Major Essay

When declaring a major in Physics, students must submit an essay to their academic advisor for approval. This essay should be 250 - 500 words and should include:

A statement of your goals in pursuing a physics major;

Areas of physics that represent your greatest interests (e.g., astrophysics);

A brief description of other academic concentrations you are planning (e.g., a minor in mathematics) and how those areas complement your interests in physics;

A description of your plans after graduation.

- Printer-friendly version

- " class="home">

- " class="programs">

- " class="about">

- Why Physics?

- Introduction

Why Study Physics?

- Physics Careers

- Physics at Cornell

There are hundreds of possible college majors and minors. So why should you study physics?

Physics is interesting.

Physics helps us to understand how the world around us works , from can openers, light bulbs and cell phones to muscles, lungs and brains; from paints, piccolos and pirouettes to cameras, cars and cathedrals; from earthquakes, tsunamis and hurricanes to quarks, DNA and black holes. From the prosaic . . . to the profound . . . to the poetic. . .

Physics helps us to organize the universe. It deals with fundamentals, and helps us to see the connections between seemly disparate phenomena.

Physics gives us powerful tools to help us to express our creativity , to see the world in new ways and then to change it.

Physics is useful.

Physics provides quantitative and analytic skills needed for analyzing data and solving problems in the sciences, engineering and medicine, as well as in economics, finance, management, law and public policy.

Physics is the basis for most modern technology , and for the tools and instruments used in scientific, engineering and medical research and development. Manufacturing is dominated by physics-based technology.

Physics helps you to help others. Doctors that don’t understand physics can be dangerous. Medicine without physics technology would be barbaric. Schools without qualified physics teachers cut their students off from a host of well-respected, well paying careers.

Students who study physics do better on SAT, MCAT and GRE tests. Physics majors do better on MCATs than bio or chem majors .

Majoring in physics provides excellent preparation for graduate study not just in physics, but in all engineering and information/computer science disciplines; in the life sciences including molecular biology, genetics and neurobiology; in earth, atmospheric and ocean science; in finance and economics; and in public policy and journalism.

Physics opens the door to many career options.

More options, in fact, than almost any other college subject. Conversely, not taking physics closes the door to more career options. You can't become an engineer or a doctor without physics; you’re far less likely to get a job in teaching; your video games will be boring and your animated movies won’t look realistic; and your policy judgments on global warming will be less compelling.

College and corporate recruiters recognize the value of physics training.

Although the number of job ads specifically asking for physicists is smaller than, e.g., for engineers, the job market for those with skills in physics is more diverse and is always strong .

Because physics encourages quantitative, analytical and “big picture” thinking, physicists are more likely to end up in top management and policy positions than other technical professionals. Of the three top science-related positions in the U.S. government, two - Energy Secretary and Director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy - are currently held by physicists.

Physics is challenging.

This is one aspect that scares off many students. But it is precisely one of the most important reasons why you should study physics!

All of us - including professional physicists - find college physics courses challenging, because they require us to master the many concepts and skills that make training in physics so valuable in such a wide range of careers.

This also means that physics is much harder to learn after college (on your own or on the job) than other subjects like history or psychology or computer programming. You’ll get the most bang for your college buck if you take physics and other hard-to-learn subjects in your undergraduate years. You don't need to earn As or even Bs. You just need to learn enough to have a basis for future learning and professional growth.

Learn more about Physics at Cornell .

Why Study Physics?

The goal of physics is to understand how things work from first principles. We offer physics courses that are matched to a range of goals that students may have in studying physics -- taking elective courses to broaden one's scientific literacy, satisfying requirements for a major in the sciences or engineering, or working towards a degree in physics or engineering physics. Courses in physics reveal the mathematical beauty of the universe at scales ranging from subatomic to cosmological. Studying physics strengthens quantitative reasoning and problem solving skills that are valuable in areas beyond physics.

Where do I start?

- Students who have never studied physics before and would like a broad introduction should consider one of the introductory seminar courses in Physics or Applied Physics. Those interested in astronomy and astrophysics might enjoy PHYSICS 15, 16 or 17, which is intended for nontechnical majors.

- Students considering a career in science or engineering should start with the PHYSICS 20 & 40 series or PHYSICS 61, 71, 81 .

- The PHYSICS 20 series assumes no background in calculus, and is intended primarily for those who are majoring in the biological sciences. However, such students who have AP credit in calculus or physics should consider taking the PHYSICS 40 series, which will provide a depth and emphasis on problem solving that is of significant value in biological research, which today involves considerable physics-based technology.

- For those intending to major in engineering or the physical sciences, or simply wishing a stronger background in physics, the department offers the PHYSICS 40 series and PHYSICS 61, 71, 81 . Either of these series will satisfy the entry-level physics requirements of any Stanford major. However, students majoring in Physics or Engineering Physics are required to take PHYSICS 61, 71, 81 -- possibly after completing PHYSICS 41 and 43.

- PHYSICS 61, 71, 81 courses are intended for those who have already taken a physics course at the level of PHYSICS 41 and 43, or at least have a strong background in mechanics, some background in electricity and magnetism, and a strong background in calculus. To determine whether you are prepared for PHYSICS 61, take the the Physics Placement Diagnostic .

- The PHYSICS 40 series begins with PHYSICS 41 (mechanics), which is offered as a 4-unit course in both Autumn and Winter quarters, and continues with PHYSICS 43 (electricity and magnetism) in both Winter and Spring quarters, and PHYSICS 45 (thermodynamics and optics) in Autumn quarter.

- Beginning in academic year 2023/2024, a five-unit version of PHYSICS 41 is offered in the Winter quarter: PHYSICS 41E (Extended). This course is designed to enable students who have had little or no high school physics background to succeed in physics.

- The PHYSICS 61, 71, 81 series begins in the Autumn quarter (only) with special relativity and a deeper dive into mechanics.

- While most students are recommended to begin with mechanics in the PHYSICS 40 series (PHYSICS 41 or 41E), those who have had strong physics preparation in high school (such as a score of at least 4 on the Physics Advanced Placement C exam) may be ready to start with PHYSICS 45 in Autumn quarter (and then take PHYSICS 43 in the Winter quarter), or to start with PHYSICS 61 in the Autumn.

- Students are individually advised on the best entry point into either the PHYSICS 40 series or PHYSICS 61, 71, 81 on the basis of their score on the Physics Placement Diagnostic , which is available online.

- Sustainability

Physics & Astronomy

Why major in physics.

An essay by Patrick Madigan, Bates physics alum

I wanted to let you know how physics has helped me throughout my career. I’ve written below what is basically an historical account of what I’ve done since graduating and the items that I needed to become proficient in to be successful. In all of these subjects, I relied on the basics that I learned in physics to help me quickly understand and apply the knowledge to solve the problem. I hope this helps people who are considering majoring in physics.

I liked math in High School and took calculus as a senior but it was only when I took physics that math had real value to me. In physics class we put mathematics to work actually solving problems and with calculus the problems were much more real. I never understood math for math’s sake. I took a PG year at The Lawrenceville School in New Jersey where I took the BC version of AP Calculus and AP Physics. I really enjoyed AP Physics at Lawrenceville because with calculus the problems became more interesting and the more difficult. I interviewed with George Ruff when I visited Bates and had a good feeling about the program. My family wanted me to major in Geo-physics since the family knew someone that had a very prestigious job with Exxon. I didn’t know exactly what I was going to do with a degree in physics but I didn’t have much interest in Geology.

