Writing academically: Paragraph structure

- Academic style

- Personal pronouns

- Contractions

- Abbreviations

- Signposting

Paragraph structure

- Using sources in your writing

Jump to content on this page:

“An appropriate use of paragraphs is an essential part of writing coherent and well-structured essays.” Don Shiach, How to write essays

- A topic sentence – what is the overall point that the paragraph is making?

- Evidence that supports your point – this is usually your cited material.

- Explanation of why the point is important and how it helps with your overall argument.

- A link (if necessary) to the next paragraph (or to the previous one if coming at the beginning of the paragraph) or back to the essay question.

This is a good order to use when you are new to writing academic essays - but as you get more accomplished you can adapt it as necessary. The important thing is to make sure all of these elements are present within the paragraph.

The sections below explain more about each of these elements.

The topic sentence (Point)

This should appear early in the paragraph and is often, but not always, the first sentence. It should clearly state the main point that you are making in the paragraph. When you are planning essays, writing down a list of your topic sentences is an excellent way to check that your argument flows well from one point to the next.

This is the evidence that backs up your topic sentence. Why do you believe what you have written in your topic sentence? The evidence is usually paraphrased or quoted material from your reading . Depending on the nature of the assignment, it could also include:

- Your own data (in a research project for example).

- Personal experiences from practice (especially for Social Care, Health Sciences and Education).

- Personal experiences from learning (in a reflective essay for example).

Any evidence from external sources should, of course, be referenced.

Explanation (analysis)

This is the part of your paragraph where you explain to your reader why the evidence supports the point and why that point is relevant to your overall argument. It is where you answer the question 'So what?'. Tell the reader how the information in the paragraph helps you answer the question and how it leads to your conclusion. Your analysis should attempt to persuade the reader that your conclusion is the correct one.

These are the parts of your paragraphs that will get you the higher marks in any marking scheme.

Links are optional but it will help your argument flow if you include them. They are sentences that help the reader understand how the parts of your argument are connected . Most commonly they come at the end of the paragraph but they can be equally effective at the beginning of the next one. Sometimes a link is split between the end of one paragraph and the beginning of the next (see the example paragraph below).

Paragraph structure video

Length of a paragraph

Academic paragraphs are usually between 200 and 300 words long (they vary more than this but it is a useful guide). The important thing is that they should be long enough to contain all the above material. Only move onto a new paragraph if you are making a new point.

Many students make their paragraphs too short (because they are not including enough or any analysis) or too long (they are made up of several different points).

Example of an academic paragraph

Using storytelling in educational settings can enable educators to connect with their students because of inborn tendencies for humans to listen to stories. Written languages have only existed for between 6,000 and 7,000 years (Daniels & Bright, 1995) before then, and continually ever since in many cultures, important lessons for life were passed on using the oral tradition of storytelling. These varied from simple informative tales, to help us learn how to find food or avoid danger, to more magical and miraculous stories designed to help us see how we can resolve conflict and find our place in society (Zipes, 2012). Oral storytelling traditions are still fundamental to native American culture and Rebecca Bishop, a native American public relations officer (quoted in Sorensen, 2012) believes that the physical act of storytelling is a special thing; children will automatically stop what they are doing and listen when a story is told. Professional communicators report that this continues to adulthood (Simmons, 2006; Stevenson, 2008). This means that storytelling can be a powerful tool for connecting with students of all ages in a way that a list of bullet points in a PowerPoint presentation cannot. The emotional connection and innate, almost hardwired, need to listen when someone tells a story means that educators can teach memorable lessons in a uniquely engaging manner that is common to all cultures.

This cross-cultural element of storytelling can be seen when reading or listening to wisdom tales from around the world...

Key: Topic sentence Evidence (includes some analysis) Analysis Link (crosses into next paragraph)

- << Previous: Signposting

- Next: Using sources in your writing >>

- Last Updated: Nov 10, 2023 4:11 PM

- URL: https://libguides.hull.ac.uk/writing

- Login to LibApps

- Library websites Privacy Policy

- University of Hull privacy policy & cookies

- Website terms and conditions

- Accessibility

- Report a problem

- Current Students

- News & Press

- Exam Technique for In-Person Exams

- Revising for 24 Hour Take Home Exams

- Introduction to 24 Hour Take Home Exams

- Before the 24 Hour Take Home Exam

- Exam Technique for 24 Hour Take Home Exams

- Structuring a Literature Review

- Writing Coursework under Time Constraints

- Reflective Writing

- Writing a Synopsis

- Structuring a Science Report

- Presentations

- How the University works out your degree award

- Personal Extenuating Circumstances (PEC)

- Accessing your assignment feedback via Canvas

- Inspera Digital Exams

- Writing Introductions and Conclusions

Paragraphing

- Reporting Verbs

Signposting

- Proofreading

- Working with a Proofreader

- Writing Concisely

- The 1-Hour Writing Challenge

- Apostrophes

- Semi-colons

- Run-on sentences

- How to Improve your Grammar (native English)

- How to Improve your Grammar (non-native English)

- Independent Learning for Online Study

- Reflective Practice

- Academic Reading

- Strategic Reading Framework

- Note-taking Strategies

- Note-taking in Lectures

- Making Notes from Reading

- Using Evidence to Support your Argument

- Integrating Scholarship

- Managing Time and Motivation

- Dealing with Procrastination

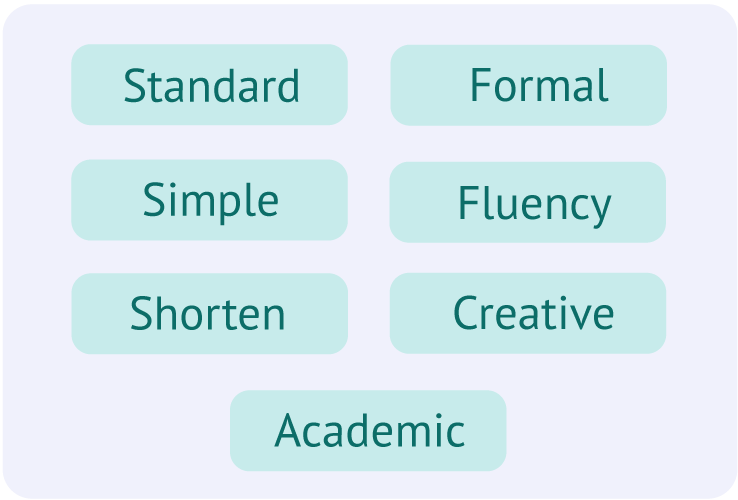

- How to Paraphrase

- Quote or Paraphrase?

