- Bahasa Indonesia

- High contrast

- CHILDREN IN INDONESIA

- WHERE WE WORK

- PARTNER WITH US

- PRESS CENTRE

Search UNICEF

The challenges of home learning during the covid-19 pandemic, after their schools closed due to the pandemic, moreyna and joaquin are striving to study effectively from home..

- Available in:

At 7 A.M. one morning, Moreyna woke up with renewed enthusiasm. As she did every school day prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, she showered, had her breakfast, and put on her school uniform. She then asked her mother to take her to school in the hope that “everything had gone back to normal.”

But she learned soon enough that her school was still closed. She became morose.

“I don’t like it because I can’t see my friends and teachers,” she moaned.

It was then that Moreyna’s mother, Maria Morin, realized that her daughter needed all the help she could get. “I decided to help her study more often,” she said. “It was the only way to make this new reality more bearable for my daughter.”

The pandemic’s profound impact on education

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, Moreyna’s school was closed by the local government. Moreyna was one of the 62.5 million students across the country—from pre-primary to higher education—who had had no choice but to learn from home.

This unprecedented shift to home learning has had a profound impact on students, parents and teachers across Indonesia. It has also exposed the vast geographic and socio-economic inequalities across the nation, with students from poor backgrounds and students with disabilities most impacted.

UNICEF’s support for the government

Since the start of the pandemic, the Government of Indonesia has taken some timely steps to support learning from home. Among them was adapting e-learning applications of both the Ministry of Education and Culture* (MoE) and the Ministry of Religious Affairs and training teachers to use online learning platforms.

However, the biggest obstacle for students learning from home, especially those who are poor and live in remote areas, is lack of internet access and electronic devices. According to UNICEF Education Specialist Nugroho Warman, “Parents also have to focus on other obligations to support their family, which leaves them with less time to support their children.”

In response, the MoE launched an educational TV programme called Belajar dari Rumah (Learning from Home) aimed at children without access internet but with access to TV.** The programme, which covers pre-school and high school, runs from Monday to Friday and is broadcasted through the State Television Network TVRI. It also includes additional programmes for parents.

To help assess the effectiveness of Belajar dari Rumah , UNICEF has been conducting regular surveys among parents, teachers and children. The surveys are conducted through SMS to be able to reach areas with no internet access.

UNICEF is also assisting the MoE in developing offline learning materials and establishing guidelines for responding to COVID-19 at the provincial and district levels.

Challenges ahead

To further mitigate the effects of the pandemic, the government has entered into various strategic partnerships: among them with EdTech companies to provide free access to online learning platforms, and with telecommunications operations on free internet quotas for teachers and students.

Despite these efforts, however, the structural disparity remains. For many disadvantaged families, the gap is even widening. Some remote areas do not even have electricity, and assisting children with online learning has proven challenging to many parents, especially those of a certain age and educational level.

In some poor villages, children are not even learning from home because the economic tolls of the pandemic have forced their farmer parents to enlist their help in the fields.

To help address this imbalance, UNICEF seeks to continue its partnership with the government by developing and scaling-up programmes aimed at meeting the educational needs of children in remote areas. With your funding and support , these programmes can be rolled out and distributed more quickly and equitably.

It’s far from ideal, but it’s working

For relatively more fortunate children like Moreyna and Joaquin, 8, things are starting to look up.

Maria is certainly aware of the positive shift in her daughter’s behaviour. “Moreyna is much happier studying from home, now that I am regularly by her side,” she says, adding that soon her daughter will attend primary school.

Moreyna is also much more active around the house. Apart from baking, she and her brother have taken up a new hobby—dancing.

After a few months of home learning, Joaquin, 8, is also happier and more confident. “I can still connect with my teachers while studying at home,” he says. “If I have difficulties with my school assignments, I can reach out to them and ask for help.”

How You Can Help

Thanks to the generous contributions of individual donors, UNICEF has been able to work with schools, madrasas, teachers and government officials in the education and religious affairs sectors across Indonesia to help children like Moreyna and Joaquin learn effectively from home.

However, assuming most schools remain closed due to rising COVID-19 cases, not only will parents’ ability to help their children study from home be stretched, but children will also lose, on average, about a third of a year of learning. This loss will affect their capacity to earn in the future.

Given the existing geographical and socio-economic inequalities, scaling-up this support across the provinces requires resources and a sustained effort. For this we need your support.

If you want to help minimize the tolls the COVID-19 pandemic has on our children’s future and make sure they can reach their dreams, please consider donating to UNICEF . We very much appreciate your contribution.

* Now the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology.

** According to recent World Bank data, 95% of households in Indonesia own television sets.

Related topics

More to explore, getting children back to learning.

After massive learning loss, more children are returning to learning in South Sulawesi

New data indicates declining confidence in childhood vaccines of up to 44 percentage points in some countries during the COVID-19 pandemic

Working across Sectors to Provide a Safe Return to Learning

Learning outcomes transformed in South Sulawesi and Papua

Bringing quality vaccines closer to communities

New cold chain equipment donation helps strengthen the cold chain management system in West Sumatra

What the Covid-19 Pandemic Revealed About Remote School

The unplanned experiment provided clear lessons on the value—and limitations—of online learning. Are educators listening?

Katherine Reynolds Lewis, Undark Magazine

:focal(512x344:513x345)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/03/d6/03d60640-f6dd-4840-984d-22d3f18f1d73/gettyimages-1282746597.jpg)

The transition to online learning in the United States during the Covid-19 pandemic was, by many accounts, a failure. While there were some bright spots across the country, the transition was messy and uneven — countless teachers had neither the materials nor training they needed to effectively connect with students remotely, while many of those students were bored , isolated, and lacked the resources they needed to learn. The results were abysmal: low test scores, fewer children learning at grade level, increased inequity, and teacher burnout. With the public health crisis on top of deaths and job losses in many families, students experienced increases in depression, anxiety, and suicide risk.

Yet society very well may face new widespread calamities in the near future, from another pandemic to extreme weather, that will require a similarly quick shift to remote school. Success will hinge on big changes, from infrastructure to teacher training, several experts told Undark. “We absolutely need to invest in ways for schools to run continuously, to pick up where they left off. But man, it’s a tall order,” said Heather L. Schwartz, a senior policy researcher at RAND. “It’s not good enough for teachers to simply refer students to disconnected, stand-alone videos on, say, YouTube. Students need lessons that connect directly to what they were learning before school closed.”

More than three years after U.S. schools shifted to remote instruction on an emergency basis, the education sector is still largely unprepared for another long-term interruption of in-person school. The stakes are highest for those who need it most: low-income children and students of color, who are also most likely to be harmed in a future pandemic or live in communities most affected by climate change. But, given the abundance of research on what didn’t work during the pandemic, school leaders may have the opportunity to do things differently next time. Being ready would require strategic planning, rethinking the role of the teacher, and using new technology wisely, experts told Undark. And many problems with remote learning actually trace back not to technology, but to basic instructional quality. Effective remote learning won’t happen if schools aren’t already employing best practices in the physical classroom, such as creating a culture of learning from mistakes, empowering teachers to meet individual student needs, establishing high expectations, and setting clear goals supported by frequent feedback. While it’s ambitious to envision that every school district will create seamless virtual learning platforms — and, for that matter, overcome challenges in education more broadly — the lessons of the pandemic are there to be followed or ignored.

