Coronavirus and schools: Reflections on education one year into the pandemic

Subscribe to the center for universal education bulletin, daphna bassok , daphna bassok nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy @daphnabassok lauren bauer , lauren bauer fellow - economic studies , associate director - the hamilton project @laurenlbauer stephanie riegg cellini , stephanie riegg cellini nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy helen shwe hadani , helen shwe hadani former brookings expert @helenshadani michael hansen , michael hansen senior fellow - brown center on education policy , the herman and george r. brown chair - governance studies @drmikehansen douglas n. harris , douglas n. harris nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy , professor and chair, department of economics - tulane university @douglasharris99 brad olsen , brad olsen senior fellow - global economy and development , center for universal education @bradolsen_dc richard v. reeves , richard v. reeves president - american institute for boys and men @richardvreeves jon valant , and jon valant director - brown center on education policy , senior fellow - governance studies @jonvalant kenneth k. wong kenneth k. wong nonresident senior fellow - governance studies , brown center on education policy.

March 12, 2021

- 11 min read

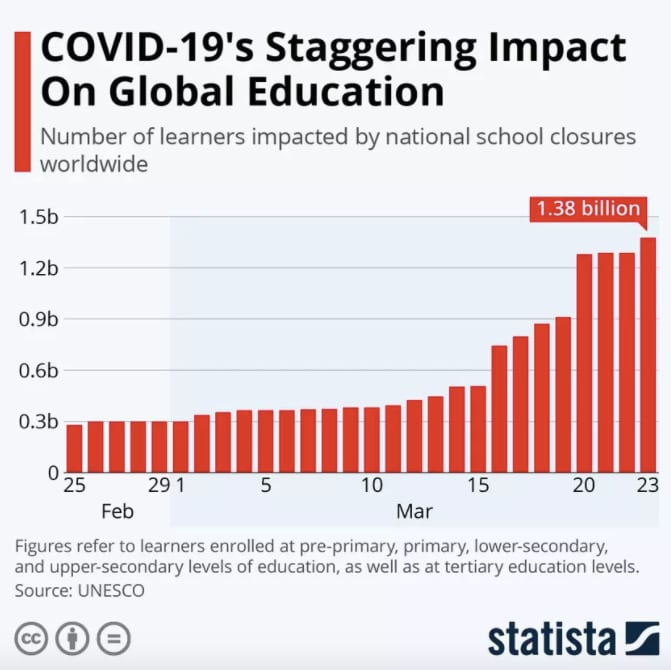

One year ago, the World Health Organization declared the spread of COVID-19 a worldwide pandemic. Reacting to the virus, schools at every level were sent scrambling. Institutions across the world switched to virtual learning, with teachers, students, and local leaders quickly adapting to an entirely new way of life. A year later, schools are beginning to reopen, the $1.9 trillion stimulus bill has been passed, and a sense of normalcy seems to finally be in view; in President Joe Biden’s speech last night, he spoke of “finding light in the darkness.” But it’s safe to say that COVID-19 will end up changing education forever, casting a critical light on everything from equity issues to ed tech to school financing.

Below, Brookings experts examine how the pandemic upended the education landscape in the past year, what it’s taught us about schooling, and where we go from here.

In the United States, we tend to focus on the educating roles of public schools, largely ignoring the ways in which schools provide free and essential care for children while their parents work. When COVID-19 shuttered in-person schooling, it eliminated this subsidized child care for many families. It created intense stress for working parents, especially for mothers who left the workforce at a high rate.

The pandemic also highlighted the arbitrary distinction we make between the care and education of elementary school children and children aged 0 to 5 . Despite parents having the same need for care, and children learning more in those earliest years than at any other point, public investments in early care and education are woefully insufficient. The child-care sector was hit so incredibly hard by COVID-19. The recent passage of the American Rescue Plan is a meaningful but long-overdue investment, but much more than a one-time infusion of funds is needed. Hopefully, the pandemic represents a turning point in how we invest in the care and education of young children—and, in turn, in families and society.

Congressional reauthorization of Pandemic EBT for this school year , its extension in the American Rescue Plan (including for summer months), and its place as a central plank in the Biden administration’s anti-hunger agenda is well-warranted and evidence based. But much more needs to be done to ramp up the program–even today , six months after its reauthorization, about half of states do not have a USDA-approved implementation plan.

In contrast, enrollment is up in for-profit and online colleges. The research repeatedly finds weaker student outcomes for these types of institutions relative to community colleges, and many students who enroll in them will be left with more debt than they can reasonably repay. The pandemic and recession have created significant challenges for students, affecting college choices and enrollment decisions in the near future. Ultimately, these short-term choices can have long-term consequences for lifetime earnings and debt that could impact this generation of COVID-19-era college students for years to come.

Many U.S. educationalists are drawing on the “build back better” refrain and calling for the current crisis to be leveraged as a unique opportunity for educators, parents, and policymakers to fully reimagine education systems that are designed for the 21st rather than the 20th century, as we highlight in a recent Brookings report on education reform . An overwhelming body of evidence points to play as the best way to equip children with a broad set of flexible competencies and support their socioemotional development. A recent article in The Atlantic shared parent anecdotes of children playing games like “CoronaBall” and “Social-distance” tag, proving that play permeates children’s lives—even in a pandemic.

Tests play a critical role in our school system. Policymakers and the public rely on results to measure school performance and reveal whether all students are equally served. But testing has also attracted an inordinate share of criticism, alleging that test pressures undermine teacher autonomy and stress students. Much of this criticism will wither away with different formats. The current form of standardized testing—annual, paper-based, multiple-choice tests administered over the course of a week of school—is outdated. With widespread student access to computers (now possible due to the pandemic), states can test students more frequently, but in smaller time blocks that render the experience nearly invisible. Computer adaptive testing can match paper’s reliability and provides a shorter feedback loop to boot. No better time than the present to make this overdue change.

A third push for change will come from the outside in. COVID-19 has reminded us not only of how integral schools are, but how intertwined they are with the rest of society. This means that upcoming schooling changes will also be driven by the effects of COVID-19 on the world around us. In particular, parents will be working more from home, using the same online tools that students can use to learn remotely. This doesn’t mean a mass push for homeschooling, but it probably does mean that hybrid learning is here to stay.

I am hoping we will use this forced rupture in the fabric of schooling to jettison ineffective aspects of education, more fully embrace what we know works, and be bold enough to look for new solutions to the educational problems COVID-19 has illuminated.

There is already a large gender gap in education in the U.S., including in high school graduation rates , and increasingly in college-going and college completion. While the pandemic appears to be hurting women more than men in the labor market, the opposite seems to be true in education.

Looking through a policy lens, though, I’m struck by the timing and what that timing might mean for the future of education. Before the pandemic, enthusiasm for the education reforms that had defined the last few decades—choice and accountability—had waned. It felt like a period between reform eras, with the era to come still very unclear. Then COVID-19 hit, and it coincided with a national reckoning on racial injustice and a wake-up call about the fragility of our democracy. I think it’s helped us all see how connected the work of schools is with so much else in American life.

We’re in a moment when our long-lasting challenges have been laid bare, new challenges have emerged, educators and parents are seeing and experimenting with things for the first time, and the political environment has changed (with, for example, a new administration and changing attitudes on federal spending). I still don’t know where K-12 education is headed, but there’s no doubt that a pivot is underway.

- First, state and local leaders must leverage commitment and shared goals on equitable learning opportunities to support student success for all.

- Second, align and use federal, state, and local resources to implement high-leverage strategies that have proven to accelerate learning for diverse learners and disrupt the correlation between zip code and academic outcomes.

- Third, student-centered priority will require transformative leadership to dismantle the one-size-fits-all delivery rule and institute incentive-based practices for strong performance at all levels.

- Fourth, the reconfigured system will need to activate public and parental engagement to strengthen its civic and social capacity.

- Finally, public education can no longer remain insulated from other policy sectors, especially public health, community development, and social work.

These efforts will strengthen the capacity and prepare our education system for the next crisis—whatever it may be.

Higher Education K-12 Education

Brookings Metro Economic Studies Global Economy and Development Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy Center for Universal Education

Darcy Hutchins, Emily Markovich Morris, Laura Nora, Carolina Campos, Adelaida Gómez Vergara, Nancy G. Gordon, Esmeralda Macana, Karen Robertson

March 28, 2024

Jennifer B. Ayscue, Kfir Mordechay, David Mickey-Pabello

March 26, 2024

Anna Saavedra, Morgan Polikoff, Dan Silver

Mission: Recovering Education in 2021

THE CONTEXT

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused abrupt and profound changes around the world. This is the worst shock to education systems in decades, with the longest school closures combined with looming recession. It will set back progress made on global development goals, particularly those focused on education. The economic crises within countries and globally will likely lead to fiscal austerity, increases in poverty, and fewer resources available for investments in public services from both domestic expenditure and development aid. All of this will lead to a crisis in human development that continues long after disease transmission has ended.

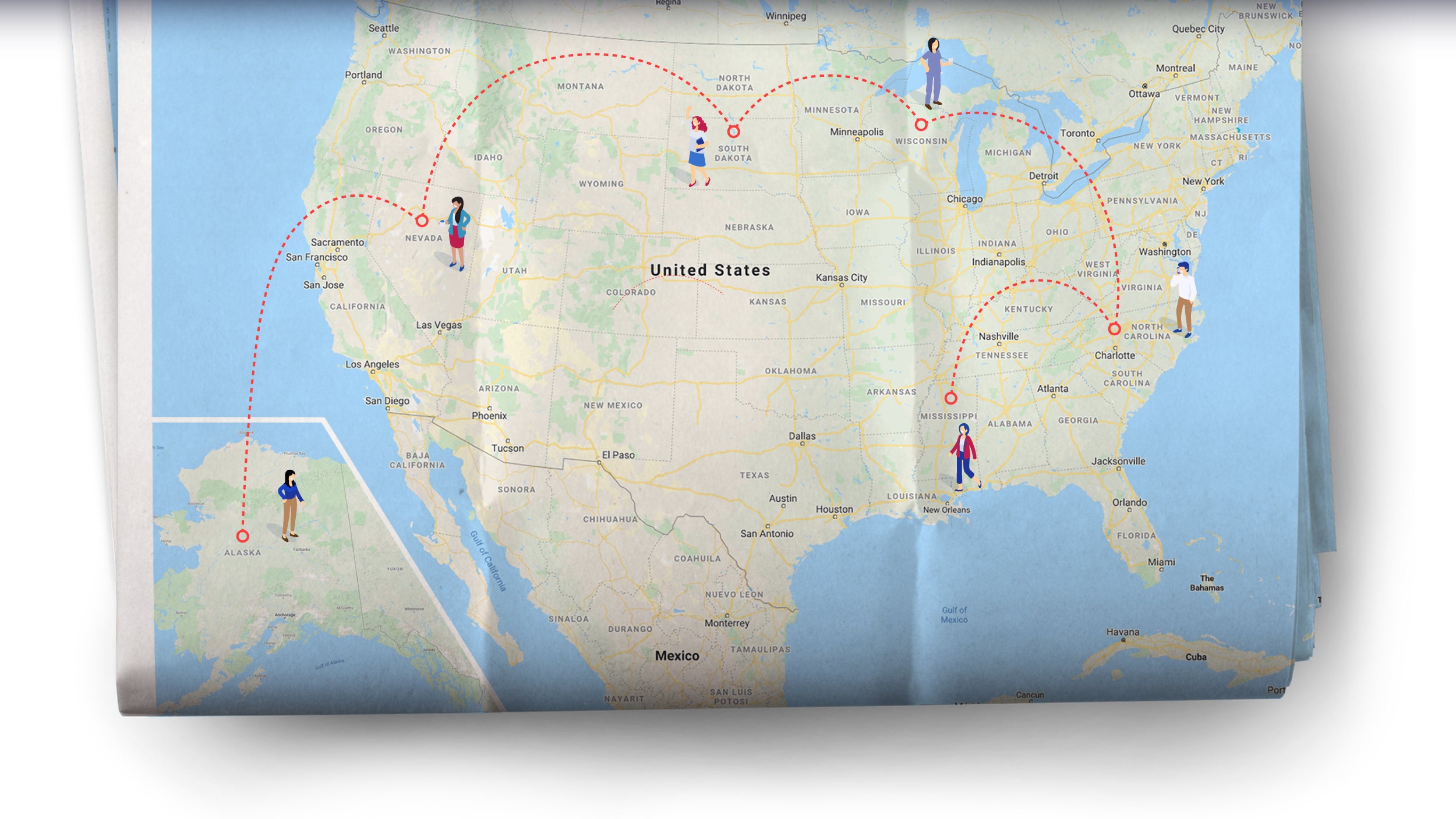

Disruptions to education systems over the past year have already driven substantial losses and inequalities in learning. All the efforts to provide remote instruction are laudable, but this has been a very poor substitute for in-person learning. Even more concerning, many children, particularly girls, may not return to school even when schools reopen. School closures and the resulting disruptions to school participation and learning are projected to amount to losses valued at $10 trillion in terms of affected children’s future earnings. Schools also play a critical role around the world in ensuring the delivery of essential health services and nutritious meals, protection, and psycho-social support. Thus, school closures have also imperilled children’s overall wellbeing and development, not just their learning.

