. Boaty McBoatface may have been shot down as the social-media sourced name of a research vessel, but James Heskett's readers are up to their hip-boots in opinions on the matter. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 02 May 2016

Why People Don’t Vote--and How a Good Ground Game Helps

Recent research by Vincent Pons shows that campaigners knocking on the doors of potential voters not only improves overall turnout but helps individual candidates win more of those votes. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 21 Mar 2016

Can Customer Reviews Be 'Managed?'

Consumers increasingly rely on peer reviews on TripAdvisor and other sites to make purchase decisions, so it makes sense that companies have a stake in wanting to shape those opinions. But can they? Thales Teixeira says a good product trumps all. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 28 Oct 2015

A Dedication to Creation: India's Ad Man Ranjan Kapur

How do you build a brand amid the uncertainties and opportunities of a developing market? Harvard Business School Professor Sunil Gupta shares lessons learned from Ranjan Kapur, an iconic figure in the Indian advertising industry. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

2021 Theses Doctoral

Essays on Digital Advertising

Gritckevich, Aleksandr

Digital advertising has seen dramatic growth over the last decade. Total digital ad spending in the US has increased 6 times between 2010 and 2020, from $26 billion to $152 billion(eMarketer). This impressive development has in turn sparked a huge stream of literature studying all the different aspects of advertising in the digital media. My dissertation contributes to this literature via two essays. In the first essay, I consider a very important topic of ad blocking, that in the recent years has become a significant threat to advertising supported content. With a specific focus on consumer and total welfare, I show the detrimental role of the adblockers’ current revenue model in decreasing content quality, consumer surplus and total welfare. In the second essay, I study demand learning in digital advertising markets, where firms learn over time how their advertising campaigns impact consumer demand by using their advertising campaign outcomes in earlier periods. By developing an analytic model, I demonstrate in several scenarios, such as monopoly and competition, that learning has an ambiguous effect on the key market parameters and, in particular, on the equilibrium advertising and quantities.

Geographic Areas

- United States

- Internet advertising

- Internet marketing

- Consumption (Economics)

More About This Work

- DOI Copy DOI to clipboard

Research in marketing strategy

- Review Paper

- Published: 18 August 2018

- Volume 47 , pages 4–29, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Neil A. Morgan 1 ,

- Kimberly A. Whitler 2 ,

- Hui Feng 3 &

- Simos Chari 4

42k Accesses

123 Citations

32 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

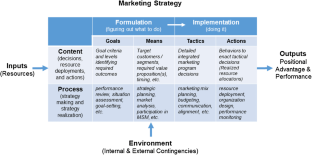

Marketing strategy is a construct that lies at the conceptual heart of the field of strategic marketing and is central to the practice of marketing. It is also the area within which many of the most pressing current challenges identified by marketers and CMOs arise. We develop a new conceptualization of the domain and sub-domains of marketing strategy and use this lens to assess the current state of marketing strategy research by examining the papers in the six most influential marketing journals over the period 1999 through 2017. We uncover important challenges to marketing strategy research—not least the increasingly limited number and focus of studies, and the declining use of both theory and primary research designs. However, we also uncover numerous opportunities for developing important and highly relevant new marketing strategy knowledge—the number and importance of unanswered marketing strategy questions and opportunities to impact practice has arguably never been greater. To guide such research, we develop a new research agenda that provides opportunities for researchers to develop new theory, establish clear relevance, and contribute to improving practice.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Social media marketing strategy: definition, conceptualization, taxonomy, validation, and future agenda

Fangfang Li, Jorma Larimo & Leonidas C. Leonidou

Online influencer marketing

Fine F. Leung, Flora F. Gu & Robert W. Palmatier

How digital technologies reshape marketing: evidence from a qualitative investigation

Federica Pascucci, Elisabetta Savelli & Giacomo Gistri

We follow Varadarjan’s (2010) distinction, using “strategic marketing” as the term describing the general field of study and “marketing strategy” as the construct that is central in the field of strategic marketing—just as analogically “strategic management” is a field of study in which “corporate strategy” is a central construct.

Following the strategic management literature (e.g., Mintzberg 1994 ; Pascale 1984 ), marketing strategy has also been viewed from an “emergent” strategy perspective (e.g. Hutt et al. 1988 ; Menon et al. 1999 ). Conceptually this is captured as realized (but not pre-planned) tactics and actions in Figure 1 .

These may be at the product/brand, SBU, or firm level.

These strategic marketing but “non-strategy” coding areas are not mutually exclusive. For example, many papers in this non-strategy category cover both inputs/outputs and environment (e.g., Kumar et al. 2016 ; Lee et al. 2014 ; Palmatier et al. 2013 ; Zhou et al. 2005 ), or specific tactics, input/output, and environment (e.g., Bharadwaj et al. 2011 ; Palmatier et al. 2007 ; Rubera and Kirca 2012 ).

The relative drop in marketing strategy studies published in JM may be a function of the recent growth of interest in the shareholder perspective (Katsikeas et al. 2016 ) and studies linking marketing-related resources and capabilities directly with stock market performance indicators. Such studies typically treat marketing strategy as an unobserved intervening construct.

Since this concerns integrated marketing program design and execution, marketing mix studies contribute to knowledge of strategy implementation–content when all four major marketing program areas are either directly modeled or are controlled for in studies focusing on one or more specific marketing program components.

Alden, D. L., Steenkamp, J. B. E., & Batra, R. (1999). Brand positioning through advertising in Asia, North America, and Europe: The role of global consumer culture. Journal of Marketing, 63 (1), 75–87.

Article Google Scholar

Ataman, M. B., Van Heerde, H. J., & Mela, C. F. (2010). The long-term effect of marketing strategy on brand sales. Journal of Marketing Research, 47 (5), 866–882.

Atuahene-Gima, K., & Murray, J. Y. (2004). Antecedents and outcomes of marketing strategy comprehensiveness. Journal of Marketing, 68 (4), 33–46.

Balducci, B., & Marinova, D. (2018). Unstructured data in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (4), 557–590.

Baumgartner, H., & Pieters, R. (2003). The structural influence of marketing journals: A citation analysis of the discipline and its subareas over time. Journal of Marketing, 67 (2), 123–139.

Bharadwaj, S. G., Tuli, K. R., & Bonfrer, A. (2011). The impact of brand quality on shareholder wealth. Journal of Marketing, 75 (5), 88–104.

Bolton, R. N., Lemon, K. N., & Verhoef, P. C. (2004). The theoretical underpinnings of customer asset management: A framework and propositions for future research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32 (3), 271–292.

Bruce, N. I., Foutz, N. Z., & Kolsarici, C. (2012). Dynamic effectiveness of advertising and word of mouth in sequential distribution of new products. Journal of Marketing Research, 49 (4), 469–486.

Cespedes, F. V. (1991). Organizing and implementing the marketing effort: Text and cases . Boston: Addison-Wesley.

Google Scholar

Chandy, R. K., & Tellis, G. J. (2000). The incumbent’s curse? Incumbency, size, and radical product innovation. Journal of Marketing, 64 (3), 1–17.

Choi, S. C., & Coughlan, A. T. (2006). Private label positioning: Quality versus feature differentiation from the national brand. Journal of Retailing, 82 (2), 79–93.

Dickson, P. R., Farris, P. W., & Verbeke, W. J. (2001). Dynamic strategic thinking. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 29 (3), 216–237.

