I Have Depression, and I'm Proof That You Never Know the Battle Someone Is Waging Inside

Updated on 2/27/2020 at 7:50 AM

:upscale()/2018/10/29/929/n/45432864/tmp_VCwgDX_3bb255d91288b010_Screen_Shot_2018-10-29_at_3.17.42_PM.png)

I never thought I'd live to be 26 years old. You may be wondering why someone who seems perfectly healthy would have such a dark thought , and you would not be alone. But I'm proud to say that turning 26 has been one of the greatest accomplishments of my life.

If you checked my Instagram over the last few years, you would have seen me as the happiest girl in the world , traveling the globe teaching yoga and weightlifting. But keeping up that image grew exhausting, so I decided to be brave and tell my story. My story is not unique, but it's one that is rarely spoken about due to fear. Fear can be a crippling emotion, but it can also be a powerful tool.

Depression and anxiety are just like any other illness. They're nothing to hide away.

So I'm going to ask something scary: do the words "mental health" make you uncomfortable? They used to make me feel that way, too. But depression and anxiety are just like any other illness. They're nothing to hide away. In fact, these journeys should be shared and celebrated.

I have had anxiety for as long as I can remember. Growing up, it impacted every part of life. I would have panic attacks before going to school, sleepless nights before games or tests, endless thoughts of everyone being against me, and days where I felt completely alone in the world. In college, things got worse. I became extremely depressed. I partied every chance I got. I hung out with people who fed the worst parts of me. I protected myself by flashing a big smile and playing the part of the bubbly sorority girl. I told myself that depression is scary and no one wants to hear about that .

Keep it hidden and keep smiling.

:upscale()/2018/10/29/932/n/45432864/tmp_hC1CrD_42108ea0f1c0a790_IMG_6988.JPG)

A few years later, at the age of 20, my smile had fallen and I had given up. The thought of waking up the next morning was too much for me to handle. I was no longer anxious or sad; instead I felt numb, and that's when things took a turn for the worse. I called my dad, who lived across the country, and for the first time in my life, I told him everything. It was too late, though. I was not calling for help. I was calling to say goodbye.

Miraculously, he convinced me to hang on for a few more hours. Had he not boarded the very next flight to me, I would not be here right now.

That is when I started my long and continuous journey to get healthy. I worked with doctors and therapists , but I still struggled. Until one day my dad took me to a CrossFit gym by my school and for the first time I picked up a barbell. It instantly became my place to escape, my outlet, my medicine . I did not go more than a day without having a bar in my hand, but weightlifting and fitness were not enough alone.

:upscale()/2018/10/29/927/n/45432864/tmp_QrXwhp_07d866c6fba486cb_IMG_7378_2.JPG)

After a year or so, the depression crept back in. I channeled the inner strength I had built in the gym and asked for help. This is when I began working with a new therapist, one who believed that depression decreased by age 26. I have no idea if this is true, but in yoga, you're taught not to ask if the thought is true, but rather if the thought serves you. So I hung onto this. When I fell into a really bad spell, I reminded myself, "Just a few more years. Hang on until you are 26. It will get better."

I kept lifting. I kept working. I kept growing.

As an Olympic weightlifting coach and yoga teacher, people tell me all the time how strong I am, which used to make me feel like a total fraud. But today, I am 26 years old. Today, I'm proudly sharing something I felt so ashamed of for so many years , and that's because I'm strong. I have a strength that this illness will never be able to match, not at 26 or any age after that.

The charity Project Semicolon is close to my heart. The idea behind it : "a semicolon represents a sentence an author could have ended, but chose not to." My story isn't over, and each chapter is a lot brighter, a lot bolder, and filled with a lot of fun new characters. There's always more to come. We just need to continue writing.

If you or a loved one are in need of any help, the National Suicide Prevention organization has several resources and a 24/7 lifeline at 1-800-273-8255.

- Healthy Living

- Personal Essay

Marketplace

Listen live.