My first job after graduation was at Hamilton Standard, a division of United Technologies which makes electronic engine and flight controls for military and commercial aircraft. I was hired to perform EMI (Electromagnetic Interference), Lightning and Nuclear Hardness testing at the system, subsystem and in some cases the electronic component level. I was chosen for the job because with my degree I understood the electromagnetic spectrum, how waves interact with different size apertures based on wavelength, how impedance is affected by frequency, and other general rules of E&M. We designed electronic engine controls which could withstand the plane being struck by lightning through a balance of countermeasures of shielding and peak voltage clamping at the inputs. A lightning strike is comprised of high and low frequency components that require very different solutions, something that Electrical Engineers didn’t have much appreciation for. The nuclear hardness testing consisted of bombarding electronic components with Gamma radiation or neutrons from the Sandia Pulse Reactor (SPUR) to determine survivability during a nuclear strike. The bulk of this work was done for the Stealth Bomber and similar aircraft.

After four years I left Hamilton and started a company that manufactures plastic packaging. In the early years the company primarily made aluminum molds so I learned how to design (CAD, Solid Modeling) and machine aluminum (CAM, CNC Machines). Along the way my background in mechanics and E&M helped me quickly understand electronic data communications, how cutting tool geometries work, radial cutting speeds, chip loads etc. The plastic forming process consists of heating sheet plastic material to the edge of liquid state, forming the material over the aluminum molds which are water cooled to remove the heat and therefore set the material in the formed shape. This required installing large compressed air systems and chilled water systems. Background knowledge in thermodynamics helped me better understand what was happening during the forming process because I understood heat flow, heat density, heat capacities of different materials etc. When purchasing some of the larger systems I was able to push for more efficient designs and create systems that had two uses. For example our compressed air system rejected enough thermal energy to heat the factory in the cooler months.

Along with installing manufacturing infrastructure I needed a system to keep track of manufactured items. For example, the system needed to keep track of an order for 10,000 items manufactured over several days by two people, each on a different shift, with a specific amount of material. How much total time did this take? How much Material? How much scrap was there? Did the job run at the estimated level? What was in inventory? What was on order? I found out years later that this is called an ERP system but 25 years ago I built an industry specific one out of need. My physics background allowed me to take a systematic approach to solve complex business issues.

A great book I read along the way was The Goal. It was written by Dr. Eliyahu Goldratt, a physicist and philosopher, and looks at business as a constraint problem making business seem more scientific ( http://www.goldratt.com ). The approach is similar to the Lean Manufacturing principles made famous by the Toyota Production System (TPS). Both of these approaches treat business as a system that first needs to be modeled and then can be improved by adjusting the model. I think anyone who majors in physics would be extremely comfortable with this approach. More and more businesses have realized that they need to approach their particular market this way if they are ever going to make progress in becoming “best in class”.

Finally, there are a lot of people in business that struggle with numbers. Certainly any physics graduate can easily handle the kind of numbers and structures found on a Profit and Loss Statement. With so much specialization these days, a typical physics student is the opposite with a background in how many things work.

Future Students

Majors and minors, course schedules, request info, application requirements, faculty directory, student profile.

What You Need to Know About Becoming a Physics Major

Physics majors study matter and energy, and develop strong critical thinking skills along the way.

Becoming a Physics Major

Getty Images

Studying physics requires a strong background in mathematics.

A physics major studies questions about the universe while learning skills that prepare them for a variety of career paths. With technologies from X-rays to roller coasters involving physics, students can see the applications of their field in many parts of their lives. Physics students have the opportunity to confront complex topics and sharpen their problem-solving abilities.

What Is a Physics Major?

A physics major is a science degree path that helps explain how the world works and how the universe is structured. Majors study matter and energy and gain exposure to both classical and modern theories in the field. Students also spend time completing experiments in a lab setting. With the scale of topics relevant to physics ranging from subatomic particles to all of the visible universe, majors have plenty to explore and learn. Physics majors should also plan to learn about the connections between physics and other sciences, such as astronomy, chemistry and biology .

Common Coursework Physics Majors Can Expect

Physics majors usually start with an introductory course that covers topics such as Newton’s laws of motion, kinematics and rotational motion. Studying physics requires a strong background in mathematics, and students should expect to complete coursework in calculus and differential equations, for instance. Students may be able to take a placement test to determine where to start in their program.

Some schools offer degrees in applied physics that focus on parts of the field more directly applicable to jobs, rather than research. Some schools offer both Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science degree options, with the former having fewer course requirements and more flexibility. Undergraduates can also pursue research at their college or university, working with faculty on projects related to electron diffraction, nanotechnology or dark matter, among other topics.

How to Know if This Major Is the Right Fit for You

Physics students should be curious about the mathematical intricacies that underlie the universe and be prepared to work on complex problems. If you are an adept mathematician who’s excited to develop strong problem-solving and critical thinking skills, a physics major could be the right fit for you. Students interested in other sciences might enjoy physics for its links to fields including chemistry, seismology and oceanography. Prospective physics majors might also consider exploring coursework in engineering and computer science .

Pick the Perfect Major

Discover the perfect major for you based on your innate wiring. The Innate Assessment sets you up for success by pairing you with majors, colleges and careers that fit your unique skills and abilities.

What Can I Do With a Physics Major?

Physics majors are strong problem solvers who can apply their skills to a variety of fields. Some graduates go on to teach in middle and high schools, while others find jobs in engineering and computer science, for example. Most students who study physics as undergraduates do not pursue graduate school in physics or astronomy, according to the American Physical Society . There are opportunities for students interested in further study in the field, although admission can be competitive. Physics graduates can also pursue graduate study in engineering or enroll in law school or medical school, among other professional and higher education opportunities.

Schools Offering a Physics Major

Check out some schools below that offer physics majors and find the full list of schools here that you can filter and sort.

2024 Best Colleges

Search for your perfect fit with the U.S. News rankings of colleges and universities.

College Admissions: Get a Step Ahead!

Sign up to receive the latest updates from U.S. News & World Report and our trusted partners and sponsors. By clicking submit, you are agreeing to our Terms and Conditions & Privacy Policy .

Ask an Alum: Making the Most Out of College

You May Also Like

How to decide if an mba is worth it.

Sarah Wood March 27, 2024

What to Wear to a Graduation

LaMont Jones, Jr. March 27, 2024

FAFSA Delays Alarm Families, Colleges

Sarah Wood March 25, 2024

Help Your Teen With the College Decision

Anayat Durrani March 25, 2024

Toward Semiconductor Gender Equity

Alexis McKittrick March 22, 2024

March Madness in the Classroom

Cole Claybourn March 21, 2024

20 Lower-Cost Online Private Colleges

Sarah Wood March 21, 2024

How to Choose a Microcredential

Sarah Wood March 20, 2024

Basic Components of an Online Course

Cole Claybourn March 19, 2024

Can You Double Minor in College?

Sarah Wood March 15, 2024

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

A 200+ Word “Why Major” Essay Example and Analysis

This article was written based on the information and opinions presented by Hale Jaeger in a CollegeVine livestream. You can watch the full livestream for more info.

What’s Covered:

250 word essay example, start with an anecdote, but avoid cliches, include smooth transitions and be specific, do your research and avoid overusing phrases, be concise and emphasize school fit.