Esper, T. L., Ellinger, A. E., Stank, T. P., Flint, D. J., & Moon, M. (2010). Demand and supply integration: A conceptual framework of value creation through knowledge management. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 38 (1), 5–18.

Fang, E. E., Lee, J., Palmatier, R., & Han, S. (2016). If it takes a village to Foster innovation, success depends on the neighbors: The effects of global and Ego networks on new product launches. Journal of Marketing Research, 53 (3), 319–337.

Farjoun, M. (2002). Towards an organic perspective on strategy. Strategic Management Journal, 23 (7), 561–594.

Feldman, M. S., & Orlikowski, W. J. (2011). Theorizing practice and practicing theory. Organization Science, 22 (5), 1240–1253.

Frambach, R. T., Prabhu, J., & Verhallen, T. M. (2003). The influence of business strategy on new product activity: The role of market orientation. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 20 (4), 377–397.

Frankwick, G. L., Ward, J. C., Hutt, M. D., & Reingen, P. H. (1994). Evolving patterns of organizational beliefs in the formation of strategy. Journal of Marketing, 58 (2), 96–110.

Ghosh, M., & John, G. (1999). Governance value analysis and marketing strategy. Journal of Marketing, 63 (4), 131–145.

Gonzalez, G. R., Claro, D. P., & Palmatier, R. W. (2014). Synergistic effects of relationship Managers' social networks on sales performance. Journal of Marketing, 78 (1), 76–94.

Gooner, R. A., Morgan, N. A., & Perreault Jr., W. D. (2011). Is retail category management worth the effort (and does a category captain help or hinder). Journal of Marketing, 75 (5), 18–33.

Grewal, R., Chandrashekaran, M., Johnson, J. L., & Mallapragada, G. (2013). Environments, unobserved heterogeneity, and the effect of market orientation on outcomes for high-tech firms. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41 (2), 206–233.

Harmeling, C. M., Palmatier, R. W., Houston, M. B., Arnold, M. J., & Samaha, S. A. (2015). Transformational relationship events. Journal of Marketing, 79 (5), 39–62.

Hauser, J. R., & Shugan, S. M. (2008). Defensive marketing strategies. Marketing Science, 27 (1), 88–110.

Homburg, C., Workman Jr., J. P., & Jensen, O. (2000). Fundamental changes in marketing organization: The movement toward a customer-focused organizational structure. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28 (4), 459–478.

Homburg, C., Müller, M., & Klarmann, M. (2011). When should the customer really be king? On the optimum level of salesperson customer orientation in sales encounters. Journal of Marketing, 75 (2), 55–74.

Homburg, C., Artz, M., & Wieseke, J. (2012). Marketing performance measurement systems: Does comprehensiveness really improve performance? Journal of Marketing, 76 (3), 56–77.

Hutt, M. D., Reingen, P. H., & Ronchetto Jr., J. R. (1988). Tracing emergent processes in marketing strategy formation. Journal of Marketing, 52 (1), 4–19.

Katsikeas, C. S., Morgan, N. A., Leonidou, L. C., & Hult, G. T. M. (2016). Assessing performance outcomes in marketing. Journal of Marketing, 80 (2), 1–20.

Kerin, R. A., Mahajan, V., & Varadarajan, P. (1990). Contemporary perspectives on strategic market planning . Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Krush, M. T., Sohi, R. S., & Saini, A. (2015). Dispersion of marketing capabilities: Impact on marketing’s influence and business unit outcomes. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43 (1), 32–51.

Kumar, V., Dixit, A., Javalgi, R. R. G., & Dass, M. (2016). Research framework, strategies, and applications of intelligent agent technologies (IATs) in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44 (1), 24–45.

Kumar, V., Sharma, A., & Gupta, S. (2017). Accessing the influence of strategic marketing research on generating impact: Moderating roles of models, journals, and estimation approaches. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (2), 164–185.

Kyriakopoulos, K., & Moorman, C. (2004). Tradeoffs in marketing exploitation and exploration strategies: The overlooked role of market orientation. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 21 (3), 219–240.

Lee, J. Y., Sridhar, S., Henderson, C. M., & Palmatier, R. W. (2014). Effect of customer-centric structure on long-term financial performance. Marketing Science, 34 (2), 250–268.

Lewis, M. (2004). The influence of loyalty programs and short-term promotions on customer retention. Journal of Marketing Research, 41 (3), 281–292.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis . Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Luo, X., & Homburg, C. (2008). Satisfaction, complaint, and the stock value gap. Journal of Marketing, 72 (4), 29–43.

Maltz, E., & Kohli, A. K. (2000). Reducing marketing’s conflict with other functions: The differential effects of integrating mechanisms. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28 (4), 479.

Menon, A., Bharadwaj, S. G., Adidam, P. T., & Edison, S. W. (1999). Antecedents and consequences of marketing strategy making: A model and a test. Journal of Marketing, 63 (2), 18–40.

Mintzberg, H. (1994). The fall and rise of strategic planning. Harvard Business Review, 72 (1), 107–114.

Mintzberg, H., & Lampel, J. (1999). Reflecting on the strategy process. Sloan Management Review, 40 (3), 21.

Mizik, N., & Jacobson, R. (2003). Trading off between value creation and value appropriation: The financial implications of shifts in strategic emphasis. Journal of Marketing, 67 (1), 63–76.

Montgomery, D. B., Moore, M. C., & Urbany, J. E. (2005). Reasoning about competitive reactions: Evidence from executives. Marketing Science, 24 (1), 138–149.

Moorman, C., & Miner, A. S. (1998). The convergence of planning and execution: Improvisation in new product development. Journal of Marketing, 62 (3), 1–20.

Morgan, N. A. (2012). Marketing and business performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40 (1), 102–119.

Morgan, N. A., & Rego, L. L. (2006). The value of different customer satisfaction and loyalty metrics in predicting business performance. Marketing Science, 25 (5), 426–439.

Morgan, N. A., Katsikeas, C. S., & Vorhies, D. W. (2012). Export marketing strategy implementation, export marketing capabilities, and export venture performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40 (2), 271–289.

Noble, C. H., & Mokwa, M. P. (1999). Implementing marketing strategies: Developing and testing a managerial theory. Journal of Marketing, 63 (4), 57–73.

O'Sullivan, D., & Abela, A. V. (2007). Marketing performance measurement ability and firm performance. Journal of Marketing, 71 (2), 79–93.

Palmatier, R. W., Dant, R. P., & Grewal, D. (2007). A comparative longitudinal analysis of theoretical perspectives of interorganizational relationship performance. Journal of Marketing, 71 (4), 172–194.

Palmatier, R. W., Houston, M. B., Dant, R. P., & Grewal, D. (2013). Relationship velocity: Toward a theory of relationship dynamics. Journal of Marketing, 77 (1), 13–30.

Palmatier, R. W., Houston, M. B., & Hulland, J. (2018). Review articles: Purpose, process, and structure. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (1), 1–5.

Pascale, R. T. (1984). Perspectives on strategy: The real story behind Honda’s success. California Management Reviews, 26 (3), 47–72.

Payne, A., & Frow, P. (2005). A strategic framework for customer relationship management. Journal of Marketing, 69 (4), 167–176.

Petersen, J. A., & Kumar, V. (2015). Perceived risk, product returns, and optimal resource allocation: Evidence from a field experiment. Journal of Marketing Research, 52 (2), 268–285.

