- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.7: Leadership and the Qualities of Political Leaders

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 128427

- Robert W. Maloy & Torrey Trust

- University of Massachusetts via EdTech Books

Standard 4.7: Leadership and the Qualities of Political Leaders

Apply the knowledge of the meaning of leadership and the qualities of good leaders to evaluate political leaders in the community, state, and national levels. (Massachusetts Curriculum Framework for History and Social Studies) [8.T4.7]

FOCUS QUESTION: What is effective political leadership?

Standard 4.7 addresses political leadership and the qualities that people seek in those they choose for leadership roles in democratic systems of government.

Leadership involves multiple skills and talents. It has been said that an effective leader is someone who knows "when to lead, when to follow, and when to get out of the way" (the phrase is attributed to the American revolutionary Thomas Paine). In this view, effective leaders do much more than give orders. They create a shared vision for the future and viable strategic plans for the present. They negotiate ways to achieve what is needed while also listening to what is wanted. They incorporate individuals and groups into processes of making decisions and enacting policies by developing support for their plans.

Different organizations need different types of leaders. A commercial profit-making firm needs a leader who can grow the business while balancing the interests of consumers, workers, and shareholders. An athletic team needs a leader who can call the plays and manage the personalities of the players to achieve success on the field and off it. A school classroom needs a teacher-leader who knows the curriculum and pursues the goal of ensuring that all students can excel academically, socially, and emotionally. Governments—local, state, and national—need political leaders who can fashion competing ideas and multiple interests into policies and practices that will promote equity and opportunity for all.

The Massachusetts learning standard on which the following modules are based refers to the "qualities of good leaders," but what does a value-laden word like "good" mean in political and historical contexts? "Effective leadership" is a more nuanced term. What is an effective political leader? In the view of former First Lady Rosalynn Carter, "A leader takes people where they want to go. A great leader takes people where they don't necessarily want to go, but ought to be."

Examples of effective leaders include:

- Esther de Berdt is not a well-known name, but during the Revolutionary War, she formed the Ladies Association of Philadelphia to provide aid (including raising more than $300,000 dollars and making thousands of shirts) for George Washington's Continental Army.

- Mary Ellen Pleasant was an indentured servant on Nantucket Island, an abolitionist leader before the Civil War and a real estate and food establishment entrepreneur in San Francisco during the Gold Rush, amassing a fortune of $30 million dollars which she used to defend Black people accused of crimes. Although she lost all her money in legal battles and died in poverty, she is recognized today as the " Mother of Civil Rights in California ."

- Ida B. Wells , born a slave in Mississippi in 1862, began her career as a teacher and spent her life fighting for Black civil rights as a journalist, anti-lynching crusader and political activist. She was 22 years-old in 1884 when she refused to give up her seat to a White man on a railroad train and move to a Jim Crow car, for which she was thrown off the train. She won her court case, but that judgement was later reversed by a higher court. She was a founder of National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored Women.

- Sylvia Mendez , the young girl at the center of the 1946 Mendez v. Westminster landmark desegregation case; Chief John Ross , the Cherokee leader who opposed the relocation of native peoples known as the Trail of Tears; and Fred Korematsu , who challenged the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, are discussed elsewhere in this book.

The INVESTIGATE and UNCOVER modules for this topic explore five more women and men, straight and gay, Black and White, who demonstrated political leadership throughout their lives. ENGAGE asks who would you consider are the most famous Americans in United States history?

Modules for this Standard Include:

- INVESTIGATE: Frances Perkins, Margaret Sanger, and Harvey Milk - Three Examples of Political Leadership

- UNCOVER: Benjamin Banneker, George Washington Carver, and Black Inventors' Contributions to Math, Science, and Politics

- MEDIA LITERACY CONNECTIONS: Celebrities' Influence on Politics

4.7.1 INVESTIGATE: Frances Perkins, Margaret Sanger, and Harvey Milk - Three Examples of Political Leadership

Three individuals offer ways to explore the multiple dimensions of political leadership and social change in the United States: one who was appointed to a government position, one who assumed a political role as public citizen, and one who was elected to political office.

- Appointed: An economist and social worker, Frances Perkins was appointed as Secretary of Labor in 1933, the first woman to serve in a President Cabinet.

- Assumed: Margaret Sanger was a nurse and political activist who became a champion of reproductive rights for women. She opened the first birth control clinic in Brooklyn in 1916.

- Elected: Harvey Milk was the first openly gay elected official in California in 1977. He was assassinated in 1978. By 2020, a LGBTQ politician has been elected to a political office in every state.

Frances Perkins and the Social Security Act of 1935

An economist and social worker, Frances Perkins was Secretary of Labor during the New Deal—the first woman member of a President’s Cabinet. Learn more: Frances Perkins, 'The Woman Behind the New Deal.'

Francis Perkins was a leader in the passage of the Social Security Act of 1935 that created a national old-age insurance program while also giving support to children, the blind, the unemployed, those needing vocational training, and family health programs. By the end of 2018, the Social Security trust funds totaled nearly $2.9 trillion. There is more information at the resourcesforhistoryteachers wiki page Frances Perkins and the Social Security Act .

Margaret Sanger and the Struggle for Reproductive Rights

Margaret Sanger was a women's reproductive rights and birth control advocate who, throughout a long career as a political activist, achieved many legal and medical victories in the struggle to provide women with safe and effective methods of contraception. She opened the nation's first birth control clinic in Brooklyn, New York in 1916.

Margaret Sanger's collaboration with Gregory Pincus led to the development and approval of the birth control pill in 1960. Four years later, in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), the Supreme Court affirmed women's constitutional right to use contraceptives. There is more information at the resourcesforhistoryteachers wiki page Margaret Sanger and Reproductive Rights for Women .

However, Margaret Sanger's political and public health views include disturbing facts. In summer 2020, Planned Parenthood of Greater New York said it would remove her name from a Manhattan clinic because of her connections to eugenics, a movement for selective breeding of human beings that targeted the poor, people with disabilities, immigrants and people of color.

Harvey Milk, Gay Civil Rights Leader

In 1977, Harvey Milk became the first openly gay man to be elected to public office in California by winning a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, the city’s legislative body.

To win that election, Harvey Milk successfully built a coalition of immigrant, elderly, minority, union, gay, and straight voters focused on a message of social justice and political change. He was assassinated after just 11 months in office, becoming a martyr for the gay rights movement. There is more information at a resourcesforhistoryteachers wiki page, Harvey Milk, Gay Civil Rights Leader .

Suggested Learning Activities

- What personal qualities and public actions do you think make a person a leader?

- Who do you consider to be an effective leader in your school? In a job or organization in the community? In a civic action group?

- How can you become a leader in your school or community?

Online Resources for Frances Perkins, Margaret Sanger, and Harvey Milk

- Frances Perkins , FDR Presidential Library and Museum

- Her Life: The Woman Behind the New Deal , Frances Perkins Center

- Margaret Sanger Biography , National Women's History Museum

- Margaret Sanger (1879-1966) , American Experience PBS

- Harvey Milk Lesson Plans using James Banks’ Four Approaches to Multicultural Teaching , Legacy Project Education Initiative

- Harvey Milk pages from the New York Times

- Teaching LGBTQ History and Why It Matters , Facing History and Ourselves

- Official Harvey Milk Biography

- Harvey Milk's Political Accomplishments

- Harvey Milk: First Openly Gay Male Elected to Public Office in the United States, Legacy Project Education Initiative

4.7.2 UNCOVER: Benjamin Banneker, George Washington Carver, and Black Inventors' Contributions to Math, Science, and Politics

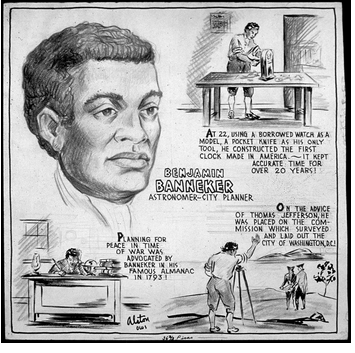

Benjamin banneker.

