What Is Racism: Definition and Examples

Getty Images / FotografiaBasica

- Understanding Race & Racism

- People & Events

- Law & Politics

- The U. S. Government

- U.S. Foreign Policy

- U.S. Liberal Politics

- U.S. Conservative Politics

- Women's Issues

- Civil Liberties

- The Middle East

- Immigration

- Crime & Punishment

- Canadian Government

- Understanding Types of Government

Dictionary Definition of Racism

Sociological definition of racism, discrimination today.

- Internalized and Horizontal Racism

Reverse Racism

- M.A., English and Comparative Literary Studies, Occidental College

- B.A., English, Comparative Literature, and American Studies, Occidental College

What is racism, really? The use of the term racism has become so popular that it’s spun off related terms such as reverse racism, horizontal racism, and internalized racism .

Let’s start by examining the most basic definition of racism—the dictionary meaning. According to the American Heritage College Dictionary, racism has two meanings. This resource first defines racism as, “The belief that race accounts for differences in human character or ability and that a particular race is superior to others” and secondly as, “ Discrimination or prejudice based on race.”

Examples of the first definition abound throughout history. When enslavement was practiced in the United States, Black people were not only considered inferior to White people but also regarded as property rather than human beings. During the 1787 Philadelphia Convention, lawmakers agreed that enslaved individuals were to be considered three-fifths people for the purposes of taxation and representation. Generally speaking, during the era of enslavement, Black people were deemed intellectually inferior to White people as well. Some Americans believe this still today.

In 1994, a book called "The Bell Curve" posited that genetics were to blame for Black people traditionally scoring lower than White people on intelligence tests. The book was attacked by many including New York Times columnist Bob Herbert, who argued that social factors were responsible for the differential, and Stephen Jay Gould, who argued that the authors made conclusions unsupported by scientific research.

However, this pushback has done little to stifle racism, even in academia. In 2007, Nobel Prize-winning geneticist James Watson ignited similar controversy when he suggested that Black people were less intelligent than White people.

The sociological definition of racism is much more complex. In sociology, racism is defined as an ideology that prescribes statuses to racial groups based on perceived differences. Though races are not inherently unequal, racism forces this narrative. Genetics and biology do not support or even suggest racial inequality, contrary to what many people—often even scholars—believe. Racial discrimination, based on manufactured inequalities, is a direct product of racism that brings these notions of difference into reality. Institutional racism permits inequality in legislation, education, public health, and more. Racism is allowed to spread further through the racialization of systems that affect nearly every aspect of life, and this combined with widespread discrimination results in racism that is systemic—allowed to exist by society as a whole and internalized by a majority to some extent.

Racism creates power dynamics that follow these patterns of perceived imbalance, which are exploited in order to preserve feelings of superiority in the "dominant" race and inferiority in the "subservient" race, even to blame the victims of oppression for their own situations. Unfortunately, these victims often unwittingly play a role in the continuation of racism. Scholar Karen Pyke points out that "all systems of inequality are maintained and reproduced, in part, through their internalization by the oppressed." Even though racial groups are equal at the most basic level, groups assigned lesser statuses are oppressed and treated as though they are not equal because they are perceived not to be. Even when subconsciously held, these beliefs serve to further divide racial groups from one another. Radical versions of racism such as white supremacy make overt the unspoken ideologies within racism: that certain races are superior to others and should be allowed to hold more societal power.

Racism persists in modern society, often taking the form of discrimination. Case in point: Black unemployment has consistently soared above White unemployment for decades. Why? Numerous studies indicate that racism advantaging White people at the expense of Black people contributes to unemployment gaps between races.

For example, in 2003, researchers at the University of Chicago and MIT released a study involving 5,000 fake resumes, finding that 10% of resumes featuring “Caucasian-sounding” names were called back compared to just 6.7% of resumes featuring “Black-sounding” names. Moreover, resumes featuring names such as Tamika and Aisha were called back just 5% and 2% of the time. The skill level of the faux Black candidates made no impact on callback rates.

Internalized Racism and Horizontal Racism

Internalized racism is not always or even usually seen as a person from a racial group in power believing subconsciously that they are better than people of other races. It can often be seen as a person from a marginalized group believing, perhaps unconsciously, that White people are superior.

A highly publicized example of this is a 1940 study devised by Dr. Kenneth and Mamie to pinpoint the negative psychological effects of segregation on young Black children. Given the choice between dolls completely identical in every way except for their color, Black children disproportionately chose dolls with white skin, often even going so far as to refer to the dark-skinned dolls with derision and epithets.

In 2005, teen filmmaker Kiri Davis conducted a similar study, finding that 64% of Black girls interviewed preferred White dolls. The girls attributed physical traits associated with White people, such as straighter hair, with being more desirable than traits associated with Black people.

Horizontal racism occurs when members of minority groups adopt racist attitudes toward other minority groups. An example of this would be if a Japanese American prejudged a Mexican American based on the racist stereotypes of Latinos found in mainstream culture.

“Reverse racism” refers to supposed anti-White discrimination. This term is often used in conjunction with practices designed to help people of color, such as affirmative action .

To be clear, reverse racism does not exist. It’s also worth noting that in response to living in a racially stratified society, Black people sometimes complain about White people. Typically, such complaints are used as coping mechanisms for withstanding racism, not as a means of placing White people into the subservient position Black people have been forced to occupy. And even when people of color express or practice prejudice against White people, they lack the institutional power to adversely affect the lives of White people.

- Bertrand, Marianne, and Sendhil Mullainathan. " Are Emily and Greg More Employable Than Lakisha and Jamal? A Field Experiment on Labor Market Discrimination ." American Economic Review , vol. 94, no. 4, Sep. 2004, pp. 991–1013, doi:10.1257/0002828042002561

- Clair, Matthew, and Jeffrey S. Denis. " Sociology of Racism ." The International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences , 2015, pp. 857–863, doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.32122-5

- Pyke, Karen D. " What Is Internalized Racial Oppression and Why Don't We Study It? Acknowledging Racism's Hidden Injuries ." Sociological Perspectives , vol. 53, no. 4, Dec. 2010, pp. 551–572, doi:10.1525/sop.2010.53.4.551

- Racial Bias and Discrimination: From Colorism to Racial Profiling

- How to Tell If You've Been Unintentionally Racist

- 5 Big Companies Sued for Racial Discrimination

- The Sociology of Race and Ethnicity

- Understanding 4 Different Types of Racism

- How W.E.B. Du Bois Made His Mark on Sociology

- How Intervening Variables Work in Sociology

- Biography of W.E.B. Du Bois, Black Activist and Scholar

- 5 Common Misconceptions About Black Lives Matter

- Biography of Patricia Hill Collins, Esteemed Sociologist

- Black History Timeline: 1930–1939

- How to Respond to Discrimination During a Job Interview

- Combahee River Collective in the 1970s

- Does Reverse Racism Exist?

- What Is a Literacy Test?

- Understanding Jim Crow Laws

Racism: What it is, how it affects us and why it’s everyone’s job to do something about it

Bray lecturer Camara Jones addresses racism as a public health crisis

- Post author By Kathryn

- Post date October 5, 2020

By Kathryn Stroppel

In 2018, the CDC found a 16% difference in the mortality rates of Blacks versus whites across all ages and causes of death. This means that white Americans can sometimes live more than a decade longer than Blacks.

In 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the discrepancy in health outcomes has only grown. Michigan’s population, for instance, is 14% Black, yet near the start of the pandemic, African Americans made up 35% of cases and 40% of deaths.

