Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 06 March 2024

The association between physical activity, self-efficacy, stress self-management and mental health among adolescents

- Ge Zhang 1 ,

- Wanxuan Feng 1 ,

- Liangyu Zhao 1 ,

- Xiuhan Zhao 1 &

- Tuojian Li 1

Scientific Reports volume 14 , Article number: 5488 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

895 Accesses

3 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Risk factors

This study aimed to explore the interplay between physical activity, self-efficacy, stress self-management and mental health among adolescents. The study gathered data from an online survey conducted among 400 Chinese middle school students (mean age = 13.74 years). The collected data were analyzed using SPSS 27.0 and PROCESS 4.1. The findings indicated a positive and significant relationship between physical activity, self-efficacy, stress self-management, and mental health. Notably, the association between physical activity and mental health was entirely mediated by self-efficacy and stress self-management. Moreover, self-efficacy and stress self-management exhibited a chain mediation effect on the relationship between physical activity and mental health. It is suggested that interventions focusing on physical activity should prioritize strategies for enhancing students’ self-efficacy and stress self-management skills as integral components of promoting adolescents’ mental health. Future research should delve into identifying specific types of physical activities that have a greater potential to enhance self-efficacy and stress self-management abilities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Mediation effect of emotional self-regulation in the relationship between physical activity and subjective well-being in Chilean adolescents

Sergio Fuentealba-Urra, Andrés Rubio, … Cristian Céspedes-Carreno

The relationship between home-based physical activity and general well-being among Chinese university students during the COVID-19 pandemic: the mediation effect of self-esteem

Mei Cao, Yongzhen Teng, … Yijin Wu

Physical activity and nutrition in relation to resilience: a cross-sectional study

Bernhard Leipold, Kristina Klier, … Annette Schmidt

Introduction

According to the WHO, 14% 10–19 year-olds experience mental health conditions, accounting for 13% of the global burden of disease in this age group. Depression, anxiety and behavioural disorders are among the leading causes of illness and disability among adolescents. By 2030, depression alone is projected to become the primary cause of disability and reduced life expectancy 1 . Adolescents are immature in physiological and psychological development and facing greater pressures in various aspects such as higher education, self and peer, are observed to be more susceptible to experiencing mental health issues 2 , 3 . Moreover, psychological challenges during adolescence can significantly influence mental health in adulthood, leading to adverse outcomes 4 . Understanding the pathways that contribute to adolescents’ stress self-management levels and mental health is crucial for implementing effective measures to prevent and alleviate serious issues like anxiety and depression.

Physical activity is recognized as a significant means to foster the holistic development of adolescents, encompassing both physical and mental health. Prior studies have indicated that engaging in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity is linked to reduced depression and anxiety 5 , 6 . Consistently participating in physical activity has been correlated with improved mental health 7 , 8 , 9 . Regular engagement in physical activity implies that adolescents develop better self-management skills and time allocation, often characterized by increased autonomy. This behavior reduces the likelihood of engaging in activities detrimental to their mental well-being, such as excessive screen time 10 . In addition, they can cope with the emergency stressors better which makes them keep more stable mental health 11 . However, a recent study discovered that adolescents engaging exclusively in individual physical activities reported higher psychological issues like anxiety and depression compared to non-participants 12 . Furthermore, a study demonstrated that individuals with high rumination stress exhibited heightened negative emotional responses after a solitary riding intervention subsequent to stress-inducing stimuli 13 . Variations in the type of physical activity appear to yield distinct effects on mental health, with individuals’ characteristics also influencing how physical activity impacts their mental well-being 14 . The precise psychological processes altered by physical activity remain to be clearly delineated.

Self-efficacy, a key component of Bandura’s social cognitive theory, is considered integral to social competence. It encompasses individuals’ belief in their ability to effectively navigate the demands of dynamic societal conditions and to tackle challenges in evolving societies 15 . Connolly discovered a connection between one’s behavior, social environment, and self-efficacy 16 . Furthermore, the exercise and self-esteem models suggest that physical activity is linked to the process of self-perception and self-evaluation. Individuals who engage in regular physical activity consistently demonstrate elevated levels of self-efficacy 17 . Furthermore, a previous study indicated that individuals with initially high levels of physical activity, even if declining, exhibited greater self-efficacy than those with low physical activity levels that were also declining 18 . This phenomenon could be attributed to the consistent accomplishment of self-set physical activity goals, contributing to heightened self-confidence and self-perception. Consequently, individuals may develop an enhanced sense of self-efficacy. Elevated levels of self-efficacy correlate with reduced depression and anxiety, as well as an increased sense of subjective well-being 19 . Earlier investigations demonstrated that typically developing adolescents exhibited higher self-efficacy in contrast to emotionally disturbed counterparts 16 . Individuals with greater self-efficacy exhibit increased confidence in addressing unforeseen life challenges, approach problems with a positive attitude, thereby fostering a heightened stability in their mental health. Physical activity potentially enhances mental well-being via the intermediary of self-efficacy, achieved by heightening the pleasure and emotional states during acute exercise sessions 20 .

Stress management involves techniques aimed at helping individuals recognize and cope with stressors through a range of strategies 21 . In contrast to general stress management, stress self-management pertains specifically to stress management behaviors undertaken voluntarily by individuals 22 . Earlier research categorized stress management strategies into dimensions of problem-focused, emotion-focused, and avoidance strategies 23 . Optimal selection of stress management strategies appears contingent upon the nature of the stressor. Broadly, problem-focused and emotion-focused strategies are adaptive coping mechanisms, while avoidance strategies tend to be maladaptive 23 , 24 , 25 . Individuals capable of selecting adaptive stress management strategies for particular stressors demonstrate enhanced stress self-management skills. Currently, adolescents primarily contend with substantial stressors arising from academic demands, which have exhibited a gradual upward trend over the past two decades 26 . Physical activity is recognized as a crucial stress management strategy. Research indicates that individuals engaging in regular physical activity exhibit improved cognitive and executive functions 27 , 28 . They are also more inclined to employ adaptive coping strategies for daily stressors and demonstrate enhanced resilience in facing unexpected challenges. Regular participation in physical activity is typically linked to elevated levels of stress self-management. Hampel’s research revealed that adolescents often employ maladaptive stress self-management strategies to address life stressors, interestingly, adaptive problem-solving and emotion-focused stress management strategies exhibited a decline with advancing age 29 . Research suggests that adolescents who predominantly resort to maladaptive stress self-management strategies are at a heightened risk of developing depression and anxiety 30 . Prioritizing stress management that centers on addressing the stressor directly for problem resolution, rather than avoiding or redirecting attention has been linked to improved mental health 31 . Consistent engagement in physical activity is believed to enhance cognitive and executive capacities in adolescents 27 . Consequently, adolescents acquire improved stress management skills, enabling them to address stressors directly and subsequently fostering positive impacts on mental health.

Self-efficacy and stress self-management may mediate the association between physical activity and mental health, but there is also an association between them. Drawing from self-efficacy theory, individuals tend to steer clear of tasks and situations they perceive as exceeding their capabilities, while engaging in activities they believe they are competent at 32 . Individuals with higher self-efficacy possess greater confidence in their abilities, leading them to embrace adaptive stress self-management strategies instead of avoidance tactics. As a result, they generally exhibit enhanced stress self-management skills. Prior studies have demonstrated that individuals with elevated self-efficacy are more inclined to employ constructive stress coping strategies 29 , 33 . Collectively, the mentioned studies reveal that self-efficacy and stress self-management, integral aspects of self-perception and self-competence, are regarded as significant protective factors for mental health 19 , 31 . It appears that the link between physical activity and mental health might be influenced initially by self-efficacy and subsequently by stress self-management.

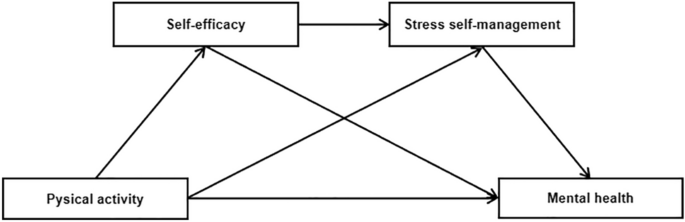

Despite frequent exploration of the association between physical activity and mental health, the underlying mechanisms of this relationship largely remain elusive. Specifically, uncertainties persist regarding the impact of regular participation in physical activity on stress self-management ability, and whether self-efficacy and stress self-management act as mediators in the connection between physical activity and mental health. Consequently, there is a compelling need to investigate these interrelationships among adolescents. Furthermore, adolescents encounter stressors from various dimensions, and these stressors stand as significant contributors to psychological issues. Exploring protective factors influencing adolescents’ stress self-management levels and mental health statuses is pivotal for effective interventions aimed at enhancing adolescent mental well-being. Hence, the present study aimed to explore the correlation between physical activity, self-efficacy, stress self-management, and mental health among adolescents. Furthermore, it seeks to delve into the potential mediating roles of self-efficacy and stress self-management. Drawing from previous research, we have formulated a theoretical model (Fig. 1 ) and put forth the following hypotheses: (1) physical activity is positive related to mental health. (2) self-efficacy mediate the relationship between physical activity and mental health. (3) stress self-management mediate the relationship between physical activity and mental health. (4) self-efficacy and stress self-management play a chain mediation role between physical activity and mental health.

