- RUSSO-UKRAINIAN WAR

- BECOME A MEMBER

Recovering a Balance-of-Power Principle for the 21st Century

Post title post title post title post title.

Writing in Foreign Affairs at the start of 2021, Kurt Campbell and Rush Doshi, now senior American officials in charge of policy towards China, argued that a balance-of-power framework was needed for the region of East Asia. Using Henry Kissinger’s study of the 1814–15 Congress of Vienna as a guide, they described such a balance as potentially serving as the foundation of “an order that the region’s states recognize as legitimate.” From what I could discern, the article received surprisingly little attention, and the extent to which this thinking now drives America’s China policy remains hidden to those outside the White House. Nonetheless, the mention of such an approach to diplomacy, particularly at a time when a consensus considers the international order to be in a moment of systemic transition, is an idea worthy of investigation.

The term “balance of power” is one of the more overused and misunderstood in the modern English lexicon. It is invoked across a range of disciplines and industries, usually to describe the arrangement of certain subjects or phenomena in relation to one another. The journalist Brian Windhorst, for example, recently described the playoff series between the Boston Celtics and Milwaukee Bucks as one in which the “balance of power [was] constantly shifting” between the teams over the course of seven games. In an entirely different context, Rae Hart writes in the Jacobin that the “balance of power in the economy” must move “away from capital and toward working people.” Such variances in meaning seem to confirm the historian Albert Pollard’s view — one nearly 100 years-old — that the term “may mean almost anything; and it is used not only in different senses by different people, or in difference senses by the same people at different times, but in different senses by the same person at the same time.”

For those concerned with American foreign policy, the concept suffers from lazy usage, a reality which gives rise to certain misconceptions around its purpose and its nature. For some, the concept is synonymous with the measure of material power, whether military, economic, financial, or technological. For example, Michael Horowitz has written of how advancements in AI can affect the balance of global power. Others see it as a tool or method of statecraft, but this tends to be of a certain school of thought — one that is colored by stark power considerations devoid of ethical principles. Along these lines, Stephen Walt has criticized the lack of a balance-of-power approach in American statecraft, yet the concept is seen to be soulless, a mechanical creation operating in an inanimate system. Like other realists, the concept of a balance of power is seen to be a hard-headed, sober approach to the distribution of power in an anarchic system of states.

Like so many other terms that are regularly invoked in the study and practice of international politics — for example realpolitik , raison d’état , prudence, nationalism, internationalism, and world order — there is a generational need to re-examine the intellectual and historical roots of these concepts, how they have evolved over time, and the ways they are used and misused in the modern day. This is because scholars and practitioners have not so much arrived at certain truths of international politics as settled on certain perceptions, ones conditioned by the time in which they live. Ideas themselves, as Alfred Vagts once put it , “are like rivers arising in a swamp or moor region rather than in a mountain spring, and often they see the light of day only after they have run for miles through subterranean caverns.”

With this reflection as a guide, this essay examines certain interpretations of the balance of power concept throughout history. It is selective rather than comprehensive, and it aims to shine light on an older, seemingly forgotten variety of the idea. Specifically, it illuminates the view that seeking such a balance is not always intended for naked self-interest and self-help. Instead, we might look to older conceptions of a balance among powers, particularly those ideas that grew up in Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries. Here a fundamental principle was that the objective of a balance of power rested not solely in the preservation of one’s interest, but in a wider interest, or unity, of the whole.

What might that be today? The exact application, if any, remains an open question, yet the basic insight here is that the concept of the balance of power should be understood as something more than a mechanical or immoral method of statecraft. It is instead an approach that can hold as its objective an ethical order deemed legitimate by the principal states or groups of states in a regional or international system. In grasping this older conception of the balance of power, we can embody an approach to statecraft that not only sees the relationship between power and ethics as intertwined but also provides a more robust intellectual framework in this period of systemic international transition. The Russo-Ukrainian War has made the most fundamental questions — of power, morals, law, institutions, and order — starkly relevant once again. For policymakers and analysts, returning to and expanding our understanding of those concepts we take for granted, the balance of power among them, is a first step towards planning for and calibrating a future international system.

American Conceptions of the Balance of Power

At various points in the first half of the 20th century, the balance of power was derided as an outdated and immoral form of diplomacy. Considering it a traditional practice of European nations, American leaders tended to see it as inherently destabilizing and an approach to politics that held great dangers for the United States. President Woodrow Wilson, who has the distinction of having ushered in a major intellectual spring of American statecraft, based his views, in part, on a philosophical aversion to the balance of power. Echoing the calls of the British politicians Richard Cobden and John Bright nearly a century before — the latter had called it a “foul idol” — Wilson stood before the Senate in January 1917 to argue that “Only a tranquil Europe can be a stable Europe. … There must be, not a balance of power, but a community of power; not organized rivalries, but an organized common peace.”

The failure of the League of Nations to thwart aggression in the 1930s, and the power politics that engulfed East Asia, Eastern Africa, and Western Europe over the course of that decade, led Wilson’s democratic successors in the Roosevelt administration to champion a similar message. Speaking after the conclusion of the Moscow Conference in October 1943, Secretary of State Cordell Hull affirmed that what the United States, United Kingdom, and Soviet Union were planning for the post-war world would, and must, put an end to the balance-of-power system that had plagued global politics for centuries. A similar line was taken by Franklin Roosevelt, who, in what would be his last address to Congress on March 1, 1945, described the purported achievements of the Yalta Conference. “It ought to spell the end of the system of unilateral action, the exclusive alliances, the spheres of influence, the balances of power, and all the other expedients that have been tried for centuries — and have always failed.”

Such statements, combined with the tendency of American statesmen to remain non-committed or “disentangled” from the politics of the European powers in the 19th century, can lead us to view the record of American diplomatic history as one traditionally averse to the balance of power concept. But is this the case?

It is no secret that American leaders have been conscious of this phenomenon in international politics. In 1787, Alexander Hamilton wrote in the Federalist No. 11 that the United States needed to be the arbiter of the balance of European competition in the new world. Decades later, the famed Monroe Doctrine of 1823 had as its principal aim the consolidation of American power in the Western hemisphere, but as Charles Edel has rightly noted , to say that American leaders were uninterested in the European balance of power would be a discredit to their international thought. Similarly, Theodore Roosevelt grasped this concept, and while he ostensibly kept the United States out of European balance-of-power arrangements, he thought about the world balance on a more global scale — a premise that led him in part to the idea of needing to be dominant in the western hemisphere. “No other president defined America’s world role so completely in terms of national interest, or identified the national interest so comprehensively with the balance of power,” Henry Kissinger wrote of the 26th president. The record of American diplomacy in this regard led some, including Hans Morgenthau and Alfred Vagts, to argue that such notions, attractive or not, have always been a focus for leaders in Washington. Morgenthau went so far as to say that, with the exception of the War of 1812, the United States had regularly “supported whatever European power appeared capable of restoring the balance of power by resisting and defeating the would-be conqueror.”

If the balance of power as a method of statecraft was more veiled in the 19th and early 20th centuries, its application during the period of the Cold War seemed to become more apparent. Arnold Wolfers wrote in 1959 that the concept had become “intimately related to matters of immediate practical importance to the United States and its allies.” Kissinger and Richard Nixon are perhaps the American statesmen most associated with the balance of power given their policy towards China vis-à-vis the Soviet Union. As a scholar, Kissinger had cut his teeth on the study of the Congress of Vienna and the European system in the first decades after the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars, but while he valued this systemic arrangement as a practitioner, he also believed that the concept had fundamentally changed. “Today’s striving for equilibrium should not be compared to the balance of power of previous periods,” he told an audience gathered in Washington in 1973. “The very notion of ‘operating’ a classical balance of power disintegrates when the change required to upset the balance is so large that it cannot be achieved by limited means.” He had in mind here the modern intensity of ideology — specifically between liberalism and communism — and how these conflicting positions ultimately prevented a common notion of legitimacy. Similarly, although for different reasons, Stanley Hoffman described the irrelevance of the term: “The balance of power familiar to students of history is the past; there is no future in our past.”