- How to Quote

- Referencing

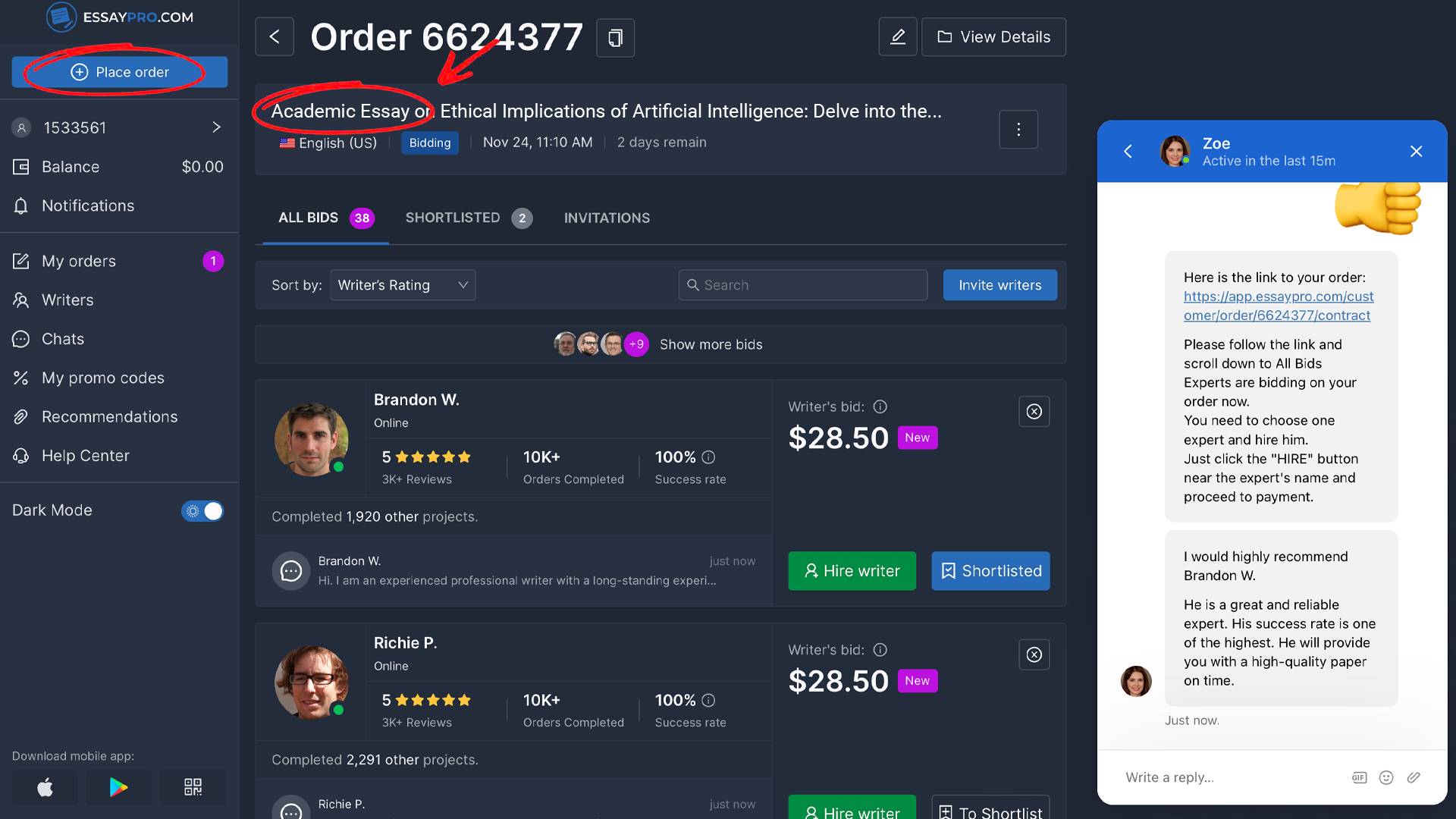

- Artificial Intelligence and Academic Integrity

- Use and limitations of generative AI

- Acknowledging use of AI

- Numeracy, Maths & Statistics

- Library Search

- Search Techniques

- Keeping up to date

- Evaluating Information

- Managing Information

- Thinking Critically about AI

- Using Information generated by AI

- Digital Capabilities

- SensusAccess

- Develop Your Digital Skills

- Digital Tools to Help You Study

Find out how to structure an academic paragraph.

- Newcastle University

- Academic Skills Kit

- Academic Writing

Academic Writing has its own conventions, not just in terms of style and language, but also structure, and the use of paragraphs is one of those conventions.Paragraphs don’t just make a text easier to read by breaking it up on the page. They are a key tool in creating and signposting structure in academic writing, as they are the building blocks of an argument, separating each point and showing how they link together to form the structure. They also have a characteristic structure of their own.

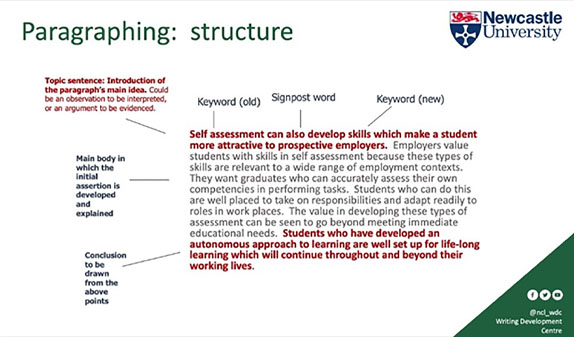

View enlarged image

Paragraphs and points

A common piece of advice is ‘one point per paragraph’. This can be a little hard to put into practice – what counts as ‘a point’? The whole assignment could be said to be making a point, and each sentence also makes a point. Another way to think of it is that a point in this sense is a statement of argument or observation that contributes a significant and essential step in your whole structure, without which your conclusion will be weakened. A point like this can’t stand on its own without being further unpacked with evidence, explanation, interpretation etc, which is the job of the rest of the paragraph. You should be able to get the overall gist and structure of an academic text by just reading the first line of each paragraph.

Topic sentences

This point is usually the first (in some cases the second) sentence of the paragraph, commonly known as the topic sentence. The point made is usually an argumentative statement which needs to be demonstrated or an observation which needs to be interpreted or explained (the former is more common in Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences; the latter is more common in the sciences, but they can be found in both). The topic sentence introduces the main idea of the paragraph, usually with a key word which echoes the signposting language from the introduction so the reader recognises it. It also moves from what we know (the old keyword) to the new information (the new keyword), showing how the paragraph builds on what has gone before. It also indicates how it connects to the previous paragraph with a signpost word. This linking should be as brief as possible, as the longer your reader has to wait or the more they have to search for the new idea, the more confused they are likely to become.

Paragraph structure

Academic paragraphs work like court reports rather than murder mysteries; start with the end result and then explain how you got there, rather than taking the reader on an exploration with the purpose only revealed at the end. One simple model for paragraph structure is PEEL: Point, Evidence, Evaluation, Link (to the assignment topic or next paragraph). This is a good starting point, but you may find it too rigid and restrictive for what you need to do, or too clumsy and repetitive in constantly linking back or forward. Look at some of the paragraphs in the academic books or articles you’re reading and see how they are structured and how often they fit this model, and how they vary. Average paragraph length varies depending on your subject - Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences tend to use longer paragraphs than in the sciences.

Sentence structure

In English, the reader prioritises the information which is at the start of the sentence (they are front-loaded). Sentence length varies according to personal taste and discipline convention, but overly long sentences can mean that later elements get overlooked or the sentence coherence breaks down. If your sentence contains several important elements, then it might be best to split into two or more sentences so that each one gets its own spotlight. You can use signposting words to make the connection between them clear. Compare these two versions. Which is better?

In English, sentences are ‘front-loaded’ so the most important information appears early on, and later information may be lost, meaning that writers might separate very long sentences and use signpost words to demonstrate the link.

In English, sentences are ‘front-loaded’ so the most important information appears early on. Later information may be lost as a result. Writers might therefore separate very long sentences and use signpost words to demonstrate the link.

Troubleshooting

- You’re not sure which is your topic sentence.

- Your reader gives you the feedback that your point isn’t clear (or that your writing is too descriptive).

Your main point is likely to be buried somewhere in your paragraph, or there isn’t a clear focus. This could be an issue with planning, or that you are still working your ideas out as you write. Ask yourself: if you could only keep one sentence from each paragraph, which one would it be? That is most likely an idea, argument or observation of your own rather than from your reading. This is likely to be your topic sentence, and should be placed at the start of your paragraph. Your reader should be able to follow your overall structure by reading the first line of each paragraph, to capture your points. If the first line of your paragraph is just a descriptive fact or quote from someone else, then they aren’t going to get a sense of your argument.

- Your paragraphs are very long.

- More than one of your sentences could be your topic sentence.

You may have some less relevant material which isn’t essential to making your point, or your paragraph may be making two related points rather than one. If you ask ‘if I could only keep one sentence from this paragraph, which would it be?’ and can’t decide between two sentences, then you may have two points which would be better developed separately in two paragraphs. You could also look at each sentence and decide if it’s necessary or just nice to have, and whether your overall point would be undermined if you removed it, or if it just adds interest but is not strictly essential.

- Your paragraphs are very short.

- Your feedback suggests that you need to ‘unpack’ or ‘expand’ your points.

You may have an isolated fragment which on your plan looked like it might be enough for a paragraph but didn’t work out being very much when you came to write it up. This would be better integrated into another paragraph if it fits, or cut if it doesn’t. You may instead have skipped some of your reasoning, not developing your point fully with all of the evidence and explanation needed, and instead assuming that your reader is following you. In this case, try analysing what you have written and after each sentence (or part of a sentence), identify what questions the reader might ask about that to be convinced of it, such as ‘what does that mean? How do you know? Why / how does that happen? What is the significance of that? How does that prove your point?’ If you haven’t answered any of the questions that occur to you, you may need to expand on that aspect more fully.