Because of this discrepancy in health outcomes, many scientists and government officials, including former American Public Health Association President Camara Jones, MD, PhD, MPH ; more than 50 municipalities nationwide; and a handful of legislators are attempting to root out this inequality and call it what it is: A public health crisis.

Dr. Jones, a nationally sought-after speaker and the college’s 2020 Bray Health Leadership Lecturer, has been engaged in this work for decades and says the time to act is now.

“The seductiveness of racism denial is so strong that if people just say a thing, six months from now they may forget why they said it. But if we start acting, we won’t forget why we’re acting,” she says. “That’s why it’s important right now to move beyond just naming something or putting out a statement making a declaration, but to actually engage in some kind of action.”

Synergies editor Kathryn Stroppel talked with Dr. Jones about this unique time in history, her work, racism’s effects on health and well-being, and what we can all do about it.

Let’s start with definitions. What is racism and why is important to acknowledge ‘systemic’ racism in particular?

“Racism is a system of structuring opportunity and assigning value based on the social interpretation of how one looks, which is what we call race, that unfairly disadvantages some individuals and communities, unfairly advantages other individuals and communities and saps the strength of the whole society through the waste of human resources.

“The reason that people are using those words ‘systemic’ or ‘structural racism’ is that sometimes if you say the word racism, people think you’re talking about an individual character flaw, or a personal moral failing, when in fact racism is a system.

“It’s not about trying to divide the room into who’s racist and who’s not. I am clear that the most profound impacts of racism happen without bias.

“The most profound impacts of racism are because structural racism has been institutionalized in our laws, customs and background norms. It does not require an identifiable perpetrator. And it most often manifests as inaction in the face of need.”

Why did you want to give the 2020 Bray Lecture?

“I’ve been doing this work for decades, and all of a sudden, now that we are recognizing the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color, and after the murder of George Floyd and all of the other highly publicized murders that have been happening, more and more people are interested in naming racism and asking how is racism is operating here and organizing and strategizing to act. I wish I could accept every invitation.”

What do you hope people take away from your lecture?

“When I was president of the American Public Health Association in 2016, I launched a national campaign against racism with three tasks: To name racism; to ask, ‘how is racism operating here?’; and then to organize and strategize to act.

“Naming racism is urgently important, especially in the context of widespread denial that racism exists. We have to say the word ‘racism’ to acknowledge that it exists, that it’s real and that it has profoundly negative impacts on the health and well-being of the nation.

“We have to be able to put together the words ‘systemic racism’ and ‘structural racism’ to able to be able to affirm that Black lives matter. That’s important and necessary, but insufficient.

“I then equip people with tools to address how racism operates by looking at the elements of decision making, which are in our structures, policies, practices, norms and values, and the who, what, when and where of decision making, especially who’s at the table and who’s not.

“After you have acknowledged that the problem exists, after you have some kind of understanding of what piece of it is in your wheelhouse and what lever you can pull, or who you know, you organize, strategize and collectively act.”

You’re known for using allegory to explain racism. Why is that?

“I use allegory because that’s how I see the world. There are two parts to it. One is that I’m observant. If I see something and if it makes me go, ‘Hmm,’ I just sort of store that away. And the second part is that I am a teacher. I’ve been telling a gardening allegory since before I started teaching at Harvard, but I later expanded that in order to help people understand how to contextualize the three levels of racism.

“As an assistant professor at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, I developed its first course on race and racism. As I’m teaching students and trying to help them understand different elements, different aspects of race, racism and anti-racism, I found myself using these images naturally just to explain things, and then I recognized that allegory is sort of a superpower.

“It makes conversations that might be otherwise difficult more accessible because we’re not talking about racism between you and me, we’re talking about these two flower pots and the pink and red seed, or we’re talking about an open or closed sign, or we’re talking about a conveyor belt or a cement factory. And so I put the image out there to suggest the ways that it can help us understand issues of race and racism. And then other people add to it or question certain parts and it becomes our collective image and our tool, not just mine.”

What should white people in particular see as their role and responsibility in this system?

“All of us need to recognize that racism exists, that it’s a system, that it saps the strength of the whole society through the waste of human resources, and that we can do something about it. White people in particular have to recognize that acknowledging their privilege is important – that your very being gives you the benefit of the doubt.

“White people who don’t want to walk around oblivious to their privilege or benefit from a racist society need to understand how to use their white privilege for the struggle.”

“An example: About six years ago now, in McKinney, Texas, outside of Dallas, we came to know that there was a group of pre-teens who wanted to celebrate a birthday at a neighborhood swimming pool. The people who were at the pool objected to them being there and called the police. And what we saw was a white police officer dragging a young Black girl by her hair, and then he sat on her, and the young Black boys were handcuffed sitting on the curb.

“The next day on TV, I heard a young white boy who was part of the friend group saying it was almost as if he were invisible to the police. He saw what was happening to his friends and he could have run home for safety, but instead, he recognized his white skin privilege. He stood up and videotaped all that was going on.

“So, the thing is not to deny your white skin privilege or try to shed it, the thing is to recognize it and use it. Then as you’re using it, don’t think of yourself as an ally. Think of yourself as a compatriot in the struggle to dismantle racism. We have to recognize that if you’re white, your anti-racist struggle is not for ‘them.’ It’s for all of us.”

Why did you transition from medicine to public health?

“Because there’s a difference between a narrow focus on the individual and a population-based approach. I started as a family physician, but then wanted to do public health because it made me sad to fix my patients up and then send them back out into the conditions that made them sick.

“I wanted to broaden my approach and really understand those conditions that make people sick or keep them well. From there, the data doesn’t necessarily turn into policy. So, I sort of went into the policy aspect of things. And then you recognize that you can have all the policy you want, but sometimes the policy is not enacted by politicians. So now I am considering maybe moving into politics.”

Speaking of politics, when engaging in discussions around racism and privilege, people will sometimes try to shut down the conversation for being ‘political.’ Is racism political?

“Racism exists. It’s foundational in our nation’s history. It continues to have profoundly negative impacts on the health and well-being of the nation. To describe what is happening is not political. If people want to deny what exists, then maybe they have political reasons for doing that.”

What are your thoughts on COVID-19 and our country’s approach to dealing with the virus?

“The way we’ve dealt with COVID-19 is a very medical care approach. We need to have a population view where you do random samples of people you identify as asymptomatic as well as symptomatic.

“When you have a narrow medical approach to testing, you can document the course of the pandemic, but you can’t do anything to change it.

“With a population-based approach we already know how to stop this pandemic: It’s stay-at-home orders, mask wearing, hand washing and social distancing.

“This very seductive, narrow focus on the individual is making us scoff at public health strategies that we could put in place and is hamstringing us in terms of appropriate responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“In terms of race, COVID-19 is unmasking the deep disinvestment in our communities, the historical injustices and the impact of residential segregation. This is the time to name racism as the cause of those things. The overrepresentation of people of color in poverty and white people in wealth is not happenstance.”

We have work to do. Learn how the college is transforming academia for equity .

- Tags COVID , Public Health

SCAM ALERT: We will never contact you requesting money. Learn more.

What is racism.

Racism is the process by which systems and policies, actions and attitudes create inequitable opportunities and outcomes for people based on race. Racism is more than just prejudice in thought or action. It occurs when this prejudice – whether individual or institutional – is accompanied by the power to discriminate against, oppress or limit the rights of others.

Race and racism have been central to the organisation of Australian society since European colonisation began in 1788. As the First Peoples of Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have borne the brunt of European colonisation and have a unique experience of racism. The process of colonisation, and the beliefs that underpin it, continue to shape Australian society today.

