Healthy Living Guide 2020/2021

A digest on healthy eating and healthy living.

As we transition from 2020 into 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect nearly every aspect of our lives. For many, this health crisis has created a range of unique and individual impacts—including food access issues, income disruptions, and emotional distress.

Although we do not have concrete evidence regarding specific dietary factors that can reduce risk of COVID-19, we do know that maintaining a healthy lifestyle is critical to keeping our immune system strong. Beyond immunity, research has shown that individuals following five key habits—eating a healthy diet, exercising regularly, keeping a healthy body weight, not drinking too much alcohol, and not smoking— live more than a decade longer than those who don’t. Plus, maintaining these practices may not only help us live longer, but also better. Adults following these five key habits at middle-age were found to live more years free of chronic diseases including type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.

While sticking to healthy habits is often easier said than done, we created this guide with the goal of providing some tips and strategies that may help. During these particularly uncertain times, we invite you to do what you can to maintain a healthy lifestyle, and hopefully (if you’re able to try out a new recipe or exercise, or pick up a fulfilling hobby) find some enjoyment along the way.

Download a copy of the Healthy Living Guide (PDF) featuring printable tip sheets and summaries, or access the full online articles through the links below.

In this issue:

- Understanding the body’s immune system

- Does an immune-boosting diet exist?

- The role of the microbiome

- A closer look at vitamin and herbal supplements

- 8 tips to support a healthy immune system

- A blueprint for building healthy meals

- Food feature: lentils

- Strategies for eating well on a budget

- Practicing mindful eating

- What is precision nutrition?

- Ketogenic diet

- Intermittent fasting

- Gluten-free

- 10 tips to keep moving

- Exercise safety

- Spotlight on walking for exercise

- How does chronic stress affect eating patterns?

- Ways to help control stress

- How much sleep do we need?

- Why do we dream?

- Sleep deficiency and health

- Tips for getting a good night’s rest

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- Your Health

- Treatments & Tests

- Health Inc.

Public Health

How health care in the u.s. may change after covid: an optimist's outlook.

John Henning Schumann

Many of the changes in health care that happened during the pandemic are likely here to stay, such as conferring with doctors online more frequently about medication and other treatments. d3sign/Getty Images hide caption

Many of the changes in health care that happened during the pandemic are likely here to stay, such as conferring with doctors online more frequently about medication and other treatments.

With more than one-third of U.S. adults now fully vaccinated against COVID-19, there's growing optimism on many fronts. A majority of states have either lifted health-related restrictions or have announced target dates for doing so.

Already, many clinicians and health policy experts are thinking about what the post-pandemic world will look like.

COVID-19 demonstrated that even in a behemoth industry like health care, change can come quickly when it's necessary. Patients understandably avoided hospitals and clinics because of the risk of viral exposure — leading to quick opportunities for innovation.

For example, the use of telemedicine skyrocketed, and many think it's an innovation that's here to stay. Patients like the convenience — and for many conditions, it's an effective alternative to an in-person visit.

Shots - Health News

Telehealth tips: how to make the most of video visits with your doctor.

Dr. Shantanu Nundy , for one, is optimistic about the future of health care in the U.S. He is a primary care physician practicing just outside Washington, D.C., and the chief medical officer at Accolade, a company that helps people navigate the health care system.

Nundy has bold views, based on his current roles as well as prior positions with the Human Diagnosis Project , a crowd-sourcing platform for collaboration on challenging medical cases, and as a senior health specialist for the World Bank, where his work took him to Africa, Asia and South America.

He spoke with Shots about his new book , Care After Covid: What the Pandemic Revealed Is Broken in Healthcare and How to Reinvent It .

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You seem pretty optimistic about changes to U.S. health care because of the pandemic. What changes or new practices do you think are most likely to stick around?

I am optimistic. Health care has changed more in the past year than during any similar period in modern U.S. history. And it changed for the better.

Doctors and other front-line workers finally started meeting patients where they are: in the community (e.g., at drive-through testing and mass vaccination sites), at home (e.g., with house calls and even hospital-level care at home), and on their devices. Doctors and patients connected in new ways: In my clinic, which serves low-income patients in the Washington, D.C., area, I was given an iPhone for the first time for video and audio visits and found myself messaging with patients between visits to refill medications or follow up on their symptoms.

Psychiatrists Lean Hard On Teletherapy To Reach Isolated Patients In Emotional Pain

Some of these changes will reverse as things get back to normal, but what won't change is the fundamental culture shifts. The pandemic magnified long-standing cracks in the foundation of the U.S. health care system and exposed those cracks to populations that had never witnessed them before. All of us — not just patients with chronic diseases or patients who live at the margin — have the shared experience of trying to find a test or vaccine, of navigating the byzantine healthcare system on our own.

The crisis also exposed just how inequitable the health care system is for Black and brown communities. The numbers don't lie — these populations died of COVID-19 at a rate much higher than their white counterparts. I'm hopeful these shared experiences and revelations have created the empathy and impetus to demand change.

Coronavirus Updates

Studies confirm racial, ethnic disparities in covid-19 hospitalizations and visits.

Your book envisions a care framework that will be "distributed, digitally enabled, and decentralized." Let's take them one at a time. What do you mean by "distributed care?"

"Distributed care" refers to the notion that care should happen where health happens, at home and in the community. We need to redistribute care from clinics and hospitals to homes, pharmacies and grocery stores, barbershops and churches, workplaces and online, where patients are on-the-go. This doesn't mean we should eliminate traditional health care settings. Hospitals and clinics will continue to play a major role in health care delivery, but for most people, these will become secondary, rather than primary, sources of care.

CVS To Offer In-Store Mental Health Counseling

The most obvious upside to distributed care is that it's more affordable. Without the overhead costs of expensive medical facilities, costs decrease. It also has the potential to be more effective and equitable. Our health is largely driven by our behaviors and our environment. By delivering it where we live and work, care can better address the root causes of poor health, including social isolation, poor nutrition, physical inactivity, and mental and emotional distress. Distributed care can also reach communities too far from the nearest clinic or hospital — or who are too distrustful to even step foot in one.

Racial Equity In Vaccination? Dialysis Centers Can Help With That

We already have digitally enabled care to some extent: We use apps, our medical records are electronic, and many of us have now used telemedicine to connect with clinicians. What is your vision of the future of "digitally enabled care?"

"Digitally enabled" refers to the idea that the right role of technology in health care is simply to increase the care in healthcare. ... For a glimpse of what's possible, I'll share my mom's experience during the pandemic. For 25 years, she struggled with Type 2 diabetes (and for the past 10 years, has been on insulin). But faced with all the reports of patients with diabetes having higher rates of COVID-19 complications, she signed up for a virtual diabetes service that was completely different than anything she had tried in the past two decades.

She was shipped a free glucose meter and weighing scale to send her data to her new diabetes care team. She downloaded a mobile app where she did video visits with her doctor — more frequently than she ever had in person — and 24/7 access to a health coach that she sometimes messaged with multiple times per day in the first few weeks of the program. She also was connected with another patient — a gentleman in Chicago who, like my mom, followed an Indian vegetarian diet — to exchange recipes with. The result: Within weeks, my mom lost over 10 pounds and safely got off of insulin. Nearly a year later, she still is.

This Chef Lost 50 Pounds And Reversed Prediabetes With A Digital Program

How do you envision future care that is decentralized? Will U.S. health care become more of a do-it-yourself industry?

"Decentralized care" refers to a model where decisions about care are in the hands of those closest to it, including doctors and patients.

But health care is highly centralized and heavily regulated, and what doctors can d o often comes down to what we can charge insurance companies for.

One example: I had a patient who was in and out of the hospital for heart failure. After one of these hospitalizations, I saw her in-clinic and learned that she didn't have a scale and couldn't afford one. Daily weigh-ins are critical for patients like her, as a few pounds gained can be an indicator of impending heart failure. So, I handed her a $20 bill from my pocket for a scale, and she was never admitted to the hospital again. If our health care system was decentralized, I would be able to get my patients the $20 piece of equipment they need instead of racking up thousands of dollars in expensive medical tests and hospitalizations.

With all of the innovation you foresee, will there be actual market-based competitive pricing reform, or will all of the whistles and bells just drive health care costs inexorably upward?

The type of innovation we need most is true "disruptive innovation." This is a term that gets thrown around liberally, but the real definition refers to products or services that dramatically lower prices and increase quality, much more so than those currently available.

I see two steps we must take to get there: First, we need to stop nibbling around the edges. Often, our solution to, say, Type 2 diabetes, is training doctors in better management or approving a drug that is 1% better (and 200 times more expensive) than what we have now. A truly disruptive innovation is what my mom used: a digitally enabled service that reversed her diabetes and got her off of insulin completely.

Second, we need to get out of our own way. Early on in the pandemic, when we finally allowed patients to test themselves for COVID-19, we still required a doctor to sign off on the test. Patients filled out a questionnaire and a doctor then needed to scan through dozens of forms an hour to approve or reject the test applications (these were almost always approved). That's crazy! Now, we've finally let doctors off the hook, and patients can walk into a CVS or Walgreens to pick up a rapid COVID-19 test over the counter.

What are some ways that your future vision could go off the rails and lead us toward a care system that is less open, less transparent or less patient-centered?

The biggest threat is the continued monopolization of health care. In many parts of the country, there are only one or two large health systems and a few options for health insurance. This drives up prices with little to no benefit for patients or doctors.

