- Previous Article

- Next Article

Case Presentation

Case study: a patient with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes and complex comorbidities whose diabetes care is managed by an advanced practice nurse.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Cite Icon Cite

- Get Permissions

Geralyn Spollett; Case Study: A Patient With Uncontrolled Type 2 Diabetes and Complex Comorbidities Whose Diabetes Care Is Managed by an Advanced Practice Nurse. Diabetes Spectr 1 January 2003; 16 (1): 32–36. https://doi.org/10.2337/diaspect.16.1.32

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

The specialized role of nursing in the care and education of people with diabetes has been in existence for more than 30 years. Diabetes education carried out by nurses has moved beyond the hospital bedside into a variety of health care settings. Among the disciplines involved in diabetes education, nursing has played a pivotal role in the diabetes team management concept. This was well illustrated in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) by the effectiveness of nurse managers in coordinating and delivering diabetes self-management education. These nurse managers not only performed administrative tasks crucial to the outcomes of the DCCT, but also participated directly in patient care. 1

The emergence and subsequent growth of advanced practice in nursing during the past 20 years has expanded the direct care component, incorporating aspects of both nursing and medical care while maintaining the teaching and counseling roles. Both the clinical nurse specialist (CNS) and nurse practitioner (NP) models, when applied to chronic disease management, create enhanced patient-provider relationships in which self-care education and counseling is provided within the context of disease state management. Clement 2 commented in a review of diabetes self-management education issues that unless ongoing management is part of an education program, knowledge may increase but most clinical outcomes only minimally improve. Advanced practice nurses by the very nature of their scope of practice effectively combine both education and management into their delivery of care.

Operating beyond the role of educator, advanced practice nurses holistically assess patients’ needs with the understanding of patients’ primary role in the improvement and maintenance of their own health and wellness. In conducting assessments, advanced practice nurses carefully explore patients’ medical history and perform focused physical exams. At the completion of assessments, advanced practice nurses, in conjunction with patients, identify management goals and determine appropriate plans of care. A review of patients’ self-care management skills and application/adaptation to lifestyle is incorporated in initial histories, physical exams, and plans of care.

Many advanced practice nurses (NPs, CNSs, nurse midwives, and nurse anesthetists) may prescribe and adjust medication through prescriptive authority granted to them by their state nursing regulatory body. Currently, all 50 states have some form of prescriptive authority for advanced practice nurses. 3 The ability to prescribe and adjust medication is a valuable asset in caring for individuals with diabetes. It is a crucial component in the care of people with type 1 diabetes, and it becomes increasingly important in the care of patients with type 2 diabetes who have a constellation of comorbidities, all of which must be managed for successful disease outcomes.

Many studies have documented the effectiveness of advanced practice nurses in managing common primary care issues. 4 NP care has been associated with a high level of satisfaction among health services consumers. In diabetes, the role of advanced practice nurses has significantly contributed to improved outcomes in the management of type 2 diabetes, 5 in specialized diabetes foot care programs, 6 in the management of diabetes in pregnancy, 7 and in the care of pediatric type 1 diabetic patients and their parents. 8 , 9 Furthermore, NPs have also been effective providers of diabetes care among disadvantaged urban African-American patients. 10 Primary management of these patients by NPs led to improved metabolic control regardless of whether weight loss was achieved.

The following case study illustrates the clinical role of advanced practice nurses in the management of a patient with type 2 diabetes.

A.B. is a retired 69-year-old man with a 5-year history of type 2 diabetes. Although he was diagnosed in 1997, he had symptoms indicating hyperglycemia for 2 years before diagnosis. He had fasting blood glucose records indicating values of 118–127 mg/dl, which were described to him as indicative of “borderline diabetes.” He also remembered past episodes of nocturia associated with large pasta meals and Italian pastries. At the time of initial diagnosis, he was advised to lose weight (“at least 10 lb.”), but no further action was taken.

Referred by his family physician to the diabetes specialty clinic, A.B. presents with recent weight gain, suboptimal diabetes control, and foot pain. He has been trying to lose weight and increase his exercise for the past 6 months without success. He had been started on glyburide (Diabeta), 2.5 mg every morning, but had stopped taking it because of dizziness, often accompanied by sweating and a feeling of mild agitation, in the late afternoon.

A.B. also takes atorvastatin (Lipitor), 10 mg daily, for hypercholesterolemia (elevated LDL cholesterol, low HDL cholesterol, and elevated triglycerides). He has tolerated this medication and adheres to the daily schedule. During the past 6 months, he has also taken chromium picolinate, gymnema sylvestre, and a “pancreas elixir” in an attempt to improve his diabetes control. He stopped these supplements when he did not see any positive results.

He does not test his blood glucose levels at home and expresses doubt that this procedure would help him improve his diabetes control. “What would knowing the numbers do for me?,” he asks. “The doctor already knows the sugars are high.”

A.B. states that he has “never been sick a day in my life.” He recently sold his business and has become very active in a variety of volunteer organizations. He lives with his wife of 48 years and has two married children. Although both his mother and father had type 2 diabetes, A.B. has limited knowledge regarding diabetes self-care management and states that he does not understand why he has diabetes since he never eats sugar. In the past, his wife has encouraged him to treat his diabetes with herbal remedies and weight-loss supplements, and she frequently scans the Internet for the latest diabetes remedies.

During the past year, A.B. has gained 22 lb. Since retiring, he has been more physically active, playing golf once a week and gardening, but he has been unable to lose more than 2–3 lb. He has never seen a dietitian and has not been instructed in self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG).

A.B.’s diet history reveals excessive carbohydrate intake in the form of bread and pasta. His normal dinners consist of 2 cups of cooked pasta with homemade sauce and three to four slices of Italian bread. During the day, he often has “a slice or two” of bread with butter or olive oil. He also eats eight to ten pieces of fresh fruit per day at meals and as snacks. He prefers chicken and fish, but it is usually served with a tomato or cream sauce accompanied by pasta. His wife has offered to make him plain grilled meats, but he finds them “tasteless.” He drinks 8 oz. of red wine with dinner each evening. He stopped smoking more than 10 years ago, he reports, “when the cost of cigarettes topped a buck-fifty.”

The medical documents that A.B. brings to this appointment indicate that his hemoglobin A 1c (A1C) has never been <8%. His blood pressure has been measured at 150/70, 148/92, and 166/88 mmHg on separate occasions during the past year at the local senior center screening clinic. Although he was told that his blood pressure was “up a little,” he was not aware of the need to keep his blood pressure ≤130/80 mmHg for both cardiovascular and renal health. 11

A.B. has never had a foot exam as part of his primary care exams, nor has he been instructed in preventive foot care. However, his medical records also indicate that he has had no surgeries or hospitalizations, his immunizations are up to date, and, in general, he has been remarkably healthy for many years.

Physical Exam

A physical examination reveals the following:

Weight: 178 lb; height: 5′2″; body mass index (BMI): 32.6 kg/m 2

Fasting capillary glucose: 166 mg/dl

Blood pressure: lying, right arm 154/96 mmHg; sitting, right arm 140/90 mmHg

Pulse: 88 bpm; respirations 20 per minute

Eyes: corrective lenses, pupils equal and reactive to light and accommodation, Fundi-clear, no arteriolovenous nicking, no retinopathy

Thyroid: nonpalpable

Lungs: clear to auscultation

Heart: Rate and rhythm regular, no murmurs or gallops

Vascular assessment: no carotid bruits; femoral, popliteal, and dorsalis pedis pulses 2+ bilaterally

Neurological assessment: diminished vibratory sense to the forefoot, absent ankle reflexes, monofilament (5.07 Semmes-Weinstein) felt only above the ankle

Lab Results

Results of laboratory tests (drawn 5 days before the office visit) are as follows:

Glucose (fasting): 178 mg/dl (normal range: 65–109 mg/dl)

Creatinine: 1.0 mg/dl (normal range: 0.5–1.4 mg/dl)

Blood urea nitrogen: 18 mg/dl (normal range: 7–30 mg/dl)

Sodium: 141 mg/dl (normal range: 135–146 mg/dl)

Potassium: 4.3 mg/dl (normal range: 3.5–5.3 mg/dl)

Lipid panel

• Total cholesterol: 162 mg/dl (normal: <200 mg/dl)

• HDL cholesterol: 43 mg/dl (normal: ≥40 mg/dl)

• LDL cholesterol (calculated): 84 mg/dl (normal: <100 mg/dl)

