Literary Devices

Literary devices, terms, and elements, poetic justice, definition of poetic justice.

Poetic justice occurs at the conclusion of a novel or play if and when good characters are rewarded and bad characters are punished. Poetic justice is thus somewhat similar to karma, and can be summed up by the phrases “He got what was coming to him,” or “She got what she deserved.” Note that poetic justice takes both positive and negative forms, depending on how a character has acted through the narrative . In more contemporary tales, poetic justice comes after an ironic twist stems from a character’s own actions and leads to the conclusion.

The definition of poetic justice was created by the English drama critic Thomas Rymer in 1678 in his book The Tragedies of the Last Age Considere’d . He urged authors to set moral examples and show how good overcomes evil. Indeed, Rymer was a critic at a time when it was thought that the role of literature was to provide moral education to the reading populace. Thus, poetic justice was necessary to encourage citizens to be upright in order to reap the rewards.

Common Examples of Poetic Justice

It is easy to think of examples of poetic justice in real life. For example, if a hard-working couple wins the lottery after years of being good citizens, this a positive example of poetic justice. If a corrupt businessman or politician is caught in a scandal and loses his position, this is also a poetic justice example.

There are also countless examples of poetic justice in movies and television shows. Here is a short list:

- The Shawshank Redemption : A man falsely accused and imprisoned for killing his wife escapes after two decades in prison, gets enough money to live in a beach town in Mexico, and has the police captain of the jail arrested for laundering money.

- Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade : Indiana Jones is in love with a Nazi sympathizer named Elsa, who is after the Holy Grail for greed alone. She takes it and causes an earthquake; instead of taking Indy’s hand and surviving, she reaches for the Grail and dies.

- Disney’s Aladdin : Aladdin pretends to be a prince to impress Princess Jasmine, but it is his good heart that ultimately wins her over, frees the genie, and overcomes the evil Jafar.

Significance of Poetic Justice in Literature

As stated above, poetic justice has sometimes been named as the reason that literature is important in a society. The genres of fable and parable often contain poetic justice, as a wise and good character is rewarded, and any bad characters are punished. The idea of these stories is to provide a moral foundation for readers.

Some examples of self fulfilling prophecy are also examples of poetic justice. If an evil character hears a prophecy and does cruel things in order to stop that prophecy from coming into being, then the villain’s ultimate defeat or death is attributed to the poetic justice of getting what he deserved.

Historically, it was also important in poetic justice that there was a sense that logic prevailed, and that characters do not suddenly change and warrant different treatment than what they deserve. For example, in Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol , it is not poetic justice that greedy Ebenezer Scrooge suddenly became good and therefore would warrant good treatment. Of course, not all authors are interested in poetic justice. More modern authors showed good characters receiving bad fortune and bad characters being rewarded. These authors would probably argue that their role in society was not to provide a moral education for readers, but instead to depict situations that are closer to reality. Indeed, believing too much in poetic justice could be harmful and give rise to questions like, “Why do bad things happen to good people?” Indeed, poetic justice is a literary device and not an accurate depiction of real life.

Examples of Poetic Justice in Literature

Below that point we found a painted people, who moved about with lagging steps, in circles, weeping, with features tired and defeated. And they were dressed in cloaks with cowls so low they fell before their eyes, of that same cut that’s used to make the clothes for Cluny’s monks Outside, these cloaks were gilded and they dazzled; but inside they were all of lead, so heavy that Frederick’s capes were straw compared to them. A tiring mantle for eternity!

( Inferno , Canto XXIII by Dante Alighieri)

Dante’s Inferno is basically one long treatise on poetic justice. Dante imagines himself as a character led through the different circles of Hell by the poet Virgil. In each circle they encounter different famous residents of Florence, Italy where Dante lived suffering punishments appropriate to the different sins they committed while alive. In the above example of poetic justice, Dante and Virgil see “the hypocrites” clothed in rich robes on the outside that are lead on the inside, to symbolize the deception of these men. Indeed, the concept of some people going to Heaven while others are sent to Hell has much to do with poetic justice.

HAMLET: There’s letters sealed, and my two schoolfellows, Whom I will trust as I will adders fanged, They bear the mandate. They must sweep my way And marshal me to knavery. Let it work, For ’tis the sport to have the engineer Hoist with his own petard. And ’t shall go hard, But I will delve one yard below their mines, And blow them at the moon. Oh, ’tis most sweet When in one line two crafts directly meet.

( Hamlet by William Shakespeare)

Many of William Shakespeare plays contain poetic justice examples. In this excerpt, Hamlet imagines that “the engineer” of Hamlet’s father’s death will be “hoist with his own petard.” Hamlet thinks of vengeance for his father as a type of poetic justice. However, in this scene he himself has just killed Polonius, and is dealt the poetic justice of his own death at the end of the play.

“I know things you don’t know, Tom Riddle . I know lots of important things that you don’t. Want to hear some, before you make another big mistake?” “Is it love again?” said Voldemort, his snake’s face jeering. “Dumbledore’s favorite solution, love, which he claimed conquered death, though love did not stop him falling from the tower and breaking like an old waxwork? Love, which did not prevent me from stamping out your Mudblood mother like a cockroach, Potter – and nobody seems to love you enough to run forward this time and take my curse. So what will stop you from dying now when I strike?” “Just one thing,” Harry replied quietly. “If it is not love that will save you this time, you must believe that you have magic that I do not, or else a weapon more powerful than mine?” “I believe both,” Harry said.

( Harry Potter and the Death Hallows by J.K. Rowling)

Many tales of good and evil contain endings with poetic justice, which is certainly the case with J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series. Harry Potter and his friends are exemplars of good, and are awarded accordingly with winning the final battle. Voldemort, the main evil character, believes that violence is stronger than love, and this is the vice and wrong thinking that leads to his death.

Test Your Knowledge of Poetic Justice

1. Which of the following statements is the best poetic justice definition? A. An ironic twist of fate. B. A climax in which bad things happen to good people. C. A conclusion where vice is punished and virtue rewarded.

2. The following passage is from Dante’s Inferno, and talks of the punishment that is dealt to magicians, astrologers, and diviners:

As I inclined my head still more, I saw that each, amazingly, appeared contorted between the chin and where the chest begins; they had their faces twisted towards their haunches and found it necessary to walk backward, because they could not see ahead of them.

Why is this an example of poetic justice? A. In Dante’s view, these people were charlatans and, for the sin of trying to tell the future, in the afterlife they are doomed to only be able to look backwards. B. The magicians, astrologers, and diviners in Dante’s day were the only truth-tellers, and Dante didn’t want them to be rewarded for their knowledge. C. The magicians, astrologers, and diviners had done nothing wrong, and it was cruel retribution on the part of those who were jealous of their gifts that they be sent to Hell.

3. Which of the following scenarios is an example of poetic justice? A. A corrupt businessman dies of natural causes before his pyramid scheme is revealed to be a sham. B. A nerd who was always bullied in childhood but never lashed out creates a computer program and makes millions. C. A figure skater who was trained tirelessly for her entire life breaks her ankle the day before her Olympic trial.

Poetic Justice

Poetic justice definition.

In literature, poetic justice is an ideal form of justice, in which the good characters are rewarded and the bad characters are punished, by an ironic twist of fate. It is a strong literary view that all forms of literature must convey moral lessons. Therefore, writers employ poetic justice to conform to moral principles.

For instance, if a character in a novel is malicious and without compassion in the novel, he is seen to have gone beyond improvement. Then, the principles of morality demand his character to experience a twist in his fate and be punished. Similarly, the characters who have suffered at his hand must be rewarded at the same time.