Download this guide as a PDF

Find out how to structure an academic paragraph. **PDF Download**

More in this section

Reporting verbs.

Explore different ways of referring to literature and foregrounding your voice.

Explore different ways of guiding the reader through your assignment.

Examples of paragraphs in academic writing

Each of the following paragraphs have notes that explain how they work and what you can learn from them. The examples are from published academic work from a wide variety of disciplines and you can read each item online using the reference provided.

Select a paragraph type to learn more.

Synthesising

Giving context or explanation, using sources as evidence, introductory paragraphs.

- Demonstrating your position

Concluding paragraphs

Discussing results, using a quotation to illustrate a point, paragraphs that link together, proposing a new idea or theory.

You can download all the information included within each section of this exercise by downloading the Microsoft Word document below.

Download paragraph examples (.docx)

Now that you have gone through all parts of the exercise, you can return to the main Library website by selecting the 'Back to Library' button below.

This section will provide an outline of the features of synthesising, that is, using multiple sources in broad agreement with one another .

The digital notebook below is currently blank. Select the 'Add text' button to begin building the digital notes and get an explanation of useful elements. You may need to scroll within the notebook to see everything.

As you are viewing this exercise on mobile, once you add notes, you will need to scroll down within the notebook to see the associated features.

Supporting your points with multiple sources which broadly agree with one another, can give extra credibility and strength to your writing.

The first sentence uses two sources to support the opening statement. Using more than one source is a good way to show that the point you are making may have a solid basis in research, therefore adding strength to your point.

This technique is also used later in the paragraph, grouping together two or more sources which are broadly in agreement with one another and backing up the points being made.

Even though early treatments for ADHD are efficacious, few children typically receive specialty mental health care ( Danielson et al., 2018 ; Hoza et al., 2006 ). In the 2016 National Survey of Children's Health, more than six million children and teens had been diagnosed with ADHD, and of these, 5.4 million had current ADHD. About 23% of children with current ADHD diagnoses had not received any treatment ( Danielson et al., 2018 ). Yet, there are often delays in identification which lead to high societal costs ( Biederman & Faraone, 2006 ; Mahone & Denckla, 2017 ). The reason for these high costs is that children and adolescents with ADHD are at high risk of other issues such as accidents, injuries, and substance abuse ( Hurtig et al., 2016 ; Leibson et al., 2001 ; Molina & Pelham, 2014 ). Moreover, it is difficult to ascertain the reasons why children diagnosed with behavioral issues are unable to access timely treatment.

This section will provide an outline of giving context or explanation.

Whilst good academic writing needs to show critical analysis, using a variety of sources and demonstrating clear arguments, it is also important to add context and explanations where necessary.

This paragraph outlines the topic, setting the scene for a more thorough and detailed examination in the rest of the chapter.

The writer gives the subject matter context by summarising the current situation.

References to the work of other authors are used to bring in real examples which also help to build a general picture of the area.

The mobile nature of digital games ensures that the lines between in-school and out-of-school gameplay is blurred. Thus, it is important to explore the possibilities of these games to create new spaces for learning and engaging with mathematics. From a social learning perspective, research has been concerned with the ways in which the games industry has been influencing ‘interactive’ learning via computers (Scanlon et al. 2005); creating spaces for students to create their own digital games in order to teach concepts to peers (Li 2010); or the ways in which the games are arranged to motivate learners to engage with the games (Habgood and Ainsworth 2011) and engage with higher-order problem solving abilities (Sun et al. 2011). These and many other studies seem to support the possibilities of digital games to promote learning.

This section will provide an outline of using sources as evidence.

Reading academic texts not only gives you a deeper understanding of your subject area, but also exposes you to different viewpoints and evidence. When you write at university, you use your reading to support the claims or arguments that you make in your work. You could also present sources giving counter arguments to demonstrate alternative perspectives

The frequent use of citations for other sources in this example, shows that there is evidence for all of the claims being made. This gives credibility to the writing.

Citations can be used in the middle or at the end of your sentences and in some science, engineering or medical subjects they may be used at the end of a paragraph, which is not always the case in Arts and Humanities academic writing. Check with your department if you are unsure what is expected.

The Australian Psychological Society (APS) reports that one in four Australians feel lonely and over half of the population feel that they lack valuable social connection 1 . Whether objective or perceived (i.e. loneliness), the consequences of prolonged social isolation are significant. Social isolation is linked to severe negative health implications including increased risk of heart disease 2 , cancer 3 and obesity 4 , culminating in reduced life expectancy 5,6 . Social isolation also comes with significant risk of mental health and neuropsychiatric disorders, including chronic anxiety and depression 7,8 . Alongside this complex aetiology, social isolation has been linked to the increased prevalence of substance use disorders across a range of drug types 7 , where social isolation both predicts drug abuse, and drug abuse occurs as a consequence of social isolation 9,10,11 . Unfortunately, when socially isolated individuals wish to moderate or quit drug-intake, quitting is more difficult and less successful 12,13 , limiting the likelihood of a long lasting recovery.

This section will provide an outline of introductory paragraphs.

Introductory paragraphs give the reader an understanding of what is coming up in the article.

This paragraph uses linguistic ‘signposts’ to help the reader to understand major developments in the history of Stonehenge.

The writer gives some background about Stonehenge and the way in which it changed and developed over time. If you knew nothing about the topic, this introduction gives key facts, information and context. If, however you are familiar with the subject, this paragraph is a neat overview, creating a gateway to the rest of the article.

The second paragraph begins with an introduction to the aims and objectives of the Stonehenge Riverside Project.

This provides useful signpost, in the last sentence, what is coming up next.

Stonehenge, a Late Neolithic–Early Bronze Age monument in Wiltshire, southern England, was constructed in five stages between around 3000 BC and 1500 BC (Darvill et al. 2012). The first stage consisted of a circular ditch enclosing pits thought to have held posts or standing stones, of which the best known are the 56 Aubrey Holes. These are now believed to have held a circle of small standing stones, specifically ‘bluestones’ from Wales (Parker Pearson et al. 2009: 31–33). In its second stage , Stonehenge took on the form in which it is recognisable today, with its ‘sarsen’ circle and horseshoe array of five sarsen ‘trilithons’ surrounding the rearranged bluestones.

Starting in 2003, the Stonehenge Riverside Project explored the theory that Stonehenge was built in stone for the ancestors, whereas timber circles and other wooden structures were made for the living (Parker Pearson & Ramilisonina 1998). Stonehenge has long been known to contain prehistoric burials (Hawley 1921). Most were undated, so a priority for the project was to establish whether, when and in what ways these dead were associated with the monument. Until excavation in 2008, most of the recovered human remains remained inaccessible for scientific research, having been reburied at Stonehenge in 1935 (Young 1935: 20–21).

Demonstrating your position (your voice)

This section will provide an outline of demonstrating your position, that's to say, your voice.

The way in which you express your thoughts in academic writing can vary depending on your subject area.

This writer makes statements that clearly demonstrate their opinion. They say for example that “Science fiction is a useful tool...”, “Gender, in turn, offers an interesting glimpse...”, “The process is a particularly rewarding version...”. The language chosen shows what the writer thinks about this topic.

In this second paragraph (from a different source) the writer makes clear their position about decreased nerve conduction velocity and why this matters: ‘appreciably decreased NCV can be an important indicator of nerve injury or disease’.

Science fiction is a useful tool for investigating habits of thought, including conceptions of gender. Gender, in turn, offers an interesting glimpse into some of the unacknowledged messages that permeate science fiction. Each reads the other in very interesting ways. Examining stories with a view to both their science-fictional qualities and their uses of gender generates new questions about both gender and genre. Then those questions can be addressed to those and other stories to yield further insights. The process is a particularly rewarding version of the hermeneutic circle-a decoding ring.

Impulses travel along nerves at a speed called the nerve conduction velocity (NCV). This velocity has been extensively measured in human peripheral nerves because of its utility in clinical medicine (Liveson & Ma, 1992; Oh, 1993). Appreciably decreased NCV can be an important indicator of nerve injury or disease (Liveson & Ma, 1992; Oh, 1993).