Racism adapts and changes over time, and can impact different communities in different ways, with racism towards different groups intensifying in different historical moments. An example of this is the spike in racism towards Asian and Asian-Australian people during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Racism includes all the laws, policies, ideologies and barriers that prevent people from experiencing justice, dignity, and equity because of their racial identity. It can come in the form of harassment, abuse or humiliation, violence or intimidating behaviour. However, racism also exists in systems and institutions that operate in ways that lead to inequity and injustice.

The Racism. It Stops With Me website contains a list of ' Key terms ' that unpack some of the different ways that racism is expressed.

Read more: https://itstopswithme.humanrights.gov.au/commit-to-learning

Essays and Commentary

Reflections and analysis inspired by the killing of George Floyd and the nationwide wave of protests that followed.

My Mother’s Dreams for Her Son, and All Black Children

She longed for black people in America not to be forever refugees—confined by borders that they did not create and by a penal system that killed them before they died.

By Hilton Als

June 21, 2020

How do we change america.

The quest to transform this country cannot be limited to challenging its brutal police alone.

By Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor

June 8, 2020

The purpose of a house.

For my daughters, the pandemic was a relief from race-related stress at school. Then George Floyd was killed.

By Emily Bernard

June 25, 2020

The players’ revolt against racism, inequality, and police terror.

A group of athletes across various American professional sports have communicated the fear, frustration, and anger of most of Black America.

September 9, 2020, until black women are free, none of us will be free.

Barbara Smith and the Black feminist visionaries of the Combahee River Collective.

July 20, 2020, john lewis’s legacy and america’s redemption.

The civil-rights leader, who died Friday, acknowledged the darkest chapters of the country’s history, yet insisted that change was always possible.

By David Remnick

July 18, 2020

Europe in 1989, america in 2020, and the death of the lost cause.

A whole vision of history seems to be leaving the stage.

By David W. Blight

July 1, 2020

The messy politics of black voices—and “black voice”—in american animation.

Cartoons have often been considered exempt from the country’s prejudices. In fact, they form a genre built on the marble and mud of racial signification.

By Lauren Michele Jackson

June 30, 2020

After george floyd and juneteenth.

What’s ahead for the movement, the election, and the protesters?

June 20, 2020, juneteenth and the meaning of freedom.

Emancipation is a marker of progress for white Americans, not black ones.

By Jelani Cobb

June 19, 2020

A memory of solidarity day, on juneteenth, 1968.

The public outpouring over racism that has been taking place in America since George Floyd’s murder feels like a long-postponed renewal of the reckoning that shook the nation more than half a century ago.

By Jon Lee Anderson

June 18, 2020

Seeing police brutality then and now.

We still haven’t fully recognized the art made by twentieth-century black artists.

By Nell Painter

The History of the “Riot” Report

How government commissions became alibis for inaction.

By Jill Lepore

June 15, 2020

The trayvon generation.

For Solo, Simon, Robel, Maurice, Cameron, and Sekou.

By Elizabeth Alexander

So Brutal a Death

Nationwide outrage over George Floyd’s brutal killing by police officers resonates with immigrants, and with people around the world.

By Edwidge Danticat

An American Spring of Reckoning

In death, George Floyd’s name has become a metaphor for the stacked inequities of the society that produced them.

June 14, 2020, the mimetic power of d.c.’s black lives matter mural.

The pavement itself has become part of the protest.

By Kyle Chayka

June 9, 2020

Donald trump’s fascist performance.

To the President, power sounds like gunfire and helicopters; it sounds like the silence of men in uniform when they are asked who they are.

By Masha Gessen

June 3, 2020

- Books & Culture

- Fiction & Poetry

- Humor & Cartoons

- Puzzles & Games

Structural racism: what it is and how it works

Professor of Race and Education and Director of the Centre for Race, Education and Decoloniality in the Carnegie School of Education, Leeds Beckett University

Disclosure statement

Acknowledgement: My thanks to Professor David Gillborn for his guidance and suppport with this article.

Leeds Beckett University provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

From the moment it was published, the UK’s Commission on Racial and Ethnic Disparities’ report was met with a media storm driven by both its supporters and detractors. Months later, amid continued division over the report’s position that racism isn’t pronounced in the UK, there’s still some confusion about what exactly some of the report’s buzzwords mean.

The terms “structural racism” and “institutional racism” are among many of the concepts that have been mentioned in relation to the report’s position on whether or not racism is ingrained in the UK.

But assessing the truth behind the Commission’s suggestion that these forms of racism aren’t factors in driving racial inequality first requires decoding these terms.

Structural and institutional racism

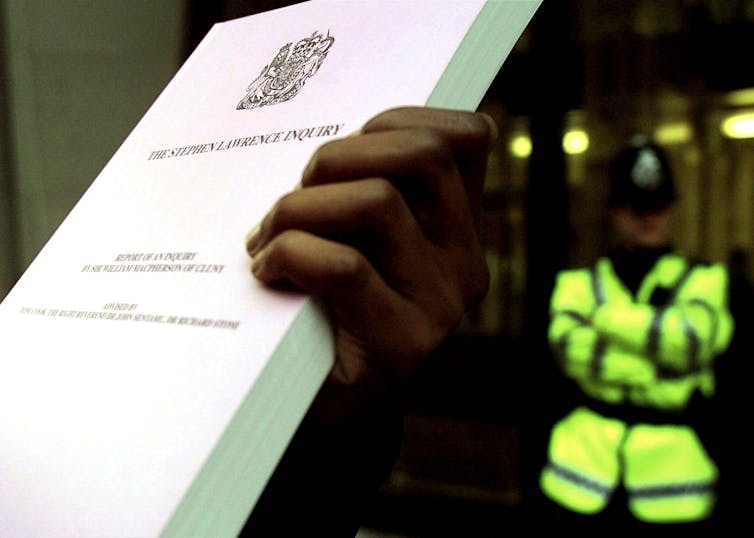

Defined initially by political activists Stokely Carmichael and Charles Vernon Hamilton in 1967, the concept of institutional racism came into the public sphere in 1999 through the Macpherson Inquiry into the racist murder of Black teenager Stephen Lawrence.

Institutional racism is defined as: “processes, attitudes and behaviour(s) which amount to discrimination through unwitting prejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness and racist stereotyping which disadvantage minority ethnic people”.

As Sir William Macpherson, head of the Stephen Lawrence Inquiry, wrote at the time, it “persists because of the failure … to recognise and address its existence and causes by policy, example and leadership”.

Institutional and structural racism work hand in glove. Institutional racism relates to, for example, the institutions of education, criminal justice and health. Examples of institutional racism can include: actions (or inaction) within organisations such as the Home Office and the Windrush Scandal ; a school’s hair policy ; institutional processes such as stop and search, which discriminate against certain groups.

Structural racism refers to wider political and social disadvantages within society, such as higher rates of poverty for Black and Pakistani groups or high rates of death from COVID-19 among people of colour .

In plain terms, structural racism shapes and affects the lives, wellbeing and life chances of people of colour. It normalises historical, cultural and institutional practices that benefit white people and disadvantage people of colour. It also stealthily replicates the racial hierarchy established more than 400 years ago through slavery and colonialism, placing white people at the top and Black people at the bottom.

Read more: Learning about white privilege isn't harmful to white working class children – viewpoint

Structural racism is enforced through institutional systems like seemingly neutral recruitment policies, which lead to the exclusion of people of colour from organisations, positions of power and social prominence. It exists because of white supremacy : a pattern of beliefs, assumptions and behaviours which advance the interests of white people and influences decision-making to maintain their dominance.

