2 Logic and the Study of Arguments

If we want to study how we ought to reason (normative) we should start by looking at the primary way that we do reason (descriptive): through the use of arguments. In order to develop a theory of good reasoning, we will start with an account of what an argument is and then proceed to talk about what constitutes a “good” argument.

I. Arguments

- Arguments are a set of statements (premises and conclusion).

- The premises provide evidence, reasons, and grounds for the conclusion.

- The conclusion is what is being argued for.

- An argument attempts to draw some logical connection between the premises and the conclusion.

- And in doing so, the argument expresses an inference: a process of reasoning from the truth of the premises to the truth of the conclusion.

Example : The world will end on August 6, 2045. I know this because my dad told me so and my dad is smart.

In this instance, the conclusion is the first sentence (“The world will end…”); the premises (however dubious) are revealed in the second sentence (“I know this because…”).

II. Statements

Conclusions and premises are articulated in the form of statements . Statements are sentences that can be determined to possess or lack truth. Some examples of true-or-false statements can be found below. (Notice that while some statements are categorically true or false, others may or may not be true depending on when they are made or who is making them.)

Examples of sentences that are statements:

- It is below 40°F outside.

- Oklahoma is north of Texas.

- The Denver Broncos will make it to the Super Bowl.

- Russell Westbrook is the best point guard in the league.

- I like broccoli.

- I shouldn’t eat French fries.

- Time travel is possible.

- If time travel is possible, then you can be your own father or mother.

However, there are many sentences that cannot so easily be determined to be true or false. For this reason, these sentences identified below are not considered statements.

- Questions: “What time is it?”

- Commands: “Do your homework.”

- Requests: “Please clean the kitchen.”

- Proposals: “Let’s go to the museum tomorrow.”

Question: Why are arguments only made up of statements?

First, we only believe statements . It doesn’t make sense to talk about believing questions, commands, requests or proposals. Contrast sentences on the left that are not statements with sentences on the right that are statements:

It would be non-sensical to say that we believe the non-statements (e.g. “I believe what time is it?”). But it makes perfect sense to say that we believe the statements (e.g. “I believe the time is 11 a.m.”). If conclusions are the statements being argued for, then they are also ideas we are being persuaded to believe. Therefore, only statements can be conclusions.

Second, only statements can provide reasons to believe.

- Q: Why should I believe that it is 11:00 a.m.? A: Because the clock says it is 11a.m.

- Q: Why should I believe that we are going to the museum tomorrow? A: Because today we are making plans to go.

Sentences that cannot be true or false cannot provide reasons to believe. So, if premises are meant to provide reasons to believe, then only statements can be premises.

III. Representing Arguments

As we concern ourselves with arguments, we will want to represent our arguments in some way, indicating which statements are the premises and which statement is the conclusion. We shall represent arguments in two ways. For both ways, we will number the premises.

In order to identify the conclusion, we will either label the conclusion with a (c) or (conclusion). Or we will mark the conclusion with the ∴ symbol

Example Argument:

There will be a war in the next year. I know this because there has been a massive buildup in weapons. And every time there is a massive buildup in weapons, there is a war. My guru said the world will end on August 6, 2045.

- There has been a massive buildup in weapons.

- Every time there has been a massive buildup in weapons, there is a war.

(c) There will be a war in the next year.

∴ There will be a war in the next year.

Of course, arguments do not come labeled as such. And so we must be able to look at a passage and identify whether the passage contains an argument and if it does, we should also be identify which statements are the premises and which statement is the conclusion. This is harder than you might think!

There is no argument here. There is no statement being argued for. There are no statements being used as reasons to believe. This is simply a report of information.

The following are also not arguments:

Advice: Be good to your friends; your friends will be good to you.

Warnings: No lifeguard on duty. Be careful.

Associated claims: Fear leads to anger. Anger leads to the dark side.

When you have an argument, the passage will express some process of reasoning. There will be statements presented that serve to help the speaker building a case for the conclusion.

IV. How to L ook for A rguments [1]

How do we identify arguments in real life? There are no easy, mechanical rules, and we usually have to rely on the context in order to determine which are the premises and the conclusions. But sometimes the job can be made easier by the presence of certain premise or conclusion indicators. For example, if a person makes a statement, and then adds “this is because …,” then it is quite likely that the first statement is presented as a conclusion, supported by the statements that come afterward. Other words in English that might be used to indicate the premises to follow include:

- firstly, secondly, …

- for, as, after all

- assuming that, in view of the fact that

- follows from, as shown / indicated by

- may be inferred / deduced / derived from

Of course whether such words are used to indicate premises or not depends on the context. For example, “since” has a very different function in a statement like “I have been here since noon,” unlike “X is an even number since X is divisible by 4.” In the first instance (“since noon”) “since” means “from.” In the second instance, “since” means “because.”

Conclusions, on the other hand, are often preceded by words like:

- therefore, so, it follows that

- hence, consequently

- suggests / proves / demonstrates that

- entails, implies

Here are some examples of passages that do not contain arguments.

1. When people sweat a lot they tend to drink more water. [Just a single statement, not enough to make an argument.]

2. Once upon a time there was a prince and a princess. They lived happily together and one day they decided to have a baby. But the baby grew up to be a nasty and cruel person and they regret it very much. [A chronological description of facts composed of statements but no premise or conclusion.]

3. Can you come to the meeting tomorrow? [A question that does not contain an argument.]

Do these passages contain arguments? If so, what are their conclusions?

- Cutting the interest rate will have no effect on the stock market this time around, as people have been expecting a rate cut all along. This factor has already been reflected in the market.

- So it is raining heavily and this building might collapse. But I don’t really care.

- Virgin would then dominate the rail system. Is that something the government should worry about? Not necessarily. The industry is regulated, and one powerful company might at least offer a more coherent schedule of services than the present arrangement has produced. The reason the industry was broken up into more than 100 companies at privatization was not operational, but political: the Conservative government thought it would thus be harder to renationalize (The Economist 12/16/2000).

- Bill will pay the ransom. After all, he loves his wife and children and would do everything to save them.

- All of Russia’s problems of human rights and democracy come back to three things: the legislature, the executive and the judiciary. None works as well as it should. Parliament passes laws in a hurry, and has neither the ability nor the will to call high officials to account. State officials abuse human rights (either on their own, or on orders from on high) and work with remarkable slowness and disorganization. The courts almost completely fail in their role as the ultimate safeguard of freedom and order (The Economist 11/25/2000).

- Most mornings, Park Chang Woo arrives at a train station in central Seoul, South Korea’s capital. But he is not commuter. He is unemployed and goes there to kill time. Around him, dozens of jobless people pass their days drinking soju, a local version of vodka. For the moment, middle-aged Mr. Park would rather read a newspaper. He used to be a bricklayer for a small construction company in Pusan, a southern port city. But three years ago the country’s financial crisis cost him that job, so he came to Seoul, leaving his wife and two children behind. Still looking for work, he has little hope of going home any time soon (The Economist 11/25/2000).

- For a long time, astronomers suspected that Europa, one of Jupiter’s many moons, might harbour a watery ocean beneath its ice-covered surface. They were right. Now the technique used earlier this year to demonstrate the existence of the Europan ocean has been employed to detect an ocean on another Jovian satellite, Ganymede, according to work announced at the recent American Geo-physical Union meeting in San Francisco (The Economist 12/16/2000).