Benjamin Banneker was a free Black astronomer, mathematician, surveyor, author, and farmer who was part of the commission which made the original survey of Washington, D.C. in 1791.

Benjamin Banneker was "a man of many firsts" ( Washington Interdependence Council, 2017, para. 1 ). In the decades before and after the American Revolution, he made the first striking clock made of indigenous American parts, he was the first to track the 17-year locust cycle, and he was among the first farmers to employ crop rotation to improve yield.

Between 1792 and 1797, Banneker published a series of annual almanacs of astronomical and tidal information with weather predictions, doing all the mathematical and scientific calculations himself ( Benjamin Banneker's Almanac ). He has been called the first Black Civil Rights leader because of his opposition to slavery and his willingness to speak out against the mistreatment of Native Americans.

George Washington Carver

Born into slavery in Diamond, Missouri around 1864, George Washington Carver became a world-famous chemist and agricultural researcher. It is said that he single-handedly revolutionized southern agriculture in the United States, including researching more than 300 uses of peanuts, introducing methods of prevent soil depletion, and developing crop rotation methods.

A monument in Diamond, Missouri, of a statue showing Carver as a young boy, was the first ever national memorial to honor an African American ( George Washington Carver National Monument ).

Benjamin Banneker and George Washington Carver are just two examples from the long history of Black Inventors in the United States. Many of the names and achievements are not known today - Elijah McCoy, Granville Woods, Madame C J Walker, Thomas L. Jennings, Henry Blair, Norbert Rillieux, Garrett Morgan, Jan Matzeliger - but with 50,000 total patents, Black people accounted for more inventions during the period 1870 to 1940 than immigrants from every country except England and Germany ( The Black Inventors Who Elevated the United States: Reassessing the Golden Age of Invention , Brookings (November 23, 2020).

You can learn more details about these innovators at the African American Inventors of the 19th Century page on the resourcesforhistoryteachers wiki.

- Create 3D digital artifacts (using TinkerCad or another 3D modeling software ) that represent Banneker's and Carver's contributions to math, science, and politics.

- Bonus Points: Create a board (or digital) game that incorporates the 3D artifacts and educates others about Banneker and Carver.

- Using the online resources below and your own Internet research findings, write a people's history for Benjamin Banneker or George Washington Carver.

Online Resources for Benjamin Banneker, George Washington Carver and Black Inventors

- Benjamin Banneker from Mathematicians of the African Diaspora , University of Buffalo

- Mathematician and Astronomer Benjamin Banneker Was Born November 8, 1731 , Library of Congress

- Benjamin Banneker, African American Author, Surveyor and Scientist, resourcesforhistoryteachers wiki page

- George Washingto n Car ver , National Peanut Board

- George Washington Carver, State Historical Society of Missouri

- 16 Surprising Facts about George Washington Carver , National Peanut Board

4.7.3 ENGAGE: Who Do You Think Are the Most Famous Americans?

In 2007 and 2008, Sam Wineburg and a group of Stanford University researchers asked 11th and 12th grade students to write names of the most famous Americans in history from Columbus to the present day ( Wineburg & Monte-Sano, 2008 ). The students could not include any Presidents on the list. The students were then asked to write the names of the five most famous women in American history. They could not list First Ladies.

To the surprise of the researchers, girls and boys from across the country, in urban and rural schools, had mostly similar lists: Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, Harriet Tubman, Susan B. Anthony, and Benjamin Franklin were the top five selections. Even more surprising, surveys of adults from an entirely different generation produced remarkably similar lists.

The researchers concluded that a broad "cultural curriculum" conveyed through media images, corporate advertising, and shared information has a far greater effect on what is learned about people in history than do textbooks and classes in schools.

Media Literacy Connections: Celebrities' Influence on Politics

During elections, celebrities might endorse a political candidate or issue in hopes that their fans will follow in their footsteps. Oprah Winfrey's endorsement of Barack Obama for President in 2008 has been cited as the most impactful celebrity endorsement in history ( U.S. Election: What Impact Do Celebrity Endorsements Really Have? The Conversation , October 4, 2016).

Do celebrity endorsements make a real difference for voters? Researchers are undecided. In 2018, 65,000 people registered to vote in Tennessee after Taylor Swift (who had 180 million followers on Instagram) endorsed two Democratic Congressional candidates - one candidate won and the other lost. Swift's endorsement was followed by more than 212,000 new voter registrations across the country, mostly among those in the 18 to 24 age group. Perhaps what celebrities say has more impact on younger voters?

Can you think of some examples of celebrities who have shared their political views or endorsements on social media? Who are these celebrities? In what ways did they influence politics?

In these activities, you will analyze media endorsements by celebrities, and then develop a request (or pitch) to convince a celebrity to endorse your candidate for President in the next election.

- Activity 1: Analyze Celebrity Endorsements in the Media

- Activity 2: Request a Celebrity Endorsement for a Presidential Candidate

- As a class or with a group of friends, write individual lists of the 10 most famous or influential Americans in United States history.

- Explore similarities and differences across the lists.

- How many women or people of color were on the lists?

- Investigate the reasons for the similarities and differences.

- Returning to the Sam Wineburg study, "Why were Hispanic Americans, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and LGBTQ individuals left off the lists?" (see the full study here: " 'Famous Americans': The Changing Pantheon of American Heroes ")

- Research an individual's work and contributions, and in 200-250 words describe who they are, why you selected them, and what aspect of their work is important to the field. Within your description, include at least 2 links relevant to this individual ( Plan from Royal Roads University ).

Standard 4.7 Conclusion

Effective political leadership is an essential ingredient of a vibrant democracy. Unlike dictators or despots, effective leaders offer plans for change and invite people to join in and help to achieve those goals. Effective leaders work collaboratively and cooperatively, not autocratically. INVESTIGATE looked at three democratic leaders who entered political life in different ways: Frances Perkins, who was appointed to a Presidential Cabinet; Margaret Sanger, who assumed a public role as an advocate and activist; and Harvey Milk, who was elected to political office. UNCOVER reviewed the life and accomplishments of Benjamin Banneker and George Washington Carver. ENGAGE asked who people think are the most famous Americans in United States history.

Programs submenu

Regions submenu, topics submenu, strengthening australia-u.s. defence industrial cooperation: keynote panel, cancelled: strategic landpower dialogue: a conversation with general christopher cavoli, china’s tech sector: economic champions, regulatory targets.