It’s not enough for schools to simply reopen their doors after COVID-19. Students will need tailored and sustained support to help them readjust and catch-up after the pandemic. We must help schools prepare to provide that support and meet the enormous challenges of the months ahead. The time to act is now; the future of an entire generation is at stake.

THE MISSION

Mission objective: To enable all children to return to school and to a supportive learning environment, which also addresses their health and psychosocial well-being and other needs.

Timeframe : By end 2021.

Scope : All countries should reopen schools for complete or partial in-person instruction and keep them open. The Partners - UNESCO , UNICEF , and the World Bank - will join forces to support countries to take all actions possible to plan, prioritize, and ensure that all learners are back in school; that schools take all measures to reopen safely; that students receive effective remedial learning and comprehensive services to help recover learning losses and improve overall welfare; and their teachers are prepared and supported to meet their learning needs.

Three priorities:

1. All children and youth are back in school and receive the tailored services needed to meet their learning, health, psychosocial wellbeing, and other needs.

Challenges : School closures have put children’s learning, nutrition, mental health, and overall development at risk. Closed schools also make screening and delivery for child protection services more difficult. Some students, particularly girls, are at risk of never returning to school.

Areas of action : The Partners will support the design and implementation of school reopening strategies that include comprehensive services to support children’s education, health, psycho-social wellbeing, and other needs.

Targets and indicators

2. All children receive support to catch up on lost learning.

Challenges : Most children have lost substantial instructional time and may not be ready for curricula that were age- and grade- appropriate prior to the pandemic. They will require remedial instruction to get back on track. The pandemic also revealed a stark digital divide that schools can play a role in addressing by ensuring children have digital skills and access.

Areas of action : The Partners will (i) support the design and implementation of large-scale remedial learning at different levels of education, (ii) launch an open-access, adaptable learning assessment tool that measures learning losses and identifies learners’ needs, and (iii) support the design and implementation of digital transformation plans that include components on both infrastructure and ways to use digital technology to accelerate the development of foundational literacy and numeracy skills. Incorporating digital technologies to teach foundational skills could complement teachers’ efforts in the classroom and better prepare children for future digital instruction.

While incorporating remedial education, social-emotional learning, and digital technology into curricula by the end of 2021 will be a challenge for most countries, the Partners agree that these are aspirational targets that they should be supporting countries to achieve this year and beyond as education systems start to recover from the current crisis.

3. All teachers are prepared and supported to address learning losses among their students and to incorporate digital technology into their teaching.

Challenges : Teachers are in an unprecedented situation in which they must make up for substantial loss of instructional time from the previous school year and teach the current year’s curriculum. They must also protect their own health in school. Teachers will need training, coaching, and other means of support to get this done. They will also need to be prioritized for the COVID-19 vaccination, after frontline personnel and high-risk populations. School closures also demonstrated that in addition to digital skills, teachers may also need support to adapt their pedagogy to deliver instruction remotely.

Areas of action : The Partners will advocate for teachers to be prioritized in COVID-19 vaccination campaigns, after frontline personnel and high-risk populations, and provide capacity-development on pedagogies for remedial learning and digital and blended teaching approaches.

Country level actions and global support

UNESCO, UNICEF, and World Bank are joining forces to support countries to achieve the Mission, leveraging their expertise and actions on the ground to support national efforts and domestic funding.

Country Level Action

1. Mobilize team to support countries in achieving the three priorities

The Partners will collaborate and act at the country level to support governments in accelerating actions to advance the three priorities.

2. Advocacy to mobilize domestic resources for the three priorities

The Partners will engage with governments and decision-makers to prioritize education financing and mobilize additional domestic resources.

Global level action

1. Leverage data to inform decision-making

The Partners will join forces to conduct surveys; collect data; and set-up a global, regional, and national real-time data-warehouse. The Partners will collect timely data and analytics that provide access to information on school re-openings, learning losses, drop-outs, and transition from school to work, and will make data available to support decision-making and peer-learning.

2. Promote knowledge sharing and peer-learning in strengthening education recovery

The Partners will join forces in sharing the breadth of international experience and scaling innovations through structured policy dialogue, knowledge sharing, and peer learning actions.

The time to act on these priorities is now. UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank are partnering to help drive that action.

Last Updated: Mar 30, 2021

- (BROCHURE, in English) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (BROCHURE, in French) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (BROCHURE, in Spanish) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (BLOG) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (VIDEO, Arabic) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (VIDEO, French) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- (VIDEO, Spanish) Mission: Recovering Education 2021

- World Bank Education and COVID-19

- World Bank Blogs on Education

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Teaching and learning in times of covid-19: uses of digital technologies during school lockdowns.

- Department of Basic Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, Autonomous University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain

The closure of schools as a result of COVID-19 has been a critical global incident from which to rethink how education works in all our countries. Among the many changes generated by this crisis, all teaching became mediated by digital technologies. This paper intends to analyze the activities carried out during this time through digital technologies and the conceptions of teaching and learning that they reflect. We designed a Likert-type online questionnaire to measure the frequency of teaching activities. It was answered by 1,403 teachers from Spain (734 primary and 669 secondary education teachers). The proposed activities varied depending on the learning promoted (reproductive or constructive), the learning outcomes (verbal, procedural, or attitudinal), the type of assessment to which the activities were directed, and the presence of cooperative activities. The major result of this study was that teachers used reproductive activities more frequently than constructive ones. We also found that most activities were those favoring verbal and attitudinal learning. The cooperative activities were the least frequent. Finally, through a cluster analysis, we identified four teaching profiles depending on the frequency and type of digital technologies use: Passive, Active, Reproductive, and Interpretative. The variable that produced the most consistent differences was previous digital technologies use These results show that Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) uses are reproductive rather than constructive, which impedes effective digital technologies integration into the curriculum so that students gain 21st-century competencies.

Introduction

When schools were closed in most countries in March 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers had no other option but to change their classrooms into online learning spaces. It was a critical global incident. In research on identity and teacher training ( Tripp, 1993 ; Butterfield et al., 2005 ; Monereo, 2010 ), a critical incident is an unexpected situation that hinders the development of the planned activity and that, by exceeding a certain emotional threshold, puts the identity in crisis and obliges that teachers review their concepts, strategies, and feelings. Thus, these incidents can become meaningful resources for training and changing teaching and learning practices because they allow us to review our deep beliefs ( Monereo et al., 2015 ).

The critical global incident generated by the pandemic forced most teachers to assume virtual teaching where they had to use digital technologies, sometimes for the first time, to facilitate their students’ learning. The closure of schools as a consequence of COVID-19 led to substantial changes in education with profound consequences. Today we know that educational inequalities have widened ( Dorn et al., 2020 ), while students have suffered greater social and emotional imbalances ( Colao et al., 2020 ). In this context, families have also been more involved in the school education of their children ( Bubb and Jones, 2020 ). Moreover, concerning the objectives of this study, it has been necessary to rethink the teaching strategies in the new virtual classrooms. In fact, this research focuses precisely on analyzing the uses that teachers made of the digital technologies or Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) (from now on, we will use this acronym) during the confinement to become familiar with their practices and use them to review their conceptions of teaching and learning.

For several decades, many authors have argued that ICT as educational devices facilitate the adaptation of teaching to each student. Some argue this is because they can promote collaboration, interactivity, the use of multimedia codes, and greater control of learning by the learner (e.g., Jaffee, 1997 ; Collins and Halverson, 2009 ). In this way, their integration in the curriculum would contribute to the acquisition of 21st-century competencies (autonomy, collaboration, critical thinking, and problem-solving) that the OECD ( Ananiadou and Claro, 2009 ) links to the so-called “global competence” that should define the current education ( Ertmer et al., 2015 ).

However, after decades of use of ICT in classrooms, they have not fully achieved their promise to transform teaching and learning processes. The results of a lot of international studies are, in fact, quite discouraging, like those claimed by the PISA studies ( OECD, 2015 ). In its report, the OECD(2015 , p. 3) concludes that “the results also show no appreciable improvements in student achievement in reading, mathematics or science in the countries that had invested heavily in ICT for education.” Thus, Biagi and Loi (2013) found that the more education ICT uses reported, the less learning in reading, mathematics, and science achieved. These data caused even Andreas Schleicher, head and coordinator of PISA studies, to claim that “the reality is that technology is doing more harm than good in our schools today” ( Bagshaw, 2016 ).

These conclusions contrast with the results obtained in most of the experimental research on the effects of ICT on learning. A decade ago, after conducting a second-order meta-analysis of 25 meta-analyses, Tamim et al.(2011 , p. 14) found “a significant positive small to moderate effect size favoring the utilization of technology in the experimental condition over more traditional instruction (i.e., technology-free) in the control group,” a conclusion that is still valid today. Various studies and meta-analyses reflect moderate but positive effects on learning, whether for example from the use of touch screens in preschools ( Xie et al., 2018 ), from cell phones ( Alrasheedi et al., 2015 ; Sung et al., 2015 ) or video games ( Clark et al., 2016 ; Mayer, 2019 ). It has also been found that they favor collaboration in secondary education ( Corcelles Seuba and Castelló, 2015 ) or learning mathematics ( Li and Ma, 2010 ; Genlott and Grönlund, 2016 ), science ( Hennessy et al., 2007 ) or second languages ( Farías et al., 2010 ).

What is the reason for this disagreement between research conducted in experimental laboratories and large-scale studies? Many factors could explain this distance ( de Aldama, 2020 ). But one difference is that the experimental studies have been carefully designed and controlled to promote these forms of learning mentioned above, while the usual work in the classroom is mediated by the activity of teachers who, in most cases, have little training using ICT ( Sigalés et al., 2008 ). Several authors ( Gorder, 2008 ; Comi et al., 2017 ; Tondeur et al., 2017 ) conclude that it is not the ICT themselves that can transform the classroom and learning, but rather the use that teachers make of them. While the experimental studies mostly promote activities that encourage autonomous learning ( Collins and Halverson, 2009 ), the most widespread uses of ICT, as reflected in these international studies with more diverse samples, report other kinds of use whose benefits are more doubtful.

Different classifications of teachers’ use of ICT in the classroom have been proposed in recent years (e.g., Gorder, 2008 ; Mama and Hennessy, 2013 ; Comi et al., 2017 ). Tondeur et al. (2008a) differentiate three types of educational computer use: (a) basic computer skills; (b) use of computers as an information tool, and (c) use of them as a learning tool. Laying aside the acquisition of basic skills related to digital devices, learning is promoted by the last two uses that lead to second-order digital skills related to information management and its conversion into knowledge ( Fulton, 1997 ; Gorder, 2008 ). Thus, the distinction is usually made between two types of use. The first use is aimed at traditional teaching, focused on the transmission and access to information, and usually called teacher-centered use (although perhaps it should be called content-centered use). The second one, called student-centered use, promotes diverse competencies (autonomy, collaboration, critical thinking, argumentation, and problem-solving) and is part of the Global Competence characteristic of 21st-century education ( Ananiadou and Claro, 2009 ; OECD, 2019 , 2020 ). According to Tondeur et al. (2017) , integration of ICT in education requires assuming a constructivist conception of learning and adopting a student-centered approach in which the students manage the information through the ICT instead of, as in the more traditional approach (content-centered), it being the teacher who uses the ICT.

The experimental studies mentioned above show that student-centered approaches improve verbal earning, producing a better understanding of the subjects studied, promoting self-regulation of the learning processes themselves, and generating critical and collaborative attitudes toward knowledge. Thus, Comi et al.(2017 , pp 36–37), after analyzing data from different standardized assessments, conclude: “computer-based teaching practices increase student performance if they are aimed at increasing students’ awareness of ICT use and at improving their navigation critical skills, developing students’ ability to distinguish between relevant and irrelevant material and to access, locate, extract, evaluate, and organize digital information.” Besides, they also found a slight negative correlation between using ICT to convey information and academic performance.

