Common Sense Media

Movie & TV reviews for parents

- For Parents

- For Educators

- Our Work and Impact

Or browse by category:

- Get the app

- Movie Reviews

- Best Movie Lists

- Best Movies on Netflix, Disney+, and More

Common Sense Selections for Movies

50 Modern Movies All Kids Should Watch Before They're 12

- Best TV Lists

- Best TV Shows on Netflix, Disney+, and More

- Common Sense Selections for TV

- Video Reviews of TV Shows

Best Kids' Shows on Disney+

Best Kids' TV Shows on Netflix

- Book Reviews

- Best Book Lists

- Common Sense Selections for Books

8 Tips for Getting Kids Hooked on Books

50 Books All Kids Should Read Before They're 12

- Game Reviews

- Best Game Lists

Common Sense Selections for Games

- Video Reviews of Games

Nintendo Switch Games for Family Fun

- Podcast Reviews

- Best Podcast Lists

Common Sense Selections for Podcasts

Parents' Guide to Podcasts

- App Reviews

- Best App Lists

Social Networking for Teens

Gun-Free Action Game Apps

Reviews for AI Apps and Tools

- YouTube Channel Reviews

- YouTube Kids Channels by Topic

Parents' Ultimate Guide to YouTube Kids

YouTube Kids Channels for Gamers

- Preschoolers (2-4)

- Little Kids (5-7)

- Big Kids (8-9)

- Pre-Teens (10-12)

- Teens (13+)

- Screen Time

- Social Media

- Online Safety

- Identity and Community

Explaining the News to Our Kids

- Family Tech Planners

- Digital Skills

- All Articles

- Latino Culture

- Black Voices

- Asian Stories

- Native Narratives

- LGBTQ+ Pride

- Best of Diverse Representation List

Celebrating Black History Month

Movies and TV Shows with Arab Leads

Celebrate Hip-Hop's 50th Anniversary

What is media literacy, and why is it important?

The word "literacy" usually describes the ability to read and write. Reading literacy and media literacy have a lot in common. Reading starts with recognizing letters. Pretty soon, readers can identify words -- and, most importantly, understand what those words mean. Readers then become writers. With more experience, readers and writers develop strong literacy skills. ( Learn specifically about news literacy .)

Media literacy is the ability to identify different types of media and understand the messages they're sending. Kids take in a huge amount of information from a wide array of sources, far beyond the traditional media (TV, radio, newspapers, and magazines) of most parents' youth. There are text messages, memes, viral videos, social media, video games, advertising, and more. But all media shares one thing: Someone created it. And it was created for a reason. Understanding that reason is the basis of media literacy. ( Learn how to use movies and TV to teach media literacy. )

The digital age has made it easy for anyone to create media . We don't always know who created something, why they made it, and whether it's credible. This makes media literacy tricky to learn and teach. Nonetheless, media literacy is an essential skill in the digital age.

Specifically, it helps kids:

Learn to think critically. As kids evaluate media, they decide whether the messages make sense, why certain information was included, what wasn't included, and what the key ideas are. They learn to use examples to support their opinions. Then they can make up their own minds about the information based on knowledge they already have.

Become a smart consumer of products and information. Media literacy helps kids learn how to determine whether something is credible. It also helps them determine the "persuasive intent" of advertising and resist the techniques marketers use to sell products.

Recognize point of view. Every creator has a perspective. Identifying an author's point of view helps kids appreciate different perspectives. It also helps put information in the context of what they already know -- or think they know.

Create media responsibly. Recognizing your own point of view, saying what you want to say how you want to say it, and understanding that your messages have an impact is key to effective communication.

Identify the role of media in our culture. From celebrity gossip to magazine covers to memes, media is telling us something, shaping our understanding of the world, and even compelling us to act or think in certain ways.

Understand the author's goal. What does the author want you to take away from a piece of media? Is it purely informative, is it trying to change your mind, or is it introducing you to new ideas you've never heard of? When kids understand what type of influence something has, they can make informed choices.

When teaching your kids media literacy , it's not so important for parents to tell kids whether something is "right." In fact, the process is more of an exchange of ideas. You'll probably end up learning as much from your kids as they learn from you.

Media literacy includes asking specific questions and backing up your opinions with examples. Following media-literacy steps allows you to learn for yourself what a given piece of media is, why it was made, and what you want to think about it.

Teaching kids media literacy as a sit-down lesson is not very effective; it's better incorporated into everyday activities . For example:

- With little kids, you can discuss things they're familiar with but may not pay much attention to. Examples include cereal commercials, food wrappers, and toy packages.

- With older kids, you can talk through media they enjoy and interact with. These include such things as YouTube videos , viral memes from the internet, and ads for video games.

Here are the key questions to ask when teaching kids media literacy :

- Who created this? Was it a company? Was it an individual? (If so, who?) Was it a comedian? Was it an artist? Was it an anonymous source? Why do you think that?

- Why did they make it? Was it to inform you of something that happened in the world (for example, a news story)? Was it to change your mind or behavior (an opinion essay or a how-to)? Was it to make you laugh (a funny meme)? Was it to get you to buy something (an ad)? Why do you think that?

- Who is the message for? Is it for kids? Grown-ups? Girls? Boys? People who share a particular interest? Why do you think that?

- What techniques are being used to make this message credible or believable? Does it have statistics from a reputable source? Does it contain quotes from a subject expert? Does it have an authoritative-sounding voice-over? Is there direct evidence of the assertions its making? Why do you think that?

- What details were left out, and why? Is the information balanced with different views -- or does it present only one side? Do you need more information to fully understand the message? Why do you think that?

- How did the message make you feel? Do you think others might feel the same way? Would everyone feel the same, or would certain people disagree with you? Why do you think that?

- As kids become more aware of and exposed to news and current events , you can apply media-literacy steps to radio, TV, and online information.

Common Sense Media offers the largest, most trusted library of independent age-based ratings and reviews. Our timely parenting advice supports families as they navigate the challenges and possibilities of raising kids in the digital age.

Media Literacy

What is media Literacy?

Media literacy is the ability to understand, analyse, and create media messages. It is an evolving skill set that teachers and students must frequently encounter in the classroom, as the environments in which we consume and create media constantly change and become more complex.

Becoming media literate and teaching media literacy to students involves understanding how media messages are constructed and the techniques used to convey information and ideas.

Most importantly, it includes evaluating the credibility and reliability of media sources, recognising bias and disinformation, and understanding the impact media can have on individuals and society.

We have never lived in an era where it has been so easy to create and consume media and share it with the world as it is today; as such, we should be more enlightened about the purpose and intent of the messages being presented. Becoming media literate has never been more important as the validity and credibility of news, facts and opinions are more challenging to determine.

Students who are media literate are better equipped to critically analyze the information they receive and make informed decisions about what they believe and how they engage with media.

As teachers, it is crucial to integrate media literacy into all curriculum areas so students understand media reaches and influences us in many ways.

What skills are required to become media literate?