- Abshire-Inamori Leadership Academy

- Aerospace Security Project

- Africa Program

- Americas Program

- Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy

- Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

- Asia Program

- Australia Chair

- Brzezinski Chair in Global Security and Geostrategy

- Brzezinski Institute on Geostrategy

- Chair in U.S.-India Policy Studies

- China Power Project

- Chinese Business and Economics

- Defending Democratic Institutions

- Defense-Industrial Initiatives Group

- Defense 360

- Defense Budget Analysis

- Diversity and Leadership in International Affairs Project

- Economics Program

- Emeritus Chair in Strategy

- Energy Security and Climate Change Program

- Europe, Russia, and Eurasia Program

- Freeman Chair in China Studies

- Futures Lab

- Geoeconomic Council of Advisers

- Global Food and Water Security Program

- Global Health Policy Center

- Hess Center for New Frontiers

- Human Rights Initiative

- Humanitarian Agenda

- Intelligence, National Security, and Technology Program

- International Security Program

- Japan Chair

- Kissinger Chair

- Korea Chair

- Langone Chair in American Leadership

- Middle East Program

- Missile Defense Project

- Project on Fragility and Mobility

- Project on Nuclear Issues

- Project on Prosperity and Development

- Project on Trade and Technology

- Renewing American Innovation Project

- Scholl Chair in International Business

- Smart Women, Smart Power

- Southeast Asia Program

- Stephenson Ocean Security Project

- Strategic Technologies Program

- Transnational Threats Project

- Wadhwani Center for AI and Advanced Technologies

- All Regions

- Australia, New Zealand & Pacific

- Middle East

- Russia and Eurasia

- American Innovation

- Civic Education

- Climate Change

- Cybersecurity

- Defense Budget and Acquisition

- Defense and Security

- Energy and Sustainability

- Food Security

- Gender and International Security

- Geopolitics

- Global Health

- Human Rights

- Humanitarian Assistance

- Intelligence

- International Development

- Maritime Issues and Oceans

- Missile Defense

- Nuclear Issues

- Transnational Threats

- Water Security

A New Political Leadership for the Twenty-First Century

Photo: RAUL ARBOLEDA/AFP/Getty Images

Table of Contents

Report by Marcos Peña

Published December 8, 2021

Available Downloads

- Download the Full Report 121kb

- Download the Spanish Report 154kb

Rethinking the Personal Dimension of Politics

This work comes from a personal search. In December 2019, after 16 years in public office, I finished my job as chief of cabinet of ministers for President Mauricio Macri’s administration in Argentina. At 42 years old, and after many years of being at the political forefront, I was drained and decided to step back a bit to be able to have perspective and process the lived experience.

I had the invaluable collaboration of Alberto Lederman, an Argentine consultant on leadership and organizations, for that process. He is a wise man who taught me a lot on the importance of the human and personal dimension of leadership. I learned many of the ideas that I write in this paper from him, his experience, his perspective, and from the many conversations we have had in the past three years. He also helped me understand that in order to help others you must take care of yourself.

At first, I organized the task by writing about and reviewing the political process that had taken us from the creation of a new local party in 2003 in the city of Buenos Aires to governing the country. What had we learned? What had gone well and what hadn’t? What were the innovations that we were able to implement and what were the changes that were not achieved? Finally, I wanted to try to understand clearly why we could not win the reelection, frustrating a transformation process that had generated great hope in the country and in the region.

As I progressed with that task, I did more personal work, trying to better understand what I had felt and lived in those years. I wanted to avoid remaining trapped in the intensity of what I had experienced, as I saw it happen many times to those who held an important position and remained stuck in that experience.

One of the lessons learned took place when I asked people I had worked with to help me take a closer look at things I had to work on or that stood out. I had nearly 50 conversations asking feedback on a more personal level, and what struck me was how emotional issues and interpersonal bonding always came up. What each one took away from the shared experience were hopes, enthusiasm, frustrations, disagreements, joy, and sadness. Of course, political, managerial, or ideological discussions also arose, but they were always within the framework of what they experienced on a personal level.

What I learned confirmed that there was something worth exploring further. I began to work more systematically to understand the personal and human dimensions of leadership. I was finding valuable people and tools that could be useful for other leaders who would face challenges like those I had faced. And I saw that there was a different perspective of the world of leadership to explore—different from the more rational one in which I had been trained, first as a graduate student in political science, then as a politician. That process outlined the path that led to this paper.

The Personal Dimension of Politics

In general, the formation of a politician is rational, and he tends to omit his personhood as his career progresses. This omission takes him away from a more comprehensive look at himself, generating potential mental, physical, and emotional health problems that end up amplifying self-reliance and the difficulty of making emotional connections.

As you grow in your political career and assume more tasks, a defense mechanism is triggered that takes you to survival mode, a state that each person lives differently, but that generally puts you on the defensive—more disconnected from emotions, less able to empathize with other people. Living in permanent conflict, defending positions, making decisions, and receiving criticism and attacks leads to an addictive model where tactical operations become the habitual drug.

In general, the formation of a politician is rational, and he tends to omit his personhood as his career progresses.

Added to this complicated dynamic are the trappings of fame and public exposure. Being well known in a hyper-communication society like the one we live in is something that has an impact on the individual and their family. It is neither neutral nor natural. It restricts your freedom, it has an impact on the people around you, and it redefines relationships. In short, it increases loneliness and unleashes those defense mechanisms. But nobody prepares you for that. It is an omitted phenomenon, even though it would seem to be quite obvious that by dedicating oneself to politics, one ends up becoming well known.

Political science in general does not focus on understanding fame and how it impacts a person. It is also something that has changed significantly in recent years with the advancement of digital communication. Let’s think about how smartphones have become widespread in the last 10 years, giving rise to platforms such as YouTube, WhatsApp, Facebook, and Instagram or platforms such as Netflix and Spotify that did not exist until relatively recently. That led me to try to better understand other worlds where similar phenomena occur, such as the worlds of sports and entertainment. I found many parallels, many similar situations, and many metaphors that could help me better understand the challenges I had experienced. But it also allowed me to see how the new communications reality is impacting these worlds, since today’s artists and athletes also receive demands from society that they have not been prepared for.

Understanding the world of sports provides insight into what it takes to perform at the highest levels, even in other fields. Looking at the political experience from the person’s perspective—the individual’s perspective—and not just from the ideological, intellectual, or institutional perspective allowed me to see that there were many tools available that were not being leveraged and that could be very useful. I also saw that there were new realities that required new approaches.

I also looked for experiences in the business world, where there are many biographies and a large amount of content dedicated to rethinking how human capital is organized and how it is developed. It is clearly seen there how the old vertical and pyramidal corporate model is being overcome by a more horizontal and collaborative leadership. Today’s most dynamic companies invest time and resources thinking about these issues, something very difficult to find in the world of politics.

Another Pandemic: A Crisis of Leadership and Representation

In parallel, I was fortunate to be able to work with political leaders from several Latin American countries, generally helping them on issues of strategic communication and electoral campaign management—issues that I have been working on for many years.

That regional perspective allowed me to see firsthand the loneliness and lack of tools that many young and emerging leaders experience across the continent. The muscles that end up being overdeveloped are narcissism and self-sufficiency—not as a defect, but as a survival tool. They are all overwhelmed, trying to lead with a very weak political institutional framework, like boats in the middle of a rough sea.

There was little point in asking them to think strategically, to design a more horizontal and empathetic leadership, to allow for team building, or to think long term, because they were basically trying to survive from day to day.

In moments of euphoria when they had been doing well in their circumstances, their self-sufficiency increased; in moments of decline and crisis, depression and paralysis were enhanced. But this is not an individual problem; it is more structural in nature. Often, this goes unnoticed because the problem of leadership is not usually looked at from a broader perspective, amplifying the feeling that it is something that only affects one’s own country.

The Covid-19 pandemic acted as an accelerator for this trend, exponentially increasing complexity and uncertainty and making the task much trickier due to the difficulty of drawing a roadmap and due to the impact on the individual’s day-to-day life. In addition, the explosion of the virtual world strengthened the trend toward a life without intermediation and with fewer meeting spaces, where it is more difficult for us to find ourselves.

This also exposed how limited our national and international institutions have become in tackling global issues. As Yuval Noah Harari suggests in his book 21 Lessons for the 21st Century , we must think of institutional solutions that can face global issues more effectively than our current solutions. Think of “the connection between the great revolutions of our era and the inner life of individuals.” That is why he recommends meditation. Think of the global and the personal as two scales for the twenty-first century.

