Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Classical Argument

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This resource describes the fundamental qualities of argument developed by Aristotle in the vital rhetorical text On Rhetoric.

A (Very) Brief History of Rhetoric

The study of rhetoric has existed for thousands of years, predating even Socrates, Plato and the other ancient Greek philosophers that we often credit as the founders of Western philosophy. Although ancient rhetoric is most commonly associated with the ancient Greeks and Romans, early examples of rhetoric date all the way back to ancient Akkadian writings in Mesopotamia.

In ancient Greece and Rome, rhetoric was most often considered to be the art of persuasion and was primarily described as a spoken skill. In these societies, discourse occurred almost exclusively in the public sphere, so learning the art of effective, convincing speaking was essential for public orators, legal experts, politicians, philosophers, generals, and educators. To prepare for the speeches they would need to make in these roles, students engaged in written exercises called progymnasmata . Today, rhetorical scholars still use strategies from the classical era to conceptualize argument. However, whereas oral discourse was the main focus of the classical rhetoricians, modern scholars also study the peculiarities of written argument.

Aristotle provides a crucial point of reference for ancient and modern scholars alike. Over 2000 years ago, Aristotle literally wrote the book on rhetoric. His text Rhētorikḗ ( On Rhetoric ) explores the techniques and purposes of persuasion in ancient Greece, laying the foundation for the study and implementation of rhetoric in future generations. Though the ways we communicate and conceptualize rhetoric have changed, many of the principles in this book are still used today. And this is for good reason: Aristotle’s strategies can provide a great guide for organizing your thoughts as well as writing effective arguments, essays, and speeches.

Below, you will find a brief guide to some of the most fundamental concepts in classical rhetoric, most of which originate in On Rhetoric.

The Rhetorical Appeals

To understand how argument works in On Rhetoric , you must first understand the major appeals associated with rhetoric. Aristotle identifies four major rhetorical appeals: ethos (credibility), logos (logic), pathos (emotion), and Kairos(time).

- Ethos – persuasion through the author's character or credibility. This is the way a speaker (or writer) presents herself to the audience. You can build credibility by citing professional sources, using content-specific language, and by showing evidence of your ethical, knowledgeable background.

- Logos – persuasion through logic. This is the way a speaker appeals to the audience through practicality and hard evidence. You can develop logos by presenting data, statistics, or facts by crafting a clear claim with a logically-sequenced argument. ( See enthymeme and syllogism )

- Pathos – persuasion through emotion or disposition . This is the way a speaker appeals to the audience through emotion, pity, passions, or dispositions. The idea is usually to evoke and strengthen feelings already present within the audience. This can be achieved through story-telling, vivid imagery, and an impassioned voice. Academic arguments in particular benefit from understanding pathos as appealing to an audience's academic disposition on a given topic, subject, or argument.

- Kairos – an appeal made through the adept use of time. This is the way a speaker appeals to the audience through notions of time. It is also considered to be the appropriate or opportune time for a speaker to insert herself into a conversation or discourse, using the three appeals listed above. A Kairotic appeal can be made through calls to immediate action, presenting an opportunity as temporary, and by describing a specific moment as propitious or ideal.

*Note: When using these terms in a Rhetorical Analysis, make sure your syntax is correct. One does not appeal to ethos, logos, or pathos directly. Rather, one appeals to an audience's emotion/disposition, reason/logic, or sense of the author's character/credibility within the text. Ethos, pathos, and logos are themselves the appeals an author uses to persuade an audience.

An easy way to conceptualize the rhetorical appeals is through advertisements, particularly infomercials or commercials. We are constantly being exposed to the types of rhetoric above, whether it be while watching television or movies, browsing the internet, or watching videos on YouTube.

Imagine a commercial for a new car. The commercial opens with images of a family driving a brand-new car through rugged, forested terrain, over large rocks, past waterfalls, and finally to a serene camping spot near a tranquil lake surrounded by giant redwood trees. The scene cuts to shots of the interior of the car, showing off its technological capacities and its impressive spaciousness. A voiceover announces that not only has this car won numerous awards over its competitors but that it is also priced considerably lower than comparable models, while getting better gas mileage. “But don’t wait,” the voiceover says excitedly, “current lessees pay 0% APR financing for 12 months.”

In just a few moments, this commercial has shown masterful use of all four appeals. The commercial utilizes pathos by appealing to our romantic notions of family, escape, and the great outdoors. The commercial develops ethos by listing its awards, and it appeals to our logical tendencies by pointing out we will save money immediately because the car is priced lower than its competitors, as well as in the long run because of its higher MPG rate. Finally, the commercial provides an opportune and propitious moment for its targeted audience to purchase a car immediately.

Depending on the nature of the text, argument, or conversation, one appeal will likely become most dominant, but rhetoric is generally most effective when the speaker or writer draws on multiple appeals to work in conjunction with one another. To learn more about Aristotle's rhetorical appeals, click here.

Components and Structure

The classical argument is made up of five components, which are most commonly composed in the following order:

- Exordium – The introduction, opening, or hook.

- Narratio – The context or background of the topic.

- Proposito and Partitio – The claim/stance and the argument.

- Confirmatio and/or Refutatio – positive proofs and negative proofs of support.

- Peroratio – The conclusion and call to action.

Think of the exordium as your introduction or “hook.” In your exordium, you have an opportunity to gain the interest of your reader, but you also have the responsibility of situating the argument and setting the tone of your writing. That is, you should find a way to appeal to the audience’s interest while also introducing the topic and its importance in a professional and considerate manner. Something to include in this section is the significance of discussing the topic in this given moment (Kairos). This provides the issue a sense of urgency that can validate your argument.

This is also a good opportunity to consider who your intended audience is and to address their concerns within the context of the argument. For example, if you were writing an argument on the importance of technology in the English classroom and your intended audience was the board of a local high school, you might consider the following:

- New learning possibilities for students (General Audience Concerns)

- The necessity of modern technology in finding new, up-to-date information (Hook/Kairos)

- Detailed narrative of how technology in one school vastly improved student literacy (Hook/Pathos)

- Statistics showing a link between exposure to technology and rising trends in literacy (Hook/Logos)

- Quotes from education and technology professors expressing an urgency for technology in English classrooms (Hook/Ethos)

Of course, you probably should not include all of these types of appeals in the opening section of your argument—if you do, you may end up with a boring, overlong introduction that doesn’t function well as a hook. Instead, consider using some of these points as evidence later on. Ask yourself: What will be most important to my audience? What information will most likely result in the action I want to bring about? Think about which appeal will work best to gain the attention of your intended audience and start there.

The narratio provides relevant foundational information and describes the social context in which your topic exists. This might include information on the historical background, including recent changes or updates to the topic, social perception, important events, and other academic research. This helps to establish the rhetorical situation for the argument: that is, the situation the argument is currently in, as impacted by events, people, opinion, and urgency of some kind. For your argument on technology in the English classroom, you might include:

- Advances in education-related technology over the centuries

- Recent trends in education technology

- A description of the importance of digital literacy

- Statistics documenting the lack of home technology for many students

- A selection of expert opinions on the usefulness of technology in all classrooms

Providing this type of information creates the setting for your argument. In other words, it provides the place and purpose for the argument to take place. By situating your argument within in a viable context, you create an opportunity to assert yourself into the discussion, as well as to give your reader a genuine understanding of your topic’s importance.