Piercy, N. F. (1998). Marketing implementation: The implications of marketing paradigm weakness for the strategy execution process. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 26 (3), 222–236.

Rego, L. L., Billett, M. T., & Morgan, N. A. (2009). Consumer-based brand equity and firm risk. Journal of Marketing, 73 (6), 47–60.

Rego, L. L., Morgan, N. A., & Fornell, C. (2013). Reexamining the market share–customer satisfaction relationship. Journal of Marketing, 77 (5), 1–20.

Roberts, J. H., Kayande, U., & Stremersch, S. (2014). From academic research to marketing practice: Exploring the marketing science value chain. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 31 (2), 127–140.

Rubera, G., & Kirca, A. H. (2012). Firm innovativeness and its performance outcomes: A meta-analytic review and theoretical integration. Journal of Marketing, 76 (3), 130–147.

Samaha, S. A., Palmatier, R. W., & Dant, R. P. (2011). Poisoning relationships: Perceived unfairness in channels of distribution. Journal of Marketing, 75 (3), 99–117.

Samaha, S. A., Beck, J. T., & Palmatier, R. W. (2014). The role of culture in international relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 78 (5), 78–98.

Slater, S. F., & Olson, E. M. (2001). Marketing's contribution to the implementation of business strategy: An empirical analysis. Strategic Management Journal, 22 (11), 1055–1067.

Slater, S. F., Hult, G. T. M., & Olson, E. M. (2007). On the importance of matching strategic behavior and target market selection to business strategy in high-tech markets. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35 (1), 5–17.

Slater, S. F., Hult, G. T. M., & Olson, E. M. (2010). Factors influencing the relative importance of marketing strategy creativity and marketing strategy implementation effectiveness. Industrial Marketing Management, 39 (4), 551–559.

Slotegraaf, R. J., & Atuahene-Gima, K. (2011). Product development team stability and new product advantage: The role of decision-making processes. Journal of Marketing, 75 (1), 96–108.

Song, M., Di Benedetto, C. A., & Zhao, Y. (2008). The antecedents and consequences of manufacturer–distributor cooperation: An empirical test in the US and Japan. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36 (2), 215–233.

Spyropoulou, S., Katsikeas, C. S., Skarmeas, D., & Morgan, N. A. (2018). Strategic goal accomplishment in export ventures: the role of capabilities, knowledge, and environment. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 46 (1), 109–129.

Steiner, M., Eggert, A., Ulaga, W., & Backhaus, K. (2016). Do customized service packages impede value capture in industrial markets? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44 (2), 151–165.

Sun, B., & Li, S. (2011). Learning and acting on customer information: A simulation-based demonstration on service allocations with offshore centers. Journal of Marketing Research, 48 (1), 72–86.

Van de Ven, A. H. (1992). Suggestions for studying strategy process: A research note. Strategic Management Journal, 13 (5), 169–188.

Varadarajan, R. (2010). Strategic marketing and marketing strategy: Domain, definition, fundamental issues and foundational premises. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 38 (2), 119–140.

Varadarajan, P. R., & Jayachandran, S. (1999). Marketing strategy: An assessment of the state of the field and outlook. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27 (2), 120–143.

Varadarajan, R., Yadav, M. S., & Shankar, V. (2008). First-mover advantage in an internet-enabled market environment: Conceptual framework and propositions. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36 (3), 293–308.

Venkatesan, R., & Kumar, V. (2004). A customer lifetime value framework for customer selection and resource allocation strategy. Journal of Marketing, 68 (4), 106–125.

Vorhies, D. W., & Morgan, N. A. (2003). A configuration theory assessment of marketing organization fit with business strategy and its relationship with marketing performance. Journal of Marketing, 67 (1), 100–115.

Walker Jr., O. C., & Ruekert, R. W. (1987). Marketing's role in the implementation of business strategies: A critical review and conceptual framework. Journal of Marketing, 51 (3), 15–33.

Whitler, K. A., & Morgan, N. (2017). Why CMOs never last and what to do about it. Harvard Business Review, 95 (4), 46–54.

Whittington, R. (2006). Completing the practice turn in strategy research. Organization Studies, 27 (5), 613–634.

Yadav, M. S. (2010). The decline of conceptual articles and implications for knowledge development. Journal of Marketing, 74 (1), 1–19.

Zhou, K. Z., Yim, C. K., & Tse, D. K. (2005). The effects of strategic orientations on technology-and market-based breakthrough innovations. Journal of Marketing, 69 (2), 42–60.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Kelley School of Business, Indiana University, 1309 E. Tenth St., Bloomington, IN, 47405-1701, USA

Neil A. Morgan

Darden School of Business, University of Virginia, 100 Darden Boulevard, Charlottesville, VA, 22903, USA

Kimberly A. Whitler

Ivy College of Business, Iowa State University, 3337 Gerdin Business Building, Ames, IA, 50011-1350, USA

Alliance Manchester Business School, University of Manchester, Booth Street West, Manchester, M15 6PB, UK

Simos Chari

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Neil A. Morgan .

Additional information

Mark Houston served as Area Editor for this article.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Morgan, N.A., Whitler, K.A., Feng, H. et al. Research in marketing strategy. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. 47 , 4–29 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-018-0598-1

Download citation

Received : 14 January 2018

Accepted : 20 July 2018

Published : 18 August 2018

Issue Date : 15 January 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-018-0598-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Marketing strategy

- Strategic marketing

- CMO marketing challenges

- Research design

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Company History

- Executive Team

- Banking, Finance, and Insurance

- Business-to-Business

- Consumer Packaged Goods (FMCG)

- Governmental Agencies

- Home Improvement & Trade Research

- Pharma, Medical, Health, and Wellness

- Restaurants

- Social Responsibility/Social Causes

- Technology Sector

- Client List

- Quality Assurance

- Data Security

- Advertising Testing Systems

- Advertising Tracking Research

- Awareness Trial Usage (ATUs)

- Brand Equity Monitoring

- Category Management

- Education Survey Research

- Economic Development Research

- Concept Testing

- Customer Loyalty Simulator

- Mail Surveys

- Data Entry Services

- Multilingual Coding

- Cross-Tabulation Services

- Employee Satisfaction Research

- Employee Retention

- Global Research

- American Home Comfort Study

- Economic Index

- Marketing Strategy

- Brand Name Research

- DecisionSystems

- Technology Forecasting

- Global Internet Panels

- Online Communities

- Panel Management

- Private Online Research Panels

- ESOMAR 28 Questions

- Simulated Shopping with Shelf Sets

- Custom/Ad Hoc Packaging Research

- Optima Product Testing

- Custom Product Testing

- Product Quality Monitoring

- Sensory Research Systems

- Promotion Testing

- Shopping Research

- Strategy Research

- Tracking Research

- Win-Loss Research

- Meet Our Moderators

- Digital Ethnography

- In the Moment Research

- Large-Scale Qualitative

- Online Qualitative

- Qualitative Research (Focus Groups)