• Triglycerides: 177 mg/dl (normal: <150 mg/dl)

• Cholesterol-to-HDL ratio: 3.8 (normal: <5.0)

AST: 14 IU/l (normal: 0–40 IU/l)

ALT: 19 IU/l (normal: 5–40 IU/l)

Alkaline phosphotase: 56 IU/l (normal: 35–125 IU/l)

A1C: 8.1% (normal: 4–6%)

Urine microalbumin: 45 mg (normal: <30 mg)

Based on A.B.’s medical history, records, physical exam, and lab results, he is assessed as follows:

Uncontrolled type 2 diabetes (A1C >7%)

Obesity (BMI 32.4 kg/m 2 )

Hyperlipidemia (controlled with atorvastatin)

Peripheral neuropathy (distal and symmetrical by exam)

Hypertension (by previous chart data and exam)

Elevated urine microalbumin level

Self-care management/lifestyle deficits

• Limited exercise

• High carbohydrate intake

• No SMBG program

Poor understanding of diabetes

A.B. presented with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes and a complex set of comorbidities, all of which needed treatment. The first task of the NP who provided his care was to select the most pressing health care issues and prioritize his medical care to address them. Although A.B. stated that his need to lose weight was his chief reason for seeking diabetes specialty care, his elevated glucose levels and his hypertension also needed to be addressed at the initial visit.

The patient and his wife agreed that a referral to a dietitian was their first priority. A.B. acknowledged that he had little dietary information to help him achieve weight loss and that his current weight was unhealthy and “embarrassing.” He recognized that his glucose control was affected by large portions of bread and pasta and agreed to start improving dietary control by reducing his portion size by one-third during the week before his dietary consultation. Weight loss would also be an important first step in reducing his blood pressure.

The NP contacted the registered dietitian (RD) by telephone and referred the patient for a medical nutrition therapy assessment with a focus on weight loss and improved diabetes control. A.B.’s appointment was scheduled for the following week. The RD requested that during the intervening week, the patient keep a food journal recording his food intake at meals and snacks. She asked that the patient also try to estimate portion sizes.

Although his physical activity had increased since his retirement, it was fairly sporadic and weather-dependent. After further discussion, he realized that a week or more would often pass without any significant form of exercise and that most of his exercise was seasonal. Whatever weight he had lost during the summer was regained in the winter, when he was again quite sedentary.

A.B.’s wife suggested that the two of them could walk each morning after breakfast. She also felt that a treadmill at home would be the best solution for getting sufficient exercise in inclement weather. After a short discussion about the positive effect exercise can have on glucose control, the patient and his wife agreed to walk 15–20 minutes each day between 9:00 and 10:00 a.m.

A first-line medication for this patient had to be targeted to improving glucose control without contributing to weight gain. Thiazolidinediones (i.e., rosiglitizone [Avandia] or pioglitizone [Actos]) effectively address insulin resistance but have been associated with weight gain. 12 A sulfonylurea or meglitinide (i.e., repaglinide [Prandin]) can reduce postprandial elevations caused by increased carbohydrate intake, but they are also associated with some weight gain. 12 When glyburide was previously prescribed, the patient exhibited signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia (unconfirmed by SMBG). α-Glucosidase inhibitors (i.e., acarbose [Precose]) can help with postprandial hyperglycemia rise by blunting the effect of the entry of carbohydrate-related glucose into the system. However, acarbose requires slow titration, has multiple gastrointestinal (GI) side effects, and reduces A1C by only 0.5–0.9%. 13 Acarbose may be considered as a second-line therapy for A.B. but would not fully address his elevated A1C results. Metformin (Glucophage), which reduces hepatic glucose production and improves insulin resistance, is not associated with hypoglycemia and can lower A1C results by 1%. Although GI side effects can occur, they are usually self-limiting and can be further reduced by slow titration to dose efficacy. 14

After reviewing these options and discussing the need for improved glycemic control, the NP prescribed metformin, 500 mg twice a day. Possible GI side effects and the need to avoid alcohol were of concern to A.B., but he agreed that medication was necessary and that metformin was his best option. The NP advised him to take the medication with food to reduce GI side effects.

The NP also discussed with the patient a titration schedule that increased the dosage to 1,000 mg twice a day over a 4-week period. She wrote out this plan, including a date and time for telephone contact and medication evaluation, and gave it to the patient.

During the visit, A.B. and his wife learned to use a glucose meter that features a simple two-step procedure. The patient agreed to use the meter twice a day, at breakfast and dinner, while the metformin dose was being titrated. He understood the need for glucose readings to guide the choice of medication and to evaluate the effects of his dietary changes, but he felt that it would not be “a forever thing.”

The NP reviewed glycemic goals with the patient and his wife and assisted them in deciding on initial short-term goals for weight loss, exercise, and medication. Glucose monitoring would serve as a guide and assist the patient in modifying his lifestyle.

A.B. drew the line at starting an antihypertensive medication—the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor enalapril (Vasotec), 5 mg daily. He stated that one new medication at a time was enough and that “too many medications would make a sick man out of me.” His perception of the state of his health as being represented by the number of medications prescribed for him gave the advanced practice nurse an important insight into the patient’s health belief system. The patient’s wife also believed that a “natural solution” was better than medication for treating blood pressure.

Although the use of an ACE inhibitor was indicated both by the level of hypertension and by the presence of microalbuminuria, the decision to wait until the next office visit to further evaluate the need for antihypertensive medication afforded the patient and his wife time to consider the importance of adding this pharmacotherapy. They were quite willing to read any materials that addressed the prevention of diabetes complications. However, both the patient and his wife voiced a strong desire to focus their energies on changes in food and physical activity. The NP expressed support for their decision. Because A.B. was obese, weight loss would be beneficial for many of his health issues.

Because he has a sedentary lifestyle, is >35 years old, has hypertension and peripheral neuropathy, and is being treated for hypercholestrolemia, the NP performed an electrocardiogram in the office and referred the patient for an exercise tolerance test. 11 In doing this, the NP acknowledged and respected the mutually set goals, but also provided appropriate pre-exercise screening for the patient’s protection and safety.

In her role as diabetes educator, the NP taught A.B. and his wife the importance of foot care, demonstrating to the patient his inability to feel the light touch of the monofilament. She explained that the loss of protective sensation from peripheral neuropathy means that he will need to be more vigilant in checking his feet for any skin lesions caused by poorly fitting footwear worn during exercise.

At the conclusion of the visit, the NP assured A.B. that she would share the plan of care they had developed with his primary care physician, collaborating with him and discussing the findings of any diagnostic tests and procedures. She would also work in partnership with the RD to reinforce medical nutrition therapies and improve his glucose control. In this way, the NP would facilitate the continuity of care and keep vital pathways of communication open.

Advanced practice nurses are ideally suited to play an integral role in the education and medical management of people with diabetes. 15 The combination of clinical skills and expertise in teaching and counseling enhances the delivery of care in a manner that is both cost-reducing and effective. Inherent in the role of advanced practice nurses is the understanding of shared responsibility for health care outcomes. This partnering of nurse with patient not only improves care but strengthens the patient’s role as self-manager.

Geralyn Spollett, MSN, C-ANP, CDE, is associate director and an adult nurse practitioner at the Yale Diabetes Center, Department of Endocrinology and Metabolism, at Yale University in New Haven, Conn. She is an associate editor of Diabetes Spectrum.

Note of disclosure: Ms. Spollett has received honoraria for speaking engagements from Novo Nordisk Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Aventis and has been a paid consultant for Aventis. Both companies produce products and devices for the treatment of diabetes.

Email alerts

- Advanced Practice Care: Advanced Practice Care in Diabetes: Epilogue

- Advanced Practice Care: Advanced Practice Care in Diabetes: Preface

- Online ISSN 1944-7353

- Print ISSN 1040-9165

- Diabetes Care

- Clinical Diabetes

- Diabetes Spectrum

- Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes

- Scientific Sessions Abstracts

- BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care

- ShopDiabetes.org

- ADA Professional Books

Clinical Compendia

- Clinical Compendia Home

- Latest News

- DiabetesPro SmartBrief

- Special Collections

- DiabetesPro®

- Diabetes Food Hub™

- Insulin Affordability

- Know Diabetes By Heart™

- About the ADA

- Journal Policies

- For Reviewers

- Advertising in ADA Journals

- Reprints and Permission for Reuse

- Copyright Notice/Public Access Policy

- ADA Professional Membership

- ADA Member Directory

- Diabetes.org

- X (Twitter)

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Terms & Conditions

- Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

- © Copyright American Diabetes Association

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Hypothesis and theory article, type 2 diabetes mellitus: a pathophysiologic perspective.