Propositio and Partitio

These two concepts function together to help set up your argument. You can think of them functioning together to form a single thesis. The propositio informs your audience of your stance, and the partitio lays out your argument. In other words, the propositio tells your audience what you think about a topic, and the partitio briefly explains why you think that way and how you will prove your point.

Because this section helps to set up the rest of your argument, you should place it near the beginning of your paper. Keep in mind, however, that you should not give away all of your information or evidence in your partitio. This section should be fairly short: perhaps 3-4 sentences at most for most academic essays. You can think of this section of your argument like the trailer for a new film: it should be concise, should entice the audience, and should give them a good example of what they are going to experience, but it shouldn’t include every detail. Just as a filmgoer must see an entire film to gain an understanding of its significance or quality, so too must your audience read the rest of your argument to truly understand its depth and scope.

In the case of your argument on implementing technology in the English classroom, it’s important to think not only of your own motivations for pursuing this technology in the classroom, but also of what will motivate or persuade your respective audience(s). Some writing contexts call for an audience of one. Some require consideration of multiple audiences, in which case you must find ways to craft an argument which appeals to each member of your audience. For example, if your audience included a school board as well as parents andteachers, your propositio might look something like this:

“The introduction of newer digital technology in the English classroom would be beneficial for all parties involved. Students are already engaged in all kinds of technological spaces, and it is important to implement teaching practices that invest students’ interests and prior knowledge. Not only would the marriage of English studies and technology extend pedagogical opportunities, it would also create an ease of instruction for teachers, engage students in creative learning environments, and familiarize students with the creation and sharing technologies that they will be expected to use at their future colleges and careers. Plus, recent studies suggest a correlation between exposure to technology and higher literacy rates, a trend many education professionals say isn’t going to change.”

Note how the above paragraph considers the concerns and motivations of all three audience members, takes a stance, and provides support for the stance in a way that allows for the rest of the argument to grow from its ideas. Keep in mind that whatever you promise in your propositio and partitio (in this case the new teaching practices, literacy statistics, and professional opinion) must appear in the body of your argument. Don’t make any claims here that you cannot prove later in your argument.

Confirmatio and Refutatio

These two represent different types of proofs that you will need to consider when crafting your argument. The confirmatio and refutatio work in opposite ways, but are both very effective in strengthening your claims. Luckily, both words are cognates—words that sound/look in similar in multiple languages—and are therefore are easy to keep straight. Confirmatio is a way to confirm your claims and is considered a positive proof; refutatio is a way to acknowledge and refute a counterclaim and is considered a negative proof.

The confirmatio is your argument’s support: the evidence that helps to support your claims. For your argument on technology in the English classroom, you might include the following:

- Students grades drastically increase when technology is inserted into academics

- Teachers widely agree that students are more engaged in classroom activities that involve technology

- Students who accepted to elite colleges generally possess strong technological skills

The refutatio provides negative proofs. This is an opportunity for you to acknowledge that other opinions exist and have merit, while also showing why those claims do not warrant rejecting your argument.

If you feel strange including information that seems to undermine or weaken your own claims, ask yourself this: have you ever been in a debate with someone who entirely disregarded every point you tried to make without considering the credibility of what you said? Did this make their argument less convincing? That’s what your paper can look like if you don’t acknowledge that other opinions indeed exist and warrant attention.

After acknowledging an opposing viewpoint, you have two options. You can either concede the point (that is, admit that the point is valid and you can find no fault with their reasoning), or you can refute their claim by pointing out the flaws in your opponent’s argument. For example, if your opponent were to argue that technology is likely to distract students more than help them (an argument you’d be sure to include in your argument so as not to seem ignorant of opposing views) you’d have two options:

- Concession: You might concede this point by saying “Despite all of the potential for positive learning provided by technology, proponents of more traditional classroom materials point out the distractive possibilities that such technology would introduce into the classroom. They argue that distractions such as computer games, social media, and music-streaming services would only get in the way of learning.”

In your concession of the argument, you acknowledge the merit of the opposing argument, but you should still try to flip the evidence in a positive way. Note how before conceding we include “despite all of the potential for positive learning.” This reminds your reader that, although you are conceding a single point, there are still many reasons to side with you.

- Refutation: To refute this same point you might say something like, “While proponents of more traditional English classrooms express concerns about student distraction, it’s important to realize that in modern times, students are already distracted by the technology they carry around in their pockets. By redirecting student attention to the technology administered by the school, this distraction is shifted to class content. Plus, with website and app blocking resources available to schools, it is simple for an institution to simply decide which websites and apps to ban and block, thereby ensuring students are on task.”

Note how we acknowledged the opposing argument, but immediately pointed out its flaws using straightforward logic and a counterexample. In so doing, we effectively strengthen our argument and move forward with our proposal.

Your peroratio is your conclusion. This is your final opportunity to make an impact in your essay and leave an impression on your audience. In this section, you are expected to summarize and re-evaluate everything you have proven throughout your argument. However, there are multiple ways of doing this. Depending on the topic of your essay, you might employ one or more of the following in your closing:

- Call to action (encourage your audience to do something that will change the situation or topic you have been discussing).

- Discuss the implications for the future. What might happen if things continue the way they are going? Is this good or bad? Try to be impactful without being overly dramatic.

- Discuss other related topics that warrant further research and discussion.

- Make a historical parallel regarding a similar issue that can help to strengthen your argument.

- Urge a continued conversation of the topic for the future.

Remember that your peroratio is the last impression your audience will have of your argument. Be sure to consider carefully which rhetorical appeals to employ to gain a desirable effect. Make sure also to summarize your findings, including the most effective and emphatic pieces of evidence from your argument, reassert your major claim, and end on a compelling, memorable note. Good luck and happy arguing!

A Classical Teacher's Journal

Essay writing #4: the classical argument.

The second essay format I teach my students is the classical argument. It is more advanced than the simple argument for a number of reasons.

To begin with, the thesis in a classical argument is debatable in a consequential way, meaning there is something at stake. That something might be political, social, religious, or any number of things that affect the broader world. Given this substantive nature, the argument often requires outside research as opposed to simply one’s own personal analysis. Finally, in order to lend authority to one’s position, the essay format spells out and refutes the opposing position .

In a middle school classroom like mine, I might use a simple argument for analysis of King Arthur but a classical argument for analysis of the justice of the Crusades. Given their complicated history and enduring legacy, a meaningful position on the Crusades requires research and attention to a vast array of conflicting viewpoints.

As I explain to my students, a classical argument is more than “I think this about such and such.” It’s also, “You should think this, too.” It’s clearly a persuasive argument because it tries to draw people to the writer’s viewpoint and dispel any doubt that other views could be correct.

The essay structure itself consists of five parts, which support a single thesis statement through deductive writing , meaning they begin with the thesis statement and then move on to support it.

PART ONE – THE INTRODUCTION AND THESIS STATEMENT

Happily, the introduction of a classical argument models the same format as that of a simple argument. It introduces the topic to be discussed and presents the thesis statement . I instruct students to limit themselves to approximately 3-5 sentences. The brevity of the opening paragraph is one of its strengths and should not be compromised by extraneous information.