- Unconventional Qualitative Methods

- Qualitative Research Library

- Analytical Consulting

- Choice Modeling Techniques

- Conceptor Volumetric Forecasting

- Demand Forecasting

- Economic Feasibility Analysis

- Economic Impact Analysis

- Econometric Modeling

- Marketing Science

- Marketing Mix Modeling

- Market Segmentation Methods

- Operations Research

- Predictive Analytics & Marketing Research

- Text Mining

- Pricing Research

- Sales Forecasting and Sales Modeling

- Acquisition Reviews

- Asset Optimization

- GIS mapping

- Location Analysis

- Shopping Center Repositioning

- The Imaginators®

- Relevant Innovation

- Brand Explorations

- Jerry W. Thomas Blogs

- Audrey Guinn Blogs

- Bonnie Janzen Blogs

- Clay Dethloff Blogs

- Elizabeth Horn Blogs

- Felicia Rogers Blogs

- Heather Kluter Blogs

- Jennifer Murphy Blogs

- John Colias Blogs

- Julie Trujillo Blogs

- Lesley Johnson Blogs

- Tom Allen Blogs

- Blog Archives 2017-2021

Case Histories

- Download Our Complimentary Report

- Economic Index Background

- Email Newsletter

- Free Software

- Videos - General Marketing Research

- Videos - Leadership Strategy Interviews

- Videos - Market Segmentation

- Videos - Media Mix Minute

- Videos - Strategy Series

- Webinars - Insider Series

White Papers

- Research Advice

Advertising Research by Jerry W. Thomas

A growing share of consumer-goods media spending is shifting away from traditional advertising media (television, radio, print, and outdoor).

Traditional media vs. new media.

Traditional media are also suffering from a long-term trend toward promotional expenditures which consume a larger share of the marketing budget. Many consumer-goods companies are spending less on advertising in total, as their executives strive to please Wall Street with improved short-term profits. The hope that one’s ads might “go viral” and accomplish advertising miracles on a low budget adds to the upheaval and distracts executives from the hard work of building effective advertising campaigns.

This decline of traditional media advertising in many consumer-goods companies is creating an opportunity for companies that appreciate the power of traditional advertising.

Social media, online, search, and mobile advertising all grab the headlines and attract marketing executives like moths to a flame, but we should not be dazzled or awed by the new media. They have their advantages and can be a part of the media mix, but they are probably still a distant “second fiddle” to traditional media. Indeed, we would argue that mastery of traditional media—especially television, radio, and outdoor advertising—is a far wiser strategy than aggressive pursuit of new media.

Media Choices

Strategic investment in media advertising is a key factor in corporate success. Think of media advertising as the long-range artillery of marketing; your goal is long-term bombardment to take possession of the consumer’s awareness and perceptions. A brand might have to take financial losses for a year or two while it builds awareness, tells its story, and crafts a brand image. This is the price of marketing success. Where to place strategic media spending is a daunting task in a world of infinite media choices. Here are some guidelines to help you think through the best options.

Television Advertising

Not only does the term “television advertising” refer to a commercial with color, motion, and sound (like those you see on television), it also refers to those same types of “commercials” you might see on a website, on various social media platforms, on YouTube, or on Facebook.

Thusly defined, television advertising is still the gold standard and the most effective of all media for consumer products. Television commercials have the greatest impact and tend to move awareness numbers up swiftly—with sufficient media weight. Generally, the equivalent of 100 GRPs (Gross Rating Points) per week is the lower limit of spending if you hope to see measurable increases in advertising awareness. Also, television commercials (like all advertising) will be more effective if a higher share are tested among consumers before airing.

Radio Advertising

Radio commercials can be as effective as television commercials, based on sales return per dollar spent on media. However, radio commercials seldom achieve their true potential because they tend to be inferior to television commercials in content and production quality. Typically, radio production budgets are much less than television budgets, and radio commercials are rarely tested among consumers. If you plan to use radio, pretest the commercials to make sure they work.

Print Advertising

Print advertising tends to work more slowly than television or radio. Therefore, an especially long period of time (or an especially heavy media schedule) is required to fully evaluate the total effects of print advertising. Print is an important arrow in the media quiver, however, because a share of the population tends to be heavy readers. You won’t reach this demographic with television, radio commercials, YouTube, or sponsorships of tractor races.

Outdoor Advertising

Outdoor advertising (also called out-of-home, or OOH) is especially effective as an advertising medium, if used properly. First, the message must be (a) on strategy, and (b) expressed in few words (the fewer words, the better). Second, traditional outdoor advertising (i.e., a static print ad, in effect) is more effective, in most instances, than the digital or electronic billboards, where a series of ads are shown briefly (changing ads every 8 seconds or so).

Outdoor advertising is great at extending or reinforcing the key theme of a television or radio campaign. If some of the visual elements and the key themes of a television campaign can be condensed and shown via outdoor advertising, the awareness-build of television can be accelerated. Outdoor advertising can also add a visual element to a radio campaign (e.g., show the retail package), and it can help boost the awareness-build of a print-advertising campaign.

Social Media Advertising

Social media continues to grow in importance and reach; its ultimate value as an advertising media remains to be seen. Ads and commercials intended for online delivery or social media distribution operate by the same rules as all other advertising. Television-testing techniques, for example, can be applied to commercials that look like television commercials, regardless of where those commercials are aired. Static banner ads are similar to print ads and can be evaluated by those metrics. What’s important is that social media ads go through the same research processes as other commercials do.

Advertising is primarily a strategic weapon, as previously noted. It’s the heavy, long-range artillery. Its total effects must be evaluated in the context of years, not weeks or months. Advertising cannot compete with sales-promotion and direct-marketing activities in generating short-term sales effects. But in the long term, the cumulative force of strategically sound media advertising can achieve results that cannot be equaled by sales promotion or other marketing activities.

Advertising Effectiveness

Advertising for new products tends to be more effective than advertising for established products (it’s the “news value” of the new product). In other words, it’s easier to create effective advertising for new products than it is for established products.

Given the greater effectiveness of new-product advertising, one of the most common marketing mistakes is failure to take advantage of this inherent benefit (i.e., the failure to fully exploit the new product advertising advantage).

Perhaps up to half of all advertising for established products is not effective, or is only minimally effective, based on Decision Analyst’s research. It could be said that no other industry has a failure rate as high as that of the advertising industry (with the possible exception of the promotion industries, direct-marketing industries, telemarketing industries, and other alternatives to traditional advertising).

The persistently high advertising failure rate results primarily from the lack of an accurate feedback mechanism—a lack of testing and evaluation. If an advertising agency doesn’t know when its advertising is bad or why it’s bad, how can the agency possibly improve its advertising? Marketing research can provide this feedback, but it’s often too expensive for the typical advertisement or commercial budget.

Among commercials that are effective, the degree of sales effectiveness can vary greatly from one commercial to the next. One commercial might be several times more effective than another. This indicates that the quality of advertising tends to be more important than the quantity of advertising. Nevertheless, the quantity of advertising (i.e., the media weight) must achieve a threshold level for the advertising to have any positive effects.

Limited online surveys or telephone tracking research (even with modest budgets) can monitor the cumulative effects of advertising on consumer awareness, brand image, and consumer attitudes. This is one of the simplest and most effective ways to make sure that your advertising is doing its job.

Recall of specific messages from advertising is not a very good indicator of advertising effectiveness, and some very effective commercials produce little measurable message recall. Message recall is a positive factor, but its importance should not be overstated. Brand registration , however, is always important (as opposed to message or element recall).

Brand Registration

If consumers don’t remember the brand name, the effectiveness of the advertising is correspondingly reduced. Failure to register the brand name is one of the most common advertising mistakes. The next time you review your advertising, just make sure that the brand name is clearly stated and clearly shown in the commercial. If your brand name is not easy to remember, then more emphasis must be placed on that brand name in commercials.

