Essay About Consumerism: Top 5 Examples Plus Prompts

Consumerism is the child of capitalism; Here is a list of essay about consumerism examples and prompts you can read to further your understanding.

The word consumerism can seem daunting to some, but it’s pretty simple. It is defined as “a preoccupation with and an inclination toward the buying of consumer goods.” In the consumerist theory, people’s spending on goods and services drives economic growth- their spending preferences and habits determine the direction a company will go next.

Many businesses practice consumerism. It is a common belief that you must adopt a consumerist approach to succeed in your trade. Consumerism refers to people’s prioritization of spending on goods and services. They have the drive to purchase more items continuously.

If you are writing an essay about consumerism, you can get started by reading these essay examples.

1. What You Need To Know About Consumerism by Mark Scott

2. long essay on consumerism by prasanna, 3. consumerism: want and new pair shoes by tony richardson, 4. my thoughts on being a blogger & consumerism by anna newton, 5. consumerism and its discontents by tori deagelis, 1. does consumerism affect your decisions , 2. opposing consumerism, 3. how does consumerism negatively affect mental health, 4. how does consumerism positively affect mental health, 5. do you agree with consumerism.

“Although consumerism drives economic growth and boosts innovation, it comes with a fair share of problems ranging from environmental and moral degradation to higher debt levels and mental health problems..”

Scott gives readers an overview of consumerism in economic and social terms. He then briefly discusses consumerism’s history, benefits, and disadvantages driving economic growth and innovation. It also raises debt, harms the environment, and shifts society’s values toward worldly possessions rather than other people. Scott believes it is perhaps most healthy to find a balance between love for others and material things.

“Consumerism helps the consumers to seek redressal for their grievances against the unfair policies of the companies. It teaches the consumers about their rights and duties and helps them get better quality of products and services.”

In this essay, author Prasanna writes about the history of consumerism and its applications in India. First, it helps protect consumers from companies’ “unethical marketing practices.” For example, she cites policies put in place by the government to inspect food items, ensuring they are of good quality and prepared per sanitation standards. When used appropriately, consumerism serves the benefit of all.

“Anything people see they buy without thinking twice and knowing that they already have brand new pair shoes they have not worn because there to focused on buying and buying till they see they no longer have space in their closet to put new shoes in.”

Richardson takes a personal approach to consumerism, recalling several of his friends’ hobbies of collecting expensive shoes. Advertisements and the pressure to conform play a big role in their consumerism, enticing them to buy more and more items. Richardson believes that consumerism blinds people to the fact that their standards and desires just keep increasing and that they buy shoes for unjustified reasons. Instead, society should be more responsible and remind itself that it needs to take importance above all.

“Take online creators out of the way for a minute, because the pressure to buy is everywhere and has been since the dawn of the dime. The floorplan of stores are set out in a way that makes you stomp around the whole thing and ultimately purchase more, ads on the TV, radio, billboards, in magazines discounts and promotions – it’s endless..”

In her blog The Anna Edit , Newton explains the relationship between blogging and consumerism. Bloggers and influencers may need to purchase more things, not only for self-enjoyment but to produce new content. However, she feels this lifestyle is unsustainable and needs to be moderated. Her attitude is to balance success with her stability and well-being by limiting the number of things she buys and putting less value on material possessions.

“In a 2002 paper in the Journal of Consumer Research (Vol. 29, No. 3), the team first gauged people’s levels of stress, materialistic values and prosocial values in the domains of family, religion and community–in keeping with the theory of psychologist Shalom Schwartz, PhD, that some values unavoidably conflict with one another. ”

DeAngelis first states that it is widely believed that more desire for material wealth likely leads to more discontent: it prioritizes material things over quality time, self-reflection, and relationships. Increasing one’s wealth can help solve this problem, but it is only a short-term fix. However, a 2002 study revealed that the life satisfaction of more materialistic and less materialistic people is not different.

Prompts on Essay about Consumerism

This is not something people think about daily, but it impacts many of us. In this essay, write about how you are influenced by the pressure to buy items you don’t need. Discuss advertising and whether you feel influenced to purchase more from a convincing advertisement. Use statistics and interview data to support your opinions for an engaging argumentative essay.

Consumerism has been criticized by economists , academics , and environmental advocates alike. First, research the disadvantages of consumerism and write your essay about why there has been a recent surge of its critics. Then, conduct a critical analysis of the data in your research, and create a compelling analytical essay.

Consumerism is believed to impact mental health negatively. Research these effects and write about how consumerism affects a person’s mental health. Be sure to support your ideas with ample evidence, including interviews, research data such as statistics, and scientific research papers.

Consumerism often gets a bad reputation. For an interesting argumentative essay, take the opposite stance and argue how consumerism can positively impact mental health. Take a look at the arguments from both sides and research the potential positive effects of consumerism. Perhaps you can look into endorphins from purchases, happiness in owning items, or even the rush of owning a unique item.

In this essay, take your stance. Choose a side of the argument – does consumerism help or hinder human life? Use research to support both sides of the argument and pitch your stance. You can argue your case through key research and create an exciting argumentative essay.

For help with this topic, read our guide explaining what is persuasive writing ?

If you are interested in learning more, check out our essay writing tips !

Martin is an avid writer specializing in editing and proofreading. He also enjoys literary analysis and writing about food and travel.

View all posts

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/69549864/GettyImages_3228051t.0.jpg)

Filed under:

Why do we buy what we buy?

A sociologist on why people buy too many things.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Why do we buy what we buy?

What’s at the root of modern American consumerism? It might not just be competition among the brands trying to sell us things, but also competition among ourselves.

An easy story to tell is that marketers and advertisers have perfected tactics to convince us to purchase things, some we need, some we don’t. And it’s an important part of the country’s capitalistic, growth-centered economy: The more people spend, the logic goes, the better it is for everybody. (Never mind that they’re sometimes spending money they don’t have, or the implications of all this production and trash for the planet.) People, naturally, want things.

But American consumerism is also built on societal factors that are often overlooked. We have a social impetus to “keep up with the Joneses,” whoever our own version of the Joneses is. And in an increasingly unequal society, the Joneses at the very top are doing a lot of the consuming, while the people at the bottom struggle to keep up or, ultimately, are left fighting for scraps.

I recently spoke with Juliet Schor, a sociologist at Boston College, about the history of modern American consumerism — what it’s rooted in, how it’s evolved, and how different groups of people have experienced it. Schor, who is the author of books on consumerism, wealth, and spending, has a bit of a unique view on the matter. She tends to focus on the roles of work, inequality, and social pressures in determining what people buy and when. In her view, marketers have less to do with what we want than, say, our neighbors, coworkers, or the people we follow on social media.

Our conversation, edited for length and clarity, is below.

When I think of the beginning of what I perceive as modern American consumerism, I tend to go back to the 1950s and post-World War II, people moving to the suburbs in the cookie-cutter homes. But is that the right place to start?

Scholars differ on how to date consumerism. I would say we need to go back a bit earlier to the 1920s, which is when you get the development of mass production, which is what makes mass consumption possible. This perspective differentiates the 20th century from the earlier period, in which you have shopping and you have consumer fads. But what changes beginning in the 1920s is that the production technologies make it possible to produce things cheaply enough that eventually you can get a majority of the population consuming them.

All-Consuming

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22694038/GettyImages_162761880.jpg)

The acquisition of stuff looms large in the American imagination. What is life under consumerism doing to us?

Read more from The Goods’ series .

In addition to the things that are happening in factories, the automobile is the leading industry where you move from stationary production to a moving assembly line and big declines in costs. You also have the beginnings of the modern advertising industry and the beginnings of consumer credit.

