- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Does Counter-Terrorism Work? by Richard English review – a thoughtful and authoritative analysis

The Belfast academic offers vitally important lessons about government strategies, from Northern Ireland to the Middle East, warning that few campaigns are a complete success

I n January 2002, during his State of the Union address, President George W Bush said that in “four short months” the US had “rallied a great coalition, captured, arrested and rid the world of thousands of terrorists … and terrorist leaders who urged followers to sacrifice their lives are running for their own”.

The term “war on terror” had been coined a few days after al-Qaida’s attacks of 9/11 to describe the most extensive and ambitious counter-terrorism operation the world had seen. As Bush spoke, it all seemed to be going rather well.

Two decades later, with more than 300,000 people killed in Iraq, according to some estimates, and perhaps 240,000 deaths in Afghanistan, the violence of the “war on terror” can be seen to have created further chaos and carnage. Even excluding Iraq and Afghanistan, the numbers killed in terrorist attacks around the world rose from 109 a month in the years before 9/11, according to one study , to 158 a month during the six years that followed. Meanwhile, some of those whom Bush said were running for their lives are now in power in Kabul.

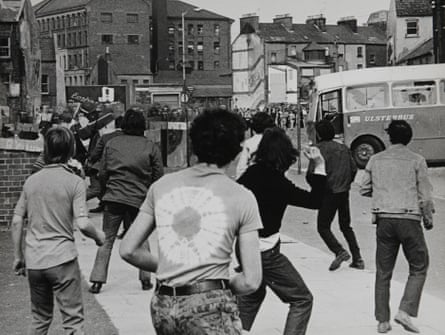

In Northern Ireland , on the other hand, the conflict came largely to an end – after 30 years – once British governments began to use the military and police to contain, rather than attempt to brutally extirpate, anti-state violence. Security forces patiently developed their intelligence-gathering capacities, while government ministers acknowledged the political causes of terrorism and, eventually, formed partnerships with those whom they had been fighting.

Richard English, the author of Does Counter-Terrorism Work? , is a professor of political history at Queen’s University Belfast, and has dedicated decades to the analysis of terrorism and to governments’ efforts to overcome it. Given that the choices made in counter-terrorism policy impact directly upon each of us every day, it is a vitally important area of study.

His previous work includes a 2016 volume, Does Terrorism Work? , and a highly regarded history of the IRA . Here, he offers a thoughtful and authoritative dissection of the counter-terrorism efforts of the “war on terror”, Northern Ireland’s Troubles and the Israel-Palestinian conflict, and the lessons that each can offer.

English believes that post-9/11 counter-terrorism was far too short-termist, that the histories of Afghanistan and Iraq were “substantially ignored in a disgraceful fashion” and that the US became overly impressed with its own early military successes in both countries.

In Iraq, the claim that the removal of Saddam Hussein from power was a necessary part of a global counter-terrorist campaign was, of course, founded on the false claim that Saddam was supporting al-Qaida and the mistaken belief that he possessed weapons of mass destruction. Moreover, English writes, the assumption that the Middle East could be recast “through naive invasion” took no account of the region’s past, its complex allegiances, or the possibility of something simply going wrong.

He cautions that very few counter-terrorism campaigns will ever achieve complete strategic success. Unconvinced by those who claim bullishly that the Provisional IRA was “defeated”, he argues persuasively that the republican movement’s sustainable campaign of violence was suspended only because its pragmatic leaders decided that they might more likely achieve their objective – a united Ireland – by peaceful means. Equally, he is sceptical of those among his fellow academics who argue that counter-terrorism operations will inevitably promote terrorism.

However, he writes, there are times when “those who criticise counter-terrorists for worsening their state’s strategic position regarding terrorism, and those who celebrate tactical-operational successes against terrorist adversaries, might shout past each other while yet both being right”.

English judges that if any counter-terrorism campaign is to achieve even partial strategic victory, it must be conducted in a patient, well-resourced manner, with clear objectives. Given that terrorists often seek to provoke outrage and overreaction, the public should be encouraged to be realistic about the limits to what can be accomplished.

He also concludes that to avoid failure, counter-terrorist efforts must be integrated into broader political initiatives: “We should not mistake the terrorist symptom for the more profound issues that are at stake.”

Although this book was written before the Hamas attacks of 7 October and the war in Gaza, English was already convinced that Israeli counter-terrorism tactics, no matter how carefully conceived or brilliantly executed, will not resolve the conflict unless there is a strategic engagement with Palestinian grievances and desire for statehood.

Finally, he cautions that his three case studies present serious warnings about the self-harm that can be inflicted by state actions judged to lack morality. All three have involved the abuse of prisoners; that an overreliance on aggressive military methods can shatter public support; that technical surveillance should be lawful and proportionate; and, as a senior British police officer warned in a report published this month , that there are serious questions to be asked about the morality and legality of allowing informants within terrorist organisations to commit serious crimes.

“A successful counter-terrorism will be a just counter-terrorism,” English writes: legally bound, accountable and proportionate. To stray from this, he says, risks delegitimising the objectives of the state. Or as a mural in Northern Ireland used to say: “When those who make the law, break the law, in the name of the law, there is no law.”

Ian Cobain is the author of Anatomy of a Killing: Life and Death on a Divided Island (Granta)

Does Counter-Terrorism Work? by Richard English is published by Oxford University Press (£25). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com . Delivery charges may apply

- Politics books

- The Observer

- UK security and counter-terrorism

- Counter-terrorism policy

- Northern Ireland

- Israel-Gaza war

- Afghanistan

Most viewed

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Sensible Ways to Fight Terrorism

More from our inbox:, the quake, as felt in manhattan, r.f.k. jr.’s claim of ‘censorship’, obstacles to liberalism, prioritizing and valuing care jobs.