In spite of these better results of adopting student-centered uses, the studies support that the most frequent uses in classrooms are still centered on the teachers, who indeed use ICT as a substitute for other more traditional resources to transmit information ( Loveless and Dore, 2002 ; Sigalés et al., 2008 ; de Aldama and Pozo, 2016 ). Even if what Ertmer (1999) called type I barriers are overcome, related to the availability of these technological resources and the working conditions in the centers, several studies show that there are other types II barriers that limit the use of ICT ( Ertmer et al., 2015 ); in particular, the conceptions about learning and teaching to the extent that they mediate the use of ICT ( Hermans et al., 2008 ).

Different studies have shown that these teachers’ beliefs about learning and teaching are the best predictor of the use made of ICT in the classroom ( Ertmer, 2005 ; Ertmer et al., 2015 ). Most of the work on these beliefs ( Hofer and Pintrich, 1997 , 2002 ; Pozo et al., 2006 ; Fives and Gill, 2015 ) identifies two types of conceptions: some closer to a reproductive vision of learning, which would be related to the teacher or content-centered teaching uses, and others nearer to constructivist perspectives, which promote student-centered teaching uses. Studies show teachers who have constructivist beliefs tend to use more ICT than those with more traditional beliefs ( Judson, 2006 ; Law and Chow, 2008 ; Ertmer et al., 2015 ). They also employ them in a more student-centered way, and their uses are oriented toward the development of problem-solving skills ( Tondeur et al., 2017 ). On the other hand, teachers with more traditional beliefs use them primarily to present information ( Ertmer et al., 2012 ).

However, the relationship between conceptions and educational practices is not so clear and linear ( Liu, 2011 ; Fives and Buehl, 2012 ; Tsai and Chai, 2012 ; Mama and Hennessy, 2013 ; Ertmer et al., 2015 ; de Aldama and Pozo, 2016 ; de Aldama, 2020 ). Many studies show a mismatch between beliefs and practices, above all, when we refer to beliefs closer to constructivism that do not always correspond to constructive or student-centered practices. We can distinguish three types of arguments that explain the mismatches. First, the beliefs seem to be more complex and less dichotomous than what is assumed ( Ertmer et al., 2015 ). The studies comparing beliefs and practices tend to focus on the more extreme positions of the spectrum -reproductive vs. constructive beliefs-, despite research showing they are part of a continuum of intermediate beliefs between both aspects ( Hofer and Pintrich, 1997 , 2002 ; Pérez Echeverría et al., 2006 ). Thus, for example, the so-called interpretive beliefs maintain traditional reproductive epistemological positions. People who have these conceptions think that learning is an exact reflection of reality or the content which should be learned, whereas they also think teaching is mediated by cognitive processes of the learner which are based on his or her activity ( Pozo et al., 2006 ; López-Íñiguez and Pozo, 2014 ; Martín et al., 2014 ; Pérez Echeverría, in press ). Other examples of this belief can be found in the technological-reproductive conception described by Strauss and Shilony (1994) , which is close to a naïve information processing theory.

Second, we must acknowledge that neither teachers’ beliefs nor their educational practices remain stable but vary according to the teaching contexts. As Ertmer et al. (2015) claim, beliefs are not unidimensional, but teachers assume them in varying degrees and with different types of relationships. The teacher’s beliefs seem to be organized in profiles that gather aspects of the different theories about teaching and whose activation depends on the contextual demands ( Tondeur et al., 2008a ; Bautista et al., 2010 ; López-Íñiguez et al., 2014 ; Ertmer et al., 2015 ).

Third, we consider that this multidimensionality of beliefs makes them very difficult to measure or evaluate ( Pajares, 1992 ( Schraw and Olafson, 2015 ; see also Ertmer et al., 2015 ; Pérez Echeverría and Pozo, in press ), so perhaps different studies are measuring different components. For example, many studies focus on explicit beliefs, or “what teachers believe to be true” for learning, and therefore evaluate more the general ideas about what ICT-based education should be. Usually, these statements tend to be relatively more favorable to the advantages mentioned above. In this paper, we have chosen to analyze teachers’ stated practices as a means of addressing specific beliefs about teaching.

In addition to beliefs, other variables have been identified that influence the use of ICTs such as gender, age, educational level, or subject curriculum, with results that are usually inconclusive. Thus, while Mathews and Guarino (2000) found that men were more inclined toward the use of ICTs than women, in other studies no differences were found ( Gorder, 2008 ; Law and Chow, 2008 ). Similarly, other studies ( van Braak et al., 2004 ; Suárez et al., 2012 ) concluded that there was an inverse relationship between the age of the teachers and their interest in ICT, but other studies did not confirm this conclusion ( Gorder, 2008 ; Law and Chow, 2008 ; Inan and Lowther, 2010 ). Finally, the teaching experience gives equally ambiguous results; some papers report a negative relationship ( Mathews and Guarino, 2000 ; Baek et al., 2008 ; Inan and Lowther, 2010 ) while others find no relationship ( Gorder, 2008 ).

The influence of factors like educational level or curriculum subjects has also been analyzed. The data seem to be more conclusive regarding educational level: teachers in secondary education have more favorable attitudes toward ICT than teachers of earlier levels ( Gorder, 2008 ; Vanderlinde et al., 2010 ). However, the data are not so conclusive regarding the influence of curriculum subjects ( Williams et al., 2000 ; Gorder, 2008 ; Vanderlinde et al., 2010 ).

Although it will take time to understand what has happened in teaching during these months, many studies and proposals have analyzed the use of ICT in distance education. We can classify them into three types of research. The first type of analyses has measured the impact of classroom closures on the education of students, many of them focusing on their effects on inequality or the way different countries have dealt with this crisis ( Crawford et al., 2020 ; Reimers and Schleicher, 2020 ; Zhang et al., 2020 ). Second, studies have aimed at proposing principles that should guide the use of ICT in the classroom ( Ferdig et al., 2020 ; Rapanta et al., 2020 ; Sangrà et al., 2020 ). The last ones, which are close to the aims of this study, are focused on how teachers have used ICT for the COVID-19 crisis. Some of these studies have carried out qualitative case analyses in different contexts, institutions ( Koçoğlu and Tekdal, 2020 ; Rasmitadila et al., 2020 ), and even countries ( Hall et al., 2020 ; Iivari et al., 2020 ). However, others have resorted to the use of questionnaires applied to larger samples to inquire about the teaching experience for confined education ( Devitt et al., 2020 ; Luengo and Manso, 2020 ; Tartavulea et al., 2020 ; Trujillo-Sáez et al., 2020 ). These studies have concluded the most common use by teachers was to upload materials to a platform ( Tartavulea et al., 2020 ); the most activities were teacher-centered ( Koçoğlu and Tekdal, 2020 ); or the more constructivist the teachers are, the more ICT use is reported for confined education ( Luengo and Manso, 2020 ).

However, despite these indications, there has been no study that analyzes the activities and uses of ICT in school during confinement. What learning have teachers prioritized in this period? Has it been more oriented toward verbal, procedural, or attitudinal learning? ( Pozo, in press ). Through what activities, either more constructive or reproductive, have these learnings been promoted? Have the ICT been used to assess the accumulation of information or the global competencies in its management? What variables prompt carrying out one type of activity or another? These are some questions that have guided our research and are reflected in the following specific objectives.

1. Identifying the frequency with which Spanish teachers of primary, and compulsory and non-compulsory secondary education carried out activities using ICT during the pandemic, and how some variables influence this frequency (gender, teaching experience, previous ICT use, educational level, and curriculum subjects).

2. Analyzing the type of learning (reproductive or teacher-centered vs. constructive or student-centered) promoted most frequently by these teachers, as well as the influence of the variables mentioned.

3. Analyzing the types of outcomes (verbal learning, procedural learning, or attitudinal learning), assessment, and social organization promoted by the ICT and the possible influence of the mentioned variables.

4. Investigating if different teaching profiles can be identified in the use of ICT, as well as their relationship with the variables studied.

Regarding objective 1, as the contradictory results reviewed in the Introduction showed, it is difficult to sustain a concrete hypothesis. However, in the case of objective 2, as argued in the Introduction, we expect to find a higher frequency of reproductive activities (or teacher-centered) than constructive (student-centered). Along the same lines, concerning the third objective, we hope to find more activities oriented to verbal learning, reproductive assessment, and individual organization of tasks, with few activities based on cooperation between students. Finally, about objective 4, we hope to identify teacher profiles that differ in the frequency and type of activities proposed to their students and that these profiles are related to some of the demographic variables analyzed in the study.

Materials and Methods

Task and procedure.

To achieve these objectives, we designed a questionnaire on ICT through the Qualtrics software and sent telematically to various networks of teachers and primary and secondary education centers in Spain. For the construction of the questionnaire, we consulted different blogs where teachers shared the activities they were applying during the pandemic. The questionnaire was composed of two parts. In the first one, after participants gave informed consent, they were requested to provide personal and professional information (see Table 2 ). The second part comprised 36 items that described different types of teaching activities. Participants were asked to rate how often they carried them out on a Likert scale (1, Never; 2 Some days per month; 3, Some days per week; and 4, Every day). After the analysis of the methodologies carried out in the Introduction, we considered asking teachers what they were doing in their classrooms was the most accurate procedure to know the true practices they were carrying out. On the one hand, we wanted to avoid the bias of classic questionaries on conceptions that require teachers to express their agreement with some beliefs. On the other hand, the analysis of teachers’ actual practices in their classrooms would require a different, more qualitative work, with a smaller sample size.

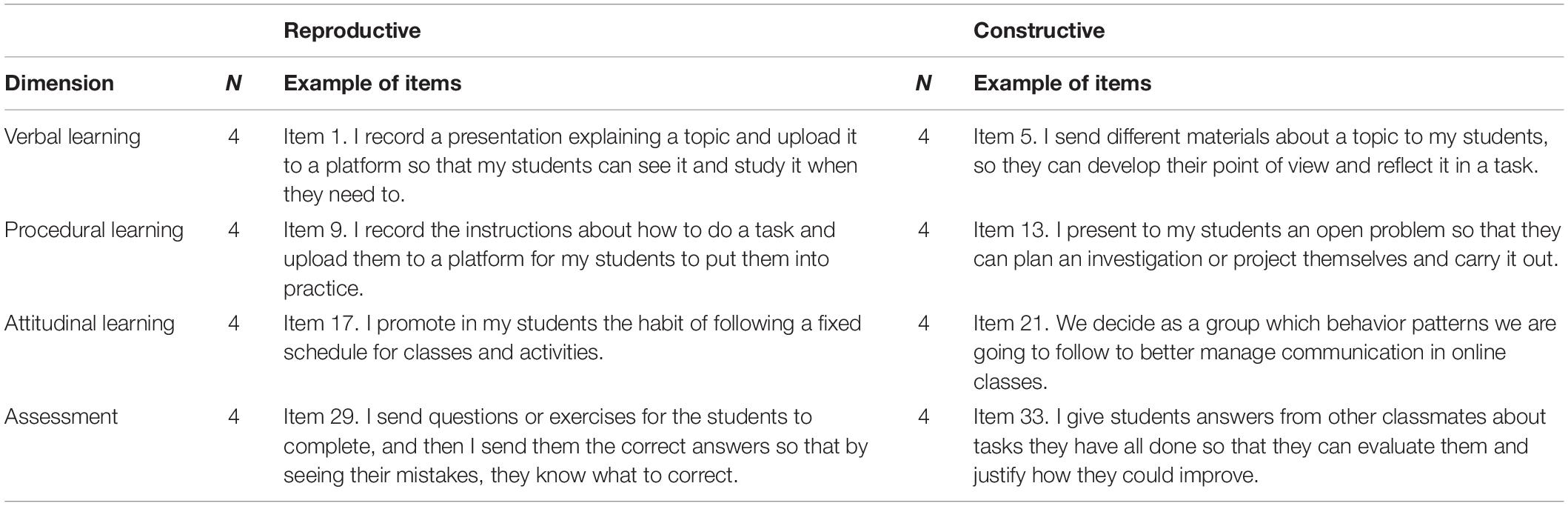

As we show in Table 1 , these activities were directed toward reproductive and constructive learning and different types of learning outcomes (verbal, procedural, and attitudinal), assessment (usually called summative and formative assessment), and cooperative activities.

Table 1. Structure and examples of questionnaire items.

Table 2. Characteristics of the sample and variables.

