Introduction to College Writing

Essays as conversation.

Think of an essay as participating in a conversation, in which you offer your ideas and provide details to explain those ideas to others. Writers do not make their claims in an enormous blank room where no one else is and nothing else has ever happened. Writers make their claims in the real world where people with other opinions, values, beliefs, and experiences live. To make a claim is to enter into a conversation with these people. The rhetorician Kenneth Burke once famously described this as a parlor or a party to which you have come late to find out that people are already in heated discussions about a topic. Everyone has been in these kinds of arguments.

For example, you arrive somewhere to meet two friends and discover that they are discussing where to go to dinner or what movie to see. Each friend presents his or her argument, setting out evidence for why this restaurant or movie is a good choice, and each friend pokes holes in the other person’s argument, pointing out why you would not enjoy that restaurant or movie. You are expected to take a role in this discussion. Maybe you take a stand with one friend over the other or maybe you try to reach a compromise and propose a third restaurant or movie that everyone could accept. This can lead to even further discussion.

This discussion between three friends is somewhat like Burke’s idea of the parlor but there are differences. Eventually the conversation between the three friends will reach an end: they will go to dinner or a movie, perhaps, or they will all go home. Everyone entered into the conversation, made his or her claims, responded to other people, and went on with his or her life. their lives. Burke, however, was talking about the conversations and arguments that take place in the larger culture and the world as a whole. Those are the larger conversations you’ll participate in as you deal with issues in psychology, business management, literature, history…whatever your specific academic focus is in whatever college course you are taking at the moment. Essay writing is one way of participating in that conversation.

Remember that college essay assignments often expect you to delve deeply into an issue, analyzing its various sides in order to come to your own conclusions, based on your observations, insights, and appropriate research. As you develop your own conclusions, you’ll have interesting ideas to offer in conversation.

Although the following video references graduate-level students, the same concepts hold true for undergraduate college writing, in which you’ll start learning how to join a conversation.

- Essays as Conversation. Revision and adaptation of the page Writing Commons: Michael Charlton's Understanding How Conversations Change Over Time at https://learn.saylor.org/mod/page/view.php?id=6695. Authored by : Susan Oaks. Provided by : Empire State College, SUNY OER Services. Project : College Writing. License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- Writing Commons: Michael Charlton's Understanding How Conversations Change Over Time. Authored by : Michael Charlton. Provided by : Saylor Academy. Located at : https://learn.saylor.org/mod/page/view.php?id=6695 . Project : ENGL001: English Composition I. License : Other . License Terms : Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license

- image of three friends in conversation. Authored by : rawpixel. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/en/adult-group-meeting-man-table-3365364/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- video An introduction to academic writing and research. Provided by : University of Roehampton. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kItASt4DjXA . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

Italy, 1952. Photo ©Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum

To converse well

A good conversation bridges the distances between people and imbues life with pleasure and a sense of discovery.

by Paula Marantz Cohen + BIO

Good conversation mixes opinions, feelings, facts and ideas in an improvisational exchange with one or more individuals in an atmosphere of goodwill. It inspires mutual insight, respect and, most of all, joy. It is a way of relaxing the mind, opening the heart and connecting, authentically, with others. To converse well is surprising, humanising and fun.

Above is my definition of an activity central to my wellbeing. I trace my penchant for good conversation to my family of origin. My parents were loud and opinionated people who interrupted and quarrelled boisterously with each other. I realise that such an environment could give rise to taciturn children who seek quiet above all else. But, for me, this atmosphere was stimulating and joyful. It made my childhood home a place I loved to be.

The bright, ongoing talk that pervaded my growing up was overseen by my mother, a woman of great charm and energy. She was the maestro of the dinner table, unfailingly entertaining and fun. We loved to listen to her tell stories about what happened to her at work. She was a high-school French teacher, a position that afforded a wealth of anecdotes about her students’ misbehaviour, eccentric wardrobe choices, and mistakes in the conjugation of verbs. There were also the intrigues among her colleagues – how I loved being privy to my teachers’ peccadillos and romantic misadventures, an experience that sowed a lifelong scepticism of authority. My mother had the gift of making even the smallest detail of her day vivid and amusing.

My father, by contrast, was a very different kind of talker. A scientist by training and vocation, he had a logical, detached sort of mind, and he liked to discuss ideas. He had theories about things: why people believed in God, the role of advertising in modern life, why women liked jewellery, and so on. I recall how he would clear his throat as a prelude to launching into a new idea: ‘I’ve been thinking about why we eat foods like oysters and lobster, which aren’t very appealing. There must be an evolutionary aspect to why we have learned to like these things.’ Being included in the development of an idea with my father was a deeply bonding experience. The idea of ideas became enormously appealing as a result. And though my father was not an emotional person – and, indeed, because he was not – I associated ideas with our relationship, and they became imbued with feeling.

Perhaps my family was exceptional in its love of conversation, but all families are, to some extent, learning spaces for how to talk. This is the paradox of growing up. Language is learned in the family; it solidifies our place within it, but it also allows us to move beyond it, giving us the tools to widen our experience with people very different from ourselves.

My family inculcated in me a life-long love of conversation – of sprightly, sometimes contentious, but always interesting talk that allowed me to lose myself for the space of that engagement. My pleasure in conversation has led me to think about the activity at length, from both a psychological and philosophical perspective: what makes a good conversation? What role has conversation served in history? What does talk do for us, and how can it ameliorate aspects of our current, divided society, if pursued with vigour and goodwill?

S igmund Freud began his groundbreaking work as the father of psychoanalysis by postulating that his patients’ symptoms were physical responses to traumatic events or taboo desires dating from childhood. He found that if these people could be encouraged to talk without inhibition – to free-associate on what they were feeling – they would eventually find the source of their problems and the cure for what ailed them. With this in view, he made talk central to his therapeutic method – hence, the ‘talking cure’.

Although many of Freud’s theories have since been refuted, the talking cure has endured. Clinical psychologists still recommend talk therapy as a treatment for both generalised anxiety as well as more severe mental health issues. And though Freud’s talking cure is not, by any stretch, a real conversation – the patient talks, the analyst listens and strategically intervenes – the phrase ‘talking cure’ strikes me as a useful one in referring to the nature and use of conversation in our lives.

The need for conversation is one that many people have not fully acknowledged, perhaps because they have not had occasion to do enough of it or to do it well. I am not suggesting that, in conversing, we serve as each other’s therapists, but I do believe that good talk, when carried on with the right degree of openness, can not only be a great pleasure but also do us a great deal of good, both individually and collectively as members of society.

For me, one particularly useful concept derived from Freud’s talking cure is the idea of transference . In the course of therapy, Freud found that some patients felt that they had fallen in love with their therapists. Since he believed that all love relationships recapitulate what occurs within one’s family of origin, he saw these patients’ infatuation as a repetition of earlier, intense feelings for a parent that could now be analysed and controlled – directed toward more productive and transparent ends.

A relationship can be over once consummated in sex. But friendships are never over after a good conversation

I think this idea is relevant to our understanding of conversation as an important activity in connecting with others. Putting aside the familial baggage that Freud saw as accompanying transference, a deep sense of affection seems to be, always, part of good conversation. Surely readers can identify with that welling up of positive feeling – that almost-falling-in-love with someone that we engage with in an authentic way. I have felt this not only for friends and even strangers with whom I’ve had probing conversations but also for whole classes of students where it can seem that the group has merged into one deeply lovable and loving body.

If love can be understood as important in conversation, so can desire, another element central to Freud’s thought. Sexual desire has its consummation in the sex act (a form of closure that accounts for why a poet like John Donne, among others, used ‘death’ to refer to sexual climax). Conversation, by contrast, does not consummate; it merely stops by arbitrary necessity. One may have to get across town for a meeting, pick up a child from school, or generally get on with the business of life. Such endings are in medias res , so to speak, or mid-narrative. I find it interesting that a relationship can sometimes be over once the partners have consummated it in sex. But friendships are never over after a good conversation; they are sustained and bolstered by it.

