Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write an argumentative essay | Examples & tips

How to Write an Argumentative Essay | Examples & Tips

Published on July 24, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

An argumentative essay expresses an extended argument for a particular thesis statement . The author takes a clearly defined stance on their subject and builds up an evidence-based case for it.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

When do you write an argumentative essay, approaches to argumentative essays, introducing your argument, the body: developing your argument, concluding your argument, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about argumentative essays.

You might be assigned an argumentative essay as a writing exercise in high school or in a composition class. The prompt will often ask you to argue for one of two positions, and may include terms like “argue” or “argument.” It will frequently take the form of a question.

The prompt may also be more open-ended in terms of the possible arguments you could make.

Argumentative writing at college level

At university, the vast majority of essays or papers you write will involve some form of argumentation. For example, both rhetorical analysis and literary analysis essays involve making arguments about texts.

In this context, you won’t necessarily be told to write an argumentative essay—but making an evidence-based argument is an essential goal of most academic writing, and this should be your default approach unless you’re told otherwise.

Examples of argumentative essay prompts

At a university level, all the prompts below imply an argumentative essay as the appropriate response.

Your research should lead you to develop a specific position on the topic. The essay then argues for that position and aims to convince the reader by presenting your evidence, evaluation and analysis.

- Don’t just list all the effects you can think of.

- Do develop a focused argument about the overall effect and why it matters, backed up by evidence from sources.

- Don’t just provide a selection of data on the measures’ effectiveness.

- Do build up your own argument about which kinds of measures have been most or least effective, and why.

- Don’t just analyze a random selection of doppelgänger characters.

- Do form an argument about specific texts, comparing and contrasting how they express their thematic concerns through doppelgänger characters.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

An argumentative essay should be objective in its approach; your arguments should rely on logic and evidence, not on exaggeration or appeals to emotion.

There are many possible approaches to argumentative essays, but there are two common models that can help you start outlining your arguments: The Toulmin model and the Rogerian model.

Toulmin arguments

The Toulmin model consists of four steps, which may be repeated as many times as necessary for the argument:

- Make a claim

- Provide the grounds (evidence) for the claim

- Explain the warrant (how the grounds support the claim)

- Discuss possible rebuttals to the claim, identifying the limits of the argument and showing that you have considered alternative perspectives

The Toulmin model is a common approach in academic essays. You don’t have to use these specific terms (grounds, warrants, rebuttals), but establishing a clear connection between your claims and the evidence supporting them is crucial in an argumentative essay.

Say you’re making an argument about the effectiveness of workplace anti-discrimination measures. You might:

- Claim that unconscious bias training does not have the desired results, and resources would be better spent on other approaches

- Cite data to support your claim

- Explain how the data indicates that the method is ineffective

- Anticipate objections to your claim based on other data, indicating whether these objections are valid, and if not, why not.

Rogerian arguments

The Rogerian model also consists of four steps you might repeat throughout your essay:

- Discuss what the opposing position gets right and why people might hold this position

- Highlight the problems with this position

- Present your own position , showing how it addresses these problems

- Suggest a possible compromise —what elements of your position would proponents of the opposing position benefit from adopting?

This model builds up a clear picture of both sides of an argument and seeks a compromise. It is particularly useful when people tend to disagree strongly on the issue discussed, allowing you to approach opposing arguments in good faith.

Say you want to argue that the internet has had a positive impact on education. You might:

- Acknowledge that students rely too much on websites like Wikipedia

- Argue that teachers view Wikipedia as more unreliable than it really is

- Suggest that Wikipedia’s system of citations can actually teach students about referencing

- Suggest critical engagement with Wikipedia as a possible assignment for teachers who are skeptical of its usefulness.

You don’t necessarily have to pick one of these models—you may even use elements of both in different parts of your essay—but it’s worth considering them if you struggle to structure your arguments.

Regardless of which approach you take, your essay should always be structured using an introduction , a body , and a conclusion .

Like other academic essays, an argumentative essay begins with an introduction . The introduction serves to capture the reader’s interest, provide background information, present your thesis statement , and (in longer essays) to summarize the structure of the body.

Hover over different parts of the example below to see how a typical introduction works.

The spread of the internet has had a world-changing effect, not least on the world of education. The use of the internet in academic contexts is on the rise, and its role in learning is hotly debated. For many teachers who did not grow up with this technology, its effects seem alarming and potentially harmful. This concern, while understandable, is misguided. The negatives of internet use are outweighed by its critical benefits for students and educators—as a uniquely comprehensive and accessible information source; a means of exposure to and engagement with different perspectives; and a highly flexible learning environment.

The body of an argumentative essay is where you develop your arguments in detail. Here you’ll present evidence, analysis, and reasoning to convince the reader that your thesis statement is true.

In the standard five-paragraph format for short essays, the body takes up three of your five paragraphs. In longer essays, it will be more paragraphs, and might be divided into sections with headings.

Each paragraph covers its own topic, introduced with a topic sentence . Each of these topics must contribute to your overall argument; don’t include irrelevant information.

This example paragraph takes a Rogerian approach: It first acknowledges the merits of the opposing position and then highlights problems with that position.

Hover over different parts of the example to see how a body paragraph is constructed.

A common frustration for teachers is students’ use of Wikipedia as a source in their writing. Its prevalence among students is not exaggerated; a survey found that the vast majority of the students surveyed used Wikipedia (Head & Eisenberg, 2010). An article in The Guardian stresses a common objection to its use: “a reliance on Wikipedia can discourage students from engaging with genuine academic writing” (Coomer, 2013). Teachers are clearly not mistaken in viewing Wikipedia usage as ubiquitous among their students; but the claim that it discourages engagement with academic sources requires further investigation. This point is treated as self-evident by many teachers, but Wikipedia itself explicitly encourages students to look into other sources. Its articles often provide references to academic publications and include warning notes where citations are missing; the site’s own guidelines for research make clear that it should be used as a starting point, emphasizing that users should always “read the references and check whether they really do support what the article says” (“Wikipedia:Researching with Wikipedia,” 2020). Indeed, for many students, Wikipedia is their first encounter with the concepts of citation and referencing. The use of Wikipedia therefore has a positive side that merits deeper consideration than it often receives.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

An argumentative essay ends with a conclusion that summarizes and reflects on the arguments made in the body.

No new arguments or evidence appear here, but in longer essays you may discuss the strengths and weaknesses of your argument and suggest topics for future research. In all conclusions, you should stress the relevance and importance of your argument.

Hover over the following example to see the typical elements of a conclusion.

The internet has had a major positive impact on the world of education; occasional pitfalls aside, its value is evident in numerous applications. The future of teaching lies in the possibilities the internet opens up for communication, research, and interactivity. As the popularity of distance learning shows, students value the flexibility and accessibility offered by digital education, and educators should fully embrace these advantages. The internet’s dangers, real and imaginary, have been documented exhaustively by skeptics, but the internet is here to stay; it is time to focus seriously on its potential for good.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

An argumentative essay tends to be a longer essay involving independent research, and aims to make an original argument about a topic. Its thesis statement makes a contentious claim that must be supported in an objective, evidence-based way.

An expository essay also aims to be objective, but it doesn’t have to make an original argument. Rather, it aims to explain something (e.g., a process or idea) in a clear, concise way. Expository essays are often shorter assignments and rely less on research.

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

The majority of the essays written at university are some sort of argumentative essay . Unless otherwise specified, you can assume that the goal of any essay you’re asked to write is argumentative: To convince the reader of your position using evidence and reasoning.

In composition classes you might be given assignments that specifically test your ability to write an argumentative essay. Look out for prompts including instructions like “argue,” “assess,” or “discuss” to see if this is the goal.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write an Argumentative Essay | Examples & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/argumentative-essay/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to write a thesis statement | 4 steps & examples, how to write topic sentences | 4 steps, examples & purpose, how to write an expository essay, what is your plagiarism score.

Jump to navigation

- Inside Writing

- Teacher's Guides

- Student Models

- Writing Topics

- Minilessons

- Shopping Cart

- Inside Grammar

- Grammar Adventures

- CCSS Correlations

- Infographics

Get a free Grammar Adventure! Choose a single Adventure and add coupon code ADVENTURE during checkout. (All-Adventure licenses aren’t included.)

Sign up or login to use the bookmarking feature.

6 Strategies for Writing Arguments

Over the years, three major modes have dominated academic writing—narrative, explanatory, and argument. Traditionally, writing teachers have devoted equal attention to the Big Three in that order, but modern standards place argument writing at the head of the pack. Why?

A push for rigor may explain the shift. Argument writing requires clear, logical thinking and the know-how to appeal to readers' needs. Clearly, such communication skills come at a premium in today’s information economy, and developing those skills will help students flourish in school and the workplace.

But many developing writers struggle to write clear and compelling arguments. You can help them succeed by teaching the following strategies.

1. Distinguishing Argumentation from Persuasion

National writing standards and the tests that assess them focus on argumentation rather than persuasion. In practice, these approaches overlap more than they diverge, but students should understand the subtle difference between them.