Updating Political Leadership

Barbara Tuchman asked how good human beings are at leading us in her book March of Folly , telling us: “A remarkable phenomenon throughout history beyond place or period is the execution of policies from governments that are contrary to their own interests. Humanity, it would seem, performs worse on government than on almost any other human activity. In this realm, wisdom, defined as the exercise of judgment based on experience, common sense, and available information, is less operative and more thwarted than it should be.”

Historically, political leadership was embodied by people who based their power on not being equal to the rest of human beings. Kings, emperors, and chiefs alike were characterized by being superhuman—beings who bordered on the divine or who were chosen by the deities. The architecture of power reflects that distance, which hid and alienated the leader from his subjects. It was a vertical and highly personalistic power.

Over time, that type of leadership was questioned, and a more rational—and, in some parts of the world, more democratic—leadership was sought, although we still see personalist and populist charismatic leaders persist today. We also see leaders who are deified and who did not have this characteristic but who, after their death, are taken to the cult of personality, distancing them from their human condition.

In the book In Sickness and in Power , David Owen shows us the reality behind this deification, narrating in medical-professional detail the mental and physical health problems that the great leaders of the twentieth century had, especially the so-called Hubris Syndrome . He defines it as a temporary disorder suffered by people with power, characterized by the exaltation of the ego, excessiveness, contempt for the opinions of others, loss of contact with reality, and other problems that lead to self-destruction.

This conception of leadership also has another very complex side effect: it scares many people away from the possibility of becoming leaders. If you think that to be a leader you must be a chosen one, somebody superior from the rest, then it’s probable you will exclude yourself from that category. Understanding that the heroes, the founding fathers, and the great leaders of humanity were and are as human as everyone else is key.

In Latin America, this vertical tradition was combined with the culture of the caudillo, which combines religious elements with a power based on being the incarnation of the people. That leadership style always had dramatic aspects of sacrifice and of express omission of oneself for the “love of the people.” The leader never retires; he is always willing to sacrifice longer for the people. It does not occur to him to train new people and he can justify corruption or any abuse of power in his redemptive mission.

This tradition coexisted with a more liberal political culture, which promoted a leadership more attuned with that of the Saxon countries: institutional and republican. The difficulty many of these leaders have is that they tend to have a technocratic or bureaucratic background, but little capacity to connect emotionally with the population. A leader’s training may be intellectual, and his experience may come from management, but that does not necessarily give him the tools for emotional bonding.

In Latin America, this vertical tradition was combined with the culture of the caudillo, which combines religious elements with a power based on being the incarnation of the people. That leadership style always had dramatic aspects of sacrifice and of express omission of oneself for the “love of the people.”

Both are vertical models, and if we look at the last decades in the region, we will see them competing with different levels of success depending on the country. But over time, a crisis of representation has grown in much of the continent. Societies that have radically changed the way they connect, consume, and inform themselves must choose between political leaders who continue to try to replicate outdated formulas and emerging leaders who are unprepared or opportunistic, building on people’s resentment and disenchantment.

Resentment and disenchantment exacerbate the problem, since many see political leaders at best as a privileged group unable to solve problems and at worst as corrupt individuals who take advantage of and abuse power. So, any remuneration is going to be too high, any leisure is going to be seen as superfluous, any weakness as inability. It is a model destined to fail because nothing good can come out of that dynamic.

The crisis of political representation is not a problem of demand—understood as what citizens expect from leaders—but rather a problem stemming from the difficulties of the leaders. That is why we should rethink the leadership model. We need to prepare our politicians not only in ethical and moral values and in management capabilities, but also in understanding the world. We must also help them to fully know themselves; take care of themselves; and prepare mentally, emotionally, and physically for the hyper-demanding task of ruling without losing touch with their humanity, thus reducing the risk of Hubris Syndrome.

In this context of volatility, uncertainty, and complexity, we should look at the human dimension, seeing empathy and an emotional bond with the population as a basic and necessary condition. That requires moving away from caudillista, messianic, charismatic, or technocratic leadership models. Awareness of your humanity and connection with others is a path that helps prevent the evils of abuse of power or bad rulers. In ancient Rome, the Caesars had a slave whose task was to whisper in their ear that they were mortal. Since the existence of man, there has been insight into how power impacts the individual, how to prevent the madness of power, and how to ensure good rulers.

We should also think of a more collective and group dimension to leadership, understanding that we should not expect a single person to effectively manage so much complexity. We should look at the models of groups, teams, and orchestras, where there is someone who leads more like a coordinator of a team of peers, not as a messianic leader. This leadership model can lead us to a breakthrough in thinking of ways for the electoral political supply to rest not on a single person, but rather on teams that put shared work as a value before society.

Political leadership should be designed in such a way as to reduce the risks of self-sufficiency, of the group mentality that usually surrounds personalistic leadership, and of unsustainability due to the concentration of risks assumed by those who excessively become the decisionmakers. This will make room for the emotional component that reduces the dehumanization produced by the wear and tear of the exercise of power.

The institutional design of the state and political organizations is old and obsolete, making it difficult to think about this different type of leadership. The very architecture of government buildings reflects a culture not even from the twentieth century, but often from the nineteenth century or earlier. All the symbols of power that continue to be used, especially in the international relations protocol, are in dissonance with a world that has advanced to another place. The current leadership model is pompous, vertical, cold, and distant. Presidents spend many hours and days in ceremonies that are often seen by citizens as archaic and somewhat ridiculous dances.

That is why it becomes so important to think about how to help leaders get out of that model. Otherwise, it is very difficult to maintain a connection from that place to a society that lives in another time and in another world.

Who Takes Care of Political Leaders?

As the crisis in representation and political parties escalates, there is no institution today that is well positioned to work on the training, development, and care of the human capital dedicated to political leadership.

Civil society organizations, academic institutions, foundations, and think tanks that work to support political training have a specific approach, which is important in that it provides tools, but it cannot replace day-to-day or long-term strategies.

It would not be enough for a player of any elite sport to take a clinic for a couple of weeks a year to train and educate himself, nor would it help him if his training only took place during his four years at a university. There’s no question in worlds such as high-performance sports that for a person to perform at their maximum potential, certain things are required in addition to their talent and will: training, taking care of their physical body, working on their mental health, having a team that accompanies the athlete, and using technology that allows for performance evaluation. The team is led by a coach who is accompanied by specialists in various disciplines, such as nutrition, physical preparation, psychological support, and technology.

There is none of that in politics today because we do not conceive of it as a high-performance activity and because there are no institutions prepared to carry out this task.

That leads one to wonder why the health of leaders is still a taboo subject. In all countries, there has been a push to request affidavits of candidates’ net worth and assets, but the need to have affidavits of their mental and physical health is rarely considered. A soccer player must have a medical checkup before joining a club, but a minister joins a government without anyone knowing if he is healthy or has any illnesses. A leader’s health is thought to be a matter of privacy, but all other areas of his life are expected to be transparent and public. What does that tell us about how we conceive of leadership? What impact would it have for a politician to acknowledge that he suffers from problems with alcoholism, anxiety, eating disorders, insomnia, or panic attacks? Would it distance him from the general public, or would it connect him with the reality that a large part of society experiences?

If we do not prepare and support our leaders, we cannot expect to have good results. One must wonder why there is so much investment, technology, and science devoted to training and caring for people who are dedicated to other tasks that have much less impact on our society, but we do not do the same with the people who take on the task of political leadership.