The search for satisfaction by our desiring self seems to me at the heart of good conversation. We seek to fill the lack in ourselves by engaging with someone who is Other – who comes from another position, another background, another set of experiences. Everyone, when taken in a certain light, is an Other by virtue, if nothing else, of having different DNA. To recognise this difference and welcome it is the premise upon which good conversation is built.

Conversation also helps us deal with the human fear of the unexpected and the changeable. Talk with others allows us to practise uncertainty and open-endedness in a safe environment. It offers exercise in extemporaneity and experiment; it de converts us from rigid and established forms of belief. There is no better antidote for certainty than ongoing conversation with a friend who disagrees .

G ood conversation is an art that can be perfected, and the best way to do this is to converse regularly with a variety of people. As the fat man says to Sam Spade in Dashiell Hammett’s novel The Maltese Falcon (1930): ‘Talking’s something you can’t do judiciously unless you keep in practice.’

The next best thing to practising conversation is reading those authors whose writing seems to channel the spirit of good conversation or give insight into its mechanics.

‘How can life be worth living … which lacks that repose which is to be found in the mutual good will of a friend? What can be more delightful than to have someone to whom you can say everything with the same absolute confidence as yourself’? wrote the lawyer and orator Marcus Tullius Cicero, who lived in ancient Rome in the 1st century BCE.

Expanding on the subject hundreds of years later, in the 16th century, was Michel de Montaigne , whose pioneering work in the personal essay form is, in its intimate and meandering style, a tribute to his love of conversation . ‘[I]f I were now compelled to choose,’ he writes in the essay ‘On the Art of Conversation’, which addresses the subject directly, ‘I should sooner, I think, consent to lose my sight, than my hearing and speech’. One feels the pathos of this statement, given that Montaigne lost his most cherished friend, Étienne de la Boétie, at an early age and never ceased to mourn that loss. Indeed, some feel that the loss of La Boétie, by depriving Montaigne of his companion in conversation, accounts for the Essays , written to fill that void.

The 18th century was a great age of conversation; Samuel Johnson, Jonathan Swift, Oliver Goldsmith, David Hume , Joseph Addison and Henry Fielding are among the venerable authors of the period to provide commentary on what they considered to be important for good talk. The Literary Club in London, frequented by many of these luminaries, is said to have been organised in 1764 to help Johnson from succumbing to depression – through conversation, among other things.

Conversation was one of the activities that an aspiring gentleman was expected to learn

The book The Words That Made Us (2021) by Akhil Reed Amar, on the founders of the American Republic, makes the point that the American Revolution was successful in mobilising disparate people to its cause as a result of long and probing conversations among constituents across the colonies. The British were fated to lose the war, Amar argues, because George III refused to listen, let alone converse with his American subjects.

In the 19th century, especially in the United States where shaping the self alongside shaping the country became something of a national obsession, conversation was one of the activities that an aspiring gentleman was expected to learn. We see publication of numerous etiquette books during this period, with titles like Manners for Men (1897); The Gentleman’s Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness (1860); and Hints on Etiquette and the Usages of Society: With a Glance at Bad Habits (1834) – all of which give guidance on conversation, though mostly of a utilitarian kind.

In the 20th century, the most notable figure in conversational self-help was Dale Carnegie, who created an entire industry out of teaching aspiring social and business climbers based on his most famous book, How to Win Friends and Influence People (1936). Carnegie began writing and giving courses in the 1910s, and his business survived him to grow into an empire (‘over 200 offices in 86 countries’, according to Forbes magazine in 2020) with supporting textbooks, online resources, newsletters and blogs that boast the tag line: ‘Training options that transform your impact.’ The message dovetails with the US myth of upward mobility and getting ahead. Carnegie’s self-improvement programmes have an offshoot in the self-realisation movements of the past few decades. A deluge of books in recent years link conversational skills to creative and relationship goals.

Having surveyed the abundant literature on conversation over the past two centuries, I find myself particularly charmed by a short but entertaining work, The Art of Conversation (1936) by Milton Wright. The book is full of citations from philosophy and literature, with thumbnail sketches of the ancient symposia and the ‘talkers of Old England’ while also exhaustively outlining conversational scenarios. In one case, the author describes a wife explaining to her husband how he should converse over dinner with his boss about his love of fishing and pipe smoking (Wright gives a verbatim account of the wife practising the conversation in advance of the dinner). In a chapter on ‘developing repartee’, Wright gives minute instruction on how to come up with a clever thought and insert it into conversation, advising:

It must be prompt. It must seem impromptu. It must be based upon the same premise that called it forth. It must outshine the original remark.

The author advises practising imaginary scenarios so as not to suffer l’esprit d’escalier (carefully defined for the reader: ‘you think of the scintillating remarks you could have made back there if only you had thought of them’). The book has sections on using flattery, seeking an opinion, and how to ‘let him parade his talents’.

The book’s erudition combined with its unadorned acknowledgment of human vanity is charming. It is perhaps no coincidence that Wright reminds me of Baldassare Castiglione and Niccolò Machiavelli in his tone; they too were writing at a high point of their civilisation, were both astute about human nature but optimistic about how the individual could rise through deliberate study and strategy. And yet, even as Wright explains the levers by which one can manipulate others to become a ‘successful’ conversationalist, he ends on a surprisingly moving note that undercuts his own lessons: ‘If … you can forget yourself, then you have learned the innermost secret of the art of good conversation. All the rest is a matter of technique.’

I love this book for its unabashed willingness to put forward this contradiction. One can make one’s conversation better by following certain instructions about listening well and employing choice opening gambits, transitions and techniques for putting one’s partner at ease; one may even practise ‘repartee’. But the secret to conversation, that of forgetting oneself, cannot be taught. It is akin to the double bind that psychologists refer to when someone tells us to ‘be spontaneous’. The admonition goes against the grain of what is involved: a state of being that happens by being swept up in the ‘flow’ of the moment.

I deally, one would want to converse with someone who is open and trusting, curious and good with words. But this is not always the case, and it often takes ingenuity and persistence to jump-start a good conversation . It is also a mistake to write off others simply because they don’t share your politics, religion or superficial values. While it is true that partisanship has become more pronounced in recent years, I don’t think this is irreparable.

Probing and spirited engagement can break apart ossified patterns of thought and bring to bear a more generous and flexible view of things. I have experienced the exhilaration of having an insight in the course of a conversation that didn’t fit with my pre-existing ideas, and of connecting with someone I might otherwise have written off. Most of us fear talking about important subjects with people we know disagree with us, much like we fear talking to people about the untimely death of a loved one. And yet these conversations are often, secretly, what both parties crave.

We discover new elements in our nature as we converse

Finally, there is the creative pleasure of conversation. If writing and speechifying can be equated with sculpture (where one models something through words in solitary space), conversation is more like those team sports where the game proceeds within certain parameters but is unpredictable and reliant on one’s ability to coordinate with another person or persons. Words in conversation can be arranged in infinite ways, but they wait on the response of a partner or partners, making this an improvisational experience partially defined by others and requiring extreme attentiveness to what they say. Also, like sport, conversation requires some degree of practice to do well. The more one converses – and with a variety of people – the better one gets at it and the more pleasure it is likely to bring.

Since conversation is, by definition, improvisational, it is always bringing to the fore new or unforeseen aspects of oneself to fit or counter or complement what the other is saying. In this way, we discover new elements in our nature as we converse. Over time, we incorporate aspects of others into ourselves as well.

One could say that in the flow of conversation the distance between self and Other is temporarily bridged – much as happens in a love relationship. It is sometimes hard to recall who said what when a conversation truly works – even when people are very different and stand ostensibly on different sides of issues.

Conversation is both a function of and a metaphor for our life in the world, always seeking to fulfil a need that is never fulfilled but whose quest gives piquancy and satisfaction, albeit temporarily and incompletely, to our encounters. In good conversation, there is always something left out, unplumbed and unresolved, which is why we seek more of it.