- There are no hard numbers, but the evidence from Asia’s expatriate community is unequivocal. Three years after its handover from Britain to China, Hong Kong is unlearning English. The city’s gweilos (Cantonese for “ghost men”) must go to ever greater lengths to catch the oldest taxi driver available to maximize their chances of comprehension. Hotel managers are complaining that they can no longer find enough English-speakers to act as receptionists. Departing tourists, polled at the airport, voice growing frustration at not being understood (The Economist 1/20/2001).

V. Evaluating Arguments

Q: What does it mean for an argument to be good? What are the different ways in which arguments can be good? Good arguments:

- Are persuasive.

- Have premises that provide good evidence for the conclusion.

- Contain premises that are true.

- Reach a true conclusion.

- Provide the audience good reasons for accepting the conclusion.

The focus of logic is primarily about one type of goodness: The logical relationship between premises and conclusion.

An argument is good in this sense if the premises provide good evidence for the conclusion. But what does it mean for premises to provide good evidence? We need some new concepts to capture this idea of premises providing good logical support. In order to do so, we will first need to distinguish between two types of argument.

VI. Two Types of Arguments

The two main types of arguments are called deductive and inductive arguments. We differentiate them in terms of the type of support that the premises are meant to provide for the conclusion.

Deductive Arguments are arguments in which the premises are meant to provide conclusive logical support for the conclusion.

1. All humans are mortal

2. Socrates is a human.

∴ Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

1. No student in this class will fail.

2. Mary is a student in this class.

∴ Therefore, Mary will not fail.

1. A intersects lines B and C.

2. Lines A and B form a 90-degree angle

3. Lines A and C form a 90-degree angle.

∴ B and C are parallel lines.

Inductive arguments are, by their very nature, risky arguments.

Arguments in which premises provide probable support for the conclusion.

Statistical Examples:

1. Ten percent of all customers in this restaurant order soda.

2. John is a customer.

∴ John will not order Soda..

1. Some students work on campus.

2. Bill is a student.

∴ Bill works on campus.

1. Vegas has the Carolina Panthers as a six-point favorite for the super bowl.

∴ Carolina will win the Super Bowl.

VII. Good Deductive Arguments

The First Type of Goodness: Premises play their function – they provide conclusive logical support.

Deductive and inductive arguments have different aims. Deductive argument attempt to provide conclusive support or reasons; inductive argument attempt to provide probable reasons or support. So we must evaluate these two types of arguments.

Deductive arguments attempt to be valid.

To put validity in another way: if the premises are true, then the conclusion must be true.

It is very important to note that validity has nothing to do with whether or not the premises are, in fact, true and whether or not the conclusion is in fact true; it merely has to do with a certain conditional claim. If the premises are true, then the conclusion must be true.

Q: What does this mean?

- The validity of an argument does not depend upon the actual world. Rather, it depends upon the world described by the premises.

- First, consider the world described by the premises. In this world, is it logically possible for the conclusion to be false? That is, can you even imagine a world in which the conclusion is false?

Reflection Questions:

- If you cannot, then why not?

- If you can, then provide an example of a valid argument.

You should convince yourself that validity is not just about the actual truth or falsity of the premises and conclusion. Rather, validity only has to do with a certain logical relationship between the truth of the premise and the truth of the conclusion. So the only possible combination that is ruled out by a valid argument is a set of true premises and false conclusion.

Let’s go back to example #1. Here are the premises:

1. All humans are mortal.

If both of these premises are true, then every human that we find must be a mortal. And this means, that it must be the case that if Socrates is a human, that Socrates is mortal.

Reflection Questions about Invalid Arguments:

- Can you have an invalid argument with a true premise?

- Can you have an invalid argument with true premises and a true conclusion?

The s econd type of goodness for deductive arguments: The premises provide us the right reasons to accept the conclusion.

Soundness V ersus V alidity:

Our original argument is a sound one:

∴ Socrates is mortal.

Question: Can a sound argument have a false conclusion?

VIII. From Deductive Arguments to Inductive Arguments

Question: What happens if we mix around the premises and conclusion?

2. Socrates is mortal.

∴ Socrates is a human.

1. Socrates is mortal

∴ All humans are mortal.

Are these valid deductive arguments?

NO, but they are common inductive arguments.

Other examples :

Suppose that there are two opaque glass jars with different color marbles in them.

1. All the marbles in jar #1 are blue.

2. This marble is blue.

∴ This marble came from jar #1.

1. This marble came from jar #2.

2. This marble is red.

∴ All the marbles in jar #2 are red.

While this is a very risky argument, what if we drew 100 marbles from jar #2 and found that they were all red? Would this affect the second argument’s validity?

IX. Inductive Arguments:

The aim of an inductive argument is different from the aim of deductive argument because the type of reasons we are trying to provide are different. Therefore, the function of the premises is different in deductive and inductive arguments. And again, we can split up goodness into two types when considering inductive arguments:

- The premises provide the right logical support.

- The premises provide the right type of reason.

Logical S upport:

Remember that for inductive arguments, the premises are intended to provide probable support for the conclusion. Thus, we shall begin by discussing a fairly rough, coarse-grained way of talking about probable support by introducing the notions of strong and weak inductive arguments.

A strong inductive argument:

- The vast majority of Europeans speak at least two languages.

- Sam is a European.

∴ Sam speaks two languages.

Weak inductive argument:

- This quarter is a fair coin.

∴ Therefore, the next coin flip will land heads.

- At least one dog in this town has rabies.

- Fido is a dog that lives in this town.

∴ Fido has rabies.

The R ight T ype of R easons. As we noted above, the right type of reasons are true statements. So what happens when we get an inductive argument that is good in the first sense (right type of logical support) and good in the second sense (the right type of reasons)? Corresponding to the notion of soundness for deductive arguments, we call inductive arguments that are good in both senses cogent arguments.

- With which of the following types of premises and conclusions can you have a strong inductive argument?

- With which of the following types of premises and conclusions can you have a cogent inductive argument?

X. Steps for Evaluating Arguments:

- Read a passage and assess whether or not it contains an argument.

- If it does contain an argument, then identify the conclusion and premises.

- If yes, then assess it for soundness.

- If not, then treat it as an inductive argument (step 3).

- If the inductive argument is strong, then is it cogent?

XI. Evaluating Real – World Arguments

An important part of evaluating arguments is not to represent the arguments of others in a deliberately weak way.

For example, suppose that I state the following:

All humans are mortal, so Socrates is mortal.

Is this valid? Not as it stands. But clearly, I believe that Socrates is a human being. Or I thought that was assumed in the conversation. That premise was clearly an implicit one.

So one of the things we can do in the evaluation of argument is to take an argument as it is stated, and represent it in a way such that it is a valid deductive argument or a strong inductive one. In doing so, we are making explicit what one would have to assume to provide a good argument (in the sense that the premises provide good – conclusive or probable – reason to accept the conclusion).

The teacher’s policy on extra credit was unfair because Sally was the only person to have a chance at receiving extra credit.

- Sally was the only person to have a chance at receiving extra credit.

- The teacher’s policy on extra credit is fair only if everyone gets a chance to receive extra credit.

Therefore, the teacher’s policy on extra credit was unfair.

Valid argument

Sally didn’t train very hard so she didn’t win the race.

- Sally didn’t train very hard.

- If you don’t train hard, you won’t win the race.

Therefore, Sally didn’t win the race.

Strong (not valid):

- If you won the race, you trained hard.

- Those who don’t train hard are likely not to win.

Therefore, Sally didn’t win.