White supremacy lies at the heart of how systems in society work. It’s the main reason behind inequalities such as the ethnic pay gap across many institutions, as well as fewer judges and university vice chancellors of colour.

How does structural racism work?

Structural racism exists in the social, economic, educational, and political systems in society. Many of the issues that come with it have been escalated by the pandemic, including the disproportionate deaths of people of colour from COVID-19.

These challenges have worsened because of existing structural racial inequalities which mean that Black and Pakistani communities are more likely to work in unskilled jobs . As a result, many have had to work through the pandemic as key workers, increasing their exposure and susceptibility to catching or dying from the virus.

In fact, large numbers of health workers of colour reported being too afraid to complain about the issues they faced, with some being “bullied and shamed” into seeing patients, despite having no PPE. Their exposure to these inequalities can’t be blamed on pessimism or class or culture, but the structures within which they worked.

Structural and institutional racism account for under-representation in many fields. These barriers are responsible for everything from the 4.9% ethnic pay gap between white medical consultants and medical consultants of colour, a lack of teachers of colour in schools , the 1% of Black professors in universities and the absence of medical training about skin conditions and how they present on black and brown skin. The examples are endless.

It would be easy to blame the people affected, but that would ignore how structural racism works. Black people, for example, can work exceptionally hard but still encounter significant barriers that can be directly traced to issues of structural racism.

It’s also tempting to believe that the success of a small selection of people of colour means that the same opportunities are available to all. The suggestion being that these gains are evidence of a meritocracy (the idea that people can gain power or success through hard work alone). But this ignores the invisible hurdles that on average make the likelihood of achievement for various communities of colour much slimmer than for white people.

Critical Race Theory (a concept devised by US legal scholars which explains that racism is so endemic in society that it can feel non-existent to those who aren’t targets of it) also debunks the idea that we live in a meritocracy . It describes meritocracy as a liberal construct designed to conceal the barriers which impede success for people of colour.

If structural and institutional racism can’t be explained away by the idea that people of colour simply don’t work hard enough, or are “overly pessimistic” about race, it’s apparent that society needs alternative solutions. One of which is accepting not only that racism exists, but that it’s much more far-reaching than it seems to white people. We can’t eradicate these forms of racism without courage, commitment and concerted efforts from those in positions of power, which in the UK especially includes action from the white majority.

- Discrimination

- Institutional racism

- Stephen Lawrence

- Structural racism

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Initiative Tech Lead, Digital Products COE

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

School of Social Sciences – Public Policy and International Relations opportunities

WELCOME TO THE FAMILY! Please check your email for confirmation from us.

Defining racism and white supremacy

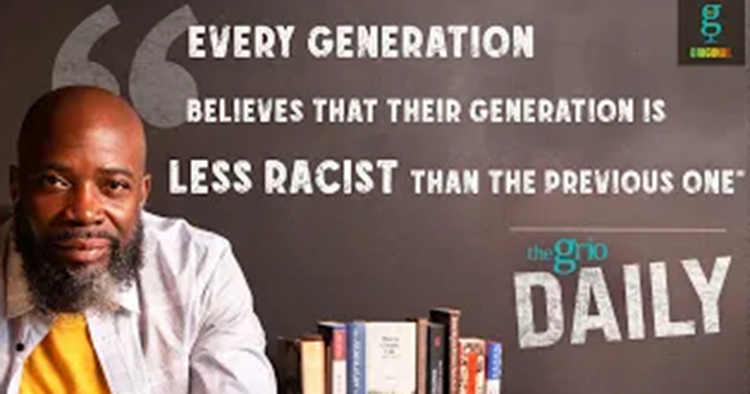

“Every generation believes that their generation is less racist than the previous one.” With the help of our dear friend Ms. “Merriam Webster,” Michael Harriot breaks down the definition of racism and white supremacy. He gets to the bottom and delivers a message you won’t hear anywhere else.

Music Courtesy of Transitions Music Corporation

You are now listening to theGrio’s Black Podcast Network, Black Culture Amplified.

Michael Harriot [00:00:05] Hello, I’m Michael Harriot world famous wypipologist and this is theGrio Daily, the only podcast that doesn’t use a measuring cup when we make Kool-Aid. No, we pour the sugar into the pitcher until the ancestors speak to our hearts and tell us to stop. And we’ll be here every morning giving you the rundown of the things that you need to know to get you through the day. Think of this as your own special Griot, helping you decipher what’s going on in the village.

Michael Harriot [00:00:36] I’m Michael Harriot, and this is theGrio Daily. And one of the things you’ll find out about this podcast is I really actually do study wypipo. For years, I taught a university class called Race as an Economic Construct, from where we examine race using data, history and economic theory. And I used to do so my first day of class. One of the first things I used to do is I used to ask people what the definition of racism is. And, you know, people had all kinds of things. They say, you know, it’s when you hate Black people or when you don’t like somebody because of their race or when you’ve got a prejudice against somebody. But, we’re going to be talking about racism a lot on this podcast. So if we’re going to do that, we’re going to have to have an exact definition. We’re going to have to understand exactly what it is and come to some kind of agreement. So I know you’re going to find it hard to believe, but there are these books that have words in them and the words define other words. It’s called a dictionary. I’m serious for like I don’t care if you don’t believe me. I swear you have seen like two or three of them. So when I defined racism, I like to go to an objective source. And my favorite source, you know, my favorite dictionary is my girl, Merriam Webster. Like, you know, that just sounds like a Black woman who’s cool as hell to me. Right. So let’s let Merriam Webster explain what racism is.

Merriam Webster [00:02:17] Hey, y’all. Is your girl Merriam Webster. And I’m here with a dope definition. Today’s word is racism. Now, racism is a belief that race is the fundamental determinant of human traits and capacities. It says that racial differences produce an inherent superiority of a particular race. It’s also behavior or attitudes that reflect and foster this belief. It’s the systemic oppression of the racial group to the social, economic and political advantage of another. Hmm. The more you know, the more you grow.

Michael Harriot [00:03:11] Yeah. That’s my homegirl, Merriam. See and she’s right. See, a lot of people think that racism is about hate or it has something to do with what’s in your head. But according to people who define things, racism doesn’t require you to hate people. It doesn’t exclude people who say one of their best friends is Black. Or I dated a Black guy in college. You can still be racist if you dated a Black guy in college. You could still be racist if you raised Black kids or if you married a Black guy who got some side babies. You can still be racist if you’re brother in law’s Uncle’s sister, cousin, nephew adopted a Black baby. None of that excludes you from the subset of people who are racist. Racism is the product of that belief, and I know that conflicts with what a lot of people believe. For instance, every generation believes that their generation is less racist than the previous one. Like we think, like, young people are going to stamp out racism and the next generation is going to be racism free. But that’s not actually true. How do I know? Because first of all, everybody’s been saying it since like time began and there’s actually data on this. See, for years, the National Opinion Research Center, or what we call the NORC, not, N.O.R.E, that’s N.O.R.E .You know, he got a good podcast, you should check it out.