In this article, we will focus on a prompt from Duke University that is specific to the Pratt School of Engineering.

If you are applying to the Pratt School of Engineering as a first year applicant, please discuss why you want to study engineering and why you would like to study at Duke. (250 words).

As opposed to a 100 word essay, 250 words gives you a little more space to write about your interests. Another thing to note about this prompt is that it is asking two questions: “why do you want to study at this school in particular?” and “why do you want to study engineering?”

The extra words give you enough room to talk about the type of engineering you’re interested in, Duke specific resources, and how you grew your interest in engineering over time. Here we will go through an example of a response to this prompt. Then for each paragraph, we’ll analyze what the essay does well and where it could be improved.

“One Christmas morning when I was nine, I opened a snap circuit set for my grandmother. Although I had always loved math and science. I didn’t realize my passion for engineering until I spent the rest of winter break creating different circuits to power various lights, alarms, and sensors. Even after I outgrew the toy, I kept the set in my bedroom at home and knew I wanted to study engineering.

Later in high school biology class, I learned that engineering didn’t only apply to circuits, but also to medical devices that could improve people’s quality of life. Biomedical engineering allows me to pursue my academic passions and help people at the same time. Just as biology and engineering interact in biomedical engineering, I am fascinated by interdisciplinary research in my chosen career path.

Duke offers unmatched resources, such as DuHatch and The Foundry, that will enrich my engineering education and help me practice creative problem-solving skills. The emphasis on entrepreneurship within these resources will also help me to make a helpful product. Duke’s Bass Connections program also interests me; I firmly believe that the most creative and necessary problem solving comes by bringing people together from different backgrounds.

Through this program, I can use my engineering education to solve complicated societal problems, such as creating sustainable surgical tools for low income countries. Along the way I can learn alongside experts in the field. Duke’s openness and collaborative culture span across its academic disciplines, making Duke the best place for me to grow both as an engineer and as a social advocate.”

“One Christmas morning when I was nine, I opened a snap circuit set for my grandmother. Although I had always loved math and science. I didn’t realize my passion for engineering until I spent the rest of winter break creating different circuits to power various lights, alarms, and sensors. Even after I outgrew the toy, I kept the set in my bedroom at home and knew I wanted to study engineering.”

This first paragraph does something excellent, which is it starts with an anecdote. In the introductory anecdote, the author mentions specific things like alarms, lights, and sensors, so the reader can really visualize what’s happening.

Another strength of this excerpt is that the anecdote moves through time very quickly. It starts with Christmas morning, progresses to the rest of winter break, and then finally ends by discussing after the author outgrew the toy. That temporal growth is good because it gets a reader in and out of the anecdote quickly while feeling nostalgic. It makes the reader feel connected to the writer.

One weakness of this paragraph, however, is that the last line is a little too much; it hits you over the head with “I want to study engineering.” Admissions officers know that one experience from when you were nine years old may be too much to ascribe your passion for engineering to, so this doesn’t feel believable. Instead, this instance can be framed as a spark that ignited your passion for engineering or made you interested in learning more about engineering.

“Later in high school biology class, I learned that engineering didn’t only apply to circuits, but also to medical devices that could improve people’s quality of life. Biomedical engineering allows me to pursue my academic passions and help people at the same time. Just as biology and engineering interact in biomedical engineering, I am fascinated by interdisciplinary research in my chosen career path.”

This paragraph does a really good job of transitioning from the anecdote to the writer’s specific and current interest in biomedical engineering. However, there are a few drawbacks from this excerpt.

One weakness from this paragraph is that helping people is a trope that is really overused when talking about an interest in health and healthcare. You can help people in a variety of careers, so it is a bit naive to say that the only way you can help others is by pursuing a particular path. Instead, you want to make the essay sound more genuine by displaying the heart of your passion. What particular types of medical devices and interdisciplinary research is the student interested in? Which intersection of fields is the most interesting to them and why? Giving more details or even specific adjectives here would help the essay sound more informed and robust.

Another aspect of this essay that could be improved is that the author mentions their ideal career path but doesn’t elaborate on this beyond biomedical engineering as a field of study. There are many different paths you can take after studying biomedical engineering. You could go into the research and development of products, or medicine, or the research behind patient-facing studies. What about your ideal career makes you excited to pursue that given field or major?

”Duke offers unmatched resources, such as DuHatch and The Foundry, that will enrich my engineering education and help me practice creative problem-solving skills. The emphasis on entrepreneurship within these resources will also help me to make a helpful product. Duke’s Bass Connections program also interests me; I firmly believe that the most creative and necessary problem solving comes by bringing people together from different backgrounds.”

This paragraph takes on the question in the second part of the prompt by explaining explicitly why they want to study biomedical engineering at Duke. One thing this essay does very well is that it brings up Duke specific resources and opportunities – DuHatch, The Foundry, and Bass Connections. They also mention the spirit of entrepreneurship that is ingrained in the teaching at Duke and how this is important to the design process in engineering. By connecting to Duke’s academic philosophy, this shows the admissions officers that this student not only did their research but also shares values with the school itself.

One of this paragraph’s weaknesses, however, is that the student mentions that “Duke offers unmatched resources, which is quite cliche and generic. Duke already knows that they are well regarded in the engineering field, so this is a waste of words in this essay.

Another aspect of the essay that could be improved here is the vague and undeveloped idea of creative problem solving skills that would be honed by attending Duke. The author uses the phrase “problem solving” a couple of times and wastes some space on two transition sentences. Overusing this phrase detracts from the power of the language and weakens the general cadence of your essay.

“Through this program, I can use my engineering education to solve complicated societal problems, such as creating sustainable surgical tools for low income countries. Along the way I can learn alongside experts in the field. Duke’s openness and collaborative culture span across its academic disciplines, making Duke the best place for me to grow both as an engineer and as a social advocate.”

This final paragraph is a strong conclusion because it is succinct and ties together all of the previous paragraphs. It makes the essay feel complete by the time the reader reaches the end. Combining engineering and social advocacy is also a great thought. It is in line with the rest of the essay and shows that this student is person-minded and not machine-minded. It demonstrates a dedication to community, which is something that Duke values as well.

However, if the author had incorporated these ideas of social advocacy earlier in the essay, this would have emphasized their fit with Duke and made the essay even stronger. Additionally, the specific idea of creating sustainable surgical tools for low income countries is very unique and would have been more powerful if it had been mentioned earlier; here it simply feels like an afterthought.

The conclusion also includes awkward wording in some of the phrases like “Duke’s openness and collaborative culture,” which could be reworded as “Duke’s open and collaborative culture.” By reducing some of the awkward phrasing, the author would have had some more space to play around with their specific interests in biomedical engineering and Duke’s programs.

Is Your “Why Major” Essay Strong Enough?

Essays account for around 25% of your admissions decision, as they’re your chance to humanize your application and set yourself apart from other applicants with strong profiles.

The “Why Major” essay is especially important, as it allows you to reflect on your unique interests and fit with the school. Your supplement needs to demonstrate your interest in the major and paint a picture of how you’ll contribute to their program.