Examples of Poetic Justice in Literature

Let us analyze a few examples of poetic justice in Literature:

Example #1: King Lear (By William Shakespeare)

In Shakespeare’s King Lear we see the evil characters – Goneril, Regan, Oswald, and Edmund – thrive throughout the play . The good characters – Lear, Gloucester, Kent, Cordelia, and Edgar – suffer long and hard. We see the good characters turn to gods, but they are rarely answered. Lear, in Act 2, Scene 4 calls upon heaven in a most pitiful manner:

“… O heavens! If you do love old men, if your sweet sway Show obedience, if you yourselves are old, Make it your cause. Send down, and take my part!”

Lear loses his kingdom by the conspiracies of his daughters Goneril and Regan, who are supported by Edmund. At Dover, Edmund-led English troops defeat the Cordelia-led French troops, and Cordelia and Lear are imprisoned.

Cordelia is executed in the prison, and Lear dies of grief at his daughter’s death. Despite all the suffering that good undergoes, the evil is punished. Goneril poisons her sister Regan due to jealousy over Edmund. Later, she kills herself when her disloyalty is exposed to Albany. In a climactic scene, Edgar kills Edmund. In Act 5, Scene 3 he says:

“My name is Edgar, and thy father’s son. The gods are just , and of our pleasant vices Make instruments to plague us. The dark and vicious place where thee he got Cost him his eyes.”

Here, “The gods are just” because they punish the evil for their evil actions.

Example #2: Oliver Twist (By Charles Dickens)

We see the role of poetic justice in the cruel character Mr. Bumble, in Charles Dickens ’ Oliver Twist . Mr. Bumble was a beadle in the town where Oliver was born – in charge of the orphanage and other charitable institutions in the town. He is a sadist and enjoys torturing the poor orphans.

Bumble marries Mrs. Corney for money, and becomes master of her workhouse. Her,e his fate takes a twist as he loses his post as a beadle, and his new wife does not allow him to become a master of her workhouse. She beats him and humiliates him, as he himself had done to the poor orphans. Right at the end of the novel, we come to know that both Mr. and Mrs. Bumble end up being so poor that they live in the same workhouse that they once owned.

Example #3: Oedipus Rex (By Sophocles)

A classic example of poetic justice is found in the Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex , by Sophocles. In the play, Oedipus has committed the crime of defying gods by trying to escape his fate. Therefore, he left the kingdom he lived in, and went to the new kingdom of Thebes. He killed the king of the city after a quarrel, and married the queen.

Later, we learn that the prophecy turned out true, as the man he killed turned out to be his father, and the queen his own mother. The Greek believed their destinies were predetermined – shaped by the gods and goddesses. Whosoever tried to defy them, committed a sin and deserved punishment.

Function of Poetic Justice

Generally, the purpose of poetic justice in literature is to adhere by the universal code of morality, in that virtue triumphs vice. The idea of justice in literary texts manifests the moral principle that virtue deserves a reward, and vices earn punishment.

In addition, readers often identify with the good characters. They feel emotionally attached to them, and feel for them when they suffer at the hands of the wicked characters. Naturally, readers want the good characters to triumph and be rewarded; but they equally wish the bad characters to be penalized for their evilness. Thus, poetic justice offers contentment and resolution .

Related posts:

Post navigation.

English Studies

This website is dedicated to English Literature, Literary Criticism, Literary Theory, English Language and its teaching and learning.

Poetic Justice

The term “poetic justice” is a combination of two words: poetic and justice. The word “poetic” comes from the Latin word poeticus.

Etymology of Poetic Justice

Table of Contents

The term “poetic justice” is a combination of two words: poetic and justice. The word “poetic” comes from the Latin word poeticus . It has its roots in the Greek term poietikos , which means “pertaining to poetry or creation.” “Justice,” on the other hand, comes from the Latin word justitia, stemming from the Latin adjective justus , meaning “righteous” or “fair.” It refers to the moral principle of fairness, righteousness, and the proper administration of law.

Meanings of Poetic Justice

- Balance and Fairness: It signifies a just and equitable outcome that matches actions or qualities.

- Moral and Ethical Resolution: It reflects the alignment of actions and consequences, emphasizing morality.

- Ironic and Unexpected Twist: It incorporates irony and surprises in the outcome.

- Symbolic and Aesthetic Resonance: It adds symbolism and artistic impact to the resolution.

- Narrative Closure and Satisfaction: It provides closure and satisfaction to the audience.

- Reinforcement of Social Order: It reinforces societal norms and promotes moral principles.

- Artistic Expression and Creativity: Poetic justice showcases creative representation of justice.

Poetic Justice in Grammar

Grammatically, “poetic justice” is a noun phrase. It consists of the noun “justice” modified by the adjective “poetic.” The term does not function as a verb. However, the word “poeticize” is a verb that means “to make something poetic or give it a poetic quality.”

Definition of Poetic Justice

Poetic justice, as a literary device , means the attainment of a thematically fitting and morally satisfying outcome of a vice or a bad deed that aligns with the actions and qualities of characters in a narrative. It operates as a mechanism for rewarding virtue and punishing vice, enhancing the ethical dimensions of storytelling. Further use of literary devices or elements such as irony, symbolism, and unexpected turns, shows serving to reinforce cohesion, evoking emotional responses, and providing a sense of closure to the readers and audiences.

Types of Poetic Justice

There are several types of poetic justice in literature, including:

Literary Examples of Poetic Justice

These literary examples demonstrate how it plays a role in characters’ fates and the overall message of a work of literature.

How to Create Poetic Justice in a Fictional Work

To create it in a fictional work, here are some steps to consider:

- Establish the moral code

- Create flawed characters

- Establish consequences

- Use symbolism

- Ensure a satisfying resolution

In fact, creating poetic justice in a fictional work requires careful consideration of the characters’ actions, the consequences that result, and the overall message or moral of the story. By following these steps, you can create a compelling and impactful story that resonates with readers.

Benefits of Poetic Justice

Poetic justice can have several benefits in a work of literature, including:

- Reinforcing moral values

- Creating emotional impact

- Developing characters

- Engaging the reader

- Delivering a message

In short, poetic justice could be a powerful tool for creating impact and resonance in a work of literature, helping to reinforce moral values, engage the reader, and create emotional impact.

Poetic Justice and Literary Theory

Poetic justice can be analyzed and understood through various literary theories, including:

Suggested Readings

- Abrams, M. H. A Glossary of Literary Terms. Cengage Learning, 2014.

- Alter, Robert. Partial Magic: The Novel as a Self-Conscious Genre. University of California Press, 1975.

- Brooks, Peter. Reading for the Plot: Design and Intention in Narrative. Harvard University Press, 1992.

- Frye, Northrop. The Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays. Princeton University Press, 1957.

- Hogan, Patrick Colm. The Mind and Its Stories: Narrative Universals and Human Emotion. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Lentricchia, Frank. After the New Criticism. University of Chicago Press, 1980.

- Ricks, Christopher. The Force of Poetry. Oxford University Press, 1984.

- Wilt, Judith. Cinderella in America: A Book of Folk and Fairy Tales. Utah State University Press, 2007.

Related posts:

- Onomatopoeia: A Literary Device

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- National Poetry Month

- Materials for Teachers

- Literary Seminars

- American Poets Magazine

Main navigation

- Academy of American Poets

User account menu

Poetic Justice

Page submenu block.

- literary seminars

- materials for teachers

- poetry near you

Add to anthology

Still i rise.

You may write me down in history With your bitter, twisted lies, You may trod me in the very dirt But still, like dust, I’ll rise.

Does my sassiness upset you? Why are you beset with gloom? ’Cause I walk like I’ve got oil wells Pumping in my living room. Just like moons and like suns, With the certainty of tides, Just like hopes springing high, Still I’ll rise.

Did you want to see me broken? Bowed head and lowered eyes? Shoulders falling down like teardrops, Weakened by my soulful cries?

Does my haughtiness offend you? Don’t you take it awful hard ’Cause I laugh like I’ve got gold mines Diggin’ in my own backyard.