- Department of Medicine, Duke University, Durham, NC, United States

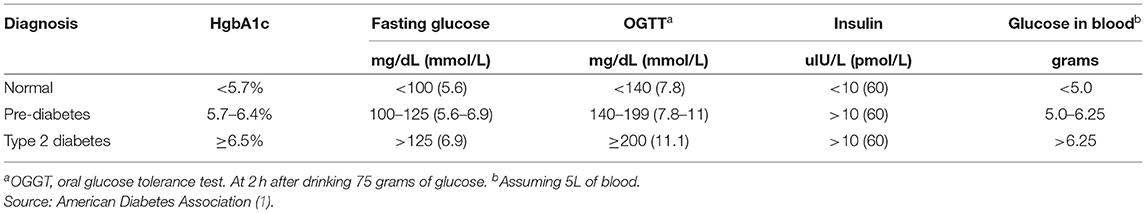

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) is characterized by chronically elevated blood glucose (hyperglycemia) and elevated blood insulin (hyperinsulinemia). When the blood glucose concentration is 100 milligrams/deciliter the bloodstream of an average adult contains about 5–10 grams of glucose. Carbohydrate-restricted diets have been used effectively to treat obesity and T2DM for over 100 years, and their effectiveness may simply be due to lowering the dietary contribution to glucose and insulin levels, which then leads to improvements in hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia. Treatments for T2DM that lead to improvements in glycemic control and reductions in blood insulin levels are sensible based on this pathophysiologic perspective. In this article, a pathophysiological argument for using carbohydrate restriction to treat T2DM will be made.

Introduction

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) is characterized by a persistently elevated blood glucose, or an elevation of blood glucose after a meal containing carbohydrate ( 1 ) ( Table 1 ). Unlike Type 1 Diabetes which is characterized by a deficiency of insulin, most individuals affected by T2DM have elevated insulin levels (fasting and/or post glucose ingestion), unless there has been beta cell failure ( 2 , 3 ). The term “insulin resistance” (IR) has been used to explain why the glucose levels remain elevated even though there is no deficiency of insulin ( 3 , 4 ). Attempts to determine the etiology of IR have involved detailed examinations of molecular and intracellular pathways, with attribution of cause to fatty acid flux, but the root cause has been elusive to experts ( 5 – 7 ).

Table 1 . Definition of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

How Much Glucose Is in the Blood?

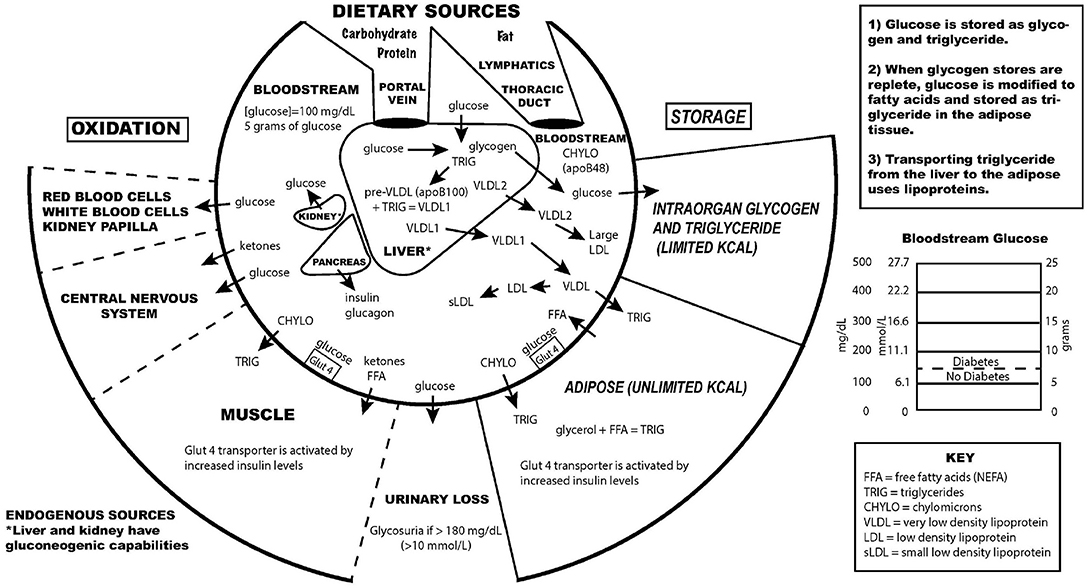

Keeping in mind that T2DM involves an elevation of blood glucose, it is important to understand how much glucose is in the blood stream to begin with, and then the factors that influence the blood glucose—both exogenous and endogenous factors. The amount of glucose in the bloodstream is carefully controlled—approximately 5–10 grams in the bloodstream at any given moment, depending upon the size of the person. To calculate this, multiply 100 milligrams/deciliter × 1 gram/1,000 milligrams × 10 deciliters/1 liter × 5 liters of blood. The “zeros cancel” and you are left with 5 grams of glucose if the individual has 5 liters of blood. Since red blood cells represent about 40% of the blood volume, and the glucose is in equilibrium, there may be an extra 40% glucose because of the red blood cell reserve ( 8 ). Adding the glucose from the serum and red blood cells totals about 5–10 grams of glucose in the entire bloodstream.

Major Exogenous Factors That Raise the Blood Glucose

Dietary carbohydrate is the major exogenous factor that raises the blood glucose. When one considers that it is common for an American in 2021 to consume 200–300 grams of carbohydrate daily, and most of this carbohydrate is digested and absorbed as glucose, the body absorbs and delivers this glucose via the bloodstream to the cells while attempting to maintain a normal blood glucose level. Thinking of it in this way, if 200–300 grams of carbohydrates is consumed in a day, the bloodstream that holds 5–10 grams of glucose and has a concentration of 100 milligrams/deciliter, is the conduit through which 200,000–300,000 milligrams (200 grams = 200,000 milligrams) passes over the course of a day.

Major Endogenous Factors That Raise the Blood Glucose

There are many endogenous contributors that raise the blood glucose. There are at least 3 different hormones that increase glucose levels: glucagon, epinephrine, and cortisol. These hormones increase glucose levels by increasing glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis ( 9 ). Without any dietary carbohydrate, the normal human body can generate sufficient glucose though the mechanism of glucagon secretion, gluconeogenesis, glycogen storage and glycogenolysis ( 10 ).

Major Exogenous Factors That Lower the Blood Glucose

A reduction in dietary carbohydrate intake can lower the blood glucose. An increase in activity or exercise usually lowers the blood glucose ( 11 ). There are many different medications, employing many mechanisms to lower the blood glucose. Medications can delay sucrose and starch absorption (alpha-glucosidase inhibitors), slow gastric emptying (GLP-1 agonists, DPP-4 inhibitors) enhance insulin secretion (sulfonylureas, meglitinides, GLP-1 agonists, DPP-4 inhibitors), reduce gluconeogenesis (biguanides), reduce insulin resistance (biguanides, thiazolidinediones), and increase urinary glucose excretion (SGLT-2 inhibitors). The use of medications will also have possible side effects.

Major Endogenous Factors That Lower the Blood Glucose

The major endogenous mechanism to lower the blood glucose is to deliver glucose into the cells (all cells can use glucose). If the blood glucose exceeds about 180 milligrams/deciliter, then loss of glucose into the urine can occur. The blood glucose is reduced by cellular uptake using glut transporters ( 12 ). Some cells have transporters that are responsive to the presence of insulin to activate (glut4), others have transporters that do not require insulin for activation. Insulin-responsive glucose transporters in muscle cells and adipose cells lead to a reduction in glucose levels—especially after carbohydrate-containing meals ( 13 ). Exercise can increase the glucose utilization in muscle, which then increases glucose cellular uptake and reduce the blood glucose levels. During exercise, when the metabolic demands of skeletal muscle can increase more than 100-fold, and during the absorptive period (after a meal), the insulin-responsive glut4 transporters facilitate the rapid entry of glucose into muscle and adipose tissue, thereby preventing large fluctuations in blood glucose levels ( 13 ).

Which Cells Use Glucose?