Hypothesis model.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedures.

In March 2023, a cross-sectional study was conducted using a convenient sampling method to collect data from 400 middle school students in Jinan, Shandong province. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki-Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects and other relevant laws, regulations and ethical norms. Prior to the investigation, all participating investigators underwent formal training to ensure the study’s integrity. Students interested in participating were provided with an explanation of the study’s concept and purpose by the investigators. Upon agreeing to participate, students were given access to an electronic questionnaire, which they completed diligently. The questionnaire covered various aspects, including basic sociodemographic information, levels of physical activity, self-efficacy, stress self-management, and mental health indicators. I have followed the STROBE checklist of cross-sectional studies. The study protocol received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the School of Basic Medical Sciences, Shandong University (Approval No. ECSBMSSDU2023-1-74).

400 participants completed the questionnaire, and 43 of them were excluded due to miss values with an effective rate of 89.25%. Among them, 198 (55.5%) were male and 159 (44.5%) were female, 140 (39.2%) were grade 1, 98 (27.5%) were grade 2, 119 (33.3%) were grade 3, 17 (4.8%) came from single-parent family, all came from city. The average age of participants was 13.74 (SD = 1.037) from age 12–16 years.

- Physical activity

The Health Promotion Lifestyle Profile includes Six dimensions that describe self-initiated actions and perceptions of health promotion behaviours 34 . In this study, we used physical activity dimension that include eight items to evaluate how often they adopt promotion physical activity. A 4-point Likert scale was used for quantification, with a score of 1 (never) to 4 (routinely) for each item. The scoring interval is 8 to 32 points. Higher scores indicated better exercise habits. In current study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.9.

Self-efficacy

The Chinese version of the General Self-Efficacy Scale revised by Wang et al. was used to measure global self-efficacy of adolescents. The GSES consists of 10 items with 4-point score ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 4 (completely true) 35 . The range of the total scale was 10–40 points. Higher scores indicated higher levels of general self-efficacy. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.92.

- Stress self-management

The Health Promotion Lifestyle Profile (HPLP) stress management subscale was used to measure the adolescent stress self-management level 34 . The questionnaire on stress self-management includes 8 items and asked respondents to indicate how often they adopted health-promoting stress management behaviours. A 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (routinely) was used to quantification. The range of total scale was 8–32 points. Higher the scores indicated higher levels of stress self-management. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.87.

- Mental health

The Kessler 10 Psychological Distress Scale (K10) is a short self-management rating scale that can detect the risk of psychological conditions in a population 36 . The 10-item scale measured the frequency of non-specific mental health-related symptoms such as anxiety and depression levels experienced in the previous 4 weeks. Likert’s 5-point scoring method was used for each question, and 1 (all the time) to 5 (hardly) points were scored. Higher the scores indicated better mental health. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.95.

Statistical analysis

The data initially collected through the questionnaire platform, specifically the Questionnaire Star platform ( https://www.wjx.cn/ ), was exported for analysis. Descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s alpha test, reliability assessments, and spearman correlation analyses were conducted using SPSS version 27. For the mediation analysis, Hayes’ PROCESS macro in SPSS (version 4.1) was employed. The bootstrap method, involving 5000 resampling iterations to establish robustness and accuracy, was utilized to establish 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for determining the significance of mediating effects. Significance was attributed to direct or indirect effects when the CI did not encompass zero. Gender, age, grade and family structure were included as control variables in the model.ALL variables were standardized before their inclusion in the mediation model.

Institutional review board statement

All materials and procedures of this study were approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Basic Medical Sciences, Shandong University (Approval No. ECSBMSSDU2023-1-74).

Informed consent statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients.

Common method bias analysis

The data for this study were gathered through an online self-assessment approach, which has the potential to introduce common method bias. To address this concern, Harman’s one-way analysis of variance test was conducted to scrutinise the factors associated with all the items encompassed in the study. Through exploratory factor analysis, 7 factors emerged with eigenvalues surpassing 1. However, the variance explained by the first factor was 30.06%, which is below the critical threshold of 40%. This analysis suggests that there is no significant common method bias 37 .

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

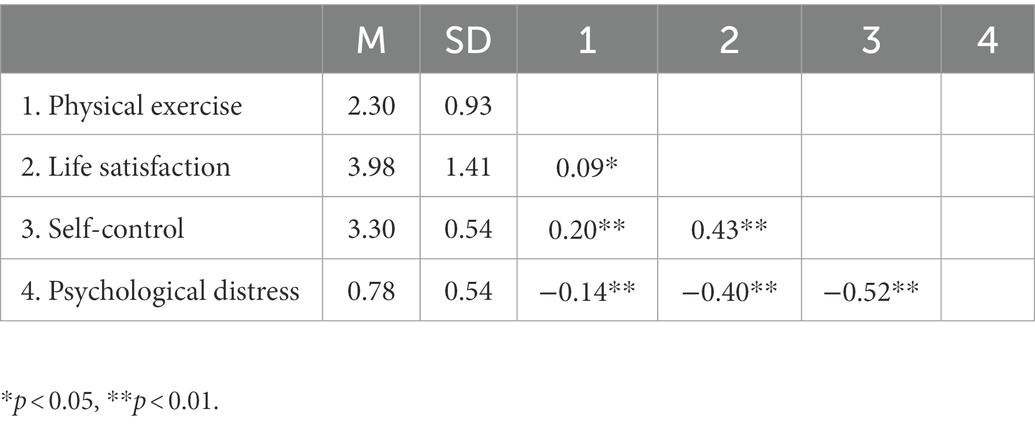

Descriptive statistics of the study variables and their bivariate correlations are shown in Table 1 . When r ≥ 0.4, there is a moderate and strong correlation 38 . The results indicated that physical activity was significantly and positively associated with self-efficacy (r = 0.409, p < 0.01), stress self-management (r = 0.716, p < 0.01) and mental health (r = 0.224, p < 0.01). Self-efficacy (r = 0.256, p < 0.01) was positively and significantly related to stress self-management (r = 0.406, p < 0.01) and mental health. In addition, there was a positive and significant association between self-efficacy and stress self-management (r = 0.373, p < 0.01).

Multicollinearity test

Since there was a significant correlation among all variables, multicollinearity problem may existed leading to unstable results. Therefore, this study conducted multicollinearity diagnostics and standardized the predictor variables in each subsequent equation (to Z-scores). The results found that the tolerance (1–17.7) of all predictor variables is greater than 0.1, and the Variance Inflation Factor (1.240–2.128) is less than 5. Therefore, there is no serious multicollinearity problem in the data, which meets the conditions for further chain mediation analyses.

Mediation analyses

After controlled variables such as gender, age, grade, and family structure among adolescents, a mediation effect test procedure was employed to assess the indirect impact of physical activity on mental health. This indirect effect was found to be mediated by self-efficacy and stress self-management 39 . The model’s fit and the significance of each path coefficient were evaluated using the PROCESS macro program in SPSS, as outlined by Hayes (2017).