“We haven’t done anywhere near the amount of planning or the development of the instructional infrastructure needed to allow for a smooth transition next time schools need to close for prolonged periods of time,” Schwartz said. “Until we can reach that goal, I don’t have high confidence that the next prolonged school closure will be substantially more successful.”

Before the pandemic, only 3 percent of U.S. school districts offered virtual school, mostly for students with unique circumstances, such as a disability or those intensely pursuing a sport or the performing arts, according to a RAND survey Schwartz co-authored. For the most part, the educational technology companies and developers creating software for these schools promised to give students a personalized experience. But the research on these programs, which focused on virtual charter schools that only existed online, showed poor outcomes . Their students were a year behind in math and nearly a half-year behind in reading, and courses offered less direct time with a teacher each week than regular schools have in a day.

The pandemic sparked growth in stand-alone virtual academies, in addition to the emergency remote learning that districts had to adopt in March 2020. Educators’ interest in online instructional materials exploded, too, according to Schwartz, “and it really put the foot on the gas to ramp them up, expand them, and in theory, improve them.” By June 2021, the number of school districts with a stand-alone virtual school rose to 26 percent. Of the remaining districts, another 23 percent were interested in offering an online school, the report found.

But the sheer magnitude of options for online learning didn’t necessarily mean it worked well, Schwartz said: “It’s the quality part that has to come up in order for this to be a really good, viable alternative to in person instruction.” And individualized, self-directed online learning proved to be a pipe dream — especially for younger children who needed support from a parent or other family member even to get online, much less stay focused.

“The notion that students would have personalized playlists and could curate their own education was proven to be problematic on a couple levels, especially for younger and less affluent students,” said Thomas Toch, director of FutureEd, an education think tank at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy. “The social and emotional toll that isolation and those traumas took on students suggest that the social dimension of schooling is hugely important and was greatly undervalued, especially by proponents for an increased role of technology.”

Students also often didn’t have the materials they needed for online school, some lacking computers or internet access at home. Teachers didn’t have the right training for online instruction , which has a unique pedagogy and best practices. As a result, many virtual classrooms attempted to replicate the same lessons over video that would’ve been delivered at school. The results were overwhelmingly bad, research shows. For example, a 2022 study found six consistent themes about how the pandemic affected learning, including a lack of interaction between students and with teachers, and disproportionate harm to low-income students. Numb from isolation and too many hours in front of a screen, students failed to engage in coursework and suffered emotionally .

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/05/e1/05e16ea9-bd7f-4fbf-846e-177f05272f72/gettyimages-1229757662.jpg)

After some districts resumed in-person or hybrid instruction in the 2020 fall semester, it became clear that the longer students were remote, the worse their learning delays . For example, national standardized test scores for the 2020-2021 school year showed that passing rates for math declined about 14 percentage points on average, more than three times the drop seen in districts that returned to in-person instruction the earliest, according to a 2021 National Bureau of Economic Research study . Even after most U.S. districts resumed in-person instruction, students who had been online the longest continued to lag behind their peers. The pandemic hit cities hardest and the effects disproportionately harmed low-income children and students of color in urban areas.

“What we did during the pandemic is not the optimal use of online learning in education for the future,” said Ashley Jochim, a researcher at the Center on Reinventing Public Education at Arizona State University’s Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College. “Online learning is not a full stop substitute for what kids need to thrive and be supported at school.”

Children also largely prefer in-person school. A 2022 Pew Research Center survey suggested that 65 percent of students would rather be in a classroom, 9 percent would opt for online only, and the rest are unsure or prefer a hybrid model. “For most families and kids, full-time online school is actually not the educational solution they want,” Jochim said.

Virtual school felt meaningless to Abner Magdaleno, a 12th grader in Los Angeles. “I couldn’t really connect with it, because I’m more of, like, a social person. And that was stripped away from me when we went online,” recalled Magdaleno. Mackenzie Sheehy, 19, of Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, found there were too many distractions at home to learn. Her grades suffered, and she missed the one-on-one time with teachers. (Sheehy graduated from high school in 2022.)

Many teachers feel the same way. “Nothing replaces physical proximity, whatever the age,” said Ana Silva, a New York City English teacher. She enjoyed experimenting with interactive technology during online school, but is grateful to be back in person. “I like the casual way kids can come to my desk and see me. I like the dynamism — seeing kids in the cafeteria. Those interactions are really positive, and they were entirely missing during the online learning.”

During the 2022-2023 school year, many districts initially planned to continue online courses for snow days and other building closures. But they found that the teacher instruction, student experience, and demands on families were simply too different for in-person versus remote school, said Liz Kolb, an associate professor in the School of Education at the University of Michigan. “Schools are moving away from that because it’s too difficult to quickly transition and blend back and forth among the two without having strong structures in place,” Kolb said. “Most schools don’t have those strong structures.”

In addition, both families and educators grew sick of their screens. “They’re trying to avoid technology a little bit. There’s this fatigue coming out of remote learning and the pandemic,” said Mingyu Feng, a research director at WestEd, a nonprofit research agency. “If the students are on Zoom every day for like, six hours, that seems to be not quite right.”

Despite the bumpy pandemic rollout, online school can serve an important role in the U.S. education system. For one, online learning is a better alternative for some students. Garvey Mortley, 15, of Bethesda, Maryland, and her two sisters all switched to their district’s virtual academy during the pandemic to protect their own health and their grandmother’s. This year, Mortley’s sisters went back to in-person school, but she chose to stay online. “I love the flexibility about it,” she said, noting that some of her classmates prefer it because they have a disability or have demanding schedules. “I love how I can just roll out of bed in the morning, and I can sit down and do school.” Some educators also prefer teaching online, according to reports of virtual schools that were inundated with applications from teachers because they wanted to keep working from home . Silva, the New York high school English teacher, enjoys online tutoring and academic coaching, because it facilitates one-on-one interaction.

And in rural districts and those with low enrollment, some access to online learning ensures students can take courses that could otherwise be inaccessible. “Because of the economies of scale in small rural districts, they needed to tap into online and shared service delivery arrangements in order to provide a full complement of coursework at the high school level,” said Jochim. Innovation in these districts, she added, will accelerate: “We’ll continue to see growth, scalability, and improvement in quality.”

There were also some schools that were largely successful at switching to online at the start of the pandemic, such as Vista Unified School District in California, which pooled and shared innovative ideas for adapting in March 2020; the school quickly put together an online portal so that principals and teachers could share ideas and the district could allot the necessary resources. Digging into examples like this could point the way to the future of online learning, said Chelsea Waite, a senior researcher at the Center on Reinventing Public Education, who was part of a collaborative project studying 70 schools and districts that pivoted successfully to online learning. The project found three factors that made the transition work: a focus on resilience, collaboration, and autonomy for both students and educators; a healthy culture that prioritized relationships; and strong yet flexible systems that were accustomed to adaptation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/60/64/606453dd-d157-45da-a865-5161f95b6f08/gettyimages-1228656332.jpg)

“We investigated schools that did seem to be more prepared for the Covid disruption, not just with having devices in students’ hands or having an online curriculum already, but with a learning culture in the school that really prioritized agency and problem solving as skills for students and adults,” Waite said. “In these schools, kids are learning from a very young age to be a little bit more self-directed, to set goals, and pursue them and pivot when they need to.”

