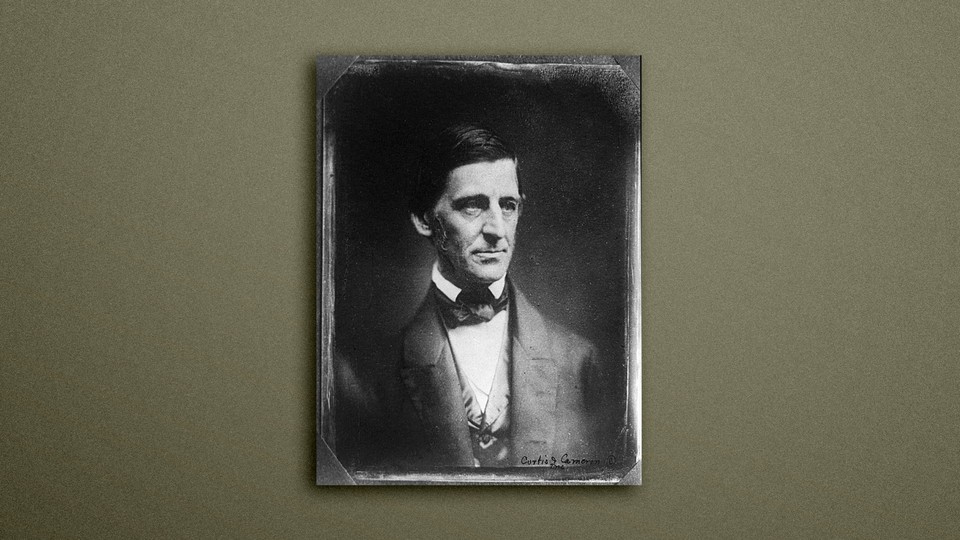

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s American Idea

He co-founded The Atlantic 162 years ago this month. His vision of progress shaped the magazine—and helped define American culture, in his time and in ours.

During Harvard University’s commencement week in 1837, Ralph Waldo Emerson took the podium at the annual meeting of the Phi Beta Kappa society. The group, composed of the top students in the graduating class, was gathered in the First Parish Church in Cambridge. Emerson, the class poet of his own Harvard class a decade before, and a writer and philosopher of growing stature, had been chosen as the honored guest to address the future intellectual elite of New England.

The event was a capstone in a week of ceremony and tradition. That changed when Emerson began to speak.

In his speech, titled “ The American Scholar ,” Emerson called for the young country to develop a national intellectual life distinct from lingering colonial influences. He also delivered an incisive critique of his audience, condemning academic scholarship for its reliance on historical and institutional wisdom. The eponymous scholar, he argued, had become “decent, indolent, complaisant.” To become more than “a mere thinker, or, still worse, the parrot of other men's thinking,” a scholar must begin to engage with the world for oneself.

Emerson was an unlikely critic of the country’s intellectual establishment. The son of a Unitarian minister, he had attended Harvard Divinity School and taken a position after graduation as a junior pastor at Boston’s Second Church. But the loss of his young wife to tuberculosis shortly after his ordination—just 16 months into their marriage—had shaken the foundation of his faith, and he had begun to chafe against the restrictions of institutionalized knowledge.

A similar frustration with New England’s dominant religious and academic culture was growing among many of the region’s other young intellectuals. In 1836, Emerson had joined a handful of them in founding the Transcendental Club. As Emerson laid out in his essay “ Nature ,” published the same year the club began, the transcendentalists sought freedom from the “poetry and philosophy of … tradition” and “religion by … history.” They believed that moral truth should be sought not in accepted wisdom, but through individual thought and experience.

With “The American Scholar,” Emerson gave voice to the movement’s individualism: envisioning an independent American intellectual culture premised not on any kind of nationalist pride—nor on any particular doctrine or political system—but on a dedication to independence itself. He would later define the “American idea” he sought to promote through his work simply as “Emancipation.”

The speech elicited praise from many of Emerson’s fellow transcendentalists and anger from the Harvard administration; after giving a similarly critical address at the divinity school the following year, he was banned from speaking on campus for three decades.

But “The American Scholar” had made its mark. Emerson’s speech left a particular impression on two members of the Harvard community, a troublemaking undergraduate named James Russell Lowell and a recent alumnus named Oliver Wendell Holmes.

“The Puritan revolt had made us ecclesiastically and the Revolution politically independent, but we were still socially and intellectually moored to English thought,” Lowell later wrote, “till Emerson cut the cable and gave us a chance at the dangers and the glories of blue water.”

Holmes called the speech America’s “intellectual Declaration of Independence.”

Emerson’s appeal for cultural independence coincided with the nationwide struggle toward another kind of emancipation. As transcendentalism began to take root in New England, abolitionism was gaining fervor across the Northern states. The debate over slavery seeped into churches, literature, and colleges, dominating conversations about America’s future.

Though he was initially hesitant to speak publicly about slavery, by the 1840s Emerson came to believe that American culture could be used to advance the cause of emancipation. He wasn’t alone: His view was shared by many other transcendentalists and prominent New England abolitionists. In May 1857, he convened at the Parker House Hotel in Boston with several of them, including Lowell, Holmes, and the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Together they founded a magazine dedicated to advocating abolitionism and promoting American voices: The Atlantic Monthly .