Becoming media literate is a process of critical thinking , healthy scepticism and understanding the factors that drive and influence the media itself. For this to occur, we have broken down these broad skills into individual components that students and teachers need to understand more deeply.

- How to analyse media messages : This involves teaching students the techniques used to inform, entertain, and persuade an audience and helping them understand the messages being conveyed.

- How to evaluate a source: When students can determine the credibility and reliability of media sources, they will make far wiser evaluations of the message and purpose of the content they consume.

- Understanding the impact of the media: What influence does the media have upon individuals, groups, and society? Teaching students why we should embrace freedom of speech and the search for truth above all else is essential. Students who understand the chaos of controlled and corrupt media approach it with a healthy level of scepticism and respect.

- Understanding how media is produced: By understanding the complexity and simplicity of producing various forms of media and sharing them with an audience, students can better determine if the media message they are consuming has been created by an agenda-driven machine or an expert in the field on a given topic.

- Knowing the difference between fact and opinion: It may seem simplistic and obvious, but when students can quickly identify if a statement is an absolute verified fact that has weight and credibility versus an opinion, it completely changes how that message is received. If students cannot separate these two areas, we educators have significantly failed them.

- Recognizing media manipulation: As terrible as it may seem, there are tens of thousands of people devoting their lives to producing propaganda, advertising, or disinformation for profit, persuasion and power every single day. Make it clear to all students that not all media should be trusted and that constant disinformation will be presented to them throughout their lives.

- Identifying and Understanding Bias: When students understand that all media has a purpose for being created and may frequently contain some degree of bias, they will look beyond simply what they are being told and ask why this message is being shared.

- Digital Literacy Skills and Media Creation: Navigating the media requires a basic understanding of technology and digital media. Providing students with the skills to effectively use technology and digital media to access, analyze, and create media messages moves them from consumers to creators with a practical and ethical understanding of the impact that their media messages can have.

TEACHING STUDENTS TO NAVIGATE THE “DISINFORMATION ERA”

Never before has it been so easy for someone, anyone, to create a message and share it with hundreds of millions of people, and even more concerning is that it has never been easier for governments to control that flow of information within their borders so that they control the narrative on every news story, and to the bend and erase history at will. We see this in action today in countries such as North Korea, China and Russia.

Disinformation is the spread of false or misleading information, often intended to control public opinion or promote a specific agenda. This problem has become increasingly prevalent in recent years and has driven a sharp rise in wild conspiracy theories, scams, and radicalization. It is essential that students are taught to navigate this complex digital landscape and identify credible sources of information.

The information era of the early 2000s has doubled down on its capacity to share and consume information through digital technology and has taken an unfortunate turn in recent years to create an information superhighway leading to a complex system of facts, opinions, bias, hatred and outright lies that are becoming increasingly difficult to navigate, especially for those who have grown up knowing nothing else but consuming their news through YouTube, Social media and the weight of opinion from social influencers outranks that of experts and proven research.

How did we get here?

The answer to that question is complex, but three critical turning points have driven us to the point at which we find ourselves.

1: The ease of content creation: This point has been covered well enough, but when anyone with the literacy skills of a child can use tools such as artificial intelligence to write a flawless 2000-word article or create a 10-minute video explaining in the style of a professional news outlet and share it with millions of people via social media via paid promotion for well under $100 this marks a clear turning point in the way we consume and create media.

To create and deliver content at this level of quality and scale only a decade earlier would have cost thousands of dollars and required far more checks and balances.

2: Algorithms determining what we consume: In the same way in which Spotify and Netflix determine what shows and music we should listen to based upon what we like, and thumbs down and so on, social media drives our consumption of news and information in the same way.

The primary intent of social media is to keep users on the platform for as long as possible regardless of what we are doing: watching videos, liking photos, or sharing posts. It doesn’t matter as long as our eyeballs remain on their platform. This allows social media outlets such as Facebook, TikTok and Instagram to sell advertising and generate billions of dollars of revenue each month.

So just as you might prefer Beiber over Beethoven on your music playlists, computer-driven algorithms will increase music that has more in common with your tastes and then remove those that do not. Undeniably, these algorithms are practical and helpful in ensuring your wants and needs are often met.

But wait; what if those algorithms effectively removed some of the most fantastic music we have ever heard? Music that might provide insight into new cultural areas puts us in a completely different headspace or opens our eyes to how other generations of music shaped the music we listen to today. What a shallow pool of musical tastes we would quickly swim in as our playlists blend into the same 100 songs we listen to all the time. Sound familiar?

So if we transfer that process of algorithms feeding us our musical tastes into how social media feeds us news and events, it is not hard to see how our biases, likes and dislikes can be quickly targeted and capitalized upon in the same way.

The more significant problem here is that if you are interested in news articles revolving around science and technology, for example, not only will you find your news feed packed with these stories exclusively with news stories of this nature, but other news events will be removed.

3: Welcome to the Algorithmic “Rabbit Hole”

The third and final act explaining how we got here is the most interesting, and we can use it as a metaphor from the story Alice in Wonderland, where she enters the rabbit hole and is transported to a surreal state of being that is both disturbing and delightful.

The “YouTube” rabbit hole is a phenomenon that demonstrates this process most effectively; how we start innocently viewing videos on a specific topic, such as “NBA highlights from the 90s”, that within 10 – 12 videos will evolve into a new stream of “recommended content” exposing “NBA Scandals”, that then leads to “Celebrity Conspiracy theories” to videos focussed on (Insert topic here) full of foul language, wild opinions, conspiracies and flat out lies.

So what is happening here, and why?

If we remember that the sole focus is to keep you on the platform so that advertising can be sold, the algorithm also knows that you will quickly tire of the same content no matter what it is. As such, it needs to provide alternate content that is in a similar vein that might also be more contentious and packed full of user feedback and comments that will create a higher level of engagement.

Effectively the algorithm needs to keep upping the “sugar, or dosage”, leading creators to create more contentious and hyperbolic even radicalized content as the race for your attention span continues to evolve. All the while, that balanced understanding of any topic is pushed to the side and eventually completely removed in favour of your new and more extreme and niche areas of interest. And this is not a healthy place for anyone to exist, especially those who are blind to the process that led them here.

This leads creators to create more wild and contentious content to draw an audience, and the cycle is repeated.

Conscious and state-controlled disinformation

Until now, we have been referring to companies using technologies to keep users engaged and persuade them to consume particular information streams for financial gain. Still, it did not take long for authoritarian countries to use this same technology to generate propaganda, erase history and sway public opinion within their own borders and those of their ideological rivals.

The big difference here is we are moving at scale from a backyard operation of disinformation to an environment in which state-sponsored projects where money, time and resources are unlimited and the capacity to create chaos on a global scale dramatically increases. Effectively enabling the process of weaponising disinformation.

Why bother trying to invade your enemy when you can far more easily create chaos and revolution amongst their own citizens in relative obscurity?

Ironically, it is the countries that value free and open media that are at the most significant risk of falling victim to disinformation attacks as there is little capacity to filter, censor and control the flow of information within social media as opposed to autocratic nations have removed the technical pathways and human rights of free press and free speech within their own borders.