Similarly, many of the takeaways from the pandemic trace back to the basics of effective education, not technological innovation. A landmark report by the National Academies of Sciences called “How People Learn,” most recently updated in 2018, synthesized the body of educational research and identified four key features in the most successful learning environments. First, these schools are designed for, and adapt to, the specific students, building on what they bring to the classroom, such as skills and beliefs. Second, successful schools give their students clear goals, showing them what they need to learn and how they can get there. Third, they provide in-the-moment feedback that emphasizes understanding, not memorization. And finally, the most successful schools are community-centered, with a culture of collaboration and acceptance of mistakes.

“We as humans are social learners, yet some of the tech talk is driven by people who are strong individual learners,” said Jeremy Roschelle, executive director of Learning Sciences Research at Digital Promise, a global education nonprofit. “They’re not necessarily thinking about how most people learn, which is very social.”

Another powerful insight from pandemic-era remote schooling involves the evolving role of teachers, said Kim Kelly, a middle school math teacher at Northbridge Middle School in Massachusetts and a K-8 curriculum coach. Historically, a teacher’s role is the keeper of knowledge who delivers instruction. But in recent years, there has been a shift in approach, where teachers think of themselves as coaches who can intervene based on a student’s individual learning progress. Technology that assists with a coach-like role can be effective — but requires educators to be trained and comfortable interpreting data on student needs.

For example, with a digital learning platform called ASSISTments, teachers can assign math problems, students complete them — potentially receiving in-the-moment feedback on steps they’re getting wrong — and then the teachers can use data from individual students and the entire class to plan instruction and see where additional support is needed.

“A big advantage of these computer-driven products is they really try to diagnose where students are, and try to address their needs. It’s very personalized, individualized,” said WestEd’s Feng, who has evaluated ASSISTments and other educational technologies. She noted that some teachers feel frustrated “when you expect them to read the data and try to figure out what the students’ needs are.”

Teacher’s colleges don’t typically prepare educators to interpret data and change their practices, said Kelly, whose dissertation focused on self-regulated online learning. But professional development has helped her learn to harness technology to improve teaching and learning. “Schools are in data overload; we are oozing data from every direction, yet none of it is very actionable,” she said. Some technology, she added, provided student data that she could use regularly, which changed how she taught and assigned homework.

When students get feedback from the computer program during a homework session, the whole class doesn’t have to review the homework together, which can save time. Educators can move forward on instruction — or if they see areas of confusion, focus more on those topics. The ability of the programs to detect how well students are learning “is unreal,” said Kelly, “but it really does require teachers to be monitoring that data and interpreting.” She learned to accept that some students could drive their own learning and act on the feedback from homework, while others simply needed more teacher intervention. She now does more assessment at the beginning of a course to better support all students.

At the district or even national level, letting teachers play to their strengths can also help improve how their students learn, Toch, of FutureEd, said. For example, if a teacher is better at delivering instruction, they could give a lesson to a larger group of students online, while another teacher who is more comfortable in the coach role could work in smaller groups or one-on-one.

“One thing we saw during the pandemic are smart strategies for using technology to get outstanding teachers in front of more students,” Toch said, describing one effort that recruited exceptional teachers nationally and built a strong curriculum to be delivered online. “The local educators were providing support for their students in their classrooms.”

Remote schooling requires new technology, and already, educators are swamped with competing platforms and software choices — most of which have insufficient evidence of efficacy . Traditional independent research on specific technologies is sparse, Roschelle said. Post-pandemic, the field is so diverse and there are so many technologies in use, it’s almost impossible to find a control group to design a randomized control trial, he added. However, there is qualitative research and evidence that give hints about the quality of technology and online learning, such as case studies and school recommendations.

Educational leaders should ask three key questions about technology before investing, recommended Ryan Baker, a professor of education at the University of Pennsylvania: Is there evidence it works to improve learning outcomes? Does the vendor provide support and training, or are teachers on their own? And does it work with the same types of students as are in their school or district? In other words, educators must look at a technology’s track record in the context of their own school’s demographics, geography, culture, and challenges. These decisions are complicated by the small universe of researchers and evaluators, who have many overlapping relationships. (Over his career, for example, Baker has worked with or consulted for many of the education technology firms that create the software he studies.)

It may help to broaden the definition of evidence. The Center on Reinventing Public Education launched the Canopy project to collect examples of effective educational innovation around the U.S.

“What we wanted to do is build much better and more open and collective knowledge about where schools are challenging old assumptions and redesigning what school is and should be,” she added, noting that these educational leaders are reconceptualizing the skills they want students to attain. “They’re often trying to measure or communicate concepts that we don’t have great measurement tools for yet. So they end up relying on a lot of testimonials and evidence of student work.”

The moment is ripe for innovation in online and in-person education, said Julia Fallon, executive director of the State Educational Technology Directors Association, since the pandemic accelerated the rollout of devices and needed infrastructure. There’s an opportunity and need for technology that empowers teachers to improve learning outcomes and work more efficiently, said Roschelle. Online and hybrid learning are clearly here to stay — and likely will be called upon again during future temporary school closures.

Still, poorly-executed remote learning risks tainting the whole model; parents and students may be unlikely to give it a second chance. The pandemic showed the hard and fast limits on the potential for fully remote learning to be adopted broadly, for one, because in many communities, schools serve more than an educational function — they support children’s mental health, social needs, and nutrition and other physical health needs. The pandemic also highlighted the real challenge in training the entire U.S. teaching corps to be proficient in technology and data analysis. And the lack of a nimble shift to remote learning in an emergency will disproportionately harm low-income children and students of color. So the stakes are high for getting it right, experts told Undark, and summoning the political will.

“There are these benefits in online education, but there are also these real weaknesses we know from prior research and experience,” Jochim said. “So how do we build a system that has online learning as a complement to this other set of supports and experiences that kids benefit from?”

Katherine Reynolds Lewis is an award-winning journalist covering children, race, gender, disability, mental health, social justice, and science.

This article was originally published on Undark . Read the original article .

Get the latest stories in your inbox every weekday.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

How has the pandemic changed the way you’ll learn?

As students gradually return to campus, many universities will be offering blended learning – mixing face-to-face lectures with the best of digital teaching

- The 2022 league table

T he past year and a half has been a learning experience for everyone in education. You might recall frustrating days battling your internet connection to log on to Teams classes. Similarly, the pandemic has been a baptism of fire for universities in how to deliver quality online learning.

While universities are planning to revert to their pre-pandemic state by autumn 2022, many are also thinking hard about the positive lessons that can be drawn from what’s happened. The main shift is likely to be around how much online teaching you get. Most universities are planning to use a “blended model” that will combine the flexibility of online lectures with more interactive activities in-person, such as labs, seminars, workshops and Q&A sessions.

“The reference to some universities talking about ending face-to-face lectures doesn’t mean students won’t be attending any in-person classes; it means they’ll move away from large lectures of 200 students upwards. We’ll see a lot more of these sessions provided online because that can be far more effective,” explains Liz Barnes, the vice-chancellor of Staffordshire University who has led a review into online learning..

Some universities and courses are planning for more online learning than others, so when you’re choosing a university think about what might work for you. A broad rule of thumb is that practical courses have more face-to-face contact hours than academic degrees which involve lots of reading.