You may shoot me with your words, You may cut me with your eyes, You may kill me with your hatefulness, But still, like air, I’ll rise.

Does my sexiness upset you? Does it come as a surprise That I dance like I’ve got diamonds At the meeting of my thighs?

Out of the huts of history’s shame I rise Up from a past that’s rooted in pain I rise I’m a black ocean, leaping and wide, Welling and swelling I bear in the tide.

Leaving behind nights of terror and fear I rise Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear I rise Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave, I am the dream and the hope of the slave. I rise I rise I rise.

From And Still I Rise by Maya Angelou. Copyright © 1978 by Maya Angelou. Reprinted by permission of Random House, Inc.

Newsletter Sign Up

- Academy of American Poets Newsletter

- Academy of American Poets Educator Newsletter

- Teach This Poem

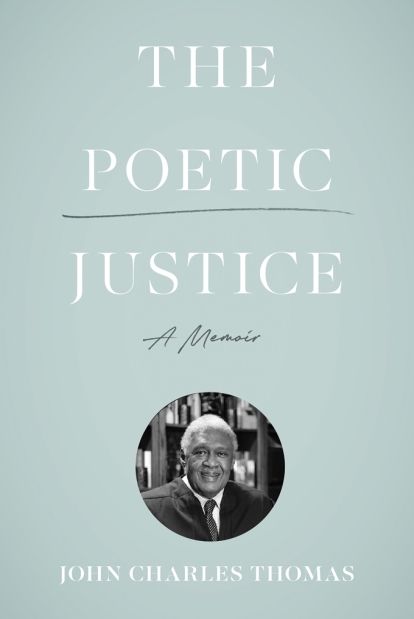

University of Virginia School of Law

The Poetic Justice

Photo by John Charles Thomas Jr.

Four-year-old John Charles Thomas stood on the porch of his grandfather’s home, watching him banter with several old friends who were leaning against the porch banister.

“Come here,” Thomas’ grandfather called to him. Thomas obediently came over. “Say that poem.”

“Yes, Granddaddy,” Thomas said.

“Hold your head up.”

“Yes, sir,” said Thomas.

“What’s the poem?” his grandfather asked.

“‘Thanatopsis,’ by William Cullen Bryant,” Thomas said. And he proceeded to recite from memory the entire 642-word poem his grandfather had taught him:

To him who in the love of Nature holds Communion with her visible forms, she speaks A various language; for his gayer hours She has a voice of gladness, and a smile And eloquence of beauty, and she glides Into his darker musings, with a mild And healing sympathy, that steals away Their sharpness, ere he is aware….

The men were beside themselves, amazed at Thomas’ excellent memory, urging him on, shouting, “Go, go, go, go!”

Thomas, who recalled the story at the Law School’s annual Community Martin Luther King Jr. Celebration in January, went on to become a graduate of UVA’s College of Arts & Sciences in 1972 and the Law School in 1975. He was also the first Black lawyer hired by a large law firm in Richmond. When he made partner there in 1982, he was the first Black lawyer in the history of the American South to make partner at an old-line Southern law firm.

Thomas, then a Virginia Supreme Court justice, gives a talk as a guest of the Student Legal Forum in the spring of 1983.

IN 1983, at the age of 32, he became Justice John Charles Thomas, the first Black justice — and also the youngest—in the history of the Supreme Court of Virginia.

The University of Virginia Press recently published Thomas’ new book, “The Poetic Justice: A Memoir,” a reflection on Thomas’ twin loves of poetry and the law. The book’s title alludes not only to the deep love of poetry instilled by his grandfather, but also to overcoming the maze of injustices Thomas faced — and succeeded in spite of — as he came of age in the 1960s and ’70s in Virginia’s deeply segregated landscape.

As a bright high school student with an eidetic memory, Thomas was chosen by teachers at his school to integrate the all-white high school in Norfolk.

“We need volunteers — raise your hands,” is how Thomas described the moment.

“Our teachers in the all-Black schools basically told us you have to change the world; you have no choice. … You’re going to have to show these people who we are,” he said. “And so, we felt that burden. I mean, we didn’t just pick up the burden. It was kind of laid on us.”

The burden was not a light one.

“The theory was, no Negro belongs at white schools in the ’60s. And so, if I failed a class, it would make the newspaper. You would wonder why, but the teachers were talking to the media. … We were under scrutiny the whole time.”

Once, when Thomas realized he’d forgotten an assignment for his Advanced English class, he had just 20 minutes to write a poem, short story or essay. Although he had been reciting poetry since he was 4, it never occurred to him that he could write a poem of his own.

“And so, in that 20 minutes — with my life on the line and it was going to be in the newspaper if I didn’t get it right — I write a poem for the first time ever,” Thomas said.

He titled it, “The Morning.”

The morning is a time for man to rise, review the things that formed his past, make all his disappointments and mistakes quite clear so they will be his last. The morning is a time for man to think of all the things to come, to plot, to plan, to try his best to be ahead when day is done. The morning is the time for man to dream of things not yet conceived, to gather his thoughts and ideas around the things that he alone believes. The morning is a time for man to rise and think and dream and see that all the world depends on men who with thoughts of hope the day begin.

When the teacher returned his work, “She takes my poem,” Thomas said, “She holds it by the corner, she walks to my desk, she throws it at me, and in front of the class she says ‘I reject this. I do not believe a colored child could write this.’”

Thomas was 17 years old. He kept writing poetry, but just for himself.

During a question-and-answer session at the MLK Celebration, Dean Risa Goluboff and Professor Kim Forde-Mazrui asked Thomas how he endured and succeeded through such injustices.

“FOR ME,” Thomas said, “it was not a question of any grand strategy. It was a question of baby steps and survival.”

At times, “survival” was literal. He recalled meeting his father for the first time — in a penitentiary, where he was serving time as a felon. An alcoholic, his father became violent when drunk. One day after his release he beat Thomas’ mother until Thomas had had enough.

“I’m 6 years old — he’s beating my Mama, and I think he’s going to kill her. … I get the biggest knife I can find. And I say, ‘If you hit my Mama again, I will kill you.’”

His father then froze, and “spent the rest of his life never knowing what I might do.”

Along the way, he found other ways to prove himself and change minds. One day he challenged the president of his high school’s chess club to a game and beat him. “And he was so astounded that he gave me his box of Drueke tournament chess men. … But he became a friend of sorts because he knew, well, that guy can play chess.”

Thomas also joined the student government and the Key Club. He and his friend invited the club to their church and soon the newspaper reported on the white club visiting the Black church.

“If you can see some change,” he said, “if you see a little crack in the door, if you see a little light coming in, I think in that setting, you can keep pushing. And I was able to see that enough to keep going.”

After Thomas visited UVA and was struck by the beauty on Grounds, he wanted to attend. A National Merit semifinalist, he won scholarships and attracted Ivy League brochures. But nothing from UVA.

“And because they didn’t ask me to come, I decided I was going to come here.”

While many of his friends went to historically Black colleges, Thomas studied at the University and learned to navigate two worlds.

“There was a UVA person, and there was a person at home. The sound of my voice might even be different” in the two settings, he said.

As one of just a handful of Black students at UVA Law when he attended, Thomas said he did not remember a time in any course where justice — as opposed to law — was discussed.

“Law and justice are not the same thing,” Thomas told the audience.

The law is important, Thomas said. “You’ve got to understand the statutes and you have to understand the principles.”

But King spoke to people about justice, Thomas said.

“This man was motivated by justice. He changed America because of a sense of justice. … Let us realize that ‘The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice,’” Thomas told the audience, quoting King.

“When I look right here at this audience,” Thomas said, “Black and white, men and women, I know that it didn’t always look this way, and it can bring me to tears.

“But it brings me to tears because of the suffering of people […] who said we’re not going to stand for this; we’re not going to have this kind of wrongdoing; we’re not going to have a world where the law says that all people are created equal and yet they don’t treat us that way.”