Other writers in these decades saw it differently, however, and the balance-of-power concept became further associated with the giants of the realist school of international relations. Scholars such as Kenneth Waltz and, later, John Mearsheimer, held that the balance of power, more so than a conscious method of statecraft, was simply the reality of international politics. In other words, nation-states — operating independently and instinctively — would, naturally develop toward a system in which a balance of power was the best they could hope for. It was, Waltz argued as early as 1954, “not so much imposed by statesmen on events as it is imposed by events on statesmen.” The motivations for pursuing a balance of power thus came to be seen as a kind of natural condition, one created by the conscious or unconscious pursuit of material power.

Recovering an Older Interpretation

Scholars of Western political thought have detected approaches resembling the balance of power as far back as Ancient Greece. Traces are indeed discoverable in the writings of Xenophon , Thucydides , and Polybius , among others. The Scottish polymath David Hume was one of the first writers to recognise these older influences. “The maxim of preserving the balance of power is founded so much on common sense and obvious reasoning, that it is impossible it could altogether have escaped antiquity,” he argued . “If it was not so generally known and acknowledged as at present, it had, at least, an influence on all the wiser and more experienced princes and politicians.”

The more recognisable form of the balance of power, however, both in its theory and application, has its roots in the 15th-century diplomacy of Italian city-states. It was in this period that powers like Venice, Milan, Naples, Florence, and the Papal States developed alliances to balance against one another (one example was the triple alliance of Florence, Milan, and Naples against Venice). As Francesco Guicciardini phrased it, these states

were unremitting in the watch that they kept on one another’s movements, deranging one another’s plans whenever they thought that a partner was going to increase his dominion or prestige. And all this did not make the peace any less stable, but rather made the powers more alert and more ready to bring about the immediate extinction of all those sparks that might start a fire.

Importantly, it was in these years that writers began to conceptualize and advocate such a practice, one that could be used as a tool or mechanism by statesmen of the time.

Into the 17th century, the number of writers examining and opining on the balance of power grew rapidly. The reasons for this are diverse. On the one hand, these decades were a period of great advancement in the natural sciences, particularly physics, which gave rise both to new approaches to understanding the world and to efforts to apply these methods to the study of human societies. “The modern law of inertia, the modern theory of motion,” Herbert Butterfield once described , “is the great factor which in the seventeenth century helped to drive the spirits out of the world and opened the way to a universe that ran like a piece of clockwork.” This had an important influence on those concerned with politics between societies. More so than in the preceding centuries, there was a feeling that the problems raised by political and economic competition could be solved by new, discoverable solutions. The balance of power had become, as Martin Wight once noted , the “political counterpart of Newtonian physics.”

As one of the great historians to examine the iterations of the balance of power concept in European history, Wight highlighted , among other phenomena, the dominant religions of the period. The “earliest stable balance” on continent, he argued, had been that between the Catholics and Lutherans, codified in the Peace of Augsburg. There was also the influence of the theory of “mixed constitution,” which had its origins in Platonic and Aristotelian political philosophy and worked out its modern form in the Netherlands, Britain, and Germany. But one of his great illuminations was the balance-of-power approach employed by William III, who negotiated the first and second Grand Alliances of 1689 and 1701. Both groupings were initiated in peacetime and designed to counter the power of France on the European continent. Though William died shortly after the second agreement, his efforts helped to bring into existence the treaties of Utrecht in 1713 . The profound aspect of this diplomatic achievement was this: The balance of power principle was geared at upholding a larger moral framework, namely the “ res publica Christiana ” throughout Europe.

Into the 19th century, this view concerning the purpose of the balance of power was championed by the likes of the German historian Arnold Heeren, who said of the balance of power, “What is necessary to its preservation has at all times been a question for the highest political wisdom.” To see it as a simple exercise of balancing material capabilities, he warned, was to misunderstand its purpose. “Nothing […] but the most short-sighted policy would ever seek for its final settlement by an equal division of the physical force of the different states.” In other words, those aiming at a balance of power would need to hold in their minds an understanding of its ultimate purpose.

In the same century, another German historian wrote what became one of the most important reflections on the balance of power concept. Leopold von Ranke’s 1833 essay titled The Great Powers set out to examine the European order between the reign of Louis XIV and the defeat of Napoleon. The balance of power, he argued , was the key to maintaining such a system. Moreover, there was something unique about how the concept was understood in this period — something that, in equal measure, legitimized and justified its existence. In his mind, that the European powers were part of a wider European civilization, with a shared history between them, allowed them to develop and implement a balance of power, while this balance, when executed properly, allowed each society to continue to develop according to the values it held universal.

The Return of Statecraft and the Role of Ideas

The writing here has been an exercise in recovery rather than reconstitution. Its aim has been to shine light on older and diverse approaches to the concept of a balance of power, as a way of broadening the discourse around future American foreign policy in an increasingly multipolar world. Older approaches, concepts, and ideas of statecraft become buried under the succession of events and, more consequentially, shaded by the mythical notions that grow up around these moments or periods of history. It is the responsibility of historians and scholars of international politics to, from time to time, excavate and re-examine these earlier precedents. This is not to reveal truths as much as insights, ones that might be seized upon by the official or analyst looking for a guide in the maelstrom of immediate objectives.

The balance-of-power concept as understood in the United States today tends either to carry the dark undertones highlighted by Richard Cobden and John Bright and advanced by Woodrow Wilson, or to be viewed as the soulless approach of self-styled realists. What is lost is a different interpretation, one that sees the balance of power as a purposeful approach to statecraft, one that can and ideally should serve as a foundational framework for negotiated settlements that ascribe to the international politics some semblance of order.

On a practical level, there is opportunity for governments to approach future cooperation and competition through this lens. In the Indo-Pacific, governments — even those in Europe — seem to be jostling for position. Perhaps there are benefits to be gained by aiming first for a balance of military and economic power, and then toward some structures that might facilitate both dialogue and decisions about major questions in the region. Important, however, is that the powers principally concerned hold as their ultimate objective not outright victory but a negotiated order that can employ an ethical or moral basis that governments deem legitimate in this period.

In this way, we might go some way toward reversing, or at least recalibrating, the understood purpose of a balance of power in foreign policy. Such a view echoes ideas put forward by Hedley Bull, Richard Little, and Michael Sheehan, who have seen in older interpretations some important guides for contemporary policymaking. Sheehan, who has written an excellent historical study of the term “balance of power,” argues that modern understandings should return to its “Grotian form” (named after the Dutch diplomat and jurist Hugo Grotius). Writing in the period of the Thirty Years War (1618 to 1648), Grotius articulated norms and laws which, because societies shared common characteristics and experiences, could be applied to larger international context. It is the same rationale that underpinned the work of later scholars of international law, such as Lassa Oppenheim, who wrote in 1905 that a “law of nations can exist only if there be an equilibrium, a balance of power, between the members of the family of nations.”

Through this understanding of older interpretations, we arrive, too, at a more fundamental aspect of statecraft. Specifically, try as some might, ethical considerations cannot and should not be viewed as separate from or subordinate to considerations of power. At the highest level of policy, these aspects — power and ethics — are fused together in ways that a great deal of modern commentary on international politics obscures. To take one example, when a writer like Eliot Cohen, one of the great thinkers in American foreign policy over the preceding decades, calls in Foreign Affairs for future American statesmen and women to turn away from grand strategy and toward statecraft, we are forced to pause. For not only is grand strategic thinking, properly understood, an essential dimension of statecraft, but at its root is the most fundamental dilemma of politics — how to strike the balance between ethics and power — which Western thinkers (to say nothing of other civilizations) have been grappling with for millennia. And far from a seminar exercise, the question plays out in real time. Looking at the Russo-Ukrainian War, for example, the moral question is a simple one to answer. The political, not so much.