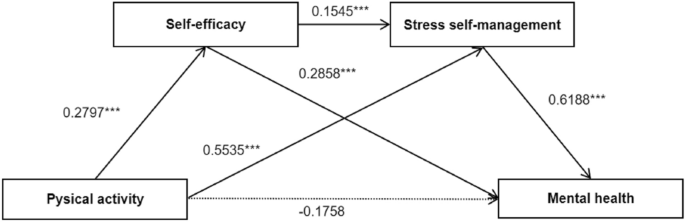

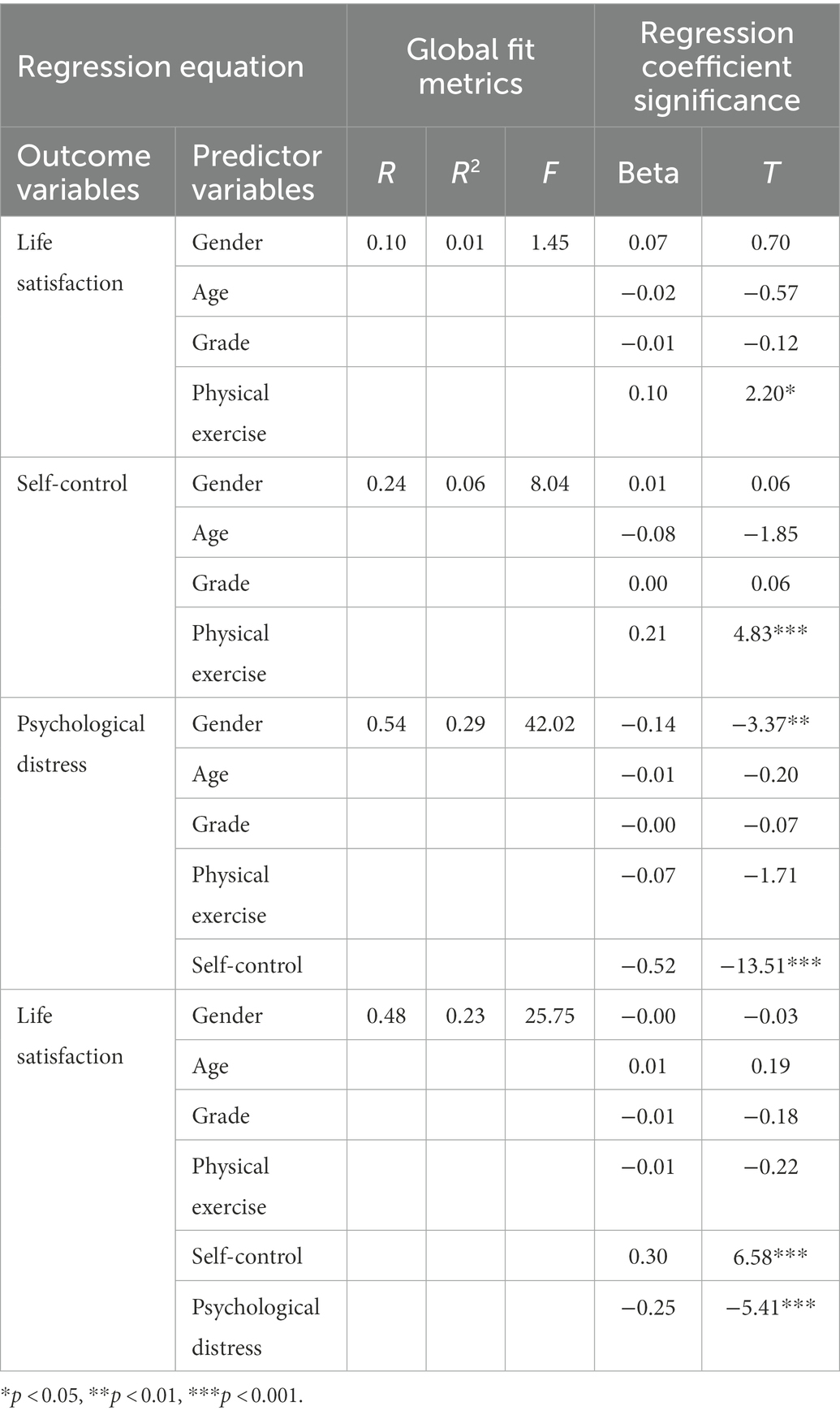

Table 2 shows the regression coefficients for the self-efficacy and stress self-management mediators. The results showed that physical activity was positively and significantly associated with self-efficacy (β = 0.2797, p < 0.001) and stress self-management (β = 0.5535, p < 0.001). Self-efficacy and stress self-management (β = 0.1545, p < 0.001) and mental health (β = 0.2858, p < 0.001) was positively and significantly related. In addition, stress self-management and mental health was positively and significantly related (β = 0.6188, p < 0.001). No significant association was observed between physical activity and mental health.

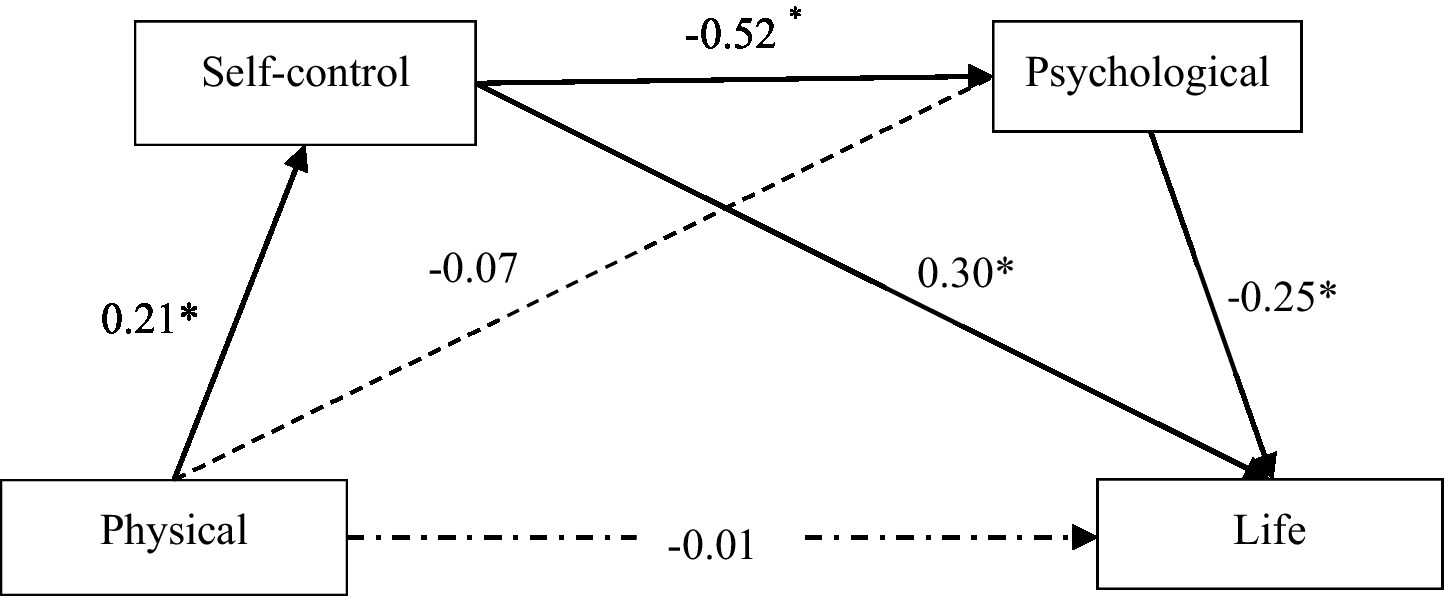

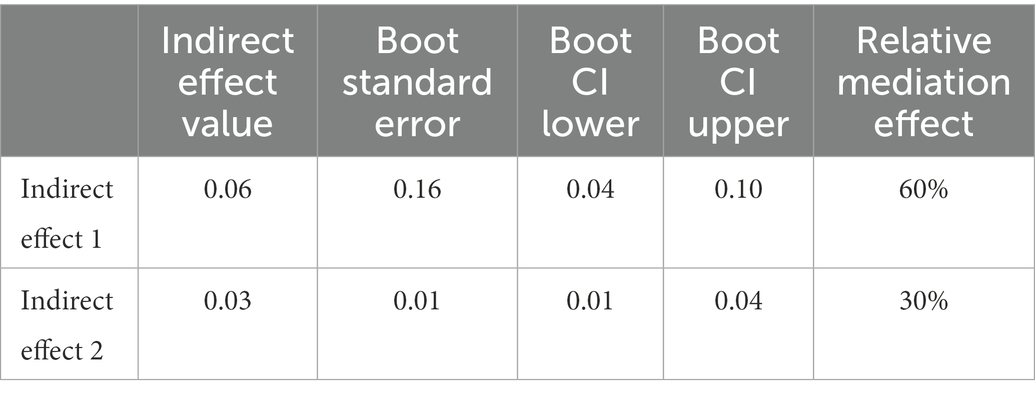

Table 3 and Fig. 2 illustrates the results of the mediation analysis. The direct effect of physical activity on mental health was not significant, but the indirect effect was significant (95% CI: 0.3061-0.6065). The indirect effects of physical activity on mental health via self-efficacy and stress self-management were 0.0799 (95% CI: 0.0041-0.1801) and 0.3425 (95% CI: 0.2044-0.4948) significantly. In addition, the chained mediating effect of self-efficacy and stress self-management was 0.0267 (95% CI: 0.0070-0.0560). Therefore, self-efficacy and stress self-management play a complete mediating role between physical activity and mental health.

Effect of the chain-mediating model of self-efficacy and stress self-management on physical activity and mental health. ***p<0.001.

This study explored the underlying mechanisms that link physical activity, self-efficacy, stress self-management, and mental health. The findings affirmed a noteworthy positive correlation between physical activity and mental health, thereby substantiating hypothesis H1. These results align with the findings of Doré et al. and consequently provide additional confirmation that physical activity stands as a crucial protective factor for mental health 7 .

