- Créer un compte

- Se connecter

- Contributions

- Éditions multiples

- Œuvres sans date de création

- Œuvres de langue originale en moyen français

- Philosophie

- XVIe siècle

- Activer ou désactiver la limitation de largeur du contenu

The Essays of Montaigne/Book III/Chapter XI

Chapter xi. of cripples. [ edit ].

'Tis now two or three years ago that they made the year ten days shorter in France.—[By the adoption of the Gregorian calendar.]—How many changes may we expect should follow this reformation! it was really moving heaven and earth at once. Yet nothing for all that stirs from its place my neighbours still find their seasons of sowing and reaping, the opportunities of doing their business, the hurtful and propitious days, dust at the same time where they had, time out of mind, assigned them; there was no more error perceived in our old use, than there is amendment found in the alteration; so great an uncertainty there is throughout; so gross, obscure, and obtuse is our perception. 'Tis said that this regulation might have been carried on with less inconvenience, by subtracting for some years, according to the example of Augustus, the Bissextile, which is in some sort a day of impediment and trouble, till we had exactly satisfied this debt, the which itself is not done by this correction, and we yet remain some days in arrear: and yet, by this means, such order might be taken for the future, arranging that after the revolution of such or such a number of years, the supernumerary day might be always thrown out, so that we could not, henceforward, err above four-and-twenty hours in our computation. We have no other account of time but years; the world has for many ages made use of that only; and yet it is a measure that to this day we are not agreed upon, and one that we still doubt what form other nations have variously given to it, and what was the true use of it. What does this saying of some mean, that the heavens in growing old bow themselves down nearer towards us, and put us into an uncertainty even of hours and days? and that which Plutarch says of the months, that astrology had not in his time determined as to the motion of the moon; what a fine condition are we in to keep records of things past. I was just now ruminating, as I often do, what a free and roving thing human reason is. I ordinarily see that men, in things propounded to them, more willingly study to find out reasons than to ascertain truth: they slip over presuppositions, but are curious in examination of consequences; they leave the things, and fly to the causes. Pleasant talkers! The knowledge of causes only concerns him who has the conduct of things; not us, who are merely to undergo them, and who have perfectly full and accomplished use of them, according to our need, without penetrating into the original and essence; wine is none the more pleasant to him who knows its first faculties. On the contrary, both the body and the soul interrupt and weaken the right they have of the use of the world and of themselves, by mixing with it the opinion of learning; effects concern us, but the means not at all. To determine and to distribute appertain to superiority and command; as it does to subjection to accept. Let me reprehend our custom. They commonly begin thus: "How is such a thing done?" Whereas they should say, "Is such a thing done?" Our reason is able to create a hundred other worlds, and to find out the beginnings and contexture; it needs neither matter nor foundation: let it but run on, it builds as well in the air as on the earth, and with inanity as well as with matter: "Dare pondus idonea fumo." ["Able to give weight to smoke."—Persius, v. 20.] I find that almost throughout we should say, "there is no such thing," and should myself often make use of this answer, but I dare not: for they cry that it is an evasion produced from ignorance and weakness of understanding; and I am fain, for the most part, to juggle for company, and prate of frivolous subjects and tales that I believe not a word of; besides that, in truth, 'tis a little rude and quarrelsome flatly to deny a stated fact; and few people but will affirm, especially in things hard to be believed, that they have seen them, or at least will name witnesses whose authority will stop our mouths from contradiction. In this way, we know the foundations and means of things that never were; and the world scuffles about a thousand questions, of which both the Pro and the Con are false. "Ita finitima sunt falsa veris, ut in praecipitem locum non debeat se sapiens committere." ["False things are so near the true, that a wise man should not trust himself in a precipitous place"—Cicero, Acad., ii. 21.] Truth and lies are faced alike; their port, taste, and proceedings are the same, and we look upon them with the same eye. I find that we are not only remiss in defending ourselves from deceit, but that we seek and offer ourselves to be gulled; we love to entangle ourselves in vanity, as a thing conformable to our being. I have seen the birth of many miracles in my time; which, although they were abortive, yet have we not failed to foresee what they would have come to, had they lived their full age. 'Tis but finding the end of the clew, and a man may wind off as much as he will; and there is a greater distance betwixt nothing and the least thing in the world than there is betwixt this and the greatest. Now the first that are imbued with this beginning of novelty, when they set out with their tale, find, by the oppositions they meet with, where the difficulty of persuasion lies, and so caulk up that place with some false piece; [Voltaire says of this passage, "He who would learn to doubt should read this whole chapter of Montaigne, the least methodical of all philosophers, but the wisest and most amiable." —Melanges Historiques, xvii. 694, ed. of Lefevre.] besides that: "Insita hominibus libido alendi de industria rumores," ["Men having a natural desire to nourish reports." —Livy, xxviii. 24.] we naturally make a conscience of restoring what has been lent us, without some usury and accession of our own. The particular error first makes the public error, and afterwards, in turn, the public error makes the particular one; and thus all this vast fabric goes forming and piling itself up from hand to hand, so that the remotest witness knows more about it than those who were nearest, and the last informed is better persuaded than the first. 'Tis a natural progress; for whoever believes anything, thinks it a work of charity to persuade another into the same opinion; which the better to do, he will make no difficulty of adding as much of his own invention as he conceives necessary to his tale to encounter the resistance or want of conception he meets with in others. I myself, who make a great conscience of lying, and am not very solicitous of giving credit and authority to what I say, yet find that in the arguments I have in hand, being heated with the opposition of another, or by the proper warmth of my own narration, I swell and puff up my subject by voice, motion, vigour, and force of words, and moreover, by extension and amplification, not without some prejudice to the naked truth; but I do it conditionally withal, that to the first who brings me to myself, and who asks me the plain and bare truth, I presently surrender my passion, and deliver the matter to him without exaggeration, without emphasis, or any painting of my own. A quick and earnest way of speaking, as mine is, is apt to run into hyperbole. There is nothing to which men commonly are more inclined than to make way for their own opinions; where the ordinary means fail us, we add command, force, fire, and sword. 'Tis a misfortune to be at such a pass, that the best test of truth is the multitude of believers in a crowd, where the number of fools so much exceeds the wise: "Quasi vero quidquam sit tam valde, quam nil sapere, vulgare." ["As if anything were so common as ignorance." —Cicero, De Divin., ii.] "Sanitatis patrocinium est, insanientium turba." ["The multitude of fools is a protection to the wise." —St. Augustine, De Civit. Dei, vi. 10.] 'Tis hard to resolve a man's judgment against the common opinions: the first persuasion, taken from the very subject itself, possesses the simple, and from them diffuses itself to the wise, under the authority of the number and antiquity of the witnesses. For my part, what I should not believe from one, I should not believe from a hundred and one: and I do not judge opinions by years. 'Tis not long since one of our princes, in whom the gout had spoiled an excellent nature and sprightly disposition, suffered himself to be so far persuaded with the report made to him of the marvellous operations of a certain priest who by words and gestures cured all sorts of diseases, as to go a long journey to seek him out, and by the force of his mere imagination, for some hours so persuaded and laid his legs asleep, as to obtain that service from them they had long time forgotten. Had fortune heaped up five or six such-like incidents, it had been enough to have brought this miracle into nature. There was afterwards discovered so much simplicity and so little art in the author of these performances, that he was thought too contemptible to be punished, as would be thought of most such things, were they well examined: "Miramur ex intervallo fallentia." ["We admire after an interval (or at a distance) things that deceive."—Seneca, Ep., 118, 2.] So does our sight often represent to us strange images at a distance that vanish on approaching near: "Nunquam ad liquidum fama perducitur." ["Report is never fully substantiated." —Quintus Curtius, ix. 2.] 'Tis wonderful from how many idle beginnings and frivolous causes such famous impressions commonly, proceed. This it is that obstructs information; for whilst we seek out causes and solid and weighty ends, worthy of so great a name, we lose the true ones; they escape our sight by their littleness. And, in truth, a very prudent, diligent, and subtle inquisition is required in such searches, indifferent, and not prepossessed. To this very hour, all these miracles and strange events have concealed themselves from me: I have never seen greater monster or miracle in the world than myself: one grows familiar with all strange things by time and custom, but the more I frequent and the better I know myself, the more does my own deformity astonish me, the less I understand myself. The principal right of advancing and producing such accidents is reserved to fortune. Passing the day before yesterday through a village two leagues from my house, I found the place yet warm with a miracle that had lately failed of success there, where with first the neighbourhood had been several months amused; then the neighbouring provinces began to take it up, and to run thither in great companies of all sorts of people. A young fellow of the place had one night in sport counterfeited the voice of a spirit in his own house, without any other design at present, but only for sport; but this having succeeded with him better than he expected, to extend his farce with more actors he associated with him a stupid silly country girl, and at last there were three of them of the same age and understanding, who from domestic, proceeded to public, preachings, hiding themselves under the altar of the church, never speaking but by night, and forbidding any light to be brought. From words which tended to the conversion of the world, and threats of the day of judgment (for these are subjects under the authority and reverence of which imposture most securely lurks), they proceeded to visions and gesticulations so simple and ridiculous that—nothing could hardly be so gross in the sports of little children. Yet had fortune never so little favoured the design, who knows to what height this juggling might have at last arrived? These poor devils are at present in prison, and are like shortly to pay for the common folly; and I know not whether some judge will not also make them smart for his. We see clearly into this, which is discovered; but in many things of the like nature that exceed our knowledge, I am of opinion that we ought to suspend our judgment, whether as to rejection or as to reception. Great abuses in the world are begotten, or, to speak more boldly, all the abuses of the world are begotten, by our being taught to be afraid of professing our ignorance, and that we are bound to accept all things we are not able to refute: we speak of all things by precepts and decisions. The style at Rome was that even that which a witness deposed to having seen with his own eyes, and what a judge determined with his most certain knowledge, was couched in this form of speaking: "it seems to me." They make me hate things that are likely, when they would impose them upon me as infallible. I love these words which mollify and moderate the temerity of our propositions: "peradventure; in some sort; some; 'tis said, I think," and the like: and had I been set to train up children I had put this way of answering into their mouths, inquiring and not resolving: "What does this mean? I understand it not; it may be: is it true?" so that they should rather have retained the form of pupils at threescore years old than to go out doctors, as they do, at ten. Whoever will be cured of ignorance must confess it. Iris is the daughter of Thaumas; ["That is, of Admiration. She (Iris, the rainbow) is beautiful, and for that reason, because she has a face to be admired, she is said to have been the daughter of Thamus." —Cicero, De Nat. Deor., iii. 20.] admiration is the foundation of all