This section will provide an outline of concluding paragraphs.

Depending on the written work that you do, you may need one or several concluding paragraphs.

This is an example of a concise stand-alone conclusion paragraph.

This conclusion brings together the main arguments that were made in the main body of the work.

The final sentence is a recommendation for future action, which can be a good way to emphasise your viewpoint.

Given the fragile health systems in most sub-Saharan African countries, new and re-emerging disease outbreaks such as the current COVID-19 epidemic can potentially paralyse health systems at the expense of primary healthcare requirements. The impact of the Ebola epidemic on the economy and healthcare structures is still felt five years later in those countries which were affected. Effective outbreak responses and preparedness during emergencies of such magnitude are challenging across African and other lower-middle-income countries. Such situations can partly only be mitigated by supporting existing regional and sub-Saharan African health structures.

This section will provide an outline of discussing results.

This paragraph effectively discusses the results of a research project. Paragraphs like this one are very common in science, engineering or medical subjects.

The first sentence contains the major finding of the research, which is then explored in more detail.

In the second sentence, the writer clearly states the need for more research as a major factor in the results obtained.

These results further indicate that not only liquid-bearing clouds 16 but also clouds composed exclusively of ice significantly increase radiative fluxes into the surface and decrease GrIS SMB. This underscores the need for continued research into the factors that govern the formation and maintenance of these distinct cloud regimes, and their evolution in a future warmer and wetter Arctic 36 . Evidence of the large spread in cloud cover and liquid/ice partitioning over the GrIS in current state-of-the-art climate models, in combination with our limited understanding of the interaction between clouds, circulation and climate 37 , suggests that improved cloud representations in climate models could significantly increase the fidelity of future projections of GrIS SMB and subsequent global sea level rise.

This section will provide an outline of using a quotation to illustrate a point.

Quotations are particularly useful where the phrasing of the original author’s point enhances your argument in a way that your own words could not. However, in science, engineering or medicine disciplines, quotations are very rarely used.

This paragraph incorporates a quotation from a book to illustrate and strengthen the main point (set out in the first sentence).

The quotation is introduced mid-paragraph and deepens our understanding of the argument by giving us insights into the feelings of the characters.

Rowling creates this intense tension between Harry’s substitute maternal and paternal figures to highlight just how connected Mrs. Weasley is to Harry Potter, and to illustrate how Harry’s situation has changed dramatically, though his journey is not nearly over. Harry is now part of several families: Hogwarts, the Weasley’s and soon the Order of Phoenix. He is cared for in a way he has never experienced before now, as is evident by Mrs. Weasley’s maternal wrath: “‘He’s not your son,” said Sirius quietly. “He’s as good as!” said Mrs. Weasley fiercely” (Rowling, 2004, p. 90) . Mrs. Weasley continues to clash with Sirius throughout OotP, believing he makes poor choices and doesn’t recognize that Harry would risk his own life for him. She can accept the peril Harry faces from Lord Voldemort, but she cannot tolerate that Sirius might carelessly expose Harry to danger.

This section will provide an outline of paragraphs that link together.

Paragraphs often (but not always) link together thematically, which means that one may continue an idea or argument from a previous paragraph.

The first sentence of the first paragraph sets out the topic under examination.

The first paragraph goes on to explore the topic in more depth, giving relevant examples and evidence as part of the discussion.

The second paragraph is intrinsically linked to the first. It acts as an extension, allowing the author to develop the point further by bringing in a new aspect of communication and analysing this in detail.

The men and women who saw or met the royal family in the war regularly confronted a perceptual gap between their own close-up sighting of them and official projections. A private with the 1st Battalion of the Welsh Regiment on the Western Front, who saw George V coming down from the line in 1916, remembered how surprised he was to find that the king was just a ‘little fellah with a beard’ – an observation that registered the difference between seeing the king nearby and how he was imagined in his public and ceremonial roles. 18 The early twentieth century witnessed a significant shift towards the democratization of public reputations in Britain and across the Anglophone world, involving the partial displacement of older notions of charisma by more commodified public personalities driven by the media. Soldiers and nurses who encountered the king and his family frequently registered a tension between traditional, prestigious images of royalty and those that were redolent with what journalists now defined as ‘human interest’ and even entertainment. 19 The article argues that one consequence of the intimate exposure of royalty during the war was that some who saw or met the king and his family perceived them more horizontally and less vertically, in ways that paralleled other forms of popular modernism. Adrian Gregory and Paul Fussell have emphasized that the war was fundamental in breaking social and cultural hierarchies, creating the conditions in which modernism would flourish. 20 One long-term effect of the loosening of traditional authority in the minds of some observers involved a partial desacralization of sovereignty, whereby royalty was brought closer to the lives of ordinary people in ways that intersected with developments in the popular media.

Publicity was one significant factor shaping the views of men and women who encountered royalty; the practice of letter-writing and diary keeping was another. Letters and postcards sent by troops at the front to family and friends at home were forms of social and cultural communication shaped by the long history of epistolary writing and its specific uses as a resource in wartime. Wartime censorship, which was enforced by officers for British and dominion rank-and-file troops, influenced what could be written in letters about a sensitive issue like the monarchy, though standards of inspection were uneven and critical comments did get through. 21 Diaries and memoirs encouraged greater reflection, and this was where more expansive and often trenchant remarks about the royal family emerged. The oral histories drawn on here pivot between remembering early twentieth-century royalty through the prism of nostalgia, or remembering them as central figures in a hierarchical society where witnesses saw themselves as either resistant or subaltern subjects. These personal testimonies provide historians not simply with an archive of opinion about the monarchy, but with a window onto competing structures of belief and feeling, as they were shaped by what Penny Summerfield has called distinctive ‘conduits of expression’. 22 They constructed meanings about sovereignty, while simultaneously involving audiences in their own projections of selfhood, in the context of both the structures of their own lives and the impact of European warfare.

This section will provide an outline of proposing a new idea or theory.

Sometimes your writing will need to be persuasive, for example, when you propose a new idea, theory or way of looking at an issue, or you may be trying to show that another writer’s point or argument is strong or weak.

The opening sentence signals that three new strategies are going to be set out.

In the second sentence, the first of these strategies is introduced.

The final two sentences begin to unpack the first strategy. Further emphasis is given to persuade the reader by the tone and use of language such as “important”.

Three strategies for reinserting class into planning theory and practice can be proposed. The first strategy is the acknowledgement that capitalism is based on economic antagonisms. When identifying “needs” in planning theory or practice, it is important to ask, whose needs? In contrast to contemporary assumptions where “communities” are the subjects and where “consensus” is an ideal (as in the King’s Cross Development), we would argue that one should recognize and consider antagonisms like class.

Academic Essay: From Basics to Practical Tips

Has it ever occurred to you that over the span of a solitary academic term, a typical university student can produce sufficient words to compose an entire 500-page novel? To provide context, this equates to approximately 125,000 to 150,000 words, encompassing essays, research papers, and various written tasks. This content volume is truly remarkable, emphasizing the importance of honing the skill of crafting scholarly essays. Whether you're a seasoned academic or embarking on the initial stages of your educational expedition, grasping the nuances of constructing a meticulously organized and thoroughly researched essay is paramount.

Welcome to our guide on writing an academic essay! Whether you're a seasoned student or just starting your academic journey, the prospect of written homework can be exciting and overwhelming. In this guide, we'll break down the process step by step, offering tips, strategies, and examples to help you navigate the complexities of scholarly writing. By the end, you'll have the tools and confidence to tackle any essay assignment with ease. Let's dive in!

Types of Academic Writing

The process of writing an essay usually encompasses various types of papers, each serving distinct purposes and adhering to specific conventions. Here are some common types of academic writing:

.webp)

- Essays: Essays are versatile expressions of ideas. Descriptive essays vividly portray subjects, narratives share personal stories, expository essays convey information, and persuasive essays aim to influence opinions.

- Research Papers: Research papers are analytical powerhouses. Analytical papers dissect data or topics, while argumentative papers assert a stance backed by evidence and logical reasoning.

- Reports: Reports serve as narratives in specialized fields. Technical reports document scientific or technical research, while business reports distill complex information into actionable insights for organizational decision-making.