To the Editor:

Re “ The West Still Hasn’t Figured Out How to Beat ISIS ,” by Christopher P. Costa and Colin P. Clarke (Opinion guest essay, April 1):

Two clear lessons have emerged in the decade since ISIS exploded on the world scene. First, as the authors note, pulling all U.S. troops and intelligence assets from fragile conflict zones is a boon to globalized terror movements. Despite political promises, the full U.S. withdrawal from Iraq in 2011 and Afghanistan in 2021 did not “end” those wars; it transformed them into more complex and potentially more deadly challenges.

Second, we must reckon with the underlying grievances that make violent anti-Western ideologies, including militant jihadism, attractive to so many in the first place. These include the ill effects of globalization, and a “rules-based” world order increasingly insensitive to the needs of developing countries and regions.

Simply maintaining a military or intelligence presence in terror hot spots does nothing to reduce the sticky recruiting power of militant movements. Unless the United States and its allies and partners begin offering tangible policies that counter jihadi ideology and propaganda, we will just continue attacking the symptoms, not the causes.

Stuart Gottlieb New York The writer teaches American foreign policy and international security at Columbia University.

The Islamic State’s territorial caliphate in Iraq and Syria may have been eliminated years ago, but as Christopher P. Costa and Colin P. Clarke write, the terrorist group itself is very much in business. ISIS-K, its branch in Afghanistan, has conducted two large-scale external attacks over the last two months — one in Iran that killed more than 80 people and another near Moscow that took the lives of more than 130.

If the United States and its allies haven’t found a way to defeat ISIS-K in its entirety, it’s because terrorism itself is an enemy that can’t be defeated in the traditional sense of the term. This is why the war on terror framework, initiated under the George W. Bush administration immediately after the 9/11 attacks, was such poor terminology. Terrorism is going to be with us for as long as humanity exists.

Viewed this way, terrorism is a conflict management problem, not one that can be solved. While this may sound defeatist to many, it’s also the coldhearted truth. Assuming otherwise risks enacting policies, like invading whole countries (Iraq and Afghanistan), that are likely to create even more anti-U.S. terrorism than we started with.

Of course, all countries should remain vigilant. Terrorism will continue to be a part of the threat environment. The U.S. intelligence community must ensure that its counterterrorism infrastructure is well resourced and continues to focus on areas, like Afghanistan, where the U.S. no longer has a troop presence. But for the U.S., a big part of the solution is keeping our ambitions realistic and prioritizing among terrorist threats lest the system gets overloaded or pulled in too many directions at once.

While all terrorism is tragic, not all terrorist groups are created equal. Local and even regional groups with local objectives aren’t as important to the U.S. as groups that have transnational aims and the capabilities to strike U.S. targets. This, combined with keeping a cool head instead of trafficking in threat inflation, is key to a successful response.

Daniel R. DePetris New Rochelle, N.Y. The writer is a fellow at Defense Priorities, a foreign policy think tank in Washington.

Re “ Earthquake Rattles Northeast, but Little Damage Is Reported ” (live updates, nytimes.com, April 5):

I’m lying in bed Friday morning, on 14th Street in Manhattan. Suddenly I feel and see the bed start to shake!

My first thought — OMG, I’m in “The Exorcist.” Then an alert on my phone tells me that it’s an earthquake in New York City.

Frankly, I’m not sure which one scared me more.

Steven Doloff New York

Re “ Kennedy Calls Biden Bigger Threat to Democracy Than Trump ” (news article, April 3):

Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s concern about the Biden administration’s “censorship” of misinformation might be viewed as legitimate if the American public demonstrated more responsibility about fact-checking what they see and hear on social media and other information platforms masquerading as legitimate sources of news.

Sadly, many in this country, and indeed the world, have abdicated responsibility for being factually informed about current events. As long as bad actors have unfettered access to social media platforms, it will be necessary to “censor” the misinformation they claim as fact. The world has become the proverbial crowded theater where one cannot yell “fire.”

Helen Ogden Pacific Grove, Calif.

Re “ The Great Struggle for Liberalism ,” by David Brooks (column, March 29):

In face of growing populism at home and abroad, Mr. Brooks issues a cri de coeur on behalf of liberal democracy and democratic capitalism, which provide the means to a “richer, fuller and more dynamic life.”

His impassioned plea for “we the people” of these United States to experience a sense of common purpose, to build a society in which culture is celebrated and families thrive, is made despite existential challenges to American liberalism:

1) We do not share an overarching belief in who we are as a people, as a nation.

2) Trust in our three branches of government, in checks and balances, is broken amid warring partisanship.

3) There is, for many, as Mr. Brooks notes, an “absence of meaning, belonging and recognition” that drives a tilt to authoritarianism in search of the restoration of “cultural, moral and civic stability” by any means necessary.

The ballot box in a free and open society allows for choice, and there are those who, in exercising their right to vote, would choose to cancel the aspirational hopes of the preamble to our Constitution.

David Brooks sees the full measure of the choices facing America and the world in 2024. Do we?

Michael Katz Washington

Re “ New Ways to Bring Wealth to Nations ,” by Patricia Cohen (news analysis, Business, April 4):

Ms. Cohen is right to argue that the service sector will be the key to economic growth in the future. However, it’s essential to consider what service jobs are — and who will be doing them.

Of course, the service industry includes office workers in tech hubs like Bengaluru, as highlighted by Ms. Cohen. Currently, these jobs are held predominantly by men, so to spur inclusive growth, employers and governments must make sure women have equal access.

But the service sector also includes hundreds of millions of people — mostly women — who are teachers and who care for children, older people and those with disabilities and illnesses. To seize the opportunity ahead, governments must position care jobs as careers of the future for women and men, alongside tech jobs. This requires making sure these positions provide good pay and working conditions.

