- Contact Address

- Donate to IEU

- Index Search

IEU'S FEATURED TOPICS IN UKRAINIAN ART AND ARCHITECTURE

FRESCO PAINTING. A method of painting on freshly plastered walls with powdered pigments that are resistant to the erosive action of lime. Before the colors are applied to the wet plaster the main lines of the composition are usually traced on the preceding coat. The painting is very durable and is applied to both interior and exterior walls. The origins of fresco painting in Ukraine can be traced back to the 4th century BC. Frescoes adorned the homes, public buildings, and tombs of the Greek colonists and Scythians on the coast of the Black Sea. The most interesting ancient frescoes from the 1st century BC were discovered during excavations of burial sites in Kerch in the tomb of Demeter...

[FRESCOES OF] SAINT SOPHIA CATHEDRAL. Saint Sophia Cathedral is a masterpiece of the art and architecture of Ukraine and Europe. It was built in Kyiv at the height of Kyivan Rus', in the Byzantine style, and significantly transformed during the baroque period. The cathedral was founded by Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise and built between 1037 and 1044. The original building, most of which remains at the core of the existing cathedral, is a cross-in-square plan with twelve cruciform piers marking five east-west naves intersected by five transverse aisles. The cathedral's interior is decorated with magnificient 11th-century mosaics and frescoes. Exterior ornamentation of the original 11th-century walls consists of decorative brickwork, the monochromatic painting of key architectural elements, and a number of frescoes...

[FRESCOES OF] SAINT MICHAEL'S GOLDEN-DOMED MONASTERY. An Orthodox men's monastery in Kyiv. In the 1050s Prince Iziaslav Yaroslavych built Saint Demetrius's Monastery and Church in the old upper city of Kyiv, near Saint Sophia Cathedral. In 1108-13 his son, Sviatopolk II Iziaslavych, built a church at the monastery dedicated to Saint Michael the Archangel. The monastery was mostly destroyed during the Tatar invasion of 1240 and ceased to exist. Written records confirm that it was reopened by 1496. Soon afterward it began to be known as Saint Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery, its name being taken from the church built by Sviatopolk II Iziaslavych. Restored and enlarged over the 16th century, it became one of the most popular and wealthy monasteries in Ukraine. ...

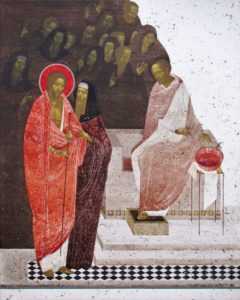

[FRESCOES OF] SAINT CYRIL'S MONASTERY. A monastery founded by Grand Prince Vsevolod Olhovych ca 1140 on the outskirts of medieval Kyiv. Its church, Saint Cyril's, was built ca 1146. The church's frescoes are fine examples of 12th-century Ukrainian art and the influence of Bulgarian-Byzantine painting on it. They depict the Nativity of Christ, the Presentation of Christ at the Temple, the Eucharist, the Annunciation, the Dormition, the Last Judgment and Apocalypse, an angel gathering the heavens into a scroll, the apostles, the evangelists, and various prophets and martyrs. Murals of saints--Saint Cyril and Saint Methodius, Saint John the Macedonian, Saint Euphemios--adorn its pillars, and compositions depicting Saint Cyril teaching the heretic, teaching in the cathedral, and teaching the emperor are found in the southern apse...

In the 8th-9th century, the second Golden Age of Byzantine art began. During this period Kyivan Rus' actively entered the orbit of Byzantine culture and in 988 adopted Christianity through Byzantium. In fact, Byzantine influence on Ukrainian territory began much earlier and was concentrated on the northern shores of the Black Sea, in such cities as Kerch and Chersonese Taurica. The earliest Kyivan churches built in the Byzantine style (such as the Church of the Tithes) did not survive the continual invasions of nomadic hordes. However, the Saint Sophia Cathedral, begun in 1037, has been preserved in relatively good condition. It represents a masterpiece of the art and architecture of Ukraine and Europe. According to the Rus' chronicles, Prince Volodymyr the Great imported the first architects and artists from Chersonese, and these together with the artists of Constantinople were the first creators of Kyivan mosaics and frescos... Learn more about the legacy of Byzantine art in Ukraine, and in particular the Byzantine art of mosaic, by visiting the following entries:

MOSAIC. A method of wall and floor decoration in which small pieces of cut stone, glass (tesserae), and, occasionally, ceramic or other imperishable materials are set into plaster, cement, or waterproof mastic. The earliest existing examples of mosaics in Ukraine are fragments from the floor of a domestic bath found at the site of the Greek colony of Chersonese Taurica (ca 3rd-2nd century BC). Made of various colored pebbles, the floor depicts two nude figures and decorative motifs. Mosaic was used to decorate various Rus' churches and palaces in the 10th to 12th centuries, including the Church of the Tithes (989-96), the Saint Sophia Cathedral (1037 to the late 1040s), the Dormition Cathedral of the Kyivan Cave Monastery (1078), and Saint Michael's Church (1108-13) of the Saint Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery...

[MOSAICS OF] SAINT SOPHIA CATHEDRAL. The centripetal plan of Saint Sophia Cathedral, internal volumes, and external massing reflect the hierarchical ordering of the mosaics and frescoes inside. As the surfaces of the walls advance from the floor and the narthex, the frescoes increase in size and religious significance and culminate in the monumental mosaics Mother of God (Orante) in the central apse and Christ Pantocrator in the central dome. Among the most masterful mosaics are those of the Church Fathers . The more archaic Orante in the central apse, often referred to as the Indestructible Wall , is the most famous....

BYZANTINE ART. Visual art produced in the Byzantine Empire and in countries under its political control or cultural influence, among them Ukraine. The spread of Byzantine art was the result, in large measure, of its style, which had all the traits of universalism to which other cultures could easily adapt. This style began to develop in the 6th century AD during the first Golden Age under the reign of Emperor Justinian. It was based on Greco-Roman art and the art of the East--Syria, Asia Minor, Persia, and Egypt. In architecture, churches with stone cupolas symbolizing the cosmos appeared, replacing the longitudinal basilicas with flat wooden ceilings...

[MOSAICS OF] SAINT MICHAEL'S GOLDEN-DOMED MONASTERY. The main church of the Saint Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery (built in either 1654-7 or 1108-13) is an important architectural and cultural monument. Originally it had three naves and three apses on the eastern side and was topped by a single large gilded cupola. It was rebuilt in a baroque style and expanded with a new facade and six additional cupolas in the 18th century. The most striking elements of the interior were the 12th-century frescoes and mosaics, probably done by Kyivan artisans (including perhaps Master Olimpii). Although many of these were destroyed in the 13th to 16th century, some--notably the mosaics of Saint Demetrius of Thessalonika, the Eucharist, and Archdeacon Stephen--survived and were partially restored in the late 19th century...

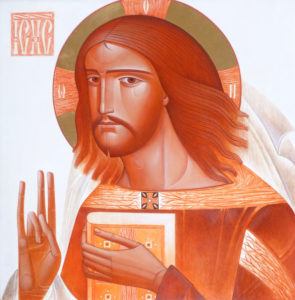

ICON. An image depicting a holy personage or scene in the stylized Byzantine manner, and venerated in the Eastern Christian churches. The image can be executed in different media; hence, the term 'icon' can be applied to mural paintings, frescoes, or mosaics, tapestries or embroideries, enamels, and low reliefs carved in marble, ivory, or stone or cast in metal. The typical icon, however, is a portable painting on a wooden panel. The earliest technique of icon painting was encaustic, but the traditional and most common technique is tempera. The paint--an emulsion of mineral pigments (ochers, siennas, umbers, or green earth), egg yolk, and water--is applied with a brush to a panel covered with several layers of gesso. Gold leaf is fixed to designated areas before painting begins. The paint is applied in successive layers from dark to light tones; then the figures are outlined and, finally, certain areas are highlighted with whitener. After drying, the painting is covered with a special varnish consisting of linseed oil and crystalline resins to protect it from dust and humidity...

ICONOSTASIS. A solid wooden, stone, or metal screen separating the sanctuary from the nave in Eastern Christian churches. Of varying height, it consists of rows of columns and icons. It extends the width of the sanctuary and has three entrances: the large Royal Gates at the center and the smaller Deacon Doors on each side. The Royal Gates are hung with a curtain. The iconostasis evolved in Byzantium in the 9th-11th centuries. The icons of the iconostasis are separated by columns and are arranged in several rows. The number of icons and ranges can vary. Usually, a full iconostasis contains over 50 icons set in four to six rows, but simpler (one- or two-story) and more elaborate (seven-story) iconostases are known. In Ukraine the earliest iconostases were low, consisting of only two tiers. Their further development was conditioned by the development of wooden architecture and the decline of the art of mosaics. By the 14th-15th centuries the typical structure of the two- and three-tiered iconostasis was established...

