The Tech Edvocate

- Advertisement

- Home Page Five (No Sidebar)

- Home Page Four

- Home Page Three

- Home Page Two

- Icons [No Sidebar]

- Left Sidbear Page

- Lynch Educational Consulting

- My Speaking Page

- Newsletter Sign Up Confirmation

- Newsletter Unsubscription

- Page Example

- Privacy Policy

- Protected Content

- Request a Product Review

- Shortcodes Examples

- Terms and Conditions

- The Edvocate

- The Tech Edvocate Product Guide

- Write For Us

- Dr. Lynch’s Personal Website

- The Edvocate Podcast

- Assistive Technology

- Child Development Tech

- Early Childhood & K-12 EdTech

- EdTech Futures

- EdTech News

- EdTech Policy & Reform

- EdTech Startups & Businesses

- Higher Education EdTech

- Online Learning & eLearning

- Parent & Family Tech

- Personalized Learning

- Product Reviews

- Tech Edvocate Awards

- School Ratings

3 Ways to Take Care of a Stray Cat

How to palm a basketball: 12 steps, 3 ways to react if you learn your partner is married, 3 ways to debadge your car, how to update android apps from your pc, 3 simple ways to wash an acrylic sweater, how to live free: 15 steps, 3 ways to subtract thousands, 3 ways to make a hair puff, how to play township, how to write an article review (with sample reviews) .

An article review is a critical evaluation of a scholarly or scientific piece, which aims to summarize its main ideas, assess its contributions, and provide constructive feedback. A well-written review not only benefits the author of the article under scrutiny but also serves as a valuable resource for fellow researchers and scholars. Follow these steps to create an effective and informative article review:

1. Understand the purpose: Before diving into the article, it is important to understand the intent of writing a review. This helps in focusing your thoughts, directing your analysis, and ensuring your review adds value to the academic community.

2. Read the article thoroughly: Carefully read the article multiple times to get a complete understanding of its content, arguments, and conclusions. As you read, take notes on key points, supporting evidence, and any areas that require further exploration or clarification.

3. Summarize the main ideas: In your review’s introduction, briefly outline the primary themes and arguments presented by the author(s). Keep it concise but sufficiently informative so that readers can quickly grasp the essence of the article.

4. Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses: In subsequent paragraphs, assess the strengths and limitations of the article based on factors such as methodology, quality of evidence presented, coherence of arguments, and alignment with existing literature in the field. Be fair and objective while providing your critique.

5. Discuss any implications: Deliberate on how this particular piece contributes to or challenges existing knowledge in its discipline. You may also discuss potential improvements for future research or explore real-world applications stemming from this study.

6. Provide recommendations: Finally, offer suggestions for both the author(s) and readers regarding how they can further build on this work or apply its findings in practice.

7. Proofread and revise: Once your initial draft is complete, go through it carefully for clarity, accuracy, and coherence. Revise as necessary, ensuring your review is both informative and engaging for readers.

Sample Review:

A Critical Review of “The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health”

Introduction:

“The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health” is a timely article which investigates the relationship between social media usage and psychological well-being. The authors present compelling evidence to support their argument that excessive use of social media can result in decreased self-esteem, increased anxiety, and a negative impact on interpersonal relationships.

Strengths and weaknesses:

One of the strengths of this article lies in its well-structured methodology utilizing a variety of sources, including quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews. This approach provides a comprehensive view of the topic, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of the effects of social media on mental health. However, it would have been beneficial if the authors included a larger sample size to increase the reliability of their conclusions. Additionally, exploring how different platforms may influence mental health differently could have added depth to the analysis.

Implications:

The findings in this article contribute significantly to ongoing debates surrounding the psychological implications of social media use. It highlights the potential dangers that excessive engagement with online platforms may pose to one’s mental well-being and encourages further research into interventions that could mitigate these risks. The study also offers an opportunity for educators and policy-makers to take note and develop strategies to foster healthier online behavior.

Recommendations:

Future researchers should consider investigating how specific social media platforms impact mental health outcomes, as this could lead to more targeted interventions. For practitioners, implementing educational programs aimed at promoting healthy online habits may be beneficial in mitigating the potential negative consequences associated with excessive social media use.

Conclusion:

Overall, “The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health” is an important and informative piece that raises awareness about a pressing issue in today’s digital age. Given its minor limitations, it provides valuable

3 Ways to Make a Mini Greenhouse ...

3 ways to teach yourself to play ....

Matthew Lynch

Related articles more from author.

How to Make a Plastic Bag Holder

3 Ways to Use Black Seed

4 Ways to Clean Ball Bearings

3 Ways to Remove Wrinkles from a Tie

13 Easy Ways to Avoid Someone You Are Attracted to

3 Ways to Treat Seborrheic Dermatitis

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Critical Reviews

How to Write an Article Review

Last Updated: September 8, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Jake Adams . Jake Adams is an academic tutor and the owner of Simplifi EDU, a Santa Monica, California based online tutoring business offering learning resources and online tutors for academic subjects K-College, SAT & ACT prep, and college admissions applications. With over 14 years of professional tutoring experience, Jake is dedicated to providing his clients the very best online tutoring experience and access to a network of excellent undergraduate and graduate-level tutors from top colleges all over the nation. Jake holds a BS in International Business and Marketing from Pepperdine University. There are 13 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 3,087,631 times.

An article review is both a summary and an evaluation of another writer's article. Teachers often assign article reviews to introduce students to the work of experts in the field. Experts also are often asked to review the work of other professionals. Understanding the main points and arguments of the article is essential for an accurate summation. Logical evaluation of the article's main theme, supporting arguments, and implications for further research is an important element of a review . Here are a few guidelines for writing an article review.

Education specialist Alexander Peterman recommends: "In the case of a review, your objective should be to reflect on the effectiveness of what has already been written, rather than writing to inform your audience about a subject."

Things You Should Know

- Read the article very closely, and then take time to reflect on your evaluation. Consider whether the article effectively achieves what it set out to.

- Write out a full article review by completing your intro, summary, evaluation, and conclusion. Don't forget to add a title, too!

- Proofread your review for mistakes (like grammar and usage), while also cutting down on needless information. [1] X Research source

Preparing to Write Your Review

- Article reviews present more than just an opinion. You will engage with the text to create a response to the scholarly writer's ideas. You will respond to and use ideas, theories, and research from your studies. Your critique of the article will be based on proof and your own thoughtful reasoning.

- An article review only responds to the author's research. It typically does not provide any new research. However, if you are correcting misleading or otherwise incorrect points, some new data may be presented.

- An article review both summarizes and evaluates the article.

- Summarize the article. Focus on the important points, claims, and information.

- Discuss the positive aspects of the article. Think about what the author does well, good points she makes, and insightful observations.

- Identify contradictions, gaps, and inconsistencies in the text. Determine if there is enough data or research included to support the author's claims. Find any unanswered questions left in the article.

- Make note of words or issues you don't understand and questions you have.

- Look up terms or concepts you are unfamiliar with, so you can fully understand the article. Read about concepts in-depth to make sure you understand their full context.

- Pay careful attention to the meaning of the article. Make sure you fully understand the article. The only way to write a good article review is to understand the article.

- With either method, make an outline of the main points made in the article and the supporting research or arguments. It is strictly a restatement of the main points of the article and does not include your opinions.

- After putting the article in your own words, decide which parts of the article you want to discuss in your review. You can focus on the theoretical approach, the content, the presentation or interpretation of evidence, or the style. You will always discuss the main issues of the article, but you can sometimes also focus on certain aspects. This comes in handy if you want to focus the review towards the content of a course.

- Review the summary outline to eliminate unnecessary items. Erase or cross out the less important arguments or supplemental information. Your revised summary can serve as the basis for the summary you provide at the beginning of your review.

- What does the article set out to do?

- What is the theoretical framework or assumptions?

- Are the central concepts clearly defined?

- How adequate is the evidence?

- How does the article fit into the literature and field?

- Does it advance the knowledge of the subject?

- How clear is the author's writing? Don't: include superficial opinions or your personal reaction. Do: pay attention to your biases, so you can overcome them.

Writing the Article Review

- For example, in MLA , a citation may look like: Duvall, John N. "The (Super)Marketplace of Images: Television as Unmediated Mediation in DeLillo's White Noise ." Arizona Quarterly 50.3 (1994): 127-53. Print. [10] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- For example: The article, "Condom use will increase the spread of AIDS," was written by Anthony Zimmerman, a Catholic priest.

- Your introduction should only be 10-25% of your review.

- End the introduction with your thesis. Your thesis should address the above issues. For example: Although the author has some good points, his article is biased and contains some misinterpretation of data from others’ analysis of the effectiveness of the condom.

- Use direct quotes from the author sparingly.

- Review the summary you have written. Read over your summary many times to ensure that your words are an accurate description of the author's article.

- Support your critique with evidence from the article or other texts.

- The summary portion is very important for your critique. You must make the author's argument clear in the summary section for your evaluation to make sense.