- Reviews: Literature reviews provide comprehensive summaries and evaluations of existing research, while critical analyses delve into the intricacies of books or movies, dissecting themes and artistic elements.

- Dissertations and Theses: Dissertations represent extensive research endeavors, often at the doctoral level, exploring profound subjects. Theses, common in master's programs, showcase mastery over specific topics within defined scopes.

- Summaries and Abstracts: Summaries and abstracts condense larger works. Abstracts provide concise overviews, offering glimpses into key points and findings.

- Case Studies: Case studies immerse readers in detailed analyses of specific instances, bridging theoretical concepts with practical applications in real-world scenarios.

- Reflective Journals: Reflective journals serve as personal platforms for articulating thoughts and insights based on one's academic journey, fostering self-expression and intellectual growth.

- Academic Articles: Scholarly articles, published in academic journals, constitute the backbone of disseminating original research, contributing to the collective knowledge within specific fields.

- Literary Analyses: Literary analyses unravel the complexities of written works, decoding themes, linguistic nuances, and artistic elements, fostering a deeper appreciation for literature.

Our essay writer service can cater to all types of academic writings that you might encounter on your educational path. Use it to gain the upper hand in school or college and save precious free time.

Essay Writing Process Explained

The process of how to write an academic essay involves a series of important steps. To start, you'll want to do some pre-writing, where you brainstorm essay topics , gather information, and get a good grasp of your topic. This lays the groundwork for your essay.

Once you have a clear understanding, it's time to draft your essay. Begin with an introduction that grabs the reader's attention, gives some context, and states your main argument or thesis. The body of your essay follows, where each paragraph focuses on a specific point supported by examples or evidence. Make sure your ideas flow smoothly from one paragraph to the next, creating a coherent and engaging narrative.

After the drafting phase, take time to revise and refine your essay. Check for clarity, coherence, and consistency. Ensure your ideas are well-organized and that your writing effectively communicates your message. Finally, wrap up your essay with a strong conclusion that summarizes your main points and leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

How to Prepare for Essay Writing

Before you start writing an academic essay, there are a few things to sort out. First, make sure you totally get what the assignment is asking for. Break down the instructions and note any specific rules from your teacher. This sets the groundwork.

Then, do some good research. Check out books, articles, or trustworthy websites to gather solid info about your topic. Knowing your stuff makes your essay way stronger. Take a bit of time to brainstorm ideas and sketch out an outline. It helps you organize your thoughts and plan how your essay will flow. Think about the main points you want to get across.

Lastly, be super clear about your main argument or thesis. This is like the main point of your essay, so make it strong. Considering who's going to read your essay is also smart. Use language and tone that suits your academic audience. By ticking off these steps, you'll be in great shape to tackle your essay with confidence.

Academic Essay Example

In academic essays, examples act like guiding stars, showing the way to excellence. Let's check out some good examples to help you on your journey to doing well in your studies.

Academic Essay Format

The academic essay format typically follows a structured approach to convey ideas and arguments effectively. Here's an academic essay format example with a breakdown of the key elements:

Introduction

- Hook: Begin with an attention-grabbing opening to engage the reader.

- Background/Context: Provide the necessary background information to set the stage.

- Thesis Statement: Clearly state the main argument or purpose of the essay.

Body Paragraphs

- Topic Sentence: Start each paragraph with a clear topic sentence that relates to the thesis.

- Supporting Evidence: Include evidence, examples, or data to back up your points.

- Analysis: Analyze and interpret the evidence, explaining its significance in relation to your argument.

- Transition Sentences: Use these to guide the reader smoothly from one point to the next.

Counterargument (if applicable)

- Address Counterpoints: Acknowledge opposing views or potential objections.

- Rebuttal: Refute counterarguments and reinforce your position.

Conclusion:

- Restate Thesis: Summarize the main argument without introducing new points.

- Summary of Key Points: Recap the main supporting points made in the body.

- Closing Statement: End with a strong concluding thought or call to action.

References/Bibliography

- Cite Sources: Include proper citations for all external information used in the essay.

- Follow Citation Style: Use the required citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.) specified by your instructor.

- Font and Size: Use a standard font (e.g., Times New Roman, Arial) and size (12-point).

- Margins and Spacing: Follow specified margin and spacing guidelines.

- Page Numbers: Include page numbers if required.

Adhering to this structure helps create a well-organized and coherent academic essay that effectively communicates your ideas and arguments.

Ready to Transform Essay Woes into Academic Triumphs?

Let us take you on an essay-writing adventure where brilliance knows no bounds!

How to Write an Academic Essay Step by Step

Start with an introduction.

The introduction of an essay serves as the reader's initial encounter with the topic, setting the tone for the entire piece. It aims to capture attention, generate interest, and establish a clear pathway for the reader to follow. A well-crafted introduction provides a brief overview of the subject matter, hinting at the forthcoming discussion, and compels the reader to delve further into the essay. Consult our detailed guide on how to write an essay introduction for extra details.

Captivate Your Reader

Engaging the reader within the introduction is crucial for sustaining interest throughout the essay. This involves incorporating an engaging hook, such as a thought-provoking question, a compelling anecdote, or a relevant quote. By presenting an intriguing opening, the writer can entice the reader to continue exploring the essay, fostering a sense of curiosity and investment in the upcoming content. To learn more about how to write a hook for an essay , please consult our guide,

Provide Context for a Chosen Topic

In essay writing, providing context for the chosen topic is essential to ensure that readers, regardless of their prior knowledge, can comprehend the subject matter. This involves offering background information, defining key terms, and establishing the broader context within which the essay unfolds. Contextualization sets the stage, enabling readers to grasp the significance of the topic and its relevance within a particular framework. If you buy a dissertation or essay, or any other type of academic writing, our writers will produce an introduction that follows all the mentioned quality criteria.

Make a Thesis Statement

The thesis statement is the central anchor of the essay, encapsulating its main argument or purpose. It typically appears towards the end of the introduction, providing a concise and clear declaration of the writer's stance on the chosen topic. A strong thesis guides the reader on what to expect, serving as a roadmap for the essay's subsequent development.

Outline the Structure of Your Essay

Clearly outlining the structure of the essay in the introduction provides readers with a roadmap for navigating the content. This involves briefly highlighting the main points or arguments that will be explored in the body paragraphs. By offering a structural overview, the writer enhances the essay's coherence, making it easier for the reader to follow the logical progression of ideas and supporting evidence throughout the text.

Continue with the Main Body

The main body is the most important aspect of how to write an academic essay where the in-depth exploration and development of the chosen topic occur. Each paragraph within this section should focus on a specific aspect of the argument or present supporting evidence. It is essential to maintain a logical flow between paragraphs, using clear transitions to guide the reader seamlessly from one point to the next. The main body is an opportunity to delve into the nuances of the topic, providing thorough analysis and interpretation to substantiate the thesis statement.

Choose the Right Length

Determining the appropriate length for an essay is a critical aspect of effective communication. The length should align with the depth and complexity of the chosen topic, ensuring that the essay adequately explores key points without unnecessary repetition or omission of essential information. Striking a balance is key – a well-developed essay neither overextends nor underrepresents the subject matter. Adhering to any specified word count or page limit set by the assignment guidelines is crucial to meet academic requirements while maintaining clarity and coherence.

Write Compelling Paragraphs

In academic essay writing, thought-provoking paragraphs form the backbone of the main body, each contributing to the overall argument or analysis. Each paragraph should begin with a clear topic sentence that encapsulates the main point, followed by supporting evidence or examples. Thoroughly analyzing the evidence and providing insightful commentary demonstrates the depth of understanding and contributes to the overall persuasiveness of the essay. Cohesion between paragraphs is crucial, achieved through effective transitions that ensure a smooth and logical progression of ideas, enhancing the overall readability and impact of the essay.

Finish by Writing a Conclusion

The conclusion serves as the essay's final impression, providing closure and reinforcing the key insights. It involves restating the thesis without introducing new information, summarizing the main points addressed in the body, and offering a compelling closing thought. The goal is to leave a lasting impact on the reader, emphasizing the significance of the discussed topic and the validity of the thesis statement. A well-crafted conclusion brings the essay full circle, leaving the reader with a sense of resolution and understanding. Have you already seen our collection of new persuasive essay topics ? If not, we suggest you do it right after finishing this article to boost your creativity!