Read more: The birth of The Atlantic Monthly

The mission statement printed in the first issue of The Atlantic that November echoed Emerson’s expansive philosophy. The founders disavowed prejudice and promised to “be the organ of no party or clique,” and to pursue morality and truth no matter where they stemmed from or led to. They sought too to advance American writing and the “American idea” “wherever the English tongue is spoken or read”—a reflection of Emerson’s desire for a national intellectual identity that could transcend the country’s institutions and borders.

In his earlier work, Emerson had emphasized the importance of great American writers who could offer insight into national life and introduce readers to new moral truths. “We love the poet, the inventor, who in any form, whether in an ode or in an action or in looks and behavior has yielded us a new thought,” he wrote in 1844. “He unlocks our chains, and admits us to a new scene.” He saw the same potential in The Atlantic . He backed Lowell for the role of founding editor, believing that he would act as an effective guide for the publication rather than pander to its readers.

He also supported the choice to exclude bylines from early issues of The Atlantic , explaining, “The names of contributors will be given out when the names are worth more than the articles.” In fact, the magazine included the work of some of the nation’s most notable literary figures, many of them connected to Emerson through his work and his carefully cultivated intellectual circles.

As his influence had grown as a writer and lecturer, Emerson had helped inspire and support some of the 19th century’s best-known American writers. Primary among these young protégés was Henry David Thoreau, whom Emerson befriended in the late 1830s. He introduced Thoreau to transcendentalist ideas, encouraged him to begin writing journal entries and essays, and provided him land with which to conduct his experiment in simple living. In 1840, Emerson urged another friend and protégé, the journalist and women’s-rights activist Margaret Fuller, to publish Thoreau’s first essay in the Transcendental Club’s magazine, The Dial (a publication that Emerson also helped establish). Following Thoreau’s early death, in 1862, Emerson helped champion Walden and secure the book and its author vaunted positions in the pantheon of American literature.

In 1842, Emerson gave a lecture appealing for a distinctly American writer who could give voice to the yet “unsung” nation. In attendance was a 22-year-old Walt Whitman, who was determined to answer his call. “I was simmering, simmering, simmering,” Whitman later said. “Emerson brought me to a boil.”

In 1855, Whitman paid for his first collection of poetry, Leaves of Grass , to be printed at a local shop, and sent one of the first copies to Emerson. Emerson responded soon after with a laudatory letter . “I find it the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom that America has yet contributed,” he wrote.

Inspired by the positive response, Whitman passed Emerson’s letter on to an editor at the New York Tribune and quickly paid to produce a second edition of Leaves of Grass . He printed a phrase from Emerson’s letter on the book’s spine: “I greet you at the beginning of a great career.”

Read more: Walt Whitman’s “An American Primer”

Early issues of The Atlantic featured Whitman’s poetry and Thoreau’s essays , along with short stories from Louisa May Alcott , the daughter of Emerson’s close friend Bronson Alcott; Nathaniel Hawthorne , Emerson’s neighbor in Concord, Massachusetts; and Henry James , a friend of Emerson’s by way of his father. The community he had created would help establish the new magazine, and further his vision for a generation of American writers who could put the spirit of the young country into words.

Emerson’s vision of emancipation shone through in the magazine’s approach to slavery, women’s rights, and labor rights, among other topics, in the years that he served as a regular contributor. He himself became a leading voice for abolitionism in The Atlantic as the country entered the Civil War, making a passionate moral case that the nation could not survive unless slavery was extinguished.

In one of his most famous lectures, “ American Civilization ,” published in the magazine’s April 1862 issue, he reiterated his call for independence from the past. “America is another word for Opportunity,” he observed. “Our whole history appears like a last effort of the Divine Providence in behalf of the human race; and a literal slavish following of precedents, as by a justice of the peace, is not for those who at this hour lead the destinies of this people.”

He beseeched the government to abolish slavery immediately and permanently. After Abraham Lincoln issued a preliminary version of the Emancipation Proclamation six months later, Emerson hailed the measure as a “heroic” and “genius” step forward in the long fight for moral governance—a fight that would not end when slavery did, but that would continue to march toward ever greater political liberty.

In other essays for the magazine, he urged readers to seek their own freedom outside the bounds of politics. A measure of individual solitude , he wrote, was necessary for the endurance of society. He argued that power was derived from wisdom, and wisdom from the accumulation of personal experience . And the best personal experience was to be found walking in nature alone : nature that “kills egotism and conceit; deals strictly with us; and gives sanity.” Out of nature, he believed, could grow good and wise men; out of good and wise men, perhaps, a good and wise nation .

Published over the course of 50 years, his dozens of essays, poems, and lectures in The Atlantic were an encapsulation of the same vision of independence that he’d outlined in “The American Scholar” and that had, by the time he co-founded the magazine, earned him international recognition.

