Narrative Writing: A Complete Guide for Teachers and Students

MASTERING THE CRAFT OF NARRATIVE WRITING

Narratives build on and encourage the development of the fundamentals of writing. They also require developing an additional skill set: the ability to tell a good yarn, and storytelling is as old as humanity.

We see and hear stories everywhere and daily, from having good gossip on the doorstep with a neighbor in the morning to the dramas that fill our screens in the evening.

Good narrative writing skills are hard-won by students even though it is an area of writing that most enjoy due to the creativity and freedom it offers.

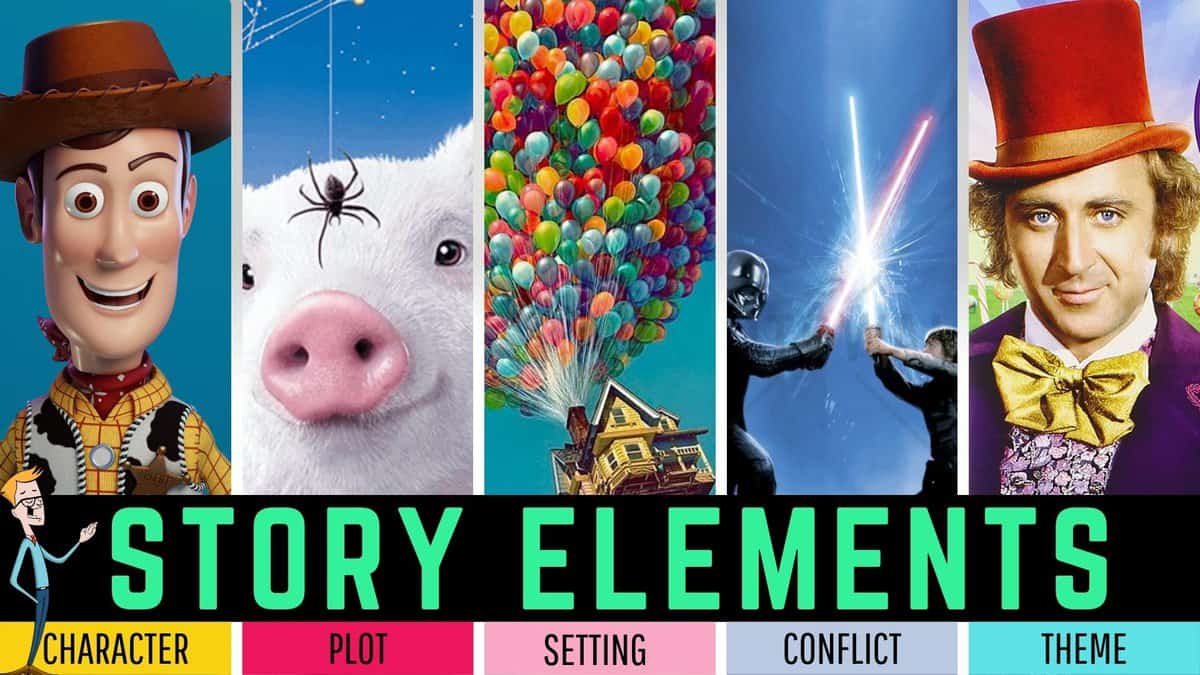

Here we will explore some of the main elements of a good story: plot, setting, characters, conflict, climax, and resolution . And we will look too at how best we can help our students understand these elements, both in isolation and how they mesh together as a whole.

WHAT IS A NARRATIVE?

A narrative is a story that shares a sequence of events , characters, and themes. It expresses experiences, ideas, and perspectives that should aspire to engage and inspire an audience.

A narrative can spark emotion, encourage reflection, and convey meaning when done well.

Narratives are a popular genre for students and teachers as they allow the writer to share their imagination, creativity, skill, and understanding of nearly all elements of writing. We occasionally refer to a narrative as ‘creative writing’ or story writing.

The purpose of a narrative is simple, to tell the audience a story. It can be written to motivate, educate, or entertain and can be fact or fiction.

A COMPLETE UNIT ON TEACHING NARRATIVE WRITING

Teach your students to become skilled story writers with this HUGE NARRATIVE & CREATIVE STORY WRITING UNIT . Offering a COMPLETE SOLUTION to teaching students how to craft CREATIVE CHARACTERS, SUPERB SETTINGS, and PERFECT PLOTS .

Over 192 PAGES of materials, including:

TYPES OF NARRATIVE WRITING

There are many narrative writing genres and sub-genres such as these.

We have a complete guide to writing a personal narrative that differs from the traditional story-based narrative covered in this guide. It includes personal narrative writing prompts, resources, and examples and can be found here.

As we can see, narratives are an open-ended form of writing that allows you to showcase creativity in many directions. However, all narratives share a common set of features and structure known as “Story Elements”, which are briefly covered in this guide.

Don’t overlook the importance of understanding story elements and the value this adds to you as a writer who can dissect and create grand narratives. We also have an in-depth guide to understanding story elements here .

CHARACTERISTICS OF NARRATIVE WRITING

Narrative structure.

ORIENTATION (BEGINNING) Set the scene by introducing your characters, setting and time of the story. Establish your who, when and where in this part of your narrative

COMPLICATION AND EVENTS (MIDDLE) In this section activities and events involving your main characters are expanded upon. These events are written in a cohesive and fluent sequence.

RESOLUTION (ENDING) Your complication is resolved in this section. It does not have to be a happy outcome, however.

EXTRAS: Whilst orientation, complication and resolution are the agreed norms for a narrative, there are numerous examples of popular texts that did not explicitly follow this path exactly.

NARRATIVE FEATURES

LANGUAGE: Use descriptive and figurative language to paint images inside your audience’s minds as they read.

PERSPECTIVE Narratives can be written from any perspective but are most commonly written in first or third person.

DIALOGUE Narratives frequently switch from narrator to first-person dialogue. Always use speech marks when writing dialogue.

TENSE If you change tense, make it perfectly clear to your audience what is happening. Flashbacks might work well in your mind but make sure they translate to your audience.