- Persuasion appeals to readers' emotions to make them believe something or take specific action. Advertising uses persuasion.

- Argumentation uses logic and evidence to build a case for a specific claim. Science and law use argumentation.

You can help your students understand the difference between the two by presenting Distinguishing Argumentation from Persuasion .

2. Forming an Opinion Statement

Your students’ message will not make a full impact without a clear main claim or opinion statement. Reading arguments with a missing claim statement is like driving through fog; you're never quite sure where you're headed.

Present Developing an Opinion Statement to help students write a main claim for their argument. In this minilesson, students follow a simple formula to develop a claim of truth, value, or policy.

3. Appealing to the Audience

Once students state a claim, how can they support it in a way that appeals to skeptical readers? Aristotle outlined three types of rhetorical appeals. The first two work best in argumentation and the third in persuasion.

- The appeal to logos means providing clear thinking and solid reasoning to support claims (using logic).

- The appeal to ethos means building trust by citing reputable sources, providing factual evidence, and fairly presenting the issue (using ethics).

- The appeal to pathos means persuading by connecting to readers’ emotions (tugging "heartstrings").

Assign Making Rhetorical Appeals to help students choose supporting details that will appeal logically and ethically (argumentation) or emotionally (persuasion).

4. Connecting with Anecdotes

Though argumentation should de-emphasize emotional appeals, it still should connect to readers on a human level. As Thomas Newkirk advises in Minds Made for Stories , “Any argument that fails to appeal to the emotions, values, hopes, fears, self-interest, or identity of any audience is doomed to fail.”

Apt anecdotes allow students to add interest and emotive impact to their writing. Give students practice Using Anecdotes in Formal Writing , and encourage them to add appropriate anecdotes to connect to readers.

5. Answering Objections

Students' arguments lose steam when they ignore key opposing ideas. Help them realize that addressing readers' disagreements does not weaken their arguments, but in fact strengthens them. Introduce these two ways to respond to opposing points of view.

- Counterarguments point out a flaw or weakness in the objection (without belittling the person who is objecting).

- Concessions admit the value of an opposing viewpoint, but quickly pivot back to the writer's side of the argument.

Then present Answering Objections in Arguments .

6. Avoiding Logical Fallacies

An effective argument uses clear and logical thinking. Sometimes, though, students get so eager to fight for a point of view that they accidently (or intentionally) make misleading or illogical claims to prove their points. You can help students look for and avoid fuzzy thinking by introducing common logical fallacies in the following minilessons:

- Recognizing Logical Fallacies 1

- Recognizing Logical Fallacies 2

Closing Thoughts

These six strategies can help your students write stronger and more convincing argument papers. Also know that many of the skills you teach during your narrative and explanatory units will translate well to argument writing. Sometimes an argument needs a touch of description, a careful analysis, or even a poetic turn of phrase. Good writing is good writing.

Want more ideas for argument writing?

- Share 7 C’s For Building a Rock-Solid Argument .

- Browse 15 Awesome Persuasive Writing Prompts .

- Explore the handbooks in our K-12 writing program for full and grade-specific support for argument writing.

- Look out for future blog posts from the team at Thoughtful Learning.

Teacher Support:

Click to find out more about this resource.

Standards Correlations:

The State Standards provide a way to evaluate your students' performance.

- 110.36.c.10.C

- 110.37.c.10.C

- LAFS.910.W.1.1

- LA 10.2.1.b

- LA 10.2.2.a

- 110.36.c.9.B.i

- 110.36.c.9.B.ii

- 110.37.c.9.B.i

- 110.37.c.9.B.ii

- 110.36.c.7.E

- LA 10.2.1.c

- LA 10.2.2.b

- 110.38.c.10.C

- 110.39.c.10.C

- LAFS.1112.W.1.1

- LA 12.2.1.b

- LA 12.2.2.a

- 110.38.c.5.J

- 110.39.c.5.J

- 110.38.c.9.C

- 110.39.c.9.C

Related Resources

All resources.

- 15 Engaging Explanatory Writing Prompts

- 15 Awesome Persuasive Writing Prompts

- Distinguishing Argumentation from Persuasion

- Ways to Maximize Learning in English Language Arts

- Of Personal Importance: How Narration Drives Meaningful Writing

- Writing Character Analyses

- Writing Literary Analyses

- Inquire Online Middle School Classroom Set

- Inquire Online Middle School Teacher's Guide

- Write on Course 20-20

- Inquire Middle School Teacher's Guide

- Inquire Middle School

- Inquire Elementary Teacher's Guide

- Inquire Elementary

8 Effective Strategies to Write Argumentative Essays

In a bustling university town, there lived a student named Alex. Popular for creativity and wit, one challenge seemed insurmountable for Alex– the dreaded argumentative essay!

One gloomy afternoon, as the rain tapped against the window pane, Alex sat at his cluttered desk, staring at a blank document on the computer screen. The assignment loomed large: a 350-600-word argumentative essay on a topic of their choice . With a sigh, he decided to seek help of mentor, Professor Mitchell, who was known for his passion for writing.

Entering Professor Mitchell’s office was like stepping into a treasure of knowledge. Bookshelves lined every wall, faint aroma of old manuscripts in the air and sticky notes over the wall. Alex took a deep breath and knocked on his door.

“Ah, Alex,” Professor Mitchell greeted with a warm smile. “What brings you here today?”

Alex confessed his struggles with the argumentative essay. After hearing his concerns, Professor Mitchell said, “Ah, the argumentative essay! Don’t worry, Let’s take a look at it together.” As he guided Alex to the corner shelf, Alex asked,

Table of Contents

“What is an Argumentative Essay?”

The professor replied, “An argumentative essay is a type of academic writing that presents a clear argument or a firm position on a contentious issue. Unlike other forms of essays, such as descriptive or narrative essays, these essays require you to take a stance, present evidence, and convince your audience of the validity of your viewpoint with supporting evidence. A well-crafted argumentative essay relies on concrete facts and supporting evidence rather than merely expressing the author’s personal opinions . Furthermore, these essays demand comprehensive research on the chosen topic and typically follows a structured format consisting of three primary sections: an introductory paragraph, three body paragraphs, and a concluding paragraph.”

He continued, “Argumentative essays are written in a wide range of subject areas, reflecting their applicability across disciplines. They are written in different subject areas like literature and philosophy, history, science and technology, political science, psychology, economics and so on.

Alex asked,

“When is an Argumentative Essay Written?”

The professor answered, “Argumentative essays are often assigned in academic settings, but they can also be written for various other purposes, such as editorials, opinion pieces, or blog posts. Some situations to write argumentative essays include:

1. Academic assignments

In school or college, teachers may assign argumentative essays as part of coursework. It help students to develop critical thinking and persuasive writing skills .

2. Debates and discussions

Argumentative essays can serve as the basis for debates or discussions in academic or competitive settings. Moreover, they provide a structured way to present and defend your viewpoint.

3. Opinion pieces

Newspapers, magazines, and online publications often feature opinion pieces that present an argument on a current issue or topic to influence public opinion.

4. Policy proposals

In government and policy-related fields, argumentative essays are used to propose and defend specific policy changes or solutions to societal problems.

5. Persuasive speeches

Before delivering a persuasive speech, it’s common to prepare an argumentative essay as a foundation for your presentation.

Regardless of the context, an argumentative essay should present a clear thesis statement , provide evidence and reasoning to support your position, address counterarguments, and conclude with a compelling summary of your main points. The goal is to persuade readers or listeners to accept your viewpoint or at least consider it seriously.”

Handing over a book, the professor continued, “Take a look on the elements or structure of an argumentative essay.”

Elements of an Argumentative Essay

An argumentative essay comprises five essential components:

Claim in argumentative writing is the central argument or viewpoint that the writer aims to establish and defend throughout the essay. A claim must assert your position on an issue and must be arguable. It can guide the entire argument.

2. Evidence

Evidence must consist of factual information, data, examples, or expert opinions that support the claim. Also, it lends credibility by strengthening the writer’s position.

3. Counterarguments

Presenting a counterclaim demonstrates fairness and awareness of alternative perspectives.

4. Rebuttal

After presenting the counterclaim, the writer refutes it by offering counterarguments or providing evidence that weakens the opposing viewpoint. It shows that the writer has considered multiple perspectives and is prepared to defend their position.

The format of an argumentative essay typically follows the structure to ensure clarity and effectiveness in presenting an argument.

How to Write An Argumentative Essay

Here’s a step-by-step guide on how to write an argumentative essay:

1. Introduction

- Begin with a compelling sentence or question to grab the reader’s attention.

- Provide context for the issue, including relevant facts, statistics, or historical background.

- Provide a concise thesis statement to present your position on the topic.

2. Body Paragraphs (usually three or more)

- Start each paragraph with a clear and focused topic sentence that relates to your thesis statement.

- Furthermore, provide evidence and explain the facts, statistics, examples, expert opinions, and quotations from credible sources that supports your thesis.

- Use transition sentences to smoothly move from one point to the next.