But while Emerson’s work was widely read in his time, none of his writing for The Atlantic —nor the hundreds of other essays, lectures, poems, and books he produced over the course of his career—has endured as popular reading in the way of contemporaneous works like Alcott’s Little Women or Whitman’s “Song of Myself.” The selections from Emerson’s expansive body of work that have found places on modern syllabi or in anthologies are, in the way of most literary classics, more often referenced than read. He remains perhaps one of the most cited American authors, but his words surface now mainly in the form of decontextualized aphorisms and inspirational quotes: “To be great is to be misunderstood,” or “Nothing can bring you peace but yourself.”

Reading Emerson’s essays, it’s not hard to understand why his words have found their most enduring currency in this form. As the literary critic Alfred Kazin observed in a July 1957 Atlantic article , “Emerson’s genius is in the sudden flash rather than in the suavely connected paragraph and page.”

His writing, on the scale of pithy phrases—or even of paragraphs or brief sections—can be eloquent, clear, moving. On the scale of whole works, however, he charts convoluted, snaking routes toward his point. He overuses rhetorical questions; he tends toward rambling tangents; he dwells overlong on obscure concepts and metaphors; he becomes mired in dense, verbose passages that are at best tangential to his core ideas.

And his ideas were often as convoluted as his writing. He enshrined individualism, urging readers to “trust thyself” rather than being drawn in by “the lustre of the firmament of bards and sages” or relying “on Property, or the … governments which protect it.” But he dismissed the idea of deep or lasting individuality, insisting that truth was ultimately universal and “within man is the soul of the whole … the eternal ONE.” He argued that society suppressed liberty and that “the less government we have, the better.” But he also asserted that “government exists to defend the weak and the poor and the injured party,” and called for the state to promote virtue and to protect and secure individual rights. He spoke out against the immorality of slavery and the forced removal of Native Americans . But he also espoused a belief in absolute racial hierarchy even decades after he became a vocal abolitionist.

Yet even these inconsistencies were consistent, in the broadest sense, with Emerson’s American idea. For him, emancipation was an eternal work in progress—dependent on an unlimited openness to change, and an endless accrual of new insights and observations. Over the course of a lifetime, he noted , any single person accumulates knowledge through successive years of education, experience, and imagination; over the course of many lifetimes, society en masse incorporates the knowledge of individuals into a broader understanding of the world. He regarded perfect understanding as unachievable, so to him, virtue lay not in achieving it but rather in trying to move closer to it—imperfectly, inconsistently, humanly, the only way it could be done.

In this way, his ideas persist at the very heart of American culture, largely decontextualized from any particular piece of his work.

“Emerson, by no means the greatest American writer .... is the inescapable theorist of virtually all subsequent American writing,” the Yale literary critic Harold Bloom wrote in a 1984 article for The New York Review of Books . “From his moment to ours, American authors either are in his tradition, or else in a countertradition originating in opposition to him.”

Even if Emerson’s most influential lectures and essays are no longer universally read, the works he helped bring to life—such as Thoreau’s Walden and Whitman’s Leaves of Grass —endure as cornerstones of the nation’s literature. His essays shaped a tradition of American essay-writing . His poetry gave rise to some of the country’s greatest poets: Emily Dickinson treasured a book of his verse; Robert Frost called him his favorite American poet. Even Hawthorne and Herman Melville, co-signers of The Atlantic ’s founding manifesto who expressed reservations about the transcendentalist movement—what Melville once, after attending one of Emerson’s lectures, referred to as “myths and oracular gibberish”—committed a distinctly Emersonian individualism to the page with characters such as Hester Prynne and Captain Ahab.

Read more: Ralph Waldo Emerson’s call to save America

Transcendentalism went on to inform subsequent generations of philosophical and religious thought, including the existential musings of Friedrich Nietzsche and the civil disobedience of Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. Though Emerson never ventured into the visual arts, he influenced the paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe and the architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright.

“Great men,” Emerson wrote , “exist that there may be greater men.” So he set out to build a culture that could evolve beyond any one moment or person, even himself.

Emerson’s house in Concord is surrounded by more famous historical sites. About a mile to the north lies the reconstructed bridge where one of the first battles of the American Revolution was fought in 1775. To the south stretches the northern shore of Walden Pond, where Thoreau retreated to “live deliberately” for two years, beginning in the summer of 1845.

Between them, the boxy white house rises up from the edge of the Cambridge Turnpike like an afterthought, an unremarkable Federal-style structure distinguished from its neighbors only by two neat signs proclaiming it to be “The Home of RALPH WALDO EMERSON.” Of the hundreds of thousands of visitors who traveled to the town in 2018 seeking some insight into the nation’s history—and some resplendent fall foliage—just 3,000 stopped by to see the home.

Emerson purchased the house in 1835, in the early stages of his new career as a writer and lecturer. When he first moved in, he set out to cultivate a garden. He planted hemlocks when his oldest son was born; pine trees after delivering “The American Scholar”; a fruit orchard as his first collection of essays launched him into international fame.

“I am present at the sowing of the seed of the world,” he wrote in 1841 . More than a century and a half later, by the side of the Cambridge Turnpike, some of the things he planted still grow.

- Corrections

What Was Emerson’s Vision for the American Scholar?

One can only wonder what the great Ralph Waldo Emerson would think of average college students today.