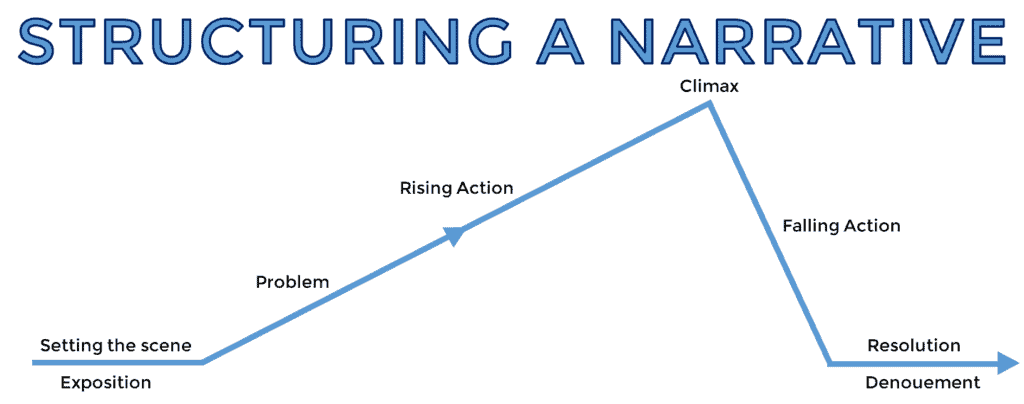

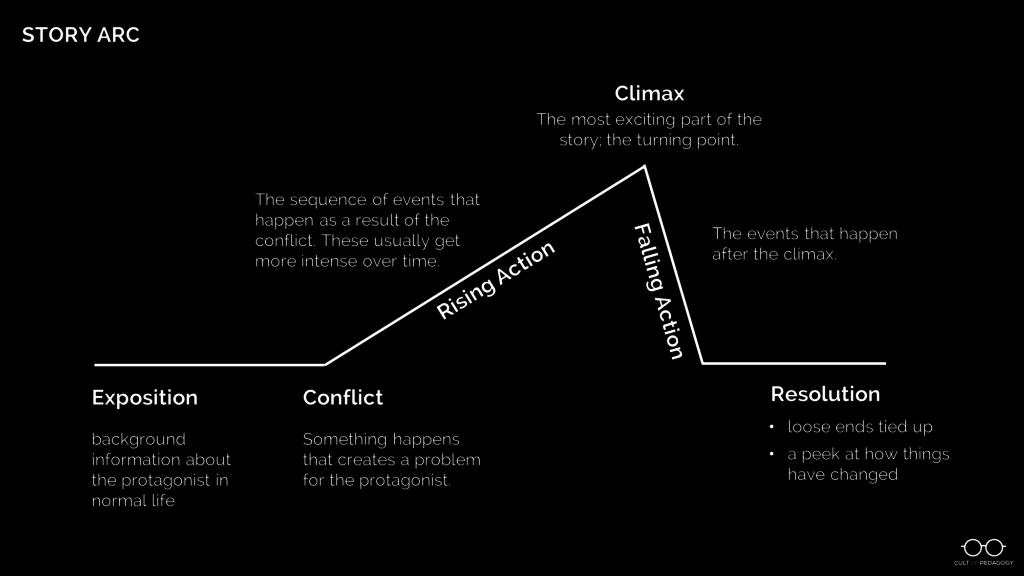

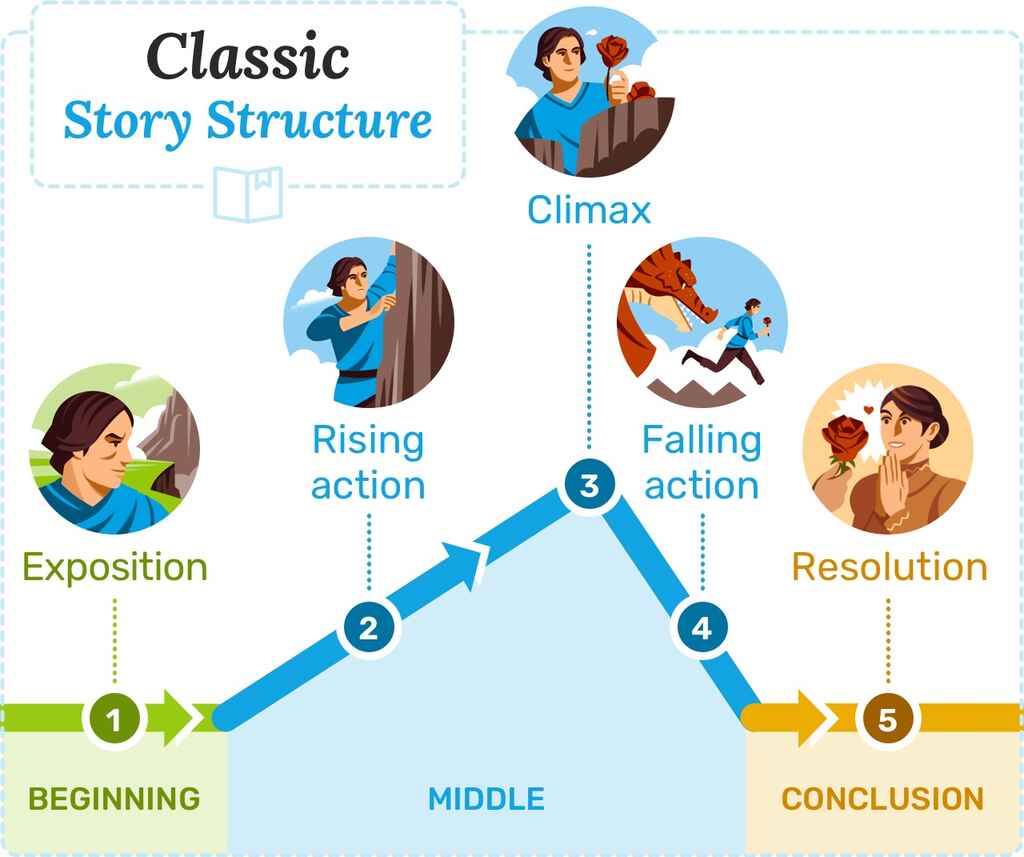

THE PLOT MAP

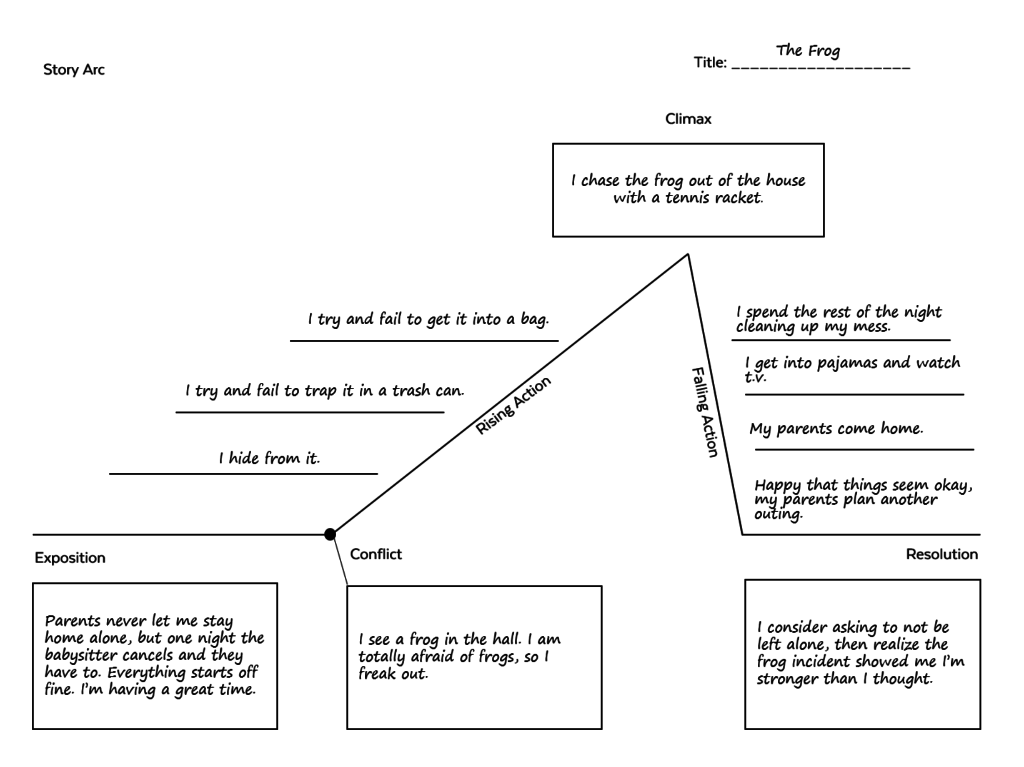

This graphic is known as a plot map, and nearly all narratives fit this structure in one way or another, whether romance novels, science fiction or otherwise.

It is a simple tool that helps you understand and organise a story’s events. Think of it as a roadmap that outlines the journey of your characters and the events that unfold. It outlines the different stops along the way, such as the introduction, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution, that help you to see how the story builds and develops.

Using a plot map, you can see how each event fits into the larger picture and how the different parts of the story work together to create meaning. It’s a great way to visualize and analyze a story.

Be sure to refer to a plot map when planning a story, as it has all the essential elements of a great story.

THE 5 KEY STORY ELEMENTS OF A GREAT NARRATIVE (6-MINUTE TUTORIAL VIDEO)

This video we created provides an excellent overview of these elements and demonstrates them in action in stories we all know and love.

HOW TO WRITE A NARRATIVE

Now that we understand the story elements and how they come together to form stories, it’s time to start planning and writing your narrative.

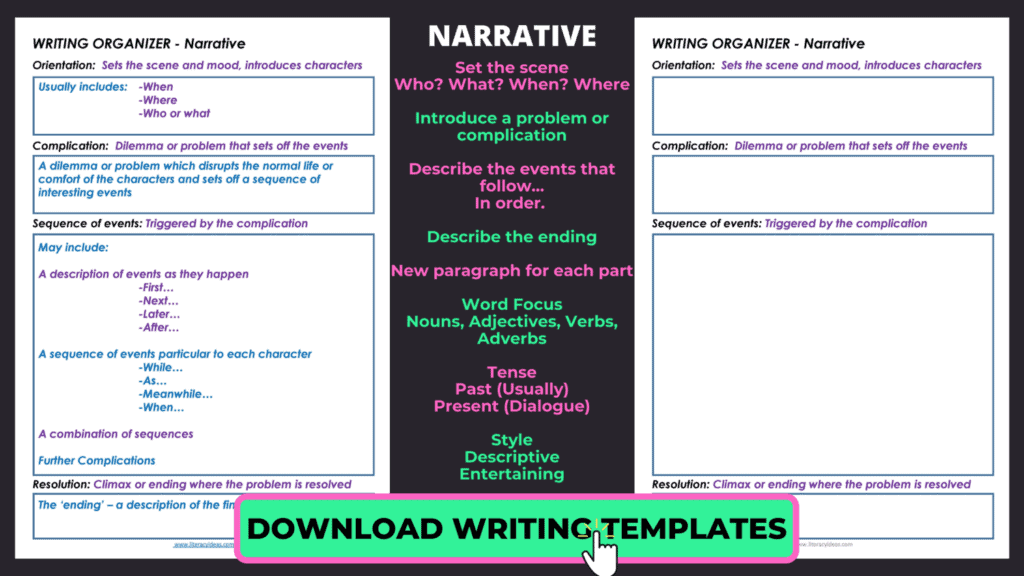

In many cases, the template and guide below will provide enough details on how to craft a great story. However, if you still need assistance with the fundamentals of writing, such as sentence structure, paragraphs and using correct grammar, we have some excellent guides on those here.

USE YOUR WRITING TIME EFFECTIVELY: Maximize your narrative writing sessions by spending approximately 20 per cent of your time planning and preparing. This ensures greater productivity during your writing time and keeps you focused and on task.

Use tools such as graphic organizers to logically sequence your narrative if you are not a confident story writer. If you are working with reluctant writers, try using narrative writing prompts to get their creative juices flowing.

Spend most of your writing hour on the task at hand, don’t get too side-tracked editing during this time and leave some time for editing. When editing a narrative, examine it for these three elements.

- Spelling and grammar ( Is it readable?)

- Story structure and continuity ( Does it make sense, and does it flow? )

- Character and plot analysis. (Are your characters engaging? Does your problem/resolution work? )

1. SETTING THE SCENE: THE WHERE AND THE WHEN

The story’s setting often answers two of the central questions in the story, namely, the where and the when. The answers to these two crucial questions will often be informed by the type of story the student is writing.

The story’s setting can be chosen to quickly orient the reader to the type of story they are reading. For example, a fictional narrative writing piece such as a horror story will often begin with a description of a haunted house on a hill or an abandoned asylum in the middle of the woods. If we start our story on a rocket ship hurtling through the cosmos on its space voyage to the Alpha Centauri star system, we can be reasonably sure that the story we are embarking on is a work of science fiction.

Such conventions are well-worn clichés true, but they can be helpful starting points for our novice novelists to make a start.

Having students choose an appropriate setting for the type of story they wish to write is an excellent exercise for our younger students. It leads naturally onto the next stage of story writing, which is creating suitable characters to populate this fictional world they have created. However, older or more advanced students may wish to play with the expectations of appropriate settings for their story. They may wish to do this for comic effect or in the interest of creating a more original story. For example, opening a story with a children’s birthday party does not usually set up the expectation of a horror story. Indeed, it may even lure the reader into a happy reverie as they remember their own happy birthday parties. This leaves them more vulnerable to the surprise element of the shocking action that lies ahead.

Once the students have chosen a setting for their story, they need to start writing. Little can be more terrifying to English students than the blank page and its bare whiteness stretching before them on the table like a merciless desert they must cross. Give them the kick-start they need by offering support through word banks or writing prompts. If the class is all writing a story based on the same theme, you may wish to compile a common word bank on the whiteboard as a prewriting activity. Write the central theme or genre in the middle of the board. Have students suggest words or phrases related to the theme and list them on the board.

You may wish to provide students with a copy of various writing prompts to get them started. While this may mean that many students’ stories will have the same beginning, they will most likely arrive at dramatically different endings via dramatically different routes.

A bargain is at the centre of the relationship between the writer and the reader. That bargain is that the reader promises to suspend their disbelief as long as the writer creates a consistent and convincing fictional reality. Creating a believable world for the fictional characters to inhabit requires the student to draw on convincing details. The best way of doing this is through writing that appeals to the senses. Have your student reflect deeply on the world that they are creating. What does it look like? Sound like? What does the food taste like there? How does it feel like to walk those imaginary streets, and what aromas beguile the nose as the main character winds their way through that conjured market?

Also, Consider the when; or the time period. Is it a future world where things are cleaner and more antiseptic? Or is it an overcrowded 16th-century London with human waste stinking up the streets? If students can create a multi-sensory installation in the reader’s mind, then they have done this part of their job well.

Popular Settings from Children’s Literature and Storytelling

- Fairytale Kingdom

- Magical Forest

- Village/town

- Underwater world

- Space/Alien planet

2. CASTING THE CHARACTERS: THE WHO

Now that your student has created a believable world, it is time to populate it with believable characters.

In short stories, these worlds mustn’t be overpopulated beyond what the student’s skill level can manage. Short stories usually only require one main character and a few secondary ones. Think of the short story more as a small-scale dramatic production in an intimate local theater than a Hollywood blockbuster on a grand scale. Too many characters will only confuse and become unwieldy with a canvas this size. Keep it simple!

Creating believable characters is often one of the most challenging aspects of narrative writing for students. Fortunately, we can do a few things to help students here. Sometimes it is helpful for students to model their characters on actual people they know. This can make things a little less daunting and taxing on the imagination. However, whether or not this is the case, writing brief background bios or descriptions of characters’ physical personality characteristics can be a beneficial prewriting activity. Students should give some in-depth consideration to the details of who their character is: How do they walk? What do they look like? Do they have any distinguishing features? A crooked nose? A limp? Bad breath? Small details such as these bring life and, therefore, believability to characters. Students can even cut pictures from magazines to put a face to their character and allow their imaginations to fill in the rest of the details.

Younger students will often dictate to the reader the nature of their characters. To improve their writing craft, students must know when to switch from story-telling mode to story-showing mode. This is particularly true when it comes to character. Encourage students to reveal their character’s personality through what they do rather than merely by lecturing the reader on the faults and virtues of the character’s personality. It might be a small relayed detail in the way they walk that reveals a core characteristic. For example, a character who walks with their head hanging low and shoulders hunched while avoiding eye contact has been revealed to be timid without the word once being mentioned. This is a much more artistic and well-crafted way of doing things and is less irritating for the reader. A character who sits down at the family dinner table immediately snatches up his fork and starts stuffing roast potatoes into his mouth before anyone else has even managed to sit down has revealed a tendency towards greed or gluttony.

Understanding Character Traits

Again, there is room here for some fun and profitable prewriting activities. Give students a list of character traits and have them describe a character doing something that reveals that trait without ever employing the word itself.

It is also essential to avoid adjective stuffing here. When looking at students’ early drafts, adjective stuffing is often apparent. To train the student out of this habit, choose an adjective and have the student rewrite the sentence to express this adjective through action rather than telling.

When writing a story, it is vital to consider the character’s traits and how they will impact the story’s events. For example, a character with a strong trait of determination may be more likely to overcome obstacles and persevere. In contrast, a character with a tendency towards laziness may struggle to achieve their goals. In short, character traits add realism, depth, and meaning to a story, making it more engaging and memorable for the reader.