Ordinary workers receive worker’s compensation benefits if they suffer an on-the-job injury. However, universities have no obligations to pay similar compensation to student athletes if they are hurt while playing sports. So, universities are not doing what they should.

- Ordinary workers receive worker’s compensation benefits if they suffer an on-the-job injury that prevents them working.

- Student athletes are just like ordinary workers except that their job is to play sports.

- So if student athletes are injured while playing sports, they should also be provided worker’s compensation benefits.

- Universities have no obligations to provide injured student athletes compensation.

Therefore, universities are not doing what they should.

Deductively valid argument

If Obama couldn’t implement a single-payer healthcare system in his first term as president, then the next president will not be able to implement a single-payer healthcare system.

- Obama couldn’t implement a single-payer healthcare system.

- In Obama’s first term as president, both the House and Senate were under Democratic control.

- The next president will either be dealing with the Republican-controlled house and senate or at best, a split legislature.

- Obama’s first term as president will be much easier than the next president’s term in terms of passing legislation.

Therefore, the next president will not be able to implement a single-payer healthcare system.

Strong inductive argument

Sam is weaker than John. Sam is slower than John. So Sam’s time on the obstacle will be slower than John’s.

- Sam is weaker than John.

- Sam is slower than John.

- A person’s strength and speed inversely correlate with their time on the obstacle course.

Therefore, Sam’s time will be slower than John’s.

XII. Diagramming Arguments

All the arguments we’ve dealt with – except for the last two – have been fairly simple in that the premises always provided direct support for the conclusion. But in many arguments, such as the last one, there are often arguments within arguments.

Obama example :

- The next president will either be dealing with the Republican controlled house and senate or at best, a split legislature.

∴ The next president will not be able to implement a single-payer healthcare system.

It’s clear that premises #2 and #3 are used in support of #4. And #1 in combination with #4 provides support for the conclusion.

When we diagram arguments, the aim is to represent the logical relationships between premises and conclusion. More specifically, we want to identify what each premise supports and how.

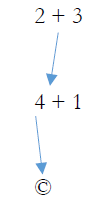

This represents that 2+3 together provide support for 4

This represents that 4+1 together provide support for 5

When we say that 2+3 together or 4+1 together support some statement, we mean that the logical support of these statements are dependent upon each other. Without the other, these statements would not provide evidence for the conclusion. In order to identify when statements are dependent upon one another, we simply underline the set that are logically dependent upon one another for their evidential support. Every argument has a single conclusion, which the premises support; therefore, every argument diagram should point to the conclusion (c).

Sam Example:

- Sam is less flexible than John.

- A person’s strength and flexibility inversely correlate with their time on the obstacle course.

∴ Therefore, Sam’s time will be slower than John’s.

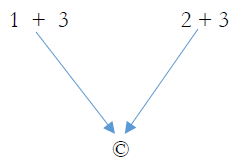

In some cases, different sets of premises provide evidence for the conclusion independently of one another. In the argument above, there are two logically independent arguments for the conclusion that Sam’s time will be slower than John’s. That Sam is weaker than John and that being weaker correlates with a slower time provide evidence for the conclusion that Sam will be slower than John. Completely independent of this argument is the fact that Sam is less flexible and that being less flexible corresponds with a slower time. The diagram above represent these logical relations by showing that #1 and #3 dependently provide support for #4. Independent of that argument, #2 and #3 also dependently provide support for #4. Therefore, there are two logically independent sets of premises that provide support for the conclusion.

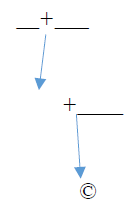

Try diagramming the following argument for yourself. The structure of the argument has been provided below:

- All humans are mortal

- Socrates is human

- So Socrates is mortal.

- If you feed a mortal person poison, he will die.

∴ Therefore, Socrates has been fed poison, so he will die.

- This section is taken from http://philosophy.hku.hk/think/ and is in use under creative commons license. Some modifications have been made to the original content. ↵

Critical Thinking Copyright © 2019 by Brian Kim is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

[A09] Good Arguments

Module: Argument analysis

- A01. What is an argument?

- A02. The standard format

- A03. Validity

- A04. Soundness

- A05. Valid patterns

- A06. Validity and relevance

- A07. Hidden Assumptions

- A08. Inductive Reasoning

- A10. Argument mapping

- A11. Analogical Arguments

- A12. More valid patterns

- A13. Arguing with other people

Quote of the page

- John Stuart Mill

Popular pages

- What is critical thinking?

- What is logic?

- Hardest logic puzzle ever

- Free miniguide

- What is an argument?

- Knights and knaves puzzles

- Logic puzzles

- What is a good argument?

- Improving critical thinking

- Analogical arguments

§1. What is a good argument?

In this tutorial we shall discuss what a good argument is. The concept of a good argument is of course quite vague. So what we are trying to do here is to give it a somewhat more precise definition. To begin with, make sure that you know what a sound argument is.

Criterion #1 : A good argument must have true premises

This means that if we have an argument with one or more false premises, then it is not a good argument. The reason for this condition is that we want a good argument to be one that can convince us to accept the conclusion. Unless the premises of an argument are all true, we would have no reason to accept to accept its conclusion.

Criterion #2 : A good argument must be either valid or strong

Is validity a necessary condition for a good argument? Certainly many good arguments are valid. Example:

All whales are mammals. All mammals are warm-blooded. So all whales are warm-blooded.

But it is not true that good arguments must be valid. We often accept arguments as good, even though they are not valid. Example:

No baby in the past has ever been able to understand quantum physics. Kitty is going to have a baby soon. So Kitty's baby is not going to be able to understand quantum physics.

This is surely a good argument, but it is not valid. It is true that no baby in the past has ever been able to understand quantum physics. But it does not follow logically that Kitty's baby will not be able to do so. To see that the argument is not valid, note that it is not logically impossible for Kitty's baby to have exceptional brain development so that the baby can talk and learn and understand quantum physics while still being a baby. Extremely unlikely to be sure, but not logically impossible, and this is enough to show that the argument is not valid. But because such possibilities are rather unlikely, we still think that the true premises strongly support the conclusion and so we still think that the argument is a good one.

In other words, a good argument need not be valid. But presumably if it is not valid it must be inductively strong. If an argument is inductively weak, then it cannot be a good argument since the premises do not provide good reasons for accepting the conclusion.

For more information about inductive strength, see the previous tutorial .

Criterion #3 : The premises of a good argument must not beg the question

Notice that criteria #1 and #2 are not sufficient for a good argument. First of all, we certainly don't want to say that circular arguments are good arguments, even if they happen to be sound. Suppose someone offers the following argument:

It is going to rain tomorrow. Therefore, it is going to rain tomorrow.

So far we think that a good argument must (1) have true premises, and (2) be valid or inductively strong. Are these conditions sufficient? The answer is no. Consider this example:

Smoking is bad for your health. Therefore smoking is bad for your health.

This argument is actually sound. The premise is true, and the argument is valid, because the conclusion does follow from the premise! But as an argument surely it is a terrible argument. This is a circular argument where the conclusion also appears as a premise. It is of course not a good argument, because it does not provide independent reasons for supporting the conclusion. So we say that it begs the question .

Here is another example of an argument that begs the question :

Since Mary would not lie to her best friend, and Mary told me that I am indeed her best friend, I must really be Mary's best friend.

Whether this argument is circular depends on your definition of a "circular argument". Some people might not consider this a circular argument in that the conclusion does not appear explicitly as a premise. However, the argument still begs the question and so is not a good argument.