If the goal is sustainable growth, the best approach leverages the critical care sector to generate income in the short run and prepare healthy, well-educated young people, which maintains progress in the long run.

Anita Zaidi Seattle The writer is president of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation’s Gender Equality Division.

- CBSE Class 10th

- CBSE Class 12th

- UP Board 10th

- UP Board 12th

- Bihar Board 10th

- Bihar Board 12th

- Top Schools in India

- Top Schools in Delhi

- Top Schools in Mumbai

- Top Schools in Chennai

- Top Schools in Hyderabad

- Top Schools in Kolkata

- Top Schools in Pune

- Top Schools in Bangalore

Products & Resources

- JEE Main Knockout April

- Free Sample Papers

- Free Ebooks

- NCERT Notes

- NCERT Syllabus

- NCERT Books

- RD Sharma Solutions

- Navodaya Vidyalaya Admission 2024-25

- NCERT Solutions

- NCERT Solutions for Class 12

- NCERT Solutions for Class 11

- NCERT solutions for Class 10

- NCERT solutions for Class 9

- NCERT solutions for Class 8

- NCERT Solutions for Class 7

- JEE Main 2024

- JEE Advanced 2024

- BITSAT 2024

- View All Engineering Exams

- Colleges Accepting B.Tech Applications

- Top Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Engineering Colleges Accepting JEE Main

- Top IITs in India

- Top NITs in India

- Top IIITs in India

- JEE Main College Predictor

- JEE Main Rank Predictor

- MHT CET College Predictor

- AP EAMCET College Predictor

- GATE College Predictor

- KCET College Predictor

- JEE Advanced College Predictor

- View All College Predictors

- JEE Main Question Paper

- JEE Main Mock Test

- JEE Main Registration

- JEE Main Syllabus

- Download E-Books and Sample Papers

- Compare Colleges

- B.Tech College Applications

- GATE 2024 Result

- MAH MBA CET Exam

- View All Management Exams

Colleges & Courses

- MBA College Admissions

- MBA Colleges in India

- Top IIMs Colleges in India

- Top Online MBA Colleges in India

- MBA Colleges Accepting XAT Score

- BBA Colleges in India

- XAT College Predictor 2024

- SNAP College Predictor

- NMAT College Predictor

- MAT College Predictor 2024

- CMAT College Predictor 2024

- CAT Percentile Predictor 2023

- CAT 2023 College Predictor

- CMAT 2024 Registration

- TS ICET 2024 Registration

- CMAT Exam Date 2024

- MAH MBA CET Cutoff 2024

- Download Helpful Ebooks

- List of Popular Branches

- QnA - Get answers to your doubts

- IIM Fees Structure

- AIIMS Nursing

- Top Medical Colleges in India

- Top Medical Colleges in India accepting NEET Score

- Medical Colleges accepting NEET

- List of Medical Colleges in India

- List of AIIMS Colleges In India

- Medical Colleges in Maharashtra

- Medical Colleges in India Accepting NEET PG

- NEET College Predictor

- NEET PG College Predictor

- NEET MDS College Predictor

- DNB CET College Predictor

- DNB PDCET College Predictor

- NEET Application Form 2024

- NEET PG Application Form 2024

- NEET Cut off

- NEET Online Preparation

- Download Helpful E-books

- LSAT India 2024

- Colleges Accepting Admissions

- Top Law Colleges in India

- Law College Accepting CLAT Score

- List of Law Colleges in India

- Top Law Colleges in Delhi

- Top Law Collages in Indore

- Top Law Colleges in Chandigarh

- Top Law Collages in Lucknow

Predictors & E-Books

- CLAT College Predictor

- MHCET Law ( 5 Year L.L.B) College Predictor

- AILET College Predictor

- Sample Papers

- Compare Law Collages

- Careers360 Youtube Channel

- CLAT Syllabus 2025

- CLAT Previous Year Question Paper

- AIBE 18 Result 2023

- NID DAT Exam

- Pearl Academy Exam

Animation Courses

- Animation Courses in India

- Animation Courses in Bangalore

- Animation Courses in Mumbai

- Animation Courses in Pune

- Animation Courses in Chennai

- Animation Courses in Hyderabad

- Design Colleges in India

- Fashion Design Colleges in Bangalore

- Fashion Design Colleges in Mumbai

- Fashion Design Colleges in Pune

- Fashion Design Colleges in Delhi

- Fashion Design Colleges in Hyderabad

- Fashion Design Colleges in India

- Top Design Colleges in India

- Free Design E-books

- List of Branches

- Careers360 Youtube channel

- NIFT College Predictor

- UCEED College Predictor

- NID DAT College Predictor

- IPU CET BJMC

- JMI Mass Communication Entrance Exam

- IIMC Entrance Exam

- Media & Journalism colleges in Delhi

- Media & Journalism colleges in Bangalore

- Media & Journalism colleges in Mumbai

- List of Media & Journalism Colleges in India

- CA Intermediate

- CA Foundation

- CS Executive

- CS Professional

- Difference between CA and CS

- Difference between CA and CMA

- CA Full form

- CMA Full form

- CS Full form

- CA Salary In India

Top Courses & Careers

- Bachelor of Commerce (B.Com)

- Master of Commerce (M.Com)

- Company Secretary

- Cost Accountant

- Charted Accountant

- Credit Manager

- Financial Advisor

- Top Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Government Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Private Commerce Colleges in India

- Top M.Com Colleges in Mumbai

- Top B.Com Colleges in India

- IT Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- IT Colleges in Uttar Pradesh