Fresh Air opens the window on contemporary arts and issues with guests from worlds as diverse as literature and economics. Terry Gross hosts this multi-award-winning daily interview and features program.

- Behavioral Health

- Home & Family

- Mental Health

This is what depression feels like

- Courtenay Harris Bond

(Courtesy of Courtenay Harris Bond)

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

Brought to you by Speak Easy

Thoughtful essays, commentaries, and opinions on current events, ideas, and life in the Philadelphia region.

You may also like

Shedding Light on Depression and Stigma

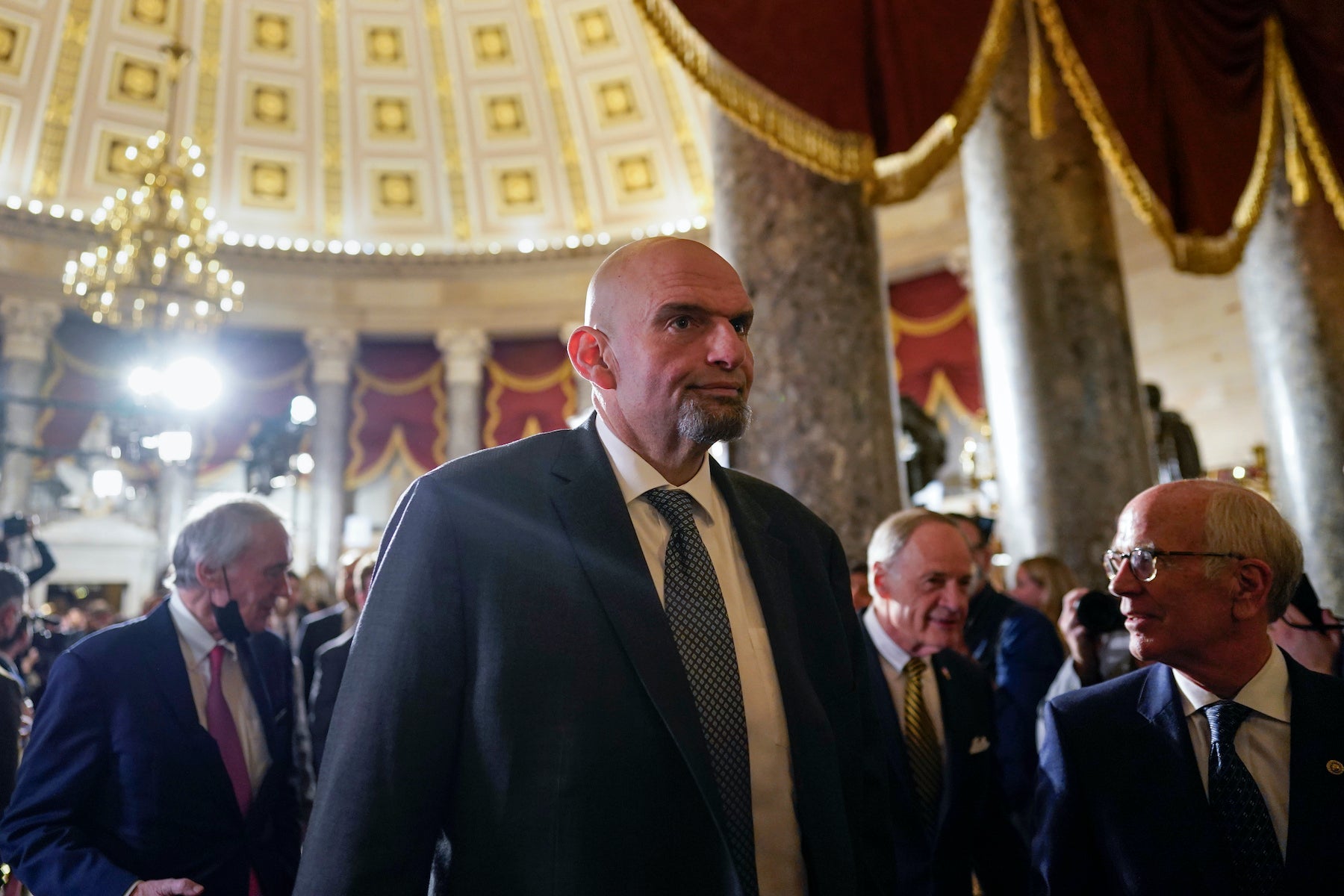

Will Senator John Fetterman's openness about his depression help remove some of the stigma around mental illness?