Criterion #4 : The premises of a good argument must be plausible and relevant to the conclusion

Here, plausibility is a matter of having good reasons for believing that the premises are true. As for relevance, this is the requirement that the the subject matter of the premises must be related to that of the conclusion. Why do we need this additional criterion? The reason is that claims and theories can happen to be true even though nobody has got any evidence that they are true. If the premises of an argument happen to be true but there is no evidence indicating that they are, the argument is not going to be pursuasive in convincing people that the conclusion is correct. A good argument, on the other hand, is an argument that a rational person should accept, so a good argument should satisfy the additional criterion mentioned.

§2. Summary

So, here is our final definition of a good argument :

A good argument is an argument that is either valid or strong, and with plausible premises that are true, do not beg the question, and are relevant to the conclusion.

Now that you know what a good argument is, you should be able to explain why these claims are mistaken. Many people who are not good at critical thinking often make these mistakes :

"The conclusion of this argument is true, so some or all the premises are true." "One or more premises of this argument are false, so the conclusion is false." "Since the conclusion of the argument is false, all its premises are false." "The conclusion of this argument does not follow from the premises. So it must be false."

Answer the following questions.

- Does a good argument have to be sound? answer

- Can a good argument be inductively weak? answer

These are some arguments (or just premises) that students have given to support the idea that there is nothing morally wrong with eating meat. Discuss and evaluate these arguments carefully. Think about whether the premises are true, and whether they support the conclusion that it is morally acceptable to eat meat.

- Human beings are part of the food cycle of nature.

- Human beings are able to digest meat.

- It is ok to eat meat because meat is just a kind of food and we need food to survive.

- It is ok to eat meat because lots of people eat meat; because everyone around me eat meat.

- It is ok to eat meat because the government does not stop people from eating meat.

- Many other people eat meat.

- Meat contains protein, and we need protein to survive.

- We are animals, and it is ok for animals to eat animals.

- It is ok to eat meat because I started eating meat when I was a child.

- Meat is more tasty than vegetables.

- It is ok to eat meat because nobody told me that this is wrong.

- I love eating meat.

- It is ok to eat meat because set meals in restaurants have very little vegetables.

- Animals kill each other.

- Maintain the balance of nature - there will be too many animals otherwise.

- We are more powerful than animals.

- I was taught that I should eat meat.

- Human beings are at the top of the food chain.

- Eating meat can help me avoid certain diseases.

- We have special teeth for eating meat.

§3. A technical discussion

This section is a more abstract and difficult. You can skip this if you want.

One interesting but somewhat difficult issue about the definition of a good argument concerns the first requirement that a good argument must have true premises. One might argue that this requirement is too stringent, because we seem to accept many arguments as good arguments, even if we are not completely certain that the premises are true. Or perhaps we had good reasons for the premises, even if it turns out later that we were wrong.

As an example, suppose your friend told you that she is going camping for the whole weekend. She is a trustworthy friend and you have no reason to doubt her. So you accept the following argument as a good argument:

Amie will be camping this weekend. So she will not be able to come to my party.

But suppose the camping trip got cancelled at the last minute, and so Amie came to the party after all. What then should we say about the argument here? Was it a good argument? Surely you were justified in believing the premise, and so someone might argue that it is wrong to require that a good argument must have true premises. It is enough if the premises are highly justified (of course the other conditions must be satisfied as well.)

If we take this position, this implies that when we discover that the camping trip has been cancelled, we are no longer justified in believing the premise, and so at that point the argument ceases to be a good argument.

Here we prefer a different way of describing the situation. We want to say that although in the beginning we had good reasons to think that the argument is a good one, later on we discover that it wasn't a good argument to begin with. In other words, the argument doesn't change from being a good argument to a bad argument. It is just that we change our mind about whether the argument is a good one in light of new information. We think there are are reasons for preferring this way of describing the situation, and it is quite a natural way of speaking.

So there are actually two ways to use the term "good argument". We have adopted one usage here and it is fine if you want to use it differently. We think the ordinary meaning of the term is not precise enough to dictate a particular usage. What is important is to know very clearly how you are using it and what the consequences are as a result.

homepage • top • contact • sitemap

© 2004-2024 Joe Lau & Jonathan Chan

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Part Three: Evaluating Arguments

Chapter Seven: A Framework for Evaluating

The main aim of education is practical and reflective judgment, a mind trained to be critical everywhere in the use of evidence. —Brand Blanshard, Four Reasonable Men

Standard Evaluating Format

- Complex Arguments

- A Reasonable Objector over Your Shoulder

We now arrive at the portion of the book that is most important for good reasoning, the portion that Parts One and Two have been pointing toward: the evaluation of arguments.

In Part One we saw that good reasoning is ultimately a matter of cultivating the intellectual virtues, including the virtues of critical reflection, empirical inquiry, and intellectual honesty. This requires close attention to arguments, since cultivating each of these virtues is greatly enhanced by skill in clarifying and evaluating arguments. And close attention to arguments is shorthand, really, for close attention to whether arguments have the four merits of clarity, true premises, good logic, and conversational relevance.

In Part Two we saw that clarity is the starting point. This starting point is not only a matter of asking whether an argument is clear, but is also a matter of enhancing the argument’s clarity through the clarifying process. This process includes two general procedures: outlining the argument in standard clarifying format, and, at the same time, paraphrasing the argument for greater clarity. Paraphrasing should accomplish three things: streamlining, specifying, and structuring. And it should be governed by two general principles. The principle of loyalty tells you to imagine that the arguer is looking over your shoulder, checking to be sure that the paraphrased argument reflects the arguer’s intentions. The principle of charity applies if the context does not indicate the arguer’s intentions; it tells you to paraphrase in a way that makes the arguer as reasonable as possible—to paraphrase according to what you probably would have meant had you expressed the same words under similar circumstances.

The whole point of clarifying is to make it simpler to determine whether arguments have the other three merits. The remainder of the book has to do with asking these three questions of clarified arguments: Are the premises true? Is the logic good? And, to a lesser extent, Is the argument conversationally relevant?

7.1 Standard Evaluating Format

Just as there is a standard clarifying format, so is there a standard evaluating format. It systematically links your evaluation to the clarified argument and provides a framework for considering the questions about truth, logic, and conversational relevance. Let’s start with the clarified argument from Scientific American about the air sacs that are spread throughout the bodies of most birds:

- If air sacs of birds play a role in their breathing, then birds are poisoned by carbon monoxide introduced into their air sacs.

- Birds are not poisoned by carbon monoxide introduced into their air sacs.

- ∴ Air sacs of birds do not play a role in their breathing.

Standard evaluating format provides a simple system for discussing the truth of each premise, the logic of the argument, and (where appropriate) the conversational relevance of the argument. Begin with the main heading EVALUATION, and under it provide at least three subheadings: TRUTH, LOGIC, and SOUNDNESS. (In some cases you will need a fourth subheading, CONVERSATIONAL RELEVANCE.)

Under TRUTH, provide an entry for each premise, and for each premise do two things: state whether you judge the premise to be true, and provide your defense of that evaluation. For the air sac argument, this part of the evaluation would look something like this:

Premise 1. This premise is probably true, assuming large enough quantities of carbon monoxide are involved, since carbon monoxide is known to be poisonous to any animal when breathed in sufficient quantities.

Premise 2. This premise is probably true, since this is reported in Scientific American, known to be a highly reliable publication on topics of this sort, and there is no reason to doubt this particular report.

