Should the Legal Drinking Age be increased to 21?

Readers Question: Evaluate the case for raising the legal drinking age to 21. Will it be more effective than other methods for reducing the harmful effects of alcohol?

There are several reasons to be concerned about the over-consumption of alcohol, especially amongst young people. In the UK, abuse of alcohol has contributed to several social, economic and health problems, including:

- Alcohol-related accidents.

- Health problems

- Alcohol addiction is a major cause of family breakdown.

- According to a report , “Health First: An evidence-based alcohol strategy for the UK”. “The personal, social and economic cost of alcohol has been estimated to be up to £55bn per year for England and £7.5bn for Scotland,”

- Research carried out by Sheffield University for the government shows a 45p minimum price would reduce the consumption of alcohol by 4.3%, leading to 2,000 fewer deaths and 66,000 hospital admissions after 10 years. Researchers also claim the number of crimes would drop by 24,000 a year.

From an economic perspective, we say that alcohol is a demerit good .

- People may underestimate the personal costs of drinking alcohol to excess (especially amongst young people)

- There are external costs to society, e.g. costs of health care, costs of treating accidents, days lost from work. Therefore the social cost of alcohol is greater than the private cost.

These two factors give a justification for government intervention to deal with some issues related to alcohol. Raising the legal drinking age could help reduce these personal and social costs because it is more difficult to purchase.

Arguments against raising the drinking age to 21

- At 18, people can vote and are considered adults, so we should allow them to have a personal decision on whether to consume alcohol.

- Alcohol in moderation isn’t necessarily harmful. Rather than a blanket ban, the government could focus on tackling binge drinking through making alcohol more expensive and tackling the drinking culture.

- Drinking alcohol is so embedded in the culture, raising the legal age to 21, will make the majority of young people break the law.

- It will encourage people to find ways to circumnavigate the law. Black market alcohol supplies, which may be harder to monitor.

- Arguably, there are better ways to deal with problems of alcohol.

Will raising the drinking age to 21 be effective?

Raising the drinking age to 21 will reduce consumption amongst young people because it will be harder to buy alcohol. Also, young people are the most likely group to misuse alcohol; e.g. drinking to excess, which causes accidents, death and health problems. If people start drinking later in life, they may be more likely to drink in moderation and not get addicted at an early age.

However, it will still be possible for young people to drink at home. People will find ways to avoid the legislation e.g. asking older people to buy alcohol for them. Nevertheless, it will be more difficult. For example, a 16-year-old may not be able to get away with drinking in a pub any more. If the age is 18, it is much easier for a 16 or 17-year-old to get away with drinking alcohol.

This policy doesn’t address the underlying problem of why people want to drink to excess. For that education may be a better solution; education could help to explain the dangers of excess drinking and therefore encourage young people to drink moderation. However, previous education policies have not seemed to be very effective. Young people don’t want to hear lectures from the government about the dangers of alcohol.

Other Solutions

Higher taxes increase the cost of alcohol and may have a significant effect in reducing demand amongst young people, who have lower disposable incomes. If demand is reduced by say 20% this may reduce many of the problems of over-consumption. This policy also raises revenue for the government. But, on the other hand, it may increase the incentive to import low duty alcohol from abroad. Demand for alcohol may also be inelastic and not effective in stopping consumption.

- Tax on alcohol

- Minimum price for alcohol – pros and cons

In practice, there is very little that the government can do to change social and individual attitudes to alcohol, which is the root cause of most alcohol abuse.

In the US the legal drinking age is 21. They still have many alcohol-related problems, but, it is significantly more difficult for young people to regularly drink alcohol.

What do you think – should alcohol be illegal for under 21s?

91 thoughts on “Should the Legal Drinking Age be increased to 21?”

Personally I think the legal drinking age should be raised to 20 and encourage awareness at younger ages towards responsible drinking toward drinking at a party among people you know, at a pub with a way home, in your own home, but not at work, or in a car, in the open and watching how you mix your drinks. To drink responsibly you have to be responsible for yourself. I think 20 will just give people more time to mature before they make choice like if and when to drink.

I agree with your opinion!

Hi economicshelp.org,

Yes I agree with you that legal drinking age should be up by 21. Because many teens right now are struggling in alcohol addiction regards.

Dont take nothing up to any age… leave things be… we too young to be worrying about anything

Im a 16 year old who loves a good time. Partying is in my genes and so ill admit I sometimes enjoy a glass of rose at home with my mum. I don’t think there is anythig wrong with this as it only gets me tipsy *wink wink* I would argue that the drinking age should be reduced! Keep on partying ya’ll! Quinn out!

Comments are closed.

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- 2024 election

- Solar eclipse

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

Sorry, college students, but the drinking age should stay at 21

Share this story.

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Sorry, college students, but the drinking age should stay at 21

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/48555775/486298818.0.jpg)

It seems like conventional wisdom: The drinking age should be 18. After all, why should you be able to vote or serve your country in the military, but not legally buy a drink?

But there's a very compelling case for keeping the drinking age at 21: It saves lives. That may be hard to believe, given how many people flout the laws and drink anyway, but it's been consistently found to be true in research.

Saving lives from alcohol has serious public health benefits. About 88,000 Americans died on average each year from alcohol-related causes from 2006 to 2010, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . And that estimate doesn't account for the rise in alcohol-related deaths over the past several years, or the alcohol-linked crimes and millions of emergency room visits each year that don't result in deaths.

It's important to note a minimum drinking age of 21 doesn't prevent all drinking among teenagers and 20-year-olds. But it deters some drinking, and that has public health benefits.

The drinking age saves lives

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/4176054/467650191.0.jpg)

At its heart, the drinking age is supposed to stop people from drinking until they're responsible adults. And the research shows it works — to some extent.

"The evidence is overwhelming [that] raising the age reduces consumption," said Richard Bonnie, a University of Virginia professor of health and law. "Even though consumption remains significant among the younger population and increases as people get older, it's still lower than it would be if you lowered the age to 18."

A 2014 review of the research published in the Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs bore this out: Although many young people disobey the drinking age, the evidence shows that it has depressed drinking and saved lives.

The review found the drinking age saves at least hundreds of young lives annually just as a result of reduced alcohol-age-related traffic fatalities among underage drivers. The review pointed to one study after the National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984, which raised the legal drinking age from 18 to 21: It found that the number of fatally injured drivers with a positive blood alcohol concentration decreased by 57 percent among ages 16 to 20, compared with a 39 percent decrease for those 21 to 24 and 9 percent for those 25 and older. Other studies had similar positive findings.

Chances are the number of lives saved is higher, potentially in the thousands each year, when accounting for alcohol-related deaths beyond drunk driving, such as liver cirrhosis, other accidents, and violent behavior.

The review also pointed to New Zealand, which reduced its drinking age from 20 to 18 in 1999. The country saw significant increases in drinking among ages 18 to 19, bigger increases among those 16 to 17 years old, and a rise in alcohol-related crashes among 15- to 19-year-olds.

How the drinking age works

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/5900269/176458449.jpg)

Critics of the drinking age commonly argue that it forces youth to drink in secret, which may lead to binge drinking as people stash booze to secretly consume all at once. But the 2014 review of the research found no evidence for this, and instead concluded that the national drinking age law reduced access to alcohol and consumption.

"The basic idea behind these laws is to reduce youth access to these substances," William DeJong, a professor at Boston University School of Health and a co-author of the research review, wrote in an email. "The evidence is clear that, the later a young person takes a first drink, the less likely they are to experience negative alcohol-related consequences as adults."

The law accomplishes this in two big ways. Obviously, it makes it harder to buy alcohol before 21. But it also breaks up social groups in a way that makes alcohol less accessible: If the drinking age were 18, someone who is a freshman or sophomore in high school is much more likely to have access to an 18-year-old senior in high school. But if the drinking age is 21, a freshman or sophomore in high school is not going to have as easy of access to a 21-year-old who's likely working or in college.