philosophy, inquisition the progress, ignorance the end. But there is a sort of ignorance, strong and generous, that yields nothing in honour and courage to knowledge; an ignorance which to conceive requires no less knowledge than to conceive knowledge itself. I read in my younger years a trial that Corras, [A celebrated Calvinist lawyer, born at Toulouse; 1513, and assassinated there, 4th October 1572.] a councillor of Toulouse, printed, of a strange incident, of two men who presented themselves the one for the other. I remember (and I hardly remember anything else) that he seemed to have rendered the imposture of him whom he judged to be guilty, so wonderful and so far exceeding both our knowledge and his own, who was the judge, that I thought it a very bold sentence that condemned him to be hanged. Let us have some form of decree that says, "The court understands nothing of the matter" more freely and ingenuously than the Areopagites did, who, finding themselves perplexed with a cause they could not unravel, ordered the parties to appear again after a hundred years. The witches of my neighbourhood run the hazard of their lives upon the report of every new author who seeks to give body to their dreams. To accommodate the examples that Holy Writ gives us of such things, most certain and irrefragable examples, and to tie them to our modern events, seeing that we neither see the causes nor the means, will require another sort-of wit than ours. It, peradventure, only appertains to that sole all-potent testimony to tell us. "This is, and that is, and not that other." God ought to be believed; and certainly with very good reason; but not one amongst us for all that who is astonished at his own narration (and he must of necessity be astonished if he be not out of his wits), whether he employ it about other men's affairs or against himself. I am plain and heavy, and stick to the solid and the probable, avoiding those ancient reproaches: "Majorem fidem homines adhibent iis, quae non intelligunt; —Cupidine humani ingenii libentius obscura creduntur." ["Men are most apt to believe what they least understand: and from the acquisitiveness of the human intellect, obscure things are more easily credited." The second sentence is from Tacitus, Hist. 1. 22.] I see very well that men get angry, and that I am forbidden to doubt upon pain of execrable injuries; a new way of persuading! Thank God, I am not to be cuffed into belief. Let them be angry with those who accuse their opinion of falsity; I only accuse it of difficulty and boldness, and condemn the opposite affirmation equally, if not so imperiously, with them. He who will establish this proposition by authority and huffing discovers his reason to be very weak. For a verbal and scholastic altercation let them have as much appearance as their contradictors; "Videantur sane, non affirmentur modo;" ["They may indeed appear to be; let them not be affirmed (Let them state the probabilities, but not affirm.)" —Cicero, Acad., n. 27.] but in the real consequence they draw from it these have much the advantage. To kill men, a clear and strong light is required, and our life is too real and essential to warrant these supernatural and fantastic accidents. As to drugs and poisons, I throw them out of my count, as being the worst sort of homicides: yet even in this, 'tis said, that men are not always to rely upon the personal confessions of these people; for they have sometimes been known to accuse themselves of the murder of persons who have afterwards been found living and well. In these other extravagant accusations, I should be apt to say, that it is sufficient a man, what recommendation soever he may have, be believed as to human things; but of what is beyond his conception, and of supernatural effect, he ought then only to be believed when authorised by a supernatural approbation. The privilege it has pleased Almighty God to give to some of our witnesses, ought not to be lightly communicated and made cheap. I have my ears battered with a thousand such tales as these: "Three persons saw him such a day in the east three, the next day in the west: at such an hour, in such a place, and in such habit"; assuredly I should not believe it myself. How much more natural and likely do I find it that two men should lie than that one man in twelve hours' time should fly with the wind from east to west? How much more natural that our understanding should be carried from its place by the volubility of our disordered minds, than that one of us should be carried by a strange spirit upon a broomstaff, flesh and bones as we are, up the shaft of a chimney? Let not us seek illusions from without and unknown, we who are perpetually agitated with illusions domestic and our own. Methinks one is pardonable in disbelieving a miracle, at least, at all events where one can elude its verification as such, by means not miraculous; and I am of St. Augustine's opinion, that, "'tis better to lean towards doubt than assurance, in things hard to prove and dangerous to believe." 'Tis now some years ago that I travelled through the territories of a sovereign prince, who, in my favour, and to abate my incredulity, did me the honour to let me see, in his own presence, and in a private place, ten or twelve prisoners of this kind, and amongst others, an old woman, a real witch in foulness and deformity, who long had been famous in that profession. I saw both proofs and free confessions, and I know not what insensible mark upon the miserable creature: I examined and talked with her and the rest as much and as long as I would, and gave the best and soundest attention I could, and I am not a man to suffer my judgment to be made captive by prepossession. In the end, and in all conscience, I should rather have prescribed them hellebore than hemlock; "Captisque res magis mentibus, quam consceleratis similis visa;" ["The thing was rather to be attributed to madness, than malice." ("The thing seemed to resemble minds possessed rather than guilty.") —Livy, viii, 18.] justice has its corrections proper for such maladies. As to the oppositions and arguments that worthy men have made to me, both there, and often in other places, I have met with none that have convinced me, and that have not admitted a more likely solution than their conclusions. It is true, indeed, that the proofs and reasons that are founded upon experience and fact, I do not go about to untie, neither have they any end; I often cut them, as Alexander did the Gordian knot. After all, 'tis setting a man's conjectures at a very high price upon them to cause a man to be roasted alive. We are told by several examples, as Praestantius of his father, that being more profoundly, asleep than men usually are, he fancied himself to be a mare, and that he served the soldiers for a sumpter; and what he fancied himself to be, he really proved. If sorcerers dream so materially; if dreams can sometimes so incorporate themselves with effects, still I cannot believe that therefore our will should be accountable to justice; which I say as one who am neither judge nor privy councillor, and who think myself by many degrees unworthy so to be, but a man of the common sort, born and avowed to the obedience of the public reason, both in its words and acts. He who should record my idle talk as being to the prejudice of the pettiest law, opinion, or custom of his parish, would do himself a great deal of wrong, and me much more; for, in what I say, I warrant no other certainty, but that 'tis what I had then in my thought, a tumultuous and wavering thought. All I say is by way of discourse, and nothing by way of advice: "Nec me pudet, ut istos fateri nescire, quod nesciam;" ["Neither am I ashamed, as they are, to confess my ignorance of what I do not know."—Cicero, Tusc. Quaes., i. 25.] I should not speak so boldly, if it were my due to be believed; and so I told a great man, who complained of the tartness and contentiousness of my exhortations. Perceiving you to be ready and prepared on one part, I propose to you the other, with all the diligence and care I can, to clear your judgment, not to compel it. God has your hearts in His hands, and will furnish you with the means of choice. I am not so presumptuous even as to desire that my opinions should bias you—in a thing of so great importance: my fortune has not trained them up to so potent and elevated conclusions. Truly, I have not only a great many humours, but also a great many opinions, that I would endeavour to make my son dislike, if I had one. What, if the truest are not always the most commodious to man, being of so wild a composition? Whether it be to the purpose or not, tis no great matter: 'tis a common proverb in Italy, that he knows not Venus in her perfect sweetness who has never lain with a lame mistress. Fortune, or some particular incident, long ago put this saying into the mouths of the people; and the same is said of men as well as of women; for the queen of the Amazons answered the Scythian who courted her to love, "Lame men perform best." In this feminine republic, to evade the dominion of the males, they lamed them in their infancy—arms, legs, and other members that gave them advantage over them, and only made use of them in that wherein we, in these parts of the world, make use of them. I should have been apt to think; that the shuffling pace of the lame mistress added some new pleasure to the work, and some extraordinary titillation to those who were at the sport; but I have lately learnt that ancient philosophy has itself determined it, which says that the legs and thighs of lame women, not receiving, by reason of their imperfection, their due aliment, it falls out that the genital parts above are fuller and better supplied and much more vigorous; or else that this defect, hindering exercise, they who are troubled with it less dissipate their strength, and come more entire to the sports of Venus; which also is the reason why the Greeks decried the women-weavers as being more hot than other women by reason of their sedentary trade, which they carry on without any great exercise of the body. What is it we may not reason of at this rate? I might also say of these, that the jaggling about whilst so sitting at work, rouses and provokes their desire, as the swinging and jolting of coaches does that of our ladies. Do not these examples serve to make good what I said at first: that our reasons often anticipate the effect, and have so infinite an extent of jurisdiction that they judge and exercise themselves even on inanity itself and non-existency? Besides the flexibility of our invention to forge reasons of all sorts of dreams, our imagination is equally facile to receive impressions of falsity by very frivolous appearances; for, by the sole authority of the ancient and common use of this proverb, I have formerly made myself believe that I have had more pleasure in a woman by reason she was not straight, and accordingly reckoned that deformity amongst her graces. Torquato Tasso, in the comparison he makes betwixt France and Italy, says that he has observed that our legs are generally smaller than those of the Italian gentlemen, and attributes the cause of it to our being continually on horseback; which is the very same cause from which Suetonius draws a quite opposite conclusion; for he says, on the contrary, that Germanicus had made his legs bigger by the continuation of the same exercise. Nothing is so supple and erratic as our understanding; it is the shoe of Theramenes, fit for all feet. It is double and diverse, and the matters are double and diverse too. "Give me a drachm of silver," said a Cynic philosopher to Antigonus. "That is not a present befitting a king," replied he. "Give me then a talent," said the other. "That is not a present befitting a Cynic." "Seu plures calor ille vias et caeca relaxat Spiramenta, novas veniat qua succus in herbas Seu durat magis, et venas astringit hiantes; Ne tenues pluviae, rapidive potentia colic Acrior, aut Boreae penetrabile frigus adurat." ["Whether the heat opens more passages and secret pores through which the sap may be derived into the new-born herbs; or whether it rather hardens and binds the gaping veins that the small showers and keen influence of the violent sun or penetrating cold of Boreas may not hurt them."—Virg., Georg., i. 89.] "Ogni medaglia ha il suo rovescio." ["Every medal has its reverse."—Italian Proverb.] This is the reason why Clitomachus said of old that Carneades had outdone the labours of Hercules, in having eradicated consent from men, that is to say, opinion and the courage of judging. This so vigorous fancy of Carneades sprang, in my opinion, anciently from the impudence of those who made profession of knowledge and their immeasurable self-conceit. AEsop was set to sale with two other slaves; the buyer asked the first of these what he could do; he, to enhance his own value, promised mountains and marvels, saying he could do this and that, and I know not what; the second said as much of himself or more: when it came to AEsop's turn, and that he was also asked what he could do; "Nothing," said he, "for these two have taken up all before me; they know everything." So has it happened in the school of philosophy: the pride of those who attributed the capacity of all things to the human mind created in others, out of despite and emulation, this opinion, that it is capable of nothing: the one maintain the same extreme in ignorance that the others do in knowledge; to make it undeniably manifest that man is immoderate throughout, and can never stop but of necessity and the want of ability to proceed further.