3. Counterargument and Rebuttal

- Acknowledge opposing viewpoints or potential objections to your argument.

- Also, address these counterarguments with evidence and explain why they do not weaken your position.

4. Conclusion

- Restate your thesis statement and summarize the key points you’ve made in the body of the essay.

- Leave the reader with a final thought, call to action, or broader implication related to the topic.

5. Citations and References

- Properly cite all the sources you use in your essay using a consistent citation style.

- Also, include a bibliography or works cited at the end of your essay.

6. Formatting and Style

- Follow any specific formatting guidelines provided by your instructor or institution.

- Use a professional and academic tone in your writing and edit your essay to avoid content, spelling and grammar mistakes .

Remember that the specific requirements for formatting an argumentative essay may vary depending on your instructor’s guidelines or the citation style you’re using (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago). Always check the assignment instructions or style guide for any additional requirements or variations in formatting.

Did you understand what Prof. Mitchell explained Alex? Check it now!

Fill the Details to Check Your Score

Prof. Mitchell continued, “An argumentative essay can adopt various approaches when dealing with opposing perspectives. It may offer a balanced presentation of both sides, providing equal weight to each, or it may advocate more strongly for one side while still acknowledging the existence of opposing views.” As Alex listened carefully to the Professor’s thoughts, his eyes fell on a page with examples of argumentative essay.

Example of an Argumentative Essay

Alex picked the book and read the example. It helped him to understand the concept. Furthermore, he could now connect better to the elements and steps of the essay which Prof. Mitchell had mentioned earlier. Aren’t you keen to know how an argumentative essay should be like? Here is an example of a well-crafted argumentative essay , which was read by Alex. After Alex finished reading the example, the professor turned the page and continued, “Check this page to know the importance of writing an argumentative essay in developing skills of an individual.”

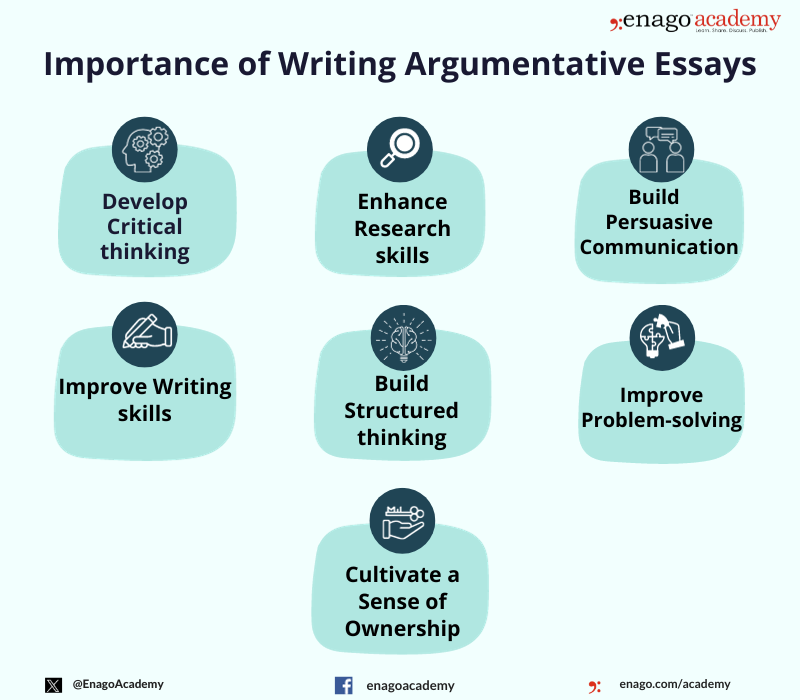

Importance of an Argumentative Essay

After understanding the benefits, Alex was convinced by the ability of the argumentative essays in advocating one’s beliefs and favor the author’s position. Alex asked,

“How are argumentative essays different from the other types?”

Prof. Mitchell answered, “Argumentative essays differ from other types of essays primarily in their purpose, structure, and approach in presenting information. Unlike expository essays, argumentative essays persuade the reader to adopt a particular point of view or take a specific action on a controversial issue. Furthermore, they differ from descriptive essays by not focusing vividly on describing a topic. Also, they are less engaging through storytelling as compared to the narrative essays.

Alex said, “Given the direct and persuasive nature of argumentative essays, can you suggest some strategies to write an effective argumentative essay?

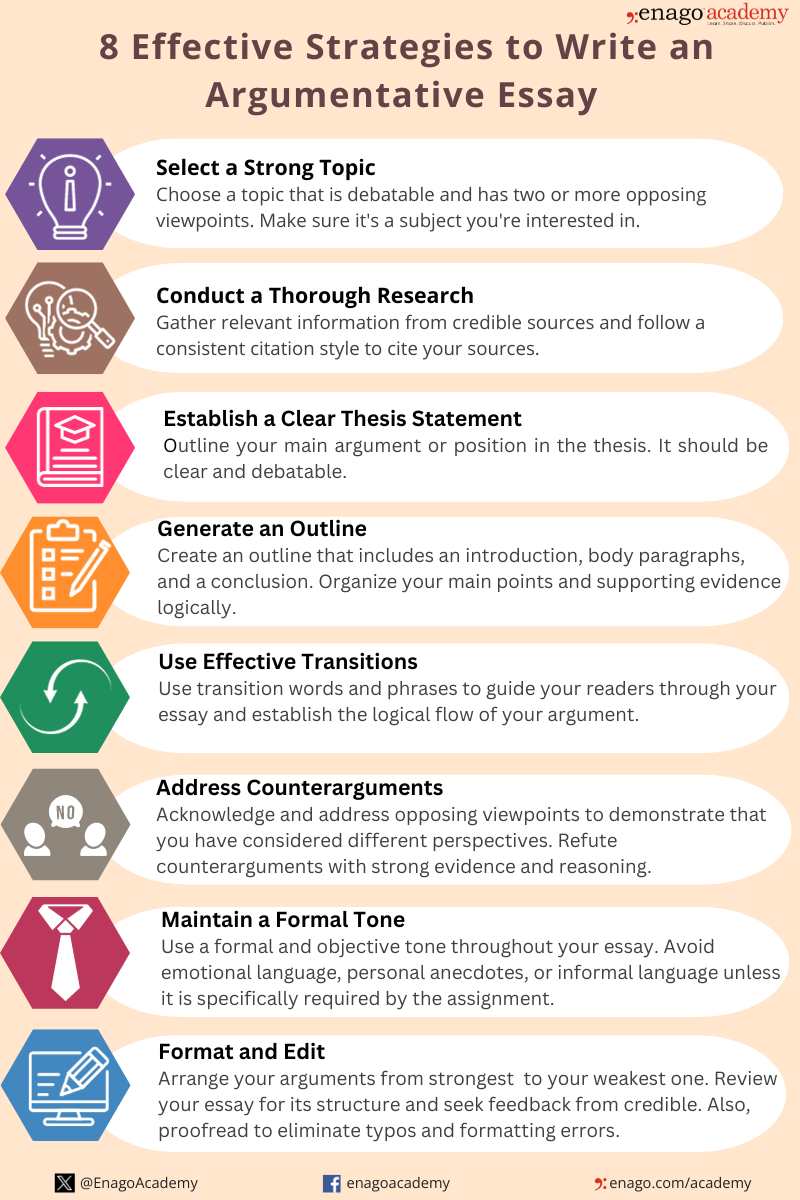

Turning the pages of the book, Prof. Mitchell replied, “Sure! You can check this infographic to get some tips for writing an argumentative essay.”

Effective Strategies to Write an Argumentative Essay

As days turned into weeks, Alex diligently worked on his essay. He researched, gathered evidence, and refined his thesis. It was a long and challenging journey, filled with countless drafts and revisions.

Finally, the day arrived when Alex submitted their essay. As he clicked the “Submit” button, a sense of accomplishment washed over him. He realized that the argumentative essay, while challenging, had improved his critical thinking and transformed him into a more confident writer. Furthermore, Alex received feedback from his professor, a mix of praise and constructive criticism. It was a humbling experience, a reminder that every journey has its obstacles and opportunities for growth.

Frequently Asked Questions

An argumentative essay can be written as follows- 1. Choose a Topic 2. Research and Collect Evidences 3. Develop a Clear Thesis Statement 4. Outline Your Essay- Introduction, Body Paragraphs and Conclusion 5. Revise and Edit 6. Format and Cite Sources 7. Final Review

One must choose a clear, concise and specific statement as a claim. It must be debatable and establish your position. Avoid using ambiguous or unclear while making a claim. To strengthen your claim, address potential counterarguments or opposing viewpoints. Additionally, use persuasive language and rhetoric to make your claim more compelling

Starting an argument essay effectively is crucial to engage your readers and establish the context for your argument. Here’s how you can start an argument essay are: 1. Begin With an Engaging Hook 2. Provide Background Information 3. Present Your Thesis Statement 4. Briefly Outline Your Main 5. Establish Your Credibility

The key features of an argumentative essay are: 1. Clear and Specific Thesis Statement 2. Credible Evidence 3. Counterarguments 4. Structured Body Paragraph 5. Logical Flow 6. Use of Persuasive Techniques 7. Formal Language

An argumentative essay typically consists of the following main parts or sections: 1. Introduction 2. Body Paragraphs 3. Counterargument and Rebuttal 4. Conclusion 5. References (if applicable)

The main purpose of an argumentative essay is to persuade the reader to accept or agree with a particular viewpoint or position on a controversial or debatable topic. In other words, the primary goal of an argumentative essay is to convince the audience that the author's argument or thesis statement is valid, logical, and well-supported by evidence and reasoning.