- MCA Colleges in India

- BCA Colleges in India

Quick Links

- Information Technology Courses

- Programming Courses

- Web Development Courses

- Data Analytics Courses

- Big Data Analytics Courses

- RUHS Pharmacy Admission Test

- Top Pharmacy Colleges in India

- Pharmacy Colleges in Pune

- Pharmacy Colleges in Mumbai

- Colleges Accepting GPAT Score

- Pharmacy Colleges in Lucknow

- List of Pharmacy Colleges in Nagpur

- GPAT Result

- GPAT 2024 Admit Card

- GPAT Question Papers

- NCHMCT JEE 2024

- Mah BHMCT CET

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Delhi

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Hyderabad

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Mumbai

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Maharashtra

- B.Sc Hotel Management

- Hotel Management

- Diploma in Hotel Management and Catering Technology

Diploma Colleges

- Top Diploma Colleges in Maharashtra

- UPSC IAS 2024

- SSC CGL 2024

- IBPS RRB 2024

- Previous Year Sample Papers

- Free Competition E-books

- Sarkari Result

- QnA- Get your doubts answered

- UPSC Previous Year Sample Papers

- CTET Previous Year Sample Papers

- SBI Clerk Previous Year Sample Papers

- NDA Previous Year Sample Papers

Upcoming Events

- NDA Application Form 2024

- UPSC IAS Application Form 2024

- CDS Application Form 2024

- CTET Admit card 2024

- HP TET Result 2023

- SSC GD Constable Admit Card 2024

- UPTET Notification 2024

- SBI Clerk Result 2024

Other Exams

- SSC CHSL 2024

- UP PCS 2024

- UGC NET 2024

- RRB NTPC 2024

- IBPS PO 2024

- IBPS Clerk 2024

- IBPS SO 2024

- Top University in USA

- Top University in Canada

- Top University in Ireland

- Top Universities in UK

- Top Universities in Australia

- Best MBA Colleges in Abroad

- Business Management Studies Colleges

Top Countries

- Study in USA

- Study in UK

- Study in Canada

- Study in Australia

- Study in Ireland

- Study in Germany

- Study in China

- Study in Europe

Student Visas

- Student Visa Canada

- Student Visa UK

- Student Visa USA

- Student Visa Australia

- Student Visa Germany

- Student Visa New Zealand

- Student Visa Ireland

- CUET PG 2024

- IGNOU B.Ed Admission 2024

- DU Admission

- UP B.Ed JEE 2024

- DDU Entrance Exam

- IIT JAM 2024

- IGNOU Online Admission 2024

- Universities in India

- Top Universities in India 2024

- Top Colleges in India

- Top Universities in Uttar Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Bihar

- Top Universities in Madhya Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Tamil Nadu 2024

- Central Universities in India

- CUET PG Admit Card 2024

- IGNOU Date Sheet

- CUET Mock Test 2024

- CUET Application Form 2024

- CUET PG Syllabus 2024

- CUET Participating Universities 2024

- CUET Previous Year Question Paper

- CUET Syllabus 2024 for Science Students

- E-Books and Sample Papers

- CUET Exam Pattern 2024

- CUET Exam Date 2024

- CUET Syllabus 2024

- IGNOU Exam Form 2024

- IGNOU Result

- CUET PG Courses 2024

Engineering Preparation

- Knockout JEE Main 2024

- Test Series JEE Main 2024

- JEE Main 2024 Rank Booster

Medical Preparation

- Knockout NEET 2024

- Test Series NEET 2024

- Rank Booster NEET 2024

Online Courses

- JEE Main One Month Course

- NEET One Month Course

- IBSAT Free Mock Tests

- IIT JEE Foundation Course

- Knockout BITSAT 2024

- Career Guidance Tool

Top Streams

- IT & Software Certification Courses

- Engineering and Architecture Certification Courses

- Programming And Development Certification Courses

- Business and Management Certification Courses

- Marketing Certification Courses

- Health and Fitness Certification Courses

- Design Certification Courses

Specializations

- Digital Marketing Certification Courses

- Cyber Security Certification Courses

- Artificial Intelligence Certification Courses

- Business Analytics Certification Courses

- Data Science Certification Courses

- Cloud Computing Certification Courses

- Machine Learning Certification Courses

- View All Certification Courses

- UG Degree Courses

- PG Degree Courses

- Short Term Courses

- Free Courses

- Online Degrees and Diplomas

- Compare Courses

Top Providers

- Coursera Courses

- Udemy Courses

- Edx Courses

- Swayam Courses

- upGrad Courses

- Simplilearn Courses

- Great Learning Courses

Access premium articles, webinars, resources to make the best decisions for career, course, exams, scholarships, study abroad and much more with

Plan, Prepare & Make the Best Career Choices

Essay on Terrorism

India has a lengthy history of terrorism. It is a cowardly act by terrorist organisations that want to sabotage the nation's tranquillity. It seeks to instil fear among the population. They seek to maintain a permanent climate of dread among the populace to prevent the nation from prospering. Here are a few sample essays on Terrorism .

100 Words Essay on Terrorism

Terrorism is the use of violence and intimidation in the pursuit of political and personal aims. It is a global phenomenon that has affected countries worldwide, causing harm to innocent civilians, damaging economies, and destabilizing governments. The causes of terrorism are complex and can include religious extremism, political oppression, and economic inequality.

Terrorist groups use a variety of tactics, including bombings, kidnappings, and hijackings, to achieve their goals. They often target symbols of government and military power, as well as civilians in crowded public spaces. The impact of terrorism on society is devastating, leading to loss of life, injury, and psychological trauma.

Combating terrorism requires a multifaceted approach, including intelligence gathering, law enforcement, and military action. Additionally, addressing underlying issues such as poverty and political marginalization is crucial in preventing the radicalization of individuals and the emergence of terrorist groups.

200 Words Essay on Terrorism

Terrorism is a complex and ever-evolving threat that affects countries and communities around the world. It involves the use of violence and intimidation to achieve political or ideological goals. The causes of terrorism can vary, but often include religious extremism, political oppression, and economic inequality.