Air Date: February 24, 2023 12:00 pm

Fetterman case highlights common stroke, depression link

Experts say depression occurs after a stroke in about 1 in 3 patients. There may be a biological reason, with some evidence suggesting that strokes might cause brain changes.

Psychedelics and mental health: the potential, risks and hype

There's a lot of excitement around using psychedelic drugs for mental health treatment. This hour, the potential, risks and hype around psychedelics and mental health care.

Air Date: September 21, 2022 10:00 am

About Courtenay Harris Bond

Want a digest of WHYY’s programs, events & stories? Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Together we can reach 100% of WHYY’s fiscal year goal

- Depression: Major Depression & Unipolar Varieties

A Personal Story of Living through Depression

John Folk-Williams has lived with major depressive disorder since boyhood and finally achieved full recovery just a few years ago. As a survivor of ...Read More

A recovery story is a messy thing. It has dozens of beginnings and no final ending. Most of the conflict and drama is internal, and there’s a lot more inaction than action. The lead character hides in the shadows much of the time, so you can’t even see what’s going on.

I joined up with depression around the age of 8. There are snapshots of me in the shabby brown jacket I liked to wear. My mom took beautiful photographs, and there are lots of me in moody shadows, looking as down as could be.

She had her own depression to worry about. My typical memory of her from that time brings back a couch-bound, often napping, mother. She explained her sleep problem as a condition she called knockophasia – a term I’ve never been able to find in any dictionary. A few minutes after lying down, snap! Sound asleep. No one mentioned strange emotional problems or mental illness in those days. My parents occasionally talked about someone having a nervous breakdown as if they had died. There was no hint of a need to get help for my mother, much less for me. No one worried about me since I was a star in school, self-contained and impressive to teachers for being so mature, so adult.

Free Online Depression Test

Migraine headaches started then, and increasingly intense anxiety about school. I missed many days, felt shame as if I were faking, and obsessed over every one of my failings. I spent long hours alone in my room.

Therapists are Standing By to Treat Your Depression, Anxiety or Other Mental Health Needs

Explore Your Options Today

Through my teenage years, depression went underground. Feelings were dangerous. There were too many angry and violent ones shaking the house for me to add to them. So I kept emotion under wraps, even more so than in childhood. Nothing phased me outside the house and even at home I showed almost no sign of reaction to anything, even while churning with fear and anguish.

It was in my 20s that I broke open, and streams of depression, fear, panic, obsessive love and anger flowed out. In response to a panic attack that lasted for a week, I saw a psychiatrist. In one marathon session of 3 hours he helped me put the panic together with frightening episodes from my family life. I was cured on the spot but never went back to him. It was too soon to do any more.

It took another crisis a few years later to get me back to a psychiatrist and my first experience with medication – Elavil. But I had no idea what it was. I took something in the morning to get me going and something at night to help me sleep. I took it short term, got through the crisis but continued in therapy. From there I was steadily seeing psychiatrists in various cities for the next 8 years. But no one mentioned depression.

I first saw the word applied to my condition in a letter one psychiatrist wrote to the draft board during the Vietnam era. But I wasn’t treated for that problem. Therapy in those days was still in the Freudian tradition, and it was all about family life and conflict. Depression was a springboard for going deeper. Digging up the past to understand present problems was a tremendous help, and it changed me in many ways. But depression was still there in various forms, reappearing regularly for the next couple of decades. There were wonderfully happy and successful times as well, but I had these ups and downs through marriage, children and a couple of careers.