Great article! The topic is simplified well! Keep up the good work

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Reporting Research

Reassessing the Lab Environment to Create an Equitable and Inclusive Space

The pursuit of scientific discovery has long been fueled by diverse minds and perspectives. Yet…

- AI in Academia

- Trending Now

Simplifying the Literature Review Journey — A comparative analysis of 6 AI summarization tools

Imagine having to skim through and read mountains of research papers and books, only to…

- Publishing Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

How to Improve Lab Report Writing: Best practices to follow with and without AI-assistance

Imagine you’re a scientist who just made a ground-breaking discovery! You want to share your…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

How to Improve Lab Report Writing: Best practices to follow with and without…

Digital Citations: A comprehensive guide to citing of websites in APA, MLA, and CMOS…

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

What should universities' stance be on AI tools in research and academic writing?

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Write an Argumentative Essay

4-minute read

- 30th April 2022

An argumentative essay is a structured, compelling piece of writing where an author clearly defines their stance on a specific topic. This is a very popular style of writing assigned to students at schools, colleges, and universities. Learn the steps to researching, structuring, and writing an effective argumentative essay below.

Requirements of an Argumentative Essay

To effectively achieve its purpose, an argumentative essay must contain:

● A concise thesis statement that introduces readers to the central argument of the essay

● A clear, logical, argument that engages readers

● Ample research and evidence that supports your argument

Approaches to Use in Your Argumentative Essay

1. classical.

● Clearly present the central argument.

● Outline your opinion.

● Provide enough evidence to support your theory.

2. Toulmin

● State your claim.

● Supply the evidence for your stance.

● Explain how these findings support the argument.

● Include and discuss any limitations of your belief.

3. Rogerian

● Explain the opposing stance of your argument.

● Discuss the problems with adopting this viewpoint.

● Offer your position on the matter.

● Provide reasons for why yours is the more beneficial stance.

● Include a potential compromise for the topic at hand.

Tips for Writing a Well-Written Argumentative Essay

● Introduce your topic in a bold, direct, and engaging manner to captivate your readers and encourage them to keep reading.

● Provide sufficient evidence to justify your argument and convince readers to adopt this point of view.

● Consider, include, and fairly present all sides of the topic.

● Structure your argument in a clear, logical manner that helps your readers to understand your thought process.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● Discuss any counterarguments that might be posed.

● Use persuasive writing that’s appropriate for your target audience and motivates them to agree with you.

Steps to Write an Argumentative Essay

Follow these basic steps to write a powerful and meaningful argumentative essay :

Step 1: Choose a topic that you’re passionate about

If you’ve already been given a topic to write about, pick a stance that resonates deeply with you. This will shine through in your writing, make the research process easier, and positively influence the outcome of your argument.

Step 2: Conduct ample research to prove the validity of your argument

To write an emotive argumentative essay , finding enough research to support your theory is a must. You’ll need solid evidence to convince readers to agree with your take on the matter. You’ll also need to logically organize the research so that it naturally convinces readers of your viewpoint and leaves no room for questioning.

Step 3: Follow a simple, easy-to-follow structure and compile your essay

A good structure to ensure a well-written and effective argumentative essay includes:

Introduction

● Introduce your topic.

● Offer background information on the claim.

● Discuss the evidence you’ll present to support your argument.

● State your thesis statement, a one-to-two sentence summary of your claim.

● This is the section where you’ll develop and expand on your argument.

● It should be split into three or four coherent paragraphs, with each one presenting its own idea.

● Start each paragraph with a topic sentence that indicates why readers should adopt your belief or stance.

● Include your research, statistics, citations, and other supporting evidence.

● Discuss opposing viewpoints and why they’re invalid.

● This part typically consists of one paragraph.

● Summarize your research and the findings that were presented.

● Emphasize your initial thesis statement.

● Persuade readers to agree with your stance.

We certainly hope that you feel inspired to use these tips when writing your next argumentative essay . And, if you’re currently elbow-deep in writing one, consider submitting a free sample to us once it’s completed. Our expert team of editors can help ensure that it’s concise, error-free, and effective!

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

The benefits of using an online proofreading service.

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

2-minute read

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

What Is Market Research?

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

8 Press Release Distribution Services for Your Business

In a world where you need to stand out, press releases are key to being...

3-minute read

How to Get a Patent

In the United States, the US Patent and Trademarks Office issues patents. In the United...

The 5 Best Ecommerce Website Design Tools

A visually appealing and user-friendly website is essential for success in today’s competitive ecommerce landscape....

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

How to Write an Argumentative Essay: Step By Step Guide

10 May, 2020

9 minutes read

Author: Tomas White

Being able to present your argument and carry your point in a debate or a discussion is a vital skill. No wonder educational establishments make writing compositions of such type a priority for all students. If you are not really good at delivering a persuasive message to the audience, this guide is for you. It will teach you how to write an argumentative essay successfully step by step. So, read on and pick up the essential knowledge.

What is an Argumentative Essay?

An argumentative essay is a paper that gets the reader to recognize the author’s side of the argument as valid. The purpose of this specific essay is to pose a question and answer it with compelling evidence. At its core, this essay type works to champion a specific viewpoint. The key, however, is that the topic of the argumentative essay has multiple sides, which can be explained, weighed, and judged by relevant sources.

Check out our ultimate argumentative essay topics list!

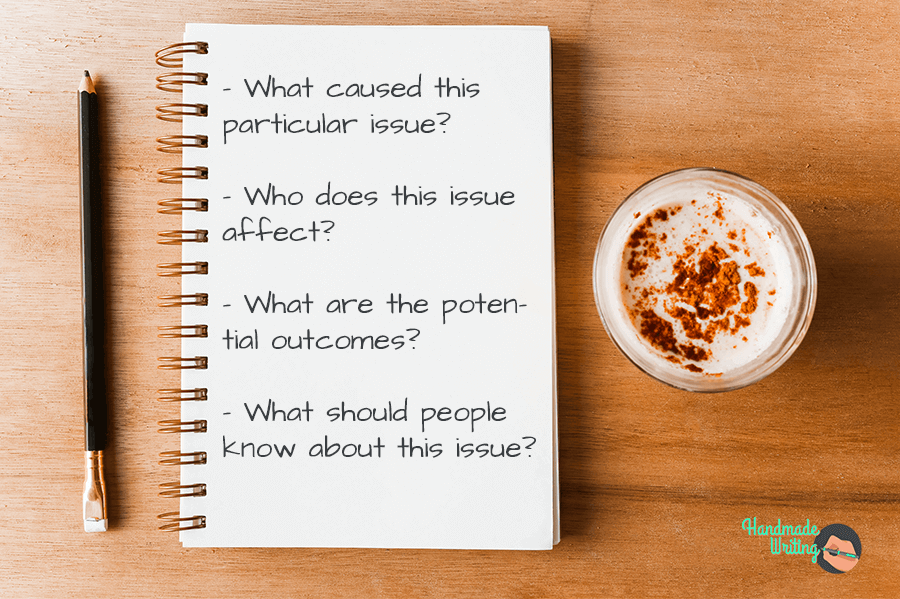

This essay often explores common questions associated with any type of argument including:

Argumentative VS Persuasive Essay

It’s important not to confuse argumentative essay with a persuasive essay – while they both seem to follow the same goal, their methods are slightly different. While the persuasive essay is here to convince the reader (to pick your side), the argumentative essay is here to present information that supports the claim.

In simple words, it explains why the author picked this side of the argument, and persuasive essay does its best to persuade the reader to agree with your point of view.

Now that we got this straight, let’s get right to our topic – how to write an argumentative essay. As you can easily recognize, it all starts with a proper argument. First, let’s define the types of argument available and strategies that you can follow.