Simultaneously, this study revealed that the link between physical activity and mental health lost its significance once the two mediating variables of self-efficacy and stress self-management were introduced. Moreover, the comprehensive indirect effect of these two mediating variables was deemed significant, and the indirect effect significantly outweighed the direct effect. This pattern indicated that self-efficacy and stress self-management jointly mediated the connection between physical activity and mental health. The outcomes indicated that physical activity initially predicted mental health without accounting for mediating variables. However, when self-efficacy and stress self-management were considered as mediating variables, their presence mediated the relationship between physical activity and mental health. This suggests that physical activity serves as a more distal factor influencing mental health, potentially due to its intrinsic nature. Physical activity is a consciously planned behavior rooted in personal intentions and motivations 40 . It also constitutes a behaviour shaped by external environmental influences, serving personal development or external incentives 41 . Positive outcomes or experiences gained from physical activity, particularly when proportional gains and positive experiences are achieved, are more likely to yield enhanced effects on mental health 42 , 43 , 44 . When adolescents were unable to obtain a good experience from physical activity or fail to meet their motivations, it may not have an impact on their mental health 45 . Physical activity experiences varied among individuals, and the effects of physical activity are not immediately perceptible 46 , 47 . Mental health improvements required prolonged intervention and was influenced by a multitude of factors 48 , with physical activity being just one of them. The time lag in observing the effects of physical activity on mental health can lead to its influence being overshadowed or affected by other factors, such as stressors and unexpected events in life 49 . Therefore, making adolescents more promptly aware of the benefits of physical activity is a core element in promoting their mental health.

The findings further substantiate the assertion that physical activity can influence mental health via the autonomous mediation of self-efficacy and stress self-management, as well as through the interconnected mediation of both. Hypotheses H2, H3, and H4 were confirmed. This underscores the significance of bolstered self-efficacy and proficient stress self-management as fundamental routes through which physical activity exerts its impact on mental health. In contemporary times, the Resilience Portfolio Model has emerged as a vital framework for comprehending the holistic landscape of protective factors and mental health processes among individuals navigating adversity 50 , 51 , 52 . This model delineates protective factors into three domains: regulation, meaning-making, and interpersonal factors, highlighting the pivotal role of enhancing self-worth, refining self-regulation, and fostering positive interpersonal relationships as crucial protective mechanisms for mental health 44 . Previous studies have illuminated the mediating role of resilience in connecting physical activity with mental health 53 . Likewise, research has identified self-efficacy and stress self-management, integral components of personal value and self-regulation, respectively as correlates of regular physical activity 32 , 33 . Self-efficacy theory posits that self-efficacy levels correlate with the perception of one’s capabilities and the mobilization of intrinsic cognitive resources, significantly influencing coping efficacy. Individuals endowed with high self-efficacy are inclined to harness their internal resources to confront life’s changes, thus showcasing enhanced stress management prowess. Conversely, individuals with lower self-efficacy often perceive themselves as incapable of effectively managing various life stressors, which may lead to passive coping strategies and reduced stress management efficacy. Further investigations have highlighted the association between self-efficacy and the behavioral stages of stress management, as outlined by the transtheoretical model 54 . The decrement in self-efficacy coincides with diminished engagement in stress self-management behaviors. Consequently, the impact of physical activity on mental health is channeled through the pathways of personal value and self-regulation, as well as through the intricate chain mediation involving personal value and self-regulation.

Indeed, the mediating role of self-efficacy can be illuminated from two key perspectives, both centered on the reinforcement of the personal value of physical activity. From this vantage point, self-efficacy operates through the lenses of individual perceptions regarding the effects and experiences derived from engaging in physical activity. Physical activity yields direct associations with a host of favorable outcomes encompassing physical fitness, body image, subjective physical well-being, positive emotional experiences, self-esteem, and overall life satisfaction 42 . This amalgamation of factors collectively constitutes a cognitive resource reservoir that bolsters mental health and fosters positive well-being. Those individuals who experience positive outcomes and emotions stemming from physical activity are more inclined to consistently take part in it. This sustained engagement fosters heightened self-perceptions, thereby contributing to elevated self-efficacy. As adolescents’ self-efficacy gains traction, the net result is a mitigation of negative emotions and a more optimistic approach to confronting life’s challenges. Previous research has underscored that mental health has direct links to positive and negative memory biases and positive interpretation biases, while the relationship with negative interpretation biases remains non-significant 55 . Consequently, individuals who reap positive exercise experiences and outcomes through physical activity tend to manifest heightened self-efficacy. This self-efficacy equips them with the tools to confront life’s stressors with a more optimistic disposition, thereby cultivating a more favorable and resilient psychological well-being.

From an alternative standpoint, the mediation effect of stress self-management can be illuminated through the lens of augmented self-regulation. A multitude of studies have underscored that physical activity engenders positive emotional experiences and exhibits a positive correlation with favorable responses to external stimuli 12 , 27 . When confronted with stress-inducing stimuli, individuals who engage in regular physical activity are more inclined to opt for adaptive coping mechanisms. Rooted in prior research, heightened levels of habitual physical activity are linked to an elevated capacity for stress self-management, for two plausible rationales. Firstly, individuals who consistently partake in physical activity tend to perceive lower levels of stress 24 . This, in turn, translates into a milder stress response. Such individuals are apt at emotional regulation, consequently manifesting a greater self-perceived efficacy in managing stress. Secondly, physical activity constitutes a deliberate behavior driven by intentions and goals, necessitating the coordinated functioning of an individual’s cognitive and executive systems. The self-regulatory system, meanwhile, is built on an individual’s cognitive response to intricate external contexts. Individuals who routinely engage in physical activity generally engage in positive cognitive reappraisal, enabling them to navigate changes in their external environment through adaptive means 27 . This skill set is indicative of heightened stress self-management capability.

In conclusion, this study holds noteworthy significance on multiple fronts. Theoretically, it constructs a comprehensive chain mediation model, unraveling potential mechanisms through which physical activity influences mental health. This contribution bears substantial theoretical implications for understanding the intricate underpinnings of mental health outcomes. Moreover, this research represents the pioneering exploration of the interplay between physical activity, self-efficacy, stress self-management, and mental health within the context of Chinese adolescents, thereby extending the application of The Resilience Portfolio Model. From a practical standpoint, this study offers valuable guidance for fostering the mental health of adolescents.

The outcomes of this study provide actionable insights into enhancing adolescent mental health. First, educational bodies, schools, and parents should prioritize the cultivation of adolescents’ awareness and habits related to physical activity. This strategic emphasis can effectively mitigate negative emotions through exercise, thereby nurturing robust mental health among adolescents. Furthermore, educational settings, especially physical education, should concentrate on instructing students to set goals for their physical activity endeavors. Conducting assessments of exercise objectives and outcomes, accompanied by timely encouragement, can notably bolster adolescents’ self-efficacy. Finally, schools were advised to disseminate information on the positive influence of consistent participation in physical activities on the enhancement of stress self-management aptitude and mental well-being. Schools can proactively broaden the scope of physical activity offerings that align with adolescents’ physiological attributes and preferences, thereby providing multifaceted stress-relief avenues and facilitating the ongoing improvement of mental health.

Limitation and implications

Despite the valuable insights provided by this study, it is important to acknowledge its inherent limitations. First and foremost, the study design employed was cross-sectional in nature, thus precluded the establishment of causal relationships. To establish causal inferences, future research endeavors could incorporate experimental methodologies or longitudinal follow-up investigations. Another limitation stems from the questionnaire-based approach utilized in this study, with subjects self-reporting their experiences. This method introduces the potential for self-report bias, subsequently impacting the accuracy and reliability of the gathered data. In subsequent studies, a combination of questionnaire and interview methods might yield more comprehensive and accurate measurements of the variables under investigation. Furthermore, the study’s focus on the mediating role of self-efficacy and stress self-management leaves room for the inclusion of additional relevant moderating variables in future research. By incorporating these variables, a more comprehensive understanding of how physical activity influences mental health can be achieved, allowing for a more nuanced exploration of the underlying dynamics.

In summary, this study elucidated the intricate relationship between physical activity and mental health, revealing the mediating roles of self-efficacy and stress self-management. This study underscores that the impact of physical activity on adolescents’ mental health operates through independent mediation of self-efficacy, independent mediation of stress self-management, and chain mediation involving both self-efficacy and stress self-management. These findings enrich our understanding of the predictive influence of physical activity on mental health. The implications of these findings extend to interventions aimed at fostering physical activity engagement, enhancing self-efficacy, and promoting effective stress self-management, all of which have the potential to positively contribute to enhancing adolescents’ mental health. As the field advances, future research endeavours could delve deeper into discerning which specific types of physical activity are particularly effective in bolstering self-efficacy and stress self-management abilities. This could provide valuable insights into crafting targeted and efficacious interventions to improve adolescent mental health.

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Blakemore, S.-J. Adolescence and mental health. Lancet 393 , 2030–2031 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Casas, F. & González-Carrasco, M. Subjective well-being decreasing with age: New research on children over 8. Child Dev. 90 , 375–394 (2019).

Holmbeck, G. N., Friedman, D., Abad, M. & Jandasek, B. Development and psychopathology in adolescence. In Behavioral And Emotional Disorders In Adolescents: Nature, Assessment, And Treatment (eds Holmbeck, G. N. et al. ) 21–55 (Guilford Publications, 2006).