To truly understand the impact of terrorism, it's important to consider not only the physical harm caused by terrorist attacks but also the emotional and psychological toll it takes on individuals and communities. The loss of life and injury caused to innocent civilians is devastating and can leave families and communities reeling for years to come. In addition, terrorism can cause physical damage to infrastructure and buildings, as well as economic disruption, leading to decreased tourism and investment.

To effectively combat terrorism, it's important to take a holistic approach that addresses not only the immediate threat of terrorist attacks but also the underlying issues that can lead to radicalization and the emergence of terrorist groups. This can include addressing poverty and economic inequality, promoting political and religious tolerance, and providing support and resources to individuals and communities at risk of radicalization.

It's also important to remember that the fight against terrorism is not just the responsibility of governments and law enforcement agencies, but also of individuals and communities. By promoting understanding and compassion, and by standing up against hate and extremism, we can all play a role in preventing terrorism and creating a more peaceful world.

500 Words Essay on Terrorism

According to a United Nations Security Council report from November 2004, terrorism is any act that is "intended to result in the death or serious bodily harm of civilians or non-combatants to intimidate the population or to compel the government or an international organisation to do or abstain from doing any act."

The Origins of Terrorism

The development or production of massive numbers of machine guns, atomic bombs, hydrogen bombs, nuclear weapons, missiles, and other weapons fuels terrorism. Rapid population growth, political, social, and economic problems, widespread discontent with the political system, a lack of education, racism, economic inequality, and linguistic discrepancies are all important contributors to the emergence of terrorism. Sometimes one uses terrorism to take a position and stick with it.

The Effects Of Terrorism

People become afraid of terrorism and feel unsafe in their nation. Terrorist attacks result in the destruction of millions of items, the death of thousands of innocent people, and the slaughter of animals. After seeing a terrorist incident, people become less inclined to believe in humanity, which breeds more terrorists.

Different forms of terrorism can be found both domestically and overseas. Today, governments worldwide are working hard to combat terrorism, which is an issue in India and our neighbouring nations. The 9/11 World Trade Centre attack is considered the worst terrorist act ever. Osama bin Laden attacked the tallest building in the world’s most powerful country, causing millions of casualties and the death of thousands of people.

The major incidents of the terrorist attack in India are—

12 March 1993 - A series of 13 bombs go off, killing 257

14 March 2003 - A bomb goes off in a train in Mulund, killing 10

29 October 2005 Delhi bombings

2005 Ram Janmabhoomi attack in Ayodhya

2006 Varanasi bombings

11 July 2006 - A series of seven bombs go off in trains, killing

26 November 2008 to 29 November 2008 - A series of coordinated attacks killed at least 170.

According to this data, India has experienced an upsurge in terrorist activity since 1980. India has fought four wars against terrorism , losing more than 6000 persons in total. Already, we have lost around 70000 citizens. Furthermore, we lost over 9000 security staff. In this country, about 6 lakh individuals have undergone.

Agencies In India Fighting Terrorism

There are numerous organisations working to rid our nation of terrorism. These organizations operate continuously, from the municipal to the national levels. To stop local terrorist activity, police forces have various divisions.

The police departments have a specialized intelligence and anti-terrorism division that is in charge of eliminating Naxalites and other terrorist organizations. The military is in charge of bombing terrorist targets outside of our country. These departments engage in counterinsurgency and other similar operations to dismantle various terrorist organisations.

There are numerous organisations that work to prevent terrorism. Anti-Terrorism Squad (ATS) , National Investigation Agency (NIA) , and Research and Analysis Wing are a few of the top organizations (RAW) . These are some of the main organizations working to rid India of terrorism.

Explore Career Options (By Industry)

- Construction

- Entertainment

- Manufacturing

- Information Technology

Data Administrator

Database professionals use software to store and organise data such as financial information, and customer shipping records. Individuals who opt for a career as data administrators ensure that data is available for users and secured from unauthorised sales. DB administrators may work in various types of industries. It may involve computer systems design, service firms, insurance companies, banks and hospitals.

Bio Medical Engineer

The field of biomedical engineering opens up a universe of expert chances. An Individual in the biomedical engineering career path work in the field of engineering as well as medicine, in order to find out solutions to common problems of the two fields. The biomedical engineering job opportunities are to collaborate with doctors and researchers to develop medical systems, equipment, or devices that can solve clinical problems. Here we will be discussing jobs after biomedical engineering, how to get a job in biomedical engineering, biomedical engineering scope, and salary.

Ethical Hacker

A career as ethical hacker involves various challenges and provides lucrative opportunities in the digital era where every giant business and startup owns its cyberspace on the world wide web. Individuals in the ethical hacker career path try to find the vulnerabilities in the cyber system to get its authority. If he or she succeeds in it then he or she gets its illegal authority. Individuals in the ethical hacker career path then steal information or delete the file that could affect the business, functioning, or services of the organization.

GIS officer work on various GIS software to conduct a study and gather spatial and non-spatial information. GIS experts update the GIS data and maintain it. The databases include aerial or satellite imagery, latitudinal and longitudinal coordinates, and manually digitized images of maps. In a career as GIS expert, one is responsible for creating online and mobile maps.

Data Analyst

The invention of the database has given fresh breath to the people involved in the data analytics career path. Analysis refers to splitting up a whole into its individual components for individual analysis. Data analysis is a method through which raw data are processed and transformed into information that would be beneficial for user strategic thinking.

Data are collected and examined to respond to questions, evaluate hypotheses or contradict theories. It is a tool for analyzing, transforming, modeling, and arranging data with useful knowledge, to assist in decision-making and methods, encompassing various strategies, and is used in different fields of business, research, and social science.