This paragraph consists of three parts. The first is the opening sentence itself. This should typically consist of a simple statement of fact, especially for students who are just learning to write an essay for the first time. More “provocative” openings like questions or startling facts are a lot harder to pull off, and I recommend new writers avoid them.

The second part of the opening paragraph offers transitional background information and justification for why the topic is relevant.

Well-done transitional sentences pave the way for the final part of the opening, which is the one-sentence thesis itself, or the position the essay takes. I always remind students that the thesis should be something debatable much like an opinion. In other words, it is not simply a fact.

PART TWO – THE NARRATION

This part of the essay establishes context for the argument . First, it tells the story, so to speak, behind the essay. That story might be the history of a war or the facts of a case or some other relevant background.

Next, it addresses the reality that there are opposing views about the subject matter. It should state what those views are without actually getting into the arguments for either position. That will come later.

Finally, the narration makes a type of appeal to the reader, letting him know what is at stake in the essay and asking him to weigh each side carefully.

There is no set number of sentences, but a good paragraph of 8-10 sentences usually does it for middle school students. More advanced writers might write several paragraphs in this part.

PART THREE – THE CONFIRMATION

Much like the body of a simple argument, the confirmation presents the evidence to support the thesis. It should have a topic sentence, at least three pieces of thoroughly explained evidence, and a concluding sentence that clearly ties the confirmation back to the thesis.

Again, a good paragraph of 8-10 sentences is ideal for middle school students, but more advanced writers might have several paragraphs in this section as well. .

PART FOUR – THE REFUTATION AND CONCESSION

With careful planning, this part of the essay is often the strongest because it allows the writer to dismiss all, or nearly all, of the opposition’s claims .

It should have a topic sentence followed by as many objections as the writer can come up with. If there are areas where the opposition may have a good point, the writer should concede that but without giving full weight to their overall position. Finally, this part of the essay should have a concluding sentence that relates back to the thesis.

The refutation and concession should mirror the confirmation in structure and length.

PART FIVE – THE CONCLUSION

Its purpose is to drive home the thesis statement by casting its relevance more broadly than what was initially presented in the introduction and narration.

Beginning writers often erroneously think of a conclusion as a restatement of what has already been said. Though this might work on a basic level, it represents only a superficial understanding of the key purpose of the conclusion and tends to be boring.

I find it helpful to refer to the conclusion as the “so what” part of the essay . We often think of it in terms of the broad lessons we learned from exploring an argument in a specific context. In other words, it is the student’s opportunity to reiterate what is at stake in the argument.

The conclusion should be divided into three parts, inversely mirroring the introduction . It, too, should be relatively short but powerful.

The first part of the conclusion recalls the thesis but presents it in a new way. I refer to this as a “thesis with a twist.” The second part provides transitional information on the connection between the thesis and the stakes at play in the argument. The final part is broader still, typically consisting of only one or two sentences, and should press the moral imperative of making the “right” choice for “the world.”

A REMINDER ABOUT PROCESS

If the writing process is important for the simple argument, it is all the more important for the classical argument, which is far more complicated.

From using Socratic discussions and disputations, to developing a thesis, to outlining the argument, to writing it out, every phase needs thorough, well-planned attention. Any breakdown in the writing process can greatly undermine the strength of the argument, and it shows all the more in this essay format.

Conversely, careful adherence to the process results in a persuasive argument even if the writing is wanting in style and beauty.

The classical argument, when followed properly, is as full-proof of a persuasive format as it gets. Naturally, there will be many readers who are not convinced in the end, but they will at least have to concede that the argument is convincing.

First image courtesy of the New York Public Library, New York

Second image courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Writing Center

- Current Students

- Online Only Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Parents & Family

- Alumni & Friends

- Community & Business

- Student Life

- Video Introduction

- Become a Writing Assistant

- All Writers

- Graduate Students

- ELL Students

- Campus and Community

- Testimonials

- Encouraging Writing Center Use

- Incentives and Requirements

- Open Educational Resources

- How We Help

- Get to Know Us

- Conversation Partners Program

- Workshop Series

- Professors Talk Writing

- Computer Lab

- Starting a Writing Center

- A Note to Instructors

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review

- Research Proposal

- Argument Essay

- Rhetorical Analysis

Aristotelian Argument

The Aristotelian or classical argument is a style of argument developed by the famous Greek philosopher and rhetorician, Aristotle. In this style of argument, your goal as a writer is to convince your audience of something. The goal is to use a series of strategies to persuade your audience to adopt your side of the issue. Although ethos, pathos, and logos play a role in any argument, this style of argument utilizes them in the most persuasive ways possible.

Of course, your professor may require some variations, but here is the basic format for an Aristotelian, or classical, argumentative essay:

- Introduce your issue. At the end of your introduction, most professors will ask you to present your thesis. The idea is to present your readers with your main point and then dig into it.

- Present your case by explaining the issue in detail and why something must be done or a way of thinking is not working. This will take place over several paragraphs.

- Address the opposition. Use a few paragraphs to explain the other side. Refute the opposition one point at a time.

- Provide your proof. After you address the other side, you’ll want to provide clear evidence that your side is the best side.

- Present your conclusion. In your conclusion, you should remind your readers of your main point or thesis and summarize the key points of your argument. If you are arguing for some kind of change, this is a good place to give your audience a call to action. Tell them what they could do to make a change.