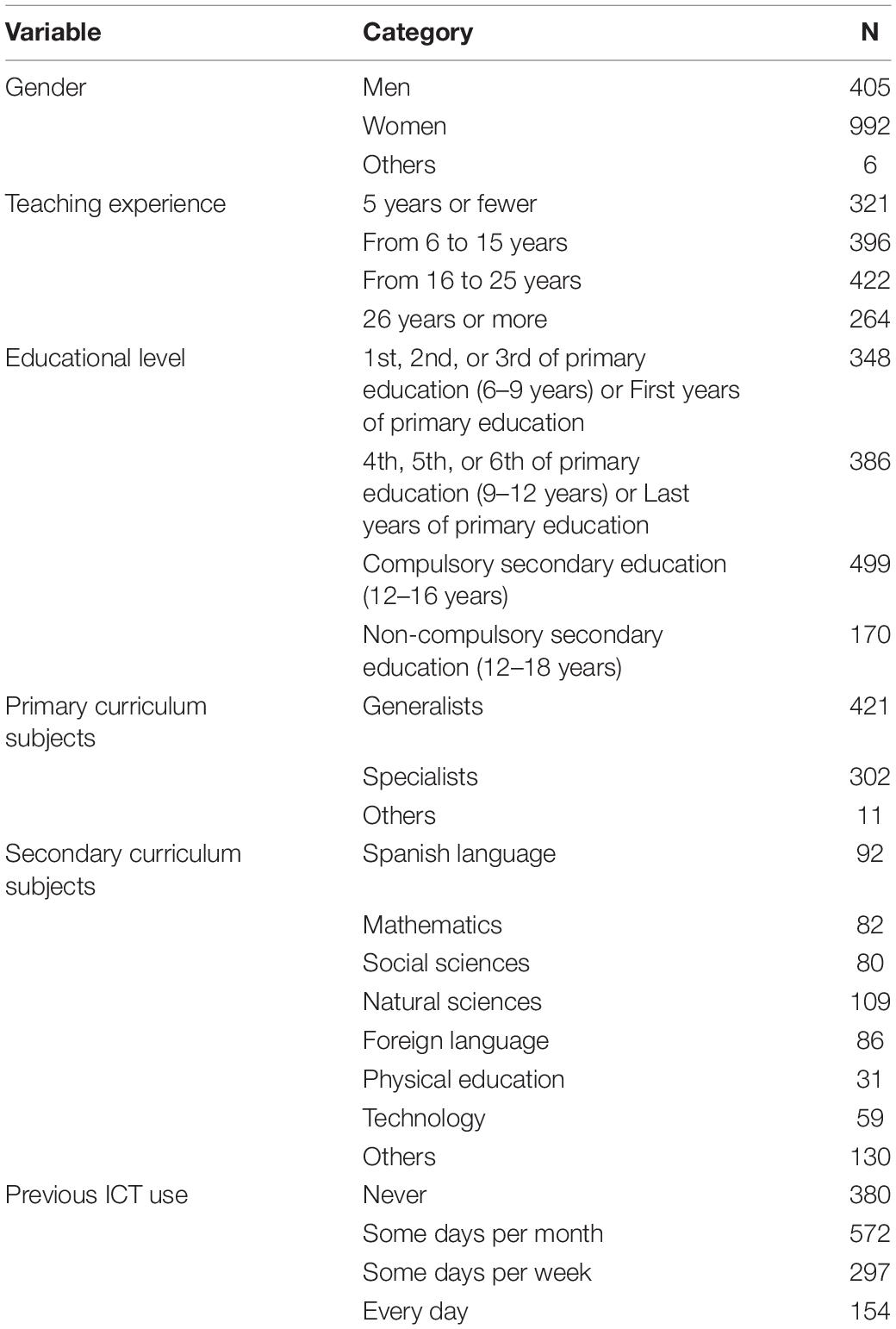

Participants

The participants were primary and secondary education teachers who were working in Spain when they completed the questionnaire. In Spain, compulsory education is from 6 to 16 years. In primary education (6–12 years), a single generalist teacher imparts most of the subjects, while specialist teachers (music, physical education, foreign language, etc.) only attend class during the hours of their subjects. After compulsory secondary education, there is a non-compulsory secondary education (16–18 years old) that is taught in the same centers as compulsory secondary education and by the same teachers.

We used directories of emails from public, private schools, and high schools of Spain to get in contact with the participants. Besides, to encourage participation, we raffled 75 euros for the purchase of teaching materials among all participants. We collected 1,541 answers. We eliminated 52 of them because they belonged to people who were not teachers of primary or secondary education in Spain. Then, we removed 45 participants who completed the questionnaire in less than 5 min, insufficient time to read and complete it, and we excluded 41 participants who indicated the 3rd (“Some days per week”) or 4th option (“Every day”) in over 80% of the items. We argue this exclusion as it is unlikely that a teacher could carry out such a quantity of activities in the span of a week. The questionnaire has 36 activities, so doing over 80% of items with a frequency of a minimum some days per week implies carrying out almost 29 activities per week. We consider this is not possible in the pertaining virtual class context and noted several contradictions in the answers. Therefore, the final sample had 1,403 teachers (see Table 2 ). Note that the sum of all variables does not reach this total because some values were so unusual that they were not considered in the statistical analyses.

Data Analysis

To ensure the consistency of the questionnaire and the dimensions, a reliability analysis was carried out using Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient. The reliability of the scale was 0.90, the reproductive and constructive scales obtained alphas above 0.75, and the verbal, procedural, attitudinal, assessment, and cooperation dimensions got alphas above 0.65.

The 1, 2, and 3 objectives were analyzed with one and two-factor ANOVA. These factors can be both repeated measures and completely randomized, according to the characteristics of the variable. Besides, we carried out post hoc analysis in which the Tukey or Bonferroni correction was applied depending on whether the ANOVA was 1 or 2 factors, to see the differences between categories in the ANOVA analyses. However, post hoc analyses were only performed on the ANOVA of the two factors when the interaction effects were significant.

Finally, a cluster analysis was implemented to identify different teaching profiles (objective 4). Once identified, we created contingency tables and their corresponding Corrected Typified Residuals (CTR) to know which variables were related to each profile. Finally, we carried out ANOVA to analyze the differences between profiles according to each of the designed dimensions. All the statistical analyses were carried out using SPPS version 26.

The results are written referring to what the teachers were doing to facilitate reading. However, in all cases, we refer to declared activities.

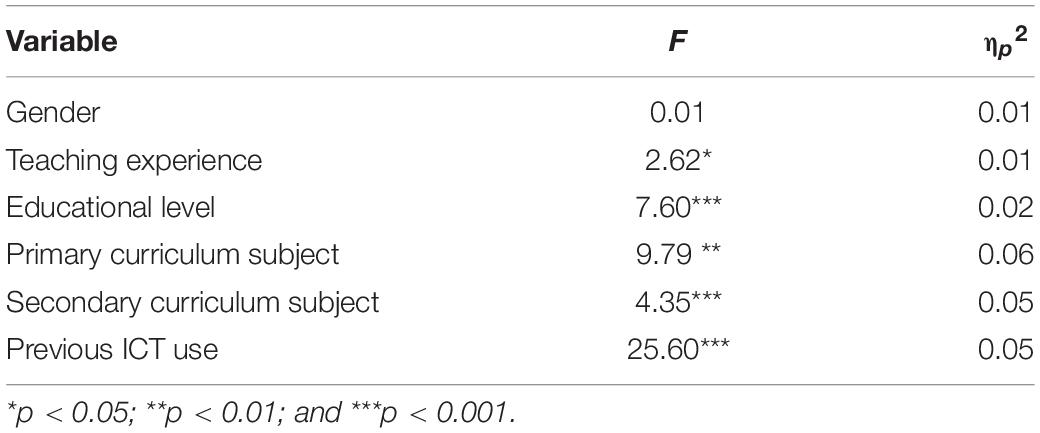

Frequency of Activities Carried Out

Regarding the first objective, teachers performed the activities between Some days per week and Some days per month on average ( M = 2.44, SD = 0.50). However, this frequency varied according to teaching experience, educational level, curriculum subject, and previous ICT use. Gender did not produce differences (see Table 3 ). In the case of teaching experience, according to the post hoc tests, teachers with intermediate experience (from 16 to 25 years) carried out a lower number of activities than novice teachers (5 years or fewer) ( p < 0.05). In turn, teachers who taught children between 6 and 9 years old were also less active than the rest ( p < 0.01). Within primary education, the generalists, who spend more time with the same students, proposed more activities than the specialists ( p < 0.01). In secondary education, the teachers of Spanish language were more active than those of mathematics and physical education ( p < 0.01). Finally, there seems to be a positive linear relationship between previous ICT use and the amount of activity for confined education ( F = 61.66, p < 0.001).

Table 3. Influence of personal and professional variables on the frequency of activities.

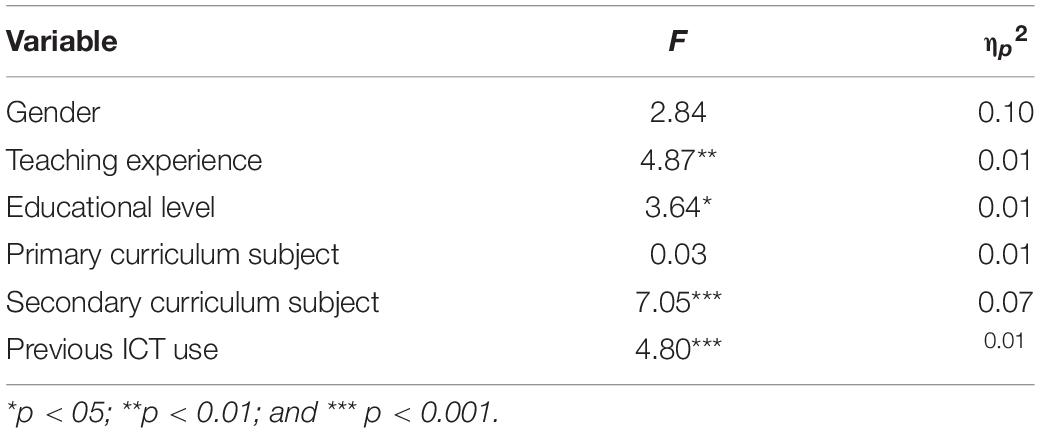

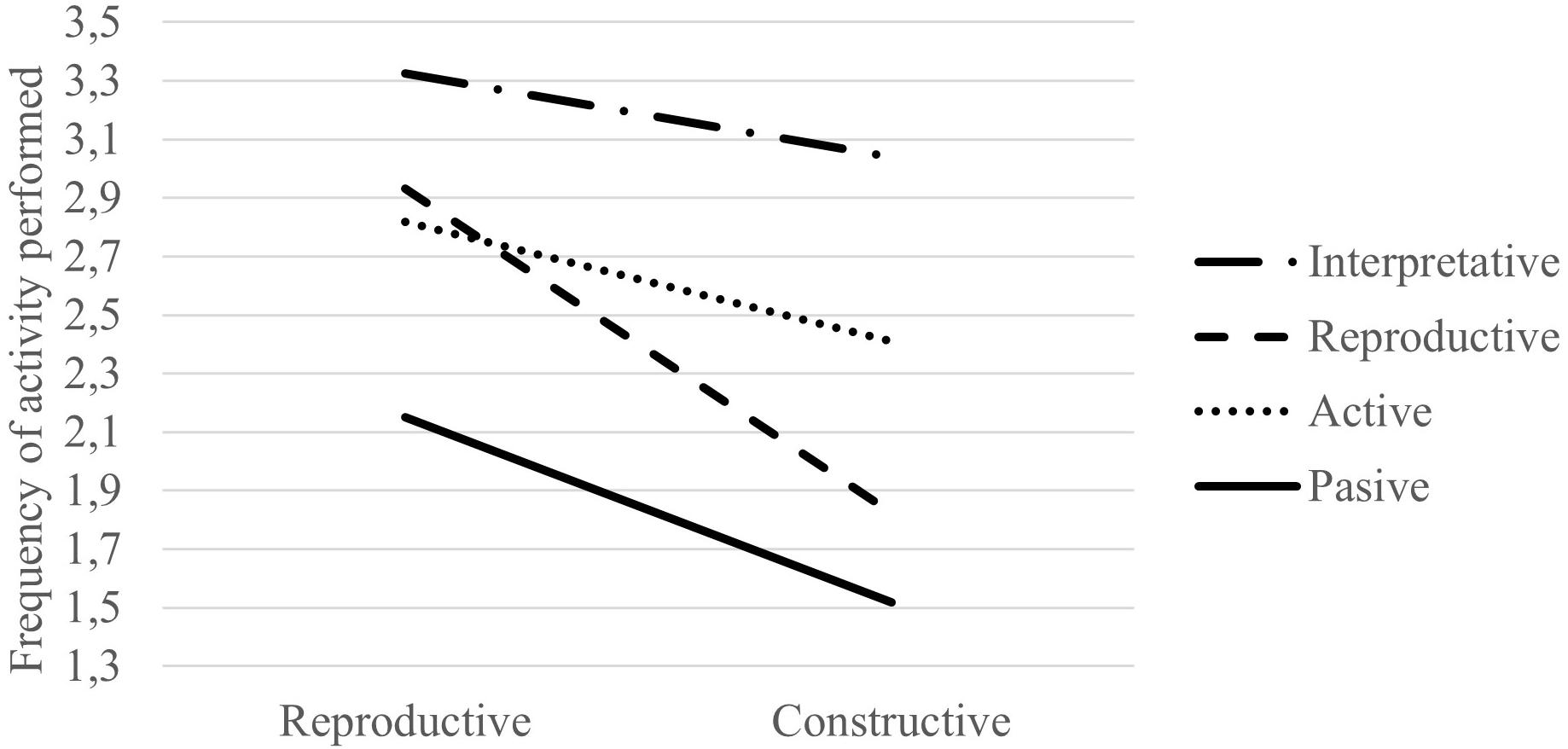

Teaching Activities: Reproductive or Constructive?