Merriam Webster [00:04:28] But the NORC has been doing a survey like this really huge survey, one of the biggest in the world since 1941. And one of the cool things about the NORC is that they asked the same questions every year. Right. They have a subset of questions that they ask every year so they can track and see how people in each generation perceive society. And every year they ask people, white and Black, if Black people are less intelligent than whites, they don’t ask them, What do you believe? They just ask, Hey, are Black people less intelligent than wypipo? About 23% of white millennials believe that Black people are less intelligent or wypipo. In fact, over the last century, no matter what era they were born in, about one in three wypipo think that Black people are lazier than whites. And I don’t even know where they got that from because they said, Oh, I forgot why people don’t know history. Right. Because they don’t know about all that free labor they got. But. This actually fits the definition of racism, and it’s how white supremacy works. Now, I know what you’re saying, but white supremacy, that’s like racism or steroids, right? Well, again. We’re going to use that little book that we were talking about earlier called the Dictionary. And actually, white supremacy is not very much different to racism, even though we think it’s like supercharged racism, like Super Saiyan racism. No, it’s not really that. But don’t take my word for it. Let’s ask my girl, Merriam, like where Merriam at? She probably know.

Merriam Webster [00:06:14] Today’s word is white supremacy. The belief that the white race is inherently superior to other races and that wypipo should have control over people of other races and 2. The social, economic and political systems that collectively enable wypipo to maintain power over people of other races. Now, I tuck that one under your fitted and your bonnets.

Michael Harriot [00:06:50] So according to the actual dictionary, America isn’t technically a racist country. It’s a white supremacist one. And if you go back to like the first definition of racism that we were talking about a few seconds ago, white supremacy is really just a tool that enables wypipo to oppress other racial groups. For, again, remember that definition. Remember. Ya’ll ain’t forgot what my girl Merriam said that quick, right? The social, political and economic advantage of wypipo. And like racism, white supremacy doesn’t require intent. It doesn’t require hate. It doesn’t require people to come and burn a cross on your lawn or to have a swastika on their arm. No, white supremacy is just a method of control. Which also brings up a question. Right. And I know we’ve asked this question before. Can Black people be racist? Now, I know you’ve heard that racism must come with some kind of power, and a lot of people believe that. But, you know, my girl, Merriam, don’t have nothing about power by definition. But here’s the thing. Can you name one place in America or one situation where Black people have oppressed wypipo to the systemic, political, social or economic advantage of the rest of Black people? Sure. I did. Individual instances of Black people attacking or disliking wypipo. But that doesn’t reveal what those Black people believe. Right? That’s just the thing that they are doing. Like when you jump on a white person because of their race is just that white person. And, you know, a wypipo say God knows what’s in their heart. So unless a Black person admits that their belief is racist, all we can judge people by or their actions. And yes, there are individual instances of Black people actually committing acts of discrimination or prejudice and hate against wypipo. But it’s not systemic. Nor, again, does it give Black people in general a social, economic or political advantage.

Michael Harriot [00:09:04] So as you can see, it’s not the action of a person or the belief alone that makes them racist. It must reflect some kind of systemic or institutional effect according to definitions. For instance, when one Black person hires a Black person over a white person, it doesn’t negate the fact that Black unemployment has been twice as high as white unemployment since they began measuring the unemployment rate. In fact, when Black employees look at resumes, they are more likely to hire someone if they think the applicant is white. So the only way that Black people are technically racist is against Black people. But we’ve met Candace Owens. Or like when wypipo claim Black people voted for Obama because he was Black, they said it was racist white. But that didn’t negate the fact that Black people vote for wypipo most of the time. Right now, I don’t believe all of the founding fathers hated Black people, but they created an electoral college, a constitution and laws that still collectively enabled wypipo to maintain a political advantage over Black people. Banks still have beliefs, but the financial industry created a system that gives wypipo an economic advantage. High schools and colleges might want more Black students. They might not hate Black students. But they adhere to a system of funding, teaching, testing and admissions that gives wypipo a social advantage over Black people.

Ibram X. Kendi [00:10:46] Currently in most intelligence or tests, Latinos and Black people receive lower scores than than whites and Asians. The question is, is what is the problem? Is there a problem with the test takers or the test? And for 100 years, Americans have made the case that Black people or Latino people are not achieving intellectually as much as as other people, as much as wypipo. And I would argue, you know, the problem is with these test takers, the problem is with the test themselves.

Michael Harriot [00:11:20] So America ain’t racist. It’s a white supremacist country. Maybe I should tell you the story. So back in the days like before I graduated from grad school, I got this job at a boat company. Now, this boat company was in my hometown. The owner came to me one day and he asked me why there was this perception in town that his company was racist. So to understand why, I’ll have to give you some background. See, my town was about half Black and half white, and he had, for most of my youth, a Black high school and a white high school. Right. But the white High School had this program, it was funded by this man’s company, and when you finished high school, you learned how to make boats. And you automatically, if you graduated from that program, got a job at this company. Now, that program didn’t exist at the Black High School. It doesn’t matter why, right. It doesn’t matter whether he did it because it was his alma mater or he couldn’t afford tools, so he just arbitrarily picked one high school. But his company had created a social, economic and political system that collectively enabled wypipo to maintain power over people of other races. That is white supremacy. They could get a job simply because of the fact that they went to the white High School. And that’s white supremacy.

Michael Harriot [00:12:57] So if somebody calls you a white supremacist and it fits that definition, don’t be mad at me. Don’t be mad at my girl Merriam. Be mad at the dictionary, because actually words mean things. Now we got to get out of here. But don’t forget to download theGrio app. Don’t forget to subscribe on your favorite platform. And don’t forget to tell at least one person about theGrio Daily. But we’ll get out of here. In the Black is way possible with a traditional Black greeting. “Tell your mama them I said ‘Hey’.” Thank you for listening to theGrio Daily. If you like what you heard, please give us a five star review. Download theGrio app, subscribe to the show and share it with everyone you know. Please email all questions, suggestions and compliments to podcasts at theGrio dot com.

[00:13:53] You are now listening to theGrio’s Black Podcast Network, Black Culture Amplified.

Dr. Christina Greer [00:13:59] You’re watching The Blackest Questions podcast with Christina Greer. And this podcast we ask our guests five of the Blackest questions so we can learn a little bit more about them and have some fun while we’re doing it.

Guest [00:14:11] Okay, so this is a trick question.

Dr. Christina Greer [00:14:13] We’re also going to learn a lot about Black history, past and present.

Guest [00:14:17] ‘Beautiful I learned a wonderful fact today. Great.

Dr. Christina Greer [00:14:19] So here’s how it works. We have five rounds of questions about Black history, the whole diaspora, current events, you name it. With each round, the questions get a little tougher.

Guest [00:14:30] Oh, you got me. You got me. Let me see. Let me see, let me see.

Guest [00:14:33] I have no idea.

Guest [00:14:34] I knew you were going to go there, Dr. Greer.

Dr. Christina Greer [00:14:35] Subscribe to the show wherever you listen to your podcast and share it with everyone you know.

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share via Email

- Copy Link Link Copied

STREAM FREE MOVIES, LIFESTYLE AND NEWS CONTENT ON OUR NEW APP

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

Become an FT subscriber

Limited time offer save up to 40% on standard digital.

- Global news & analysis

- Expert opinion

- Special features

- FirstFT newsletter

- Videos & Podcasts

- Android & iOS app

- FT Edit app

- 10 gift articles per month

Explore more offers.

Standard digital.

- FT Digital Edition

Premium Digital

Print + premium digital.

Then $75 per month. Complete digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Cancel anytime during your trial.

- 10 additional gift articles per month

- Global news & analysis

- Exclusive FT analysis

- Videos & Podcasts

- FT App on Android & iOS

- Everything in Standard Digital

- Premium newsletters

- Weekday Print Edition

Complete digital access to quality FT journalism with expert analysis from industry leaders. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- Everything in Print

- Everything in Premium Digital

The new FT Digital Edition: today’s FT, cover to cover on any device. This subscription does not include access to ft.com or the FT App.