Under the next subheading, LOGIC, do the same things: state whether you think the logic of the simple argument is good, and provide a defense of that evaluation. The evaluation would continue roughly as follows:

The argument is valid, since it has the form denying the consequent.

It isn’t important at this point in the text that you understand the exact technical meaning of expressions like valid or denying the consequent. For now you only need to know what is intuitively obvious—that expressions like valid, very strong, and fairly strong are ways of saying that the logic is good, while expressions like invalid, fairly weak, and very weak are ways of saying that it is bad.

After this, under the heading SOUNDNESS, provide your summary judgment— sound or unsound —based on the two preceding sections of the evaluation. If you judge that the argument is not sound, state whether this is owing to a problem either with a premise or with the argument’s logic. But if you judge that it is sound, there is no need for further explanation since saying it is sound is the same as saying the premises are true and the logic is good. In our sample air sac case, it would look like this:

The argument is probably sound.

Notice the argument is judged probably sound. Your judgment of the argument’s soundness cannot be any better than the poorest thing said under TRUTH and LOGIC. While under the heading of LOGIC the logic of the air sac argument is judged to be good, under the heading of TRUTH each of the premises is judged merely probably true. Thus, the argument cannot be evaluated as any better than probably sound.

We have not yet provided a place in the format for conversational relevance. This can be an extremely important question, but it will turn out that the majority of the arguments you evaluate will not appear to be defective in this way. My suggestion—which we will follow in this text—is that a fourth subheading, CONVERSATIONAL RELEVANCE, be optional. Include it when an argument is conversationally flawed, and under the heading explain how the argument is thus flawed. But otherwise omit it, simply for the practical reason that it will save you extra writing.

The air sac argument is, so far as I can tell, conversationally relevant. Without any context, there is no good reason to think that it begs the question or misses the point. We could imagine, however, contexts in which it would be conversationally flawed. Suppose, for example, that the same argument had been put forward by a laboratory assistant who was asked by the laboratory director to look into whether air sacs in birds played any role in their breeding. We would in that case add a fourth subheading, as follows:

CONVERSATIONAL RELEVANCE

Even though it is sound, the argument commits the fallacy of missing the point, since the point is to show whether the air sacs play any role in breeding, but the argument only addresses whether they play a role in breathing.

By following this format, you can develop the habit of systematically asking all the right evaluative questions of an argument, and you will always have a straightforward way of presenting your judgments.

Heading: EVALUATION

Subheading: TRUTH. For each premise, state whether you judge it to be true and provide your defense of that judgment.

Subheading: LOGIC. State whether you judge the logic to be successful and provide your defense of that judgment.

Subheading: SOUNDNESS. State whether you judge the argument to be sound; then, if it is not sound, state whether this is owing to a problem with a premise or with the logic.

Subheading (optional): CONVERSATIONAL RELEVANCE. If and only if the argument is flawed in this way, state whether it commits the fallacy of begging the question or missing the point, and explain how.

Exercises Chapter 7, set (a)

Given the brief evaluations provided for truth and logic, provide, in standard form, the correct evaluation of the argument’s soundness.

Sample exercise (1).

TRUTH. Premise 1 is probably true. I can’t decide about premise 2. LOGIC. The argument is valid.

Sample answer (1).

SOUNDNESS. I can’t decide whether the argument is sound, since I can’t decide about the truth of one of the premises.

Sample exercise (2).

TRUTH. Premise 1 is certainly true. LOGIC. The argument is fairly weak logically.

Sample answer (2).

SOUNDNESS. The argument is fairly unsound, since the logic is fairly weak.

- TRUTH. Premise 1 is probably false. I can’t decide about premise 2. LOGIC. The argument is invalid.

- TRUTH. Premise 1 is probably false. LOGIC. The argument is extremely weak.

- TRUTH. Premise 1 is certainly false. I can’t decide about premise 2. LOGIC. The argument is valid.

- TRUTH. Premise 1 is certainly true. LOGIC. The argument is valid.

- TRUTH. Premise 1 is probably true. I can’t decide about premise 2. Premise 3 is certainly true. LOGIC. The argument is fairly strong.

- TRUTH. Premise 1 is probably true. Premise 2 is probably true. Premise 3 is certainly true. LOGIC. The argument is very strong.

7.1.1 The Conclusion

You may have noticed there is no place in this format for evaluating whether the main conclusion of any argument is itself true. This may initially strike you as a serious oversight. But it is not. What we are evaluating here is not the truth of the conclusion, but the quality of the reasoning for the conclusion. Suppose you decided that an argument was utterly unsound, yet at the same time suspected that the conclusion was true. That would be no problem. Recall that for any true statement, it is possible to offer a bad argument in the attempt to support the statement. (If it then turned out that you were especially interested in such a conclusion, it would be up to you to see if you could come up with a better argument for it.) On the other hand, suppose you had a strong hunch that a conclusion was false, even though the argument itself appeared to be sound. This would give you good reason to check more carefully for a flaw in the argument, one that may have initially escaped your notice. Or you could end up changing your mind and accepting the initially implausible conclusion.

7.2 Complex Arguments

There is no important difference between evaluating a simple argument and a complex one. If the argument is complex—that is, if it is a series of linked simple arguments—then, after the clarification of the complex argument, evaluate separately each simple argument that makes up the complex argument. Instead of the heading EVALUATION, use the heading EVALUATION OF ARGUMENT TO N, where n identifies the relevant subconclusion or conclusion. To illustrate, suppose other air sac experiments by Professor Soum, reported in the same Scientific American story, had independently narrowed down the role of air sacs in birds to either flight-enhancement or breathing-enhancement. Suppose further that the air sac argument had been the first part of a larger argument that was designed to settle this issue, concluding thus:

Therefore, since air sacs in birds are known to play a role in either flight or breathing, we can conclude that they play a role in flight.

The complex argument would be clarified thus (adding premise 4 and a new conclusion):

- Air sacs of birds play a role in their breathing or air sacs in birds play a role in their flight.

- ∴ Air sacs of birds play a role in their flight.

The evaluation, framed in standard evaluation format, would then look like this:

EVALUATION OF ARGUMENT TO 3

Premise 2. This premise is probably true, since this is reported in Scientific American, known to be a highly reliable publication on topics of this sort, and there is no special reason to doubt this particular report.

The argument is valid, since it has the form of denying the consequent.

EVALUATION OF ARGUMENT TO C

Premise 3 is probably true, since it is supported by an argument that we have seen is probably sound (see evaluation of argument to 3).

Premise 4 is probably true, since (according to my hypothetical addition to the actual story, for the sake of this illustration) the experiments are reported in Scientific American, known to be a highly reliable publication on topics of this sort, and there is no reason to doubt this particular report.

The argument is valid, since it has the form of the process of elimination.

The evaluation of the first simple argument remains exactly the same, except for expanding the heading to say EVALUATION OF THE ARGUMENT TO 3. And we add to it the evaluation of the second simple argument—the evaluation of the argument to C . Premise 3 is the subconclusion of the complex argument—so it is both the conclusion of the argument to 3 and a premise in the argument to C . When evaluating its truth (under the heading EVALUATION OF THE ARGUMENT TO C) it is good to point out that the premise is supported by an argument that you have just evaluated as probably sound.

7.2.1 When a Simple Argument within the Complex Argument Is Unsound

In a complex argument, when one simple argument is sound it has an important effect on your entire evaluation. When you evaluate the subconclusion as a premise in the next simple argument, the soundness of the preceding simple argument serves as a good defense for judging its subconclusion to be true.