- Headers applying DefaultSort key

Navigation menu

Guide to the classics: Michel de Montaigne’s Essays

Associate Professor in Philosophy, Deakin University

Disclosure statement

Matthew Sharpe is part of an ARC funded project on modern reinventions of the ancient idea of "philosophy as a way of life", in which Montaigne is a central figure.

Deakin University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

When Michel de Montaigne retired to his family estate in 1572, aged 38, he tells us that he wanted to write his famous Essays as a distraction for his idle mind . He neither wanted nor expected people beyond his circle of friends to be too interested.

His Essays’ preface almost warns us off:

Reader, you have here an honest book; … in writing it, I have proposed to myself no other than a domestic and private end. I have had no consideration at all either to your service or to my glory … Thus, reader, I myself am the matter of my book: there’s no reason that you should employ your leisure upon so frivolous and vain a subject. Therefore farewell.

The ensuing, free-ranging essays, although steeped in classical poetry, history and philosophy, are unquestionably something new in the history of Western thought. They were almost scandalous for their day.

No one before Montaigne in the Western canon had thought to devote pages to subjects as diverse and seemingly insignificant as “Of Smells”, “Of the Custom of Wearing Clothes”, “Of Posting” (letters, that is), “Of Thumbs” or “Of Sleep” — let alone reflections on the unruliness of the male appendage , a subject which repeatedly concerned him.

French philosopher Jacques Rancière has recently argued that modernism began with the opening up of the mundane, private and ordinary to artistic treatment. Modern art no longer restricts its subject matters to classical myths, biblical tales, the battles and dealings of Princes and prelates.