DESPITE THE STING he felt from his high school teacher’s actions, Thomas kept writing. In 2006, his life took another poetic turn when he was appointed to the Board of Visitors at the College of William & Mary. There, a music professor learned about Thomas’ talent for writing poetry and composed music for a number of his poems.

The result was good. So good, in fact, the professor thought they should arrange a concert at Carnegie Hall as a fundraiser for William & Mary.

“And darned if they don’t do it,” Thomas said. “And I’m the star poet!”

Thomas opened and closed the Carnegie Hall program with his high school poem, “The Morning.”

… The morning is a time for man to rise and think and dream and see that all the world depends on men who with thoughts of hope the day begin.

“At the end,” Thomas said, “I step to the edge of the stage, and I say, ‘Don’t crush somebody’s spirit by the hatred you have inside of you. Don’t diminish someone’s goal.’

“And I started crying.”

The audience at Carnegie Hall started crying, too. As did the UVA Law audience.

Poetic justice indeed.

Mary M. Wood Chief Communications Officer

The Critique That Inspired John Singleton to Make Poetic Justice

After Boyz n the Hood was challenged on its portrayal of African American women, the late director created a character meant to better reflect their myriad experiences.

No one elevated South Central Los Angeles to the point of universal conversation like the late John Singleton. Filmmakers such as Melvin Van Peebles and Charles Burnett had both set their stories on this terrain previously. But Singleton, with his films, forced the world to take note of an area ravaged by violence and neglect, yet abundant with cultural distinction and richness. The director’s narratives are cinematic bildungsromans, canvases for young black men and women to discover their identities, to shape and come to terms with their inner selves, to fall in and out of love, to fight and reconcile, to evolve. He was our first hip-hop filmmaker, expressing vernacular and urban culture in a way that had not been so uniquely championed until he arrived on the scene in 1991 right out of USC film school.

When considering Singleton’s brilliance and influence, the example used most frequently is his debut feature Boyz n the Hood —and rightfully so. In this semiautobiographical work, Singleton brought attention to the disparities of life in South Central for young black men, a theme captured by one of the film’s most famous lines: “Either they don’t know, don’t show, or don’t care about what’s going on in the hood.” Through Boyz ’s central characters, Singleton counters the negative portraits of black masculinity with a celebration of fatherhood and black consciousness.

As powerful as Boyz proved to be—earning Singleton Academy Award nominations for Best Director and Best Original Screenplay—the wunderkind would stray from this formula for his sophomore project. His 1993 follow-up, Poetic Justice, wasn’t the lightning rod that Boyz was, but it deserves equal consideration when discussing his canon. The film featured the young superstar Janet Jackson in her first starring movie role, playing a hairdresser plagued by grief after witnessing the retaliatory gang killing of her boyfriend. It presents a softer side of South Central and its inhabitants, a movie that the film critic Odie Henderson said “meandered like Éric Rohmer and swore like Richard Pryor.” Poetic Justice debuted after the Rodney King riots, when much of Los Angeles was in disarray and in need of rebuilding. With this in mind, Singleton shifted the narrative focus toward romance, family, and friendship.

Read: John Singleton changed how Hollywood sees black America

Justice was also Singleton’s way of responding to critiques that he had largely diminished the experiences of young black women, namely single mothers, in Boyz , with one-dimensional characterizations. The late media critic and director Jacquie Jones, writing in Cineaste in 1991, said that the women in Boyz were cast “to symbolize the oppressions facing black men, as either barriers or burdens … Here, the female characters have carefully calculated, though secondary, roles which affirm the central theme of their blame and ineptitude.” Jones goes on to say that “as long as the humanity of young black men rests on the dismissal of black women, we, as black people, are not making progress—cinematic or otherwise.”

In creating Justice, Jackson’s character, Singleton had a definite vision. During a 1993 interview with The Washington Post , he revealed that the idea for Justice germinated from his thoughts about the girlfriends left behind once their partners’ lives were claimed by gang violence. In his book, Poetic Justice: Filmmaking South Central Style , Singleton wrote that he asked himself, after dealing with the insecurities of black men in Boyz , “Why not do a movie about a young sister and how all the tribulations of the brothers affect her?” He attributed that inspiration to his observation that “some of the most complex, sexy, diverse, three-dimensional women I’ve ever seen in my life all came out of my neighborhood. They all had a certain mold of substance.” From this vantage point, Singleton fashioned a black woman rarely seen on-screen to sit at the focus of his screenplay.

Singleton was similarly precise in his rendering of Justice’s style—the right image was essential. The box braids she wears were the collaborative choice of the director, Jackson, and two female choreographers he had worked with while directing Michael Jackson’s “Remember the Time” music video. Singleton also drew inspiration from the works of Italian neorealist filmmakers—most notably Vittorio De Sica’s Two Women , which he used to recreate Sophia Loren’s natural makeup look for Justice.

In a recent Essence essay , the writer Melissa Kimble asserted that Justice’s iconic hairstyle was a character in and of itself, not only marking Justice’s emotional transformation, but also symbolizing the beauty of black women. My cousin Heather, who died at the young age of 34, was a hairdresser as well, and she put serious wear on her Poetic Justice videocassette while braiding, hot ironing, and perming hair in her kitchen. I honestly believe her pursuit of a cosmetology license might have had as much to do with the representation she saw in Justice’s character as it did with her own talent.

Read: Why John Singleton wanted the ‘z’ in ‘Boyz n the Hood’

I am not suggesting that Singleton successfully answered all of his critics. Michele Wallace, in a 1993 critique in Entertainment Weekly , questioned whether the film had a clear, relatable female perspective, expressing that she hoped the film would “stir further discussion in the black community.” Still, the sincerity and relevance of Justice speaks to Singleton’s ability to tap into a part of the culture in desperate need of visibility. Kimble wrote that for her, the character marks “the first time I’d prominently seen a Black woman onscreen, openly dealing with grief and depression after tragically losing a loved one to violence … Even in the complexity of his subject matter—violence, racism, and poverty—Singleton made space for the resilience of Black women.”

Singleton wasn’t an auteur, so to speak—his visual and screenwriting styles were not flashy or complex. In his view, what was more vital and necessary than style was substance: telling the long-compromised stories of the men and women of South Central Los Angeles through layered characters. “[I am not in it] to right the wrongs of American cinema,” he wrote in his book. “I love movies. Period. Classic structure. Classic characters … I direct to protect my vision … I am a storyteller consummate.”

Poetic Justice ’s focus on the trauma and recovery of young black women in urban environments defied traditional expectations of who can be at the center of cinematic narratives. That John Singleton had the tremendous foresight to incorporate these experiences into film is more valuable than any trick of the camera. As the movie critic A. O. Scott wrote in The New York Times earlier this week, comparing Singleton and the Moonlight director Barry Jenkins, “[They] are directors whose primary motivation is their unstinting love for the people they conjure into being.” This is the work that makes for an indelible and long-lasting legacy—one that John Singleton so deftly and richly crafted.

Movie Reviews

Tv/streaming, collections, great movies, chaz's journal, contributors, poetic justice.

Now streaming on:

"Poetic Justice" is described as the second of three films John Singleton plans to make about the South Central neighborhood in Los Angeles.

His first, " Boyz N the Hood ," showed a young black man growing up in an atmosphere of street violence, but encouraged by his father to stand aside from the gangs and shootings and place a higher worth on his life. At the end of the film, the hero's friend was shot dead.