Popular Character Traits in Children’s Stories

- Determination

- Imagination

- Perseverance

- Responsibility

We have an in-depth guide to creating great characters here , but most students should be fine to move on to planning their conflict and resolution.

3. NO PROBLEM? NO STORY! HOW CONFLICT DRIVES A NARRATIVE

This is often the area apprentice writers have the most difficulty with. Students must understand that without a problem or conflict, there is no story. The problem is the driving force of the action. Usually, in a short story, the problem will center around what the primary character wants to happen or, indeed, wants not to happen. It is the hurdle that must be overcome. It is in the struggle to overcome this hurdle that events happen.

Often when a student understands the need for a problem in a story, their completed work will still not be successful. This is because, often in life, problems remain unsolved. Hurdles are not always successfully overcome. Students pick up on this.

We often discuss problems with friends that will never be satisfactorily resolved one way or the other, and we accept this as a part of life. This is not usually the case with writing a story. Whether a character successfully overcomes his or her problem or is decidedly crushed in the process of trying is not as important as the fact that it will finally be resolved one way or the other.

A good practical exercise for students to get to grips with this is to provide copies of stories and have them identify the central problem or conflict in each through discussion. Familiar fables or fairy tales such as Three Little Pigs, The Boy Who Cried Wolf, Cinderella, etc., are great for this.

While it is true that stories often have more than one problem or that the hero or heroine is unsuccessful in their first attempt to solve a central problem, for beginning students and intermediate students, it is best to focus on a single problem, especially given the scope of story writing at this level. Over time students will develop their abilities to handle more complex plots and write accordingly.

Popular Conflicts found in Children’s Storytelling.

- Good vs evil

- Individual vs society

- Nature vs nurture

- Self vs others

- Man vs self

- Man vs nature

- Man vs technology

- Individual vs fate

- Self vs destiny

Conflict is the heart and soul of any good story. It’s what makes a story compelling and drives the plot forward. Without conflict, there is no story. Every great story has a struggle or a problem that needs to be solved, and that’s where conflict comes in. Conflict is what makes a story exciting and keeps the reader engaged. It creates tension and suspense and makes the reader care about the outcome.

Like in real life, conflict in a story is an opportunity for a character’s growth and transformation. It’s a chance for them to learn and evolve, making a story great. So next time stories are written in the classroom, remember that conflict is an essential ingredient, and without it, your story will lack the energy, excitement, and meaning that makes it truly memorable.

4. THE NARRATIVE CLIMAX: HOW THINGS COME TO A HEAD!

The climax of the story is the dramatic high point of the action. It is also when the struggles kicked off by the problem come to a head. The climax will ultimately decide whether the story will have a happy or tragic ending. In the climax, two opposing forces duke things out until the bitter (or sweet!) end. One force ultimately emerges triumphant. As the action builds throughout the story, suspense increases as the reader wonders which of these forces will win out. The climax is the release of this suspense.

Much of the success of the climax depends on how well the other elements of the story have been achieved. If the student has created a well-drawn and believable character that the reader can identify with and feel for, then the climax will be more powerful.

The nature of the problem is also essential as it determines what’s at stake in the climax. The problem must matter dearly to the main character if it matters at all to the reader.

Have students engage in discussions about their favorite movies and books. Have them think about the storyline and decide the most exciting parts. What was at stake at these moments? What happened in your body as you read or watched? Did you breathe faster? Or grip the cushion hard? Did your heart rate increase, or did you start to sweat? This is what a good climax does and what our students should strive to do in their stories.

The climax puts it all on the line and rolls the dice. Let the chips fall where the writer may…

Popular Climax themes in Children’s Stories

- A battle between good and evil

- The character’s bravery saves the day

- Character faces their fears and overcomes them

- The character solves a mystery or puzzle.

- The character stands up for what is right.

- Character reaches their goal or dream.

- The character learns a valuable lesson.

- The character makes a selfless sacrifice.

- The character makes a difficult decision.

- The character reunites with loved ones or finds true friendship.

5. RESOLUTION: TYING UP LOOSE ENDS

After the climactic action, a few questions will often remain unresolved for the reader, even if all the conflict has been resolved. The resolution is where those lingering questions will be answered. The resolution in a short story may only be a brief paragraph or two. But, in most cases, it will still be necessary to include an ending immediately after the climax can feel too abrupt and leave the reader feeling unfulfilled.

An easy way to explain resolution to students struggling to grasp the concept is to point to the traditional resolution of fairy tales, the “And they all lived happily ever after” ending. This weather forecast for the future allows the reader to take their leave. Have the student consider the emotions they want to leave the reader with when crafting their resolution.

While the action is usually complete by the end of the climax, it is in the resolution that if there is a twist to be found, it will appear – think of movies such as The Usual Suspects. Pulling this off convincingly usually requires considerable skill from a student writer. Still, it may well form a challenging extension exercise for those more gifted storytellers among your students.

Popular Resolutions in Children’s Stories

- Our hero achieves their goal

- The character learns a valuable lesson

- A character finds happiness or inner peace.

- The character reunites with loved ones.

- Character restores balance to the world.

- The character discovers their true identity.

- Character changes for the better.

- The character gains wisdom or understanding.

- Character makes amends with others.

- The character learns to appreciate what they have.

Once students have completed their story, they can edit for grammar, vocabulary choice, spelling, etc., but not before!

As mentioned, there is a craft to storytelling, as well as an art. When accurate grammar, perfect spelling, and immaculate sentence structures are pushed at the outset, they can cause storytelling paralysis. For this reason, it is essential that when we encourage the students to write a story, we give them license to make mechanical mistakes in their use of language that they can work on and fix later.

Good narrative writing is a very complex skill to develop and will take the student years to become competent. It challenges not only the student’s technical abilities with language but also her creative faculties. Writing frames, word banks, mind maps, and visual prompts can all give valuable support as students develop the wide-ranging and challenging skills required to produce a successful narrative writing piece. But, at the end of it all, as with any craft, practice and more practice is at the heart of the matter.

TIPS FOR WRITING A GREAT NARRATIVE

- Start your story with a clear purpose: If you can determine the theme or message you want to convey in your narrative before starting it will make the writing process so much simpler.

- Choose a compelling storyline and sell it through great characters, setting and plot: Consider a unique or interesting story that captures the reader’s attention, then build the world and characters around it.

- Develop vivid characters that are not all the same: Make your characters relatable and memorable by giving them distinct personalities and traits you can draw upon in the plot.

- Use descriptive language to hook your audience into your story: Use sensory language to paint vivid images and sequences in the reader’s mind.

- Show, don’t tell your audience: Use actions, thoughts, and dialogue to reveal character motivations and emotions through storytelling.

- Create a vivid setting that is clear to your audience before getting too far into the plot: Describe the time and place of your story to immerse the reader fully.

- Build tension: Refer to the story map earlier in this article and use conflict, obstacles, and suspense to keep the audience engaged and invested in your narrative.

- Use figurative language such as metaphors, similes, and other literary devices to add depth and meaning to your narrative.

- Edit, revise, and refine: Take the time to refine and polish your writing for clarity and impact.

- Stay true to your voice: Maintain your unique perspective and style in your writing to make it your own.

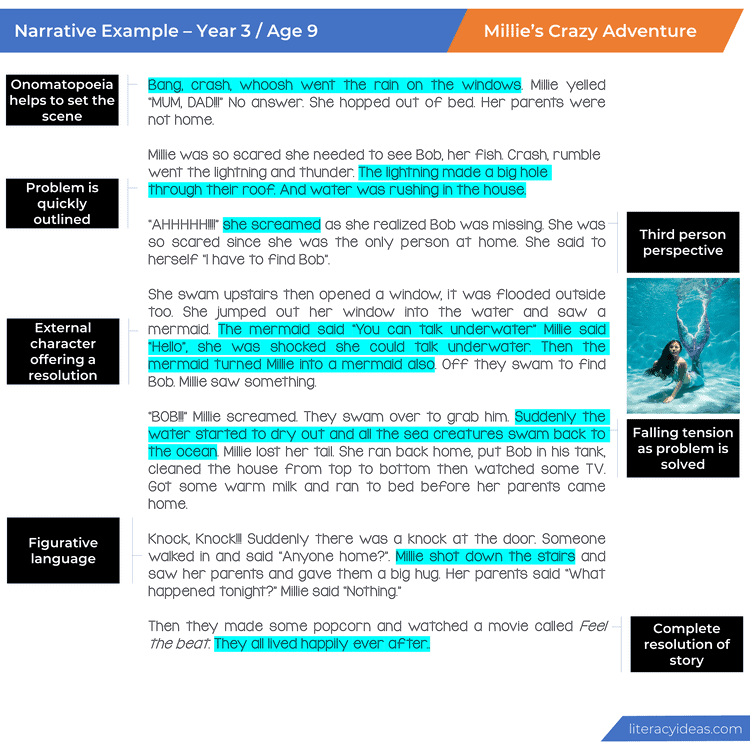

NARRATIVE WRITING EXAMPLES (Student Writing Samples)

Below are a collection of student writing samples of narratives. Click on the image to enlarge and explore them in greater detail. Please take a moment to read these creative stories in detail and the teacher and student guides which highlight some of the critical elements of narratives to consider before writing.

Please understand these student writing samples are not intended to be perfect examples for each age or grade level but a piece of writing for students and teachers to explore together to critically analyze to improve student writing skills and deepen their understanding of story writing.

We recommend reading the example either a year above or below, as well as the grade you are currently working with, to gain a broader appreciation of this text type.

NARRATIVE WRITING PROMPTS (Journal Prompts)

When students have a great journal prompt, it can help them focus on the task at hand, so be sure to view our vast collection of visual writing prompts for various text types here or use some of these.

- On a recent European trip, you find your travel group booked into the stunning and mysterious Castle Frankenfurter for a single night… As night falls, the massive castle of over one hundred rooms seems to creak and groan as a series of unexplained events begin to make you wonder who or what else is spending the evening with you. Write a narrative that tells the story of your evening.

- You are a famous adventurer who has discovered new lands; keep a travel log over a period of time in which you encounter new and exciting adventures and challenges to overcome. Ensure your travel journal tells a story and has a definite introduction, conflict and resolution.

- You create an incredible piece of technology that has the capacity to change the world. As you sit back and marvel at your innovation and the endless possibilities ahead of you, it becomes apparent there are a few problems you didn’t really consider. You might not even be able to control them. Write a narrative in which you ride the highs and lows of your world-changing creation with a clear introduction, conflict and resolution.

- As the final door shuts on the Megamall, you realise you have done it… You and your best friend have managed to sneak into the largest shopping centre in town and have the entire place to yourselves until 7 am tomorrow. There is literally everything and anything a child would dream of entertaining themselves for the next 12 hours. What amazing adventures await you? What might go wrong? And how will you get out of there scot-free?

- A stranger walks into town… Whilst appearing similar to almost all those around you, you get a sense that this person is from another time, space or dimension… Are they friends or foes? What makes you sense something very strange is going on? Suddenly they stand up and walk toward you with purpose extending their hand… It’s almost as if they were reading your mind.

NARRATIVE WRITING VIDEO TUTORIAL

Teaching Resources

Use our resources and tools to improve your student’s writing skills through proven teaching strategies.

When teaching narrative writing, it is essential that you have a range of tools, strategies and resources at your disposal to ensure you get the most out of your writing time. You can find some examples below, which are free and paid premium resources you can use instantly without any preparation.