Ask yourself: are you planning to commute, and would you prefer to only be in for a couple of days per week, with the rest online? Or do you need in-person teaching to motivate you and to meet new people? Some universities are offering a variety of options to suit different learning styles and personal circumstances. Most university websites aren’t able to supply the full details of how individual courses will be taught, so to find out the number of face-to-face contact hours you should ask the universities directly – and ideally visit an open day, says Barnes. She adds that the next year is still going to be a transition phase out of the pandemic, so things may well change in 2022.

If you’re concerned about whether online teaching means you’re getting worse value for money, this is actually not the case, assures Prof Allison Littlejohn, an academic at UCL specialising in learning technology.

“The time needed to prepare and produce online teaching materials is much higher than for on-campus lectures,” she says. Instead, most universities are shifting lectures online as they think it’s a better way for their students to learn.

If you’re still worried about surviving Zoom lectures, there are some strategies that can help.

“Don’t watch an entire, hour-long Zoom lecture. If the lecture is pre-recorded, combine watching it with active reflection on what you’re learning. If the lecture is live, find ways to interact with other students and with academics afterwards to discuss ideas and concepts,” recommends Littlejohn.

Interaction is an essential component of well-designed online learning, she says, so if it’s not included, ask your tutor to build in more time with individual students or in small groups, online or in person. You can also organise your own study groups to discuss what you’ve learned in a Zoom lecture or do problem-solving activities using new ideas and concepts.

One thing you might be worrying about is whether your disrupted school experience could hold you back at university.

“You might have had a poor experience with digital learning or feel less prepared for the academic challenges and independence university brings. So find out what a university is doing to help you around digital skills and how they support students,” recommends Ian Dunn, deputy vice-chancellor at Coventry University.

“Think about your last year of study during the Covid-19 pandemic and what you need from a learning and teaching perspective to thrive.”

- Online learning

- University Guide 2022

- Universities

- Higher education

- University guide

Most viewed

- Frontiers in Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Research Topics

Learning in times of COVID-19: Students’, Families’, and Educators’ Perspectives

Total Downloads

Total Views and Downloads

About this Research Topic

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound and sudden impact on many areas of life; work, leisure time and family alike. These changes have also affected educational processes in formal and informal learning environments. Public institutions such as childcare settings, schools, universities and further ...

Keywords : COVID-19, distance learning, home learning, student-teacher relationships, digital teaching and learning, learning

Important Note : All contributions to this Research Topic must be within the scope of the section and journal to which they are submitted, as defined in their mission statements. Frontiers reserves the right to guide an out-of-scope manuscript to a more suitable section or journal at any stage of peer review.

Topic Editors

Topic coordinators, recent articles, submission deadlines.

Submission closed.

Participating Journals

Total views.

- Demographics

No records found

total views article views downloads topic views

Top countries

Top referring sites, about frontiers research topics.

With their unique mixes of varied contributions from Original Research to Review Articles, Research Topics unify the most influential researchers, the latest key findings and historical advances in a hot research area! Find out more on how to host your own Frontiers Research Topic or contribute to one as an author.

TheJakartaPost

Please Update your browser

Your browser is out of date, and may not be compatible with our website. A list of the most popular web browsers can be found below. Just click on the icons to get to the download page.

- Destinations

- Jakpost Guide to

- Newsletter New

- Mobile Apps

- Tenggara Strategics

- B/NDL Studios

- Archipelago

- Election 2024

- Regulations

- Asia & Pacific

- Middle East & Africa

- Entertainment

- Arts & Culture

- Environment

- Work it Right

- Quick Dispatch

- Longform Biz

Challenges of home learning during a pandemic through the eyes of a student

As a student participating in the home-learning program, online school was confusing to adjust to as we were not prepared through simulations or practices beforehand.

Share This Article

Change size.

The COVID-19 pandemic took the world by surprise.

Globally, everything has stopped. Projects have been delayed, workplaces closed and schools shut down. The world seems to have ground to a halt because of the novel coronavirus.

However, students continue their education through online learning and via video calls with their teachers, especially in big cities such as Jakarta. The model is currently the best alternative as keeping schools open poses a safety risk for students.

Globally, many countries have adopted this approach. Schools in New York, the United States, prepared for online learning by distributing gadgets to their students, ensuring they had access to learning materials. As of early April, education authorities distributed around 500,000 laptops and tablets to their students, allowing them to participate in classes online.

When the first two COVID-19 cases were announced in Indonesia in early March, the country was in a panic. On March 14, Jakarta Governor Anies Baswedan announced that all schools in Jakarta were to be closed. However, many schools were not ready to apply home learning programs yet. The online classes implemented in Indonesia work differently from those in the US. This is due to a lack of preparation in this country.

As a student participating in the home-learning program, online school was confusing to adjust to as we had not been prepared through simulations or practices beforehand. Students reported the home-learning program to be even more stressful than regular classrooms. Some of the common reasons for this went along the lines of: "Normal classes may have been difficult, but having friends makes it so much more manageable and less stressful. Online classes take out the benefits of having friends to socialize with and being stuck alone with nothing but assignments."

Many students participating in home-learning programs also say that the workload of online classes is larger than that of regular classes. The general consensus is that home-learning programs — although highly beneficial and a good alternative to school as schools are closed — still require some getting used to by students, as it is a novel concept and not many are experienced with them.

However, although the closing of schools does have a silver lining (home-learning programs where students are still able to learn), the true sufferers of the government order of school closings are the students in less fortunate situations and the students who are in schools that are not well-funded.

This is because those students lack the devices and internet access to be able to participate in online classes, and the schools do not have the capacity to teach online. Unlike in New York where devices are distributed to students by schools and private companies, in Indonesia, there is yet to be this kind of effort.

This leaves many students in a bad spot where they are unable to receive an education. Although internet service providers have been giving out free data packages, they are simply not capable of supporting video calls on programs such as Zoom.

To further complicate things, it seems that COVID-19 will last a while in Indonesia. For context, in China, it took months for the transmissions to stabilize — and this was with a fast government response, instant lockdown and people obeying the rules and quarantine policies.

Despite the lack of a nation-wide lockdown, schools remain closed, meaning that students who have no access to a device or internet connection will have a difficult time maintaining their education. Due to these factors, they will be in a very difficult spot educationally until the COVID-19 pandemic dies down in Indonesia. In this situation, the government should make extra efforts to support the education sector and build a sense of solidarity among schools, such as by facilitating networks between international and national/public schools to share experiences and study methodologies for online teaching.

Thankfully, there are now some alternatives to online learning in which students in less fortunate situations could participate. The Education and Culture Ministry recently introduced a Belajar di Rumah (Learning at Home) program through state-owned broadcaster TVRI (for the next three months) and a platform called Guru Berbagi (Teachers Sharing), providing creating learning and teaching materials. To add on to this, however, the government should still have more offline options for students without internet access, such as the distribution of books and learning materials.

Personally, I feel that online classes are a great alternative to normal in-school classes. As a 10 th grader participating in online classes right now, I have been able to focus more and perform better.

The presence of COVID-19 will directly and permanently change education in the future, seeing that we must be able to adapt to working and studying online for any kind of reasons and situations. I believe, both TVRI’s Belajar di Rumah program and the Guru Berbagi platform will leave a legacy and should be continued to support class teachings for good.