Now comes a film told from the point of view of a young woman in the same neighborhood - Justice, played by Janet Jackson . At the beginning of the film she's on a date at a drive-in theater with her boyfriend. Words are exchanged at the refreshment stand, egos are wounded, and before long her boyfriend is shot dead. (One of the realities in both films is the desperation of a community where self-respect is so precarious that small insults can become capital offenses.) Justice emerges from mourning determined to go it alone. What's the use of committing her heart to a man who will simply get himself killed in another stupid incident? She works in a beauty shop, where one day a mailman ( Tupac Shakur ) comes in and starts making soft talk. She leads him on and then lets him down with a mean trick. But the tables are turned when her friend Simone ( Khandi Alexander ) invites her to go along on a trip to Oakland. Her boyfriend has a friend who works for the post office and will let them ride along in a mail truck. Of course, the friend is Shakur.

Unlike "Boyz," which was fairly strongly plotted, "Poetic Justice" unwinds like a road picture from the early 1970s, in which the characters are introduced and then set off on a trip that becomes a journey of discovery. By the end of the film, Justice will have learned to trust and love again, and Shakur will have learned how to listen to a woman. And all of the characters - who in one way or another lack families - will begin to get a feeling for the larger African-American family to which they belong.

The scene where that takes place is one of the best in the film.

The mail truck takes them down back roads until they stumble across the Johnson Family Picnic, a sprawling, populous affair where not all of the cousins even know each other. That makes an ideal opportunity for the four travelers to wander in and get a free meal. But along the way they're also embraced by one of the cousins, and hear some words of wisdom from another one (the poet, Maya Angelou ).

It is Angelou's poetry we hear on the sound track of the movie; Justice is a poet, and we are told it is hers. She has aspirations and sensitivities, and as played by Jackson she emerges as a sweet, smart woman who is growing up to be a good person.

Her romance with Shakur is touching precisely because it doesn't take place in a world of innocence and naivete; because they both know the risks of love, their gradual acceptance of each other is convincing.

"Boyz N the Hood" was one of the most powerful and influential films of its time, in 1991. "Poetic Justice" is not its equal, but does not aspire to be; it is a softer, gentler film, more of a romance than a commentary on social conditions. Janet Jackson provides a lovable center for it, and by the time it's over we can see more clearly how "Boyz" presented only part of the South Central reality.

Yes, things are hard. But they aren't impossible. Sometimes they're wonderful. And sometimes you can find someone to share them with.

Roger Ebert

Roger Ebert was the film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, he won the Pulitzer Prize for distinguished criticism.

Now playing

Problemista

Monica castillo.

Mary & George

Cristina escobar.

Late Night with the Devil

Matt zoller seitz.

Steve! (Martin): A Documentary in Two Pieces

Brian tallerico.

Ryuichi Sakamoto | Opus

Glenn kenny.

You'll Never Find Me

Sheila o'malley, film credits.

Poetic Justice (1993)

Rated R For Pervasive Strong Language, and For Violence and Sexuality

109 minutes

Janet Jackson as Justice

Tupac Shakur as Mailman

Khandi Alexander as Simone

Tyra Ferrell as Beauty Shop Owner

Maya Angelou as Aunt June

Written and Directed by

- John Singleton

Latest blog posts

Criterion Celebrates the Films That Forever Shifted Our Perception of Kristen Stewart

The Estate of George Carlin Destroys AI George Carlin in Victory for Copyright Protection (and Basic Decency)

The Future of the Movies, Part 3: Fathom Events CEO Ray Nutt

11:11 - Eleven Reviews by Roger Ebert from 2011 in Remembrance of His Transition 11 Years Ago

- One-time / Monthly Donations

- Sponsorship (organizations)

- Newsletters / SMS

- Health Care

- Agriculture

- Oklahoma Elections

- History of the Oklahoma Legislature

- State public resources

- Canadian County

- Cleveland County

- Comanche County

- Oklahoma County

- Tulsa County

- Tribal Nation Pages

Cloudy eclipse could add sadness during darkness

While weird, bunny ears still healthier than Peeps

Podcast: Community journalism, origin stories and an ‘interrupting duck’

Race track ruckus: Stitt trying large wager again

Improper merging? Drummond gives Gatz a citation

Poetic Justice helps Oklahoma’s women prisoners through writing

TULSA — For years, Sarah Garland says she felt dirty and ashamed for some of the things she did in her life. An inmate at a women’s prison in Oklahoma, Garland says poetry has helped her overcome her inner demons.

“I was trying to get involved in anything that would help me stay focused and on the right path,” the 23-year-old said of joining Poetic Justice , a nonprofit organization that teaches poetry and writing workshops to female inmates in Oklahoma’s prisons and jails. Since March 2014, Poetic Justice has given them a chance to rehabilitate through therapeutic writing.

“The thing I love about poetry is it’s the most forgiving of writing mediums,” said Ellen Stackable, the program’s co-founder and executive director. “You can do anything you want, rhyme or not rhyme, it provides a conduit to go directly from your heart to the page without feeling like you’re breaking any rules. For women who have never written in their lives before, the thought of writing and writing about yourself can just seem overwhelming. Poetry provides a voice. And once you have a voice, you have an avenue toward healing and an avenue toward change.”

Oklahoma incarcerates women at twice the national average , with about 151 imprisoned per 100,000 women. Stackable said Poetic Justice has reached about 1,000 women prisoners.

For Garland, who must serve 85 percent of a 15-year sentence for forcible sodomy, juvenile porn and lewd acts to a child, the writing classes offer her a chance to feel accepted.

“As soon as you walk in, you just feel OK and accepted and people care,” Garland said.

She noted that volunteers in the program make sure people don’t feel too exposed, adding that after a woman gets done reading a poem, class leaders ask if the woman wants comments or reflections or silence.

RELATED Incarcerated poets pen verses from Tulsa County jail by John Thompson

“You can have people give you words of encouragement or if you don’t want anything, you can just sit there for a minute and appreciate the writing. It just makes it a really safe environment,” Garland said. “They help you grow so much and pull things out that maybe you didn’t know. As I was writing some stuff, I’ve come to realize how true it is, and it’s come to change my entire outlook. I felt very dirty and bad for some of the things I’ve done, but I know deep down in my heart and soul I’m a good person, and writing has helped me solidify that fact.”

From one Tulsa jail to every women’s prison in Oklahoma

Stackable, who is currently a teacher in Tulsa, was studying for her master’s degree at the University of Oklahoma when she started looking at the state’s incarceration among women. She noted that although she had taught writing for about 20 years, finding a way to reach inmates seemed nearly impossible.

About a year later, a colleague at the Tulsa Schools of Arts and Sciences was doing a spoken word poetry event at the jail for men and invited Stackable along. She went and decided she would start something similar for women.

“Pretty quickly, it moved to therapeutic writing and restorative writing where we’re really trying to help women process through trauma and grief and just confusion,” she said. “It started at the Tulsa Jail with just a couple volunteers and within a year had almost 10 volunteers and four years later, it’s in every women’s prison in Oklahoma.”

In 2017, Poetic Justice released a short documentary called Grey Matter about the program. They are hoping to show it in each of Oklahoma’s 77 counties ahead of this fall’s election season as a way to highlight the women who are incarcerated.

Chairwoman: Writing ‘does so much to bring life to people’

Chairwoman and Tulsa-based elementary school teacher Hanna Al-Jibouri has been involved with the program pretty much from the start.

“I’ve learned so many things,” she said. “Some of the biggest takeaways are to not be afraid to call people out. I think there’s a lot of misconceptions and myths that need to be debunked around what it means to be in jail. More often than not, people don’t actually know what’s going on.”

She said she’s also learned that writing can change somebody’s life.

“That’s what Poetic Justice was founded on,” she said. “The writing can really lead to a creative outlet. It brings communities together. It allows creativity to be ignited. It does so much to bring life to people.”

A 2014 study of inmates who took part in art programming at prisons in California found that creative activities helped the inmates gain greater self-confidence as well as motivate them. Additionally, the study found “… inmate-artists were more likely to strongly agree or agree that they are ‘successful or competent in social situations’ and ‘communicate well with people’ than those without prior arts experience.” Studies also show that the arts can help with time management and self-discipline.