Then it stalls out, of course, because of the Depression and the war. What happens in the 1950s is the model gets picked up again, this time with major participation by the federal government to spur housing, road building, the auto industry, education, and income. We get into durable goods and household appliances. As we know, that’s really confined to white people post-war.

I imagine it’s changed across the decades, but why do we buy things, often more than we need?

Scholars have different answers to this question. Economists just assume that goods and services provide well-being, and people want to maximize their well-being. Psychologists root it in universal dimensions of human nature, which some of them tie back to evolutionary dynamics. I don’t think either of those are particularly convincing.

The key impetus for contemporary consumer society has been the growth of inequality, the existence of unequal social structures, and the role that consumption came to play in establishing people’s position in that unequal hierarchy. For many people, it’s about consuming to their social position, and trying to keep up with their social position.

It’s not necessarily experienced by people in that way — it’s experienced more as identity or natural desire. But I think our social and cultural context naturalizes that desire for us.

If you think about the particular things people want, it mostly has to do with being the kind of person that they think they are because there’s a consumption style connected with that. The role of what are called reference groups — the people we compare ourselves to, the people we identify with — is really key in that. It’s why, for example, I’ve found that people who have reference groups that are wealthier than they are tend to save less and spend more, and people who keep more modest reference groups, even as they gain in income and wealth, tend to save more.

Increases in inequality trigger what I’ve called “ competitive consumption ,” [the idea that we spend because we’re comparing ourselves with our peers and what they’re spending]. It can be hard to keep up, particularly if standards are escalating rapidly, as we’ve seen.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22694376/GettyImages_565996007.jpg)

I want to dig into this idea of competitive consumption. How are we competing with each other to consume?

We have a society which is structured so that social esteem or value is connected to what we can consume. And so the inability to consume affects the kind of social value that we have. Money displayed in terms of consumer goods just becomes a measure of worth, and that’s really important to people.

How do we pick our “reference groups” if it’s not necessarily by wealth?

We don’t know too much about it. The argument that I made in [my book] The Overspent American was that in the postwar period, we had residentially-based reference groups. So it was really your neighborhood. People moved to the suburbs, and they interacted with people in the suburbs. Those were reference groups of people of similar economic standing because housing is the biggest thing that people buy, and houses tend to cost the same amount roughly within a neighborhood. Family and friends and social networks have always been really important.

Then the next big thing that happens is that you get more and more married women going into the workforce. That really changes reference groups, because they go from a flat social structure in the suburbs to a hierarchy in the workplace, particularly if you’re talking about better-remunerated work and white-collar work. People interact with people above and below them in the hierarchy. So people were exposed to the lifestyles of the people above them in the informal socialization that goes on in the workplace.

Then there is the impact of media, and increasingly now, social media. It’s the friends that you don’t actually know, the Friends on TV.

The reference groups change under different socioeconomic dynamics, but it mostly has to do with who you’re in contact with — what you’re seeing in front of you, so your neighbors, your coworkers, what you’re seeing on TV, in movies, on social media.

I think the key point here that differentiates this approach from that of many people who think about consumption is that it is not saying that it’s primarily driven by advertising. It’s not a process of creating desire where it didn’t exist. Critics of advertising say it’s just making people want stuff they don’t need and doesn’t have value to them. And you have to think, “Okay, why do they keep doing that? Why do they keep falling for the advertisements?” Many of the things that people desperately want are not particularly advertised. My approach is rooted in really deep social logic.

It can be very rational and compelling for people to do something that in the end doesn’t necessarily make them all that better off but that failing to do requires really a major effort and going against the social grain in a very big way.

People aren’t buying a house because they saw a commercial for it.

Exactly. It’s because their sibling got one and their best friend got one. Everybody they know is getting a house, and then they think, “Okay, am I just going to be a renter?”

How has the role of women evolved in consumerism? Women are often driving what to buy, right?

Men still dominate in certain kinds of purchases, and particularly the big ones. Women were responsible for everyday purchasing: food and apparel and things like that. There’s that old binary that “men produce, women consume,” which comes out of the differences in roles we have in our economy to a certain extent.

It’s fascinating, though, because I did some work trying to estimate models of differences between men and women and various kinds of consumption, and I never found any gender differences. But if you are looking at data from marketers, you see a disproportionate amount of spending done by women.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22694272/GettyImages_1298991403.jpg)

What about Black Americans? You alluded to this earlier, but they were at least left out of the ’50s version of consumerism.

The literature on Black Americans’ consumption is not large. If you look at it as a whole, you get a couple of things.

The biggest takeaway is that Black consumers are not that different from white consumers. Now, they do spend on different things, but it’s not like there are two types of consumers, whites and Blacks, and they have different orientations and dynamics. You have differences that are occasioned by some of the dynamics of structural racism — for example, the lower rates of Black homeownership. You’ve got some particular things that you see in part due to the high urban population. Urban dwellers spend more on shoes because they walk a lot more.

You have dynamics among Black consumers that are driven in part by racism. So, for example, sartorial choices in which middle-class and upper-middle-class Black people will have to spend more on their wardrobes in order to avoid being stigmatized in retail settings, the so-called “shopping while Black phenomenon.” Cassi Pittman Claytor, a sociologist at Case Reserve Western University, wrote a wonderful dissertation [ now a book ] on middle-class and upper-class Black people in New York City, and one chapter is on the shopping while Black question. Some of the consumption choices are driven by the attempts to manage racism and stigma in the workplace and outside of it.

Another important phenomenon around the racial discourse in consumption goes back to the period of enslavement of Black Americans in which consumption was a prohibited activity. You see the linkages from the period of enslavement where you’ve got white moralistic discourses against consumption [by] African Americans. A lot of this is in the context of poverty and poor Black people, and the illegitimacy of their consumption choices. And that’s still present today. It’s a really pernicious line of discourse back to enslavement and the ways in which whites attempted to control consumption [by] enslaved people.

What about anti-consumerism? How has that evolved, the people who try to reject consumerism?

There’s a long history of consumer rejectors. You have it in the 19th century as well, and often these were religious groups or sects of people who went into intentional communities, like the Shakers.

Sign up for the Vox Culture newslett er

Each week we’ll send you the very best from the Vox Culture team, plus a special internet culture edition by Rebecca Jennings on Wednesdays. Sign up here .

To me what’s interesting about anti-consumerist movements of the current period is that there’s a certain kind of mainstreaming going on of them. They’re growing. My work is focused on the connections between work choices and consumer choices. So with downshifters, these are people who made decisions to work less and consume less, and it was often the decisions around work that were driving them. Many of them were not people who wanted to consume less in and of itself, but they wanted to take control of their time. And they were willing to make that trade-off.

You do have this minimalist movement now where the stuff is first, though it has a whole story around not getting tied to a burnout job. It’s connected with financial independence and this big “FIRE” movement — financial independence, retire early — and that’s really mainstream. It has much less of a countercultural aspect of it.

You’ve got people coming from the ecological side of things, like buy-nothing groups, and some of these are really big now. They have an ethic of anti-consumerism.

What we’re not sure about is how much participating in one of these actually reduces people’s consumption of new items. But people who participate in buy-nothing groups, most of them don’t buy nothing.

Has the conversation around consumerism and the environment picked up? Should we be talking about consumerism more in the context of saving the planet?

I think we should, and there are two parts to it. One is consuming differently, and the other is not consuming as much. So, volume and composition. To meet climate targets, we need to do both.

There are also issues of inequality of consumption. Look at the inequalities of income and wealth, which have led to these really gross disparities — the excess consumption of people at the top and the deprivation of huge numbers of people both domestically and abroad. It’s not just the bottom, it’s a big swath of the population that doesn’t have enough. So the distribution of consumption is really key, and a lot of the discourse around climate ignored that for a long time. The Green New Deal really put it at the center — it doesn’t lead with a critique of consumerism by any means, but it’s about meeting people’s needs and equity. It has a lot of implications about how we live.