- Remember, this is not where you say if you liked the article or not. You are assessing the significance and relevance of the article.

- Use a topic sentence and supportive arguments for each opinion. For example, you might address a particular strength in the first sentence of the opinion section, followed by several sentences elaborating on the significance of the point.

- This should only be about 10% of your overall essay.

- For example: This critical review has evaluated the article "Condom use will increase the spread of AIDS" by Anthony Zimmerman. The arguments in the article show the presence of bias, prejudice, argumentative writing without supporting details, and misinformation. These points weaken the author’s arguments and reduce his credibility.

- Make sure you have identified and discussed the 3-4 key issues in the article.

Sample Article Reviews

Expert Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/grammarpunct/proofreading/

- ↑ https://libguides.cmich.edu/writinghelp/articlereview

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4548566/

- ↑ Jake Adams. Academic Tutor & Test Prep Specialist. Expert Interview. 24 July 2020.

- ↑ https://guides.library.queensu.ca/introduction-research/writing/critical

- ↑ https://www.iup.edu/writingcenter/writing-resources/organization-and-structure/creating-an-outline.html

- ↑ https://writing.umn.edu/sws/assets/pdf/quicktips/titles.pdf

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/mla_style/mla_formatting_and_style_guide/mla_works_cited_periodicals.html

- ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4548565/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/593/2014/06/How_to_Summarize_a_Research_Article1.pdf

- ↑ https://www.uis.edu/learning-hub/writing-resources/handouts/learning-hub/how-to-review-a-journal-article

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/editing-and-proofreading/

About This Article

If you have to write an article review, read through the original article closely, taking notes and highlighting important sections as you read. Next, rewrite the article in your own words, either in a long paragraph or as an outline. Open your article review by citing the article, then write an introduction which states the article’s thesis. Next, summarize the article, followed by your opinion about whether the article was clear, thorough, and useful. Finish with a paragraph that summarizes the main points of the article and your opinions. To learn more about what to include in your personal critique of the article, keep reading the article! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Prince Asiedu-Gyan

Apr 22, 2022

Did this article help you?

Sammy James

Sep 12, 2017

Juabin Matey

Aug 30, 2017

Oct 25, 2023

Vanita Meghrajani

Jul 21, 2016

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

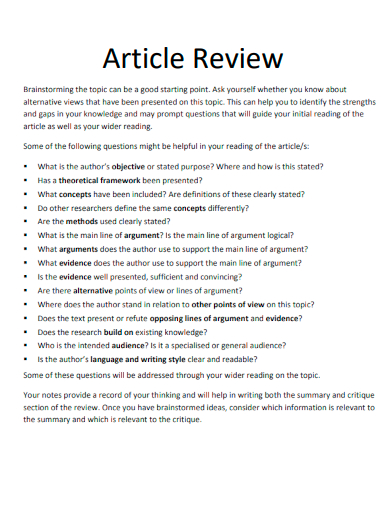

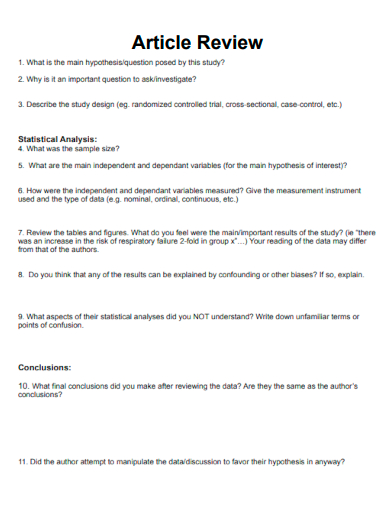

Article Review

Article reviews are an essential part of academic article writing , providing an opportunity to evaluate and analyze published research. A well-written review can help readers understand the simple subject matter and determine the value of the article. In this article, we’ll cover what is an article review, provide step-by-step guidance on how to write one, and answer some common questions.

[bb_toc content=”][/bb_toc]