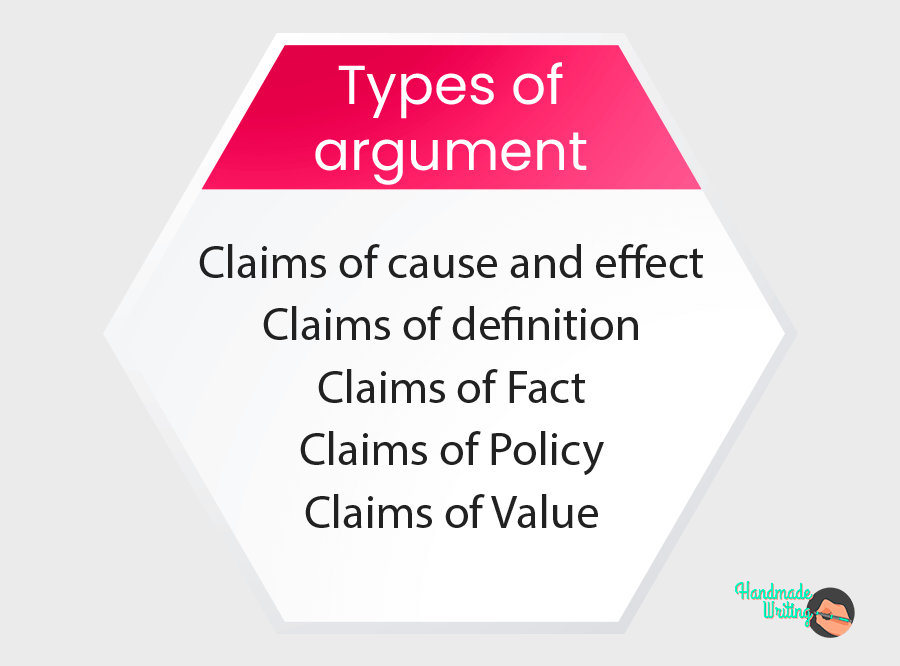

Types of Argument

When delving into the types of argument, the vocabulary suddenly becomes quite “lawyerish”; and that makes sense since lawyers stake their whole livelihood on their ability to win arguments. So step into your lawyer shoes, and learn about the five kinds of arguments that you could explore in an argumentative paper:

Claims of cause and effect

This paper focuses on answering what caused the issue(s), and what the resulting effects have been.

Claims of definition

This paper explores a controversial interpretation of a particular definition; the paper delves into what the world really means and how it could be interpreted in different ways.

Claims of Fact

This argumentative paper examines whether a particular fact is accurate; it often looks at several sources reporting a fact and examines their veracity.

Claims of Policy

This is a favorite argumentative essay in government and sociology classes; this paper explores a particular policy, who it affects, and what (if anything) should be done about it.

Claims of Value

This essay identifies a particular value or belief and then examines how and why it is important to a particular cohort or a larger, general population.

The aim of argument, or of discussion, should not be victory, but progress. Joseph Joubert

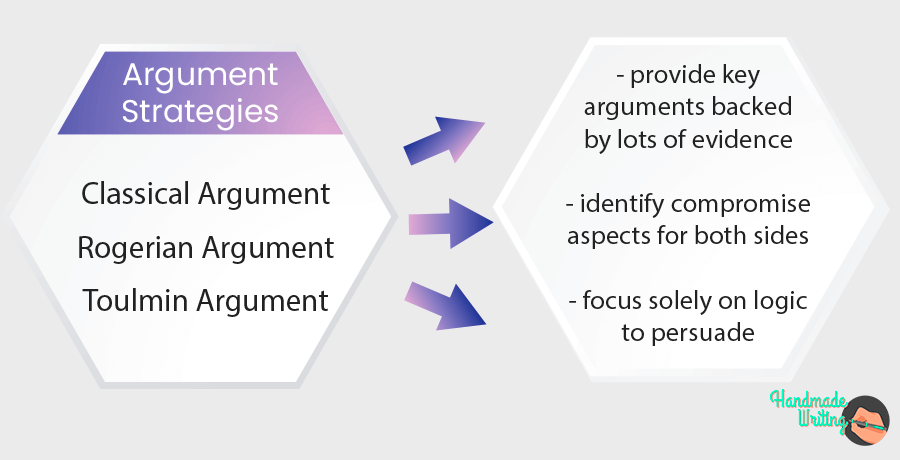

Argument Strategies

When mulling over how to approach your argumentative assignment, you should be aware that three main argument strategies exist regarding how exactly to argue an issue: classical, Rogerian, Toulmin.

Classical Argument

This argument structure dates back to the ancient Greeks and Romans. In this strategy, the arguer introduces the issue, provides context, clearly states their claim, provides key arguments backed by lots of evidence, and nullifies opposing arguments with valid data.

Rogerian Argument

Hate conflict? This may be the argumentative paper strategy for you. At its core, this strategy works to identify compromise aspects for both sides; this approach works to find commonality and an ultimate agreement between two sides rather than proclaiming a winner or loser. The focus in this argument is compromise and respect of all sides.

Toulmin Argument

Remember Spock? This is his type of strategy; the Toulmin approach focuses solely on logic to persuade the audience. It is heavy on data and often relies on qualities to narrow the focus of a claim and strengthen the writer’s stance. This approach also tends to rely on exceptions, which clearly set limits on the parameters of an argument, thus making a particular stance easier to agree with.

With that in mind, we can now organize our argument into the essay structure.

Have no time to write your essay? You can buy argumentative essay tasks at Handmade Writing. Our service is available 24/7.

Argumentative essay Example

Organizing the argumentative essay outline.

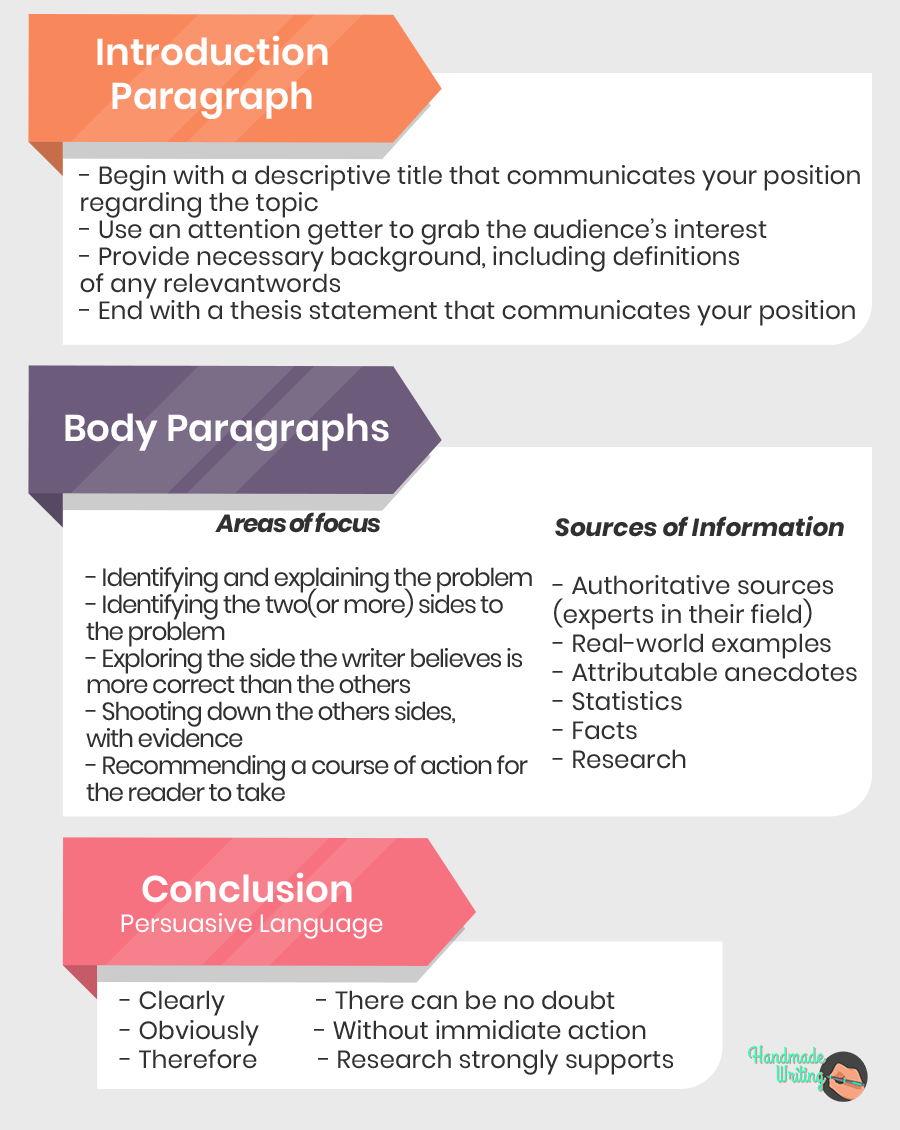

An argumentative essay follows the typical essay format: introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion. However, the body paragraphs are structured a bit differently from other body paragraphs. Surely, not something you can see in a cause and effect essay outline .

While the introduction should still begin with an attention-grabbing sentence that catches the reader’s interest and compels him or her to continue reading and provides key background information, the following paragraphs focus on specific aspects of the argument.

Let’s begin with the introduction.

Related Post: How to write an Essay Introduction ?

Introduction Paragraph

As its name suggests, this paragraph provides all the background information necessary for a reader unfamiliar with the argumentative essay topic to understand what it’s about. A solid introduction should:

- Begin with a descriptive title that communicates your position regarding the topic

- Rhetorical question

- Personal anecdote

- Provide necessary background, including definitions of any relevant words

- End with a thesis statement that communicates your position

Stuck with your essay task? No more struggle! HandMadeWriting is the top essay writing service. Our online essay writer service not only guides you on writing papers, it can write a high-quality essay for you.