RUTKOVYCH, IVAN, b ? in Bilyi Kamin, near Zolochiv, Galicia, d ? Icon painter of the 17th century. Most of his creative life was spent in Zhovkva (1667 to ca 1708) where, among other things, he was one of the key figures in the Zhovkva School of Artists. Some of his work has been preserved, in whole or in part, such as the iconostases of the wooden churches in Volytsia Derevlianska (1680-2) and Volia Vysotska (1688-9); the large iconostasis of the Church of Christ's Nativity in Zhovkva (1697-9, now in the National Museum in Lviv), which is considered to be the finest Ukrainian iconostasis; and separate icons, such as Supplication (1683) from Potylych (now in the National Museum) and The Nativity of Virgin Mary (1683) from Vyzhliv. Rutkovych's treatment of religious subjects was realistic and almost secular in spirit. The emotive richness of his colors and the rhythm of his lines testify to the influence of contemporary European art on his style. Vira Svientsitska's book about Rutkovych was published in Kyiv in 1966...

KONDZELEVYCH, YOV, b 1667 in Zhovkva, Galicia, d ca 1740 in Lutsk, Volhynia. Noted icon painter and elder of the Bilostok Monastery in Volhynia. After his training at the Zhovkva School of Artists, he probably studied painting at the Kyivan Cave Monastery Icon Painting Studio and abroad. Some of his numerous works have survived, including a fragment of the Bilostok Monastery iconostasis; the tabernacle of the Zahoriv Monastery (1695); and the famous iconostasis of the Maniava Hermitage, painted in 1698-1705 and transferred in 1785 to the church in Bohorodchany upon the dissolution of the hermitage. In 1923 the iconostasis was deposited in the National Museum in Lviv under the name the Bohorodchany iconostasis. In 1722 Kondzelevych took part in painting the iconostasis of the Zahoriv Monastery. His last work was The Crucifixion (1737) for the Lutsk Monastery. Kondzelevych broadened the traditional scheme of the icon significantly: he devoted much attention to the surroundings, particularly to the landscape, which he filled with distinctive architectural ensembles...

Petro Kholodny The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries featuring the timeless tradition of the Ukrainian icon were made possible by the financial support of the CANADIAN FOUNDATION FOR UKRAINIAN STUDIES . IV. THE ART OF PORTRAITURE IN UKRAINE The oldest form of secular art in Ukraine, portraiture dates back to the 4th-century BC portraits found in burial sights in the Greek city of Chersonese Taurica. Medieval examples are the depictions of Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise and his family (1044) in the frescoes of the Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv and the depictions of Grand Prince Sviatoslav II Yaroslavych and his family in the illuminations of the Izbornik of Sviatoslav (1073). Prince Yaropolk Iziaslavych and his wife are shown in the Trier Psalter (1078-87). Secular portraits of nobles, notable Cossacks, peasant leaders, and rich burghers gained currency in the 16th century and grew in popularity through the 17th and 18th centuries. A special type of portrait painting developed in Ukraine, the parsunnyi (from the Latin persona), depicting notable figures in rich attire and formal poses against a background reaffirming their official status. During the baroque period of the late 17th and early 18th centuries many official portraits of Cossack hetmans, including Bohdan Khmelnytsky, Ivan Mazepa, Ivan Skoropadsky, Danylo Apostol, and Pavlo Polubotok, were painted depicting the regalia of office. Church leaders were also well represented in portraiture. Family portraits mirrored social and historical changes in their composition and the manner in which the subjects were painted. The development of regional styles gave rise to the Kyivan, Galician, and Volhynian schools of portrait painting. Portraits were also made by engravers, such as Leontii Tarasevych, Oleksander Tarasevych, Ivan Shchyrsky, and Hryhorii K. Levytsky. The tsarist abolition of Ukrainian autonomy in the 18th century coincided with the establishment of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts (1758), which attracted many Ukrainian artists. Dmytro H. Levytsky of Kyiv became a professor at the academy and the greatest portraitist in the Russian Empire of his time. Volodymyr Borovykovsky, another outstanding portraitist, also worked in Saint Petersburg in the classical, academic manner favored by the imperial court. In the 19th century many portraits were painted in Ukraine by trainees of the academy. Portraits were also painted by wandering artists and by artists who were formers serfs, such as Taras Shevchenko, whose contribution to the Ukrainian art has often been underrated. Portraits remained popular throughout the 19th century, and, in the 20th century, artists have created portraits in a wide variety of styles... Learn more about the art of portraiture in Ukraine by visiting the following entries:

PORTRAITURE. The artistic depiction of one or more particular persons. Although portraiture did not emerge as a separate genre in the Ukrainian art until the 16th century, its existence may be traced back to some icons: the canonical renderings of Saint Anthony of the Caves and Saint Theodosius of the Caves in the Holy Protectress of the Caves icon (ca 1288), where they have been given individualized features. In the late 15th and early 16th centuries the rendering of icon countenances became more realistic as a result of Renaissance influences (eg, the Krasiv Mother of God ). In the 17th century, realistic portrayals of patrons were part of the composition of icons, such as the Holy Protectress , with a portrait of Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky, and the fresco Supplication (1644-6), with Metropolitan Petro Mohyla, in the Transfiguration Church in Berestove in Kyiv. Late 16th- to 18th-century religious and secular portraits at first had some characteristics of the icon, such as flattened forms, static frontal composition, and hieratic figural representation. With time, under the influence of Renaissance painting, they became three-dimensional and were painted with a linear and aerial perspective. Many portraits of patrons of shrines and churches were painted and displayed inside churches. Memorial portraits of members of the upper classes were painted on wood or metal and attached to the lids of their coffins. One of the most sensitive and beautifully modeled was that of V. Lanhysh (1635), found in the Lviv Dormition Brotherhood's portrait collection...

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries about the art of portraiture in Ukraine were made possible by the financial support of the CANADIAN FOUNDATION FOR UKRAINIAN STUDIES . V. THE ART OF SCULPTURE IN UKRAINE Sculptural depictions (schematized female figures made from mammoth bones) dating back to the Paleolithic Period have been found in Ukraine at the Mizyn archeological site (ca 18,000 BC). Terra-cotta figures from the Trypilian culture and stone stelae have survived from the Bronze Age. The Scythians left behind beautiful examples of relief sculpture. Numerous examples of Hellenic figural sculpture have been found among the ruins of the ancient states on the northern Black Sea coast. Pre-Christian examples from the 1st millennium AD include the stone temples and idols, such as the Zbruch idol. Life-size freestanding stone baby dating from the 11th to 13th centuries AD were erected in the steppes of Ukraine by Turkic tribes. However, only a few sculptures from the period of Kyivan Rus' (10th-12th centuries) have been preserved. This is because the Eastern church opposed figural carving. As the influence of Renaissance art spread to Ukraine, particularly Galicia, sculpture became more common. During the baroque period (mid-17th to early 18th century) in Ukraine, relief carvings reached the zenith of their development in architectural decoration and in the multistoried iconostasis, rather than, as in western Europe, in three-dimensional sculpture. The best and most numerous examples of three-dimensional sculpture are to be found in Galicia in the work of talented local sculptors and imported ones, such as Johann Georg Pinzel. Classicism appeared in the mid-1750s and brought with it a return to the harmony, clarity, and serenity of antiquity. Among Ukrainian artists working in the classical style was Ivan Martos, who worked mostly in Russia. In the second half of the 19th century romanticism and realism replaced classicism. In Russian-ruled Ukraine Fedir Balavensky introduced Ukrainian ethnographic elements into his allegorical sculptures. The modernist sculptor Alexander Archipenko, who gained international fame in Paris in the 1910s, is the most famous Ukrainian sculptor... Learn more about the art of sculpture in Ukraine by visiting the following entries:

SCULPTURE. A general term in visual art for three-dimensional representations made by carving or modeling in a variety of materials, of which stone and clay are the most widely used. Sculpture encompasses monuments and statues, which are usually large in scale and are meant for public display; decorative or ornamental works; and small forms. Basically it may be divided into works that are freestanding and works that are attached to a background (relief sculpture). In most regions of Ukraine the development of sculpture was hindered by the hostile attitude of the Orthodox church to sculptural images. Sculpture was limited to relief carvings, mostly in stone or wood. They were often limited to architectural decorations and carvings of the iconostases. During Renaissance secular buildings, especially in Galicia, were lavishly decorated with carved reliefs. It is also in Galicia that the best and most numerous examples of three-dimensional sculpture are to be found. There sculpture was incorporated into church and secular architecture and were particularly popular in Roman Catholic churches. The developement of sculpture in Ukraine during classicism was inspired by Greek rather than Roman prototypes and was more geometric and austere. However, classicism coincided with the decline of Ukrainian autonomy and the annexation of eastern and most of central Ukraine by Russia. Thus, most prominent Ukrainian sculptors in Russian-ruled Ukraine were compelled to work within the Imperial Russian context in Saint Petersburg or abroad...