Some may argue that this training task is the responsibility of each person who wants to run for a leadership position, and that this selection will be done through elections. But I contend that it is a serious mistake to think that coming to power is sufficient evidence of one’s ability and preparation.

The citizen chooses among people who are willing to enter politics and who combine virtues and abilities, but who will never be able to embody all of them. In addition, each citizen prioritizes different criteria when choosing. For some, the most important thing is that a political leader be a person of integrity; for others, that they have management skills; for others, that they be a person sensitive to their problems; or perhaps, simply, that they channel a citizen’s anger or resentment.

But even if one assumes that the selection method is effective for choosing the most suitable people to lead, leaders come to power through elections with weak political parties, rules and institutions riddled with political struggles, and a skeptical citizenry with unresolved high demands. They will take their public position with lower salaries than the ones they could have in the private sector, with high personal and family exposure, with the certainty of having legal problems in the future—sometimes even running the risk of going to jail—and with too few tools to meet the demands made upon them. It is natural, then, that in this context the leader does not perform at his best and that defense mechanisms are built to survive.

Therefore, it is an issue of efficiency, which leads us to think that politicians should be trained and supported in a different way. It does not make sense to think that we can have good results in our societies without it. It is like thinking that we will win a soccer world cup or a gold medal in the Olympic games without all the preparation and the coaching and training of these athletes.

The intention of this work is not to close the debate by proposing a comprehensive solution. It seeks to alert us to the problem so that we become aware and work creatively, thinking of possible solutions. We cannot think that we will have healthy leadership with leaders who are not healthy themselves, and it is impossible to think that they will be if they do not have the tools and the help to go through the experience of handling power.

Expanding the Toolbox

The following are nine dimensions that should be included in a political leader’s toolbox. Not intended to be exhaustive academic research on each topic, the objectives of this section are: (1) that it serves as a foundation on which to build a syllabus, whose objective is to create awareness and provide concrete tools that can become habits; (2) that it provides a self-examination reference tool for those in a leadership role to use; and (3) that it becomes the basis of a permanent initiative, thinking about the design of support teams that can support the leaders at each stage of their career.

All these issues feed and complement each other and offer different ways to help leaders be more connected with their humanity and with their emotions and, thus, be more effective in their role and more sustainable in the long term.

- The Emotional Side: Mental Health

It is essential to work on self-awareness, mental health care, connection with emotions, and psychological support in an activity as demanding as politics. Without this work, the chances of being a healthy and sustainable person after many years in leadership tasks are almost nil. Exhaustion and burnout, depression, panic attacks, or more complex disorders haunt anyone who is exposed to so much stress.

Interestingly, though the way power sickens has been studied throughout history, there are not many cases of political leaders who have recognized that they suffer or suffered from mental health problems. This is an anachronism in a time where there is a growing awareness of the importance of mental health among the general population and where it is no longer a taboo, but something that everyone must take care of.

But beyond the possible diseases or disorders that a politician can live with, it is necessary to work on self-awareness to understand those things that impacted, shaped, and conditioned their lives.

According to Alberto Lederman, an Argentine business management expert: “All leaders have some trauma. I don’t know one that doesn’t. My theory, in short, is that lust for power is a trauma response. Because, just as not everyone needs to get high, not everyone is interested in power. You must have a biographical trauma to do certain things. You must have motive, compelling reasons to aspire to power, to want to make history, to seek prominence. If there is no conflict, there are no demands for redress.”

As discussed before, preventing the effects of Hubris Syndrome is key, and for that, awareness and professional help are required. Working with a mental health professional is a basic necessity for someone who is in a context of permanent stress.

In addition, there are other factors to consider, such as the impact of stress on our capacity for emotional bonding. Aggravated by permanent conflict, exposure, and personal attacks, the mind acts in self-defense by closing itself off. This decreases empathy just when it is needed most—when one is exercising a political leadership role in a government or in some other political office.

There is also abundant evidence on the usefulness of meditation as a practice that helps in self-knowledge, connection with the present, mental health, and reduction of stress and anxiety, among many other benefits.

Neuroscience has advanced in recent decades, and it can provide us with important self-awareness tools to know how our brain works, how it interacts with the rest of our body, and how it is affected by the stress context in which we move.

The spiritual and religious dimension also constitutes an important element to consider. It is important to understand how it shapes our beliefs and values, our thought process, our self-knowledge practices, and our relationship with transcendence. Although it is a more private dimension, omitting it from the analysis implies leaving out a dimension that occupies an important part of people’s lives.

- The Body: High Performance

It is known that the body needs to breathe, sleep, eat, and train in order to perform at its best. However, most of us don’t know how to do these things well, and what we do know is often put aside in times of high demand.

The case of political leaders is more dramatic, as Pepe Sánchez— former NBA basketball player and Olympic medalist, who is today dedicated to thinking about well-being and high performance—says, “The human body is not prepared to make so many decisions and be in a context of persistent stress.” 1

There is even the myth that the best politician is the one who sacrifices himself by sleeping little and eating poorly for the well-being of the people. It goes along the same lines that a good leader is one who totally neglects himself—even a premature death consecrates him in his sacrifice for the people.

The view of political leaders taking care of their bodies becomes even more necessary when you consider that the athlete has a career limited by age, but the political leader has a much longer career. There is enormous opportunity for improvement in strengthening the entire training system, as the political experience is a longer one and therefore provides more time for learning and training. Today, we can learn from the many experiences of high-performance athletes who have prolonged their competitive lives.

Sánchez explains:

In sports we not only compete against rivals, but we also compete with stressors. My experience was that once I achieved all my sporting goals, I felt a great void. The big question is why am I doing this? You block your emotions and your vulnerability. And that happens to many high achievers, from different disciplines. They also block what happens in their bodies and their emotions; they only rely on their brain. We must train them to take a more comprehensive look at themselves. In addition, every leader should have a toolbox that includes breathing techniques, daily movement, rehydration, how to eat out, and the subject of sleep. 2

Technology today has made it more accessible than ever to have permanent measuring instruments that keep us in touch with our physical performance. Even so, it is interesting to think that it is not only about leaders doing physical activity occasionally, but also about understanding that they must be in their best shape for what is an activity of enormous physical exhaustion. Relying on professionals for support in this process is also key, because as with the mental and emotional elements, self-sufficiency can lead us to want to solve it ourselves.

The support of doctors, nutritionists, physical trainers, kinesiologists, and other specialties is important if one wants to avoid voluntarism and wants to take advantage of scientific knowledge and advances that continue to develop.

This is a subject that knows no age, gender, or physical condition limits. We all have a body, and it needs to be at its best to be effective in leadership.

- Expression: Presence and Communication

Politicians often receive specific training on expression or rhetorical techniques for going up on stage to give a speech or going on a television interview. This is based on the premise that a leader goes on stage a few times a day or a week, and then “turns off” the communication mode to continue with their rational tasks. But today, the political leader is in permanent communication mode—always exposed—and for that, he needs to prepare differently.

We can learn a lot about the emotional dimension of communication from the knowledge that has developed in the artistic world. Isabelle Anderson, a specialist in training leaders in performance, says: “You have to acquire skills to handle your expressions and your body. Many just imitate what they think is right since they did not receive any tools. This generates something disingenuous that threatens connection.” 3 It is also known that a large part of communication is transmitted through vocal and physical expression, not just words.