The climate situation does compel us to look differently. In Plenitude: The New Economics of True Wealth , a book I wrote which is now 10 years old, one of the things I looked at was the volume of consumption of consumer goods over the decade before the crash [ahead of the Great Recession]. There was a massive speedup in what I call the cycle of acquisition and discard, just the volume of things people were buying. The fast fashion model that we saw in apparel happened in all sorts of other items, too.

The crash led to a hangover in which you haven’t seen that acceleration again, but it was just a period that showed how dysfunctional the consumer system has become.

Did the Great Recession change how we’re behaving and what we’re buying?

It really slowed down that cycle of acquisition and discard. From 1991 to 2007, the number of pieces of apparel people were buying, on average, went from 34 pieces of new apparel a year to 67. That number hasn’t really budged in the last 10 years.

We haven’t had a massive discontinuity in how the consumption system is operating, but people had less money. And that’s part of the rejecter dynamic — when it’s more difficult for people to participate in that system, either because of its growing cost or their own incomes stagnating, they are likelier to reject it.

It will be interesting to see whether there are any wider impacts of Covid and the fact that people lived with not much more than basic necessities for a while. My own view is that the work patterns are really key in driving consumption. The standard economic view is that it’s the consumer decisions and desires that drive work patterns, and I don’t think that’s the way it works. I think that work patterns actually end up driving consumption.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22702320/GettyImages_1212445377t.jpg)

People make decisions about work, and the hours of work and the incomes associated with them are fixed with the decision. In general, if I decide to take my job as a professor, it has a salary that goes with it, and then that’s what drives my consumption decisions because it drives my income.

If I can’t work this hard anymore, I’m going to go part-time and my income gets cut in half, then I have to adjust my consumption. And that’s not to say it doesn’t go in the other direction — if I want to buy a house, I am going to work some more. But this is my analysis of how the work and spending sides fit together, which is that the work side is a little more dominant.

So we are entering a moment where lots of people have been sitting at home for a year and a half, and as you said, there’s a lot of pent-up demand. Plenty of people I know are ready to spend. Is it odd that we’re responding to the end of a crisis by spending money?

We’re just talking about the people who have it. One of the things about the pandemic is that it made the inequalities in income and spending power more visible to many Americans.

You had so many people who just were struggling through the pandemic to meet basic needs. If you think of that as a working-class phenomenon, you also had this middle-class phenomenon of people whose salaries continued. They were stuck in their houses, so the money was coming into their bank accounts every month and they didn’t have much to spend it on at all. There are people with considerable disposable income right now. We’re going to see a burst of spending now, and we’ll see how long it lasts.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

At Vox, we believe that clarity is power, and that power shouldn’t only be available to those who can afford to pay. That’s why we keep our work free. Millions rely on Vox’s clear, high-quality journalism to understand the forces shaping today’s world. Support our mission and help keep Vox free for all by making a financial contribution to Vox today.

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Trump has set up a perfect avenue for potential corruption

How did the cost of food delivery get so high, the safety net program trapping people in poverty, sign up for the newsletter today, explained, thanks for signing up.

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

A Brief History of Consumer Culture

The notion of human beings as consumers first took shape before World War I, but became commonplace in America in the 1920s. Consumption is now frequently seen as our principal role in the world.

People, of course, have always “consumed” the necessities of life — food, shelter, clothing — and have always had to work to get them or have others work for them, but there was little economic motive for increased consumption among the mass of people before the 20th century.

Quite the reverse: Frugality and thrift were more appropriate to situations where survival rations were not guaranteed. Attempts to promote new fashions, harness the “propulsive power of envy,” and boost sales multiplied in Britain in the late 18th century. Here began the “slow unleashing of the acquisitive instincts,” write historians Neil McKendrick, John Brewer, and J.H. Plumb in their influential book on the commercialization of 18th-century England, when the pursuit of opulence and display first extended beyond the very rich.

But, while poorer people might have acquired a very few useful household items — a skillet, perhaps, or an iron pot — the sumptuous clothing, furniture, and pottery of the era were still confined to a very small population. In late 19th-century Britain a variety of foods became accessible to the average person, who would previously have lived on bread and potatoes — consumption beyond mere subsistence. This improvement in food variety did not extend durable items to the mass of people, however. The proliferating shops and department stores of that period served only a restricted population of urban middle-class people in Europe, but the display of tempting products in shops in daily public view was greatly extended — and display was a key element in the fostering of fashion and envy.

Although the period after World War II is often identified as the beginning of the immense eruption of consumption across the industrialized world, the historian William Leach locates its roots in the United States around the turn of the century.

In the United States, existing shops were rapidly extended through the 1890s, mail-order shopping surged, and the new century saw massive multistory department stores covering millions of acres of selling space. Retailing was already passing decisively from small shopkeepers to corporate giants who had access to investment bankers and drew on assembly-line production of commodities, powered by fossil fuels; the traditional objective of making products for their self-evident usefulness was displaced by the goal of profit and the need for a machinery of enticement.

“The cardinal features of this culture were acquisition and consumption as the means of achieving happiness; the cult of the new; the democratization of desire; and money value as the predominant measure of all value in society,” Leach writes in his 1993 book “ Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a New American Culture .” Significantly, it was individual desire that was democratized, rather than wealth or political and economic power.

The 1920s: “The New Economic Gospel of Consumption”

Release from the perils of famine and premature starvation was in place for most people in the industrialized world soon after the Great War ended. U.S. production was more than 12 times greater in 1920 than in 1860, while the population over the same period had increased by only a factor of three, suggesting just how much additional wealth was theoretically available. The labor struggles of the 19th century had, without jeopardizing the burgeoning productivity, gradually eroded the seven-day week of 14- and 16-hour days that was worked at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in England. In the United States in particular, economic growth had succeeded in providing basic security to the great majority of an entire population.

It would be feasible to reduce hours of work and release workers for the pleasurable activities of free time with families and communities, but business did not support such a trajectory.

In these circumstances, there was a social choice to be made. A steady-state economy capable of meeting the basic needs of all, foreshadowed by philosopher and political economist John Stuart Mill as the stationary state , seemed well within reach and, in Mill’s words, likely to be an improvement on “the trampling, crushing, elbowing and treading on each other’s heels … the disagreeable symptoms of one of the phases of industrial progress.” It would be feasible to reduce hours of work further and release workers for the spiritual and pleasurable activities of free time with families and communities, and creative or educational pursuits. But business did not support such a trajectory, and it was not until the Great Depression that hours were reduced, in response to overwhelming levels of unemployment.

In 1930 the U.S. cereal manufacturer Kellogg adopted a six-hour shift to help accommodate unemployed workers, and other forms of work-sharing became more widespread. Although the shorter workweek appealed to Kellogg’s workers, the company, after reverting to longer hours during World War II, was reluctant to renew the six-hour shift in 1945. Workers voted for it by three-to-one in both 1945 and 1946, suggesting that, at the time, they still found life in their communities more attractive than consumer goods. This was particularly true of women. Kellogg, however, gradually overcame the resistance of its workers and whittled away at the short shifts until the last of them were abolished in 1985.

Even if a shorter working day became an acceptable strategy during the Great Depression, the economic system’s orientation toward profit and its bias toward growth made such a trajectory unpalatable to most captains of industry and the economists who theorized their successes. If profit and growth were lagging, the system needed new impetus. The short depression of 1921–1922 led businessmen and economists in the United States to fear that the immense productive powers created over the previous century had grown sufficiently to meet the basic needs of the entire population and had probably triggered a permanent crisis of overproduction; prospects for further economic expansion were thought to look bleak.