Terms & Conditions apply

Explore our full range of subscriptions.

Why the ft.

See why over a million readers pay to read the Financial Times.

International Edition

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

The A.C.L.U. Said a Worker Used Racist Tropes and Fired Her. But Did She?

The civil liberties group is defending itself in an unusual case that weighs what kind of language may be evidence of bias against Black people.

By Jeremy W. Peters

Kate Oh was no one’s idea of a get-along-to-go-along employee.

During her five years as a lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union, she was an unsparing critic of her superiors, known for sending long, blistering emails to human resources complaining about what she described as a hostile workplace.

She considered herself a whistle blower and advocate for other women in the office, drawing unflattering attention to an environment she said was rife with sexism, burdened by unmanageable workloads and stymied by a fear-based culture.

Then the tables turned, and Ms. Oh was the one slapped with an accusation of serious misconduct. The A.C.L.U. said her complaints about several superiors — all of whom were Black — used “racist stereotypes.” She was fired in May 2022.

The A.C.L.U. acknowledges that Ms. Oh, who is Korean American, never used any kind of racial slur. But the group says that her use of certain phrases and words demonstrated a pattern of willful anti-Black animus.

In one instance, according to court documents, she told a Black superior that she was “afraid” to talk with him. In another, she told a manager that their conversation was “chastising.” And in a meeting, she repeated a satirical phrase likening her bosses’ behavior to suffering “beatings.”

Did her language add up to racism? Or was she just speaking harshly about bosses who happened to be Black? That question is the subject of an unusual unfair-labor-practice case brought against the A.C.L.U. by the National Labor Relations Board, which has accused the organization of retaliating against Ms. Oh.

A trial in the case wrapped up this week in Washington, and a judge is expected to decide in the next few months whether the A.C.L.U. was justified in terminating her.

If the A.C.L.U. loses, it could be ordered to reinstate her or pay restitution.

The heart of the A.C.L.U.’s defense — arguing for an expansive definition of what constitutes racist or racially coded speech — has struck some labor and free-speech lawyers as peculiar, since the organization has traditionally protected the right to free expression, operating on the principle that it may not like what someone says, but will fight for the right to say it.

The case raises some intriguing questions about the wide swath of employee behavior and speech that labor law protects — and how the nation’s pre-eminent civil rights organization finds itself on the opposite side of that law, arguing that those protections should not apply to its former employee.

A lawyer representing the A.C.L.U., Ken Margolis, said during a legal proceeding last year that it was irrelevant whether Ms. Oh bore no racist ill will. All that mattered, he said, was that her Black colleagues were offended and injured.

“We’re not here to prove anything other than the impact of her actions was very real — that she caused harm,” Mr. Margolis said, according to a transcript of his remarks. “She caused serious harm to Black members of the A.C.L.U. community.”

Rick Bialczak, the lawyer who represents Ms. Oh through her union, responded sarcastically, saying he wanted to congratulate Mr. Margolis for making an exhaustive presentation of the A.C.L.U.'s evidence: three interactions Ms. Oh had with colleagues that were reported to human resources.

“I would note, and commend Ken, for spending 40 minutes explaining why three discreet comments over a multi-month period of time constitutes serious harm to the A.C.L.U. members, Black employees,” he said.

Yes, she had complained about Black supervisors, Mr. Bialczak acknowledged. But her direct boss and that boss’s boss were Black.

“Those were her supervisors,” he said. “If she has complaints about her supervision, who is she supposed to complain about?”

Ms. Oh declined to comment for this article, citing the ongoing case.

The A.C.L.U. has a history of representing groups that liberals revile. This week, it argued in the Supreme Court on behalf of the National Rifle Association in a First Amendment case.

But to critics of the A.C.L.U., Ms. Oh’s case is a sign of how far the group has strayed from its core mission — defending free speech — and has instead aligned itself with a progressive politics that is intensely focused on identity.

“Much of our work today,” as it explains on its website, “is focused on equality for people of color, women, gay and transgender people, prisoners, immigrants, and people with disabilities.”

And since the beginning of the Trump administration, the organization has taken up partisan causes it might have avoided in the past, like running an advertisement to support Stacey Abrams’s 2018 campaign for governor of Georgia.

“They radically expanded and raised so much more money — hundreds of millions of dollars — from leftist donors who were desperate to push back on the scary excesses of the Trump administration,” said Lara Bazelon, a law professor at the University of San Francisco who has been critical of the A.C.L.U. “And they hired people with a lot of extremely strong views about race and workplace rules. And in the process, they themselves veered into a place of excess.”

“I scour the record for any evidence that this Asian woman is a racist,” Ms. Bazelon added, “and I don’t find any.”

The beginning of the end for Ms. Oh, who worked in the A.C.L.U.’s political advocacy department, started in late February 2022, according to court papers and interviews with lawyers and others familiar with the case.

The A.C.L.U. was hosting a virtual organization-wide meeting under heavy circumstances. The national political director, who was Black, had suddenly departed following multiple complaints about his abrasive treatment of subordinates. Ms. Oh, who was one of the employees who had complained, spoke up during the meeting to declare herself skeptical that conditions would actually improve.

“Why shouldn’t we simply expect that ‘the beatings will continue until morale improves,’” she said in a Zoom group chat, invoking a well-known phrase that is printed and sold on T-shirts, usually accompanied by the skull and crossbones of a pirate flag. She explained that she was being “definitely metaphorical.”

Soon after, Ms. Oh heard from the A.C.L.U. manager overseeing its equity and inclusion efforts, Amber Hikes, who cautioned Ms. Oh about her language. Ms. Oh’s comment was “dangerous and damaging,” Ms. Hikes warned, because she seemed to suggest the former supervisor physically assaulted her.

“Please consider the very real impact of that kind of violent language in the workplace,” Ms. Hikes wrote in an email.

Ms. Oh acknowledged she had been wrong and apologized.

Over the next several weeks, senior managers documented other instances in which they said Ms. Oh mistreated Black employees.

In early March, Ben Needham, who had succeeded the recently departed national political director, reported that Ms. Oh called her direct supervisor, a Black woman, a liar. According to his account, he asked Ms. Oh why she hadn’t complained earlier.

She responded that she was “afraid” to talk to him.

“As a Black male, language like ‘afraid’ generally is code word for me,” Mr. Needham wrote in an email to other A.C.L.U. managers. “It is triggering for me.”

Mr. Needham, who is gay and grew up in the Deep South, said in an interview that as a child, “I was taught that I’m a danger.”

To hear someone say they’re afraid of him, he added, is like saying, “These are the people we should be scared of.”

Ms. Oh and her lawyers have cited her own past: As a survivor of domestic abuse, she was particularly sensitive to tense interactions with male colleagues. She said she was troubled by Mr. Needham’s once referring to his predecessor as a “friend,” since she was one of the employees who had criticized him.

Mr. Needham said he had been speaking only about their relationship in a professional context.

According to court records, the A.C.L.U. conducted an internal investigation into whether Ms. Oh had any reason to fear talking to Mr. Needham, and concluded there were “no persuasive grounds” for her concerns.

The following month, Ms. Hikes, the head of equity and inclusion, wrote to Ms. Oh, documenting a third incident — her own.

“Calling my check-in ‘chastising’ or ‘reprimanding’ feels like a willful mischaracterization in order to continue the stream of anti-Black rhetoric you’ve been using throughout the organization,” Ms. Hikes wrote in an email.