Body Paragraphs

Body paragraphs can range in size from six to fifteen or more sentences. The goal of these paragraphs is to support the thesis statement. Recommended areas of focus for the body paragraphs within an argumentative paper include:

- Identifying and explaining the problem

- Identifying the two (or more) sides to the problem

- Exploring the side the writer believes is more appropriate than the others

- Shooting down the other sides, with evidence

- Recommending a course of action for the reader

One important way how this essay differs from other kinds is its specific nature. At the end of reading such an essay, the audience should clearly understand the issue or controversy and have enough information to make an informed decision regarding the issue. But what compels an audience make an informed decision? Several things!

- Authoritative sources (experts in their field)

- Real-world examples

- Attributable anecdotes

In this paragraph, often the shortest of all the paragraphs, the writer reviews his or her most compelling reasons for taking a particular stance on an issue. The persuasion should be strong here, and the writer should use combative language including examples such as:

- “then” statements

- There can be no doubt

- Without immediate action

- Research strongly supports

It is also appropriate to refute potential opposition in the conclusion. By stating the objections readers could have, and show why they should be dismissed; the conclusion resonates more strongly with the reader.

Check our guide if you have any other questions on academic paper writing!

Argumentative Essay Sample

Be sure to check the sample essay, completed by our writers. Use it as an example to write your own argumentative essay. Link: Argumentative essay on white rappers’ moral rights to perform .

Remember : the key to winning any argument should be reliable sources — the better, the more trustworthy your sources, the more likely the audience will consider a viewpoint different from their own.

And while you may feel a deep passion towards a particular topic, keep in mind that emotions can be messy; this essay should present all sides to the argument respectfully and with a clear intention to portray each of them fairly.

Let the data, statistics, and facts speak loudly and clearly for themselves. And don’t forget to use opinionated language — using such diction is a must in any strong argumentative writing!

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

- SAT BootCamp

- SAT MasterClass

- SAT Private Tutoring

- SAT Proctored Practice Test

- ACT Private Tutoring

- Academic Subjects

- College Essay Workshop

- Academic Writing Workshop

- AP English FRQ BootCamp

- 1:1 College Essay Help

- Online Instruction

- Free Resources

12 Essential Steps for Writing an Argumentative Essay (with 10 example essays)

Bonus Material: 10 complete example essays

Writing an essay can often feel like a Herculean task. How do you go from a prompt… to pages of beautifully-written and clearly-supported writing?

This 12-step method is for students who want to write a great essay that makes a clear argument.

In fact, using the strategies from this post, in just 88 minutes, one of our students revised her C+ draft to an A.

If you’re interested in learning how to write awesome argumentative essays and improve your writing grades, this post will teach you exactly how to do it.

First, grab our download so you can follow along with the complete examples.

Then keep reading to see all 12 essential steps to writing a great essay.

Download 10 example essays

Why you need to have a plan

One of the most common mistakes that students make when writing is to just dive in haphazardly without a plan.

Writing is a bit like cooking. If you’re making a meal, would you start throwing ingredients at random into a pot? Probably not!

Instead, you’d probably start by thinking about what you want to cook. Then you’d gather the ingredients, and go to the store if you don’t already have them in your kitchen. Then you’d follow a recipe, step by step, to make your meal.

Here’s our 12-step recipe for writing a great argumentative essay:

- Pick a topic

- Choose your research sources

- Read your sources and take notes

- Create a thesis statement

- Choose three main arguments to support your thesis statement —now you have a skeleton outline

- Populate your outline with the research that supports each argument

- Do more research if necessary

- Add your own analysis

- Add transitions and concluding sentences to each paragraph

- Write an introduction and conclusion for your essay

- Add citations and bibliography

Grab our download to see the complete example at every stage, along with 9 great student essays. Then let’s go through the steps together and write an A+ essay!

1. Pick a topic

Sometimes you might be assigned a topic by your instructor, but often you’ll have to come up with your own idea!

If you don’t pick the right topic, you can be setting yourself up for failure.

Be careful that your topic is something that’s actually arguable —it has more than one side. Check out our carefully-vetted list of 99 topic ideas .

Let’s pick the topic of laboratory animals . Our question is should animals be used for testing and research ?

Download our set of 10 great example essays to jump to the finished version of this essay.

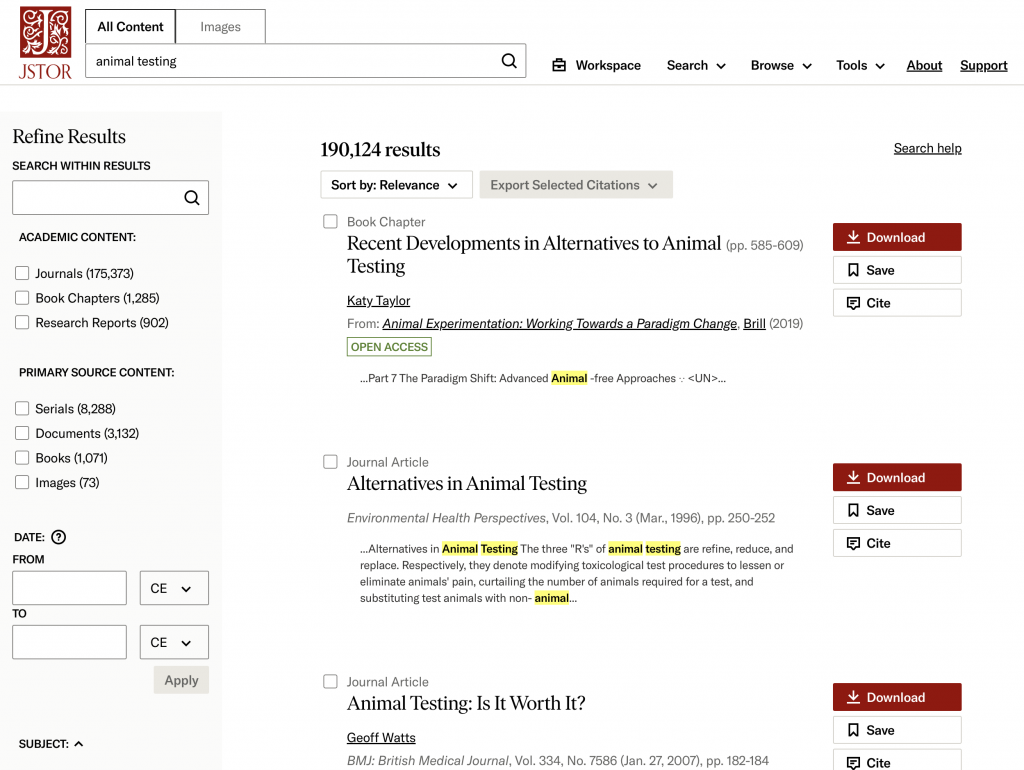

2. Choose your research sources

One of the big differences between the way an academic argumentative essay and the version of the assignment that you may have done in elementary school is that for an academic argumentative essay, we need to support our arguments with evidence .

Where do we get that evidence?

Let’s be honest, we all are likely to start with Google and Wikipedia.

Now, Wikipedia can be a useful starting place if you don’t know very much about a topic, but don’t use Wikipedia as your main source of evidence for your essay.

Instead, look for reputable sources that you can show to your readers as proof of your arguments. It can be helpful to read some sources from either side of your issue.

Look for recently-published sources (within the last 20 years), unless there’s a specific reason to do otherwise.

Good places to look for sources are:

- Books published by academic presses

- Academic journals

- Academic databases like JSTOR and EBSCO

- Nationally-published newspapers and magazines like The New York Times or The Atlantic

- Websites and publications of national institutions like the NIH

- Websites and publications of universities

Some of these sources are typically behind a paywall. This can be frustrating when you’re a middle-school or high-school student.

However, there are often ways to get access to these sources. Librarians (at your school library or local public library) can be fantastic resources, and they can often help you find a copy of the article or book you want to read. In particular, librarians can help you use Interlibrary Loan to order books or journals to your local library!

More and more scientists and other researchers are trying to publish their articles for free online, in order to encourage the free exchange of knowledge. Check out respected open-access platforms like arxiv.org and PLOS ONE .

How do you find these sources?

If you have access to an academic database like JSTOR or EBSCO , that’s a great place to start.

Everyone can use Google Scholar to search for articles. This is a powerful tool and highly recommended!

Of course, if there’s a term you come across that you don’t recognize, you can always just Google it!

How many sources do you need? That depends on the length of your essay and on the assignment. If your instructor doesn’t give you any other guidance, assume that you should have at least three good sources.

For our topic of animal research, here’s a few sources that we could assemble:

Geoff Watts. “Animal Testing: Is It Worth It?” BMJ: British Medical Journal , Jan. 27, 2007, Vol. 334, No. 7586 (Jan. 27, 2007), pp. 182-184.