The historian Benjamin Hunnicutt, who examined the mainstream press of the 1920s, along with the publications of corporations, business organizations, and government inquiries, found extensive evidence that such fears were widespread in business circles during the 1920s. Victor Cutter, president of the United Fruit Company, exemplified the concern when he wrote in 1927 that the greatest economic problem of the day was the lack of “consuming power” in relation to the prodigious powers of production.

“Unless [the consumer] could be persuaded to buy and buy lavishly, the whole stream of six-cylinder cars, super heterodynes, cigarettes, rouge compacts and electric ice boxes would be dammed up at its outlets.”

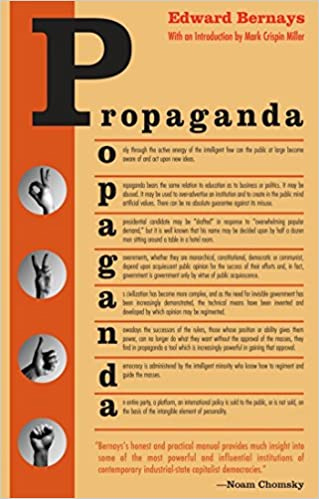

Notwithstanding the panic and pessimism, a consumer solution was simultaneously emerging. As the popular historian of the time Frederick Allen wrote , “Business had learned as never before the importance of the ultimate consumer. Unless he could be persuaded to buy and buy lavishly, the whole stream of six-cylinder cars, super heterodynes, cigarettes, rouge compacts and electric ice boxes would be dammed up at its outlets.” In his classic 1928 book “ Propaganda ,” Edward Bernays, one of the pioneers of the public relations industry, put it this way:

Mass production is profitable only if its rhythm can be maintained—that is if it can continue to sell its product in steady or increasing quantity.… Today supply must actively seek to create its corresponding demand … [and] cannot afford to wait until the public asks for its product; it must maintain constant touch, through advertising and propaganda … to assure itself the continuous demand which alone will make its costly plant profitable.

Edward Cowdrick, an economist who advised corporations on their management and industrial relations policies, called it “the new economic gospel of consumption,” in which workers (people for whom durable possessions had rarely been a possibility) could be educated in the new “skills of consumption.”

It was an idea also put forward by the new “consumption economists” such as Hazel Kyrk and Theresa McMahon, and eagerly embraced by many business leaders. New needs would be created, with advertising brought into play to “augment and accelerate” the process. People would be encouraged to give up thrift and husbandry, to value goods over free time. Kyrk argued for ever-increasing aspirations: “a high standard of living must be dynamic, a progressive standard,” where envy of those just above oneself in the social order incited consumption and fueled economic growth.

President Herbert Hoover’s 1929 Committee on Recent Economic Changes welcomed the demonstration “on a grand scale [of] the expansibility of human wants and desires,” hailed an “almost insatiable appetite for goods and services,” and envisaged “a boundless field before us … new wants that make way endlessly for newer wants, as fast as they are satisfied.” In this paradigm, people are encouraged to board an escalator of desires (a stairway to heaven, perhaps) and progressively ascend to what were once the luxuries of the affluent.

Charles Kettering, general director of General Motors Research Laboratories, equated such perpetual change with progress. In a 1929 article called “Keep the Consumer Dissatisfied,” he stated that “there is no place anyone can sit and rest in an industrial situation. It is a question of change, change all the time — and it is always going to be that way because the world only goes along one road, the road of progress.” These views parallel political economist Joseph Schumpeter’s later characterization of capitalism as “creative destruction”:

Capitalism, then, is by nature a form or method of economic change and not only never is, but never can be stationary .… The fundamental impulse that sets and keeps the capitalist engine in motion comes from the new consumers, goods, the new methods of production or transportation, the new markets, the new forms of industrial organization that capitalist enterprise creates.

The prospect of ever-extendable consumer desire, characterized as “progress,” promised a new way forward for modern manufacture, a means to perpetuate economic growth. Progress was about the endless replacement of old needs with new, old products with new. Notions of meeting everyone’s needs with an adequate level of production did not feature.

The nonsettler European colonies were not regarded as viable venues for these new markets, since centuries of exploitation and impoverishment meant that few people there were able to pay. In the 1920s, the target consumer market to be nourished lay at home in the industrialized world. There, especially in the United States, consumption continued to expand through the 1920s, though truncated by the Great Depression of 1929.

Electrification was crucial for the consumption of the new types of durable items, and the fraction of U.S. households with electricity connected nearly doubled between 1921 and 1929, from 35 percent to 68 percent; a rapid proliferation of radios, vacuum cleaners, and refrigerators followed. Motor car registration rose from eight million in 1920 to more than 28 million by 1929. The introduction of time payment arrangements facilitated the extension of such buying further and further down the economic ladder. In Australia, too, the trend could be observed; there, however, the base was tiny, and even though car ownership multiplied nearly fivefold in the eight years to 1929, few working-class households possessed cars or large appliances before 1945.

The prospect of ever-extendable consumer desire, characterized as “progress,” promised a new way forward for modern manufacture, a means to perpetuate economic growth.

This first wave of consumerism was short-lived. Predicated on debt, it took place in an economy mired in speculation and risky borrowing. U.S. consumer credit rose to $7 billion in the 1920s, with banks engaged in reckless lending of all kinds. Indeed, though a lot less in gross terms than the burden of debt in the United States in late 2008, which Sydney economist Steve Keen has described as “the biggest load of unsuccessful gambling in history,” the debt of the 1920s was very large, over 200 percent of the GDP of the time. In both eras, borrowed money bought unprecedented quantities of material goods on time payment and (these days) credit cards. The 1920s bonanza collapsed suddenly and catastrophically. In 2008, a similar unraveling began; its implications still remain unknown. In the case of the Great Depression of the 1930s, a war economy followed, so it was almost 20 years before mass consumption resumed any role in economic life — or in the way the economy was conceived.

The Second Wave

Once World War II was over, consumer culture took off again throughout the developed world, partly fueled by the deprivation of the Great Depression and the rationing of the wartime years and incited with renewed zeal by corporate advertisers using debt facilities and the new medium of television. Stuart Ewen, in his history of the public relations industry, saw the birth of commercial radio in 1921 as a vital tool in the great wave of debt-financed consumption in the 1920s — “a privately owned utility, pumping information and entertainment into people’s homes.”

“Requiring no significant degree of literacy on the part of its audience,” Ewen writes, “radio gave interested corporations … unprecedented access to the inner sanctums of the public mind.” The advent of television greatly magnified the potential impact of advertisers’ messages, exploiting image and symbol far more adeptly than print and radio had been able to do. The stage was set for the democratization of luxury on a scale hitherto unimagined.

Though the television sets that carried the advertising into people’s homes after World War II were new, and were far more powerful vehicles of persuasion than radio had been, the theory and methods were the same — perfected in the 1920s by PR experts like Bernays. Vance Packard echoes both Bernays and the consumption economists of the 1920s in his description of the role of the advertising men of the 1950s:

They want to put some sizzle into their messages by stirring up our status consciousness.… Many of the products they are trying to sell have, in the past, been confined to a “quality market.” The products have been the luxuries of the upper classes. The game is to make them the necessities of all classes . This is done by dangling the products before non-upper-class people as status symbols of a higher class. By striving to buy the product—say, wall-to-wall carpeting on instalment—the consumer is made to feel he is upgrading himself socially.

Though it is status that is being sold, it is endless material objects that are being consumed.

In a little-known 1958 essay reflecting on the conservation implications of the conspicuously wasteful U.S. consumer binge after World War II, John Kenneth Galbraith pointed to the possibility that this “gargantuan and growing appetite” might need to be curtailed. “What of the appetite itself?,” he asks. “Surely this is the ultimate source of the problem. If it continues its geometric course, will it not one day have to be restrained? Yet in the literature of the resource problem this is the forbidden question.”