If Rancière is right, it could be said that Montaigne’s 107 Essays, each between several hundred words and (in one case) several hundred pages, came close to inventing modernism in the late 16th century.

Montaigne frequently apologises for writing so much about himself. He is only a second rate politician and one-time Mayor of Bourdeaux, after all. With an almost Socratic irony , he tells us most about his own habits of writing in the essays titled “Of Presumption”, “Of Giving the Lie”, “Of Vanity”, and “Of Repentance”.

But the message of this latter essay is, quite simply, that non, je ne regrette rien , as a more recent French icon sang:

Were I to live my life over again, I should live it just as I have lived it; I neither complain of the past, nor do I fear the future; and if I am not much deceived, I am the same within that I am without … I have seen the grass, the blossom, and the fruit, and now see the withering; happily, however, because naturally.

Montaigne’s persistence in assembling his extraordinary dossier of stories, arguments, asides and observations on nearly everything under the sun (from how to parley with an enemy to whether women should be so demure in matters of sex , has been celebrated by admirers in nearly every generation.

Within a decade of his death, his Essays had left their mark on Bacon and Shakespeare. He was a hero to the enlighteners Montesquieu and Diderot. Voltaire celebrated Montaigne - a man educated only by his own reading, his father and his childhood tutors – as “the least methodical of all philosophers, but the wisest and most amiable”. Nietzsche claimed that the very existence of Montaigne’s Essays added to the joy of living in this world.

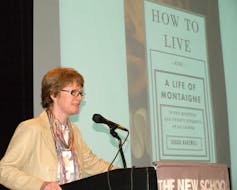

More recently, Sarah Bakewell’s charming engagement with Montaigne, How to Live or a Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer (2010) made the best-sellers’ lists. Even today’s initiatives in teaching philosophy in schools can look back to Montaigne (and his “ On the Education of Children ”) as a patron saint or sage .

So what are these Essays, which Montaigne protested were indistinguishable from their author? (“ My book and I go hand in hand together ”).

It’s a good question.

Anyone who tries to read the Essays systematically soon finds themselves overwhelmed by the sheer wealth of examples, anecdotes, digressions and curios Montaigne assembles for our delectation, often without more than the hint of a reason why.

To open the book is to venture into a world in which fortune consistently defies expectations; our senses are as uncertain as our understanding is prone to error; opposites turn out very often to be conjoined (“ the most universal quality is diversity ”); even vice can lead to virtue. Many titles seem to have no direct relation to their contents. Nearly everything our author says in one place is qualified, if not overturned, elsewhere.

Without pretending to untangle all of the knots of this “ book with a wild and desultory plan ”, let me tug here on a couple of Montaigne’s threads to invite and assist new readers to find their own way.

Philosophy (and writing) as a way of life

Some scholars argued that Montaigne began writing his essays as a want-to-be Stoic , hardening himself against the horrors of the French civil and religious wars , and his grief at the loss of his best friend Étienne de La Boétie through dysentery.

Certainly, for Montaigne, as for ancient thinkers led by his favourites, Plutarch and the Roman Stoic Seneca, philosophy was not solely about constructing theoretical systems, writing books and articles. It was what one more recent admirer of Montaigne has called “ a way of life ”.

Montaigne has little time for forms of pedantry that value learning as a means to insulate scholars from the world, rather than opening out onto it. He writes :

Either our reason mocks us or it ought to have no other aim but our contentment.

We are great fools . ‘He has passed over his life in idleness,’ we say: ‘I have done nothing today.’ What? have you not lived? that is not only the fundamental, but the most illustrious of all your occupations.

One feature of the Essays is, accordingly, Montaigne’s fascination with the daily doings of men like Socrates and Cato the Younger ; two of those figures revered amongst the ancients as wise men or “ sages ”.

Their wisdom, he suggests , was chiefly evident in the lives they led (neither wrote a thing). In particular, it was proven by the nobility each showed in facing their deaths. Socrates consented serenely to taking hemlock, having been sentenced unjustly to death by the Athenians. Cato stabbed himself to death after having meditated upon Socrates’ example , in order not to cede to Julius Caesar’s coup d’état .

To achieve such “philosophic” constancy, Montaigne saw, requires a good deal more than book learning . Indeed, everything about our passions and, above all, our imagination , speaks against achieving that perfect tranquillity the classical thinkers saw as the highest philosophical goal.

We discharge our hopes and fears, very often, on the wrong objects, Montaigne notes , in an observation that anticipates the thinking of Freud and modern psychology. Always, these emotions dwell on things we cannot presently change. Sometimes, they inhibit our ability to see and deal in a supple way with the changing demands of life.

Philosophy, in this classical view, involves a retraining of our ways of thinking, seeing and being in the world. Montaigne’s earlier essay “ To philosophise is to learn how to die ” is perhaps the clearest exemplar of his indebtedness to this ancient idea of philosophy.

Yet there is a strong sense in which all of the Essays are a form of what one 20th century author has dubbed “ self-writing ”: an ethical exercise to “strengthen and enlighten” Montaigne’s own judgement, as much as that of we readers:

And though nobody should read me, have I wasted time in entertaining myself so many idle hours in so pleasing and useful thoughts? … I have no more made my book than my book has made me: it is a book consubstantial with the author, of a peculiar design, a parcel of my life …

As for the seeming disorder of the product, and Montaigne’s frequent claims that he is playing the fool , this is arguably one more feature of the Essays that reflects his Socratic irony. Montaigne wants to leave us with some work to do and scope to find our own paths through the labyrinth of his thoughts, or alternatively, to bobble about on their diverting surfaces .

A free-thinking sceptic

Yet Montaigne’s Essays, for all of their classicism and their idiosyncracies, are rightly numbered as one of the founding texts of modern thought . Their author keeps his own prerogatives, even as he bows deferentially before the altars of ancient heroes like Socrates, Cato, Alexander the Great or the Theban general Epaminondas .

There is a good deal of the Christian, Augustinian legacy in Montaigne’s makeup. And of all the philosophers, he most frequently echoes ancient sceptics like Pyrrho or Carneades who argued that we can know almost nothing with certainty. This is especially true concerning the “ultimate questions” the Catholics and Huguenots of Montaigne’s day were bloodily contesting.

Writing in a time of cruel sectarian violence , Montaigne is unconvinced by the ageless claim that having a dogmatic faith is necessary or especially effective in assisting people to love their neighbours :

Between ourselves, I have ever observed supercelestial opinions and subterranean manners to be of singular accord …

This scepticism applies as much to the pagan ideal of a perfected philosophical sage as it does to theological speculations.

Socrates’ constancy before death, Montaigne concludes, was simply too demanding for most people, almost superhuman . As for Cato’s proud suicide, Montaigne takes liberty to doubt whether it was as much the product of Stoic tranquility, as of a singular turn of mind that could take pleasure in such extreme virtue .

Indeed when it comes to his essays “ Of Moderation ” or “ Of Virtue ”, Montaigne quietly breaks the ancient mold. Instead of celebrating the feats of the world’s Catos or Alexanders, here he lists example after example of people moved by their sense of transcendent self-righteousness to acts of murderous or suicidal excess.

Even virtue can become vicious, these essays imply, unless we know how to moderate our own presumptions.

Of cannibals and cruelties

If there is one form of argument Montaigne uses most often, it is the sceptical argument drawing on the disagreement amongst even the wisest authorities.

If human beings could know if, say, the soul was immortal, with or without the body, or dissolved when we die … then the wisest people would all have come to the same conclusions by now, the argument goes. Yet even the “most knowing” authorities disagree about such things, Montaigne delights in showing us .