It is this acceptance of the ever relevant, if intractable, dilemma of power and ethics that brings us to a final point: the role of ideas in domestic and international order, and the necessity of strategists, especially those focusing on the longer term, being able to recognize and grapple with the influence and impact of such phenomena. When asked what set George Kennan apart from other distinguished American diplomats of his era, the philosopher Isaiah Berlin remarked of his friend that:

Interest in ideology. Intellectualism of a certain kind. Ideas. Deep interest in, and constant thought, in terms of attitudes, ideas, traditions, what might be called cultural peculiarities of countries and attitudes, forms of life. Not simply move after move; not chess. Not just evidence of this document, that document, showing that what they wanted was northern Bulgaria, or southern Greece. But also mentalités .

If we can accept as a precept the relevance of ideational, as opposed to solely mechanical, thinking in statecraft, we can move toward understanding how ideas themselves have changed over time, and whether, if at all, older interpretations are relevant or applicable to modern realities. “Ideas are nothing but the unremitting thought of man, and transmission for them is nothing less than transformation,” the philosopher Benedetto Croce wrote . In our own time, recognizing the way in which the concept of the balance of power has morphed over centuries allows us to grasp both its complexities and its potential applicability to present and future statecraft.

Andrew Ehrhardt is an Ernest May Fellow in History and Policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School.

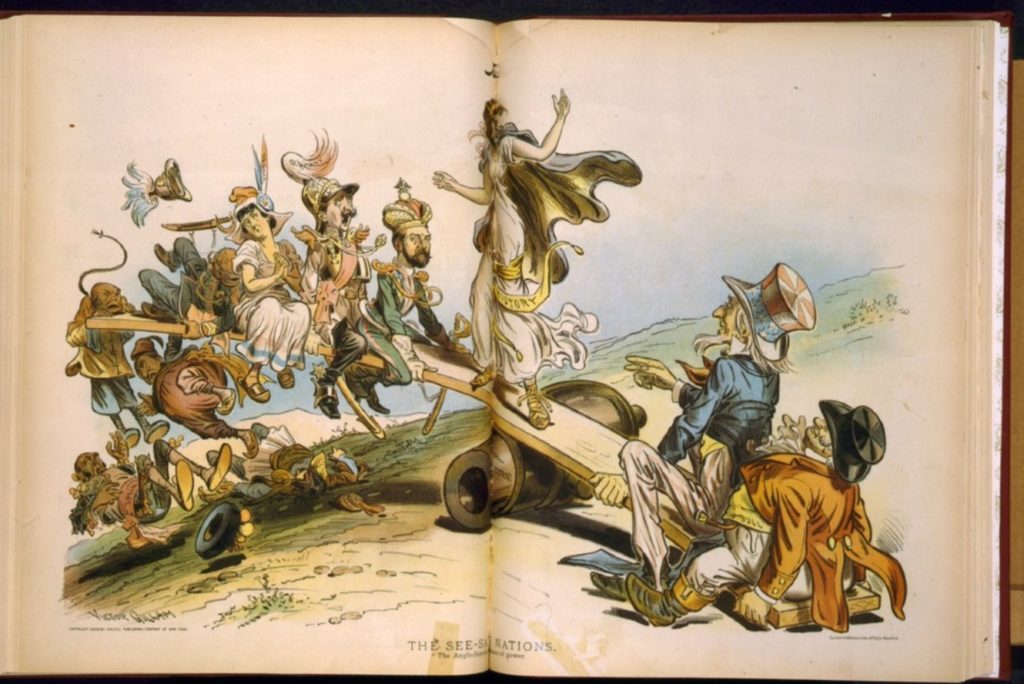

Image: Print by Gillam, F. Victor, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Do Androids Dream of Disorienting Maps?

Horns of a dilemma, south korea’s grand strategy, operationalizing a doctrine for u.s. economic statecraft.

- Free Samples

- Premium Essays

- Editing Services Editing Proofreading Rewriting

- Extra Tools Essay Topic Generator Thesis Generator Citation Generator GPA Calculator Study Guides Donate Paper

- Essay Writing Help

- About Us About Us Testimonials FAQ

Essays on balance of power

- Studentshare

- Balance Of Power

- TERMS & CONDITIONS

- PRIVACY POLICY

- COOKIES POLICY

Balance of Power Theory in Today’s International System

“Balance of power theory grew out of many centuries of multipolarity and a few decades of bipolarity. Today the world is characterized by unprecedented unipolarity. Balance of power theory, therefore, cannot provide guidance for the world we are in.”

In responding to this statement, the essay will first discuss the logical fallacy inherent in its argument: though the balance of power theory (BOP) [1] emerged concurrent to certain types of power configuration in world politics—multipolarity and bipolarity in this case—it does not follow that it was these types of configuration per se that gave rise to the theory itself. Multipolarity and bipolarity can and should be considered, themselves, as manifestations of the underlying logic of the international system, which the BOP theory also embodies. This logic of relative positionality of states in an anarchic system, as this essay will argue, has not fundamentally changed since the emergence of BOP theory. This leads to the second empirical problem with the statement. On the one hand, a de facto unipolarity characterized by American hegemony has been around for much longer than the end of the Cold War. On the other hand, the current economic and political status of China places it in a pseudo-superpower position vis-à-vis the United States. Both of these mean that the degree of unipolarity that we observe today relative to the bipolarity of the Cold War is, if any, weak. Therefore, much of BOP’s relevance in the bipolar world will continue to be in today’s international system.

The BOP Theory: Core Assumptions and the (ir)Relevance of Polarity

We should first understand the logic that gave rise to the BOP theory. Two assumptions are of central relevance. First, the international system is considered to be anarchic, with no system-wide authority being formally enforced on its agents (Waltz 1979, 88). Because of this “self-help” nature of the system, states do not have a world government to resort to in a situation of danger, but they can only try to increase their capabilities relative to one another through either internal efforts of self-strengthening, or external efforts of alignment and realignment with other states (Waltz 1979, 118). Second, states are the principle actors in the international system, as they “set the terms of the intercourse” (Waltz 1979, 96), monopolize the “legitimate use of force” (Waltz 1979, 104) within their territories, and generally conduct foreign policy in a “single voice” (Waltz 1959, 178-179). Hence states are also considered to be unitary actors in the international system. This latter assumption is important because if non-state or transnational actors are powerful enough to challenge state actors, power configuration in the world may no longer be considered in terms of polarity but, instead, in terms of the number of layers of policy “networks” [2] . This essay bases its argument on these two core assumptions about the international system as well because they have been widely accepted not only in realism and neorealism but also in neoliberal institutionalism (Keohane 1984, etc.) and, to some degree, in constructivism (Wendt 1999, etc.) as well. Thus, they are not derivative from exclusively realist or neorealist beliefs such as relative power maximization.

With this in mind, the essay will now discuss why polarity is neither sufficient nor necessary to explain the balance of power. The question of sufficiency can be answered with respect to why balance of power does not always occur even in a multipolar or bipolar world, and that of necessity with respect to why balance of power can still occur even with unipolarity. According to Waltz, balance of power occurs when, given “two coalitions” formed in the international system, secondary states, if free to choose, will side with the weaker, so as to avoid being threatened by the stronger side (Waltz 1979, 127). This condition has led some to question the validity of BOP in a unipolar world, since two or more states need to coexist in the system in order for the theory to hold (Waltz 1979, 118).