Ralph Waldo Emerson was a 19 th century American intellectual figure most renowned as the leading figure of the Transcendentalist movement. While his concerns about truth and the real world make most of his ideas timeless, he was just as motivated to contribute to the cultural maturation of his nation. “The American Scholar” delivers some important elements of his worldview to describe the optimal form and function of the educated man.

Surmising an Intellectual Culture

Before Emerson was a famous intellectual figure, he studied at Harvard and became a pastor at Second Church in Boston . In 1832, he resigned from his pastorship and set sail for Europe, travelling through Italy, France , and England. He journaled about his experience and publicly reflected on them in later essays, but the most important moments during his visit likely had an immediate impact on Emerson. In England, he was able to meet one-on-one with writers that he had grown to admire such as William Wordsworth and Samuel Coleridge.

These visits assured him that there was nothing inherently superior about the European writers esteemed for upholding the intellectual traditions of their nation. Emerson credited the faith these writers had in themselves as most important to their success. For him, it was important that his own nation develop a unique cultural identity and intellectual tradition, and now there was no reason to believe that America could not match Europe’s prestige.

The American Scholar

In 1837, Emerson spoke before members of the Phi Beta Kappa Society at Harvard college. This speech, “The American Scholar,” expounds the essence of learning and its connection to the life of man. Emerson describes the complete man as an idea which society reinforces despite continually pushing it towards obsolescence; as society designates individuals to pursue one specific function in their life, conceptualizing the complete man requires looking at society to see all the different roles people fill to better imagine the ideal individual proficient in every area.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

Farmers , soldiers , lawyers, priests, and all other professions are reductions of the whole man, and the scholar is likewise reduced to only using their life to think, perhaps only contemplating unoriginal ideas. However, Emerson sees potential for the scholar to build a life closest to the ideal of the complete, ideal man, shaped by three main influences: nature, the past, and action.

Emerson on Nature

One year before giving this speech, Emerson published the essay “Nature,” which gave a comprehensive overview of his own worldview and the importance of nature in it, ultimately separating him from the Christian tradition. Here, he emphasizes the scholar’s dependence on nature as a source of new information. Every area of study either edifies a part of the natural world or gestures towards something real about the world and what it’s like living in it. As more time is spent observing nature and understanding the breadth and interconnectedness of it, the scholar becomes increasingly aware of how similar it is to the human mind. The beauty and order of the mind is commensurate to the beauty and order it discovers in the natural world .

Emerson and the Past

Emerson does not completely disavow the value of old books and the ideas in them, but he stresses how important it is to be careful with them as a source of inspiration. For him, books are best appreciated as representations of their author’s life which motivate the reader to strive for a similar level of genius. He is critical of approaching books only to remember all their ideas and accept them without question. Despite the abundance of intellectual giants of past times and all their writings which make it easier for the scholar to only look to the past, one must never lose sight of their own wisdom. A life spent reading and learning without ever using it to manifest new ideas would be a life wasted.

Not all subjects are equal in this regard. Namely, history and the natural sciences require a lot more reading and memorization of old ideas before a student is equipped to write something new. When Emerson acknowledges this, he criticizes the role colleges and universities play in providing men with their educations. As good of a resource as they may be, these learning institutions serve students best when they equip and encourage young minds to become innovators and creators. Without this, he says, “…our American colleges will recede in their public importance, whilst they grow richer every year.”

Action as Complimentary to Thought

Emerson sees action as wholly complementary to thought, and it is perhaps the scholar’s most important influence since it amplifies the benefit of the other two. Any thought, original or unoriginal, cannot metamorphose into truth unless paired with relevant or proper action, which in turn encourages further thought. Furthermore, action is necessary for the scholar to immerse themselves into the real world and live their life rather than just occupy it. There is always something to learn about oneself by engaging with the real world, though nature, labor, or even interacting with other people, which sharpens the intellect to a point that cannot be replicated in isolation. Without experience, the scholar can only grow as a man of intellect, not a man of character.

A Harbor Full of Tea: The Historical Context Behind the Boston Tea Party

By Brian Daly BA Philosophy, BA English Brian holds BAs in Philosophy and English from Quinnipiac University and currently lives in New York. Whether through writing, teaching, or tutoring, he is always eager to spur interest in pondering and discussing complex ideas. His other interests include writing poetry, listening to music, and gardening.

Frequently Read Together

How Many World Fairs Did Paris Host in the 19th Century?

The Devastating Dust Bowl of the Great Depression

The American Patriot War: “The Americans Are Coming!”

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

5 Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Published: July 2015

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Emerson was a Romantic philosopher/poet who achieved fame in his own time and influenced philosophers as diverse as Friedrich Nietzsche, John Dewey, and Stanley Cavell. This chapter begins with a survey of some of the early intellectual influences on Emerson: Unitarian Christianity, Plato and Neoplatonism, Kant, Madame de Staël, Hume and Montaigne, Wordsworth and Coleridge. The discussion then turns to Concord in the 1830s: Emerson’s encounters with Margaret Fuller, Frederic Henry Hedge, and Bronson Alcott; his first book, Nature (1836); and his radical addresses, “The American Scholar” and “The Divinity School Address.” Emerson develops his mature philosophy in his essays of the 1840s and 1850s, discussed here under the following headings: Emerson’s philosophical style, self-reliance, friendship, temporality, one and many, power, fate, race, and slavery.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Developing an “American” Literature

Ralph waldo emerson, the american scholar, introduction: ralph waldo emerson (1803-1882).