Geothermal Engineer

Individuals who opt for a career as geothermal engineers are the professionals involved in the processing of geothermal energy. The responsibilities of geothermal engineers may vary depending on the workplace location. Those who work in fields design facilities to process and distribute geothermal energy. They oversee the functioning of machinery used in the field.

Database Architect

If you are intrigued by the programming world and are interested in developing communications networks then a career as database architect may be a good option for you. Data architect roles and responsibilities include building design models for data communication networks. Wide Area Networks (WANs), local area networks (LANs), and intranets are included in the database networks. It is expected that database architects will have in-depth knowledge of a company's business to develop a network to fulfil the requirements of the organisation. Stay tuned as we look at the larger picture and give you more information on what is db architecture, why you should pursue database architecture, what to expect from such a degree and what your job opportunities will be after graduation. Here, we will be discussing how to become a data architect. Students can visit NIT Trichy , IIT Kharagpur , JMI New Delhi .

Remote Sensing Technician

Individuals who opt for a career as a remote sensing technician possess unique personalities. Remote sensing analysts seem to be rational human beings, they are strong, independent, persistent, sincere, realistic and resourceful. Some of them are analytical as well, which means they are intelligent, introspective and inquisitive.

Remote sensing scientists use remote sensing technology to support scientists in fields such as community planning, flight planning or the management of natural resources. Analysing data collected from aircraft, satellites or ground-based platforms using statistical analysis software, image analysis software or Geographic Information Systems (GIS) is a significant part of their work. Do you want to learn how to become remote sensing technician? There's no need to be concerned; we've devised a simple remote sensing technician career path for you. Scroll through the pages and read.

Budget Analyst

Budget analysis, in a nutshell, entails thoroughly analyzing the details of a financial budget. The budget analysis aims to better understand and manage revenue. Budget analysts assist in the achievement of financial targets, the preservation of profitability, and the pursuit of long-term growth for a business. Budget analysts generally have a bachelor's degree in accounting, finance, economics, or a closely related field. Knowledge of Financial Management is of prime importance in this career.

Underwriter

An underwriter is a person who assesses and evaluates the risk of insurance in his or her field like mortgage, loan, health policy, investment, and so on and so forth. The underwriter career path does involve risks as analysing the risks means finding out if there is a way for the insurance underwriter jobs to recover the money from its clients. If the risk turns out to be too much for the company then in the future it is an underwriter who will be held accountable for it. Therefore, one must carry out his or her job with a lot of attention and diligence.

Finance Executive

Product manager.

A Product Manager is a professional responsible for product planning and marketing. He or she manages the product throughout the Product Life Cycle, gathering and prioritising the product. A product manager job description includes defining the product vision and working closely with team members of other departments to deliver winning products.

Operations Manager

Individuals in the operations manager jobs are responsible for ensuring the efficiency of each department to acquire its optimal goal. They plan the use of resources and distribution of materials. The operations manager's job description includes managing budgets, negotiating contracts, and performing administrative tasks.

Stock Analyst

Individuals who opt for a career as a stock analyst examine the company's investments makes decisions and keep track of financial securities. The nature of such investments will differ from one business to the next. Individuals in the stock analyst career use data mining to forecast a company's profits and revenues, advise clients on whether to buy or sell, participate in seminars, and discussing financial matters with executives and evaluate annual reports.

A Researcher is a professional who is responsible for collecting data and information by reviewing the literature and conducting experiments and surveys. He or she uses various methodological processes to provide accurate data and information that is utilised by academicians and other industry professionals. Here, we will discuss what is a researcher, the researcher's salary, types of researchers.

Welding Engineer

Welding Engineer Job Description: A Welding Engineer work involves managing welding projects and supervising welding teams. He or she is responsible for reviewing welding procedures, processes and documentation. A career as Welding Engineer involves conducting failure analyses and causes on welding issues.

Transportation Planner

A career as Transportation Planner requires technical application of science and technology in engineering, particularly the concepts, equipment and technologies involved in the production of products and services. In fields like land use, infrastructure review, ecological standards and street design, he or she considers issues of health, environment and performance. A Transportation Planner assigns resources for implementing and designing programmes. He or she is responsible for assessing needs, preparing plans and forecasts and compliance with regulations.

Environmental Engineer

Individuals who opt for a career as an environmental engineer are construction professionals who utilise the skills and knowledge of biology, soil science, chemistry and the concept of engineering to design and develop projects that serve as solutions to various environmental problems.

Safety Manager

A Safety Manager is a professional responsible for employee’s safety at work. He or she plans, implements and oversees the company’s employee safety. A Safety Manager ensures compliance and adherence to Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) guidelines.

Conservation Architect

A Conservation Architect is a professional responsible for conserving and restoring buildings or monuments having a historic value. He or she applies techniques to document and stabilise the object’s state without any further damage. A Conservation Architect restores the monuments and heritage buildings to bring them back to their original state.

Structural Engineer

A Structural Engineer designs buildings, bridges, and other related structures. He or she analyzes the structures and makes sure the structures are strong enough to be used by the people. A career as a Structural Engineer requires working in the construction process. It comes under the civil engineering discipline. A Structure Engineer creates structural models with the help of computer-aided design software.

Highway Engineer

Highway Engineer Job Description: A Highway Engineer is a civil engineer who specialises in planning and building thousands of miles of roads that support connectivity and allow transportation across the country. He or she ensures that traffic management schemes are effectively planned concerning economic sustainability and successful implementation.

Field Surveyor

Are you searching for a Field Surveyor Job Description? A Field Surveyor is a professional responsible for conducting field surveys for various places or geographical conditions. He or she collects the required data and information as per the instructions given by senior officials.