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries the art of sculpture in Ukraine were made possible by the financial support of the CANADIAN FOUNDATION FOR UKRAINIAN STUDIES . VI. THE ART OF UKRAINIAN BAROQUE ENGRAVING In Ukraine, from the 11th to the 16th century manuscript books were ornamented with headpieces, initials, tailpieces, and illuminations. Many of these features appeared as well in the first printed books. In the late 16th century Lviv became the first center of printing and graphic art and one of the first influential engravers was Lavrentii Fylypovych-Pukhalsky. Graphic-art centers also arose at printing presses established in Ostrih, Volhynia, in Striatyn and Krylos in Galicia, and finally in Kyiv at the highly advanced engraving shop of the Kyivan Cave Monastery Press. Beginning in the second half of the 17th century, in addition to religious themes, secular and everyday subjects, portraits, town plans, etc were depicted in graphic form. During the Ukrainian baroque period, which coincided with the Hetman state, engraving became highly developed, utilizing not only new forms, but also allegory, symbolism, heraldry, and very ornate decoration. These characteristics suited the belligerency and dynamism of the Cossack period, whose apogee during the hetmancy of Ivan Mazepa defined the artistic fashion for the late 17th and early 18th centuries. The most famous Kyivan craftsman of the time was the portraitist and illustrator Oleksander Tarasevych (active from 1667 to 1720). Other notable craftsmen were Ivan Shchyrsky, Zakharii Samoilovych, Leontii Tarasevych, Ivan Strelbytsky, and Ivan Myhura, who was known for his very personal style incorporating folk art motifs. In Western Ukraine most prominent master engravers included Dionisii Sinkevych and Nykodym Zubrytsky. After the defeat of Ivan Mazepa at the Battle of Poltava in 1709, cultural life in Ukraine declined because of Russian political restrictions and the migration of Ukrainian intellectuals and artists to Saint Petersburg. Nevertheless, Kyiv still had such craftsmen as Averkii Kozachkivsky and especially Hryhorii K. Levytsky, the most prominent Ukrainian engraver of the 18th century... Learn more about art of Ukrainian baroque engraving by visiting the following entries:

MASTER ILLIA, b and d ? A 17th-century wood engraver. A monk at Saint Onuphrius's Monastery, in the 1630s he worked as an engraver in Lviv. From 1640 to about 1680 he worked at the Kyivan Cave Monastery Press. During his career he produced about 600 woodcuts for illustrations, title pages, headpieces, and prints. His work decorated such books as the Euchologion of Petro Mohyla (Kyiv 1646), one of the finest examples of Ukrainian book design of the time; the Nomocanon (Lviv 1646); the Kyivan Cave Patericon (Kyiv 1661, 1678); and Lazar Baranovych's Mech dukhovnyi (The Spiritual Sword, 1666) and Antin Radyvylovsky's Ohorodok Marii Bohorodytsi (The Garden of Mary, the Mother of God, 1676). Two albums of his woodcuts were published in Kyiv in the 1640s, and a collection of 132 of his biblical illustrations appeared at the end of the 17th century. Illia was a master of the thematic woodcut. His illustrations depict daily life, landscapes, buildings, and famous monks of the Kyivan Cave Monastery...

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries about the art of Ukrainian baroque engraving were made possible by the financial support of the CANADIAN FOUNDATION FOR UKRAINIAN STUDIES . VII. MASTERPIECES OF ROCOCO ARCHITECTURE IN UKRAINE In some ways, rococo represented the continuation and conclusion of the baroque period in art and architecture. At the tame time, it signified a fundamental departure from the pathos and striving for the supernatural and spiritual that characterized the creative mind of a baroque artist. Rococo developed at first in a decorative art in the early 18th century in France. Lighter designs, graceful decorative motifs with many shell forms (rocaille in French) and natural patterns, as well as small-scale sculpture inspired by trivial subject matter progressively replaced the flamboyant forms of the baroque architecture, overloaded with unrestrained ornamentation. In Ukraine, where baroque influences were particularly strong and long-lasting, rococo and baroque architectural influences were often intermingled. Rococo influences in Ukrainian sculpture can be seen particularly in iconostases, where carved shell motifs and interlace patterns replaced grapevines and acanthus foliage, often without structural logic. Bartolomeo Francesco Rastrelli and Bernard Meretyn were among the most important rococo architects in Ukraine... Learn more about the masterpieces of rococo architecture in Ukraine by visiting the following entries:

ROCOCO. An architectural and decorative style that emerged in France in the early 18th century. Examples of the rococo style in Ukraine are Saint Andrew's Church (1747-53) in Kyiv; the Cathedral of the Nativity of the Mother of God (1752-63) in Kozelets, Chernihiv gubernia; the Roman Catholic churches of the Dominican order in Lviv (1747-64) and Ternopil (1745-9); Saint George's Cathedral (1745-70) in Lviv; the Dormition Cathedral at the Pochaiv Monastery (1771-83) in Volhynia; and the town hall (1751) in Buchach, Galicia. The iconostases of Saint Andrew's Church in Kyiv and the church of the Mhar Transfiguration Monastery (1762-5) in Poltava gubernia have delicately carved rococo surface decorations. In religious painting the rococo style had little impact in Ukraine because of the strong hold of the baroque. A few still lifes, intimate in scale, appeared for the first time, however, and rococo design and decoration left a mark on furniture produced in Hlukhiv and Nizhyn in Chernihiv gubernia and in Olesko in Galicia...

SAINT ANDREW'S CHURCH IN KYIV. A masterpiece of rococo architecture in Kyiv. It was designed for Empress Elizabeth I by Bartolomeo Francesco Rastrelli and built under the direction of I. Michurin in 1747-53. Set on a hill above the Podil district on a cruciform foundation atop a two-story building, the church has a central dome flanked by four slender towers topped with small cupolas. The exterior is decorated with Corinthian columns, pilasters, and complex cornices designed by Rastrelli and made by master craftsmen, including the Ukrainians M. Chvitka and Ya. Shevlytsky. The interior has the light and grace characteristic of the rococo style. The iconostasis is decorated with carved gilded ornaments, sculptures, and icon paintings done in 1751-4 by Aleksei Antropov and his assistant at the time, Dmytro H. Levytsky. During the Seven Years' War the imperial court lost interest in the church, and it was unfinished when it was consecrated in 1767. Since 1958 the church has been a branch of the Saint Sophia Museum...

SAINT GEORGE'S CATHEDRAL IN LVIV. One of the finest examples of rococo church architecture in Europe. The cathedral's complex, consisting of the church, the campanile (its bell was made in 1341), the metropolitan's palace, office buildings, a wrought-iron fence, two gates, and a garden, stands on a high terrace overlooking the old city of Lviv. The church was designed by and built under the direction of Bernard Meretyn in 1744-59 and finished in 1764 by S. Fessinger, who also built the adjacent metropolitan's residence (1761-2). Built on a cruciform ground plan, the four-column church is topped by one large cupola and four small ones. The high exterior walls are decorated with simplified Corinthian pilasters, rococo stone lanterns, and a cornice. Two stairways with delicate rococo balustrades lead to the main entrance, which is flanked by statues of Ukrainian Metropolitans Atanasii Sheptytsky and Lev Sheptytsky. The cathedral serves as the seat of the Ukrainian Catholic Halych metropoly...

MARIINSKYI PALACE IN KYIV. Using Count Oleksii Rozumovsky's palace in Perov, near Moscow, as his model, Bartolomeo Francesco Rastrelli designed the palace in Kyiv for Empress Elizabeth I. It was built above the Dnieper River in the Pechersk district under the supervision of the architects I. Michurin, P. Neelov, and Ivan Hryhorovych-Barsky in the years 1747-55. Built in the rococo style, the palace consisted of a long central section with a stone ground floor and wooden second story (destroyed by a fire in 1819), two stone one-story wings, and a large adjacent park with an orangery and orchards. The palace was renovated in 1870 according to K. Maievsky's Louis XVI-style design for the visit of Emperor Alexander II and Empress Maria (hence its name). After being damaged and looted during the Second World War, it was rebuilt by 1949. Since the 1990s Mariinskyi Palace has served as the setting for high-level meetings with foreign dignitaries and it is slated to become the official residence of the president of Ukraine...

RASTRELLI, BARTOLOMEO FRANCESCO, b 1700 in Paris, d 1771 in Saint Petersburg. Architect of Italian origin. Having arrived in Saint Petersburg in 1716 with his father, Carlo Bartolomeo Rastrelli, who did many sculptures for Emperor Peter I, he was appointed court architect in 1730. His renovations of the Great Palace in Peterhof (1747-52; now Petrodvorets), the Catherinian Palace in Tsarskoe Selo (1752-7), the Winter Palace (1754-62), Mikhail Vorontsov's palace (1749-57), and S. Stroganov's palace (1752-4) in Saint Petersburg are the finest examples of late baroque and rococo architecture. He designed two outstanding buildings in Kyiv, Saint Andrew's Church (1747-53) and the Mariinskyi Palace (1752-5)...