However, as this essay mentions, once we accept the two core assumptions (that of anarchy and that of states being principle actors), this condition is not necessary for BOP to be relevant. The balance of power, as Waltz suggests, is a “result” – an outcome variable that reflects the causal effect of the explanatory variables which are, in his theory, anarchy and distribution of power in the international system. This tension within Waltz’s own argument has indeed invited criticism that his version of the BOP theory is essentially attempting to explain one dependent variable (the occurrence of balance of power) with another (polarity) (Lebow, 27). To sidestep this potential loophole, therefore, we need to assess the relevance of BOP by examining whether the same structural constraints that engender balancing in the multipolar or bipolar systems are also present in a unipolar world.

If the balance of power could not be directly deduced from system polarity, what then would predict its occurrence? To answer this question will require us to go back to the two core assumptions and see what explanatory variables can be derived from these assumptions that will have some observable implications with regard to balancing. The likelihood of balance of power is, therefore, a function of these variables which, as this essay will show, boil down to 1) intention , notably the intention or the perceived intention of the major powers in the system, 2) preference of the states, particularly that between absolute and relative gains, and 3) contingency , often related to the availability of new information in a given situation, which may exogenously change the first two variables. Most importantly, none of the three is conditional upon a certain type of polarity to be effectual.

Three Explanatory Variables for Predicting Balancing: Intention, Preference, Contingency

The intention, or the perceived intention of a major power, determines whether balancing will be preferred by secondary states over other options such as bandwagoning. We can think of this in terms both why smaller states sometimes succumb to the sphere of the strongest power in the system and why they sometimes stay away from it, or challenge it by joining the second biggest power if there were one. In his analysis of the conditions for cooperation under the security dilemma, Robert Jervis shows that when there is pervasive offensive advantage and indistinguishability between offense and defense (the “worst case” scenario), security dilemma between states can be so acute that it can virtually squeeze out the “fluidity” necessary for any balance of power to occur (Jervis 1978, 186-189). By incurring incorrect “inferences”, offensive advantage and offense-defense indistinguishability ultimately serve to alter the perceived intention of the adversary as being aggressive or non-aggressive (Jervis 1978, 201). This will then dictate the smaller states’ decision to whether balance the move. If, however, the major power is perceived to have not only a non-aggressive intention, but also a benign intention of providing certain public goods, smaller states may choose to free ride on these benefits while submitting to the major power’s sphere of influence in return; an outcome of so-called “hegemonic stability” may then ensue (Keohane 1984, 12). Thus along the dimension of perceived intention, balance of power occurs when states have reservations about the major power or the hegemon’s intention but not to the extent that a precipitation to war is so imminent as to render balancing infeasible.

Second, balance of power is closely related to the states’ preference for relative versus absolute gains. From an offensive realist point of view, John Mearsheimer contends that states concerned with balance of power must think in terms of relative rather than absolute gain – that is, their military advantage over others regardless of how much capability they each have. The underlying logic here is at once intuitive—given a self-help system and self-interested states, “the greater military advantage one state has…the more secure it is” (Mearsheimer 1994-95, 11-12)—and problematic since the auxiliary assumption that every state would then always prefer to have maximum military power in the system (Mearsheimer 1994-95, 12) is practically meaningless. Similarly, Joseph Grieco points out that with the ever present possibility of war in an anarchic system, states may not cooperate even with their allies because survival is guaranteed only with a “proportionate advantage” (Grieco in Baldwin ed., 127-130). The concern for relative gain predicts that states will prefer balance of power over collective security because the latter requires that states trust one another enough to completely forgo relative gain through unilateral disarmament, which is inherently at odds with the idea of having a positional advantage for self-defense (Mearsheimer 1994-95, 36).

Meanwhile, the neoliberal institutionalist cooperation theory essentially presumes the pursuit of absolute gain over relative gain for states to achieve cooperation (Keohane 1984, 68). On a broader scale, therefore, the pursuit of relative gain would undercut international cooperation in general, in both high and low politics. It is safe to say that in practice, states are concerned with both relative and absolute gains to different degrees under different circumstances. Scholars like Duncan Snidal and Robert Axelrod have rigorously demonstrated the complexity of situations in which these two competing interests dynamically interact and change over time (see for example Snidal in Baldwin ed. and Axelrod 1984, Chapter 2). In general, though, a prevalent preference for relative gains and, more specifically, military positionality among states increases the likelihood of balancing relative to collective security. If states tend to favor absolute gains instead, we are more likely to see phenomena such as deep international institutions and pluralist security communities.

But even if there existed a malign hegemon that other states wanted to balance against, and the states all pursued relative gains, balance of power would still be conditional. That is, even with the aforementioned systemic constraints, balance of power is not a given without knowing the specific contingency factors unique to each situation. One additional implication of an anarchic system is pervasive uncertainty resulting from the scarcity of information, since all states have an incentive to misrepresent in order to further their positionality in event of war (Fearon 1998, 274). This explains why, perhaps in a paradoxical way, historically even in periods of multipolarity and bipolarity characterized by intense suspicion and tension, balancing did not happen as often as BOP would predict. The crux is the unexpected availability of new information which leads to a change in the course of action by altering preexisting beliefs and preferences. The European states’ collective decision to buttress the rising challenger Prussia in the 1800s despite the latter’s clear expansionist tendency shows that neither intention nor preference can be taken as a given, but both are subject to circumstantial construction (Goddard, 119).

In times of crisis, this constructing effect may be especially strong. Such characterized the interwar period and resulted in a significant lag in the European states’ learning which may have otherwise incurred greater balance against the revisionist Germany (Jervis 1978, 184). Still caught up in a spirit of collective security from the first war, these states were too “hot-headed” to switch to the phlegmatic behavior of balancing (Weisiger, lecture). This, however, had less to do with their perception of Germany or their pursuit of relative/absolute gains than with the transformational effect of the trauma of World War I. In short, the more rapid and unpredictable is the flux of information in a given situation, the less likely that the balance of power contingent on existing beliefs and preferences will occur as predicted.

The Fall of USSR, the Rise of China, and Empirical Implications for the BOP Theory

Having shown that BOP has less to do with polarity than with intention of aggression, preference for relative gains, and circumstantial factors in an anarchic world, this essay will now show why our current system, characterized by American hegemony, is not so much different from the preceding ones. Doing so will not only address the necessity question mentioned earlier, but also show that even if we accept the premise that BOP is less applicable to unipolarity than to multipolarity and bipolarity, this hardly affects BOP’s relevance to today’s world.

Though BOP gained much leverage during the Cold War, which is considered a textbook case of bipolarity, a closer look at Waltz’s discussion of American dominance at the time reveals what really resembles a picture of American hegemony rather than bipolarity (Waltz 1979, 146-160). Most important, however, is the fact that concurrent to this widening gap between the U.S. and the USSR, a corresponding increase in the balance of power against the U.S. did not occur. Rather, we saw the opposite happen where Soviet satellite states started drifting away one after another. This greatly undermines BOP’s explanatory power even for bipolarity. Richard Lebow’s succinct summary of the years leading to the Soviet collapse illustrates that not only did the USSR productivity remain vastly inferior to that of the U.S., but also that its military (nuclear) capabilities never reached the level as to be a real challenger to the U.S. Hence, the actual period of strict bipolarity during the Cold War is much shorter than is conventionally believed (Lebow, 28-31). It is debatable as to what extent the Soviet “anomaly” was primarily the result of perception, preference, or contingency (such as that discussed in Risse, 26), but major discordances between the balance of power and polarity lend further support to this essay’s argument that BOP is not determined by polarity itself, but by variables inherent in the international system, which may or may not lead to a concurrence of balance of power and certain types of polarity.