The existence of such “ an infinite confusion ” of opinions and customs ceases to be the problem, for Montaigne. It points the way to a new kind of solution, and could in fact enlighten us.

Documenting such manifold differences between customs and opinions is, for him, an education in humility :

Manners and opinions contrary to mine do not so much displease as instruct me; nor so much make me proud as they humble me.

His essay “ Of Cannibals ” for instance, presents all of the different aspects of American Indian culture, as known to Montaigne through travellers’ reports then filtering back into Europe. For the most part, he finds these “savages’” society ethically equal, if not far superior, to that of war-torn France’s — a perspective that Voltaire and Rousseau would echo nearly 200 years later.

We are horrified at the prospect of eating our ancestors. Yet Montaigne imagines that from the Indians’ perspective, Western practices of cremating our deceased, or burying their bodies to be devoured by the worms must seem every bit as callous.

And while we are at it, Montaigne adds that consuming people after they are dead seems a good deal less cruel and inhumane than torturing folk we don’t even know are guilty of any crime whilst they are still alive …

A gay and sociable wisdom

“So what is left then?”, the reader might ask, as Montaigne undermines one presumption after another, and piles up exceptions like they had become the only rule.

A very great deal , is the answer. With metaphysics, theology, and the feats of godlike sages all under a “ suspension of judgment ”, we become witnesses as we read the Essays to a key document in the modern revaluation and valorization of everyday life.

There is, for instance, Montaigne’s scandalously demotic habit of interlacing words, stories and actions from his neighbours, the local peasants (and peasant women) with examples from the greats of Christian and pagan history. As he writes :

I have known in my time a hundred artisans, a hundred labourers, wiser and more happy than the rectors of the university, and whom I had much rather have resembled.

By the end of the Essays, Montaigne has begun openly to suggest that, if tranquillity, constancy, bravery, and honour are the goals the wise hold up for us, they can all be seen in much greater abundance amongst the salt of the earth than amongst the rich and famous:

I propose a life ordinary and without lustre: ‘tis all one … To enter a breach, conduct an embassy, govern a people, are actions of renown; to … laugh, sell, pay, love, hate, and gently and justly converse with our own families and with ourselves … not to give our selves the lie, that is rarer, more difficult and less remarkable …

And so we arrive with these last Essays at a sentiment better known today from another philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche, the author of A Gay Science (1882) .

Montaigne’s closing essays repeat the avowal that: “ I love a gay and civil wisdom … .” But in contrast to his later Germanic admirer, the music here is less Wagner or Beethoven than it is Mozart (as it were), and Montaigne’s spirit much less agonised than gently serene.

It was Voltaire, again, who said that life is a tragedy for those who feel, and a comedy for those who think. Montaigne adopts and admires the comic perspective . As he writes in “Of Experience”:

It is not of much use to go upon stilts , for, when upon stilts, we must still walk with our legs; and when seated upon the most elevated throne in the world, we are still perched on our own bums.

- Classic literature

- Michel de Montaigne

Director, Defence and Security

Project Officer, Student Volunteer Program

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The complete works of Montaigne : essays, travel journal, letters

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

573 Previews

36 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station03.cebu on February 9, 2022

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

- Project Gutenberg

- 73,286 free eBooks

- 33 by Michel de Montaigne

Essays of Michel de Montaigne — Volume 01 by Michel de Montaigne

Read now or download (free!)

Similar books, about this ebook.

- Privacy policy

- About Project Gutenberg

- Terms of Use

- Contact Information

Category : Essays (Montaigne)

Subcategories.

This category has the following 3 subcategories, out of 3 total.

- Essais, 1595 (2 F)

- Exemplaire de Bordeaux (1 C, 2 F)

- Próby (Montaigne), Bibljoteka Boy'a, 1931 (5 F)

Media in category "Essays (Montaigne)"

The following 35 files are in this category, out of 35 total.

- Michel de Montaigne - Sur la tristesse.ogg 6 min 56 s; 6.46 MB

- Books by Michel de Montaigne

- Uses of Wikidata Infobox

Navigation menu

Michel de Montaigne

Given the huge breadth of his readings, Montaigne could have been ranked among the most erudite humanists of the XVIth century. But in the Essays , his aim is above all to exercise his own judgment properly. Readers who might want to convict him of ignorance would find nothing to hold against him, he said, for he was exerting his natural capacities, not borrowed ones. He thought that too much knowledge could prove a burden, preferring to exert his ‘natural judgment’ to displaying his erudition.

3. A Philosophy of Free Judgment

4. montaigne's scepticism, 5. montaigne and relativism, 6. montaigne's legacy on charron and descartes, 7. conclusion, translations in english, secondary sources, translations, related entries.

Montaigne (1533-1592) came from a rich bourgeois family that acquired nobility after his father fought in Italy in the army of King Francis I of France; he came back with the firm intention of bringing refined Italian culture to France. He decorated his Périgord castle in the style of an ancient Roman villa. He also decided that his son would not learn Latin in school. He arranged instead for a German preceptor and the household to speak to him exclusively in Latin at home. So the young Montaigne grew up speaking Latin and reading Vergil, Ovid, and Horace on his own. At the age of six, he was sent to board at the Collège de Guyenne in Bordeaux, which he later praised as the best humanist college in France, though he found fault with humanist colleges in general. Where Montaigne later studied law, or, indeed, whether he ever studied law at all is not clear. The only thing we know with certainty is that his father bought him an office in the Court of Périgueux. He then met Etienne de La Boëtie with whom he formed an intimate friendship and whose death some years later, in 1563, left him deeply distraught. Tired of active life, he retired at the age of only 37 to his father's castle. In the same year, 1571, he was nominated Gentleman of King Charles IX's Ordinary Chamber, and soon thereafter, also of Henri de Navarre's Chamber. He received the decoration of the Order of Saint-Michel, a distinction all the more exceptional as Montaigne's lineage was from recent nobility. On the title page of the first edition (1580) of the Essays , we read: “Essais de Messire Michel Seigneur de Montaigne, Chevalier de l'ordre du Roy, & Gentilhomme ordinaire de sa chambre.” Initially keen to show off his titles and, thus, his social standing, Montaigne had the honorifics removed in the second edition (1582).

Replicating Petrarca's choice in De vita solitaria , Montaigne chose to dedicate himself to the Muses. In his library, which was quite large for the period, he had wisdom formulas carved on the wooden beams. They were drawn from, amongst others, Ecclesiastes , Sextus Empiricus, Lucretius, and other classical authors, whom he read intensively. To escape fits of melancholy, he began to commit his thoughts to paper. In 1580, he undertook a journey to Italy, whose main goal was probably to cure the pain of his kidney stones at thermal resorts. The journey is related in part by a secretary, in part by Montaigne himself, in a manuscript that was only discovered during the 18th century, given the title The Journal of the Journey to Italy , and forgotten soon after. While Montaigne was taking the baths near Pisa, he learnt of his election as Mayor of Bordeaux. He was first tempted to refuse out of modesty, but eventually accepted (he even received a letter from the King urging him to take the post) and was later re-elected. In his second term he came under criticism for having abandoned the town during the great plague in an attempt to protect himself and his family. His time in office was dimmed by the wars of religion between Catholics and Protestants. Several members of his family converted to Protestantism, but Montaigne himself remained a Catholic.