CLASSICISM. In the art of the 18th century the term classicism denoted a certain general style connected with the esthtic ideals of classical Greek and Roman cultures and with works of art whose simplicity and severity of form contrasted with the decorativeness of the baroque. Its influence was felt first in Western Ukraine, where it manifested itself mainly in the architecture of palaces and villas, such as the palace of the Ossolinskis in Lviv (now the Lviv National Scientific Library of Ukraine), built in 1827 by the Swiss architect P. Nobile, or the palace in Vyshnivets in the Ternopil region. Later these kinds of buildings were built in central and eastern Ukraine by Italian, French, English, and German architects. The largest number of the finest examples of architectural classicism have been preserved in the Chernihiv region: the palace of Count Petro Zavadovsky in Lialychi designed by Giacomo Quarenghi in 1794-5; the building of Mykhailo P. Myklashevsky in Nyzhnie (second half of the 18th century), V. Darahan's residence in Kozelets; and the palaces of a patron of classicism, Hetman Kyrylo Rozumovsky, in Pochep (built in 1796 by Oleksii Yanovsky) and in Baturyn (built in 1799-1803 according to the design of C. Cameron). The classicist style was also embodied in numerous manor houses, churches, and town buildings throughout Ukraine. The most typical buildings of the 19th century in this style are the palaces in the village of Murovani Kurylivtsi (1805); the buildings of the Sofiivka Park near Uman (1796-1805); P. Galagan's palace in Sokyryntsi, designed by P. Dubrovsky in 1829; the Bezborodko Nizhyn Lyceum, designed by L. Rusca in 1824; the Kyiv University building, designed by Vincent Beretti in 1837-42; the new building of the Kyivan Mohyla Academy, designed by Andrei Melensky in 1822-5; and the cathedral in Sevastopol, built in 1843. In these buildings classicism was often combined with the Empire style, which was closely related to it...

LOSENKO, ANTIN, b 10 August 1737 in Hlukhiv, Nizhyn regiment, Hetman state, d 4 December 1773 in Saint Petersburg. Painter; a leading exponent of historical painting in the classicist style. He studied in the Hlukhiv Singing School and was brought to Saint Petersburg to sing in the imperial court choir in the late 1740s. After his voice changed, he was sent to study art under Ivan Argunov (1753-8) and at the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts (1758-60). Recognized for his exceptional talent, Losenko was promised a bursary to study in Paris where he arrived in 1760 and studied under Jean II Restout, but his stay there was cut short in 1762 when the imperial bureaucrats failed to send him his promised stipend. In Paris Losenko painted his first masterpiece The Miraculous Draught of Fishes (1762). In 1766-9 Losenko studied in Rome where he painted, among others, Cain (1768) and Abel (1769). After he was awarded several medals from the Paris Academy of Arts, Losenko's achievements were also recognized in Saint Petersburg. He became a member of and professor at the Saint Petersburg Academy in 1770, served as its director (1772-3), and wrote its textbook on human proportions (1772). Losenko's oeuvre includes paintings on biblical and mythological themes; paintings on historical themes, such as Grand Prince Volodymyr and Rohnida (1770); portraits of prominent personalities; a self-portrait; and some 200 drawings of nude figures and parts of the body, which were held up as models of excellence to students at the academy for many years. Losenko introduced to the art of the Russian Empire the classicist pompier style of painting and was the first painter to depict in this style, in addition to the traditional mythological and biblical motifs, also themes from the history of Kyivan Rus'. Most of his works are preserved at the Russian Museum in Saint Petersburg and the Tretiakov Gallery in Moscow. Only his Abel is housed in Ukraine, in the Kharkiv Art Museum...

LEVYTSKY, DMYTRO, b 1735 in Kyiv, d 16 April 1822 in Saint Petersburg. The most prominent portraitist of the classicist era in the Russian Empire. He acquired his basic training from his father, Kyiv painter and master engraver Hryhorii K. Levytsky, whom he helped to do engravings for the Kyivan Cave Monastery Press. In 1753-6 he assisted his father and Aleksei Antropov in decorating Saint Andrew's Church in Kyiv. From 1758 to 1761 he worked in Saint Petersburg, where he likely studied with Antropov, L.-J.-F. Lagren?, and G. Valeriani. From 1762, while living in Moscow he was a portraitist in great demand among the Russian aristocracy. He moved to Saint Petersburg in 1769, and he won the highest award at the summer exhibition in 1770 held by the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts and was elected a member of the academy. Together with a number of his Ukrainian compatriots in Saint Petersburg, Levytsky was an active Freemason and member of Saint Petersburg's Masonic lodge. A teacher of portraiture at the academy (1771-88), he retired to Ukraine in 1788, but in 1795 he returned to Saint Petersburg to become portraitist at the imperial court. Building on the baroque, classicism, and Western European traditions, Levytsky created a school of portrait painting. His portraits reveal his expert knowledge of drawing, composition, color, and the appropriate gesture. He executed over 100 portraits, including ones of Empress Catherine II, other members of the Russian imperial family, King Stanislaus I Leszczynski, the French encyclopedist Denis Diderot, and his own father, Hryhorii K. Levytsky. One of his paintings is in the permanent collection of the Louvre Museum in Paris. Many Ukrainian and Russian portraitists studied with Levytsky at the academy, and his works influenced the second most prominent portraitist of this period in the Russian Empire, Volodymyr Borovykovsky...

BOROVYKOVSKY, VOLODYMYR, b 4 August 1757 in Myrhorod, Myrhorod regiment, Hetman state, d 18 April 1825 in Saint Petersburg. Iconographer and portrait painter, son of Luka Borovyk (d 1775) who was a Cossack fellow of the banner and an iconographer. Borovykovsky was trained in art by his father and uncle and then in 1788 went to study portrait painting under Dmytro H. Levytsky at the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts. In 1793 he became an academician there. Until 1787 Borovykovsky lived and worked in Ukraine. During his career he painted many churches, icons, and iconostases, only some of which have been preserved: the icons of Christ (1784) and the Virgin Mary (1784 and 1787), now in Kyiv, the icon of SS Thomas and Basil (1770s, in Myrhorod), the iconostases and wall paintings in the village churches in Kybyntsi in the Poltava region and Ichnia in the Chernihiv region, and others. Borovykovsky's religious art departed from the established norms of Byzantine iconography in the Russian Empire and tended towards a realistic approach. In Saint Petersburg Borovykovsky painted about 160 portraits, among them Ukrainian public figures, such as Dmytro Troshchynsky (1819). Among the large number of official portraits he painted are the full-figure portraits of Catherine II (1794) and Paul I (1800). At the beginning of the 1790s Borovykovsky began to paint miniatures and portraits of women in the Ukrainian iconographic style. Adhering to the spirit of classicism, he promoted West European traditions through his art; in his later works he introduced the style of Sentimentalism and proto-Romanticism in painting. The largest number of Borovykovsky's works can be found in the museums of Saint Petersburg and Moscow. In Ukraine they can be seen in the museums of Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odesa, Poltava, Dnipro, Kherson, and Simferopol...

MARTOS, IVAN, b ca 1754 in Ichnia, Pryluky regiment, Hetman state, d 17 April 1835 in Saint Petersburg. Sculptor; father of Oleksander Martos. Born into a Cossack starshyna family of the Poltava region, Martos studied at the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts (1764-73) and in Rome under Antonio Canova (1774-9), where he became a proponent of Classicist style of sculpture. He taught at the Saint Petersburg Academy (1779-1835; as senior professor from 1794) and served as its rector (1814-35). Martos created numerous sculptures in Russia and Ukraine, including the burial monuments of Hetman Kyrylo Rozumovsky in Baturyn (1803-5) and Count Petr Rumiantsev at the Kyivan Cave Monastery (1797-1805) and statues of Count Armand-Emmanuel du Plessis duc de Richelieu in Odesa (1823-8), Emperor Alexander I in Tahanrih (1828-31), and Prince Grigorii Potemkin in Kherson (1829-36). His works are noted for their monumental, but restrained and lucid classicist form that conform to the Classical ideal of beauty and idealize the virtues of courage, patriotism, and civic duty. His work had a considerable influence on many sculptors in the Russian Empire in the first half of the 19th century...

DOLYNSKY, LUKA, b ca 1745 in Bila Tserkva, d 10 March 1824 in Lviv. Painter. Orphaned during the time of the haidamaka uprisings in Right-Bank Ukraine, Dolynsky found support with the Uniate metropolitan of Kyiv Pylyp Volodkovych who recognized his talent and sent him to Lviv to Metropolitan Lev Sheptytsky who became Dolynsky's mentor. Dolynsky studied with Yurii Radylovsky in Lviv in 1770-1 and was later sent to study at the Vienna Academy of Arts (1775-7). In 1777 he settled permanently in Lviv, where he worked as a church artist and portraitist. He painted the interior of Saint George's Cathedral (1770-1 and 1777), decorating the iconostasis and the side altars. In the 1780s and 1790s he decorated various churches in Lviv, including the Church of the Holy Spirit, the Church of Saints Peter and Paul, and the Church of Good Friday in Lviv, and churches in nearby villages. In 1807 and 1810 he painted and gilded the Dormition Cathedral of the Pochaiv Monastery, and in 1820-1 the iconostasis and murals in Saint Onuphrius's Church in Lviv. Dolynsky painted portraits of Prince Lev Danylovych (1770-1), Maria Theresa and Joseph II (1775-7), Metropolitan Fylyp Volodkovych, and others. In combining classical and original Ukrainian stylistic features, he departed from the Lviv guild tradition of icon painting...