Glucose can used by all cells. A limited number of cells can only use glucose, and are “glucose-dependent.” It is generally accepted that the glucose-dependent cells include red blood cells, white blood cells, and cells of the renal papilla. Red blood cells have no mitochondria for beta-oxidation, so they are dependent upon glucose and glycolysis. White blood cells require glucose for the respiratory burst when fighting infections. The cells of the inner renal medulla (papilla) are under very low oxygen tension, so therefore must predominantly use glucose and glycolysis. The low oxygen tension is a result of the countercurrent mechanism of urinary concentration ( 14 ). These glucose-dependent cells have glut transporters that do not require insulin for activation—i.e., they do not need insulin to get glucose into the cells. Some cells can use glucose and ketones, but not fatty acids. The central nervous system is believed to be able to use glucose and ketones for fuel ( 15 ). Other cells can use glucose, ketones, and fatty acids for fuel. Muscle, even cardiac muscle, functions well on fatty acids and ketones ( 16 ). Muscle cells have both non-insulin-responsive and insulin-responsive (glut4) transporters ( 12 ).

Possible Dual Role of an Insulin-Dependent Glucose-Transporter (glut4)

A common metaphor is to think of the insulin/glut transporter system as a key/lock mechanism. Common wisdom states that the purpose of insulin-responsive glut4 transporters is to facilitate glucose uptake when blood insulin levels are elevated. But, a lock serves two purposes: to let someone in and/or to keep someone out . So, one of the consequences of the insulin-responsive glut4 transporter is to keep glucose out of the muscle and adipose cells, too, when insulin levels are low. The cells that require glucose (“glucose-dependent”) do not need insulin to facilitate glucose entry into the cell (non-insulin-responsive transporters). In a teleological way, it would “make no sense” for cells that require glucose to have insulin-responsive glut4 transporters. Cells that require glucose have glut1, glut2, glut3, glut5 transporters—none of which are insulin-responsive (Back to the key/lock metaphor, it makes no sense to have a lock on a door that you want people to go through). At basal (low insulin) conditions, most glucose is used by the brain and transported by non-insulin-responsive glut1 and glut3. So, perhaps one of the functions of the insulin-responsive glucose uptake in muscle and adipose to keep glucose OUT of the these cells at basal (low insulin) conditions, so that the glucose supply can be reserved for the tissue that is glucose-dependent (blood cells, renal medulla).

What Causes IR and T2DM?

The current commonly espoused view is that “Type 2 diabetes develops when beta-cells fail to secrete sufficient insulin to keep up with demand, usually in the context of increased insulin resistance.” ( 17 ). Somehow, the beta cells have failed in the face of insulin resistance. But what causes insulin resistance? When including the possibility that the environment may be part of the problem, is it possible that IR is an adaptive (protective) response to excess glucose availability? From the perspective that carbohydrate is not an essential nutrient and the change in foods in recent years has increased the consumption of refined sugar and flour, maybe hyperinsulinemia is the cause of IR and T2DM, as cells protect themselves from excessive glucose and insulin levels.

Insulin Is Already Elevated in IR and T2DM

Clinical experience of most physicians using insulin to treat T2DM over time informs us that an escalation of insulin dose is commonly needed to achieve glycemic control (when carbohydrate is consumed). When more insulin is given to someone with IR, the IR seems to get worse and higher levels of insulin are needed. I have the clinical experience of treating many individuals affected by T2DM and de-prescribing insulin as it is no longer needed after consuming a diet without carbohydrate ( 18 ).

Diets Without Carbohydrate Reverse IR and T2DM

When dietary manipulation was the only therapy for T2DM, before medications were available, a carbohydrate-restricted diet was used to treat T2DM ( 19 – 21 ). Clinical experience of obesity medicine physicians and a growing number of recent studies have demonstrated that carbohydrate-restricted diets reverse IR and T2DM ( 18 , 22 , 23 ). Other methods to achieve caloric restriction also have these effects, like calorie-restricted diets and bariatric surgery ( 24 , 25 ). There may be many mechanisms by which these approaches may work: a reduction in glucose, a reduction in insulin, nutritional ketosis, a reduction in metabolic syndrome, or a reduction in inflammation ( 26 ). Though there may be many possible mechanisms, let's focus on an obvious one: a reduction in blood glucose. Let's assume for a moment that the excessive glucose and insulin leads to hyperinsulinemia and this is the cause of IR. On a carbohydrate-restricted diet, the reduction in blood glucose leads to a reduction in insulin. The reduction in insulin leads to a reduction in insulin resistance. The reduction in insulin leads to lipolysis. The resulting lowering of blood glucose, insulin and body weight reverses IR, T2DM, AND obesity. These clinical observations strongly suggest that hyperinsulinemia is a cause of IR and T2DM—not the other way around.

What Causes Atherosclerosis?

For many years, the metabolic syndrome has been described as a possible cause of atherosclerosis, but there are no RCTs directly targeting metabolic syndrome, and the current drug treatment focuses on LDL reduction, so its importance remains controversial. A recent paper compared the relative importance of many risk factors in the prediction of the first cardiac event in women, and the most powerful predictors were diabetes, metabolic syndrome, smoking, hypertension and BMI ( 27 ). The connection between dietary carbohydrate and fatty liver is well-described ( 28 ). The connection between fatty liver and atherosclerosis is well-described ( 29 ). It is very possible that the transport of excess glucose to the adipose tissue via lipoproteins creates the particles that cause the atherosclerotic damage (small LDL) ( Figure 1 ) ( 30 – 32 ). This entire process of dietary carbohydrate leading to fatty liver, leading to small LDL, is reversed by a diet without carbohydrate ( 26 , 33 , 34 ).

Figure 1 . Key aspects of the interconnection between glucose and lipoprotein metabolism.

Reducing dietary carbohydrate in the context of a low carbohydrate, ketogenic diet reduces hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia, IR and T2DM. In the evaluation of an individual for a glucose abnormality, measure the blood glucose and insulin levels. If the insulin level (fasting or after a glucose-containing meal) is high, do not give MORE insulin—instead, use an intervention to lower the insulin levels. Effective ways to reduce insulin resistance include lifestyle, medication, and surgical therapies ( 23 , 35 ).

The search for a single cause of a complex problem is fraught with difficulty and controversy. I am not hypothesizing that excessive dietary carbohydrate is the only cause of IR and T2DM, but that it is a cause, and quite possibly the major cause. How did such a simple explanation get overlooked? I believe it is very possible that the reductionistic search for intracellular molecular mechanisms of IR and T2DM, the emphasis on finding pharmaceutical (rather than lifestyle) treatments, the emphasis on the treatment of high total and LDL cholesterol, and the fear of eating saturated fat may have misguided a generation of researchers and clinicians from the simple answer that dietary carbohydrate, when consumed chronically in amounts that exceeds an individual's ability to metabolize them, is the most common cause of IR, T2DM and perhaps even atherosclerosis.

While there has historically been a concern about the role of saturated fat in the diet as a cause of heart disease, most nutritional experts now cite the lack of evidence implicating dietary saturated fat as the reason for lack of concern of it in the diet ( 36 ).

The concept of comparing medications that treat IR by insulin-sensitizers or by providing insulin itself was tested in the Bari-2D study ( 37 ). Presumably in the context of consuming a standard American diet, this study found no significant difference in death rates or major cardiovascular events between strategies of insulin sensitization or insulin provision.

While lifestyle modification may be ideal to prevent or cure IR and T2DM, for many people these changes are difficult to learn and/or maintain. Future research should be directed toward improving adherence to all effective lifestyle or medication treatments. Future research is also needed to assess the effect of carbohydrate restriction on primary or secondary prevention of outcomes of cardiovascular disease.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

EW receives royalties from popular diet books and is founder of a company based on low-carbohydrate diet principles (Adapt Your Life, Inc.).