Only time will tell whether online classes will be a good substitute for normal classes, and if they are, there will be a rise in online educational programs and online universities. (kes)

Rarkryan is a 10 th -grade student at BINUS School Simprug

VinFast’s take on EV ownership: A worry-free future via innovative battery subscriptions

RI officials no idea about Bruneian firm's HSR proposal in Kalimantan

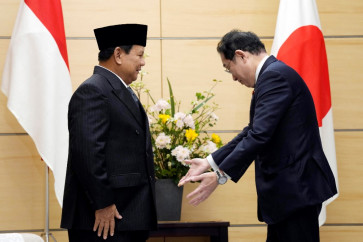

Prabowo talks security with Kishida

Related articles, covid lowered life expectancy by 1.6 years worldwide: study, supporting self-employment to solve female labor force participation problem, who chief warns pandemic accord hangs in the balance, solidarity clouds loom over global health threats as 2023 ends, amid lack of guidance, teachers chart own path to tackle online learning obstacles, related article, more in life.

The ever-evolving identity of Indonesia’s streetwear scene

An honest conversation: How storytelling can make a positive impact on yourself and others

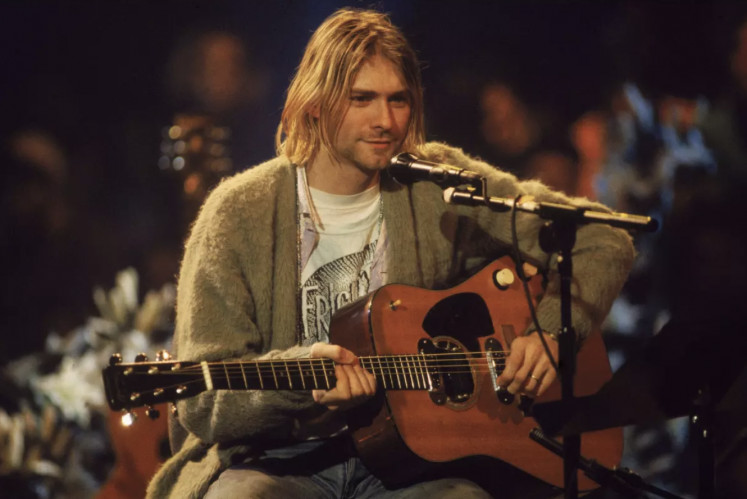

Kurt Cobain, style icon

Prabowo, Anwar discuss direction to strengthen Malaysia-Indonesia ties

Room for improvement

Prabowo signals stronger Japan ties after China visit

House recess suggests election inquiry plan dead on arrival, idx composite jumps 1.22% as market eyes us fed’s policy direction, starlink to begin network trials in nusantara in may, ministry urges public to remain calm as dengue cases, deaths soar, part of bocimi toll road collapses in landslide, jokowi cannot promise rice aid will last until december, mou opens way for indonesians to use qris in brunei, laos.

- Jakpost Guide To

- Art & Culture

- Today's Paper

- Southeast Asia

- Cyber Media Guidelines

- Paper Subscription

- Privacy Policy

- Discussion Guideline

- Term of Use

© 2016 - 2024 PT. Bina Media Tenggara

Your Opinion Matters

Share your experiences, suggestions, and any issues you've encountered on The Jakarta Post. We're here to listen.

Thank you for sharing your thoughts. We appreciate your feedback.

Other Papers Say: Face up to tech in education

The following editorial originally appeared in The Seattle Times:

The latest large-scale analysis of remote learning and its effects on student achievement underscores what every parent saw with devastating clarity during the pandemic: Children need human connection to thrive.

In fact, according to a recent New York Times investigation, attending school through a computer screen during the COVID-19 crisis was as deleterious to learning as growing up in poverty.

The takeaway should not be more finger-pointing and blame for officials who kept schools closed. That advances nothing. But a muscular and forward-looking confrontation with questions around technology in education is sorely needed.

One reason is that kids will likely face future emergencies that necessitate remote learning, so it’s imperative to get better at delivering education this way. But even now, with students back in class, the same technology that hijacked their attention at home remains present — cellphones. Before the pandemic, these handheld screens were not a ubiquitous force in every classroom. Now, teachers appear powerless against them.

Seattle Public Schools attempted to take a stand by filing a lawsuit against the social media companies running Facebook, TikTok and the like. That is hardly the most direct approach.

Better to do like the Reardan-Edwall district in Eastern Washington, which this year prohibited younger students from possessing cellphones during the school day. Or the Peninsula and Aberdeen school districts, which also have strict anti-cellphone policies.

“We’re having actual, human conversations again,” said a relieved Eric Sobotta, superintendent of the Reardan-Edwall schools, “and we’ve seen a dramatic reduction in bullying.”

Taking responsibility this way puts these districts in Washington’s vanguard. Technology has enormous power, and its potential in education — for good or ill — must be addressed head-on at the state level, not with limp demurrals about local control.

Rep. Stephanie McClintock, R-Vancouver, attempted to get a law passed during this year’s legislative session that would have restricted cellphone use in Washington schools. Her bill never made it out of committee, but she plans to reintroduce it next year.

A study from the London School of Economics found that the mere presence of a phone in class can hamper student achievement, especially for kids who are already struggling.

Earlier this year, state Superintendent Chris Reykdal issued guidance on using artificial intelligence in classrooms, urging teachers to embrace it as a tool to power human inquiry.

That’s a welcome step forward. But it’s just a beginning. To protect kids’ developing brains and capitalize on technology’s undeniable promise, all of Washington’s education leaders need to get a lot smarter about managing these tools — fast. The future is not coming at us; it’s already here.

Related Stories

- Share full article

Advertisement

Why School Absences Have ‘Exploded’ Almost Everywhere

The pandemic changed families’ lives and the culture of education: “Our relationship with school became optional.”

By Sarah Mervosh and Francesca Paris

Sarah Mervosh reports on K-12 education, and Francesca Paris is a data reporter.

In Anchorage, affluent families set off on ski trips and other lengthy vacations, with the assumption that their children can keep up with schoolwork online.

In a working-class pocket of Michigan, school administrators have tried almost everything, including pajama day, to boost student attendance.

And across the country, students with heightened anxiety are opting to stay home rather than face the classroom.

In the four years since the pandemic closed schools, U.S. education has struggled to recover on a number of fronts, from learning loss , to enrollment , to student behavior .

But perhaps no issue has been as stubborn and pervasive as a sharp increase in student absenteeism, a problem that cuts across demographics and has continued long after schools reopened.

Nationally, an estimated 26 percent of public school students were considered chronically absent last school year, up from 15 percent before the pandemic, according to the most recent data, from 40 states and Washington, D.C., compiled by the conservative-leaning American Enterprise Institute . Chronic absence is typically defined as missing at least 10 percent of the school year, or about 18 days, for any reason.

Source: Upshot analysis of data from Nat Malkus, American Enterprise Institute. Districts are grouped into highest, middle and lowest third.

The increases have occurred in districts big and small, and across income and race. For districts in wealthier areas, chronic absenteeism rates have about doubled, to 19 percent in the 2022-23 school year from 10 percent before the pandemic, a New York Times analysis of the data found.

Poor communities, which started with elevated rates of student absenteeism, are facing an even bigger crisis: Around 32 percent of students in the poorest districts were chronically absent in the 2022-23 school year, up from 19 percent before the pandemic.

Even districts that reopened quickly during the pandemic, in fall 2020, have seen vast increases.

“The problem got worse for everybody in the same proportional way,” said Nat Malkus, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, who collected and studied the data.