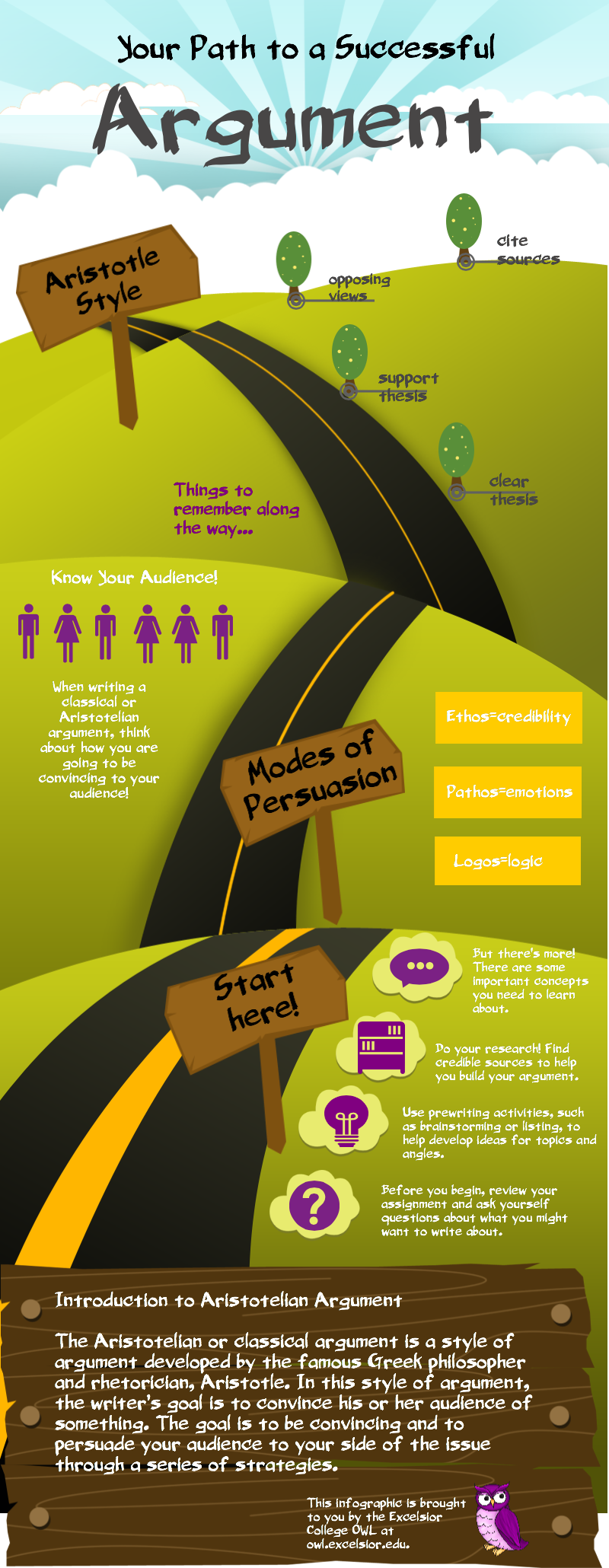

Aristotelian Infographic

Introduction to Aristotelian Argument

The Aristotelian or classical argument is a style of argument developed by the famous Greek philosopher and rhetorician, Aristotle. In this style of argument, the writer’s goal is to be convincing and to persuade your audience to your side of the issue through a series of strategies.

Start here!

Before you begin, review your assignment and ask yourself questions about what you might want to write about.

Use prewriting activities, such as brainstorming or listing, to help develop ideas for topics and angles.

Do your research! Find credible sources to help you build your argument.

But there’s more! There are some important concepts you need to learn about.

Modes of Persuasion

Ethos=credibility

Pathos=emotions

Logos=logic

Know Your Audience!

When writing a classical or Aristotelian argument, think about how you are going to be convincing to your audience!

Things to remember along the way…

Clear thesis

Support thesis

Opposing views

Cite sources

Sample Aristotelian Argument

Now that you have had the chance to learn about Aristotle and a classical style of argument, it’s time to see what an Aristotelian argument might look like. Below, you’ll see a sample argumentative essay, written according to APA 7th edition guidelines, with a particular emphasis on Aristotelian elements.

Download here the sample paper. In the sample, the strategies and techniques the author used have been noted for you.

This content was originally created by Excelsior Online Writing Lab (OWL) and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-4.0 International License . You are free to use, adapt, and/or share this material as long as you properly attribute. Please keep this information on materials you use, adapt, and/or share for attribution purposes.

Contact Info

Kennesaw Campus 1000 Chastain Road Kennesaw, GA 30144

Marietta Campus 1100 South Marietta Pkwy Marietta, GA 30060

Campus Maps

Phone 470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

kennesaw.edu/info

Media Resources

Resources For

Related Links

- Financial Aid

- Degrees, Majors & Programs

- Job Opportunities

- Campus Security

- Global Education

- Sustainability

- Accessibility

470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

© 2024 Kennesaw State University. All Rights Reserved.

- Privacy Statement

- Accreditation

- Emergency Information

- Reporting Hotline

- Open Records

- Human Trafficking Notice

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

60 Aristotelian (Classical) Argument Model

Aristotelian argument.

The Aristotelian or classical argument is a style of argument developed by the famous Greek philosopher and rhetorician, Aristotle . In this style of argument, your goal as a writer is to convince your audience of something. The goal is to use a series of strategies to persuade your audience to adopt your side of the issue. Although ethos , pathos , and logos play a role in any argument, this style of argument utilizes them in the most persuasive ways possible.

Of course, your professor may require some variations, but here is the basic format for an Aristotelian, or classical, argumentative essay:

- Introduce your issue. At the end of your introduction, most professors will ask you to present your thesis. The idea is to present your readers with your main point and then dig into it.

- Present your case by explaining the issue in detail and why something must be done or a way of thinking is not working. This will take place over several paragraphs.

- Address the opposition. Use a few paragraphs to explain the other side. Refute the opposition one point at a time.

- Provide your proof. After you address the other side, you’ll want to provide clear evidence that your side is the best side.

- Present your conclusion. In your conclusion, you should remind your readers of your main point or thesis and summarize the key points of your argument. If you are arguing for some kind of change, this is a good place to give your audience a call to action. Tell them what they could do to make a change.

For a visual representation of this type of argument, check out the Aristotelian infographic below:

Introduction to Aristotelian Argument

The Aristotelian or classical argument is a style of argument developed by the famous Greek philosopher and rhetorician, Aristotle. In this style of argument, the writer’s goal is to be convincing and to persuade your audience to your side of the issue through a series of strategies.

Start here!

Before you begin, review your assignment and ask yourself questions about what you might want to write about.

Use prewriting activities, such as brainstorming or listing, to help develop ideas for topics and angles.

Do your research! Find credible sources to help you build your argument.

But there’s more! There are some important concepts you need to learn about.

Modes of Persuasion

Ethos=credibility

Pathos=emotions

Logos=logic

Know Your Audience!

When writing a classical or Aristotelian argument, think about how you are going to be convincing to your audience!

Things to remember along the way…

Clear thesis

Support thesis

Opposing views

Cite sources

Sample Essay

For a sample essay written in the Aristotelian model, click here .

Aristotelian (Classical) Argument Model Copyright © 2020 by Liza Long; Amy Minervini; and Joel Gladd is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Forgot your Password?

First, please create an account

Classical argument model.

- Models of Argumentation

- Classical Argumentation

- Using the Classical Model

- Classical Argument Model: Example

1. Models of Argumentation

There are several different models for constructing arguments that are recognized in the field of composition. This tutorial focuses on one of them: the classical model.

hint There is no such thing as the "right" or "best" model of argumentation. Some models simply work better in certain situations than others, and some writers prefer some models to others for personal reasons. New writers should consider the qualities and priorities of particular models within the context of their writing needs.

The point of learning models of argumentation is to give beginning writers options to consider during the stages of the writing process, including brainstorming, pre-writing and outlining, and during the drafting and revision processes. Writers who are familiar with multiple argumentation models can select the one they believe is best-suited to construct an argument on a specific subject and purpose.

2. Classical Argumentation

The classical model of argumentation is one of the oldest systems of argumentation. It is primarily designed to persuade readers to take an action, or to share a writer's perspective.

did you know The classical argument model was designed by the ancient Greek rhetorician and philosopher, Aristotle.

The classical model was created when arguments were made in speeches. It emphasizes the use of the three rhetorical appeals that are known by their Greek names:

- Logos: appeals to logic or reasoning.

- Ethos: appeals to credibility.

- Pathos: appeals to emotion.

An argument built on the classical model consists of five components:

- Introduction. The introduction must be engaging and interesting.

- Background. This is the necessary background information regarding the thesis.

- Claims. These are arguments asserted with force and clarity. This section comprises most of the essay.

- Counterarguments. These address and refute opposing or alternative viewpoints, whether they exist, or are viewed by the writer as having the potential to exist.

- Conclusion. This final component must conclude the argument in a way that is satisfying, and that clearly identifies what is at stake in the broader context. Traditionally, the conclusion addressed a call to action to the audience, though this is no longer a requirement of the classical model.