FREE Narrative Graphic Organizer

THE STORY TELLERS BUNDLE OF TEACHING RESOURCES

A MASSIVE COLLECTION of resources for narratives and story writing in the classroom covering all elements of crafting amazing stories. MONTHS WORTH OF WRITING LESSONS AND RESOURCES, including:

NARRATIVE WRITING CHECKLIST BUNDLE

OTHER GREAT ARTICLES ABOUT NARRATIVE WRITING

Narrative Writing for Kids: Essential Skills and Strategies

7 Great Narrative Lesson Plans Students and Teachers Love

Top 7 Narrative Writing Exercises for Students

How to Write a Scary Story

A Step-by-Step Plan for Teaching Narrative Writing

July 29, 2018

Can't find what you are looking for? Contact Us

Listen to this post as a podcast:

Sponsored by Peergrade and Microsoft Class Notebook

This post contains Amazon Affiliate links. When you make a purchase through these links, Cult of Pedagogy gets a small percentage of the sale at no extra cost to you.

“Those who tell the stories rule the world.” This proverb, attributed to the Hopi Indians, is one I wish I’d known a long time ago, because I would have used it when teaching my students the craft of storytelling. With a well-told story we can help a person see things in an entirely new way. We can forge new relationships and strengthen the ones we already have. We can change a law, inspire a movement, make people care fiercely about things they’d never given a passing thought.

But when we study storytelling with our students, we forget all that. Or at least I did. When my students asked why we read novels and stories, and why we wrote personal narratives and fiction, my defense was pretty lame: I probably said something about the importance of having a shared body of knowledge, or about the enjoyment of losing yourself in a book, or about the benefits of having writing skills in general.

I forgot to talk about the power of story. I didn’t bother to tell them that the ability to tell a captivating story is one of the things that makes human beings extraordinary. It’s how we connect to each other. It’s something to celebrate, to study, to perfect. If we’re going to talk about how to teach students to write stories, we should start by thinking about why we tell stories at all . If we can pass that on to our students, then we will be going beyond a school assignment; we will be doing something transcendent.

Now. How do we get them to write those stories? I’m going to share the process I used for teaching narrative writing. I used this process with middle school students, but it would work with most age groups.

A Note About Form: Personal Narrative or Short Story?

When teaching narrative writing, many teachers separate personal narratives from short stories. In my own classroom, I tended to avoid having my students write short stories because personal narratives were more accessible. I could usually get students to write about something that really happened, while it was more challenging to get them to make something up from scratch.

In the “real” world of writers, though, the main thing that separates memoir from fiction is labeling: A writer might base a novel heavily on personal experiences, but write it all in third person and change the names of characters to protect the identities of people in real life. Another writer might create a short story in first person that reads like a personal narrative, but is entirely fictional. Just last weekend my husband and I watched the movie Lion and were glued to the screen the whole time, knowing it was based on a true story. James Frey’s book A Million Little Pieces sold millions of copies as a memoir but was later found to contain more than a little bit of fiction. Then there are unique books like Curtis Sittenfeld’s brilliant novel American Wife , based heavily on the early life of Laura Bush but written in first person, with fictional names and settings, and labeled as a work of fiction. The line between fact and fiction has always been really, really blurry, but the common thread running through all of it is good storytelling.

With that in mind, the process for teaching narrative writing can be exactly the same for writing personal narratives or short stories; it’s the same skill set. So if you think your students can handle the freedom, you might decide to let them choose personal narrative or fiction for a narrative writing assignment, or simply tell them that whether the story is true doesn’t matter, as long as they are telling a good story and they are not trying to pass off a fictional story as fact.

Here are some examples of what that kind of flexibility could allow:

- A student might tell a true story from their own experience, but write it as if it were a fiction piece, with fictional characters, in third person.

- A student might create a completely fictional story, but tell it in first person, which would give it the same feel as a personal narrative.

- A student might tell a true story that happened to someone else, but write it in first person, as if they were that person. For example, I could write about my grandmother’s experience of getting lost as a child, but I might write it in her voice.

If we aren’t too restrictive about what we call these pieces, and we talk about different possibilities with our students, we can end up with lots of interesting outcomes. Meanwhile, we’re still teaching students the craft of narrative writing.

A Note About Process: Write With Your Students

One of the most powerful techniques I used as a writing teacher was to do my students’ writing assignments with them. I would start my own draft at the same time as they did, composing “live” on the classroom projector, and doing a lot of thinking out loud so they could see all the decisions a writer has to make.

The most helpful parts for them to observe were the early drafting stage, where I just scratched out whatever came to me in messy, run-on sentences, and the revision stage, where I crossed things out, rearranged, and made tons of notes on my writing. I have seen over and over again how witnessing that process can really help to unlock a student’s understanding of how writing actually gets made.

A Narrative Writing Unit Plan

Before I get into these steps, I should note that there is no one right way to teach narrative writing, and plenty of accomplished teachers are doing it differently and getting great results. This just happens to be a process that has worked for me.

Step 1: Show Students That Stories Are Everywhere

Getting our students to tell stories should be easy. They hear and tell stories all the time. But when they actually have to put words on paper, they forget their storytelling abilities: They can’t think of a topic. They omit relevant details, but go on and on about irrelevant ones. Their dialogue is bland. They can’t figure out how to start. They can’t figure out how to end.

So the first step in getting good narrative writing from students is to help them see that they are already telling stories every day . They gather at lockers to talk about that thing that happened over the weekend. They sit at lunch and describe an argument they had with a sibling. Without even thinking about it, they begin sentences with “This one time…” and launch into stories about their earlier childhood experiences. Students are natural storytellers; learning how to do it well on paper is simply a matter of studying good models, then imitating what those writers do.

So start off the unit by getting students to tell their stories. In journal quick-writes, think-pair-shares, or by playing a game like Concentric Circles , prompt them to tell some of their own brief stories: A time they were embarrassed. A time they lost something. A time they didn’t get to do something they really wanted to do. By telling their own short anecdotes, they will grow more comfortable and confident in their storytelling abilities. They will also be generating a list of topic ideas. And by listening to the stories of their classmates, they will be adding onto that list and remembering more of their own stories.

And remember to tell some of your own. Besides being a good way to bond with students, sharing your stories will help them see more possibilities for the ones they can tell.

Step 2: Study the Structure of a Story

Now that students have a good library of their own personal stories pulled into short-term memory, shift your focus to a more formal study of what a story looks like.

Use a diagram to show students a typical story arc like the one below. Then, using a simple story—like this Coca Cola commercial —fill out the story arc with the components from that story. Once students have seen this story mapped out, have them try it with another one, like a story you’ve read in class, a whole novel, or another short video.

Step 3: Introduce the Assignment

Up to this point, students have been immersed in storytelling. Now give them specific instructions for what they are going to do. Share your assignment rubric so they understand the criteria that will be used to evaluate them; it should be ready and transparent right from the beginning of the unit. As always, I recommend using a single point rubric for this.

Step 4: Read Models

Once the parameters of the assignment have been explained, have students read at least one model story, a mentor text that exemplifies the qualities you’re looking for. This should be a story on a topic your students can kind of relate to, something they could see themselves writing. For my narrative writing unit (see the end of this post), I wrote a story called “Frog” about a 13-year-old girl who finally gets to stay home alone, then finds a frog in her house and gets completely freaked out, which basically ruins the fun she was planning for the night.

They will be reading this model as writers, looking at how the author shaped the text for a purpose, so that they can use those same strategies in their own writing. Have them look at your rubric and find places in the model that illustrate the qualities listed in the rubric. Then have them complete a story arc for the model so they can see the underlying structure.

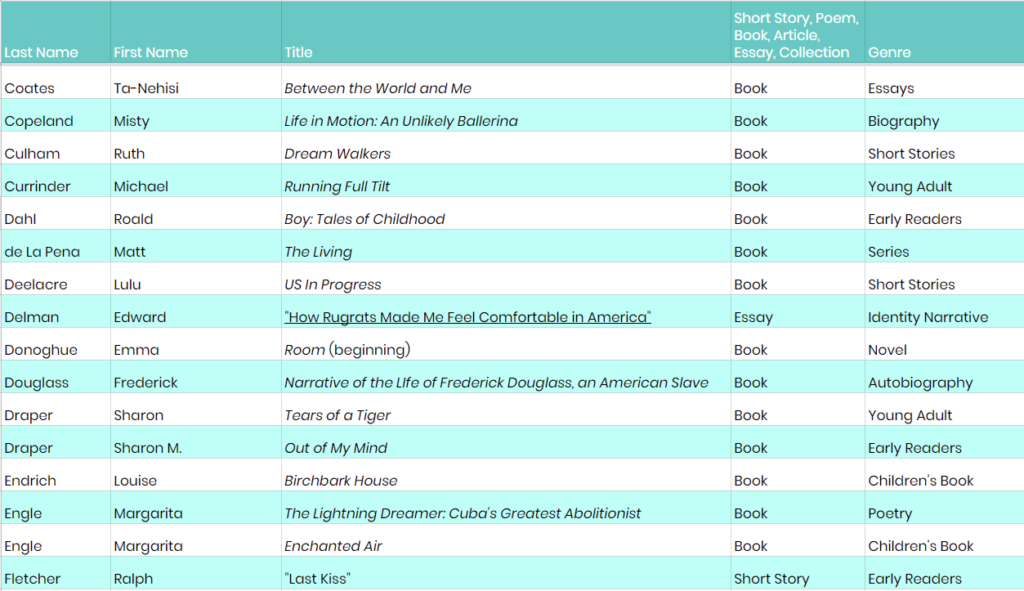

Ideally, your students will have already read lots of different stories to look to as models. If that isn’t the case, this list of narrative texts recommended by Cult of Pedagogy followers on Twitter would be a good place to browse for titles that might be right for your students. Keep in mind that we have not read most of these stories, so be sure to read them first before adopting them for classroom use.

Click the image above to view the full list of narrative texts recommended by Cult of Pedagogy followers on Twitter. If you have a suggestion for the list, please email us through our contact page.

Step 5: Story Mapping

At this point, students will need to decide what they are going to write about. If they are stuck for a topic, have them just pick something they can write about, even if it’s not the most captivating story in the world. A skilled writer could tell a great story about deciding what to have for lunch. If they are using the skills of narrative writing, the topic isn’t as important as the execution.

Have students complete a basic story arc for their chosen topic using a diagram like the one below. This will help them make sure that they actually have a story to tell, with an identifiable problem, a sequence of events that build to a climax, and some kind of resolution, where something is different by the end. Again, if you are writing with your students, this would be an important step to model for them with your own story-in-progress.

Step 6: Quick Drafts

Now, have students get their chosen story down on paper as quickly as possible: This could be basically a long paragraph that would read almost like a summary, but it would contain all the major parts of the story. Model this step with your own story, so they can see that you are not shooting for perfection in any way. What you want is a working draft, a starting point, something to build on for later, rather than a blank page (or screen) to stare at.

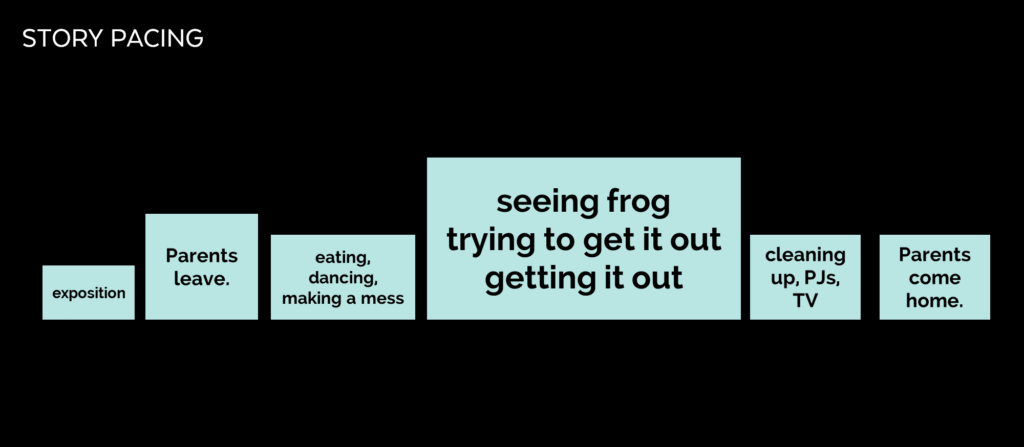

Step 7: Plan the Pacing

Now that the story has been born in raw form, students can begin to shape it. This would be a good time for a lesson on pacing, where students look at how writers expand some moments to create drama and shrink other moments so that the story doesn’t drag. Creating a diagram like the one below forces a writer to decide how much space to devote to all of the events in the story.