Nevertheless, we were not so much interested in the total amount of activities carried out as in the type of learning they promoted (reproductive or constructive). For this, we proposed objective 2. The data was overwhelming. They showed much greater use of reproductive ( M = 2.79, SD = 0.50) than constructive ( M = 2.16, SD = 0.60) learning activities ( F = 2,217.91, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.61). This is the largest and most robust effect size in this study; it occurs in all groups and for all variables ( p < 0.001), although to a different degree, as shown in Table 4 .

Table 4. Influence of the different variables on the type of activity.

Post hoc results reveal that novice teachers (5 years or fewer), the most active group according to the previous analysis, performed more reproductive activities than teachers with experience from 16 to 25 years ( p < 0.01), the least active one. However, the most experienced teachers (more than 25 years) executed more constructive activities than those with intermediate experience (from 16 to 25 years) ( p < 0.05). The teachers of children between 6 and 9 years old did less reproductive and constructive activities ( p < 0.05) than the rest of the groups, with significant differences in all cases except in the case of the teachers of non-compulsory secondary education, who stated less reproductive activities than they did.

In secondary education, the mathematics teachers did less constructive activities than those of Spanish language and social sciences ( p < 0.05). In turn, physical education teachers performed less reproductive activities than the rest of their classmates ( p < 0.01).

Finally, the higher the previous ICT the teachers used, the higher the frequencies indicated by them in both reproductive ( F = 33.57, p < 0.001) and constructive activities ( F = 61.61, p < 0.001). Notwithstanding, the size of the observed effect shows greater differences in the case of constructive activities (reproductive, F = 13.94, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.29, vs. constructive, F = 25.60, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.95).

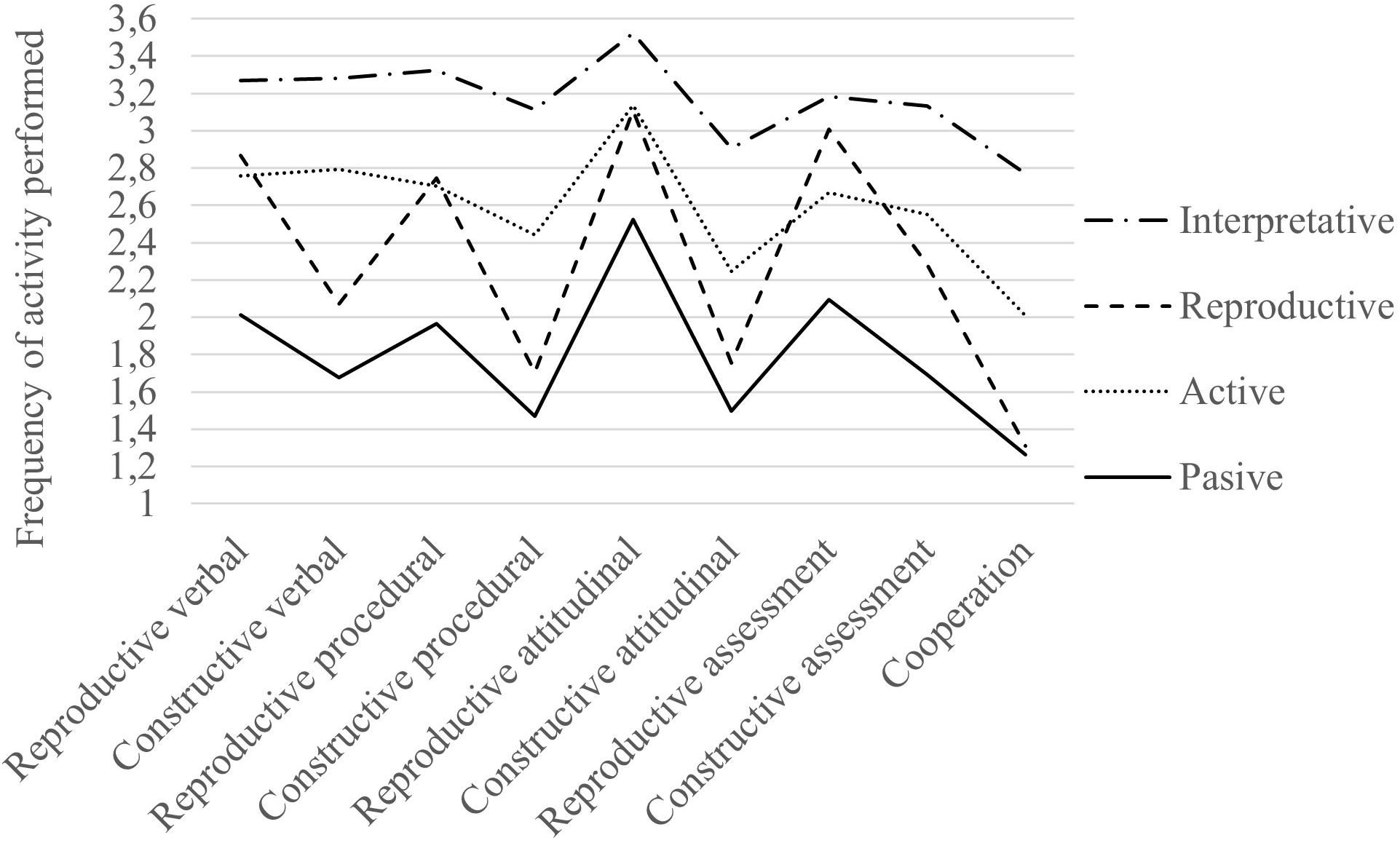

Learning Outcomes, Assessment, and Cooperation Dimensions

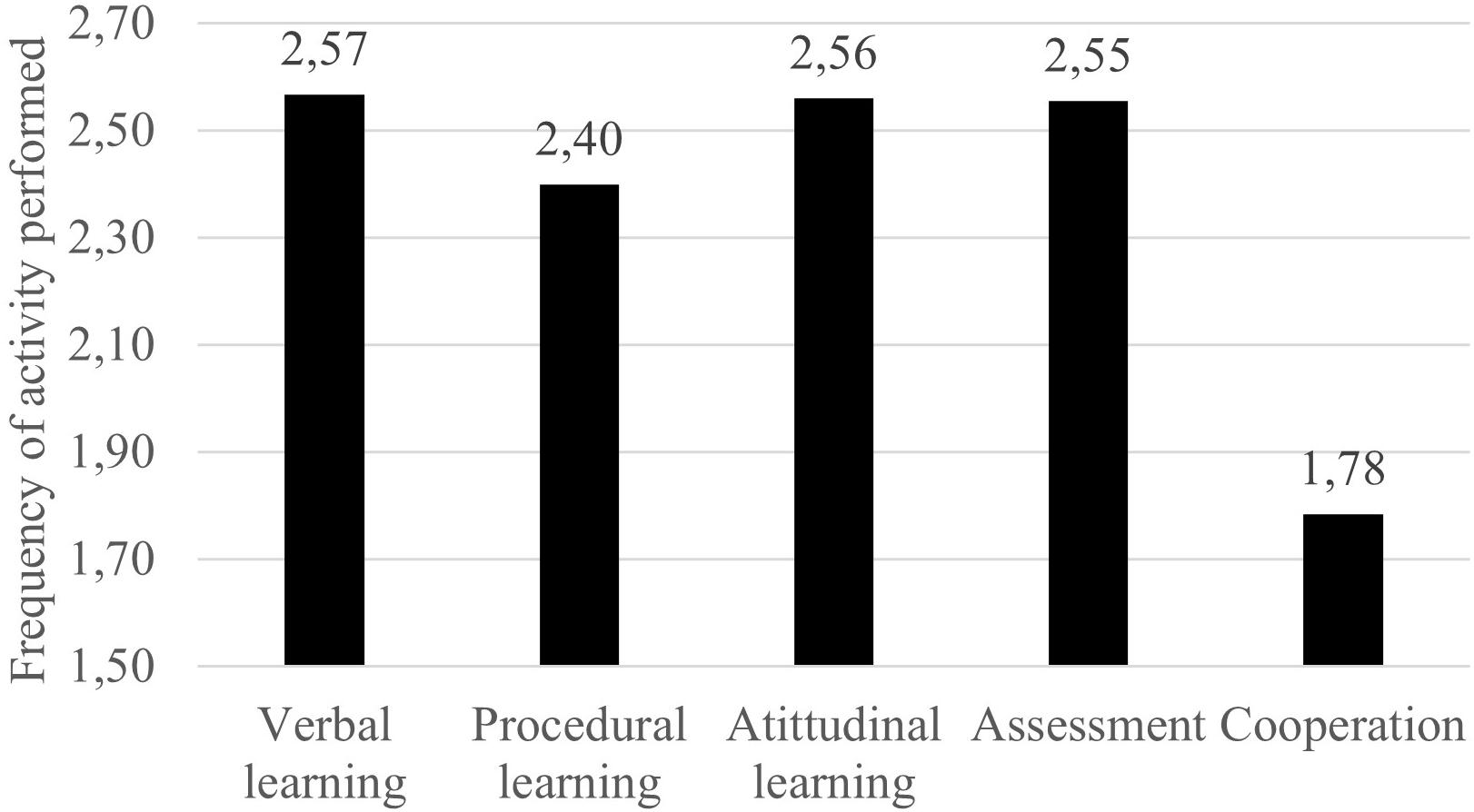

The third objective was to determine what kind of learning outcomes resulted from the activities. As we show in Figure 1 , the teachers focused more on verbal and attitudinal learning than on procedural ( F = 100.11, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.07). On the other hand, the mean responses of the assessment tasks were similar to those of verbal learning and attitudinal learning, but the cooperative activities were less frequent than the remainder ( p < 0.001), performed between never and some days per month ( M = 1.78; SD = 0.74). However, as we see in Table 5 , these results are mediated by the effect of some variables.

Figure 1. Average of the frequencies of each type of activity.