“We need things consumed, burned up, replaced and discarded at an ever-accelerating rate,” retail analyst Victor Lebow remarked in 1955.

Galbraith quotes the President’s Materials Policy Commission setting out its premise that economic growth is sacrosanct. “First we share the belief of the American people in the principle of Growth,” the report maintains, specifically endorsing “ever more luxurious standards of consumption.” To Galbraith, who had just published “ The Affluent Society ,” the wastefulness he observed seemed foolhardy, but he was pessimistic about curtailment; he identified the beginnings of “a massive conservative reaction to the idea of enlarged social guidance and control of economic activity,” a backlash against the state taking responsibility for social direction. At the same time he was well aware of the role of advertising: “Goods are plentiful. Demand for them must be elaborately contrived,” he wrote. “Those who create wants rank amongst our most talented and highly paid citizens. Want creation — advertising — is a ten billion dollar industry.”

Or, as retail analyst Victor Lebow remarked in 1955:

Our enormously productive economy demands that we make consumption our way of life, that we convert the buying and use of goods into rituals, that we seek our spiritual satisfaction, our ego satisfaction, in consumption.… We need things consumed, burned up, replaced and discarded at an ever-accelerating rate.

Thus, just as immense effort was being devoted to persuading people to buy things they did not actually need, manufacturers also began the intentional design of inferior items, which came to be known as “planned obsolescence.” In his second major critique of the culture of consumption, “ The Waste Makers ,” Packard identified both functional obsolescence, in which the product wears out quickly and psychological obsolescence, in which products are “designed to become obsolete in the mind of the consumer, even sooner than the components used to make them will fail.”

Galbraith was alert to the way that rapidly expanding consumption patterns were multiplied by a rapidly expanding population. But postwar industrial enterprise stoked the expansion nonetheless. The rise of consumer debt, interrupted in 1929, also resumed. In Australia, the 1939 debt of AU$39 million doubled in the first two years after the war and, by 1960, had grown by a factor of 25, to more than AU$1 billion dollars. This new burst in debt-financed consumerism was, again, incited intentionally.

Tapping into the Unconscious: Image and Message

In researching his excellent history of the rise of PR, Ewen interviewed Bernays himself in 1990, not long before he turned 99. Ewen found Bernays, a key pioneer of the new PR profession, to be just as candid about his underlying motivations as he had been in 1928 when he wrote “Propaganda”:

Throughout our conversation, Bernays conveyed his hallucination of democracy: A highly educated class of opinion-molding tacticians is continuously at work … adjusting the mental scenery from which the public mind, with its limited intellect, derives its opinions.… Throughout the interview, he described PR as a response to a transhistoric concern: the requirement, for those people in power, to shape the attitudes of the general population.

Bernays’s views, like those of several other analysts of the “crowd” and the “herd instinct,” were a product of the panic created among the elite classes by the early 20th-century transition from the limited franchise of propertied men to universal suffrage. “On every side of American life, whether political, industrial, social, religious or scientific, the increasing pressure of public judgment has made itself felt,” Bernays wrote. “The great corporation which is in danger of having its profits taxed away or its sales fall off or its freedom impeded by legislative action must have recourse to the public to combat successfully these menaces.”

The opening page of “Propaganda” discloses his solution:

The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country.… It is they who pull the wires which control the public mind, who harness old social forces and contrive new ways to bind and guide the world.

The front-line thinkers of the emerging advertising and public relations industries turned to the key insights of Sigmund Freud, Bernays’s uncle. As Bernays noted:

Many of man’s thoughts and actions are compensatory substitutes for desires which [he] has been obliged to suppress. A thing may be desired, not for its intrinsic worth or usefulness, but because he has unconsciously come to see in it a symbol of something else, the desire for which he is ashamed to admit to himself … because it is a symbol of social position, an evidence of his success.

Bernays saw himself as a “propaganda specialist,” a “public relations counsel,” and PR as a more sophisticated craft than advertising as such; it was directed at hidden desires and subconscious urges of which its targets would be unaware. Bernays and his colleagues were anxious to offer their services to corporations and were instrumental in founding an entire industry that has since operated along these lines, selling not only corporate commodities but also opinions on a great range of social, political, economic, and environmental issues.

Though it has become fashionable in recent decades to brand scholars and academics as elites who pour scorn on ordinary people, Bernays and the sociologist Gustave Le Bon were long ago arguing, on behalf of business and political elites, respectively, that the mass of people are incapable of thought.

According to Le Bon, “A crowd thinks in images, and the image itself immediately calls up a series of other images, having no logical connection with the first”; crowds “can only comprehend rough-and-ready associations of ideas,” leading to “the utter powerlessness of reasoning when it has to fight against sentiment.” Bernays and his PR colleagues believed ordinary people to be incapable of logical thought, let alone mastery of “abstruse economic, political and ethical data,” and saw the need to “control and regiment the masses according to our will without their knowing about it”; PR could thus ensure the maintenance of order and corporate control in society.

Bernays and his PR colleagues believed ordinary people to be incapable of logical thought, let alone mastery of “abstruse economic, political and ethical data.”

The commodification of reality and the manufacture of demand have had serious implications for the construction of human beings in the late 20th century, where, to quote philosopher Herbert Marcuse, “people recognize themselves in their commodities.” Marcuse’s critique of needs, made more than 50 years ago, was not directed at the issues of scarce resources or ecological waste, although he was aware even at that time that Marx was insufficiently critical of the continuum of progress and that there needed to be “a restoration of nature after the horrors of capitalist industrialisation have been done away with.”

Marcuse directed his critique at the way people, in the act of satisfying our aspirations, reproduce dependence on the very exploitive apparatus that perpetuates our servitude. Hours of work in the United States have been growing since 1950, along with a doubling of consumption per capita between 1950 and 1990. Marcuse suggested that this “voluntary servitude (voluntary inasmuch as it is introjected into the individual) … can be broken only through a political practice which reaches the roots of containment and contentment in the infrastructure of man [ sic ], a political practice of methodical disengagement from and refusal of the Establishment, aiming at a radical transvaluation of values.”

The difficult challenge posed by such a transvaluation is reflected in current attitudes. The Australian comedian Wendy Harmer in her 2008 ABC TV series called “Stuff” expressed irritation at suggestions that consumption is simply generated out of greed or lack of awareness:

I am very proud to have made a documentary about consumption that does not contain the usual footage of factory smokestacks, landfill tips and bulging supermarket trolleys. Instead, it features many happy human faces and all their wonderful stuff! It’s a study of a love affair as much as anything else.

In the same vein, during the Q&A after a talk given by the Australian economist Clive Hamilton at the 2006 Byron Bay Writers’ Festival, one woman spoke up about her partner’s priorities: Rather than entertain questions about any impact his possessions might be having on the environment, she said, he was determined to “go down with his gadgets.”

The capitalist system, dependent on a logic of never-ending growth from its earliest inception, confronted the plenty it created in its home states, especially the United States, as a threat to its very existence. It would not do if people were content because they felt they had enough. However over the course of the 20th century, capitalism preserved its momentum by molding the ordinary person into a consumer with an unquenchable thirst for its “wonderful stuff.”

Kerryn Higgs is an Australian writer and historian. She is the author of “ Collision Course: Endless Growth on a Finite Planet ,” from which this article is adapted.