Will the lessons of COVID-19 make us more prepared, and our health care system more adept for the next global challenge?

Absolutely. The pandemic has created medicine's greatest generation. By shepherding this country through the crisis, an entire generation of doctors, nurses, pharmacists and administrators learned an entirely new set of skills: public communication, front-line innovation, data-driven decision-making.

An outside force — a new virus — accelerated much-needed change in health care, but the work is just beginning. The future of care is now on us.

John Henning Schumann is a doctor and writer in Tulsa, Okla. He hosts StudioTulsa's Medical Mondays on KWGS Public Radio Tulsa. Follow him on Twitter: @GlassHospital .

- access to health care

- telemedicine

- Health Care

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Nih research matters.

December 22, 2021

2021 Research Highlights — Promising Medical Findings

Results with potential for enhancing human health.

With NIH support, scientists across the United States and around the world conduct wide-ranging research to discover ways to enhance health, lengthen life, and reduce illness and disability. Groundbreaking NIH-funded research often receives top scientific honors. In 2021, these honors included Nobel Prizes to five NIH-supported scientists . Here’s just a small sample of the NIH-supported research accomplishments in 2021.

Printer-friendly version of full 2021 NIH Research Highlights

20210615-covid.jpg

Advancing COVID-19 treatment and prevention

Amid the sustained pandemic, researchers continued to develop new drugs and vaccines for COVID-19. They found oral drugs that could inhibit virus replication in hamsters and shut down a key enzyme that the virus needs to replicate. Both drugs are currently in clinical trials. Another drug effectively treated both SARS-CoV-2 and RSV, another serious respiratory virus, in animals. Other researchers used an airway-on-a-chip to screen approved drugs for use against COVID-19. These studies identified oral drugs that could be administered outside of clinical settings. Such drugs could become powerful tools for fighting the ongoing pandemic. Also in development are an intranasal vaccine , which could help prevent virus transmission, and vaccines that can protect against a range of coronaviruses .

202211214-alz.jpg

Developments in Alzheimer’s disease research

One of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s is an abnormal buildup of amyloid-beta protein. A study in mice suggests that antibody therapies targeting amyloid-beta protein could be more effective after enhancing the brain’s waste drainage system . In another study, irisin, an exercise-induced hormone, was found to improve cognitive performance in mice . New approaches also found two approved drugs (described below) with promise for treating AD. These findings point to potential strategies for treating Alzheimer’s. Meanwhile, researchers found that people who slept six hours or less per night in their 50s and 60s were more likely to develop dementia later in life, suggesting that inadequate sleep duration could increase dementia risk.

20211109-retinal.jpg

New uses for old drugs

Developing new drugs can be costly, and the odds of success can be slim. So, some researchers have turned to repurposing drugs that are already approved for other conditions. Scientists found that two FDA-approved drugs were associated with lower rates of Alzheimer’s disease. One is used for high blood pressure and swelling. The other is FDA-approved to treat erectile dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension. Meanwhile, the antidepressant fluoxetine was associated with reduced risk of age-related macular degeneration. Clinical trials will be needed to confirm these drugs’ effects.

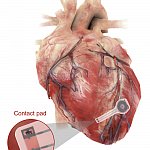

20210713-heart.jpg

Making a wireless, biodegradable pacemaker

Pacemakers are a vital part of medical care for many people with heart rhythm disorders. Temporary pacemakers currently use wires connected to a power source outside the body. Researchers developed a temporary pacemaker that is powered wirelessly. It also breaks down harmlessly in the body after use. Studies showed that the device can generate enough power to pace a human heart without causing damage or inflammation.

20210330-crohns.jpg

Fungi may impair wound healing in Crohn’s disease

Inflammatory bowel disease develops when immune cells in the gut overreact to a perceived threat to the body. It’s thought that the microbiome plays a role in this process. Researchers found that a fungus called Debaryomyces hansenii impaired gut wound healing in mice and was also found in damaged gut tissue in people with Crohn’s disease, a type of inflammatory bowel disease. Blocking this microbe might encourage tissue repair in Crohn’s disease.

20210406-flu.jpg

Nanoparticle-based flu vaccine

Influenza, or flu, kills an estimated 290,000-650,000 people each year worldwide. The flu virus changes, or mutates, quickly. A single vaccine that conferred protection against a wide variety of strains would provide a major boost to global health. Researchers developed a nanoparticle-based vaccine that protected against a broad range of flu virus strains in animals. The vaccine may prevent flu more effectively than current seasonal vaccines. Researchers are planning a Phase 1 clinical trial to test the vaccine in people.

20211002-lyme.jpg

A targeted antibiotic for treating Lyme disease

Lyme disease cases are becoming more frequent and widespread. Current treatment entails the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. But these drugs can damage the patient’s gut microbiome and select for resistance in non-target bacteria. Researchers found that a neglected antibiotic called hygromycin A selectively kills the bacteria that cause Lyme disease. The antibiotic was able to treat Lyme disease in mice without disrupting the microbiome and could make an attractive therapeutic candidate.

20211102-back.jpg

Retraining the brain to treat chronic pain

More than 25 million people in the U.S. live with chronic pain. After a treatment called pain reprocessing therapy, two-thirds of people with mild or moderate chronic back pain for which no physical cause could be found were mostly or completely pain-free. The findings suggest that people can learn to reduce the brain activity causing some types of chronic pain that occur in the absence of injury or persist after healing.

2021 Research Highlights — Basic Research Insights >>

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

Year in review: 2021's key global health moments, according to the WHO

In November 2021, the WHO’s global tobacco trends report found the number of people using tobacco had dropped by 69 million between 2000 and 2020. Image: Unsplash/ Afif Kusuma

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Kate Whiting

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Global Health is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, global health.

- The pandemic might have dominated health headlines this year, but there have been lots of other stories on the World Health Organization’s global health agenda.

- From COVID-19 and malaria vaccines to falling tobacco use, and from dementia to diabetes, these are some of the WHO’s biggest health stories of 2021.

Health topped the news agenda once more in 2021, with ‘Covid vaccine’ the number one Google News search in the UK.

But there were other big health stories throughout the year - and some you might have missed, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

1. COVID-19 vaccine and inequities

More than 8.85 billion vaccination doses had been administered by Christmas 2021, and the WHO had validated 10 COVID-19 vaccines as “safe, effective and high-quality”.

But only a quarter of the health workers in Africa had been fully vaccinated , according to the WHO, showing the divide in access between the developed and developing world.

In 2000, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance was launched at the World Economic Forum's Annual Meeting in Davos, with an initial pledge of $750 million from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

The aim of Gavi is to make vaccines more accessible and affordable for all - wherever people live in the world.

Along with saving an estimated 10 million lives worldwide in less than 20 years,through the vaccination of nearly 700 million children, - Gavi has most recently ensured a life-saving vaccine for Ebola.

At Davos 2016, we announced Gavi's partnership with Merck to make the life-saving Ebola vaccine a reality.

The Ebola vaccine is the result of years of energy and commitment from Merck; the generosity of Canada’s federal government; leadership by WHO; strong support to test the vaccine from both NGOs such as MSF and the countries affected by the West Africa outbreak; and the rapid response and dedication of the DRC Minister of Health. Without these efforts, it is unlikely this vaccine would be available for several years, if at all.

Read more about the Vaccine Alliance, and how you can contribute to the improvement of access to vaccines globally - in our Impact Story .

In December, the WHO’s Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus warned that “blanket booster programmes” risked prolonging the pandemic , as supplies going to rich countries meant greater opportunity for the virus to spread.

There was a huge effort to collaborate on vaccine access, led by the WHO. The ACT-Accelerator halved the cost of COVID-19 rapid tests for low- and lower-middle-income countries, while COVAX delivered more than three-quarters of a billion doses globally.

2. Humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan

Since August, when the Taliban took control of Afghanistan, the country has descended into greater poverty and, besides COVID-19, diarrhoea, dengue, measles, polio, and malaria are affecting the population.

The WHO sent 414 metric tonnes of life-saving medical supplies and helped to vaccinate 8.5 million children against polio.

The country is on the brink of famine, with 98% of Afghans without enough food to eat and a million children at risk of dying from hunger as the winter sets in, according to UNICEF.

3. Universal health coverage

The pandemic is likely to stall 20 years of progress towards Universal Health Coverage , the WHO and the World Bank found.

Even before COVID-19, having to pay for health services was pushing more than half a billion people into extreme poverty.

Childhood immunizations have been disrupted during the pandemic, with 23 million children missing out on routine vaccines in 2020. Services to screen for and treat diabetes, cancer and hypertension were disrupted in more than half of countries surveyed by the WHO between June and October 2021.

“We must build health systems that are strong enough to withstand shocks, such as the next pandemic and stay on course towards universal health coverage,” urged Dr Tedros.

4. Tobacco use in decline

In November 2021, the WHO’s global tobacco trends report found the number of people using tobacco had dropped by 69 million between 2000 and 2020.

There are now 60 countries on track to meet the voluntary global target of a 30% reduction in tobacco use by 2025 - up from only 32 countries two years ago.

5. Violence against women

A third of women - around 736 million - are subjected to physical or sexual violence by an intimate partner or sexual violence from a non-partner, the WHO reported in March 2021.

“Violence against women is endemic in every country and culture, causing harm to millions of women and their families, and has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic,” said Dr Tedros.