Orthotist and Prosthetist

Orthotists and Prosthetists are professionals who provide aid to patients with disabilities. They fix them to artificial limbs (prosthetics) and help them to regain stability. There are times when people lose their limbs in an accident. In some other occasions, they are born without a limb or orthopaedic impairment. Orthotists and prosthetists play a crucial role in their lives with fixing them to assistive devices and provide mobility.

Pathologist

A career in pathology in India is filled with several responsibilities as it is a medical branch and affects human lives. The demand for pathologists has been increasing over the past few years as people are getting more aware of different diseases. Not only that, but an increase in population and lifestyle changes have also contributed to the increase in a pathologist’s demand. The pathology careers provide an extremely huge number of opportunities and if you want to be a part of the medical field you can consider being a pathologist. If you want to know more about a career in pathology in India then continue reading this article.

Veterinary Doctor

Speech therapist, gynaecologist.

Gynaecology can be defined as the study of the female body. The job outlook for gynaecology is excellent since there is evergreen demand for one because of their responsibility of dealing with not only women’s health but also fertility and pregnancy issues. Although most women prefer to have a women obstetrician gynaecologist as their doctor, men also explore a career as a gynaecologist and there are ample amounts of male doctors in the field who are gynaecologists and aid women during delivery and childbirth.

Audiologist

The audiologist career involves audiology professionals who are responsible to treat hearing loss and proactively preventing the relevant damage. Individuals who opt for a career as an audiologist use various testing strategies with the aim to determine if someone has a normal sensitivity to sounds or not. After the identification of hearing loss, a hearing doctor is required to determine which sections of the hearing are affected, to what extent they are affected, and where the wound causing the hearing loss is found. As soon as the hearing loss is identified, the patients are provided with recommendations for interventions and rehabilitation such as hearing aids, cochlear implants, and appropriate medical referrals. While audiology is a branch of science that studies and researches hearing, balance, and related disorders.

An oncologist is a specialised doctor responsible for providing medical care to patients diagnosed with cancer. He or she uses several therapies to control the cancer and its effect on the human body such as chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiation therapy and biopsy. An oncologist designs a treatment plan based on a pathology report after diagnosing the type of cancer and where it is spreading inside the body.

Are you searching for an ‘Anatomist job description’? An Anatomist is a research professional who applies the laws of biological science to determine the ability of bodies of various living organisms including animals and humans to regenerate the damaged or destroyed organs. If you want to know what does an anatomist do, then read the entire article, where we will answer all your questions.

For an individual who opts for a career as an actor, the primary responsibility is to completely speak to the character he or she is playing and to persuade the crowd that the character is genuine by connecting with them and bringing them into the story. This applies to significant roles and littler parts, as all roles join to make an effective creation. Here in this article, we will discuss how to become an actor in India, actor exams, actor salary in India, and actor jobs.

Individuals who opt for a career as acrobats create and direct original routines for themselves, in addition to developing interpretations of existing routines. The work of circus acrobats can be seen in a variety of performance settings, including circus, reality shows, sports events like the Olympics, movies and commercials. Individuals who opt for a career as acrobats must be prepared to face rejections and intermittent periods of work. The creativity of acrobats may extend to other aspects of the performance. For example, acrobats in the circus may work with gym trainers, celebrities or collaborate with other professionals to enhance such performance elements as costume and or maybe at the teaching end of the career.

Video Game Designer

Career as a video game designer is filled with excitement as well as responsibilities. A video game designer is someone who is involved in the process of creating a game from day one. He or she is responsible for fulfilling duties like designing the character of the game, the several levels involved, plot, art and similar other elements. Individuals who opt for a career as a video game designer may also write the codes for the game using different programming languages.

Depending on the video game designer job description and experience they may also have to lead a team and do the early testing of the game in order to suggest changes and find loopholes.

Radio Jockey

Radio Jockey is an exciting, promising career and a great challenge for music lovers. If you are really interested in a career as radio jockey, then it is very important for an RJ to have an automatic, fun, and friendly personality. If you want to get a job done in this field, a strong command of the language and a good voice are always good things. Apart from this, in order to be a good radio jockey, you will also listen to good radio jockeys so that you can understand their style and later make your own by practicing.

A career as radio jockey has a lot to offer to deserving candidates. If you want to know more about a career as radio jockey, and how to become a radio jockey then continue reading the article.

Choreographer

The word “choreography" actually comes from Greek words that mean “dance writing." Individuals who opt for a career as a choreographer create and direct original dances, in addition to developing interpretations of existing dances. A Choreographer dances and utilises his or her creativity in other aspects of dance performance. For example, he or she may work with the music director to select music or collaborate with other famous choreographers to enhance such performance elements as lighting, costume and set design.

Social Media Manager

A career as social media manager involves implementing the company’s or brand’s marketing plan across all social media channels. Social media managers help in building or improving a brand’s or a company’s website traffic, build brand awareness, create and implement marketing and brand strategy. Social media managers are key to important social communication as well.

Photographer

Photography is considered both a science and an art, an artistic means of expression in which the camera replaces the pen. In a career as a photographer, an individual is hired to capture the moments of public and private events, such as press conferences or weddings, or may also work inside a studio, where people go to get their picture clicked. Photography is divided into many streams each generating numerous career opportunities in photography. With the boom in advertising, media, and the fashion industry, photography has emerged as a lucrative and thrilling career option for many Indian youths.

An individual who is pursuing a career as a producer is responsible for managing the business aspects of production. They are involved in each aspect of production from its inception to deception. Famous movie producers review the script, recommend changes and visualise the story.

They are responsible for overseeing the finance involved in the project and distributing the film for broadcasting on various platforms. A career as a producer is quite fulfilling as well as exhaustive in terms of playing different roles in order for a production to be successful. Famous movie producers are responsible for hiring creative and technical personnel on contract basis.