The second effect — the breaking up of social groups — also explains why a drinking age beyond 21 might not be very effective. Since 21-year-olds are likely to have access to 25-year-olds through their jobs and college, they could still easily access booze even if the drinking age was raised to, for example, 25. So the negative effects of raising the drinking age to 25 — the economic impact, costs of enforcement, and deterioration of personal freedoms — might not be worth the few lives saved.

These principles apply to other substances, as well. A 2015 report from the Institute of Medicine, which Bonnie of the University of Virginia contributed to, found raising the smoking age to 21 could prevent approximately 223,000 premature deaths among Americans born between 2000 and 2019. Why? Older friends and family "are largely where young people get their tobacco," Bonnie said. "If you raise [the smoking age] to 21, over time we think that's going to have a significant effect on separating these social networks."

So the laws may not be perfect, and they may be disobeyed at times. But the overall evidence is clear: A drinking age of 21 reduces use and saves lives.

Other policies can help reduce alcohol consumption

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/5900189/451941478.jpg)

The drinking age, however, should be just one part of a broader array of policies that help reduce alcohol abuse and deaths.

Many, many studies, for example, have found benefits from a higher alcohol tax. A recent review of the research from David Roodman, senior adviser for the Open Philanthropy Project, made the case:

[H]igher prices do correlate with less drinking and lower incidence of problems such as cirrhosis deaths. And I see little reason to doubt the obvious explanation: higher prices cause less drinking. A rough rule of thumb is that each 1 percent increase in alcohol price reduces drinking by 0.5 percent. Extrapolating from some of the most powerful studies, I estimate an even larger impact on the death rate from alcohol-caused diseases: 1-3 percent within months. By extension, a 10 percent price increase would cut the death rate 9-25 percent. For the US in 2010, this represents 2,000-6,000 averted deaths/year.

This wasn't the first positive finding in favor of raising the alcohol tax, but it was one of the most convincing. Roodman found not just that high-quality research supports a higher alcohol tax, but that the effects seem to grow stronger the higher the tax is.

So for the US, boosting alcohol prices 10 percent could save as many as 6,000 lives each year. To put that in context, paying about 50 cents more for a six-pack of Bud Light could save thousands of lives. And this is a conservative estimate, since it only counts alcohol-related liver cirrhosis deaths — the number of lives saved would be higher if it accounted for deaths due to alcohol-related violence and car crashes.

Aside from raising taxes, a 2014 report from the RAND Drug Policy Research Center suggested state-run shops (like those in Ohio and Virginia) kept prices higher, cut access to youth, and reduced overall levels of use. And a 2013 study from RAND of South Dakota's 24/7 Sobriety Program , which briefly jails people whose drinking has repeatedly gotten them in trouble with the law (like a DUI) if they fail a twice-a-day alcohol blood test, attributed a 12 percent reduction in repeat DUI arrests and a 9 percent reduction in domestic violence arrests at the county level to the program.

Like the drinking age, these policies won't eliminate problematic drinking. But coupled with the drinking age, they can help — and potentially save tens of thousands of lives in the process.

Watch: Alcohol is more dangerous than marijuana

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

At Vox, we believe that clarity is power, and that power shouldn’t only be available to those who can afford to pay. That’s why we keep our work free. Millions rely on Vox’s clear, high-quality journalism to understand the forces shaping today’s world. Support our mission and help keep Vox free for all by making a financial contribution to Vox today.

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In Politics

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Trump’s “moderation” on abortion is a lie

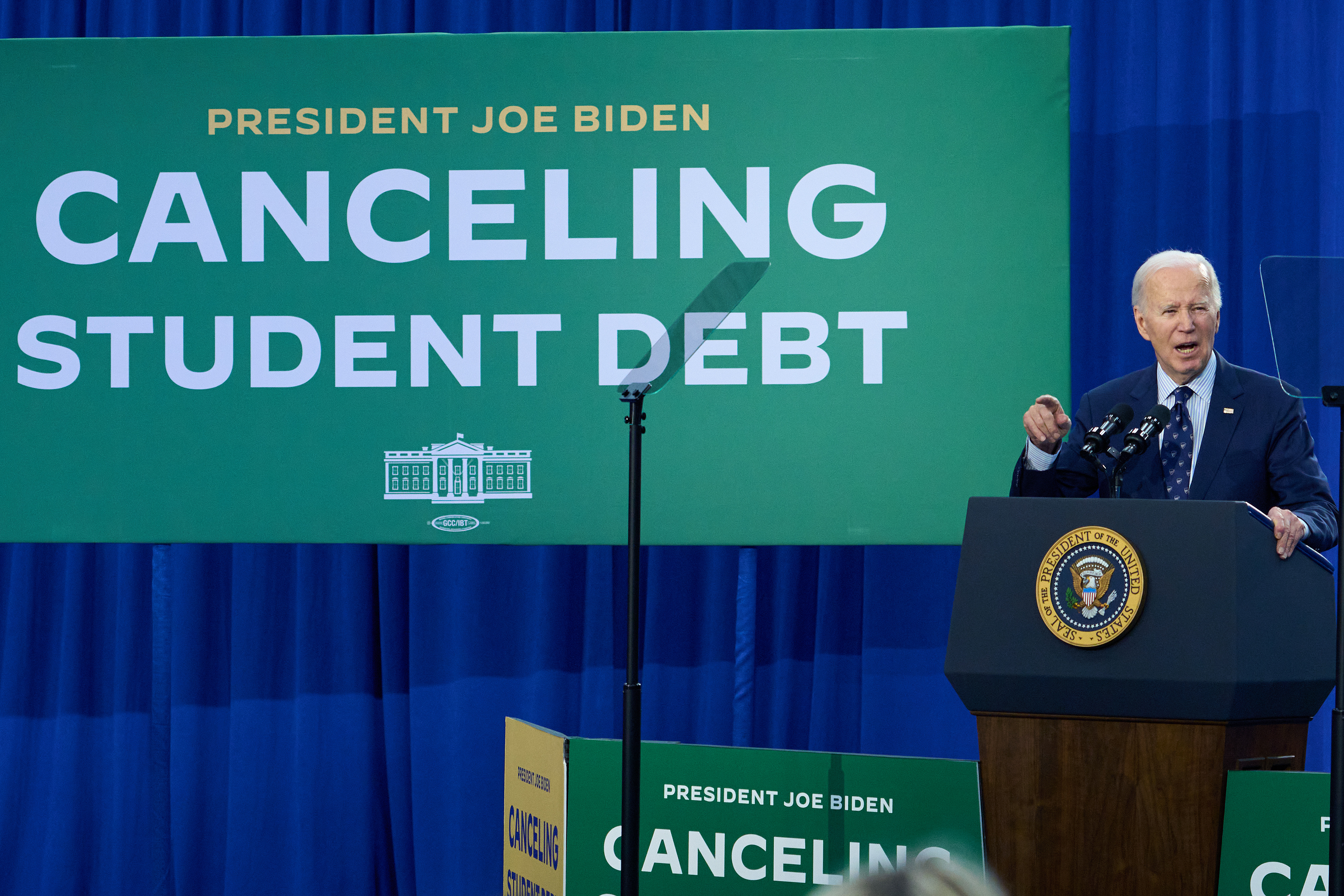

Biden’s newest student loan forgiveness plan, explained

Trump may sound moderate on abortion. The groups setting his agenda definitely aren’t.

The lies that sell fast fashion

The terrifying and awesome power of solar eclipses

When is the next total solar eclipse?

Age 21 Minimum Legal Drinking Age

A minimum legal drinking age (mlda) of 21 saves lives and protects health.