“But, unlike COVID-19, violence against women cannot be stopped with a vaccine. We can only fight it with deep-rooted and sustained efforts - by governments, communities and individuals - to change harmful attitudes, improve access to opportunities and services for women and girls, and foster healthy and mutually respectful relationships.”

6. Malaria vaccine

In October, the WHO recommended a malaria vaccine for children for the first time , after a successful pilot scheme in three African countries: Ghana, Kenya and Malawi.

RTS,S - or Mosquirix - is a vaccine developed by British drugmaker GlaxoSmithKline, which acts against P. falciparum, the most deadly malaria parasite globally, and the most prevalent in Africa.

Dr Tedros called it a "historic moment" and a "breakthrough for science, child health and malaria control", that could save tens of thousands of lives a year.

7. Diabetes in the spotlight

To mark the 100th anniversary of the discovery of the life-saving diabetes medicine insulin, the WHO launched a Global Diabetes Compact in 2021 to reduce the risk of diabetes and ensure access to equitable and affordable treatment.

In November, a report showed that insulin remained out of reach for many due to high prices, low availability and few producers dominating the insulin market.

“The scientists who discovered insulin 100 years ago refused to profit from their discovery and sold the patent for just one dollar,” said Dr Tedros. “Unfortunately, that gesture of solidarity has been overtaken by a multi-billion-dollar business that has created vast access gaps.”

Have you read?

3 of this year's most talked-about topics, explained, two years of covid-19: key milestones in the pandemic, who: what you need to know about the new malaria vaccine , 8. the state of dementia.

By 2050, there will be 139 million people living with dementia - more than double the 55 million people living with the disease today, the WHO estimates.

But only a quarter of countries have a national strategy for supporting people with dementia and their families, the WHO reported in September.

“The world is failing people with dementia, and that hurts all of us,” said Dr Tedros. “We need concerted action to ensure that all people with dementia are able to live with the support and dignity they deserve.”

9. Health and climate change

As world leaders prepared to gather in Glasgow for COP26, the WHO launched the Global Air Quality Guidelines , to show how air pollution damages human health.

The WHO and partners also presented a Health Argument for climate action report and an open letter signed by organizations representing two-thirds of the global health workforce.

It said: “The climate crisis is the single biggest health threat facing humanity. As health professionals and health workers, we recognize our ethical obligation to speak out about this rapidly growing crisis that could be far more catastrophic and enduring than the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We urge governments to live up to their responsibilities by protecting their citizens, neighbours, and future generations from the climate crisis. Wherever we deliver care, in our hospitals, clinics and communities around the world, we are already responding to the health harms caused by climate change.”

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Global Health .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Could private provision be the key to delivering universal health coverage?

Gijs Walraven

April 7, 2024

A generation adrift: Why young people are less happy and what we can do about it

Andrew Moose and Ruma Bhargava

April 5, 2024

This gene-editing technology lets scientists cut HIV out of cells

Child deaths have reached a historic low – but there's still much more to do

Amira Ghouaibi

April 2, 2024

Call for action on rising cholera cases, and other health stories

Shyam Bishen

March 28, 2024

Here’s how scientists are studying Parkinson’s disease using robots

COVID-19 Science Update released: October 1, 2021 Edition 107

The COVID-19 Science Update summarizes new and emerging scientific data for public health professionals to meet the challenges of this fast-moving pandemic. Weekly, staff from the CDC COVID-19 Response and the CDC Library systematically review literature in the WHO COVID-19 database external icon , and select publications and preprints for public health priority topics in the CDC Science Agenda for COVID-19 and CDC COVID-19 Response Health Equity Strategy .

Sign up for COVID-19 Science Updates

Section headings in the COVID-19 Science Update have been changed to align

with the CDC Science Agenda for COVID-19 .

PDF version for this update pdf icon [PDF – 1 MB]

Here you can find all previous COVID-19 Science Updates.

Health Equity

Natural History, Reinfection, and Health Impact

PEER-REVIEWED

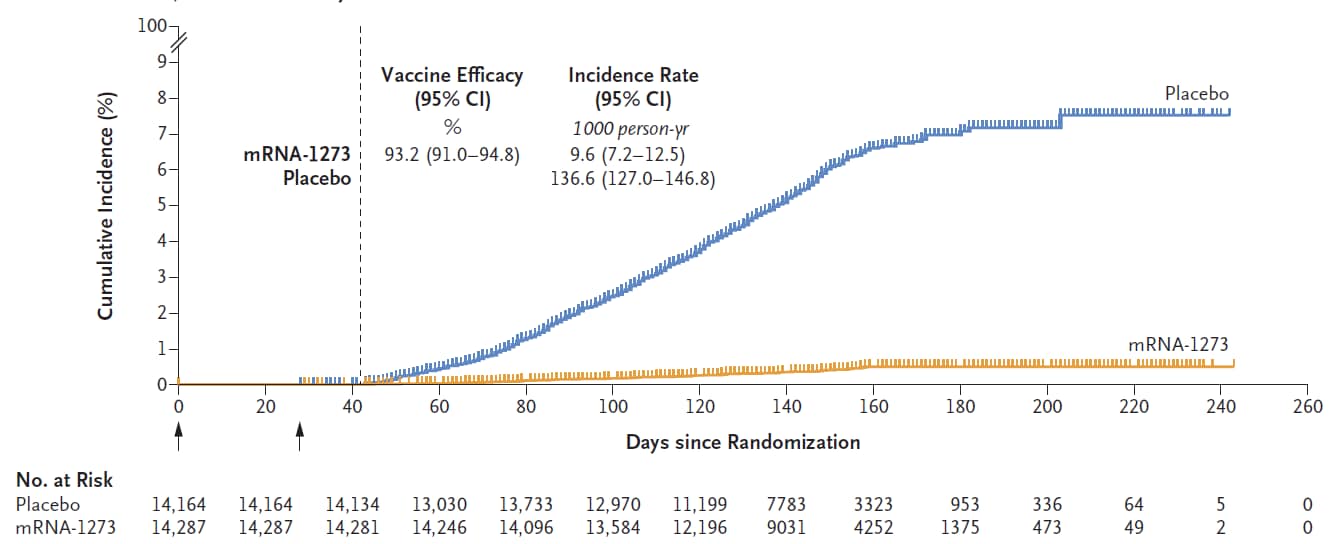

Efficacy of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine at completion of blinded phase external icon . El Sahly et al. NEJM (September 22, 2021).

Key findings:

- COVID-19 was 93.2% (95% CI 91.0-94.8) (Figure).

- Severe disease was 98.2% (95% CI 92.8-99.6).

- VE for preventing COVID-19 ≥4 months after the 2 nd injection was 92.4% (95% CI 84.3-96.8).

Methods : Clinical trial conducted among adults randomized to receive 2 doses of the mRNA-1273 (Moderna) vaccine (N = 15,209) or placebo (N = 15,206). Outcomes of COVID-19, severe COVID-19 illness, and SARS-CoV-2 infection were assessed ≥14 days after the 2 nd dose, as of March 26, 2021; median follow-up time was 5.3 months. Limitations : Key populations (e.g., pregnant women, children, immunocompromised patients) not included; low circulation of Delta variant during trial.

Implications : A 2-dose regimen of mRNA-1273 conferred substantial protection against symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19 illness in adults for at least 4 months.

Note: Adapted from El Sahly et al . Cumulative COVID-19 incidence among participants who received placebo or mRNA-1273 . The dashed vertical line depicts the beginning of the adjudicated assessment of outcomes. From the New England Journal of Medicine, El Sahly et al. , Efficacy of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine at completion of blinded phase. September 22, 2021, online ahead of print. Copyright © 2021 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission from Massachusetts Medical Society.

Effectiveness of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine among U.S. health care personnel external icon . Pilishvili et al. NEJM (September 22, 2021).

- Severe symptoms or hospitalization were more likely among unvaccinated case participants than among partially or fully vaccinated case participants.

- VE was comparable across race and ethnicity, comorbidities, and age.

Methods : Case-control study conducted among 1,482 cases (had SARS-CoV-2 infection) and 3,449 controls (did not have SARS-CoV-2 infection, matched on test date and site) selected from healthcare personnel in acute care hospitals and long-term care facilities in 25 U.S. states, December 2020–May 2021. VE for the BNT162b2 (Comirnaty, Pfizer/BioNTech) and mRNA-1273 (Moderna) vaccines was calculated as 1–(matched OR). Limitations : COVID-19 testing practices varied across sites; vaccinated personnel may have accessed testing differentially than unvaccinated, potentially underestimating VE; persons with unknown prior COVID-19 could not be excluded.

Implications : BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 vaccines prevented symptomatic COVID-19 among frontline healthcare personnel, regardless of demographic characteristics or underlying risk.