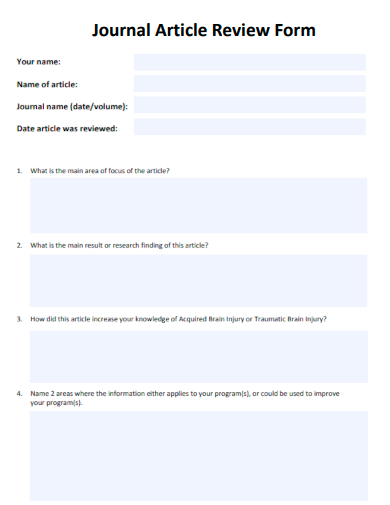

1. Journal Article Review Form

Size: 84 KB

2. Article Review & Critique

Size: 420 KB

3. Formal Article Review

Size: 188 KB

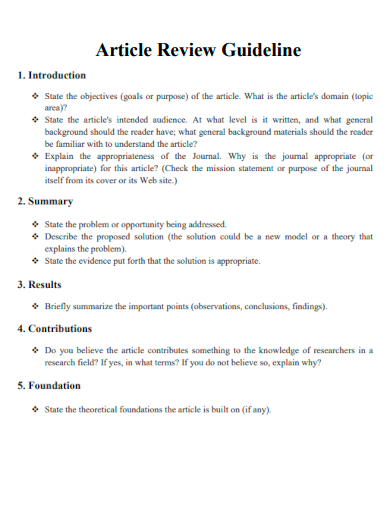

4. Article Review Guideline

Size: 157 KB

5. Book and Article Reviews

Size: 284 KB

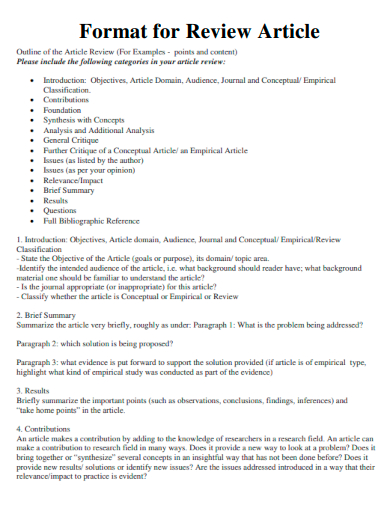

6. Format for Review Article

Size: 71 KB

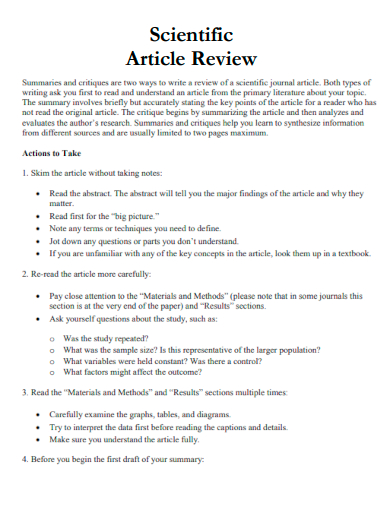

7. Scientific Article Review

Size: 258 KB

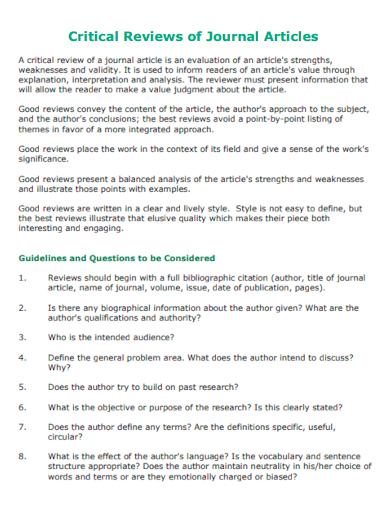

8. Critical Reviews of Journal Articles

Size: 50 KB

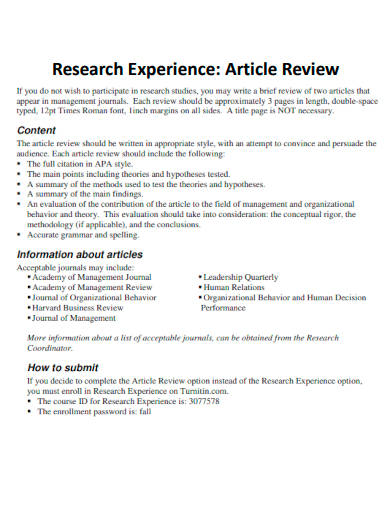

9. Research Experience Article Review

Size: 31 KB

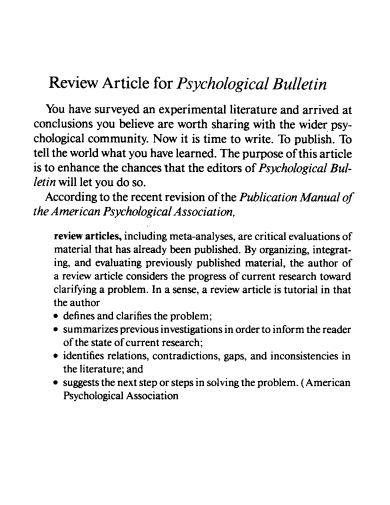

10. Review for Article Psychological Bulletin

11. Article Format Guide Review

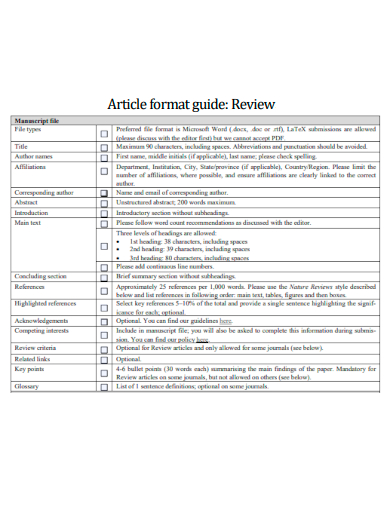

Size: 449 KB

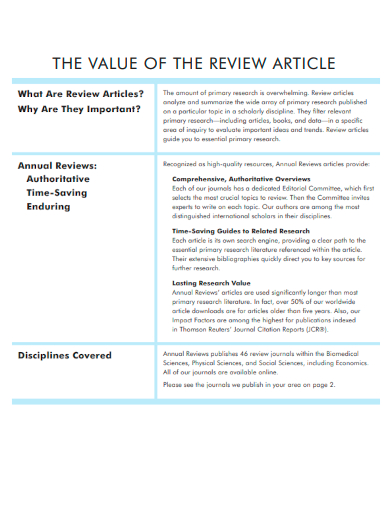

12. Value Of Review Article

Size: 51 KB

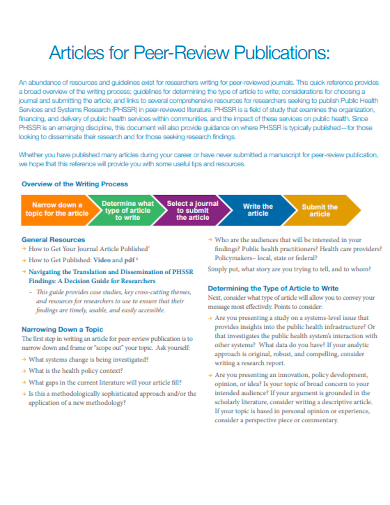

13. Articles for Peer-Review Publications

Size: 181 KB

14. Law Review Article Selection Process

15. Creative Article Review

Size: 46 KB

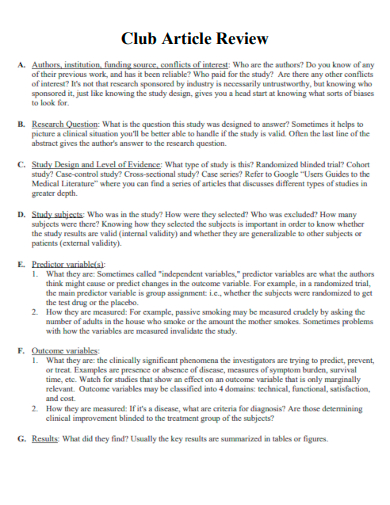

16. Club Article Review

Size: 77 KB

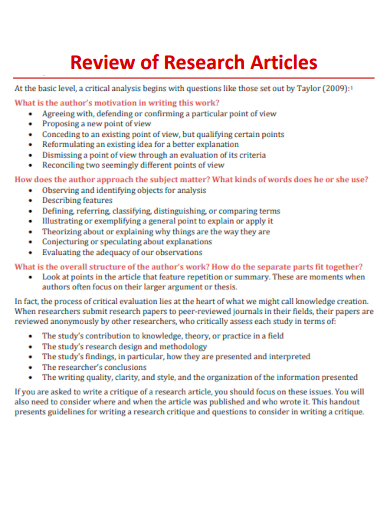

17. Review of Research Articles

Size: 152 KB

What is an Article Review

An article review is a critical assessment of a scholarly article or research paper. It involves analyzing the content, methodology, and findings of the article and providing an evaluation of its strengths and weaknesses. The review typically includes a summary of the article’s main points, an evaluation of its contribution to the subject, and suggestions for improvement.

How to Write an Article Review

Writing an article review can be a challenging task, but it’s an essential skill for students and researchers alike. Here’s a step-by-step guide to help you write an effective article review:

Choose the article to review

Select an article that is relevant to your subject and interests you. Make sure the article is recent, reputable, and published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Read the article carefully

Read the article thoroughly and take notes as you go. Pay attention to the author’s thesis statement, research question, methodology, and findings.

Identify the main points and key arguments

Determine the main points and arguments of the article. Look for evidence that supports the author’s thesis statement.

Evaluate the article’s methodology and research design

Evaluate the methodology and research design used in the article. Determine if the research methods were appropriate and effective in answering the research question.

Assess the article’s strengths and weaknesses

Identify the strengths and weaknesses of the article. Evaluate the quality of the evidence presented and the logic of the arguments made.

Write a summary of the article

Summarize the article in your own words. Include the main points, key arguments, and findings of the article.

Write the main body of the review

In the main body of the review, analyze and evaluate the article. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the article and provide evidence to support your claims.

Conclude with a final evaluation and recommendations for improvement

Conclude your review with a final evaluation conclusion of the article. Highlight its strengths and weaknesses and provide recommendations for improvement.

Proofread and edit the review

After completing your review, proofread and edit it carefully. Check for spelling, grammar, and punctuation errors. Make sure your review is clear, concise, and well-organized.

What is the difference between an article review and a literature review?

A literature review is a comprehensive analysis of published research on a particular subject, while an article review focuses specifically on one article.

Can I use first-person sentences in an article review?

It depends on the guidelines given by your instructor or the publication you are submitting the review to. Generally, using the third person is more appropriate for academic writing sentences .

Should I include the abstract of the article in my review?

Yes, including a brief summary of the article’s abstract is usually a good idea.

How long should an article review be?

The length of an article review varies depending on the subject and the publication requirements. Generally, a review should be between 500 and 1000 words.

Writing an effective article review requires careful analysis, evaluation, and critique of the article. By following our step-by-step guide, you can develop the skills to write a comprehensive and insightful review that provides valuable information to readers. Whether you’re reviewing an academic article, book or manuscript , or any other subject, the tips and techniques outlined here will help you write an effective article review.

AI Generator

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Examples of Public speaking

20 Examples of Gas lighting

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Sample article review

While change of events is a fact of life on projects, project performance problems are fundamentally dynamic problems that result from attempts to manage in the face of change and uncertainty. With the growing complexity of projects, some weaknesses of traditional approaches in coping with the strategic issues are being highlighted. Many scholars have been studying this and suggest system design as a solution and gave their own assessments; this paper primarily discusses and reviews the works of 4 articles, Using systems dynamics to better understand change and rework in construction project management systems [1] by P.E.D. Lovea, G.D. Holta, L.Y. Shenb, H. Lib, Z. Iranic; System dynamics in project management, Assessing the impacts of client behavior on Project Performance [2] by Alexander G, Rodrigus and Terry M.Williams; A system dynamics approach to risks description in megaprojects development [3] by Prince Boateng, Zhen Chen, Stephen Ogunlana and Dubem Ikediashi; and The role of system dynamics in project management, A comparative Analysis with tradition methods [4] by Alexander G, Rodrigus

Related Papers

PRINCE BOATENG , Zhen Chen

Stephen O Ogunlana

Keywords the inherent risks and their interactive impacts in megaproject develop-ment have been found in numerous cases across the world. Although risk management standards have been recommended for the best practice, there is still a lack of systematic approaches to describing the interaction among social, technical, economic, environmental and political (STEEP) risks with regard to all complex and dynamic conditions of megaproject construction for better understanding and effective management of the management mechanism in terms of the nature risks, including their dynamic interactions and impacts in megaproject development. Purpose – Present a model to describe STEEP risks and their interactions in megaproject development. Design/methodology/approach – A case study methodology is adopted. Following comprehensive literature review, qualitative data were gath-ered from case studies through interview conducted on Tram Network Project in Edinburgh. Casual loops of typical evolution o...

Engineering, Construction and …

Stephen O Ogunlana , Long Nguyen

PRINCE BOATENG

IAEME Publication

A construction megaproject is defined in literature as a construction project, or aggregate of such projects, characterized by magnified cost, extreme complexity, increased risk, lofty ideals, and high visibility, in a combination that represents a significant challenge to the stakeholders, a significant impact to the community, and pushes the limits of construction experience. Risk assessment in megaproject is the most difficult component in the risk management process. Although it has high relevance to the success of megaprojects, risk management remains one of the least developed research issues. Megaprojects are executed in a dynamic environment and identified risks are to be prioritised based on their impact on project objectives of time cost and quality before they can be modelled .The present paper focuses on prioritising the technical risks associated with the construction of phase 1of Bangalore Metro Rail Project to assess its impact on the project objectives that helps in the decision support system of the project.