Minimum Legal Drinking Age (MLDA) laws specify the legal age when an individual can purchase alcoholic beverages. The MLDA in the United States is 21 years. However, prior to the enactment of the National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984, the legal age when alcohol could be purchased varied from state to state. 1

An age 21 MLDA is recommended by the:

• American Academy of Pediatrics 2 • Community Preventive Services Task Force 4 • Mothers Against Drunk Driving 5 • National Highway Traffic Safety Administration 1 • National Prevention Council 8 • National Academy of Sciences (National Research Council and Institute of Medicine) 9

The age 21 MLDA saves lives and improves health. 3

Fewer motor vehicle crashes

- States that increased the legal drinking age to 21 saw a 16% median decline in motor vehicle crashes. 6

Decreased drinking

- After all states adopted an age 21 MLDA, drinking during the previous month among persons aged 18 to 20 years declined from 59% in 1985 to 40% in 1991. 7

- Drinking among people aged 21 to 25 also declined significantly when states adopted the age 21 MLDA, from 70% in 1985 to 56% in 1991. 7

Other outcomes

- There is also evidence that the age 21 MLDA protects drinkers from alcohol and other drug dependence, adverse birth outcomes, and suicide and homicide. 4

Drinking by those under the age 21 is a public health problem.

- Excessive drinking contributes to about 4,000 deaths among people below the age of 21 in the U.S. each year. 10

- Underage drinking cost the U.S. economy $24 billion in 2010. 11

Drinking by those below the age of 21 is also strongly linked with 9,12,13 :

- Death from alcohol poisoning.

- Unintentional injuries, such as car crashes, falls, burns, and drowning.

- Suicide and violence, such as fighting and sexual assault.

- Changes in brain development.

- School performance problems, such as higher absenteeism and poor or failing grades.

- Alcohol dependence later in life.

- Other risk behaviors such as smoking, drug misuse, and risky sexual behaviors.

Alcohol-impaired driving

Drinking by those below the age of 21 is strongly associated with alcohol-impaired driving. The 2021 Youth Risk Behavior Survey 14 found that among high school students, during the past 30 days

- 5% drove after drinking alcohol.

- 14% rode with a driver who had been drinking alcohol.

Rates of drinking and binge drinking among those under 21

The 2021 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System found that among high school students, 23% drank alcohol and 11% binge drank during the past 30 days. 14

In 2021, the Monitoring the Future Survey reported that 6% of 8th graders and 28% of 12th graders drank alcohol during the past 30 days, and 2% of 8th graders and 13% of 12th graders binge drank during the past 2 weeks. 15

In 2014, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and the New York State Liquor Authority found that more than half (58%) of the licensed alcohol retailers in the City sold alcohol to underage decoys. 17

Enforcing the age 21 MLDA

Communities can enhance the effectiveness of age 21 MLDA laws by actively enforcing them.

- A Community Guide review found that enhanced enforcement of laws prohibiting alcohol sales to minors reduced the ability of youthful-looking decoys to purchase alcoholic beverages by a median of 42%. 16

- Alcohol sales to minors are still a common problem in communities.

More information on underage drinking

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Determine Why There Are Fewer Young Alcohol Impaired Drivers External . Washington, DC. 2001.

- Committee on Substance Abuse, Kokotailo PK. Alcohol use by youth and adolescents: a pediatric concern External . Pediatrics . 2010;125(5):1078-1087.

- DeJong W, Blanchette J. Case closed: research evidence on the positive public health impact of the age 21 minimum legal drinking age in the United States External . J Stud Alcohol Drugs . 2014;75 Suppl 17:108-115.

- Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Recommendations to reduce injuries to motor vehicle occupants: increasing child safety seat use, increasing safety belt use, and reducing alcohol-impaired driving Cdc-pdf External [PDF-78 KB]. Am J Prev Med . 2001;21(4 Suppl):16-22.

- Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD). Why 21? 2018; https://www.madd.org/the-solution/teen-drinking-prevention/why-21/ External . Accessed May 3, 2018.

- Shults RA, Elder RW, Sleet DA, et al. Reviews of evidence regarding interventions to reduce alcohol-impaired driving Cdc-pdf External [PDF-2 MB]. Am J Prev Med . 2001;21(4 Suppl):66-88.

- Serdula MK, Brewer RD, Gillespie C, Denny CH, Mokdad A. Trends in alcohol use and binge drinking, 1985-1999: results of a multi-state survey External . Am J Prev Med . 2004;26(4):294-298

- National Prevention Council. National Prevention Strategy: Preventing Drug Abuse and Excessive Alcohol Use [PDF-4.7MB]. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General; 2011.

- Bonnie RJ and O’Connell ME, editors. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Reducing Underage Drinking: A Collective Responsibility External . Committee on Developing a Strategy to Reduce and Prevent Underage Drinking. Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Alcohol-Related Disease Impact (ARDI) Application website . Accessed February 29, 2024.

- Sacks JJ, Gonzales KR, Bouchery EE, Tomedi LE, Brewer RD. 2010 national and state costs of excessive alcohol consumption External . Am J Prev Med . 2015;49(5):e73-79.

- Miller JW, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Jones SE. Binge drinking and associated health risk behaviors among high school students External . Pediatrics . 2007;119(1):76-85.

- Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General’s call to action to prevent and reduce underage drinking External . Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General;2007.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2021 Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data . Accessed on September 13, 2023.

- Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2021: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use external icon . Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2023.

- Elder R, Lawrence B, Janes G, et al. Enhanced enforcement of laws prohibiting sale of alcohol to minors: systematic review of effectiveness for reducing sales and underage drinking External [PDF-4MB]. Transportation Research E-Circular . 2007;E-C123:181-188.

- The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Alcohol & Health website . Accessed October 18, 2016.

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

- CDC Alcohol Portal

- Binge Drinking

- Check Your Drinking

- Drinking & Driving

- Underage Drinking

- Alcohol & Pregnancy

- Alcohol & Cancer

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Footprints to Recovery

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- Addiction Support Groups

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy

- EMDR Therapy

- Family Therapy

- Group Therapy

- Marriage and Couples Counseling

- Motivational Interviewing

- Sand Tray Therapy

- Seeking Safety Therapy

- Depression Treatment

- Treatment for Generalized Anxiety

- Social Anxiety Treatment

- Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Treatment

- Panic Disorder Treatment

- Borderline Personality Disorder Treatment

- Treatment for Trauma & Stress

- Biosound Therapy

- Neurofeedback

- Medication-Assisted Treatment Services

- Case Management Services

- Medical Detox

- Residential Addiction

- Partial Hospitalization

- Intensive Outpatient

- Outpatient Rehab

- Sober Living & Recovery Homes

- Alumni Community

- Sample Treatment Schedules

- Verify Your Insurance

- Payment Options

- What to Bring

- Prescription Drugs

- Health Concerns of Use

- Risks of Alcohol Abuse

- Risks of Overdose

- Withdrawal Symptoms

- Mixing Drugs or Alcohol

- Drug Processing Timelines

- Demographic Statistics

- For Industry Professionals

- Our Leadership

- View Testimonials

- Join Our Team

Raising the Drinking Age to 25: What Are the Pros and Cons?

- Medically Reviewed by David Szarka, MA, LCADC

There’s been an ongoing debate about the minimum legal drinking age (MLDA) in the U.S. since the National Minimum Drinking Age Act was passed in 1984. The federal law requires people be 21 years old to buy or possess alcohol . Some people feel that requiring people to be 21 to drink just makes underage drinking more of a problem and doesn’t align with other minimum age restrictions like joining the military or owning a gun. On the other side of the debate, people argue that young adults are less likely to drink responsibly, and that alcohol can damage the still-developing human brain. Some proponents of drinking age limits feel that the U.S. should raise the drinking age even higher — to 25.

Pros of Raising the Drinking Age to 25

Some people believe raising the legal drinking age to 25 is imperative because of considerations like emotional and physical maturity. They also say the minimum drinking age saves lives by reducing the risk of danger to oneself and others. Here are a few reasons why they believe the legal drinking age should be raised to 25:

Protects Brain Development

Much research has shown the damaging effects of alcohol on brain development in teens and young adults. The brain is still undergoing crucial developments until age 25, and some scientists have found evidence that it keeps developing until as late as age 30. Young adult and teen drinking can interfere with brain development, causing long-term consequences like :

- Damage to the hippocampus resulting in issues with memory and learning.

- Damage the prefrontal cortex, which can impair judgement and impulsivity in adulthood.