ACADEMISM. Art movement based on ancient Greek esthetics and on the dogmatic imitation of primarily classical art forms. Academism first arose in the art academies of Italy in the 16th century and then in France; later it spread to other countries. Art academies were founded in Rome, Paris, Vienna, Berlin, Saint Petersburg, Munich, Cracow, and other cities. Many Ukrainian artists graduated from these schools; for example, Antin Losenko, Ivan Buhaievsky-Blahodarny, Ivan Soshenko, Taras Shevchenko, Dmytro Bezperchy, Volodymyr Orlovsky, Apollon Mokrytsky, Ivan Aivazovsky, Kornylo Ustyianovych, and Teofil Kopystynsky. As advanced schools of art theory and practice, the academies played a positive role in the development of these artists, but eventually their conservatism and dogmatism, their restriction of artistic freedom, and their narrow limits on the selection of theme and formal means (composition, color, technique) called forth a strong reaction among progressive artists. These artists organized their own art groups with anti-academic programs, such as the romantics, the Peredvizhniki, the impressionists, and the Secessionists. Ukrainians--for example, Taras Shevchenko, Mykola Ge, Ivan Kramskoi, Oleksander Lytovchenko, Mykola Bodarevsky, Mykola Pymonenko, and Mykola Yaroshenko, and in time the Ukrainian impressionists--participated in this reaction too. The principles of academism were later revived in the 20th century in Soviet art in Ukraine and primarily manifested itself in socialist-realist portraiture, which was photographically accurate and conformed to officially approved models...

MOKRYTSKY, APOLLON, b 12 August 1810 in Pyriatyn, Poltava gubernia, d 8 or 9 March 1870 in Moscow. Painter; full member of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts from 1849. He studied painting under Kapiton Pavlov at the Nizhyn Lyceum and under Oleksii Venetsianov and Karl Briullov in Saint Petersburg (1830-9). In spite of financial hardships, Mokrytsky successfully completed his course of study at the academy thanks, to a large extent, to the support of his Ukrainian compatriot Vasyl Hryhorovych. After working in Ukraine and visiting Italy Mokrytsky was appointed a professor at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture (1851-70). His students included Ivan Shyshkin and Kostiantyn Trutovsky. Many of Mokrytsky's paintings, particularly the early ones, are executed in the style of academism. His later works, including portraits of Yevhen Hrebinka (1840) and Nikolai Gogol, a self-portrait (1840), and Italian landscapes, are painted in a lucid, realist style. Mokrytsky played an important role in the process of purchasing Taras Shevchenko's freedom; he introduced Shevchenko to influential Russian and Ukrainian intellectuals in Saint Petersburg, in particular, his teachers, artists Briullov and Venetsianov, and poet Vasilii Zhukovsky, who later helped to secure Shevchenko's freedom from serfdom. Mokrytsky left a diary (published in 1975) containing, among other things, information about Shevchenko...

SHEVCHENKO, TARAS, b 9 March 1814 in Moryntsi, Zvenyhorod county, Kyiv gubernia, d 10 March 1861 in Saint Petersburg. Ukraine's national bard and famous artist. Born a serf, at the age of 14 Shevchenko became a houseboy of his owner, P. Engelhardt, and served him in Vilnius and then Saint Petersburg. Shevchenko spent his free time sketching statues in the capital's summer gardens. There he met the Ukrainian artist Ivan Soshenko, who introduced him to other compatriots, such as Apollon Mokrytsky, and to the painter Oleksii Venetsianov. Shevchenko later met the famous Russian painter Karl Briullov, who donated his painting as the prize in a lottery whose proceeds were used to buy Shevchenko's freedom in 1838. Soon after, Shevchenko enrolled in the Imperial Academy of Arts and studied there under Briullov's supervision. Although Shevchenko is known primarily because of his poetry, he was also an accomplished artist; 835 of his art works are extant, and another 270 of his known works have been lost. Trained in the style of academism, Shevchenko moved beyond stereotypical historical and mythological subjects to realistic depictions often expressing veiled criticism of the absence of personal, social, and national freedom under tsarist domination. His portraits have a broad social range of subjects, from simple peasants to prominent Ukrainian and Russian cultural figures and members of the imperial nobility. His portraits are remarkable for the way Shevchenko uses light to achieve sensitive three-dimensional modeling. He also painted and drew numerous landscapes. On 2 September 1860 the Imperial Academy of Arts recognized Shavchenko's mastery by designating him an academician-engraver...

AIVAZOVSKY, IVAN, b 29 July 1817 in Teodosiia, Tavriia gubernia, d 5 May 1900 in Teodosiia. Painter of seascapes, landscapes, and genre paintings. Aivazovsky was descended from a family of Galician Armenians who had settled in the Crimea. He began to study art in Simferopol and completed his artistic education (in 1833-7) at the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg. In the early 1840s he travelled widely through Italy, France, England, the Netherlands, and the Ottoman Empire, and gained high reputation for his masterfully executed seascapes. He become an academician of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts in 1845 and an honorary member of the academy in 1887 (he was also a member of four other academies). In 1845 Aivazovsky settled in Teodosiia. He produced some 6,000 paintings, depicting mainly scenes on the Black Sea and turbulent seascapes and numerous Ukrainian landscapes. During his student years Aivazovsky often traveled in Ukraine with Vasilii Shternberg. In 1880 Aivazovsky established an artists' studio and picture gallery in Teodosiia, which he donated later to the city. The Aivazovsky Picture Gallery in Teodosiia houses some 400 of his works, as well as paintings by Crimean seascape artists and a small collection of seascapes by Western artists. Following the Russian annexation of the Crimea in 2014, some 40 of Aivazovsky's paintings have been removed by the Russian occupation authorities from his gallery in Teodosiia and transferred to the Tretiakov Gallery in Moscow...

GE, MYKOLA (also: Gay, Gue), b 27 February 1831 in Voronezh, d 13 April 1894 at Ivanovskyi khutir , Bakhmach county, Chernihiv gubernia. Painter of mixed French and Ukrainian origin. Ge studied at Kyiv University (1847) and Saint Petersburg University (1848-9), and at the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts (1850-7), where he later became a professor in 1863. Initially, Ge's style of painting was strongly influenced by his teacher Karl Briullov and the principles of academism taught at the Saint Petersburg Academy. In fact, he was one of the leading representatives of academism in the 1850s. In 1856 he received the Academy's Gold Medal for his painting Saul and the Witch of Endor , executed in the academic style. In 1857 he travelled to Western Europe and in 1860 he settled in Italy where he lived, with interruptions, until 1870. Influenced by works of Italian Renaissance masters, Ge continued to paint compositions on Biblical themes, but he also executed numerous landscapes and some portraits. Upon his return to Saint Petersburg in 1870, Ge painted several works on historical subjects and numerous portraits of prominent cultural and political figures, including that of his former teacher Mykola Kostomarov. At that time he became one of the founders of the Russian Society of Itinerant Art Exhibitions, but did not adopt the predominant naturalist style of the Peredvizhniki painters. In 1876 Ge returned to Ukraine where he settled at his estate in Chernihiv gubernia and remained there until his death. There he produced his famous cycle of paintings on New Testament themes...

KOPYSTYNSKY, TEOFIL, b 15 April 1844 in Peremyshl, Galicia, d 5 July 1916 in Lviv. Monumentalist painter and portraitist. A graduate of the Cracow School of Fine Arts (1871) and the Vienna Academy of Art (1872), he spent his life painting churches, iconostases, and icons in Lviv and the surrounding villages. His more important works have been preserved: the murals of the wooden church in Batiatychi, the altar icon of the Transfiguration in the Church of the Transfiguration in Lviv, The Crucifixion (1902) in Saints Cyril and Methodius's Church in Sokolia near Busk, the murals (1911-12) of Saint Michael's Church in Rudnyky, and the iconostases in the churches in Zhovtantsi, Batiatychi, Zhydachiv, Myklashiv (1908), and Synevidsko Vyzhnie. He was also recognized as a restorer and conservator of old art. From 1878 to 1899 Kopystynsky restored a number of religious masterpieces. In 1888 he cleaned and restored 150 old Ukrainian icons at the Stauropegion Institute's museum in Lviv. Kopystynsky established a reputation as a master portraitist and from 1872 to 1895 he painted 17 portraits of prominent Ukrainian social and cultural figures of the 19th century, as well as Hetman Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny and Metropolitan Petro Mohyla. Kopystynsky was also a leading book illustrator in Western Ukraine. He taught drawing in secondary schools in Lviv and participated in the exhibitions of the Society of Friends of the Fine Arts...