Adapted, in part, from Talking Cure: An Essay on the Civilizing Power of Conversation by Paula Marantz Cohen, published by Princeton University Press, 2023.

Consciousness and altered states

A reader’s guide to microdosing

How to use small doses of psychedelics to lift your mood, enhance your focus, and fire your creativity

Tunde Aideyan

The scourge of lookism

It is time to take seriously the painful consequences of appearance discrimination in the workplace

Andrew Mason

Economic history

The southern gap

In the American South, an oligarchy of planters enriched itself through slavery. Pervasive underdevelopment is their legacy

Keri Leigh Merritt

Thinkers and theories

Our tools shape our selves

For Bernard Stiegler, a visionary philosopher of our digital age, technics is the defining feature of human experience

Bryan Norton

Family life

A patchwork family

After my marriage failed, I strove to create a new family – one made beautiful by the loving way it’s stitched together

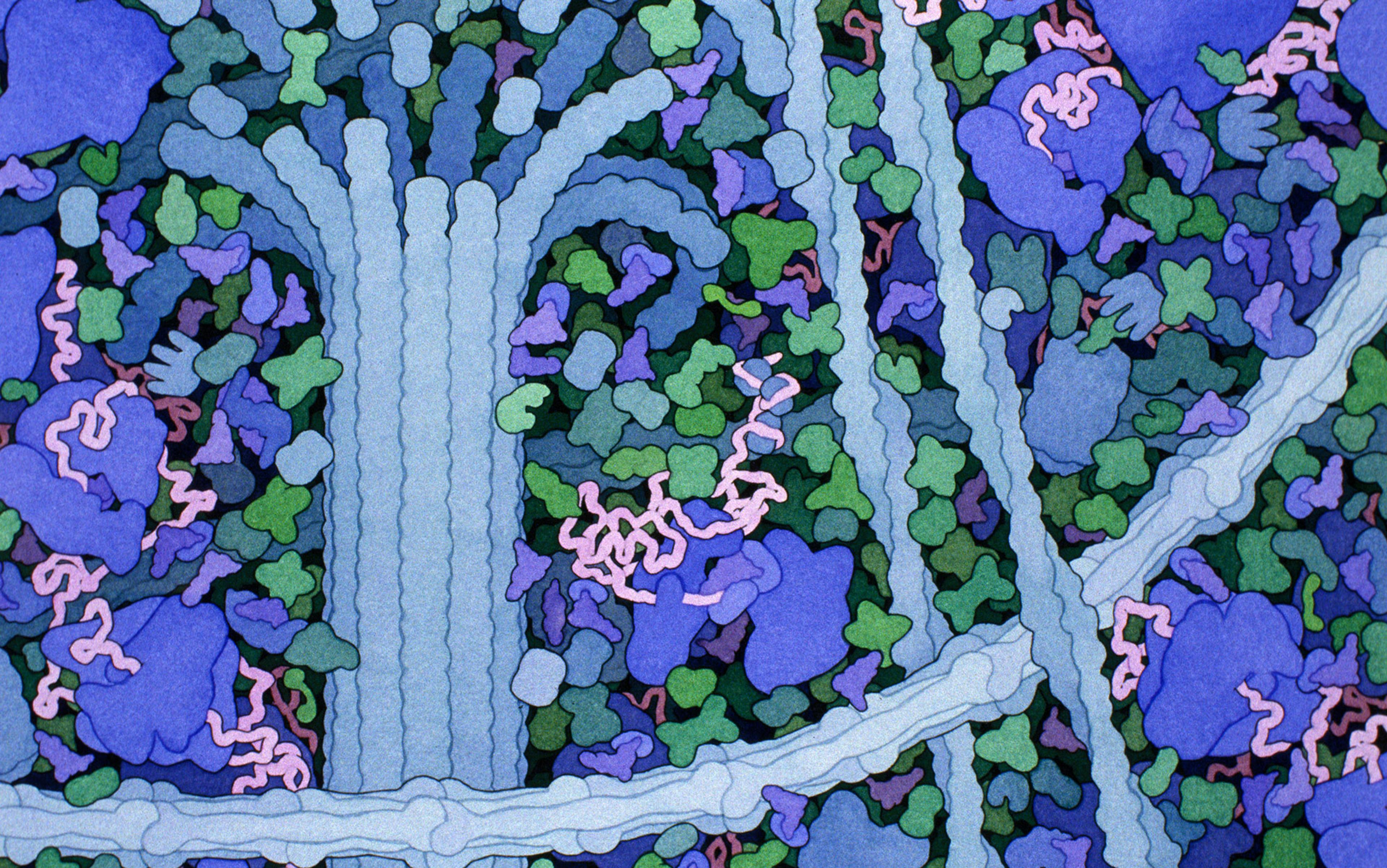

The cell is not a factory

Scientific narratives project social hierarchies onto nature. That’s why we need better metaphors to describe cellular life

Charudatta Navare

Don't have an Account? Register Now!

Forgot Password

Free online, english teaching and learning materials.

With over 2,500 conversations with audio and 3,000 short stories and essays with exercises, you are guaranteed to find something that's right for you.

For Beginners

Speak Kindergarten English

Speaking Is Easy

Easy Conversations

01 Start Reading for Children (I)

02 Start Reading for Children (II)

03 Start Reading for Children (III)

04 Super Easy Reading

05 Easy Reading

06 English Level 1

07 English Level 2

08 English Level 3

09 English Level 4

10 English Level 5

11 English Level 6

New Graded Reading 1

New Graded Reading 2

New Graded Reading 3

New Graded Reading 4

Grammar & Writing

12 Grammar Notes

13 Easy Grammar Exercises

14 Scrambled-Sentence Exercises (I)

15 Scrambled-Sentence Exercises (II)

For Intermediate Learners

Speak english fast, english conversations.

01 365 Essays for English Learners

02 100 American People

03 100 Essays: America Is Great!

04 American Culture and Customs

05 English for New USA Immigrants

06 ESL Mini-Novels

07 A Young Couple's Life in America

08 Sentence Structure Writing Practice

09 Advanced Grammar Exercises

10 Vocabulary Lists

ESL: English as a Second Language

The TESOL Ron Chang Lee Award for Excellence in Classroom Technology

CATESOL Ron Lee Technology Award

--------------------------------------------- Testimonial

- Food & Dining

- Coronavirus

- Real Estate

- Seattle History

- PNW Politics

How to Write an Essay in Conversational Style

- College & Higher Education

Related Articles

Why do poets use similes and metaphor, how to write topic sentences and thesis statements, after dinner speech topics for a college class.

- How to Draw Conclusions in Reading

- The Primary Purpose of a Reflective Essay Is to What?

Your high school teacher probably taught you a lot of rules about essay writing. There’s a reason, however, that the essays you wrote in high school probably aren’t very interesting, and it’s not only because they’re mostly about Shakespeare. It’s because they’re written in a formal style. To inject some interest into your essays by writing them in a conversational style -- for the right audience, at the right time -- you may end up breaking a few of the rules your English teacher taught you. Just be sure to match the right tone to the assignment.

Address the Reader

Talk to the reader as if you’re actually talking to the reader. Speak for yourself as the narrator. Instead of writing, “One might argue,” say “I argue.” Instead of writing, “It appears to be the case that the globe is warming,” say, “It looks like the earth’s getting hotter.” This will help bring your reader into the essay with you, and it will give her the sense that she knows you.

Use Contractions

There’s nothing wrong with contractions. They help us take linguistic shortcuts by combining words, which is why we use them all them all the time in daily life. So it’s important to use them in a conversational essay. You don’t want to sound like Data the robot from "Star Trek" -- you want to sound like a real human being. Real human beings say “don’t,” “haven’t,” “let’s” and “I’m,” so use those words when you’re trying to maintain a conversational tone.