- Damage to the brain’s white matter, negatively impacting brain cells’ communication with each other.

- Greater risk for conditions like mood disorders, ADHD, PTSD, and other mental health challenges.

Prevents Drunk Driving Fatalities

There is a strong correlation between drunk driving and youth. Data shows that since the drinking age was raised to 21, there has been a significant decrease in alcohol-related car accidents. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimates that raising the drinking age to 21 saved 31,959 lives between 1975 and 2017. Furthermore, some research has shown that people aged 21-25 are the most likely age group to drive after drinking alcohol.

Decreases Underage Drinking

According to the Center for Disease Control (CDC), after the drinking age was raised to 21, alcohol consumption in people aged 18 to 20 decreased from 59% to 40% in the six years following the change. Drinking also decreased from 70% to 56% during the same period in people aged 21 to 25.

Lowers Addiction Risk

Some research suggests that around 90% of adults with substance use disorders drank as teens or young adults. Proponents argue that raising the drinking age can help stem the addiction epidemic in the U.S.

Cons of Raising the Drinking Age to 25

People who don’t think the drinking age should be raised and should potentially be lowered feel this way for a number of reasons. Some believe it’s a form of ageism, actually encourages underage drinking, and may put lives at risk because underage drinkers may be worried about reporting emergencies.

Raises the Thrill of Underage Drinking

Having a rebellious streak is part of the teenage years and sometimes continues into young adulthood. Youth are trying to develop their sense of self, and this often means pulling away from parents and questioning other authority figures. It’s a normal part of growing up. The parts of the brain responsible for impulsivity and decision-making are still under construction. This combination can fuel underage drinking. Critics of raising the drinking age argue that this change will just extend that “thrill” of asserting your independence against authority for a longer period given that we know that the brain continues developing well into the 20s.

Discourages People to Get Help in Emergencies

Some people believe lowering the drinking age can prevent medical emergencies and dangerous situations from becoming worse or deadly. They maintain that people who are drinking illegally may not call 911 if a friend is in trouble or an accident has happened because of drinking for fear of getting in trouble with the law or with their families. Many may not know that most states have laws in place that protect them from legal ramifications if they report an emergency.

Doesn’t Align With Other Age Restrictions

The United States is one of a handful of countries with a drinking age of 21. Proponents of keeping the drinking age at 21 or lowering the drinking age even more argue that European countries don’t have the same underage drinking problems as the U.S. They say that because people can drink legally at a younger age, it takes the allure of “breaking the rules” through alcohol consumption and so less youth drink. However, recent data shows that this is simply not the case. Around 50% of European countries have higher intoxication rates among teens and young adults, and also have similar binge drinking patterns.

Proponents of keeping drinking age limits at 21 or lowering the drinking age say that the law is counterintuitive to other minimum age laws. They point to the fact that people can own a gun, join the military, vote, and be convicted of a crime as an adult at age 18, so not allowing people to drink until age 21 is a form of ageism.

The Truth About Alcohol

Whatever side you’re on in the debate about minimum drinking age, the truth is that alcohol can be dangerous and deadly at any age. When alcohol use progresses to alcohol addiction it takes over your life. If you’re worried about your drinking or that of a loved one, reach out to Footprints to Recovery. We provided evidence-based substance abuse treatment that will help you take back your life.

- https://alcoholpolicy.niaaa.nih.gov/the-1984-national-minimum-drinking-age-act

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2020.00298/full

- https://www.menshealth.com/health/a26868313/when-does-your-brain-fully-mature/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7183385/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24565317/

- https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/ViewPublication/812753

- https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/report_2688/ShortReport-2688.html

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22525104/

- https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/fact-sheets/minimum-legal-drinking-age.htm

- https://www.mdt.mt.gov/visionzero/docs/taskforces/ojjdp_feb01.pdf

- How we can help

- Programs and locations

- Payment options

Check Insurance

Text for help, get a callback, related topics, what are delirium tremens symptoms, what is the pink cloud, what is a 12 step program for addiction, gray area drinking: is it a problem for you, questions about treatment options.

Our admissions team is available 24/7 to listen to your story and help you get started with the next steps.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

The Minimum Legal Drinking Age and Public Health

In summer 2008, more than 100 college presidents and other higher education officials signed the Amethyst Initiative, which calls for a reexamination of the minimum legal drinking age in the United States. The current age-21 limit in the United States is higher than in Canada (18 or 19, depending on the province), Mexico (18), and most western European countries (typically 16 or 18). A central argument of the Amethyst Initiative is that the U.S. minimum legal drinking age policy results in more dangerous drinking than would occur if the legal drinking age were lower. A companion organization called Choose Responsibility—led in part by Amethyst Initiative founder John McCardell, former Middlebury College president—explicitly proposes “a series of changes that will allow 18–20 year-olds to purchase, possess and consume alcoholic beverages” (see 〈 http://www.choose responsibility.org/proposal/ 〉).

Fueled in part by the high-profile national media attention garnered by the Amethyst Initiative and Choose Responsibility, activists and policymakers in several states, including Kentucky, Wisconsin, South Carolina, Missouri, South Dakota, Minnesota, and Vermont, have put forth various legislative proposals to lower their state's drinking age from 21 to 18, though no state has adopted a lower minimum legal drinking age yet.

Does the age-21 drinking limit in the United States reduce alcohol consumption by young adults and its harms, or as the signatories of the Amethyst Initiative contend, is it “not working”? Alcohol consumption and its harms are extremely common among young adults. According to results from the 2006–2007 National Health Interview Survey, adults age 18–25 report that on average they drank on 36 days in the previous year and typically consumed 5.1 drinks on the days they drank. If consumed at a single sitting, five drinks meets the clinical definition of “binge” or “heavy episodic” drinking. This consumption contributes to a substantial public health problem: five drinks for a 160-pound man with a limited time between drinks leads to a blood alcohol concentration of about 0.12 percent and results in moderate to severe impairments in coordination, concentration, reflexes, reaction time, depth perception, and peripheral vision. For comparison, the legal limit for driving in the United States is generally 0.08 percent blood alcohol content. Not surprisingly, motor vehicle accidents (the leading cause of death and injury in this age group), homicides, suicides, falls, and other accidents are all strongly associated with alcohol consumption ( Bonnie and O'Connell, 2004 ). Because around 80 percent of deaths among young adults are due to these “external” causes (as opposed to cancer, infectious disease, or other “internal” causes), policies that change the ways in and extent to which young people consume alcohol have the potential to affect the mortality rate of this population substantially.

In this paper, we summarize a large and compelling body of empirical evidence which shows that one of the central claims of the signatories of the Amethyst Initiative is incorrect: setting the minimum legal drinking age at 21 clearly reduces alcohol consumption and its major harms. However, this finding alone is not a sufficient justification for the current minimum legal drinking age, in part because it does not take into account the benefits of alcohol consumption. To put it another way, it is likely that restricting the alcohol consumption of people in their late 20s (or even older) would also reduce alcohol-related harms at least modestly. However, given the much lower rate at which adults in this age group experience alcohol-related harms, their utility from drinking likely outweighs the associated costs. Thus, when considering at what age to set the minimum legal drinking age, we need to determine if the reduction in alcohol-related harms justifies the reduction in consumer surplus that results from preventing people from consuming alcohol.

We begin this paper by examining the case for government intervention targeting the alcohol consumption of young adults. We develop an analytic framework to identify the parameters that are required to compare candidate ages at which to set the minimum legal drinking age. Next, we discuss the challenges inherent in estimating the effects of the minimum legal drinking age and describe what we believe are the two most compelling approaches to address these challenges: a panel fixed-effects approach and a regression discontinuity approach. We present estimates of the effect of the minimum legal drinking age on mortality from these two designs, and we also discuss what is known about the relationship between the minimum legal drinking age and other adverse outcomes such as nonfatal injury and crime. We then document the effect of the minimum legal drinking age on alcohol consumption, which lets us estimate the costs of adverse alcohol-related events on a per-drink basis. Finally we return to the analytic framework and use it to determine what the empirical evidence suggests is the correct age at which to set the minimum legal drinking age.