The demarcation between the bipolar Cold War system and the unipolar post-Cold War system is, therefore, fuzzy at best. This has been further complicated by China’s rise in the most recent decades. To put things in perspective: at the peak of the Cold War, the U.S. enjoyed a GDP of $5,200 billion (USD)—about twice of that of the USSR ($2,700 billion). As of last year, it was $16,000—also about twice of that of China’s ($8,200 billion). [3] If we were to measure superpower status by nuclear capability (which many scholars use to pinpoint the start of Cold War), the picture is even more ambiguous, with as many as nine states currently having nuclear weapons, including North Korea. [4]

Rather than questioning American hegemony today, which this paper does not intend to do, these facts simply serve to remind us of the continuity rather than discreteness of the recent stages of polarity. Because of this, the supposed unipolarity as of present has little bearing on the validity of the BOP theory in explaining state behavior. Hans Morgenthau reaffirms the balance of power as a “perennial element” in human history, regardless of the “contemporary conditions” that the international system operates under (Morgenthau, 9-10). The essence of the BOP theory cannot be reduced to the occurrence of balance of power. With the logic of anarchy and principality of state actors largely unchanged, we can, therefore, imagine a situation of balancing against the U.S. even in a unipolar system—if the U.S. is no longer perceived as a benign hegemon and if states are more concerned with their military disadvantage as a result, especially when a combination of situational factors and diplomatic efforts further facilitates such a change in perception and preference.

Axelrod, Robert, The Evolution of Cooperation , 1984.

Fearon, James, “Bargaining, Enforcement, and International Cooperation,” International Organization 52:2, 1998.

Goddard, Stacie, “When Right Makes Might: How Prussia Overturned the European Balance of Power,” International Security 33:3, 2008-2009.

Grieco, Joseph, “Anarchy and the Limits of Cooperation: A Realist Critique of the Newest Liberal Institutionalism” in David Baldwin ed., Neorealism and Neoliberalism: The Contemporary Debate , 1993.

Jervis, Robert, “Cooperation under the Security Dilemma,” World Politics 30:2, 1978.

Keohane, Robert, After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy , 1984.

Lebow, Richard Ned, “The Long Peace, the End of the Cold War, and the Failure of Realism,” in Richard Ned Lebow and Thomas Risse-Kappen eds., International Relations Theory and the End of the Cold War , 1995.

Mearsheimer, John, “The False Promise of International Institutions,” International Security 19:3, 1994-1995.

Morgenthau, Hans, Politics among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace , 1967.

Risse, Thomas, “‘Let’s Argue!’: Communicative Action in World Politics,” International Organization , 54:1, 2000.

Snidal, Duncan, “Relative Gains and the Pattern of International Cooperation” in David Baldwin ed., Neorealism and Neoliberalism: The Contemporary Debate , 1993.

Waltz, Kenneth, Theory of International Politics , 1979.

Waltz, Kenneth, Man, the State, and War: A Theoretical Analysis , 1959.

Wendt, Alexander, Social Theory of International Politics , 1999.

“The World Factbook,” Central Intelligence Agency .

[1] I will use the acronym “BOP” to refer to the theory of balance of power, and “balance of power” to refer to the actual phenomenon of balance of power.

[2] This term is directly borrowed from the title of Networked Politics by Miles Kahler, but numerous works have alluded to the same concept, such as those by Kathryn Sikkink, Martha Finnemore and Anne-Marie Slaughter, to name a few.

[3] The World Factbook , Central Intelligence Agency.

— Written by: Meicen Sun Written at: University of Pennsylvania Written for: Mark Katz Date written: October 2013

Further Reading on E-International Relations

- Have Waltz’s Critics Misunderstood His Theory of International Politics?

- Cosmological Politics: Towards a Planetary Balance of Power for the Anthropocene

- A Rules-Based System? Compliance and Obligation in International Law

- Tracing Hobbes in Realist International Relations Theory

- A Critical Reflection on Sovereignty in International Relations Today

- Is the International System Racist?

Please Consider Donating

Before you download your free e-book, please consider donating to support open access publishing.

E-IR is an independent non-profit publisher run by an all volunteer team. Your donations allow us to invest in new open access titles and pay our bandwidth bills to ensure we keep our existing titles free to view. Any amount, in any currency, is appreciated. Many thanks!

Donations are voluntary and not required to download the e-book - your link to download is below.

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essays Examples >

- Essay Topics

Essays on Balance Of Power

51 samples on this topic

To many college goers, crafting Balance Of Power papers comes easy; others need the help of various types. The WowEssays.com catalog includes professionally crafted sample essays on Balance Of Power and related issues. Most definitely, among all those Balance Of Power essay examples, you will find a piece that get in line with what you perceive as a worthy paper. You can be sure that literally every Balance Of Power work presented here can be used as a bright example to follow in terms of overall structure and writing different chapters of a paper – introduction, main body, or conclusion.

If, however, you have a hard time coming up with a decent Balance Of Power essay or don't have even a minute of extra time to explore our sample directory, our free essay writer service can still be of great assistance to you. The matter is, our writers can craft a model Balance Of Power paper to your individual needs and particular requirements within the pre-set period. Buy college essays today!

The First World War Essay

Labor unions and their efficiency in workplace environment research papers examples.

Introduction

A-Level Essay On Airport Security Since 9/11 For Free Use

Perfect model book review on ajp & wwii, answers to the questions a, b, c: example essay by an expert writer to follow, both models are polar opposite of one another, but it is not solely for adoption of either one. essays examples, expertly written research paper on the power politics in the scs dispute to follow.

The Impact and Effects of Power Politics of United States, China, & Japan Arising from South China Sea Conflicts on the Sovereignty and Socio-Political Fabrics of Philippines

Example Of Essay On The Appropriate Division Of Labor Between External Sponsors And Client States In The Prosecution Of Counterinsurgency

Introduction 2

The Impact of Insurgency Efforts During the Vietnam War 3 External Sponsors of Insurgency Movements 6 Conclusion 10

Works Cited 13

Comparision Between The Utility Of Wallerstein’s World System Theory Focault’s Three Understandings Of Power Essays Example

COMPARISION BETWEEN THE UTILITY OF WALLERSTEIN’S WORLD SYSTEM THEORY AND FOCAULT’S THREE UNDERSTANDINGS OF POWER

The world systems by Immanuel Wallenstein and Michel Foucault’s three understandings of power are some of the most important theories that explain power differences among nations (Polat 2012). Their relevance to international relations is that these schools of thought all endeavor to explain reasons why there is power imbalance among world nations in their trade and political relations with one another. According to the world system’s theory, there is need to have a holistic study of the entire world economy as a system in order to understand how each country fits into the whole world system.

Meaning of Power

Literary Research Paper: The Relationship Between Sexuality And Gender In Sula Research Paper

Treaty of versailles and creation of a discipline essay example, government in the united states essays examples.

Intergovernmental

The United Stated of America is primarily founded on a federal system of government. However, the system does not flow downwards hierarchically in the same mannerism of a unitary system of government. The federal system is meant to condone conflicts within the work place as administrators work within areas where various people share authority.

Politics Essays Example

1. A "Virtue of anarchy" (or a positive effect of the constant threat of the use of force) in the international system according to Kenneth Waltz. (From Anarchic structures and balances of power, mainly Virtues of Anarchy)

Good Course Work About Federalism

Certainly, the federal and state governments pose immense influences on the lives of Americans living across various contexts. As such, there should be a balance of power between these two forms of governments. Worth noting is the fact that the United States constitution dictates that the federal government should exercise authority over the state government in specific areas.

Theories of International Relations Essay Example

How internet changed the world as it known essays examples, free research paper on role of women in ancient times and today, good example of realism theory research paper.

International Relations-The Problem of the Rise of China

Differences Between Classical Realism And Neo-Realism Essays Example

Good example of essay on what are the major differences between classical realism and neo-realism do these.

Classical realism and neo-realism represents the evolution and proliferation of international politics. Even in contemporary times, the political leaders staunchly represent these theories in their practical application of political ideals. This paper is an extensive study of these two forms of realism. It begins by defining realism; then identifies the major differences among these concepts and exemplifies its significance across the world. Finally, a conclusion is drawn by elaborating on contemporary politics and its use/rebuttal of these concepts.