Use Interesting Language

Dry language sounds academic to readers, and that can be off-putting. They’ll probably be tempted to flip the page when they read, “The earth’s temperature has risen rather dramatically over the duration of nine years.” On the other hand, they’ll want to hear more of what you have to say when you make a statement like, “The past decade’s been a scorcher.” To keep a reader interested, use language that evokes emotions from your reader.

Use Anecdotes

A writer can use many tools to convince a reader of his position. Quantitative data is an important tool. But stories are important, too, and often they’re more effective. Numbers can never paint a picture as clearly as a well-placed personal anecdote can, and by sharing stories with your reader, you can be both persuasive and interesting.

- Diane Burns: MBA Admissions: Anecdotal Essays

Living in Canada, Andrew Aarons has been writing professionally since 2003. He holds a Bachelor of Arts in English literature from the University of Ottawa, where he served as a writer and editor for the university newspaper. Aarons is also a certified computer-support technician.

How to Write Objectives in Papers

The meaning of the metaphor "you are the sun in my sky", instructions to write a narrative essay, attention grabbers to use when writing an essay, how to write an essay that stands out, how to write a shrinklet poem, what is the mood of "the highwayman", how to teach kids to write with all five senses in descriptive writing, what is the point of view in the short story "if i forget thee, o earth", most popular.

- 1 How to Write Objectives in Papers

- 2 The Meaning of the Metaphor "You Are the Sun in My Sky"

- 3 Instructions to Write a Narrative Essay

- 4 Attention Grabbers to Use When Writing an Essay

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Example of a great essay | Explanations, tips & tricks

Example of a Great Essay | Explanations, Tips & Tricks

Published on February 9, 2015 by Shane Bryson . Revised on July 23, 2023 by Shona McCombes.

This example guides you through the structure of an essay. It shows how to build an effective introduction , focused paragraphs , clear transitions between ideas, and a strong conclusion .

Each paragraph addresses a single central point, introduced by a topic sentence , and each point is directly related to the thesis statement .

As you read, hover over the highlighted parts to learn what they do and why they work.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about writing an essay, an appeal to the senses: the development of the braille system in nineteenth-century france.

The invention of Braille was a major turning point in the history of disability. The writing system of raised dots used by visually impaired people was developed by Louis Braille in nineteenth-century France. In a society that did not value disabled people in general, blindness was particularly stigmatized, and lack of access to reading and writing was a significant barrier to social participation. The idea of tactile reading was not entirely new, but existing methods based on sighted systems were difficult to learn and use. As the first writing system designed for blind people’s needs, Braille was a groundbreaking new accessibility tool. It not only provided practical benefits, but also helped change the cultural status of blindness. This essay begins by discussing the situation of blind people in nineteenth-century Europe. It then describes the invention of Braille and the gradual process of its acceptance within blind education. Subsequently, it explores the wide-ranging effects of this invention on blind people’s social and cultural lives.

Lack of access to reading and writing put blind people at a serious disadvantage in nineteenth-century society. Text was one of the primary methods through which people engaged with culture, communicated with others, and accessed information; without a well-developed reading system that did not rely on sight, blind people were excluded from social participation (Weygand, 2009). While disabled people in general suffered from discrimination, blindness was widely viewed as the worst disability, and it was commonly believed that blind people were incapable of pursuing a profession or improving themselves through culture (Weygand, 2009). This demonstrates the importance of reading and writing to social status at the time: without access to text, it was considered impossible to fully participate in society. Blind people were excluded from the sighted world, but also entirely dependent on sighted people for information and education.

In France, debates about how to deal with disability led to the adoption of different strategies over time. While people with temporary difficulties were able to access public welfare, the most common response to people with long-term disabilities, such as hearing or vision loss, was to group them together in institutions (Tombs, 1996). At first, a joint institute for the blind and deaf was created, and although the partnership was motivated more by financial considerations than by the well-being of the residents, the institute aimed to help people develop skills valuable to society (Weygand, 2009). Eventually blind institutions were separated from deaf institutions, and the focus shifted towards education of the blind, as was the case for the Royal Institute for Blind Youth, which Louis Braille attended (Jimenez et al, 2009). The growing acknowledgement of the uniqueness of different disabilities led to more targeted education strategies, fostering an environment in which the benefits of a specifically blind education could be more widely recognized.

Several different systems of tactile reading can be seen as forerunners to the method Louis Braille developed, but these systems were all developed based on the sighted system. The Royal Institute for Blind Youth in Paris taught the students to read embossed roman letters, a method created by the school’s founder, Valentin Hauy (Jimenez et al., 2009). Reading this way proved to be a rather arduous task, as the letters were difficult to distinguish by touch. The embossed letter method was based on the reading system of sighted people, with minimal adaptation for those with vision loss. As a result, this method did not gain significant success among blind students.

Louis Braille was bound to be influenced by his school’s founder, but the most influential pre-Braille tactile reading system was Charles Barbier’s night writing. A soldier in Napoleon’s army, Barbier developed a system in 1819 that used 12 dots with a five line musical staff (Kersten, 1997). His intention was to develop a system that would allow the military to communicate at night without the need for light (Herron, 2009). The code developed by Barbier was phonetic (Jimenez et al., 2009); in other words, the code was designed for sighted people and was based on the sounds of words, not on an actual alphabet. Barbier discovered that variants of raised dots within a square were the easiest method of reading by touch (Jimenez et al., 2009). This system proved effective for the transmission of short messages between military personnel, but the symbols were too large for the fingertip, greatly reducing the speed at which a message could be read (Herron, 2009). For this reason, it was unsuitable for daily use and was not widely adopted in the blind community.

Nevertheless, Barbier’s military dot system was more efficient than Hauy’s embossed letters, and it provided the framework within which Louis Braille developed his method. Barbier’s system, with its dashes and dots, could form over 4000 combinations (Jimenez et al., 2009). Compared to the 26 letters of the Latin alphabet, this was an absurdly high number. Braille kept the raised dot form, but developed a more manageable system that would reflect the sighted alphabet. He replaced Barbier’s dashes and dots with just six dots in a rectangular configuration (Jimenez et al., 2009). The result was that the blind population in France had a tactile reading system using dots (like Barbier’s) that was based on the structure of the sighted alphabet (like Hauy’s); crucially, this system was the first developed specifically for the purposes of the blind.

While the Braille system gained immediate popularity with the blind students at the Institute in Paris, it had to gain acceptance among the sighted before its adoption throughout France. This support was necessary because sighted teachers and leaders had ultimate control over the propagation of Braille resources. Many of the teachers at the Royal Institute for Blind Youth resisted learning Braille’s system because they found the tactile method of reading difficult to learn (Bullock & Galst, 2009). This resistance was symptomatic of the prevalent attitude that the blind population had to adapt to the sighted world rather than develop their own tools and methods. Over time, however, with the increasing impetus to make social contribution possible for all, teachers began to appreciate the usefulness of Braille’s system (Bullock & Galst, 2009), realizing that access to reading could help improve the productivity and integration of people with vision loss. It took approximately 30 years, but the French government eventually approved the Braille system, and it was established throughout the country (Bullock & Galst, 2009).

Although Blind people remained marginalized throughout the nineteenth century, the Braille system granted them growing opportunities for social participation. Most obviously, Braille allowed people with vision loss to read the same alphabet used by sighted people (Bullock & Galst, 2009), allowing them to participate in certain cultural experiences previously unavailable to them. Written works, such as books and poetry, had previously been inaccessible to the blind population without the aid of a reader, limiting their autonomy. As books began to be distributed in Braille, this barrier was reduced, enabling people with vision loss to access information autonomously. The closing of the gap between the abilities of blind and the sighted contributed to a gradual shift in blind people’s status, lessening the cultural perception of the blind as essentially different and facilitating greater social integration.

