Iron Age Art in Europe

Dates, artifacts, artists, Celtic culture, Britain, Ireland

Main A-Z Index

What Exactly is the Iron Age?

When did the iron age start, when did the iron age end, art in the iron age (1200-200 bc), ancient greece & etruria, classical period, hellenistic period, northern/central europe, celtic ireland and britain.

The Iron Age is the third and final phase of the traditional lopsided chronology of human life on Earth.

The first phase, lasting for roughly 3.3 million years, is known as the Stone Age . This is subdivided into Paleolthic, Mesolithic and Neolithic perods. See also: Stone Age Culture .

The second phase, lasting about 2,000 years, is called the Bronze Age .

While dates for the Stone Age are pretty much the same for all regions of the world, the Bronze and Iron Ages vary region by region, according to their development of bronze and iron metallurgy.

The three-age timeline was first used by the Danish Antiquarian Christian Jürgensen Thomsen (1788-1865) in an archaeological context, during the first half of the 19th century, to reflect the three different materials from which tools were made: stone, bronze, and iron.

The exact date of the Iron Age varies by geographical region.

Basically, the Iron Age begins when a region's use of bronze - in the manufacture of tools, weapons and other implements - is superceded by the use of iron and steel.

In the Middle East, this transition occurred during the 12th century BC, and quickly spread throughout the Mediterranean region and to Southern Asia. During the period 1,100 and 450 BC, the Iron Age spread to Central Asia, Eastern Europe, Central, and Northern Europe.

The end of the Iron Age is equally variable. In the Middle East, for instance, it is said to end with the establishment of the Persian Achaemenid Empire by Cyrus the Great, about 550 BC.

For details of early Iron Age cultures in the Middle East between 4,000 and 539 BC, see:

- Mesopotamian Art & Culture

- Sumerian Culture

- Babylonian Art

- Assyrian Art

- Hittite Art

However, in Central and Western Europe, the end of the Iron Age is said to coincide with the victorious Roman campaigns of the 1st century BC, while in Scandinavia, the Iron Age coincides with the beginning of the Viking Age, around 800 AD.

Digging Up Our Past

For a short guide to studying the ancient world, see: Archaeology: Prehistoric & Ancient . For an explanation of terms used, see: Archaeology Glossary .

In this article, we briefly outline the main trends and styles of ancient art , between 1,200 and 200 BC, which also includes post-Iron Age works in some areas.

Please note that art created during the Iron Age was rarely connected to the metal 'iron'. After all, bronze was far more decorative and visual material. As a rule, the artistic use of iron was limited to the embellishment of weapons and horse tack.

Related Articles

- Paleolithic Culture

- Mesolithic Culture

- Neolithic Culture

By contrast with the Stone Age and Bronze Age, development during the Iron Age was faster and more visible. It included the widespread proliferation of iron and steel tools, resulting in a huge increase in demand for metals and metalworkers, notably around the eastern Mediterranean.

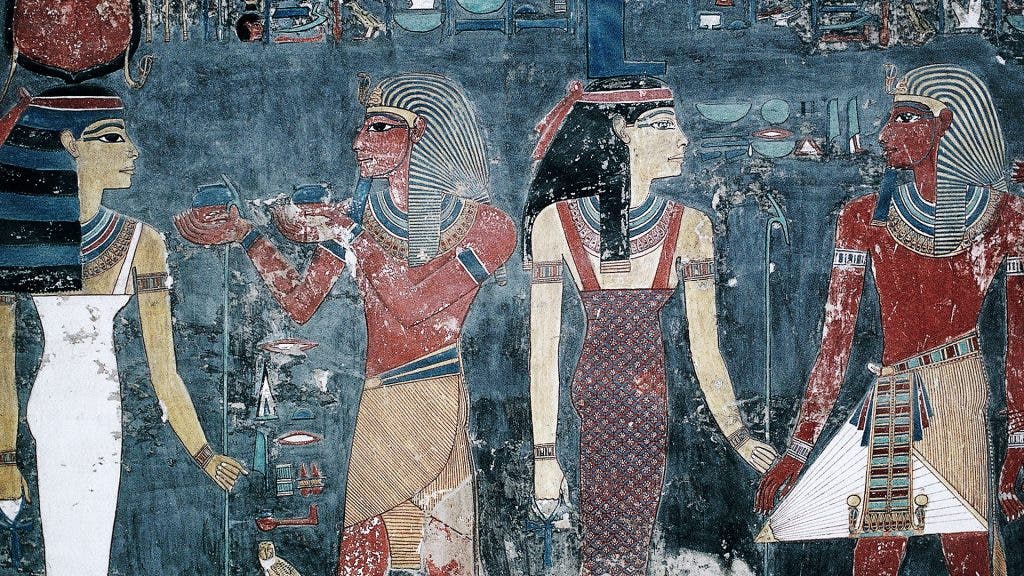

Some nations, however, responded better than others. The heyday of Ancient Egyptian architecture had passed - the quality of Egyptian pyramids , for example, had slumped, although Egyptian temples continued to flourish, and Ancient Egyptian Art was copied everywhere.

In addition, the Minoan civilization on Crete had collapsed, and the rival Mycenean civilization was also in decline.

But from about 900 BC the cultures of mainland Greece - especially those of Athens and Corinth - began to thrive.

Ancient Greek pottery , Greek sculpture and Greek architecture, were the first Iron Age arts to really impress, although painting retained its status as the highest form of art. Sadly, almost no Greek painting has survived, apart from a range of murals.

Etruscan art also appeared, but it was the style and quality of Hellenic culture which dominated the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant, along with Egyptian and Persian art.

It was only after Greece began to lose its power from 200 BC onwards, that Roman art emerged, and this was created largely by Greek artists in the Hellenic style.

In the history of art, the civilization of Classical Antiquity is divided into several periods. These include:

- The Dark Ages (1200-900 BC)

- The Geometric Period (900-700 BC)

- The Oriental-Style Period (700-625 BC)

- The Archaic Period (625-500 BC)

- The Classical Period (500-323 BC)

- The Hellenistic Period (323-27 BC)

During the Dark Ages, the Greek world was disrupted by external pressures, including invasion. The smaller, poorer kingdoms and city-states which emerged, could not afford the arts and culture that had flourished in the Bronze Age palaces of the Minoan and Mycenaean empires.

As a result, the arts declined. Fortunately, by 900 BC, Athens managed to reassert itself, and art forms like ancient pottery regained their former importance.

During the Geometric Period , for instance, ceramic objects were decorated with geometric patterns, while during the Orientalist Period , vases depicted heroic scenes from Greek history.

During the Archaic phase , historical motifs were initially superceded by animal or human figures, although by 500 BC more complex mythological scenes had returned.

Throughout the first four periods of the Iron Age, monumental art - in the form of architectural painting and decoration - also appeared. For example, temples, shrines and other public buildings were decorated with friezes and murals.

The highpoint of Greek art occurred during the so-called 'Classical' period, just as the Iron Age was coming to a close in the region.

During the Classical Period, Greek art became more dignified. Painting depicted military successes.

Noted painters included Apollodorus (invented skiagraphia or shadow-painting), Apelles, Micon, Parrhasius, Polygnotus, and Zeuxis. Linear-style as well as more subtle shading styles were developed.

Relief, pedimental and free-standing sculpture proliferated during the three phases of classical Greek art: Early Classical, High Classical and Late Classical.

Famous Greek sculptors included: included: Kalamis (fl. 470-440 BC), Pythagoras (fl.440-420), Phidias (488-431), Kresilas (480-410), Myron (fl. 480-444), Polykleitos (fl.450-430), Callimachus (fl. 432-408), Skopas (fl. 395-350), Lysippos (fl.395-305), Praxiteles (fl. 375-335), and Leochares (fl. 340-320).

The Parthenon (447-438 BC) and other temples on the Athenian acropolis, contained a wide variety of stone, marble and chryselephantine sculpture of the High and Late Classical periods.

Famous examples of classical Greek sculptures include:

- Discobolus (450 BC) by Myron

- Doryphorus (440 BC) by Polykleitos

- Aphrodite of Knidos (350 BC) by Praxiteles

- Apollo Belvedere (330 BC) by Leochares

- The Farnese Hercules (350 BC) by Lysippos

The Hellenistic Period, which traditionally begins upon the death of Alexander the Great, witnessed more developments in Greek painting and sculpture.

Artists were employed by rulers who utilized their talents to champion their secular image. At the same time, as Rome gained in military power, art in Etruria began to improve. For example, Etruscan tomb painting begins to employ a sophisticated form of chiaroscuro.

Famous examples of Hellenistic Greek sculptures include:

- Colossus of Rhodes (292 BC) By Chares of Lindos

- Dying Gaul (c.240 BC) Musei Capitolini, Rome. By Epigonus

- Winged Victory of Samothrace (Nike) (220 BC) anonymous

- Farnese Hercules (350 BC) by Lysippos

- Venus de Milo (Aphrodite of Melos) (100 BC) anonymous

- Laocoon (42 BC) By Hagesander, Athenodoros, Polydorus

Roman sculpture and painting remained forever in the shadow of Greek styles and craftsmanship. Only Roman architecture rivalled that of Ancient Greece, due to the Roman expertise in engineering and the use of new materials like concrete.

No secure cities emerged in Northern or Central Europe during this time. As a result, there were fewer resources or opportunities for painting, sculpture or architecture.

Only painted pottery continued to be made, as one would expect from a region that created some of the world's earliest ceramic art at Vela Spila (15,500 BC).

Apart from this, art was limited mostly to personal adornments, cooking or drinking vessels, as well as the ornamentation of weaponry, horse tack, boats and other functional items.

Not surprisingly, therefore, Iron Age art in Northern and Central Europe was dominated by the Celts, whose ironsmiths and blacksmiths were the finest in the region.

The most famous Celtic styles of central Europe were the Hallstatt culture (800-450 BC) and La Tène culture (450-50 BC) culture.

Examples of famous Celtic smithery include the Basse-Yutz Flagons (450 BC), made from copper alloy, coral, glass and resin, found in France; the gold and bronze Oak Tree of Manching (350-50 BC), found in Germany, and the silver Gundestrup Cauldron (100 BC), found in Denmark.

By 1100 BC, the Celts - a collection of Indo-European tribes - had established themselves astride the main trading routes along the main European waterways, including the Rhone, the Rhine and the Danube.

During the period 1,100 and 700 BC, they became the first non-Mediterranean people to practice iron metallurgy, which gave them a significant technological advantage over their neighbours throughout the Continent.

Following intermittent contacts between themselves and the indigenous population of Britain and Ireland during the Stone and Bronze ages, the first wave of iron-using Celts arrived in Britain and Ireland around 500 BC.

This group belonged to the Hallstatt culture. Two centuries later, Celts of the La Tène culture arrived.

As a result, within a few hundred years Ireland's Bronze Age culture became almost completely dominated by Celtic art and culture.

The earliest Irish Iron Age artifacts (Hallstat culture) of this period included: ceremonial drinking vessels, necklaces, hair pins, weapons and other Celtic metalwork. Later La Tène artifacts included several items of great delicate beauty, including:

- The bronze Loughnashade Horn (100 BC)

- The bronze Petrie Crown (100 BC - 200 AD)

- The gold Broighter Collar (1st century BC)

- The gold Broighter Boat (1st century BC)

In addition, Celtic influence can be seen in Irish monumental pagan sculpture, like the granite Turoe Stone (150-250 BC).

Celtic Iron Age treasures found in Britain. include: the bronze Battersea Shield (350 BC); the bronze Witham Shield (4th century BC); and the gold alloy Snettisham Great Torc (100-75 BC).

(1) Collis, John. The European Iron Age. London: B.T. Batsford, 1984. (2) Cunliffe, Barry W. Iron Age Britain. Rev. ed. London: Batsford, 2004. (3) Medvedskaia, I. N. Iran: Iron Age I. Oxford: B.A.R., 1982. (4) Waldbaum, Jane C. From Bronze to Iron: The Transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age in the Eastern Mediterranean. Göteborg: P. Aström, 1978.

Back to top

500BC-400AD The Iron Age in Ireland: Hillforts, Art, and the Arrival of the Celts

Introduction: transitioning to the iron age.

Following the Bronze Age, Ireland embarked on a new epoch known as the Iron Age, beginning around 500 BC. This era, distinguished by its dominant use of iron for tools and weapons, heralded significant societal, architectural, and cultural advancements. Most notably, the Iron Age marked the arrival of the Celts, leaving an indelible mark on Ireland’s history.

Iron: The Metal that Transformed a Culture

The Iron Age, as the name suggests, was characterized by the introduction and proliferation of iron.

- Superiority of Iron : Iron, once smelted and shaped, was harder and more durable than bronze, making it a preferred choice for a range of items from household tools to weapons of war.

- Sources and Smithing : Ireland, rich in bog iron, became a focal point for extraction. The blacksmiths of the era developed techniques to smelt and forge iron, producing items of both utility and artistry.

Hillforts: The Architectural Marvels of the Iron Age

During the Iron Age, Ireland saw the rise of hillforts—fortified settlements predominantly situated on hilltops.

- Strategic and Defensive : These forts, often encircled by earthen or stone walls, served as defensive structures. Their elevated positions provided strategic advantages against potential invaders.

- Centers of Authority : Beyond their defensive purpose, hillforts were likely symbols of power and control. They might have been residences of local chieftains or places of communal gathering.

- Prominent Examples : Dun Ailinne in Co. Kildare and Emain Macha in Co. Armagh are two iconic hillforts that underscore the era’s architectural prowess.

Artistic Flourish: Iron Age Aesthetics

Art didn’t take a back seat during the Iron Age. Instead, it saw an evolution in style and medium.

- Metalwork Masterpieces : With iron and other metals like gold being prevalent, metalwork items often bore intricate designs. The famed Broighter Gold Hoard, discovered in Co. Londonderry, is a testament to the era’s ornate craftsmanship.

- Stone Carvings and Sculptures : Stone continued to be a favorite medium for artistic expressions, with numerous carvings and sculptures echoing Celtic influences.

The Celts: A Formidable Influence on Iron Age Ireland

The Iron Age in Ireland is closely intertwined with the Celts, a group of Indo-European tribes.

- Arrival and Settlement : While the exact timeline of the Celtic arrival in Ireland is debated, their influence during the Iron Age is undeniable. Migrating from Central Europe, the Celts brought with them a distinct culture, language, and artistry.

- Celtic Language : The Celts were speakers of early Irish, from which modern Irish (Gaeilge) has evolved. Their linguistic impact laid the foundation for Ireland’s rich oral and written traditions.

- Religious Practices : The druids, often associated with the Celts, were religious leaders and advisors. Sacred groves, ritualistic ceremonies, and the festival of Samhain (a precursor to modern-day Halloween) were hallmarks of their spiritual practices.

Social Structures: Chiefs, Warriors, and Craftsmen

The societal fabric of Iron Age Ireland was multifaceted, reflecting a range of roles and hierarchies.

- Chieftains and Kings : Local rulers or chieftains, often residing in hillforts, wielded power and authority. Over time, powerful kings emerged, controlling larger territories.

- Warrior Class : With the advent of superior iron weapons, a distinct warrior class rose to prominence. Their role wasn’t just defensive; they were also central to power dynamics and territorial disputes.

- Craftsmen and Artisans : Specialized craftsmen, particularly blacksmiths, were crucial to Iron Age society. Their ability to forge tools, weapons, and artistic items made them invaluable.

Economy and Trade: Beyond the Island’s Shores

The Iron Age wasn’t an era of isolation for Ireland. Economic activities and trade flourished.

- Agriculture and Livestock : As in previous ages, farming played a central role. Iron tools enhanced agricultural productivity, while livestock breeding remained a staple economic activity.

- Trade Networks : Iron Age Ireland engaged in trade with neighboring regions. Goods, metals, and even ideas were exchanged, connecting Ireland to a broader European network.

Navigating through Myths and Reality

The Iron Age, being on the cusp of recorded history, often blends facts with myths. Legendary tales, like those of Cú Chulainn and the Red Branch Knights, while rooted in this era, are interwoven with folklore, adding a layer of mystique to this already fascinating period.

In unraveling the intricacies of the Iron Age in Ireland, one encounters a vibrant tapestry of innovations, cultural exchanges, and societal evolutions. From the iron-smithing hearths to the imposing hillforts, and from the enigmatic druids to the spirited Celtic warriors, the Iron Age stands as a dynamic and transformative chapter in Ireland’s vast historical saga.

Did you find this helpful?

Related posts.

The End of Brehon Laws: The Influence of the Normans and the English Common Law

Key Principles of Brehon Laws: Kinship, Honor Price, and Fines

4: The Bronze Age and the Iron Age

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 17008

- Christopher Brooks

- Portland Community College

The Bronze Age is a term used to describe a period in the ancient world from about 3000 BCE to 1100 BCE. That period saw the emergence and evolution of increasingly sophisticated ancient states, some of which evolved into real empires. It was a period in which long-distance trade networks and diplomatic exchanges between states became permanent aspects of political, economic, and cultural life in the eastern Mediterranean region. It was, in short, the period during which civilization itself spread and prospered across the area.

The period is named after one of its key technological bases: the crafting of bronze. Bronze is an alloy of tin and copper. An alloy is a combination of metals created when the metals bond at the molecular level to create a new material entirely. Needless to say, historical peoples had no idea why, when they took tin and copper, heated them up, and beat them together on an anvil they created something much harder and more durable than either of their starting metals. Some innovative smith did figure it out, and in the process ushered in an array of new possibilities.

Bronze was important because it revolutionized warfare and, to a lesser extent, agriculture. The harder the metal, the deadlier the weapons created from it and the more effective the tools. Agriculturally, bronze plows allowed greater crop yields. Militarily, bronze weapons completely shifted the balance of power in warfare; an army equipped with bronze spear and arrowheads and bronze armor was much more effective than one wielding wooden, copper, or obsidian implements.

An example of bronze’s impact is, as noted in the previous chapter, the expansionism of the New Kingdom. The New Kingdom of Egypt conquered more territory than any earlier Egyptian empire. It was able to do this in part because of its mastery of bronze-making and the effectiveness of its armies as a result. The New Kingdom also demonstrates another noteworthy aspect of bronze: it was expensive to make and expensive to distribute to soldiers, meaning that only the larger and richer empires could afford it on a large scale. Bronze tended to stack the odds in conflicts against smaller city-states and kingdoms, because it was harder for them to afford to field whole armies outfitted with bronze weapons. Ultimately, the power of bronze contributed to the creation of a whole series of powerful empires in North Africa and the Middle East, all of which were linked together by diplomacy, trade, and (at times) war.

- 4.1: The Bronze Age States There were four major regions along the shores of, or near to, the eastern Mediterranean that hosted the major states of the Bronze Age: Greece, Anatolia, Canaan and Mesopotamia, and Egypt. Those regions were close enough to one another that ongoing long-distance trade was possible. While wars were relatively frequent, most interactions between the states and cultures of the time were peaceful, revolving around trade and diplomacy.

- 4.2: The Collapse of the Bronze Age The Bronze Age at its height witnessed several large empires and peoples in regular contact with one another through both trade and war. Most of the states fell into ruin between 1200 - 1100 BCE. The great empires collapsed, a collapse that it took about 100 years to recover from, with new empires arising in the aftermath. There is still no definitive explanation for why this collapse occurred, in part because the states that had been keeping records stopped doing so as their empires collapsed.

- 4.3: The Iron Age he decline of the Bronze Age led to the beginning of the Iron Age. Bronze was dependent on functioning trade networks: tin was only available in large quantities from mines in what is today Afghanistan, so the collapse of long-distance trade made bronze impossible to manufacture. Iron, however, is a useful metal by itself without the need of alloys (although early forms of steel - iron alloyed with carbon, which is readily available everywhere - were around almost from the start of the Iron Age

- 4.4: Iron Age Cultures and States The Phoenicians were not a particularly warlike people. of their various accomplishments, none was to have a more lasting influence than that of their writing system. As early as 1300 BCE, building on the work of earlier Canaanites, the Phoenicians developed a syllabic alphabet that formed the basis of Greek and Roman writing much later. Another was a practice - the use of currency - originating in the remnants of the Hittite lands.

- 4.5: Empires of the Iron Age The period of political breakdown in Mesopotamia following the collapse of the Bronze Age ended in about 880 BCE when the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II began a series of wars to conquer Mesopotamia and Canaan. Over the next century, the (Neo-)Assyrians became the mightiest empire yet seen in the Middle East. They combined terror tactics with various technological and organizational innovations.

- 4.6: Ancient Hebrew History The Hebrews, a people who first created a kingdom in the ancient land of Canaan, were among the most important cultures of the western world, comparable to the ancient Greeks or Romans. Unlike the Greeks and Romans, the ancient Hebrews were not known for being scientists or philosophers or conquerors. It was their religion, Judaism, that proved to be of crucial importance in world history, both for its own sake and for being the religious root of Christianity and Islam.

- 4.7: The Kings and Kingdoms The Hebrew kingdom itself was fairly rich, thanks to its good spot on trade routes and the existence of gold mines, but Solomon's ongoing taxation and labor demands were such that resentment developed among the Hebrews over time. After his death, fully ten out of the twelve tribes broke off to form their own kingdom, retaining the name Israel, while the smaller remnant of the kingdom took on the name Judah.

- 4.8: The Yahwist Religion and Judaism As the Hebrews became more powerful, their religion changed dramatically. A tradition of prophets - the Prophetic Movement - arose among certain people who sought to represent the poorer and more beleaguered member of the community, calling for a return to the more communal and egalitarian society of the past. The Prophetic Movement claimed that the Hebrews should worship Yahweh exclusively, and that Yahweh had a special relationship with the Hebrews that set Him apart as a God.

- 4.9: Conclusion What all of the cultures considered in this chapter have in common is that they were more dynamic and, in the case of the empires, more powerful than earlier Mesopotamian (and even Egyptian) states. In a sense, the empires of the Bronze Age and, especially, the Iron Age represented different experiments in how to build and maintain larger economic systems and political units than had been possible earlier.

Thumbnail: Death mask, known as the Mask of Agamemnon, Grave Circle A, Mycenae, 16th century BCE, probably the most famous artifact of Mycenaean Greece . (CC BY 2.5; Xuan Che via Wikipedia).

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

The Oxford Handbook of the European Iron Age

Colin Haselgrove, University of Leicester

Katharina Rebay-Salisbury, University of Vienna

Peter S. Wells, University of Minnesota

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The Oxford Handbook of the European Iron Age presents to students, scholars, and interested general readers a broad overview of current understanding of the archaeology of Europe from 1000 bc to the early historic period. During this period, new technologies, agricultural innovation, and demographic growth saw much of the landscape opened up to near modern limits, accompanied in many areas by greater social and economic complexity. Three introductory chapters situate the reader in the times and the environments of Iron Age Europe. Fourteen regional chapters provide overviews of developments in different parts of the continent, from Ireland and Spain in the west to the borders with Asia in the east, and from Scandinavia in the north to the Mediterranean shores in the south, exploiting the large quantities of new evidence yielded by the upsurge in archaeological research and excavation on this period over the last thirty years in many areas. Twenty-six thematic chapters then examine different aspects of Iron Age archaeology in more depth, from lifeways, economy, and complexity to identity, ritual, and expression. Among the many topics explored are agricultural systems, settlements ranging from villages to cities, landscape monuments, iron smelting and forging, production of textiles, politics, demography, gender, migration, funerary practices, social and religious rituals, coinage, literacy, and art and design. This volume is the only publication currently available that explores all aspects of the European Iron Age in all parts of the continent, along with consideration of regions beyond Europe with which European communities maintained commercial and diplomatic relations.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

'Fancy Objects' in the British Iron Age: Why Decorate?

A survey and new perspectives of Celtic or La Tène art from Britain is presented. Following Spratling (2008:189), Celtic art is defined as ‘ornament or pattern and animal/human/supernatural images in metal and other media’. Regional and temporal variations in the type and usage of decorated artefacts are summarised. Three case studies, made of different media, are presented: metal scabbards, bone and antler weaving combs, and pottery. By asking the question ‘why decorate?’ it is argued that the decision to decorate an artefact can affect its life history, marking it out from undecorated artefacts of the same type. Rather than serving a single function, decoration was employed to serve multiple social goals throughout the Iron Age. Different forms of social expression, such as feasting, elaborate display, or weaving, are significant at any one time or place. It is argued that decorated artefacts often played a significant role in these different social arenas. Contrary to many past discussions, decorated artefacts in media other than metal are demonstrated to have been important in negotiations of social power and cosmology.

Related Papers

Oxford Journal of Archaeology 33(3)

Helen Chittock

Recent years have witnessed the formal acknowledgement of the privileged position from which decorative media in Iron Age Britain have traditionally been studied. Tension remains, however, between the study of the decorated metals that formed the basis for models of Celtic expansion, and decorated non-metals. Despite the general paucity of decoration in Iron Age Britain, decorated non-metals are still not viewed in the same light of social significance as metals. This paper will examine weaving combs from Glastonbury Lake Village, highly decorated objects of antler and bone. By concentrating on the fabrication and display of weaving combs, I aim to highlight the potential significance of the aesthetic effects of these objects.

BAR Publishing

BAR Publishing - British Archaeological Reports (Oxford) Ltd , Helen Chittock

This volume presents a new approach to decorative practices in Iron Age Britain and beyond. It aims to collapse the historic distinction between art and craft during the period 400BC-AD100 by examining the purposeful nature of decoration on varied Iron Age objects, not just those traditionally considered art. A case study from East Yorkshire (UK), a region well known for its elaborate Iron Age metalwork, is presented. This study takes a holistic approach to the finds from a sample of 30 sites, comparing pattern and plainness on objects of a wide range of materials. The analysis focuses on the factors that led makers to decorate certain objects in certain ways and the uses of different patterns in different social contexts. A concentrated study on evidence for use-wear, damage, repair and modification then draws on primary research and uses assemblage theory to better understand the uses and functions of decorated objects and the ways these developed over time.

Benjamin Roberts

The purpose of this paper is to evaluate whether the presence of gold and bronze ornaments in Britain during the centuries c. 1400–1100 cal BC constitutes an ‘ornament horizon’ and to analyse the roles that these objects played in prehistoric communities. To achieve this, a comprehensive ornament database was compiled and the evidence for ornament production, forms, distribution, modes of adornment, and depositional practices was analysed. This revealed the existence of an earlier bronze ornament tradition concentrated in the coastal areas and along the major rivers of southern and eastern England and a later gold ornament tradition throughout Britain. The ornaments were designed to adorn the neck, wrist, and fingers and, with the exception of a quantity of elaborate bronze pins, are not thought to relate to clothing. These were high visibility objects that would have been widely recognised by the networks of communities participating in the intensive movement of objects, people and practices that occurred throughout northwest Europe and beyond. The ornaments were probably worn for worn for substantial periods of an individual’s life before being separated from their wearers. Though the ornaments were circulated, repaired, and probably recycled, there does not appear to have been a substantial delay in their deposition. The excavation of the ornaments in diverse and frequently elaborate arrangements such as in ditches and in settlements, on hills and in rivers, and accompanying cremation burials or other metal objects implies localised reworkings of the more widespread practices of structured deposition.

Duncan Garrow

Alexandra Guglielmi

The Roman material recovered from Ireland is characterised by its overall small quantity and poor quality, a far cry from the lavish sets of bronze and silver vessels recovered beyond the frontiers on the Continent. However, the Discovery Programme’s Late Iron Age and Roman Ireland research project has demonstrated that this material nevertheless has the potential to help us reconstruct the story of late prehistoric Ireland. Building onto these results, the present thesis explores the significance of imported personal ornament in Ireland during the Roman period, within a comparative context encompassing Southern Scandinavia. Discarding previous ethnic labels attached to artefacts such as “Roman” and “Irish/Celtic” objects, this project instead approaches the material in terms of “imports” and “local production”, therefore considering it in the light of the mechanisms by which it reached Ireland and was eventually deposited. As such, other imports such as amber beads and Scottish metalwork are included here. A core part of this project consisted of a thorough reassessment of several categories of artefacts, most notably glass beads, which had until now been understudied at best, neglected at worst. This has allowed a deepening of our understanding of the origins and chronology of these artefact categories, shedding new light on the connections that they embody. At the core of this research lies the concept of entanglement between humans and objects, across time and space. This is reflected in the multifaceted comparative approach adopted throughout. Firstly, the Roman period imports had to be relocated within the longue durée of the Irish Iron Age (700 BC–AD 400) and Early Medieval periods (AD 400–1100). As such, the period encompassed by this study comprises two centuries on either side of the traditional dates for the Late Irish Iron Age (AD 1–400). Furthermore, the pre-Roman period imports of personal ornament to Ireland were carefully examined and compared to the main assemblage under study. Secondly, the Roman period imported jewellery and dress fasteners found in Ireland were considered within the wider picture of Roman material beyond the imperial frontiers. This was undertaken first by a comparative analysis of Roman personal ornament in Southern Scandinavia, and by a general discussion of other parts of non-Roman Europe such as Scotland and Central Europe. Finally, the assemblages of imported personal ornament in Ireland (700 BC–AD 500) and Southern Scandinavia (AD 1–500) were considered against the general background of imports in these two areas. This in-depth comparative analysis has allowed the identification of several trends, some of which deserve further research. Firstly, the perceived dearth of direct imports to Ireland before 100 BC is mainly caused by an almost exclusive focus on metalwork (for which, there are indeed few imports). This project has, however, highlighted a significant assemblage of imported glass jewellery, mainly decorated beads from the Continent, which illustrates early and important links with mainland Europe, links which are a prelude to the rise in imports that we can witness in the early Roman period. As a result of the approach taken for this study, it has been demonstrated that the traditional dates for the Late Irish Iron Age (AD 1–400) do not reflect the surge in imports, especially of personal ornament, in the 1st century BC–1st century AD. Similarly, we witness a second, numerically smaller but nonetheless very significant group of imported dress fasteners dated to the 4th–7th century AD, thus spanning both the end of the Iron Age and beginning of the Early Medieval period. By relocating the Irish record within the wider picture of European events, this project has shown that these two phases of imports correspond to periods of major political upheaval, the first when Western Europe was conquered by Rome, the second when the Roman Empire collapsed and the political structures of Western, Northern and Central Europe were once again shaken, in some cases to their core. Far from remaining “undimmed by the shadow of Rome” (Cunliffe 2001, 417), Iron Age Ireland was entangled with British and Continental political, social, and material lives. Both in Ireland and in Southern Scandinavia, Roman personal ornament was given new meanings and sometimes radically new roles. It was being deposited in burials, used as part of changing religious rites at significant places in the landscape, adopted and appropriated by elites, and sometimes reinterpreted beyond recognition. Overall, it can be said that Roman personal ornament played a significant part in the widespread changes that shaped the societies living in Ireland and Southern Scandinavia in the period 100 BC–AD 500.

In Celtic Art in Europe: Making Connections (eds) C. Gosden, S. Crawford & K. Ulmschneider, 315-324. Oxbow Books, Oxford.

As is amply demonstrated in the Megaw’s extremely useful book Celtic Art, first published in 1989 and reprinted in 2001, designs recognisable as Iron Age or Celtic in character persist in Roman Britain, particularly in the north and the west where flourishing new regional art styles develop. Objects include horse-gear, as well as new varieties of other well-known Iron Age object types such as torcs. Recent surveys reveal that these objects are in fact more numerous than art made before the conquest (Gosden and Hill 2008, 2; Garrow et al. 2009). The influence of Rome can be seen especially in the use of enamels of multiple colours arranged in geometric patterns and brass, a Roman metal. However, although this paper is situated within a wider discourse of Romanisation, it is from the perspective not of how pre-Roman peoples became Roman but rather the role of art in the construction and renegotiation of identity. Building on recent research by Fraser Hunter (2006a; 2006b; 2008a; 2008b; 2010; 2012) and Mary Davis and Adam Gwilt (2008), which highlight regionality and diversity, it is argued that this art is not an historical fossil. Rather, through the making and wearing of these objects, people were actively working out how to live in the Roman world, or on its frontiers.

Matthew Ponting

The Roman material recovered from Ireland is characterised by its overall small quantity and poor quality, a far cry from the lavish sets of bronze and silver vessels recovered beyond the frontiers on the Continent. However, the Discovery Programme’s Late Iron Age and Roman Ireland research project has demonstrated that this material nevertheless has the potential to help us reconstruct the story of late prehistoric Ireland. Building onto these results, the present thesis explores the significance of imported personal ornament in Ireland during the Roman period, within a comparative context encompassing Southern Scandinavia. Discarding previous ethnic labels attached to artefacts such as “Roman” and “Irish/Celtic” objects, this project instead approaches the material in terms of “imports” and “local production”, therefore considering it in the light of the mechanisms by which it reached Ireland and was eventually deposited. As such, other imports such as amber beads and Scottish metalwork are included here. A core part of this project consisted of a thorough reassessment of several categories of artefacts, most notably glass beads, which had until now been understudied at best, neglected at worst. This has allowed a deepening of our understanding of the origins and chronology of these artefact categories, shedding new light on the connections that they embody.

Norwegian Archaeological Review

Visa Immonen

Medieval archaeology as a discipline is usually defined in relation to written sources and history, while other kinds of sources and scholarly traditions studying the same period are overlooked. A small group of 14th-century crescent moon pendants of bronze from Finland as its focal point, the present article analyses the way in which archaeology connects with the visual arts and the discipline specialised in studying them, art history. Instead of some shared methodology, the inquiry proceeds along the tensions between the material and the visual. After the artefact and its technical qualities are examined in the framework of medieval material culture, the object is reduced, firstly, into an iconographical motif, and, secondly, into a represented object. Thirdly, the anthropomorphic features applied on the pendant are extracted and considered against the body of medieval grotesque art. This reveals how the visual is also an effective force in the sphere of material culture and human interaction. In the interdisciplinary work between archaeology and art history, the visual and the material emerge as travelling concepts destabilizing traditional approaches and inspiring new insights. They become entangled in the archaeological research process.

Monstrous Ontologies: Politics, Ethics, Materiality

Emanuele Prezioso

The styles of Celtic art are populated by monstrous artefacts whose forms and decorations are an admixture of animal, human, and vegetal motifs. Because of these material qualities, monstrous artefacts flee from our categorisations, capture our attention, and entrap our senses. They evade from the notion of style that archaeology has created to make sense of the cultures and people who created them. In this paper, I present an analysis of style and argue that it is necessary to take monstrous artefacts seriously. An enterprise that requires to analyse what they do for us, rather than what they represent. That is, observing the requirements that these monstrous artefacts place on artisans in the context of reproducing them. By adopting the Material Engagement Theory (MET), I present a novel definition of style as a continuous creative process: an accumulation of ways of thinking and acting recreated every time an artisan engages with them through required creative gestures and skills. The aim is to explore how artefact are not passive entities but actively constitute our modes of engaging with the world.

49,101 related objects

Adze ; roughout, agricultural tool/implement.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 13, 2023 | Original: January 3, 2018

The Iron Age was a period in human history that started between 1200 B.C. and 600 B.C., depending on the region, and followed the Stone Age and Bronze Age. During the Iron Age, people across much of Europe, Asia and parts of Africa began making tools and weapons from iron and steel. For some societies, including Ancient Greece, the start of the Iron Age was accompanied by a period of cultural decline.

Humans may have smelted iron sporadically throughout the Bronze Age , though they likely saw iron as an inferior metal. Iron tools and weapons weren’t as hard or durable as their bronze counterparts.

The use of iron became more widespread after people learned how to make steel, a much harder metal, by heating iron with carbon. The Hittites—who lived during the Bronze Age in what is now Turkey—may have been the first to make steel.

When Was the Iron Age?

The Iron Age began around 1200 B.C. in the Mediterranean region and Near East with the collapse of several prominent Bronze Age civilizations, including the Mycenaean civilization in Greece and the Hittite Empire in Turkey. Ancient cities including Troy and Gaza were destroyed, trade routes were lost and literacy declined throughout the region.

The cause for the collapse of these Bronze Age kingdoms remains unclear. Archaeological evidence suggests a succession of severe droughts in the eastern Mediterranean region over a 150-year period from 1250 to 1100 B.C. likely figured prominently in the collapse. Earthquakes, famine, sociopolitical unrest and invasion by nomadic tribes may also have played a role.

Some experts believe that a disruption in trade routes may have caused shortages of the copper or tin used to make bronze around this time. Metal smiths, as a result, may have turned to iron as an alternative.

Many scholars place the end of the Iron Age in at around 550 B.C., when Herodotus , “The Father of History,” began writing “The Histories,” though the end date varies by region. In Scandinavia, it ended closer to A.D. 800 with the rise of the Vikings . In Western and Central Europe, the end of the Iron Age is typically identified as coinciding with the Roman conquest during the first century BC.

Greek Dark Ages

Greece had become a major hub of activity and culture on the Mediterranean during the late Bronze Age. The Mycenaean civilization was rich in material wealth from trade. Mycenaeans built large palaces and a society with strict class hierarchy.

But around 1200 B.C. Mycenaean Greece collapsed. Greece entered a period of turmoil sometimes called the Greek Dark Ages.

Archaeologists believe there may have been a period of famine in which Greece’s population dropped dramatically during this time. Major cities (with the exception of Athens) were abandoned. As urban societies splintered, people moved toward smaller, more pastoral groups focused on raising livestock.

Mycenaean Greece had been a literate society, but the Greeks of the early Iron Age left no written record, leading some scholars to believe they were illiterate. Few artifacts or ruins remain from the period, which lasted roughly 300 years.

By the late Iron Age, the Greek economy had recovered and Greece had entered its “classical” period. Classical Greece was an era of cultural achievements including the Parthenon , Greek drama and philosophers including Socrates .

The classical period also brought political reform and introduced the world to a new system of government known as demokratia , or “rule by the people.”

Persian Empire

During the Iron Age in the Near East, nomadic pastoralists who raised sheep, goats and cattle on the Iranian plateau began to develop a state that would become known as Persia.

The Persians established their empire at a time after humans had learned to make steel. Steel weapons were sharper and stronger than earlier bronze or stone weapons.

The ancient Persians also fought on horseback. They may have been the first civilization to develop an armored cavalry in which horses and riders were completely covered in steel armor.

The First Persian Empire , founded by Cyrus the Great around 550 B.C., became one of the largest empires in history, stretching from the Balkans of Eastern Europe to the Indus Valley in India.

Iron Age In Europe

Life in Iron Age Europe was primarily rural and agricultural. Iron tools made farming easier.

Celts lived across most of Europe during the Iron Age. The Celts were a collection of tribes with origins in central Europe. They lived in small communities or clans and shared a similar language, religious beliefs, traditions and culture. It’s believed that Celtic culture started to evolve as early as 1200 B.C.

The Celts migrated throughout Western Europe—including Britain, Ireland, France and Spain. Their legacy remains prominent in Ireland and Great Britain, where traces of their language and culture are still prominent today.

Iron Age Hill Forts

People throughout much of Celtic Europe lived in hill forts during the Iron Age. Walls and ditches surrounded the forts, and warriors defended hill forts against attacks by rival clans.

Inside the hill forts, families lived in simple, round houses made of mud and wood with thatched roofs. They grew crops and kept livestock, including goats, sheep, pigs, cows and geese.

Hundreds of bog bodies dating back to the Iron Age have been discovered across Northern Europe. Bog bodies are corpses that have been naturally mummified or preserved in peat bogs.

Examples of Iron Age bog bodies include the Tollund Man, found in Denmark, and the Gallagh Man from Ireland.

The mysterious bog bodies appear to have at least one thing in common: They died brutal deaths. For instance, Lindow Man, found near Manchester, England, appears to have been hit over the head, had his throat slit and was whipped with a rope made of animal sinew before being thrown into the watery bog.

The Celtic tribes had no written language at the time, so they left no record of why these people were killed and thrown in bogs. Some experts believe the bog bodies may have been ritually killed for religious reasons.

Other Iron Age artifacts including swords, cups, and shields have also been found buried in peat bogs. These too may have served as offerings to pagan gods in religious ceremonies led by Druid priests.

HISTORY Vault: Ancient History

From the Sphinx of Egypt to the Kama Sutra, explore ancient history videos.

Greek Dark Age; Ancient History Encyclopedia. Overview; Iron Age, 800 BC - AD 43; BBC . Bog Bodies of the Iron Age; PBS .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Pre Christian - Iron Age

Videos from the community ( 0 ).

Why not start the community off by adding a post or uploading a resource?

Notes from the community ( 0 )

Websites from the community ( 0 ).

Art History Leaving Cert

I am an Artist and Art Teacher. I am building this website to help students prepare for the Leaving Cert Art History Exam.

Please use the menu at the top of the page to navigate this website.

This site is under construction. I would appreciate feedback or queries from viewers using the contact form below.

As the exam in looming, and because I feel that Giotto is always a winner, I have added some of my very old Giotto notes (pre – internet) below to download GIOTTO scans

Written by Deirdre Morgan. Updated 29th May 2021.

Share this:

Art history by deirdre morgan.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

- Shang and Zhou Dynasties: The Bronze Age of China

Wine pouring vessel (Gong)

Water Buffalo

Handle-shaped blade

Wine container (Hu)

Wine container (hu)

Bell (niuzhong)

Knotted dragon pendant

Food serving vessel (dui)

Department of Asian Art , The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2004