Before students write a full draft, have them plan out the events in their story with a pacing diagram, a visual representation of how much “space” each part of the story is going to take up.

Step 8: Long Drafts

With a good plan in hand, students can now slow down and write a proper draft, expanding the sections of their story that they plan to really draw out and adding in more of the details that they left out in the quick draft.

Step 9: Workshop

Once students have a decent rough draft—something that has a basic beginning, middle, and end, with some discernible rising action, a climax of some kind, and a resolution, you’re ready to shift into full-on workshop mode. I would do this for at least a week: Start class with a short mini-lesson on some aspect of narrative writing craft, then give students the rest of the period to write, conference with you, and collaborate with their peers. During that time, they should focus some of their attention on applying the skill they learned in the mini-lesson to their drafts, so they will improve a little bit every day.

Topics for mini-lessons can include:

- How to weave exposition into your story so you don’t give readers an “information dump”

- How to carefully select dialogue to create good scenes, rather than quoting everything in a conversation

- How to punctuate and format dialogue so that it imitates the natural flow of a conversation

- How to describe things using sensory details and figurative language; also, what to describe…students too often give lots of irrelevant detail

- How to choose precise nouns and vivid verbs, use a variety of sentence lengths and structures, and add transitional words, phrases, and features to help the reader follow along

- How to start, end, and title a story

Step 10: Final Revisions and Edits

As the unit nears its end, students should be shifting away from revision , in which they alter the content of a piece, toward editing , where they make smaller changes to the mechanics of the writing. Make sure students understand the difference between the two: They should not be correcting each other’s spelling and punctuation in the early stages of this process, when the focus should be on shaping a better story.

One of the most effective strategies for revision and editing is to have students read their stories out loud. In the early stages, this will reveal places where information is missing or things get confusing. Later, more read-alouds will help them immediately find missing words, unintentional repetitions, and sentences that just “sound weird.” So get your students to read their work out loud frequently. It also helps to print stories on paper: For some reason, seeing the words in print helps us notice things we didn’t see on the screen.

To get the most from peer review, where students read and comment on each other’s work, more modeling from you is essential: Pull up a sample piece of writing and show students how to give specific feedback that helps, rather than simply writing “good detail” or “needs more detail,” the two comments I saw exchanged most often on students’ peer-reviewed papers.

Step 11: Final Copies and Publication

Once revision and peer review are done, students will hand in their final copies. If you don’t want to get stuck with 100-plus papers to grade, consider using Catlin Tucker’s station rotation model , which keeps all the grading in class. And when you do return stories with your own feedback, try using Kristy Louden’s delayed grade strategy , where students don’t see their final grade until they have read your written feedback.

Beyond the standard hand-in-for-a-grade, consider other ways to have students publish their stories. Here are some options:

- Stories could be published as individual pages on a collaborative website or blog.

- Students could create illustrated e-books out of their stories.

- Students could create a slideshow to accompany their stories and record them as digital storytelling videos. This could be done with a tool like Screencastify or Screencast-O-Matic .

So this is what worked for me. If you’ve struggled to get good stories from your students, try some or all of these techniques next time. I think you’ll find that all of your students have some pretty interesting stories to tell. Helping them tell their stories well is a gift that will serve them for many years after they leave your classroom. ♦

Want this unit ready-made?

If you’re a writing teacher in grades 7-12 and you’d like a classroom-ready unit like the one described above, including slideshow mini-lessons on 14 areas of narrative craft, a sample narrative piece, editable rubrics, and other supplemental materials to guide students through every stage of the process, take a look at my Narrative Writing unit . Just click on the image below and you’ll be taken to a page where you can read more and see a detailed preview of what’s included.

What to Read Next

Categories: Instruction , Podcast

Tags: English language arts , Grades 6-8 , Grades 9-12 , teaching strategies

50 Comments

Wow, this is a wonderful guide! If my English teachers had taught this way, I’m sure I would have enjoyed narrative writing instead of dreading it. I’ll be able to use many of these suggestions when writing my blog! BrP

Lst year I was so discouraged because the short stories looked like the quick drafts described in this article. I thought I had totally failed until I read this and realized I did not fai,l I just needed to complete the process. Thank you!

I feel like you jumped in my head and connected my thoughts. I appreciate the time you took to stop and look closely at form. I really believe that student-writers should see all dimensions of narrative writing and be able to live in whichever style and voice they want for their work.

Can’t thank you enough for this. So well curated that one can just follow it blindly and ace at teaching it. Thanks again!

Great post! I especially liked your comments about reminding kids about the power of storytelling. My favourite podcasts and posts from you are always about how to do things in the classroom and I appreciate the research you do.

On a side note, the ice breakers are really handy. My kids know each other really well (rural community), and can tune out pretty quickly if there is nothing new to learn about their peers, but they like the games (and can remember where we stopped last time weeks later). I’ve started changing them up with ‘life questions’, so the editable version is great!

I love writing with my students and loved this podcast! A fun extension to this narrative is to challenge students to write another story about the same event, but use the perspective of another “character” from the story. Books like Wonder (R.J. Palacio) and Wanderer (Sharon Creech) can model the concept for students.

Thank you for your great efforts to reveal the practical writing strategies in layered details. As English is not my first language, I need listen to your podcast and read the text repeatedly so to fully understand. It’s worthy of the time for some great post like yours. I love sharing so I send the link to my English practice group that it can benefit more. I hope I could be able to give you some feedback later on.

Thank you for helping me get to know better especially the techniques in writing narrative text. Im an English teacher for 5years but have little knowledge on writing. I hope you could feature techniques in writing news and fearute story. God bless and more power!

Thank you for this! I am very interested in teaching a unit on personal narrative and this was an extremely helpful breakdown. As a current student teacher I am still unsure how to approach breaking down the structures of different genres of writing in a way that is helpful for me students but not too restrictive. The story mapping tools you provided really allowed me to think about this in a new way. Writing is such a powerful way to experience the world and more than anything I want my students to realize its power. Stories are how we make sense of the world and as an English teacher I feel obligated to give my students access to this particular skill.

The power of story is unfathomable. There’s this NGO in India doing some great work in harnessing the power of storytelling and plots to brighten children’s lives and enlighten them with true knowledge. Check out Katha India here: http://bit.ly/KathaIndia

Thank you so much for this. I did not go to college to become a writing professor, but due to restructuring in my department, I indeed am! This is a wonderful guide that I will use when teaching the narrative essay. I wonder if you have a similar guide for other modes such as descriptive, process, argument, etc.?

Hey Melanie, Jenn does have another guide on writing! Check out A Step-by-Step Plan for Teaching Argumentative Writing .

Hi, I am also wondering if there is a similar guide for descriptive writing in particular?

Hey Melanie, unfortunately Jenn doesn’t currently have a guide for descriptive writing. She’s always working on projects though, so she may get around to writing a unit like this in the future. You can always check her Teachers Pay Teachers page for an up-to-date list of materials she has available. Thanks!

I want to write about the new character in my area

That’s great! Let us know if you need any supports during your writing process!

I absolutely adore this unit plan. I teach freshmen English at a low-income high school and wanted to find something to help my students find their voice. It is not often that I borrow material, but I borrowed and adapted all of it in the order that it is presented! It is cohesive, understandable, and fun. Thank you!!

So glad to hear this, Nicole!

Thanks sharing this post. My students often get confused between personal narratives and short stories. Whenever I ask them to write a short story, she share their own experiences and add a bit of fiction in it to make it interesting.

Thank you! My students have loved this so far. I do have a question as to where the “Frog” story mentioned in Step 4 is. I could really use it! Thanks again.

This is great to hear, Emily! In Step 4, Jenn mentions that she wrote the “Frog” story for her narrative writing unit . Just scroll down the bottom of the post and you’ll see a link to the unit.

I also cannot find the link to the short story “Frog”– any chance someone can send it or we can repost it?

This story was written for Jenn’s narrative writing unit. You can find a link to this unit in Step 4 or at the bottom of the article. Hope this helps.

I cannot find the frog story mentioned. Could you please send the link.? Thank you

Hi Michelle,

The Frog story was written for Jenn’s narrative writing unit. There’s a link to this unit in Step 4 and at the bottom of the article.

Debbie- thanks for you reply… but there is no link to the story in step 4 or at the bottom of the page….

Hey Shawn, the frog story is part of Jenn’s narrative writing unit, which is available on her Teachers Pay Teachers site. The link Debbie is referring to at the bottom of this post will take you to her narrative writing unit and you would have to purchase that to gain access to the frog story. I hope this clears things up.

Thank you so much for this resource! I’m a high school English teacher, and am currently teaching creative writing for the first time. I really do value your blog, podcast, and other resources, so I’m excited to use this unit. I’m a cyber school teacher, so clear, organized layout is important; and I spend a lot of time making sure my content is visually accessible for my students to process. Thanks for creating resources that are easy for us teachers to process and use.

Do you have a lesson for Informative writing?

Hey Cari, Jenn has another unit on argumentative writing , but doesn’t have one yet on informative writing. She may develop one in the future so check back in sometime.

I had the same question. Informational writing is so difficult to have a good strong unit in when you have so many different text structures to meet and need text-dependent writing tasks.

Creating an informational writing unit is still on Jenn’s long list of projects to get to, but in the meantime, if you haven’t already, check out When We All Teach Text Structures, Everyone Wins . It might help you out!

This is a great lesson! It would be helpful to see a finished draft of the frog narrative arc. Students’ greatest challenge is transferring their ideas from the planner to a full draft. To see a full sample of how this arc was transformed into a complete narrative draft would be a powerful learning tool.

Hi Stacey! Jenn goes into more depth with the “Frog” lesson in her narrative writing unit – this is where you can find a sample of what a completed story arc might look. Also included is a draft of the narrative. If interested in checking out the unit and seeing a preview, just scroll down to the bottom of the post and click on the image. Hope this helps!

Helped me learn for an entrance exam thanks very much

Is the narrative writing lesson you talk about in https://www.cultofpedagogy.com/narrative-writing/

Also doable for elementary students you think, and if to what levels?

Love your work, Sincerely, Zanyar

Hey Zanyar,

It’s possible the unit would work with 4th and 5th graders, but Jenn definitely wouldn’t recommend going any younger. The main reason for this is that some of the mini-lessons in the unit could be challenging for students who are still concrete thinkers. You’d likely need to do some adjusting and scaffolding which could extend the unit beyond the 3 weeks. Having said that, I taught 1st grade and found the steps of the writing process, as described in the post, to be very similar. Of course learning targets/standards were different, but the process itself can be applied to any grade level (modeling writing, using mentor texts to study how stories work, planning the structure of the story, drafting, elaborating, etc.) Hope this helps!

This has made my life so much easier. After teaching in different schools systems, from the American, to British to IB, one needs to identify the anchor standards and concepts, that are common between all these systems, to build well balanced thematic units. Just reading these steps gave me the guidance I needed to satisfy both the conceptual framework the schools ask for and the standards-based practice. Thank you Thank you.

Would this work for teaching a first grader about narrative writing? I am also looking for a great book to use as a model for narrative writing. Veggie Monster is being used by his teacher and he isn’t connecting with this book in the least bit, so it isn’t having a positive impact. My fear is he will associate this with writing and I don’t want a negative association connected to such a beautiful process and experience. Any suggestions would be helpful.