Stewart Clegg , Julien Pollack

Megaprojects are complex achievements of organization, sensemaking and management of power relations. Typically, engineering practice stresses rationality and linearity, exemplified in the nineteenth century roots of modern management in writers such as Taylor or Fayol. A concern with contingency theory and the emergence of project management standards hardly changed these auspices. The emergent focus on soft systems theory and a more recent interest in the practice turn did begin to change megaproject management representations somewhat. In practice, megaprojects are occasions for much complex sensemaking, as Weick defines the concept. In turn, where there are different interests in different sensemaking, then power practices and relations need to be brought into focus. The chapter does this through discussing a number of studies in which these issues have been the focus.

Joshua Banda

Evgeny Chavanin

The phenomenon known as the “megaproject paradox”, a situation in which the project fails to meet its cost, schedule and quality targets, has been given an unprecedented attention in the research literature and is currently on the rise, as the governments tighten budgets and cut public spending. The cost study by Flyvbjerg et al. (2002) analyzed 258 transport projects from 20 nations across 5 continents and discovered that 9 out of 10 projects had budget overrun, with an average budget escalation of 28%. Furthermore, the overrun appeared to be constant over a 70-year time span. This problem is not uncommon for other industries. Recent study of 5,400 large IT projects estimated an average budget overrun at 45%, with 7% overtime and 56% drop in deliverable value (M. Bloch, Sven Blumberg, Jurgen Laartz, 2012). The authors also found out that the longer the project is scheduled to last, the more likely it is to run over time and budget. Thus, every additional year spent on the project increases cost overruns by 15% (M. Bloch, Sven Blumberg, Jurgen Laartz, 2012). Another study of IT projects by US Army found that 47% were delivered to the customer but not used; 29% were paid for but not delivered; 19% were abandoned or reworked; 3% were used with minor changes; and only 2% were used as delivered (Williams & Samset, 2010). The cited study of PricewaterhouseCoopers finds out that only 2.5% of large capital projects in the world’s mining industry had been successful (Motta et al. 2014). In oil and gas industry 30-40% of the projects overrun their costs by at least 10% (Mckenna, Vanderschee & Wilczynski, 2011).

Oluwole (Alfred) Olatunji , Olugbenga Olaniran

Cost overruns are a persistent problem in oil and gas megaprojects. Whilst the extant literature is filled with studies on incidents and causes of cost overruns, underlying theories to explain their emergence in oil and gas megaprojects are few. Yet, a way to contain the syndrome of cost overruns is to understand the bases of ‘how and why’ they occur. Such knowledge will also help to develop pragmatic techniques for better overall management of oil and gas megaprojects. The aim of this paper is to explain the development of cost overruns in hydrocarbon megaprojects through the perspective of chaos theory. The underlying principles of chaos theory and its implications for cost overruns are examined and practical is proposed. In addition, directions for future research in this fertile area provided.

RELATED PAPERS

Migracijske I Etnicke Teme

Sanja Lazanin

Indian Journal of Pure and Applied Physics

Prakash Narasimha

Zbigniew Matuszak

SCHOOL EDUCATION JOURNAL PGSD FIP UNIMED

holmes parhusip

Nanotechnology

Jorgelina Ines Brochier

Journal of Happiness Studies

Juliana Pacico

Revista do GEL

Roana Rodrigues

balaram khadka

pier paolo rossi

Henrik Aronsson

Jurnal Berkala Epidemiologi

Revista de Estudios Sociales

Andreas Feldmann

Brazilian Journal of Animal and Environmental Research

Edison Martins

The Holocene

Cornelis van Leeuwen

L'Essenza dell'Essere - Suvutu

Claudio Antonini

Irma Gotera

Natália Rezende Oliveira

Anais do XX Congresso Brasileiro de Engenharia Química

Weber Robazza

Nur Sayekti

rtytrewer htytrer

Optics Express

Claude Paré

Andres Roussos

Albena Ivanova

Meidias Abror Wicaksono

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

404 Not found

How to Write a Review Article

Cite this chapter.

3295 Accesses

- Eating Disorder

- Journal Editor

- Preventive Service Task

- Borderline Personality Disorder

- Medical Writing

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Day RA. How to publish a scientific paper. 5th ed. Westport, CT: Oryx; 1998:163.

Google Scholar

Siwek J, Gourlay ML, Slawson DC, Shaughnessy AF. How to write an evidence-based clinical review article. Am Fam Phys 2002;65:251–258.

Journal of the American Medical Association. Instructions for authors. JAMA 2004;291:125–131. Available at: http://jama. ama-assn.org/ifora_current/dtl.

Harris RP, Helfand M, Wolff SH, et al. Methods Work Group, Third U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Current methods of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. A review of the process. Am J Prev Med 2001;20(3 suppl):21–35.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ebell MH, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. Am Fam Phys 2004;69:548–556.

Download references

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2005 Springer Science+Business Media, Inc.

About this chapter

(2005). How to Write a Review Article. In: The Clinician’s Guide to Medical Writing. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-27024-8_6

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-27024-8_6

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-0-387-22249-3

Online ISBN : 978-0-387-27024-1

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Help | Advanced Search

Computer Science > Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition

Title: a comprehensive review of knowledge distillation in computer vision.

Abstract: Deep learning techniques have been demonstrated to surpass preceding cutting-edge machine learning techniques in recent years, with computer vision being one of the most prominent examples. However, deep learning models suffer from significant drawbacks when deployed in resource-constrained environments due to their large model size and high complexity. Knowledge Distillation is one of the prominent solutions to overcome this challenge. This review paper examines the current state of research on knowledge distillation, a technique for compressing complex models into smaller and simpler ones. The paper provides an overview of the major principles and techniques associated with knowledge distillation and reviews the applications of knowledge distillation in the domain of computer vision. The review focuses on the benefits of knowledge distillation, as well as the problems that must be overcome to improve its effectiveness.

Submission history

Access paper:.

- Other Formats

References & Citations

- Google Scholar

- Semantic Scholar

BibTeX formatted citation

Bibliographic and Citation Tools

Code, data and media associated with this article, recommenders and search tools.

- Institution

arXivLabs: experimental projects with community collaborators

arXivLabs is a framework that allows collaborators to develop and share new arXiv features directly on our website.

Both individuals and organizations that work with arXivLabs have embraced and accepted our values of openness, community, excellence, and user data privacy. arXiv is committed to these values and only works with partners that adhere to them.

Have an idea for a project that will add value for arXiv's community? Learn more about arXivLabs .

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- BOOK REVIEW

- 29 March 2024

The great rewiring: is social media really behind an epidemic of teenage mental illness?

- Candice L. Odgers 0

Candice L. Odgers is the associate dean for research and a professor of psychological science and informatics at the University of California, Irvine. She also co-leads international networks on child development for both the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research in Toronto and the Jacobs Foundation based in Zurich, Switzerland.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Social-media platforms aren’t always social. Credit: Getty

The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness Jonathan Haidt Allen Lane (2024)

Two things need to be said after reading The Anxious Generation . First, this book is going to sell a lot of copies, because Jonathan Haidt is telling a scary story about children’s development that many parents are primed to believe. Second, the book’s repeated suggestion that digital technologies are rewiring our children’s brains and causing an epidemic of mental illness is not supported by science. Worse, the bold proposal that social media is to blame might distract us from effectively responding to the real causes of the current mental-health crisis in young people.

Haidt asserts that the great rewiring of children’s brains has taken place by “designing a firehose of addictive content that entered through kids’ eyes and ears”. And that “by displacing physical play and in-person socializing, these companies have rewired childhood and changed human development on an almost unimaginable scale”. Such serious claims require serious evidence.

Collection: Promoting youth mental health

Haidt supplies graphs throughout the book showing that digital-technology use and adolescent mental-health problems are rising together. On the first day of the graduate statistics class I teach, I draw similar lines on a board that seem to connect two disparate phenomena, and ask the students what they think is happening. Within minutes, the students usually begin telling elaborate stories about how the two phenomena are related, even describing how one could cause the other. The plots presented throughout this book will be useful in teaching my students the fundamentals of causal inference, and how to avoid making up stories by simply looking at trend lines.

Hundreds of researchers, myself included, have searched for the kind of large effects suggested by Haidt. Our efforts have produced a mix of no, small and mixed associations. Most data are correlative. When associations over time are found, they suggest not that social-media use predicts or causes depression, but that young people who already have mental-health problems use such platforms more often or in different ways from their healthy peers 1 .

These are not just our data or my opinion. Several meta-analyses and systematic reviews converge on the same message 2 – 5 . An analysis done in 72 countries shows no consistent or measurable associations between well-being and the roll-out of social media globally 6 . Moreover, findings from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development study, the largest long-term study of adolescent brain development in the United States, has found no evidence of drastic changes associated with digital-technology use 7 . Haidt, a social psychologist at New York University, is a gifted storyteller, but his tale is currently one searching for evidence.

Of course, our current understanding is incomplete, and more research is always needed. As a psychologist who has studied children’s and adolescents’ mental health for the past 20 years and tracked their well-being and digital-technology use, I appreciate the frustration and desire for simple answers. As a parent of adolescents, I would also like to identify a simple source for the sadness and pain that this generation is reporting.