3. Using the Classical Model

There are many reasons why modern writers choose the classical model to structure their work. One of the main reasons is that the classical model is familiar to those who learned (and used) it as students. The classical model is also a good choice for timed writing (e.g., as when answering essay questions on tests) because of its simplicity and compatibility with the five-paragraph essay model.

Writers often choose the classical model when their primary goal is persuasion, and because counterarguments can be effectively addressed using this model.

hint One reason not to choose the classical model is its simple structure. Although it confers advantages in some situations, writers who want to thoroughly develop a complex or detailed argument may be limited by this model. However, the classical model remains a good form of argumentation to understand and apply, when approriate.

4. Classical Argument Model: Example

Following is an outline of an essay that was constructed according to the classical model.

Topic: College and national service Working thesis: We should expand opportunities for national service that lead to funds for college tuition and related expenses. Introduction: A college graduate is likely to earn $570,000 more, over the course of his or her lifetime, than those without a college degree. A college degree is a requirement for most good-paying jobs. However, the cost of college has skyrocketed: this expense, combined with class and cultural differences, has made a college education unattainable for many. Military service is a way to pre-earn college funds, but many do not have the temperament or desire for it. Therefore, we must provide opportunities for national service in addition to those provided by the armed forces that lead to funds for college education. Background: a. Institution of the "GI Bill" and its goals b. National service models in other nations c. Rising costs of college and ballooning debt d. Growing problem of student debt among students who do not earn a degree (i.e., who do not finish college). This situation is more devastating than not attending college at all. Claims: a. Various national service opportunities must be available (military and non-military), and prospective students between the ages of 18-21 should be encouraged to embrace them. These opportunities should provide 2-4 years of college funding upon completion of service. b. National service opportunities will improve college access for working class people, and lower the college debt burden for middle class people. c. National service will directly benefit the country and also increase the sense of civic duty and social commitment in participants. d. National service opportunities will increase employability by providing "real world" experience, and time to mature, before enrollment. Counterarguments: a. Such a program would be too expensive — Costs would be defrayed by higher government income from increased tax revenue and greater spending by employed citizens. b. The real answer is to make college free — This is unlikely, due to political realities. However, a national service model might entice both liberals and conservatives. c. The real answer is to let the market decide: let people sink or swim on their own merits — It is widely acknowledged that the U.S. is not a true meritocracy because of social inequality. National service that leads to college education would help those who are smart and driven to succeed. Conclusion: An expanded national service model that pays participants in funds for college would benefit the country, and could be a model that other nations adopt. Everyone should consider the merits of this proposal and think of ways to implement it on a national level.

Begin by evaluating the topic: college and national service. The working thesis states that opportunities for national service that lead to funds for college education should be expanded. The draft outline has been divided into sections according to the classical model, beginning with an introduction that focuses on capturing readers' interest as well as introducing the subject.

According to the model, the next section (i.e., background) must provide all of the information that the audience will need to understand the argument. The essay will outline the institution of the "GI Bill" and its goals, then refer to national service models in other nations, the rising cost of college and growing student debt. Next, it will address the problem of students who go into debt but do not finish college: It will assert that this situation is more devastating than not attending college at all.

The background is followed by a section on claims. In it, the writer will argue about the national service opportunities that should be available to potential students, both military and non-military, including a claim that people between the ages of 18 and 21 should be encouraged to take advantage of these opportunities. The writer plans to argue that national service will increase college access for working class people and lower the college debt burden of many middle class people. The outline also posits that national service will benefit the country, not only in terms of what the service produces, but also in an increased sense of civic duty and social commitment among participants. Finally, the writer will argue that national service opportunities will improve employability by providing real-world experience and time to mature prior to enrolling in college.

The next section in the model is for counterarguments. The sample outline considers several counterarguments, including the assertion that a program like this would be too expensive. The outline's response to this argument is that costs will be offset by increased government income from greater tax revenue and more spending by employed citizens. The next counter argument addressed in the outline is that the "real" answer is to make college free. The essay will refute this by indicating that this is unlikely to happen due to political realities, but a national service model might gain the support of liberals and conservatives. The final counter argument included in the outline states that the best solution is to let the market decide: to let people sink or swim on their own merits. To refute this counterargument, the essay will argue that the U.S. is not a true meritocracy due to social inequality. National service that leads to college education will help those who are smart and driven to succeed.

The last section specified by the model is the conclusion. In this example, the conclusion will state that an expanded national service model that provides funds for college would benefit the country, and could serve as a model for other nations. Like many classically-modeled arguments, it ends with a call to action: everyone should consider the merits of this proposal and think about ways to implement it on a national level.

summary This tutorial examined one of the models of argumentation, the classical model, which is designed for persuading an audience to take an action, or to share a writer's perspective. It described the components of the model, and when (or where) it can be most useful. The outline of a sample argument structured according to this model was evaluated.

Source: Adapted from Sophia Instructor Gavin McCall

A methodology for structuring arguments, designed by Aristotle, and primarily designed to persuade the audience to take an action or to share the author's perspective.

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

© 2024 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC.

English Composition II - ENGL 1213

- Choosing An Issue

- Find eBooks

- Find Articles

- Search Tips

- Write It, Cite It

- Ask a Librarian

- The Research Proposal

- The Annotated Bibliography

Requirements

Writing prompt.

- Essay 2 - The Rogerian Argument

- Essay 3 - The Toulmin Essay Argument

The purpose of Essay 1 is to further expand on your argument abilities gained in Composition I. In Composition I, the final assignment is the Classical Argument. This is one of the most important structures in academic discourse. It cannot be mastered in one go. Reflect on your strengths and weaknesses with your first Classical Argument and write a new argument using the same structure from Composition I.

The essay should include the folllowing:

- 3 pages (double-spaced), not including the Works Cited page

- In-text citations in the body of the essay

- Works Cited page with your credible sources

- A minimum of three sources

To complete this assignment, you should:

- Reflect: Think back on what you did well on the first attempt of the Classical Argument in Composition I. What were some of your strong points? Why do you think so? Also, think about your weak points. Why did you not do so strongly in some areas? What can be done this time to make the essay better? You must submit a reflection technique as part of the final essay grade.

- Utilize invention techniques : Before writing the essay, begin identifying your issue through a series of invention techniques, including but not limited to the following: brainstorming, listing, clustering, questioning, and conducting preliminary research. You must submit invention techniques as part of the final essay grade.

- Plan and organize your essay : After the invention process, it is important to begin planning the organizational pattern for the essay. Planning includes identifying your thesis, establishing main ideas (or topic sentences) for each paragraph, supporting each paragraph with appropriate evidence, and creating ideas for the introductory and concluding paragraphs. You must submit evidence of a planning process as part of the final essay grade.

- Draft and revise your essay : Once you have completed the planning process, write a rough draft of your essay. Next, take steps to improve, polish, and revise your draft before turning it in for a final grade. The revision process includes developing ideas, ensuring the thesis statement connects to the main ideas of each paragraph, taking account of your evidence and supporting details, checking for proper use of MLA citation style, reviewing source integration, avoiding plagiarism, and proofreading for formatting and grammatical errors.

In Composition I, you wrote about a belief system and took a position about a part of the belief. If you did not do this in Composition I, think back on what you believe you did well the last time you wrote a Classical Argument.