In Ukrainian art conventionalized landscape elements were used in icons, while some of the earliest landscapes were settings for the 16th and 17th-century religious engravings. Landscape painting did not, however, become an independent genre in Ukrainian art until the 19th century. Romanticism inspired artists to record faithfully the pastoral scenery of thatched-roof cottages and the surrounding countryside. Among them were Ivan Soshenko, Taras Shevchenko, and Vasilii Shternberg. With time two types of landscape art developed, the poetic and the epic. Among the 19th-century artists who devoted much of their work to Ukrainian landscapes were two artists of non-Ukrainian origin, Ivan Aivazovsky, who is famous for his marine paintings, and Arkhyp Kuindzhi, who painted Romantic moonlit scenes. Other Ukrainian artists who devoted their efforts to landscape painting were Serhii Vasylkivsky, Ivan Pokhytonov, and Serhii Svitoslavsky. In the early 20th century Petro Levchenko painted intimate lyrical views in impressionist colors capturing the fleeting effects of light in both urban and rural scenes. Vasyl H. Krychevsky and Abram Manevich also worked in the impressionist manner. Symbolism was dominant in the fantasy landscapes of Yukhym Mykhailiv. In Western Ukraine Ivan Trush painted idyllic sunsets and panoramic views only slightly influenced by impressionist colors. In the 1930s, after socialist realism was imposed as the only sanctioned artistic method in the USSR, landscape painting was limited to views of collective farms and industrial sites. Pure landscape painting was revived in Ukraine only after the Second World War. Of the Ukrainian landscape artists who worked outside their homeland, the most prominent was Oleksa Hryshchenko, who achieved recognition in France for his landscapes and seascapes, painted mostly in an expressionist manner... Learn more about the tradition of Ukrainian landscape art by visiting the following entries:

LANDSCAPE ART. The depiction of natural scenery. In Ukrainian art conventionalized landscapes and architectural settings became part of the scenes in icons illustrating the lives of saints. During the Renaissance landscapes in icons became less schematized and began looking more like the surrounding Ukrainian countryside. Architecture and local scenery were important elements in the icons of Ivan Rutkovych and Yov Kondzelevych. Landscapes also appeared as backgrounds to portraits. Some of the earliest landscapes were settings for religious engravings. At first they were variations on landscapes borrowed from Western European models, but later, local elements emerged. In 1669 Master Illia depicted the Dnieper River in his engraving. Similar engravings by Leontii Tarasevych showed an even greater preoccupation with local scenery. Depictions of churches and secular buildings appeared in the engraved theses produced in the 17th and 18th centuries by the Kyivan Cave Monastery Press. In the 18th century, landscapes gained greater prominence in religious pictures. Landscape painting become an independent genre in Ukrainian art in the 19th century...

SVITOSLAVSKY, SERHII, b 6 October 1857 in Kyiv, d 19 September 1931 in Kyiv. Landscape painter. After studying at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture (1875-83) he returned to Kyiv. From 1884 he took part in the exhibitions of the Peredvizhniki society, and in 1891 he became a member of the society. During the Revolution of 1905 he contributed to the satirical magazine Shershen' and helped students expelled from the Kyiv Art School. His realist landscapes are noted for their vibrant colors. Some of his best-known works are Dnieper Rapids (1885), Oxen in the Field (1891), Street in a County Town (1895), On a River (1909), Ferry on the Dnieper (1913), Vicinity of Kiev: Winter , Windmill , and The Dnieper at Dusk . His travels in Central Asia in the late 1890s gave rise to a group of landscapes, including Steppe , Goat Herd in the Mountains , and Ships of the Desert (1900). After his eyesight deteriorated in the early 1920s, Svitoslavsky gave up painting. Albums of his works were published in Kyiv in 1955 and 1989...

LEVCHENKO, PETRO, b 11 July 1856 in Kharkiv, d 27 January 1917 in Kharkiv. Painter and pedagogue. He studied art in Kharkiv under Dmytro Bezperchy, at the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts (1878-83), and in Paris and Rome. From 1886 he lectured at the Kharkiv Painting School. He was a member of the Society of South Russian Artists and a participant in almost all of the exhibitions of the Peredvizhniki (1886-1904), and from 1900 his works displayed the influence of the impressionists. Levchenko did some 800 landscapes, primarily of Ukraine (such as A Deserted Place , Night: A Cottage in Moryntsi , A Ukrainian Village , In the Kharkiv Region , A Street in Putyvl , and The Yard of Saint Sophia Cathedral ), but also painted abroad (such as A Street in Paris and Seacoast: Naples ), as well as still lives and genre paintings. A posthumous retrospective exhibition of 700 of his paintings was held in Kharkiv in 1918. Monographs about him were written by M. Pavlenko (1927), Yu. Diuzhenko (1958), and M. Bezkhutry (1984)...

TRUSH, IVAN, b 17 January 1869 in Vysotske, Brody county, Galicia, d 22 March 1941 in Lviv. Painter, community figure, and art and literary critic; son-in-law of Mykhailo Drahomanov. After studying at the Cracow Academy of Fine Arts (1891-7) under Leon Wyczolkowski and Jan Stanislawski he lived in Lviv, where he was active in Ukrainian artistic circles and community life. A friend of Ivan Franko, he organized the Society for the Advancement of Ruthenian Art and the Society of Friends of Ukrainian Scholarship, Literature, and Art and their exhibitions; copublished the first Ukrainian art magazine, Artystychnyi vistnyk ; painted many portraits for the Shevchenko Scientific Society; lectured on art and literature; and contributed articles to Literaturno-naukovyi vistnyk , Dilo , and Ukrainische Rundschau . He traveled widely: he visited Kyiv several times (he taught briefly at Mykola I. Murashko's Kyiv Drawing School in 1901), Crimea (1901-4), Italy (1902, 1908), and Egypt and Palestine (1912). Trush was an impressionist, noted for his original use of color. A major part of his large legacy (over 6,000 paintings) consists of landscapes...

MYKHAILIV, YUKHYM, b 27 October 1885 in Oleshky, Tavriia gubernia, d 15 July 1935 in Kotlas, Arkhangelsk oblast, RSFSR. Symbolist painter, graphic artist, and art scholar. He studied in Moscow at the Stroganov Applied Arts School (1902-6) and the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture (1906-10). In the 1910s he began contributing poetry to Ukrainian journals and designing book and magazine covers and illustrations. From 1917 he lived in Kyiv, where he was active in the Ukrainian Scientific Society, directed an arts and crafts school (from 1923), and headed the All-Ukrainian Committee for the Preservation of Monuments of Antiquity and Art, the Leontovych Music Society (1921-4), and the Kyiv branch of the Association of Artists of Red Ukraine. Mykhailiv painted or drew over 300 works. Among them there are three prominent themes: the Ukrainian national revival, the Ukrainian past, and death. Mykhailiv was arrested in 1934 by the NKVD and exiled to the Soviet Arctic, where he died. A book about him (ed Yu. Chaplenko), with reproductions of his works, was published in New York in 1988...

HRYSHCHENKO, OLEKSA, b 2 April 1883 in Krolevets, Chernihiv gubernia, d 28 January 1977 in Vence, France. Modernist painter, art scholar, and author. While specializing in biology at Kyiv University and Moscow University, he studied painting with Serhii Svitoslavsky in Kyiv and K. Yuon in Moscow. He became involved in the modernist art movement in Russia. During a brief stay in Paris in 1911 he met A. Lhote, Alexander Archipenko, and Le Fauconnier and became interested in cubism. From 1913 to 1914 he studied in Italy and wrote several studies of Italian primitive artists and the relation between the icon and Western art. During the Revolution of 1917, Hryshchenko became professor of the State Art Studios in Moscow and was offered the directorship of the Tretiakov Gallery, but he escaped from Russia via Crimea to Turkey. From 1919 to 1921 he lived in Istanbul, where he painted hundreds of watercolors. In 1921 he moved to France. In 1927 he settled in Cagnes in southern France. By this time he had changed his cubist style to a more dynamic expressionism, distinguished by cascades of exotic oriental colors...

Defined by its subject matter rather than artistic style, works of historical painting (understood in a specific, more narrow sense of this term) depict scenes from secular history, excluding religious, mythological or allegorical subjects. This type of paiting became increasingly popular in the late 18th century in France and England, and in the 19th century historical painting developed into a distinct genre throughout Europe. Within the context of Ukrainian art, Antin Losenko, a Cossack from Hlukhiv who spent most of his creative career in western Europe and in Saint Petersburg, was the first to introduce to Eastern Europe not only the genre of historical painting, but also the subject matter from the history of the Ukrainian lands: in 1770 he painted a celebrated painting of Grand Prince of Kyivan Rus' Volodymyr the Great and his wife Rohinda. In western Ukrainian lands, in the same year 1770 Luka Dolynsky painted an important historical depiction of the Halych ruler Lev Danylovych. However, the genre of historical painting fully developed in the Ukrainian context only in the second half of the 19th century. Taras Shevchenko included many historical subjects in his drawings and graphic works. But the most significant influence on the development of Ukrainian historical painting in Russian-ruled Ukraine was exerted by the legacy of Ukrainain-born Ilia Repin. Repin's realist historical paintings, and in particular his famous canvas The Zaporozhian Cossacks Write a Letter to the Turkish Sultan (1880-91), set the standard for younger Ukrainian painters to aspire to and considerably popularized the subject matter of Cossack history. As a professor of Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts, Repin also considerably influenced many of his Ukrainian students, including Mykola Pymonenko, Fotii Krasytsky, and Semen Prokhorov, as well as other Ukrainian painters at the Academy, such as Serhii Vasylkivsky. In Austrian-ruled western Ukraine the most important painter of historical canvases after Dolynsky was Kornylo Ustyianovych. But this genre of painting found its most accomplished master in western Ukraine in the early 20th century in the person of Mykola Ivasiuk whose canvas Khmelnytsky's Entry into Kyiv (1912) became particularly popular... Learn more about the Ukrainian historical painting from classicism to realism by visiting the following entries:

Paintings depicting scenes from everyday life on the Ukrainian territories are already found in Scythian art and in the frescoes of Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv (11th century). By definition, however, genre painting is associated with European easel painting, which dates back to the late Middle Ages in the West and the 18th century in Ukraine. In the late 19th century, with the rise of the Peredvizhniki society of painters who opposed the dogmatic imitation of classical art forms promoted by Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts, genre painting came to enjoy great popularity in the Russian Empire, including Ukraine. Depicting primarily scenes from village life, the Ukrainian representatives of the Peredvizhniki, such as Kyriak Kostandi, Ilia Repin, or Mykola Pymonenko, worked in realist and naturalist styles and were more concerned with realistic portrayals than with stylistic innovation. Many other Ukrainian artists were influenced by their ideas and painted strictly realistic genre scenes, including historical scenes from the daily life of the Cossacks. As a result of their representatives' primary focus on the subject matter of their paintings, in the wake of formalist experimentation in the early 20th century, originally radical in nature, the Peredvizhniki society became a bastion of conservatism and opposed modernist trends in Ukrainian art. The naturalist styles advocated by its members were later used as the basis of Soviet socialist realism... Learn more about the Ukrainian realist genre painting by visiting the following entries:

GENRE PAINTING. A style of painting characterized by the depiction of scenes from everyday life. Ukrainian genre painting usually depicts village life. Early examples of genre painting in Ukraine include certain works by Vasilii Shternberg, Ivan Soshenko, and Taras Shevchenko. In the late 19th century, the Ukrainian representatives of the Peredvizhniki society of painters, such as Kostiantyn Trutovsky, Ilia Repin, Mykola Bodarevsky, and Mykola Pymonenko were among the more prominent genre painters. Later works depicting everyday life were painted by, among others, Porfyrii Martynovych, Ivan Izhakevych, Fotii Krasytsky, Fedir Krychevsky, Oleksander Murashko, and Anatol Petrytsky, some of whom were associated with the Peredvizhniki, and by the Western Ukrainians such as Olena Kulchytska, Ivan Trush, Mykola Ivasiuk, and Yosyp Bokshai. In the first half of the 20th century, with the influence of Western experimentalism, genre painting declined, particularly in Western Ukraine, and often appeared simply as a pretext to formal stylization, especially in graphic art. In Soviet Ukraine in the 1930s, in addition to village life, industrial themes also became popular subjects for genre painting...

PEREDVIZHNIKI. A name applied to members of the Russian Society of Itinerant Art Exhibitions. It was founded in 1870 by Ivan Kramskoi, Mykola Ge, and 13 other artists who had left the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts in protest against its rigid neoclassical dicta. In order to reach the widest audience possible, the society organized regular traveling exhibitions throughout the Russian Empire, including Kyiv, Kharkiv, and Odesa in their tours. Over the years the society attracted artists from various parts of Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine. Among the Ukrainians who joined it were Kyriak Kostandi, Arkhyp Kuindzhi, Mykola Kuznetsov, Oleksander Murashko, Leonid Pozen, Mykola Pymonenko, Petro Nilus, Ilia Repin, Serhii Svitoslavsky, and Mykola Yaroshenko. The Peredvizhniki worked in realist and naturalist styles and concentrated on landscape art, portraiture, and genre painting. In Southern Ukraine, the Society of South Russian Artists, established in Odesa in 1890, was closely associated with the Peredvizhniki. Among its founders were Kyriak Kostandi (its president from 1902 to 1921), Mykola Kuznetsov, Gennadii Ladyzhensky, and Mykola Skadovsky...

TRUTOVSKY, KOSTIANTYN, b 9 February 1826 in Kursk, d 29 March 1893 in Yakovlevka, Kursk gubernia. Ukrainian painter and graphic artist. He was raised on his family's estate in Popivka, Okhtyrka county, Kharkiv gubernia. He audited classes at the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts (1845-9) and in 1860 was elected a member of the academy. Having adopted the prevailing realist style of academism, he specialized in genre paintings depicting life in Kursk gubernia and Ukraine. They included a number of paintings of folk customs in Ukraine. Trutovsky also did hundreds of pencil drawings and illustrations, including illustrations to the Ukrainian stories of Nikolai Gogol and Marko Vovchok as well as Taras Shevchenko's poems 'Haidamaky' (Haidamakas, 1886), 'Naimychka' (The Hired Girl), and 'Nevol'nyk' (The Captive, 1887). Most of his works were within the framework of the ethnographic sentimental style fashionable at the time; some, however, touched on painful social problems. Trutovsky influenced younger painters, such as Serhii Vasylkivsky, Ivan Izhakevych, Mykola Pymonenko, and Opanas Slastion...

KOSTANDI, KYRIAK, b 3 October 1852 in Dofinivka, Odesa county, Kherson gubernia, d 31 October 1921 in Odesa. Realist painter and art scholar. After graduating from the Odesa Drawing School (1874) and the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts (1882), he returned to Odesa, where he painted and taught at the drawing school. In 1897 he joined the Peredvizhniki and began to take part in their exhibitions. Having helped found the Society of South Russian Artists, he served from 1902 to 1920 as its president. In 1907 he was elected full member of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts. From 1917 he served as director of the Odesa City Museum. Adhering to a strictly realist style, Kostandi devoted himself to genre painting, but did some landscape painting and portrait painting as well. His works include At a Friend's Sickbed (1884), Geese (1888), Early Spring (1892), Little Bright Cloud (1906), and Little Blue Cloud (1908). After his death, his style and ideas became leading principles for a group of his followers gathered in the Kostandi Society of Artists...

PYMONENKO, MYKOLA, b 9 March 1862 in Priorka (a suburb of Kyiv), d 26 March 1912 in Kyiv. Prominent Ukrainian realist painter; full member of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts from 1904. After studying at the Kyiv Drawing School (1878-82) and the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts (1882-4) he taught at the Kyiv Drawing School (1884-1900) and Kyiv Art School (1900-6). He took part in the exhibitions of the Society of South Russian Artists (1891-6) and Peredvizhniki society (from 1893) and became a member of the latter society in 1899. In 1909 he was elected a member of the Paris International Association of Arts and Literatures. Pymonenko produced over 700 genre scenes, landscapes, and portraits, many of which were reproduced as postcards. Pymonenko also created illustrations for several of Taras Shevchenko's narrative poems, and in the 1890s he took part in painting the murals in Saint Volodymyr's Cathedral in Kyiv. Books about him have been written by Yakiv Zatenatsky (1955) and P. Hovdia (1957), and an album of his works was published in Kyiv in 1983...

IZHAKEVYCH, IVAN, b 18 January 1864 in Vyshnopil, Uman county, Kyiv gubernia, d 19 January 1962 in Kyiv. Realist painter and graphic artist, one of the most popular artists in Ukraine of his time. He studied art at the Kyivan Cave Monastery Icon Painting Studio (1876-82), the Kyiv Drawing School (1882-4), and the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts (1884-8). In 1883-4 he took part in the restoration of the 12th-century frescoes in Saint Cyril's Church in Kyiv, and later painted the refectory and the All-Saints Church of the Kyivan Cave Monastery. He executed numerous landscapes, genre scenes, and paintings on historical themes. A prolific illustrator, he worked for Russian journals at the time when Ukrainian ones were forbidden, and often referred to Ukrainian themes. He did easel paintings on themes from Shevchenko's poetry and a series of illustrations and the cover for the jubilee edition of Kobzar (The Minstrel, 1940). Izhakevych also illustrated the works of Lesia Ukrainka, Nikolai Gogol, Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, Ivan Franko, Vasyl Stefanyk, and others. By style he belongs to the Populist School of the second half of the 19th century...

The preparation, editing, and display of the IEU entries associated with the Ukrainian genre painting were made possible by the financial support of the CANADIAN FOUNDATION FOR UKRAINIAN STUDIES .

An important movement in painting that arose in France in the late 1860s and is linked with artists such as Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, August Renoir, and Alfred Sisley, impressionism had a strong influence on Ukrainian painting. The first Ukrainian impressionists appeared at the end of the 19th century and were graduates of the Cracow Academy of Fine Arts. Impressionism remained a major trend in Ukrainian painting until the early 1930s and it gave rise to Neo-impressionism, which attempted to base painting on scientific theory; Postimpressionism, which cultivated the esthetics of color; and Pointillism, which broke down colors into their elementary hues and distributed them in mosaic-like patterns... Learn more about the influence of the impressionist movement on Ukrainian art and the major representatives of this style in Ukraine by visiting the following entries:

IMPRESSIONISM. The original French impressionist painters sought to capture with short strokes of unmixed pigment the play of sunlight on objects. The name of the movement was derived from Claude Monet's Impressions: Sunrise (1872). Oleksa Novakivsky, who later embraced symbolic expressionism, was one of the first Ukrainian impressionists. Ivan Trush, who preferred to work with grayed colors, adopted impressionism only partly. Mykola Burachek captured the sunbathed colors of the Ukrainian steppe, while Mykhailo Zhuk and Ivan Severyn introduced decorative elements into their impressionist works. Other leading exponents of Ukrainian impressionism were Oleksander Murashko, Vasyl Krychevsky, Petro Kholodny (landscapes and portraits), Mykola Hlushchenko, and Oleksii Shovkunenko...