Ralph Waldo Emerson, in his essays, poems, and lectures, clarified and distilled such quintessential American values as individualism, self-reliance, self-education, non-conformity, and anti-institutionalism. He asserted the individual’s intuitive grasp of immensity/divinity/soul in observable nature. He believed in a metaphysical absolute that united all life.

Emerson’s philosophy came to be called Transcendentalism. It rejected John Locke’s view of the mind as a tabula rasa and passive receptor, and saw instead an interchange between the individual mind and nature that received and created a sense of the spirit, or the Over-soul. Transcendentalism rejected institutions and dogma in favor of a person’s own individuality and independence, which was more able to maintain the inherent goodness in themselves and perception of goodness in the world around them.

Emerson was introduced to a spiritual life early, particularly through his father William Emerson (1769–1811), a Unitarian minister in Boston, who died when Emerson was eight. His mother, Ruth Haskins Emerson (1768–1853), kept boardinghouses to help support and educate her six children. Emerson was educated at the Boston Latin School in Concord and at Harvard College. From 1821 to 1825, he taught at his brother William’s Boston School for Young Ladies, and then entered Harvard Divinity School.

In 1829, Emerson was ordained as Unitarian minister of Boston’s Second Church; he also married Ellen Louisa Tucker, who died two years later from tuberculosis. Her death caused Emerson great grief and may have propelled him in 1832 to resign from his church, which he came to see as institutionalizing Christianity. Emerson later broke permanently with the Unitarian church in his “Divinity School Address” (1838), protesting the church’s having dogmatized and formalized faith, morality, and God. Emerson thought the church turned God from a living spirit and reality into a fixed convention, evoking only a historical Christianity, and thus making God seem a thing of the past and dead.

From 1832 to 1833, Emerson traveled in Europe where he met such influential writers and thinkers as William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Thomas Carlyle (1795—1881). He and Carlyle remained life-long friends. When he returned to America, Emerson settled a legal dispute over his wife’s legacy, through which he ultimately acquired an annual income of 1,000 pounds. He began lecturing around New England, married Lydia Jackson, and settled in Concord, at a house near ancestral property. In 1836, he anonymously published—at his own expense—his first book, Nature. It expressed his spiritual and transcendentalist views and drew to Concord such like-minded friends as Bronson Alcott (1799— 1888), Margaret Fuller, and Henry David Thoreau. They started The Dial (1840— 1844), a Transcendentalist journal edited mainly by Emerson, Fuller, and Thoreau.

Staying true to his individualist views, Emerson often visited but did not join the utopian experiment of Brook Farm (1841–1847), a co-operative community whose residents included Nathaniel Hawthorne and the Unitarian minister George Ripley (1802—1880). Emerson did continue to lecture across America and abroad in England and Scotland. He publicly condemned slavery in his “Emancipation of the Negroes in the British West Indies” (1841) and later attacked the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. He also supported women’s suffrage and right to own property. Emerson published a number of prose collections drawn from his lectures, including his first Essays (1841), Essays: Second Series (1844), Representative Men (1850), and The Conduct of Life (1860).

In Poems (1847) and May-Day and Other Poems (1867), he also published poetry notable for its metrical irregularity; poetry that, though disparaged by many contemporary critics, inspired the long line of Walt Whitman. Indeed, Emerson became one of Whitman’s earliest champions. Through his life and work, Emerson promoted literary nationalism and a distinctly American culture.

View the following video to get a sense of the philosophy of transcendentalism.

The American Scholar (1837)

Mr. President and Gentlemen,

I greet you on the recommencement of our literary year. Our anniversary is one of hope, and, perhaps, not enough of labor. We do not meet for games of strength or skill, for the recitation of histories, tragedies, and odes, like the ancient Greeks; for parliaments of love and poesy, like the Troubadours; nor for the advancement of science, like our contemporaries in the British and European capitals. Thus far, our holiday has been simply a friendly sign of the survival of the love of letters amongst a people too busy to give to letters any more. As such it is precious as the sign of an indestructible instinct. Perhaps the time is already come when it ought to be, and will be, something else; when the sluggard intellect of this continent will look from under its iron lids and fill the postponed expectation of the world with something better than the exertions of mechanical skill. Our day of dependence, our long apprenticeship to the learning of other lands, draws to a close. The millions that around us are rushing into life, cannot always be fed on the sere remains of foreign harvests. Events, actions arise, that must be sung, that will sing themselves. Who can doubt that poetry will revive and lead in a new age, as the star in the constellation Harp, which now flames in our zenith, astronomers announce, shall one day be the pole-star for a thousand years?

In this hope I accept the topic which not only usage but the nature of our association seem to prescribe to this day,—the American Scholar. Year by year we come up hither to read one more chapter of his biography. Let us inquire what light new days and events have thrown on his character and his hopes.

It is one of those fables which out of an unknown antiquity convey an unlookedfor wisdom, that the gods, in the beginning, divided Man into men, that he might be more helpful to himself; just as the hand was divided into fingers, the better to answer its end.

The old fable covers a doctrine ever new and sublime; that there is One Man,— present to all particular men only partially, or through one faculty; and that you must take the whole society to find the whole man. Man is not a farmer, or a professor, or an engineer, but he is all. Man is priest, and scholar, and statesman, and producer, and soldier. In the divided or social state these functions are parcelled out to individuals, each of whom aims to do his stint of the joint work, whilst each other performs his. The fable implies that the individual, to possess himself, must sometimes return from his own labor to embrace all the other laborers. But, unfortunately, this original unit, this fountain of power, has been so distributed to multitudes, has been so minutely subdivided and peddled out, that it is spilled into drops, and cannot be gathered. The state of society is one in which the members have suffered amputation from the trunk, and strut about so many walking monsters,—a good finger, a neck, a stomach, an elbow, but never a man.

Man is thus metamorphosed into a thing, into many things. The planter, who is Man sent out into the field to gather food, is seldom cheered by any idea of the true dignity of his ministry. He sees his bushel and his cart, and nothing beyond, and sinks into the farmer, instead of Man on the farm. The tradesman scarcely ever gives an ideal worth to his work, but is ridden by the routine of his craft, and the soul is subject to dollars. The priest becomes a form; the attorney a statute-book; the mechanic a machine; the sailor a rope of the ship.

In this distribution of functions the scholar is the delegated intellect. In the right state he is Man Thinking. In the degenerate state, when the victim of society, he tends to become a mere thinker, or still worse, the parrot of other men’s thinking.

In this view of him, as Man Thinking, the theory of his office is contained. Him Nature solicits with all her placid, all her monitory pictures; him the past instructs; him the future invites. Is not indeed every man a student, and do not all things exist for the student’s behalf? And, finally, is not the true scholar the only true master? But the old oracle said, “All things have two handles: beware of the wrong one.” In life, too often, the scholar errs with mankind and forfeits his privilege. Let us see him in his school, and consider him in reference to the main influences he receives.

I. The first in time and the first in importance of the influences upon the mind is that of nature. Every day, the sun; and, after sunset, Night and her stars. Ever the winds blow; ever the grass grows. Every day, men and women, conversing, beholding and beholden. The scholar is he of all men whom this spectacle most engages. He must settle its value in his mind. What is nature to him? There is never a beginning, there is never an end, to the inexplicable continuity of this web of God, but always circular power returning into itself. Therein it resembles his own spirit, whoso beginning, whose ending, he never can find,—so entire, so boundless. Far too as her splendors shine, system on system shooting like rays, upward, downward, without centre, without circumference,—in the mass and in the particle, Nature hastens to render account of herself to the mind. Classification begins. To the young mind every thing is individual, stands by itself. By and by, it finds how to join two things and see in them one nature; then three, then three thousand; and so, tyrannized over by its own unifying instinct, it goes on tying things together, diminishing anomalies, discovering roots running under ground whereby contrary and remote things cohere and flower out from one stem. It presently learns that since the dawn of history there has been a constant accumulation and classifying of facts. But what is classification but the perceiving that these objects are not chaotic, and are not foreign, but have a law which is also a law of the human mind? The astronomer discovers that geometry, a pure abstraction of the human mind, is the measure of planetary motion. The chemist finds proportions and intelligible method throughout matter; and science is nothing but the finding of analogy, identity, in the most remote parts. The ambitious soul sits down before each refractory fact; one after another reduces all strange constitutions, all new powers, to their class and their law, and goes on forever to animate the last fibre of organization, the outskirts of nature, by insight.

Thus to him, to this school-boy under the bending dome of day, is suggested that he and it proceed from one root; one is leaf and one is flower; relation, sympathy, stirring in every vein. And what is that root? Is not that the soul of his soul? A thought too bold; a dream too wild. Yet when this spiritual light shall have revealed the law of more earthly natures,—when he has learned to worship the soul, and to see that the natural philosophy that now is, is only the first gropings of its gigantic hand, he shall look forward to an ever expanding knowledge as to a becoming creator. He shall see that nature is the opposite of the soul, answering to it part for part. One is seal and one is print. Its beauty is the beauty of his own mind. Its laws are the laws of his own mind. Nature then becomes to him the measure of his attainments. So much of nature as he is ignorant of, so much of his own mind does he not yet possess. And, in fine, the ancient precept, “Know thyself,” and the modern precept, “Study nature,” become at last one maxim.

II. The next great influence into the spirit of the scholar is the mind of the Past,—in whatever form, whether of literature, of art, of institutions, that mind is inscribed. Books are the best type of the influence of the past, and perhaps we shall get at the truth,—learn the amount of this influence more conveniently,—by considering their value alone.

The theory of books is noble. The scholar of the first age received into him the world around; brooded thereon; gave it the new arrangement of his own mind, and uttered it again. It came into him life; it went out from him truth. It came to him short-lived actions; it went out from him immortal thoughts. It came to him business; it went from him poetry. It was dead fact; now, it is quick thought. It can stand, and it can go. It now endures, it now flies, it now inspires. Precisely in proportion to the depth of mind from which it issued, so high does it soar, so long does it sing.

Or, I might say, it depends on how far the process had gone, of transmuting life into truth. In proportion to the completeness of the distillation, so will the purity and imperishableness of the product be. But none is quite perfect. As no airpump can by any means make a perfect vacuum, to neither can any artist entirely exclude the conventional, the local, the perishable from his book, or write a book of pure thought, that shall be as efficient, in all respects, to a remote posterity, as to contemporaries, or rather to the second age. Each age, it is found, must write its own books; or rather, each generation for the next succeeding. The books of an older period will not fit this.

Yet hence arises a grave mischief. The sacredness which attaches to the act of creation, the act of thought, is transferred to the record. The poet chanting was felt to be a divine man: henceforth the chant is divine also. The writer was a just and wise spirit: henceforward it is settled the book is perfect; as love of the hero corrupts into worship of his statue. Instantly the book becomes noxious: the guide is a tyrant. The sluggish and perverted mind of the multitude, slow to open to the incursions of Reason, having once so opened, having once received this book, stands upon it, and makes an outcry if it is disparaged. Colleges are built on it. Books are written on it by thinkers, not by Man Thinking; by men of talent, that is, who start wrong, who set out from accepted dogmas, not from their own sight of principles. Meek young men grow up in libraries, believing it their duty to accept the views which Cicero, which Locke, which Bacon, have given; forgetful that Cicero, Locke, and Bacon were only young men in libraries when they wrote these books.

Hence, instead of Man Thinking, we have the bookworm. Hence the booklearned class, who value books, as such; not as related to nature and the human constitution, but as making a sort of Third Estate with the world and the soul. Hence the restorers of readings, the emendators, the bibliomaniacs of all degrees.

Books are the best of things, well used; abused, among the worst. What is the right use? What is the one end which all means go to effect? They are for nothing but to inspire. I had better never see a book than to be warped by its attraction clean out of my own orbit, and made a satellite instead of a system. The one thing in the world, of value, is the active soul. This every man is entitled to; this every man contains within him, although in almost all men obstructed, and as yet unborn. The soul active sees absolute truth and utters truth, or creates. In this action it is genius; not the privilege of here and there a favorite, but the sound estate of every man. In its essence it is progressive. The book, the college, the school of art, the institution of any kind, stop with some past utterance of genius. This is good, say they,—let us hold by this. They pin me down. They look backward and not forward. But genius looks forward: the eyes of man are set in his forehead, not in his forehead, man hopes: genius creates. Whatever talents may be, if the man create not, the pure efflux of the Deity is not his;—cinders and smoke there may be, but not yet flame. There are creative manners, there are creative actions, and creative words; manners, actions, words, that is, indicative of no custom or authority, but springing spontaneous from the mind’s own sense of good and fair.

On the other part, instead of being its own seer, let it receive from another mind its truth, though it were in torrents of light, without periods of solitude, inquest, and self-recovery, and a fatal disservice is done. Genius is always sufficiently the enemy of genius by over-influence. The literature of every nation bears me witness. The English dramatic poets have Shakspearized now for two hundred years.

Undoubtedly there is a right way of reading, so it be sternly subordinated. Man Thinking must not be subdued by his instruments. Books are for the scholar’s idle times. When he can read God directly, the hour is too precious to be wasted in other men’s transcripts of their readings. But when the intervals of darkness come, as come they must,—when the sun is hid and the stars withdraw their shining,—we repair to the lamps which were kindled by their ray, to guide our steps to the East again, where the dawn is. We hear, that we may speak. The Arabian proverb says, “A fig tree, looking on a fig tree, becometh fruitful.”

It is remarkable, the character of the pleasure we derive from the best books. They impress us with the conviction that one nature wrote and the same reads We read the verses of one of the great English poets, of Chaucer, of Marvell, of Dryden, with the most modern joy,—with a pleasure, I mean, which is in great part caused by the abstraction of all time from their verses. There is some awe mixed with the joy of our surprise, when this poet, who lived in some past world, two or three hundred years ago, says that which lies close to my own soul, that which I also had well-nigh thought and said. But for the evidence thence afforded to the philosophical doctrine of the identity of all minds, we should suppose some preëstablished harmony, some foresight of souls that were to be, and some preparation of stores for their future wants, like the fact observed in insects, who lay up food before death for the young grub they shall never see.

I would not be hurried by any love of system, by any exaggeration of instincts, to underrate the Book. We all know, that as the human body can be nourished on any food, though it were boiled grass and the broth of shoes, so the human mind can be fed by any knowledge. And great and heroic men have existed who had almost no other information than by the printed page. I only would say that it needs a strong head to bear that diet. One must be an inventor to read well. As the proverb says, “He that would bring home the wealth of the Indies, must carry out the wealth of the Indies.” There is then creative reading as well as creative writing. When the mind is braced by labor and invention, the page of whatever book we read becomes luminous with manifold allusion. Every sentence is doubly significant, and the sense of our author is as broad as the world. We then see, what is always true, that as the seer’s hour of vision is short and rare among heavy days and months, so is its record, perchance, the least part of his volume. The discerning will read, in his Plato or Shakspeare, only that least part,—only the authentic utterances of the oracle;—all the rest he rejects, were it never so many times Plato’s and Shakspeare’s.

Of course there is a portion of reading quite indispensable to a wise man. History and exact science he must learn by laborious reading. Colleges, in like manner, have their indispensable office,—to teach elements But they can only highly serve us when they aim not to drill, but to create; when they gather from far every ray of various genius to their hospitable halls, and by the concentrated fires, set the hearts of their youth on flame. Thought and knowledge are natures in which apparatus and pretension avail nothing. Gowns and pecuniary foundations, though of towns of gold, can never countervail the least sentence or syllable of wit. Forget this, and our American colleges will recede in their public importance, whilst they grow richer every year.

III. There goes in the world a notion that the scholar should be a recluse, a valetudinarian,—as unfit for any handiwork or public labor as a penknife for an axe. The so-called “practical men” sneer at speculative men, as if, because they speculate or see, they could do nothing. I have heard it said that the clergy,—who are always, more universally than any other class, the scholars of their day,—are addressed as women; that the rough, spontaneous conversation of men they do not hear, but only a mincing and diluted speech. They are often virtually disfranchised; and indeed there are advocates for their celibacy. As far as this is true of the studious classes, it is not just and wise. Action is with the scholar subordinate, but it is essential. Without it he is not yet man. Without it thought can never ripen into truth. Whilst the world hangs before the eye as a cloud of beauty, we cannot even see its beauty. Inaction is cowardice, but there can be no scholar without the heroic mind. The preamble of thought, the transition through which it passes from the unconscious to the conscious, is action. Only so much do I know, as I have lived. Instantly we know whose words are loaded with life, and whose not.

The world,—this shadow of the soul, or other me, lies wide around. Its attractions are the keys which unlock my thoughts and make me acquainted with myself. I run eagerly into this resounding tumult. I grasp the hands of those next me, and take my place in the ring to suffer and to work, taught by an instinct that so shall the dumb abyss be vocal with speech. I pierce its order; I dissipate its fear; I dispose of it within the circuit of my expanding life. So much only of life as I know by experience, so much of the wilderness have I vanquished and planted, or so far have I extended my being, my dominion. I do not see how any man can afford, for the sake of his nerves and his nap, to spare any action in which he can partake. It is pearls and rubies to his discourse. Drudgery, calamity, exasperation, want, are instructors in eloquence and wisdom. The true scholar grudges every opportunity of action past by, as a loss of power.

It is the raw material out of which the intellect moulds her splendid products. A strange process too, this by which experience is converted into thought, as a mulberry leaf is converted into satin. The manufacture goes forward at all hours.

The actions and events of our childhood and youth are now matters of calmest observation. They lie like fair pictures in the air. Not so with our recent actions,— with the business which we now have in hand. On this we are quite unable to speculate. Our affections as yet circulate through it. We no more feel or know it than we feel the feet, or the hand, or the brain of our body. The new deed is yet a part of life,—remains for a time immersed in our unconscious life. In some contemplative hour it detaches itself from the life like a ripe fruit, to become a thought of the mind. Instantly it is raised, transfigured; the corruptible has put on in-corruption. Henceforth it is an object of beauty, however base its origin and neighborhood. Observe too the impossibility of antedating this act. In its grub state, it cannot fly, it cannot shine, it is a dull grub. But suddenly, without observation, the selfsame thing unfurls beautiful wings, and is an angel of wisdom. So is there no fact, no event, in our private history, which shall not, sooner or later, lose its adhesive, inert form, and astonish us by soaring from our body into the empyrean. Cradle and infancy, school and playground, the fear of boys, and dogs, and ferules, the love of little maids and berries, and many another fact that once filled the whole sky, are gone already; friend and relative, profession and party, town and country, nation and world, must also soar and sing.

Of course, he who has put forth his total strength in fit actions has the richest return of wisdom. I will not shut myself out of this globe of action, and transplant an oak into a flower-pot, there to hunger and pine; nor trust the revenue of some single faculty, and exhaust one vein of thought, much like those Savoyards, who, getting their livelihood by carving shepherds, shepherdesses, and smoking Dutchmen, for all Europe, went out one day to the mountain to find stock, and discovered that they had whittled up the last of their pine-trees. Authors we have, in numbers, who have written out their vein, and who, moved by a commendable prudence, sail for Greece or Palestine, follow the trapper into the prairie, or ramble round Algiers, to replenish their merchantable stock.

If it were only for a vocabulary, the scholar would be covetous of action. Life is our dictionary. Years are well spent in country labors; in town; in the insight into trades and manufactures; in frank intercourse with many men and women; in science; in art; to the one end of mastering in all their facts a language by which to illustrate and embody our perceptions. I learn immediately from any speaker how much he has already lived, through the poverty or the splendor of his speech. Life lies behind us as the quarry from whence we get tiles and copestones for the masonry of to-day. This is the way to learn grammar. Colleges and books only copy the language which the field and the work-yard made.

But the final value of action, like that of books, and better than books, is that it is a resource. That great principle of Undulation in nature, that shows itself in the inspiring and expiring of the breath; in desire and satiety; in the ebb and flow of the sea; in day and night; in heat and cold; and, as yet more deeply ingrained in every atom and every fluid, is known to us under the name of Polarity,—these “fits of easy transmission and reflection,” as Newton called them,—are the law of nature because they are the law of spirit.