A complex problem

There are, unfortunately, no simple answers. The onset and development of mental disorders, such as anxiety and depression, are driven by a complex set of genetic and environmental factors. Suicide rates among people in most age groups have been increasing steadily for the past 20 years in the United States. Researchers cite access to guns, exposure to violence, structural discrimination and racism, sexism and sexual abuse, the opioid epidemic, economic hardship and social isolation as leading contributors 8 .

How social media affects teen mental health: a missing link

The current generation of adolescents was raised in the aftermath of the great recession of 2008. Haidt suggests that the resulting deprivation cannot be a factor, because unemployment has gone down. But analyses of the differential impacts of economic shocks have shown that families in the bottom 20% of the income distribution continue to experience harm 9 . In the United States, close to one in six children live below the poverty line while also growing up at the time of an opioid crisis, school shootings and increasing unrest because of racial and sexual discrimination and violence.

The good news is that more young people are talking openly about their symptoms and mental-health struggles than ever before. The bad news is that insufficient services are available to address their needs. In the United States, there is, on average, one school psychologist for every 1,119 students 10 .

Haidt’s work on emotion, culture and morality has been influential; and, in fairness, he admits that he is no specialist in clinical psychology, child development or media studies. In previous books, he has used the analogy of an elephant and its rider to argue how our gut reactions (the elephant) can drag along our rational minds (the rider). Subsequent research has shown how easy it is to pick out evidence to support our initial gut reactions to an issue. That we should question assumptions that we think are true carefully is a lesson from Haidt’s own work. Everyone used to ‘know’ that the world was flat. The falsification of previous assumptions by testing them against data can prevent us from being the rider dragged along by the elephant.

A generation in crisis

Two things can be independently true about social media. First, that there is no evidence that using these platforms is rewiring children’s brains or driving an epidemic of mental illness. Second, that considerable reforms to these platforms are required, given how much time young people spend on them. Many of Haidt’s solutions for parents, adolescents, educators and big technology firms are reasonable, including stricter content-moderation policies and requiring companies to take user age into account when designing platforms and algorithms. Others, such as age-based restrictions and bans on mobile devices, are unlikely to be effective in practice — or worse, could backfire given what we know about adolescent behaviour.

A third truth is that we have a generation in crisis and in desperate need of the best of what science and evidence-based solutions can offer. Unfortunately, our time is being spent telling stories that are unsupported by research and that do little to support young people who need, and deserve, more.

Nature 628 , 29-30 (2024)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-00902-2

Heffer, T., Good, M., Daly, O., MacDonell, E. & Willoughby, T. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 7 , 462–470 (2019).

Article Google Scholar

Hancock, J., Liu, S. X., Luo, M. & Mieczkowski, H. Preprint at SSRN https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4053961 (2022).

Odgers, C. L. & Jensen, M. R. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 61 , 336–348 (2020).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Orben, A. Soc . Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 55 , 407–414 (2020).

Valkenburg, P. M., Meier, A. & Beyens, I. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 44 , 58–68 (2022).

Vuorre, M. & Przybylski, A. K. R. Sci. Open Sci. 10 , 221451 (2023).

Miller, J., Mills, K. L., Vuorre, M., Orben, A. & Przybylski, A. K. Cortex 169 , 290–308 (2023).

Martínez-Alés, G., Jiang, T., Keyes, K. M. & Gradus, J. L. Annu. Rev. Publ. Health 43 , 99–116 (2022).

Danziger, S. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 650 , 6–24 (2013).

US Department of Education. State Nonfiscal Public Elementary/Secondary Education Survey 2022–2023 (National Center for Education Statistics, 2024).

Google Scholar

Download references

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Related Articles

- Public health

Why loneliness is bad for your health

News Feature 03 APR 24

Adopt universal standards for study adaptation to boost health, education and social-science research

Correspondence 02 APR 24

Allow researchers with caring responsibilities ‘promotion pauses’ to make research more equitable

Circulating myeloid-derived MMP8 in stress susceptibility and depression

Article 07 FEB 24

Only 0.5% of neuroscience studies look at women’s health. Here’s how to change that

World View 21 NOV 23

Sustained antidepressant effect of ketamine through NMDAR trapping in the LHb

Article 18 OCT 23

Abortion-pill challenge provokes doubt from US Supreme Court

News 26 MAR 24

The future of at-home molecular testing

Outlook 21 MAR 24

POSTDOCTORAL Fellow -- DEPARTMENT OF Surgery – BIDMC, Harvard Medical School

The Division of Urologic Surgery in the Department of Surgery at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School invites applicatio...

Boston, Massachusetts (US)

Director of Research

Applications are invited for the post of Director of Research at Cancer Institute (WIA), Chennai, India.

Chennai, Tamil Nadu (IN)

Cancer Institute (W.I.A)

Postdoctoral Fellow in Human Immunology (wet lab)

Join Atomic Lab in Boston as a postdoc in human immunology for universal flu vaccine project. Expertise in cytometry, cell sorting, scRNAseq.

Boston University Atomic Lab

Research Associate - Neuroscience and Respiratory Physiology

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Histology Laboratory Manager

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Open access

- Published: 01 April 2024

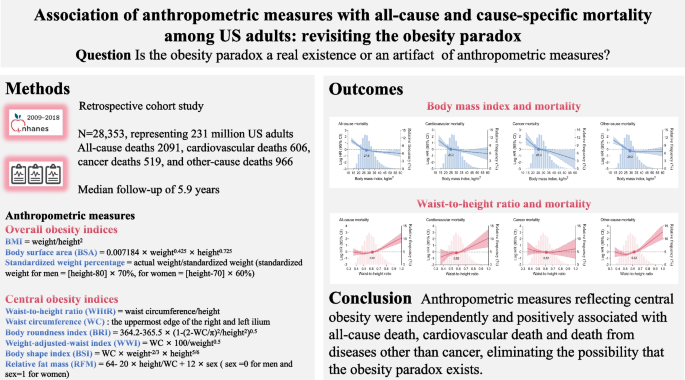

Association of anthropometric measures with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in US adults: revisiting the obesity paradox

- Shan Li 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Zhiqing Fu 1 , 2 na1 &

- Wei Zhang 2 , 3

BMC Public Health volume 24 , Article number: 929 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

367 Accesses

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

Previous studies have shown that the obesity paradox exists in a variety of clinical settings, whereby obese individuals have lower mortality than their normal-weight counterparts. It remains unclear whether the association between obesity and mortality risk varies by anthropometric measures. The purpose of this study is to examine the association between various anthropometric measures and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in US adults.

This cohort study included data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey between 2009 and 2018, with a sample size of 28,353 individuals weighted to represent 231 million US adults. Anthropometric measurements were obtained by trained technicians using standardized methods. Mortality data were collected from the date of enrollment through December 31, 2019. Weighted Cox proportional hazards models, restricted cubic spline curves, and cumulative incidence analyses were performed.

A total of 2091 all-cause deaths, 606 cardiovascular deaths, 519 cancer deaths, and 966 other-cause deaths occurred during a median follow-up of 5.9 years. The association between body mass index (BMI) and mortality risk was inversely J-shaped, whereas the association between waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) and mortality risk was positively J-shaped. There was a progressive increase in the association between the WHtR category and mortality risk. Compared with the reference category of WHtR < 0.5, the estimated hazard ratio (HR) for all-cause mortality was 1.004 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.001–1.006) for WHtR 0.50–0.59, 1.123 (95% CI 1.120–1.127) for WHtR 0.60–0.69, 1.591 (95% CI 1.584–1.598) for WHtR 0.70–0.79, and 2.214 (95% CI 2.200–2.228) for WHtR ≥ 0.8, respectively. Other anthropometric indices reflecting central obesity also showed that greater adiposity was associated with higher mortality.

Conclusions

Anthropometric measures reflecting central obesity were independently and positively associated with mortality risk, eliminating the possibility of an obesity paradox.

Graphical Abstract

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Obesity is a growing public health concern, with the global prevalence predicted to reach 14% in men and 20% in women by 2030 [ 1 ]. In the United States, the prevalence of obesity will be as high as 47% in both men and women by that time [ 1 ]. The etiology of obesity is multifactorial and includes biology, genetics, socioeconomics, environmental factors, and access to healthcare resources [ 2 ]. Strong evidence suggests that obesity has deleterious effects on glucolipid homeostasis, blood pressure, systemic inflammation, and oxidative stress, thereby increasing the risk of various pathophysiological conditions such as diabetes, atherosclerosis, hypertension, musculoskeletal disorders, and certain cancers, as well as predisposing to premature death [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. However, the existing literature reports that obese individuals have better survival than their normal-weight counterparts in a variety of clinical settings, a phenomenon known as the obesity-survival paradox [ 8 , 9 , 10 ]. This counterintuitive relationship may make it difficult to clarify the link between obesity and metabolic pathology and may send confusing messages to healthcare professionals and policymakers, potentially leading to hesitancy in controlling weight and adopting healthy lifestyles.