Proofread and Edit the Document

After completing the essay, a critical step is meticulous proofreading and editing. This process involves reviewing the document for grammatical errors, spelling mistakes, and punctuation issues. Additionally, assess the overall coherence and flow of ideas, ensuring that each paragraph contributes effectively to the essay's purpose. Consider the clarity of expression, the appropriateness of language, and the overall organization of the content. Taking the time to proofread and edit enhances the overall quality of the essay, presenting a polished and professional piece of writing. It is advisable to seek feedback from peers or instructors to gain additional perspectives on the essay's strengths and areas for improvement. For more insightful tips, feel free to check out our guide on how to write a descriptive essay .

Alright, let's wrap it up. Knowing how to write academic essays is a big deal. It's not just about passing assignments – it's a skill that sets you up for effective communication and deep thinking. These essays teach us to explain our ideas clearly, build strong arguments, and be part of important conversations, both in school and out in the real world. Whether you're studying or working, being able to put your thoughts into words is super valuable. So, take the time to master this skill – it's a game-changer!

Ready to Turn Your Academic Aspirations into A+ Realities?

Our expert pens are poised, and your academic adventure awaits!

Related Articles

.webp)

How to Write an Academic Essay in 6 Simple Steps

#scribendiinc

Written by Scribendi

Are you wondering how to write an academic essay successfully? There are so many steps to writing an academic essay that it can be difficult to know where to start.

Here, we outline how to write an academic essay in 6 simple steps, from how to research for an academic essay to how to revise an essay and everything in between.

Our essay writing tips are designed to help you learn how to write an academic essay that is ready for publication (after academic editing and academic proofreading , of course!).

Your paper isn't complete until you've done all the needed proofreading. Make sure you leave time for it after the writing process!

Download Our Pocket Checklist for Academic Papers. Just input your email below!

Types of academic writing.

With academic essay writing, there are certain conventions that writers are expected to follow. As such, it's important to know the basics of academic writing before you begin writing your essay.

Read More: What Is Academic Writing?

Before you begin writing your essay, you need to know what type of essay you are writing. This will help you follow the correct structure, which will make academic paper editing a faster and simpler process.

Will you be writing a descriptive essay, an analytical essay, a persuasive essay, or a critical essay?

Read More: How to Master the 4 Types of Academic Writing

You can learn how to write academic essays by first mastering the four types of academic writing and then applying the correct rules to the appropriate type of essay writing.

Regardless of the type of essay you will be writing, all essays will include:

An introduction

At least three body paragraphs

A conclusion

A bibliography/reference list

To strengthen your essay writing skills, it can also help to learn how to research for an academic essay.

Step 1: Preparing to Write Your Essay

The essay writing process involves a few main stages:

Researching

As such, in learning how to write an academic essay, it is also important to learn how to research for an academic essay and how to revise an essay.

Read More: Online Research Tips for Students and Scholars

To beef up your research skills, remember these essay writing tips from the above article:

Learn how to identify reliable sources.

Understand the nuances of open access.

Discover free academic journals and research databases.

Manage your references.

Provide evidence for every claim so you can avoid plagiarism .

Read More: 17 Research Databases for Free Articles

You will want to do the research for your academic essay points, of course, but you will also want to research various journals for the publication of your paper.

Different journals have different guidelines and thus different requirements for writers. These can be related to style, formatting, and more.

Knowing these before you begin writing can save you a lot of time if you also want to learn how to revise an essay. If you ensure your paper meets the guidelines of the journal you want to publish in, you will not have to revise it again later for this purpose.

After the research stage, you can draft your thesis and introduction as well as outline the rest of your essay. This will put you in a good position to draft your body paragraphs and conclusion, craft your bibliography, and edit and proofread your paper.

Step 2: Writing the Essay Introduction and Thesis Statement

When learning how to write academic essays , learning how to write an introduction is key alongside learning how to research for an academic essay.

Your introduction should broadly introduce your topic. It will give an overview of your essay and the points that will be discussed. It is typically about 10% of the final word count of the text.

All introductions follow a general structure:

Topic statement

Thesis statement

Read More: How to Write an Introduction

Your topic statement should hook your reader, making them curious about your topic. They should want to learn more after reading this statement. To best hook your reader in academic essay writing, consider providing a fact, a bold statement, or an intriguing question.

The discussion about your topic in the middle of your introduction should include some background information about your topic in the academic sphere. Your scope should be limited enough that you can address the topic within the length of your paper but broad enough that the content is understood by the reader.

Your thesis statement should be incredibly specific and only one to two sentences long. Here is another essay writing tip: if you are able to locate an effective thesis early on, it will save you time during the academic editing process.

Read More: How to Write a Great Thesis Statement

Step 3: Writing the Essay Body

When learning how to write academic essays, you must learn how to write a good body paragraph. That's because your essay will be primarily made up of them!

The body paragraphs of your essay will develop the argument you outlined in your thesis. They will do this by providing your ideas on a topic backed up by evidence of specific points.

These paragraphs will typically take up about 80% of your essay. As a result, a good essay writing tip is to learn how to properly structure a paragraph.

Each paragraph consists of the following:

A topic sentence

Supporting sentences

A transition

Read More: How to Write a Paragraph

In learning how to revise an essay, you should keep in mind the organization of your paragraphs.

Your first paragraph should contain your strongest argument.

The secondary paragraphs should contain supporting arguments.

The last paragraph should contain your second-strongest argument.

Step 4: Writing the Essay Conclusion

Your essay conclusion is the final paragraph of your essay and primarily reminds your reader of your thesis. It also wraps up your essay and discusses your findings more generally.

The conclusion typically makes up about 10% of the text, like the introduction. It shows the reader that you have accomplished what you intended to at the outset of your essay.

Here are a couple more good essay writing tips for your conclusion:

Don't introduce any new ideas into your conclusion.

Don't undermine your argument with opposing ideas.

Read More: How to Write a Conclusion Paragraph in 3 Easy Steps

Now that you know how to write an academic essay, it's time to learn how to write a bibliography along with some academic editing and proofreading advice.

Step 5: Writing the Bibliography or Works Cited

The bibliography of your paper lists all the references you cited. It is typically alphabetized or numbered (depending on the style guide).

Read More: How to Write an Academic Essay with References

When learning how to write academic essays, you may notice that there are various style guides you may be required to use by a professor or journal, including unique or custom styles.

Some of the most common style guides include:

Chicago style

For help organizing your references for academic essay writing, consider a software manager. They can help you collect and format your references correctly and consistently, both quickly and with minimal effort.

Read More: 6 Reference Manager Software Solutions for Your Research

As you learn how to research for an academic essay most effectively, you may notice that a reference manager can also help make academic paper editing easier.

Step 6: Revising Your Essay

Once you've finally drafted your entire essay . . . you're still not done!

That's because editing and proofreading are the essential final steps of any writing process .

An academic editor can help you identify core issues with your writing , including its structure, its flow, its clarity, and its overall readability. They can give you substantive feedback and essay writing tips to improve your document. Therefore, it's a good idea to have an editor review your first draft so you can improve it prior to proofreading.

A specialized academic editor can assess the content of your writing. As a subject-matter expert in your subject, they can offer field-specific insight and critical commentary. Specialized academic editors can also provide services that others may not, including:

Academic document formatting

Academic figure formatting

Academic reference formatting

An academic proofreader can help you perfect the final draft of your paper to ensure it is completely error free in terms of spelling and grammar. They can also identify any inconsistencies in your work but will not look for any issues in the content of your writing, only its mechanics. This is why you should have a proofreader revise your final draft so that it is ready to be seen by an audience.

Read More: How to Find the Right Academic Paper Editor or Proofreader

When learning how to research and write an academic essay, it is important to remember that editing is a required step. Don ' t forget to allot time for editing after you ' ve written your paper.

Set yourself up for success with this guide on how to write an academic essay. With a solid draft, you'll have better chances of getting published and read in any journal of your choosing.

Our academic essay writing tips are sure to help you learn how to research an academic essay, how to write an academic essay, and how to revise an academic essay.