In Composition II, think about the research problem you selected in the Research Proposal. Using the information discovered during the research proposal assignment, there needs to be an examination of a larger debate where you take a side in the argument, defend their stance with credible evidence, examine the counterpoints, and propose solutions to the problem.

This assignment helps you practice the following skills that are essential to your success in school and your professional life beyond school. In this assignment you will:

- Access and collect needed information from appropriate primary and secondary sources

- Synthesize information to develop informed views to produce and refute argumentation

- Compose a well-organized, classical argument to expand your knowledge of a topic

- << Previous: The Annotated Bibliography

- Next: Essay 2 - The Rogerian Argument >>

- Last Updated: Mar 1, 2024 4:41 PM

- URL: https://libguides.occc.edu/comp2

Table of Contents

Collaboration, information literacy, writing process, aristotelian argument.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

Learn how to employ the fundamental qualities of argument developed by Aristotle.

Aristotelian Argument is a deductive approach to argumentation that presents a thesis, an argument up front — somewhere in the introduction — and then endeavors to prove that point via deductive reasoning and exemplification .

Scholarly conversations regarding this style of argument can be traced to the 4th century BEC, including, especially Aristotle’s Rhetoric as well as the later works of Cicero and Quintilian.

Aristotelian argument is strategic choice for developing your arguments so long as

- your audience is open to argument based on logical reasoning and rhetorical reasoning .

- you are well versed on scholarly conversations about the topic .

Aristotelian Argument may also be referred to as Classical Argument or Traditional Argument

Related Concepts: Evidence ; Persuasion

Guide to Aristotelian Argument

Arguments come in all shapes and sizes. Hence, there’s no one way to compose an argument. Rather, you need to adjust how you shape your arguments based on your topic and rhetorical situation .

As always, you are wise to engage in rhetorical reasoning and rhetorical analysis to decide whether you should even respond to a call for an argument, much less invest the time in research your claims.

- Introduces the Topic

- Introduce Claims

- Appeal to Ethos & Persona to Establish an Appropriate Tone

- Appeal to Emotions

- Appeal to Logic

- Present Counterarguments

- Search for a Compromise and Call for a Higher Interest

- Speculate About Implications in Conclusions

1. Introduce the Topic

Before attempting to convince readers to agree with your position on a subject, you may need to educate them about the topic. In the introduction, explain the scope, complexity, and significance of the issue. You might want to mention the various approaches others have taken to solve the problem.

A discussion of background information and definition of terms can constitute a substantial part of your argument when you are writing for uninformed audiences, or it can constitute a minor part of your argument when you are writing for more informed audiences.

2. State Claims

Arguments are driven by claims. The claims can be about:

- Facts (Females are better mathematicians than males).

- Cause-and-Effect Relationships (Media violence creates a “culture of violence” in America).

- Solutions (Vegetarian diets are healthier and easier on the environment).

- Policies (Students who plagiarize should be expelled).

- Value (It’s unethical to hurt animals to conduct medical research).

As discussed below, claims are typically presented near the beginning of arguments, but they can also be implied or presented in the conclusions of the texts.

3. Appeal to Ethos & Persona to Establish an Appropriate Tone

The ethos the person making the argument has an effect on its success. If the writer, speaker, knowledge worker . . . has a reputation as a credible source, their argument appears more persuasive.

Additionally, the persona you project as a communicator influences whether readers, listeners, users . . . will read and consider of your argument. Your opening sentences generally establish the tone of your text and present to the reader a sense of your persona, both of which play a tremendous role in the overall persuasiveness of your argument. By evaluating how you define the problem, consider counterarguments, or marshal support for your claims, your readers will make inferences about your ethos and pathos.

Most academic readers are put off by zealous, emotional, or angry arguments. No matter how well you fine-tune the substance of your document, the tone that readers detect significantly influences how the message is perceived. If readers dislike the manner of your presentation, they may reject your facts, too. If you do not sound confident, your readers may doubt you. If your paper is loaded with spelling errors, you look foolish. No matter how solid your evidence is for a particular claim, your readers may not agree with you if you sound sarcastic, condescending, or intolerant.

Occasionally writers will hide behind a persona. Their reasons for hiding may be totally ethical.

4. Appeal to Emotions

Advertising seeks to invoke your emotions and capture your attention because advertisers know people make some decisions based on emotion rather than reason.

We all tend to perceive certain situations subjectively and passionately—particularly situations that involve us at a personal level. Even when we try to be objective, many of us still make decisions based on emotional impulses rather than sound reasoning. Those who recognize the power of emotional appeals sometimes twist them to sway others. Hitler is an obvious and extreme example. His dichotomizing—”You’re either for me or against me”—and bandwagon appeals—”Everyone knows the Jews are inferior to true Germans”—helped instigate one of the darkest chapters in human history.

Additional emotional appeals include:

- According to the EPA, global warming will raise sea levels).

- I should be allowed to take the test again because I had the flu the first time I took it).

- I wouldn’t vote for that man because he’s a womanizer).

Like arguments based solely on the persona of the author, arguments based solely on appeals to emotions usually lack the strength to be completely persuasive. Most modern, well-educated readers are quick to see through such manipulative attempts.

Emotional appeals can be used to persuade readers of the rightness of good causes or imperative action. For example, if you were writing an essay advocating a school-wide recycling program, you might paint an emotional, bleak picture of what our world will look like in 50 years if we don’t begin conserving now.

To achieve the non-threatening tone needed to diffuse emotional situations, avoid exaggerating your claims or using biased, emotional language. Also, avoid attacking your audience’s claims as exaggerated. Whenever you feel angry or defensive, take a deep breath and look for points in which you can agree with or understand your opponents. When you are really emotional about an issue, try to cool off enough to recognize where your language is loaded with explosive terms.

If the people for whom you are writing feel stress when you confront them with an emotionally charged issue and have already made up their minds firmly on the subject, you should try to interest such reluctant readers by suggesting that you have an innovative way of viewing the problem. Of course, this tactic is effective only when you can indeed follow through and be as original as possible in your treatment of the subject. Otherwise, your readers may reject your ideas because they recognize that you have misrepresented yourself.

5. Appeal to Logic

Critical readers expect you to develop your claims thoroughly. By examining the point you want to argue and the needs of your audience, you can determine whether it will be acceptable to rely only on anecdotal information and reasoning or whether you will also need to research facts and figures and include quotations from established sources. Personal observations have their place, say, in an argument about staying in athletic shape. But an anecdotal tone is unlikely to be persuasive when you address touchy social issues such as terrorism, gun control, pornography, or drugs.

Despite the forcefulness of your emotional appeals, you need to be rational if you hope to sway educated readers. Trained as critical readers, your teachers and college-educated peers expect you to provide evidence—that is, logical reasoning, personal observations, expert testimony, facts, and statistics. Like a judge who must decide a case based on the law rather than on intuition, your teachers want to see that you can analyze an issue as “objectively” as possible. As members of the academic community, they are usually more concerned with how you argue than what you argue for or against. Regardless of your position on an issue, they want to see that you can defend your position logically and with evidence.