Anderson continues:

By analyzing human behavior, I understood that authentic presence is what resonates with any audience. But presence needs energy to reach that audience. We must teach leaders that we communicate not only with words but with the energy of presence, and this can be trained. The problem is that many people climb up the ladder without the proper training and mental preparation to communicate; so, they end up appearing either contracted and less than their best selves, or imitating others and seeming fake. All this sadly prevents sincere, authentic communication. 4

This approach envisions that there must be an alignment between what one is, what one does, and what one says. It is no use thinking that one can dissociate and act out a character with the level of exposure we see today. This also requires training techniques practiced daily, as is done in physical training.

- Back to Nature: Rewilding

The day-to-day life of contemporary leaders takes place in an urban context, generally within government buildings or offices; while traveling by car, helicopter, or airplane; in brief outdoor activities; or in event rooms—in most contexts, often surrounded by security agents.

This greatly limits the contact leaders can have with nature, and therefore the connection with their own natural dimension. As much as we forget, human beings are part of the animal kingdom, and we need to be in contact with nature.

Nature helps a leader in many ways: contact with animals boosts empathy, spending time in nature gives us perspective and makes us humbler, and it connects us with something greater than ourselves.

Tomás Ceppi, a high mountain guide, says: “You don’t get the sense of security that nature gives you anywhere else. It is a pure and transparent relationship.” 5 This interesting mountaineering metaphor can teach us a lot about leadership—from the need to have a guide who has already made the journey and can help us through it, to the extreme teamwork in which your life depends on what your partner does, to the need to prepare yourself in lower experiences before climbing high peaks, to the challenge of going down once you have reached the top, among many others. Ceppi also highlights the need to understand what your motivation is when facing such a challenge.

Everyone can find the way they best like to connect with nature. Some will choose to garden or raise pets; others will seek to climb Aconcagua’s summit or other extreme adventures. In between, there are endless options. But the important thing is to be able to reflect on the need to have systematic contact with nature, not only as a place to relax or to take vacations, but also as a place to develop empathy, humility, and perspective.

- The Avatar: Managing Character and Fame

Being famous does not come naturally and generates various impacts one should try to prepare for. The separation between the person and the character one projects is one of the greatest challenges that someone faces when they become well known. How you handle that separation will depend a lot on how you can handle criticism and attacks, but also praise and idolatry.

The more national the figure one projects, the more their experience resembles that of the most well-known celebrities, be they artists, athletes, or other popular figures. However, there is little awareness that success in political activity will lead you to become famous, and that being famous will come with loss of freedom, impact on families and your inner circle, and constant stress caused by being seen by others.

Studying and learning about the experiences of non-political personalities who have gone through the phenomenon of fame can help to manage this situation and help when processing the emotional, psychological, and practical impact that fame brings. From this point, strategies can be learned to remain in touch with reality, such as preserving intimate spaces at times when it seems necessary to open it all up all the time, as well as working with children and family to help them manage the exposure, among many other necessary tools to manage fame’s impact.

- Connecting to Our Virtual World: Digital Nutrition

As Pablo Boczkowski explains in his book, Abundance: On the Experience of Living in a World of Plenty , living in an era with an abundance of content is a challenge that generates stress and conditions our lives, especially due to the impact generated by the use of the smartphone as a kind of prosthesis of our body.

Using a nutrition analogy and our body’s diet, the cell phone is today a portal to our digital life. This digital being coexists with our biological being, but the difference is that since it is a much more recent phenomenon, how its use impacts individuals has not been studied in depth.

What we digitally consume on our cell phones (or through other screens), both in quantity and quality, affects us mentally and emotionally. Given the addictive nature of digital platforms, we are very exposed to consuming a poor-quality digital diet, investing hours of the day on them.

Social networks and digital newspapers are our main source of information, and there are no curators to help us define criteria for use.

WhatsApp and other digital messaging services put us in a state of permanent demand and force us to be connected to the screen, receiving notifications from different hierarchies all the time and participating in multiple conversations even while we are physically together. In addition, it allows direct and unlimited contact with a huge number of people who expect contact without intermediaries and without delay. Before, you could send letters to a political leader, then emails, but always with a waiting period and a possible filter, which made the demands easier to manage for the leaders. Not anymore in today’s world.

The abundance of content generates another stressor for us since we have to choose from an infinite pool of worldwide content without necessarily having clear criteria.

When in a senior leadership position, this problem can become dramatic since it is entirely up to the leader how he will use his cell phone. Often, it can end up working as an antianxiety agent, and thus end up enhancing disconnection and stress.

- Perspective: Widening the Gaze

The human brain uses sight as a reference to manage vital functions. When our visual field is reduced, the alert mode is activated because our ability to detect threats is reduced. On the contrary, when the visual field is widened, our breathing and heart rate decrease due to a decrease in danger.

In terms of our day-to-day life, if we are constantly focused on the very short term, or on the hyper-local 20 centimeters that separate us from our screen, that lack of perspective becomes a permanent stressor and our thinking skills are dulled.

Visual perspective can be trained, but it can also be worked on from the content we consume through different dimensions.

One dimension has to do with looking at other realities; seeing what is happening in other countries; ideally traveling, but if not, at least consuming content that shows us we can find solutions to problems that we think are exclusively our own, but that exist everywhere; and reading about global perspectives. These are all ways of broadening our strictly local perspective.

Timewise, both history and the future broaden our horizon and give us perspective. History, because it connects us with human nature, the challenges of power that transcend the ages, the repetition of phenomena, and the overcoming of problems. The future, because it determines the horizon. It shows us those phenomena that are to come, those that are transforming society and life, and the problems we will face that have not yet been solved.

A second dimension has to do with the issues and disciplines outside of our familiar scope. We are in a world of specialization, and it usually generates microclimates that prevent us from seeing other realities occurring in parallel to our own.

A third dimension has to do with the different social and generational realities. The fragmentation of our public conversation makes it difficult to see social situations that are out of our reach due to a generational, social, or geographic issue.

All these dimensions are ways of taking perspective, but it is very important to have a permanent discipline to be in contact with them, because our natural tendency will always be to return to our microclimate.

- The Collective: Teams, Coaches, Bands, and Orchestras

A team is the most effective way to contain egos and put them to work according to a common goal. One of the sports coaches who has developed the most concepts about teamwork, Phil Jackson, says that “good teams become great teams when their members are willing to sacrifice the ‘me’ for the ‘us’.” However, this illustration is rarely used in politics, or it is used as an expression of desire or a rhetorical device.

We can not only learn from the sports world, but also from the artistic world, where both orchestras and music groups of different genres are examples of shared work experiences in which individuals merge to achieve a common sound.

In both groupings, there is leadership and there is a support structure. They are not always successful, but almost always when they are not, it is because there isn’t an appropriate distribution of responsibilities and revenues.

A grouping will be healthy, as Jackson says, when all the parts are integrated into a whole, without losing individuality, but agreeing on a common identity and functioning.

The role of the coach or conductor has also changed over time. Today, we are beginning to understand that the vertical and authoritarian role of years past is no longer effective, and that it no longer connects with the new generations that demand a closer, horizontal, and personalized bond.

Teams also show us counterexamples, where egos and individualities tolerate each other, but clearly convey that there is no such sense of shared belonging. The similarities with the realities of political forces are very clear when viewed from this lens.

In sports, the coach plays an important role, as does the producer with artists. The role of political advisers may come to mind in association with politics, but it is not the same. Politicians’ advisers and personal staff concentrate on matters related to strategies, public policies, communication, or management, among other topics. But it is not their task to deal with the leader in his personal dimension.

- Sustainable Strategies: Think about Promotions and Demotions, Long Term

Many political careers are thought of in terms of how to move up in the hierarchical power structure, many with the ultimate dream of occupying the presidency of their country. The problem with this strategy is that what is thought of as a linear path is in fact more like a mountainous path, with hills and valleys, but above all, with great uncertainty regarding what may happen in the future.