PREPRINTS ( NOT PEER-REVIEWED )

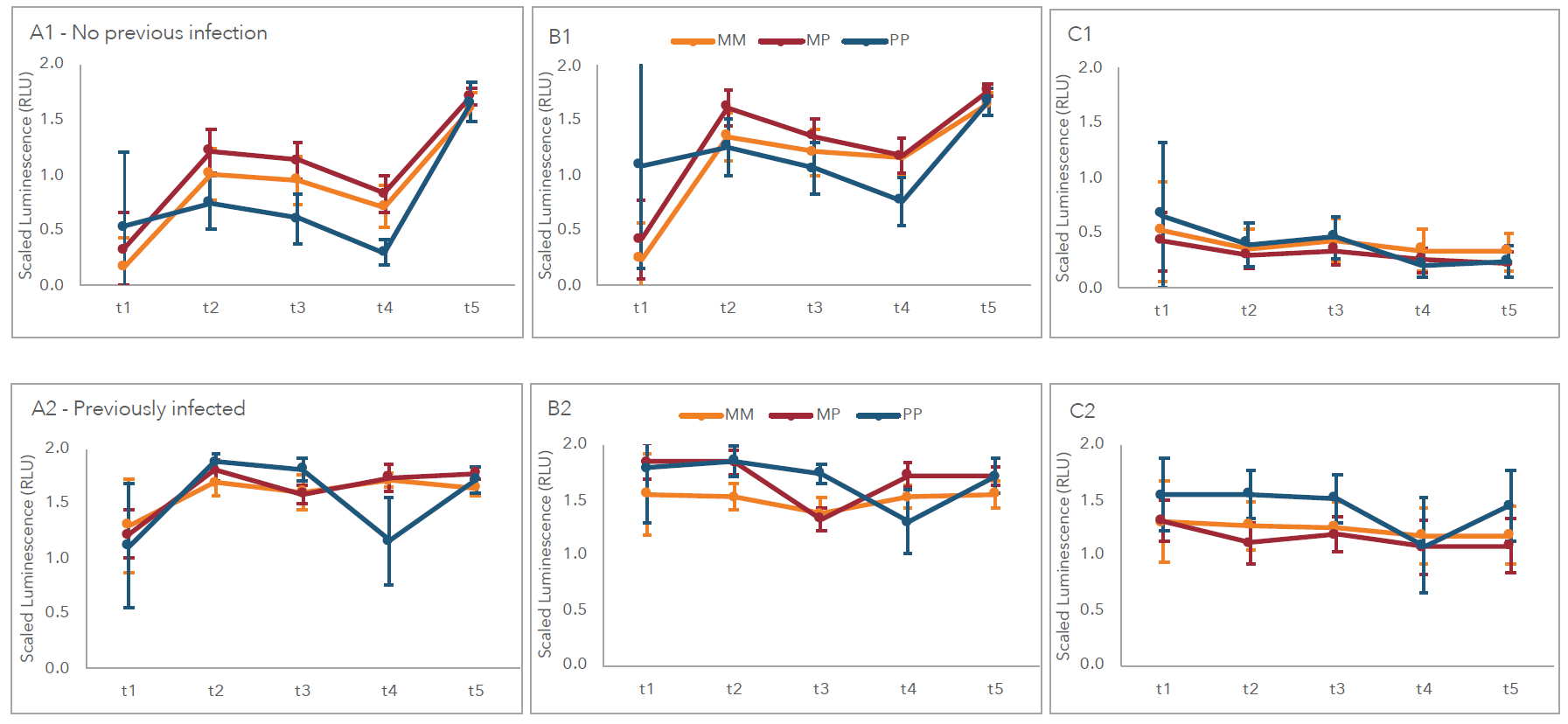

Real-world serologic responses to extended-interval and heterologous COVID-19 mRNA vaccination in frail elderly – interim report from a prospective observational cohort study external icon . Vinh et al. medRxiv (September 21, 2021). Published in The Lancet Healthy Longevity as Real-world serological responses to extended-interval and heterologous COVID-19 mRNA vaccination in frail, older people (UNCoVER): an interim report from a prospective observational cohort study external icon (February 21, 2022).

- Antibody levels at 4 weeks after 2 nd dose did not differ between vaccine recipients of either heterologous or homologous vaccine regimens (Figure).

- Antibody levels by 4 weeks after 2 nd dose were comparable to those of previously infected individuals and did not differ by age, sex, or presence of comorbidities.

Methods : Real-world study among elderly long-term care facility residents in Québec (n = 185) who received 2-dose mRNA vaccines with an extended (16 week) interval between doses. Participants received homologous vaccination (2 doses of either mRNA-1273 [Spikevax/Moderna] or BNT162b2 [Comirnaty, Pfizer/BioNTech]) or heterologous (1 mRNA-1273 dose then 1 BNT162b2 dose) based on availability. IgG responses were measured. Limitations : Clinical outcomes were not evaluated; cellular immune responses were not measured.

Implications : Based on antibody responses, heterologous vaccination might be as effective as homologous vaccination among elderly persons receiving mRNA vaccine.

Note : Adapted from Vinh et al . Antibody responses to homologous ( MM: Moderna/Moderna , PP: Pfizer/Pfizer ) vs. heterologous ( MP: Moderna/Pfizer ) mRNA vaccines based on previous infection status. Top row (A1, B1, C1) no previous infection, bottom row (A2, B2, C2) previously infected. Antibody responses to receptor binding domain (A), S-protein (B), or N antigen (C). t1: baseline, t2: 4 weeks after 1 st dose, t3: 6–10 weeks after 1 st dose, t4: 16 weeks after 1 st dose, t5: 4 weeks after 2 nd dose. Licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0.

COVID-19 in the Phase 3 trial of MRNA-1273 during the Delta-variant surge external icon . Baden et al. medRxiv (September 22, 2021). Published in NEJM as Phase 3 trial of mRNA-1273 during the Delta-variant surge external icon (December 23, 2021).

- Reductions in the rate of infection were more pronounced in persons aged <65 years, but reductions in the rate of severe illness were more pronounced among persons aged ≥65 years.

Methods : Using data from the randomized Coronavirus Efficacy (COVE) mRNA-1273 vaccine trial, rates of COVID-19 and severe COVID-19 illness were assessed during July 1–August 27, 2021 in an intention-to-treat analysis. Outcomes among adult participants vaccinated earlier (July–December 2020; N = 14,746) were compared to those vaccinated more recently (December 2020–April 2021; N = 11,431). Limitations : Short follow up time (2 months).

Implications : During the months when Delta was the dominant COVID-19 variant, rates of COVID-19 and severe illness were lower among persons who were more recently vaccinated. Reevaluation after longer follow-up is needed.

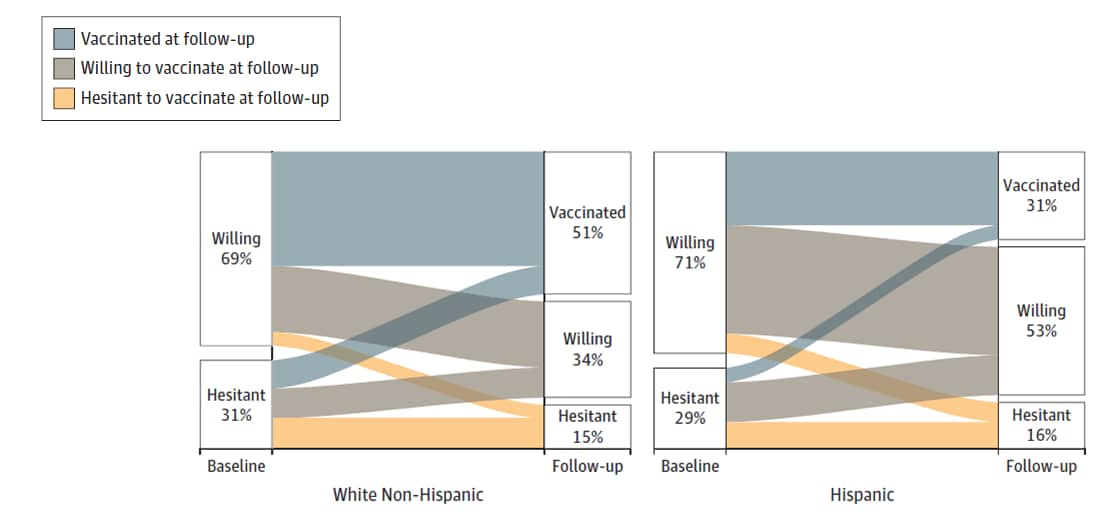

Trajectory of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy over time and association of initial vaccine hesitancy with subsequent vaccination external icon . Siegler et al. JAMA Network Open (September 24, 2021).

- Among participants hesitant to vaccinate at baseline, 32% reported receiving 1 or more vaccine doses, 37% reported being likely to be vaccinated, and 32% remained unlikely to be vaccinated at follow-up.

- Vaccine willingness at baseline was similar for Hispanic/Latino and non-Hispanic White participants (71% vs. 69%), but Hispanic/Latino participants had lower vaccination rates at follow-up (31% vs. 51%; Figure).

- Vaccination was confirmed with antibody test results (94.8% sensitivity; 99.1% specificity), suggesting self-reported vaccination status is a valid metric.

Methods : Cohort study of 3,439 U.S. respondents who completed surveys at baseline (August 9–December 8, 2020) and follow-up (March 2–April 21, 2021) to measure vaccine hesitancy, and who self-collected biological specimens to measure antibody response. Limitations : Follow-up period ended before vaccines were available to all respondents.

Implications : Vaccine hesitancy declined in this sample. However, differences in vaccination by socio-demographic characteristics pose challenges to overall vaccination coverage and achievement of health equity, and also suggest potential barriers to vaccination.

Note : Adapted from Siegler et al . Alluvial plot paths from hesitancy at baseline (August 9–December 8, 2020) to vaccination status ( vaccinated , willing , hesitant ) at follow-up (March 2–April 21, 2021) among a national, weighted sample of 3,439 U.S. respondents by race and ethnicity. Licensed under CC BY.