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. American Diabetes Association. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes. Diabetes Care . (2016) 39 (Suppl. 1):S13–22. doi: 10.2337/dc16-S005

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Bogardus C, Lillioja S, Howard BV, Reaven G, Mott D. Relationships between insulin secretion, insulin action, and fasting plasma glucose concentration in nondiabetic and noninsulin-dependent diabetic subjects. J Clin Invest. (1984) 74:1238–46. doi: 10.1172/JCI111533

3. Reaven GM. Compensatory hyperinsulinemia and the development of an atherogenic lipoprotein profile: the price paid to maintain glucose homeostasis in insulin-resistant individuals. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. (2005) 34:49–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2004.12.001

4. DeFronzo RA, Ferrannini E. Insulin resistance. A multifaceted syndrome responsible for NIDDM, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Care. (1991) 14:173–94. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.3.173

5. Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. (2005) 365:1415–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66378-7

6. Yaribeygi H, Farrokhi FR, Butler AE, Sahebkar A. Insulin resistance: review of the underlying molecular mechanisms. J Cell Physiol. (2019) 234:8152–61. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27603

7. Shulman GI. Cellular mechanisms of insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. (2000) 106:171–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI10583

8. Guizouarn H, Allegrini B. Erythroid glucose transport in health and disease. Pflugers Arch. (2020) 472:1371–83. doi: 10.1007/s00424-020-02406-0

9. Petersen MC, Vatner DF, Shulman GI. Regulation of hepatic glucose metabolism in health and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. (2017) 13:572–87. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.80

10. Tondt J, Yancy WS, Westman EC. Application of nutrient essentiality criteria to dietary carbohydrates. Nutr Res Rev. (2020) 33:260–70. doi: 10.1017/S0954422420000050

11. Colberg SR, Hernandez MJ, Shahzad F. Blood glucose responses to type, intensity, duration, and timing of exercise. Diabetes Care. (2013) 36:e177. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0965

12. Mueckler M, Thorens B. The SLC2 (GLUT) family of membrane transporters. Mol Aspects Med. (2013) 34:121–38. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.07.001

13. Bryant NJ, Govers R, James DE. Regulated transport of the glucose transporter GLUT4. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2002) 3:267–77. doi: 10.1038/nrm782

14. Epstein FH. Oxygen and renal metabolism. Kidney Int. (1997) 51:381–5. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.50

15. Cahill GF. Fuel metabolism in starvation. Annu Rev Nutr. (2006) 26:1–22. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.26.061505.111258

16. Murashige D, Jang C, Neinast M, Edwards JJ, Cowan A, Hyman MC, et al. Comprehensive quantification of fuel use by the failing and nonfailing human heart. Science. (2020) 370:364–8. doi: 10.1126/science.abc8861

17. Skyler JS, Bakris GL, Bonifacio E, Darsow T, Eckel RH, Groop L, et al. Differentiation of diabetes by pathophysiology, natural history, and prognosis. Diabetes. (2017) 66:241–55. doi: 10.2337/db16-0806

18. Westman EC, Yancy WS, Mavropoulos JC, Marquart M, McDuffie JR. The effect of a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet versus a low-glycemic index diet on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutr Metab. (2008) 5:36. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-5-36

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Allen F. The treatment of diabetes. Boston Med Surg J. (1915) 172:241–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM191502181720702

20. Osler W, McCrae T. The Principles and Practice of Medicine . 9th ed. New York and London: Appleton & Company (1923).

21. Lennerz BS, Koutnik AP, Azova S, Wolfsdorf JI, Ludwig DS. Carbohydrate restriction for diabetes: rediscovering centuries-old wisdom. J Clin Invest. (2021) 131:e142246. doi: 10.1172/JCI142246

22. Steelman GM, Westman EC. Obesity: Evaluation and Treatment Essentials . 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group (2016). 340 p.

23. Athinarayanan SJ, Adams RN, Hallberg SJ, McKenzie AL, Bhanpuri NH, Campbell WW, et al. Long-term effects of a novel continuous remote care intervention including nutritional ketosis for the management of type 2 diabetes: a 2-year non-randomized clinical trial. Front Endocrinol. (2019) 10:348. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00348

24. Lim EL, Hollingsworth KG, Aribisala BS, Chen MJ, Mathers JC, Taylor R. Reversal of type 2 diabetes: normalisation of beta cell function in association with decreased pancreas and liver triacylglycerol. Diabetologia. (2011) 54:2506–14. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2204-7

25. Isbell JM, Tamboli RA, Hansen EN, Saliba J, Dunn JP, Phillips SE, et al. The importance of caloric restriction in the early improvements in insulin sensitivity after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Diabetes Care. (2010) 33:1438–42. doi: 10.2337/dc09-2107

26. Bhanpuri NH, Hallberg SJ, Williams PT, McKenzie AL, Ballard KD, Campbell WW, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factor responses to a type 2 diabetes care model including nutritional ketosis induced by sustained carbohydrate restriction at 1 year: an open label, non-randomized, controlled study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. (2018) 17:56. doi: 10.1186/s12933-018-0698-8

27. Dugani SB, Moorthy MV, Li C, Demler OV, Alsheikh-Ali AA, Ridker PM, et al. Association of lipid, inflammatory, and metabolic biomarkers with age at onset for incident coronary heart disease in women. JAMA Cardiol. (2021) 6:437–47. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.7073

28. Duwaerts CC, Maher JJ. Macronutrients and the adipose-liver axis in obesity and fatty liver. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2019) 7:749–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2019.02.001

29. Zhang L, She Z-G, Li H, Zhang X-J. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a metabolic burden promoting atherosclerosis. Clin Sci Lond Engl. (1979) 134:1775–99. doi: 10.1042/CS20200446

30. Horton TJ, Drougas H, Brachey A, Reed GW, Peters JC, Hill JO. Fat and carbohydrate overfeeding in humans: different effects on energy storage. Am J Clin Nutr. (1995) 62:19–29. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.1.19

31. Packard C, Caslake M, Shepherd J. The role of small, dense low density lipoprotein (LDL): a new look. Int J Cardiol. (2000) 74 (Suppl. 1):S17–22. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5273(99)00107-2

32. Borén J, Chapman MJ, Krauss RM, Packard CJ, Bentzon JF, Binder CJ, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: pathophysiological, genetic, and therapeutic insights: a consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur Heart J. (2020) 41:2313–30. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz962

33. Yancy WS, Olsen MK, Guyton JR, Bakst RP, Westman EC. A low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet versus a low-fat diet to treat obesity and hyperlipidemia: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. (2004) 140:769. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-10-200405180-00006

34. Tendler D, Lin S, Yancy WS, Mavropoulos J, Sylvestre P, Rockey DC, et al. The effect of a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a pilot study. Dig Dis Sci. (2007) 52:589–93. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9433-5

35. Pories WJ, Swanson MS, MacDonald KG, Long SB, Morris PG, Brown BM, et al. Who would have thought it? An operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult-onset diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. (1995) 222:339–50. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199509000-00011

36. Astrup A, Magkos F, Bier DM, Brenna JT, de Oliveira Otto MC, Hill JO, et al. Saturated fats and health: a reassessment and proposal for food-based recommendations: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. (2020) 76:844–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.077

37. A randomized trial of therapies for type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med . (2009) 360:2503–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805796

Keywords: type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance, pre-diabetes, carbohydrate-restricted diets, hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia

Citation: Westman EC (2021) Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Pathophysiologic Perspective. Front. Nutr. 8:707371. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.707371

Received: 09 May 2021; Accepted: 20 July 2021; Published: 10 August 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Westman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eric C. Westman, ewestman@duke.edu

This article is part of the Research Topic

Carbohydrate-restricted Nutrition and Diabetes Mellitus

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Best practice in the delivery of diabetes care in the primary care network. 2021. http://www.diabetesonthenet.com/wp-content/uploads/Diabetes-in-the-Primary-Care-Network-Structure-April-2021.pdf (accessed 14 July 2022)

Dose Adjustment For Normal Eating (DAFNE). 2020. https://dafne.nhs.uk/ (accessed 14 July 2022)

Diabetes Education and Self Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed (DESMOND). 2020. https://www.desmond.nhs.uk/ (accessed 14 July 2022)

Best practice for commissioning diabetes services: An integrated care framework. 2013. http://www.diabetes-resources-production.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/diabetes-storage/migration/pdf/best-practice-commissioning-diabetes-services-integratedcare-framework-0313.pdf (accessed 14 July 2022)

Diabetes Competency Framework. 2015. https://tinyurl.com/4y974ns8 (accessed 14 July 2022)

Improving the delivery of adult diabetes care through integration. 2016. https://tinyurl.com/b46vnppp (accessed 14 July 2022)

Annual report. 2016. https://diabetes-resources-production.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/diabetes-storage/2017-08/Annual_Report_2016.pdf (accessed 14 July 2022)

Us, diabetes and a lot of facts and stats. 2019. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/resources-s3/2019-11/facts-stats-update-oct-2019.pdf (accessed 14 July 2022)

Delivering the diabetes education and self management for ongoing and newly diagnosed (DESMOND) programme for people with newly diagnosed Type 2 diabetes: cost effectiveness analysis. 2010. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c4093