Kim Bartel Sheehan and Joonghwa Lee. “What’s Cruel About Cruelty Free: An Exploration of Consumers, Moral Heuristics, and Public Policy.” Journal of Animal Ethics , Vol. 4, No. 2 (Fall 2014), pp. 1-15.

Justin Goodman, Alka Chandna and Katherine Roe. “Trends in animal use at US research facilities.” Journal of Medical Ethics , July 2015, Vol. 41, No. 7 (July 2015), pp. 567-569.

Katy Taylor. “Recent Developments in Alternatives to Animal Testing.” In Animal Experimentation: Working Towards a Paradigm Change . Brill 2019.

Thomas Hartung. “Research and Testing Without Animals: Where Are We Now and Where Are We Heading?” In Animal Experimentation: Working Towards a Paradigm Change . Brill 2019.

Bonus: download 10 example essays now .

3. Read your sources and take notes

Once you have a nice pile of sources, it’s time to read them!

As we read, we want to take notes that will be useful to us later as we write our essay.

We want to be careful to keep the source’s ideas separate from our own ideas . Come up with a system to clearly mark the difference as you’re taking notes: use different colors, or use little arrows to represent the ideas that are yours and not the source’s ideas.

We can use this structure to keep notes in an organized way:

Download a template for these research notes here .

For our topic of animal research, our notes might look something like this:

Grab our download to read the rest of the notes and see more examples of how to do thoughtful research!

4. Create a thesis

What major themes did you find in your reading? What did you find most interesting or convincing?

Now is the point when you need to pick a side on your topic, if you haven’t already done so. Now that you’ve read more about the issue, what do you think? Write down your position on the issue:

Animal testing is necessary but should be reduced.

Next, it’s time to add more detail to your thesis. What reasons do you have to support that position? Add those to your sentence.

Animal testing is necessary but should be reduced by eliminating testing for cosmetics, ensuring that any testing is scientifically sound, and replacing animal models with other methods as much as possible.

Add qualifiers to refine your position. Are there situations in which your position would not apply? Or are there other conditions that need to be met?

For our topic of animal research, our final thesis statement (with lead-in) might look something like this:

The argument: Animal testing and research should not be abolished, as doing so would upend important medical research and substance testing. However, scientific advances mean that in many situations animal testing can be replaced by other methods that not only avoid the ethical problems of animal testing, but also are less costly and more accurate. Governments and other regulatory bodies should further regulate animal testing to outlaw testing for cosmetics and other recreational products, ensure that the tests conducted are both necessary and scientifically rigorous, and encourage the replacement of animal use with other methods whenever possible.

The highlighted bit at the end is the thesis statement, but the lead-in is useful to help us set up the argument—and having it there already will make writing our introduction easier!

The thesis statement is the single most important sentence of your essay. Without a strong thesis, there’s no chance of writing a great essay. Read more about it here .

See how nine real students wrote great thesis statements in 9 example essays now.

5. Create three supporting arguments

Think of three good arguments why your position is true. We’re going to make each one into a body paragraph of your essay.

For now, write them out as 1–2 sentences. These will be topic sentences for each body paragraph.

For our essay about animal testing, it might look like this:

Supporting argument #1: For ethical reasons, animal testing should not be allowed for cosmetics and recreational products.

Supporting argument #2: The tests that are conducted with animals should be both necessary (for the greater good) and scientifically rigorous—which isn’t always the case currently. This should be regulated by governments and institutions.

Supporting argument #3: Governments and institutions should do more to encourage the replacement of animal testing with other methods.

Optional: Find a counterargument and respond to it

Think of a potential counterargument to your position. Consider writing a fourth paragraph anticipating this counterargument, or find a way to include it in your other body paragraphs.

For our essay, that might be:

Possible counterargument: Animal testing is unethical and should not be used in any circumstances.

Response to the counterargument: Animal testing is deeply entrenched in many research projects and medical procedures. Abruptly ceasing animal testing would upend the scientific and medical communities. But there are many ways that animal testing could be reduced.

With these three arguments, a counterargument, and a thesis, we now have a skeleton outline! See each step of this essay in full in our handy download .

6. Start populating your outline with the evidence you found in your research

Look through your research. What did you find that would support each of your three arguments?

Copy and paste those quotes or paraphrases into the outline. Make sure that each one is annotated so that you know which source it came from!

Ideally you already started thinking about these sources when you were doing your research—that’s the ideas in the rightmost column of our research template. Use this stuff too!

A good rule of thumb would be to use at least three pieces of evidence per body paragraph.

Think about in what order it would make most sense to present your points. Rearrange your quotes accordingly! As you reorder them, feel free to start adding short sentences indicating the flow of ideas .

For our essay about animal testing, part of our populated outline might look something like:

Argument #1: For ethical reasons, animal testing should not be allowed for cosmetics and recreational products.

Lots of animals are used for testing and research.

In the US, about 22 million animals were used annually in the early 1990s, mostly rodents (BMJ 1993, 1020).

But there are ethical problems with using animals in laboratory settings. Opinions about the divide between humans and animals might be shifting.

McIsaac refers to “the essential moral dilemma: how to balance the welfare of humans with the welfare of other species” (Hubel, McIsaac 29).

The fundamental legal texts used to justify animal use in biomedical research were created after WWII, and drew a clear line between experiments on animals and on humans. The Nuremburg Code states that “the experiment should be so designed and based on the results of animal experimentation and a knowledge of the natural history of the disease or other problem under study that the anticipated results will justify the performance of the experiment” (Ferrari, 197). The 1964 Declaration of the World Medical Association on the Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects (known as the Helsinki Declaration) states that “Medical research involving human subjects must conform to generally accepted scientific principles, be based on a thorough knowledge of the scientific literature, other relevant sources of information, and adequate laboratory and, as appropriate, animal experimentation. The welfare of animals used for research must be respected” (Ferrari, 197).

→ Context? The Nuremberg Code is a set of ethical research principles, developed in 1947 in the wake of Nazi atrocities during WWII, specifically the inhumane and often fatal experimentation on human subjects without consent.

“Since the 1970s, the animal-rights movement has challenged the use of animals in modern Western society by rejecting the idea of dominion of human beings over nature and animals and stressing the intrinsic value and rights of individual animals” (van Roten, 539, referencing works by Singer, Clark, Regan, and Jasper and Nelkin).

“The old (animal) model simply does not fully meet the needs of scientific and economic progress; it fails in cost, speed, level of detail of understanding, and human relevance. On top of this, animal experimentation lacks acceptance by an ethically evolving society” (Hartung, 682).

Knight’s article summarizes negative impacts on laboratory animals—invasive procedures, stress, pain, and death (Knight, 333). These aren’t very widely or clearly reported (Knight, 333). → Reading about these definitely produces an emotional reaction—they sound bad.

Given this context, it makes sense to ban animal testing in situations where it’s just for recreational products like cosmetics.

Fortunately, animal testing for cosmetics is less common than we might think.

A Gallup poll published in 1990 found that 14% of people thought that the most frequent reason for using animals to test cosmetics for safety—but figures from the UK Home Office in 1991 found that less than 1% of animals were used for tests for cosmetics and toiletries (BMJ 1993, 1019). → So in the early 1990s there was a big difference between what people thought was happening and what actually was happening!

But it still happens, and there are very few regulations of it (apart from in the EU).

Because there are many definitions of the phrase “cruelty-free,” many companies “can (and do) use the term when the product or its ingredients were indeed tested on animals” (Sheehan and Lee, 1).

The authors compare “cruelty-free” to the term “fair trade.” There is an independent inspection and certification group (Flo-Cert) that reviews products labeled as “fair trade,” but there’s no analogous process for “cruelty-free” (Sheehan and Lee, 2). → So anyone can just put that label on a product? Apparently, apart from in the European Union. That seems really easy to abuse for marketing purposes.

Companies can also hire outside firms to test products and ingredients on animals (Sheehan and Lee, 3).

Animal testing for recreational, non-medical purposes should be banned, like it is in the EU.

Download the full example outline here .

7. Do more research if necessary

Occasionally you might realize that there’s a hole in your research, and you don’t have enough evidence to support one of your points.

In this situation, either change your argument to fit the evidence that you do have, or do a bit more research to fill the hole!

For example, looking at our outline for argument #1 for our essay on animal testing, it’s clear that this paragraph is missing a small but crucial bit of evidence—a reference to this specific ban on animal testing for cosmetics in Europe. Time for a bit more research!

A visit to the official website of the European Commission yields a copy of the law, which we can add to our populated outline:

“The cosmetics directive provides the regulatory framework for the phasing out of animal testing for cosmetics purposes. Specifically, it establishes (1) a testing ban – prohibition to test finished cosmetic products and cosmetic ingredients on animals, and (2) a marketing ban – prohibition to market finished cosmetic products and ingredients in the EU which were tested on animals. The same provisions are contained in the cosmetics regulation , which replaced the cosmetics directive as of 11 July 2013. The testing ban on finished cosmetic products applies since 11 September 2004. The testing ban on ingredients or combination of ingredients applies since 11 March 2009. The marketing ban applies since 11 March 2009 for all human health effects with the exception of repeated-dose toxicity, reproductive toxicity, and toxicokinetics. For these specific health effects, the marketing ban applies since 11 March 2013, irrespective of the availability of alternative non-animal tests.” (website of the European Commission, “Ban on animal testing”)

Alright, now this supporting argument has the necessary ingredients!