But this ripple effect does not naturally occur if the simple argument is unsound. Obviously, its unsoundness would not be something to appeal to in defense of the truth of the subconclusion. But—note this carefully—neither would it be something to appeal to in defense of the falsity of the subconclusion. Any statement, whether true or false, can have an unsound argument offered for it.

This presents an interesting problem: in a complex argument, you can evaluate a simple argument as unsound without its affecting your evaluation of the next simple argument. Thus, in a complex argument, you may evaluate as perfectly sound the argument to the main conclusion, even though the previous simple arguments have been unsound. This is as it should be. But at the same time, since the arguer has presented the complex argument as a whole, there should be some way of indicating earlier problems when you evaluate later simple arguments.

The solution is this: in a complex argument, when one simple argument is unsound and the next one is sound, qualify your evaluation of it as sound but not shown . In this way, you indicate that even though the simple argument is, in your judgment, sound, the arguer has failed to carry out the job of showing it to be sound by the previous simple arguments.

Here is an easy-to-understand example:

You have to be extremely good-looking to get hired as a lifeguard. Not many people are that good-looking, so it’s very tough to land such a job. For that reason, even though it would be great to work on the beach, most people should probably try to find some other sort of summer job.

This argument can be clarified as follows:

- If someone qualifies for a job as a lifeguard, then that person is extremely good-looking.

- Not many people are extremely good-looking.

- ∴ Not many people qualify for a job as a lifeguard.

- If not many people qualify for a particular job, then most people should try for some other sort of job.

- ∴ Most people should try for some other summer job than that of a lifeguard.

The subconclusion— Not many people qualify for a job as a lifeguard —seems clearly to be true. And even though the simple argument offered in its support is a bad one (premise 1, despite evidence you might gather from Baywatch reruns, is surely false), the simple argument from premises 3 and 4 to the main conclusion is a pretty good one. A very brief evaluation might take this rough form:

Premise 1. This premise is certainly false; it isn’t looks, but experience and ability, which qualify you for a job as a lifeguard.

Premise 2. This premise is very probably true. My observations are that most people are average-looking (it may even be that average-looking just means the way most people look ).

The argument is valid, since it has the form of singular denying the consequent.

The argument is unsound, due to the falsity of premise 1.

Premise 3 is certainly true. Most people need a lifeguard just because they aren’t qualified to be one. Qualifying to be a lifeguard requires that you be in excellent physical shape, that you be able to swim well, and that you have extensive training. (Before completing the evaluation, note that even though the argument to 3 has just been evaluated as unsound, I have nevertheless defended here the truth of 3—but for entirely different reasons than those offered in the argument to 3.)

Premise 4 is probably true. Under most circumstances, it doesn’t make good practical sense for people to apply for a job if their chances of getting it are extremely low.

The argument is valid, since it has the form of singular affirming the antecedent.

The argument is probably sound, but is not shown to be so by the rest of the argument.

Note that the argument to C is judged as probably sound (since the poorest thing said about it under TRUTH and LOGIC is that its premises are probably true ). But, to reflect the unsoundness of the simple argument used to lead into it, it is noted that it was not shown to be sound by the preceding simple argument.

Exercises Chapter 7, set (b)

Briefly describe the general conditions under which each of the following evaluations would apply.

- Probably sound.

- Sound but not shown.

- Can’t decide whether it is sound.

- Unsound but not shown.

- True but not shown.

- Logically successful but not shown.

- Logically successful because the preceding simple argument has been evaluated as sound.

7.3 A Reasonable Objector Over Your Shoulder

Whenever you write anything, it is crucially important that you know who your audience is. You may be writing for introductory students, your professor, your parents, a customer, a friend, your professional colleagues, or the general public. Different writing is designed for different audiences. And this applies to argument evaluations. Often they are directed at the arguer, whom you may hope to prove wrong. When doing the exercises in this text, you will be aiming them to your professor, who will grade your paper. When you do them on your job, you may be aiming them to a potential customer, whom you may hope to convince of the flaws in your competitor’s product.

But in the background, your primary audience should always be you. You should be aiming to arrive at the best evaluation you can for your own sake —the evaluation that is most likely to result in your arriving at knowledge and the one most likely to cultivate the habits that would continue to be conducive to your arriving at knowledge. In short, always evaluate arguments with a view to being the most honest, critically reflective, and inquisitive thinker you can be.

It may not always be easy to think in this way when evaluating an argument. It can be much easier to think in terms of an opponent who must be won over. And this can be turned to your advantage. Recall that an important guideline for clarifying is to imagine the arguer looking over your shoulder, checking your paraphrase for loyalty to the arguer’s intentions. I now recommend that you be similarly accompanied while evaluating the argument. In evaluating, though, imagine that looking over your shoulder is a reasonable person who disagrees with your evaluation. This reasonable objector has roughly the same evidence that you have and possesses the intellectual virtues of honesty, critical reflection, and inquiry. What reasons are most likely to persuade this person to accept your evaluation? What objection is this person most likely to raise? Be sure to express your defense in a way that defeats—or ultimately agrees with—the objections of this hypothetical adversary. In this way, you are more likely to exemplify the intellectual virtues yourself.

7.4 Summary of Chapter Seven

Frame your evaluation of every argument in the standard evaluation format, thereby ensuring that you appropriately present and defend your evaluation of the truth of every premise, the success of the argument’s logic, and, when necessary, the conversational relevance of the argument. The key judgment in every case is whether the argument is sound—that is, whether it is successful with respect to both truth and logic. Failure in either respect makes the argument unsound; and the poorest judgment in either respect should be reflected in your evaluation of the argument’s soundness. (Thus, for example, an argument that is logically successful and with a premise you have judged to be probably true can, at best, be probably sound.)

When the argument is complex, separately evaluate each component simple argument. If one of the simple arguments other than the argument to the main conclusion is unsound, and if a later simple argument is sound, be sure the earlier failure is reflected by noting that even the sound argument has not been shown to be sound in the preceding portion of the complex argument.

While thinking about and writing your evaluation, imagine that a reasonable objector—an intellectually virtuous person who has roughly the same evidence you have but disagrees with you—is watching over your shoulder and must be persuaded by your evaluation.

7.5 Guidelines for Chapter Seven

- Evaluate the clarified argument in standard evaluating format.

- Your evaluation of the argument’s soundness should be no better than the poorest evaluation you have provided of its logic and of the truth of its premises.

- If you have judged an argument to be sound, but you find that you still have doubts about the truth of the conclusion, carefully examine the argument again. You may initially have overlooked a flaw.

- Evaluate separately each simple argument that serves as a component of a complex argument.

- In a complex argument, if one simple argument is unsound and a later one is sound, qualify your evaluation of the sound one by saying that it is sound but not shown. This applies only to complex arguments.

- While writing your evaluation, imagine there is a reasonable objector looking over your shoulder, one whom you must persuade.

7.6 Glossary for Chapter Seven

Reasonable objector —someone who has approximately the same information you have, who exhibits the virtues of honesty, critical reflection, and inquiry, yet who disagrees with your evaluation. Imagine that this is your audience for every evaluation you write.

Sound but not shown —evaluation to use under the SOUNDNESS subheading in a complex argument when one simple argument is sound but a preceding simple argument, on which it depends, is unsound. Using this terminology reflects the fact that even though this simple argument happens to be sound, the arguer has failed to show it to be so, by virtue of having supported it with an unsound argument.

Evaluation to use under the SOUNDNESS subheading in a complex argument when one simple argument is sound but a preceding simple argument, on which it depends, is unsound. Using this terminology reflects the fact that even though this simple argument happens to be sound, the arguer has failed to show it to be so, by virtue of having supported it with an unsound argument.