A Complete Teaching Unit on Fake News

Digital and social media have completely redefined the media landscape, making it difficult for students to identify FACTS AND OPINIONS covering:

Teach them to FIGHT FAKE NEWS with this COMPLETE 42 PAGE UNIT. No preparation is required,

Media Literacy Teaching Strategies

Media literacy has become essential in the digital age, enabling individuals to navigate the vast information landscape and critically analyze media messages. Educators must equip students with the tools and knowledge necessary to become media-literate citizens. This article will explore practical strategies for teaching media literacy in the classroom, providing teachers with practical approaches to empower students to decipher and engage with media content.

In this article, we will approach the principles of media literacy from five perspectives and provide three practical examples of media literacy lessons in the classroom.

1: Build a Foundation of Media Literacy Early On

Teaching media literacy from an early age is paramount for several reasons.

Firstly, starting early allows educators to develop critical thinking skills in students . By introducing media literacy concepts and practices at a young age, students learn to question, analyze, and evaluate media content. They become more discerning consumers who can distinguish between reliable and unreliable information. Early exposure to media literacy enables students to understand the persuasive techniques, biases, and manipulative strategies employed in media, empowering them to make informed decisions about the information they encounter.

Secondly, with the pervasive presence of digital media in children’s lives, early media literacy education helps students navigate the digital landscape responsibly. Young children are increasingly exposed to online platforms, social media, and digital content. By teaching them media literacy skills, educators can guide students to critically evaluate the reliability of online information, identify potential risks and dangers, and understand the consequences of their digital actions.

Early exposure to media literacy aids in developing digital citizenship skills, enabling students to protect their privacy, engage in respectful online communication, and become critical consumers of digital content.

Moreover, early media literacy education is vital in countering misinformation and fake news. In the internet age, misinformation spreads rapidly, and young minds can be particularly vulnerable to its influence. By introducing students to fact-checking techniques, teaching them to identify credible sources, and instilling critical evaluation skills, educators empower students to actively debunk falsehoods and discern the authenticity of information.

Teaching students about media literacy from an early age is essential for fostering critical thinking skills, navigating the digital landscape responsibly, and countering misinformation. By equipping students with media literacy skills, educators empower them to become active and discerning participants in the media ecosystem.

Digital and social media have completely redefined the media landscape, making it difficult for students to identify FACTS AND OPINIONS covering:

- Radicalization

- Social Media, algorithms and technology

- Research Skills

- Fact-Checking beyond Google and Alexa

2: Promote Active Media Consumption

Encourage students to engage with media content rather than passively consume it actively. Teach them to question the sources, intentions, and biases behind the information they encounter. Encourage critical thinking by asking open-ended questions and facilitating discussions. Assign media analysis projects where students evaluate the credibility and reliability of different sources.

Let’s look at three strategies for promoting active media consumption in students.

Media Analysis and Discussion: Engage students in media analysis activities that encourage critical thinking and discussion. Give them various media examples, such as news articles, advertisements, videos, or social media posts. Guide them to identify the main message, purpose, intended audience, and persuasive techniques employed in each media piece.

Encourage students to question the credibility of the sources, evaluate the evidence provided, and consider any biases or stereotypes present. Facilitate group discussions where students can share their insights, challenge each other’s perspectives, and develop their analytical skills.

Fact-Checking and Verification: Teach students how to fact-check and verify the information they encounter in media. Introduce them to reliable fact-checking websites and tools, such as Snopes, FactCheck.org , or Google’s Fact Check Explorer.

Guide students through evaluating sources, cross-referencing information, and verifying claims made in media content. Encourage students to question the accuracy and reliability of information before accepting it as true. Provide real-world examples of misinformation or fake news stories and engage students in hands-on activities where they can fact-check and debunk false claims.

Media Creation and Critique: Encourage students to become active creators of media content and engage in self-reflection and critique.

Assign projects where students create media artifacts, such as videos, podcasts, or blog posts, focusing on a specific topic or theme. During creation, emphasize the importance of ethical media production, accurate representation, and responsible storytelling. After students complete their creations, facilitate peer feedback sessions where they can provide constructive criticism, discuss the impact of their media choices, and reflect on how their biases and perspectives may have influenced their work.

By incorporating these three approaches into media literacy education, educators can foster active media consumption skills in students. Students will develop the ability to critically analyze media messages, fact-check information, and engage responsibly with the media they encounter.

3: Develop Digital Literacy Skills

Equipping students with digital literacy skills is essential in today’s digital landscape. Teach them to navigate online platforms responsibly, evaluate websites for credibility, and protect their privacy. Introduce them to fact-checking websites and tools that can help them verify information. Discuss the ethical considerations surrounding online content creation, including copyright and plagiarism.

Here are three strategies to enhance your student’s digital literacy skills.

Digital Research and Information Literacy: Teach students how to conduct effective online research and evaluate the credibility and reliability of digital sources. Introduce them to various search strategies, such as using appropriate keywords and advanced search operators, to find relevant and trustworthy information. Guide students in critically evaluating websites, considering factors such as authorship, domain authority, date of publication, and potential biases. Provide them with practical exercises where they can analyze and compare different sources of information on a specific topic. Emphasize the importance of citing sources and avoiding plagiarism in their digital research.

Digital Communication and Collaboration: Teach students effective digital communication and collaboration skills. Guide them in using appropriate language and etiquette in online communication, whether through email, discussion forums, or social media platforms. Discuss the importance of considering the audience and context when communicating online and the potential implications of their digital footprint.

Foster opportunities for collaborative digital projects, where students can learn to work together virtually, use digital collaboration tools, and engage in respectful and effective online teamwork. Emphasize the importance of clear and concise digital communication, active listening, and constructive feedback.

Educators can help students develop essential digital literacy skills by implementing these three strategies. Students will become adept at conducting effective online research, evaluating the credibility of digital sources, protecting their online privacy and security, and engaging in responsible digital communication and collaboration. These skills are vital for their success in the digital age and empower them to navigate the digital landscape with confidence and discernment.

4: Address Bias and Stereotypes in the Media

Guide students in identifying and challenging bias and stereotypes present in media. Teach them to recognize how media influences societal perceptions and impacts diverse communities. Provide examples of media representations that reinforce stereotypes and facilitate discussions on how these representations can perpetuate inequality and discrimination. Encourage students to seek out alternative narratives and diverse voices.

Here are three strategies for teaching this in the classroom.

Media Analysis and Deconstruction: Engage students in critical media analysis and deconstruction activities to identify and challenge bias and stereotypes. Select media examples, such as advertisements, news articles, TV shows, or movies, that contain explicit or implicit biases or reinforce stereotypes.

Guide students to analyze the language, visuals, representations, and portrayals in the media content. Encourage them to question the underlying assumptions, stereotypes, and biases present. Facilitate discussions where students can express their observations, share alternative perspectives, and explore the potential consequences of these biases and stereotypes. Encourage them to critically reflect on how media influences societal perceptions and impacts diverse communities.