Thank you for any information you can provide!

Although I think the materials in the actual narrative writing unit are really too advanced for a first grader, the general process that’s described in the blog post can still work really well.

I’m sorry your child isn’t connecting with The Night of the Veggie Monster. Try to keep in mind that the main reason this is used as a mentor text is because it models how a small moment story can be told in a big way. It’s filled with all kinds of wonderful text features that impact the meaning of the story – dialogue, description, bold text, speech bubbles, changes in text size, ellipses, zoomed in images, text placement, text shape, etc. All of these things will become mini-lessons throughout the unit. But there are lots of other wonderful mentor texts that your child might enjoy. My suggestion for an early writer, is to look for a small moment text, similar in structure, that zooms in on a problem that a first grader can relate to. In addition to the mentor texts that I found in this article , you might also want to check out Knuffle Bunny, Kitten’s First Full Moon, When Sophie Gets Angry Really Really Angry, and Whistle for Willie. Hope this helps!

I saw this on Pinterest the other day while searching for examples of narritives units/lessons. I clicked on it because I always click on C.o.P stuff 🙂 And I wasn’t disapointed. I was intrigued by the connection of narratives to humanity–even if a student doesn’t identify as a writer, he/she certainly is human, right? I really liked this. THIS clicked with me.

A few days after I read the P.o.C post, I ventured on to YouTube for more ideas to help guide me with my 8th graders’ narrative writing this coming spring. And there was a TEDx video titled, “The Power of Personal Narrative” by J. Christan Jensen. I immediately remembered the line from the article above that associated storytelling with “power” and how it sets humans apart and if introduced and taught as such, it can be “extraordinary.”

I watched the video and to the suprise of my expectations, it was FANTASTIC. Between Jennifer’s post and the TEDx video ignited within me some major motivation and excitement to begin this unit.

Thanks for sharing this with us! So glad that Jenn’s post paired with another text gave you some motivation and excitement. I’ll be sure to pass this on to Jenn!

Thank you very much for this really helpful post! I really love the idea of helping our students understand that storytelling is powerful and then go on to teach them how to harness that power. That is the essence of teaching literature or writing at any level. However, I’m a little worried about telling students that whether a piece of writing is fact or fiction does not matter. It in fact matters a lot precisely because storytelling is powerful. Narratives can shape people’s views and get their emotions involved which would, in turn, motivate them to act on a certain matter, whether for good or for bad. A fictional narrative that is passed as factual could cause a lot of damage in the real world. I believe we should. I can see how helping students focus on writing the story rather than the truth of it all could help refine the needed skills without distractions. Nevertheless, would it not be prudent to teach our students to not just harness the power of storytelling but refrain from misusing it by pushing false narratives as factual? It is true that in reality, memoirs pass as factual while novels do as fictional while the opposite may be true for both cases. I am not too worried about novels passing as fictional. On the other hand, fictional narratives masquerading as factual are disconcerting and part of a phenomenon that needs to be fought against, not enhanced or condoned in education. This is especially true because memoirs are often used by powerful people to write/re-write history. I would really like to hear your opinion on this. Thanks a lot for a great post and a lot of helpful resources!

Thank you so much for this. Jenn and I had a chance to chat and we can see where you’re coming from. Jenn never meant to suggest that a person should pass off a piece of fictional writing as a true story. Good stories can be true, completely fictional, or based on a true story that’s mixed with some fiction – that part doesn’t really matter. However, what does matter is how a student labels their story. We think that could have been stated more clearly in the post , so Jenn decided to add a bit about this at the end of the 3rd paragraph in the section “A Note About Form: Personal Narrative or Short Story?” Thanks again for bringing this to our attention!

You have no idea how much your page has helped me in so many ways. I am currently in my teaching credential program and there are times that I feel lost due to a lack of experience in the classroom. I’m so glad I came across your page! Thank you for sharing!

Thanks so much for letting us know-this means a whole lot!

No, we’re sorry. Jenn actually gets this question fairly often. It’s something she considered doing at one point, but because she has so many other projects she’s working on, she’s just not gotten to it.

I couldn’t find the story

Hi, Duraiya. The “Frog” story is part of Jenn’s narrative writing unit, which is available on her Teachers Pay Teachers site. The link at the bottom of this post will take you to her narrative writing unit, which you can purchase to gain access to the story. I hope this helps!

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published.

- For Schools

- For Teachers

- Teacher Hub

- Free resources

- For Seven Steppers

- NAPLAN Writing Success

- Free writing resources

- About Seven Steps

- Seven Steps and the Curriculum

- What are the Seven Steps?

- Success Stories

- In the Media

- Seven Steps Impact Report

- [FREE] Try Sizzling Starts

- Narrative Writing

- Persuasive Writing

- Informative Writing

No products in the cart.

- Your password must be 8 or more characters, including at least 1 upper case letter, 1 lower case letter and 1 number.

- Add new school

How to teach narrative writing

How do you teach students to write a great narrative text?

Narrative writing is much more than just fiction. It can be easy to assume that narrative writing and fiction are one and the same, but they’re not. Fiction describes imaginary events and/or people. Narrative writing is an account of connected events, regardless of whether they are real or not.

Did you know that most popular books, movies and fairy tales follow a similar narrative structure? Understanding this basic structure will improve your students’ narrative writing by giving them a framework around which to build their stories.

Teaching your students to write a narrative piece involves training them on the skills and techniques authors and writers use. You’ll need to help them understand what great narrative writing looks like and the skills writers use to create the biggest impact.

The Seven Steps chunking and skilled-based approach will help any new learner to improve and become masters of story-telling.

Free Narrative Writing Resources

Writing samples and exemplars

See the difference the Seven Steps can make with student samples and discover how professionals use the Seven Steps techniques in narrative texts.

View narrative writing samples >

Planning for narrative writing

Explore ready-made lesson plans, activities and planning exemplars to discover how to teach the key concepts behind each Step.

Each lesson plan includes relevant links to the Australian Curriculum and NAPLAN marking criteria, plus a learning intention and success criteria to assist with planning and assessment.

View lesson plans and activities >

Narrative picture writing prompts

Fun and quick writing practice to develop your students’ writing and to get students’ creative juices flowing.

Use them daily or weekly to build students’ confidence in their narrative writing and as a fun way to practise one Step at a time.

View writing prompts >

Comprehensive step-by-step resources.

Transform narrative writing

Narrative Writing Manual

Packed with practical, time-saving classroom resources, this manual makes planning and implementing the Seven Steps just as fun as learning it!

Includes a user-friendly digital file, plus a photocopy and intranet licence for your entire school.

Teacher Hub: Narrative Writing Course

Step-by-Step teaching modules to guide your implementation process. The Narrative Writing Course in Teacher Hub gives you a clear pathway to learn, teach, apply and assess narrative writing.

Discover how to get the creative juices flowing in your writing lessons and create unique narrative texts.

Teaching tips for Narrative writing

Explore more! Make narrative writing fun with tips and expert insights.

Explore more of Seven Steps

- About the Voiceless Grants Program

- Grants Criteria

- Expression of Interest Form

- 2023 Grant Recipients

- 2022 Grant Recipients

- 2004-2017 Grant Recipients

- Grants Frequently Asked Questions

- Prizes & Sponsorships

- Testimonials

- 2024 Grant Recipients

- Factory Farming

- Live Export

- Battery Hens

- Broiler Chickens

- Animal Sentience

- Animal Welfare Office

- Puppy Farming

- Truth in Labelling

- Animal Cruelty

Lesson Seven: English, Yr 7/9

Introduction to narrative writing.

Curriculum links: Year 7 – ACELY1721 Year 9 – ACELT1633

Resources you will need

- Lesson 7 Narrative Writing PowerPoint slides

- Animal Protection Encyclopedia

Lesson structure

- Explain to students that the second type of writing that could be assessed in the NAPLAN writing assessment for Years 7 and 9 is Narrative Writing.

- Run through the Lesson 7 Narrative Writing PowerPoint slides .

- Using the Lesson 7 Narrative Writing PowerPoint slides , capture student interest by talking about the universal nature of storytelling. Brainstorm as a class, ‘what makes a great story’. This could be run as a ‘think, pair, share’ activity, or with students on their own.

- Ask students to share examples of their favourite stories (texts), and consider what they hold in common. Possible answers may include engaging storylines, 3D characters, relatable moments, evocative language and unique structure.

- Students may like to brainstorm different stories with animals in them, and consider what is unique and engaging about these stories with the featured animals.

- Ask the question – ‘what is narrative writing?’ Invite students to share their responses, and then as a class read the definition provided by ACARA on the slides.

- Show students the ACARA website, and explain that all information related to NAPLAN is publicly available and can be accessed by anyone who is interested.

- Discuss the words in bold text in the definition on the PowerPoint slide. Ask students how this compares to their previous conception of ‘narrative writing’. Recap/clarify/explore with students, what makes good narrative writing.

- You may also like to discuss some of the points on the slide relating to the idea of ‘good’ narrative writing.

- Use sticky notes, and have students write down as many ideas as they can in relation to the question: ‘Where can you draw inspiration for your imaginative writing?’ Each sticky note should have a different idea. Students should put the notes around the room, reading the notes of other students. Refer students to the PowerPoint slides, where ACARA provides some specific suggestions.

SHARE THIS ON:

Australian curriculum alignment, join the voiceless community.

For academics, advocates, teachers and students, animal lovers, animal lawyers and everyone in between! Sign up below to learn more about our Voiceless Grants Program, our free library of resources on Animal Protection Education and Animal Law Education and other Voiceless related tidbits.

- First Name *

- Last Name *

- High School Education

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Thank you for providing your email. This allows us to record the number of downloads per resource, and determine its relative reach.

By downloading this file you agree to join our email list in accordance with our terms & conditions and privacy policy .

Looking to publish? Meet your dream editor, designer and marketer on Reedsy.

Find the perfect editor for your next book

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Guides • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Nov 22, 2023

Story Structure: 7 Types All Writers Should Know

Nothing makes the challenging task of writing a novel feel more attainable than adopting a story structure to help you plot your narrative.

While using a pre-existing blueprint might make you worry about ending up with a formulaic, predictable story, you can probably analyze most of your favorite books using various narrative structures that writers have been using for decades (if not centuries)!

This post will reveal seven distinct story structures that any writer can use to build a compelling narrative. But first…

What is story structure?

Story structure is the order in which plot events are told to the reader or audience. While stories can be told in a wide variety of ways, most Western story structures commonly share certain elements: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution.

A tightly controlled structure will answer a reader's questions, provide a climax followed by resolution and information at the end of the story , further the characters’ development , and unravel any central conflicts . In other words, it's responsible for a satisfying narrative experience that accomplishes the author’s aims.

Writing is an art, but if there’s one part of the craft that’s closer to science, this would be it. Become a master of story structure, and you will have the world at your feet.

Classic story structure

When people discuss different story structures, they often talk about the different frameworks used to analyze stories. When you boil them all down, all stories have certain shared elements.

Elements of classic story structure:

- Exposition. This first part establishes a protagonist's normal life and greater desires, and usually culminates in the inciting incident.

- Rising action. The protagonist pursues their new goal and is tested along the way.

- Climax. Our hero achieves their goal — or so they think!

- Falling action. The hero now must deal with the consequences of achieving their goal.

- Resolution. The conclusion tying together the plot, character arcs, and themes.

These are all common ‘ beats ’ to most stories. It can be easier to see these moments in genres with higher stakes (such as a military thriller), but you’ll find them in almost any type of story.

GET ACCOUNTABILITY

Meet writing coaches on Reedsy

Industry insiders can help you hone your craft, finish your draft, and get published.