Economic Economic Considerations for Determining the Optimal Minimum Legal Drinking Age

Alcohol consumption by young adults results in numerous harms including deaths, injuries, commission of crime, criminal victimization, risky sexual behavior, and reduced workforce productivity. A substantial portion of these harms are either directly imposed on other individuals (as is the case with crime) or largely transferred to society as a whole through insurance markets as is the case with injuries ( Phelps, 1988 ). In addition, there is the theoretical possibility (supported by laboratory evidence) that youths may discount future utility too heavily, underestimate the future harm of their current behavior, and/or mispredict how they will feel about their choices in the future ( O'Donoghue and Rabin, 2001 ). If this is the case, even risks that are borne directly by the drinker are not being fully taken into account when an individual is deciding how much alcohol to consume. Given that young adults are imposing costs on others and probably not fully taking into account their own cost of alcohol consumption, there is a case for government intervention targeting their alcohol consumption. The minimum legal drinking age represents one approach to reducing drinking by young adults. 1

Determining the optimal age at which to set the minimum legal drinking age requires estimates of the loss in consumer surplus that results from reducing peoples' alcohol consumption. It also requires estimating the benefits to the drinker and to others from reducing alcohol-related harms. Unfortunately, it is not possible to obtain credible estimates of these key parameters at every point in the age distribution. First, there are no credible estimates of the effects of drinking ages lower than 18 or higher than 21 because the minimum legal drinking age has not been set outside this range in a signififi cant portion of the United States since the 1930s, and the countries with current drinking ages outside this range look very different from the United States. In fact, as we describe in detail in the next section, even estimating the effects on adverse outcomes of a drinking age in the 18 to 21 range is challenging. Second, we lack good ways to estimate the consumer surplus loss that results from restricting drinking, a problem that has characterized the entire literature on optimal alcohol control and taxation (see Gruber, 2001 , for a general discussion).

Thus, rather than try to estimate the optimal age at which to set the minimum legal drinking age, we focus on an analysis that is more feasible and useful from a policy perspective. The drinking age in the United States is currently 21, and there is no push to raise it. If it is lowered, there are many reasons to believe it will most likely be lowered to 18. First, the primary effort by activists for a lower drinking age is to lower the age to 18, either on its own or in conjunction with other alcoholcontrol initiatives such as education programs. In fact, 18 was the most commonly chosen age among the states that adopted lower minimum legal drinking ages in the 1970s. Second, 18 is the age of majority for other important activities such as voting, military service, and serving on juries, thus making it a natural focal point (though notably many states set different minimum ages for a variety of other activities such as driving, consenting to sexual activity, gambling, and purchasing handguns). Finally, many other countries have set their minimum legal drinking age at 18.

Because a change in the drinking age is likely to involve lowering it from 21 to 18, we focus on estimating the effect of lowering the drinking age by this amount on alcohol consumption, costs borne by the drinker, and costs borne by other people. Alcohol consumption can result in harms through many different channels. The effects of age-based drinking restrictions on long-term harms are very hard to estimate so we focus on the major acute harms that result from alcohol consumption including: deaths, nonfatal injuries, and crime. We pay particular attention to the effect of the drinking age on mortality because mortality is well-measured, has been the outcome focused on by much of the previous research on this topic, and is arguably the most costly of alcohol-related harms. To avoid the difficulty of trying to estimate the increase in consumer surplus that results from allowing people to drink, we estimate how much drinking is likely to increase if the drinking age is lowered from 21 to 18 and compare this to the likely increase in harms to the drinker and to other people. This allows us to characterize the harms in terms of dollars per drink. Since we are missing some of the acute harms and all of the long-term harms of alcohol consumption, the estimates we present in this paper are lower bounds of the costs associated with each drink.

Adding how much the drinker paid for the drink to the cost per drink borne by the drinker yields a lower bound on how much a person would have to value the drink for its consumption to be the result of a fully informed and rational choice. The per-drink cost borne by people other than the drinker provides a lower bound on the externality cost. If the externality cost is large or if the total cost of a drink (costs imposed on others plus costs the drinker bears privately plus the the price of the drink itself) is larger than what we believe the value of the drink is to the person consuming it, then this would suggest that the higher drinking age is justified.

The Evaluation Problem in the Context of the Minimum Legal Drinking Age

Determining how the minimum legal drinking age affects alcohol consumption and its adverse consequences is challenging. An extensive public health literature documents the strong correlation between alcohol consumption and adverse events, but estimates from these studies are of limited value for determining whether the minimum legal drinking age should be set at 18, 21, or some other age. Their main limitation is that the correlation between alcohol consumption and adverse events is probably due in part to factors other than alcohol consumption, such as variation across individuals in their tolerance for risk. People with a high tolerance for risk may be more likely both to drink heavily and to put themselves in danger in other ways, such as driving recklessly, even when they are sober. If this is the case, then predictions based on these correlations of how much public policy might reduce the harms of alcohol consumption will be biased upwards. Moreover, estimates of the average relationship between alcohol consumption and harms in the population may not be informative about the effects of the minimum legal drinking age, which probably disproportionately reduces drinking among the most law-abiding members of the population. This suggests that direct estimates of the effect of the drinking age on alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harms are needed if we are to compare the effects of different drinking ages.

Estimating the effects of the minimum legal drinking age requires comparing the alcohol consumption patterns and adverse event rates of young adults subject to the law with a similar group of young adults not subject to it. Since all young adults under age 21 in the United States are subject to the minimum legal drinking age, difficult to find a reasonable comparison group for this population. Because of cultural differences and different legal regimes, young adults in countries where the drinking age is lower than 21 are unlikely to constitute a good comparison group.

However, researchers working on this issue have identified two plausible comparison groups for 18 to 21 year-olds subject to the minimum legal drinking age. The first is composed of young people who were born just a few years earlier in the the same state (and who thus grew up in very similar circumstances) but who faced a lower legal drinking age due to changes in state drinking age policies. In the 1970s, 39 states lowered their minimum legal drinking age to 18, 19, or 20. These drinking age reductions were followed by increases in motor vehicle fatalities, which were documented by numerous researchers at the time (for a review, see Wagenaar and Toomey, 2002 ). This evidence led states to reconsider their decisions and encouraged aged Congress to adopt the National Minimum Drinking Age Act of 1984, which required states to adopt a minimum drinking age of 21 or risk losing 10 percent of their federal highway funds. By 1990, every state had responded to the federal law by increasing its drinking age to 21. Thus, within the same state some youths were allowed to drink legally when they turned 18, while those born just a short time later had to wait until they turned 21. We use a fixed-effects panel approach to compare the alcohol consumption and adverse event rates of these two groups.

The second approach for identifying a credible comparison group is to consider a period when the minimum legal drinking age is 21 and compare people just under 21 who are still subject to the minimum legal drinking age with those just over 21 who can drink legally. These two groups of people are likely to be very similar, except that the slightly older group is not subject to the minimum legal drinking age. This approach is called a regression discontinuity design ( Thistlewaite and Campbell, 1960 ; Hahn, Todd, and Van der Klaauw, 2001 ). In the next two sections, we describe these two research designs in detail and how we use them to estimate the effects of the minimum legal drinking age on mortality.

Panel Estimates of the Effect of the Drinking Age on Mortality

The panel approach to estimating the effects of the minimum legal drinking age focuses on the changes in the drinking age that occurred in most states in the 1970s and 1980s. We begin by presenting graphical evidence in Figure 1 on the relationship between the drinking age and the incidence of fatal motor vehicle accidents. The data underlying the series in Figure 1 come from the Fatality Analysis Reporting System for 1975–1993 for the 39 states that lowered their drinking age during the 1970s and 1980s. In figure, we present the time series of deaths due to motor vehicle accidents among: 18–20 year-olds during nighttime (solid circles); 18–20 year-olds during daytime (dotted line with hollow squares); and 25–29 year-olds during nighttime (stars). The time series in the figure are centered on the month in which a state took its largest step towards raising its drinking age back to 21. The daytime/nighttime distinction is standard in the literature (for example, Ruhm, 1996 ; Dee, 1999 ) and is useful for understanding the effects of young adult alcohol consumption because the majority (67 percent) of fatal motor vehicle accidents occurring in the evening hours (defined here as between 8:00 p.m. and 5:59 a.m.) involve alcohol, while only about a quarter of fatal motor vehicle accidents occurring in the daytime hours involve alcohol.