Advertising-Effectiveness Measures

Ultimate truth is elusive. Advertising effectiveness cannot be determined by any one measure, such as persuasion or recall. Recall is a good measure for some commercials, but not for others. Persuasion scores don’t work very well for brands with high market shares, and they cannot be relied upon for brands in poorly defined product categories.

Purchase intent works reasonably well for new products, but not so well for established products. A large number of important variables must be examined in concert to judge the potential effectiveness of advertising.

Advertising that offends the viewer, or is in poor taste, is almost always ineffective. The only exception to this rule is the commercial that presents a lot of relevant news, where the message is so important that how it is said doesn’t matter much. If viewers like a commercial, its chances of being effective are improved. Likeability, however, is not sufficient in and of itself to ensure advertising success.

From the marketer’s perspective, what are the “secrets” to achieving every company’s goal—advertising that really works? There is no simple “success” formula, unfortunately, but here are some guidelines:

- Advertising works in the arms of sound strategy. What role is advertising to play in the brand’s marketing plan? What messages must the advertising communicate? What images should the advertising project? These are strategy issues, and they bring us to this conclusion: without sound strategy, the chances of advertising success are very low. Several research techniques are available to identify and resolve strategy issues before creative development begins.

- Homework and hard work are more likely to yield effective advertising than creative brilliance and flashes of creative genius. Great advertising evolves from research feedback, tinkering, and tweaking. Pretesting each commercial is a laboratory experiment, an opportunity to learn how to re-edit current creative and how to make the next commercial even better.

- Big egos (creative egos, client egos, research egos, and agency egos) are barriers to the creation of effective advertising, because big egos tend to substitute wishes and emotions for thinking, reasoning, and objectivity. If your agency (or your client) is unwilling to make adjustments to improve the creative product—based upon objective consumer feedback—then you have the wrong agency (or the wrong client).

Advertising Testing

Test your advertising. Show it to members of your target audience and see how they react. No one (not the client, the agency, or the researcher) is smart enough to know how consumers will perceive and react to a given commercial. If you can’t afford one of the advertising-testing services, test it yourself. Show the new commercial and a couple of old ones, and ask some consumers which one would most influence their interest in buying the brand. If you can’t afford that, then ask your spouse what he/she thinks of your advertising. (The latter method is surprisingly accurate, but beware it can lead to a messy divorce.)

Once you have chosen an advertising-testing system, stick with it so that you (the agency, the creatives, the brand managers, and the researchers) all learn how to use the system and how to interpret the test results for your product category and your brand.

“Sticking with” and learning a testing system is more important than which system you select. No testing system is perfect. No testing system can be used blindly. A large dose of intelligent human judgment must always be incorporated into the advertising-evaluation process.

If budgets permit, test at the rough, as well as the finished, stages of creative development. Once you’ve spent $900,000 producing a finished commercial, you might not be very open to research that questions the effectiveness of that commercial. Testing at the rough stage can help you refine the creative before spending the big dollars on production. The more early-stage executions you evaluate, the greater the probability that the winning execution will be effective.

Testing at the finished stage can help guide final editing or re-editing of commercials, can help determine how much weight should be put behind the creative, and can provide understanding to help guide campaign evolution and the creation of subsequent commercials.

Final Thoughts

Be sure your advertising puts enough emphasis upon the brand name so that the audience will remember it. Don’t forget to give buyers some positive information about your product (i.e., a reason to purchase), and, last but not least, don’t forget to pretest your advertising. Good luck!

About the Author

Jerry W. Thomas ( [email protected] ) is President/CEO of Dallas-Fort Worth based Decision Analyst. He may be reached at 1-800-262-5974 or 1-817-640-6166 .

Copyright © 2022 by Decision Analyst. This article may not be copied, published, or used in any way without written permission of Decision Analyst.

Related Services

- < Advertising Research Services

- Concept Testing Services

- Case Study: Advertising Testing Among Hispanics by Decision Analyst

- CopyCheck of Animatic Ads

- Using a MaxDiff Analysis to Make Decisions

- Advertising Tracking: Tracking the Effectiveness of Media Research

- Optimizing Messaging & Positioning With Choice Modeling

- Positioning—Marketing’s Fifth “P”

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

The Emotional Effectiveness of Advertisement

Associated data.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Based on cognitive–emotional neuroscience, the effectiveness of advertisement is measured in terms of individuals’ unconscious emotional responses. Using AFFDEX to record and analyze facial expressions, a combination of indicators that track both basic emotions and individual involvement is used to quantitatively determine if a spot causes high levels of ad liking in terms of attention, engagement, valence, and joy. We use as a test case a real campaign, in which a spot composed of 31 scenes (images, text, and the brand logo) is shown to subjects divided into five groups in terms of age and gender. The target group of mature women shows statistically more positive emotions and involvement than the rest of the groups, demonstrating the emotional effectiveness of the spot. Each other experimental groups show specific negative emotions as a function of their age and for certain blocks of scenes.

Introduction

Measuring the effectiveness of an advertising campaign is a major challenge for most companies, marketing professionals, and scientists in the twenty-first century ( McCarthy and McDaniel, 2000 ). Starting back in the 1960s, a first conceptual model was developed to define the effectiveness of advertising. The “Hierarchy of Effects” model ( Lavidge and Steiner, 1961 ) articulated customer response to spots in three stages: (1) cognitive, characterized by consciousness and information gathering, (2) affective, where liking for the spot and preferences for the product are set, and (3) behavior, where propensity or actual buy takes place. Following this model, the measurement of the impact of the consumer’s response to advertising campaigns was carried out through studies primarily aimed at the conscious cognitive processes of consumers (self-reporting, surveys, focus groups, etc.; Lewinski et al., 2014 ). These approaches generally failed to provide clear findings because they were not able to observe what happens in the consumer’s brain while taking a decision, they did not understand the role that emotions play both in understanding the message and in decision making, and they did not fully capture the way in which consumers process and understand cognitive responses to messages in advertising ( Morin, 2011 ; Bercea, 2012 ; Cherubino et al., 2019 ). Moreover, in most cases, these techniques generated strong biases, such as social desirability ( Benstead, 2013 ).

A new discipline, called consumer neuroscience, was born to try to resolve these voids of the previous model, going beyond emphasizing the conscious cognitive processes. Consumer neuroscience based “its objective in better understanding the consumer, through their unconscious processes. Explaining consumer preferences, motivations and expectations, predicting their behavior, and explaining successes or failures of advertising messages” ( Bercea, 2012 ).

Consumer neuroscience was developed to penetrate in the consumers’ brain, and one of its focuses is on measuring effectiveness of advertising more precisely. The focus was shifted from the cognitive processes (stage 1 of the “Hierarchy of Effects” model), which were no longer considered to be the main drivers of consumer behavior, toward emotions and sentiments (primarily stage 2), which incorporated perceptions, experience, and recall ( Halls, 2002 ). More precisely, marketing professionals and researchers, when measuring emotional responses following consumer neuroscience principles, were able to evaluate the unconscious assessment of the respondent ( Poels and Dewitte, 2006 ; Lewinski et al., 2014 ; Varan et al., 2015 ), thereby providing a greater understanding of the effects of emotion on memory ( Vecchiato et al., 2013 ).