Gradually, depression became so disruptive that my wife couldn’t take it anymore and demanded I get help. So I finally did. This was the 1990s. Prozac had arrived, and I started a tour of medication over the next dozen years that didn’t do much at all. Nor did therapy, though two psychiatrists helped me to understand the more destructive patterns in my way of living.

Depression pushed into every corner of my existence, and both work and family life became more and more difficult. The medications only seemed to deaden my feelings and make me feel detached from everyone and immune to every pressure. It was like having pain signals turned off. There was no longer any sign coming from my body or brain that something might be wrong. I felt “fine” but relationships and work still went to hell.

The strange thing was that after all these years of living with it, I didn’t know very much about depression. I thought it was entirely a problem of depressed mood and loss of the energy and motivation. As things got worse, I finally started to read about it in great depth.

I was amazed to learn the full scope of depression and how pervasive it could be throughout the mind and body. I finally had a coherent, comprehensive picture of what depression was.

That was a big step because I could at last imagine the possibility of getting better. I could see that I wasn’t worthless by nature, that there were reasons my mind had trouble focusing and that the frequent slowdown in my speech and thinking was also rooted in this illness. Perhaps the right treatment could bring about fundamental changes after all.

There were still traps ahead, though. I became obsessed with the idea of depression as a brain disease. I studied all the forms of depression, the neurobiology and endless research studies. That was a good thing to do, but after awhile I was looking more at “Depression” than the details of my own version of the illness.

I wondered how many diagnostic categories I fitted into. For sure I had one or more of the anxiety disorders. Perhaps I fit into bipolar II instead of major depressive disorder. What about dissociation? I read the research study findings as if they were announcing my fate.

It was comforting to know I had a “real” disease. Not only could I answer any naysayers about the reality of depression. I also had a weapon to fight my internalized stigma, the lingering doubt that anything was wrong with me. I used to think that maybe I really was using the illness as a way to avoid life and cover up my own weakness. Here was proof that depression wasn’t all in my imagination but in my brain chemistry.

Neurobiology was far beyond my control. I couldn’t recover by myself. Doctors had to cure me through medication or other treatments, like ECT. However, that meant my hopes were pinned on them, not on my own role in getting better.

When the treatments failed to work, I got desperate that there would never be an end to depression. Hope in the future fell apart. My life would continue to run down. Could it even lead to suicide, as it had for friends of mine?

Fortunately, as I learned more, I listened to the experts who had a much broader view of the causes of the illness. Peter Kramer’s overview of research in Against Depression made it clear to me that contributors to the illness could include genetic inheritance, family history, traumatic events and stress as well as the misfiring of multiple body systems. No one could point to a single cause or boil it down to a few neurotransmitters.

So I went back to basics and looked much more closely at the particular symptoms I faced. I tracked the details in everyday living and saw that I needed to take the lead in recovery. Medication – when it had any effect at all – played a modest role in taking the edge off the worst symptoms. That bit of relief gave me the energy and presence of mind to work on the emotional and relationship impacts, to try to straighten out the parts of my life I had some control over.

I was determined to stop the waste of life in depression. I got back into psychotherapy and tried many types of self-help as well. Many didn’t work at all, but something inside pushed me to keep trying, despite setbacks.

One of the most important efforts was writing about my experience with depression. Writing is one way I discover things, but a deep fear had blocked me from doing it for years. I can see now that the real reason I got stuck was that I had been trying to write about everything but depression. When I could finally take that on directly, writing came naturally.

Blogging turned out to be the right medium. It was manageable even when I was down. The online community of people who lived with depression gave me a form of support that I had never had before. Another decisive step was getting out of high-stress work that I had been less and less able to do effectively. Taking that constant burden away restored a deep sense of vitality.

After all this, recovery finally started to happen. It took me by surprise, and for a long time I didn’t trust that it would last. But something had changed deep down. I believed in myself again, and the inner conviction of worthlessness disappeared.