Notes : This figure is estimated from the 39 states that lowered their drinking age to below 21 at some point in the 1970s or 1980s. A nighttime accident is one occurring between 8:00 p.m. and 5:59 a.m.; 67 percent of these accidents involved alcohol and 26 percent of daytime accidents involved alcohol. The figure is centered on the year a state took its largest step towards raising its drinking age back to 21.

We also plot the percent of 18–20 year-olds that can drink legally in the 39 states that experimented with a lower minimum legal drinking age. This line does not drop instantly from 100 to 0 percent because some states increased their drinking age from 18 to 19 and then from 19 to 21 a few years later, and other states allowed people who could drink legally when the drinking age was increased to continue drinking legally.

Figure 1 reveals that, in the seven years after the increase in the drinking age, there is a substantial reduction in deaths among 18–20 year-olds due to nighttime motor vehicle accidents and much smaller reductions in deaths of 18–20 year-olds due to daytime accidents and of 25–29 year-olds due to nighttime accidents. That the largest reduction in death rates occurs for the type of accident most likely to drop in response to an increase in the drinking age is consistent with the possibility that the increase in the drinking age reduced the motor vehicle fatality rates of 18–20 year-olds. However, the graphical evidence in favor of the hypothesis that increasing the drinking age reduced deaths is not fully compelling. First, the decline in deaths due to nighttime motor vehicle accidents among 18–20 year-olds is not as abrupt as the decline in the percent of this population that can drink legally. Second, as can be seen in the figure, the number of 18–20 year-olds that die in nighttime accidents was already declining before the drinking age was raised in most states. For this reason turn to a state-level panel data approach that allows us to adjust for trends and time-invariant differences across states and estimate the effect of the minimum legal drinking on mortality rates.

To obtain an estimate of the decline in mortality attributable to the drinking age, we implement a panel regression analysis of the following form:

where ( Y st ) is the number of motor vehicle fatalities per 100,000 person-years for one of four age groups: 15–17 year-olds, 18–20 year-olds (the group directly affected by changes in the drinking age), 21–24 year-olds, and 25–29 year-olds in state ( s ) in time period ( t ). For each age group, we separate daytime and nighttime motor vehicle fatality rates. As noted above, any effects of the minimum legal drinking age on motor vehicle fatalities should be primarily on evening accidents because they are much more likely to involve alcohol. The regressions include a dummy variable for each state (θ s ) to remove time-invariant differences between states and dummy variables for each year (μ t ) to absorb any atypical year-to-year variation. 2 In addition, the regression includes state-specific linear time trends (ψ st ). The inclusion of state-specific dummies in combination with the state-specific time trends mean that the regression will return estimates of how raising the drinking age changes the level of motor vehicle mortality in a typical state, while adjusting for any state-specific trends in outcomes that preceded the change in the drinking age. This approach lets us compare people born in the same state just a few years apart who became eligible to drink legally at different ages. The variable MLDA (an acronym derived from Minimum Legal Drinking Age) is the proportion of 18 to 20 year-olds that can legally drink beer in state s in time t , and the coefficient on this variable is our best estimate of the impact on mortality rates of lowering the drinking age from 21 to 18. 3 The regressions are weighted by the age-specific state-year population, and the standard errors clustered on state are presented in brackets below the parameter estimates ( Bertrand, Duflo, and Mullainathan, 2004 ).

The estimates of the effect of the minimum legal drinking age on mortality for the subgroups described above are presented in Table 1 and are consistent with a large body of previous research showing that the minimum legal drinking age has economically significant effects on the motor vehicle mortality rates of young adults (for example, Dee, 1999 ; Lovenheim and Slemrod, 2010 ; Wagenaar and Toomey, 2002 ). Specifically, we find that going from a regime in which no 18–20 year-olds are legally allowed to drink to one in which all 18–20 year-olds are allowed to drink results in 4.74 more fatal motor vehicle accidents in the evening per 100,000 18–20 year-olds annually. Relative to the base death rate for this age and time of day, this is a 17 percent effect (4.74/28.1 = 0.17), and it is statistically significant. The associated point estimate for daytime fatalities (the majority of which do not involve alcohol) among 18–20 year-olds is much smaller, both in absolute terms and as a proportion of the daytime fatality rate, and it is not statistically significant. In addition, the changes in evening fatalities among 15–17 year-olds and 25–29 year-olds (whose behaviors should not be directly affected by the drinking age changes) are not statistically significant, though the 95 percent confidence intervals around the point estimates for these groups cannot rule out meaningfully large proportional effects relative to the low average death rates for individuals in these age groups. Overall, these patterns are consistent with a causal effect of easier alcohol access on motor vehicle fatalities among the 18–20 year-old young adults whose drinking behaviors were directly targeted by the laws. However, the rate of motor vehicle fatalities in the evening for 21–24 year-olds also changes when the minimum legal drinking age changes. While the proportional effect size for 21–24 year-olds (2.61/23.2 = 0.1125, or about 11 percent) is substantially smaller than for 18–20 year-olds (17 percent), this approach does not have sufficient statistical power to reject that the two estimates are equal. The apparent effect of the minimum legal drinking age on fatalities among 21–24 year-olds could reflect the effects of other unobserved anti-drunk driving campaigns that were correlated with drinking-age changes and targeted at young adults, or it may reflect spillovers, as members of these two groups are likely to socialize.

Panel Estimates of the Effect of the Minimum Legal Drinking Age on Motor Vehicle Fatalities (deaths per 100,000)

Source: The mortality rates are estimated using data from the Fatal Accident Reporting System 1975–1993.

Notes: For the regression results presented in this table, the top number is the point estimate and its standard error is directly below in brackets. All the regressions include year fixed effects, and state-specific time trends. The regressions are weighted by the age-specific state-year population. The dependent variable in each regression is the motor vehicle fatality rate per 100,000 person years for a particular age group and time of day. A nighttime accident is one occurring between 8:00 p.m. and 5:59 a.m.; 67 percent of these accidents involve alcohol and 26 percent of daytime accidents involve alcohol. The independent variable in each regression is the proportion of 18–20 year-olds who can drink legally. The "Average mortality rate" is that from motor vehicle accidents for each particular age group and time of day.

In Table 2 , we present estimates of the effects of the minimum legal drinking age on a more comprehensive set of causes of death. The mortality rates for this part of the analysis are estimated from the National Vital Statistics death certificate records. Since these records are a census of deaths and include substantial detail on the cause of death, it is possible to examine causes of death other than motor vehicle accidents. We present estimates of the effects of the minimum legal drinking age on all-cause mortality in Table 2 using the same fixed-effects specification as in Table 1 . Specifically, the dependent variable in each regression in the bold row of Table 2 is the death rate of 18–20 year-olds per 100,000 person-years estimated from the death certificate records. All models in Table 2 include state fixed effects, year fixed effects, and linear state-specific time trends. To increase the precision of the estimates, the regression are weighted by the size of the relevant population in that state and time period.

Panel Estimates of the Effect of the Minimum Legal Drinking Age on Mortality Rates (deaths per 100,000)

Notes: Each of the estimates presented above is from a separate regression, and its standard error is presented directly below it in brackets. The dependent variable in each regression is the mortality rate per 100,000 person years for a particular age group and cause of death. The independent variable of interest is the proportion of 18–20 year-olds that can drink legally. The regressions are weighted by the age-specific state-year population. All regressions have year fixed effects, state fixed effects, and state-specific time trends. The mortality rates are estimated from death certificate records for the 1975–1993 period. Deaths are categorized according to the primary cause of death on the death certificate.