The Braille system also had important cultural effects beyond the sphere of written culture. Its invention later led to the development of a music notation system for the blind, although Louis Braille did not develop this system himself (Jimenez, et al., 2009). This development helped remove a cultural obstacle that had been introduced by the popularization of written musical notation in the early 1500s. While music had previously been an arena in which the blind could participate on equal footing, the transition from memory-based performance to notation-based performance meant that blind musicians were no longer able to compete with sighted musicians (Kersten, 1997). As a result, a tactile musical notation system became necessary for professional equality between blind and sighted musicians (Kersten, 1997).

Braille paved the way for dramatic cultural changes in the way blind people were treated and the opportunities available to them. Louis Braille’s innovation was to reimagine existing reading systems from a blind perspective, and the success of this invention required sighted teachers to adapt to their students’ reality instead of the other way around. In this sense, Braille helped drive broader social changes in the status of blindness. New accessibility tools provide practical advantages to those who need them, but they can also change the perspectives and attitudes of those who do not.

Bullock, J. D., & Galst, J. M. (2009). The Story of Louis Braille. Archives of Ophthalmology , 127(11), 1532. https://doi.org/10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.286.

Herron, M. (2009, May 6). Blind visionary. Retrieved from https://eandt.theiet.org/content/articles/2009/05/blind-visionary/.

Jiménez, J., Olea, J., Torres, J., Alonso, I., Harder, D., & Fischer, K. (2009). Biography of Louis Braille and Invention of the Braille Alphabet. Survey of Ophthalmology , 54(1), 142–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.10.006.

Kersten, F.G. (1997). The history and development of Braille music methodology. The Bulletin of Historical Research in Music Education , 18(2). Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40214926.

Mellor, C.M. (2006). Louis Braille: A touch of genius . Boston: National Braille Press.

Tombs, R. (1996). France: 1814-1914 . London: Pearson Education Ltd.

Weygand, Z. (2009). The blind in French society from the Middle Ages to the century of Louis Braille . Stanford: Stanford University Press.

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

An essay is a focused piece of writing that explains, argues, describes, or narrates.

In high school, you may have to write many different types of essays to develop your writing skills.

Academic essays at college level are usually argumentative : you develop a clear thesis about your topic and make a case for your position using evidence, analysis and interpretation.

The structure of an essay is divided into an introduction that presents your topic and thesis statement , a body containing your in-depth analysis and arguments, and a conclusion wrapping up your ideas.

The structure of the body is flexible, but you should always spend some time thinking about how you can organize your essay to best serve your ideas.

Your essay introduction should include three main things, in this order:

- An opening hook to catch the reader’s attention.

- Relevant background information that the reader needs to know.

- A thesis statement that presents your main point or argument.

The length of each part depends on the length and complexity of your essay .

A thesis statement is a sentence that sums up the central point of your paper or essay . Everything else you write should relate to this key idea.

A topic sentence is a sentence that expresses the main point of a paragraph . Everything else in the paragraph should relate to the topic sentence.

At college level, you must properly cite your sources in all essays , research papers , and other academic texts (except exams and in-class exercises).

Add a citation whenever you quote , paraphrase , or summarize information or ideas from a source. You should also give full source details in a bibliography or reference list at the end of your text.

The exact format of your citations depends on which citation style you are instructed to use. The most common styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bryson, S. (2023, July 23). Example of a Great Essay | Explanations, Tips & Tricks. Scribbr. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/example-essay-structure/

Is this article helpful?

Shane Bryson

Shane finished his master's degree in English literature in 2013 and has been working as a writing tutor and editor since 2009. He began proofreading and editing essays with Scribbr in early summer, 2014.

Other students also liked

How to write an essay introduction | 4 steps & examples, academic paragraph structure | step-by-step guide & examples, how to write topic sentences | 4 steps, examples & purpose, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Conversational Analysis: Exploring Social Interactions

Introduction

Conversation analysis: an overview, what are the basic principles of conversational analysis, conversation analysis example, how is conversation analysis carried out, challenges of conversation analysis.

From pauses to thinking words, from changes in volume to emphasis on words, conversation analysis looks at all the different ways meaning is embedded and understood in social interaction. In linguistics, conversation analysis plays a role in discourse analysis by focusing less on what people say and more on how they say it.

That said, there are numerous challenges and complexities relating to how people speak, how speech is understood, and how conversation shapes meaning, social relationships, and cultures. Collecting data to document and analyze the complexity of spoken interactions, as a result, is an equally daunting task, requiring a deep consideration of this analytical approach in detail.

In this article, we will look at conversation analysis, techniques used to conduct conversation analysis effectively, and challenges that researchers face when analyzing social interaction.

Conversation analysis examines concepts of speech acts that are non-verbal in nature such as speaking speed, intonation, word stress, and length of pauses. In contrast, discourse analysis focuses on understanding human communication through analyzing words, their meaning, the intentions behind them, and the underlying assumptions that inform them. Conversation analysis instead focuses on the non-verbal cues in social interactions.

What is the function of conversational analysis?

Conversation analysis theory acknowledges the importance of non-verbal cues present in interaction. Without these cues, interaction looks and sounds very different and perhaps unnatural.

For example, when someone answers a question, how confident are they in their answer? We can infer their level of confidence in the way they speak. Maybe they pause in between words because they are mentally searching for the right words. Perhaps they emphasize certain words in their answer because they are speaking from a place of authority and expertise.

The goal of conversation analysis is to document the ways that speakers interact with each other. The challenge is that the written form used in research papers and presentations does not lend itself to showing non-verbal information embedded in communication. We as research writers use prose and bulleted lists and rely on words to convey meaning.

As a result, it's incumbent on researchers employing conversation analysis to present their research with a strong conversation analysis essay or presentation that visualizes interaction. Searches for communication studies often produce research that provides various conversation analysis examples that make use of notations to mark the various non-verbal cues accompanying interaction.

Details captured in conversation analysis

Undertaking conversation analysis means analyzing the various features and developments of interaction and presenting them in an empirical manner that leads to theoretical development. While many other research inquiries that look at data from interviews and focus group discussions primarily examine the meaning of words and the co-construction of knowledge, conversation analysis acknowledges the importance of the accompanying features of interaction in influencing that meaning.

Some details captured in conversation analysis include, but are not limited to, the following:

- turn-taking

- interruptions

- thinking words

- word stress

- body language

Think about how each of these details, in isolation or in conjunction with each other, can make an interaction look and sound fundamentally different than an interaction without these details. Their contribution to the nuances of interaction justify the utility of conversation analysis among researchers in linguistics.

Distinguishing conversation analysis from discourse analysis

You can think of conversation analysis and discourse analysis either as complementary approaches or as one being a subset of the other. Either way, they have distinct approaches and objectives that are worth exploring in discrete detail.

Discourse analysis investigates the use of language in all aspects, from the meaning that is conveyed to the way that it is conveyed and why. Understanding discourse means acknowledging the larger context around language and communication and how that context informs meaning, cultures, and social relations.

Another approach is critical discourse analysis, which examines the use of language as an exercise of power. How politicians, business executives, and other people in power communicate messages is an important area of study that captures how ideas are shaped to reaffirm the power of institutions.

On the surface, it may not seem that there is significant overlap between conversation analysis and these other analytical approaches. However, the main thing in common between conversation analysis and discourse analysis is the assumption that the meaning of words is complemented by a whole host of other contextual cues, cultural assumptions, and situational considerations.

Turn qualitative data into actionable insights with ATLAS.ti

Get the most out of your research with our intuitive data analysis tools. Download a free trial today.

Conversation analysis is more of a broad analytical approach rather than a strict methodology that warrants definition. However, there are a number of guiding principles that researchers should acknowledge when conducting conversation analysis:

- Empirical focus . There is an understanding among conversation analysis researchers that, given the dynamics of naturally occurring spoken interactions, spoken discourse can be captured and analyzed in a systematic manner. An empirical focus to conversation analysis can capture data and structure it in a way that allows researchers to identify recurring patterns from the interactional data.

- Context sensitivity . At the same time, researchers also acknowledge that the universal rules for interaction are all but elusive as interactions are informed by cultures, contexts, and individual differences. How speakers interact with each other in one culture is bound to differ from speakers in other cultures, so it is incumbent on researchers to place interactions in their situated contexts to provide sufficient definition to the theoretical developments they propose.