The case for diabetes population health improvement: evidence-based programming for population outcomes in diabetes. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-017-0875-223

Diabetes specialist nurses and role evolvement: a survey by Diabetes UK and ABCD of specialist diabetes services. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02716

Halfyard C, McGowan D, Whyte M Diabetes rapid access clinic: a bridge between primary and secondary care (Diabetes UK poster presentation). Diabetic Medicine. 2010; 27

Health and Social Care (HSC). DoH Diabetes Nurse Education Group, Diabetes Competency Nursing Tool. 2017. https://tinyurl.com/ycxj5hnd (accessed 14 July 2022)

Diabetes specialist nursing in the UK: the judgement call? A review of existing literature. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1002/edn.190

What Is Population Health?. 2003. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.3.366

Population health management in diabetes care: combining clinical audit, risk stratification, and multidisciplinary virtual clinics in a community setting to improve diabetes care in a geographically defined population. an integrated diabetes care pilot in the north east locality, Oxfordshire, UK. 2020. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.5177

Point-of-care testing in primary cae needs: needs and attitudes of Irish GPs, BJGP Open. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgpopen17X101229

Leading Change. The Atlas of Shared Learning. 2019. https://www.england.nhs.uk/atlas_case_study/improving-insulin-administration-in-a-community-setting/ (accessed 14 July 2022)

Prevalence and correlates of diagnosed and undiagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus and pre-diabetes in older adults: Findings from the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2015.10.015

Improving risk factor management for patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of healthcare interventions in primary care and community settings. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015135

Organisation of services for people with cardiovascular disorders in primary care: transfer to primary care or to specialist-generalist multidisciplinary teams?. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-15-158

Public Health Skills and Knowledge Framework. User guide. 2016. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/545011/Public_Health_Skills_and_Knowledge_Framework_2016_User_Guide.pdf (accessed 14 July 2022)

Improving quality of care for persons with diabetes: an overview of systematic reviews – what does the evidence tell us?. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-2-26

World Health Organisation. Global Report on Diabetes. 2016. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565257

Nurses' role in diabetes management and prevention in community care

Sinéad O'Flynn

Nurse and Nutritional Practitioner, Health 4 U, Cork, Ireland

View articles · Email Sinéad

Diabetes care—particularly in a community setting as a form of prevention and management, is a growing requirement across England and Ireland. Self-management skills are an essential part of diabetes management and nurses in the community setting are one of the first points of care to ensure this. It is therefore imperative that nurses working within these primary and community care settings have the knowledge and skills necessary to support those in the community setting to effectively manage their condition, improve their health outcomes and their quality of life. Primary care has been tasked with providing both routine and more complex diabetes care and highlights a risk of adverse outcomes if people with diabetes are transferred to general practices without adequate support. Developing an approach for effective and efficient joint collaboration for primary care and specialists to manage the population of people with diabetes under their care is vital in its prevention and management. So how can this be achieved and what resources are required? This article will discuss current research into clinical practice and pilots which can contribute to supporting a more holistic multi-disciplinary approach to diabetes management and prevention, and hence, a provision of community based services aimed at health prevention.

Diabetes is a well known condition which can result in significant morbidity and mortality. The World Health Organisation ( WHO, 2016 ) recommends sharing the care of diabetes between primary and specialist teams, using referrals through primary to secondary to tertiary care. Research clearly highlights that an early diagnosis, along with effective management of care can determine the clinical course and outcome of diabetes. Health services worldwide are finding it challenging to provide systematic, ongoing and skilled care due to a growing prevalence of diabetes ( Worswick, 2013 ). Diabetes UK (2019) report that diabetes continues to be a growing health concern, with 4.7 million people in the UK known to have this condition; this number signifies an exponential increase, having doubled over the last 20 years. Mortality rates remain high due to the macrovascular complications of the condition, with over 500 diabetics dying prematurely. It is also reported by Gillet et al (2013) that self-management is often difficult due to the rising number of older people developing diabetes who already have other conditions such as dementia and arthritis. This results in community care having to administer insulin, adding pressure to already constrained services ( Leading Change, 2019 ). Leahy et al (2015) report from The Irish LongituDinal Study on Ageing (TILDA) that type 2 diabetes is the leading cause of death and disability in Ireland, and it is well known that diabetes increases risk of heart attacks, heart failure and kidney disease, resulting in a loss of independence and early mortality. They further note that diabetes accounts for 10% expenditure in the Health Service Executive (HSE), the Irish public healthcare system. The 2015 report also highlighted diabetes being more common in men than women and that those with diabetes are more likely to be obese with low levels of physical activity and suffering with other ailments such as high cholesterol and high blood pressure. The TILDA study provided, and continues to provide, the first Irish national prevalence in diagnosed, undiagnosed and pre–diabetes in older Irish adults, shaping the future for evidence based prevention programmes.

To increase prevention of diabetes and to decrease the burden to healthcare services in the long term, leading change across the community setting is a vital component of reducing mortality and morbidity with diabetes. Health and Social Care ( HSC, 2017 ) states district/community nurses are well placed to support people living with diabetes in the community. As nurses are members of a multi-disciplinary team (MDT), they can be part of a provision of services with a management strategy of a preventative holistic approach in community nursing and primary care to effectively manage the care of diabetes. It is important that care is not solely focused on treatment and management; diabetes prevention and its integration across MDT in community settings also needs to be part of this change ( Ali et al, 2021 ). So what does the research indicate regarding nursing and the community?

Nurses role – diabetes management and prevention

The crucial role of the diabetes specialist nurses (DSNs) in the provision of good patient care and promoting self-care management cannot be underestimated. They are often the first point of contact for people newly diagnosed with diabetes, and care can be employed in a variety of settings ( Gosden et al, 2007 ). Their work in the provision of education, training and support helps achieve the MDT approach with promoting self-care in diabetes and through screening and prevention of type 2 diabetes ( James, 2011 ).

All nursing staff have an important role in the treatment, management and prevention of diabetes through the promotion of dietary and lifestyle adaptations ( Halfyard et al, 2010 ). The risk factors associated with diabetes are well-researched; these include lack of physical activity, a poor diet, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, smoking and excessive alcohol consumption. According to Murphy et al (2017) , healthcare professionals can promote the adaptation of lifestyle and dietary changes, which can often lead to the reduction of incidence rates in type 2 diabetes. While type 1 diabetes cannot be prevented, advice on taking steps to prevent further health conditions can help reduce the need for further care by ensuring that treatment is provided as early as detection.

Diabetes UK (2013) highlight the vital role practice nurses have as they are often the people who carry out the annual diabetes and foot checks. Practice nurses also play a clinical role in screening, maintaining and supporting people with diabetes.

This brings into discussion another very important aspect of diabetes management and risk reduction. Using equipments such as point of care testing (POCT) can play an extremely important role in diabetes prevention and management. Practice nurses and community nurses are well placed to provide this type of non-invasive fingertip testing. These tests provide instant results, meaning dietary and lifestyle advice can be offered on the spot, tailored to the individual's health needs. POCT is defined as a laboratory service using small analytical devices conducted in a patient consultation setting rather than in a traditional central laboratory, thus providing results in real time with faster decision making. This makes it a convenient test with rapidly available results, providing immediate impact for the patients, with a potential change to their care and the appropriate advice provided at the appointment consult. Laima et al (2019) state that POCT facilitates efficient clinical management, reducing patient morbidity and mortality in primary care. POCT also contributes to cost savings in an overburdened healthcare system, enhances patients' quality of life and increases patient satisfaction. The increased utilisation of POCTs in primary health care is likely to play a significant role in the future (Laima et al, 2019). When used appropriately, POCT can lead to more efficient, effective medical treatments and improved quality of medical care. The author of this article, a nurse and nutritional practitioner, utilises POCT in their healthcare service where health promotion and prevention are the main goals. POCT is expected to continue to expand, changing the way healthcare is delivered, meaning more patient-driven and focused care (Laima et al, 2019).

Leading Change (2019) reports another area which proved successful in diabetes management in the community. They reported a previous audit by specialist diabetes nurses resulting in a modular training programme being developed to upskill both community nurses and non-registered practitioners in diabetes care. The programme was supported by the Department of Health's Knowledge and Skills Framework (2016) and by the Diabetes National Workforce Competence Framework (2015) . It provided classroom teaching with written and oral competency assessments consisting of three modules: 1) diabetes awareness 2) expansion of diabetes knowledge and 3) insulin administration for a non-registered practitioner.