To understand if your essay is strong enough, we recommend using our Peer Essay Review tool , where you can get a free review of your essay from another student. You can also improve your own writing skills by reviewing other students’ essays. This tool will make it easier to understand your essay’s strengths and weaknesses, and help you make your writing even more compelling.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

- Applying to Uni

- Apprenticeships

- Health & Relationships

- Money & Finance

Personal Statements

- Postgraduate

- U.S Universities

University Interviews

- Vocational Qualifications

- Accommodation

- Budgeting, Money & Finance

- Health & Relationships

- Jobs & Careers

- Socialising

Studying Abroad

- Studying & Revision

- Technology

- University & College Admissions

Guide to GCSE Results Day

Finding a job after school or college

Retaking GCSEs

In this section

Choosing GCSE Subjects

Post-GCSE Options

GCSE Work Experience

GCSE Revision Tips

Why take an Apprenticeship?

Applying for an Apprenticeship

Apprenticeships Interviews

Apprenticeship Wage

Engineering Apprenticeships

What is an Apprenticeship?

Choosing an Apprenticeship

Real Life Apprentices

Degree Apprenticeships

Higher Apprenticeships

A Level Results Day 2024

AS Levels 2024

Clearing Guide 2024

Applying to University

SQA Results Day Guide 2024

BTEC Results Day Guide

Vocational Qualifications Guide

Sixth Form or College

International Baccalaureate

Post 18 options

Finding a Job

Should I take a Gap Year?

Travel Planning

Volunteering

Gap Year Guide

Gap Year Blogs

Applying to Oxbridge

Applying to US Universities

Choosing a Degree

Choosing a University or College

Personal Statement Editing and Review Service

Guide to Freshers' Week

Student Guides

Student Cooking

Student Blogs

Top Rated Personal Statements

Personal Statement Examples

Writing Your Personal Statement

Postgraduate Personal Statements

International Student Personal Statements

Gap Year Personal Statements

Personal Statement Length Checker

Personal Statement Examples By University

Personal Statement Changes 2025

Personal Statement Template

Job Interviews

Types of Postgraduate Course

Writing a Postgraduate Personal Statement

Postgraduate Funding

Postgraduate Study

Internships

Choosing A College

Ivy League Universities

Common App Essay Examples

Universal College Application Guide

How To Write A College Admissions Essay

College Rankings

Admissions Tests

Fees & Funding

Scholarships

Budgeting For College

Online Degree

Platinum Express Editing and Review Service

Gold Editing and Review Service

Silver Express Editing and Review Service

UCAS Personal Statement Editing and Review Service

Oxbridge Personal Statement Editing and Review Service

Postgraduate Personal Statement Editing and Review Service

You are here

Physics personal statement example 1.

One of the most appealing features of Physics is the way that complex physical phenomena can be explained by simple and elegant theories. I enjoy the logical aspect of the subject and I find it very satisfying when all the separate pieces of a problem fall together to create one simple theory. My interest and aptitude for maths adds an extra dimension to Studying science, particularly Physics. I relish the challenge of a complicated problem both in physics and mathematics. I am also a keen practical physicist, during a degree I would like to keep in touch with the practical side of the subject.

My interest in science extends outside the classroom. I keep up to date with new developments and ideas by reading around my school subjects in books and also in journals such as "New Scientist" and "Scientific American". I have read books by Richard Feynman, Richard Dawkins and lan Stewart, I also particularly enjoyed John Archibald Wheeler's "A Journey into Gravity and Spacetime". These books challenge me in a way that is very different from the way in which I am required to think at school.

Over the summer holidays of 2001 I arranged three weeks of work experience in the Department of Materials Science at the University of Oxford. During this time I worked with three different research groups studying the atomic structure of surfaces, use of the 3D atom probe, and the structure of magnetic storage surfaces. The work on magnetic surfaces was particularly exciting because it was a new development that could have a significant impact. I also wrote some documents for them, such as a guide to help students find Materials Science resources on the Internet. The whole experience was very useful because I had to apply what I had leamt at school to unfamiliar areas, thus using my brain in an entirely new way.

I am a keen sportsman both in and out of school, having represented my school, and the Oxford Devils' under-17 team, at basketball. For the past three years I have played cricket for the school team, being captain for two years I have been in the Oxfordshire cricket squad for my age group since the age of thirteen and have been a senior player at Bicester and North Oxford-Cricket Club since 1998. Playing team sports has taught me a lot about the importance of team work and I believe I can apply this in a working environment. Recently, I discovered an enthusiasm for scuba diving, and have achieved my open water diving license.

During my time at university I aim to get a first class education that will stand me in good stead for entering the world of work; I also want to continue my education in an environment in which I can thrive mentally. In return, the university will get a student who is hard working, always willing to learn and will put something back into the community.

Profile info

There is no profile associated with this personal statement, as the writer has requested to remain anonymous.

Related Personal Statements

Wed, 29/09/2004 - 00:00

a marvellous personal

Thu, 01/09/2005 - 00:00

a marvellous personal statement... oxford style... yeah!

Very clear, very good.

Sat, 17/09/2005 - 00:00

Very clear, very good. Thank you to whoever submitted this, it has greatly helped me to structure my statement. :)

Thu, 03/11/2005 - 00:00

Well written, well done!

Thu, 22/12/2005 - 00:00

Thank you!!! :P

Thu, 16/03/2006 - 00:00

Sun, 09/07/2006 - 00:00

to be honest, your statement OWNS

Very good indeed. I was

Wed, 23/08/2006 - 00:00

Very good indeed. I was particularly interested by the last sentence - the remark regarding what the University would obtain by having you as a student. Nicely structured, and I love the way that the statement constantly relates back to the point of it. First paragraph is abit 'blah' for my liking though. Thanks.

Excellent personal statement.

Sun, 10/09/2006 - 00:00

Your enjoyment of the subject really comes through.

very well written but the

Tue, 19/09/2006 - 00:00

very well written but the final sentance made me wanna hurl

it always seems to pay to

Thu, 21/09/2006 - 00:00

it always seems to pay to mention anything to do with oxford or cambridge

Thu, 19/04/2007 - 12:00

Lolz at "Very hard working... and will put something back into the community!" I bet you've no interest in advancing the community with your life. Lolz people are just halirious..

I find the wording of the

Sat, 29/09/2007 - 21:24

I find the wording of the first paragraph is a bit over the top, and the 'putting some something back into the community' a bit pretentious. Apart from that it seems very good.

Thanks to whoever wrote this.

Sat, 03/11/2007 - 14:26

Thanks to whoever wrote this. It helped alot showing me how I should structure mine. ^_^

yeah i agree, it has helped

Tue, 06/11/2007 - 16:37

yeah i agree, it has helped me a whole lot!!!!!=^.^=

before i read this i had no idea what to write but this has given me plenty of ideas

thanks again =^.^=

This helped me a great deal

Sun, 13/01/2008 - 17:37

This helped me a great deal in what to write about.

Tue, 22/04/2008 - 22:06

Good Personal Statement given

Mon, 11/08/2008 - 09:21

Good Personal Statement given me a good idea of what i should write :), anyone else notice the spelling mistake ????

professional approach

Fri, 15/08/2008 - 11:36

Thu, 28/08/2008 - 00:34

It seems to me that you are applying to either Oxbridge, or Imperial.

That's the kind of class this statement is in. I envy you.

Somehow, this helped with mine, so thank you.