Undertake Media Representation Projects: Assign projects that involve creating media representations that challenge bias and stereotypes. Ask students to create their own advertisements, news articles, videos, or other media artifacts that counter prevailing stereotypes and promote inclusive representations.

Provide guidelines and prompts that encourage students to think critically about the messages they want to convey and the impact they want to make. Emphasize the importance of accurately and respectfully representing different social, cultural, and ethnic groups. Encourage students to collaborate and share their creations, discussing the intentions and impact of their media representations.

Promote Diverse Media Consumption: Encourage students to actively seek out and consume media content from diverse sources and perspectives. Introduce them to media outlets, books, films, and online platforms prioritising diverse voices and challenging stereotypes. Provide recommendations and resources that showcase alternative narratives and perspectives.

Guide students in critically evaluating the diversity of media they consume and discussing the representations they encounter. Encourage them to question the absence or underrepresentation of certain groups and to explore media that provides more balanced and inclusive portrayals. Facilitate discussions where students can share their findings, insights, and reflections on the importance of diverse media consumption.

By incorporating these strategies into media literacy education, educators can effectively address bias and stereotypes in media. Students will develop the skills to critically analyze and challenge biased representations, actively create media promoting inclusivity, and seek out diverse media content. This empowers students to become more discerning consumers, critical thinkers, and advocates for media representations that reflect the diversity and richness of our society.

5: Embed Media Literacy Across the Curriculum

Integrate a media literacy curriculum across various subjects beyond traditional media studies. Show students how media literacy skills relate to science, history, literature, and other disciplines. For example, in a history class, students can analyze primary sources or examine the portrayal of historical events in films. By connecting media literacy to different subjects, students understand its universal applicability.

Embed Media Analysis and Content Creation into all subject areas: Integrate media analysis and creation activities across different subjects to enhance critical thinking and communication skills. For example, in English language arts, analyze media representations in literature or explore the persuasive techniques used in advertising.

In social studies, analyze historical documentaries or discuss the portrayal of different cultures and societies in media. In science, examine the portrayal of scientific concepts in popular media or evaluate the accuracy of scientific claims in news articles.

Encourage students to create media artifacts demonstrating their understanding of the subject, such as videos, podcasts, infographics, or written articles. Students gain a deeper understanding of the subject matter by integrating media literacy into various subjects while developing critical media analysis and media creation skills.

Create Collaborative Media Projects: Implement collaborative media projects that span multiple subjects, promoting interdisciplinary learning. Design projects that require students to research, analyze, and create media content related to a specific topic.

For example, students could collaborate on a digital storytelling project that combines historical research, creative writing, and digital media production. Students could create multimedia presentations or documentaries integrating scientific research, data analysis, and visual communication skills. By working together on these projects, students develop a comprehensive understanding of the topic, enhance their media literacy skills, and learn the value of collaboration and teamwork.

Promote the pursuit of Media Ethics and Digital Citizenship Discussions: Incorporate discussions on media ethics and digital citizenship into various subjects to foster responsible media consumption and online behaviour. Dedicate class time to explore topics such as media bias, fake news, online privacy, cyberbullying, or the responsible use of social media. Engage students in critical conversations about the ethical considerations of media production and consumption.

Provide opportunities for students to share their perspectives, debate relevant issues, and develop strategies for responsible digital engagement. By addressing media ethics and digital citizenship in different subjects, students comprehensively understand their responsibilities as media consumers and producers.

Educators can seamlessly integrate media literacy across all curriculum areas by employing these strategies. Students will develop critical thinking, creativity, communication, and digital citizenship skills, enabling them to navigate and engage with media in various academic contexts effectively.

Bonus tip for teaching media literacy: Stay Updated and Adapt:

Media landscapes and technologies evolve rapidly, so educators need to stay updated and adapt their teaching strategies accordingly. Stay informed about emerging media trends, new platforms, and changing media consumption patterns. Continuously refine your teaching methods to align with the ever-changing media landscape.

Teaching media literacy is essential for equipping students with the critical thinking skills to navigate the complex media environment. By starting early, promoting active consumption, developing digital literacy, fostering collaboration, addressing bias and stereotypes, incorporating media literacy across subjects, and staying updated, educators can empower students to become discerning consumers and active media content creators.

By implementing these strategies, educators play a pivotal role in shaping informed and engaged citizens who can confidently navigate the media landscape.

As educators, let us seize the opportunity to cultivate media literacy skills in our students, enabling them to analyze, evaluate, and create media content responsibly and effectively.

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Develop Your Media Literacy

- 8-minute read

- 26th January 2023

Quality writing includes citing sources correctly and avoiding bias or plagiarism. Unfortunately, this isn’t always the case, as the content we read online goes to extreme lengths to capture our attention and influence our behaviour. This is why developing media literacy is key, so you can read critically, make informed choices, and identify biases in your own writing.

What Is Media Literacy?

Media literacy is the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, and create media messages. It helps people become critical, active consumers and producers of media that understand the role of media in society.

Analyze Media Messages

Media messages are messages shared by organizations, individuals, news, and social media users with the intent to inform, entertain, persuade, or sell products to their target audience (you). This includes advertisements you see online, news clips, articles, social media posts, videos, images, and much more.

To develop your media literacy, it’s important to think critically about the media you consume and create. This includes understanding the purpose, audience, and techniques used in the message as well as identifying any bias or manipulation. It also includes understanding the context in which the message is presented, such as the source, medium, and historical and cultural background.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself to analyze media messages (think who , what , when , where , why , and how ):

● Who created this media?

● Who is funding this information/media/platform?

● Who is the intended audience for this message?

● Who benefits from sharing this message?

● What is the purpose of sharing this information/media?

● What does this information/message tell me about [the topic]?

● What sources back this message? Are they reputable? Are they from accredited and peer reviewed journals?

● What techniques are being used in this message to persuade me/others?

● What are the indirect messages?

● When was this information/media created? (i.e., is it recent or outdated?)

● When is this media message most relevant in my life? (e.g., does it pertain to a current event?)

● Where is this message/media being shared? (e.g., in a social media group, to specific communities)

● Where is this message/media NOT being shared? (i.e., who is being excluded?)

● Why is this message/information being shared? (i.e., to persuade, inform, entertain, or sell a product)

● Why is this message/information important or relevant to me/my community?

● How does this information/message impact my life or other’s lives?

● How is this message being shared across media platforms?

● How are other people reacting to this message/information?

● How might someone different from me (e.g., race, gender, nationality, socioeconomic background, age) interpret this message?

Evaluate Media Messages

Once you’ve analyzed a media message, evaluate it using your own criteria and values. This includes considering the accuracy, credibility, and reliability of the information, as well as the ethical and social implications of the information. It also includes considering your own emotions and reactions to it and whether they’ve been influenced by any manipulation or persuasion techniques .