The first estimate for all-cause mortality in Table 2 suggests that when all 18–20 year-olds are allowed to drink, there are 7.8 more deaths of 18–20 year-olds per 100,000 person-years (on a base of 113 deaths) than when no 18–20 year-olds are allowed to drink. This estimate is not statistically significant at conventional levels. Though the table reveals no evidence of a statistically significant increase in deaths due to internal causes (like cancer), it does reveal statistically significant increases in deaths due to motor vehicle accidents (4.15 more deaths on a base of 45.5 deaths, or a 4.15/45.5 = 0.091, or a 9.1 percent effect). This does not exactly match the estimate from Table 1 because the Vital Statistics records do not include the time of day when the accident occurred, so we are unable to split the rates based on the time of the accident as we did with the earlier data. 4 Table 2 also shows that increasing the share of young adults legal to drink leads to a statistically significant 10 percent increase in suicides (1.29/12.8 = 0.10), which is consistent with work by Birckmayer and Hemenway (1999) and Carpenter (2004b) . There is no evidence of statistically significant effects on the other causes of death for 18–20 year-olds. The lack of a discernable impact on deaths directly due to alcohol is surprising, though in this period deaths due to alcohol overdoses appear to have been significantly undercounted ( Hanzlick, 1988 ).

In the remainder of Table 2 , we present estimates of the relationship between the proportion of 18–20 year-olds that can drink legally and the mortality rates of three age groups: 15–17, 21–24, and 25–29 year-olds. Since the proportion of 18–20 year-olds that can drink should not directly affect these groups (except possibly through spillovers), these groups should experience at most modest increases in mortality rates. As can be seen in the table, with the exception of 21–24 year-olds there is no evidence of statistically significant changes in the mortality rates of the three age groups surrounding 18–20 year-olds. This suggests that the changes in mortality rates of 18–20 year-olds are probably not being driven by safety initiatives that may have been implemented at the same time the drinking age was increased as these would have affected the other age groups also. Overall, the patterns in Tables 1 and and2 2 suggest that easing access to alcohol increases the overall death rate of 18–20 year-olds due to increases in two of the leading causes of death for this age group: motor vehicle accidents and suicides.

Regression Discontinuity Estimates of the Effect of the Drinking Age on Mortality

Our other main strategy for identifying a plausible comparison group for people subject to the minimum legal drinking age is to take advantage of the fact that the drinking age “turns off” suddenly when a person turns 21. People slightly younger than 21 are subject to the drinking age law while those slightly older than 21 are not, but otherwise the two groups have very similar characteristics. If nothing other than the legal regime changes discretely at age 21, then a discrete mortality rates at age 21 can plausibly be attributed to the drinking age.

Again, we begin with the graphical approach by presenting the age profile of mortality rates for 19–22 year-olds in Figure 2 . This figure is estimated using Vital Statistics mortality records from 1997–2003. The age profiles are death rates per 100,000 person-years for motor vehicle accidents (dark circles), suicides (cross hatches), and deaths due to internal causes (open squares), by month of age. A best-fit line for ages 19–20 shows a decreasing trend in motor vehicle fatalities. Similarly a best-fit line from age 21 to 22 shows a decreasing trend. However, the two trends show clear evidence of a discontinuity at age 21, when drinking alcohol becomes legal. The visual evidence of an effect of the minimum legal drinking age in the regression discontinuity setting in Figure 2 for motor vehicle accidents is notably stronger than the associated evidence from the annual time-series trends in Figure 1 . There is also evidence of an increase in deaths due to suicide at age 21. In contrast, as can be seen in Figure 2 , there is little evidence of a discontinuous change in deaths due to internal causes at the minimum legal drinking age of 21.

Notes : The death rates are estimated by combining the National Vital Statistics records with population estimates from the U.S. Census.

To estimate the size of the discrete jumps in the outcomes we observe in Figure 2 , we estimate the following regression:

where y is the age-specific mortality rate. MLDA is a dummy variable that takes on a value of 1 for observations 21 and older, and 0 otherwise. The regressions include a quadratic polynomial in age, f( age ), fully interacted with the MLDA dummy. This serves to adjust for age-related changes in outcomes and, as seen in Figure 2 , is sufficiently flexible to fit the age profile of death rates. The Birthday variable is a dummy variable for the month in which the decedent's 21 st birthday falls and is intended to absorb the pronounced effect of birthday celebrations on mortality rates. We have recentered the age variable to take the value zero at age 21. As a result the parameter of interest in this model is β 1 , which measures the size of the discrete increase in mortality that occurs when people turn 21 and are no longer subject to the minimum legal drinking age. The parameter β 1 has the same interpretation as the parameter α from the panel models: it is the effect of going from no one in a population being allowed to drink legally to everyone in a population being allowed to drink legally.

We present regression estimates of the paramete β 1 in Table 3 . The regressions are estimated using mortality rates for the 48 months between ages 19 and 22. As with the state-year panel evidence in Table 2 , we estimate the effect of the minimum legal drinking age on the overall death rate as well as deaths due to various causes. The results in Table 3 are consistent with the graphical evidence and reveal a statistically significant 8.7 percent increase in overall mortality when people turn 21 (8.06 additional deaths per 100,000 person-years from a base of 93.07 deaths corresponds to 8.06/93.07 = 0.087, or an 8.7 percent increase). 5 The increase in overall mortality at age 21 is almost entirely attributable to external causes of mortality. We estimate that deaths due to internal causes increase by just 3.3 percent at age 21 (0.66/20.07 = 0.033), and this estimate is not statistically significant. Among the various external causes of death, deaths due to suicide increase discretely by a statistically significant 20.3 percent at age 21 (2.37/11.7 = 0.203), and motor vehicle mortality rates increase by 12.2 percent (3.65/29.81 = 0.122). We find no statistically significant change in homicide deaths at age 21. Deaths coded as due to alcohol (including some non-vehicular accidents where alcohol is mentioned on the death certificate) increase by about 0.41 deaths at age 21 (a very large effect given the average death rate from alcohol overdose of just 0.99 per 100,000). Overall, the visual evidence in Figure 2 and the corresponding regression estimates in Table 3 provide persuasive evidence that the minimum legal drinking age has a significant effect on mortality from suicides, motor vehicle accidents, and alcohol overdoses at age 21.

Regression Discontinuity Estimates of the Effect of the Minimum Legal Drinking Age on Mortality Rates (deaths per 100,000)

Notes: In the table above, we present estimates of the discrete increase in mortality rates that occurs at age 21 with the associated standard error directly below in brackets. The regression estimates are from a second-order polynomial in age fully interacted with an indicator variable for being over age 21. All models also include an indicator variable for the month the 21 st birthday falls in. Since the age variable has been recentered at 21, the estimate of the parameter on the indicator variable for being over 21, which we present in the table, is a measure of the discrete increase in mortality rates that occurs after people turn 21 and can drink legally. The mortality rates are estimated from death certificates and are per 100,000 person-years. The fitted values from this regression are superimposed over the means in Figure 2 . The mortality rates presented below the standard errors are the rates for people just under 21. Deaths are catgorized slightly differently than for Table 2 . Whereas Table 2 focused on the primary cause of death listed on the death certificate, Table 3 considers all factors mentioned on the death certificate and imposes the following precedence order: homicide, suicide, motor vehicle accident, alcohol, other external, internal.