Since the turn of the century, emotions have therefore been proposed to be a good predictor of advertising effectiveness ( Poels and Dewitte, 2006 ) with a known important impact also in the cognitive process ( Hamelin et al., 2017 ). Moreover, emotions have demonstrated to be necessary for the human function because they are strongly correlated with attention, decision-making, and memory ( Le Blanc et al., 2014 ). Emotions also had an impact on the allocation of resources to the visual system and that more attention is placed on negative than on neutral stimuli ( Öhman and Mineka, 2001 ; Algom et al., 2004 ; Estes and Verges, 2008 ).

Emotions have also been shown to impact highly on an individual’s response to receiving a message ( Mai and Schoeller, 2009 ; Lewinski et al., 2014 ). Likewise, providing an emotional message in publicity increases the audience’s attention to the advertisement, and the product enhances the product’s appeal and generates a higher level of brand recall. Indeed, advertisements with emotional content are more likely to be remembered than those conveying news ( Page et al., 1990 ).

Therefore, one necessary approach in this day and age to quantify the effectiveness of advertisements is to resort to emotions and emotional responses in the quest for properly measuring “ad liking and purchase intent” ( McDuff et al., 2015 ).

To successfully achieve this quantitative challenging task, the pillars of consumer neuroscience are cognitive–emotional neuroscience, neuroimaging technologies, and biometric measurements, which together allow for obtaining objective data about emotions after observing and studying in real time what happens inside the consumer’s brain. The available tools permit the analysis of emotional activity without cognitive biases, providing instantaneous and continuous data that can be broken down into small pieces of study.

Accordingly, both advertising and marketing companies look for new or improved models, methodologies, indicators, tools, and techniques that can evaluate and predict consumer behavior based on unconscious emotional responses, making it difficult for customers to hide their true response. Some of these tools focuses on recording in a real environment or using virtual reality (VR) the metabolic activity [functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), positron emission tomography], others on recording electrical activity in the brain [electroencephalography (EEG), magnetoencephalography, transcranial magnetic stimulation, steady-state topography], and still others without recording brain activity [eye tracking (ET), galvanic skin response (GSR), electromyography (EMG) or facial expression recognition].

These neuroscience tools are becoming popular for quantifying the emotional effectiveness advertising, especially (1) ET ( Wedel and Pieters, 2008 ; Ramsøy et al., 2012 ; Lewinski et al., 2014 ; De Oliveira et al., 2015 ), (2) analysis of facial microexpression ( Teixeira et al., 2012 ; Lewinski et al., 2014 ; Wedel and Pieters, 2014 ; Taggart et al., 2016 ), (3) fMRI ( Bakalash and Riemer, 2013 ; Venkatraman et al., 2015 ; Couwenberg et al., 2017 ), and (4) VR ( Bigné et al., 2016 ).

As for the analysis of facial microexpressions, different software was used to assess the effectiveness of advertising using the Facial Action Coding System, for example, FaceReader-FEBE system ( Lewinski et al., 2014 ), GfK-EMO Scan software ( Hamelin et al., 2017 ), and FACET and AFFDEX ( Stöckli et al., 2018 ).

In all these studies, the measurement of emotions was mainly focused on understanding the seven basic emotions proposed by Ekman (1972) : two positive (joy and surprise) and five negative (anger, contempt, disgust, fear, and sadness). In some cases, valence was also analyzed, directly from facial expressions or coupled with questionnaires ( Timme and Brand, 2020 ).

It is important that all the available information is used to enrich the studies. On that regard, AFFDEX is a state-of-the-art software that, after recording people’s faces in front of stimuli, provides not only seven indicators about the likelihood on the emotional response being present in terms of the Ekman’s basic emotions, but also three additional indicators about the emotional involvement of the individual, namely, attention (focus of the participants during the experiment based on head position), engagement (the emotional responsiveness that the stimuli trigger), and valence (the positive or negative nature of their experimental experience; iMotions, 2020 ). All of the seven emotional indicators are scored in a normalized scale indicating the proportional likelihood of detecting the emotion. Attention and engagement have a range from 0 to 100, whereas the range of valence is from −100 to 100, providing an indication of positive, neutral, or negative experience. The initial thresholds are usually arbitrarily set at ±50 ( iMotions, 2020 ).

Its applications in the last few years in diverse fields are numerous, for example:

- geriatric care ( Taggart et al., 2016 ),

- forensics ( Lei et al., 2017 ; Kielt et al., 2018 ),

- pain studies ( Xu and Sa, 2020 ),

- sport ( Timme and Brand, 2020 ),

- the influence of negative emotions on driving ( Braun et al., 2019 ), and

- consumer satisfaction from tourism ( González-Rodríguez et al., 2020 ).

To our knowledge, AFFDEX has not been yet applied in marketing to its full potential. One key novelty of this study is the integration of the three involvement measures together with the analysis of the seven basic emotions to develop a framework to quantify emotional effectiveness of commercial advertising ( Figure 1 ). We believe that the joint use of these complementary measures provides new insights into the emotional response that the advertisement provokes to fully measure the effectiveness of a given spot. Moreover, as will be demonstrated in this article, the differences among scenes of the spots or among the groups of viewers of the advertisement might be analyzed in detail.

Framework to quantify emotional effectiveness by target group and/or blocks of scenes.

The theoretical objective of this research is therefore to shed new light on the quantification of the emotional effectiveness of advertising among different groups based on the measurement and joint specification of emotions and emotional involvement using the analysis of facial expressions provided by AFFDEX and its 10 indicators.

Accordingly, we propose within this framework a set of three hypotheses to measure the emotional effectiveness of advertisement. The first hypothesis is stated as:

- the average level of attention is high (≥50 in AFFDEX),

- the average level of engagement is high (≥50 in AFFDEX),

- the average level of valence is positive (≥0 in AFFDEX), and

- the predominant emotion is joy and its average level is high (≥50 in AFFDEX).

Indeed, one of the objectives in advertising communication is to achieve high levels of attention and engagement because emotions are highly correlated with decision-making and memory ( Le Blanc et al., 2014 ). Thus, high levels of engagement to an advertisement influence long-term memory and increase consumer purchase ( Loewenstein, 1966 ; Kiehl et al., 2001 ; Öhman and Mineka, 2001 ; Algom et al., 2004 ; Estes and Verges, 2008 ; Milosavlejevic and Cerf, 2008 ; Ramsøy et al., 2012 ; Le Blanc et al., 2014 ).

We propose valence to understand the general emotional experience. The analysis of valence allows us to understand the quality, positive or negative, of the emotions. A positive valence in commercial advertising reflects approaching behavior, whereas a negative valence is a sign of distancing behavior ( Timme and Brand, 2020 ). Similarly, in order to demonstrate ad liking, out of the seven emotions, the predominant one must be joy ( Tomkovick et al., 2001 ; Lewinski et al., 2014 ; Shehu et al., 2016 ).

A second hypothesis relates to the sequence of scenes or maybe block of scenes of the advertisement and the aim to measure if the emotions are stable throughout the whole length of the spot or some scenes trigger certain emotions ( Dimberg et al., 2011 ).

- Hypothesis 2: An advertisement is emotionally effective across scenes whenever the indicators for some scenes are higher on average than the indicators for the rest of the scenes in the spot.

We propose Hypothesis 2 after realizing that spots are usually broken into scenes to compare among spots that differ only in one scene or to focus on the scene of a single spot that triggers the emotions that are sought ( Lienhart et al., 1997 ; Teixeira et al., 2012 , 2014 ; Braun et al., 2013 ; Vecchiato et al., 2014 ; Yang et al., 2015 ). In fact, if Hypothesis 2 is accepted because of differences between scenes, a deeper analysis could and should be carried out to determine why some scenes are more emotional than others. If Hypothesis 2 is rejected, the conclusion might be that the scenes provoke stable emotions throughout the length of the spot.