Seven Story Structures Every Writer Should Know

Now that we’ve established the most essential components of story, let’s look at seven of the most popular story structures used by writers — and how they deploy these components.

- Freytag's Pyramid

- The Hero's Journey

- Three Act Structure

- Dan Harmon's Story Circle

- Fichtean Curve

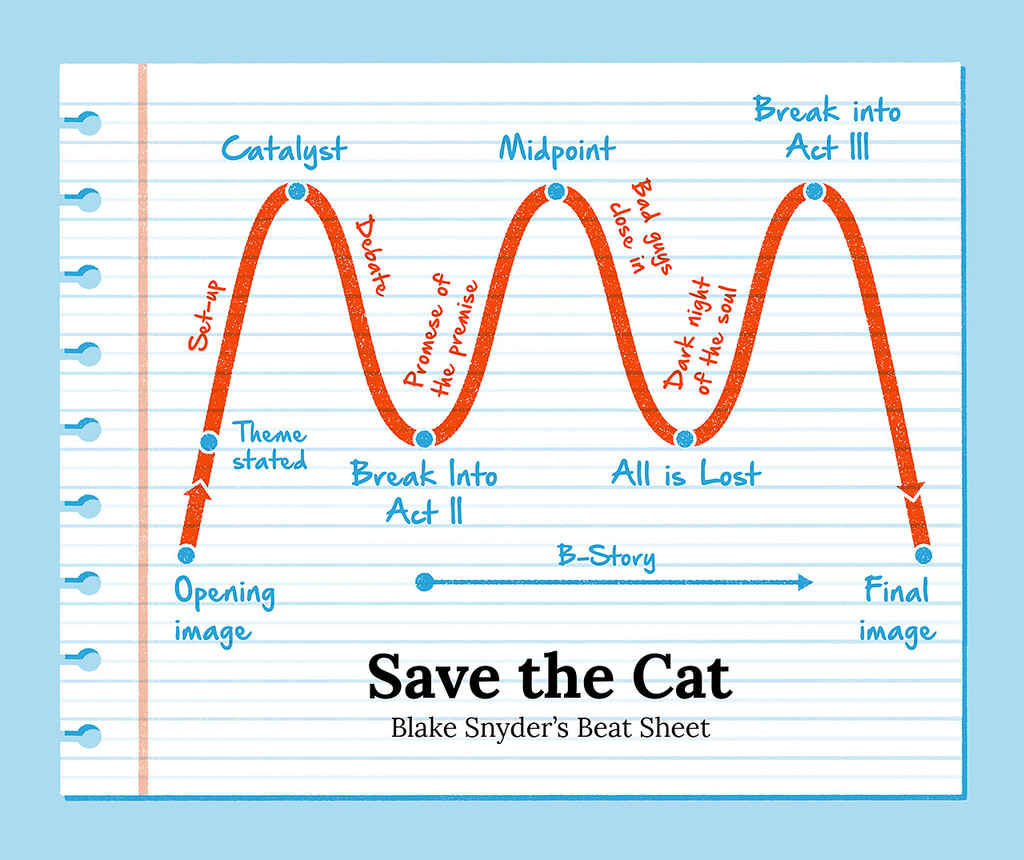

- Save the Cat Beat Sheet

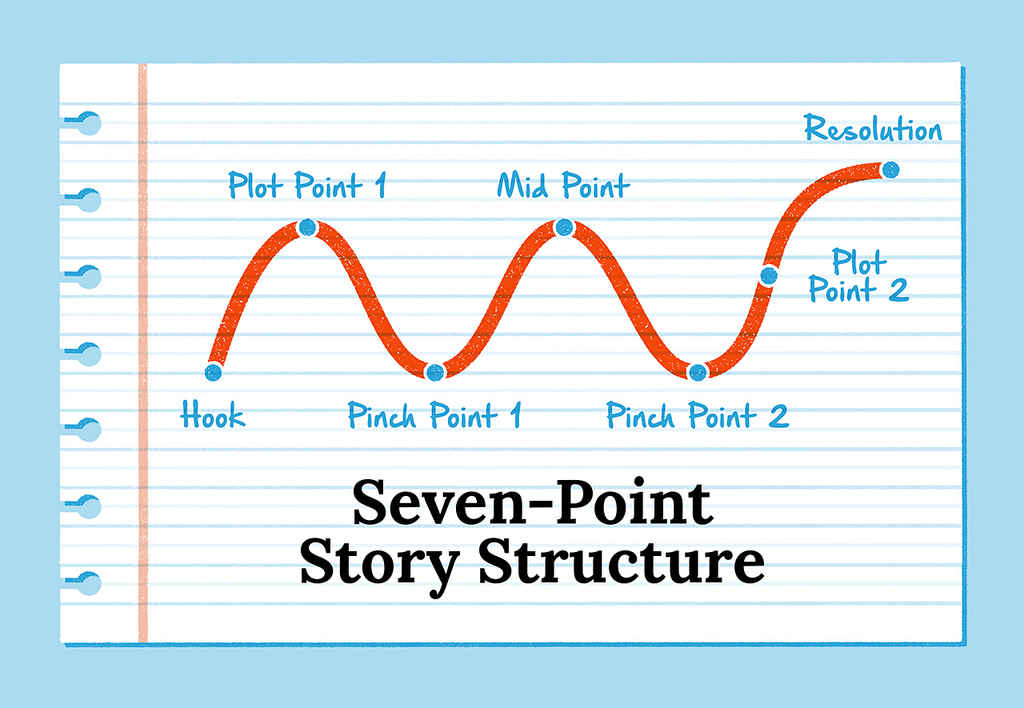

- Seven-Point Story Structure

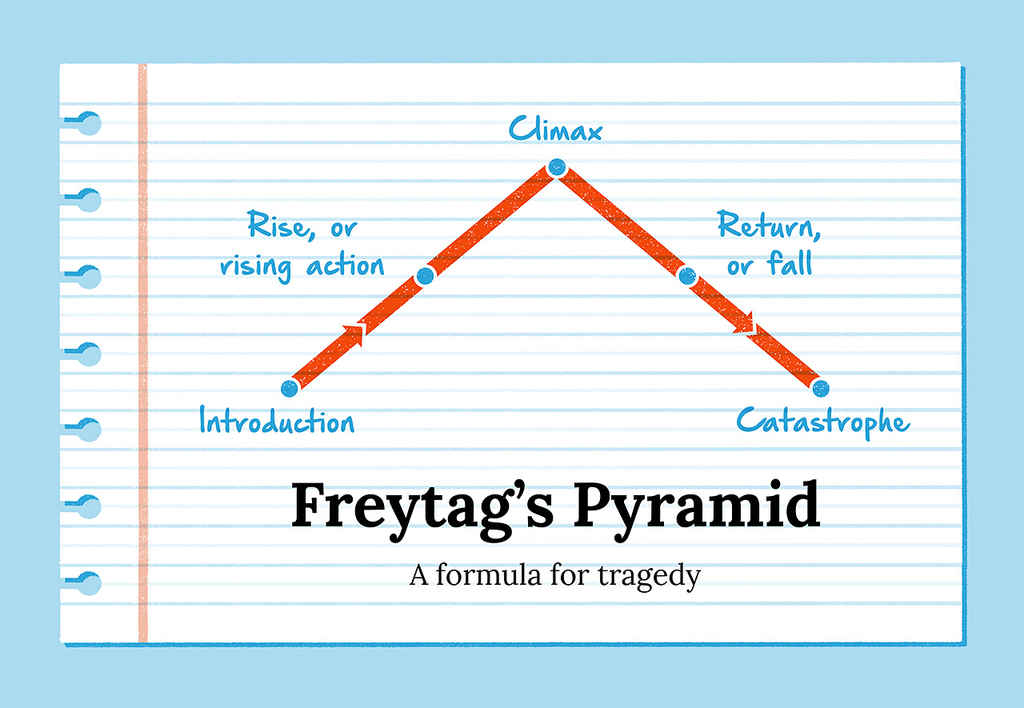

1. Freytag’s Pyramid

- Introduction. The status quo is established; an inciting incident occurs.

- Rise, or rising action. The protagonist actively pursues their goal. The stakes heighten.

- Climax. A point of no return, from which the protagonist can no longer go back to the status quo.

- Return, or fall. In the aftermath of the climax, tension builds, and the story heads inevitably towards...

- Catastrophe. The protagonist is brought to their lowest point. Their greatest fears have come true.

This structural model is less frequently used in modern storytelling, partly due to readers’ limited appetite for tragic narratives (although you can still spot a few tragic heroes in popular literature today). By and large, commercial fiction, films, and television will see a protagonist overcome their obstacles to find some small measure of success. That said, it’s still useful to understand the Pyramid as a foundational structure in Western literature — and you will still see it occasionally in the most depressing contemporary tales.

To learn more, read our full guide on Freytag’s Pyramid .

If you struggle to structure a novel, sign up for our How to Write a Novel course to finish a novel in just 3 months.

NEW REEDSY COURSE

How to Write a Novel

Enroll in our course and become an author in three months.

2. The Hero’s Journey

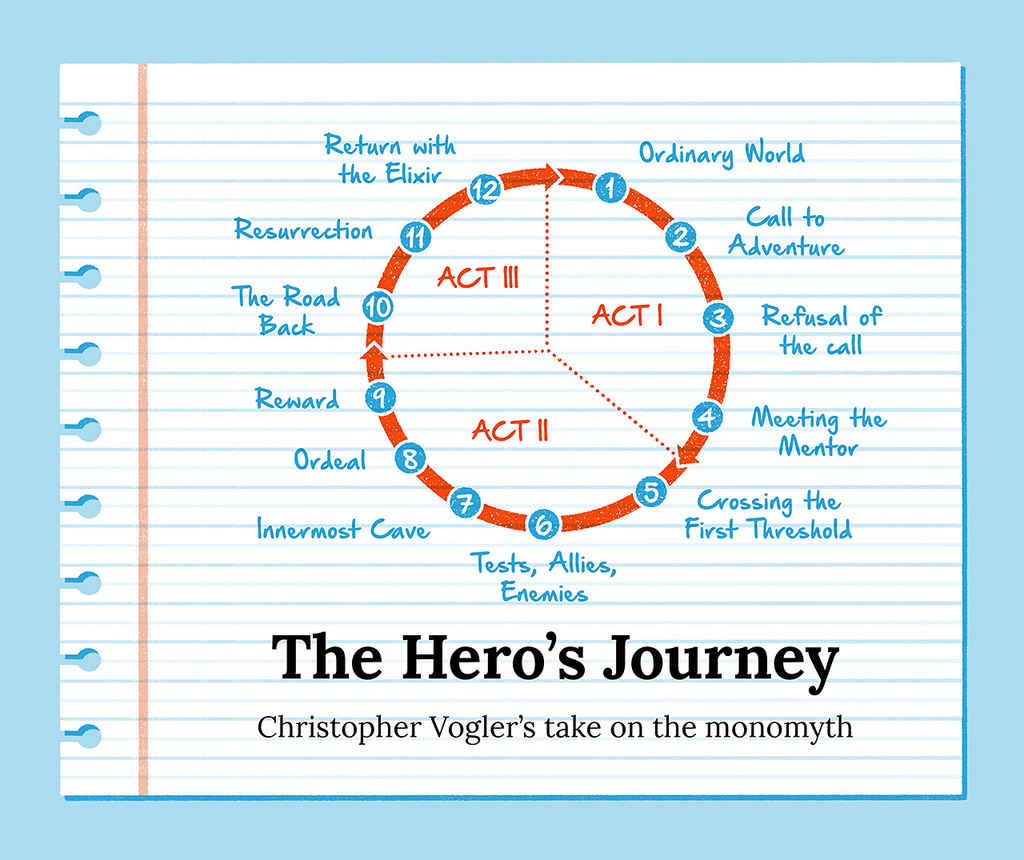

Campbell’s original structure uses terminology that lends itself well to epic tales of bravery and triumph — with plot points like “Belly of the Whale,” “Woman as the Temptress,” and “The Magic Flight.” To make The Hero’s Journey more accessible, Disney executive Christopher Vogler created a simplified version that has become popular amongst mainstream storytellers.