Someone who has approximately the same information you have, who exhibits the virtues of honesty, critical reflection, and inquiry, yet who disagrees with your evaluation. Imagine that this is your audience for every evaluation you write.

A Guide to Good Reasoning: Cultivating Intellectual Virtues Copyright © 2020 by David Carl Wilson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Part I: Propositional Logic

3. Good Arguments

3.1 a historical example.

An important example of excellent reasoning can be found in the case of the medical advances of the Nineteenth Century physician, Ignaz Semmelweis. Semmelweis was an obstetrician at the Vienna General Hospital. Built on the foundation of a poor house, and opened in 1784, the General Hospital is still operating today. Semmelweis, during his tenure as assistant to the head of one of two maternity clinics, noticed something very disturbing. The hospital had two clinics, separated only by a shared anteroom, known as the First and the Second Clinics. The mortality rate for mothers delivering babies in the First Clinic, however, was nearly three times as bad as the mortality for mothers in the Second Clinic (9.9 % average versus 3.4% average). The same was true for the babies born in the clinics: the mortality rate in the First Clinic was 6.1% versus 2.1% at the Second Clinic. [5] In nearly all these cases, the deaths were caused by what appeared to be the same illness, commonly called “childbed fever”. Worse, these numbers actually understated the mortality rate of the First Clinic, because sometimes very ill patients were transferred to the general treatment portion of the hospital, and when they died, their death was counted as part of the mortality rate of the general hospital, not of the First Clinic.

Semmelweis set about trying to determine why the First Clinic had the higher mortality rate. He considered a number of hypotheses, many of which were suggested by or believed by other doctors.

One hypothesis was that cosmic-atmospheric-terrestrial influences caused childbed fever. The idea here was that some kind of feature of the atmosphere would cause the disease. But, Semmelweis observed, the First and Second Clinics were very close to each other, had similar ventilation, and shared a common anteroom. So, they had similar atmospheric conditions. He reasoned: If childbed fever is caused by cosmic-atmospheric-terrestrial influences, then the mortality rate would be similar in the First and Second Clinics. But the mortality rate was not similar in the First and Second Clinics. So, the childbed fever was not caused by cosmic-atmospheric-terrestrial influences.

Another hypothesis was that overcrowding caused the childbed fever. But, if overcrowding caused the childbed fever, then the more crowded of the two clinics should have the higher mortality rate. But, the Second Clinic was more crowded (in part because, aware of its lower mortality rate, mothers fought desperately to be put there instead of in the First Clinic). It did not have a higher mortality rate. So, the childbed fever was not caused by overcrowding.

Another hypothesis was that fear caused the childbed fever. In the Second Clinic, the priest delivering last rites could walk directly to a dying patient’s room. For reasons of the layout of the rooms, the priest delivering last rites in the First Clinic walked by all the rooms, ringing a bell announcing his approach. This frightened patients; they could not tell if the priest was coming for them. Semmelweis arranged a different route for the priest and asked him to silence his bell. He reasoned: if the higher rate of childbed fever was caused by fear of death resulting from the priest’s approach, then the rate of childbed fever should decline if people could not tell when the priest was coming to the Clinic. But it was not the case that the rate of childbed fever declined when people could not tell if the priest was coming to the First Clinic. So, the higher rate of childbed fever in the First Clinic was not caused by fear of death resulting from the priest’s approach.

In the First Clinic, male doctors were trained; this was not true in the Second Clinic. These male doctors performed autopsies across the hall from the clinic, before delivering babies. Semmelweis knew of a doctor who cut himself while performing an autopsy, and who then died a terrible death not unlike that of the mothers who died of childbed fever. Semmelweis formed a hypothesis. The childbed fever was caused by something on the hands of the doctors, something that they picked up from corpses during autopsies, but that infected the women and infants. He reasoned that: if the fever was caused by cadaveric matter on the hands of the doctors, then the mortality rate would drop when doctors washed their hands with chlorinated water before delivering babies. He forced the doctors to do this. The result was that the mortality rate dropped to a rate below that even of the Second Clinic.

Semmelweis concluded that the best explanation of the higher mortality rate was this “cadaveric matter” on the hands of doctors. He was the first person to see that washing of hands with sterilizing cleaners would save thousands of lives. It is hard to overstate how important this contribution is to human well being. Semmelweis’s fine reasoning deserves our endless respect and gratitude.

But how can we be sure his reasoning was good? Semmelweis was essentially considering a series of arguments. Let us turn to the question: how shall we evaluate arguments?

3.2 Arguments

Our logical language now allows us to say conditional and negation statements. That may not seem like much, but our language is now complex enough for us to develop the idea of using our logic not just to describe things, but also to reason about those things.

We will think of reasoning as providing an argument. Here, we use the word “argument” not in the sense of two or more people criticizing each other, but rather in the sense we mean when we say, “Pythagoras’s argument”. In such a case, someone is using language to try to convince us that something is true. Our goal is to make this notion very precise, and then identify what makes an argument good.

We need to begin by making the notion of an argument precise. Our logical language so far contains only sentences. An argument will, therefore, consist of sentences. In a natural language, we use the term “argument” in a strong way, which includes the suggestion that the argument should be good. However, we want to separate the notion of a good argument from the notion of an argument, so we can identify what makes an argument good, and what makes an argument bad. To do this, we will start with a minimal notion of what an argument is. Here is the simplest, most minimal notion:

Argument: an ordered list of sentences; we call one of these sentences the “conclusion”, and we call the other sentences “premises”.

This is obviously very weak. (There is a famous Monty Python skit where one of the comedians ridicules the very idea that such a thing could be called an argument.) But for our purposes, this is a useful notion because it is very clearly defined, and we can now ask, what makes an argument good?

The everyday notion of an argument is that it is used to convince us to believe something. The thing that we are being encouraged to believe is the conclusion. Following our definition of “argument”, the reasons that the person gives will be what we are calling “premises”. But belief is a psychological notion. We instead are interested only in truth. So, we can reformulate this intuitive notion of what an argument should do, and think of an argument as being used to show that something is true. The premises of the argument are meant to show us that the conclusion is true.

What then should be this relation between the premises and the conclusion? Intuitive notions include that the premises should support the conclusion, or corroborate the conclusion, or make the conclusion true. But “support” and “corroborate” sound rather weak, and “make” is not very clear. What we can use in their place is a stronger standard: let us say as a first approximation that if the premises are true, the conclusion is true.

But even this seems weak, on reflection. For, the conclusion could be true by accident, for reasons unrelated to our premises. Remember that we define the conditional as true if the antecedent and consequent are true. But this could happen by accident. For example, suppose I say, “If Tom wears blue then he will get an A on the exam”. Suppose also that Tom both wears blue and Tom gets an A on the exam. This makes the conditional true, but (we hope) the color of his clothes really had nothing to do with his performance on the exam. Just so, we want our definition of “good argument” to be such that it cannot be an accident that the premises and conclusion are both true.

A better and stronger standard would be that, necessarily, given true premises, the conclusion is true.

This points us to our definition of a good argument. It is traditional to call a good argument “valid.”

Valid argument: an argument for which, necessarily, if the premises are true, then the conclusion is true.

This is the single most important principle in this book. Memorize it.

A bad argument is an argument that is not valid. Our name for this will be an “invalid argument”.