Finally, an effective advertisement is also one that reaches its target audience and positively influences the emotional attitude and responses of the consumers ( Meyers-Levy and Malaviya, 1999 ; Lee et al., 2015 ). The experimental objective of many studies is to evaluate the effectiveness of the advertisement in terms of ad liking for the different groups of participants, differentiating between the target group and the rest of participants ( Kotler et al., 2000 ; Ansari and Riasi, 2016 ; Gountas et al., 2019 ). The third hypothesis might accordingly be stated as follows:

- Hypothesis 3: An advertisement is emotionally effective for the target group whenever the indicators for this group are higher on average than the indicators for the rest of participants.

As a test case to validate the framework, this study aims to quantify the effectiveness of advertisement using a 91-s commercial spot composed by 31 scenes made by Scotch-Brite and its line of scouring pads to celebrate the sixtieth anniversary of the brand’s presence in Spain. The spot shows scenes along the lifetime of women while the study focuses on mature women and moms as the target group to compensate their lifelong efforts on raising children and creating family ties while buying and using its products and developing the brand’s name.

The article is structured as follows. After setting the theoretical background and the framework to measure effectiveness of advertisement in this introduction, “Materials and Methods” section explains the method of analysis based on facial expressions as well as the experimental setting, including the spot and its scenes and the grouping of subjects. “Results” section shows the results by scene and gender and statistically test the hypothesis. “Discussion” section is used to discuss the possibilities of emotions being the tool for marketing in the future.

Materials and Methods

Affdex, the analysis of facial expressions and emotional reactions.

Facial expressions are a gateway to the human mind, emotion, and identity. They are a way of relating to others, of sharing understanding and compassion. They are also a way of expressing joy, pain, sorrow, remorse, and lack of understanding ( Taggart et al., 2016 ). These characteristics can be crucial while capturing the key features of a stimulus in the form of a video or image frame. Individual facial recording while watching the computer screen is compared with a biometric database that represents “true” emotional faces, while looking for similarities or even a possible match. Therefore, facial recognition is used to measure and analyze the emotional reactions of the subjects to a given stimulus.

To carry out the emotional measurements in this study, a software platform for biometric measurements research called iMotions was used ( iMotions, 2020 ). This company indicates that its software can combine “eye tracking, facial expression analysis, EEG, GSR, EMG, ECG, and surveys” ( Taggart et al., 2016 ). The platform is used for various types of academic and business research. Version 7.0 was used in this research.

The software records several raw indicators per frame based on biometric measurements or action units while an experimental subject is watching a stimulus on the computer screen: 34 core facial landmarks (jaw, brows, nose…), interocular distance, and head position (yaw, pitch, and roll).

The recorded values for the raw indicators are then transformed by the software underlying models into Ekman’s seven basic emotions. An indicator for each emotion is provided based on the probability of appearance of the emotion, so the range of values for each of them is from 0 to 100. A value of 50 is proposed by AFFDEX as an initial threshold to determine if an emotional response has been detected.

Three involvement indicators are also calculated after combining the raw values. Attention is calculated from the head position and gives an indication of the focus of the individual. Attention ranges from 0 to 100, although is not a probability. Engagement or the level of responsiveness has also a range from 0 to 100. Finally, the range of valence is from −100 to 100, providing an indication of positive, neutral, or negative experience. The initial thresholds are usually arbitrarily set at ±50.

The Stimulus: The Spot

The stimulus was a spot that belonged to a campaign to mark the sixtieth anniversary of the Scotch-Brite brand’s presence in Spain. The video presentation of the spot lasted 91 s and was broadcast on social networks 1 .

The content of the video describes the accompanying role that a mother plays throughout the life of a child, from birth to adulthood. The video was split into 31 scenes by the advertising company ( Table 1 ). There are 22 real images with family connotations, six frames with text, a black scene, the logo of the sixtieth anniversary, and the campaign’s hashtag.

Description of the scenes.

The Experiment

Recruitment to watch the spot was done through a snowball process. Snowball is traditionally used whenever the theme of study is relatively new ( Strydom and Delport, 2005 ) and for which it is difficult to find participants ( Babbie, 2008 ). This type of sampling is particularly used to influence in the buying process of both consumers and nonconsumers ( Rozalia 2007 , Venter et al., 2011 ).

The snowball process helps complete the sample based on a specified set of criteria ( Henning et al., 2004 ), once the first subjects are selected ( McDaniel and Gates, 2007 ). For this research, the target group had to be habitual consumers and users of scoring pads and older than 18 years. The first requisite, that of consumers and users, drove the sample toward women, because they are primarily those that do the housework. Seventy-eight percent of European women (84.5% in Spain) perform house cleaning (which includes dishwashing), whereas only 33.7% (41.9% in Spain) of the men do ( EIGE, 2018 ).

The recruiting process started with a first sample provided by the company that produced the spot, both consumers and nonconsumers. The first contact was made by telephone after randomly selecting the potential participants, and if available, they were scheduled to go to the research site and participate by watching the video. These selected subjects were also asked to provide contacts to guarantee a continuous chain of sampling ( Strydom and Delport, 2005 ).

The subjects were divided into two large groups: that of product consumers or the target group (mature women between the ages of 50 and 65 years) and that of nonconsumers. To further divide the nonconsumers, while keeping the gender perspective, the decision was to divide the women in two groups by age (young and middle aged) and assign men to a third group. Four groups were therefore available at the initial stages of sampling: three for women and one for men.

However, while interviewing the initial set of participants, we identified some rejection or repulse to the theme under study, that of washing dishes with scouring pads. As a consequence, it made sense to include women with a strong feminist sensitivity as a separate fifth group. This additional “feminist” group was identified by asking women the following question:

“As for the social movements that claim to incorporate the gender perspective in the different instances of society, up to what level do you identify with this type of proposal?”

The answer had to be provided using a 10-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (nothing identified) to 10 (fully identified). Those women regardless of age who responded with scores between 8 and 10 were included in this special group.

As a result of the snowball process, 100 people participated in the experiment (80 women and 20 men, between 18 and 65 years old). The five groups with 20 people each were then defined as follows:

- group 1: young women, aged 18–29 years

- group 2: middle-aged women, aged 30–49 years

- group 3: mature women, aged 50–65 years

- group 4: women with a strong feminist sensitivity, aged 18–65 years

- group 5: men, aged 35–65 years

The experiment was carried out at the Brain Research Lab of the Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Madrid, Spain, between November 10, 2018, and December 10, 2018. The room was kept at a constant temperature of 22°C throughout the experimentation phase. The room was isolated from the outside by means of a soundproofing system. We also used the same indirect lighting system for all the participants, so the emotional comparison across groups of subjects was robust.

The participants were scheduled in 10-min intervals and viewed the video on their own. The subjects entered the room, where they sat in front of a 14-inch monitor on which the spot would be projected, at a distance of 50 cm from the screen. On top the screen, there was a Logitech HD recording camera. iMotions was then calibrated to ensure that the facial microexpression detection mask captured the entire face of the subjects. Once an adjustment of 96% was achieved by iMotions, the spot was viewed. They did not know a priori what the spot was about.