Several assessment tools have been used clinically to define excess body fat, including anthropometric, bioelectrical impedance analysis, densitometric and imaging-based methods [ 2 ]. Body mass index (BMI) is the most used anthropometric measure reflecting overall obesity. The obesity-survival paradox is typically documented using BMI as an evaluative indicator [ 8 , 10 , 11 ]. Epidemiological and genetic evidence suggests that the systemic metabolic risks of obesity depend not only on the amount of fat, but also on its distribution, and that central obesity, mainly the accumulation of abdominal or visceral fat, contributes to major cardiometabolic abnormalities and total mortality [ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ]. However, BMI has inherent limitations in defining adiposity because it can differentiate neither body compositions nor regional fat distribution, which weakens its credibility in predicting obesity-related metabolic risks and leads to heterogeneity or even conflicting epidemiologic relevance. Consequently, other anthropometric indices have been developed, including waist circumference, waist-to-height ratio (WHtR), waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), and body composition measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), which may be better surrogates for reflecting central obesity. However, the available evidence on the association between central obesity indices and mortality risk is not sufficient, so it remains unclear whether the obesity paradox reflected by BMI is a real existence or an artifact of anthropometric measures. It is of concern that the persistence of conflicting findings on the relationship between obesity and survival may misinterpret the considerable efforts toward weight control.

Therefore, we conducted this study in US adults from the 2009–2018 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The objectives of this study were to (i) examine the association of BMI and WHtR with all-cause and cause-specific mortality, using them as proxies for overall obesity and central obesity, respectively, (ii) characterize the association of other anthropometric indices reflecting overall obesity or central obesity with mortality risk, and (iii) attempt to explore the possible reasons for the discrepancy between anthropometric measures and the outcomes according to the correlation between anthropometric indices and DXA-based visceral fat measurements. We hypothesize that the obesity paradox may not be real but an artifact of anthropometric measures.

Study population

NHANES is a historical, nationally representative survey of the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. The survey uses a multistage stratified probability cluster sampling design and incorporates participant weights to ensure accuracy in reflecting the demographics of the U.S. Census during the same time period [ 16 ]. We extracted data from five consecutive cycles of the NHANES database (2009–2010, 2011–2012, 2013–2014, 2015–2016, and 2017–2018). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All adult participants provided written informed consent, and all NHANES protocols were approved by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Ethics Review Board [ 17 ]. Of the 49,693 adults who participated in the 5 NHANES cycles, 21,340 were excluded because they were younger than 18 years ( n = 19,341), pregnant ( n = 247), had missing weight or height data ( n = 1,596), had a BMI less than 10 kg/m 2 or greater than 60 kg/m 2 ( n = 73), and had missing follow-up information ( n = 83). Finally, 28,353 individuals were included in the analysis (Supplementary material Figure S 1 ).

Anthropometric measures

Participants wore disposable examination gowns and baseline weight, height and waist circumference were measured by trained health technicians to ensure methodological consistency. Waist circumference was measured at the uppermost edge of the right and left ilium, and waist circumference data were available for 26,998 individuals. The following anthropometric measures were examined, including overall obesity indices (BMI, body surface area [BSA], and standardized weight percentage) and central obesity indices (WHtR, waist circumference, body roundness index [BRI], weight-adjusted-waist index [WWI], relative fat mass [RFM], and body shape index [BSI]). The overall obesity indices were calculated based on weight and height, while the central obesity indices were calculated based on waist circumference and height (see Graphical abstract). According to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, individuals were divided into five BMI categories: underweight, < 18.5 kg/m 2 ; normal weight, 18.5–24.9 kg/m 2 ; overweight, 25–29.9 kg/m 2 ; class I obesity, 30–34.9 kg/m 2 ; and class II or III obesity, ≥ 35 kg/m 2 . For analyses using the WHtR, individuals were categorized as follows: < 0.50, 0.50–0.59, 0.60–0.69, 0.70–0.79, ≥ 0.80, with WHtR < 0.5 being the normal range. DXA-based visceral adipose tissue (VAT) measurements were available for 12,792 individuals, and VAT area and mass were measured at the L4 and L5 intervertebral spaces.

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality, and the secondary outcomes were cardiovascular mortality, cancer mortality and other-cause mortality. Mortality data from the date of enrollment through December 31, 2019 were obtained by linking the NHANES dataset to death certificate records from the National Death Index (NDI) provided by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) [ 18 ]. Cause-specific mortality was defined based on the recorded NCHS underlying classification of death (UCOD). Cardiovascular deaths were defined as deaths from heart disease and deaths from cerebrovascular disease. Cancer deaths were defined as deaths due to malignant neoplasms.

A wide range of covariates were considered, including age, sex, ethnicity, education, marital status, poverty income ratio, smoking status, alcohol consumption, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, BMI (for WHtR analyses) or waist circumference (for BMI analyses), atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cancer, aspirin, lipid-lowering drugs, hypoglycemic agents, and laboratory measurements (white blood cell count, hemoglobin, albumin, creatinine, urea nitrogen, glycohemoglobin, total cholesterol, and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C]). Demographic and health information was collected by experienced interviewers using a computer-assisted personal interview (CAPI) system and reviewed for completeness, consistency, and logicality to ensure data quality. Physical examinations were performed at a dedicated mobile examination center (MEC) using a uniform methodology and laboratory measurements were performed using the Beckman Coulter DxH 800 instrument for complete blood counts, and the Roche Cobas 6000 (c501 module) analyzer for standard biochemistry indices.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.0) and EmpowerStats (X&Y Solutions, Inc., Boston, MA). Statistical significance was defined as a 2-tailed p-value < 0.05. Sample weights, stratification, and clustering were incorporated in all analyses to account for unequal selection and nonresponse probabilities. Baseline characteristics were expressed as means with standard deviations (SDs), medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs), or numbers with percentages and were compared by one-way analysis of variance, Kruskal–Wallis test, and chi-squared test. Data on covariates were more than 93% complete (Supplementary material Table S 1 ). Missing values were imputed using chained equation multiple imputation ( n = 5 data sets).

Restricted cubic spline curves based on Cox models were used to visualize the continuous association between BMI or WHtR and mortality. The inflection points of the mortality risk were estimated and the effect sizes before and after which were reported. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of all-cause and cause-specific mortality for categorical and continuous WHtR. Proportional hazard assumptions were tested and confirmed by Schoenfeld's residual estimates and log(time) plots. Cumulative all-cause mortality for the BMI and WHtR groups was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method, with the interval from the date of examination to the date of death or the end of follow-up as the time scale. Fine and Gray competing risk models were used for cause-specific mortality, with deaths from the two remaining causes as competing outcomes. The associations between other anthropometric indices and mortality were also visualized using restricted cubic spline curves. Linear regression fitting and Pearson's correlation coefficient were used to test the correlation between anthropometric indices and VAT measurements.

Sensitivity analyses were performed. First, we examined the association between other anthropometric indices (BSA, standardized weight percentage, waist circumference, BRI, WWI, RFM and BSI) as continuous variables and outcomes using the COX proportional hazards models. Second, we performed stratified analyses with subgroups of interest, including age, sex, ethnicity, and presence of diabetes mellitus. Third, individuals with less than 1 year of follow-up were excluded to minimize the potential bias for reverse causality. Fourth, complete case analyses were performed using only complete data for all covariates to assess whether missing data distorted the current results.

The sample included 28,353 individuals from the 2009–2018 NHANES data sets, weighted to represent 231 million US adults. During a median follow-up of 5.9 years, 2091 (7.4%) all-cause deaths, 606 (2.2%) cardiovascular deaths, 519 (1.8%) cancer deaths, and 966 (3.4%) other-cause deaths were recorded, respectively. BMI, BSA and standardized weight percentage were available for all individuals. Waist circumference was available for 95.2% of individuals, as were WHtR, BRI, WWI, RFM, and BSI. Of the total population, 32.1% were classified as overweight and 37.8% as obese, with a mean BMI of 29.0 (SD 6.8) kg/m 2 , while 83.0% had a WHtR outside the normal range of < 0.5, with a mean WHtR of 0.6 (SD 0.1). Individuals with higher BMI or WHtR were older, more likely to be non-Hispanic blacks, less likely to be current smokers, had a higher prevalence of ASCVD and diabetes mellitus, and had higher white blood cell and lower HDL-C levels. All-cause mortality increased progressively with increasing WHtR, while the opposite was present for BMI (Table 1 and Supplementary material Table S 2 ).