I had found a deeply satisfying purpose in writing, as well as the energy and humor to do what I wanted to do. I regained the awareness and emotional presence to be a part of my family again, instead of the hidden husband and dad.

As anyone dealing with life-long depression will tell you, setbacks happen. There’s no simple happy ending. But if you’re lucky, an inner shift occurs, and the new normal is a decent life rather than depression. Self-awareness is key to good mental health. Take our online depression quiz today.

- Major And Unipolar Depression

- Related Conditions Part I

- Historical Understanding Part I

- Neurotransmitters

- When To Seek Help

- Suicidal Ideation

- Other Articles

- Classic Symptoms

- Neuroplasticity And Endocrinology

- Measuring Depression

- St. John's Wort

- Dual Diagnosis And Symptom Severity

- Understanding Mood Episodes

- Biopsychosocial Model

- Genetics And Imaging

- Questionnaires And Tests

- The Benefit Of Exercise

- How Depression Develops

- Negative Impacts Of Depression

- Diasthesis-Stress Model

- Modes Of Treatment Part I

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids

- DSM Criteria

- Psychodynamic Theories

- Behavioral Theories

- Medications

- Mood Disorder Diagnoses

- Cognitive Theory ?EUR" Aaron Beck

- B-Vitamins And Traditional Chinese Medicine

- Symptoms Of Dysthymic Disorder

- Ellis And Bandura

- Ayurveda And Homeopathy

- More Mood Disorder Diagnoses

- TCAs And MAOIs For Children

- Self-Help Methods

- Cultural Effects

- Mood Stabalizers

- Community And Online Resources

- Social And Relational Factors

- Non-pharmacological Medical Therapies

- Additional Reading

- Lifestyle And Environmental Causes

- Evidence-Based Treatment: Psychotherapy

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

- CBT Continued

- Interpersonal Therapy

- Behavior Therapy

- Psychodynamic Approach

- Group, Family And Couples Counseling

- Psychotherapy

- Self Hatred

- Antidepressants

- Blunt Instruments

- Depression & Cancer

- Heart Disease

- Maintaining Relationships

- Elusiveness Of Pleasure

- Depression In Women

- Symptoms & Causes

- A Treatable Illness

- Path To Healing

- ADHD, Psychotherapy & Medication

- Anxiety & Pets

- Setting Limits

- Dysthymic Disorder

- Elliot Smith & Vulnerability Music

- Tom Cruise Vs Brook Shields On Depression

- Symptoms Of Major Depression

- Does Male Post-Partum Depression Exist?

- National Depression Screening Day

- Older Adults

- Organizations

- Post Partum Adoption Depression

- Protracted Unemployment

- Sensory Overload

- Students & College

- Free Anti-Depressant!

- Depression, Anxiety & Morality

- The Five Senses

- Long Term Effects Of Bullying

- Physical Symptoms Of Depression

- Psychotherapy, Medication Or Both?

- Unmasking Mental Illness

- Depression & Anxiety Part 2

- Wartime Experience

- The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

- Angry All The Time

- Eating Disorder Or Overreacting?

- Classify My Mental Disorder

- OCD, Depression

- I'm Going Crazy?

- Trying To Forget

- How To Overcome Depression Caused When Boyfriend Ditched Me?

- New Boyfriend Lying About Belongings That Are His Ex Girlfriend's

- How To Help My Delusional Son?

- Is Any Of This Real?

- I Have Everything I Ever Wanted. Why Am I So Miserable?

- How Can I Convince My Suicidal MD Husband To Be Evaluated?

- Sexual Abuse, What Should I Do Now?

- Bipolar Or Depressed Or Neither?

- Feel Like Something's Wrong

- Too Much Sorrow

- Really Desperate..Please Help

- Bipolar, Depression, Grief & Anxiety

- Is This A Flashback?

- Help Us With Our Son!

- No Clue What To Do. Help?

- Am I Going Crazy?

- Do I Suffer From Depression?

- Am I Commitment-Phobic?