Sometimes, a dictionary or other book will define or describe a “valid argument” as an argument that follows the rules of logic. This is a hopeless way to define “valid”, because it is circular in a pernicious way: we are going to create the rules of our logic in order to ensure that they construct valid arguments. We cannot make rules of logical reasoning until we know what we want those rules to do, and what we want them to do is to create valid arguments. So “valid” must be defined before we can make our reasoning system.

Experience shows that if a student is to err in understanding this definition of “valid argument”, he or she will typically make the error of assuming that a valid argument has all true premises. This is not required. There are valid arguments with false premises and a false conclusion. Here’s one:

If Miami is the capital of Kansas, then Miami is in Canada. Miami is the capital of Kansas. Therefore, Miami is in Canada.

This argument has at least one false premise: Miami is not the capital of Kansas. And the conclusion is false: Miami is not in Canada. But the argument is valid: if the premises were both true, the conclusion would have to be true. (If that bothers you, hold on a while and we will convince you that this argument is valid because of its form alone. Also, keep in mind always that “if…then…” is interpreted as meaning the conditional.)

Similarly, there are invalid arguments with true premises, and with a true conclusion. Here’s one:

If Miami is the capital of Ontario, then Miami is in Canada. Miami is not the capital of Ontario. Therefore, Miami is not in Canada.

(If you find it confusing that this argument is invalid, look at it again after you finish reading this chapter.)

Validity is about the relationship between the sentences in the argument. It is not a claim that those sentences are true.

Another variation of this confusion seems to arise when we forgot to think carefully about the conditional. The definition of valid is not “All the premises are true, so the conclusion is true.” If you don’t see the difference, consider the following two sentences. “If your house is on fire, then you should call the fire department.” In this sentence, there is no claim that your house is on fire. It is rather advice about what you should do if your house is on fire. In the same way, the definition of valid argument does not tell you that the premises are true. It tells you what follows if they are true. Contrast now, “Your house is on fire, so you should call the fire department”. This sentence delivers very bad news. It is not a conditional at all. What it really means is, “Your house is on fire and you should call the fire department”. Our definition of valid is not, “All the premises are true and the conclusion is true”.

Finally, another common mistake is to confuse true and valid . In the sense that we are using these terms in this book, only sentences can be true or false, and only arguments can be valid and invalid. When discussing and using our logical language, it is nonsense to say, “a true argument”, and it is nonsense to say, “a valid sentence”.

Someone new to logic might wonder, why would we want a definition of “good argument” that does not guarantee that our conclusion is true? The answer is that logic is an enormously powerful tool for checking arguments, and we want to be able to identify what the good arguments are, independently of the particular premises that we use in the argument. For example, there are infinitely many particular arguments that have the same form as the valid argument given above. There are infinitely many particular arguments that have the same form as the invalid argument given above. Logic lets us embrace all the former arguments at once, and reject all those bad ones at once.

Furthermore, our propositional logic will not be able to tell us whether an atomic sentence is true. If our argument is about rocks, we must ask the geologist if the premises are true. If our argument is about history, we must ask the historian if the premises are true. If our argument is about music, we must ask the music theorist if the premises are true. But the logician can tell the geologist, the historian, and the musicologist whether her arguments are good or bad, independent of the particular premises.

We do have a common term for a good argument that has true premises. This is called “sound”. It is a useful notion when we are applying our logic. Here is our definition:

Sound argument: a valid argument with true premises.

A sound argument must have a true conclusion, given the definition of “valid”.

3.3 Checking arguments semantically

Every element of our definition of “valid” is clear except for one. We know what “if…then…” means. We defined the semantics of the conditional in chapter 2. We have defined “argument”, “premise”, and “conclusion”. We take true and false as primitives. But what does “necessarily” mean?

We define a valid argument as one where, necessarily, if the premises are true, then the conclusion is true. It would seem the best way to understand this is to say, there is no situation in which the premises are true but the conclusion is false. But then, what are these “situations”? Fortunately, we already have a tool that looks like it could help us: the truth table.

Remember that in the truth table, we put on the bottom left side all the possible combinations of truth values of some set of atomic sentences. Each row of the table then represents a kind of way the world could be. Using this as a way to understand “necessarily”, we could rephrase our definition of valid to something like this, “In any kind of situation in which all the premises are true, the conclusion is true.”

Let’s try it out. We will need to use truth tables in a new way: to check an argument. That will require having not just one sentence, but several on the truth table. Consider an argument that looks like it should be valid.

If Jupiter is more massive than Earth, then Jupiter has a stronger gravitational field than Earth. Jupiter is more massive than Earth. In conclusion, Jupiter has a stronger gravitational field than Earth.

This looks like it has the form of a valid argument, and it looks like an astrophysicist would tell us it is sound. Let’s translate it to our logical language using the following translation key. (We’ve used up our letters, so I’m going to start over. We’ll do that often: assume we are starting a new language each time we translate a new set of problems or each time we consider a new example.)

P : Jupiter is more massive than Earth

Q : Jupiter has a stronger gravitational field than Earth.

This way of writing out sentences of logic and sentences of English we can call a “translation key”. We can use this format whenever we want to explain what our sentences mean in English.

Using this key, our argument would be formulated

That short line is not part of our language, but rather is a handy tradition. When quickly writing down arguments, we write the premises, and then write the conclusion last, and draw a short line above the conclusion.

This is an argument: it is an ordered list of sentences, the first two of which are premises and the last of which is the conclusion.

To make a truth table, we identify all the atomic sentences that constitute these sentences. These are P and Q . There are four possible kinds of ways the world could be that matter to us then:

We’ll write out the sentences, in the order of premises and then conclusion.

Now we can fill in the columns for each sentence, identifying the truth value of the sentence for that kind of situation.

We know how to fill in the column for the conditional because we can refer back to the truth table used to define the conditional, to determine what its truth value is when the first part and second part are true; and so on. P is true in those kinds of situations where P is true, and P is false in those kinds of situations where P is false. And the same is so for Q .

Now, consider all those kinds of ways the world could be such that all the premises are true. Only the first row of the truth table is one where all the premises are true. Note that the conclusion is true in that row. That means, in any kind of situation in which all the premises are true, the conclusion will be true. Or, equivalently: necessarily, if all the premises are true, then the conclusion is true.

Consider in contrast the second argument above, the invalid argument with all true premises and a true conclusion. We’ll use the following translation key.

R : Miami is the capital of Ontario

S : Miami is in Canada

And our argument is thus

Here is the truth table.

Note that there are two kinds of ways that the world could be in which all of our premises are true. These correspond to the third and fourth row of the truth table. But for the third row of the truth table, the premises are true but the conclusion is false. Yes, there is a kind of way the world could be in which all the premises are true and the conclusion is true; that is shown in the fourth row of the truth table. But we are not interested in identifying arguments that will have true conclusions if we are lucky. We are interested in valid arguments. This argument is invalid. There is a kind of way the world could be such that all the premises are true and the conclusion is false. We can highlight this.

Hopefully it becomes clear why we care about validity. Any argument of the form, (P→Q) and P , therefore Q , is valid. We do not have to know what P and Q mean to determine this. Similarly, any argument of the form, (R→S) and ¬R , therefore ¬S , is invalid. We do not have to know what R and S mean to determine this. So logic can be of equal use to the astronomer and the financier, the computer scientist or the sociologist.

3.4 Returning to our historical example

We described some (not all) of the hypotheses that Semmelweis tested when he tried to identify the cause of childbed fever, so that he could save thousands of women and infants. Let us symbolize these and consider his reasoning.