Google Scholar

Petersen, K. J., Humphrey, N. & Qualter, P. Dual-factor mental health from childhood to early adolescence and associated factors: A latent transition analysis. J. Youth Adolesc. 51 , 1118–1133 (2022).

Johnson, J. G., Cohen, P. & Kasen, S. Minor depression during adolescence and mental health outcomes during adulthood. Br. J. Psychiatry 195 , 264–265 (2009).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

McMahon, E. M. et al. Physical activity in European adolescents and associations with anxiety, depression and well-being. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 26 , 111–122 (2017).

Doré, I., O’Loughlin, J. L., Beauchamp, G., Martineau, M. & Fournier, L. Volume and social context of physical activity in association with mental health, anxiety and depression among youth. Prev. Med. 91 , 344–350 (2016).

Ashdown-Franks, G., Sabiston, C. M., Solomon-Krakus, S. & O’Loughlin, J. L. Sport participation in high school and anxiety symptoms in young adulthood. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 12 , 19–24 (2017).

Article Google Scholar

Iwon, K., Skibinska, J., Jasielska, D. & Kalwarczyk, S. Elevating subjective well-being through physical exercises: An intervention study. Front. Psychol. 12 , 702678 (2021).

Kjellenberg, K., Ekblom, O., Ahlen, J., Helgadóttir, B. & Nyberg, G. Cross-sectional associations between physical activity pattern, sports participation, screen time and mental health in Swedish adolescents. BMJ Open 12 , e061929 (2022).

McGuine, T. A. et al. High School sports during the COVID-19 pandemic: The effect of sport participation on the health of adolescents. J. Athl. Train. 57 , 51–58 (2022).

Hoffmann, M. D., Barnes, J. D., Tremblay, M. S. & Guerrero, M. D. Associations between organized sport participation and mental health difficulties: Data from over 11,000 US children and adolescents. PLoS ONE 17 , e0268583 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bernstein, E. E., Curtiss, J. E., Wu, G. W. Y., Barreira, P. J. & McNally, R. J. Exercise and emotion dynamics: An experience sampling study. Emotion 19 , 637–644 (2019).

Guddal, M. H. et al. Physical activity and sport participation among adolescents: associations with mental health in different age groups. Results from the Young-HUNT study: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 9 , e028555 (2019).

Bandura, A., Freeman, W. H. & Lightsey, R. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. J. Cogn. Psychother . 13 , 158–166 (1999).

Connolly, J. Social self-efficacy in adolescence: Relations with self-concept, social adjustment, and mental health. Can. J. Behav. Sci. Rev. Can. Des Sci. Du comport. 21 , 258–269 (1989).

Sonstroem, R. J., Harlow, L. L. & Josephs, L. Exercise and self-esteem: Validity of model expansion and exercise associations. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 16 , 29–42 (1994).

Saunders, R. P., Dishman, R. K., Dowda, M. & Pate, R. R. Personal, social, and environmental influences on physical activity in groups of children as defined by different physical activity patterns. J. Phys. Act. Health 17 , 867–873 (2020).

Moeini, B. et al. Perceived stress, self-efficacy and its relations to psychological well-being status in Iranian male high school students. Soc. Behav. Pers. 36 , 257–266 (2008).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Robbins, L. B., Pis, M. B., Pender, N. J. & Kazanis, A. S.. Exercise self-efficacy, enjoyment, and feeling states among adolescents. West. J. Nurs. Res. 26 , 699–715 (2004).

Smith, M. S. & Womack, W. M. Stress management techniques in childhood and adolescence: Relaxation training, meditation, hypnosis, and biofeedback: Appropriate clinical applications. Clin. Pediatr. 26 , 581–585 (1987).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Connolly, D. et al. The impact of a primary care stress management and wellbeing programme (RENEW) on occupational participation: A pilot study. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 82 , 112–121 (2019).

Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J. K., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H. & Wadsworth, M. E. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychol. Bull. 127 , 87–127 (2001).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Shepardson, R. L., Tapio, J. & Funderburk, J. S. Self-management strategies for stress and anxiety used by nontreatment seeking veteran primary care patients. Milit. Med. 182 , e1747–e1754 (2017).

Popov, S., Sokic, J. & Stupar, D. Activity matters: Physical exercise and stress coping during the 2020 COVID-19 state of emergency. Psihologija 54 , 307–322 (2021).

Wang, X. & Yang, H. Is academic burden really less and less—A cross-sectional historical meta-analysis of the academic pressure of middle school students. Educ. Res. Shanghai https://doi.org/10.16194/j.cnki.31-1059/g4.2022.10.013 (2022).

Perchtold-Stefan, C. M., Fink, A., Rominger, C., Weiss, E. M. & Papousek, I. More habitual physical activity is linked to the use of specific, more adaptive cognitive reappraisal strategies in dealing with stressful events. Stress Health 36 , 274–286 (2020).

Edwards, S. Physical exercise and psychological well-being. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 36 , 357–373 (2006).

Hampel, P. Brief report: Coping among Austrian children and adolescents. J. Adolesc. 30 , 885–890 (2007).

Bischoff, L. L., Baumann, H., Meixner, C., Nixon, P. & Wollesen, B. App-tailoring requirements to increase stress management competencies within families: Cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 23 , e26376 (2021).

Vogel, E. A. et al. Physical activity and stress management during COVID-19: A longitudinal survey study. Psychol. Health 37 , 51–61 (2022).

Cicognani, E. Coping strategies with minor stressors in adolescence: Relationships with social support, self-efficacy, and psychological well-being: Coping strategies with minor stressors. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 41 , 559–578 (2011).

Hussong, A. M., Midgette, A. J., Thomas, T. E., Coffman, J. L. & Cho, S. Coping and mental health in early adolescence during COVID-19. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 49 , 1113–1123 (2021).

Walker, S., Sechrist, K., Pender N. The Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile II . Omaha: University of Nebraska Medical Center, College of Nursing (1995).

Wang, C., Hu, Z. & Liu, Y. A study on the reliability and validity of general self -efficacy scales. Appl. Psychol. 49 , 37–40 (2001).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol. Med. 32 , 959–976 (2002).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88 , 879–903 (2003).

Akoglu, H. User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 18 , https://ubir.buffalo.edu/xmlui/handle/10477/2957?show=full 91–93 (2018).

Wen, Z., Zhang, L., Hou, J. & Liu, H. Mediation effect test procedure and its application. J. Psychol. 5 , 614–620 (2004).

Lubans, D. R., Foster, C. & Biddle, S. J. H. A review of mediators of behavior in interventions to promote physical activity among children and adolescents. Prev. Med. 47 , 463–470 (2008).

Conroy, D. E., Hyde, A. L., Doerksen, S. E. & Ribeiro, N. F. Implicit attitudes and explicit motivation prospectively predict physical activity. Ann. Behav. Med. 39 , 112–118 (2010).

Gomez-Baya, D., Mendoza, R., Matos, M. G. D. & Tomico, A. Sport participation, body satisfaction and depressive symptoms in adolescence: A moderated-mediation analysis of gender differences. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 16 , 183–197 (2019).

Christiansen, L. B. et al. Improving children’s physical self-perception through a school-based physical activity intervention: The move for well-being in school study. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 14 , 31–38 (2018).

Cai, G., Ji, L. & Su, J. A study of the relationship between perception of physical activity and motivation for physcial activity and mental health in elementary and middle school students. J. Psychol. Sci. 41 , 844–846 (2004).

Mothes, H. et al. Expectations affect psychological and neurophysiological benefits even after a single bout of exercise. J. Behav. Med. 40 , 293–306 (2017).

Crone, D. & Guy, H. ‘ I know it is only exercise, but to me it is something that keeps me going’ : A qualitative approach to understanding mental health service users’ experiences of sports therapy. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 17 , 197–207 (2008).

Doré, I. et al. Years participating in sports during childhood predicts mental health in adolescence: A 5-year longitudinal study. J. Adolesc. Health 64 , 790–796 (2019).

Berg, N., Kiviruusu, O., Grundström, J., Huurre, T. & Marttunen, M. Stress, development and mental health study, the follow-up study of finnish TAM cohort from adolescence to midlife: Cohort profile. BMJ Open 11 , e046654 (2021).

Sheikh, M. A., Abelsen, B. & Olsen, J. A. Clarifying associations between childhood adversity, social support, behavioral factors, and mental health, health, and well-being in adulthood: A population-based study. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00727 (2016).

Grych, J., Hamby, S. & Banyard, V. The resilience portfolio model: Understanding healthy adaptation in victims of violence. Psychol. Violence 5 , 343–354 (2015).

Banyard, V., Hamby, S. & Grych, J. Health effects of adverse childhood events: Identifying promising protective factors at the intersection of mental and physical well-being. Child Abus. Negl. 65 , 88–98 (2017).