Montaigne wrote three books of Essays . (‘Essay’ was an original name for this kind of work; it became an appreciated genre soon after.) Three main editions are recognized: 1580 (at this stage, only the first two books were written), 1588, and 1595. The last edition, which could not be supervised by Montaigne himself, was edited from the manuscript by his adoptive daughter Marie de Gournay.. Till the end of the 19th century, the copy text for all new editions was that of 1595; Fortunat Strowski and shortly after him Pierre Villey dismissed it in favor of the “Bordeaux copy”, a text of the 1588 edition supplemented by manuscript additions. [ 1 ] Montaigne enriched his text continuously; he preferred to add for the sake of diversity, rather than to correct. [ 2 ] The unity of the work and the order of every single chapter remain problematic. We are unable to detect obvious links from one chapter to the next: in the first book, Montaigne jumps from “ Idleness” (I,8) to “Liars” (I,9), then from “Prompt or slow speech” (I,10) to “Prognostications” (I,11). The random aspect of the work, acknowledged by the author himself, has been a challenge for commentators ever since. Part of the brilliance of the Essays lies in this very ability to elicit various forms of explanatory coherence whilst at the same time defying them. The work is so rich and flexible that it accommodates virtually any academic trend. Yet, it is also so resistant to interpretation that it reveals the limits of each interpretation.

Critical studies of the Essays have, until recently, been mainly of a literary nature. However, to consider Montaigne as a writer rather than as a philosopher can be a way of ignoring a disturbing thinker. It was he after all who shook some fundamental aspects of Western thought, such as the superiority we assign to man over animals, [ 3 ] to European civilization over ‘Barbarians’, [ 4 ] or to reason as an alleged universal standard. In Montaigne we have a writer whose work is deeply infused by philosophical thought. A tradition rooted in the 19th century tends to relegate his work to the status of literary impressionism or to the expression of a frivolous subjectivity. Yet to do him justice, one needs to bear in mind the inseparable unity of thought and style in his work. Montaigne's repeated revisions of his text, as modern editions show with the three letters A, B, C standing for the three main editions, mirror the relationship between the activity of his thought and the Essays as a work in progress. The Essays display both the laboriousness and the delight of thinking.

If it is true, as Edmund Husserl said, that philosophy is a shared endeavor, Montaigne is perhaps the most exemplary of philosophers since his work extensively borrows and quotes from others. Montaigne managed to internalize a huge breadth of reading, so that his erudition does not appear as such. He created a most singular work, yet one that remains deeply rooted in the community of poets, historians, and philosophers. His decision to use only his own judgment in dealing with all sorts of matters, his resolutely distant attitude towards memory and knowledge, his warning that we should not mix God or transcendent principles with the human world, are some of the key elements that characterize Montaigne's position. As a humanist, he considered that one has to assimilate the classics, but above all to display virtue, “according to the opinion of Plato, who says that steadfastness, faith, and sincerity are real philosophy, and the other sciences which aim at other things are only powder and rouge.” [ 5 ]

Montaigne rejects the theoretical or speculative way of philosophizing that prevailed under the Scholastics ever since the Middle Ages. According to him, science does not exist, but only a general belief in science. Petrarch had already criticized the Scholastics for worshiping Aristotle as their God. Siding with the humanists, Montaigne develops a sharp criticism of science “à la mode des Geométriens”, [ 6 ] the mos geometricus deemed to be the most rigorous. It is merely ‘a practice and business of science’, [ 7 ] he says, which is restricted to the University and essentially carried out between masters and their disciples. The main problem of this kind of science is that it makes us spend our time justifying as rational the beliefs we inherit, instead of calling into question their foundations; it makes us label fashionable opinions as truth, instead of gauging their strength. Whereas science should be a free inquiry, it consists only in gibberish discussions on how we should read Aristotle or Galen. [ 8 ] Critical judgment is systematically silenced. Montaigne demands a thought process that would not be tied down by any doctrinaire principle, a thought process that would lead to free enquiry.

If we trace back the birth of modern science, we find that Montaigne as a philosopher was ahead of his time. In 1543, Copernicus put the earth in motion, depriving man of his cosmological centrality. Yet he nevertheless changed little in the medieval conception of the world as a sphere. The Copernican world became an “open” world only with Thomas Digges (1576) although his sky was still situated in space, inhabited by gods and angels. [ 9 ] One has to wait for Giordano Bruno to find the first representative of the modern conception of an infinite universe (1584). But whether Bruno is a modern mind remains controversial (the planets are still animals, etc). Montaigne, on the contrary, is entirely free from the medieval conception of the spheres. He owes his cosmological freedom to his deep interest in ancient philosophers, to Lucretius in particular. In the longest chapter of the Essays , the ‘Apologie de Raymond Sebond’, Montaigne conjures up many opinions, regarding the nature of the cosmos, or the nature of the soul. He weighs the Epicureans' opinion that several worlds exist, against that of the unicity of the world put forth by both Aristotle and Aquinas. He comes out in favor of the former, without ranking his own evaluation as truth.

As a humanist, Montaigne conceived of philosophy as morals. In the chapter “On the education of children”, [ 10 ] education is identified with philosophy, this being understood as the formation of judgment and manners in everyday life: “for philosophy, which, as the molder of judgment and conduct, will be his principal lesson, has the privilege of being everywhere at home”. [ 11 ] Philosophy, which exerts itself essentially by the use of judgment, is significant to the very ordinary, varied and ‘undulating’ [ 12 ] process of life. In fact, under the guise of innocuous anecdotes, Montaigne achieved the humanist revolution in philosophy. He moved from a conception of philosophy conceived of as theoretical science, to a philosophy conceived of as the practice of free judgment. Lamenting that ‘philosophy, even with people of understanding, should be an empty and fantastic name, a thing of no use and no value”, [ 13 ] he asserted that philosophy should be the most cheerful activity. He practised philosophy by setting his judgment to trial, in order to become aware of its weaknesses, but also to get to know its strength. ‘Every movement reveals us”, [ 14 ] but our judgments do so the best. At the beginning of the past century, one of Montaigne's greatest commentators, Pierre Villey, developed the idea that Montaigne truly became himself through writing. This idea remains more or less true, in spite of its obvious link with late romanticist psychology. The Essays remain an exceptional historical testimony of the progress of privacy and individualism, a blossom ing of subjectivity, an attainment of personal maturity that will be copied, but maybe has never since matched. It seems that Montaigne, who dedicated himself to freedom of the mind and peacefulness of the soul, did not have any other aim than cultivating and educating himself. Since philosophy had failed to determine a secure path towards happiness, he committed each individual to do so in his own way. [ 15 ]

Montaigne wants to escape the stifling of thought by knowledge, a wide-spread phenomenon which he called “pedantism’, [ 16 ] an idea that he may have gleaned from the tarnishing of professors by the successful Commedia dell'arte . He praises one of the most famous professors of the day, Adrianus Turnebus, for having combined robust judgment with massive erudition. We have to moderate our thirst for knowledge, just as we do our appetite for pleasure. Siding here with Callicles against Plato, Montaigne asserts that a gentleman should not dedicate himself entirely to philosophy. [ 17 ] Practised with restraint, it proves useful, whereas in excess it leads to eccentricity and insociability. [ 18 ] Reflecting on the education of the children of the aristocracy (chapter I, 26, is dedicated to the countess Diane de Foix, who was then pregnant), Montaigne departs significantly from a traditional humanist education, the very one he himself received. Instead of focusing on the ways and means of making the teaching of Latin more effective, as pedagogues usually did, Montaigne stresses the need for action and playful activities. The child will conform early to social and political customs, but without servility. The use of judgment in every circumstance, as a warrant for freedom and practical intelligence has to remain at the core of education. He transfers the major responsibility of education from the school to everyday life: ‘Wonderful brilliance may be gained for human judgment by getting to know men’. [ 19 ] The priority given to the formation of judgment and character strongly opposes the craving for a powerful memory during his time. He reserves for himself the freedom to pick up bits of knowledge here and there, displaying “nonchalance” intellectually, much in the same way that Castiglione's courtier would use sprezzatura in social relationships. Although Montaigne presents this nonchalance as essential to his nature, his position is not innocent: it allows him to take on the voice now of a Stoic, and then of a Sceptic, now of an Epicurean and then of a Christian. Although his views are never fully original, they always bear his unmistakable mark. Montaigne's thought, which is often rated as modern in so many aspects, remains deeply rooted in the classical tradition. Nourished by the classical authors, Montaigne navigates easily through heaps of knowledge, proposing remarkable literary and philosophical innovations along the way.