Another area explored through research and which needs further evidence of the outcomes, is a population health approach ( Kindig and Stoddart, 2003 ). A population health approach has the potential to improve the quality of care of individuals by introducing solutions targeting groups and sub-groups at risk of developing complications from diabetes ( Golden et al, 2017 ). Golden et al (2017) state this approach is a whole system effort which can systematically identify, reach and improve care for all individual patients from groups which are identified as being at risk of poor outcomes. Golden et al (2017) highlight that the steps in the process involve measuring health status of a defined group of people and the distribution of health outcomes within each group. Identifying determinants of health then occurs, with designing and implementing of interventions occurring after and lastly, measuring their effectiveness.

Research recognises that good diabetes care pathways address the needs of the local service and is underpinned by a multidisciplinary team. Koslowska et al's (2020) pilot of virtual clinics in diabetes care highlighted that MDT virtual clinics in the community are one of the options for joint collaboration with primary care staff being supported by the specialist team. They argue that virtual clinics are associated with improved outcomes and show a positive impact on care processes following the success of their pilot study on a population health approach in diabetes care. The pilot enabled the service to discuss the outcomes of audit, taking into consideration the characteristics of the population and plan for improvement, proactively identify groups of patients at risk of complications from diabetes, and then plan their care together. They also reported that unnecessary referrals were avoided by the encouragement of shared responsibility and decision making for changes in treatment.

Other areas where resources for diabetes help to shape diabetes care within the community are resources provided by Diabetes UK such as DAFNE (2020) -a working collaborative of 75 diabetes services across the UK and Ireland, which is an intensive insulin therapy for type 1 diabetes. Another example of care pathways is DESMOND (2020) – a group of self-management education models and toolkits for the management of type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes UK (2013) state how planning and organising for the future has never been more important. With an ageing population compounded by people having increasingly complex health and social needs, the NHS and the Health Service Executive (HSE - the Irish public healthcare service) face financial and workforce challenges. Considering the current restraints in healthcare environments, Kozlowska's (2020) recommendations on care management-requiring a coordinated MDT approach, with a focus on effective early care in primary and community settings to reduce pressure on acute services (and reduce the onset of diabetes complications) is more important than ever. Price et al (2014) report that collaborative working is fundamental to the delivery of diabetes care in primary care networks and a multidisciplinary approach is essential to ensuring all core elements of care are met. Primary care has historically struggled with insufficient staffing and capacity to meet rising patient demands and complexity. Utilising POCT for prevention of diabetes, education programmes for HCP's and a population health approach are all areas reporting the success of diabetes management and prevention and are areas which need to be further developed and implemented.

Self-Management of Type 2 Diabetes Comprehensive Nursing Essay Example

- Rachel R.N. R.N.

- October 14, 2023

- Samples for MSN students

Introduction

Individuals with type 2 diabetes require proper disease management that includes control of their blood sugar levels, adopting healthy eating, exercises, medication, or insulin. Many people can effectively manage type 2 diabetes with adequate resources and support. If the condition is not properly managed, it can affect other body organs, leading to complications like bacterial and fungal infections and skin problems. Worst case scenario, lack of proper management increase patient mortality rates. Conducting a needs assessment is critical to help an organization identify gaps that prevent it from achieving the desired goals, in this case, proper type 2 diabetes self-management. The gaps can exist in the organization’s knowledge, practices, or skills regarding the problem. The assessment helps the organization determine effective strategies and interventions to accomplish its objectives. The purpose of this paper is to identify an organizational gap and associate interventions that can help fill the gap for better patient outcomes. The paper includes a practice gap description, a summary of the organizational needs, and the development of the practice question (PICOT).(Self-Management of Type 2 Diabetes Comprehensive Nursing Essay Example)

The problem affects the endocrinology unit that specializes in treating patients with diabetes. The endocrinologists working in the unit are the key stakeholders responsible for informing and advising major decisions regarding diabetes. The hospital leaders and administrators are also responsible for making major decisions to address the gap identified and support intervention implementation through resource mobilization. The problem identified is self-management among the rising number of type 2 diabetes patients(Self-Management of Type 2 Diabetes Comprehensive Nursing Essay Example). Limited access to diabetes self-management education at the hospital affects the patients’ ability to manage their condition effectively. The endocrinologists are responsible for treating people with diabetes and are directly affected by the identified problem. They understand what is best for their patients, and the needs assessment informs the need for diabetes self-management education (DSME/S). The leadership and administration are responsible for supporting the recommended interventions, and their decisions directly impact the unit’s efficiency in addressing the gap.(Self-Management of Type 2 Diabetes Comprehensive Nursing Essay Example)

Practice Gap

The identified gap is the lack of proper practice guidelines that support type 2 diabetes self-managemen t at the practice site. Specifically, the needs assessment identified a lack of diabetes self-management education to guide the patient in managing their condition. Many barriers prevent the implementation of a proper patient education platform or means, including limited funding and staff members, workload and time pressures, patients’ access issues, and uncoordinated relationships and communication with other specialist teams. (Self-Management of Type 2 Diabetes Comprehensive Nursing Essay Example)The lack of education means patients have inadequate knowledge and behavioral guidelines and support to manage their condition. DSME/S is crucial as it helps and motivates patients to adjust to lifestyles after diagnoses and during the treatment process. The identified intervention is face-to-face and telephone-based family-oriented education in type 2 diabetes management (Hemmati et al., 2017). The use of mhealth mobile applications is also an intervention that can help patients live healthily by sending patients adherence and treatment guidelines through messages (Boels et al., 2019). However, the hospital lacks practice guidelines for mobile applications used in type 2 diabetes management. The rising number of type 2 diabetes patients requires more effort from the care team to educate the patients to adhere to treatment and management guidelines. (Self-Management of Type 2 Diabetes Comprehensive Nursing Essay Example)

Practice Question

For patients with type 2 diabetes, does the implementation of face-to-face and telephone-based family-oriented education and mhealth mobile applications compared to written patient education materials improve self-management of type 2 diabetes among patients after diagnosis and during the treatment period?(Self-Management of Type 2 Diabetes Comprehensive Nursing Essay Example)

The purpose of the paper was to identify a research gap in the practice site and appropriate interventions to address it. The problem identified affects the endocrinology unit that specializes in treating people with diabetes. The unit presents a lack of clinical guidelines in the implementation of diabetes self-management education initiatives like mhealth mobile applications or face-to-face and telephone-based family-oriented education. Effective communication competencies help support patient education because it is essential to deliver information quickly and accurately to bolster patient understanding. Effective communication also allows DNP-prepared nurses to collaborate with other staff members and understand the patients’ concerns to address them appropriately for better patient outcomes(Self-Management of Type 2 Diabetes Comprehensive Nursing Essay Example)

Boels, A. M., Vos, R. C., Dijkhorst-Oei, L. T., & Rutten, G. E. (2019). Effectiveness of diabetes self-management education and support via a smartphone application in insulin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes: Results of a randomized controlled trial (TRIGGER study). BMJ Open Diabetes Research and Care, 7(1), e000981(Self-Management of Type 2 Diabetes Comprehensive Nursing Essay Example)

Hemmati Maslakpak, M., Razmara, S., & Niazkhani, Z. (2017). Effects of Face-to-Face and Telephone-Based Family-Oriented Education on Self-Care Behavior and Patient Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of diabetes research, 2017, 8404328. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/8404328(Self-Management of Type 2 Diabetes Comprehensive Nursing Essay Example)

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

Working On an Assignment With Similar Concepts Or Instructions?

A Page will cost you $12, however, this varies with your deadline.

We have a team of expert nursing writers ready to help with your nursing assignments. They will save you time, and improve your grades.

Whatever your goals are, expect plagiarism-free works, on-time delivery, and 24/7 support from us.

Here is your 15% off to get started. Simply:

- Place your order ( Place Order )

- Click on Enter Promo Code after adding your instructions

- Insert your code – Get20

All the Best,

Get A 100% Plagiarism-Free Nursing Paper

Related samples.