Probably outstanding

Sun, 07/09/2008 - 22:32

Yeah, like someone else said

Sun, 21/09/2008 - 14:28

Yeah, like someone else said the first para was a bit OTT. The language disrupted the flow a little. Awesome statement though ;) *steals ideas*

WOW! This owned me out the

Sun, 12/10/2008 - 20:22

WOW! This owned me out the water. Damn!

Thu, 23/10/2008 - 16:53

i basically used this to complete my entire statement. I am just that lazy.

You cant even call this a

Thu, 13/11/2008 - 10:27

You cant even call this a personal statement

Bloody hell

Tue, 18/11/2008 - 07:47

this is friggin gd u really helped me with mine thnx

hey do the univeristies keep

Mon, 24/11/2008 - 18:42

hey do the univeristies keep records of personal statements? XD

yeeeeeeeehhhhh, Oxford,

Thu, 27/08/2009 - 18:18

yeeeeeeeehhhhh, Oxford, woooooeeeee u can never have too much Oxford...sarcasm is such a useful tool.

Thu, 27/08/2009 - 18:26

Fri, 05/11/2010 - 10:22

Dude your Personal Statment would win in a fight against a massive horny bison!!!!!!

ARE YOU KIDDING ME? This

Mon, 15/11/2010 - 13:23

ARE YOU KIDDING ME? This personal statement sucks!

Fri, 07/10/2011 - 09:14

funny how an r and an n look like an m with this font

very good statement very

Sat, 10/11/2012 - 14:35

very good statement very useful very brave of you posting it online to be checked good job and don't listen to guys who hate it

Thu, 25/07/2013 - 17:40

Major thanks for the article post.Much thanks again. Really Cool.

Add new comment

1.1 Physics: An Introduction

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the difference between a principle and a law.

- Explain the difference between a model and a theory.

The physical universe is enormously complex in its detail. Every day, each of us observes a great variety of objects and phenomena. Over the centuries, the curiosity of the human race has led us collectively to explore and catalog a tremendous wealth of information. From the flight of birds to the colors of flowers, from lightning to gravity, from quarks to clusters of galaxies, from the flow of time to the mystery of the creation of the universe, we have asked questions and assembled huge arrays of facts. In the face of all these details, we have discovered that a surprisingly small and unified set of physical laws can explain what we observe. As humans, we make generalizations and seek order. We have found that nature is remarkably cooperative—it exhibits the underlying order and simplicity we so value.

It is the underlying order of nature that makes science in general, and physics in particular, so enjoyable to study. For example, what do a bag of chips and a car battery have in common? Both contain energy that can be converted to other forms. The law of conservation of energy (which says that energy can change form but is never lost) ties together such topics as food calories, batteries, heat, light, and watch springs. Understanding this law makes it easier to learn about the various forms energy takes and how they relate to one another. Apparently unrelated topics are connected through broadly applicable physical laws, permitting an understanding beyond just the memorization of lists of facts.

The unifying aspect of physical laws and the basic simplicity of nature form the underlying themes of this text. In learning to apply these laws, you will, of course, study the most important topics in physics. More importantly, you will gain analytical abilities that will enable you to apply these laws far beyond the scope of what can be included in a single book. These analytical skills will help you to excel academically, and they will also help you to think critically in any professional career you choose to pursue. This module discusses the realm of physics (to define what physics is), some applications of physics (to illustrate its relevance to other disciplines), and more precisely what constitutes a physical law (to illuminate the importance of experimentation to theory).

Science and the Realm of Physics

Science consists of the theories and laws that are the general truths of nature as well as the body of knowledge they encompass. Scientists are continually trying to expand this body of knowledge and to perfect the expression of the laws that describe it. Physics is concerned with describing the interactions of energy, matter, space, and time, and it is especially interested in what fundamental mechanisms underlie every phenomenon. The concern for describing the basic phenomena in nature essentially defines the realm of physics .

Physics aims to describe the function of everything around us, from the movement of tiny charged particles to the motion of people, cars, and spaceships. In fact, almost everything around you can be described quite accurately by the laws of physics. Consider a smart phone ( Figure 1.3 ). Physics describes how electricity interacts with the various circuits inside the device. This knowledge helps engineers select the appropriate materials and circuit layout when building the smart phone. Next, consider a GPS system. Physics describes the relationship between the speed of an object, the distance over which it travels, and the time it takes to travel that distance. GPS relies on precise calculations that account for variations in the Earth's landscapes, the exact distance between orbiting satellites, and even the effect of a complex occurrence of time dilation. Most of these calculations are founded on algorithms developed by Gladys West, a mathematician and computer scientist who programmed the first computers capable of highly accurate remote sensing and positioning. When you use a GPS device, it utilizes these algorithms to recognize where you are and how your position relates to other objects on Earth.

Applications of Physics

You need not be a scientist to use physics. On the contrary, knowledge of physics is useful in everyday situations as well as in nonscientific professions. It can help you understand how microwave ovens work, why metals should not be put into them, and why they might affect pacemakers. (See Figure 1.4 and Figure 1.5 .) Physics allows you to understand the hazards of radiation and rationally evaluate these hazards more easily. Physics also explains the reason why a black car radiator helps remove heat in a car engine, and it explains why a white roof helps keep the inside of a house cool. Similarly, the operation of a car’s ignition system as well as the transmission of electrical signals through our body’s nervous system are much easier to understand when you think about them in terms of basic physics.

Physics is the foundation of many important disciplines and contributes directly to others. Chemistry, for example—since it deals with the interactions of atoms and molecules—is rooted in atomic and molecular physics. Most branches of engineering are applied physics. In architecture, physics is at the heart of structural stability, and is involved in the acoustics, heating, lighting, and cooling of buildings. Parts of geology rely heavily on physics, such as radioactive dating of rocks, earthquake analysis, and heat transfer in the Earth. Some disciplines, such as biophysics and geophysics, are hybrids of physics and other disciplines.

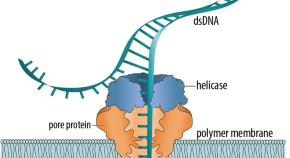

Physics has many applications in the biological sciences. On the microscopic level, it helps describe the properties of cell walls and cell membranes ( Figure 1.6 and Figure 1.7 ). On the macroscopic level, it can explain the heat, work, and power associated with the human body. Physics is involved in medical diagnostics, such as x-rays, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasonic blood flow measurements. Medical therapy sometimes directly involves physics; for example, cancer radiotherapy uses ionizing radiation. Physics can also explain sensory phenomena, such as how musical instruments make sound, how the eye detects color, and how lasers can transmit information.

It is not necessary to formally study all applications of physics. What is most useful is knowledge of the basic laws of physics and a skill in the analytical methods for applying them. The study of physics also can improve your problem-solving skills. Furthermore, physics has retained the most basic aspects of science, so it is used by all of the sciences, and the study of physics makes other sciences easier to understand.

Models, Theories, and Laws; The Role of Experimentation

The laws of nature are concise descriptions of the universe around us; they are human statements of the underlying laws or rules that all natural processes follow. Such laws are intrinsic to the universe; humans did not create them and so cannot change them. We can only discover and understand them. Their discovery is a very human endeavor, with all the elements of mystery, imagination, struggle, triumph, and disappointment inherent in any creative effort. (See Figure 1.8 and Figure 1.9 .) The cornerstone of discovering natural laws is observation; science must describe the universe as it is, not as we may imagine it to be.