“I’m hopeful you’ll consider the lived experiences and feelings of those you work with,” she added. (Citing the ongoing case, the A.C.L.U. said Ms. Hikes was unable to comment for this article.)

The final straw leading to Ms. Oh’s termination, the organization said, came in late April, when she wrote on Twitter that she was “physically repulsed” having to work for “incompetent/abusive bosses.”

As caustic as her post was — likely grounds for dismissal in most circumstances — her speech may have been protected. The N.L.R.B.’s complaint rests on an argument that Ms. Oh, as an employee who had previously complained about workplace conditions with other colleagues, was engaging in what is known legally as “protected concerted activity.”

“The public nature of her speech doesn’t deprive it of N.L.R.A. protection,” said Charlotte Garden, a law professor at the University of Minnesota, referring to the National Labor Relations Act, which covers worker’s rights.

She added that the burden of proof rests with the N.L.R.B., which must convince the judge that Ms. Oh’s social media post, and her other comments, were part of a pattern of speaking out at work.

“You could say this is an outgrowth of that, and therefore is protected,” she said.

The A.C.L.U. has argued that it has a right to maintain a civil workplace, just as Ms. Oh has a right to speak out. And it has not retreated from its contention that her language was harmful to Black colleagues, even if her words were not explicitly racist.

Terence Dougherty, the general counsel, said in an interview that standards of workplace conduct in 2024 have shifted, likening the case to someone who used the wrong pronouns in addressing a transgender colleague.

“There’s nuance to the language,” Mr. Dougherty said, “that does really have an impact on feelings of belonging in the workplace.”

Jeremy W. Peters is a Times reporter who covers debates over free expression and how they impact higher education and other vital American institutions. More about Jeremy W. Peters

Advertisement

Adding health to the reparations conversation in Boston

- Martha Bebinger

It’s usually economists, historians, advocates or politicians who make the case for reparations to address centuries of harm for people of color that started with slavery. One form reparations can take is direct payments that could close the wealth gap between Black and White Americans. That gap, which includes income and assets like a home, is vast and growing .

But some health and public health experts are weighing in as well. They’re making the case for reparations as a tool to reduce deep disparities in health for people of color. Multiple studies have linked racism to poorer health and shorter life expectancy for Black Americans compared to whites. Yet, broader reparations efforts have struggled to find political support and funding.

Dr. Mary Bassett, director of the FXB Center for Health and Human Rights at Harvard, says that needs to change.

“Reparations can be seen as a health intervention, not only a moral repair, but a way of addressing these long-standing health inequities,” Bassett told an audience at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health last week. “Money has to be part of it, let me be clear about that.”

Bassett co-authored a study that suggested closing the wealth gap could narrow the difference in life expectancy between older Black and white adults.

But the cost of providing meaningful compensation to descendants for the harms due to slavery is sobering. A separate study estimated the national price tag for lost wages alone, plus interest, could top $14 trillion .

Critics — and even some supporters of reparations — call that figure unrealistic for any reparations program to pay out today. But the study's authors say it’s the minimum needed because $14 trillion only accounts for past harms. It doesn’t include the ongoing financial impact of discrimination in housing, employment, the legal system and on health.

There’s little research about whether direct payments to individuals would reduce high rates of infant mortality , heart disease and stroke suffered by Black Americans. That’s why some supporters of “health reparations” are calling for a definition that goes beyond cash payments.

Dr. Avik Chatterjee says it should include hospitals and health care professionals who have not offered Black patients the same care white patients receive. He says health systems can make amends and prevent further damage by ending racist practices, opening clinics in underserved areas or taking other steps guided by community input.

“Health reparations doesn’t necessarily mean cash to specific people,” said Chatterjee, an associate professor at Boston University School of Medicine. “It may mean changing the way we allow people to access health care. That will improve the health disparities we see now.”

Some prominent health institutions, including Mass General Brigham , Boston Medical Center and Cambridge Health Alliance , say they are already working to address systemic racism. The Massachusetts Department of Public Health launched a health equity office this year to address racism as a serious public health threat. A group of health care leaders of color is making the economic case for change using an estimate that shows health disparities cost Massachusetts nearly $6 billion a year .

Despite these efforts, many initiatives aimed at reducing health inequities are still struggling for funds. Boston City Councilor Julia Mejia told the audience at Harvard she has been advocating for a proposed Neighborhood Birth Center in Boston. Research shows similar birthing centers may help improve patient experiences and reduce the use of medical interventions during delivery. Mejia said she hopes the center can help improve maternal mortality rates. Black women are nearly twice as likely to die during or shortly after birth than white women in Massachusetts, according to state data.

Mejia helped launch a reparations task force in Boston that is expected to issue recommendations next year . A separate grassroots group in Boston is calling for $15 billion in reparations , but did not specify health care as an area of focus. Mejia argued health is fundamental to repairing the harm caused by centuries of discrimination.

“Health is wealth,” Mejia said. “People are not going to do well unless they are well.”

- Boston reparations task force will not complete work by end-of-year target

- Wu appoints task force to consider reparations in Boston

- Health leaders call for action to end disparities that cost Mass. an estimated $5.9 billion per year

- ESSAY: Boston hospitals can make miracles. Yet our Black maternal health crisis persists

Martha Bebinger Reporter Martha Bebinger covers health care and other general assignments for WBUR.

More from WBUR

Baltimore Mayor Taunts Right-Wing Trolls With Brutally Honest New ‘DEI’ Definition

Baltimore Mayor Brandon Scott provided a new meaning for the acronym “DEI” after conservative critics linked him to diversity, equity and inclusion efforts in response to the deadly Francis Scott Key Bridge collapse .

“I know, and we know, and you know very well, that Black men, and young Black men in particular, have been the bogeyman for those who are racist and think that only straight, wealthy white men should have a say in anything,” said Scott on Wednesday’s edition of MSNBC ’s “The ReidOut.”

He continued, “We’ve been the bogeyman for them since the first day they brought us to this country, and what they mean by ‘DEI,’ in my opinion, is duly elected incumbent.”

Scott weighed in on the attacks after an X account called him “ Baltimore’s DEI mayor ” in response to a clip of him asking people to pray for families of those impacted by the collapse. The post has gained 25 million views, 13,000 likes and 5,900 shares.

Host Joy Reid informed viewers that Scott was elected with “70% of the vote” back in 2020 by a city with a predominantly Black population.

“So by right-wing logic, a ‘diversity hire’ would have been a white man,” Reid said.

Scott later told Reid he knows what those critics “want to say.”

“But they don’t have the courage to say the N-word, and the fact that I don’t believe in their untruthful and wrong ideology, and I am very proud of my heritage and who I am and where I come from, scares them,” Scott said.

He continued, “Because me being at my position means that their way of thinking, their way of life of being comfortable while everyone else suffers, is going to be at risk, and they should be afraid because that’s my purpose in life.”

DEI has become a frequent target for right-wing attacks in recent years including in Florida, which has banned the use of state and federal funds for DEI programs at public colleges, and Texas .

Others such as Florida congressional candidate Anthony Sabatini declared “ DEI did this ” in response to the collapse while Utah Rep. Phil Lyman, a GOP gubernatorial candidate in the state, took aim at Maryland port commissioner Karenthia A. Barber, the first Black woman to hold the title.

“This is what happens when you have Governors who prioritize diversity over the wellbeing and security of citizens,” wrote Lyman, who later posted that “DEI=DIE.”

Lyman told The Salt Lake Tribune that the post was “not our best moment” and described it as a “knee-jerk reaction to some of the things others were putting out there,” adding that someone on his team made the comments without his approval.