Class structure offers choice

Most classes are two hours long, but the actual writing time lasts only about 15 minutes. The classes start with an introduction to Poetic Justice and an ice-breaker. The women can read their poems and offer reflection. Each class ends with a positive chant about having a voice, hope and the power to change. Then, the poems are collected to eventually be published as a book. Classes in the jail last for six weeks, while the prison classes last for eight weeks. Two to four volunteers run each class.

The women also create their own class norms each week.

“The rules are whatever the women want them to be,” Al-Jibouri said. “That idea of choice and empowerment is super important in any classroom, but it’s even more important for women in jail because they’re not given a chance to have choice.”

Inmate: ‘It does take the edge off and makes you feel better’

Candida Ulibarri took part in the Poetic Justice class at the Tulsa County Jail.

“I’ve always liked poetry, and it just seemed like something to get me out of the environment I was in,” she said.

She said she was able to express herself and release some of her frustrations she was having inside. She wrote about her mom and the stress of being in jail.

“Getting all that off my chest and on paper — it was like a release,” she said. “It does take the edge off and makes you feel better — to have people hear it and accept it and give positive feedback on it also boosts your confidence.”

“When we try to better ourselves, a lot of people just brush us off because we’re inmates or because we’re just a felon or whatever it is,” Garland said. “I just appreciate and absolutely love the fact that [Poetic Justice] come in every day not looking at my DOC number. They make it a point to learn my name. They make it a point to, every time they see me, say my name, to tell me how great I am, to tell me how worthy I am. And they mean it. They genuinely mean it.”

RELATED ARTICLES

Norman High’s Kallan McKinney honored at White House as National Student Poet

This Land is Herland tells the stories of women who shaped Oklahoma

Poetry: ‘Love is such a small word’

French documentary examines Oklahoma’s female incarceration rate

‘Who will come at this desperate hour to sing the soul of Ukraine?’

Poetry: Coyote Communion

Popular articles.

‘Oklahoma lacks jurisdiction’ in Keith Stitt speeding ticket case, U.S. attorneys say

OKC mass recycling event offers proper disposal of eWaste, tires and more

After year of tweaks, electric utilities try to plug ROFR-type transmission bill into Senate

High-speed EV charging stations to reduce ‘range anxiety’ on Oklahoma interstates

‘Used as a test’: OK Supreme Court questions attorneys in Catholic charter school case

- Terms, copyright and conditions

- Privacy statement

Advertisement

Supported by

An Appraisal

John Singleton Did Justice to a Poetic Vision of African-American Life

- Share full article

By A.O. Scott

- April 30, 2019

“Boyz N the Hood” rests in American movie history like a boulder in a riverbed, altering the direction of the stream. After its release in the summer of 1991, everything looked different, including its precursors. “Mean Streets,” “Rebel Without a Cause,” the Blaxploitation spectacles of the 1970s, the socially conscious crime dramas of the 1930s, classic westerns and samurai epics — somehow John Singleton, a very recent graduate of the University of Southern California film school, synthesized all of those models even as he came up with something bracingly, thrillingly and frighteningly new.

“Boyz” made him the youngest person — and the first African-American — nominated for a best directing Academy Award. In the annals of cinema, there aren’t many first features to match it for ambition and impact (“Citizen Kane”? “Breathless”?), and its influence on what came after is hard to overstate. Singleton, who died Monday at 51 , filled his characters’ lives with warmth and humor even as they were constantly menaced, and often destroyed, by violence. He infused familiar coming-of-age and gangster-movie tropes with a rare authenticity. This wasn’t just a matter of his intimate knowledge of the setting known then as South-Central Los Angeles, but also of his brave, even brazen confidence in himself and his audience.

John Singleton, African-American Film Pioneer, Dies at 51

He was best known for directing the 1991 film “boyz n the hood,” a coming-of-age story set in south central los angeles..

The man behind this iconic 1991 film has died. The director John Singleton was 51 years old. His family took him off life support after he had a stroke earlier this month. He’s best known as the director and screenwriter of “Boyz N the Hood,” a coming-of-age story of three black teenagers in South Central Los Angeles. “Wait a minute — hey. Man, this is family business.” The film earned him an Oscar nomination for best director, becoming the first African-American nominee, as well as the youngest, in that category. He was also nominated for best original screenplay. His hometown of Los Angeles featured prominently in many of his films. “You know, at film school they always teach you write about what you know. And I was like, wow, you know, this is what I know. This is where I’m from. So, I can do something different. I can make something that is really about where we’re from in South Central Los Angeles.” Singleton took an early interest in film during his younger years. “My mother used to take my little rolls of film to the lab and get them made for me — developed for me in high school. So, I wouldn’t be — I wouldn’t be where I am if it wasn’t for my mother. Growing up, he was influenced by “Cooley High” and Spike Lee’s “She’s Gotta Have It.” After “Boyz N the Hood,” he would go on to direct in a variety of genres. He went on to inspire and mentor many African-American filmmakers and actors.

[Read the John Singleton obituary and a recent interview with him. | See where to stream his best films.]

A blazing debut can be a hard act to follow, and Singleton’s second film, “Poetic Justice” (1993), didn’t enjoy the same success, at least with critics , as its predecessor. But when I heard the news of Singleton’s passing, “ Poetic Justice ” was the movie I found myself thinking about. Partly because its earnest sentiments — its open-heartedness about creativity, love and loss — seemed most apt for mourning an artist who left too soon. Grief, after all, has been part of the film’s legacy since its male star, Tupac Shakur, was murdered in 1996. And there may be no purer dose of early-’90s nostalgia than watching Shakur and Janet Jackson travel the romantic-comedy arc, their progress from conflict to harmony punctuated by the poems of Maya Angelou and breathtaking vistas of the California countryside.

“Poetic Justice” is, in its way, as influential as “Boyz N the Hood” and as political as “ Higher Learning ” and “ Rosewood ,” Singleton’s subsequent confrontations with past and present-day manifestations of American racism. “Poetic Justice” begins with a sly and pointed critique of Hollywood representation. A note tells us we’re in South-Central, but the images are of high-rise, well-heeled Manhattan, where a white couple, played by Billy Zane and Lori Petty, are drinking wine in a penthouse.

The joke is that this is a movie-within-the-movie showing at a Los Angeles drive-in. (The marquee tells us that it’s called “Deadly Diva” and has an NC-17 rating.) The patrons, including Jackson’s Justice and her boyfriend (Q-Tip of A Tribe Called Quest), don’t look like the people onscreen, but they’ve bought tickets anyway, as generations of black and Latinx moviegoers have before them. With a few exceptions, it’s always been that way.

“Poetic Justice” sets out to change that situation, by every means available. The stylized, consequence-free gunplay of “Deadly Diva” is soon drowned out by a shooting that pulls what seemed like an ’80s-vintage teen comedy into the brutal world of “Boyz N the Hood.” Within a few minutes, before the opening titles have even scrolled, we’ve swerved from satire to sex farce to tragedy, and Singleton is only getting started.

Eventually, Justice and Lucky (Shakur’s character) will set off for Oakland in a Postal Service truck with their friends Iesha (Regina King) and Chicago (Joe Torry), and “Poetic Justice” will turn into a road movie. Before their departure, Singleton lingers over the funny and painful details of their lives at home and at work, sketching a portrait of working-class black life that looks back to the radical neo-realism of the L.A. Rebellion and forward to the businesslike striving of the “Barbershop” franchise. The casting of two stars of popular music as a hairdresser (Jackson) and a mailman (Shakur) doesn’t so much glamorize the characters as affirm the realness that the performers had already established as the cornerstone of their appeal.