- I Don't Care For Anything, I Feel As Though I'm Wasting My Life.

- Anxiety Has Taken Over My Life...

- How Do I Get My 24 Year Old Son To A Counselor

- Bipolar Teen

- I Have This Issue

- Am I Depressed?

- Fear Of Choking

- In Love With A Man Who Does Not Love Me

- I Think I Have A Mental Disorder?

- Please Help Me

- OCD Or Not OCD, That's The Question

- How Can I Move Past This- A Question For Staff

- Does Romance Lead To Aggression?

- Depressed, Anxious And Dead Inside...Please Help!

- Why Do I Feel Like Everyone Is Trying To Upset Me?

- My Husbands Roller Coaster Of Proper Hygiene: Is It Depression?

- I Feel Like A Complete Waste Of A Human Life

- Am I Always Going To Feel Like This?

- Is He Changed???

- Is There Any Hope For Me, Or Am I Destined To Be Damaged?

- Falling Apart

- Helping And Watching A Friend's Recurrent Depression?

- Insanely Jealous Husband

- Can Prescription Drug Use Lead To Delusional Beharior?

- Social Anxiety, Depression And More...

- Same Views On So Much, But Can't Get Along As A Couple

- Suicidal Thoughts

- Hypothyroid 23 Year Old Girl

- It's Me Or It's My Mother?

- Is He A Narcissist?

- Help For Aging Human Service Professionals?

- If There's Nothing New, There's Nothing Good.

- Please Respond, I Need Help

- Need To Ask Someone

- Is It Okay To Give Up?

- I'm Cheated By My Girlfriend..... I Just Want To Die.....

- How Can It Help?

- Everyone Says He Is Depressed, Is He? Or Does He Really Want A Divorce??

- Help! Please!

- I Think I Need Some Help

- I Feel So Lost.

- Scared And Lonely

- Please Help Me Out

- I Never Experience Happiness

- Mystery Symptoms

- I Think I'm Depressed

- Born To Lose, Or Nurtured To Lose?

- I Am An 18 Year Old Mom Diagnosed With Severe Depression And Anxiety

- Extremely Scared: I Felt Indifferent Toward An Obsession

- Suffering With Treatment-Resistant Depression

- My Fiance May Have A Sexual, Nude Photo Addiction

- Infections And The Brain

- My Girlfriend's Family Is Ruining Our Relationship

- I Need Help And Am At The End Of My Rope

- How Can I Cope With My Husband?s Depression And Its Sexual Consequences?

- What Is The Difference Between Mental Illness And Depression?

- Do I Need Help?

- What Is It?

- Why Am I Thinking Like This?

- Why Does My Mother Hoard Everything, Including Garbage?

- Right In The Middle Of A Nervous Breakdown; What's Wrong With Me?

- Huge Disapointment With My Husband

- I Don't Really Care About Anything. What Should I Do?

- Is Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Curable?

- Is It Really A Problem?

- I Am Terrified Of Death.

- Detached: I Feel Guilty, But I Can't Help It.

- My Father, The Sociopath...

- I Feel Like A Question Mark

- Am I Not Normal!?

- Our 23 Year Old Son Refuses To Get Help For His Anxiety Attacks And Depression.

- What Is Wrong?

- Husband Abandoned Me

- D.I.D. Diagnosis, How Do I Accept This?

- I Don't Know Anymore. Please Help.

- Breaking Up With Bipolar

- Depression - Blacking Out

- My Boyfriend Saved Pictures Of His Ex-Girlfriend On His Computer.

- Restroom Phobia

- What Is Wrong With Me?

- Should I Seek Help?

- When To Leave Therapy?

- Help Me Please. What Is Going On With Me?

- I'm Afraid I'm Going Crazy

- I Don't Know What To Do

- Am I Wallowing In Depression?

- What Is Wrong With Me, Doc?

- Am I Suffering A Kind Of Psychological Problem?

- Attention Deficit And Depression

- Do I Have An Eating Disorder?