Two articles this week describe disparities in vaccination rates in Illinois communities. One article assesses the role of income and race/ethnicity in vaccination coverage; the other examines the impact of vaccination inequality on COVID-19 severity.

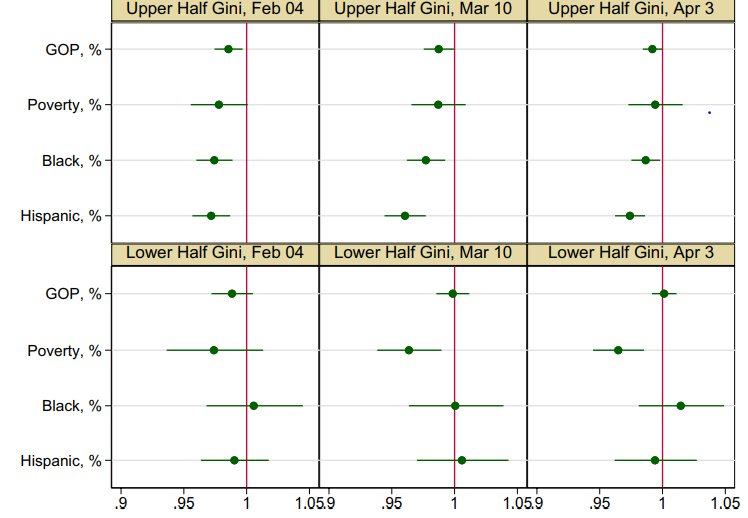

A. Social and economic inequality in coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination coverage across Illinois counties external icon . Liao. Scientific Reports (September 16, 2021).

- Among Illinois counties with higher income inequality, higher percentages of either Black or Hispanic/Latino populations were consistently associated with lower odds of full vaccination in the county (Figure).

- Among Illinois counties with lower income inequality, greater poverty among county residents was associated with lower odds of full vaccination in the county during March–April 2021 (Figure).

Methods : Ecological county-level analysis of socioeconomic factors and vaccination coverage in 51 Illinois counties in 3 waves on February 4, March 10, and April 3, 2021; data were stratified by county income inequality as calculated by median Gini index. Limitations : Study conducted during early phases of vaccination distribution; findings may not be generalizable to communities in other U.S. states.

Note: Adapted from Liao. Odds ratios (95% CI) of a county being fully vaccinated by county-level political affiliation, poverty, and race and ethnic composition, stratified by income inequality (upper half Gini indicates higher income inequality, lower half Gini indicates lower income inequality). Estimates adjusted for county population density, percent population aged ≥65 years, percent male, and percent uninsured. GOP = Republican. Licensed under CC BY 4.0

B. Consequences of COVID-19 vaccine allocation inequity in Chicago external icon . Zeng et al. medRxiv (September 23, 2021).

- The percentage of Chicago residents identifying as non-Hispanic/Latino Black was 80% in the least vaccinated ZIP codes and 8% in ZIP codes with highest vaccination coverage.

- 72% of deaths among Chicago residents in ZIP codes with the lowest quartile of vaccination coverage could have been prevented if vaccination coverage was similar to vaccine coverage in the highest quartile ZIP codes.

Methods : Ecological ZIP code-level analysis of COVID-19-associated cases, deaths, and 1 st -dose vaccination coverage (as of March 28, 2021) in Chicago, August 2020—June 2021. ZIP codes were grouped by (1) lowest quartile of vaccine coverage, (2) middle 2 quartiles, and (3) highest quartile. Limitations : Population characteristics of ZIP codes can be heterogenous; ecological design limits controlling for individual-level factors.

Implications for Liao and Zeng et al. : Communities in Chicago and other Illinois counties experienced unequal COVID-19 vaccine coverage. Reducing disproportionate morbidity and mortality from COVID-19 may require vaccination strategies that are informed by community social and economic needs.

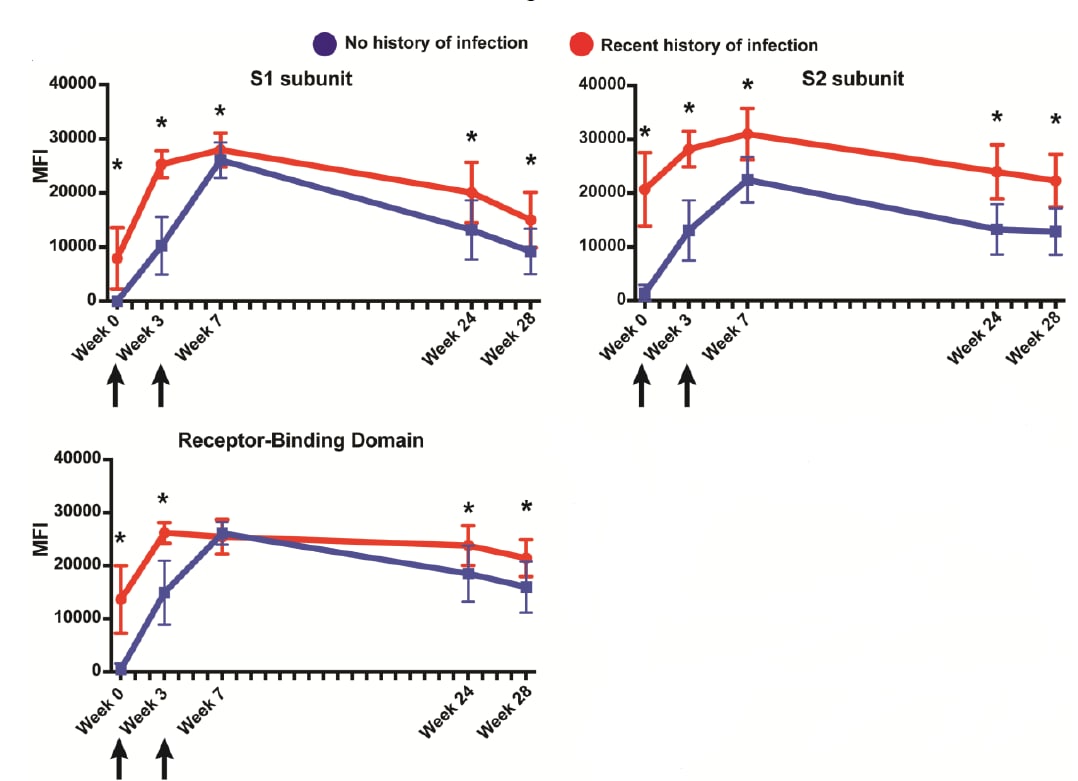

Prior infection and age impacts antibody persistence after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. external icon Fraley et al. Clinical Infectious Diseases (September 22, 2021).

- Higher antibody levels were observed among vaccinated healthcare workers (HCWs) with recent SARS-CoV-2 infection compared with vaccinated HCWs without prior infection (Figure).

- Among HCWs without prior SARS-CoV-2 infection, persons aged 18–49 years had higher antibody response at week 3 (2 nd vaccination dose) and week 28 (~7 months following 1 st vaccination dose), compared with persons aged ≥50 years.

Methods : Among 188 HCWs fully vaccinated with BNT162b2 (Comirnaty, Pfizer/BioNTech), antibody levels up to 28 weeks after the 1 st vaccine dose among HCWs with SARS-CoV-2 infection 30–60 days prior to vaccination were compared with levels among HCWs without prior infection. Limitations : Did not examine SARS-CoV-2 infection >60 days before vaccination.

Implications : Magnitude and duration of antibody response and protection from vaccination may be higher among those with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection and younger persons, which could inform ideal timing of booster vaccination.

Note: Adapted from Fraley et al. Antibody levels for SARS-CoV-2 spike subunit 1 (S1), spike subunit 2 (S2), and receptor-binding domain over time among vaccinated HCWs with a recent SARS-CoV-2 infection and those without prior infection . Week 0 = 1 st vaccination dose; week 3 = 2 nd vaccination dose; MFI = Median Fluorescent Intensity; *indicates p <0.05. Used by permission of the Infectious Diseases Association of America and Oxford University Press.

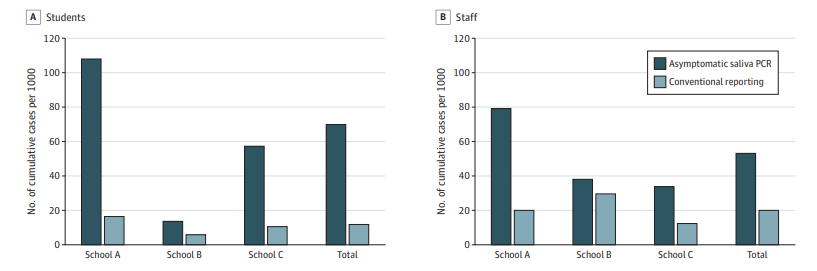

Assessment of a program for SARS-CoV-2 screening and environmental monitoring in an urban public school district. external icon Crowe et al. JAMA Network Open (September 22, 2021).

- 46 individuals were found to have SARS-CoV-2 and 2 clustering events were identified through genome sequencing.

- Participating schools detected SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater samples.