You don’t need to use all of the evidence that you found in your research. In fact, you probably won’t use all of it!

This part of the writing process requires you to think critically about your arguments and what evidence is relevant to your points .

8. Add your own analysis and synthesis of these points

Once you’ve organized your evidence and decided what you want to use for your essay, now you get to start adding your own analysis!

You may have already started synthesizing and evaluating your sources when you were doing your research (the stuff on the right-hand side of our template). This gives you a great starting place!

For each piece of evidence, follow this formula:

- Context and transitions: introduce your piece of evidence and any relevant background info and signal the logical flow of ideas

- Reproduce the paraphrase or direct quote (with citation )

- Explanation : explain what the quote/paraphrase means in your own words

- Analysis : analyze how this piece of evidence proves your thesis

- Relate it back to the thesis: don’t forget to relate this point back to your overarching thesis!

If you follow this fool-proof formula as you write, you will create clear, well-evidenced arguments.

As you get more experienced, you might stray a bit from the formula—but a good essay will always intermix evidence with explanation and analysis, and will always contain signposts back to the thesis throughout.

For our essay about animal testing, our first body paragraph might look like:

Every year, millions of animals—mostly rodents—are used for testing and research (BMJ 1993, 1020) . This testing poses an ethical dilemma: “how to balance the welfare of humans with the welfare of other species” (Hubel, McIsaac 29) . Many of the fundamental legal tests that are used to justify animal use in biomedical research were created in wake of the horrors of World War II, when the Nazi regime engaged in terrible experimentation on their human prisoners. In response to these atrocities, philosophers and lawmakers drew a clear line between experimenting on humans without consent and experimenting on (non-human) animals. For example, the 1947 Nuremberg Code stated that “the experiment should be so designed and based on the results of animal experimentation and a knowledge of the natural history of the disease or other problem under study that the anticipated results will justify the performance of the experiment” (Ferrari, 197) . Created two years after the war, the code established a set of ethical research principles to demarcate ethical differences between animals and humans, clarifying differences between Nazi atrocities and more everyday research practices. However, in the following decades, the animal-rights movement has challenged the philosophical boundaries between humans and animals and questioned humanity’s right to exert dominion over animals (van Roten, 539, referencing works by Singer, Clark, Regan, and Jasper and Nelkin) . These concerns are not without justification, as animals used in laboratories are subject to invasive procedures, stress, pain, and death (Knight, 333) . Indeed, reading detailed descriptions of this research can be difficult to stomach . In light of this, while some animal testing that contributes to vital medical research and ultimately saves millions of lives may be ethically justified, animal testing that is purely for recreational purposes like cosmetics cannot be ethically justified . Fortunately, animal testing for cosmetics is less common than we might think . In 1990, a poll found that 14% of people in the UK thought that the most frequent reason for using animals to test cosmetics for safety—but actual figures were less than 1% (BMJ 1993, 1019) . Unfortunately, animal testing for cosmetics is not subject to very much regulation . In particular, companies can use the phrase “cruelty-free” to mean just about anything, and many companies “can (and do) use the term when the product or its ingredients were indeed tested on animals” (Sheehan and Lee, 1) . Unlike the term “fair trade,” which has an independent inspection and certification group (Flo-Cert) that reviews products using the label, there’s no analogous process for “cruelty-free” (Sheehan and Lee, 2) . Without regulation, the term is regularly abused by marketers . Companies can also hire outside firms to test products and ingredients on animals and thereby pass the blame (Sheehan and Lee, 3) . Consumers trying to avoid products tested on animals are frequently tricked . Greater regulation of terms would help, but the only way to end this kind of deceit will be to ban animal testing for recreational, non-medical purposes . The European Union is the only governmental body yet to accomplish this . In a series of regulations, the EU first banned testing finished cosmetic products (2004), then testing ingredients or marketing products which were tested on animals (2009); exceptions for specific health effects ended in 2013 (website of the European Commission, “Ban on animal testing”) . The result is that the EU bans testing cosmetic ingredients or finished cosmetic products on animals, as well as marketing any cosmetic ingredients and products which were tested on animals elsewhere (Regulation 1223/2009/EU, known as the “Cosmetics Regulation”) . The rest of the world should follow this example and ban animal testing on cosmetic ingredients and products, which do not contribute significantly to the greater good and therefore cannot outweigh the cost to animal lives .

Edit down the quotes/paraphrases as you go. In many cases, you might copy out a great long quote from a source…but only end up using a few words of it as a direct quote, or you might only paraphrase it!

There were several good quotes in our previous step that just didn’t end up fitting here. That’s fine!

Take a look at the words and phrases highlighted in red. Notice how sometimes a single word can help to provide necessary context and create a logical transition for a new idea. Don’t forget the transitions! These words and phrases are essential to good writing.

The end of the paragraph should very clearly tie back to the thesis statement.

As you write, consider your audience

If it’s not specified in your assignment prompt, it’s always appropriate to ask your instructor who the intended audience of your essay or paper might be. (Your instructor will usually be impressed by this question!)

If you don’t get any specific guidance, imagine that your audience is the typical readership of a newspaper like the New York Times —people who are generally educated, but who don’t have any specialized knowledge of the specific subject, especially if it’s more technical.

That means that you should explain any words or phrases that aren’t everyday terminology!

Equally important, you don’t want to leave logical leaps for your readers to make. Connect all of the dots for them!

See the other body paragraphs of this essay, along with 9 student essays, here .

9. Add paragraph transitions and concluding sentences to each body paragraph

By now you should have at least three strong body paragraphs, each one with 3–5 pieces of evidence plus your own analysis and synthesis of the evidence.

Each paragraph has a main topic sentence, which we wrote back when we made the outline. This is a good time to check that the topic sentences still match what the rest of the paragraph says!

Think about how these arguments relate to each other. What is the most logical order for them? Re-order your paragraphs if necessary.

Then add a few sentences at the end of each paragraph and/or the beginning of the next paragraph to connect these ideas. This step is often the difference between an okay essay and a really great one!

You want your essay to have a great flow. We didn’t worry about this at the beginning of our writing, but now is the time to start improving the flow of ideas!

10. The final additions: write an introduction and a conclusion

Follow this formula to write a great introduction:

- It begins with some kind of “hook”: this can be an anecdote, quote, statistic, provocative statement, question, etc.

(Pro tip: don’t use phrases like “throughout history,” “since the dawn of humankind,” etc. It’s good to think broadly, but you don’t have to make generalizations for all of history.)

- It gives some background information that is relevant to understand the ethical dilemma or debate

- It has a lead-up to the thesis

- At the end of the introduction, the thesis is clearly stated

This makes a smooth funnel that starts more broadly and smoothly zeroes in on the specific argument.

Your conclusion is kind of like your introduction, but in reverse. It starts with your thesis and ends a little more broadly.

For the conclusion, try and summarize your entire argument without being redundant. Start by restating your thesis but with slightly different wording . Then summarize each of your main points.

If you can, it’s nice to point to the larger significance of the issue. What are the potential consequences of this issue? What are some future directions for it to go in? What remains to be explored?

See how nine students wrote introductions in different styles here .

11. Add citations and bibliography

Check what bibliographic style your instructor wants you to use. If this isn’t clearly stated, it’s a good question to ask them!

Typically the instructions will say something like “Chicago style,” “APA,” etc., or they’ll give you their own rules.

These rules will dictate how exactly you’ll write your citations in the body of your essay (either in parentheses after the quote/paraphrase or else with a footnote or endnote) and how you’ll write your “works cited” with the full bibliographic information at the end.

Follow these rules! The most important thing is to be consistent and clear.

Pro tip: if you’re struggling with this step, your librarians can often help! They’re literally pros at this. 🙂

Now you have a complete draft!

Read it from beginning to end. Does it make sense? Are there any orphan quotes or paraphrases that aren’t clearly explained? Are there any abrupt changes of topic? Fix it!

Are there any problems with grammar or spelling ? Fix them!

Edit for clarity.

Ideally, you’ll finish your draft at least a few days before it’s due to be submitted. Give it a break for a day or two, and then come back to it. Things to be revised are more likely to jump out after a little break!

Try reading your essay out loud. Are there any sentences that don’t sound quite right? Rewrite them!

Double-check your thesis statement. This is the make-or-break moment of your essay, and without a clear thesis it’s pretty impossible for an essay to be a great one. Is it:

- Arguable: it’s not just the facts—someone could disagree with this position

- Narrow & specific: don’t pick a position that’s so broad you could never back it up

- Complex: show that you are thinking deeply—one way to do this is to consider objections/qualifiers in your thesis

Try giving your essay to a friend or family member to read. Sometimes (if you’re lucky) your instructors will offer to read a draft if you turn it in early. What feedback do they have? Edit accordingly!