- Order in interaction . More often that not, people in interaction respond to each other in a process called turn-taking. This is easy to observe in a conversation involving two people, but how does this play out in a situation involving three or more speakers? As a result, researchers also employ conversation analysis to understand power dynamics between speakers, particularly those of different statuses or positions, or those with particular relationships.

- Indexicality . Research employing conversation analysis often examines the semiotic systems - or the ways in which people communicate and understand meaning - that guide interaction. A major component of semiotics is indexicality, or the concept where meaning is tied to "signs" in interaction such as gestures, pronouns, and accents. Capturing this indexicality thus requires situating interactions in sufficient context at the individual and macro levels.

- Data-driven analysis . Conversation analysis is primarily an inductive approach to understanding interactional data. While some research inquiries in conversation analysis may involve hypothesis testing or experimental study that can be deductive in nature, theoretical developments in conversation analysis typically arise from the data itself. This is an important feature of this analytical approach, especially when inductively analyzing culture and language.

The concept of Phonetics of Talk in Interaction provides a useful example where conversation analysis can prove relevant. Think about how mothers talk to their babies, and how this talk might be different among adults, or even between adults and children who are able to speak.

At least in Western contexts, mothers tend to repeat the nonsensical utterances their babies might make. They may also exaggerate their pronunciation of words or speak more slowly. Why they do this is fundamental to understanding parenting, making the empirical collection of data that represents these phenomena important to research about parenting and communication.

Other conversation analysis examples can look at how intonation and prosody inform communication. Consider the question "What did you do last night?" A speaker can emphasize any word in that question and the nuance might change accordingly. If they emphasize "what" or "night," the assumptions we can make about the speaker regarding what they are interested in and what they assume about who they are talking to are bound to change.

Conversation analysis can also look at how communication features like turn-taking, prosody, non-verbal gestures, and facial expressions might change across forms of interaction. Indeed, the way that people take turns in an online meeting can look fundamentally different from the turn-taking in face-to-face communication, prompting researchers to explore how online communication shapes interaction in different ways.

Conversation analysis typically has an established process that, in many ways, mirrors the process for other forms of qualitative research . That said, researchers should keep some additional considerations in mind while conducting conversation analysis.

- Data collection . Observations , interviews , and focus group discussions typically involve data collection by the use of an audio recorder. In addition, you may want to keep track of non-verbal utterances and other developments of note by using a video recorder or taking notes during data collection . Your data collection may also focus on different specific types of interaction, such as speeches, discussions, and dialogues.

- Conversation analysis transcription . Transcription is the process of turning raw audio or video into written text representing the words uttered in an interaction. When employing conversation analysis, you will likely want to consider transcribing as much detail as possible to capture spoken interaction subtleties. Thinking words, repetitions, errors in grammar and sentence structure, and other features of interaction that may not be linguistically accurate should all be included for the purpose of analysis. You may also include notations to indicate where relevant non-verbal cues occurred.

- Reflections on data collection . Reflections and realizations may come to you during the course of data collection which can inform your analysis. Conversation analysis notes and memos can be a useful component of the research process as they can point to important features of communication that warrant analysis or potentially novel theoretical developments regarding interaction.

- Notation of transcripts . A conversation analysis looks to examine spoken interactions closely by presenting utterances in extensive detail. However, when research papers and presentations rely on the written form to convey their findings, it's important to have a system in place for transcribing and marking up interaction data. The Jeffersonian transcription system is a form of notation commonly used in conversation analysis research to mark up details like turn-taking, pauses, and prosody. Other systems such as systemic functional linguistics transcription and phonetic transcription also exist, so you can choose the most appropriate approach for the research question you are exploring.

Developing expertise in conversation analysis requires an approach to qualitative data that differs from other methods such as thematic analysis and content analysis . A good deal of data organization is necessary to provide the structure that allows for an analysis of interactions that captures conversation analysis concepts in a rigorous fashion.

There are a number of methodological and logistical concerns to keep in mind when conducting conversation analysis.

- Equipment for data collection . The tasks of collecting conversational data can prove challenging when they rely on capturing as much granular detail as possible to facilitate writing realistic dialogue in research papers and presentations. A standard audio recorder might accomplish most tasks in conversation analysis, but if your research question relies on specific details in interaction such as intonation and word stress, more sensitive audio or video recording equipment might be necessary.

- Transcription . Transcribing natural spoken interactions remains an inherently subjective process despite the growing body of studies that employ conversation analysis. The manner in which you transcribe utterances should aim to be consistent and comprehensive in capturing as much detail as possible. Some people use more thinking words and sounds than others, while others may repeat words or stutter while speaking.

- Notation . Marking up research transcripts in a consistent and rigorous manner is yet another subjective component of conversation analysis. How do you measure pauses between words? What constitutes a sufficient rise or fall in intonation to warrant notation? Which syllables in a word does the speaker emphasize? Simply using a standard, established notation is not enough; it's far more important to apply it consistently in a way that your research audience can understand.

- Research and writing process . When employing conversation analysis, essay writing becomes a formidable task when it comes to persuading the research audience. A comprehensive conversation analysis essay requires an empirical approach to presenting findings in a manner that is easy for your research audience to understand. If you are presenting examples of your conversation analysis in written form, consider using a common notation that adheres to consistent standards. In addition, be sure to explain your data and analysis thoroughly enough to immerse your audience in the context of your data and the theoretical developments it illustrates.

Make ATLAS.ti your qualitative data analysis solution

Superior data analysis tools are just a click away. Download a free trial of our powerful analysis software.

Here you can find activities to practise your speaking skills. You can improve your speaking by noticing the language we use in different situations and practising useful phrases.

The self-study lessons in this section are written and organised by English level based on the Common European Framework of Reference for languages (CEFR). There are videos of different conversations at work and interactive exercises that practise the speaking skills you need to get ahead at work and communicate in English. The videos help you practise saying the most useful language and the interactive exercises will help you remember and use the phrases.

Take our free online English test to find out which level to choose. Select your level, from A1 English level (elementary) to B2 English level (upper intermediate), and improve your speaking skills at your own speed, whenever it's convenient for you.

Choose a speaking lesson

A1 speaking

A2 speaking

B1 speaking

B2 speaking

Learn to speak english with confidence.

Our online English classes feature lots of useful learning materials and activities to help you develop your speaking skills with confidence in a safe and inclusive learning environment.

Practise speaking with your classmates in live group classes, get speaking support from a personal tutor in one-to-one lessons or practise speaking English by yourself at your own speed with a self-study course.

Explore courses

Online courses

Group and one-to-one classes with expert teachers.

Learn English in your own time, at your own pace.

One-to-one sessions focused on a personal plan.

Get the score you need with private and group classes.

- Conversation Between Two Friends

Conversation between Two Friends in English

All of us, irrespective of our age, have friends. From among the number of friends we have, there might be one or two of them with whom we communicate each and every thing that happens in our lives. A day without a conversation with our friend might make us feel incomplete. A conversation between two friends can be based on the most trivial of things to the most serious ones.

Conversation writing helps to enhance children’s creative power. It helps them imagine all the possible kinds of conversations that might take place between two or more people in a given situation. Writing a conversation that occurs between two friends can be an easy and effective job if you learn how to capture the emotion conveyed.

This article will help you with a few examples of conversations between two friends in multiple situations. Check them out and try to understand how it can be done.

Table of Contents

Sample conversation 1 – between two friends who meet in a restaurant.

- Sample Conversation 2 – A Telephonic Conversation between Two Friends about a Reunion

Sample Conversation 3 – Between Two Friends Discussing a Movie

Rita – Hey Tina? Is it you?

Tina – Oh Rita! How are you? It’s been a long time.

Rita – I am fine, what about you? Yes, we last met during the board exams.

Tina – I’m good too.

Rita – What are you doing now?