Methods : Evaluation of a school-based weekly saliva PCR COVID-19 testing and environmental monitoring (wastewater, air, surface) pilot program in 3 Omaha, NE public schools (November 9–December 11, 2020); 773 in-person students and faculty were included. Genome sequencing conducted on positive saliva samples. Limitations : Findings may not be generalizable to other schools; incomplete testing among students may underestimate findings; conducted before vaccines were available.

Implications : Routine COVID-19 testing and environmental monitoring may be an effective school-based strategy to rapidly identify SARS-CoV-2 infections and enable implementation of risk-mitigation plans.

Note : Adapted from Crowe et al . Cumulative SARS-CoV-2 case rates detected by weekly saliva PCR testing. Comparing in-person school pilot program ( asymptomatic saliva PCR ) and conventional reporting for A) students and B) staff. Licensed under CC BY.

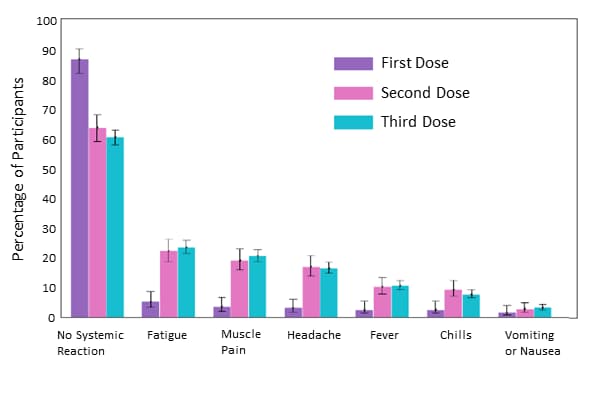

- Self-reported and physiological reactions to the third BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 (booster) vaccine dose external icon . Mofaz et al. medRxiv (Preprint; September 21, 2021). In a prospective observational study in Israel, self-reported reactions and biometrics were recorded for Israeli adults who received ≥1 of 3 doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine. Reactions were similar following the 2 nd and 3 rd doses, and were more frequent than after the 1 st dose. Reactions after the 3 rd dose were more common in participants who were aged <65 years, female, and had no underlying medical conditions.

Note: Adapted from Mofaz et al . Percentage of adults reporting symptoms following the first , second or third dose of Pfizer BNT162b2 vaccination. Used by permission of authors.

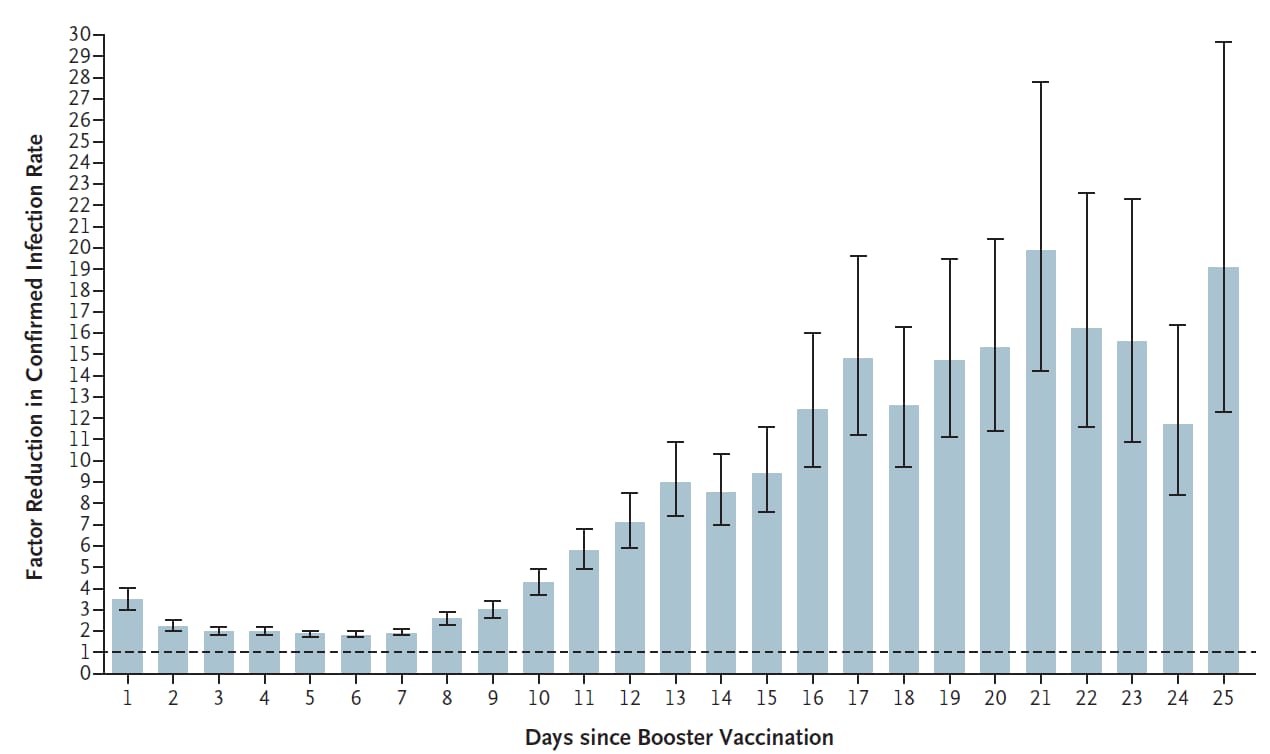

- Protection of BNT162b2 vaccine booster against COVID-19 in Israel external icon . Bar-On et al. NEJM (September 15, 2021). Among residents of Israel aged ≥60 years who had been vaccinated ≥5 months earlier (BNT162b2), a booster dose reduced the rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection by a factor of 11.3 (95% CI 10.4-12.3) and the rate of severe illness by a factor of 19.5 (95% CI 12.9-29.5), compared with persons who did not receive a booster dose. On each day between 12 and 25 days after receipt of the booster, the rate of confirmed infection was reduced by a factor of 7–20.

Note: Adapted from Bar-On et al. Factor reduction in the rate of confirmed infection among participants who received a 3 rd (booster) dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine as compared with those who did not receive a booster dose, by the number of days after the administration of the booster dose. The dashed horizontal line represents the level at which the booster dose provided no added protection. From the New England Journal of Medicine, Bar-On et al. , Protection of BNT162b2 vaccine booster against COVID-19 in Israel. September 15, 2021, online ahead of print. Copyright © 2021 Massachusetts Medical Society. Reprinted with permission from Massachusetts Medical Society.

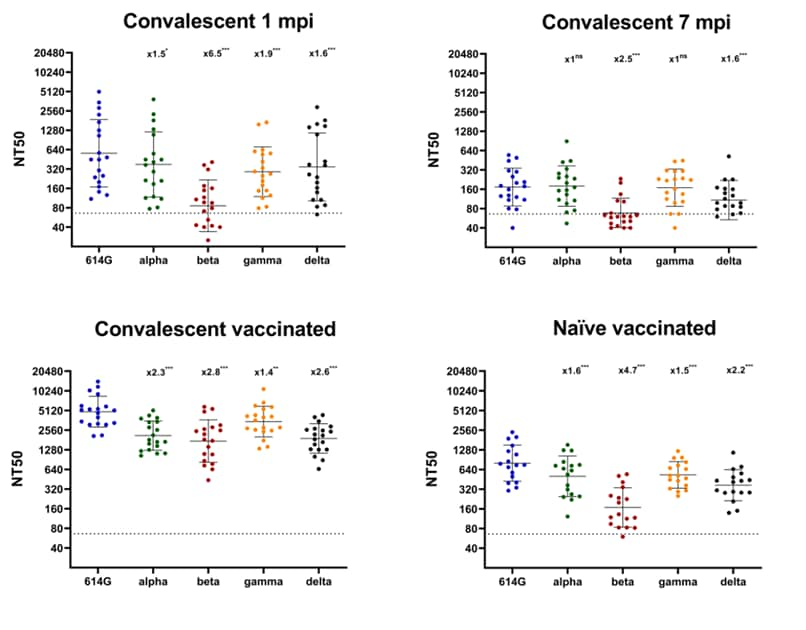

- Prime boost vaccination with BNT162b2 induces high neutralizing activity against SARS-CoV-2 variants in naïve and COVID-19 convalescent individuals external icon . Luczkowiak et al. Open Forum Infectious Diseases (September 24, 2021). In an analysis of COVID-19 naïve and infected healthcare workers during convalescence and post-BNT162b2 vaccination, sera from convalescent people showed decreased neutralizing activity against variants at 1 month post-infection, compared with the reference strain. Those fully vaccinated with BNT162b2 showed high levels of neutralizing antibodies to all variants, with convalescent people showing the highest neutralizing response.

Note: Adapted from Luczkowiak et al. Plasma neutralizing levels (NT50) against SARS-CoV-2: Reference S D614G and variants Alpha , Beta , Gamma , and Delta during COVID-19 convalescence and after BNT161b2 vaccination. Convalescent individuals (n = 19) tested 1-month post-infection (mpi), 7 mpi, and after BNT162b2; naïve group (n = 17) after BNT162b2. NT50 dilution values are presented as reciprocals. Solid lines: geometric mean; error bars: geometric SD. Dashed lines: cut-off titer (NT50 = 1/66). Fold-decrease in NT50 above scatter plot; *** statistically significant changes. Licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND.