- Do You Think I Sound Depressed? I Don't Understand What Is Going On

- Is This Bi Polar?

- Depression Helps To Contribute To My Unemployment! - Paula

- Will I Ever Feel Normal?

- Cyclical Depression

- Frightening Thoughts - Fear Losing Control - Please Help!

- Anxious, Depressed, Confused, Angry....the Typical...

- Giving Up - Dad Of Three - Sep 15th 2008

- Dont Understand Me

- Exercising Violence In Dreams

- My Husband Wants To Leave Me

- Is There Help For A Person Who Has Always Been A 'little Depressed'

- Depression Treatment

- Please Help.

- Lovely, However... - Julie C. - Jul 14th 2008

- I Am Really Worried About My Mental Health (19yr Old Female)

- Do I Have Bipolar Dsorder?

- Is There Something Wrong With Me?

- Will I Ever?

- Worried About My Son

- Is There Help Out There? Lonely Mother Of Three

- Major Depressive Disorder Severe With Psychotic Features

- OCD- No Feeling

- Help!!!: Laci

- Is The Memory Of My Father Dooming My Relationship?

- Worried About Thoughts

- How Long Will I Be On Medication For Treatment Of My Depression

- My Mother Won't Go For Depression Treatment!

- Where Do I Start To Get On The Road To Recovery

- How Do I Get My Dr.s To Understand And Help Me?

- What Treatments Are Available After You've Tried The Medicines Of Last Resort?

- No One Will Help!

- A Fighting Couple

- Do I Have A Mental Health Problem?

- Whats Wrong With Me?

- Depression And Employment

- How Do You Treat Depression In Teenager Males?

- Is It Ok To Feel This Way?

- Can We Contact My Mother's Doctor?

- ADD, Tourettes Or Both?

- I Think I'm Lost?

- Don't Want To Take Meds

- Will This Ever End

- Get Supported

- Stages Of Depression

- Is There Any Help?

- Can You Help?

- Dark Fantasies

- Blood Tests

- Is It Illusion Or Truth?

- Should A Depressed Person Marry?

- Dementia And Depression

- What Type Of Exams Can Proven That A Person Has Bipolar Disorder?

- Stuck In A Mental Rut...

- Loss Of Patience

- I Can't Seem To Get Over Any Of This

- Intrusive Humiliating Memories

- Is There Some Way To Deal With Depression Without Meds?

- Losing Personality Wholness

- What Is The Point Of Life?

- No Change Is Normal Mood (e.g., Depression)

- Lack Of Personal Hygiene

- Diagnosing Depression

- Does Untreated Depression Pass On To A Fetus?

- A Request For Help

- Regular Thoughts Of Killing Myself

- How Do I Help My Depressed, Unemployed Mother

- Angry At My Doctor For Prescribing So Carelessly

- I Become Very Hostile Towards Myself

- Coming To Terms With My Own Pathetic Existence

- Do Environmental Factors Hold A Person Back?

- Tired Of This Depression

- Struggling With Feelings And Thoughts

- Greatly Depressed

- Is Depression Getting More Prevalent?

- An Empty Shell

- Helping My Husband

- Inability To Express Myself

- Non-medication Help For Depression

- Untrusting Patient

- Sick Of Feeling This Way

- Depressed And Not Dating

- Congenital Laziness

- Moody Boyfriend

- Electroconvulsive Therapy

- Frustrated And Sucked Dry

- Too Young For Meds

- Paranoid Depression

- Depressed Husband

- Self-Harming Attention Seeker

- Did My Parents Make Me Like This?

- Wild Mood Swings

- A Wonderful Man

- How Can I Become Less Depressed?

- Should I Continue With Therapy?

- Childhood Depression

- Prozac Questions

- Can I Help My Wife With Depression?

- Approaching My Tightly Wound Depressed Attorney Brother

- Brain Injury And Depression

- No Compassion For Depression

- Recurrent Depression

- Meds Don't Seem To Work So Now What?