When organizing ourselves once we arrive at the next position or we reach the highest position that we want to occupy, we lack a sustainable strategy to make a significant contribution in our lifetime. The most descriptive example of this happens with former young presidents, who finish their term and face the emptiness of not knowing what else to do and the “Chinese vase syndrome” that makes you feel that you do not know where to place yourself. On the other hand, it also happens with politicians who never retire, fighting until the end of their lives for the leading role, thus blocking the path for new generations.

Another common problem is the vacuum generated by the loss of power after having held an important position, not only in terms of adrenaline, but also sometimes in terms of economic sustainability. There is a clear risk of depression, especially if that person does not work on himself or receive adequate support.

The exercise of thinking about a leadership career in a different way from that of the classic ascension on the ladder of power helps us visualize the importance of having a shatterproof strategy, of taking care of oneself more, and of keeping perspective—so as not to go blind into a career without knowing the next steps, or so as not to become dependent on structures that end up squelching our enthusiasm, leaving us wondering why we do what we do.

Thinking of a career plan also helps us to think about a diversity of experiences and objectives, alternating periods of greater power with others of greater personal development. And it also helps every seasoned leader think that part of his task is to mentor new generations. This is something else to do after a political career besides getting caught up in the logic of the ego or the sense of irrelevance that can come with the loss of power. It is in people with experience that we can find future coaches of emerging leaders, thus ensuring the intergenerational handoff that we lack today.

Ideally, this would be part of the task of political institutions—mainly political parties—but for that, clarity is needed from their own leaders as to the need to invest time and resources in their seedbeds in a professional way.

This paper seeks to make an effective contribution to how we think about democratic political leadership and also to share personal insight as a politician so that other politicians and leaders can use it as a reference and think about how much they are taking care of themselves. Doing so can contribute to finding solutions for the legitimacy crisis that our democracies are experiencing due to a disconnect with social expectations and demands. This paradigm shift is already occurring in other fields of society, and taking it to the political arena will make the task of those in charge of solving the great problems we face more effective.

Leadership should be more human, more collaborative, more group oriented, more connected with emotions, and humbler in order to be effective. For leadership to be more effective, we should create professional structures dedicated to training, supporting, and caring for political leaders. Although it seems incredible, today there is nothing resembling such a professional structure. Political party crisis left that role vacant. We also lack full awareness of the extremely high physical, mental, and emotional demands that political activity has. Undoubtedly, it is an activity that can be thought of in relation to other high-performance activities, such as those of elite athletes. At the same time, handling fame and the demand to constantly communicate brings leaders closer to the lifestyle of the most popular artists. This reflection can also be useful for anyone who plays a leadership role in society, even if they are not engaged in politics.

Thinking about the human dimension of political leadership changes the perspective on what it means to be a leader today. It requires new insight on how this new leadership is built, how it is sustained, and how it is supported. It leads us to analyze the opportunities our democracies have to overcome their crises.

We also should rethink what tools leaders need and how to have more enduring strategies for the development of human capital. If the rest of human activities have advanced scientifically and technologically in terms of both personal care and training for high performance, we can learn a lot from them and enrich the traditional toolbox of values, integrity, ideas, and management skills.

Marcos Pe ña is an independent consultant with the Americas Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

This report is made possible through general support to the Americas Program.

This report is produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(s).

© 2021 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. All rights reserved.

Please consult the PDF for references.

Marcos Peña

Programs & projects.

Comparative Political Leadership pp 1–24 Cite as

Introduction: The Importance of Studying Political Leadership Comparatively

- Ludger Helms

950 Accesses

14 Citations

Part of the book series: Palgrave Studies in Political Leadership series ((PSPL))

There is much criticism of political leaders and leadership in contemporary political commentary and the public debate around the globe. Yet more than anything else this criticism indicates that leaders and leadership are believed to matter for the overall performance of political regimes, and the relations between different regimes. This belief seems to be largely justified. Indeed, the ever-growing complexity of politics in an increasingly interdependent world has made leadership in terms of providing direction and guidance, and devising solutions for collective problems, more important than ever.

- Prime Minister

- Political Leadership

- Transformational Leadership

- Comparative Politics

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Ahlquist, John S. and Levi, Margaret (2011) ‘Leadership: What It Means, What It Does, and What We Want to Know About It’. Annual Review of Political Science 14(1): 1–24.

Article Google Scholar

Andeweg, Rudy B. and Thomassen, Jacques J. A. (2005) ‘Modes of Political Representation: Toward a New Typology’. Legislative Studies Quarterly 30(4): 507–28.

Barber, Benjamin R. (1998) ‘Neither Leaders nor Followers: Citizenship under Strong Democracy’. In Barber, Benjamin R. (ed.), A Passion for Democracy: American Essays (Princeton: Princeton University Press), 95–110.

Google Scholar

Baylis, Thomas A. (2007) ‘Embattled Executives: Prime Ministerial Weakness in East Central Europe’. Communist and Post-Communist Studies 40(2): 81–106.

Beckett, Francis (ed.) (2011) The Prime Ministers Who Never Were (London: Biteback).

Blondel, Jean (1987) Political Leadership: Towards a General Analysis (London: Sage).

Blondel, Jean (1999) ‘Then and Now: Comparative Politics’. Political Studies 47(1): 152–60.

Blondel, Jean and Müller-Rommel, Ferdinand (eds) (1993) Governing Together: The Extent and Limits of Collective Decision-Making in Western European National Cabinets (London: Macmillan).

Blondel, Jean, Müller-Rommel and Malová, Darina (2007) Governing New European Democracies (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan).

Book Google Scholar

Boutros-Ghali, Boutros (1996) ‘Global Leadership after the Cold War’. Foreign Affairs 75(2): 86–98.

Bose, Meenekshi and Landis, Mark (eds) (2003) The Uses and Abuses of Presidential Ratings (New York: Nova Science).

Bowles, Nigel, King, Desmond S. and Ross, Fiona (2007) ‘Political Centralization and Policy Constraint in British Executive Leadership: Lessons from American Presidential Studies in the Era of Sofa Politics’. British Politics 2(3): 372–94.

Brack, Duncan (ed.) (2006) President Gore … And Other Things That Never Happened (London: Politico’s).

Brack, Duncan and Dale, Iain (eds) (2003) Prime Minister Portillo and Other Things That Never Happened: A Collection of Political Counterfactuals (London: Politico’s).

Bradford, Colin I. and Wonhyuk, Lim (eds) (2011) Global Leadership in Transition: Making the G20 More Effective and Responsive (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press).

Brooker, Paul (2009) Non-Democratic Regimes , 2nd edn (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan).

Brown, Archie (2001) ‘Introduction’. In Brown, Archie and Shevtsova, Lilia (eds), Gorbachev, Yeltsin and Putin: Political Leadership in Russia’s Transition (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace), 1–10.

Bryman, Alan (2011) ‘Research Methods in the Study of Leadership’. In Bryman, Alan, Collinson, David, Grint, Keith, Jackson, Brad and Uhl-Bien, Mary (eds), The Sage Handbook of Leadership (Los Angeles: Sage), 15–28.

Bryman, Alan, Collinson, David, Grint, Keith, Jackson, Brad and Uhl-Bien Mary (eds) (2011) The Sage Handbook of Leadership (Los Angeles: Sage).

Burns, James MacGregor (1978) Leadership (New York: Harper and Row).

Burns, James MacGregor (2003) Transforming Leadership: A New Pursuit of Happiness (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press).