To not fall victim of manipulation and persuasion techniques, it’s important to be aware of persuasive language strategies. Persuasive language is a powerful tool for winning your trust and influencing how you think. Let’s look at some examples.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Storytelling

A lot of what we see online uses the power of storytelling to appeal to your emotions and suck you in. For example, the Dodo shares videos about cute animals or unlikely animal friends to keep you watching, which is their main goal. The more views they get, the more money they make.

Now, in the broad scheme of things, watching a 60-second video about animal friends is no big deal. But what if it’s a video from a social media user that’s asking for donations to a GoFundMe page? Is the story biased in any way? Is the story true?

Presenting Evidence

The power of statistics and facts is real. They can boost your credibility and support your argument. However, statistics and facts can be used in misleading ways . Always examine the evidence presented in media and check sources.

Attacks on Other Parties

Attacking the “other party” in an effort to discredit them or tear apart their reputation is a common strategy when persuading people. This is often used in political campaigns. People or organizations who employ this strategy are trying to manipulate your emotions or make you angry to convince you of an idea.

They might exaggerate facts or use a misleading perspective to win you over, so you should always do your homework when presented with two sides of an argument or story.

This strategy is often used when trying to persuade consumers to buy a product or service. Many ads or salespeople shower you with compliments to make you feel good. When you feel good about yourself, such as your lifestyle or your physical appearance, then you’re more likely to purchase whatever they’re selling.

Inclusive Language

This is the “us versus the world” mentality that’s so common in media. Many companies use terms like “us,” “we,” and “our” to give you a sense of inclusion. Social media influencers, for example, might try to make their followers feel like they’re friends with them in real life.

This strategy makes you feel included, welcomed, and part of a community – all of which are great! But people may use this language to manipulate and influence your emotions so that you like them or are inclined to buy something.

Developing Media Literacy

Developing your media literacy is an ongoing process that requires practice and reflection. There are several strategies and resources that can help you to improve your media literacy skills.

Fact Checking and Verification

A key strategy for developing media literacy is fact checking and verifying information. This includes using multiple sources, checking their credibility and reliability, and looking for independent verifications. There are several fact checking tools:

● Factcheck.org

● PolitiFact

● LinkedIn (to look up authors and see if they have expertise in their field)

Education and Resources

Another strategy to develop media literacy is seeking out education and resources that can help you better understand the role of media in society and politics. This includes studying media and communication, reading books and articles about media literacy, and following experts and organizations on social media. Some media literacy organizations are:

● MediaSmarts

● Center for Media Literacy

● Media Education Lab

Children and Teens

Developing media literacy and being aware of the strategies and schemes that media uses is already difficult for adults, so imagine what it’s like for teens and children. They’re exposed to just as much (if not more!) media as adults are.

If you’re a parent and are concerned about your child’s media literacy , then have a conversation with them. You can also ask their teachers and school if they have a curriculum in place to educate students on media literacy. Be sure to also contact your local library for more resources and information.

Where can I find education and resources for media literacy?

Media Literacy Now is a great place to find resources for educators, parents, or individuals who are interested in learning more about media literacy.

How can media literacy help me to be a more informed citizen?

By becoming more media literate, you’ll learn to spot misinformation, misleading information, and manipulation tactics to make you believe a certain way. As a result, you’ll know where to find credible and reliable information so that you can make informed decisions when making purchases or casting your ballot.

How can I teach my children or students about media literacy?

If you’re a parent, have a conversation about media literacy with your children and educate yourself on media literacy so you can be prepared to answer their questions. For educators, using resources like Media Literacy Now is a great starting point, but you can also speak with your librarians or administration about implementing a media literacy curriculum at your school.

Media literacy is a big topic to take on and can feel overwhelming if you don’t know where to begin. The resources and links in this article are a great place to start educating yourself and expanding your knowledge of media literacy.

When you’re creating content, always make sure you have credible facts and information and use easy-to-understand language. If you need help polishing your content and conveying your message, our experts are here to help. We’ll even proofread your first 500 words for free !

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

3-minute read

What Is a Content Editor?

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

4-minute read

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

2-minute read

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

What Is Market Research?

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

8 Press Release Distribution Services for Your Business

In a world where you need to stand out, press releases are key to being...

How to Get a Patent

In the United States, the US Patent and Trademarks Office issues patents. In the United...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

- Research Paper

- Research Proposal

- SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

Media Literacy, Essay Example

Pages: 3

Words: 953

Hire a Writer for Custom Essay

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

Introduction

Media literacy is a complex issue that requires further investigation and evaluation in the modern era. It is important to identify the resources that are required to effectively adapt to a media-filled culture, whereby there are significant opportunities to achieve growth and change in the context of new ideas for growth and maturity for the average viewer/reader. It is known that “Interactivity as a core factor in multimedia is in some ways closely related to performance and can enable the viewer/reader/user to participate directly in the construction of meaning” (Daley 36). This quote is inspiring because it requires individuals to truly connect with the media on several levels that will have an instrumental impact on personal growth and the ability to be informative on many levels. The media saturates society through Facebook, Twitter, 24-hour news channels, and traditional forms such as magazines newspapers. Therefore, it is essential to identify a personal strategy that enables the reader/viewer to decipher through the hundreds if not thousands of messages that the media delivers on a daily basis so that individuals are better prepared to manage their own degree of literacy effectively.

For a website such as CNN.com, there appears to be a clash of sorts between that which is truly newsworthy and important to the lives of many people and that which might be deemed sensationalism to grab readers’ attention and an increased number of views, as well as ratings. This is a complex situation because the network and its accompanying website strive to remain competitive with the needs of its readers/viewers, while also requiring other factors to be considered that might improve their ability to decipher through the messages and to identify those which are most meaningful and appropriate within their lives. The homepage of the CNN website typically has an emerging or news-worthy story that is designed to grab the reader’s attention and to facilitate a response from the reader, perhaps a visceral reaction. This is part of the appeal of online news, as it attempts to draw viewers’ attention to what the website deems as newsworthy and of value to the reader. Although this is not always the case, the website achieves it key objective by attracting the reader enough to at least read the headlines and perhaps read some of the other stories that are listed on the homepage. Nonetheless, it is likely that many viewers will barely scratch the surface of an article because they lose interest or do not understand the backstory regarding the topic to keep reading. This is a key component of the high level of media illiteracy that exists in the modern era and that supports the development of new strategies to encourage readers to become less media illiterate and to improve their literacy regarding issues that generate much attention and focus from the masses.

There are critical factors associated with media literacy that require further consideration and evaluation, such as the tools that support the growth of individuals as they learn how to weave through the messages that they receive online, on television, and in print. Media literacy is more than merely reading stories, as it is about taking these stories in, forming opinions, developing a passion for a topic or an idea, and forming a bond with others who might share or contrast with these views (Media Literacy Project). In this context, it is important to identify the resources that are required to develop a strategy that supports media literacy on a much larger level that will impact society and its people as they develop a higher level of intelligence and/or acceptance of the ideas set forth within a given story or headline.