Montaigne begins his project to know man by noticing that the same human behavior can have opposite effects, or that opposite conducts can have the same effects: ‘by diverse means we arrive at the same end‘. [ 20 ] Human life cannot be turned into an object of rational theory. Human conduct does not obey universal rules, but a great diversity of rules, among which the most accurate still fall short of the intended mark. ‘Human reason is a tincture infused in about equal strength in all our opinions and ways, whatever their form: infinite in substance, infinite in diversity’ [ 21 ] says the chapter on custom. By focusing on anecdotal experience, Montaigne comes thus to write “the masterpiece of modern moral science”, according to the great commentator Hugo Friedrich. He gives up the moral ambition of telling how men should live, in order to arrive at a non-prejudiced mind for knowing man as he is. “Others form man, I tell of him”. [ 22 ] Man is ever since “without a definition”, as Marcel Conche commented. [ 23 ] In the chapter ‘Apologie de Raimond Sebond’, Montaigne draws from classical and Renaissance knowledge in order to remind us that, in some parts of the world, we find men that bear little resemblance to us. Our experience of man and things should not be perceived as limited by our present standards of judgment. We display a sort of madness when we settle limits for the possible and the impossible. [ 24 ]

Philosophy has failed to secure man a determined idea of his place in the world, or of his nature. Metaphysical or psychological opinions, indeed far too numerous, come as a burden more than as a help. Montaigne pursues his quest for knowledge through experience; the meaning of concepts is not set down by means of a definition, it is related to common language or to historical examples. One of the essential elements of experience is the ability to reflect on one's actions and thoughts. Montaigne is engaging in a case-by-case gnôti seauton , “know thyself”: although truth in general is not truly an appropriate object for human faculties, we can reflect on our experience. What counts is not the fact that we eventually know the truth or not, but rather the way in which we seek it. [ 25 ] “The question is not who will hit the ring, but who will make the best runs at it.” The aim is to properly exercise our judgment.

Montaigne's thinking baffles our most common categories. The vision of an ever-changing world that he developed threatens the being of all things. ‘We have no communication with being’. [ 26 ] We wrongly take that which appears for that which is, and we indulge in a dogmatic, deceptive language that is cut off from an ever-changing reality. We ought to be more careful with our use of language. Montaigne would prefer that children be taught other ways of speaking, more appropriate to the nature of human inquiry, such as ‘What does that mean ?’, ‘I do not understand it’, ‘This might be’, ‘Is it true?’ [ 27 ] Montaigne himself is fond of ‘these formulas that soften the boldness of our propositions’: “perhaps”, “to some extent”, “they say”, “I think”, [ 28 ] and the like. Criticism on theory and dogmatism permeates for example his reflexion on politics. Because social order is too complicated to be mastered by individual reason, he deems conservatism as the wisest stance. [ 29 ] This policy is grounded on the general evaluation that change is usually more damaging than the conservation of social institutions. Nevertheless, there may be certain circumstances that advocate change as a better solution, as history sometimes showed. Reason being then unable to decide a priori , judgment must come into play and alternate its views.

With Cornelius Agrippa, Henri Estienne or Francisco Sanchez, among others, Montaigne has largely contributed to the rebirth of scepticism during the XVIth century. His literary encounter with Sextus produced a decisive shock: around 1576, when Montaigne had his own personal medal coined, he had it engraved with his age, with “ Epecho ” , “I abstain” in Greek, and another Sceptic motto in French: ‘ Que sais-je ?’: what do I know ?. At this period in his life, Montaigne is thought to have undergone a “sceptical crisis”, as Pierre Villey famously commented. In fact, this interpretation dates back to Pascal, for whom scepticism could only be a sort of momentary frenzy. [ 30 ] The “Apologie de Raimond Sebond”, the longest chapter of the Essays , bears the sign of intellectual despair that Montaigne manages to shake off elsewhere. Another interpretation of scepticism formulates it as a strategy used to comfort “fideism”: because reason is unable to demonstrate religious dogmas, we must rely on spiritual revelation and faith. The paradigm of this interpretation has been delivered by Richard Popkin in his History of Scepticism . Montaigne appears here as a founding father of the Counter Reformation, being the leader of the “Nouveaux Pyrrhoniens’, for whom scepticism is used as a means to an end, that is, to neutralize the grip that philosophy once had on religion.

Commentators now agree upon the fact that Montaigne largely transformed the type of scepticism he borrowed from Sextus. The two sides of the scale are never perfectly balanced, since reason always tips the scale in favor of the present at hand. This imbalance undermines the key mechanism of isosthenia (the equality of strength of the two opposing arguments). Since the suspension of judgment cannot be said to occur “casually”, as Sextus Empiricus would like it to, judgment must abstain from giving its assent. In fact, the sources of Montaigne's scepticism are much wider: his child readings of Ovid's Metamorphosis , the in utramque partem academic debate he practised at the Collège de Guyenne (a pro and contra discussion inherited from Aristotle and Cicero) and the humanist philosophy of action, shaped his mind early on. Through them, he learned repeatedly that rational appearances are deceptive. In most of the chapters of the Essays , Montaigne now and then reverses his judgment: these sudden shifts of perspective are designed to escape adherence, and to tackle the matter from another point of view. [ 31 ] The Essays mirror a discreet conduct of judgment, in keeping with the formula iudicio alternante , which we still find engraved today on the beams of the Périgord castle's library. The aim is not to ruin arguments by opposing them, as it is the case in the Pyrrhonian ‘antilogy’, but rather to counterbalance a single opinion by taking into account other opinions. In order to work, each scale of judgment has to be laden. If we take morals, for example, Montaigne refers to varied moral authorities, one of them being custom and the other reason. Against every form of dogmatism, Montaigne returns moral life to its original diversity and inherent uneasiness. Through philosophy, he seeks full accordance with the diversity of life: “As for me, I love life and cultivate as God has been pleased to grant it to us”. [ 32 ]

We find two readings of Montaigne as a Sceptic. The first one concentrates on the polemical, negative arguments drawn from Sextus Empiricus, at the end of the ‘Apology’. This hard-line scepticism draws the picture of man as “humiliated”. [ 33 ] Its aim is essentially to fight the pretensions of reason and to annihilate human knowledge. “Truth”, “being” and “justice” are equally dismissed as unattainable. Doubt foreshadows Descartes' Meditations , on the problem of the reality of the outside world. Dismissing the objective value of one's representations, Montaigne would have created the long-lasting problem of ‘solipsism’. We notice, nevertheless, that he does not question the reality of things — except occasionally at the very end of the 'Apology' — but the value of opinions and men. The second reading of his scepticism puts forth that Cicero's probabilism is of far greater significance in shaping the sceptical content of the Essays . After the 1570's, Montaigne no longer read Sextus; additions show, however, that he took up a more and more extensive reading of Cicero's philosophical writings. We assume that, in his search for polemical arguments against rationalism during the 1570's, Montaigne borrowed much from Sextus, but as he got tired of the sceptical machinery, and understood scepticism rather as an ethics of judgment, he went back to Cicero. [ 34 ] The paramount importance of the Academica for XVI th century thought has been underlined by Charles B. Schmitt. In the free enquiry, which Cicero engaged throughout the varied doctrines, the humanists found an ideal mirror of their own relationship with the Classics. “The Academy, of which I am a follower, gives me the opportunity to hold an opinion as if it were ours, as soon as it shows itself to be highly probable” [ 35 ] wrote Cicero in the De Officiis . Reading Seneca, Montaigne will think as if he were a member of the Stoa; then changing for Lucretius, he will think as if he had become an Epicurean, and so on. Doctrines or opinions, beside historical stuff and personal experiences, make up the nourishment of judgment. Montaigne assimilates opinions, according to what appears to him as true, without taking it to be absolutely true. He insists on the dialogical nature of thought, referring to Socrates' way of keeping the discussion going: “The leader of <Plato's> dialogues, Socrates, is always asking questions and stirring up discussion, never concluding, never satisfying….” [ 36 ] Judgment has to determine the most convincing position, or at least to determine the strengths and weaknesses of each position. The simple dismissal of truth would be too dogmatic a position; but if absolute truth is lacking, we still have the possibility to balance opinions. We have resources enough, to evaluate the various authorities that we have to deal with in ordinary life.