Grych, J., Taylor, E., Banyard, V. & Hamby, S. Applying the dual factor model of mental health to understanding protective factors in adolescence. Am. J. Orthopsychiatr. 90 , 458–467 (2020).

Li, H., Yan, J., Shen, B., Chen, A. & Huang, C. The effect of extracurricular physical exercise on life satisfaction of senior primary school students: The chain mediating effect of self-confidence and psychological resilience. China Sports Sci. Technol. 58 , 51–56 (2022).

CAS Google Scholar

Deng, K., Tsuda, A., Horiuchi, S. & Aoki, S. Processes of change, pros, cons, and self-efficacy as variables associated with stage transitions for effective stress management over a month: A longitudinal study. BMC Psychol. 10 , 122 (2022).

Parsons, S., Songco, A., Booth, C. & Fox, E. Emotional information-processing correlates of positive mental health in adolescence: A network analysis approach. Cognit. Emot. 35 , 956–969 (2021).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants for their efforts in our study.

The work was supported by Social Science Planning Project of Shandong province, grant number 21DTYJ01.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Physical Education, Shandong University, Jinan, 250061, China

Ge Zhang, Wanxuan Feng, Liangyu Zhao, Xiuhan Zhao & Tuojian Li

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Study design and data collection: T.L., X.Z.; Analysis and interpretation of the data: G.Z., W.F.; Writing original draft: G.Z. Writing-review and editing: L.Z., T.L., G.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Tuojian Li .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Zhang, G., Feng, W., Zhao, L. et al. The association between physical activity, self-efficacy, stress self-management and mental health among adolescents. Sci Rep 14 , 5488 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56149-4

Download citation

Received : 06 September 2023

Accepted : 01 March 2024

Published : 06 March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-56149-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- General self-efficacy

- Physical education

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

How Exercise Might Increase Your Self-Control

By Gretchen Reynolds

- Sept. 27, 2017

For most of us, temptations are everywhere, from the dessert buffet to the online shoe boutique. But a new study suggests that exercise might be a simple if unexpected way to increase our willpower and perhaps help us to avoid making impulsive choices that we will later regret.

Self-control is one of those concepts that we all recognize and applaud but do not necessarily practice. It requires forgoing things that entice us, which, let’s face it, is not fun. On the other hand, lack of self-control can be consequential for health and well-being, often contributing to problems like weight gain, depression or money woes.

Given these impacts, scientists and therapists have been interested in finding ways to increase people’s self-restraint. Various types of behavioral therapies and counseling have shown promise. But such techniques typically require professional assistance and have for the most part been used to treat people with abnormally high levels of impulsiveness.

There have been few scientifically validated options available to help those of us who might want to be just a little better at resisting our more devilish urges.

So for the new study, which was published recently in Behavior Modification , a group of researchers at the University of Kansas in Lawrence began wondering about exercise.

Exercise is known to have considerable psychological effects. It can raise moods, for example, and expand people’s sense of what they are capable of doing. So perhaps, the researchers speculated, exercise might alter how well people can control their impulses.

To find out, the scientists decided first to mount a tiny pilot study, involving only four men and women.

These volunteers, who had been sedentary and overweight, were told they would be taking part in an exercise program to get them ready to complete a 5K race, and that the study would examine some of the effects of the training, including psychological impacts.

The volunteers began by completing a number of questionnaires, including one that quantified their “delay discounting,” a measure that psychologists use to assess someone’s ability to put off pleasures now for greater enjoyments in the future. It tests, for instance, whether a person would choose to accept $5 today or $15 a week from now.

The delay-discounting questionnaire is generally accepted in research circles as a valid measure of someone’s self-control.

The volunteers then undertook a two-month walking and jogging regimen, meeting three times a week for 45 minutes with the researchers, who coached them through the sessions, urging them to maintain a pace that felt difficult but sustainable. Each week the men and women also repeated the questionnaires.

Finally, a month after the formal training had ended, the volunteers returned to the university for one more round of testing. (Later, two of them also ran 5K races.)

The results were intriguing, the researchers felt. Three of the four participants had developed significantly greater self-control, according to their delay-discounting answers, and maintained those gains a month after the formal training had ended. But one volunteer, who had missed multiple sessions, showed no changes in impulsivity.

A four-person study is too small to be meaningful, though, so the researchers next repeated the experiment with 12 women of varying ages, weights and fitness levels.

The results were almost identical to those in the pilot study. Most of the women gained a notable degree of self-control, based on their questionnaires, after completing the walking and jogging program. (In this experiment, they were told they were training for better fitness.)

But the increases were proportional; the more sessions a woman attended or the more her average jogging pace increased, the greater the improvement in her delay-discounting score.

These gains lingered a month after the training had ended, although most of the women had tapered off their exercise routines by then.

The upshot of these results would seem to be that exercise could be a simple way to help people shore up their self-restraint, says Michael Sofis, a doctoral candidate in applied behavioral science at the University of Kansas who led the study.

These two experiments cannot tell us, though, how exercise helps us to ignore a cupcake’s allure. But Mr. Sofis says that many past studies have concluded that regular exercise alters the workings of portions of the brain involved in higher-level thinking and decision-making, which, in turn, play important roles in impulse control.

Exercise also may have more abstract psychological impacts on our sense of self-control, he says. It is, for many of us, a concentrated form of delayed gratification. Exerting ourselves during a workout is not always immediately pleasurable. But it can feel marvelous afterward to know that we managed to keep going, a sensation that could spill over into later decision-making.

Of course, with a total of only 16 participants, these experiments remained small-scale and limited, relying on a fundamentally artificial, mathematical measure of self-control. The scientists did not, for example, track whether the volunteers became less impulsive in their actual daily lives. Mr. Sofis and his colleagues hope to conduct follow-up studies that will look at the real-world impacts of exercise on self-control.

But for now, he says, these results suggest that normal people “can change and improve their self-control with regular physical activity.”

Let Us Help You Pick Your Next Workout

Looking for a new way to get moving we have plenty of options..

To develop a sustainable exercise habit, experts say it helps to tie your workout to something or someone .

Viral online exercise challenges might get you in shape in the short run, but they may not help you build sustainable healthy habits. Here’s what fitness fads get wrong .

Does it really matter how many steps you take each day? The quality of the steps you take might be just as important as the amount .

Is your workout really working for you? Take our quiz to find out .

To help you start moving, we tapped fitness pros for advice on setting realistic goals for exercising and actually enjoying yourself.

You need more than strength to age well — you also need power. Here’s how to measure how much you have and here’s how to increase yours .

Pick the Right Equipment With Wirecutter’s Recommendations

Want to build a home gym? These five things can help you transform your space into a fitness center.

Transform your upper-body workouts with a simple pull-up bar and an adjustable dumbbell set .

Choosing the best running shoes and running gear can be tricky. These tips make the process easier.

A comfortable sports bra can improve your overall workout experience. These are the best on the market .

Few things are more annoying than ill-fitting, hard-to-use headphones. Here are the best ones for the gym and for runners .

Advertisement

The Effects of Stress on Physical Activity and Exercise

- Systematic Review

- Published: 13 September 2013

- Volume 44 , pages 81–121, ( 2014 )

Cite this article

- Matthew A. Stults-Kolehmainen 1 &

- Rajita Sinha 1

41k Accesses

607 Citations

256 Altmetric

29 Mentions

Explore all metrics

Psychological stress and physical activity (PA) are believed to be reciprocally related; however, most research examining the relationship between these constructs is devoted to the study of exercise and/or PA as an instrument to mitigate distress.

The aim of this paper was to review the literature investigating the influence of stress on indicators of PA and exercise.

A systematic search of Web of Science, PubMed, and SPORTDiscus was employed to find all relevant studies focusing on human participants. Search terms included “stress”, “exercise”, and “physical activity”. A rating scale (0–9) modified for this study was utilized to assess the quality of all studies with multiple time points.

The literature search found 168 studies that examined the influence of stress on PA. Studies varied widely in their theoretical orientation and included perceived stress, distress, life events, job strain, role strain, and work–family conflict but not lifetime cumulative adversity. To more clearly address the question, prospective studies ( n = 55) were considered for further review, the majority of which indicated that psychological stress predicts less PA (behavioral inhibition) and/or exercise or more sedentary behavior (76.4 %). Both objective (i.e., life events) and subjective (i.e., distress) measures of stress related to reduced PA. Prospective studies investigating the effects of objective markers of stress nearly all agreed (six of seven studies) that stress has a negative effect on PA. This was true for research examining (a) PA at periods of objectively varying levels of stress (i.e., final examinations vs. a control time point) and (b) chronically stressed populations (e.g., caregivers, parents of children with a cancer diagnosis) that were less likely to be active than controls over time. Studies examining older adults (>50 years), cohorts with both men and women, and larger sample sizes ( n > 100) were more likely to show an inverse association. 85.7 % of higher-quality prospective research (≥7 on a 9-point scale) showed the same trend. Interestingly, some prospective studies (18.2 %) report evidence that PA was positively impacted by stress (behavioral activation). This should not be surprising as some individuals utilize exercise to cope with stress. Several other factors may moderate stress and PA relationships, such as stages of change for exercise. Habitually active individuals exercise more in the face of stress, and those in beginning stages exercise less. Consequently, stress may have a differential impact on exercise adoption, maintenance, and relapse. Preliminary evidence suggests that combining stress management programming with exercise interventions may allay stress-related reductions in PA, though rigorous testing of these techniques has yet to be produced.