Between Los Angeles and the Bay Area, the four travelers journey through a kind of utopian space. Not that everything is harmonious among them. Iesha and Chicago have some issues, and Lucky and Justice are barely on speaking terms. Harsh words are exchanged , followed by a few slaps and punches. But the movie’s close attention to this interpersonal friction might cause you to notice what isn’t in the picture. There are no police on the highway and almost no white people (except for a belligerent truck driver at a gas station). Justice and company crash a family reunion, where Maya Angelou herself dispenses wisdom and passes judgment on her temporary nieces and nephews. They stop at a cultural festival where revolutionary poets and drummers hold the stage.

This dream evaporates in Oakland, where a shooting has claimed the life of Lucky’s cousin and rap partner. The point of the film’s long, languorous middle was never to imagine an escape from violence and racism, but to show some of the richness and variety of life in their shadows, to free the characters from the obligation to behave like symbols or avatars of social problems.

Watching “Poetic Justice” now, I was put in mind of Barry Jenkins’s recent “If Beale Street Could Talk,” and not only because Regina King is (splendidly) in both films. Their visual and storytelling styles are very different, but Jenkins and Singleton are directors whose primary motivation is their unstinting love for the people they conjure into being.

They push aside the noise of plot to capture the quiet intensity of ordinary moments and the poetry of everyday experience. They notice beauty everywhere. “Beale Street” and “Poetic Justice” are stories of black artists falling in love in a world that tends to devalue both their creativity and their feelings, and each movie simultaneously illuminates those struggles and shares in them, in a spirit that is sorrowful but never grim or despairing.

My point isn’t to establish a lineage, but to identify a common spirit, and to measure the shape and size of the doorway that Singleton made, an opening wide enough for so many others to walk through.

An earlier version of a picture caption with this article misspelled the surname of the writer pictured with John Singleton. She is Maya Angelou, not Angelous. Another picture caption reversed the names of the actors Janet Jackson and Regina King.

How we handle corrections

Explore More in TV and Movies

Not sure what to watch next we can help..

Maya Rudolph and Kristen Wiig have wound in and out of each other’s lives and careers for decades. Now they are both headlining an Apple TV+ comedy of wealth and status .

Nicholas Galitzine, known for playing princes and their modern equivalents, hopes his steamy new drama, “Mary & George,” will change how Hollywood sees him .

Ewan McGregor and Mary Elizabeth met while filming “Fargo” in 2017. Now married, they have reunited onscreen in “A Gentleman in Moscow.”

A reboot of “Gladiators,” the musclebound 1990s staple, has attracted millions of viewers in Britain. Is appointment television back ?

If you are overwhelmed by the endless options, don’t despair — we put together the best offerings on Netflix , Max , Disney+ , Amazon Prime and Hulu to make choosing your next binge a little easier.

Sign up for our Watching newsletter to get recommendations on the best films and TV shows to stream and watch, delivered to your inbox.

Log in or sign up for Rotten Tomatoes

Trouble logging in?

By continuing, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes and to receive email from the Fandango Media Brands .

By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes.

Email not verified

Let's keep in touch.

Sign up for the Rotten Tomatoes newsletter to get weekly updates on:

- Upcoming Movies and TV shows

- Trivia & Rotten Tomatoes Podcast

- Media News + More

By clicking "Sign Me Up," you are agreeing to receive occasional emails and communications from Fandango Media (Fandango, Vudu, and Rotten Tomatoes) and consenting to Fandango's Privacy Policy and Terms and Policies . Please allow 10 business days for your account to reflect your preferences.

OK, got it!

Movies / TV

No results found.

- What's the Tomatometer®?

- Login/signup

Movies in theaters

- Opening this week

- Top box office

- Coming soon to theaters

- Certified fresh movies

Movies at home

- Netflix streaming

- Prime Video

- Most popular streaming movies

- What to Watch New

Certified fresh picks

- Monkey Man Link to Monkey Man

- The First Omen Link to The First Omen

- The Beast Link to The Beast

New TV Tonight

- Chucky: Season 3

- Mr Bates vs The Post Office: Season 1

- Fallout: Season 1

- Franklin: Season 1

- Dora: Season 1

- Good Times: Season 1

- Beacon 23: Season 2

Most Popular TV on RT

- Ripley: Season 1

- Sugar: Season 1

- 3 Body Problem: Season 1

- A Gentleman in Moscow: Season 1

- We Were the Lucky Ones: Season 1

- Parasyte: The Grey: Season 1

- Shōgun: Season 1

- The Gentlemen: Season 1

- Manhunt: Season 1

- Best TV Shows

- Most Popular TV

- TV & Streaming News

Certified fresh pick

- Ripley Link to Ripley

- All-Time Lists

- Binge Guide

- Comics on TV

- Five Favorite Films

- Video Interviews

- Weekend Box Office

- Weekly Ketchup

- What to Watch

100 Best Free Movies on YouTube (April 2024)

Pedro Pascal Movies and Series Ranked by Tomatometer

What to Watch: In Theaters and On Streaming

Awards Tour

TV Premiere Dates 2024

New Movies & TV Shows Streaming in April 2024: What To Watch on Netflix, Prime Video, Disney+, and More

- Trending on RT

- Play Movie Trivia

- Best New Movies

- New On Streaming

Poetic Justice

1993, Romance/Comedy, 1h 50m

What to know

Critics Consensus

Poetic Justice is commendably ambitious and boasts a pair of appealing stars, but they're undermined by writer-director John Singleton's frustrating lack of discipline. Read critic reviews

You might also like

Where to watch poetic justice.

Rent Poetic Justice on Prime Video, Apple TV, Vudu, or buy it on Prime Video, Apple TV, Vudu.

Rate And Review

Super Reviewer

Rate this movie

Oof, that was Rotten.

Meh, it passed the time.

It’s good – I’d recommend it.

So Fresh: Absolute Must See!

What did you think of the movie? (optional)

You're almost there! Just confirm how you got your ticket.

Step 2 of 2

How did you buy your ticket?

Let's get your review verified..

AMCTheatres.com or AMC App New

Cinemark Coming Soon

We won’t be able to verify your ticket today, but it’s great to know for the future.

Regal Coming Soon

Theater box office or somewhere else

By opting to have your ticket verified for this movie, you are allowing us to check the email address associated with your Rotten Tomatoes account against an email address associated with a Fandango ticket purchase for the same movie.

You're almost there! Just confirm how you got your ticket.

Poetic justice videos, poetic justice photos.

Still grieving after the murder of her boyfriend, hairdresser Justice (Janet Jackson) writes poetry to deal with the pain of her loss. Unable to get to Oakland to attend a convention because of her broken-down car, Justice gets a lift with her friend, Iesha (Regina King) and Iesha's postal worker boyfriend, Chicago (Joe Torry). Along for the ride is Chicago's co-worker, Lucky (Tupac Shakur), to whom Justice grows close after some initial problems. But is she ready to open her heart again?

Genre: Romance, Comedy

Original Language: English

Director: John Singleton

Producer: Steve Nicolaides , John Singleton

Writer: John Singleton

Release Date (Theaters): Jul 23, 1993 wide

Release Date (Streaming): Jan 3, 2016

Box Office (Gross USA): $27.5M

Runtime: 1h 50m

Distributor: Columbia Pictures, Columbia Tristar

Production Co: New Deal Productions, Sony Pictures, Columbia Pictures Corporation

Sound Mix: Surround

Cast & Crew

Janet Jackson

Tupac Shakur

Regina King

Maya Angelou

Tyra Ferrell

Roger Guenveur Smith

John Singleton

Screenwriter

Steve Nicolaides

Peter Collister

Cinematographer

Bruce Cannon

Film Editing

Stanley Clarke

Original Music

Keith Brian Burns

Production Design

Kirk M. Petruccelli

Art Director

Daniel Loren May

Set Decoration

Darryle Johnson

Costume Design

News & Interviews for Poetic Justice

Yvonne Orji’s Five Favorite Films

Critic Reviews for Poetic Justice

Audience reviews for poetic justice.