6. Present Counter Arguments

At some point in your essay, you may need to present counterarguments to your claim(s). Essentially, whenever you think your readers are likely to disagree with you, you need to account for their concerns. Elaborating on counterarguments is particularly useful when you have an unusual claim or a skeptical audience. The strategy usually involves stating an opinion or argument that is contrary to your position, then proving to the best of your ability why your point of view still prevails.

When presenting and refuting counterarguments, remember that your readers do not expect your position to be valid 100 percent of the time. Few people think so simplistically. Despite the forced choices that clever rhetoricians present, few subjects that are worth arguing about can be reduced to yes, always, or no, never. When it is pertinent, therefore, you should concede any instances in which your opponents’ counterarguments have merit.

When considering likely counterarguments, you may want to elaborate on which of your opponent’s claims about the problem are correct. For example, if your roommate’s messiness is driving you crazy but you still want to live with him or her, stress that cleanliness is not the be-all-and-end-all of human life. Commend your roommate for helping you focus on your studies and express appreciation for all of the times that he or she has pitched in to clean up. And, of course, you would also want to admit to a few annoying habits of your own, such as taking thirty-minute showers or forgetting to pay the phone bill. Rather than issuing an ultimatum such as “Unless you start picking up after yourself and doing your fair share of the housework, I’m moving out,” you could say, “I realize that you view housekeeping as a less important activity than I do, but I need to let you know that I find your messiness to be highly stressful, and I’m wondering what kind of compromise we can make so we can continue living together.” Yes, this statement carries an implied threat, but note how this sentence is framed positively and minimalizes the emotional intensity inherent in the situation.

You will sabotage your hard-won persona as an informed and fair-minded thinker if you misrepresent your opponent’s counterarguments. For example, one rhetorical tactic that critical readers typically dislike is the straw man approach, in which a weak aspect of the opponent’s argument is equated with weakness of the argument as a whole. Unfortunately, American politicians tend to garner voter support by misrepresenting their opponent’s background and position on the issues. Before taking a straw man approach in an academic essay, you should remember that misrepresenting or satirizing opposing thoughts and feelings about your subject will probably alienate thoughtful readers.

7. Search for a Compromise and Call for a Higher Interest

Occasionally–particularly in emotionally stressful situations–authors extensively develop counterarguments. Some problems are so complex that there simply isn’t one solution to the problem. Under such circumstances, authors may seek a compromise under a call for a “higher interest.” For example, if you were writing an editorial in an Israeli newspaper that called for setting aside some of the Gaza territory for an independent Palestinian state, your introduction might sympathetically explore all of the Israeli blood that has been lost since the Gaza was seized in the Seven Day War. Then you could address the “eye-for-an-eye” mentality that has characterized this problem. Perhaps you could soften your readers’ thoughts about this problem by mentioning the number of Arabs who have died. Once you have developed your claim that some land should be set aside for the Palestinians, you might try to explore some of the “common ground” and call for Israelis and Arabs to seek out a higher goal expressed by both Jewish and Muslim peoples—that is, the desire for peace.

8. Speculate About Implications in Conclusions

Instead of merely repeating your original claim in the conclusion, you should end by trying to motivate your audience. Do not go out with a whimper and a boring restatement of your introduction. Instead, elaborate on the significant and broad implications of your argument. The wrap-up is an excellent place to utilize some emotional appeals.

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...

Information Literacy - Discerning Quality Information from Noise

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a...

Mindset refers to a person or community’s way of feeling, thinking, and acting about a topic. The mindsets you hold, consciously or subconsciously, shape how you feel, think, and act–and...

Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication

Learn about rhetoric and rhetorical practices (e.g., rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning, rhetorical situation, and rhetorical stance) so that you can strategically manage how you compose and subsequently produce a text...

Style, most simply, refers to how you say something as opposed to what you say. The style of your writing matters because audiences are unlikely to read your work or...

The Writing Process - Research on Composing

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about...

Writing Studies

Writing studies refers to an interdisciplinary community of scholars and researchers who study writing. Writing studies also refers to an academic, interdisciplinary discipline – a subject of study. Students in...

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority – How to Establish Credibility in Speech & Writing

Structure & Outlining

Classical essay structure.

The following videos provide an explanation of the classical model of structuring a persuasive argument. You can access the slides alone, without narration, here .

- Composition II. Authored by : Alexis McMillan-Clifton. Provided by : Tacoma Community College. Located at : http://www.tacomacc.edu . Project : Kaleidoscope Open Course Initiative. License : CC BY: Attribution

- 102 S11 Classical I. Authored by : Alexis McMillan-Clifton. Located at : https://youtu.be/kraJ2Juub5U . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- 102 S11 Classical II. Authored by : Alexis McMillan-Clifton. Located at : https://youtu.be/3m_EP-BPsBs . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

The Classical Argument

Adapted from Walter Beale, Real Writing , 2 nd edition, 1986

One of the oldest organizing devices in rhetoric is the classical argument , which incorporates the five parts of a discourse that ancient teachers of rhetoric believed were necessary for persuasion, especially when the audience included a mixture of reactions from favorable to hostile. They often prescribed this order to students, not because it was absolutely ideal, but because using the scheme encouraged the writer to take account of some of the most important elements of composing:

The classical argument isn�t a cookie-cutter template: simply filling in the parts does not by itself make you successful. But if you use the structure as a way to make sure you cover all the needs of all parts of your audience, you will find it a very useful heuristic for developing effective arguments.

The classical argument traditionally consists of five parts:

Let�s look at how these five sections translate into a written classical argument.

The Introduction

The introduction has four jobs to do:

- It must attract the interest of a specific audience and focus it on the subject of the argument.

- It must provide enough background information to make sure that the audience is aware of both the general problem as well as the specific issue or issues the writer is addressing (for instance, not just the problem of pollution but the specific problem of groundwater pollution in Columbia, SC).

- It must clearly signal the writer�s specific position on the issue and/or the direction of her/his argument. Usually a classical argument has a written thesis statement early in the paper�usually in the first paragraph or two.

- It must establish the writer�s role or any special relationship the writer may have to the subject or the audience (for instance, you�re committed to the Susan G. Komen Race for the Cure because your mother is a breast cancer survivor). It should also establish the image of the writer (the ethos ) that he/she wants to project in the argument: caring, aggressive, passionate, etc.

Some Questions to Ask as You Develop Your Introduction

1. What is the situation that this argument responds to?

2. What elements of background or context need to be presented for this audience? Is this new information or am I just reminding them of matters they already have some familiarity with?

3. What are the principal issues involved in this argument?

4. Where do I stand on this issue?

5. What is the best way to capture and focus the audience�s attention?

6. What tone should I establish?

7. What image of myself should I project?

The Confirmation

There�s a strong temptation in argument to say �Why should you think so? Because!� and leave it at that. But a rational audience has strong expectations of the kinds of proof you will and will not provide to help it accept your point of view. Most of the arguments used in the confirmation tend to be of the inartistic kind, but artistic proofs can also be used to support this section.

Some Questions to Ask as You Develop Your Confirmation

- What are the arguments that support my thesis that my audience is most likely to respond to?

- What arguments that support my thesis is my audience least likely to respond to?

- How can I demonstrate that these are valid arguments?

- What kind of inartistic proofs does my audience respect and respond well to?

- Where can I find the facts and testimony that will support my arguments?

- What kinds of artistic proofs will help reinforce my position?