Association between BMI or WHtR and mortality

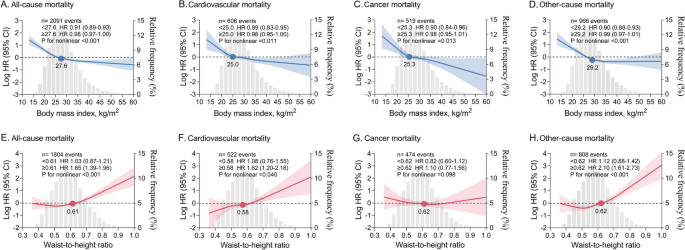

In restricted cubic spline analyses, there was an inversely J-shaped association between continuous BMI and mortality, with risk inflection points for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, cancer mortality, and other-cause mortality at BMIs of 27.6, 25.0, 25.3, and 29.2 kg/m 2 , respectively. The risk of death decreased sharply before the inflection point and remained almost constant thereafter. Conversely, there was a positively J-shaped association between continuous WHtR and mortality, with risk inflection points for all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and other-cause mortality occurring at WHtRs of 0.61, 0.58, and 0.62, respectively. The risk of death remained stable until the inflection point and then increased sharply and significantly. No significant association was found between WHtR and cancer death (Fig. 1 ). In Cox proportional hazards analyses, there was a gradual increase in the association between the WHtR category and all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and other-cause mortality. In addition, when WHtR was examined as a continuous variable, each 0.1 increase in WHtR was associated with a 36.8%, 43.7%, and 47.6% increase in all-cause, cardiovascular, and other-cause mortality, respectively (Table 2 ).

Nonlinear association between continuous BMI or WHtR and mortality. A-D BMI and mortality. E – H WHtR and mortality. HRs (solid lines) and 95% CIs (shaded areas) are based on weighted restricted cubic splines. The gray areas in the background show the distributions (histograms) of BMI or WHtR in the population. Solid dots represent risk inflection points for nonlinear associations. Effect size for per unit change in BMI (1 kg/m 2 ) and WHtR (0.1) before and after the inflection point are shown separately. Models were adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, waist circumference (for BMI analysis) or BMI (for WHtR analysis), education level, marital status, poverty income ratio, smoking status, alcohol consumption, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, ASCVD, diabetes mellitus, COPD, cancer, aspirin, lipid-lowering drugs, hypoglycemic agents, and laboratory measurements (white blood cell count, hemoglobin, albumin, creatinine, urea nitrogen, glycohemoglobin, total cholesterol, and HDL-C). ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. HR, hazard ratio. CI, confidence interval

Cumulative mortality according to BMI or WHtR groups

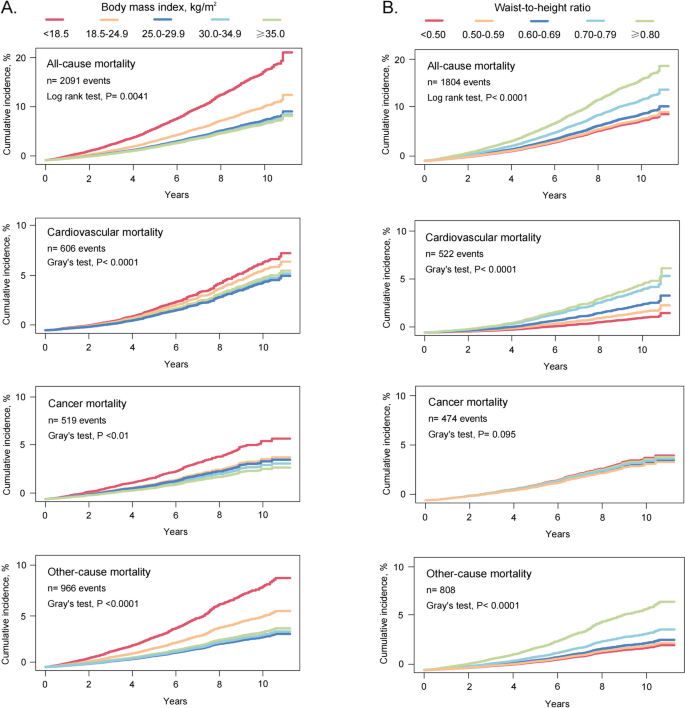

The cumulative mortality curve showed a gradual decrease in mortality among groups with higher BMI. Specifically, the underweight group had the highest mortality, followed by the normal weight group, while the groups with overweight and obesity had the lowest mortality. Cumulative morbidity for WHtR showed the opposite pattern. Cumulative all-cause, cardiovascular, and other-cause deaths progressively increased in groups with incrementally higher WHtR, whereas there was no evidence that higher WHtR was associated with higher cumulative cancer mortality (Fig. 2 ).

Cumulative mortality by BMI or WHtR groups. Cumulative incidence for mortality was estimated according to ( A ) BMI and ( B ) WHtR groups, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality was followed up to December 31, 2019. The Fine and Gray competing risk models were used for cause-specific mortality, with deaths from the remaining two causes as competing risks

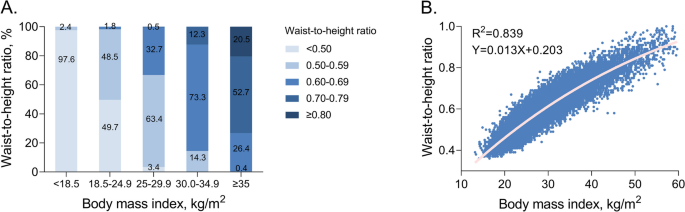

The concordance between BMI and WHtR

Although a strong correlation between BMI and WHtR was observed ( r 2 = 0.839), there were significant differences in agreement between subcategories. Specifically, 97.6% (489 out of 501) of underweight individuals had WHtRs within the normal range, whereas less than half of normal-weight individuals (49.7%, 3807 out of 7653) had WHtRs < 0.5, with the remaining half having WHtRs between 0.5 and 0.7. The concordance between BMI and WHtR was quite high among overweight and obese individuals, most of whom had WHtRs above the normal range (Fig. 3 ).

Correlation between BMI and WHtR categories. A WHtR percentage across BMI categories. B Correlation between BMI and WHtR categories

Correlation between anthropometric indices and VAT measurements

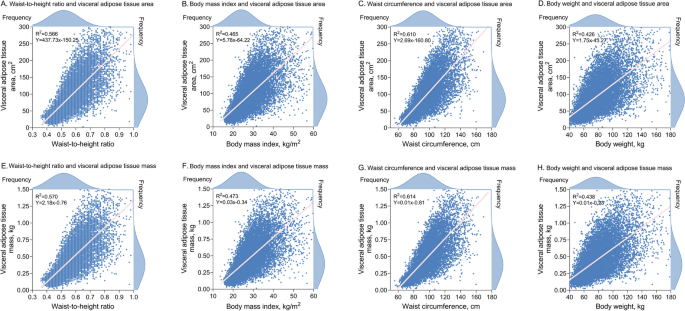

In addition to BMI and WHtR, we also examined the correlation of body weight and waist circumference with VAT, as the latter two are the basis for calculating the overall and central obesity indices, respectively. Overall, Pearson's correlations between anthropometric indices and VAT measures were modest. However, the correlations between VAT measures and WHtR or waist circumference were stronger than those with BMI or body weight, ranging from r 2 = 0.566–0.614 for WHtR and waist circumference to r 2 = 0.426–0.473 for BMI and body weight (Fig. 4 ).

Correlation between anthropometric indices and visceral adipose tissue measurements Pink lines show linear regressions of anthropometric indices on visceral adipose area ( A - D ) and linear regressions of anthropometric indices on visceral adipose mass ( E – H )

Other anthropometric indices and mortality

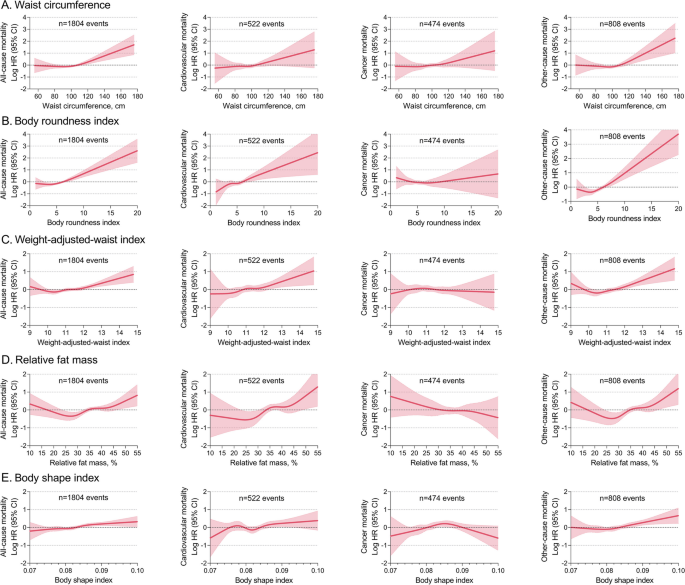

Other central obesity indices (waist circumference, BRI, WWI, RFM and BSI) also had positively J-shaped associations with all-cause, cardiovascular, and other-cause mortality, but no significant associations with cancer mortality (Fig. 5 ). Other overall obesity indices (BSA and standardized body weight percentage) had inversely J-shaped associations with mortality, whereas the association between BSA and cancer death did not appear to be significant (Supplementary material Figure S 2 ).