Defining realism

Free The Role Of Diplomacy In Creating And Maintaining Peace Research Paper Example

Good essay about terrorism, free essay on congress of vienna, sample essay on what is the difference between realism and neorealism.

What is the difference between Realism and Neorealism?

The Gulf War Research Papers Example

International Conflict Political Science

Research Paper On Current Distribution Of Power At The Global Level

Free middle east politics essay sample, sample term paper on contextualizing the 1979 sino-vietnamese war, example of term paper on the syrian crisis and the rise of jihadists wave: security implications, the iraq war critical thinking samples, midterm examination essay example, the syrian crisis and the rise of the jihadists wave: security problems term paper sample, free research paper about what do neo-realist explanations of international politics focus on, research paper on ancient vs. modern governments, the rise of china and the security implications to the region argumentative essay sample, cooperative security research paper examples.

Post Cold War

Example Of 7. In What Ways Have Global Environmental Problems Such As Climate Change Challenged Research Paper

Causes of world war i essay examples, free term paper on the balance of power in dating.

Modern relationships always beg the question, who is more superior in the relationship. Traditionally, different sexes had specific roles in a relationship that determined the leader in a relationship (Besen 257). Men took more took more involving roles as being the bread winner and making important decisions in the family. Women settled for simpler and sex defined roles as cooking and taking care of the home and the children. This article explores the changes that have taken place over the years to change the power in dating.

The Trent Affairs Outcome Is Explained By Realism Not Democratic Peace Essay Example

Political realism, liberalism and constructivism are three theories alive in international relations today. However, throughout history, one theory outshines the rest by continuously playing a vital role in world-wide affairs. From on-going wars to daily foreign policy acts, the philosophy of realism is applied more often than not. Realism looks at the uncertainty that exists between nations and how the various conflicts in the world need to be followed accordingly, without trust. This theory can be appropriately applied to events today and many historical conflicts over the centuries.

The American Civil War Essay Examples

The American Civil War

Example Of Article Review On The Beginning Of The Cold War

Essay on war is better than a bargain.

Explain how war can be “Better than a Bargain”. Fromkin and Doyle.

War is a form of conflict that usually arises whenever there is a disagreement between individuals, states or even nations. It results into a hostile relationship, and for example, in armed conflict, mortality rates become high. Furthermore, it impacts negatively on the economy and leads to widespread problems. Sometimes war can be beneficial besides its negative attributes. This is detailed as war being better than a bargain, and it may act as the best option amongst two parties with conflicting needs (Fromkin 8-18).

World History Essay Sample

Example of essay on western civilizations 2.

Discuss the system of alliances that emerged during and after the Congress of Vienna. What were the goals of the Congress of Vienna and was the Congress successful in implementing these goals? Did the system of alliances remain intact a century later?

Special Providence Book Review

Book Review on Walter Russell Mead's, Special Providence: American Foreign Policy and How It Changed the World

275 words = 1 page double-spaced

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!

Check your email! An email with your password has already been sent to you! Now you can download documents directly to your device.

or Use the QR code to Save this Paper to Your Phone

The sample is NOT original!

Short on a deadline?

Don't waste time. Get help with 11% off using code - GETWOWED

No, thanks! I'm fine with missing my deadline

Hume Texts Online

Of the balance of power ..

I T is a question whether the idea of the balance of power be owing entirely to modern policy, or whether the phrase only has been invented in these later ages? It is certain, that Xenophon [1] , in his Institution of Cyrus , represents the combination of the Asiatic powers to have arisen from a jealousy of the encreasing force of the Medes and Persians ; and though that elegant composition should be supposed altogether a romance, this sentiment, ascribed by the author to the eastern princes, is at least a proof of the prevailing notion of ancient times.

In all the politics of Greece , the anxiety, with regard to | the balance of power, is apparent, and is expressly pointed out to us, even by the ancient historians. Thucydides [2] represents the league, which was formed against Athens , and which produced the Peloponnesian war, as entirely owing to this principle. And after the decline of Athens , when the Thebans and Lacedemonians disputed for sovereignty, we find, that the Athenians (as well as many other republics) always threw themselves into the lighter scale, and endeavoured to preserve the balance. They supported Thebes against Sparta , till the great victory gained by Epaminondas at Leuctra ; after which they immediately went over to the conquered, from generosity, as they pretended, but in reality from their jealousy of the conquerors [3] .

Whoever will read Demosthenes 's oration for the Megalopolitans , may see the utmost refinements on this principle, that ever entered into the head of a Venetian or English speculatist. And upon the first rise of the Macedonian power, this orator immediately discovered the danger, sounded the alarm throughout all Greece , and at last assembled that confederacy under the banners of Athens , which fought the great and decisive battle of Chaeronea .

It is true, the Grecian wars are regarded by historians as wars of emulation rather than of politics; and each state seems to have had more in view the honour of leading the rest, than any well-grounded hopes of authority and dominion. If we consider, indeed, the small number of inhabitants in any one republic, compared to the whole, the great difficulty of forming sieges in those times, and the extraordinary bravery and discipline of every freeman among that noble people; we shall conclude, that the balance of power was, of itself, sufficiently secured in Greece , and needed not to have been guarded with that caution which may be requisite in other ages. But whether we ascribe the shifting of sides in all the Grecian republics to jealous emulation or cautious politics , the effects were alike, and every prevailing power was sure to meet with a confederacy against it, and that often composed of its former friends and allies.

The same principle, call it envy or prudence, which produced the Ostracism of Athens , and Petalism of Syracuse , and expelled every citizen whose fame or power overtopped the rest; the same principle, I say, naturally discovered itself in foreign politics, and soon raised enemies to the leading state, however moderate in the exercise of its authority.

The Persian monarch was really, in his force, a petty prince, compared to the Grecian republics; and therefore it behoved him, from views of safety more than from emulation, to interest himself in their quarrels, and to support the weaker side in every contest. This was the advice given by Alcibiades to Tissaphernes [4] , and it prolonged near a century | the date of the Persian empire; till the neglect of it for a moment, after the first appearance of the aspiring genius of Philip , brought that lofty and frail edifice to the ground, with a rapidity of which there are few instances in the history of mankind.

The successors of Alexander showed great jealousy of the balance of power; a jealousy founded on true politics and prudence, and which preserved distinct for several ages the partition made after the death of that famous conqueror. The fortune and ambition of Antigonus [5] threatened them anew with a universal monarchy; but their combination, and their victory at Ipsus saved them. And in subsequent times, we find, that, as the Eastern princes considered the Greeks and Macedonians as the only real military force, with whom they had any intercourse, they kept always a watchful eye over that part of the world. The Ptolemies , in particular, supported first Aratus and the Achaeans , and then Cleomenes king of Sparta , from no other view than as a counterbalance to the Macedonian monarchs. For this is the account which Polybius gives of the Egyptian politics [6] .

The reason, why it is supposed, that the ancients were entirely ignorant of the balance of power , seems to be drawn from the Roman history more than the Grecian ; and as the transactions of the former are generally more familiar to us, we have thence formed all our conclusions. It must be owned, that the Romans never met with any such general combination or confederacy against them, as might naturally have been expected from the rapid conquests and declared ambition; but | were allowed peaceably to subdue their neighbours, one after another, till they extended their dominion over the whole known world. Not to mention the fabulous history of their Italic wars; there was, upon Hannibal 's invasion of the Roman state, a remarkable crisis, which ought to have called up the attention of all civilized nations. It appeared afterwards (nor was it difficult to be observed at the time) [7] that this was a contest for universal empire; yet no prince or state seems to have been in the least alarmed about the event or issue of the quarrel. Philip of Macedon remained neuter, till he saw the victories of Hannibal ; and then most imprudently formed an alliance with the conqueror, upon terms still more imprudent. He stipulated, that he was to assist the Carthaginian state in their conquest of Italy ; after which they engaged to send over forces into Greece , to assist him in subduing the Grecian commonwealths [8] .