Tina – Well, I have started my undergraduate studies in English Honours at St. Xaviers College in Mumbai.

Rita – Wow! You finally got to study the subject you loved the most in school.

Tina – True. What about you Rita? Wasn’t History your favourite subject?

Rita – You guessed it right. I took up History Honours in Lady Shri Ram College for Women in Delhi.

Tina – That’s nice. I am so happy for you.

Rita – I am happy for you too. Let’s meet up again soon.

Tina – Yes, sure! We have a lot to catch up on.

Rita – Bye for now. I have to pick up my sister from tuition. Take care.

Tina – Bye, will see you soon.

Sample Conversation 2 – A Telephonic Conversation Between Two Friends about a Reunion

Jay – Hello? Am I talking to Prateek Agarwal?

Prateek – Hello. Yes, I am Prateek Agarwal. May I ask who is speaking?

Jay – Prateek, it’s me Jay Roy from college. Remember?

Prateek – Hey Jay, how are you? It has been such a long time.

Jay – I am doing good. Yes, four long years after college. I got your contact number from Piyush. You remember him, right?

Prateek – Yes, yes, I do remember him. Wasn’t he the one who topped our engineering batch last year?

Jay – Yes, that’s him! He’s in Boston working for a big MNC now.

Prateek – Wow! Good for him.

Jay – The main reason I called you up is because I am planning to organise a reunion of our batch and wanted to know if you could make it.

Prateek – Really? Yes, I would love to attend the reunion. Just let me know the time and venue.

Jay – Do you remember the auditorium of our college where we had our orientation program?

Prateek – How can I forget that auditorium? We all have spent so much time in that place over the years.

Jay – That’s the place for our reunion. I called up the college regarding this and they gave us permission to have the reunion there. In fact, some of our professors might also be there. I’ve sent out invitations to them too.

Prateek – Splendid! I am eagerly looking forward to the reunion.

Jay – I have to contact a few others too. I will let you know the details within two days. Meet you soon. Bye

Prateek – Sure, Bye.

Anjali – Hi, Raj. How was your weekend?

Raj – Hey, Anjali. My weekend was great. I watched a great movie.

Anjali – Oh really? What was the name of the movie you watched?

Raj – I watched Avengers Endgame. It is the last movie of the Avengers.

Anjali – Oh, I have watched Avengers Endgame too. I loved the movie.

Raj – Really? Who is your favourite Avenger?

Anjali – I can’t name one! Iron Man, Thor, Captain America, Captain Marvel, Scarlet Witch and Black Widow, to name a few.

Raj – Wow, you have some of the strongest Avengers there! I have the same choice except that I loved Spider Man too.

Anjali – My sister took me to see the movie as soon as it was released. Both me and my sister have been great fans of Avengers since childhood.

Raj – Oh wow! I am myself a big fan of Avengers and have watched all the movies. I too wanted to go to the theatre and watch the movie, but I was out of station for a family function.

Anjali – Oh I see. The movie stood up to all the expectations that the audience had after watching the trailer. In fact, I would say the movie surpassed expectations.

Raj – Very true. There was no better way to finish the Avengers, I believe. The movie just took me through a rollercoaster of emotions.

Anjali – True! Just when I was feeling happy that the Avengers got rid of Thanos for good, the next moment I was bawling my eyes out seeing Iron Man had sacrificed himself to save the world and everyone else.

Raj – We can’t ever see Black Widow, Iron Man and Captain America ever in any Marvel movies.

Anjali – Yes, very sad. Anyway it was nice talking to you. See you tomorrow in school. Bye.

Raj – Same here. Bye.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is a conversation.

A conversation is a type of communication that takes place between two or more people. Through conversation, people communicate different ideas, thoughts and information.

How many types of conversation are there?

There are four types of conversations namely debate, dialogue, discourse and diatribe.

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

- 101 English Conversations

- English Tips

- Improve Your English

- 120 Common English Phrases

- Mistakes in english

- Tools for Learning English

- English for Work

- English Grammar

- English Conversations in Real Life

- American English Conversations (Video)

- Everyday Conversation: 100 Topics

- English Listening

- English Writing

- English Idioms

- Elementary Level

- Intermediate Level

- Advanced Level

- Synonyms and Antonyms Dictionary

- Academic Words

- CNN Student News

- Holidays Worldwide

- American Life

Today, we would like to share with you the 100 Basic English conversations . The topics level for English beginners. If you are a newbie in learning English, they are suitable for you. And as I mentioned in some articles, practicing with conversation is one of the best methods to improve your English. The following lessons cover 100 daily topics that you will speak about in your daily life.

Let’s get started!

- Lesson 1: Where are you from?

- Lesson 2: Do you speak English?

- Lesson 3: What is your name?

- Lesson 4: Asking for directions

- Lesson 5: I’m Hungry

- Lesson 6: Do you want something to drink?

- Lesson 7: That’s too late!

- Lesson 8: Choosing a time to meet

- Lesson 9: When do you want to go?

- Lesson 10: Ordering Food

- Lesson 11: Now or Later?

- Lesson 12: Do you have enough money?

- Lesson 13: How have you been?

- Lesson 14: Introduce a Friend

- Lesson 15: Buying a Shirt

- Lesson 16: Asking about Location

- Lesson 17: Do you know the address?

- Lesson 18: Vacation to Canada

- Lesson 19: Who is that Woman?

- Lesson 20: Common Questions

- Lesson 21: The Supermarket is closed

- Lesson 22: Do you have any Children?

- Lesson 23: Help with Pronunciation

- Lesson 24: I lost My Watllet

- Lesson 25: Phone Call At Work

- Lesson 26: Family Trip

- Lesson 27: I Went Shopping

- Lesson 27: What kind of Music do you like

- Lesson 29: Going to the Library

- Lesson 30: Where do your Parents live?

- Lesson 31: Can you help me find a new thing?

- Lesson 32: Paying for Dinner

- Lesson 33: Buying a plane ticket

- Lesson 34: Putting things in order

- Lesson 35: At the Restaurant

- Lesson 36: I need to do laundry

- Lesson 37: Finding a convenience Store

- Lesson 38: Geography and Direction

- Lesson 39: I ate at the Hotel

- Lesson 40: Going to the Movies

- Lesson 41: I need to do laundry

- Lesson 42: Helping a friend move

- Lesson 43: Visiting Family

- Lesson 44: Looking at Vacation Pictures

- Lesson 45: Ordering Flowers

- Lesson 46: Leaving a Message

- Lesson 47: Talking about the Weather

- Lesson 48: Making Plans

- Lesson 49: Meeting a Friend

- Lesson 50: I’m Student

- Lesson 51: Studying for exams

- Lesson 52: Did you get my message

- Lesson 53: Mail

- Lesson 54: I have a cold

- Lesson 55: Dinner invitation

- Lesson 56: Send me the directions

- Lesson 57: Bad cell phone reception

- Lesson 58: Going to the gym

- Lesson 59: Car accident

- Lesson 60: Doctor’s visit

- Lesson: 61: Doctor’s visit

- Lesson: 62: Making a hotel reservation

- Lesson: 63: I changed my mind

- Lesson: 64: Do you want to play a game

- Lesson: 65: Birthday present

- Lesson: 66: Checking into a hotel

- Lesson: 67: Sending a package

- Lesson: 68: I have allergies

- Lesson: 69: Josh works at a software company

- Lesson: 70: Listening to music

- Lesson 71: Taking a taxi

- Lesson 72: We’re not lost

- Lesson 73: Help me find my purse

- Lesson 74: Taking pictures

- Lesson 75: I dropped your calculator

- Lesson 76: I brought you an apple

- Lesson 77: My mother-in-law is coming tomorrow

- Lesson 78: Jim canceled the meeting

- Lesson 79: Bill got fired

- Lesson 80: Nervous about surgery

- Lesson 81: A romantic story

- Lesson 82: Worried about dad

- Lesson 83: I’m getting fat

- Lesson 84: I’ll take you to work

- Lesson 85: Snowing outside

- Lesson 86: Missed call

- Lesson 87: Shopping for a friend

- Lesson 88: What is your major

- Lesson 89: New apartment

- Lesson 90: Have you found a girlfriend yet

- Lesson 91: Computer problems

- Lesson 92: Do you know how to get downtown

- Lesson 93: Did you see the news today

- Lesson 94: What’s your favorite sport

- Lesson 95: Making a webpage

- Lesson 96: Would you mind driving

- Lesson 97: Your English is so good

- Lesson 98: Gifts

- Lesson 99: Election

- Lesson 100: Book club

101 English Conversations: English Speaking Practice with Conversation in 3 Steps

How to practice English speaking on your own and at Home?