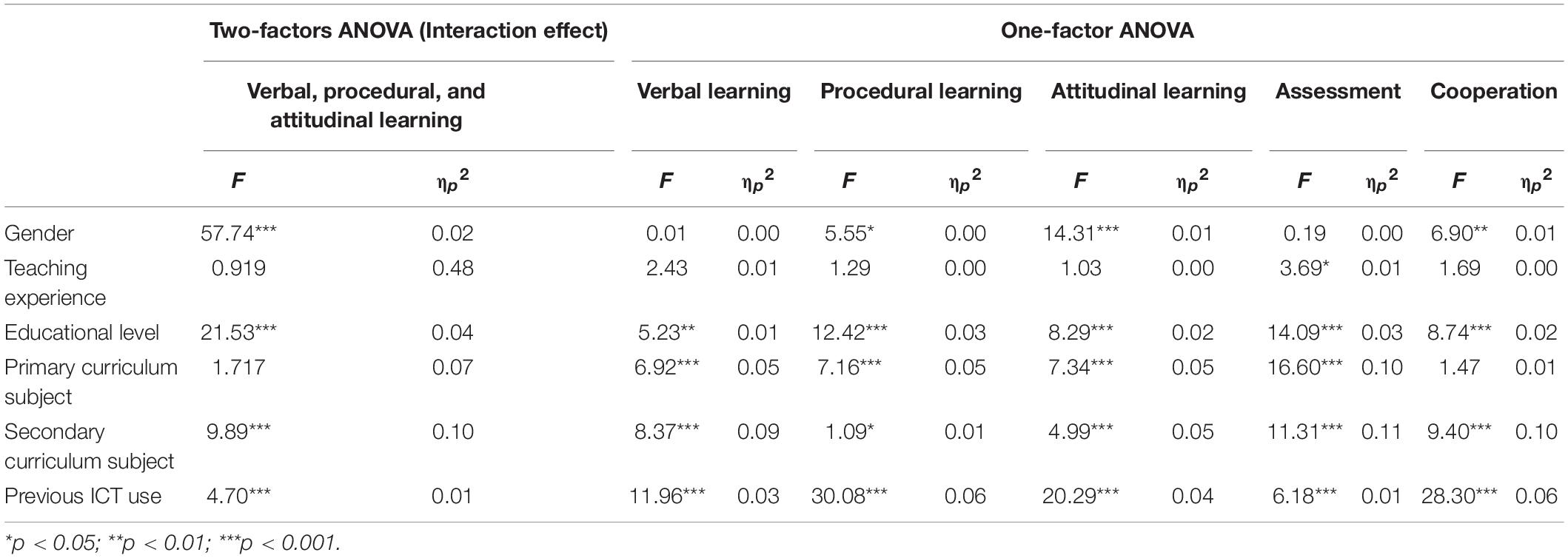

Table 5. Influence of different variables on the frequency of activities for each dimension.

Post hoc analyses show that men carried out more activities focused on procedural learning than women ( p < 0.05), who in turn promoted more activities related to attitudinal learning ( p < 0.001). Men also carried out more cooperation activities than women ( p < 0.01), but there were no differences among them in the Assessment activities. However, the only effect related to teaching experience shows that less experienced teachers (5 years or fewer) carried out more assessment activities than teachers with intermediate experience (from 16 to 25 years) ( p < 0.05).

The teachers of the youngest children (6–9 years old) carried out more activities aimed at attitudinal learning ( p < 0.05) and fewer at procedural learning ( p < 0.01) than the rest of the teachers. Interestingly, the activities aimed at attitudinal learning decreased progressively when the educational level increased, with differences between the upper level of primary education (9–12 years) and secondary education ( p < 0.001). At the same time, the older the students were, the more verbal learning activities they performed, with differences between the first years of primary education (6–9 years) and secondary education (12–18) ( p < 0.05). Besides, the assessment and cooperation activities became more frequent as the educational levels advanced, with differences in both cases between the teachers of the first years of primary education ( p < 0.01) and the last years of primary education and non-compulsory secondary education ( p < 0.05).

In secondary education, verbal learning predominates in almost every subject. However, the Spanish language and foreign language teachers also carried out many activities aimed at attitudinal learning. Only in technology were more activities aimed at procedural learning executed compared to the others ( p < 0.05). At the same time, the mathematics teachers stand out for their little use of cooperation activities. To sum up, the activities aimed at verbal learning increase their frequency when the educational level increases, while attitudinal learning decreases. Nevertheless, the characteristics of each subject have some influence on the increases among educational levels. The cooperation activities also increase, although their frequency is still small. Finally, again, the higher the previous ICT use, the higher the frequency of all activities during the pandemic ( p < 0.001).

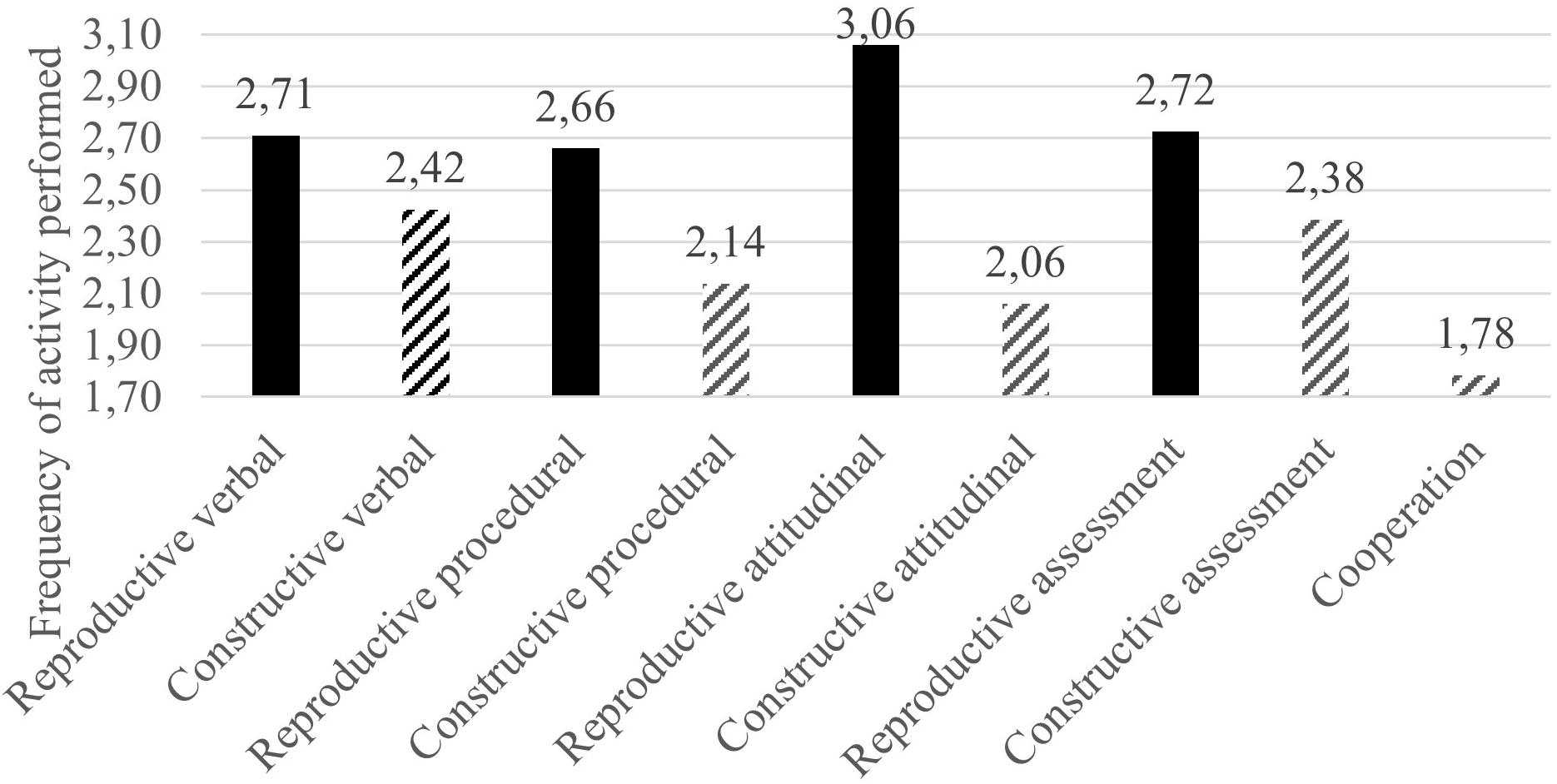

But all these differences become more meaningful when we look at the type of learning (reproductive or constructive) that is promoted by these activities. Again, as we see in Figure 2 , there is a considerable difference between the reproductive and constructive activities regardless of the dimension involved (see Table 6 ), a trend also confirmed by the low frequency of cooperation activities that, by their nature, promote constructive learning. It is remarkable that the highest differences between both scales happen in attitudinal learning. In fact, the most frequent activities in the questionnaire involved attitudinal reproductive learning.

Figure 2. Average of the reproductive and constructive activities in each dimension.

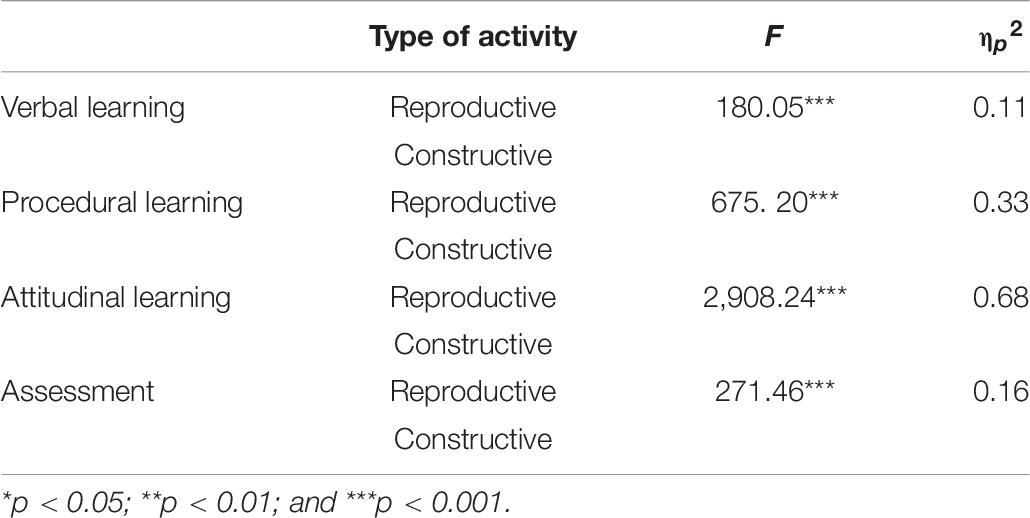

Table 6. Differences between reproductive and constructive activities in the dimensions.

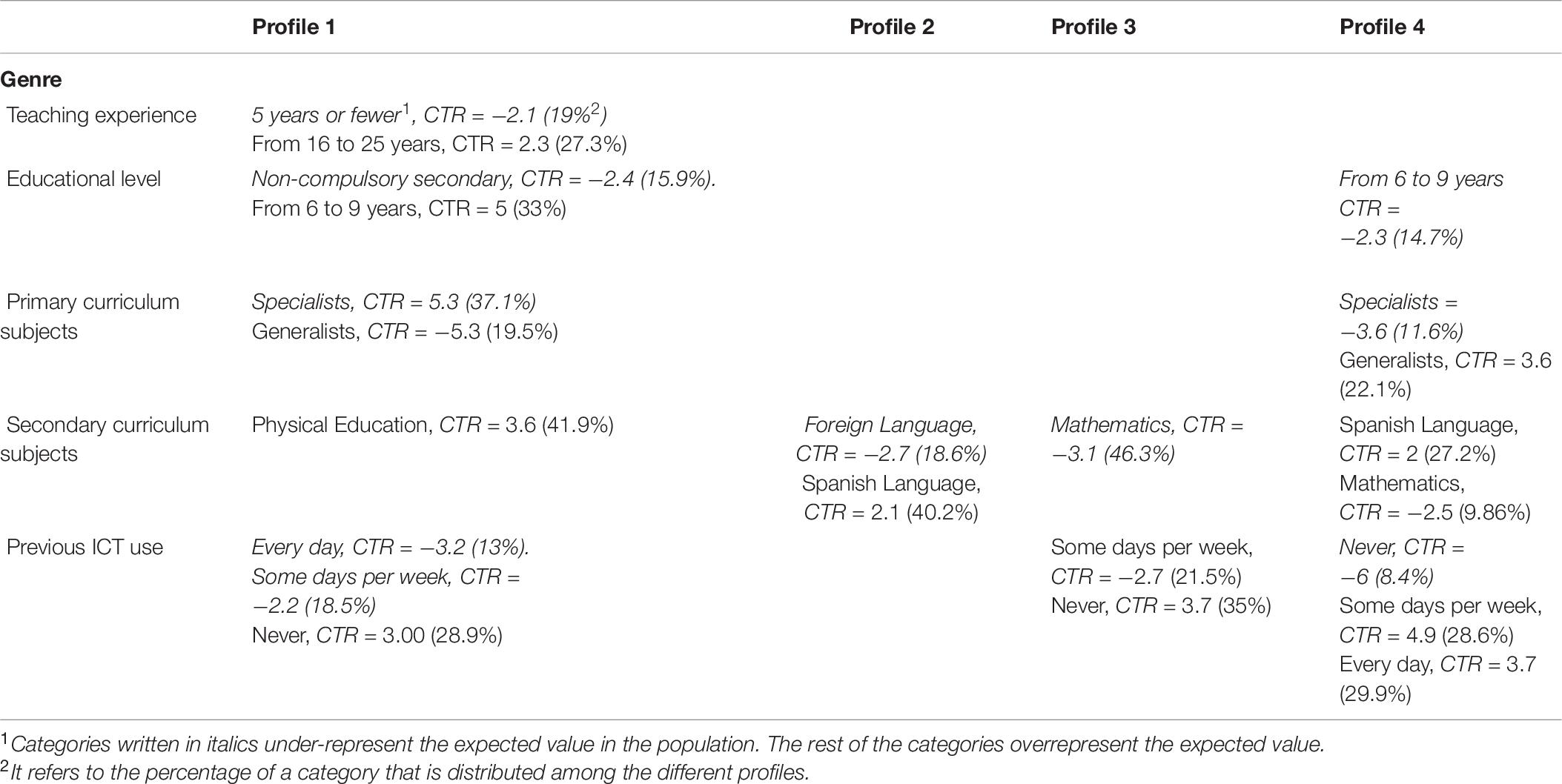

Profiles of Teachers in the Use of ICT

Our final objective was to identify possible profiles in the use of ICT during confined education. For this purpose, we proceeded with a cluster analysis that allowed us to identify different teaching profiles as we showed in Figure 3 . After testing clusters of three centers in which the groups only differed in the number of activities, we executed a four centers cluster, which showed differences in the amount of activity ( F = 2,220.33, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.83) and the mean differences between reproductive and constructive activities ( F = 310.39, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.40).