Lyman’s posts are still online as of early Thursday morning.

Support HuffPost

Our 2024 coverage needs you, your loyalty means the world to us.

At HuffPost, we believe that everyone needs high-quality journalism, but we understand that not everyone can afford to pay for expensive news subscriptions. That is why we are committed to providing deeply reported, carefully fact-checked news that is freely accessible to everyone.

Whether you come to HuffPost for updates on the 2024 presidential race, hard-hitting investigations into critical issues facing our country today, or trending stories that make you laugh, we appreciate you. The truth is, news costs money to produce, and we are proud that we have never put our stories behind an expensive paywall.

Would you join us to help keep our stories free for all? Your contribution of as little as $2 will go a long way.

As Americans head to the polls in 2024, the very future of our country is at stake. At HuffPost, we believe that a free press is critical to creating well-informed voters. That's why our journalism is free for everyone, even though other newsrooms retreat behind expensive paywalls.

Our journalists will continue to cover the twists and turns during this historic presidential election. With your help, we'll bring you hard-hitting investigations, well-researched analysis and timely takes you can't find elsewhere. Reporting in this current political climate is a responsibility we do not take lightly, and we thank you for your support.

Contribute as little as $2 to keep our news free for all.

Dear HuffPost Reader

Thank you for your past contribution to HuffPost. We are sincerely grateful for readers like you who help us ensure that we can keep our journalism free for everyone.

The stakes are high this year, and our 2024 coverage could use continued support. Would you consider becoming a regular HuffPost contributor?

The stakes are high this year, and our 2024 coverage could use continued support. If circumstances have changed since you last contributed, we hope you’ll consider contributing to HuffPost once more.

Already contributed? Log in to hide these messages.

Popular in the Community

From our partner, more in politics.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

racism, the belief that humans may be divided into separate and exclusive biological entities called "races"; that there is a causal link between inherited physical traits and traits of personality, intellect, morality, and other cultural and behavioral features; and that some races are innately superior to others. The term is also applied to political, economic, or legal institutions and ...

Racism is discrimination and prejudice against people based on their race or ethnicity. Racism can be present in social actions, practices, or political systems (e.g. apartheid) that support the expression of prejudice or aversion in discriminatory practices. The ideology underlying racist practices often assumes that humans can be subdivided ...

Abstract. This article explores the meanings of racism in the sociology of race/ethnicity and provides a descriptive framework for comparing theories of racism. The authors argue that sociologists use racism to refer to four constructs: (1) individual attitudes, (2) cultural schema, and two constructs associated with structural racism: (3 ...

The sociological definition of racism is much more complex. In sociology, racism is defined as an ideology that prescribes statuses to racial groups based on perceived differences. Though races are not inherently unequal, racism forces this narrative. Genetics and biology do not support or even suggest racial inequality, contrary to what many ...

Racism, bias, and discrimination. Racism is a form of prejudice that generally includes negative emotional reactions to members of a group, acceptance of negative stereotypes, and racial discrimination against individuals; in some cases it can lead to violence. Discrimination refers to the differential treatment of different age, gender, racial ...

"Racism is a system of structuring opportunity and assigning value based on the social interpretation of how one looks, which is what we call race, that unfairly disadvantages some individuals and communities, unfairly advantages other individuals and communities and saps the strength of the whole society through the waste of human resources. ...

Abstract. The sociology of racism is the study of the relationship between racism, racial discrimination, and racial inequality. While past scholarship emphasized overtly racist attitudes and policies, contemporary sociology considers racism as individual- and group-level processes and structures that are implicated in the reproduction of ...

It is a crime to be racist to someone in the United Kingdom. According to UK law, a person is committing a 'hate crime' if they direct hostile behaviour at someone based on that person's race and ...

Racism is the process by which systems and policies, actions and attitudes create inequitable opportunities and outcomes for people based on race. Racism is more than just prejudice in thought or action. It occurs when this prejudice - whether individual or institutional - is accompanied by the power to discriminate against, oppress or limit the rights of others.

The public outpouring over racism that has been taking place in America since George Floyd's murder feels like a long-postponed renewal of the reckoning that shook the nation more than half a ...

Systemic and structural racism are forms of racism that are pervasively and deeply embedded in systems, laws, written or unwritten policies, and entrenched practices and beliefs that produce ...

Discrimination is the unfair or prejudicial treatment of people and groups based on characteristics such as race, gender, age, or sexual orientation. That's the simple answer. But explaining why it happens is more complicated. The human brain naturally puts things in categories to make sense of the world.

Open Document. Definition: Racism. Racism is the unequal treatment of the human beings on the basis of their skin color. Racism is believed to have existed as long as human beings have been in the world. It is usually associated with the skin color of a person, which makes one be distinguished from a certain race or community.

Introduction. Racism is when people are treated unfairly because of their skin color or background. It is a kind of discrimination, and it causes great harm to people. Racism takes many forms. It happens when people call other people names or attack them physically. For African Americans in particular it also exists in the way that systems of ...

Institutional racism is defined as: "processes, attitudes and behaviour(s) which amount to discrimination through unwitting prejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness and racist stereotyping which ...

Racism is discussed as a dehumanization related to the materiality of domination used by the world-system in the zone of non-being (violence and dispossession) as opposed to the materiality of ...

Racism cannot be defined without first defining race. Among social scientists, "race" is generally ... Indeed, historical variation in the definition and use of the term provides a case in point. The term race was first used to describe peoples and societies in the way we now understand ethnicity or national identity. Later, in the ...

What is racism? According to Encyclopedia Britannica, the definition of racism is any action, practice, or belief that reflects the racial worldview—the ideology that humans may be divided into separate and exclusive biological entities called "races"; that there is a causal link between inherited physical traits and traits of personality ...

Racism Essay: Racism can be defined as the belief that individual races of people have distinctive cultural features that are determined by the hereditary factors and hence make some races inherently superior to the others. The idea that one race has natural superiority than the others created abusive behaviour towards the members of other races. Racism, like discrimination towards women, is a ...

With the help of our dear friend Ms. "Merriam Webster," Michael Harriot breaks down the definition of racism and white supremacy. He gets to the bottom and delivers a message you won't hear ...

In his essay, Eco describes a number of characteristics of "Ur-Fascism — or Eternal Fascism". You are seeing a snapshot of an interactive graphic. This is most likely due to being offline or ...

Racism is one of the darkest, deepest and disgusting social issues of the world, existing throughout the history of mankind. It is a social construct created by humans to categorise the world. Racism is learned, we are not born with it. The most traditional form of this is discrimination based on one's skin colour.

racism. institutional racism, the perpetuation of discrimination on the basis of " race " by political, economic, or legal institutions and systems. According to critical race theory, an offshoot of the critical legal studies movement, institutional racism reinforces inequalities between groups—e.g., in wealth and income, education ...

The Definition of Racism. It covers both kinds, the old and the new. April 1, 2024 12:30 pm ET. Share. Resize. Photo: Getty Images.

The heart of the A.C.L.U.'s defense — arguing for an expansive definition of what constitutes racist or racially coded speech — has struck some labor and free-speech lawyers as peculiar ...

Multiple studies have linked racism to poorer health and shorter life expectancy for Black Americans compared to whites. Yet, broader reparations efforts have struggled to find political support ...

"I know, and we know, and you know very well, that Black men, and young Black men in particular, have been the bogeyman for those who are racist and think that only straight, wealthy white men should have a say in anything," said Scott on Wednesday's edition of MSNBC's "The ReidOut." He ...