OLEKSANDER MURASHKO, b 7 September 1875 in Kyiv, d 14 June 1919 in Kyiv. Painter. He studied at the Kyiv Drawing School (1891-4), under Ilia Repin at the Saint Petersburg Academy of Arts (1894-1900), and in Munich and Paris (1902�4). In 1907 he settled in Kyiv, where he taught painting at the Kyiv Art School and at his own studio. In 1909 he exhibited his canvases in Paris, Munich, and Amsterdam, and in 1910 at the international exhibition in Venice and at one-man shows in Berlin, Koln, and Dusseldorf. From 1911 he exhibited with the Munich Sezession group. In 1916 he joined the Peredvizhniki society and became a founding member of the Kyiv Society of Artists. He was a cofounder of the Ukrainian State Academy of Arts in 1917 and served there as a professor and rector. Murashko's style evolved from the realism of the Peredvizhniki school into a vivid, colorful impressionism...

KRYCHEVSKY, VASYL, b 12 January 1873 in Vorozhba, Lebedyn county, Kharkiv gubernia, d 15 November 1952 in Caracas, Venezuela. Outstanding art scholar, architect, painter, graphic artist, set designer, and a master of applied and decorative art. Working as an independent architect and artist, he achieved a national reputation by the time of the outbreak of the First World War. During the revolutionary period he was a founder and the first president of the Ukrainian State Academy of Arts. After the war he lived briefly in Paris before immigrating in 1947 to South America. As a painter Krychevsky was deeply influenced by French impressionism. The pure and harmonious colors of his south-Ukrainian landscapes or Kyiv cityscapes (done in oils and watercolors) convey a lyrical atmosphere...

BURACHEK, MYKOLA, b 16 March 1871 in Letychiv, Podilia gubernia, d 12 August 1942 in Kharkiv. Impressionist painter and pedagogue. Burachek studied in Kyiv and graduated from the Cracow Academy of Fine Arts in 1910. His first exhibit was held in 1907. In 1910-12 he worked in the studio of Henri Matisse in Paris. In 1917-22 he served as professor at the Ukrainian State Academy of Arts in Kyiv and then at the Kyiv State Art Institute and the Lysenko Music and Drama School in Kyiv. From 1925 to 1934 he was rector of the Kharkiv Art Institute and then returned to the Kyiv State Art Institute. A master landscape painter, he rendered Ukrainian landscapes in a colorful, impressionist style...

HLUSHCHENKO, MYKOLA, b 17 September 1901 in Novomoskovske, Katerynoslav gubernia, d 31 October 1977 in Kyiv. Artist. A graduate of the Academy of Art in Berlin (1924), from 1925 he worked in Paris where he immediately attracted the attention of French critics. From the Neue Sachlichkeit style of his Berlin period he changed to postimpressionism. Besides numerous French, Italian, Dutch, and (later) Ukrainian landscapes, he also painted flowers, still life, nudes, and portraits. At the beginning of the 1930s, Hlushchenko belonged to the Association of Independent Ukrainian Artists and helped organize its large exhibition of Ukrainian, French, and Italian paintings at the National Museum in Lviv. In 1936 he moved to the USSR, but was allowed to live in Ukraine only after the war...

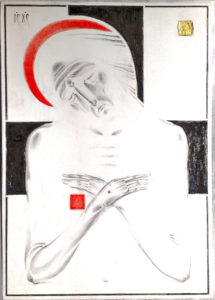

Art critics, including Guillaume Apollinaire, first took notice of Mykhailo Boichuk's art in 1910 in Paris, when he participated in exhibitions of the Salon d'Automne, and, together with his students, held an exhibition at the Salon des Independants on the theme of the revival of Byzantine art. Having witnessed the birth of modern art in Paris, Boichuk attempted to blend it with his native tradition, developing a style of simplified monumental forms inspired by traditional Byzantine and Ukrainian icon, the Italian Renaissance painting of the Quattrocento period, and the Ukrainian folk art. This style, having won high critical acclaim, became known as Boichukism. In the 1920s, its followers made up a dominant part of the membership of Association of Revolutionary Art of Ukraine, which developed a unique and powerful school of Ukrainian monumental art. However, Boichukism was often attacked by official Soviet critics for 'formalism,' 'bourgeois nationalism,' and focusing on the countryside. During the Salinist terror, Boichuk and his most prominent students and collaborators, Vasyl Sedliar, Ivan Padalka, Sofiia Nalepinska-Boichuk, and Mykola Kasperovych, were arrested by the NKVD and executed. Categorized as the 'bourgeois-nationalist art,' most of Boichuk's and his students' frescoes and paintings were destroyed by the Soviet authorities... Learn more about Mykhailo Boichuk and his school of Ukrainian monumental art by visiting the following entries:

BOICHUK, MYKHAILO, b 30 October 1882 in Romanivka, Ternopil county, d 13 July 1937 in Kyiv. Influential Ukrainian modernist painter, graphic artist, and teacher. Boichuk studied at Yuliian Pankevych's art studio in Lviv (1898), a private art school in Vienna (1899), and the Cracow Academy of Arts (1899-1905). He continued his studies in Munich, Vienna, and Paris. In 1909 he founded his own studio-school in Paris, at which his future wife Sofiia Nalepinska, Mykola Kasperovych, and other painters studied. After the Revolution of 1917 Boichuk lived in Kyiv. There he became a founding professor of the Ukrainian State Academy of Arts, taught monumental art at the academy, and was briefly its rector. In 1925 he was one of the founders of the Association of Revolutionary Art of Ukraine. Boichuk formed a school of monumental painting, which continued to develop in Ukraine into the 1930s. Arrested by the NKVD in November 1936 on the charge of being an 'agent of the Vatican,' he was executed together with his students Ivan Padalka and Vasyl Sedliar...

The early 20th-century avant-garde movement had a direct impact on Ukrainian painting. Artists born in Ukraine, as well as those who considered themselves Ukrainian by nationality, were in its vanguard and they strongly influenced the development of such avant-garde artistic trends as futurism, cubo-futurism, suprematism, and constructivism. The most prominent of them were Kazimir Malevich (the founder of suprematism), David Burliuk and Vladimir Burliuk (the founders of futurism in the Russian Empire), Alexandra Ekster (whose innovative stage and costume designs gained international renown), Oleksander Bohomazov (a master cubo-futurist), and Vladimir Tatlin (one of the founders of constructivism). The first exhibition of the new art in Ukraine (and in the Russian Empire as well) was organized in Kyiv in 1908 by Davyd and Vladimir Burliuk, Alexandra Ekster, and Oleksander Bohomazov. During the 1910s artists from Ukraine played a crucial role in the development of avant-garde artistic trends in Russia. At the same time, they had close contacts with Western avant-garde artists, particularly in France (Paris) and Germany. In fact, a group of artists from Ukraine who resided in Paris and/or Berlin, such as Alexander Archipenko, Vladimir Baranoff-Rossine, Sonia Delaunay-Terk, and Mykhailo Andriienko-Nechytailo, had a considerable impact on the evolution of the avant-garde art in Western Europe. During the relatively liberal period of the 1920s in Soviet Ukraine, a variety of styles flourished and avant-garde art was taught at Ukrainian art schools, particularly at the Kyiv State Art Institute. Cubo-futurist and constructovist art works were produced in Kyiv, Kharkiv, and other cities by such younger artists as Vasyl Yermilov, Vadym Meller, Viktor Palmov, and Anatol Petrytsky. However, in the 1930s all avant-garde activities in Soviet Ukraine came to a halt with the introduction of socialist realism as the only literary and artistic method permitted by the communist regime... Learn more about the early 20th-century Ukrainian avant-garde artists by visiting the following entries:

EKSTER, ALEXANDRA (also Exter; nee Grigorovich), b 6 January 1882 in Bialystok, Hrodna gubernia, d 17 March 1949 in Fontenay-aux-Roses near Paris, France. Avant-garde painter and theatrical set designer and costume designer working within the currents of cubism, cubo-futurism, suprematism, and constructivism. In 1906 she graduated from Kiev Art School where she studied under Mykola Pymonenko together with, among others, Oleksander Bohomazov and Alexander Archipenko. From 1908 to 1924 she intermittently lived in Kyiv, Saint Petersburg, Odesa, Paris, Rome, and Moscow, but she played a particularly important role on the Kyiv art scene. Her painting studio grouped Kyiv's artistic and intellectual elite. In Paris, Ekster was a personal friend of Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Gertrude Stein. In 1914, she participated in the Salon des Independants exhibitions together with Kazimir Malevich, Alexander Archipenko, Vadym Meller, Sonia Delaunay-Terk and other artists. Exter's early paintings featured elements of cubism, futurism (cubo-futurism), and the Art Deco movement. Later her set designs featured elements of constructivism. In general, her art absorbed influences from a variety of sources and cultures. She was particularly fascinated, however, with the Ukrainian folk art and in 1915-6 she organized the peasant craft cooperatives in the villages Skoptsi and Verbivka which produced, among others, kilims based on Kazimir Malevich's suprematist designs. Ekster brought the colourful palette of the Ukrainian folk art into thus far monochromatic cubist paintings. Proclaiming a close affinity between the avant-garde and folk art, Ekster exhibited her works together with a Ukrainian naive artist Hanna Sobachko-Shostak and other folk painters...