The Rhodian and Achaean republics are much celebrated by ancient historians for their wisdom and sound policy; yet both of them assisted the Romans in their wars against Philip and Antiochus . And what may be esteemed still a stronger proof, that this maxim was not generally known in those ages; no ancient author has remarked the imprudence of these measures, nor has even blamed that absurd treaty above-mentioned, made by Philip with the Carthaginians . Princes and statesmen, in all ages, may, before-hand, be blinded in their reasonings with regard to events: But it is somewhat extraordinary, that historians, afterwards, should not form a sounder judgment of them.

Massinissa , Attalus , Prusias , in gratifying their private passions, were, all of them, the instruments of the | Roman greatness; and never seem to have suspected, that they were forging their own chains, while they advanced the conquests of their ally. A simple treaty and agreement between Massinissa and the Carthaginians , so much required by mutual interest, barred the Romans from all entrance into Africa , and preserved liberty to mankind.

The only prince we meet with in the Roman history, who seems to have understood the balance of power, is Hiero king of Syracuse . Though the ally of Rome , he sent assistance to the Carthaginians , during the war of the auxiliaries; “Esteeming it requisite,” says Polybius [9] , “both in order to retain his dominions in Sicily , and to preserve the Roman friendship, that Carthage should be safe; lest by its fall the remaining power should be able, without contrast or opposition, to execute every purpose and undertaking. And here he acted with great wisdom and prudence. For that is never, on any account, to be overlooked; nor ought such a force ever to be thrown into one hand, as to incapacitate the neighbouring states from defending their rights against it.” Here is the aim of modern politics pointed out in express terms.

In short, the maxim of preserving the balance of power is founded so much on common sense and obvious reasoning, that it is impossible it could altogether have escaped antiquity, where we find, in other particulars, so many marks of deep | penetration and discernment. If it was not so generally known and acknowledged as at present, it had, at least, an influence on all the wiser and more experienced princes and politicians. And indeed, even at present, however generally known and acknowledged among speculative reasoners, it has not, in practice, an authority much more extensive among those who govern the world.

After the fall of the Roman empire, the form of government, established by the northern conquerors, incapacitated them, in a great measure, for farther conquests, and long maintained each state in its proper boundaries. But when vassalage and the feudal militia were abolished, mankind were anew alarmed by the danger of universal monarchy, from the union of so many kingdoms and principalities in the person of the emperor Charles . But the power of the house of Austria , founded on extensive but divided dominions, and their riches, derived chiefly from mines of gold and silver, were more likely to decay, of themselves, from internal defects, than to overthrow all the bulwarks raised against them. In less than a century, the force of that violent and haughty race was shattered, their opulence dissipated, their splendor eclipsed. A new power succeeded, more formidable to the liberties of Europe , possessing all the advantages of the former, and labouring under none of its defects; except a share of that spirit of bigotry and persecution, with which the house of Austria was so long, and still is so much infatuated.

In the general wars, maintained against this ambitious power, Great Britain has stood foremost; and she still maintains her station. Beside her advantages of riches and situation, her people are animated with such a national spirit, and are so fully sensible of the blessings of their government, that we may hope their vigour never will languish in so necessary and so just a cause. On the contrary, if we may judge by the past, their passionate ardour seems rather to require some | moderation; and they have oftener erred from a laudable excess than from a blameable deficiency.

In the first place, we seem to have been more possessed with the ancient Greek spirit of jealous emulation, than actuated by the prudent views of modern politics. Our wars with France have been begun with justice, and even, perhaps, from necessity; but have always been too far pushed from obstinacy and passion. The same peace, which was afterwards made at Ryswick in 1697, was offered so early as the year ninety-two; that concluded at Utrecht in 1712 might have been finished on as good conditions at Gertruytenberg in the year eight; and we might have given at Frankfort , in 1743, the same terms, which we were glad to accept of at Aix-la-Chapelle in the year forty-eight. Here then we see, that above half of our wars with France , and all our public debts, are owing more to our own imprudent vehemence, than to the ambition of our neighbours.

In the second place, we are so declared in our opposition to French power, and so alert in defence of our allies, that they always reckon upon our force as upon their own; and expecting to carry on war at our expence, refuse all reasonable terms of accommodation. Habent subjectos, tanquam suos; viles, ut alienos. All the world knows, that the factious vote of the House of Commons, in the beginning of the last parliament, with the professed humour of the nation, made the queen of Hungary inflexible in her terms, and prevented that agreement with Prussia , which would immediately have restored the general tranquillity of Europe .

In the third place, we are such true combatants, that, when once engaged, we lose all concern for ourselves and our posterity, and consider only how we may best annoy the enemy. To mortgage our revenues at so deep a rate, in wars, where we were only accessories, was surely the most fatal delusion, that a nation, which had any pretension to politics and prudence, has ever yet been guilty of. That remedy of funding, if it be a remedy, and not rather a poison, ought, in all reason, to be reserved to the last extremity; and no evil, but the greatest and most urgent, should ever induce us to embrace so dangerous an expedient.

These excesses, to which we have been carried, are prejudicial; and may, perhaps, in time, become still more prejudicial another way, by begetting, as is usual, the opposite extreme, and rendering us totally careless and supine with regard to the fate of Europe . The Athenians , from the most bustling, intriguing, warlike people of Greece , finding their error in thrusting themselves into every quarrel, abandoned all attention to foreign affairs; and in no contest ever took part on either side, except by their flatteries and complaisance to the victor.

Enormous monarchies are, probably, destructive to hu | man nature; in their progress, in their continuance [10] , and even in their downfal, which never can be very distant from their establishment. The military genius, which aggrandized the monarchy, soon leaves the court, the capital, and the center of such a government; while the wars are carried on at a great distance, and interest so small a part of the state. The ancient nobility, whose affections attach them to their sovereign, live all at court; and never will accept of military employments, which would carry them to remote and barbarous frontiers, where they are distant both from their pleasures and their fortune. The arms of the state, must, therefore, be entrusted to mercenary strangers, without zeal, without attachment, without honour; ready on every occasion to turn them against the prince, and join each desperate malcontent, who offers pay and plunder. This is the necessary progress of human affairs: Thus human nature checks itself in its airy elevation: Thus ambition blindly labours for the destruction of the conqueror, of his family, and of every thing near and dear to him. The Bourbons , trusting to the support of their brave, faithful, and affectionate nobility, would push their advantage, without reserve or limitation. These, while fired with glory and emulation, can bear the fatigues and dangers of war; but never would submit to languish in the garrisons of Hungary or Lithuania , forgot at court, and sacrificed to the intrigues of every minion or mistress, who approaches the prince. The troops are filled with Cravates and Tartars , Hussars and Cossacs ; intermingled, perhaps, with a few soldiers of fortune from the better provinces: And the melancholy fate of the Roman emperors, from the same cause, is renewed over and over again, till the final dissolution of the monarchy.

Xenoph. Hist. Graec. lib. vi. & vii.

Thucyd. lib. viii.

Diod. Sic. lib. xx.

Lib. ii. cap. 51.

It was observed by some, as appears by the speech of Agelaus of Naupactum , in the general congress of Greece . See Polyb. lib. v. cap. 104.

Titi Livii , lib. xxiii. cap. 33.

Lib. i. cap. 83.

If the Roman empire was of advantage, it could only proceed from this, that mankind were generally in a very disorderly, uncivilized condition, before its establishment.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

NPR defends its journalism after senior editor says it has lost the public's trust

David Folkenflik

NPR is defending its journalism and integrity after a senior editor wrote an essay accusing it of losing the public's trust. Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

NPR is defending its journalism and integrity after a senior editor wrote an essay accusing it of losing the public's trust.

NPR's top news executive defended its journalism and its commitment to reflecting a diverse array of views on Tuesday after a senior NPR editor wrote a broad critique of how the network has covered some of the most important stories of the age.