If your academic paper looks sloppy, your readers may assume your research is sloppy. Download our Pocket Proofreading Checklist for Academic Papers before you take that one last crucial look at your paper.

About the Author

Scribendi's in-house editors work with writers from all over the globe to perfect their writing. They know that no piece of writing is complete without a professional edit, and they love to see a good piece of writing transformed into a great one. Scribendi's in-house editors are unrivaled in both experience and education, having collectively edited millions of words and obtained numerous degrees. They love consuming caffeinated beverages, reading books of various genres, and relaxing in quiet, dimly lit spaces.

Have You Read?

"The Complete Beginner's Guide to Academic Writing"

Related Posts

21 Legit Research Databases for Free Journal Articles in 2022

How to Find the Right Academic Paper Editor or Proofreader

How to Master the 4 Types of Academic Writing

Upload your file(s) so we can calculate your word count, or enter your word count manually.

We will also recommend a service based on the file(s) you upload.

English is not my first language. I need English editing and proofreading so that I sound like a native speaker.

I need to have my journal article, dissertation, or term paper edited and proofread, or I need help with an admissions essay or proposal.

I have a novel, manuscript, play, or ebook. I need editing, copy editing, proofreading, a critique of my work, or a query package.

I need editing and proofreading for my white papers, reports, manuals, press releases, marketing materials, and other business documents.

I need to have my essay, project, assignment, or term paper edited and proofread.

I want to sound professional and to get hired. I have a resume, letter, email, or personal document that I need to have edited and proofread.

Prices include your personal % discount.

Prices include % sales tax ( ).

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Academic writing : from paragraph to essay

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

obscured text back cover

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

522 Previews

17 Favorites

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station12.cebu on July 1, 2022

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

- November 30, 2022

- Academic Advice

How To Write an Academic Essay: A Beginner’s Guide

UOTP Marketing

During college, you must participate in many writing assessments, one of the most important being academic essays. Unfortunately, only a few are well-informed about the process of academic writing.

If you’re reading this, you probably want to learn how to write an academic essay. Follow our guide! Here we’ll introduce the concept of the academic essay, the five components of an academic essay, the format of an academic essay, and more.

Ready to master your academic essay writing? Let’s go!

What Is an Academic Essay?

An academic essay is writing created to initiate debate, defend an idea, or present a new point of view by supporting it with evidence.

One of the most important components that differentiate it from typical essays you have written in high school is supporting ideas with evidence. If you claim that, for example, “divorces have a negative impact on young children,” you need to find sources that support your argument to make it more convincing.

Interpreting facts is another essential element of a successful academic piece of writing. Academic essays should be written in a formal tone, with a set structure, and have a critical, based, and objective viewpoint. You should be able to understand and transmit different points of view to your readers in a simple but formal manner.

Are you still trying to figure out what steps you should take to start writing? Keep scrolling!

How To Write an Academic Essay

Writing an academic essay can initially seem intimidating, especially if you are unfamiliar with the rules and requirements.

The time and effort spent on the writing task might differ depending on the topic, word limit, deadline, and other factors. However, the key steps, including preparing for the writing, creating a thesis statement, introduction, conclusion, and editing process, must be included in every academic writing style.

By following the detailed list of actions below, you can start and finish your essay in no time.

Prepare to write your essay

Before going into the technical part of the writing process, one piece of advice you should keep in mind is planning. Planning is as important as the writing process. If you plan correctly, you will have sufficient time to perform every step successfully. Failure to plan will lead to a messy essay and, worst-case scenario, an unfinished writing piece.

Understand your assignment

First and foremost, before you take any action regarding writing your essay, you must ensure you have clearly understood every tiny detail that your instructor has provided you—this step will determine your academic essay’s effectiveness. But why is that? Understanding the assignment in detail will leave no space for any irrelevant information that would lead to wasted time and, ultimately, a lower grade.

Develop your essay topic

If your instructor doesn’t give you a specific topic, you should spend some time finding a topic that fits the requirements. Finding a topic sounds easy, but finding the right one requires more than just a simple google search.

So, ensure you develop an original topic, as it adds more value to your academic writing. However, ensure that there is enough evidence from other sources to help you back up your arguments. You can do this by researching similar topics from trusted sources.

Do your research and take notes

Once you determine the topic, go on and do some research. This part takes a lot of effort since there are countless sources online, and obviously, you have to choose some of the best.

Depending on your topic, there might be cases where online sources are not available, and you’ll also have to visit local libraries. Whatever the case, you need to take notes and highlight the components you want to include in your essay.

A quick tip: Go back to your topic often to avoid getting swayed or influenced by other less relevant ideas.

Come up with a clear thesis statement

An excellent academic essay contains a strong thesis statement. A strong thesis statement successfully narrows your topic into a specific area of investigation. It should also intrigue your readers and initiate debate.

A good thesis statement is:

- NOT a question

- NOT a personal opinion

Create a structure

After gathering all the necessary information, you can begin outlining your main ideas. The primary academic essay structure is classified into the following

- Introduction

Failure to maintain these three components in your academic essay will result in a poorly written assignment. Luckily, you can easily avoid that by following our guide.

Writing the introduction

Your essay will be divided into paragraphs of equal importance, but the introductory part should always stand out. You must make your introduction as presentable as possible and get the reader’s attention. Work on it as if you were to get graded only by the evaluation of that first paragraph.

The purpose of the introduction is to demonstrate that your thoughts and ideas are logical and coherent. Also, depending on the word limit, you can use more than one paragraph.

Hook the reader

All forms of writing benefit from an attractive hook. If you have no idea of how to hook the reader, you can go the safe way and choose a recent fact or statistic. Statistics will give your essay credibility, surprise the readers, and make them want to keep reading.

Give background on the topic

Now that you have the reader’s attention, you should strive to expand the essay’s key points but to a limit since the introduction is only one part of the whole essay. You should generally explain what gaps from previous sources you will cover and what others have covered so far.

Interested in pursuing a degree?

Fill out the form and get all admission information you need regarding your chosen program.

This will only take a moment.

Message Received!

Thank you for reaching out to us. we will review your message and get right back to you within 24 hours. if there is an urgent matter and you need to speak to someone immediately you can call at the following phone number:.

By clicking the Send me more information button above, I represent that I am 18+ years of age, that I have read and agreed to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy , and agree to receive email marketing and phone calls from UOTP. I understand that my consent is not required to apply for online degree enrollment. To speak with a representative without providing consent, please call +1 (202) 274-2300

- We value your privacy.

Present your thesis statement

When introducing your thesis statement, you can present it as a statement of fact or controversial. If you decide to give a statement fact, it will be challenging to keep your audience engaged since facts can be easily proven. But presenting it more controversially will keep your audience awake and can even result in a better grade overall.

Writing the body of your essay

The body part of your essay is where you’ll expand all of your ideas presented in the introduction. It’s essential to stay consistent and not include irrelevant information. Since it is the longest part of your essay, you can easily get lost, and to prevent that, it would be best to map an internal outline specific to each paragraph. This way, you know what to include and where.

Paragraph structure

Each paragraph should follow a specific structure. It should begin with an introductory sentence that tells the reader the main ideas you will discuss in the paragraph. It’s advisable to point back to your thesis statement to identify the relationship between it and the existing idea. Also, ensure that each paragraph demonstrates new ideas.

Length of the body paragraphs

Depending on the topic and the arguments you’ve gathered, it’s advisable not to exceed 200 words per paragraph in academic writing. If your paragraphs are too long and contain unnecessary wording, it will become difficult for the reader to follow your point. So keep them clear and concise.

Writing the conclusion

Congratulation, now you’ve made it to the last paragraph of your essay. The conclusion’s primary purpose is to summarize the ideas presented throughout your essay. Writing a good conclusion should take little time since you know what the essay contains. However, be aware of what points you should or shouldn’t include.

What to include in your conclusion

A strong conclusion needs to have an introductory sentence. In some cases, if your instructor approves, it can include other areas that need to be investigated in the future. But at its core, it should only remind the reader about the main arguments discussed.

What not to include in your conclusion

You should at all times refrain from including new ideas. Since the essay ends with the conclusion, don’t go into details or support new points. Doing that will confuse the reader and result in a poor grade.