Overcoming media illiteracy requires the development of new strategies for individuals to take ideas that they read on a website such as CNN.com and to make them their own and perhaps apply them to their own lives in one or more ways. This is how media literacy works, as it enables individuals to transition from simply reading news stories online towards adapting them to their own lives in one way or another. This process engages readers and enables them to recognize the importance of improving their own level of literacy through these opportunities. It is imperative to recognize the value of media literacy as it applies to the human condition in the modern era, particularly as individuals have become increasingly dependent on the news as a part of their daily routines. This process supports and engages readers/viewers in the context of many different situations that enable them to cross over into a world where they have a better understanding of the media and how it impacts their lives in different ways.

Media literacy is a complex and ongoing phenomenon that has a unique impact on the lives of individuals. Many websites influence how people interpret the news, such as CNN.com, as they only tend to scratch the surface of news without any real opportunity to formulate opinions regarding the topics that are within. Therefore, it is important to identify some of the issues that are common in these stories and to recognize the importance of developing new approaches to stories that will have a positive impact on the response from readers/viewers. Media literacy is an ongoing process that requires the full attention and focus of individuals in order to accomplish the desired goals and objectives, while also considering the value of developing new perspectives that will encourage readers to take greater steps towards formulating their own opinions regarding stories and topics that may impact their own lives on many levels.

Works Cited

CNN.com. 11 May 2014: http://www.cnn.com/

Daley, Elizabeth. “Expanding the concept of literacy.” Educause, 11 May 2014: https://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/erm0322.pdf

Media Literacy Project. “What is media literacy?” 11 May 2014: http://medialiteracyproject.org/learn/media-literacy

Stuck with your Essay?

Get in touch with one of our experts for instant help!

Compression of Morbidity, Essay Example

Analysis of the King Lear, Essay Example

Time is precious

don’t waste it!

Plagiarism-free guarantee

Privacy guarantee

Secure checkout

Money back guarantee

Related Essay Samples & Examples

Voting as a civic responsibility, essay example.

Pages: 1

Words: 287

Utilitarianism and Its Applications, Essay Example

Words: 356

The Age-Related Changes of the Older Person, Essay Example

Pages: 2

Words: 448

The Problems ESOL Teachers Face, Essay Example

Pages: 8

Words: 2293

Should English Be the Primary Language? Essay Example

Pages: 4

Words: 999

The Term “Social Construction of Reality”, Essay Example

Words: 371

Jump to navigation

- Inside Writing

- Teacher's Guides

- Student Models

- Writing Topics

- Minilessons

- Shopping Cart

- Inside Grammar

- Grammar Adventures

- CCSS Correlations

- Infographics

Get a free Grammar Adventure! Choose a single Adventure and add coupon code ADVENTURE during checkout. (All-Adventure licenses aren’t included.)

Sign up or login to use the bookmarking feature.

Connecting Writing with Media Literacy

You routinely connect writing with reading, but how often do you connect writing with media literacy? It's a symbiotic relationship. You teach students to write about different topics for different audiences and purposes. They can use the same skills to engage media about different topics for different audiences and purposes.

Most writing teachers, though, wouldn’t consider themselves media-literacy coaches. They might not even know how to define media literacy: the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, and create communication in various media formats.

The same critical-thinking skills you teach in the writing process can help your students evaluate media for truth, fairness, and bias—skills increasingly necessary for academic success and responsible citizenship. Likewise, developing media-literacy skills prepares students to ethically share ideas in writing.

How can the writing process teach media literacy?

Students learn that good writing takes time—prewriting, writing, revising, and editing. As the old saying goes, "Easy writing makes hard reading, and hard writing makes easy reading." So students learn to appreciate well-crafted ideas—and, equally importantly, dismiss shoddy ideas when media are slapped together. Thoughtful writers make thoughtful readers, listeners, and viewers.

Let's look at each stage of the writing process to see how it can help you teach media literacy.

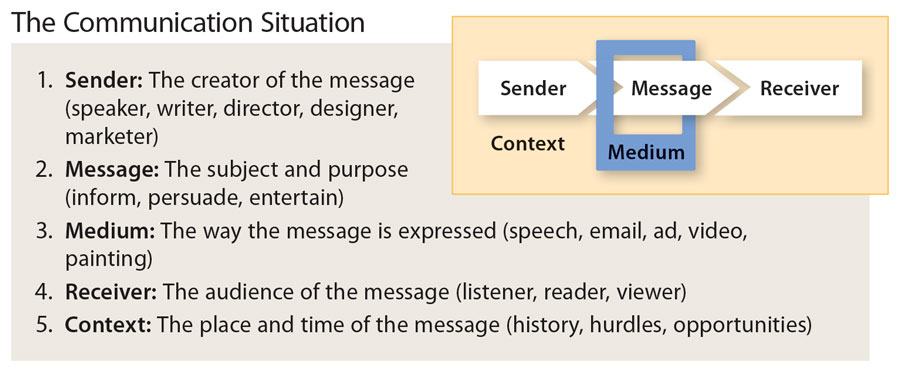

To meet the specific demands of a writing task, students should first consider the communication situation—sender, message, medium, receiver, and context:

Students who can analyze the rhetorical situation for writing can also analyze the same situation for the media they consume. All media is constructed, so all students can learn to deconstruct it—breaking it into its parts, considering how they work, and evaluating them. This rhetorical awareness helps students use sources ethically and reject media that uses them unethically.

This video can introduce the communication situation to your students:

And these minilessons teach students about each part of the communication situation:

- Analyzing the Sender of a Message

- Understanding a Message's Subject and Purpose

- Analyzing the Receiver of a Message

- Thinking About the Context of a Message

After prewriting, students should create a first draft, writing freely. Students who try to make everything perfect in this draft end up with "writer's block"—writing and erasing and writing and erasing until, after an hour of frustration, they have just two miserable words. Instead, students should turn off their critical minds and just pour their ideas onto the page.

Similarly, to judge media, students should first approach the content uncritically, setting aside personal biases . What is this source saying? Why? After reading or viewing, students can freewrite in response to questions like these:

- What parts of this message stick out?

- How does the information make me feel?

- How could this information be useful for me?

- How does the message compare with what I already know?

Once students have responded openly to a source, they must engage their critical thinking. They'll use the same skills they've learned for revising.

During the crucial revising step, students return to what they have written and make big improvements to their ideas, organization, voice, and style. To revise effectively, students must closely read their drafts, seeking gaps in information, weak evidence, fuzzy logic, and unclear or disorganized parts.

Students can use the same close-reading skills to critically analyze media. By picking apart the ideas, organization, and voice of media messages, students can more readily uncover false, biased, or incomplete information. And in doing so, they will avoid using or citing deceptive ideas in their own writing.

Use the following minilessons to help your students closely read media:

- Detecting Media Bias

- Analyzing Point of View in Media

- Detecting Fake News

Editing involves fine-tuning language. In this step, students should make sure all of the words and sentences are clear and correct, checking spelling, punctuation, capitalization, and usage. You can help students build awareness of language through grammar minilessons .

Careful attention to language can help students detect unreliable information. Conspicuous errors in spelling, capitalization, or grammar are red flags about the trustworthiness of the information.