Nonlinear association between other central obesity indices and mortality HRs (solid lines) and 95% CIs (shaded areas) are based on weighted restricted cubic splines. The models were adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, BMI, education, marital status, poverty income ratio, smoking status, alcohol consumption, systolic blood pressure, heart rate, ASCVD, diabetes mellitus, COPD, cancer, aspirin, lipid-lowering drugs, hypoglycemic agents, and laboratory measurements (white blood cell count, hemoglobin, albumin, creatinine, urea nitrogen, glycohemoglobin, total cholesterol, and HDL-C). ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. HR, hazard ratio. CI, confidence interval

Sensitivity analysis

The results of the sensitivity analyses were generally consistent with those of the primary analyses. First, using the COX proportional hazards models, other central obesity indices (waist circumference, BRI, WWI, RFM and BSI) were positively associated with all-cause, cardiovascular, and other-cause mortality. In contrast, other overall obesity indices (BSA and standardized body weight percentage) were negatively associated with mortality (Supplementary material Table S 3 ). Second, in subgroups stratified by age, sex, ethnicity, and diabetes, the association pattern between continuous BMI or WHtR and mortality was consistent with the primary analysis (Supplementary material Figures S 3 -S 6 ). Third, exclusion of individuals with less than 1 year of follow-up did not substantially change the results (Supplementary material Figure S 7 ). Fourth, a complete case analysis showed that missing data did not distort the current findings (Supplementary material Figure S 8 ).

In a large nationally representative cohort of US adults, we examined the association between various anthropometric measures and all-cause and cause-specific mortality with a maximum follow-up of 11.3 years. We found that BMI and WHtR had diametrically opposite associations with mortality risk. The association between BMI and mortality was inversely J-shaped, whereas the association between WHtR and mortality was positively J-shaped. Other anthropometric indices of overall obesity also suggested a negative association between obesity and mortality, whereas none of the central obesity indices supported such a counterintuitive relationship. The current findings suggest that the obesity paradox may be an artifact of anthropometric measures, and that central obesity indices were independently and positively associated with all-cause death, cardiovascular death, and death from diseases other than cancer, eliminating the possibility that the obesity paradox exists.

The obesity-survival paradox has been previously reported in studies of critically ill patients, the elderly, and the general population [8-10]. A meta-analysis involving 218,532 patients with cardiovascular disease also demonstrated that total mortality was lower in overweight and obese patients than in normal weight patients, with a hazard ratio of approximately 0.70 [ 19 ]. Using BMI as an anthropometric indicator, we replicated this counterintuitive association through an inversely J-shaped pattern, whereby the risk of death decreased gradually within the initial units of BMI and then reached a plateau. All the nadirs of mortality risk were in the overweight range, lending further credence that a higher BMI may be protective for survival. In addition, when other indices of overall obesity were examined, the results were similar to those of the BMI, suggesting that overall obesity indices derived from weight-based calculations are consistent in estimating mortality risk.

Previous findings on the association between central obesity indices and adverse outcomes have been heterogeneous, with some studies reporting J-shaped or monotonic positive associations and others showing negative or null associations [ 20 , 21 , 22 , 22 ]. Methodologically, some of these studies did not address the hard endpoint of mortality, some focused on all-cause mortality and lacked data on cause-specific mortality, and some analyzed only a single anthropometric index. Our results provide evidence on these unaddressed issues. We found a positively J-shaped association between WHtR and all-cause, cardiovascular, and other-cause mortality, independent of BMI. The risk inflection point occurred around a WHtR of 0.6, slightly above the currently recommended threshold of 0.5, with slight change in the risk of death until the inflection point, followed by a sharp and linear increase. This positive association pattern was consistently observed for other anthropometric indices of central obesity, including waist circumference, BRI, WWI, RFM and BSI, albeit slightly attenuated for RFM and BSI. The current findings are in accordance with those of several recent large studies revealing an independent positive association between central obesity indices and adverse outcomes (e.g., premature mortality, heart failure hospitalization, cardiometabolic risk), some of which used a Mendelian randomized design to infer causality [ 23 , 24 , 25 ]. We did not find a substantial association between WHtR and cancer mortality. The association between obesity and cancer incidence and mortality varies by cancer site. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has reported seven cancers for which there is compelling evidence of a dose–response relationship with obesity, including cancers of esophagus, colorectum, pancreas, cardia, liver, gallbladder, and kidney [ 26 ]. However, the three most common cancers in the current cohort were breast (15.4%), prostate (15.3%), and skin cancers (14.8%), which accounted for nearly half of individuals with cancers. This may explain our inability to find a clear association between obesity and cancer death in this nationally representative population.

The divergent association pattern may be due to differences in population-level risk classification using different anthropometric measures. In the present study, despite a strong linear correlation between BMI and WHtR, the consideration of WHtR resulted in a significant reclassification of individuals with normal weight. Only half of the normal weight individuals fell within the normal range of WHtR, suggesting that the pathophysiological milieu of the remaining half may be overlooked. There was less misclassification of overweight or obese individuals, with 98% having a WHtR greater than 0.5. A minority of overweight or obese individuals have a normal WHtR, which may be due to increased muscle mass rather than fat accumulation. These individuals, known as metabolically healthy obese (MHO), have been previously documented [ 27 ]. Our findings suggest that BMI is not sufficient to identify the high-risk phenotype for central obesity as defined by the WHtR, especially in those with normal weight (underestimation of risk). Previous evidence has also shown that high-risk characteristics for central obesity include a higher ratio of visceral-to-subcutaneous adipose tissue, a larger waist circumference, and a higher ratio of waist circumference to hip or leg circumference [ 28 ], which can be captured by central obesity indices rather than BMI alone.

Epidemiological and genetic evidence has shown that the regional distribution of fat may be more important than its absolute mass in predicting obesity-related metabolic risk [ 14 , 25 , 29 ]. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allow accurate quantification of the body compositions at each level, thereby identifying subcutaneous adipose tissue (e.g., gluteal and thigh fat) and VAT (e.g., intra-abdominal and ectopic fat) [ 30 , 31 ]. However, CT involves ionizing radiation and MRI is time consuming, both are expensive and require specially trained personnel to perform. DXA serves as a viable alternative with low radiation exposure and low cost, and has been validated by CT and MRI in identifying the high-risk metabolic phenotype [ 32 , 33 ]. We found moderate correlations between anthropometric indices and VAT measurements based on DXA, it is in line with the expectation that an anthropometric indicator that can only make a rough estimate of fat distribution. Specifically, WHtR and waist circumference had stronger correlations with VAT measurements than BMI, whereas body weight had the weakest correlation, and the correlation coefficients were in agreement with previous studies [ 32 ]. Mechanistically, subcutaneous adipose tissue plays a critical role in energy storage and thermoregulation, and when its storage capacity is saturated, adipotoxic VAT deposition occurs. VAT exerts adipocyte biological effects through increased secretion of pro-inflammatory adipokines and decreased secretion of anti-inflammatory adipocytokines [ 2 , 34 ]. Consequently, VAT creates an atherogenic, diabetogenic, and inflammatory milieu leading to downstream metabolic dysregulation and cardiovascular damage [ 35 ]. Because routine measurement of VAT may be impractical, the use of alternative anthropometric indicators as simple estimates in clinical practice is promising. The stronger correlation between WHtR and VAT measurements compared to BMI may partly explain why WHtR provides a better estimate for adverse outcomes.

The growing obesity epidemic is associated with substantial mortality, morbidity, and health care expenditures. Therefore, obesity has been included in the global targets for the control of non-communicable diseases (NCD) [ 36 ]. Based on current research, we have several considerations. First, it is imperative to implement comprehensive and effective prevention strategies that focus on promoting healthy lifestyles and controlling excessive weight gain. However, the existence of the obesity-survival paradox may cause confusion and hesitation among the public and policy makers. Our findings suggest that the obesity paradox may be an artifact of anthropometric measures rather than an actual biological advantage of excess fat storage, which dispels concerns that being overweight or obese improves survival over being normal weight. Second, susceptibility to obesity-related metabolic risk may be mediated by visceral fat, and anthropometric measures of central obesity provide independent and additive information beyond BMI in characterizing adverse risk. A growing number of obesity professional societies have recommended that central obesity indices (waist circumference or WHtR) should be routinely used alongside BMI for the stratification and management of obesity [ 15 , 37 ]. Third, accurate assessment of obesity requires consideration of the validity, feasibility, and standardization of assessment indicators. Measuring waist circumference alone is inadequate because it does not consider the effect of height, which is significantly and inversely associated with health risks such as cardiovascular disease and cancer [ 38 , 39 ]. Waist-hip ratio is a valid indicator for considering both VAT and lower-body subcutaneous adipose tissue. However, hip circumference is less readily available, making waist-to-hip ratio less practical. The WHtR corrects waist circumference by height, normalizing the threshold to 0.5, regardless of gender, age, and ethnicity. This simplifies the health message to the notion that waist circumference should not exceed half of one's height, offering a more feasible and pragmatic measure for both health professionals and the general population. Finally, further research should focus on whether the adoption of these anthropometric metrics can meaningfully enhance risk prediction algorithms beyond traditional measurements, and whether these anthropometric indicators can serve as valid targets for risk reduction.

Strengths and limitations