Consumers, Society and Marketing pp 1–29 Cite as

Consumption and Consumer Society

- Dilip S. Mutum ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9857-1164 5 &

- Ezlika M. Ghazali ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7824-4433 6

- First Online: 08 September 2023

295 Accesses

Part of the book series: CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance ((CSEG))

This chapter explores the intricate relationships between consumption, consumer society, and marketing's substantial role in economic development. It delves into the premise of consumer sovereignty, where consumers influence various aspects such as public policy, social welfare, and environmental health through their buying patterns. The critical question posed is the definition of a sovereign consumer and how this notion leads to consumer empowerment. As consumer influence expands, businesses must reshape their interactions with customers, acknowledging that many still remain vulnerable due to particular constraints and marketing practices. Consequently, the chapter emphasizes the necessity to craft strategies that promote consumer empowerment while mitigating their vulnerabilities in the marketplace.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Acar, O. A., & Puntoni, S. (2016). Customer empowerment in the digital age. Journal of Advertising Research, 56 (1), 4–8.

Article Google Scholar

Akhavannasab, S., Dantas, D. C., & Senecal, S. (2018). Consumer empowerment in consumer–firm relationships: Conceptual framework and implications for research. AMS Review, 8 (3–4), 214–227.

Allen, D. E., & Anderson, P. F. (1994). Consumption and social stratification: Bourdieu’s distinction. Advances in Consumer Research, 21 , 70–74.

Google Scholar

Bachouche, H., & Sabri, O. (2019). Empowerment in marketing: Synthesis, critical review, and agenda for future research. AMS Review, 9 (3–4, 304), –323.

Baker, S. M., Gentry, J. W., & Rittenburg, T. L. (2005). Building understanding of the domain of consumer vulnerability. Journal of Macromarketing, 25 (2), 128–139.

Barbalet, J. M. (1985). Power and resistance. The British Journal of Sociology, 36 (4), 531.

Batat, W., & Tanner, J. F. (2021). Unveiling (in)vulnerability in an adolescent’s consumption subculture: A framework to understand adolescents’ experienced (in)vulnerability and ethical implications. Journal of Business Ethics, 169 (4), 713–730.

Berg, L. (2015). Consumer vulnerability: Are older people more vulnerable as consumers than others? International Journal of Consumer Studies, 39 (4), 284–293.

Bertrand, M., Mullainathan, S., & Shafir, E. (2006). Behavioral economics and marketing in aid of decision making among the poor. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing, 25 (1), 8–23.

Boyd, C. (2012). The Nestlé infant formula controversy and a strange web of subsequent business scandals. Journal of Business Ethics, 106 (3), 283–293.

Branstad, A., & Solem, B. A. (2020). Emerging theories of consumer-driven market innovation, adoption, and diffusion: A selective review of consumer-oriented studies. Journal of Business Research, 116 , 561–571.

Broniarczyk, S. M., & Griffin, J. G. (2014). Decision difficulty in the age of consumer empowerment. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 24 (4), 608–625.

Carrington, M. J., Zwick, D., & Neville, B. (2016). The ideology of the ethical consumption gap. Marketing Theory, 16 (1), 21–38.

Chatzidakis, A., Hakim, J., Littler, J., Rottenberg, C., & Segal, L. (2020). From carewashing to radical care: The discursive explosions of care during Covid-19. Feminist Media Studies, 20 (6), 889–895.

Coffin, J., & Egan-Wyer, C. (2022). The ethical consumption cap and mean market morality. Marketing Theory, 22 (1), 105–123.

Cohen, L. (2008). A consumers’ republic: The politics of mass consumption in postwar America . Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Smith, N. C., & Cooper-Martin, E. (1997). Ethics and target marketing: The role of product harm and consumer vulnerability. Journal of Marketing, 61 (3), 1–20.

Cvjetanovic, M. (2013). Consumer sovereignty : The Australian experience. Monash University LawReview, 252 (254), 67–91.

De Veirman, M., Hudders, L., & Nelson, M. R. (2019). What is influencer marketing and How does it target children? A review and direction for future research. Frontiers in Psychology, 10 (December). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02685

Delgadillo, L. M. (2013). An assessment of consumer protection and consumer empowerment in Costa Rica. Journal of Consumer Policy, 36 (1), 59–86.

Denegri-Knott, J. (2006). Sinking the online “music pirates:” foucault, power and deviance on the web. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 9 (4). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2004.tb00293.x

Duggan, A. (1992). Some reflections on consumer protection and the law reform process. Monash University Law Review, 17 , 252.

Efuribe, C., Barre-Hemingway, M., Vaghefi, E., & Suleiman, A. B. (2020). Coping with the COVID-19 crisis: A call for youth engagement and the inclusion of Young people in matters that affect their lives. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67 (1), 16–17.

FCA. (2014). Consumer credit and consumers in vulnerable circumstances. Financial Conduct Authority . Available at: https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/research/consumer-credit-customers-vulnerable-circumstances.pdf

Ferrell, O. C., Harrison, D. E., Ferrell, L., & Hair, J. F. (2019). Business ethics, corporate social responsibility, and brand attitudes: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Research, 95 (January), 491–501.

Freathy, P., & Calderwood, E. (2020). Social transformation in the Scottish islands: Liberationist perspectives on consumer empowerment. Journal of Rural Studies, 74 , 180–189.

Gentry, J. W., Kennedy, P. F., Paul, K., & Hill, R. P. (1995). The vulnerability of those grieving the death of a loved one: Implications for public policy. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 14 (1), 128–142.

Hamilton, K., & Catterall, M. (2005). “I can do it!” consumer coping and poverty. Advances in Consumer Research, 35 , 551–556.

Harrison, T., Waite, K., & Hunter, G. L. (2006). The internet, information and empowerment. European Journal of Marketing, 40 (9–10), 972–993.

Henry, P. C. (2005). Social class, market situation, and consumers’ metaphors of (dis)empowerment. Journal of Consumer Research, 31 (4), 766–778.

Hill, R. P. (2005). Do the poor deserve less than surfers? An essay for the special issue on vulnerable consumers. Journal of Macromarketing, 25 (2), 215–218.

Hoffmann, A. O. I., & McNair, S. J. (2019). How does consumers’ financial vulnerability relate to positive and negative financial outcomes? The mediating role of individual psychological characteristics. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 53 (4), 1630–1673.

Hsieh, S. H., Lee, C. T., & Tseng, T. H. (2022). Psychological empowerment and user satisfaction: Investigating the influences of online brand community participation. Information and Management, 59 (1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2021.103570

Hu, H., & fen, & Krishen, A. S. (2019). When is enough, enough? Investigating product reviews and information overload from a consumer empowerment perspective. Journal of Business Research, 100 (March), 27–37.

Hudders, L., Van Reijmersdal, E. A., & Poels, K. (2019). Digital advertising and consumer empowerment. Cyberpsychology, 13 (2). https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2019-2-xx

Hur, M. H. (2006). Empowerment in terms of theoretical perspectives: Exploring a typology of the process and components across disciplines. Journal of Community Psychology, 34 (5), 523–540.

Hutt, W. H. (1940). The concept of consumers’ sovereignty. The Economic Journal, 50 (197), 66.

Ioannidou, M. (2018). Effective paths for consumer empowerment and protection in retail energy markets. Journal of Consumer Policy, 41 (2), 135–157.

Jaworowska, A., Blackham, T., Davies, I. G., & Stevenson, L. (2013). Nutritional challenges and health implications of takeaway and fast food. Nutrition Reviews, 71 (5), 310–318.

Johnson, M. (2022, January). New global Nielsen study reveals who trusts what in advertising. Mediashotz . Available at: https://mediashotz.co.uk/new-global-nielsen-study-reveals-who-trusts-what-in-advertising/ .

Johnston, J. (2008). The citizen-consumer hybrid: Ideological tensions and the case of whole foods market. Theory and Society, 37 (3), 229–270.

Jones, E. (2019). Rethinking greenwashing: Corporate discourse, unethical practice, and the unmet potential of ethical consumerism. Sociological Perspectives, 62 (5), 728–754.