Victoria, Texas reopened schools in August 2020, earlier than many other districts. Even so, student absenteeism in the district has doubled.

Kaylee Greenlee for The New York Times

The trends suggest that something fundamental has shifted in American childhood and the culture of school, in ways that may be long lasting. What was once a deeply ingrained habit — wake up, catch the bus, report to class — is now something far more tenuous.

“Our relationship with school became optional,” said Katie Rosanbalm, a psychologist and associate research professor with the Center for Child and Family Policy at Duke University.

The habit of daily attendance — and many families’ trust — was severed when schools shuttered in spring 2020. Even after schools reopened, things hardly snapped back to normal. Districts offered remote options, required Covid-19 quarantines and relaxed policies around attendance and grading .

Source: Nat Malkus, American Enterprise Institute . Includes districts with at least 1,500 students in 2019. Numbers are rounded. U.S. average is estimated.

Today, student absenteeism is a leading factor hindering the nation’s recovery from pandemic learning losses , educational experts say. Students can’t learn if they aren’t in school. And a rotating cast of absent classmates can negatively affect the achievement of even students who do show up, because teachers must slow down and adjust their approach to keep everyone on track.

“If we don’t address the absenteeism, then all is naught,” said Adam Clark, the superintendent of Mt. Diablo Unified, a socioeconomically and racially diverse district of 29,000 students in Northern California, where he said absenteeism has “exploded” to about 25 percent of students. That’s up from 12 percent before the pandemic.

U.S. students, overall, are not caught up from their pandemic losses. Absenteeism is one key reason.

Why Students Are Missing School

Schools everywhere are scrambling to improve attendance, but the new calculus among families is complex and multifaceted.

At South Anchorage High School in Anchorage, where students are largely white and middle-to-upper income, some families now go on ski trips during the school year, or take advantage of off-peak travel deals to vacation for two weeks in Hawaii, said Sara Miller, a counselor at the school.

For a smaller number of students at the school who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, the reasons are different, and more intractable. They often have to stay home to care for younger siblings, Ms. Miller said. On days they miss the bus, their parents are busy working or do not have a car to take them to school.

And because teachers are still expected to post class work online, often nothing more than a skeleton version of an assignment, families incorrectly think students are keeping up, Ms. Miller said.

Sara Miller, a counselor at South Anchorage High School for 20 years, now sees more absences from students across the socioeconomic spectrum.

Ash Adams for The New York Times

Across the country, students are staying home when sick , not only with Covid-19, but also with more routine colds and viruses.

And more students are struggling with their mental health, one reason for increased absenteeism in Mason, Ohio, an affluent suburb of Cincinnati, said Tracey Carson, a district spokeswoman. Because many parents can work remotely, their children can also stay home.

For Ashley Cooper, 31, of San Marcos, Texas, the pandemic fractured her trust in an education system that she said left her daughter to learn online, with little support, and then expected her to perform on grade level upon her return. Her daughter, who fell behind in math, has struggled with anxiety ever since, she said.

“There have been days where she’s been absolutely in tears — ‘Can’t do it. Mom, I don’t want to go,’” said Ms. Cooper, who has worked with the nonprofit Communities in Schools to improve her children’s school attendance. But she added, “as a mom, I feel like it’s OK to have a mental health day, to say, ‘I hear you and I listen. You are important.’”

Experts say missing school is both a symptom of pandemic-related challenges, and also a cause. Students who are behind academically may not want to attend, but being absent sets them further back. Anxious students may avoid school, but hiding out can fuel their anxiety.

And schools have also seen a rise in discipline problems since the pandemic, an issue intertwined with absenteeism.

Dr. Rosanbalm, the Duke psychologist, said both absenteeism and behavioral outbursts are examples of the human stress response, now playing out en masse in schools: fight (verbal or physical aggression) or flight (absenteeism).

“If kids are not here, they are not forming relationships,” said Quintin Shepherd, the superintendent in Victoria, Texas.

Quintin Shepherd, the superintendent in Victoria, Texas, first put his focus on student behavior, which he described as a “fire in the kitchen” after schools reopened in August 2020.

The district, which serves a mostly low-income and Hispanic student body of around 13,000, found success with a one-on-one coaching program that teaches coping strategies to the most disruptive students. In some cases, students went from having 20 classroom outbursts per year to fewer than five, Dr. Shepherd said.

But chronic absenteeism is yet to be conquered. About 30 percent of students are chronically absent this year, roughly double the rate before the pandemic.

Dr. Shepherd, who originally hoped student absenteeism would improve naturally with time, has begun to think that it is, in fact, at the root of many issues.

“If kids are not here, they are not forming relationships,” he said. “If they are not forming relationships, we should expect there will be behavior and discipline issues. If they are not here, they will not be academically learning and they will struggle. If they struggle with their coursework, you can expect violent behaviors.”

Teacher absences have also increased since the pandemic, and student absences mean less certainty about which friends and classmates will be there. That can lead to more absenteeism, said Michael A. Gottfried, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education. His research has found that when 10 percent of a student’s classmates are absent on a given day, that student is more likely to be absent the following day.

Absent classmates can have a negative impact on the achievement and attendance of even the students who do show up.

Is This the New Normal?

In many ways, the challenge facing schools is one felt more broadly in American society: Have the cultural shifts from the pandemic become permanent?

In the work force, U.S. employees are still working from home at a rate that has remained largely unchanged since late 2022 . Companies have managed to “put the genie back in the bottle” to some extent by requiring a return to office a few days a week, said Nicholas Bloom, an economist at Stanford University who studies remote work. But hybrid office culture, he said, appears here to stay.

Some wonder whether it is time for schools to be more pragmatic.

Lakisha Young, the chief executive of the Oakland REACH, a parent advocacy group that works with low-income families in California, suggested a rigorous online option that students could use in emergencies, such as when a student misses the bus or has to care for a family member. “The goal should be, how do I ensure this kid is educated?” she said.

Relationships with adults at school and other classmates are crucial for attendance.

In the corporate world, companies have found some success appealing to a sense of social responsibility, where colleagues rely on each other to show up on the agreed-upon days.

A similar dynamic may be at play in schools, where experts say strong relationships are critical for attendance.

There is a sense of: “If I don’t show up, would people even miss the fact that I’m not there?” said Charlene M. Russell-Tucker, the commissioner of education in Connecticut.

In her state, a home visit program has yielded positive results , in part by working with families to address the specific reasons a student is missing school, but also by establishing a relationship with a caring adult. Other efforts — such as sending text messages or postcards to parents informing them of the number of accumulated absences — can also be effective.

Regina Murff has worked to re-establish the daily habit of school attendance for her sons, who are 6 and 12.

Sylvia Jarrus for The New York Times

In Ypsilanti, Mich., outside of Ann Arbor, a home visit helped Regina Murff, 44, feel less alone when she was struggling to get her children to school each morning.

After working at a nursing home during the pandemic, and later losing her sister to Covid-19, she said, there were days she found it difficult to get out of bed. Ms. Murff was also more willing to keep her children home when they were sick, for fear of accidentally spreading the virus.

But after a visit from her school district, and starting therapy herself, she has settled into a new routine. She helps her sons, 6 and 12, set out their outfits at night and she wakes up at 6 a.m. to ensure they get on the bus. If they are sick, she said, she knows to call the absence into school. “I’ve done a huge turnaround in my life,” she said.

But bringing about meaningful change for large numbers of students remains slow, difficult work .