I’m sure that you often look up this keyword on Google search “ English speaking practice “, “ How to practice English speaking “, “ English Speaking Tips “, or “ how to improve speaking skill “…to find out a suitable method for your own. Today, I’m very happy to share with you 5 simple ways to practice speaking at home…

Read more: How to practice English speaking on your own

===========

If you need professional help with English essay writing, please visit smart essay writing service – its team of pro academic writers will assist you online.

Other English Conversations in Real Life: https://helenadailyenglish.com/english-conversations-in-real-life-with-common-phrases-meaning-example

#helenadailyenglish.com

- Online Testing

©helenadailyenglish.com. All rights reserved by Helena

- Entertainment

I Made a Show About Talking to White Nationalists. Then I Talked to My Audience

F or promotional purposes, I am often asked to sum up Just For Us . Sometimes, I get very technical and say it’s a comedy-theater hybrid, or a solo show about assimilation or something high-minded, but what usually happens is that the interviewer stares at me until I give them what they want. Which is this:

Just For Us , if you must know, is a show about a guy who attends a meeting of White Nationalists in Queens. The thing that makes this hooky, presumably, is the fact that that guy (me, I’m the guy) was raised as an Orthodox Jew.

Eventually, I’m found out. The resultant story, as crafted for the stage with a few related comedic tangents, wound its way through the Anglophone live comedy world over the past six years, making some fun stops— Broadway , Montreal, Australia—before it airs on HBO April 6.

And the thing I like most about my corner of the pixelated comedy landscape, my own stall now set out at the farmers market of online streaming, is the tens of thousands of people who have come to see it live; stopped and visited and left their fingerprints on my countertop. In the comet’s tail behind the show there have been innumerable conversations afterwards in the lobby, bar, or the middle of the sidewalk outside the venue. Anyone with the patience and wherewithal to ask a question, has.

Not all the conversations have been good or illuminating. There are a lot of watery compliments, or Jewish geography (over the five years I attended a Jewish summer camp , I seem to have overlapped with literally everyone’s cousin). A nice man in Detroit complained that I don’t offer any answers, only more questions. Fair. The queries aimed at me mostly revolve around the White Nationalists in the room that night back in 2018. Am I still in touch? I am not. Would I do it again? Yes. Have any of them seen the show? No idea. I thought I saw one of them in Union Square in 2022, but going up to a stranger to ask, “Hey, do I know you from a meeting of White Nationalists?” struck me as a bad move.

Because of the nature of live performance, and the way we tell stories, some of those conversations, besides being a more explicit window into what people respond to, have found their way into the show itself—which is wild. The show is different from the show it was six months ago, a year ago, six years ago. I didn't even present as Jewish in the original draft of it. To offer work that is a living thing, responsive to the world around it, is a unique experience. It’s a bit like if you were watching a movie and DiCaprio got to look directly into camera and say, “People get really sad here, when we hit the iceberg .” Live theater! It’s the best.

And in the post-show conversations that light me up the most, I find my tribe: people animated by curiosity or a unique approach to discourse. They’re interested in the craft of telling a story, or they talk about a time where they connected with someone very different from them, or offer an anecdote about wandering into a room where they did not belong. After a show in Wales, out of nowhere, a woman in her seventies told me she liked “that I knew enough to listen” in that room. When I told her that the opinions at this meeting of White Nationalists were pretty offensive, regressive, etc., she said to me, genuinely baffled, “What does that have to do with listening?”

Read more: How to Have More Meaningful Conversations

I now see that extant desire to listen and be heard, to be seen and understood, in so much. I catch glimpses of it in our newspapers, in courtroom testimonies, on Love is Blind .

I read once that there is nothing more romantic than being seen, and the average American is, in my opinion, looking for romance. I’m not naive enough to think that we can head for a kumbaya moment that sees MAGA conservatives locked in tear-soaked embrace with Joy Behar , but I’m encouraged by that desire for understanding—especially from those who are different from us. I think it accounts for a huge amount of the resonance that Just For Us has had.

A few weeks ago, after a show in Atlanta, someone asked me, framed through their anger at another’s position on the current conflict in Gaza , “What should be the limits of our empathy?” I told them that I don’t know, but I think the more you can extend, the more of the opposing perspective you can come to grips with, the higher your chances are of reaching something productive. It’s an answer I don’t know that I would’ve given six years ago. I’m resistant to “what I’ve learned” stuff from comedians and solo show artists—it’s very pat—but I can say what’s changed for me. Which is that I’ve found much more productivity when I can remove my self-righteousness from my arguments. I’ve found a surprising appetite for grace in the average person. And, I’ve found so much more comfort in asking questions than offering answers. Sorry, guy from Detroit.

Alex Edelman is a comedian and writer based in New York City. His debut comedy special Alex Edelman: Just for Us premieres on Saturday, April 6 on HBO and streaming on Max.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Passengers Are Flying up to 30 Hours to See Four Minutes of the Eclipse

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Essay: The Complicated Dread of Early Spring

- Why Walking Isn’t Enough When It Comes to Exercise

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

You May Also Like

Daily English Conversation Practice – Questions and Answers by Topic

You have troubles making real English conversations ? You want to improve your Spoken English quickly? You are too busy to join in any English speaking course?

Don’t worry. Let us help you.

First of all, you need to learn the most frequently used words in English , common structures and sentence patterns , common expressions , common phrasal verbs , and idioms that are much used in daily life.

Next, you should learn daily conversations in English for speaking. Focus on every ESL conversation topic until you can speak English automatically and fluently on that topic before moving to the next one.

The following lessons cover 75 topics that you will face very often in your daily life. Each lesson is designed in form of ESL conversation questions and answers, followed by REAL English conversation audios, which will definitely benefit your English conversation practice.

ESL Conversation Questions and Answers – 75 Topics

1. Family 2. Restaurant 3. Books 4. Travel 5. Website 6. Accident 7. Childhood memory 8. Favorite rooms 9. Presents 10. Historical place 11. Newspaper/ Magazine 12. A memorable event 13. A favorite subject 14. A museum 15. A favorite movie 16. A foreign country 17. Parties 18. A teacher 19. A friend 20. A hotel 21. A letter 22. Hobbies 23. Music 24. Shopping 25. Holiday

26. Animals 27. A practical skill 28. Sport 29. A School 30. Festival 31. Food 32. Household appliance 33. A music band 34. Weather 35. Neighbor 36. Natural scenery 37. Outdoor activities 38. Law 39. Pollution 40. Traffic jam 41. TV program 42. Architect/ Building 43. Electronic Media 44. Job/ Career 45. Competition/ contest 46. A garden 47. Hometown 48. Clothing 49. Advertisement 50. A project

51. A wedding 52. A Coffee shop 53. Culture 54. Transport 55. Politician 56. Communication 57. Business 58. Computer 59. Exercise 60. Goal/ ambition 61. Art 62. Fashion 63. Jewelry 64. Cosmetic 65. Indoor Game 66. Phone conversation 67. Learning A Second language 68. A Creative Person 69. A celebrity 70. A Health Problem 71. Technological advancements 72. A Landmark 73. Handcraft Items 74. Plastic Surgery 75. Success

Download Full Lessons Package – Daily English Conversation by Topic (mp3+pdf)