Keltner, D., Gruenfeld, D. H., & Anderson, C. (2003). Power, approach, and inhibition. Psychological Review, 110 (2), 265–284.

Kong, N., & Zhou, W. (2018). The massive expansion of Western fast-food restaurants and Children’s weight in China. SSRN . https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3131308

Kong, N., & Zhou, W. (2021). The curse of modernization? Western fast food and Chinese children’s weight. Health Economics, 30 (10), 2345–2366.

Kucuk, S. U. (2009). Consumer empowerment model: From unspeakable to undeniable. Direct Marketing, 3 (4), 327–342.

Kucuk, S. U., & Krishnamurthy, S. (2007). An analysis of consumer power on the Internet. Technovation, 27 (1–2), 47–56.

Kyroglou, G., & Henn, M. (2022). Young political consumers between the individual and the collective: Evidence from the UK and Greece. Journal of Youth Studies, 25 (6), 833–853.

Lammers, J., Stoker, J. I., & Stapel, D. A. (2009). Differentiating social and personal power: Opposite effects on stereotyping, but parallel effects on behavioral approach tendencies. Psychological Science, 20 (12), 1543–1549.

Li, J., Qi, J., Wu, L., Shi, N., Li, X., Zhang, Y., & Zheng, Y. (2021). The continued use of social commerce platforms and psychological anxiety—The roles of influencers, informational incentives and fomo. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18 (22), 12254.

Li, Z. (2019). From power to punishment: Consumer empowerment and online complaining behaviors. Internet Research, 29 (6), 1324–1343.

Long, M. A., & Murray, D. L. (2013). Ethical consumption, values convergence/divergence and community development. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 26 (2), 351–375.

Markus, H. R., & Schwartz, B. (2010). Does choice mean freedom and Well-being? Journal of Consumer Research, 37 (2), 344–355.

McShane, L., & Sabadoz, C. (2015). Rethinking the concept of consumer empowerment: Recognizing consumers as citizens. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 39 (5), 544–551.

Mehta, S., Saxena, T., & Purohit, N. (2020). The new consumer behaviour paradigm amid covid-19: Permanent or transient? Journal of Health Management, 22 (2), 291–301.

Merlo, O., Whitwell, G. J., & Lukas, B. A. (2004). Power and marketing. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 12 (4), 207–218.

Mo, P. K. H., & Coulson, N. S. (2010). Empowering processes in online support groups among people living with HIV/AIDS: A comparative analysis of “lurkers” and “posters”. Computers in Human Behavior, 26 (5), 1183–1193.

Mochon, D., Norton, M. I., & Ariely, D. (2012). Bolstering and restoring feelings of competence via the IKEA effect. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29 (4), 363–369.

Nairn, A., & Berthon, P. (2003). Creating the customer: The influence of advertising on consumer market segments: Evidence and ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 42 (1), 83–99.

Narver, J. C., & Savitt, R. (1971). The marketing economy. Rinehart &Winston.

Nishadi, G. P. K., Warnakulasooriya, B. N. F., & Chandralal, K. P. L. (2021). Adolescent consumer vulnerability: Consumer socialization perspective. Sri Lanka Journal of Marketing, 7 (3), 72.

Norkus, Z. (2003). Consumer sovereignty: Theory and praxis. PRO, 64 (January 2003), 9–24.

Pang, S. M., Tan, B. C., & Lau, T. C. (2021). Antecedents of consumers’ purchase intention towards organic food: Integration of theory of planned behavior and protection motivation theory. Sustainability, 13 (9). https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095218

Perkins, D. D., & Zimmerman, M. A. (1995). Empowerment theory, research, and application. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23 , 569–579.

Petrescu, M., Krishen, A., & Bui, M. (2020). The internet of everything: Implications of marketing analytics from a consumer policy perspective. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 37 (6), 675–686.

Pittz, T. G., Steiner, S. D., & Pennington, J. R. (2020). An ethical marketing approach to wicked problems: Macromarketing for the common good. Journal of Business Ethics, 164 (2), 301–310.

Redmond, W. H. (2000). Consumer rationality and consumer sovereignty. Review of Social Economy, 58 (2), 177–196.

Reekie, W. D. (1988). Consumers’ sovereignty revisited. Managerial and Decision Economics, 9 (5), 17–25.

Rothenberg, J. (1962). Consumers’ sovereignty revisited and the hospitability of freedom of choice. The American Economic Review, 52 (2), 269–283.

Shandwick, W. (2018). Battle of the Wallets: The changing landscape of consumer activism . Available at: https://www.webershandwick.com/uploads/news/files/Battle_of_the_Wallets.pdf

Shao, J., Zhang, Q., Ren, Y., Li, X., & Lin, T. (2019). Why are older adults victims of fraud? Current knowledge and prospects regarding older adults’ vulnerability to fraud. Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, 31 (3), 225–243.

Shaw, D., McMaster, R., & Newholm, T. (2016). Care and commitment in ethical consumption: An exploration of the ‘attitude–behaviour gap.’ Journal of Business Ethics, 136(2), 251–265.

Sheth, J. N., & Parvatiyar, A. (2021). Sustainable marketing: Market-driving, not market-driven. Journal of Macromarketing, 41 (1), 150–165.

Silva, R. O., Barros, D. F., Gouveia, T. M. D. O. A., & Merabet, D. D. O. B. (2021). A necessary discussion on consumer vulnerability: Advances, gaps, and new perspectives. Cadernos EBAPE.BR, 19 (1), 83–95.

Simanjuntak, M., Amanah, S., Puspitawati, H., & Asngari, P. S. (2014). Consumer empowerment profile in rural and Urban area. ASEAN Marketing Journal, 6 (1), 38–49.

Simanjuntak, M., & Saniyya, R. U. (2021). Consumer empowerment in transportation sector. International Research Journal of Business Studies, 14 (1), 1–12.

Sirgy, M. J., & Lee, D. J. (2008). Well-being marketing: An ethical business philosophy for consumer goods firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 77 (4), 377–403.

Skiba, J., Petty, R. D., & Carlson, L. (2019). Beyond deception: Potential unfair consumer injury from various types of covert marketing. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 53 (4).

Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38 (5), 1442–1465.

Sroka, W., & Szántó, R. (2018). Corporate social responsibility and business ethics in controversial sectors: Analysis of research results. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 14 (3), 111–126.

Stewart, C. R., & Yap, S. (2020). Low literacy, policy and consumer vulnerability: Are we really doing enough? International Journal of Consumer Studies, 44 (4), 343–352.

Szabo, S., & Webster, J. (2021). Perceived greenwashing: The effects of green marketing on environmental and product perceptions. Journal of Business Ethics, 171 (4), 719–739.

Tadajewski, M. (2018). Critical reflections on the marketing concept and consumer sovereignty. In The Routledge companion to critical marketing (Vol. 44, pp. 196–224). Routledge.

Chapter Google Scholar

Tajurahim, N. N. S., Abu Bakar, E., Md Jusoh, Z., Ahmad, S., & Muhammad Arif, A. M. (2020). The effect of intensity of consumer education, self-efficacy, personality traits and social media on consumer empowerment. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 44 (6), 511–520.

Tan, L. P., Johnstone, M. L., & Yang, L. (2016). Barriers to green consumption behaviours: The roles of consumers’ green perceptions. Australasian Marketing Journal, 24 (4), 288–299.

Urban, B. (2008). Social entrepreneurship in South Africa: Delineating the construct with associated skills. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 14 (5), 346–364.

Visconti, L. M. (2016). A conversational approach to consumer vulnerability: Performativity, representations, and storytelling. Journal of Marketing Management, 32 (3–4), 371–385.

Wang, J. J., Zhao, X., & Li, J. J. (2011). Team purchase: A case of consumer empowerment in China. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 45 (3), 528–538.