Great opening. John Singleton laces nods to classic battle-of-the-sexes flicks through the DNA of his modern-day South Central roadtrip relationship drama. Jackson and Shakur both give tender performances as equally stubborn PYTs and they've got the chemistry to boot. Because 'Poetic Justice' tries to cover a lot of ground narratively, particularly with the supporting couple's relationship, I feel like we miss more of the backend development of Justice and Lucky's romance. A lot of screentime is devoted to how much they don't get along and not enough to the elements they are genuinely connecting over (everyone's excessive bickering does become grating). The transitions are a tad clunky at times, but the omnipresent theme of harmony keeps 'Justice' engaging throughout. Singleton uses his flawed characters wisely to demonstrate the chaos they bring onto themselves and it's exactly that transparency that keeps me onboard as they stumble and claw for the best versions of themselves.

Not one of Singleton's best, but the story was ok. The actors/singers placed to play the lead characters were a bit annoying, but Regina King was the best whom always get's into her role, and stole the show from the two main characters. Mayo Angelou's poems are great, which is quoted by Janet Jackson in this ok movie. I liked it and it was amusing, but they just did not bring out the roles as they should have.

1 of my favorite movies RIP 2pac

I had my fingers crossed for a sex scene between <a href="http://www.flixster.com/actor/tupac-shakur">Tupac</a> and <a href="http://www.flixster.com/actor/maya-angelou">Maya Angelou</a>.

Movie & TV guides

Play Daily Tomato Movie Trivia

Discover What to Watch

Rotten Tomatoes Podcasts

How Our Paper Writing Service Is Used

We stand for academic honesty and obey all institutional laws. Therefore EssayService strongly advises its clients to use the provided work as a study aid, as a source of ideas and information, or for citations. Work provided by us is NOT supposed to be submitted OR forwarded as a final work. It is meant to be used for research purposes, drafts, or as extra study materials.

Courtney Lees

Gustavo Almeida Correia

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

poetry. justice. poetic justice, in literature, an outcome in which vice is punished and virtue rewarded, usually in a manner peculiarly or ironically appropriate. The term was coined by the English literary critic Thomas Rymer in the 17th century, when it was believed that a work of literature should uphold moral principles and instruct the ...

The definition of poetic justice was created by the English drama critic Thomas Rymer in 1678 in his book The Tragedies of the Last Age Considere'd.He urged authors to set moral examples and show how good overcomes evil. Indeed, Rymer was a critic at a time when it was thought that the role of literature was to provide moral education to the reading populace.

Good Essays. 1943 Words. 8 Pages. Open Document. Poetic justice is a prominent theme throughout many genres of literature. The definition of poetic justice is: "an outcome in which vice is punished and virtue rewarded usually in a manner peculiarly or ironically appropriate" (Poetic Justice). This implies that the ending of the plot and the ...

Poetic Justice Definition. In literature, poetic justice is an ideal form of justice, in which the good characters are rewarded and the bad characters are punished, by an ironic twist of fate. It is a strong literary view that all forms of literature must convey moral lessons. Therefore, writers employ poetic justice to conform to moral principles.

3 Examples of Poetic Justice. There are many stories in literature that use poetic justice as a literary device: 1. Oedipus Rex by Sophocles: A play that follows the King of Thebes, Oedipus, as he seeks out the murderer of Laius, the previous king. The story takes on an ironic manner as Oedipus eventually discovers that he is the murderer and ...

In a famous essay, "Nomos and Narrative," Robert Cover linked the communication and the application of legal norms to narrative. This article presents an alternative, anti-normative, and anti-narrative, notion of the relation between poetry and justice that one might call "a-nomos and lyric.". It argues that an alternative conception of ...

Poetic justice. Poetic justice, also called poetic irony, is a literary device with which ultimately virtue is rewarded and misdeeds are punished. In modern literature, [1] it is often accompanied by an ironic twist of fate related to the character's own action, hence the name poetic irony. [2]

Literature reveals the intense efforts of moral imagination required to articulate what justice is and how it might be satisfied. Examining a wide variety of texts including Shakespeare's plays, Gilbert and Sullivan's operas, and modernist poetics, Poetic Justice and Legal Fictions explores how literary laws and values illuminate and challenge the jurisdiction of justice and the law.

The term "poetic justice" is a combination of two words: poetic and justice. The word "poetic" comes from the Latin word poeticus.It has its roots in the Greek term poietikos, which means "pertaining to poetry or creation." "Justice," on the other hand, comes from the Latin word justitia, stemming from the Latin adjective justus, meaning "righteous" or "fair."

In Lesson 2, students will consider how poetry can be used for justice by analyzing "Disappearing Daughters" and "A Spoken Word Poet in Myanmar Speaks Out Against Hate and Injustice." In Lessons 3 and 4, students will brainstorm ideas for, write, and perform poems about justice issues that matter to them. Resources for Facilitating this Unit ...

Poetry and Racial Justice and Equality. Witnessing the struggle for freedom, from the American Revolution to the Black Lives Matter movement. Photo by Michael Nigro/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images. Even though its founding documents profess an egalitarian vision of opportunity and equal treatment of its citizens, rights and liberties ...

An Analysis of Poetic Justice in Macbeth. The play Macbeth written by William Shakespeare is a story about a man named Macbeth and his quest for power. In the beginning of the play, Macbeth is a brave and noble soldier, who is crowned as Thane of Cawdor by King Duncan. After becoming Thane of Cawdor he and Banquo come across three witches who ...

Don't you take it awful hard. 'Cause I laugh like I've got gold mines. Diggin' in my own backyard. You may shoot me with your words, You may cut me with your eyes, You may kill me with your hatefulness, But still, like air, I'll rise.

The Poetic Justice. The Poetic Justice. A Memoir and Moving Speech Capture Spirit of John Charles Thomas '75. ... short story or essay. Although he had been reciting poetry since he was 4, it never occurred to him that he could write a poem of his own. "And so, in that 20 minutes — with my life on the line and it was going to be in the ...

Poetic justice in literature occurs when virtue is rewarded and evil punished. In his essay, Dryden contends that the French dramatists are superior to the Greek in that they adhere strictly to ...

Poetic Justice 's focus on the trauma and recovery of young black women in urban environments defied traditional expectations of who can be at the center of cinematic narratives. That John ...

"Poetic Justice" is described as the second of three films John Singleton plans to make about the South Central neighborhood in Los Angeles.. His first, "Boyz N the Hood," showed a young black man growing up in an atmosphere of street violence, but encouraged by his father to stand aside from the gangs and shootings and place a higher worth on his life.

The aspects that characterize it as an urban legend can be found within our readings as well. The biggest and most distinct example being poetic justice. Poetic Justice is repeatedly seen as a characteristic in Urban Legends such as The Hook. The Hook showing its poetic justice on the boyfriend that repeatedly tries to pressures the female into ...

Stackable said Poetic Justice has reached about 1,000 women prisoners. For Garland, who must serve 85 percent of a 15-year sentence for forcible sodomy, juvenile porn and lewd acts to a child, the ...

Analytical Essay: Poetic Justice in Macbeth The Tragedy of Macbeth, authored by William Shakespeare, uses several techniques to elucidate what poetic justice is in a story. Simply with logic being rewarded or corruption being punished by an act closely relatable to a character's own conduct.

Maya Angelou with John Singleton in 1993, the year "Poetic Justice" was released. Columbia Pictures, via Everett Collection. "Boyz N the Hood" rests in American movie history like a ...

Still grieving after the murder of her boyfriend, hairdresser Justice (Janet Jackson) writes poetry to deal with the pain of her loss. Unable to get to Oakland to attend a convention because of ...

Experts to Provide You Writing Essays Service. You can assign your order to: Basic writer. In this case, your paper will be completed by a standard author. ... Poetic Justice Essay, Writing Essays Contest High School, Academic Writing Style Third Person, Business Keys To Success For A Business Plan, Assignments For Hdip Assignment, Professional ...