The original failure of commentators was perhaps in labelling Montaigne's thought as “sceptic” without reflecting on the original meaning of the essay. Montaigne's exercise of judgment is an exercise of ‘natural judgment’, which means that judgment does not need any principle or any rule as a presupposition. In this way, many aspects of Montaigne's thinking can be considered as sceptical, although they were not used for the sake of scepticism. For example, when Montaigne sets down the exercise of doubt as a good start in education, he understands doubt as part of the process of the formation of judgment. This process should lead to wisdom, characterized as ‘always joyful’. [ 37 ] Montaigne's scepticism is not a desperate one. On the contrary, it offers the reader a sort of jubilation which relies on the modest but effective pleasure in dismissing knowledge, thus making room for the exercise of one's natural faculties.

Renaissance thinkers strongly felt the necessity to revise their discourse on man. But no one accentuated this necessity more than Montaigne: what he was looking for, when reading historians or travellers such as Lopez de Gomara's History of Indies , was the utmost variety of beliefs and customs that would enrich his image of man. Neither the Hellenistic Sage, nor the Christian Saint, nor the Renaissance Scholar, are unquestioned models in the Essays . Instead, Montaigne is considering real men, who are the product of customs. “Here they live on human flesh; there it is an act of piety to kill one's father at a certain age….” [ 38 ] The importance of custom plays a polemical part: alongside with scepticism, the strength of imagination (chapter I,21) or Fortune (chapters I,1, I,24, etc.), it contributes to the devaluation of reason and will. It is bound to destroy the spontaneous trust that we do know the truth, and that we live according to justice. During the XVIth century, the jurists of the “French school of law” showed that the law is tied up with historical determinations. [ 39 ] In chapter I,23, ‘On custom’, Montaigne seems to extrapolate on this idea : our opinions and conducts being everywhere the product of custom, reference to universal “reason”, “truth”, or “justice” is to be dismissed as an illusion. Pierre Villey was the first to use the terms ‘relativity’ and “relativism”, which proved to be useful tools when commenting on the fact that Montaigne acknowledges that no universal reason presides over the birth of our beliefs. [ 40 ] The notion of absolute truth, applied to human matters, vitiates the understanding and wreaks havoc in society. Upon further reflexion, contingent customs impact everything: ‘in short, to my way of thinking, there is nothing that custom will not or cannot do’. [ 41 ] Montaigne calls it “Circe's drink”. [ 42 ] Custom is a sort of witch, whose spell, among other effects, casts moral illusion. “The laws of conscience, which we say are born from nature, are born of custom. Each man, holding in inward veneration the opinions and the behavior approved and accepted around him…,’ [ 43 ] obeys custom in all his actions and thoughts. The power of custom, indeed, not only guides man in his behavior, but also persuades him of its legitimacy. What is crime for one person will appear normal to another. In the XVIIth century, Pascal will use this argument when challenging the pretension of philosophers of knowing truth. One century later, David Hume will lay stress on the fact that the power of custom is all the stronger, specifically because we are not aware of it. What are we supposed to do, then, if our reason is so flexible that it “changes with two degrees of elevation towards the pole”, as Pascal says? [ 44 ] For Pascal, only one alternative exists, faith in Jesus Christ. However, it is more complicated in the case of Montaigne. Getting to know all sorts of customs, through his readings or travels, he makes an exemplary effort to open his mind. “We are all huddled and concentrated in ourselves, and our vision is reduced to the length of our nose”. [ 45 ] Custom's grip is so strong that it is dubious as to whether we are in a position to become aware of it and therefore shake off its power.

Montaigne was hailed by Claude Lévi-Strauss as the progenitor of the human sciences, and the pioneer of cultural relativism. [ 46 ] However, Montaigne has not been willing to indulge entirely in relativism. Judgment is at first sight unable to stop the relativistic discourse, but it is not left without remedy when facing the power of custom. Inner freedom of thought is the first counterweight we can make use of, for example when criticizing an existing law. Customs are not almighty, since their authority can be reflected upon, evaluated or challenged by individual judgment. The comparative method can also be applied to the freeing of judgment: although lacking a universal standard, we can nevertheless stand back from particular customs, by the mere fact of comparing them. Montaigne thus denounces the fanaticism and the cruelty displayed by Christians against one another during the civil wars in France which he compares to cannibalism: “I think there is more barbarity in eating a man alive than in eating him dead, and in tearing by tortures and the rack a body still full of feeling….” [ 47 ] The meaning of the word ‘barbarity’ is not merely relative to a culture or a point of view, since there are degrees of barbarity. Passing a judgment on cannibals, Montaigne also says: “So we may well call these people barbarians, in respect to the rules of reason, but not in respect to ourselves, who surpass them in every kind of barbarity….” [ 48 ] Judgment is still endowed with the possibility of postulating universal standards, such as “reason” or “nature”, which help when evaluating actions and behaviors. Although Montaigne maintains in the ‘Apologie’ that true reason and true justice are only known by God, he asserts in other chapters that these standards are somehow accessible to man, since they allow judgment to consider customs as particular and contingent rules. [ 49 ] In order to criticize the changeable and the relative, we must suppose that our judgment is still able to “bring things back to truth and reason”. [ 50 ] Man is everywhere enslaved by custom, but this does not mean that we should accept the numbing of our mind. Montaigne elaborates a pedagogy, which rests on the practice of judgment itself. The task of the pupil is not to repeat what the master said, but, on a given subject of problem, to confront his judgment with the master's one. Moreover, relativistic readings of the Essays are forced to ignore certain passages that carry a more rationalistic tone. “The violent detriment inflicted by custom” (I,23) is certainly not a praise of custom, but an invitation to escape it. In the same way that Circe's potion has changed men into pigs, custom turns their intelligence into stupidity. In the toughest cases, Montaigne's critical use of judgment aims at giving ‘a good whiplash to the ordinary stupidity of judgment.’ [ 51 ] In many other places, Montaigne boasts of himself being able to resist vulgar opinion. Independence of thinking, alongside with clear-mindedness and good faith, are the first virtues a young gentleman should acquire.

Pierre Charron was Montaigne's friend and official heir. In De la sagesse (1601 and 1604), he re-organized many of his master's ideas, setting aside the most disturbing ones. His work is now usually dismissed as a dogmatic misrepresentation of Montaigne's thought. Nevertheless, his book was given priority over the Essays themselves during the whole 17th century, especially after Malebranche's critics conspired to have the Essays included in the Roman Index of 1677. Montaigne's historical influence must be reckoned through the lens of this mediation. Moreover, Charron's reading is not simply faulty. According to him, wisdom relies on the readiness of judgment to revise itself towards a more favorable outcome: [ 52 ] this idea is one of the most remarkable readings of the Essays in the early history of their reception.