Chwieroth, Jeffrey M. (2002) ‘Counterfactuals and the Study of the American Presidency’. Presidential Studies Quarterly 32(2): 293–327.

Ciulla, Joanne B. and Forsyth, Donelson R. (2011) ‘Leadership Ethics’. In Bryman, Alan, Collinson, David, Grint, Keith, Jackson, Brad and Uhl-Bien, Mary (eds), The Sage Handbook of Leadership (Los Angeles: Sage), 229–41.

Couto, Richard A. (ed.) (2010) Political and Civic Leadership: A Reference Handbook , 2 vols (Los Angeles: Sage).

Dallmayr, Fred (ed.) (2010) Comparative Political Theory: An Introduction (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan).

Elgie, Robert (2011) Semi-Presidentialism: Sub-Types and Democratic Performance (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Esaiasson, Peter and Holmberg, Sören (1996) Representation from Above: Members of Parliament and Representative Democracy in Sweden (Aldershot: Darmouth).

Garzia, Diego (2011) ‘The Personalization of Politics in Western Democracies: Causes and Consequences on Leader-Follower Relationships’. The Leadership Quarterly 22(4): 697–709.

Goethals, George R., Sorensen, Georgia J. and Burns, James MacGregor (eds) (2004) Encyclopedia of Leadership , 4 vols (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage).

Granatstein, Jack L. and Hillmer, Norman (1999) Prime Ministers: Ranking Canada’s Leaders (Toronto: Harper Collins).

Greenstein, Fred I. (1982) The Hidden-Hand Presidency: Eisenhower as Leader (New York: Basic Books).

Greenstein, Fred I. (1992) ‘Can Personality and Politics Be Studied Systematically?’ Political Psychology 13(1): 105–28.

Hartley, Jean and Benington, John (2011) ‘Political Leadership’. In Bryman, Alan, Collinson, David, Grint, Keith, Jackson, Brad and Uhl-Bien, Mary (eds), The Sage Handbook of Leadership (Los Angeles: Sage), 203–14.

Hazan, Reuven (2005) ‘The Failure of Presidential Parliamentarism: Constitutional versus Structural Presidentialization in Israel’s Parliamentary Democracy’. In Poguntke, Thomas and Webb, Paul (eds), The Presidentialization of Politics: A Comparative Study of Modern Democracies (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 287–310.

Heclo, Hugh (2009) ‘Politics as Learning’. In King, Gary, Schlozman, Kay L. and Nie, Norman H. (eds), The Future of Political Science: 100 Perspectives (New York: Routledge), 28.

Heidenheimer, Arnold J. (1961) ‘Der starke Regierungschef und das Parteien-System: “Der Kanzlereffekt” in der Bundesrepublik’. Politische Vierteljahresschrift 2(3): 241–62.

Heifetz, Ronald (2010) ‘Leadership’. In Couto, Richard A. (ed.), Political and Civic Leadership (Los Angeles: Sage), 12–23.

Helmke, Gretchen and Levitsky, Steven (2004) ‘Informal Institutions and Comparative Politics: A Research Agenda’. Perspectives on Politics 2(4): 725–39.

Helms, Ludger (2005) Presidents, Prime Ministers and Chancellors: Executive Leadership in Western Democracies (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

Helms, Ludger (2008) ‘Governing in the Media Age: The Impact of the Mass Media on Executive Leadership in Contemporary Democracies’. Government and Opposition 43(1): 26–54.

Helms, Ludger (2012a) ‘Poor Leadership and Bad Governance: Conceptual Perspectives and Questions for Comparative Inquiry’. In Helms, Ludger (ed.), Poor Leadership and Bad Governance: Reassessing Presidents and Prime Ministers in North America, Europe and Japan (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, forthcoming).

Chapter Google Scholar

Helms, Ludger (2012b) ‘Democratic Political Leadership in the New Media Age: A Farewell to Excellence?’ British Journal of Politics and International Relations 14, forthcoming.

Kane, John, Patapan, Haig and ’t Hart, Paul (eds) (2009) Dispersed Democratic Leadership: Origin, Dynamics, and Implications (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Kellerman, Barbara (2004) Bad Leadership: What It Is, How It Happens, Why It Matters (Boston: Harvard Business School Press).

Keohane, Nannerl O. (2010) Thinking about Leadership (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

Ker-Lindsay, James (2009) ‘Presidential Power and Authority’. In Ker-Lindsay, James and Faustmann, Hubertus (eds), The Government and Politics of Cyprus (Oxford: Peter Lang), 107–24.

King, Anthony (1994) ‘“Chief Executives” in Western Europe’. In Budge, Ian and McKay, David (eds), Developing Democracy: Comparative Research in Honour of J. F. P. Blondel (London: Sage), 150–63.

Körösényi, Andras (2005) ‘Political Representation in Leader Democracy’. Government and Opposition 40(3): 358–78.

Körösényi, Andras (2009) ‘Political Leadership: Classical vs. Leader Democracy’. In Femia, Joseph, Körösényi, András and Slomp, Gabriella (eds), Political Leadership in Liberal and Democratic Theory (Exeter: Imprint Academic), 79–100.

Lammers, William and Genovese, Michael (2000) The Presidency and Domestic Policy (Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly Press).

Landman, Todd (2008) Issues and Methods in Comparative Politics , 3rd edn (London and New York: Routledge).

Lipman-Blumen, Jean (2005) The Allure of Toxic Leaders (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Lord, Carnes (2003) The Modern Prince: What Leaders Need to Know Now (New Haven: Yale University Press).

Masciulli, Joseph, Molchanov, Mikhail A. and Knight, Andy W. (eds) (2009) The Ashgate Research Companion to Political Leadership (Aldershot: Ashgate).

Masciulli, Joseph, Molchanov, Mikhail A. and Knight, Andy W. (2009) ‘Political Leadership in Context’. In Masciulli, Joseph, Molchanov, Mikhail A. and Knight, Andy W. (eds), The Ashgate Research Companion to Political Leadership (Aldershot: Ashgate), 3–27.

Morozov, Evgeny (2011) ‘Whither Internet Control?’ Journal of Democracy 22(2): 62–74.

Nohria, Nitin and Khurana, Akesh (eds) (2010) Handbook of Leadership Theory and Practice (Boston: Harvard Business Press).

Nye, Joseph S. (2008) The Powers to Lead: Soft, Hard, and Smart (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

Nye, Joseph S. (2010) ‘Power and Leadership’. In Nohria, Nitin and Khurana, Akesh (eds), Handbook of Leadership Theory and Practice (Boston: Harvard Business Press), 305–32.

O’Malley, Eoin (2007) ‘The Power of Prime Ministers: Results of an Expert Survey’. International Political Science Review 28(1): 7–27.

Peele, Gillian (2005) ‘Leadership and Politics: A Case for a Closer Relationship?’ Leadership 1(2): 187–204.

Pelinka, Anton (2008) ‘Kritische Hinterfragung eines Konzepts — demokratietheoretische Anmerkungen’. In Zimmer, Annette and Jankowitsch, Regina M. (eds), Political Leadership (Berlin: Polisphere), 43–67.

Peters, B. Guy (1997) ‘The Separation of Powers in Parliamentary Systems’. In von Mettenheim, Kurt (ed.), Presidential Institutions and Democratic Politics: Comparing Regional and National Contexts (Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press), 67–83.

Peters, B. Guy (1998) Comparative Politics: Theory and Methods (Basingstoke: Macmillan).

Pfiffner, James P. (2000) Ranking the Presidents: Continuity and Volatility . Paper prepared for presentation at the Conference of Presidential Ranking, October 12, 2000, Hofstra University.