The Concession/Refutation

The concession/refutation section involves a great deal of what you learned in writing Rogerian arguments . You want to concede any points that you would agree on or that will make your audience more willing to listen to you (as long as they don�t fatally weaken your own side). For instance, you might argue that we need stronger groundwater pollution laws, but concede that we shouldn�t hold cities and municipalities legally liable for cleaning up groundwater that was polluted before the law was passed, if you think that will help sell your case. Again, here is a place to use both pathos and ethos : by conceding those matters of feeling and values that you can agree on, while stressing the character issues, you can create the opportunity for listening and understanding.

But you will also have to refute (that is, counter or out-argue) the points your opposition will make. You can do this in four ways:

- Show by the use of facts, reasons, and testimony that the opposing point is totally wrong. You must show that the opposing argument is based on incorrect evidence, questionable assumptions, bad reasoning, prejudice, superstition, or ill will.

- Show that the opposition has some merit but is flawed in some way. For instance, the opposing viewpoint may be true only in some circumstances or within a limited sphere of application, or it may only apply to certain people, groups, or conditions. When you point out the exceptions to the opposition rule, you show that its position is not as valid as its proponents claim it is.

- Show that the opposition has merits but is outweighed by other considerations. You are claiming, in essence, that truth is relative: when a difficult choice has to be made, we must put first things first. For instance, you may say that it�s undesirable for young girls to have abortions, but when girls as young as ten become pregnant, they�re too young to take on the burdens of motherhood and must not be forced to carry the pregnancy to term. Or you may say that yes, it�s true that my proposal is expensive, but consider the costs if we do not undertake it, or how much the price will go up if we wait to undertake it, etc.

- Show that the reasoning used by the opposition is flawed: in other words, that it contains logical fallacies . For instance, the opposition may claim that anyone who does not support a retaliatory bombing of Afghanistan to punish Osama bin Laden and the regime that supports him is not a patriotic American; you can show that this is an example of the �either/or� fallacy by showing that there are other patriotic responses than nuking a Stone Age country further back into the Stone Age�for instance arresting bin Laden and the Taliban leaders and turning them over to the World Court, bringing them to trial in the US justice system, etc.

In general, strategies 2 and 3 are easier to pull off than strategy 1. Showing that a position is sometimes valid gives the opposition a face-saving �out� and preserves some sense of common ground .

Some Questions to Ask as You Develop Your Concession/Refutation

- What are the most important opposing arguments? What concessions can I make and still support my thesis adequately?

- How can I refute opposing arguments or minimize their significance?

- What are the possible objections to my own position?

- What are the possible ways someone can misunderstand my own position?

- How can I best deal with these objections and misunderstandings?

The Conclusion

Conclusions are hard and there�s a temptation to simply repeat your thesis and topic sentences and pray for a miracle. However, if you try to step back in your conclusion, you can often find a way to give a satisfying sense of closure. You might hark back to the background: why has this remained a problem and why is it so important to solve it, your way, now? Or you might hark back to the common ground you have with your audience: why does accepting your argument reinforce your shared beliefs and values? Too many times classical arguments don�t close�they just stop, as if the last page is missing. And this sense of incompleteness leaves readers dissatisfied and sometimes less likely to accept your argument. So spending a little extra time to round the conclusion out is almost always worthwhile in making the argument more successful.

Some Questions to Ask as You Develop Your Conclusion

- How can I best leave a strong impression of the rightness and importance of my view?

- How can I best summarize or exemplify the most important elements of my argument?

- What is the larger significance of the argument? What long-range implications will have the most resonance with my readers?

- How can I bring the argument �full circle� and leave my readers satisfied with the ending of my argument?

Read a sample student classical argument See more resources on classical argument

50 Argumentative Essay Topics

Illustration by Catherine Song. ThoughtCo.

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

An argumentative essay requires you to decide on a topic and take a position on it. You'll need to back up your viewpoint with well-researched facts and information as well. One of the hardest parts is deciding which topic to write about, but there are plenty of ideas available to get you started.

Choosing a Great Argumentative Essay Topic

Students often find that most of their work on these essays is done before they even start writing. This means that it's best if you have a general interest in your subject, otherwise you might get bored or frustrated while trying to gather information. (You don't need to know everything, though.) Part of what makes this experience rewarding is learning something new.

It's best if you have a general interest in your subject, but the argument you choose doesn't have to be one that you agree with.

The subject you choose may not necessarily be one that you are in full agreement with, either. You may even be asked to write a paper from the opposing point of view. Researching a different viewpoint helps students broaden their perspectives.

Ideas for Argument Essays

Sometimes, the best ideas are sparked by looking at many different options. Explore this list of possible topics and see if a few pique your interest. Write those down as you come across them, then think about each for a few minutes.

Which would you enjoy researching? Do you have a firm position on a particular subject? Is there a point you would like to make sure to get across? Did the topic give you something new to think about? Can you see why someone else may feel differently?

50 Possible Topics

A number of these topics are rather controversial—that's the point. In an argumentative essay, opinions matter and controversy is based on opinions, which are, hopefully, backed up by facts. If these topics are a little too controversial or you don't find the right one for you, try browsing through persuasive essay and speech topics as well.

- Is global climate change caused by humans?

- Is the death penalty effective?

- Is our election process fair?

- Is torture ever acceptable?

- Should men get paternity leave from work?

- Are school uniforms beneficial?

- Do we have a fair tax system?

- Do curfews keep teens out of trouble?

- Is cheating out of control?

- Are we too dependent on computers?

- Should animals be used for research?

- Should cigarette smoking be banned?

- Are cell phones dangerous?

- Are law enforcement cameras an invasion of privacy?

- Do we have a throwaway society?

- Is child behavior better or worse than it was years ago?

- Should companies market to children?

- Should the government have a say in our diets?

- Does access to condoms prevent teen pregnancy?

- Should members of Congress have term limits?

- Are actors and professional athletes paid too much?

- Are CEOs paid too much?

- Should athletes be held to high moral standards?

- Do violent video games cause behavior problems?

- Should creationism be taught in public schools?

- Are beauty pageants exploitative ?

- Should English be the official language of the United States?

- Should the racing industry be forced to use biofuels?

- Should the alcohol drinking age be increased or decreased?

- Should everyone be required to recycle?

- Is it okay for prisoners to vote (as they are in some states)?

- Is it good that same-sex couples are able to marry?

- Are there benefits to attending a single-sex school ?

- Does boredom lead to trouble?

- Should schools be in session year-round ?

- Does religion cause war?

- Should the government provide health care?

- Should abortion be illegal?

- Are girls too mean to each other?

- Is homework harmful or helpful?

- Is the cost of college too high?

- Is college admission too competitive?

- Should euthanasia be illegal?

- Should the federal government legalize marijuana use nationally ?

- Should rich people be required to pay more taxes?

- Should schools require foreign language or physical education?

- Is affirmative action fair?

- Is public prayer okay in schools?

- Are schools and teachers responsible for low test scores?

- Is greater gun control a good idea?

- Preparing an Argument Essay: Exploring Both Sides of an Issue

- Controversial Speech Topics

- Tips on How to Write an Argumentative Essay

- Bad Essay Topics for College Admissions

- 25 Essay Topics for American Government Classes

- Topic In Composition and Speech