Editing your essay

Without a doubt, editing is just as important as writing. No matter how careful you are during writing, there’s a high possibility that there will be some slip-ups. These can range from spelling mistakes to grammar, punctuation, and so on. We suggest you spend time doing other things and return to the essay again. This will help you notice errors that you otherwise wouldn’t.

Tips for Writing a Great College Essay

Now that you have a clear idea of the process of writing an academic essay, we have a few more tips:

- Always cite your sources

- Gather enough sources to support your thesis statement

- Keep your sentences short and comprehensive

- Start the research as early as possible

- Do not skip revising

The Bottom Line

Writing an academic essay is a complex task. But with the right tools, guidance, and willingness to learn from your mistakes, you will master academic writing in no time. Make sure to follow each of the abovementioned steps and practice as much as possible. And don’t forget to edit!

Share it with your friends!

Explore more.

Accounting vs. Finance Degree: Which Major to Choose?

12 Important Bookkeeping Skills You Need for a Successful Career

Recent resources.

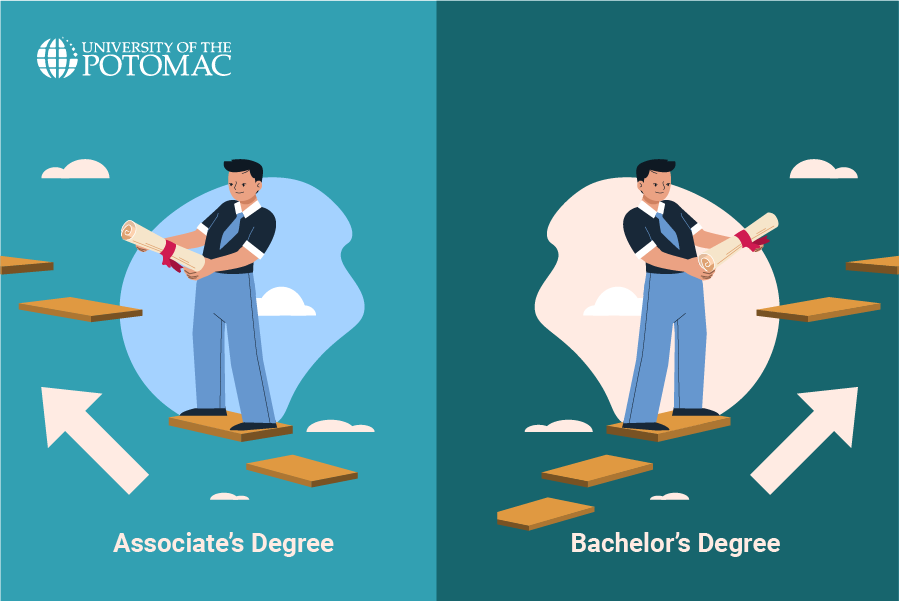

Associate’s vs. Bachelor’s: Which One To Choose?

Web Designer vs. Web Developer: What’s the Difference?

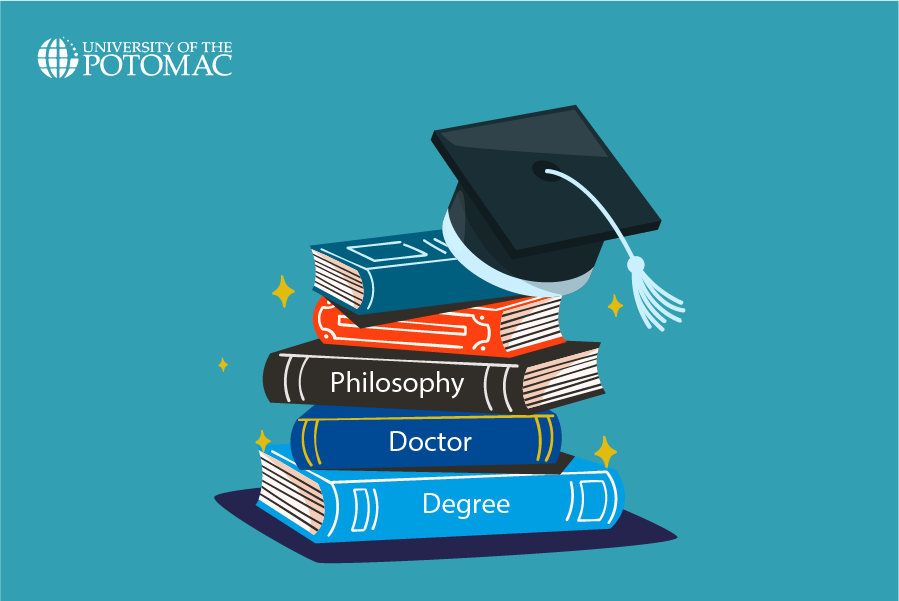

What Does Ph.D. Stand For?

What Is Scope In Project Management?

INTERESTED IN LEARNING MORE?

Chat with an Admissions Officer Now!

- Associates Degree

- Bachelors Degrees

- Masters Degrees

- Doctoral Degrees

- Faculty & Staff

- Accreditation

- Student Experience

QUICK LINKS

- Admission Requirements

- Military Students

- Financial Aid

Request More Information

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

On Paragraphs

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The purpose of this handout is to give some basic instruction and advice regarding the creation of understandable and coherent paragraphs.

What is a paragraph?

A paragraph is a collection of related sentences dealing with a single topic. Learning to write good paragraphs will help you as a writer stay on track during your drafting and revision stages. Good paragraphing also greatly assists your readers in following a piece of writing. You can have fantastic ideas, but if those ideas aren't presented in an organized fashion, you will lose your readers (and fail to achieve your goals in writing).

The Basic Rule: Keep one idea to one paragraph

The basic rule of thumb with paragraphing is to keep one idea to one paragraph. If you begin to transition into a new idea, it belongs in a new paragraph. There are some simple ways to tell if you are on the same topic or a new one. You can have one idea and several bits of supporting evidence within a single paragraph. You can also have several points in a single paragraph as long as they relate to the overall topic of the paragraph. If the single points start to get long, then perhaps elaborating on each of them and placing them in their own paragraphs is the route to go.

Elements of a paragraph

To be as effective as possible, a paragraph should contain each of the following: Unity, Coherence, A Topic Sentence, and Adequate Development. As you will see, all of these traits overlap. Using and adapting them to your individual purposes will help you construct effective paragraphs.

The entire paragraph should concern itself with a single focus. If it begins with one focus or major point of discussion, it should not end with another or wander within different ideas.

Coherence is the trait that makes the paragraph easily understandable to a reader. You can help create coherence in your paragraphs by creating logical bridges and verbal bridges.

Logical bridges

- The same idea of a topic is carried over from sentence to sentence

- Successive sentences can be constructed in parallel form

Verbal bridges

- Key words can be repeated in several sentences

- Synonymous words can be repeated in several sentences

- Pronouns can refer to nouns in previous sentences

- Transition words can be used to link ideas from different sentences

A topic sentence

A topic sentence is a sentence that indicates in a general way what idea or thesis the paragraph is going to deal with. Although not all paragraphs have clear-cut topic sentences, and despite the fact that topic sentences can occur anywhere in the paragraph (as the first sentence, the last sentence, or somewhere in the middle), an easy way to make sure your reader understands the topic of the paragraph is to put your topic sentence near the beginning of the paragraph. (This is a good general rule for less experienced writers, although it is not the only way to do it). Regardless of whether you include an explicit topic sentence or not, you should be able to easily summarize what the paragraph is about.

Adequate development

The topic (which is introduced by the topic sentence) should be discussed fully and adequately. Again, this varies from paragraph to paragraph, depending on the author's purpose, but writers should be wary of paragraphs that only have two or three sentences. It's a pretty good bet that the paragraph is not fully developed if it is that short.

Some methods to make sure your paragraph is well-developed:

- Use examples and illustrations

- Cite data (facts, statistics, evidence, details, and others)

- Examine testimony (what other people say such as quotes and paraphrases)

- Use an anecdote or story

- Define terms in the paragraph

- Compare and contrast

- Evaluate causes and reasons

- Examine effects and consequences

- Analyze the topic

- Describe the topic