The participants received a compensation of 20 euros for their collaboration. All subjects signed a priori a consent form that considers all aspects of data protection. This consent ensures the nonidentification of the participants, nor the dissemination of individualized data of a personal nature.

Statistical Methods

We developed a database with the 10 indicators provided by AFFDEX by scene and subject. Because 100 individuals watched the 31 scenes of spot, there were 3,100 registers in the database, each with 10 columns, one per indicator. Each indicator ranges between 0 and 100, indicating the likelihood of the emotion being present (0 = absent, 100 = present). Therefore, the higher the values that are recorded, the higher the emotional levels that are shown. Two additional columns were added to identify each register with the levels of the two control variables: scene (1–31) and group (1–5).

A descriptive analysis was first carried out to obtain an overall idea of the emotional responsiveness to the spot. Besides providing plots and summary statistics of the whole set of records, the extreme values, defined as those above the 90 th percentile and below the 10 th percentile, were highlighted in colors (green for high, red for low).

An inferential analysis was then undertaken to compare the average values of the different levels of the control variables. The general linear analysis of variance (ANOVA) model was used to capture the differences among levels of one variable at a time, as well as both variables together. A series of F tests (one per each of the 10 emotional indicators) were used to statistically reject (or not) the null hypothesis of equality of means across levels. A significance value of 5% was used as the threshold for rejection. The corresponding values of p were calculated, highlighting those that are lower than 5%, to demonstrate which variables significantly influence on the emotional responses by group and/or scene.

Concerning which levels of the variable are significantly different than the rest, we performed a series of t -tests, maintaining the significance level at 5% The values of p are provided, highlighting those that are lower than 5%, to demonstrate which levels of the variables significantly influence on the emotions. A “+” sign was used to demonstrate higher values than average, and a “−” to depict lower values than average.

Overall Results

The results for the three involvement indicators and the seven basic emotions are shown in Table 2 and depicted in Figure 2 . Each observation in the plot is the average measurement by individual and scene, for a total of 3,100 samples (31 scenes and 100 subjects) in each of the 10 plots. The lower and upper sides of the boxes correspond to the first and third quartiles, with the dots indicating the values outside the box. For illustrative purposes, and following AFFDEX initial configuration, thresholds are shown at ±50. Nevertheless, the research is based on the whole set of values.

Descriptive statistics for the whole sample by emotional response.

Descriptive plot for the whole sample by emotional response.

Only four of the indicators show reads consistently outside the thresholds and almost reaching the maximum value of 100: attention, engagement, valence, and joy. None of the five negative emotions reach 100, with only a few combinations of scene and individual above 50 for anger (three reads, 0.1%) and contempt (five reads, 0.02%). Moreover, three of the negative emotions (disgust, fear, and sadness) do not even reach the initial threshold.

Starting with attention, all the values are above 75 except for only a single value at 61.22. The lower quartile is above 96. Therefore, attention during the spot is kept across the individuals. High mean values (≥50) for this indicator show involvement and therefore emotional effectiveness, corroborating Hypothesis 1a.

Engagement shows most of the values under the threshold, but 309 of the 3,100 (10%) are above the limit. Whereas the third quartile is just at 9.27 and the average at 12.34. Because these values are not high (<50), Hypothesis 1b is not fully supported for the entire sample, but it looks worthy to investigate emotional reactions further by segregating by scene and group.

The same happens for valence, which shows more values above the positive threshold (168, 5.4%, maximum at 99.94) than below −50 (12, 0.4%, minimum at −76.24). Hypothesis 1c is not fully supported either for the entire sample, because not a significant amount of the samples is positive.

The predominant emotion is joy, with the percentage of values above 50 (probability of the emotion being present) being 4.7% (147 observations). Once again, from a descriptive perspective, the percentage is low enough to not accept Hypothesis 1d for the entire sample.

The overall descriptive analysis implies that the positive emotions are present at times, whereas the negative ones are almost never shown. Although the hypotheses are not fully accepted for the whole sample, the aim behind the spot is that the positive emotions are shown primarily by the target group, triggered by the sequence of images and text. Let us proceed therefore with the inferential analysis by scene and gender and age groups in order to quantify emotional effectiveness.

Results by Scene

Figure 3 shows the results averaged across individuals for each of the 31 scenes. For each of the 10 emotional indicators, the three scenes (first decile or top 10%) with the highest values are highlighted in green, and the three scenes with the lowest values in red.

Inferential analysis per scene.

The main green zone for positive emotions and involvement indicators goes from scene 9 to scene 15. Attention provides the two highest values in this block of scenes, with engagement, valence, and joy providing all of their top three scores. Fear and sadness also give maxima in this block. The text scenes are “She taught us how to grow” and “She gave us the most sincere love,” both related to the important role of moms. It must be remembered at this point that mature women are the target of the spot.

The negative emotions are higher at the beginning (scenes 1–4, anger and contempt) and at the end of the spot (29–31, disgust). It is eye catching that the scene with the company logo, scene 30, shows a peak of disgust, not showing any high values for the rest of the indicators except for surprise. The lower peaks of involvement (in red) are found between scenes 16 and 22, whereas joy is low between scenes 5 and 8.

To statistically test if these visual differences are significant per indicator, a series of one-way ANOVA test are performed. The null hypothesis is that the average value for each scene is the same, and the alternative hypothesis is that not all the scene averages are equal. The bottom rows of Figure 2 include the values of F and the p of each test ( p < 0.05 for rejection). Only anger (three individual values above 50) and fear (0 observations over 50), both negative emotions with very low averages, show differences across scenes. Their peaks surprisingly occur while positive emotions flourish, whereas their valleys are found at the end of the spot.

The summary is that Hypothesis 2 is not corroborated for scenes because no significant differences are found across them. Therefore, no clear emotional effectiveness by scene is shown. It is worth highlighting that the three involvement indicators and joy (relating all four to Hypothesis 1) are stable throughout.

To deeper analyze the spot, we continue the study in terms of block of scenes and not just single scenes. After the results of the descriptive analysis based on top and bottom deciles, we have broken the scenes into five blocks, which have been named according to a common theme:

- block 1: birth (1–4),

- block 2: first cares (5–8),

- block 3: teaching growth and love (9–15),

- block 4: sharing the best moments (16–22),

- block 5: reunion of three generations (23–28), and

- block 6: logo (29–31).

Figure 4 includes the statistical analysis by block. Differences are found on average emotional involvement across blocks of scenes in engagement and valence, with block 3 related to growth and love obtaining the highest results for involvement and positive emotions. Correspondingly, block 3 causes joy, although it is also significantly different in fear.

Inferential analysis per group.

Block 1, related to birth, is significantly high in negative emotions of contempt and sadness. Block 2 shows low values for positive emotions, block 4 for engagement, and block 5 for attention and contempt. Finally, and although the indicator is not significant, block 6 shows a peak of contempt.

Therefore, Hypothesis 2 is corroborated for blocks, providing an indication that the advertisement provokes emotions unevenly along the duration of the commercial. The spot is emotionally effective for blocks of scenes, in this case, generating higher positive involvement and joy for block 3: teaching growth and love.

Results by Group

The analysis of the groups is critical also to determine ad liking, specifically for the target group. Figure 5 has the same format as Figures 3 , ,4 4 but, instead of segregating by scene, the averages are calculated for each of the five groups in which the individuals were pooled together. The maximum values per indicator are highlighted in green, and the minimum values in red.

Inferential analysis per block.