Figure 3. Frequency of use of reproductive and constructive activities for each teachers’ profile.

• The first profile (“Passive”) was composed of 327 teachers who were characterized by a very low activity (MD = 0.63, SD = 0.02, p < 0.001), essentially reproductive ( M = 2.15, SD = 0.35) and scarcely constructive ( M = 1.52, SD = 0.29).

• The second profile (“Active”) was composed of 424 teachers, was the most numerous. It had a very similar pattern to the previous one, focused mainly on reproductive activities ( M = 2.82, SD = 0.33) rather than constructive ( M = 2.41, SD = 0.21) but with a higher level of activity ( MD = 0.41, SD = 0.02, p < 0.001).

• The third profile (“Reproductive”) was composed of 263 teachers with a similar level of activity to the previous one. However, they have a relatively higher frequency of reproductive activities ( M = 2.93, SD = 0.29) with hardly any constructive activities ( M = 1.82, SD = 0.24).

• The fourth profile (“Interpretative”) which was composed of 389 teachers, was corresponded to the most active teachers. This profile had the smallest differences between reproductive ( M = 3.32, SD = 0.29) and constructive activities ( M = 3.04, SD = 0.31), ( MD = 0.29, SD = 0.02, p < 0.001). According to the terminology used in the introduction, we have called it Interpretative because it integrated both types of activities.

Among the different profiles, we found systematic differences in the dimensions and types of learning. In fact, all differences among profiles were significant ( p < 0.01) except between the Active and Reproductive profiles in verbal, procedural, and attitudinal reproductive learning. There were also no differences between the Passive and Reproductive profiles in cooperative activities because of their low frequency in both groups. On the other hand, teachers in the Interpretive profile carried out more activities in all dimensions than the rest of the groups; the teachers of the Passive profile did fewer tasks than the others (except in the cases already indicated) and finally, the other two profiles maintained an intermediate level of activity, with the difference that the teachers of the Reproductive profile focused almost exclusively on reproductive activities as we see in Figure 4 .

Figure 4. Use of each dimension for each teachers’ profile.

The distribution of teachers in each of the four profiles varied depending on educational level (χ 2 = 29.57, p < 0.001), primary curriculum subjects (χ 2 = 60.97, p < 0.001), secondary curriculum subjects (χ 2 = 60.97, p < 0.001), and previous ICT use (χ 2 = 77.46, p < 0.001). We did not find any relationship with gender or teaching experience, the variables with the least influence in the study.

As we see in Table 7 , the first profile or Passive was over-represented by teachers of children aged 6–9, and teachers of non-compulsory secondary education were under-represented. Between the primary education teachers, specialists predominated, and there were practically no generalist teachers. The only secondary education teachers that appeared in this profile were physical education ones. Finally, there is a significant number of teachers who had not used ICT with their students before the confinement, and there was hardly any representation of those who had most used them.

Table 7. Variables related to each of the profiles.

The second or Active profile is distributed homogeneously way among the different educational levels. It is predominantly formed by secondary education teachers of Spanish language and social sciences. In the third or Reproductive profile, secondary education teachers who taught mathematics, and those who had never used ITC in the classroom were over-represented.

The fourth or Interpretative profile, characterized by integrating reproductive and constructive activities, had hardly any teachers of children from 6 to 9 years old nor specialist teachers of primary education, unlike the first profile. However, this profile included a high number of generalist teachers of primary education and Spanish language teachers of secondary education. On the other hand, it had a few mathematics teachers from secondary education who were over-represented in the Reproductive profile. Finally, the teachers who used ICT more before confinement were also over-represented, and there were hardly any teachers who had not used them.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this study, taking advantage of the critical incident caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, we analyzed the type of activities with ICT that primary and secondary education teachers proposed to their students. Our purpose was to check if, in this context, ICT contributed to promoting more constructive ways of teaching. The most dominant effect of the results, related to the second aim of the study, showed that teachers carried out significantly more activities oriented to reproductive learning than constructive ones. In other words, they preferred teacher-centered activities to student-centered ones. This effect was very robust ( F = 2,217.91, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.61), and it was manifested in all dimensions of the questionnaire, was maintained when we introduced any of the variables studied and was presented in all profiles.

On the other hand, our work has revealed other variables that influence the frequency of ICT use. Thus, we have found that teachers who attend to young children use them less than teachers of older students. These data coincide with those found in other works ( Gorder, 2008 ; Vanderlinde et al., 2010 ) and are probably related to the characteristics of the teaching activity itself. It is undoubtedly more arduous to use ICT in class with young children than with adolescents or adults. We have also found a greater frequency of use by generalists than specialists because the former teach more hours in the same class and consequently have more responsibilities with their students. Both the specialists and the teachers of the youngest children were overrepresented in the Passive profile. Nevertheless, the influence of the subjects taught in compulsory and non-compulsory secondary education is not so clear. We found there was hardly any influence of gender on different results. Data from other studies show that the influence of this variable is quite unstable and varies among studies ( Mathews and Guarino, 2000 ; Gorder, 2008 ; Law and Chow, 2008 ). However, teaching experience seems to influence in another way: whereas less experienced teachers are more reproductive, the more experienced teachers present fewer differences between reproductive and constructive activities. It should be noted that in other studies this variable has also shown ambiguous results ( Mathews and Guarino, 2000 ; Baek et al., 2008 ; Gorder, 2008 ; Inan and Lowther, 2010 ).

The third objective analyzed the learning outcomes that the activities provided, the type of assessment used, and the cooperation that activities promoted. In general, we have seen that teachers performed more verbal and attitudinal learning than procedural. However, in these cases (as well as in the assessment), activities were aimed at reproductive instead of constructive learning. The least frequent activities were cooperative (between never and some days per month), which is consistent with the importance given to reproduction. The salience of verbal learning increased as the higher the educational level was and, in the same way, the attitudinal activities decreased, with hardly any change in the procedural ones.

Considering that these data were collected in Spain when there were strict confinement and social isolation, we would emphasize that the activities related to attitudes were directed at maintaining classroom control in all groups and profiles (but outside the classroom) whereas there was much less frequency of activities focused on getting the ability to managing student attitudes, behavior or self-control during that situation of confinement. This difference suggests that teachers were more concerned about controlling their students’ study habits.

Regarding our fourth objective, we find four profiles of teachers (Passive, Active, Reproductive, and Interpretative). The first two differed only in the amount of total activity performed, while the Reproductive one was characterized by almost exclusively executing reproductive learning activities. Although, as in the previous groups, the Interpretative teachers carried out many reproductive activities, they also carried out constructive activities with considerable frequency. Teachers of children from 3 to 6 years, for whom engaging in the virtual activity is more complicated, abounded in the Passive profile. However, in the Reproductive profile, teachers of mathematics of secondary education predominated. In contrast, in the Interpretative profile, in which there were fewer differences between reproductive and constructive activities, generalists of primary education and teachers of social and natural sciences and Spanish language of secondary education were over-represented. But principally, this profile was over-represented by teachers who had previously used ICT.

In conclusion, it seems the teachers in this study use ICT essentially for presenting different kinds of information ( Tondeur et al., 2008b ) and do not use them as learning tools that help students to build, manage, and develop their knowledge. On the other hand, this study seems to show that teachers’ beliefs are much closer to the reproductive pole than to the constructive one. In this study, beliefs have been inferred through the frequency with which the teachers stated they carried out predetermined activities. In our view, the description of the activities was much closer to the actual practices and theories of the teachers than the results that questionnaires on beliefs could provide us with. For this reason, we expect the mismatch between theories and practices ( Liu, 2011 ; Fives and Buehl, 2012 ; Tsai and Chai, 2012 ; Mama and Hennessy, 2013 ; Ertmer et al., 2015 ; de Aldama and Pozo, 2016 ) was smaller and helped us to discover the true beliefs of teachers when they teach.

We could therefore conclude that, despite all the educational possibilities and all the promises of change in teaching that ICT raise ( Jaffee, 1997 ; Collins and Halverson, 2009 ), teachers have only perceived these tools as informative support. It seems the critical incident caused by the pandemic has not been resolved in the short-term with a change in favor of student-centered activities and content-centered ones continue predominating. Therefore, our data are more consistent with the results of some international mass studies ( Biagi and Loi, 2013 ; OECD, 2015 ) than with the experimental works that analyze how teachers who are previously chosen use ICT ( Tamim et al., 2011 ; Alrasheedi et al., 2015 ; Sung et al., 2015 ; Clark et al., 2016 ; Xie et al., 2018 ; Mayer, 2019 ). However, there is no doubt that the pandemic has contributed to familiarizing teachers with ICT. In our results, previous use of ICT was the variable that produced the most systematic differences in both the frequency of proposed reproductive and constructive activities. In this sense, perhaps the pandemic may have contributed to an increase in teachers’ experience in two of the three educational computer uses described by Tondeur et al. (2008a) : basic computer skills and use of computers as an information tool. Maybe, this fact could contribute in the future to using the third one, the use of ICT as learning tools. However, there are undoubtedly other variables related to first-order and second-order barriers (beliefs) or teacher training with ICT that influence this possibility of change.

In summary, our work shows that activities carried out through ICT during confined schooling were more teacher-centered than student-centered and hardly promoted the 21st-century skills, that digital technologies should facilitate ( Ertmer et al., 2015 ). However, the data also show that the greater the stated previous use of ICT, the greater and more constructive its use was reported for the pandemic. Previous use of ICTs is related not only to beliefs about their usefulness but also to specific training to master these tools and to use them in a versatile manner, adapted to different purposes or objectives. It seems clear that teacher training should be promoted not only to encourage more frequent use of ICT but also to change conceptions toward them to promote constructive learning. In this sense, the forced use of ICT because of COVID-19 will only encourage this change if we support teachers with adequate resources and activities which facilitate reflection on their use.

However, we should consider that one limitation of this study is that the practices analyzed were those declared by the teachers. It would be necessary to complete this study with an analysis of the practices that the teachers really applied and to analyze their relationship with their conceptions of learning and teaching. In fact, we are currently analyzing the actual practices of a sub-sample of the teachers who filled out the questionnaire, taking the profiles found in this work as the independent variable. In future research, it would be necessary to analyze the relationship between student learning and these different teaching practices.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Autonomous University of Madrid. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

J-IP: funding acquisition, project administration, conceptualiza-tion, methodology, supervision, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. M-PE: funding acquisition, conceptualization, methodology, validation, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. BC: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, software, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, and visualization. DLS: conceptualization, methodology, and writing – review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Innovation and Science of Spain (EDU2017-82243-C2-1-R).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our colleagues from SEIACE for their participation in the item dimension task. We would also like to thank Ricardo Olmos for sharing his statistical knowledge with us. Finally, we would like to appreciate Krystyna Sleziaka her support with the translation of this paper.

Alrasheedi, M., Capretz, L. F., and Raza, A. (2015). A systematic review of the critical factors for success of mobile learning in higher education (University Students’ Perspective). J. Educ. Comput. Res. 52, 257–276. doi: 10.1177/0735633115571928

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ananiadou, K., and Claro, M. (2009). 21st Century Skills and Competences for New Millennium Learners in OECD Countries. OECD Education Working Papers, 41. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/218525261154

Bagshaw, E. (2016). The Reality is that Technology is Doing More Harm than Good in our Schools’ says Education Chief. North Sydney, NSW: Sydney Morning Herald.