Publishing

During publishing, students consider the design and presentation of their writing and how to best deliver it to their audience.

Close attention to media introduces students to effective design strategies and opportunities for submitting their writing outside of the classroom. Consider these publishing opportunities: 38 Ways Students Can Create Digital Content

Why should I teach media literacy?

Media literacy prepares your students to engage thoughtfully with the information that surrounds them. They need to sift the signal from the noise. The skills you teach them as writers—focusing on a specific topic with a specific purpose—help them become ethical consumers of information. And all that great writing instruction you're already providing helps them become ethical producers of information, as well!

Teacher Support:

Click to find out more about this resource.

Standards Correlations:

The State Standards provide a way to evaluate your students' performance.

- 110.5.b.11.C

- 110.5.b.11.D

- LAFS.3.W.2.5

- 110.6.b.11.A

- 110.6.b.11.C

- 110.6.b.11.D

- LAFS.4.W.2.5

- 110.7.b.11.A

- 110.7.b.11.C

- 110.7.b.11.D

- LAFS.5.W.2.5

- 110.22.b.10.A

- 110.22.b.10.C

- 110.22.b.10.D

- LAFS.6.W.2.5

- 110.23.b.10.A

- 110.23.b.10.C

- 110.23.b.10.D

- LAFS.7.W.2.5

- 110.24.b.10.A

- 110.24.b.10.C

- 110.24.b.10.D

- LAFS.8.W.2.5

- 110.36.c.9.A

- 110.36.c.9.C

- 110.36.c.9.D

- 110.37.c.9.A

- 110.37.c.9.C

- 110.37.c.9.D

- LAFS.910.W.2.5

- LA 10.2.1.a

- LA 10.2.1.e

- LA 10.2.1.f

- LA 10.2.1.h

- 110.38.c.9.A

- 110.38.c.9.C

- 110.38.c.9.D

- 110.39.c.9.A

- 110.39.c.9.C

- 110.39.c.9.D

- LAFS.1112.W.2.5

- LA 12.2.1.a

- LA 12.2.1.e

- LA 12.2.1.f

- LA 12.2.1.h

Related Resources

All resources.

- Evaluating Sources of Information

- Evaluating with a Pro-Con Chart

- Analyzing Writing Prompts

- Analyzing the Medium of a Message

- 7 Graphic Organizers for Critical Thinking

- Reading and Writing for Assessment

- Practice Test for Reading and Writing

- Writing Résumés and Cover Letters

- Writing Personal Essays

- Reading and Writing for Literature Assessment

- Inquire Middle School Teacher's Guide

- Inquire Middle School

- Inquire Elementary Teacher's Guide

- Inquire Elementary

- Inquire High School Teacher's Guide

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.8 Media Literacy

Learning objectives.

- Define media literacy.

- Describe the role of individual responsibility and accountability when responding to pop culture.

- List the five key considerations about any media message.

In Gutenberg’s age and the subsequent modern era, literacy—the ability to read and write—was a concern not only of educators, but also of politicians, social reformers, and philosophers. A literate population, many reasoned, would be able to seek out information, stay informed about the news of the day, communicate effectively, and make informed decisions in many spheres of life. Because of this, literate people made better citizens, parents, and workers. Several centuries later, as global literacy rates continued to grow, there was a new sense that merely being able to read and write was not enough. In a media-saturated world, individuals needed to be able to sort through and analyze the information they were bombarded with every day. In the second half of the 20th century, the skill of being able to decode and process the messages and symbols transmitted via media was named media literacy . According to the nonprofit National Association for Media Literacy Education (NAMLE), a person who is media literate can access, analyze, evaluate, and communicate information. Put another way by John Culkin, a pioneering advocate for media literacy education, “The new mass media—film, radio, TV—are new languages, their grammar as yet unknown (Moody, 1993).” Media literacy seeks to give media consumers the ability to understand this new language. The following are questions asked by those that are media literate:

- Who created the message?

- What are the author’s credentials?

- Why was the message created?

- Is the message trying to get me to act or think in a certain way?

- Is someone making money for creating this message?

- Who is the intended audience?

- How do I know this information is accurate?

Why Be Media Literate?

Culkin called the pervasiveness of media “the unnoticed fact of our present,” noting that media information was as omnipresent and easy to overlook as the air we breathe (and, he noted, “some would add that it is just as polluted”) (Moody, 1993). Our exposure to media starts early—a study by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 68 percent of children ages 2 and younger spend an average of 2 hours in front of a screen (either computer or television) each day, while children under 6 spend as much time in front of a screen as they do playing outside (Lewin). U.S. teenagers are spending an average of 7.5 hours with media daily, nearly as long as they spend in school. Media literacy isn’t merely a skill for young people, however. Today’s Americans get much of their information from various media sources—but not all that information is created equal. One crucial role of media literacy education is to enable us to skeptically examine the often-conflicting media messages we receive every day.

Advertising

Many of the hours people spend with media are with commercial-sponsored content. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) estimated that each child aged 2 to 11 saw, on average, 25,629 television commercials in 2004 alone, or more than 10,700 minutes of ads. Each adult saw, on average, 52,469 ads, or about 15.5 days’ worth of television advertising (Holt, 2007). Children (and adults) are bombarded with contradictory messages—newspaper articles about the obesity epidemic run side by side with ads touting soda, candy, and fast food. The American Academy of Pediatrics maintains that advertising directed to children under 8 is “inherently deceptive” and exploitative because young children can’t tell the difference between programs and commercials (Shifrin, 2005). Advertising often uses techniques of psychological pressure to influence decision making. Ads may appeal to vanity, insecurity, prejudice, fear, or the desire for adventure. This is not always done to sell a product—antismoking public service announcements may rely on disgusting images of blackened lungs to shock viewers. Nonetheless, media literacy involves teaching people to be guarded consumers and to evaluate claims with a critical eye.

Bias, Spin, and Misinformation

Advertisements may have the explicit goal of selling a product or idea, but they’re not the only kind of media message with an agenda. A politician may hope to persuade potential voters that he has their best interests at heart. An ostensibly objective journalist may allow her political leanings to subtly slant her articles. Magazine writers might avoid criticizing companies that advertise heavily in their pages. News reporters may sensationalize stories to boost ratings—and advertising rates.

Mass-communication messages are created by individuals, and each individual has his or her own set of values, assumptions, and priorities. Accepting media messages at face value could lead to confusion because of all the contradictory information available. For example, in 2010, a highly contested governor’s race in New Mexico led to conflicting ads from both candidates, Diane Denish and Susana Martinez, each claiming that the other agreed to policies that benefited sex offenders. According to media watchdog site FactCheck.org , the Denish team’s ad “shows a preteen girl—seemingly about 9 years old—going down a playground slide in slow-motion, while ominous music plays in the background and an announcer discusses two sex crime cases. It ends with an empty swing, as the announcer says: ‘Today we don’t know where these sex offenders are lurking, because Susana Martinez didn’t do her job.’” The opposing ad proclaims that “a department in Denish’s cabinet gave sanctuary to criminal illegals, like child molester Juan Gonzalez (Robertson & Kiely, 2010).” Both claims are highly inflammatory, play on fear, and distort the reality behind each situation. Media literacy involves educating people to look critically at these and other media messages and to sift through various messages and make sense of the conflicting information we face every day.