We all are curious to some extent. We look around, make generalizations, and try to understand what we see—for example, we look up and wonder whether one type of cloud signals an oncoming storm. As we become serious about exploring nature, we become more organized and formal in collecting and analyzing data. We attempt greater precision, perform controlled experiments (if we can), and write down ideas about how the data may be organized and unified. We then formulate models, theories, and laws based on the data we have collected and analyzed to generalize and communicate the results of these experiments.

A model is a representation of something that is often too difficult (or impossible) to display directly. While a model is justified with experimental proof, it is only accurate under limited situations. An example is the planetary model of the atom in which electrons are pictured as orbiting the nucleus, analogous to the way planets orbit the Sun. (See Figure 1.10 .) We cannot observe electron orbits directly, but the mental image helps explain the observations we can make, such as the emission of light from hot gases (atomic spectra). Physicists use models for a variety of purposes. For example, models can help physicists analyze a scenario and perform a calculation, or they can be used to represent a situation in the form of a computer simulation. A theory is an explanation for patterns in nature that is supported by scientific evidence and verified multiple times by various groups of researchers. Some theories include models to help visualize phenomena, whereas others do not. Newton’s theory of gravity, for example, does not require a model or mental image, because we can observe the objects directly with our own senses. The kinetic theory of gases, on the other hand, is a model in which a gas is viewed as being composed of atoms and molecules. Atoms and molecules are too small to be observed directly with our senses—thus, we picture them mentally to understand what our instruments tell us about the behavior of gases.

A law uses concise language to describe a generalized pattern in nature that is supported by scientific evidence and repeated experiments. Often, a law can be expressed in the form of a single mathematical equation. Laws and theories are similar in that they are both scientific statements that result from a tested hypothesis and are supported by scientific evidence. However, the designation law is reserved for a concise and very general statement that describes phenomena in nature, such as the law that energy is conserved during any process, or Newton’s second law of motion, which relates force, mass, and acceleration by the simple equation F = m a F = m a . A theory, in contrast, is a less concise statement of observed phenomena. For example, the Theory of Evolution and the Theory of Relativity cannot be expressed concisely enough to be considered a law. The biggest difference between a law and a theory is that a theory is much more complex and dynamic. A law describes a single action, whereas a theory explains an entire group of related phenomena. And, whereas a law is a postulate that forms the foundation of the scientific method, a theory is the end result of that process.

Less broadly applicable statements are usually called principles (such as Pascal’s principle, which is applicable only in fluids), but the distinction between laws and principles often is not carefully made.

Models, Theories, and Laws

Models, theories, and laws are used to help scientists analyze the data they have already collected. However, often after a model, theory, or law has been developed, it points scientists toward new discoveries they would not otherwise have made.

The models, theories, and laws we devise sometimes imply the existence of objects or phenomena as yet unobserved. These predictions are remarkable triumphs and tributes to the power of science. It is the underlying order in the universe that enables scientists to make such spectacular predictions. However, if experiment does not verify our predictions, then the theory or law is wrong, no matter how elegant or convenient it is. Laws can never be known with absolute certainty because it is impossible to perform every imaginable experiment in order to confirm a law in every possible scenario. Physicists operate under the assumption that all scientific laws and theories are valid until a counterexample is observed. If a good-quality, verifiable experiment contradicts a well-established law, then the law must be modified or overthrown completely.

The study of science in general and physics in particular is an adventure much like the exploration of uncharted ocean. Discoveries are made; models, theories, and laws are formulated; and the beauty of the physical universe is made more sublime for the insights gained.

The Scientific Method

Ibn al-Haytham (sometimes referred to as Alhazen), a 10th-11th century scientist working in Cairo, significantly advanced the understanding of optics and vision. But his contributions go much further. In demonstrating that previous approaches were incorrect, he emphasized that scientists must be ready to reject existing knowledge and become "the enemy" of everything they read; he expressed that scientists must trust only objective evidence. Al-Haytham emphasized repeated experimentation and validation, and acknowledged that senses and predisposition could lead to poor conclusions. His work was a precursor to the scientific method that we use today.

As scientists inquire and gather information about the world, they follow a process called the scientific method . This process typically begins with an observation and question that the scientist will research. Next, the scientist typically performs some research about the topic and then devises a hypothesis. Then, the scientist will test the hypothesis by performing an experiment. Finally, the scientist analyzes the results of the experiment and draws a conclusion. Note that the scientific method can be applied to many situations that are not limited to science, and this method can be modified to suit the situation.

Consider an example. Let us say that you try to turn on your car, but it will not start. You undoubtedly wonder: Why will the car not start? You can follow a scientific method to answer this question. First off, you may perform some research to determine a variety of reasons why the car will not start. Next, you will state a hypothesis. For example, you may believe that the car is not starting because it has no engine oil. To test this, you open the hood of the car and examine the oil level. You observe that the oil is at an acceptable level, and you thus conclude that the oil level is not contributing to your car issue. To troubleshoot the issue further, you may devise a new hypothesis to test and then repeat the process again.

The Evolution of Natural Philosophy into Modern Physics

Physics was not always a separate and distinct discipline. It remains connected to other sciences to this day. The word physics comes from Greek, meaning nature. The study of nature came to be called “natural philosophy.” From ancient times through the Renaissance, natural philosophy encompassed many fields, including astronomy, biology, chemistry, physics, mathematics, and medicine. Over the last few centuries, the growth of knowledge has resulted in ever-increasing specialization and branching of natural philosophy into separate fields, with physics retaining the most basic facets. (See Figure 1.11 , Figure 1.12 , and Figure 1.13 .) Physics as it developed from the Renaissance to the end of the 19th century is called classical physics . It was transformed into modern physics by revolutionary discoveries made starting at the beginning of the 20th century.

Classical physics is not an exact description of the universe, but it is an excellent approximation under the following conditions: Matter must be moving at speeds less than about 1% of the speed of light, the objects dealt with must be large enough to be seen with a microscope, and only weak gravitational fields, such as the field generated by the Earth, can be involved. Because humans live under such circumstances, classical physics seems intuitively reasonable, while many aspects of modern physics seem bizarre. This is why models are so useful in modern physics—they let us conceptualize phenomena we do not ordinarily experience. We can relate to models in human terms and visualize what happens when objects move at high speeds or imagine what objects too small to observe with our senses might be like. For example, we can understand an atom’s properties because we can picture it in our minds, although we have never seen an atom with our eyes. New tools, of course, allow us to better picture phenomena we cannot see. In fact, new instrumentation has allowed us in recent years to actually “picture” the atom.

Limits on the Laws of Classical Physics

For the laws of classical physics to apply, the following criteria must be met: Matter must be moving at speeds less than about 1% of the speed of light, the objects dealt with must be large enough to be seen with a microscope, and only weak gravitational fields (such as the field generated by the Earth) can be involved.

Some of the most spectacular advances in science have been made in modern physics. Many of the laws of classical physics have been modified or rejected, and revolutionary changes in technology, society, and our view of the universe have resulted. Like science fiction, modern physics is filled with fascinating objects beyond our normal experiences, but it has the advantage over science fiction of being very real. Why, then, is the majority of this text devoted to topics of classical physics? There are two main reasons: Classical physics gives an extremely accurate description of the universe under a wide range of everyday circumstances, and knowledge of classical physics is necessary to understand modern physics.