Here, we’ll look at Vogler’s streamlined, 12-step version of The Hero’s Journey.

- The Ordinary World. The hero’s everyday life is established.

- The Call of Adventure. Otherwise known as the inciting incident.

- Refusal of the Call. For a moment, the hero is reluctant to take on the challenge.

- Meeting the Mentor. Our hero meets someone who prepares them for what lies ahead — perhaps a parental figure, a teacher, a wizard, or a wise hermit.

- Crossing the First Threshold. The hero steps out of their comfort zone and enters a ‘new world.’

- Tests, Allies, Enemies. Our protagonist faces new challenges — and maybe picks up some new friends. Think of Dorothy on the Yellow Brick Road.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave. The hero gets close to their goal. Luke Skywalker reaches the Death Star.

- The Ordeal. The hero meets (and overcomes) their greatest challenge yet.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword). The hero obtains something important they were after, and victory is in sight.

- The Road Back. The hero realizes that achieving their goal is not the final hurdle. In fact, ‘seizing the sword’ may have made things worse for them.

- Resurrection. The hero faces their final challenge — a climactic test that hinges on everything they’ve learned over their journey.

- Return with the Elixir. Having triumphed, our protagonist returns to their old life. Dorothy returns to Kansas; Iron Man holds a press conference to blow his own trumpet .

While Vogler’s simplified steps still retain some of Campbell’s mythological language with its references to swords and elixirs, the framework can be applied to almost any genre of fiction. To see how a ‘realistic’ story can adhere to this structure, check out our guide to the hero’s journey in which we analyze Rocky through this very lens.

FREE OUTLINING APP

The Reedsy Book Editor

Use the Boards feature to plan, organize, or research anything.

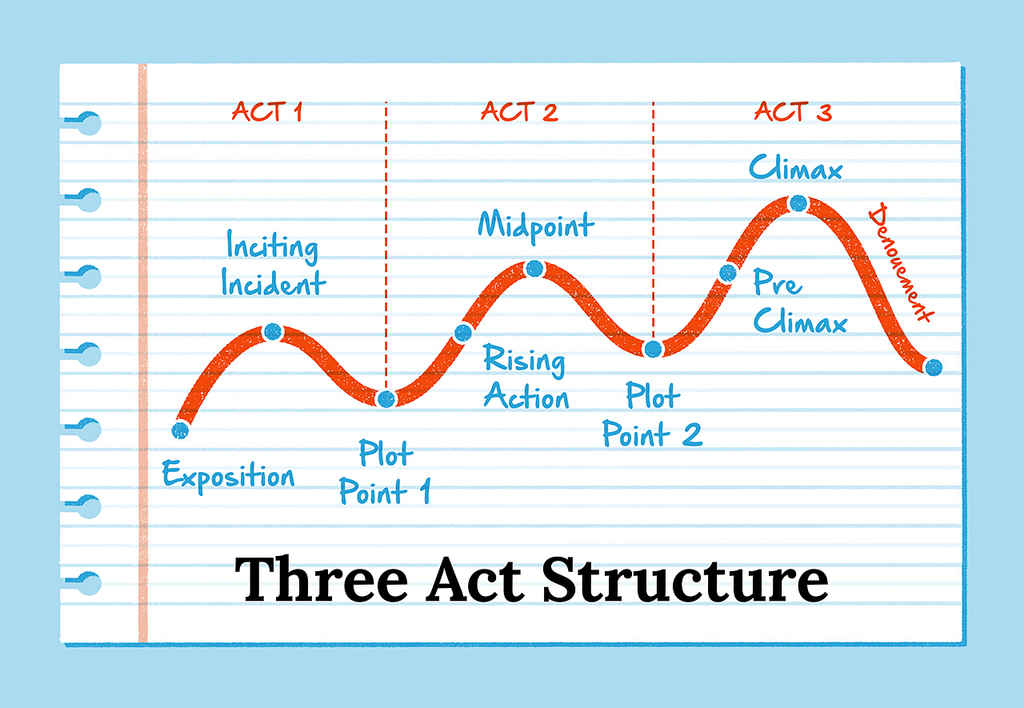

3. Three Act Structure

Act 1: Setup

- Exposition . The status quo or ‘ordinary world’ is established.

- Inciting Incident. An event that sets the story in motion.

- Plot Point One. The protagonist decides to tackle the challenge head-on. She ‘crosses the threshold,’ and the story is now truly moving.

Act 2: Confrontation

- Rising Action. The story's true stakes become clear; our hero grows familiar with her ‘new world’ and has her first encounters with some enemies and allies. (see Tests, Allies, Enemies)

- Midpoint. An event that upends the protagonist’s mission. (Similar to the climax in Freytag’s pyramid)

- Plot Point Two. In the wake of the disorienting midpoint, the protagonist is tested — and fails. Her ability to succeed is now in doubt.

Act 3: Resolution

- Pre Climax. The night is darkest before dawn. The protagonist must pull herself together and choose between decisive action and failure.

- Climax. She faces off against her antagonist one last time. Will she prevail?

- Denouement. All loose ends are tied up. The reader discovers the consequences of the climax. A new status quo is established.

When we speak about a confrontation with an antagonist, this doesn’t always mean a fight to the death. In some cases, the antagonist might be a love rival, a business competitor, or merely an internal or environmental conflict that our protagonist has been struggling with the entire story.

If you’re interested in using this model to plot your own story, read our guide to the three-act structure , and be sure to sign up to our free course on the subject.

FREE COURSE

How to Plot a Novel in Three Acts

In 10 days, learn how to plot a novel that keeps readers hooked

4. Dan Harmon's Story Circle

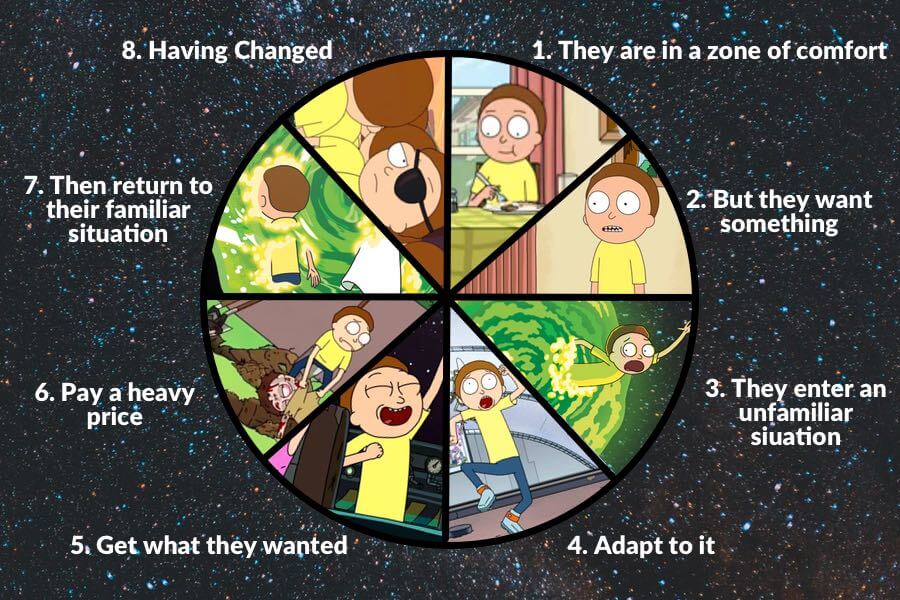

Another variation on Campbell’s monomyth structure, the Story Circle is an approach developed by Rick and Morty co-creator Dan Harmon. Again, heavily inspired by the Hero's Journey, the benefit of Harmon's approach is its focus on the protagonist's character arc. Instead of referring to abstract concepts like 'story midpoint' and 'denouement', each beat in the story circle forces the writer to think about the character's wants and needs.

- A character is in a zone of comfort... This is the establishment of the status quo.

- But they want something... This 'want' could be something long-standing and brought to the fore by an inciting incident.

- They enter an unfamiliar situation... The protagonist must do something new in their pursuit of the thing they want.

- Adapt to it... Faced with some challenges, they struggle then begin to succeed.

- Get what they wanted... Usually a false victory.

- Pay a heavy price for it... They realize that what they 'wanted' wasn't what they 'needed'.

- Then return to their familiar situation... armed with a new truth.

- Having changed... For better or worse.

Created by a writer whose chosen medium is the 30-minute sitcom, this structure is worded in a way that sidesteps the need for a protagonist to undergo life-changing transformations with each story. After all, for a comedy to continue for six seasons (and a movie) its characters can't completely transform at the end of each episode. They can, however, learn small truths about themselves and the world around them — which, like all humans, they can quickly forget about if next week's episode calls for it.

To learn more and see this structure applied to an episode of Rick and Morty, check out our full post on Dan Harmon's Story Circle .

Side note: for this kind of character-driven plot (and, indeed, for all of these structures), you're going to want to know you're protagonist inside and out. Why not check out some of our character development exercises for help fleshing your characters out, like the profile template below.

FREE RESOURCE

Reedsy’s Character Profile Template

A story is only as strong as its characters. Fill this out to develop yours.

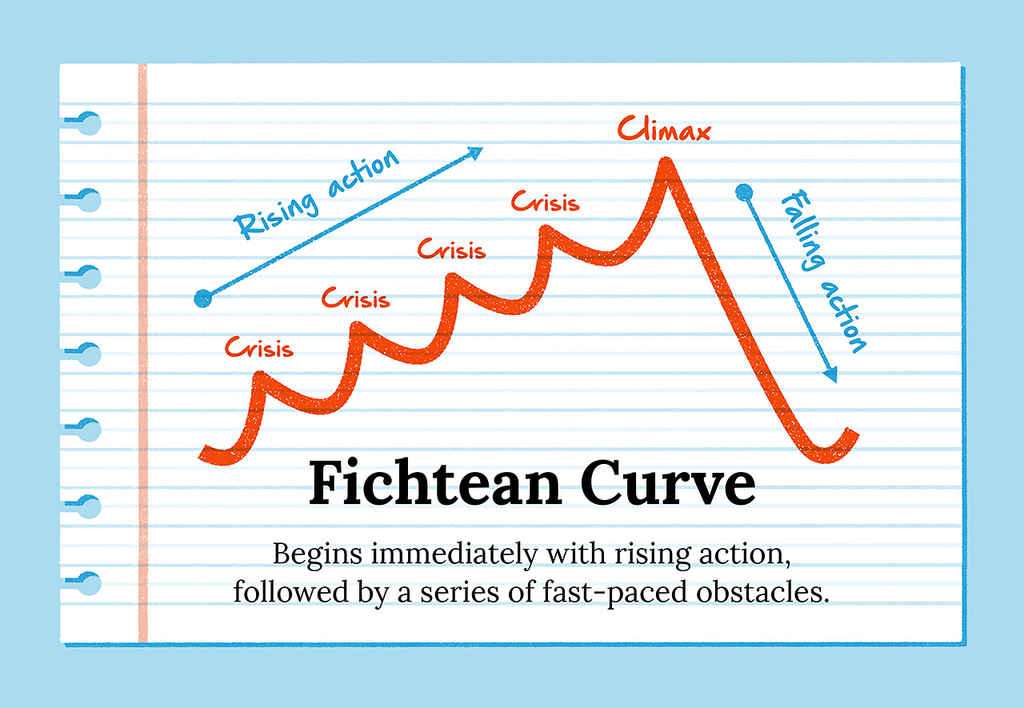

5. Fichtean Curve