Conclusions

Overall, the majority of the literature finds that the experience of stress impairs efforts to be physically active. Future work should center on the development of a theory explaining the mechanisms underlying the multifarious influences of stress on PA behaviors.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Does stress result in you exercising less or does exercising result in you being less stressed or is it both testing the bi-directional stress-exercise association at the group and person (n of 1) level.

Matthew M. Burg, Joseph E. Schwartz, … Karina W. Davidson

Deciphering the role of physical activity in stress management during a global pandemic in older adult populations: a systematic review protocol

Ryan Churchill, Indira Riadi, … Theodore Cosco

Everyday stress components and physical activity: examining reactivity, recovery and pileup

David M. Almeida, David Marcusson-Clavertz, … Joshua M. Smyth

Wei M, Gibbons LW, Kampert JB, et al. Low cardiorespiratory fitness and physical inactivity as predictors of mortality in men with type 2 diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(8):605–11.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Blair SN, Kampert JB, Kohl HW, et al. Influences of cardiorespiratory fitness and other precursors on cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in men and women. JAMA. 1996;276(3):205–10.

Brown DW, Balluz LS, Heath GW, et al. Associations between recommended levels of physical activity and health-related quality of life—findings from the 2001 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey. Prev Med. 2003;37(5):520–8.

PubMed Google Scholar

Helmrich SP, Ragland DR, Leung RW, et al. Physical activity and reduced occurrence of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(3):147–52.

Stampfer MJ, Hu FB, Manson JE, et al. Primary prevention of coronary heart disease in women through diet and lifestyle. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(1):16–22.

Friedenreich CM. Physical activity and cancer prevention: from observational to intervention research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10(4):287–301.

Walsh NP, Gleeson M, Shephard RJ, et al. Position statement part one: immune function and exercise. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2011;17:6–63.

Ross R, Dagnone D, Jones PJH, et al. Reduction in obesity and related comorbid conditions after diet-induced weight loss or exercise-induced weight loss in men—a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(2):92–103.

Whelton SP, Chin A, Xin X, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise on blood pressure: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(7):493–503.

Rethorst CD, Wipfli BM, Landers DM. The antidepressive effects of exercise: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Sports Med. 2009;39(6):491–511.

Wipfli BM, Rethorst CD, Landers DM. The anxiolytic effects of exercise: a meta-analysis of randomized trials and dose-response analysis. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2008;30(4):392–410.

Resnick HE, Carter EA, Aloia M, et al. Cross-sectional relationship of reported fatigue to obesity, diet, and physical activity: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2(2):163–9.

Theorell-Haglow J, Lindberg E, Janson C. What are the important risk factors for daytime sleepiness and fatigue in women? Sleep. 2006;29(6):751–7.

Lautenschlager NT, Cox KL, Flicker L, et al. Effect of physical activity on cognitive function in older adults at risk for Alzheimer disease—a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300(9):1027–37.

Rovio S, Kareholt I, Helkala EL, et al. Leisure-time physical activity at midlife and the risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4(11):705–11.

Centers for Disease Control. Prevalence of self-reported physically active adults—United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:1297–300.

Google Scholar

Lutz RS, Stults-Kolehmainen MA, Bartholomew JB. Exercise caution when stressed: stages of change and the stress–exercise participation relationship. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2010;11(6):560–7.

American Psychological Association. Stress in America; 2012. http://www.stressinamerica.org . Accessed 30 April 2013.

Salmon P. Effects of physical exercise on anxiety, depression, and sensitivity to stress: a unifying theory. Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21(1):33–61.

Lutz RS, Lochbaum MR, Lanning B, et al. Cross-lagged relationships among leisure-time exercise and perceived stress in blue-collar workers. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 2007;29(6):687–705.

Da Silva MA, Singh-Manoux A, Brunner EJ, et al. Bidirectional association between physical activity and symptoms of anxiety and depression: the Whitehall II study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2012;27(7):537–46.

Roshanaei-Moghaddam B, Katon WJ, Russo J. The longitudinal effects of depression on physical activity. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(4):306–15.

Gutman DA, Nemeroff CB. Stress and depression. In: Baum A, Contrada R, editors. The handbook of stress science. New York: Springer; 2011. p. 345–58.

McEwen BS. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(3):873–904.

Wagner BM, Compas BE, Howell DC. Daily and major life events: a test of an integrative model of psychosocial stress. Am J Community Psychol. 1988;16(2):189–205.

Chrousos G, Gold PW. The concepts of stress and stress system disorder: overview of physical and behavioral homeostasis. JAMA. 1992;267:1244–52.

Sinha R. How does stress increase risk of drug abuse and relapse? Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2001;158(4):343–59.

CAS Google Scholar

Koolhaas JM, Bartolomucci A, Buwalda B, et al. Stress revisited: a critical evaluation of the stress concept. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(5):1291–301.

Stults-Kolehmainen MA, Bartholomew JB. Psychological stress impairs short-term muscular recovery from resistance exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(11):2220–7.

Cohen S, Kessler RC, Gordon LU. Strategies for measuring stress in studies of psychiatric and physical disorders. In: Cohen S, Kessler RC, Gordon LU, editors. Measuring stress: a guide for health and social scientists. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. p. 3–26.

Singer B, Ryff CD. Hierarchies of life histories and associated health risks. In: Adler NE, Marmot M, McEwen B, Stewart J, editors. Socioeconomic status and health in industrial nations: social, psychological, and biological pathways. New York: New York Academy of Sciences; 1999. p. 96–115.

Seeman TE, Singer BH, Rowe JW, et al. Price of adaptation—allostatic load and its health consequences—MacArthur studies of successful aging. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(19):2259–68.

Danese A, McEwen BS. Adverse childhood experiences, allostasis, allostatic load, and age-related disease. Physiol Behav. 2012;106(1):29–39.

Thoits PA. Stress and health: major findings and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51:S41–53.

Miller G, Chen E, Cole SW. Health psychology: developing biologically plausible models linking the social world and physical health. Annu Rev Psychol. 2009;60:501–24.

Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer; 1984.

Smith CA, Kirby LD. The role of appraisal and emotion in coping and adaptation. In: Contrada RJ, Baum A, editors. The handbook of stress science. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2011. p. 195–208.

McEwen BS. Stress, adaptation, and disease: allostasis and allostatic load. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;840:33–44.

Rozanski A, Blumenthal JA, Kaplan J. Impact of psychological factors on the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and implications for therapy. Circulation. 1999;99(16):2192–217.

Rosengren A, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. Association of psychosocial risk factors with risk of acute myocardial infarction in 11,119 cases and 13,648 controls from 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364(9438):953–62.

Kivimaki M, Leino-Arjas P, Luukkonen R, et al. Work stress and risk of cardiovascular mortality: prospective cohort study of industrial employees. BMJ. 2002;325(7369):857–60.

Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(4):601–30.

PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Cohen S, Tyrrell DAJ, Smith AP. Psychological stress and susceptibility to the common cold. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:606–12.

Sapolsky RM. Glucocorticoids, stress, and their adverse neurological effects: relevance to aging. Exp Gerontol. 1999;34(6):721–32.

Woolley CS, Gould E, McEwen BS. Exposure to excess glucocorticoids alters dendritic morphology of adult hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Brain Res. 1990;531(1–2):225–31.

Sandi C. Stress, cognitive impairment and cell adhesion molecules. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(12):917–30.

Hasler G, Buysse DJ, Gamma A, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness in young adults: a 20-year prospective community study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(4):521–9.

Cho HJ, Bower JE, Kiefe CI, et al. Early life stress and inflammatory mechanisms of fatigue in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26(6):859–65.

Gerber M, Puhse U. Do exercise and fitness protect against stress-induced health complaints? A review of the literature. Scand J Public Health. 2009;37(8):801–19.

Hamer M. Psychosocial stress and cardiovascular disease risk: the role of physical activity. Psychosom Med. 2012;74(9):896–903.

Cheng YW, Kawachi I, Coakley EH, et al. Association between psychosocial work characteristics and health functioning in American women: prospective study. BMJ. 2000;320(7247):1432–6.

Siervo M, Wells JCK, Cizza G. The contribution of psychosocial stress to the obesity epidemic: an evolutionary approach. Horm Metab Res. 2009;41(4):261–70.

CAS PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Holmes ME, Ekkekakis P, Eisenmann JC. The physical activity, stress and metabolic syndrome triangle: a guide to unfamiliar territory for the obesity researcher. Obes Rev. 2010;11(7):492–507.