Copy Writer

In a career as a copywriter, one has to consult with the client and understand the brief well. A career as a copywriter has a lot to offer to deserving candidates. Several new mediums of advertising are opening therefore making it a lucrative career choice. Students can pursue various copywriter courses such as Journalism , Advertising , Marketing Management . Here, we have discussed how to become a freelance copywriter, copywriter career path, how to become a copywriter in India, and copywriting career outlook.

In a career as a vlogger, one generally works for himself or herself. However, once an individual has gained viewership there are several brands and companies that approach them for paid collaboration. It is one of those fields where an individual can earn well while following his or her passion.

Ever since internet costs got reduced the viewership for these types of content has increased on a large scale. Therefore, a career as a vlogger has a lot to offer. If you want to know more about the Vlogger eligibility, roles and responsibilities then continue reading the article.

For publishing books, newspapers, magazines and digital material, editorial and commercial strategies are set by publishers. Individuals in publishing career paths make choices about the markets their businesses will reach and the type of content that their audience will be served. Individuals in book publisher careers collaborate with editorial staff, designers, authors, and freelance contributors who develop and manage the creation of content.

Careers in journalism are filled with excitement as well as responsibilities. One cannot afford to miss out on the details. As it is the small details that provide insights into a story. Depending on those insights a journalist goes about writing a news article. A journalism career can be stressful at times but if you are someone who is passionate about it then it is the right choice for you. If you want to know more about the media field and journalist career then continue reading this article.

Individuals in the editor career path is an unsung hero of the news industry who polishes the language of the news stories provided by stringers, reporters, copywriters and content writers and also news agencies. Individuals who opt for a career as an editor make it more persuasive, concise and clear for readers. In this article, we will discuss the details of the editor's career path such as how to become an editor in India, editor salary in India and editor skills and qualities.

Individuals who opt for a career as a reporter may often be at work on national holidays and festivities. He or she pitches various story ideas and covers news stories in risky situations. Students can pursue a BMC (Bachelor of Mass Communication) , B.M.M. (Bachelor of Mass Media) , or MAJMC (MA in Journalism and Mass Communication) to become a reporter. While we sit at home reporters travel to locations to collect information that carries a news value.

Corporate Executive

Are you searching for a Corporate Executive job description? A Corporate Executive role comes with administrative duties. He or she provides support to the leadership of the organisation. A Corporate Executive fulfils the business purpose and ensures its financial stability. In this article, we are going to discuss how to become corporate executive.

Multimedia Specialist

A multimedia specialist is a media professional who creates, audio, videos, graphic image files, computer animations for multimedia applications. He or she is responsible for planning, producing, and maintaining websites and applications.

Quality Controller

A quality controller plays a crucial role in an organisation. He or she is responsible for performing quality checks on manufactured products. He or she identifies the defects in a product and rejects the product.

A quality controller records detailed information about products with defects and sends it to the supervisor or plant manager to take necessary actions to improve the production process.

Production Manager

A QA Lead is in charge of the QA Team. The role of QA Lead comes with the responsibility of assessing services and products in order to determine that he or she meets the quality standards. He or she develops, implements and manages test plans.

Process Development Engineer

The Process Development Engineers design, implement, manufacture, mine, and other production systems using technical knowledge and expertise in the industry. They use computer modeling software to test technologies and machinery. An individual who is opting career as Process Development Engineer is responsible for developing cost-effective and efficient processes. They also monitor the production process and ensure it functions smoothly and efficiently.

AWS Solution Architect

An AWS Solution Architect is someone who specializes in developing and implementing cloud computing systems. He or she has a good understanding of the various aspects of cloud computing and can confidently deploy and manage their systems. He or she troubleshoots the issues and evaluates the risk from the third party.

Azure Administrator

An Azure Administrator is a professional responsible for implementing, monitoring, and maintaining Azure Solutions. He or she manages cloud infrastructure service instances and various cloud servers as well as sets up public and private cloud systems.

Computer Programmer

Careers in computer programming primarily refer to the systematic act of writing code and moreover include wider computer science areas. The word 'programmer' or 'coder' has entered into practice with the growing number of newly self-taught tech enthusiasts. Computer programming careers involve the use of designs created by software developers and engineers and transforming them into commands that can be implemented by computers. These commands result in regular usage of social media sites, word-processing applications and browsers.

Information Security Manager

Individuals in the information security manager career path involves in overseeing and controlling all aspects of computer security. The IT security manager job description includes planning and carrying out security measures to protect the business data and information from corruption, theft, unauthorised access, and deliberate attack

ITSM Manager

Automation test engineer.

An Automation Test Engineer job involves executing automated test scripts. He or she identifies the project’s problems and troubleshoots them. The role involves documenting the defect using management tools. He or she works with the application team in order to resolve any issues arising during the testing process.

Applications for Admissions are open.

Aakash iACST Scholarship Test 2024

Get up to 90% scholarship on NEET, JEE & Foundation courses

SAT® | CollegeBoard

Registeration closing on 19th Apr for SAT® | One Test-Many Universities | 90% discount on registrations fee | Free Practice | Multiple Attempts | no penalty for guessing

JEE Main Important Chemistry formulas

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Chemistry formulas, equations, & laws of class 11 & 12th chapters

Resonance Coaching

Enroll in Resonance Coaching for success in JEE/NEET exams

TOEFL ® Registrations 2024

Thinking of Studying Abroad? Think the TOEFL® test. Register now & Save 10% on English Proficiency Tests with Gift Cards

ALLEN JEE Exam Prep

Start your JEE preparation with ALLEN

Everything about Education

Latest updates, Exclusive Content, Webinars and more.

Download Careers360 App's

Regular exam updates, QnA, Predictors, College Applications & E-books now on your Mobile

Cetifications

We Appeared in

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences