- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Black Death

By: History.com Editors

Updated: March 28, 2023 | Original: September 17, 2010

The Black Death was a devastating global epidemic of bubonic plague that struck Europe and Asia in the mid-1300s. The plague arrived in Europe in October 1347, when 12 ships from the Black Sea docked at the Sicilian port of Messina. People gathered on the docks were met with a horrifying surprise: Most sailors aboard the ships were dead, and those still alive were gravely ill and covered in black boils that oozed blood and pus. Sicilian authorities hastily ordered the fleet of “death ships” out of the harbor, but it was too late: Over the next five years, the Black Death would kill more than 20 million people in Europe—almost one-third of the continent’s population.

How Did the Black Plague Start?

Even before the “death ships” pulled into port at Messina, many Europeans had heard rumors about a “Great Pestilence” that was carving a deadly path across the trade routes of the Near and Far East. Indeed, in the early 1340s, the disease had struck China, India, Persia, Syria and Egypt.

The plague is thought to have originated in Asia over 2,000 years ago and was likely spread by trading ships , though recent research has indicated the pathogen responsible for the Black Death may have existed in Europe as early as 3000 B.C.

Symptoms of the Black Plague

Europeans were scarcely equipped for the horrible reality of the Black Death. “In men and women alike,” the Italian poet Giovanni Boccaccio wrote, “at the beginning of the malady, certain swellings, either on the groin or under the armpits…waxed to the bigness of a common apple, others to the size of an egg, some more and some less, and these the vulgar named plague-boils.”

Blood and pus seeped out of these strange swellings, which were followed by a host of other unpleasant symptoms—fever, chills, vomiting, diarrhea, terrible aches and pains—and then, in short order, death.

The Bubonic Plague attacks the lymphatic system, causing swelling in the lymph nodes. If untreated, the infection can spread to the blood or lungs.

How Did the Black Death Spread?

The Black Death was terrifyingly, indiscriminately contagious: “the mere touching of the clothes,” wrote Boccaccio, “appeared to itself to communicate the malady to the toucher.” The disease was also terrifyingly efficient. People who were perfectly healthy when they went to bed at night could be dead by morning.

Did you know? Many scholars think that the nursery rhyme “Ring around the Rosy” was written about the symptoms of the Black Death.

Understanding the Black Death

Today, scientists understand that the Black Death, now known as the plague, is spread by a bacillus called Yersinia pestis . (The French biologist Alexandre Yersin discovered this germ at the end of the 19th century.)

They know that the bacillus travels from person to person through the air , as well as through the bite of infected fleas and rats. Both of these pests could be found almost everywhere in medieval Europe, but they were particularly at home aboard ships of all kinds—which is how the deadly plague made its way through one European port city after another.

Not long after it struck Messina, the Black Death spread to the port of Marseilles in France and the port of Tunis in North Africa. Then it reached Rome and Florence, two cities at the center of an elaborate web of trade routes. By the middle of 1348, the Black Death had struck Paris, Bordeaux, Lyon and London.

Today, this grim sequence of events is terrifying but comprehensible. In the middle of the 14th century, however, there seemed to be no rational explanation for it.

No one knew exactly how the Black Death was transmitted from one patient to another, and no one knew how to prevent or treat it. According to one doctor, for example, “instantaneous death occurs when the aerial spirit escaping from the eyes of the sick man strikes the healthy person standing near and looking at the sick.”

How Do You Treat the Black Death?

Physicians relied on crude and unsophisticated techniques such as bloodletting and boil-lancing (practices that were dangerous as well as unsanitary) and superstitious practices such as burning aromatic herbs and bathing in rosewater or vinegar.

Meanwhile, in a panic, healthy people did all they could to avoid the sick. Doctors refused to see patients; priests refused to administer last rites; and shopkeepers closed their stores. Many people fled the cities for the countryside, but even there they could not escape the disease: It affected cows, sheep, goats, pigs and chickens as well as people.

In fact, so many sheep died that one of the consequences of the Black Death was a European wool shortage. And many people, desperate to save themselves, even abandoned their sick and dying loved ones. “Thus doing,” Boccaccio wrote, “each thought to secure immunity for himself.”

Black Plague: God’s Punishment?

Because they did not understand the biology of the disease, many people believed that the Black Death was a kind of divine punishment—retribution for sins against God such as greed, blasphemy, heresy, fornication and worldliness.

By this logic, the only way to overcome the plague was to win God’s forgiveness. Some people believed that the way to do this was to purge their communities of heretics and other troublemakers—so, for example, many thousands of Jews were massacred in 1348 and 1349. (Thousands more fled to the sparsely populated regions of Eastern Europe, where they could be relatively safe from the rampaging mobs in the cities.)

Some people coped with the terror and uncertainty of the Black Death epidemic by lashing out at their neighbors; others coped by turning inward and fretting about the condition of their own souls.

Flagellants

Some upper-class men joined processions of flagellants that traveled from town to town and engaged in public displays of penance and punishment: They would beat themselves and one another with heavy leather straps studded with sharp pieces of metal while the townspeople looked on. For 33 1/2 days, the flagellants repeated this ritual three times a day. Then they would move on to the next town and begin the process over again.

Though the flagellant movement did provide some comfort to people who felt powerless in the face of inexplicable tragedy, it soon began to worry the Pope, whose authority the flagellants had begun to usurp. In the face of this papal resistance, the movement disintegrated.

How Did the Black Death End?

The plague never really ended and it returned with a vengeance years later. But officials in the port city of Ragusa were able to slow its spread by keeping arriving sailors in isolation until it was clear they were not carrying the disease—creating social distancing that relied on isolation to slow the spread of the disease.

The sailors were initially held on their ships for 30 days (a trentino ), a period that was later increased to 40 days, or a quarantine — the origin of the term “quarantine” and a practice still used today.

Does the Black Plague Still Exist?

The Black Death epidemic had run its course by the early 1350s, but the plague reappeared every few generations for centuries. Modern sanitation and public-health practices have greatly mitigated the impact of the disease but have not eliminated it. While antibiotics are available to treat the Black Death, according to The World Health Organization, there are still 1,000 to 3,000 cases of plague every year.

Gallery: Pandemics That Changed History

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Let your curiosity lead the way:

Apply Today

- Arts & Sciences

- Graduate Studies in A&S

How the Black Death made life better

Christine R. Johnson is associate professor of history in the Department of History.

“[The] mortality destroyed more than a third of the men, women, and children … such a shortage of workers ensued that the humble turned up their noses at employment, and could scarcely be persuaded to serve the eminent unless for triple wages. … As a result, churchmen, knights and other worthies have been forced to thresh their corn, plough the land and perform every other unskilled task if they are to make their own bread.”

— account of the black death in the cathedral priory chronicle at rochester (written no later than 1350).

In its entry on the Black Death, the 1347–50 outbreak of bubonic plague that killed at least a third of Europe’s population, this chronicle from the English city of Rochester includes among its harrowing details a seemingly trivial lament: Aristocrats and high clergymen not only had to pay triple wages to those toiling in their fields, but, even worse, they themselves had to perform manual labor. Curiously, the documentary record, which provides ample evidence that workers did demand and receive higher wages (on which more below), contains in contrast scant evidence that “worthies” ever dirtied their hands with fieldwork. Even if (or especially as) phantasms, however, these sickle-wielding lords reveal the importance of imagined possibilities in shaping pandemic responses.

The eminent refused to take on menial roles, not because they could not perform these “unskilled” tasks, but because to do so would be unworthy of their social rank, and it was unthinkable to abandon that social and labor hierarchy. Farm work was peasant work, whether performed by serfs bound to a particular manor, tenant farmers or wage laborers hired by the year or the season. But the staggering mortality of the Black Death reduced this previously sufficient peasant population sharply enough to create a severe labor shortage.

What happened next has been the subject of an enormous amount of scholarship, particularly in the case of England, where the large extant body of sources such as chronicles, legislation, court cases and manorial account books provides rich material for studying the social and economic changes in the wake of the Black Death. Scholars disagree about how and how much things changed, but they share a tendency to describe these changes in oddly passive terms: wages rose, inequality decreased, feudalism ended.

Yet there was a great deal of deliberate (in)action behind these developments. Rather than supply some of the needed labor themselves, landowners turned to solutions that might produce the kind of world they were capable of imagining. In England they created first the Ordinance (1349) and then the Statute (1351) of Labourers, which froze wages at pre-plague levels, compelled workers not otherwise engaged in fixed, long-term employment into year-long contracts with the first employer who demanded it, and established penalties to ensure compliance. As Jane Whittle has noted, in putting their efforts behind the control of waged labor rather than the retrenchment of (already declining) serfdom, rural landowners sought a “thinkable” resolution to this impasse: They would use the existing market for labor, but control the terms of exchange.

Many peasants, however, refused to play their assigned role of deferential wage earner. Court records from 1352, for example, show that “Edward le Taillour of Wootton, employee of the prior and convent of Bradenstoke … left his employment before the feast of St Nicholas [6 December] without permission or reasonable cause, contrary to statute,” and that John Death of Wroughton demanded an “excess” of six shillings eightpence for reaping John Lovel’s corn. Recalcitrant laborers remained a problem in 1374, when “John Fisshere, William Theker, William Furnes, John Dyker, Gilbert Chyld, Alan Tasker, Stephen Lang, John Hardlad, Cecilia Ka, Joan daughter of Henry Couper, Matillis de Ely, Alice wife of Simon Souter, all of Bardney, labourers, refused to work [for the Abbot of Bardney at the stipulated wages], and on the same day they left the town to get higher wages elsewhere, in contempt of the king and contrary to statute.”

With many state governments reducing unemployment benefits to push workers to fill open jobs, the aim, like England after the Black Death, is to reinstate and reinforce previous social and labor hierarchies, regardless of whose work has actually been “essential” over the past 16 months.

These records attest to some individuals’ appreciation of the increased value of their labor in the new marketplace created by mass death. The number and geographical range of these individual acts of defiance, moreover, suggest a vibrant, if unrecorded, current of communal discussions, rumors and calculations that supported such individual agency. In the face of official intransigence, workers pushed for higher wages and greater mobility, which they received because “churchmen, knights, and other worthies” were willing to make these concessions, rather than have to work the fields and herd the sheep themselves. As a result, wages rose, inequality lessened … and the social and labor hierarchies remained the same.

Thankfully, the current COVID-19 pandemic is vastly less lethal than the mid 14th-century bubonic plague, and we can hope that people around the world do not experience the loss of human life on the same scale. What the Black Death does share with our present moment is the issue of labor and the limits drawn by the negative space of the unthinkable.

The people who prospered under the pre-pandemic system are now deciding what “back to normal” looks like and how we get there. With many state governments reducing unemployment benefits to push workers to fill open jobs, the aim, like England after the Black Death, is to reinstate and reinforce previous social and labor hierarchies, regardless of whose work has actually been “essential” over the past 16 months. Workers in specific circumstances and with individual or collective determination might negotiate better labor conditions or higher wages, but these concessions’ permanance remains in the hands of employers who saw no reason to implement them prior to the pandemic. As historians Ada Palmer and Eleanor Janega have argued, whatever gains peasants and artisans obtained in the decades after the Black Death did not survive the following centuries. Elites successfully reclaimed a greater share of wealth and income, hierarchies ossified, and laborers’ power diminished.

Simply stating that English society was changed by the Black Death not only discounts the people who did the changing, but also ignores the insufficiencies of the changes they produced. The Rochester chronicler raised the specter of knights and churchmen toiling in the fields to evoke the unthinkable scale of the disaster, and then refused to contemplate this radically different social order any further. We are not the Rochester chronicler. How can we think the unthinkable — about safety and health, racial justice, gender roles, immigration status, access to childcare, and the dignity, autonomy and worth of labor — for our own post-pandemic future?

All quoted material from Rosemary Horrox, ed., The Black Death (Manchester University Press, 1994).

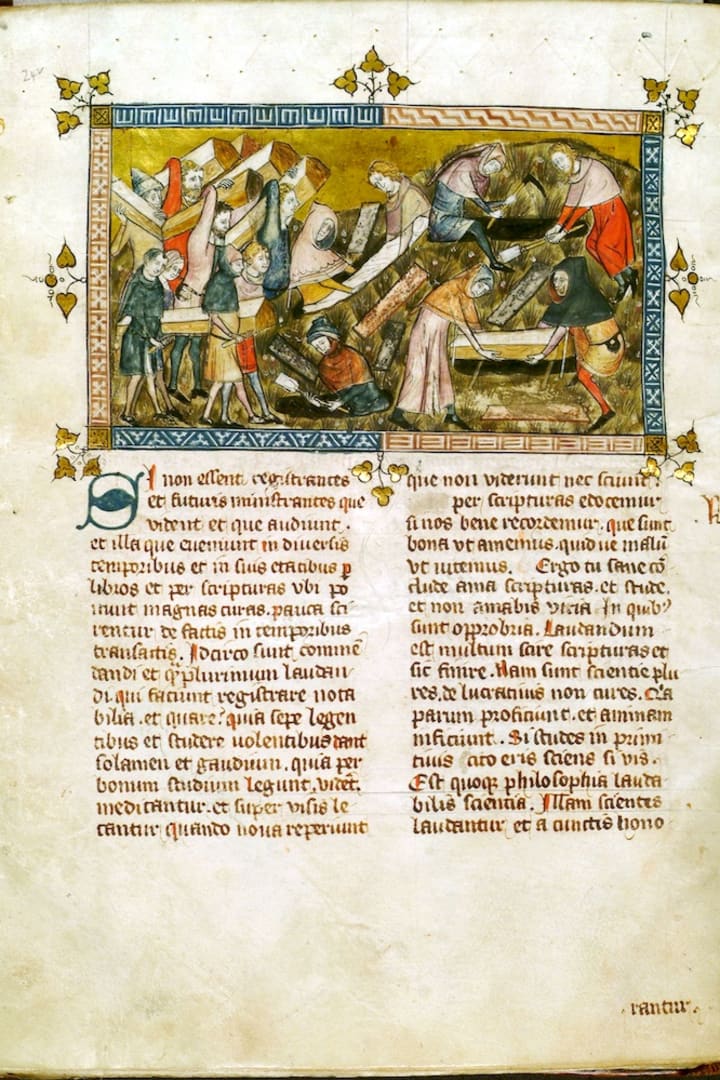

Headline image: Medieval illustration of men harvesting wheat with reaping-hooks, on a calendar page for August, circa 1310. Queen Mary's Psalter (Ms. Royal 2. B. VII), fol. 78v, The British Library.

in the news:

Q&A with writer Amitava Kumar

What a cube, a drop and a wave taught me about creativity, communication and community

Origins and empires: Reading coins for rulers’ stories

Workshop taught students to calm climate anxiety with community action

Impact of the Black Death Essay

Introduction, social impacts of the black death, economic impacts of the black death, political impacts of the black death, reference list.

The Black Death was, no doubt, the greatest population disaster that has ever occurred in the history of Europe. The name is given to the bubonic plaque that occurred in the fourteenth century in Europe killing millions of people. The plaque began in the year 1348, and by the year 1359, it had killed an approximate 1.5 million people, out of an estimated total population of about 4 million people.

So terrifying was the Black Death that peasants were blaming themselves for its occurrence, and thus some of them resulted to punishing themselves as a way of seeking God’s forgiveness. The bubonic plaque was caused by fleas that were hosted by rats, a common phenomenon in the cities and towns. The presence of rats in the cities and towns was due to the fact that the towns were littered, and they were poorly managed.

The worst part of it is the fact that the medieval peasants did not know that the plaque was caused by the pleas hosted by the rats. They actually believed that the plague was caused by the rats themselves. As more and more people died from the Black Death, the impacts of the plague became more profound.

The plague affected the demographic composition of the society, and thus it had far-reaching effects on the social, economic, political and even cultural realms of the medieval society. To this day, the Black Death is remembered as the worst demographic disaster to be ever experienced in European history (Robin, 2011). This paper is an in-depth analysis of the impacts of the Black Death.

The Black Death had far reaching social impacts on the people who lived during the fourteenth century. An obvious social impact of the plague is the fact that the Black Death led to a significant reduction in the human population of the affected areas. This had extensive effects on all aspects of life, including the social and political structure of the affected areas.

Before the plague, feudalism, the European social structure in medieval times, had created a society in which inequality was rife, with many poor peasants, and rich lords. This fuelled overpopulation, which was a catalyst for the mortality of the plaque. After the plaque, a large number of the overpopulated peasants became victims of the plaque, and thus the lords lacked labourers in their farms. This also led to a significant reduction in the population (Bryrne, 2011).

The people who were spared by the plague lived full lives. They regarded themselves as the next victims of the bubonic plague. This led to immoral behaviour that saw societal codes like the sexual codes broken. People did not care about having virtues anymore because they knew that death was approaching fast. As people lost their partners to the plague, the marriage market grew, fuelling more sexual immorality (Carol, 1996).

Also among the immediate social impacts is the fact that at one point, the number of people who were dying from the bubonic plague was seemingly more than the number of the living. This made it virtually impossible for the living to take care of the ailing, or even for the living to bury the deceased. This was a social crisis that has remained in the books of history as a remarkable impact of the bubonic plague.

Immediately after the occurrence of the Black Death, all economic activities were paralysed. The first economic activity to suffer substantially from the plaque was trade. Although people were not aware that it was the infectiousness of the plaque that was making it to kill more people, they were afraid to travel to plagued areas for fear of coming into contact with rats, which they believed was the source of the disease. This substantially affected trade ties between villages and communities in the medieval European society.

After the occurrence of the Black Death, other impacts of the plague started affecting the community. The population of the European parts affected by the plaque reduced drastically, leading to a severe shortage of labour for the farms. The demand of peasant farmers increased, with the lords competing for them by relocating them from their villages to the farms of the latter. This made the peasants have a competitive economic edge, as they were able to negotiate for better salaries.

As the Black Death claimed more lives, farms were left unattended because the peasants who were responsible for ploughing had fallen victims of the plague. Where the lords were lucky to have had some harvest, it was challenging to bring it home due to a serious shortage of manpower.

Some harvest got destroyed in the field as there were no men to bring it home. Some animals got lost because the people who used to look after them had also fallen victims of the plague. These problems led to a number of other impacts in the medieval society of the fourteenth century (Bridbury, 1973).

As farms went unploughed and some harvest remained in the fields, people in the villages starved for food. Cities and towns also faced severe shortages of food since the farming villages around the towns did not have sufficient foodstuffs. Lords had to strategize economically in order to survive, and thus most of them resulted to keeping sheep since it was easier without the manpower.

Economic activities that required the presence of large numbers of peasants like the farming of grains lost their popularity. This, in turn, led to serious shortage of basic commodities like bread. This, coupled with the fact that the production of all kinds of foodstuffs had decreases, led to inflationary prices on commodities (“The Black Death And Its Effects”, 1935). The poor were left thriving in an environment full of hardships as the prices of foods skyrocketed.

The Black Death had a number of political impacts. First of all, the feudal social system of the fourteen-century European population demanded that peasants could not relocate from their villages at will. For a peasant to relocate from his/her village, he/she had to seek the permission of his/her lord.

After the Black Death, it became increasingly difficult for lords to get the number of peasants they required to provide them with the labour for their farms. This made lords to disregard the law, and relocate peasants to their villages so that they could work in their farms. Most of the times, the lords even declined to return the latter to their rightful villages in a bid to get maximum benefit from their labour.

Another political impact of the Black Death also stems from the reduced population of the affected areas. This is because after the number of peasants reduced, and they were able to negotiate salaries and even relocate from their villages, contrary to feudal law, the government imposed stricter rules to regulate the way peasants offer their manpower to the lords.

This was done by the introduction of the 1351 “statute for labourers” (Bridbury, 1973). The statute provided that payments to peasants were to be made with reference to the payments that were made in 1346. This meant that peasants would receive payments using the terms that were prevailing before the plague occurred.

The statute was structures such that both the lord and the peasant could be accused of breaking the law by either the peasant receiving a higher payment, or the lord giving the same. The effect of this statute was that a good number of peasants disobeyed it, leading to, arguably inhumane punishment. This fuelled revolt among the peasants who sought to fight for their rights in the 1381 Peasants Revolt (Bentley et al., 2008).

After oppressive statutes like the statute for labourers came into force, peasants started to be resistant. They therefore organized a number of revolts in a bid to attract the attention of legislators to their plea of fairness. The most serious of these revolts was the aforementioned 1381 peasant revolt. The peasants had gathered in huge numbers and marched to London. They killed senior officials of the King and took control over the tower of London.

Among their main grievances was the fact that, thirty-five years after the occurrence of the Black Death, the population had reasonably grown and the pre-existent demand for labour had substantially reduced. The lords were therefore threatening to withdraw the privileges they had given to peasants since their demand was no more. This led to the revolt as the peasants sought to fight for their privileges.

From the discussion above, it is evident that the Black Death had a lot of impacts on the European medieval society. It changed the demographic set-up of the community and thus it substantially affected the social activities of the peasants. This can be evidenced by the aforementioned increase in cases of sexual immorality as people had lost their partners in the plague.

The Black Death also had a number of economic impacts which resulted from the drastic decrease in the population of peasants. This can be evidenced by the aforementioned change by lords from grain farming to sheep farming. Lastly, the Black Death had a number of political impacts which can be exemplified by the development of the aforementioned statute for labourers.

Studies of the impacts of the bubonic plague are still ongoing. This is despite the fact that most of the impacts were realized immediately after the plague and their effects on the society analyzed. Political activists during the time, who were mostly lords, had observed the effects of the plague and made societal changes that were bound to benefit them.

However, scientists still believe that the European society still suffers significant effects of the bubonic plague. For instance, it has been established that England, where the greatest effects of the bubonic plague were perhaps felt, has significantly lower genetic diversity than it is suspected to have had in the eleventh century. Geneticists explain this by the argument that the deaths that resulted from the Black Deaths were the cause of the low genetic variation in Europe.

Bentley, Jerry H., Ziegler, Herbert F., Streets, Heather E. (2008) Traditions and

Encounters: A Brief Global History, ch9,15,19, McGraw-Hill, Inc.

Bridbury, A. (1973). The Black Death. The Economic History Review, 26: 577 – 592.

Bryrne, J. (2011). Black Death. World Book Advanced. Web.

Carol, B. (1996). Bubonic Plague in the nineteenth-century China.

Robin, N. (2011). Apocalypse Then: A History of Plague. Special Report. World Book Advanced. Web.

The Black Death And Its Effects. (1935). Readings in English History Drawn from the Original Sources: Intended to Illustrate a Short History of England. Boston: Ginn.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, October 29). Impact of the Black Death. https://ivypanda.com/essays/impact-of-the-black-death/

"Impact of the Black Death." IvyPanda , 29 Oct. 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/impact-of-the-black-death/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'Impact of the Black Death'. 29 October.

IvyPanda . 2019. "Impact of the Black Death." October 29, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/impact-of-the-black-death/.

1. IvyPanda . "Impact of the Black Death." October 29, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/impact-of-the-black-death/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Impact of the Black Death." October 29, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/impact-of-the-black-death/.

- The Bubonic Plague Symptoms and Historical Impacts

- Bubonic Plague: Symptoms, Treatment, and Prevention

- Bubonic Plague and AIDS: Differences and Similarities

- The History of Spread of Bubonic Plague

- Bubonic Plague Effects on Society and Culture

- Early Modern Europe After the Black Death

- The Demographics Impact of Black Death and the Standard of Living Controversies in the Late Medieval

- The Black Death in Europe: Spread and Causes

- Stress and Strains in the Renaissance Society

- The Black Death Disease' History

- What Factors Contributed to the Dissolution of the Roman Empire?

- Chivalry in the First Crusade

- The Knights Templar: The Warrior Monks

- The Catholic Church and the Black Death in the 14th Century

- The Year 1000’ by Robert Lacey and Danny Danziger

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University website

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

The Black Death and its Aftermath

- John Brooke

The Black Death was the second pandemic of bubonic plague and the most devastating pandemic in world history. It was a descendant of the ancient plague that had afflicted Rome, from 541 to 549 CE, during the time of emperor Justinian. The bubonic plague, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis , persisted for centuries in wild rodent colonies in Central Asia and, somewhere in the early 1300s, mutated into a form much more virulent to humans.

At about the same time, it began to spread globally. It moved from Central Asia to China in the early 1200s and reached the Black Sea in the late 1340s. Hitting the Middle East and Europe between 1347 and 1351, the Black Death had aftershocks still felt into the early 1700s. When it was over, the European population was cut by a third to a half, and China and India suffered death on a similar scale.

Traditionally, historians have argued that the transmission of the plague involved movement of plague-infected fleas from wild rodents to the household black rat. However, evidence now suggests that it must have been transmitted first by direct human contact with rodents and then via human fleas and head lice. This new explanation better explains the bacteria’s very rapid movement along trade routes throughout Eurasia and into sub-Saharan Africa.

At the time, people thought that the plague came into Mediterranean ports by ship. But, it is also becoming clear that small pools of plague had been established in Europe for centuries, apparently in wild rodent communities in the high passes of the Alps.

The remains of Bubonic plague victims in Martigues, France.

We know a lot about the impact of the Black Death from both the documentary record and from archaeological excavations. Within the last few decades, the genetic signature of the plague has been positively identified in burials across Europe.

The bacillus was deadly and took both rich and poor, rural and urban: the daughter of King Edward III of England died of the plague in the summer of 1348. But quickly—at least in Europe—the rich learned to barricade their households against its reach, and the poor suffered disproportionately.

Strikingly, if a mother survived the plague, her children tended to survive; if she died, they died with her. In the late 1340s, news of the plague spread and people knew it was coming: plague pits recently discovered in London were dug before the arrival of the epidemic.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder's 1562 painting "The Triumph of Death" depicts the turmoil Europe experienced as a result of the plague.

The Black Death pandemic was a profound rupture that reshaped the economy, society and culture in Europe. Most immediately, the Black Death drove an intensification of Christian religious belief and practice, manifested in portents of the apocalypse, in extremist cults that challenged the authority of the clergy, and in Christian pogroms against Europe’s Jews.

This intensified religiosity had long-range institutional impacts. Combined with the death of many clergy, fears of sending students on long, dangerous journeys, and the fortuitous appearance of rich bequests, the heightened religiosity inspired the founding of new universities and new colleges at older ones.

The proliferation of new centers of learning and debate subtly undermined the unity of Medieval Christianity. It also set the stage for the rise of stronger national identities and ultimately for the Reformation that split Christianity in the 16 th century.

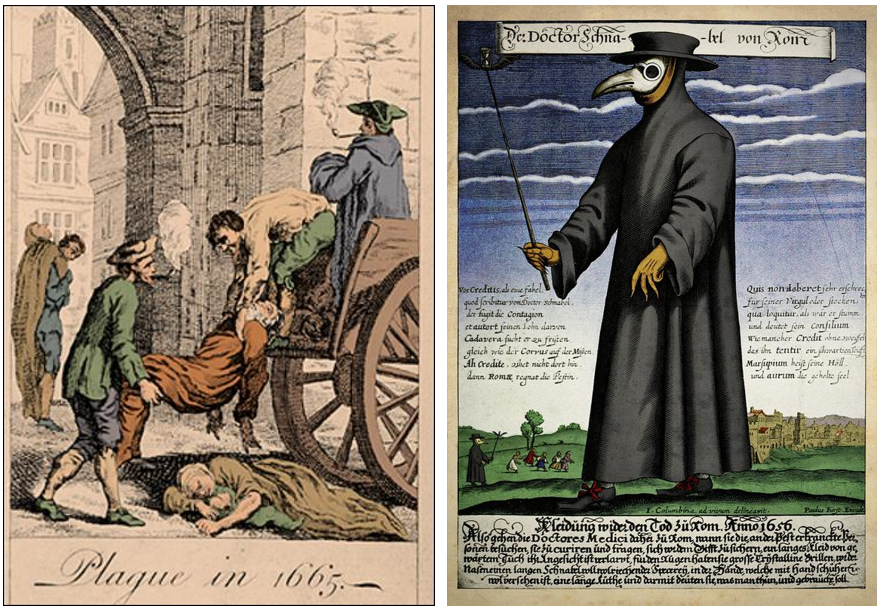

Depiction of the Great Plague of London in 1665 (left) . A copper engraving of a seventeenth-century plague doctor (right) .

The disruption caused by the plague also shaped new directions in medical knowledge. Doctors tending the sick during the plague learned from their direct experience and began to rebel against ancient medical doctrine. The Black Death made clear that disease was not caused by an alignment of the stars but from a contagion. Doctors became committed to a new empirical approach to medicine and the treatment of disease. Here, then, lie the distant roots of the Scientific Revolution.

Quarantines were directly connected to this new empiricism, and the almost instinctive social distancing of Europe’s middling and elite households. The first quarantine was established in 1377 at the Adriatic port of Ragussa. By the 1460s quarantines were routine in the European Mediterranean.

Major outbreaks of plague in 1665 and 1721 in London and Marseille were the result of breakdowns in this quarantine barrier. From the late 17th century to 1871 the Habsburg Empire maintained an armed “cordon sanitaire” against plague eruptions from the Ottoman Empire.

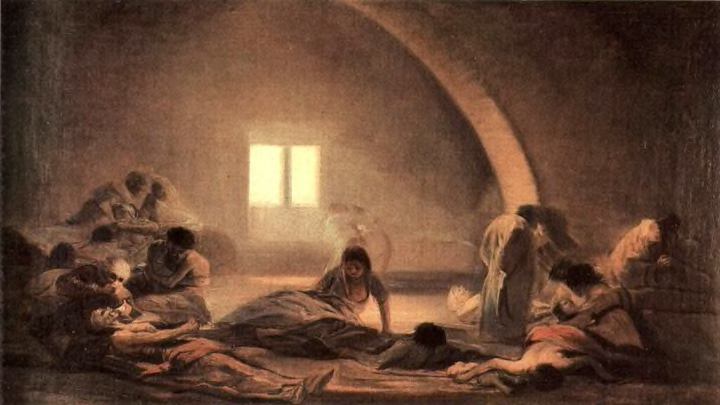

Michel Serre's painting depicting the 1721 plague outbreak in Marseille.

As with the rise of national universities, the building of quarantine structures against the plague was a dimension in the emergence of state power in Europe.

Through all of this turmoil and trauma, the common people who survived the Black Death emerged to new opportunities in emptied lands. We have reasonably good wage data for England, and wage rates rose dramatically and rapidly, as masters and landlords were willing to pay more for increasingly scarce labor.

The famous French historian Marc Bloch argued that medieval society began to break down at this time because the guaranteed flow of income from the labor of the poor into noble households ended with the depopulation of the plague. The rising autonomy of the poor contributed both to peasant uprisings and to late medieval Europe’s thinly disguised resource wars, as nobles and their men at arms attempted to replace rent with plunder.

A depiction of the 1381 Peasant's Revolt in England.

At the same time, the ravages of the Black Death decimated the ancient trade routes bringing spices and fine textiles from the East, ending what is known as the Medieval World System, running between China, India, and the Mediterranean.

By the 1460s, the Portuguese—elbowed out of the European resource wars—began a search for new ways to the East, making their way south along the African coast, launching an economic globalization that after 1492 included the Americas.

And we should remember that this first globalization would lead directly to another great series of pandemics, not the plague but chickenpox, measles, and smallpox, which in the centuries following Columbus’s landing would kill the great majority of the native peoples of the Americas.

In these ways we still live in a world shaped by the Black Death.

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Europe 1300 - 1800

Course: europe 1300 - 1800 > unit 2.

- Remaking a fourteenth-century triptych

- Introduction to Late Gothic art

The Black Death

- Gold-ground panel painting

- The Medieval and Renaissance Altarpiece

The plague hit hard and fast. People lay ill little more than two or three days and died suddenly….He who was well one day was dead the next and being carried to his grave,” writes the Carmelite friar Jean de Venette in his 14th century French chronicle. From his native Picardy, Jean witnessed the disease’s impact in northern France; Normandy, for example, lost 70 to 80 percent of its population. Italy was equally devastated. The Florentine author Boccaccio recounts how that city’s citizens “dug for each graveyard a huge trench, in which they laid the corpses as they arrived by hundreds at a time, piling them up tier upon tier as merchandise is stowed on a ship.

Trade was to Blame

"god is deaf nowadays and will not hear us", economic impact, did the black death contribute to the renaissance, want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

A newer edition of this book is available.

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

3 (page 35) p. 35 Big impacts: the Black Death

- Published: March 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

‘Big impacts: the Black Death’ explains how the contention that major epidemic disasters changed the course of historical events — the ‘Great Disaster’ interpretations of history — leaves too much out of the account. Focusing on the second pandemic in Europe, and on the Black Death which initiated it, it describes the effect of the disease on human behaviour and explains how it might well appear to have reshaped the course of European history. However, it does not seem to have been plague alone which determined population trends in the fifteenth century. It is impossible to attribute everything to plague in explaining long-term and large-scale economic and social change.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

This website uses cookies.

By clicking the "Accept" button or continuing to browse our site, you agree to first-party and session-only cookies being stored on your device to enhance site navigation and analyze site performance and traffic. For more information on our use of cookies, please see our Privacy Policy .

- Journal of Economic Literature

The Economic Impact of the Black Death

- Remi Jedwab

- Noel D. Johnson

- Mark Koyama

- Article Information

Additional Materials

- Replication Package

- Author Disclosure Statement(s) (189.26 KB)

JEL Classification

- N43 Economic History: Government, War, Law, International Relations, and Regulation: Europe: Pre-1913

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

History of the Plague: An Ancient Pandemic for the Age of COVID-19

During the fourteenth century, the bubonic plague or Black Death killed more than one third of Europe or 25 million people. Those afflicted died quickly and horribly from an unseen menace, spiking high fevers with suppurative buboes (swellings). Its causative agent is Yersinia pestis , creating recurrent plague cycles from the Bronze Age into modern-day California and Mongolia. Plague remains endemic in Madagascar, Congo, and Peru. This history of medicine review highlights plague events across the centuries. Transmission is by fleas carried on rats, although new theories include via human body lice and infected grain. We discuss symptomatology and treatment options. Pneumonic plague can be weaponized for bioterrorism, highlighting the importance of understanding its clinical syndromes. Carriers of recessive familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) mutations have natural immunity against Y. pestis . During the Black Death, Jews were blamed for the bubonic plague, perhaps because Jews carried FMF mutations and died at lower plague rates than Christians. Blaming minorities for epidemics echoes across history into our current coronavirus pandemic and provides insightful lessons for managing and improving its outcomes.

Clinical Significance

- • The Black Death or bubonic plague killed more than 25 million people in fourteenth-century Europe.

- • Yersinia pestis (the plague bacteria) can be easily weaponized as a bioterrorism agent.

- • Early plague treatment is curative, but its symptomatology can be nonspecific. Modern outbreaks still regularly occur. The plague existed in the ancient world and has killed more than 200 million across centuries.

- • Familial Mediterranean fever carriers have plague immunity, which is an important evolutionary adaptation.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Killing more than 25 million people or at least one third of Europe's population during the fourteenth century, the Black Death or bubonic plague was one of mankind's worst pandemics, invoking direct comparisons to our current coronavirus “modern plague.” 1 , 2 , 3 An ancient disease, its bacterial agent ( Yersinia pestis ) still causes periodic outbreaks and remains endemic in some parts of the world. 4 , 5 , 6 Additionally, because it could be weaponized for world bioterrorism, understanding its clinical syndromes, epidemiology, and treatment options remains critical for medical practitioners. 5 , 6 Finally, recent molecular discoveries linking recessive familial Mediterranean fever mutations to plague immunity have revolutionized how scientists and historians alike view this novel evolutionary adaptation. 7 , 8 This history of medicine article sheds light onto the plague and provides insights that can help us manage the COVID-19 epidemic.

History of Plague Epidemics

The plague has afflicted humanity for thousands of years. 1 , 2 , 3 Molecular studies identified the presence of the Y. pestis plague DNA genome in 2 Bronze Age skeletons dated at roughly 3800 years old. 9 In the biblical book 1 Samuel from approximately 1000 BCE, the Philistines experience an outbreak of tumors associated with rodents, which might have been bubonic plague. 3 Scholars identify 3 plague pandemics. 10 , 11 The first pandemic or Justinian plague probably came from India and reached Constantinople in 541-542 CE. At least 18 waves of plague spread across the Mediterranean basin into distant areas like Persia and Ireland from 541 to 750 CE. 10 , 11

The second pandemic or Black Death arrived in Messina in Sicily, probably from Central Asia via Genoese ships carrying flea-laden rats in October 1347, which initiated a wave of plague infections that rapidly spread across most of Europe like a relentless wildfire. 10 , 11 , 12 In Europe, plague-stricken citizens were often dead within a week of contracting the illness. Ultimately, at least one third of the European population (more than 25 million people) died between 1347 and 1352 from the Black Death. 10 , 11 , 12 The plague spread to France and Spain in 1348 and then to Germany, Switzerland, and Austria. It decimated London in 1349 and reached Scandinavia and northern England by 1350. 10 , 11 , 12 The plague died out by the century's end, but outbreaks resurfaced and spread throughout Europe over the next 400 years. In 1656-1657, two thirds of the population in Naples and Genoa died from the disease. In 1665-1666, London lost about one quarter of its citizens to plague, about 100,000, and the same number died in Vienna in 1679. 3 , 13 , 14 Moscow recorded more than 100,000 plague deaths during 1770-1771. 3 , 13 , 14

The fourteenth-century bubonic plague transformed European society and economies, leading to severe labor shortages in farming and skilled crafts. 1 , 2 , 3 The geopolitical impact included a decline in power and international status of the Italian states. 15 During the Black Death, European Christians blamed their Jewish neighbors for the plague, claiming Jews were poisoning the wells. These beliefs led to massacres and violence. 2 , 16 At least 235 Jewish communities experienced mass persecution and destruction during this period, often preemptively in a futile effort at plague containment. 16 The ancient physicians Hippocrates (c. 460-c. 370 BCE) and Galen (129-c. 210 CE) promoted the miasma theory, or poisoned air, to explain disease transmission, which Medieval Europeans believed caused the Black Death. 11 , 17 People of that period thought warm baths permitted plague miasma to enter humans’ pores, so public baths were closed. Victims’ clothes and possessions were thought contaminated and were burned, and cats were killed as possible transmission agents. So-called “plague doctors” wore protective clothing with a long cape, mask, and a bill-like portion over the mouth and nose containing aromatic substances (partly to block out the putrid smell of decaying corpses), perhaps an early version of the modern hazmat suit 10 ( Figure 1 ).

Costume of the plague doctor. The plague doctor wore a black hat, beaked white mask, which contained aromatic substances to block out the smell of decaying bodies, and a waxed gown. The rod or pointer kept afflicted patients away. The earliest version of a protective hazmat suit. Courtesy National Library of Medicine.

The third plague pandemic began in Yunnan Province in southwest China around 1855, where outbreaks had occurred since 1772, and spread to Taiwan. 10 , 11 , 18 It hit Canton in 1894, where it caused 70,000 deaths, and then appeared in Hong Kong. Ships carried it to Japan, India, Australia, and North and South America between 1910 and 1920. 10 , 11 , 18 An estimated 12 million people died from the plague in India between 1898 and 1918. 19 Rats from merchant ships brought the plague to Chinatown in San Francisco in 1900. 20 Although few European cases of the plague were reported after 1950, isolated outbreaks still occur worldwide. 4 , 20 It is estimated that more than 200 million people have died from the plague throughout human history. 10

Plague Microbiology

Y. pestis is an aerobic, gram-negative coccobacillus in the family Enterobacteriaceae . 21 , 22 , 23 Genetic DNA analysis shows that it diverged from its enteric pathogenic relative, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis , up to 6000 years ago. 24 After incubation for 24 to 48 hours in blood or on MacConkey agar at 37°C, small bacterial colonies can be identified. 21 , 22 , 23 Its primary vector for transmission is the Xenopsylla cheopis flea, although roughly 80 species of fleas can carry it. During the Black Death, the flea was transported by the black rat or Rattus . 21 , 22 , 23 A controversial new theory argues that ectoparasites such as human fleas and lice also spread the disease during the second plague pandemic. 25 Fleas can also survive in infected clothing or grain. 11 , 19 , 20 , 21 The bacteria multiply in infected rodents (more than 280 mammalian species can serve as carriers) and block the fleas’ alimentary canal, causing the fleas to regurgitate the Y. pestis bacteria into its animal host. 11 , 19 , 20 , 21 The bacterium is named for the Pasteur Institute physician Alexandre Yersin, who provided the first, most accurate description of its causative agent in 1894 during the Hong Kong outbreak. However, the Japanese physician Shibasaburo Kitasato was an independent coinvestigator whose bacterial plates were unfortunately contaminated and led to erroneous observations. 19 In 1898, Dr. Paul-Louis Simond in Karachi showed that fleas from infected rats could transmit the disease to healthy rats, and Ricardo Jorge in 1927 reported that wild rodents serve as a plague reservoir. 10

Clinical Presentation, Treatment, and Prophylaxis

There are 3 major clinical forms of the plague. 10 , 21 , 22 , 23 In the most common bubonic subtype, infected persons develop sudden onset of high fevers (>39.4°C), terrible pains in their limbs and abdomen, and headaches generally between 3 and 7 days after exposure. The bacteria reproduce rapidly in lymph nodes located closest to the flea bites, leading to painful swellings (“buboes”) in the groin, cervical, or axillary lymph nodes, which can enlarge to the size of an egg (or up to 10 cm) ( Figure 2 ) 12 . About 60% of untreated victims die within 1 week of exposure as the pus-filled buboes suppurate and the patient succumbs to overwhelming infection. 10 , 21 , 22 , 23 During the time of the Black Death, it must have been truly terrifying to witness otherwise healthy individuals cut down rapidly by a seemingly invisible demon. The rarer septicemic plague form (10%-15% of cases) occurs when the bacteria multiply in the blood, often triggering disseminated intravascular coagulation and gangrene of the extremities, ears, or nose 10 , 21 , 22 , 23 ( Figure 3 ). Finally, the infrequent, fulminant pneumonic plague syndrome represents the only form with human-to-human transmission as inhalation of aerosolized droplets (much like coronavirus transmission) from infected patients or even cats leads rapidly to hemoptysis and death. Because this clinical subtype is specifically aerosolized, pneumonic plague could be used for potential bioterrorist attacks. 5 , 6 , 26 Its initially nonspecific, flu-like symptoms include sudden onset of high fevers and dyspnea within 4 days of plague exposure, progressing quickly to a purulent, frothy, or ultimately bloody cough. 21 , 22 , 23 Chest X-ray for primary pneumonic plague may show lobar pneumonia, which spreads rapidly throughout the lungs. The blood-tinged sputum is highly infectious. 21 , 22 , 23 The latter 2 clinical subtypes are invariably fatal without treatment.

Buboes (swellings). Cervical buboes in a patient with bubonic plague from Madagascar. From Prentice MB, Rahalison L. Plague. Lancet . 2007;369:1196-1207. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60566-2. Copyright Elsevier 2007.

Gangrene from plague sepsis. A man from Oregon developed bubonic plague after being bitten by an infected cat, leading to sepsis and acral amputation. Courtesy Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.