Modern physics itself consists of the two revolutionary theories, relativity and quantum mechanics. These theories deal with the very fast and the very small, respectively. Relativity must be used whenever an object is traveling at greater than about 1% of the speed of light or experiences a strong gravitational field such as that near the Sun. Quantum mechanics must be used for objects smaller than can be seen with a microscope. The combination of these two theories is relativistic quantum mechanics, and it describes the behavior of small objects traveling at high speeds or experiencing a strong gravitational field. Relativistic quantum mechanics is the best universally applicable theory we have. Because of its mathematical complexity, it is used only when necessary, and the other theories are used whenever they will produce sufficiently accurate results. We will find, however, that we can do a great deal of modern physics with the algebra and trigonometry used in this text.

Check Your Understanding

A friend tells you they have learned about a new law of nature. What can you know about the information even before your friend describes the law? How would the information be different if your friend told you they had learned about a scientific theory rather than a law?

Without knowing the details of the law, you can still infer that the information your friend has learned conforms to the requirements of all laws of nature: it will be a concise description of the universe around us; a statement of the underlying rules that all natural processes follow. If the information had been a theory, you would be able to infer that the information will be a large-scale, broadly applicable generalization.

PhET Explorations

Equation grapher.

Learn about graphing polynomials. The shape of the curve changes as the constants are adjusted. View the curves for the individual terms (e.g. y = bx y = bx ) to see how they add to generate the polynomial curve.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/college-physics-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-science-and-the-realm-of-physics-physical-quantities-and-units

- Authors: Paul Peter Urone, Roger Hinrichs

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: College Physics 2e

- Publication date: Jul 13, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/college-physics-2e/pages/1-introduction-to-science-and-the-realm-of-physics-physical-quantities-and-units

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/college-physics-2e/pages/1-1-physics-an-introduction

© Jan 19, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Let your curiosity lead the way:

Apply Today

- Arts & Sciences

- Graduate Studies in A&S

Your Personal Statement for Graduate School

Starting from scratch.

The personal statement is your opportunity to speak directly to the admissions committee about why they should accept you. This means you need to brag. Not be humble, not humblebrag, but brag. Tell everybody why you are great and why you’ll make a fantastic physicist (just, try not to come off as a jerk).

There are three main points you need to hit in your essay:

- Your experience in physics. Direct discussion of your background in physics and your qualifications for graduate studies should comprise the bulk of your essay. What research did you do, and did you discover anything? Did you take inspiring coursework or go to a cool seminar? What do you want to do in graduate school? There’s a ton to discuss.

- Your personal characteristics. What makes you stand out? You’ve probably done a lot in college that’s not physics research or coursework. You need to mention the most impressive or meaningful of these commitments and accomplishments, and you need to demonstrate how they will eventually make you a better physicist. Are you a leader? A fundraiser? A teacher? A competitive mathematician? A team player? An activist for social change? All of these not-physics experiences may translate over to skills that will help you as a physics professor or researcher someday, and you can point this out!

- Context for your accomplishments. Is there anything else about your personal history or college experience that an admissions committee needs to know? The application form itself may only have space for you to list raw scores and awards, but graduate schools evaluate applications holistically. Thus they ask for the essay so you have a chance to tell your story and bring forth any personal details (including obstacles you overcame) to help the committee understand how great you truly are. Your application readers want to help you, and they’re giving you the chance to show how hard you’ve worked and how far you’ve come. But it’s up to you to connect the dots.

This type of essay is a lot more serious and a lot less creative than a college essay, a law school essay, or an essay for admission to a humanities PhD program. You’re basically trying to list a lot of facts about yourself in as small a space as possible. This is the place to tell everyone why you’re great. Do not hold back on pertinent information.

The following is going to be a general guide about how to write a first draft of your main graduate school essay. By no means think this is the only way to do it — there are plenty of possibilities for essay-writing! However, see this as a good way to get started or brainstorm.

If you’re completely stuck, a good way to start writing your essay is to compose each of the five main components separately.

- Your research experience

- Your outside activities or work experience

- Personal circumstances

- A story about you that can serve as a hook

- Your future goals + why you chose to apply to each school

At the end, we’ll piece these five different disjoint pieces together into one coherent essay.

1. Your research experience (and scientific industry employment)

This is the most important part of your essay, so it’s the place that we’ll start. We’ll pretend we’re structuring each research experience as its own paragraph (you can go longer or shorter, depending on how much time you spent in each lab or how much progress you made). Let’s see how it might work:

- .Simple overview of research: what you worked on, the name of your primary supervisor (professor or boss), and the location (university + department or company + division). The first time you mention a professor, you call them by their first and last name: “I worked for Emmett ‘Doc’ Brown in Hill Valley.” All subsequent times, you address them by their title and last name: “Dr. Brown and I worked on time travel.”

- “My research group was trying to build a time machine. My specific project was to improve the flux capacitor needed to make the machine work. I was able to make the capacitor exceed the 1.21 gigawatts needed for it to work. In addition, I helped do minor mechanical repairs on the DeLorean in which we built it.”

- “When I came back, I decided to take two additional graduate-level courses on time travel, and I found a similar internship the following summer.”

Then you just jam it all together into a semi-coherent paragraph:

In 1985, I worked for Emmett ‘Doc’ Brown in Hill Valley. Dr. Brown’s research group was trying to build a time machine. My specific project was to improve the flux capacitor needed to make the machine work. I was able to make the capacitor exceed the 1.21 gigawatts needed for it to work. In addition, I helped do minor mechanical repairs on the DeLorean in which we built it. When I came back, I decided to take two additional graduate-level courses on time travel, and I found a similar internship the following summer .

You’re not a character from Back to the Future , and it’s not beautiful prose, but you have to start somewhere. It’s more important to get all the facts you need down on the page before you work too hard on editing. Save that for after you have a well-structured and mostly-written essay.

2. (A) Your primary extracurricular activities or (B) your primary life experiences

(A) Tell the committee about any other major honors or experiences you’ve had in physics. Also write a paragraph or two about your interests outside of physics class and science research. Use this space to highlight the really impressive features of your activities:

- a second major or minor

- leadership positions in clubs, student representative to department/university committees, elected position in student government

- science clubs: Society of Physics Students, Math Club, engineering organizations, societies for students underrepresented in the sciences, etc.

- teaching activities: TA positions, tutoring, volunteer teaching commitments in any field of study, coaching a team, etc.

- other regular volunteering activities

- science advocacy and activism: political issues (government funding, global warming, nuclear policy, etc), improving diversity and inclusion in the sciences, science outreach on campus or in the local community

- a significant time commitment: varsity sports, heavy school-year employment, etc.

- other relevant skills: writing/publishing experience, public speaking, proficiency in other languages

- major fellowships, scholarships, honors, prizes, or awards you’ve won and if needed, an explanation of their significance/meaning

- attendance of physics conferences, symposia, summer schools, etc. that you haven’t already been able to mention in conjunction with the description of your research

If you have done many extracurricular activities, focus your 1-2 paragraphs on leadership positions, teaching, and service, particularly in the sciences.

(B) If you came to college a few years after you left high school, or if you are coming to graduate school a few years after you left college, then you need to write a few paragraphs discussing those life experiences. What did you do during that time? What experiences led you to choose physics graduate school as your next step? If you applied earlier but your application was rejected, how have you become more qualified since the last time you applied? You can feel free to ignore some of the advice we give later about how much of the essay you should focus on discussing physics experiences — structure the essay however you need to, to get the pertinent information across. Also, use Google extensively to find advice from other people who were in a situation similar to yours.