Wathieu, L., Brenner, L., Carmon, Z., Chattopadhyay, A., Wertenbroch, K., Drolet, I. A., Gourville, J., Muthukrishnan, A. V., Novemsky, N., Ratner, R. K., & Wu, G. (2002). Consumer control and empowerment: A primer. Marketing Letters, 13 (3), 297–305.

Witkowski, T. H. (2007). Food marketing and obesity in developing countries: Analysis, ethics, and public policy. Journal of Macromarketing, 27 (2), 126–137.

Wolf, M., Albinsson, P. A., & Becker, C. (2015). Do-it-yourself projects as path toward female empowerment in a gendered market place. Psychology & Marketing, 32 (2), 133–143.

Wright, L. T., Newman, A., & Dennis, C. (2006). Enhancing consumer empowerment. European Journal of Marketing, 40 (9/10), 925–935.

Xiao, B., & Benbasat, I. (2011). Product-related deception in E-commerce: A theoretical perspective. MIS Quarterly: Management Information Systems, 35 (1), 169–195.

Zaltman, G., Srivastava, R. K., & Deshpande, R. (1978). Perceptions of unfair marketing practices: Consumerism implications. Advances in Consumer Research, 5 , 247–253.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Business, Monash University Malaysia, Subang Jaya, Malaysia

Dilip S. Mutum

Faculty of Business and Economics, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Ezlika M. Ghazali

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Mutum, D.S., Ghazali, E.M. (2023). Consumption and Consumer Society. In: Consumers, Society and Marketing. CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-39359-4_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-39359-4_1

Published : 08 September 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-39358-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-39359-4

eBook Packages : Business and Management Business and Management (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

ReviseSociology

A level sociology revision – education, families, research methods, crime and deviance and more!

Sociological Theories of Consumerism and Consumption

The consumption of goods and services is so thoroughly embedded into our ordinary, everyday lives that many aspects of its practice go largely unquestioned – not only the environmental and social consequences have got lost on the way, but also they very notion that consumption itself is a choice, and that, once our basic needs are met, consumption in its symbolic sense is not necessary and thus is itself a choice.

In sociological terms one might say that contemporary reflexivity is bounded by consumption – that is to say that most of the things most of us think about in life – be they pertaining to self-construction, relationship maintenance, or instrumental goal-attainment, involve us making choices about (the strictly unnecessary) things we might consume.

Even though I think that any attempt to achieve happiness through consumption will ultimately result in misery, I would hardly call anyone who tries to do so stupid – because all they are going is conforming to a number of recent social changes which have led to our society being based around historically high levels of consumption.

There are numerous explanations for the growth of a diverse consumer culture and thus the intense levels of unnecessary symbolic consumption engaged in by most people today – the overview taken below is primarily from Joel Stillerman (2015) who seems to identify five major changes which underpin recent changes in consumption since WW2.

The first explanation looks to the 1960s counter culture which despite having a reputation for being anti-consumerist, was really more about non-conformity, a rejection of standardised mass-consumption and promoting individual self expression. Ironically, the rejection of standardised consumption became a model for the niche-marketing of today, much of which is targeted towards people who wish to express themselves in any manor of ways – through clothing, music, foodism, craft beers, or experiences. Some members of the counter culture in fact found profit in establishing their own niche-consumer outlets, with even some Punks (surely the Zenith of anti-consumerism?!) going on to develop their own clothing brands.

A second discussion surrounding the normalisation of consumerism centres around changes in the class structure, following the work Bourdieu and Featherstone (2000). Basically these theorists see the intensification of consumption as being related to the emergence of the ‘new middle classes’ as a result of technological innovations and social changes leading to an increase in the number of people working in jobs such as the media and fashion.

Mike Featherstone focuses on what he calls the importance of ‘cultural intermediaries’ (who mainly work in the entertainment and personal care industries) who have adopted an ‘ethic of self-expression through consumption’ – in which they engage in self-care in order to improve their bodies and skills in order to gain social and economic capital.

The values of these early adopters has gradually filtered down to the rest of the population and this has resulted in the ‘aestheticisation of daily life’ – in which more and more people are now engaged in consumption in order to improve themselves and their social standing – as evidenced in various fitness classes, plastic surgery, and a whole load of ‘skills based’ pursuits such as cookery classes (yer signature bake if you like).

A third perspective focuses on individualisation – as advanced by the likes of Zygmunt Bauman and Ulrich Beck.

In their view, after World War II, universal access to higher education and social welfare benefits in Europe led to the erosion of traditional sources of identity provided by family, traditional authority, and work. Today, individuals are ‘free’ from the chains of external sources of identity, but this freedom comes at a price. Individuals are now compelled to give meaning to their lives without the certainty that they are making the right choice that in the past had come from tradition. Individuals are forced to be reflexive, to examine their own lives and to determine their own identities. In this context, consumption may be a useful vehicle for constructing a life narrative that gives focus and meaning to individuals.

As I’ve outlined in numerous blog posts before, Bauman especially sees this is a lot of work for individuals – a never ending task, and a task over which they have no choice but to engage in (actually I disagree here, individuals do have a choice, it’s just not that easy to see it, or carry it through!).

Fourthly , Post-modern analyses of consumption focus on the increasing importance of individuals to consumption. Building on the work of Lytoard etc. Firat and Venkatesh (1995) argue that changes to Western cultures have led to the erosion of modernist ideas of progress, overly simplified binary distinctions like production and consumption and the notion of the individual as a unified actor. They suggest that in contemporary societies production and consumption exist in a repeating cycle and retail cites and advertiser have increasingly focussed on producing symbols which individuals consume in order to construct identities.

These changes have led to increasing specialising of products and more visually compelling shopping environments, and F and V argue that these changes are liberating for individuals and they seek meaning and identity through consumption, which they can increasingly do outside of markets.

Fifthly – other researches have looked at the role of subcultures in contemporary society, where individuals consume in order to signify their identity as part of a group, and doing so can involve quite high levels of consumption, even if these groups appear quite deviant (McAlexander’s 1995 study of Harley Davidson riders looks interesting here, also Kozinet’s study of Star Trek fans).

Something which draws on numbers 3,4 and 5 above is the concept of consumer tribes (developed by Cova et al 2007) which are constantly in flux, made up by different individuals whose identities are multiple, diverse and playful – individuals in fact may be part of many tribes and enter and exit them as they choose.

Finally, Stillerman points out that underlying all of the above are two important background trends

- Firstly, there are the technological changes which made all of the above possible – the transport links and the communications technologies.

- Secondly there is the (often discussed) links to the global south as a source of cheap production.

Very finally I’m going to add in one more thing to the above – underlying the increase in and diversification of consumption is the fact that time has sped up – in the sense that fashions change faster than ever and products become obsolete faster than ever – hence putting increasing demands on people to spend more time and money year on year to keep up on the consumer treadmill….

So there you have it – there are numerous social trends which lie behind the increase in and diversification of consumption, so the next time you think you’re acting as an individual when you’re getting your latest tattoo, maybe think again matey!

Related Posts

Consuming Life (Bauman, 2007) – A Summary of Chapter One

If you like this sort of thing – then why not my book?

Early Retirement Strategies for the Average Income Earner, or A Critique of Curiously Ordinary Life of the Everyday Worker-Consumer

Available on iTunes , Kobo , and Barnes and Noble – Only £0.63 ($0.99)

Also available on Amazon , but for $3.10 because I’d get a much lower cut if I charged less!

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

One thought on “Sociological Theories of Consumerism and Consumption”

- Pingback: I consume, therefore I am - CALINA MURESAN

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from ReviseSociology

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

The Sociology of Consumption

Peathegee Inc / Getty Images

- Key Concepts

- Major Sociologists

- News & Issues

- Research, Samples, and Statistics