Google Scholar

Baek, Y., Jung, J., and Kim, B. (2008). What makes teachers use technology in the classroom? Exploring the factors affecting facilitation of technology with a Korean sample. Comput. Educ. 50, 224–234. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2006.05.002

Biagi, F., and Loi, M. (2013). Measuring ICT use and learning outcomes: evidence from recent econometric studies. Eur. J. Educ. 48, 28–42. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12016

Bautista, A., Pérez Echeverría, M. P., and Pozo, J. I. (2010). Music performance teachers’ conceptions about learning and instruction: a descriptive study of Spanish piano teachers. Psychol. Music 38, 85–106. doi: 10.1177/0305735609336059

Bubb, S., and Jones, M. A. (2020). Learning from the COVID-19 home-schooling experience: listening to pupils, parents/carers and teachers. Improv. Sch. 23, 209–222. doi: 10.1177/1365480220958797

Butterfield, L. D., Borgen, W. A., Amundson, N. E., and Maglio, A.-S. T. (2005). Fifty years of the critical incident technique: 1954–2004 and beyond. Qual. Res. 5, 475–497. doi: 10.1177/1468794105056924

Clark, D. B., Tanner-Smith, E. E., and Killingsworth, S. S. (2016). Digital games, design, and learning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 86, 79–122. doi: 10.3102/0034654315582065

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Colao, A., Piscitelli, P., Pulimeno, M., Colazzo, S., Miani, A., and Giannini, S. (2020). Rethinking the role of the school after COVID-19. Lancet Public Health 5:e370. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30124-9

Collins, A., and Halverson, R. (2009). Rethinking Education in the Age of Digital Technology. New York, NY: Teacher’s College Press.

Comi, S. L., Argentin, G., Gui, M., Origo, F., and Pagani, L. (2017). Is it the way they use it? Teachers, ICT and student achievement. Econ. Educ. Rev. 56, 24–39. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2016.11.007

Corcelles Seuba, M., and Castelló, M. (2015). Learning philosophical thinking through collaborative writing in secondary education. J. Writing Res. 7, 157–200. doi: 10.17239/jowr-2015.07.01.07

Crawford, J., Butler-Henderson, K., Rudolph, J., Malkawi, B., Glowatz, M., Burton, R., et al. (2020). COVID-19: 20 countries’ higher education intra-period digital pedagogy responses. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 3, 9–28. doi: 10.37074/jalt.2020.3.1.7

de Aldama, C. (2020). Cognitive enhancement or cognitive diminishing? Digital technologies and challenges for education from a situated perspective. Límite Interdiscip. J. Philos. Psychol. 15:21.

de Aldama, C., and Pozo, J. I. (2016). How are ICT use in the classroom? A study of teachers’ beliefs and uses. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 14, 253–286. doi: 10.14204/ejrep.39.15062

Devitt, A., Bray, A., Banks, J., and Ní Chorcora, E. (2020). Teaching and Learning During School Closures: Lessons Learned. Irish Second-Level Teacher Perspectives. Dublin: Trinity College Dublin

Dorn, E., Hancock, B., Sarakatsannis, J., and Viruleg, E. (2020). COVID-19 and Learning Loss—Disparities Grow and Students Need Help. Chicago, IL: McKinsey & Company.

Ertmer, P. A. (1999). Addressing first-and second-order barriers to change: strategies for technology integration. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 47, 47–61. doi: 10.1007/BF02299597

Ertmer, P. A. (2005). Teacher pedagogical beliefs: the final frontier in our quest for technology integration? Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 53, 25–39. doi: 10.1007/BF02504683

Ertmer, P. A., Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. T., Sadik, O., Sendurur, E., and Sendurur, P. (2012). Teacher beliefs and technology integration practices: a critical relationship. Comput. Educ. 59, 423–435. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.02.001

Ertmer, P. A., Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. T., and Tondeur, J. (2015). “Teachers’ beliefs and uses of technology to support 21st-century teaching and learning,” in International Handbook of Research on Teachers’ Beliefs , eds H. Fives and M. G. Gill (New York, NY: Routledge), 403–418.

Farías, M., Obilinovic, K., and Orrego, R. (2010). Modelos de aprendizaje multimodal y enseñanza-aprendizaj e de lenguas extranjeras [Models of multimodal learning and foreign language teaching-learning]. Univ. Tarraconensis 1, 55–74. doi: 10.17345/ute.2010.2.631

Ferdig, R. E., Baumgartner, E., Hartshorne, R., Kaplan-Rakowski, R., and Mouza, C. (2020). Teaching, Technology, and Teacher Education During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Stories from the Field. Waynesville, NC: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Fives, H., and Buehl, M. M. (2012). “Spring cleaning for the “messy” construct of teachers’ beliefs: What are they? Which have been examined? What can they tell us?,” in APA Educational Psychology handbook: Individual Differences and Cultural and Contextual Factors , Vol. 2, eds K. R. Harris, S. Graham, T. Urdan, S. Graham, J. M. Royer, and M. Zeidner (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 471–499. doi: 10.1037/13274-019

Fives H. and (Eds.) Gill M. G. (2015). International Handbook of Research on Teachers’ Beliefs. New York, NY: Routledge.

Fulton, K. (1997). The Skills Students Need for Technological Fluency. Santa Monica, CA: Milken Exchange on Education Technology.

Genlott, A. A., and Grönlund, Å (2016). Closing the gaps - Improving literacy and mathematics by ICT-enhanced collaboration. Comput. Educ. 99, 68–80. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2016.04.004

Gorder, L. M. (2008). A study of teacher perceptions of instructional technology integration in the classroom. Delta Pi Epsilon J. 50, 63–76.

Hall, T., Connolly, C., Ó Grádaigh, S., Burden, K., Kearney, M., Schuck, S., et al. (2020). Education in precarious times: a comparative study across six countries to identify design priorities for mobile learning in a pandemic. Inform. Learn. Sci. 121, 433–442. doi: 10.1108/ILS-04-2020-0089

Hennessy, S., Deaney, R., Ruthven, K., and Winterbottom, M. (2007). Pedagogical strategies for using the interactive whiteboard to foster learner participation in school science. Learn. Media Technol. 32, 283–301. doi: 10.1080/17439880701511131

Hermans, R., Tondeur, J., van Braak, J., and Valcke, M. (2008). The impact of primary school teachers’ educational beliefs on the classroom use of computers. Comput. Educ. 51, 1499–1509. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2008.02.001

Hofer, B. K., and Pintrich, P. R. (1997). The development of epistemological theories: beliefs about knowledge and knowing and their relation to learning. Rev. Educ. Res. 67, 88–140. doi: 10.3102/00346543067001088

Hofer, B. K., and Pintrich, P. R. (eds) (2002). Personal Epistemology: The Psychology of Beliefs about Knowledge and Knowing. Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Iivari, N., Sharma, S., and Ventä-Olkkonen, L. (2020). Digital transformation of everyday life – How COVID-19 pandemic transformed the basic education of the young generation and why information management research should care? Int. J. Inform. Manag. 55:102183. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102183

Inan, F. A., and Lowther, D. L. (2010). Factors affecting technology integration in K-12 classrooms: a path model. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 58, 137–154. doi: 10.1007/s11423-009-9132-y

Jaffee, D. (1997). Asynchronous learning: technology and pedagogical strategy in a distance learning course. Teach. Sociol. 25, 262–277. doi: 10.2307/1319295

Judson, E. (2006). How teachers integrate technology and their beliefs about learning: is there a connection? J. Technol. Teacher Educ. 14, 581–597.

Koçoğlu, E., and Tekdal, D. (2020). Analysis of distance education activities conducted during COVID-19 pandemic. Educ. Res. Rev. 15, 536–543. doi: 10.5897/ERR2020.4033

Law, N., and Chow, A. (2008). “Teacher characteristics, contextual factors, and how these affect the pedagogical use of ICT,” in Pedagogy and ICT use in Schools Around the World. Findings From the IEA SITES 2006 Study , eds N. Law, W. J. Pelgrum, and T. Plomp (Hong Kong: Springer).

Li, Q., and Ma, X. (2010). A meta-analysis of the effects of computer technology on school students’ mathematics learning. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 22, 215–243. doi: 10.1007/s10648-010-9125-8

Liu, S.-H. (2011). Factors related to pedagogical beliefs of teachers and technology integration. Comput. Educ. 56, 1012–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2010.12.001

López-Íñiguez, G., Pozo, J. I., and de Dios, M. J. (2014). The older, the wiser? Profiles of string instrument teachers with different experience according to their conceptions of teaching, learning, and evaluation. Psychol. Music 42, 157–176. doi: 10.1177/0305735612463772

López-Íñiguez, G., and Pozo, J. I. (2014). Like teacher, like student? Conceptions of children from traditional and constructive teaching models regarding the teaching and learning of string instruments. Cogn. Inst. 32, 219–252. doi: 10.1080/07370008.2014.918132

Loveless, A., and Dore, B. (2002). ICT in the Primary School. Buckingham: Open University Press.

Luengo, F., and Manso, J. (eds) (2020). Informe de Investigación COVID19. Voces de docentes y familias. [Report on COVID19 Investigation. Voices from Teachers and Families]. Madrid: Proyecto Atlántida.

Mama, M., and Hennessy, S. (2013). Developing a typology of teacher beliefs and practices concerning classroom use of ICT. Comput. Educ. 68, 380–387. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2013.05.022

Martín, E., Pozo, J. I., Mateos, M., Martín, A., and Pérez Echeverría, M. P. (2014). Infant, primary and secondary teachers’ conceptions of learning and teaching and their relation to educational variables. Rev. Latinoameric. Psicol. 46, 211–221. doi: 10.1016/S0120-0534(14)70024-X

Mathews, J. G., and Guarino, A. J. (2000). Predicting teacher computer use: a path analysis. Int. J. Inst. Media 27, 385–392.

Mayer, R. E. (2019). Computer games in education. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 70, 531–549. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-102744

Monereo, C. (2010). La formación del profesorado: una pauta para el análisis e intervención a través de incidentes críticos. [Teacher education: a standard for analysis and intervention through critical incidents]. Rev. Iberoameric. Educ. 52, 149–178. doi: 10.35362/rie520615

Monereo, C., Monte, M., and Andreucci, P. (2015). La Gestión de Incidentes Críticos en la Universidad . [Management of critical incidents in university]. Madrid: Narcea.

OECD (2015). Students, Computers and Learning: Making the Connection. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/9789264239555-en

OECD (2019). PISA 2018 results: What Students Know and Can do , Vol. I, Paris: OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/5f07c754-en

OECD (2020). How Prepared are Teachers and Schools to Face the Changes to Learning Caused by the Coronavirus Pandemic? Teaching in Focus 32 , Paris: OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/2fe27ad7-en

Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: cleaning up a messy construct. Rev. Educ. Res. 62, 307–332. doi: 10.3102/00346543062003307

Pérez Echeverría, M. P. (in press). “How teachers and students conceive music education: towards changing mentalities,” in Learning and Teaching Music: A Student-Centered Approach , eds J. I. Pozo, M. P. Pérez-Echeverría, G. Torrado, and J. A. López-Íñiguez (Berlin: Springer).

Pérez Echeverría, M. P., Mateos, M., Scheuer, N., and Martín, E. (2006). “Enfoques en el estudio de las concepciones sobre el aprendizaje y la enseñanza. [Approaches for studying conceptions on learning and teaching],” in Nuevas formas de pensar la enseñanza y el aprendizaje: Las concepciones de profesores y alumnos , eds J. I. Pozo, N. Scheuer, M. P. Pérez Echeverría, M. Mateos, E. Martín, and M. de la Cruz (Barcelona: Graó), 55–94.

Pérez Echeverría, M. P., and Pozo, J. I. (in press). “How to know and analyse conceptions on learning and teaching,” in Learning and Teaching Music: A Student-Centered Approach , eds J. I. Pozo, M. P. Pérez Echeverría, G. López-Íñiguez, and J. A. Torrado (Berlin: Springer).

Pozo, J. I. (in press). “The psychology of music learning,” in Learning and Teaching Music: A Student-Centered Approach , eds J. I. Pozo, M. P. Pérez Echeverría, G. López-Íñiguez, and J. A. Torrado (Berlin: Springer).

Pozo, J. I., Scheuer, N., Pérez Echeverría, M. P., Mateos, M., Martín, E., and de la Cruz, M. (2006). Nuevas Formas de Pensar la Enseñanza y el Aprendizaje. Las Concepciones de Profesores y Alumnos. [New ways of Thinking about Teaching and Learning. Teachers’ and Student’s Conceptions]. Barcelona: Graó.