- Outcome comparison of high-risk Native American patients who did or did not receive monoclonal antibody treatment for COVID-19 external icon . Close et al . JAMA Network Open (September 21, 2021). Among Native American people eligible for monoclonal antibody (mAb) treatment (n = 481) at a rural acute care facility in Arizona, 201 COVID-19 patients received mAb and experienced lower odds of death (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.29-0.66) than eligible patients who did not receive mAb.

- Understanding racial differences in attitudes about public health efforts during COVID-19 using an explanatory mixed methods design external icon . Nong et al. Social Science and Medicine (October 2021). In a study linking quantitative findings to explanatory qualitative interview questions (n = 1,000), Black or African American Michigan residents’ trust in public health agencies (adjusted beta coefficient [b] 0.07, p = 0.48) was not different from that of White residents (adjusted beta coefficient [b] 0.07, p = 0.48). An increased willingness to participate in public health interventions may be related to altruism and perceived risk of COVID-19 in the community.

- Identifying at-risk communities and key vulnerability indicators in the COVID-19 pandemic external icon . Thais et al . medRxiv (Preprint; September 22, 2021). In a validation study using open-source data to construct a model to describe communities at higher risk of COVID-19 and determine indicators for vulnerability during the COVID-19 pandemic, results suggest that prevalence of COVID-19 in a given area has more impact than prevalence of pre-existing co-morbidities. Childhood poverty, food insecurity, COVID-19 hospitalization rate, unemployment rate, and access to care were key indicators.

- The longitudinal kinetics of antibodies in COVID-19 recovered patients over 14 months external icon . Eyran et al. medRxiv (Preprint; September 21, 2021). Among 89 COVID-19 recovered patients and 17 infection-naïve BNT162b2 vaccinees followed over 14 months, antibody levels waned in 18% (IgG), 55% (IgM), and 62% (IgA) of persons to levels considered negative. Antibody decay rate in COVID-19-recovered patients was significantly slower compared with the decay in infection-naïve vaccinees.

- Impact of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection on post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 spike IgG antibodies in a longitudinal cohort of healthcare workers external icon . Zhong et al . medRxiv (Preprint; September 22, 2021). Published in JAMA as Durability of antibody levels after vaccination with mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in individuals with or without prior infection external icon (November 1, 2021). From June–September 2021, healthcare workers (HCWs) who received 2 doses of an mRNA vaccine (n = 1,960) had higher serum spike IgG antibody levels than HCWs with natural infection (n = 98). Serum IgG antibody values were 14%, 19%, and 56% higher for those infected with SARS-CoV-2 prior to vaccination (n = 73) than naïve HCWs (n = 1,887) at 1, 3, and 6 months after vaccination, respectively. HCWs infected >90 days before vaccination (n = 32) had 10% higher IgG levels than those infected < 90 days before vaccination (n = 41).

Note: Adapted from Zhong et al . A) Serum spike S1 IgG antibody levels ≥14 days following 2 doses of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine in HCWs with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection , without prior SARS-CoV-2 infection , and in those following SARS-CoV-2 positive PCR test and before vaccination . B) Serum spike S1 IgG antibody mRNA vaccination among HCWs with SARS-CoV-2 infection ≤90 days before vaccination and >90 days before vaccination . The lines represent median IgG as a function of days following mRNA vaccination or natural infection, based on natural cubic splines (2 degrees of freedom) for each group. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence intervals. Licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0.

- Comparison of children and young people admitted with SARS-CoV-2 across the UK in the first and second pandemic waves: prospective multicentre observational cohort study external icon . Swann et al . medRxiv (Preprint; September 17, 2021). Published in Pediatric Research as Comparison of UK paediatric SARS-CoV-2 admissions across the first and second pandemic waves external icon (April 22, 2022). Compared with children and adolescents hospitalized with COVID-19 during Wave 1 (January–July 2020), children and adolescents hospitalized during Wave 2 (August 2020–January 2021) were more likely to be older (median age [years] 6.5 vs. 4.0), and less likely to be at risk for clinical deterioration at presentation (38% vs. 47%), be prescribed antibiotics (51% vs. 67%), and need respiratory/cardiovascular support. The percentage admitted to critical care did not differ between waves (12% vs. 13%).

- Childhood asthma and COVID-19: a nested case-control study external icon . Gaietto et al . medRiv (Preprint; September 22, 2021). Published in Pediatric Allergy and Immunology as Asthma as a risk factor for hospitalization in children with COVID-19: A nested case-control study external icon (November 14, 2021). In a nested case-control study using clinical registry data, asthma severity in children was not associated with a higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Children with COVID-19 and asthma were more than 4 times as likely to be hospitalized compared with children with COVID-19 and without asthma; however, there was no difference in hospital stay length or need for respiratory support.

From the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (Month, day, year) .

- Disparities in COVID-19 Vaccination Status, Intent, and Perceived Access for Noninstitutionalized Adults, by Disability Status — National Immunization Survey Adult COVID Module, United States, May 30–June 26, 2021

- Association Between K–12 School Mask Policies and School-Associated COVID-19 Outbreaks — Maricopa and Pima Counties, Arizona, July–August 2021

- COVID-19–Related School Closures and Learning Modality Changes — United States, August 1–September 17, 2021

- Pediatric COVID-19 Cases in Counties With and Without School Mask Requirements — United States, July 1–September 4, 2021

- Safety Monitoring of an Additional Dose of COVID-19 Vaccine — United States, August 12–September 19, 2021

Disclaimer : The purpose of the CDC COVID-19 Science Update is to share public health articles with public health agencies and departments for informational and educational purposes. Materials listed in this Science Update are selected to provide awareness of relevant public health literature. A material’s inclusion and the material itself provided here in full or in part, does not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services or the CDC, nor does it necessarily imply endorsement of methods or findings. While much of the COVID-19 literature is open access or otherwise freely available, it is the responsibility of the third-party user to determine whether any intellectual property rights govern the use of materials in this Science Update prior to use or distribution. Findings are based on research available at the time of this publication and may be subject to change.

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

A monthly newsletter from the National Institutes of Health, part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

Search form

January 2021.

Feeling Stressed?

Ways to Improve Your Well-Being

Staying Safe From Sepsis

Preventing Infections and Improving Survival

Dr. Richard Davidson on Reducing Stress

Health Capsule

Postpartum Depression May Last for Years

Problems with your smell or taste.

Featured Website

Combat COVID

Contributors to this issue:

- Erin Bryant

- Sharon Reynolds

NIH Office of Communications and Public Liaison Building 31, Room 5B52 Bethesda, MD 20892-2094 [email protected] Tel: 301-451-8224

Editor: Harrison Wein, Ph.D. Managing Editor: Tianna Hicklin, Ph.D. Illustrator: Alan Defibaugh

Attention Editors: Reprint our articles and illustrations in your own publication. Our material is not copyrighted. Please acknowledge NIH News in Health as the source and send us a copy.

For more consumer health news and information, visit health.nih.gov .

For wellness toolkits, visit www.nih.gov/wellnesstoolkits .

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- News Feature

- Published: 07 December 2020

2021: research and medical trends in a post-pandemic world

- Mike May 1

Nature Medicine volume 26 , pages 1808–1809 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

9892 Accesses

3 Citations

25 Altmetric

Metrics details

Goodbye 2020, a year of arguably too many challenges for the world. As tempting as it is to leave this year behind, the biomedical community is forever changed by the pandemic, while business as usual needs to carry on. Looking forward to a new year, experts share six trends for the biomedical community in 2021.

Summing up 2020, Sharon Peacock, director of the COVID-19 Genomics UK Consortium, says “we’ve seen some excellent examples of people working together from academia, industry, and healthcare sectors...I’m hopeful that will stay with us going into 2021.” Nonetheless, we have lost ground and momentum in non-COVID research, she says. “This could have a profound effect on our ability to research other areas in the future.”

The coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 has already revealed weaknesses in medical research and clinical capabilities, as well as opportunities. Although it is too soon to know when countries around the world will control the COVID-19 pandemic, there is already much to be learned.

To explore trends for 2021, we talked to experts from around the world who specialize in medical research. Here is what we learned.

1. The new normal

Marion Koopman, head of the Erasmus MC Department of Viroscience, predicts that emerging-disease experts will overwhelmingly remain focused on SARS-CoV-2, at least for the coming year.

“I really hope we will not go back to life as we used to know it, because that would mean that the risk of emerging diseases and the need for an ambitious preparedness research agenda would go to the back burner,” Koopman says. “That cannot happen.”

Scientists must stay prepared, because the virus keeps changing. Already, Koopman says, “We have seen spillback [of SARS-CoV-2] into mink in our country, and ongoing circulation with accumulation of mutations in the spike and other parts of the genome.”

Juleen R. Zierath, an expert in the physiological mechanisms of metabolic diseases at the Karolinska Institute and the University of Copenhagen, points out that the pandemic “has raised attention to deleterious health consequences of metabolic diseases, including obesity and type 2 diabetes,” because people with these disorders have been “disproportionally affected by COVID-19.” She notes that the coupling of the immune system to metabolism at large probably deserves more attention.

2. Trial by fire for open repositories

The speed of SARS-CoV-2’s spread transformed how scientists disseminate information. “There is an increased use of open repositories such as bioRxiv and medRxiv, enabling faster dissemination of study and trial results,” says Alan Karthikesalingam, Research Lead at Google Health UK. “When paired with the complementary — though necessarily slower — approach of peer review that safeguards rigor and quality, this can result in faster innovation.”