"An open-minded spirit no longer exists within NPR, and now, predictably, we don't have an audience that reflects America," writes Uri Berliner.

A strategic emphasis on diversity and inclusion on the basis of race, ethnicity and sexual orientation, promoted by NPR's former CEO, John Lansing, has fed "the absence of viewpoint diversity," Berliner writes.

NPR's chief news executive, Edith Chapin, wrote in a memo to staff Tuesday afternoon that she and the news leadership team strongly reject Berliner's assessment.

"We're proud to stand behind the exceptional work that our desks and shows do to cover a wide range of challenging stories," she wrote. "We believe that inclusion — among our staff, with our sourcing, and in our overall coverage — is critical to telling the nuanced stories of this country and our world."

NPR names tech executive Katherine Maher to lead in turbulent era

She added, "None of our work is above scrutiny or critique. We must have vigorous discussions in the newsroom about how we serve the public as a whole."

A spokesperson for NPR said Chapin, who also serves as the network's chief content officer, would have no further comment.

Praised by NPR's critics

Berliner is a senior editor on NPR's Business Desk. (Disclosure: I, too, am part of the Business Desk, and Berliner has edited many of my past stories. He did not see any version of this article or participate in its preparation before it was posted publicly.)

Berliner's essay , titled "I've Been at NPR for 25 years. Here's How We Lost America's Trust," was published by The Free Press, a website that has welcomed journalists who have concluded that mainstream news outlets have become reflexively liberal.

Berliner writes that as a Subaru-driving, Sarah Lawrence College graduate who "was raised by a lesbian peace activist mother ," he fits the mold of a loyal NPR fan.

Yet Berliner says NPR's news coverage has fallen short on some of the most controversial stories of recent years, from the question of whether former President Donald Trump colluded with Russia in the 2016 election, to the origins of the virus that causes COVID-19, to the significance and provenance of emails leaked from a laptop owned by Hunter Biden weeks before the 2020 election. In addition, he blasted NPR's coverage of the Israel-Hamas conflict.

On each of these stories, Berliner asserts, NPR has suffered from groupthink due to too little diversity of viewpoints in the newsroom.

The essay ricocheted Tuesday around conservative media , with some labeling Berliner a whistleblower . Others picked it up on social media, including Elon Musk, who has lambasted NPR for leaving his social media site, X. (Musk emailed another NPR reporter a link to Berliner's article with a gibe that the reporter was a "quisling" — a World War II reference to someone who collaborates with the enemy.)

When asked for further comment late Tuesday, Berliner declined, saying the essay spoke for itself.

The arguments he raises — and counters — have percolated across U.S. newsrooms in recent years. The #MeToo sexual harassment scandals of 2016 and 2017 forced newsrooms to listen to and heed more junior colleagues. The social justice movement prompted by the killing of George Floyd in 2020 inspired a reckoning in many places. Newsroom leaders often appeared to stand on shaky ground.

Leaders at many newsrooms, including top editors at The New York Times and the Los Angeles Times , lost their jobs. Legendary Washington Post Executive Editor Martin Baron wrote in his memoir that he feared his bonds with the staff were "frayed beyond repair," especially over the degree of self-expression his journalists expected to exert on social media, before he decided to step down in early 2021.

Since then, Baron and others — including leaders of some of these newsrooms — have suggested that the pendulum has swung too far.

Author Interviews

Legendary editor marty baron describes his 'collision of power' with trump and bezos.

New York Times publisher A.G. Sulzberger warned last year against journalists embracing a stance of what he calls "one-side-ism": "where journalists are demonstrating that they're on the side of the righteous."

"I really think that that can create blind spots and echo chambers," he said.

Internal arguments at The Times over the strength of its reporting on accusations that Hamas engaged in sexual assaults as part of a strategy for its Oct. 7 attack on Israel erupted publicly . The paper conducted an investigation to determine the source of a leak over a planned episode of the paper's podcast The Daily on the subject, which months later has not been released. The newsroom guild accused the paper of "targeted interrogation" of journalists of Middle Eastern descent.

Heated pushback in NPR's newsroom

Given Berliner's account of private conversations, several NPR journalists question whether they can now trust him with unguarded assessments about stories in real time. Others express frustration that he had not sought out comment in advance of publication. Berliner acknowledged to me that for this story, he did not seek NPR's approval to publish the piece, nor did he give the network advance notice.

Some of Berliner's NPR colleagues are responding heatedly. Fernando Alfonso, a senior supervising editor for digital news, wrote that he wholeheartedly rejected Berliner's critique of the coverage of the Israel-Hamas conflict, for which NPR's journalists, like their peers, periodically put themselves at risk.

Alfonso also took issue with Berliner's concern over the focus on diversity at NPR.

"As a person of color who has often worked in newsrooms with little to no people who look like me, the efforts NPR has made to diversify its workforce and its sources are unique and appropriate given the news industry's long-standing lack of diversity," Alfonso says. "These efforts should be celebrated and not denigrated as Uri has done."

After this story was first published, Berliner contested Alfonso's characterization, saying his criticism of NPR is about the lack of diversity of viewpoints, not its diversity itself.

"I never criticized NPR's priority of achieving a more diverse workforce in terms of race, ethnicity and sexual orientation. I have not 'denigrated' NPR's newsroom diversity goals," Berliner said. "That's wrong."

Questions of diversity

Under former CEO John Lansing, NPR made increasing diversity, both of its staff and its audience, its "North Star" mission. Berliner says in the essay that NPR failed to consider broader diversity of viewpoint, noting, "In D.C., where NPR is headquartered and many of us live, I found 87 registered Democrats working in editorial positions and zero Republicans."

Berliner cited audience estimates that suggested a concurrent falloff in listening by Republicans. (The number of people listening to NPR broadcasts and terrestrial radio broadly has declined since the start of the pandemic.)

Former NPR vice president for news and ombudsman Jeffrey Dvorkin tweeted , "I know Uri. He's not wrong."

Others questioned Berliner's logic. "This probably gets causality somewhat backward," tweeted Semafor Washington editor Jordan Weissmann . "I'd guess that a lot of NPR listeners who voted for [Mitt] Romney have changed how they identify politically."

Similarly, Nieman Lab founder Joshua Benton suggested the rise of Trump alienated many NPR-appreciating Republicans from the GOP.

In recent years, NPR has greatly enhanced the percentage of people of color in its workforce and its executive ranks. Four out of 10 staffers are people of color; nearly half of NPR's leadership team identifies as Black, Asian or Latino.

"The philosophy is: Do you want to serve all of America and make sure it sounds like all of America, or not?" Lansing, who stepped down last month, says in response to Berliner's piece. "I'd welcome the argument against that."

"On radio, we were really lagging in our representation of an audience that makes us look like what America looks like today," Lansing says. The U.S. looks and sounds a lot different than it did in 1971, when NPR's first show was broadcast, Lansing says.

A network spokesperson says new NPR CEO Katherine Maher supports Chapin and her response to Berliner's critique.

The spokesperson says that Maher "believes that it's a healthy thing for a public service newsroom to engage in rigorous consideration of the needs of our audiences, including where we serve our mission well and where we can serve it better."

Disclosure: This story was reported and written by NPR Media Correspondent David Folkenflik and edited by Deputy Business Editor Emily Kopp and Managing Editor Gerry Holmes. Under NPR's protocol for reporting on itself, no NPR corporate official or news executive reviewed this story before it was posted publicly.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

the appropriate balance of power between the president and Congress. • Examples that do not earn this point: Restate the prompt • "The power of the executive and legislative branches of government are important because there is a balance of power." Do not respond to the prompt •

World at War: Essay and Discussion Questions Explain 1. When thinking about balance of power, what factors should be considered when assessing a country's strength? 2. How and why did World War I shape women's roles in society? 3. How was a leader as radical as Adolf Hitler able to rise to power in Germany? 4.