Nationally, about 26 percent of students were considered chronically absent last school year, up from 15 percent before the pandemic.

The Ypsilanti school district has tried a bit of everything, said the superintendent, Alena Zachery-Ross. In addition to door knocks, officials are looking for ways to make school more appealing for the district’s 3,800 students, including more than 80 percent who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. They held themed dress-up days — ’70s day, pajama day — and gave away warm clothes after noticing a dip in attendance during winter months.

“We wondered, is it because you don’t have a coat, you don’t have boots?” said Dr. Zachery-Ross.

Still, absenteeism overall remains higher than it was before the pandemic. “We haven’t seen an answer,” she said.

Data provided by Nat Malkus, with the American Enterprise Institute. The data was originally published on the Return to Learn tracker and used for the report “ Long COVID for Public Schools: Chronic Absenteeism Before and After the Pandemic .”

The analysis for each year includes all districts with available data for that year, weighted by district size. Data are sourced from states, where available, and the U.S. Department of Education and NCES Common Core of Data.

For the 2018-19 school year, data was available for all 50 states and the District of Columbia. For 2022-23, it was available for 40 states and D.C., due to delays in state reporting.

Closure length status is based on the most in-person learning option available. Poverty is measured using the Census Bureau’s Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates. School size and minority population estimates are from NCES CCD.

How absenteeism is measured can vary state by state, which means comparisons across state lines may not be reliable.

An earlier version of this article misnamed a research center at Duke University. It is the Center for Child and Family Policy, not the Center of Child and Family Policy.

Students learning English at risk as pandemic funding dries up

U .S. school districts are facing a pandemic funding cliff this year that threatens students learning English as a second language.

Why it matters: One in five K-12 students in the U.S. speaks a language other than English at home, and 10% of the student population is enrolled in language development services, according to TNTP, an education research and advocacy organization.

- School closures during COVID-19 had a disproportionate impact on English-language learners, per prior research .

Context: In response to the disruption the pandemic caused to public education, the federal government in 2020 began to dole out billions of dollars for schools through the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSR) fund .

- Some of those districts used the funding to provide key services to multilingual learners, or students whose first language isn't English.

The latest: The funding is set to expire in September but the government is extending it from 120 days to as long as 14 months.

- Jazmin Flores Peña, a policy analyst at the national nonprofit advocacy group All4Ed, says the extensions will give districts some wiggle room, but the big question right now is what will happen when the funds ultimately run dry.

- "At the end of the day, this becomes about choices" over how much to fund programs for multilingual learners, she says, adding that districts need to have a solid commitment to English learners and seek other funding sources.

- Leticia de la Vara, chief of policy, engagements and external affairs for TNTP, tells Axios Latino the end of pandemic funding is "actually an opportunity to rethink how we will fund for this component of the education budget."

Zoom in: Surry County Schools in rural North Carolina used roughly $539,000 in ESSER funds since 2020 to pay for more staff and new technology for multilingual learners, says LuAnne Llewellyn, the district's director of federal programs.

- About 12% of students in the district's 20 schools are learning English. Although the most common first language is Spanish, there's been a recent increase in Vietnamese speakers, Llewellyn says.

- Using ESSER funds, Surry County Schools hired three new multilingual specialists, narrowing the ratio from one specialist per 95 students to one per 53.

- Those specialists are now able to spend about five days each week with students at various schools.

What they're saying: Llewellyn says it's important to understand that students come to school with varying levels of education and a variety of backgrounds. Some students from Central America, for example, speak Indigenous languages rather than Spanish.

- "There's richness and tapestry woven within all of them because of their culture, their background experiences. So when we work with our students and families, we have to take that into consideration."

What's next: In anticipation of the ESSR funds drying up, the district has already turned to other federal and state sources to hold on to the new staff.

What to watch: The funds helped level the playing field for multilingual learners, who advocates have long said receive fewer resources and funding than other students.

- Some analysts argue the federal government should increase Title III funding allocated to schools with a large share of multilingual learners.

- The Migration Policy Institute urged the federal government to collect and make public information on how states and local districts used ESSER funds to serve multilingual learners.

Subscribe to Axios Latino to get vital news about Latinos and Latin America, delivered to your inbox on Tuesdays and Thursdays.

Get more international news in your inbox with Axios World.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

The Effect of COVID-19 on Education

Jacob hoofman.

a Wayne State University School of Medicine, 540 East Canfield, Detroit, MI 48201, USA

Elizabeth Secord

b Department of Pediatrics, Wayne Pediatrics, School of Medicine, Pediatrics Wayne State University, 400 Mack Avenue, Detroit, MI 48201, USA

COVID-19 has changed education for learners of all ages. Preliminary data project educational losses at many levels and verify the increased anxiety and depression associated with the changes, but there are not yet data on long-term outcomes. Guidance from oversight organizations regarding the safety and efficacy of new delivery modalities for education have been quickly forged. It is no surprise that the socioeconomic gaps and gaps for special learners have widened. The medical profession and other professions that teach by incrementally graduated internships are also severely affected and have had to make drastic changes.

- • Virtual learning has become a norm during COVID-19.

- • Children requiring special learning services, those living in poverty, and those speaking English as a second language have lost more from the pandemic educational changes.

- • For children with attention deficit disorder and no comorbidities, virtual learning has sometimes been advantageous.

- • Math learning scores are more likely to be affected than language arts scores by pandemic changes.

- • School meals, access to friends, and organized activities have also been lost with the closing of in-person school.

The transition to an online education during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic may bring about adverse educational changes and adverse health consequences for children and young adult learners in grade school, middle school, high school, college, and professional schools. The effects may differ by age, maturity, and socioeconomic class. At this time, we have few data on outcomes, but many oversight organizations have tried to establish guidelines, expressed concerns, and extrapolated from previous experiences.

General educational losses and disparities

Many researchers are examining how the new environment affects learners’ mental, physical, and social health to help compensate for any losses incurred by this pandemic and to better prepare for future pandemics. There is a paucity of data at this juncture, but some investigators have extrapolated from earlier school shutdowns owing to hurricanes and other natural disasters. 1

Inclement weather closures are estimated in some studies to lower middle school math grades by 0.013 to 0.039 standard deviations and natural disaster closures by up to 0.10 standard deviation decreases in overall achievement scores. 2 The data from inclement weather closures did show a more significant decrease for children dependent on school meals, but generally the data were not stratified by socioeconomic differences. 3 , 4 Math scores are impacted overall more negatively by school absences than English language scores for all school closures. 4 , 5

The Northwest Evaluation Association is a global nonprofit organization that provides research-based assessments and professional development for educators. A team of researchers at Stanford University evaluated Northwest Evaluation Association test scores for students in 17 states and the District of Columbia in the Fall of 2020 and estimated that the average student had lost one-third of a year to a full year's worth of learning in reading, and about three-quarters of a year to more than 1 year in math since schools closed in March 2020. 5

With school shifted from traditional attendance at a school building to attendance via the Internet, families have come under new stressors. It is increasingly clear that families depended on schools for much more than math and reading. Shelter, food, health care, and social well-being are all part of what children and adolescents, as well as their parents or guardians, depend on schools to provide. 5 , 6