New Skills for a New World

In the past, one goal of education was to provide students with the information deemed necessary to successfully engage with the world. Students memorized multiplication tables, state capitals, famous poems, and notable dates. Today, however, vast amounts of information are available at the click of a mouse. Even before the advent of the Internet, noted communications scholar David Berlo foresaw the consequences of expanding information technology: “Most of what we have called formal education has been intended to imprint on the human mind all of the information that we might need for a lifetime.” Changes in technology necessitate changes in how we learn, Berlo noted, and these days “education needs to be geared toward the handling of data rather than the accumulation of data (Shaw, 2003).”

Wikipedia , a hugely popular Internet encyclopedia, is at the forefront of the debate on the proper use of online sources. In 2007, Middlebury College banned the use of Wikipedia as a source in history papers and exams. One of the school’s librarians noted that the online encyclopedia “symbolizes the best and worst of the Internet. It’s the best because everyone gets his/her say and can state their views. It’s the worst because people who use it uncritically take for truth what is only opinion (Byers, 2007).” Or, as comedian and satirist Stephen Colbert put it, “Any user can change any entry, and if enough other users agree with them, it becomes true (Colbert, 2006).” A computer registered to the U.S. Democratic Party changed the Wikipedia page for Rush Limbaugh to proclaim that he was “racist” and a “bigot,” and a person working for the electronic voting machine manufacturer Diebold was found to have erased paragraphs connecting the company to Republican campaign funds (Fildes, 2007). Media literacy teaches today’s students how to sort through the Internet’s cloud of data, locate reliable sources, and identify bias and unreliable sources.

Individual Accountability and Popular Culture

Ultimately, media literacy involves teaching that images are constructed with various aims in mind and that it falls to the individual to evaluate and interpret these media messages. Mass communication may be created and disseminated by individuals, businesses, governments, or organizations, but it is always received by an individual. Education, life experience, and a host of other factors make each person interpret constructed media in different ways; there is no correct way to interpret a media message. But on the whole, better media literacy skills help us function better in our media-rich environment, enabling us to be better democratic citizens, smarter shoppers, and more skeptical media consumers. When analyzing media messages, consider the following:

- Author: Consider who is presenting the information. Is it a news organization, a corporation, or an individual? What links do they have to the information they are providing? A news station might be owned by the company it is reporting on; likewise, an individual might have financial reasons for supporting a certain message.

- Format: Television and print media often use images to grab people’s attention. Do the visuals only present one side of the story? Is the footage overly graphic or designed to provoke a specific reaction? Which celebrities or professionals are endorsing this message?

- Audience: Imagine yourself in another’s shoes. Would someone of the opposite gender feel the same way as you do about this message? How might someone of a different race or nationality feel about it? How might an older or younger person interpret this information differently? Was this message made to appeal to a specific audience?

- Content: Even content providers that try to present information objectively can have an unconscious slant. Analyze who is presenting this message. Does he or she have any clear political affiliations? Is he or she being paid to speak or write this information? What unconscious influences might be at work?

- Purpose: Nothing is communicated by mass media without a reason. What reaction is the message trying to provoke? Are you being told to feel or act a certain way? Examine the information closely and look for possible hidden agendas.

With these considerations as a jumping-off place, we can ensure that we’re staying informed about where our information comes from and why it is being sent—important steps in any media literacy education (Center for Media Literacy).

Key Takeaways

- Media literacy, or the ability to decode and process media messages, is especially important in today’s media-saturated society. Media surrounds contemporary Americans to an unprecedented degree and from an early age. Because media messages are constructed with particular aims in mind, a media-literate individual will interpret them with a critical eye. Advertisements, bias, spin, and misinformation are all things to look for.

- Individual responsibility is crucial for media literacy because, while media messages may be produced by individuals, companies, governments, or organizations, they are always received and decoded by individuals.

- When analyzing media messages, consider the message’s author, format, audience, content, and purpose.

List the considerations for evaluating media messages and then search the Internet for information on a current event. Choose one blog post, news article, or video about the topic and identify the author, format, audience, content, and purpose of your chosen subject. Then, respond to the following questions. Each response should be a minimum of one paragraph.

- How did your impression of the information change after answering the five questions? Do you think other questions need to be asked?

- Is it difficult or easy to practice media literacy on the Internet? What are a few ways you can practice media literacy for television or radio shows?

- Do you think the public has a responsibility to be media literate? Why or why not?

End-of-Chapter Assessment

Review Questions

- What is the difference between mass communication and mass media?

- What are some ways that culture affects media?

- What are some ways that media affect culture?

- List four roles that media plays in society.

- Identify historical events that have shaped the adoption of various mass-communication platforms.

- How have technological shifts affected the media over time?

- What is convergence, and what are some examples of it in daily life?

- What were the five types of convergence identified by Jenkins?

- How are different kinds of convergence shaping the digital age on both an individual and a social level?

- How does the value of free speech affect American culture and media?

- What are some of the limits placed on free speech, and how do they reflect social values?

- What is propaganda, and how does it reflect and/or impact social values?

- Who are gatekeepers, and how do they influence the media landscape?

- What is a cultural period?

- How did events, technological advances, political changes, and philosophies help shape the Modern Era?

- What are some of the major differences between the modern and postmodern eras?

- What is media literacy, and why is it relevant in today’s world?

- What is the role of the individual in interpreting media messages?

- What are the five considerations for evaluating media messages?

Critical Thinking Questions

- What does the history of media technology have to teach us about present-day America? How might current and emerging technologies change our cultural landscape in the near future?

- Are gatekeepers and tastemakers necessary for mass media? How is the Internet helping us to reimagine these roles?

- The idea of cultural periods presumes that changes in society and technology lead to dramatic shifts in the way people see the world. How have digital technology and the Internet changed how people interact with their environment and with each other? Are we changing to a new cultural period, or is contemporary life still a continuation of the Postmodern Age?

- U.S. law regulates free speech through laws on obscenity, copyright infringement, and other things. Why are some forms of expression protected while others aren’t? How do you think cultural values will change U.S. media law in the near future?

- Does media literacy education belong in U.S. schools? Why or why not? What might a media literacy curriculum look like?

Career Connection

In a media-saturated world, companies use consultants to help analyze and manage the interaction between their organizations and the media. Independent consultants develop projects, keep abreast of media trends, and provide advice based on industry reports. Or, as writer, speaker, and media consultant Merlin Mann put it, the “primary job is to stay curious about everything, identify the points where two forces might clash, then enthusiastically share what that might mean, as well as why you might care (Mann).”

Read the blog post “So what do consultants do?” at http://www.consulting-business.com/so-what-do-consultants-do.html .