Effects of the Drinking Age on Nonfatal Injury and Crime

In addition to premature death, alcohol use has been implicated in other adverse events such as nonfatal injury and crime. 6 Surprisingly, however, there is very little research directly linking the minimum legal drinking age to nonfatal injury. This is due, in part, to the lack of precise age-specific measures of injury rates during the 1970s and 1980s, which makes it impossible to estimate the effects of the minimum legal drinking age with precision using the panel approach. In ongoing work, however, we have used the regression discontinuity approach to estimate the effects of the minimum legal drinking age on nonfatal injury rates using administrative data on emergency department visits and inpatient hospital stays ( Carpenter and Dobkin, 2010a ). Although injuries have lower costs per adverse event than deaths, accidents resulting in a nonfatal injury are much more common than fatal accidents. We find that rates of emergency department visits and inpatient hospital stays increase significantly at age 21, by 408 and 77 per 100,000 person-years, respectively. These increases in nonfatal injuries are substantially larger than the increase in death rates of 8 per 100,000 person-years documented in Table 3 . However, estimating the discrete increase in adverse events at age 21 in percentage terms reveals that emergency department visits are increasing by 1 percent, hospital stays by 3 percent, and deaths by 9 percent. This pattern holds even when we restrict the analysis to motor vehicle-related injuries and fatalities, which suggests that alcohol plays a disproportionate role in more serious injuries.

Another costly adverse outcome commonly linked to alcohol is crime, including nuisance, property, and violent crime: we provide a review in Carpenter and Dobkin (forthcoming). Since the pharmacological profile of alcohol includes both disinhibition and increased aggression, a causal effect of minimum legal drinking ages on crime rates is plausible. Three studies have examined the effects of drinking ages on crime. Two have used the state-year panel approach described above to test whether more permissive drinking ages increased arrests for youths age 18–20. Using data from the Uniform Crime Reports, Joksch and Jones (1993) show that states that raised their minimum drinking age reduced nuisance crimes, such as vandalism and disorderly conduct, significantly over the period 1980–1987; these results are confirmed and replicated in fixed-effects models estimated in Carpenter (2005a) . More recently, we have applied the regression discontinuity design design to evaluate the relationship between alcohol access and crime ( Carpenter and and Dobkin, 2010b ). Using data encompassing the universe of arrests in California from 2000–2006, we found an 11 percent increase in arrest rates exactly at age 21. These effects were concentrated among nuisance crimes and violent crimes. Of the crimes for which we find a statistically significant effect, the two with the most substantial social costs are assault and robbery (larceny with force or threat of force) which increase by 63 and 8 arrests per 100,000 person-years, respectively.

Much of the literature on the minimum legal drinking age and the social costs of alcohol has focused on mortality. The evidence on other adverse outcomes suggests that an exclusive focus on mortality will lead one to substantially under-estimate the protective value of the minimum legal drinking age.

Effect of the Drinking Age on Alcohol Consumption

Estimating how a lower minimum legal drinking age would affect alcohol consumption is difficult. In addition to all of the challenges confronting researchers trying to estimate the effect of the drinking age on adverse event rates, there is an additional problem of data quality. While most adverse events are well-measured, alcohol consumption is not. Specifically, surveys of drinking do not generally include objective biological markers of alcohol consumption (such as blood alcohol concentration). Self-reported measures of drinking participation and intensity are subject to underreporting on the order of 40–60 percent ( Rehm, 1998 ). An additional issue is that, despite the usual confidentiality assurances given by survey administrators, 18–20 year-olds probably underreport alcohol consumption even more than the typical survey respondent because it is illegal for them to drink. 7

Recognizing these concerns, we nonetheless present estimates of the effect of the minimum legal drinking age on alcohol consumption from both the panel fixed-effects approach,and the regression discontinuity approach. For the fifi xed-effects approach, we focus on alcohol consumption reported by high school seniors age 18 and over who were surveyed in the Monitoring the Future study between 1976 and 1993. We use the same panel fixed-effects approach used to examine mortality rates with added controls for individual demographic characteristics such as race and gender. We examine three measures of alcohol consumption: whether the person drank at all in the past month, whether the person drank heavily in the past two weeks (defined as five or more drinks consumed at a single sitting), and the number of times the person drank in the last month. The effect of the minimum legal drinking age on these measures of alcohol consumption as estimated using a panel fixed-effects approach are presented in the first three columns of Table 4 . The relevant independent variable in each of the first three columns is the proportion 18–20 year-olds legal to drink in the state. The results indicate that allowing 18–20 year-olds drink increases drinking participation by 6.1 percentage points, heavy episodic drinking by 3.4 percentage points, and instances of past month drinking by 17.4 percent (0.94/5.4 = 0.174). These results are similar to previous estimates of the effect of the minimum legal drinking age that used these same data and a similar approach ( Dee, 1999 ; Carpenter, Kloska, O'Malley, and Johnston, 2007 ; Miron and Tetelbaum, 2009 ).

The Effect of the Minimum Legal Drinking Age on Alcohol Consumption

Notes: The independent variable of interest for the regression results presented in the first three columns is the proportion of 18–20 year-olds who can drink legally. These regressions are estimated using responses of high school seniors age 18 and older at the time they completed the Monitoring the Future survey. The regressions include state fixed effects, year fixed effects, state-specific time trends, and dummies for male, Hispanic, black, or other race. The regressions are estimated using a sample of 121,279 high school students from 1976–2003. The estimates in the last three columns are regression discontinuity estimates of the discrete increase in each drinking behavior that occurs after people turn 21. These are estimated using responses of 16,107 19–22 year-olds in the 1997–2005 National Health Interview Survey. These regressions include a quadratic polynomial in age interacted with a dummy for being over 21 at the time of the interview and the following covariates: indicator variables for census region, race, gender, health insurance, employment status, 21 st birthday, 21 st birthday + 1 day, and looking for work. People can report their drinking for the last week, month, or year, and 71 percent reported on their drinking in the past week or month. All the regressions include population weights. Standard errors for the panel fixed-effects analysis are clustered on state and reported in brackets below the point estimates in the first three columns. Robust standard errors for the regression discontinuity analysis are reported in brackets below the point estimates in the last three columns.

We also estimated the effect of the minimum legal drinking age on alcohol consumption using the regression discontinuity design. Since this approach required detailed information on alcohol consumption for people very close to age 21, we used the National Health Interview Survey which includes questions on drinking participation heavy episodic drinking, and the number of days in the last month on which the person consumed alcohol. We estimated the effect of the minimum legal drinking age on these measures of alcohol consumption using a version of the regression discontinuity design used earlier enriched with controls for individual demographic characteristics such as gender, race, region, and employment status. The estimates of β 1 are reported in the last three columns of Table 4 . Given that the regression model includes a polynomial in age fully interacted with a dummy variable for being over 21 and that the age variable has been recentered at 21, these are estimates of the discrete change in drinking that occurs at exactly age 21. We find that the probability an individual reports having consumed 12 or more drinks in the past year increases at age 21 by about 6.1 percentage points, and the estimate is statistically significant. We find a 4.9 percentage point increase in the probability an individual reports heavy drinking (five or more drinks on a single day at least once in the previous year), and we estimate that the number of drinking days in the previous month increase by 19.6 percent (0.55/2.8 = 0.196) at age 21, though only the second of these estimates is statisically significant at the conventional level. These estimates are quite similar to the estimates from the panel approach and have also been replicated using other datasets including the California Health Interview Surveys ( Carpenter and Dobkin, 2010b ) and the National Surveys on Drug Use and Health ( SAMHSA/OAS, 2009 ).

Below, we require an estimate of the number of additional drinks consumed if the drinking age were lowered from 21 to 18, in order to appropriately scale the cost estimates on a per-drink basis. In Column 3 of Table 4 , with the panel design, we estimated that moving from a situation in which no 18–20 year-olds can drink legally to one in which all 18–20 year-olds can drink would increase the number of times a youth reported drinking in the past month by about 0.94 instances. In Column 6 of Table 4 , using the regression discontinuity design, we estimated that the minimum legal drinking age increases the number of days the individual drank in the past 30 by about 0.55 days. Assuming instances are similar to days, the average of these two estimates implies that the minimum legal drinking age reduces alcohol consumption by about 0.745 drinking days per month. To put this on the same scale as the adverse event estimates (which are per 100,000 personyears), we calculate 0.745 × 12(months) × 100,000(persons) = 894,000 drinking days averted per 100,000 person-years. Young adults consume about 5.1 drinks on average each time they drink, so 894,000 drinking days corresponds to about 4.56 million drinks.

How Credible are the Estimates of the Effects of the Minimum Legal Drinking Age?