3. Personal circumstances

Now, look back at the various disjoint pieces of your essay that you need to fit together. What else might be relevant about you that you haven’t been able to mention yet?

Are there any major shortcomings in your application package? You need to address these, but do so INDIRECTLY. If you point your own flaws out to the committee directly, you are setting yourself up for failure. However, it is possible to leave pointed explanations for them in plain sight in your essay. For example, if you have a GPA that might seem low by normal graduate school standards, you could explain the significant amount of time you devoted to other major activities or a job, or describe any obstacles you have had to overcome (with the implication that you did so while still maintaining a GPA and completing your degree).

Even if your raw scores are perfect and your research excellent, you need to make your application stand out by letting the reader know who you are as a person. More specifically, you need to give some indication of how you will contribute to the diversity in background, experience, perspective, talents, and interests of students in the program.

- To quote a CommonApp essay prompt, “Some students have a background, identity, interest, or talent that is so meaningful they believe their application would be incomplete without it. If this sounds like you, then please share your story.”

- What makes you you ? What makes you interesting/fun/cool? What makes you stand out that won’t already be visible from your transcripts, recommendation letters, and application forms? How might you contribute to the diversity in background, experience, perspective, talents, and interests of students in a graduate program?

- How did you end up in physics? Why do you want to pursue physics? Is there some event, course, experience, or activity that was particularly meaningful for your life or that guided you into this path?

- Was there an extenuating circumstance that affected your performance in college? Think carefully about how and where you will discuss it. For example, you could frame it in a positive light so that you come off as resilient. An example might be “Despite [this factor], I was still able to [accomplish that].” You can also ask a trusted professor to mention it in their reference letter.

4. The hook

The final major piece of writing we’re going to do is a hook to open your essay. Do you have some anecdote, story, or achievement that will really grab the reader’s attention right away? They’re reading through nearly a thousand applications in hopes of narrowing down the pile to under a hundred, so what will make you be among those who stand out? Think about this as you assemble the rest of your essay.

5. Your future goals and why you’re interested in each graduate school

For every school you’re applying to, you need to write 1-2 paragraphs (~10% of the essay) about why you’re applying to that school.

Now this can be tricky. You need to gather some information via the Google about each individual school beforehand:

- What would you be interested in researching at that school? Are there particular professors who stand out?

- Does the school prefer if you have a fairly defined idea of the 2-3 people you’d want to work for ahead of time, or do they favor applicants who aren’t certain yet?

- Does the school evaluate all applications at the same time, or do they send your application to separate committees for the research subfield(s) you indicate on the application form?

- Why are you going to graduate school and/or what do you want to do afterwards? How will your five to seven year experience doing a PhD at a certain place prepare you for that path?

Even if you definitely know what you want to do or even if you’re completely sure you need to explore a few areas of physics, you need to write this section of your essay to cater towards each school. This involves a few hours of research on each school’s website, looking up the research fields in which the department focuses and learning about the specialization of each professor.

Here’s a good way of compiling your first draft of this section:

- I [am interested in/want to] work on [one or two research fields you might be interested in]. Specific professors whom I would want to work for are [three to four professors].

- My life experiences that led me to pick these choices are [something].

- I am especially excited about [university name]’s [resource/opportunity] in [something to do with physics].

6. Compiling your final essay

By now, you should have written (most of) the disjoint individual pieces of the puzzle. You might be under the expected word count, you might be over the expected word count, or you might be right on track. You can forget about all that for now — it’s more important to get something together, and we’ll fix all those details later.

Because you’re probably submitting about a dozen distinct essays, let’s ignore the “Future plans” piece of the essay and try to just get one main body of the essay put together with the other paragraphs. For each school, you’ll tack the “future plans” part of the essay either onto the end of the essay or in some spot you’ve chosen in the middle that helps everything flow. For now, ignore word count and just get words on the page. You can go back through and slice out sections of the main essay to meet smaller word counts for certain schools.

Look at the pieces of your life. How do they logically fit together? Is your story best told chronologically, with one research experience or activity falling logically after the other? Or is there something that makes you so unique and special that it belongs right at the very beginning of the essay? Sort the pieces so that they assemble in a good order.

Next, we need to check on the size of these pieces. At the very least, discussion of research activities/STEM work experience and your future goals in research should make up 75-80% of your essay. If you wrote many long, elaborate paragraphs about your time in your fraternity or on the women’s tennis team, now is the time to scale that back to only a sentence. Remember that the admissions committees truly only care about your potential to succeed in the future as a physicist. If you couldn’t give a clear explanation to your major advisor about how a tangential experience shows your potential to succeed in physics, you shouldn’t include it. (Note that “I got straight A’s in graduate courses while also involved in [major time commitment]” is an acceptable reason to include something and is beneficial to state.)

Did you talk about anything that happened in your childhood? (“I was interested in physics since in the womb”) Get rid of it. The only things that happened before college that are appropriate to mention are: (1) some significant aspect of your personal background that your application would be incomplete without, or (2) major college-level achievements: research leading to a publication, getting a medal in the International Physics/Math Olympiad, or dual-enrollment programs. However, mention items from (2) sparingly. You want to show that you’ve made major strides in the past four years; do not focus on your glory days in the past.

Do your paragraphs transition neatly from one to the next, or does your essay still feel off-kilter? A simple one sentence transition between paragraphs – either at the end of one or at the start of the next – can do wonders for your essay. Make sure it would make sense to someone who doesn’t know your background as well as you. Use the transition sentences to make your essay more interesting. Tell a story.

Congratulations. Now you have your first real draft of facts. Before you joyously run to your computer to submit your graduate application or run to your professor to give it a look over, go to one of your friends first.

The biggest danger with a graduate admissions essay is that you come off as really self-centered or boring. Nobody wants to read a thousand essays that merely list every single fact about a person’s life; they want to read a story. We helped you put together the bare bones of a graduate admissions essay, but did you tell a story? Did your personality shine through?

It’s a lot easier to go back and do an overhaul of an essay if you have something down on the piece of paper. Your friends might be able to help point out places that you can make your essay flow better or seem more interesting. They can tell you where to add more pizzazz in an otherwise boring research statement (“I worked on computational models of astrophysics during the month of July.” versus “I was so stoked when I found out I’d be modeling exploding stars that summer! That was the moment I knew I wanted to be a physicist.”). Take a day off, walk around, and then go back to your draft ready to show the world how excited you are to be a physicist and what an exciting physicist you are.

Our next section gives general tips for editing your personal statement, no matter whether you took our advice on how to start writing. Go through these steps very carefully to make sure you have an essay you’re proud of to send off to the admissions committee.

By the end of this process, you should have an impressive, interesting, factual draft of your qualifications that you’re ready to show a couple of trusted professors. You’ve worked super hard, and you’ve done a good job, we’re sure. However, professors are always critical, so don’t be upset if they tell you quite a few things to change. A young student reads an essay a lot differently than the older professors who are on the admissions committee, so it’s really important to get their perspective. Listen to what they say and truly consider making those changes. Edit once more, and repeat as many times as you need to.

At some point, you’ll finally be done with this long, difficult process and can proudly press “submit!”

General Tips for Editing

First things first: a step-by-step method for proofing your essay:.