“I suspect that the way in which we communicate ongoing scientific developments from our laboratories will change going forward,” Zierath says. That is already happening, with many meetings going to virtual formats.

Deborah Johnson, president and CEO of the Keystone Symposia on Molecular and Cellular Biology, notes that while virtual events cannot fully replace the networking opportunities that are created with in-person meetings, “virtual events have democratized access to biomedical research conferences, enabling greater participation from young investigators and those from low-and-middle-income countries.” Even when in-person conferences return, she says, “it will be important to continue to offer virtual components that engage these broader audiences.”

3. Leaps and bounds for immunology

Basic research on the immune system, catapulted to the frontlines of the COVID-19 response, has received a boost in attention this year, and more research in that field could pay off big going forward.

Immunobiologist Akiko Iwasaki at the Yale School of Medicine hopes that the pandemic will drive a transformation in immunology. “It has become quite clear over decades of research that mucosal immunity against respiratory, gastrointestinal, and sexually transmitted infections is much more effective in thwarting off invading pathogens than systemic immunity,” she says. “Yet, the vast majority of vaccine efforts are put into parenteral vaccines.”

“It is time for the immunology field to do a deep dive in understanding fundamental mechanisms of protection at the mucosal surfaces, as well as to developing strategies that allow the immune response to be targeted to the mucosal surfaces,” she explains.

“We are discovering that the roles of immune cells extend far beyond what was previously thought, to play underlying roles in health and disease across all human systems, from cancer to mental health,” says Johnson.

She sees this knowledge leading to more engineered immune cells to treat diseases. “Cancer immunotherapies will likely serve as the proving ground for immune-mediated therapies against many other diseases that we are only starting to see through the lens of the immune system.”

4. Rewind time for neurodegeneration

Oskar Hansson, research team manager of Lund University’s Clinical Memory Research, expects the trend of attempting to intervene against neurodegenerative disease before widespread neurodegeneration, and even before symptom onset, to continue next year.

This approach has already shown potential. “Several promising disease-modifying therapies against Alzheimer’s disease are now planned to be evaluated in this early pre-symptomatic disease phase,” he says, “and I think we will have similar developments in other areas like Parkinson’s disease and [amyotrophic lateral sclerosis].”

Delving deeper into such treatments depends on better understanding of how neurodegeneration develops. As Hansson notes, the continued development of cohort studies from around the world will help scientists “study how different factors — genetics, development, lifestyle, etcetera — affect the initiation and evolution of even the pre-symptomatic stages of the disease, which most probably will result in a much deeper understanding of the disease as well as discovery of new drug targets.”

5. Digital still front and center

“As [artificial intelligence] algorithms around the world begin to be released more commonly in regulated medical device software, I think there will be an increasing trend toward prospective research examining algorithmic robustness, safety, credibility and fairness in real-world medical settings,” says Karthikesalingam. “The opportunity for clinical and machine-learning research to improve patient outcomes in this setting is substantial.”

However, more trials are needed to prove which artificial intelligence works in medicine and which does not. Eric Topol, a cardiologist who combines genomic and digital medicine in his work at Scripps Research, says “there are not many big, annotated sets of data on, for example, scans, and you need big datasets to train new algorithms.” Otherwise, only unsupervised learning algorithms can be used, and “that’s trickier,” he says.

Despite today’s bottlenecks in advancing digital health, Topol remains very optimistic. “Over time, we’ll see tremendous progress across all modalities — imaging data, speech data, and text data — to gather important information through patient tests, research articles or reviewing patient chats,” he says.

He envisions that speech-recognition software could, for instance, capture physician–patient talks and turn them into notes. “Doctors will love this,” he says, “and patients will be able to look a doctor in the eye, which enhances the relationship.”

6. ‘Be better prepared’ — a new medical mantra

One trend that every expert interviewed has emphasized is the need for preparation. As Gabriel Leung, a specialist in public-health medicine at the University of Hong Kong, put it, “We need a readiness — not just in technology platforms but also business cases — to have a sustained pipeline of vaccines and therapies, so that we would not be scrambling for some of the solutions in the middle of a pandemic.”

Building social resilience ahead of a crisis is also important. “[SARS-CoV-2] and the resulting pandemic make up the single most important watershed in healthcare,” Leung explains. “The justice issue around infection risk, access to testing and treatment — thus outcomes — already make up the single gravest health inequity in the last century.”

One change that Peacock hopes for in the near future is the sequencing of pathogens on location, instead of more centrally. “For pathogen sequencing, you need to be able to apply it where the problem under investigation is happening,” she explains. “In the UK, COVID-19 has been the catalyst for us to develop a highly collaborative, distributed network of sequencing capabilities.”

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Freelance writer and editor, Bradenton, FL, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

May, M. 2021: research and medical trends in a post-pandemic world. Nat Med 26 , 1808–1809 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-01146-z

Download citation

Published : 07 December 2020

Issue Date : December 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-01146-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Impact of the covid-19 pandemic on career intention amongst undergraduate medical students: a single-centre cross-sectional study conducted in hubei province.

- Xue-lin Wang

- Ming-xiu Liu

BMC Medical Education (2022)

Translational precision medicine: an industry perspective

- Dominik Hartl

- Valeria de Luca

- Adrian Roth

Journal of Translational Medicine (2021)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

AAPC indicates average annual percent change.

a This AAPC value is statistically significant.

NSCLC indicates non–small cell lung cancer.

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Flores R , Patel P , Alpert N , Pyenson B , Taioli E. Association of Stage Shift and Population Mortality Among Patients With Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(12):e2137508. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.37508

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Association of Stage Shift and Population Mortality Among Patients With Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer

- 1 Department of Thoracic Surgery, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, Mount Sinai Health System, New York, New York

- 2 Institute for Translational Epidemiology and Tisch Cancer Institute, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York

- 3 NYU School of Global Public Health, New York, New York

- 4 Milliman Inc, New York, New York

Question To what extent does stage shift act as a confounding variable in the evaluation of population mortality of non–small cell lung cancer?

Findings In this cohort study of 312 382 patients, stage shift from later to earlier stage disease over the last decade was associated with improved mortality among people with lung cancer.

Meaning These findings suggest that studies investigating treatments for lung cancer must take into account stage shift and the confounding association with survival and mortality outcome.

Importance Early detection by computed tomography and a more attention-oriented approach to incidentally identified pulmonary nodules in the last decade has led to population stage shift for non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). This stage shift could substantially confound the evaluation of newer therapeutics and mortality outcomes.

Objective To investigate the association of stage shift with population mortality among patients with NSCLC.

Design, Setting, and Participants This retrospective cohort study was performed from October 2020 to June 2021 and used data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries to assess all patients from 2006 to 2016 with NSCLC.

Main Outcomes and Measures Incidence-based mortality was evaluated by year-of-death. To assess shifts in diagnostic characteristics, clinical stage and histology distributions were examined by year using χ 2 tests. Trends were assessed using the average annual percentage change (AAPC), calculated with JoinPoint software. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis assessed overall survival according to stage and compared those missing any stage with those with a reported stage.

Results The final sample contained 312 382 patients; 166 657 (53.4%) were male, 38 201 (12.2%) were Black, and 249 062 (79.7%) were White; the median (IQR) age was 68 (60-76) years; 163 086 (52.2%) had adenocarcinoma histology. Incidence-based mortality within 5 years of diagnosis decreased from 2006 to 2016 (AAPC, −3.7; 95% CI, −4.1 to −3.4). When assessing stage shift, there was significant association between year-of-diagnosis and clinical stage, with stage I/II diagnosis increasing from 26.5% to 31.2% (AAPC, 1.5; 95% CI, 0.5 to 2.5); and stage III/IV diagnosis decreasing significantly from 70.8% to 66.1% (AAPC, −0.6; 95% CI, −1.0 to −0.2). Missing staging information was not associated with year-of-diagnosis (AAPC, −1.6; 95% CI, −7.4 to 4.5). Year-of-diagnosis was significantly associated with tumor histology (χ 2 = 8990.0; P < .001). There was a significant increase in adenocarcinomas: 42.9% in 2006 to 59.0% in 2016 (AAPC, 3.4; 95% CI, 2.9 to 3.9). Median (IQR) survival for stage I/II was 57 months (18 months to not reached); stage III/IV was 7 (2-19) months; and missing stage was 10 (2-28) months. When compared with those with known stage, those without stage information had significantly worse survival than those with stage I/II, with survival between those with stage III and stage IV (log-rank χ 2 = 87 125.0; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance This cohort study found an association between decreased mortality and a corresponding diagnostic shift from later to earlier stage. These findings suggest that studies investigating the effect of treatment on lung cancer must take into account stage shift and the confounding association with survival and mortality outcome.

Lung cancer remains among the leading causes of cancer death in the United States. 1 , 2 Based on the Annual Report to the Nation, incidence rates for lung cancer have significantly declined from 2012 to 2016 (average annual percent change [AAPC] of −2.6% for male individuals and −1.1% for female individuals). 1 Moreover, mortality for lung cancer from 2013 to 2017 has decreased at a greater rate compared with the incidence and has experienced one of the largest declines in death rates compared with other common cancer deaths (AAPC of −4.8% among male individuals and −3.7% among female individuals). 1 The improved outcomes with lung cancer are quite multifactorial and can be attributed to advances in prevention, early detection, and treatment of lung cancer. 3 , 4