Ogden LG, Stroebele N, Wyatt HR, et al. Cluster analysis of the national weight control registry to identify distinct subgroups maintaining successful weight loss. Obesity. 2012;20(10):2039–47.

Bartholomew JB, Stults-Kolehmainen MA, Elrod CC, et al. Strength gains after resistance training: the effect of stressful, negative life events. J Strength Cond Res. 2008;22(4):1215–21.

Stranahan AM, Khalil D, Gould E. Social isolation delays the positive effects of running on adult neurogenesis. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9(4):526–33.

Tucker LA, Clegg AG. Differences in health care costs and utilization among adults with selected life style-related risk factors. Am J Health Promot. 2002;16(4):225–33.

Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical-activity, exercise, and physical-fitness—definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100(2):126–31.

USDHHS. Physical activity and health: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 1999.

Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, et al. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(7):1334–59.

Owen N, Healy GN, Matthews CE, et al. Too much sitting: the population health science of sedentary behavior. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2010;38(3):105–13.

Edenfield TM, Blumenthal JA. Exercise and stress. In: Baum A, Contrada R, editors. Handbook of stress science. New York: Springer; 2011. p. 301–20.

Dunn AL, Trivedi MH, O’Neal HA. Physical activity dose-response effects on outcomes of depression and anxiety. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(6):S587–97.

Long BC. Aerobic conditioning and stress reduction: participation or conditioning? Hum Mov Sci. 1983;2(3):171–86.

Babyak M, Blumenthal JA, Herman S, et al. Exercise treatment for major depression: maintenance of therapeutic benefit at 10 months. Psychosom Med. 2000;62(5):633–8.

Craft LL, Landers DM. The effect of exercise on clinical depression and depression resulting from mental illness: a meta-analysis. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1998;20(4):339–57.

Buckley TC, Mozley SL, Bedard MA, et al. Preventive health behaviors, health-risk behaviors, physical morbidity, and health-related role functioning impairment in veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Mil Med. 2004;169(7):536–40.

Ginis KAM, Latimer AE, McKechnie K, et al. Using exercise to enhance subjective well-being among people with spinal cord injury: the mediating influences of stress and pain. Rehabil Psychol. 2003;48(3):157–64.

Jonsson D, Johansson S, Rosengren A, et al. Self-perceived psychological stress in relation to psychosocial factors and work in a random population sample of women. Stress Health. 2003;19(3):149–62.

King AC, Taylor CB, Haskell WL. Effects of differing intensities and formats of 12 months of exercise training on psychological outcomes in older adults. Health Psychol. 1993;12(4):292–300.

Knab AM, Nieman DC, Sha W, et al. Exercise frequency is related to psychopathology but not neurocognitive function. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(7):1395–400.

Lambiase MJ, Barry HM, Roemmich JN. Effect of a simulated active commute to school on cardiovascular stress reactivity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(8):1609–16.

McHugh JE, Lawlor BA. Exercise and social support are associated with psychological distress outcomes in a population of community-dwelling older adults. J Health Psychol. 2012;17(6):833–44.

Sanchez-Villegas A, Ara I, Guillen-Grima F, et al. Physical activity, sedentary index, and mental disorders in the SUN Cohort Study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(5):827–34.

Schnohr P, Kristensen TS, Prescott E, et al. Stress and life dissatisfaction are inversely associated with jogging and other types of physical activity in leisure time—the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2005;15(2):107–12.

Skirka N. The relationship of hardiness, sense of coherence, sports participation, and gender to perceived stress and psychological symptoms among college students. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2000;40:63–70.

de Assis MA, de Mello MF, Scorza FA, et al. Evaluation of physical activity habits in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinics. 2008;63(4):473–8.

Taylor-Piliae RE, Fair JM, Haskell WL, et al. Validation of the Stanford Brief Activity Survey: examining psychological factors and physical activity levels in older adults. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(1):87–94.

Brown JD, Siegel JM. Exercise as a buffer of life stress—a prospective-study of adolescent health. Health Psychol. 1988;7(4):341–53.

Mooy JM, de Vries H, Grootenhuis PA, et al. Major stressful life events in relation to prevalence of undetected type 2 diabetes—the Hoorn study. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(2):197–201.

Steptoe A, Kimbell J, Basford P. Exercise and the experience and appraisal of daily stressors: a naturalistic study. J Behav Med. 1998;21(4):363–74.

Nguyen-Michel ST, Unger JB, Hamilton J, et al. Associations between physical activity and perceived stress/hassles in college students. Stress Health. 2006;22(3):179–88.

Aldana SG, Sutton LD, Jacobson BH, et al. Relationships between leisure time physical activity and perceived stress. Percept Mot Skills. 1996;82(1):315–21.

Anderson RT, King A, Stewart AL, et al. Physical activity counseling in primary care and patient well-being: do patients benefit? Ann Behav Med. 2005;30(2):146–54.

Hopkins ME, Davis FC, Vantieghem MR, et al. Differential effects of acute and regular physical exercise on cognition and affect. Neuroscience. 2012;215:59–68.

Jonsdottir IH, Rodjer L, Hadzibajramovic E, et al. A prospective study of leisure-time physical activity and mental health in Swedish health care workers and social insurance officers. Prev Med. 2010;51(5):373–7.

Norris R, Carroll D, Cochrane R. The effects of physical activity and exercise training on psychological stress and well-being in an adolescent population. J Psychosom Res. 1992;36(1):55–65.

Oaten M, Cheng K. Longitudinal gains in self-regulation from regular physical exercise. Br J Health Psychol. 2006;11:717–33.

Urizar GG, Hurtz SQ, Albright CL, et al. Influence of maternal stress on successful participation in a physical activity intervention: the IMPACT project. Women Health. 2005;42(4):63–82.

Baruth M, Wilcox S. Effectiveness of two evidence-based programs in participants with arthritis: findings from the active for life initiative. Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63(7):1038–47.

Atlantis E, Chow CM, Kirby A, et al. An effective exercise-based intervention for improving mental health and quality of life measures: a randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2004;39(2):424–34.

Imayama I, Alfano CM, Kong A, et al. Dietary weight loss and exercise interventions effects on quality of life in overweight/obese postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8(118):1–12.

King AC, Baumann K, O’Sullivan P, et al. Effects of moderate-intensity exercise on physiological, behavioral, and emotional responses to family caregiving: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(1):M26–36.

Wilcox S, Dowda M, Leviton LC, et al. Active for life—final results from the translation of two physical activity programs. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(4):340–51.

Connell CM, Janevic MR. Effects of a telephone-based exercise intervention for dementia caregiving wives: a randomized controlled trial. J Appl Gerontol. 2009;28(2):171–94.

Hamer M, Taylor A, Steptoe A. The effect of acute aerobic exercise on stress related blood pressure responses: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol Psychol. 2006;71(2):183–90.

Greenwood BN, Kennedy S, Smith TP, et al. Voluntary freewheel running selectively modulates catecholamine content in peripheral tissue and c-Fos expression in the central sympathetic circuit following exposure to uncontrollable stress in rats. Neuroscience. 2003;120(1):269–81.

Greenwood BN, Fleshner M. Exercise, stress resistance, and central serotonergic systems. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2011;39(3):140–9.

Throne LC, Bartholomew JB, Craig J, et al. Stress reactivity in fire fighters: an exercise intervention. Int J Stress Manage. 2000;7(4):235–46.

Carmack CL, Boudreaux E, Amaral-Melendez M, et al. Aerobic fitness and leisure physical activity as moderators of the stress–illness relation. Ann Behav Med. 1999;21(3):251–7.

Crews DJ, Landers DM. A meta-analytic review of aerobic fitness and reactivity to psychosocial stressors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1987;19(5):S114–20.

Jackson EM, Dishman RK. Cardiorespiratory fitness and laboratory stress: a meta-regression analysis. Psychophysiology. 2006;43(1):57–72.

McGilley BM, Holmes DS. Aerobic fitness and response to psychological stress. J Res Pers. 1988;22(2):129–39.

Holmes DS, Cappo BM. Prophylactic effect of aerobic fitness on cardiovascular arousal among individuals with a family history of hypertension. J Psychosom Res. 1987;31(5):601–5.

Chafin S, Christenfeld N, Gerin W. Improving cardiovascular recovery from stress with brief poststress exercise. Health Psychol. 2008;27(Suppl 1):S64–72.

Cox JP, Evans JF, Jamieson JL. Aerobic power and tonic heart-rate responses to psychological stressors. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1979;5(2):160–3.

Jamieson J, Flood K, Lavoie N. Physical fitness and heart-rate recovery from stress. Can J Behav Sci. 1994;26(4):566–77.

Fleshner M. Physical activity and stress resistance: sympathetic nervous system adaptations prevent stress-induced immunosuppression. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2005;33(3):120–6.

Dienstbier RA. Behavioral-correlates of sympathoadrenal reactivity—the toughness model. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1991;23(7):846–52.