Many families have been impacted negatively by the loss of wages, leading to food insecurity and housing insecurity; some of loss this is a consequence of the need for parents to be at home with young children who cannot attend in-person school. 6 There is evidence that this economic instability is leading to an increase in depression and anxiety. 7 In 1 survey, 34.71% of parents reported behavioral problems in their children that they attributed to the pandemic and virtual schooling. 8

Children have been infected with and affected by coronavirus. In the United States, 93,605 students tested positive for COVID-19, and it was reported that 42% were Hispanic/Latino, 32% were non-Hispanic White, and 17% were non-Hispanic Black, emphasizing a disproportionate effect for children of color. 9 COVID infection itself is not the only issue that affects children’s health during the pandemic. School-based health care and school-based meals are lost when school goes virtual and children of lower socioeconomic class are more severely affected by these losses. Although some districts were able to deliver school meals, school-based health care is a primary source of health care for many children and has left some chronic conditions unchecked during the pandemic. 10

Many families report that the stress of the pandemic has led to a poorer diet in children with an increase in the consumption of sweet and fried foods. 11 , 12 Shelter at home orders and online education have led to fewer exercise opportunities. Research carried out by Ammar and colleagues 12 found that daily sitting had increased from 5 to 8 hours a day and binge eating, snacking, and the number of meals were all significantly increased owing to lockdown conditions and stay-at-home initiatives. There is growing evidence in both animal and human models that diets high in sugar and fat can play a detrimental role in cognition and should be of increased concern in light of the pandemic. 13

The family stress elicited by the COVID-19 shutdown is a particular concern because of compiled evidence that adverse life experiences at an early age are associated with an increased likelihood of mental health issues as an adult. 14 There is early evidence that children ages 6 to 18 years of age experienced a significant increase in their expression of “clinginess, irritability, and fear” during the early pandemic school shutdowns. 15 These emotions associated with anxiety may have a negative impact on the family unit, which was already stressed owing to the pandemic.

Another major concern is the length of isolation many children have had to endure since the pandemic began and what effects it might have on their ability to socialize. The school, for many children, is the agent for forming their social connections as well as where early social development occurs. 16 Noting that academic performance is also declining the pandemic may be creating a snowball effect, setting back children without access to resources from which they may never recover, even into adulthood.

Predictions from data analysis of school absenteeism, summer breaks, and natural disaster occurrences are imperfect for the current situation, but all indications are that we should not expect all children and adolescents to be affected equally. 4 , 5 Although some children and adolescents will likely suffer no long-term consequences, COVID-19 is expected to widen the already existing educational gap from socioeconomic differences, and children with learning differences are expected to suffer more losses than neurotypical children. 4 , 5

Special education and the COVID-19 pandemic

Although COVID-19 has affected all levels of education reception and delivery, children with special needs have been more profoundly impacted. Children in the United States who have special needs have legal protection for appropriate education by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. 17 , 18 Collectively, this legislation is meant to allow for appropriate accommodations, services, modifications, and specialized academic instruction to ensure that “every child receives a free appropriate public education . . . in the least restrictive environment.” 17

Children with autism usually have applied behavioral analysis (ABA) as part of their individualized educational plan. ABA therapists for autism use a technique of discrete trial training that shapes and rewards incremental changes toward new behaviors. 19 Discrete trial training involves breaking behaviors into small steps and repetition of rewards for small advances in the steps toward those behaviors. It is an intensive one-on-one therapy that puts a child and therapist in close contact for many hours at a time, often 20 to 40 hours a week. This therapy works best when initiated at a young age in children with autism and is often initiated in the home. 19

Because ABA workers were considered essential workers from the early days of the pandemic, organizations providing this service had the responsibility and the freedom to develop safety protocols for delivery of this necessary service and did so in conjunction with certifying boards. 20

Early in the pandemic, there were interruptions in ABA followed by virtual visits, and finally by in-home therapy with COVID-19 isolation precautions. 21 Although the efficacy of virtual visits for ABA therapy would empirically seem to be inferior, there are few outcomes data available. The balance of safety versus efficacy quite early turned to in-home services with interruptions owing to illness and decreased therapist availability owing to the pandemic. 21 An overarching concern for children with autism is the possible loss of a window of opportunity to intervene early. Families of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder report increased stress compared with families of children with other disabilities before the pandemic, and during the pandemic this burden has increased with the added responsibility of monitoring in-home schooling. 20

Early data on virtual schooling children with attention deficit disorder (ADD) and attention deficit with hyperactivity (ADHD) shows that adolescents with ADD/ADHD found the switch to virtual learning more anxiety producing and more challenging than their peers. 22 However, according to a study in Ireland, younger children with ADD/ADHD and no other neurologic or psychiatric diagnoses who were stable on medication tended to report less anxiety with at-home schooling and their parents and caregivers reported improved behavior during the pandemic. 23 An unexpected benefit of shelter in home versus shelter in place may be to identify these stressors in face-to-face school for children with ADD/ADHD. If children with ADD/ADHD had an additional diagnosis of autism or depression, they reported increased anxiety with the school shutdown. 23 , 24

Much of the available literature is anticipatory guidance for in-home schooling of children with disabilities rather than data about schooling during the pandemic. The American Academy of Pediatrics published guidance advising that, because 70% of students with ADHD have other conditions, such as learning differences, oppositional defiant disorder, or depression, they may have very different responses to in home schooling which are a result of the non-ADHD diagnosis, for example, refusal to attempt work for children with oppositional defiant disorder, severe anxiety for those with depression and or anxiety disorders, and anxiety and perseveration for children with autism. 25 Children and families already stressed with learning differences have had substantial challenges during the COVID-19 school closures.

High school, depression, and COVID-19

High schoolers have lost a great deal during this pandemic. What should have been a time of establishing more independence has been hampered by shelter-in-place recommendations. Graduations, proms, athletic events, college visits, and many other social and educational events have been altered or lost and cannot be recaptured.

Adolescents reported higher rates of depression and anxiety associated with the pandemic, and in 1 study 14.4% of teenagers report post-traumatic stress disorder, whereas 40.4% report having depression and anxiety. 26 In another survey adolescent boys reported a significant decrease in life satisfaction from 92% before COVID to 72% during lockdown conditions. For adolescent girls, the decrease in life satisfaction was from 81% before COVID to 62% during the pandemic, with the oldest teenage girls reporting the lowest life satisfaction values during COVID-19 restrictions. 27 During the school shutdown for COVID-19, 21% of boys and 27% of girls reported an increase in family arguments. 26 Combine all of these reports with decreasing access to mental health services owing to pandemic restrictions and it becomes a complicated matter for parents to address their children's mental health needs as well as their educational needs. 28

A study conducted in Norway measured aspects of socialization and mood changes in adolescents during the pandemic. The opportunity for prosocial action was rated on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 6 (very much) based on how well certain phrases applied to them, for example, “I comforted a friend yesterday,” “Yesterday I did my best to care for a friend,” and “Yesterday I sent a message to a friend.” They also ranked mood by rating items on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 5 (very well) as items reflected their mood. 29 They found that adolescents showed an overall decrease in empathic concern and opportunity for prosocial actions, as well as a decrease in mood ratings during the pandemic. 29

A survey of 24,155 residents of Michigan projected an escalation of suicide risk for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender youth as well as those youth questioning their sexual orientation (LGBTQ) associated with increased social isolation. There was also a 66% increase in domestic violence for LGBTQ youth during shelter in place. 30 LGBTQ youth are yet another example of those already at increased risk having disproportionate effects of the pandemic.