- Medical Safety Competency Comprehensive Nursing Essay Example

- Descriptive Analytics in Organizations Comprehensive Solved Nursing Essay Example

- Interventions in the Management of Elderly Persons Comprehensive Solved Nursing Essay Example

- Final Care Coordination Plan Comprehensive Solved Nursing Essay Example

- Developmental Assessment and the School-Aged Child Comprehensive Solved Nursing Essay Example

Nursing Topics

- Academic Writing Guides

- Advanced Cardiac Care Nursing

- Advanced Community Health Nursing

- Advanced Critical Care Nursing

- Advanced Health Assessment

- Advanced Mental Health Nursing

- Advanced Nursing Ethics

- Advanced Nursing Informatics

- Advanced Occupational Health Nursing

- Advanced Pathophysiology

- Advanced Pediatric Nursing

- Advanced Pharmacology

- Gerontological Nursing

- Healthcare Policy and Advocacy

- Healthcare Quality Improvement

- Nurse Practitioner

- Nursing Education and Curriculum Development

- Nursing Leadership and Management

- Nursing Research and Evidence-Based Practice

- Nursing Theories

- Nursing Topics and Ideas

- Population Health and Epidemiology

- Assignment Help

- Chamberlain University

- Grand Canyon University (GCU)

- MSN Nursing Papers Examples

- APA NURSING PAPER EXAMPLE

- capstone project

- community health nursing assignments

- comprehensive assessment

- graphic organizer

- Nursing Care Plan

- Nursing Case study

- nursing informatics assignments

- Nursing Leadership Essay

- Shadow Health

- tina jones shadow health

- Windshield Survey Examples

- Nursing Essays

- PICOT Paper Examples

- Walden University

- Women's Health Nursing

Important Links

Knowledge base, utilize our guides & services for flawless nursing papers: custom samples available.

MSNSTUDY.com helps students cope with college assignments and write papers on various topics. We deal with academic writing, creative writing, and non-word assignments.

All the materials from our website should be used with proper references. All the work should be used per the appropriate policies and applicable laws.

Our samples and other types of content are meant for research and reference purposes only. We are strongly against plagiarism and academic dishonesty.

We Accept:

Diabetes Type 2

Diabetes mellitus, normal physiology of the pancreas, case in point.

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder characterised by persistent high glucose levels in blood. The hyperglycaemia persists due to either failure of insulin production or tissues resistance to insulin (Yorek et al., 2015; Barron, 2010). Insulin is produced by the pancreas. Diabetes mellitus can subdivided into three types; type 1 diabetes mellitus, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and gestational diabetes mellitus (Habtewold, Tsega & Wale, 2016; Yorek et al., 2015; Barron, 2010). This assignment will primarily focus on a patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Type 2 diabetes results from the body failing to effectively utilize the insulin produced by the pancreas. The malfunction is referred is known as insulin resistance. The result is hyperglycaemia that is associated with the presenting symptoms of diabetes (Stoian et al., 2015; Lazo et al., 2014)

The alpha cells comprise about 20% of all the islet’s cells. They secrete the hormone named glucagon which increases blood sugar to maintain normal levels so that glucose can get broken down once sugar levels drop (Waters, 2014; TAO, 2014). The making and release of glucagon in the pancreas is controlled by chemoreceptors through the body that are sensitive to the levels of sugar in the blood. When the blood sugar levels drop too low, the chemoreceptors signal the alpha cells in the pancreas to release the hormone glucagon which is transported via blood to the liver. Glucagon acts on hepatocytes hepatocytes to break down glycogen into the glucose through a process referred to as glycogenesis (Barron, 2010; DeWit, Stromberg & Dallred, 2017).

1. Barron, J., 2010. The Endocrine System: The Pancreas & Diabetes. [Online] Available at: https://jonbarron.org/diabetes-blood-sugar-levels/endocrine-system-pancreas-diabetes. [Accessed 21 October 2016].

2. Chin, Y, Huang, T, & Hsu, BR 2013, ‘Impact of action cues, self-efficacy and perceived barriers on daily foot exam practice in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with peripheral neuropathy’, Journal of Clinical Nursing, vol. 22, no. 1/2, pp. 61-68. Available from: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04291.x. [8 February 2017].

3. DeWit, S. C., Stromberg, H., & Dallred, C. (2017). Medical-surgical nursing: Concepts & practice.

4. Habtewold, TD, Tsega, WD, & Wale, BY 2016, ‘Diabetes Mellitus in Outpatients in Debre Berhan Referral Hospital, Ethiopia’, Disease Markers, pp. 1-6. Available from: 10.1155/2016/3571368. [8 February 2017].

5. HINKLE, J. L., & CHEEVER, K. H. (2014). Brunner & Suddarth’s textbook of medical-surgical nursing.

6. Lazo, MA, Bernabé-Ortiz, A, Pinto, ME, Ticse, R, Malaga, G, Sacksteder, K, Miranda, JJ, & Gilman, RH 2014, ‘Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy in Ambulatory Patients with Type 2 Diabetes in a General Hospital in a Middle Income Country: A Cross-Sectional Study’, PLoS ONE, vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 1-5. Available from: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095403. [7 February 2017].

7. Li, G, Sun, C, Wang, Y, Liu, Y, Gang, X, Gao, Y, Li, F, Xiao, X, & Wang, G 2014, ‘A Clinical and Neuropathological Study of Chinese Patients with Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy’, PLoS ONE, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 1-5. Available from: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091772. [8 February 2017].

8. Park, H, Park, C, Quinn, L, & Fritschi, C 2015, ‘Glucose control and fatigue in type 2 diabetes: the mediating roles of diabetes symptoms and distress’, Journal of Advanced Nursing, vol. 71, no. 7, pp. 1650-1660. Available from: 10.1111/jan.12632. [8 February 2017].

9. Stoian, A, Bănescu, C, Bălaşa, RI, Moţăţăianu, A, Stoian, M, Moldovan, VG, Voidăzan, S, & Dobreanu, M 2015, ‘Influence of GSTM1, GSTT1, and GSTP1 Polymorphisms on Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Diabetic Sensorimotor Peripheral Neuropathy Risk’, Disease Markers, vol. 2015, pp. 1-10. Available from: 10.1155/2015/638693. [6 February 2017].

10. Syngle, A, Verma, I, Krishan, P, Garg, N, & Syngle, V 2014, ‘Minocycline improves peripheral and autonomic neuropathy in type 2 diabetes: MIND study’, Neurological Sciences, vol. 35, no. 7, pp. 1067-1073. Available from: 10.1007/s10072-014-1647-2. [7 February 2017].

11. TAO, Y.-X. (2014). Glucose homeostatis and the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus.

12. Won, JC, Kwon, HS, Kim, CH, Lee, JH, Park, TS, Ko, KS, & Cha, BY 2012, ‘Prevalence and clinical characteristics of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in hospital patients with Type 2 diabetes in Korea’, Diabetic Medicine: A Journal Of The British Diabetic Association, vol. 29, no. 9, pp. e290-e296. Available from: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03697.x. [8 February 2017].

13. Yorek, MS, Obrosov, A, Shevalye, H, Holmes, A, Harper, MM, Kardon, RH, & Yorek, MA 2015, ‘Effect of diet-induced obesity or type 1 or type 2 diabetes on corneal nerves and peripheral neuropathy in C57Bl/ 6J mice’, Journal of the Peripheral Nervous System, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 24-31. Available from: 10.1111/jns.12111. [6 February 2017].

- Alzheimer Disease

- Anger Management

Type 2 Diabetes: Nursing Change Project Essay

Problem statement, purpose of the change proposal, literature search strategy employed, evaluation of the literature, applicable nursing theory utilized, proposed implementation plan, potential barriers and answers.

Type 2 diabetes is a dangerous but treatable disease that manifests as high blood sugar, low insulin, and general insulin resistance. It results from living habits rather than any form of a pathogen, and people can develop it spontaneously as long as they are in a risk group. It generally does not require hospitalization unless the issue is severe, and most patients continue their daily lives. However, its symptoms are not immediately apparent to an untrained observer and can come on slowly, preventing the person from noticing. People can be trained in noticing and measuring their symptoms, but they remain fallible and can fail to see a potential cause for alarm. As such, medical workers are trying to develop more reliable and efficient methods of monitoring patients with the condition.

Most patients with diabetes live their lives with some specific accommodations that manage the condition, such as lifestyle and diet changes alongside specific medications. However, their symptoms require monitoring, and professionals are preferable to the patients for the purpose. Currently, this matter is being resolved through regular clinic visits, with specialists receiving the patients and assessing their condition. However, the procedure takes considerable time and effort on the part of both medical workers and patients. The former have to take time away from their other patients, and the latter have to travel to the clinic and wait to be assessed. With the recent advancements in technology, such an inefficient approach may be outdated and require a replacement.