- Pleasure-blind

- Do People Recover From Depression?

- Crying Is Behavior

- Med Consult

- Shyness And The Post Partum Blues

- The Aftermath Of Abuse

- Medicine Doesn't Work Anymore

- The First Time

- Potentially Suicidal Boyfriend

- Depressed Boyfriend

- How Do I Leave?

- Alternative Treatment

- Bereavement And Grief

- How Can I Stop Depression From Recurring?

- Depression Affects The Entire Family

- Crohn's Disorder Side Effects

- Is Paranoia A Destiny?

- Post-Drinking Depression

- Security Clearance And Depression

- Can I Inherit Depression?

- Two Clinicians

- Depressed Spouse

- Depression 101

- Controlling, Disabled Husband

- Drifting Apart?

- Drinking. . .

- Marijuana And Depression

- A Mother Struggles With Depression

- Trashed House

- Beautiful Dreamer

- Severely Depressed

- Miss Lonely

- Unhappy And In Therapy

- He Won't Tell Me Why...

- Depression Affecting My Relationship

- My Children Aren't Speaking..

- My Wife Is Depressed

- My Boyfriend Is Depressed

- Parlante Writes:

- Trying To Cope With Depression When "I Just Can't."

- Kids Grades Can Suffer When Mom Or Dad Is Depressed

- Even With Treatment, Depression Symptoms Can Linger

- Eight Little-Known Signs Of Post-Partum Depression

- 5 Strategies To Beat Caregiver Depression

- Depression And Short-Term Memory

- How To Beat Caregiver-Related Depression

- New Biochemical Research Points To Five Types Of Depression

- Postpartum Depression, Neurotransmitters, And Nutrition

- A Multidimensional Approach To Depression

- The Psychological Importance Of Gratitude And Gratefulness

- Vitamin D And Depression

- The Self-Fulfilling Prophesy: Making Expectations Come True

- Diets High In Pasta Can Increase Depression In Women

- Shedding Light On Seasonal Affective Disorder

- Psychotherapy Vs. Medication For Depression, Anxiety And Other Mental Illnesses

- Older Adults And Owning A Dog

- Are You Self-Blaming And Self-Critical?

- Is Depression Really More Common In Women?

- When Nostalgia Is A Good Thing

- Of Self-Hatred And Self-Compassion

- Depression Checklist

- The Difference Between Grief And Depression, The DSM V

- The Impact Of Small Stresses In Daily Life

- Overcoming Stress By Volunteering With Your Dog

- Can Cognitive Reserve Combat Depression As Well As Dementia?

- The Optimist Vs. The Pessimist

- Depression And Learned Helplessness

- Habituation: Why Does The Initial Excitement Always Wear Off?

- Depression And Vitamin D

- Friending And Unfriending On Facebook

- Loneliness, A Health Hazard

- The SAD Time Of Year

- The Importance Of Finding Meaning In Life: An Existential Crisis

- Does Anxiety Plus Depression Equal Depression Plus Anxiety? How Clinicians Really Think

- Therapy And Medication May Be More Effective Than Drugs Alone

- Another Reason To Save The Arts In Schools

- The Intricate Ties Between Depression And Insecurity

- Treating Alcohol And Depression

- On Being Selfish: Is It All About Me?

- What Is Boredom?

- A Personal Story Of Living Through Depression

- Be Proactive: National Depression Screening Day Is October 11

- When A Depressed Partner Falls Out Of Love

- Are Self-Hate And Prejudice Against Others Different?

- Feeling Depressed And The Importance Of Voting

- Suicide Prevention Week

- A New Form Of Self-Injury, Self-Embedding?

- Recovery From Depression And The Big Book

- Is My Depression Contagious?

- Summer Heat And Human Behavior

- The Big Picture Of Depression Symptoms

- Making Decisions When Depressed

- Understanding Resentment

- Depressed, Forgetful? Take A Walk In The Park

- Fast Food, Health And Depression

- Parental Depression And Children

- What Has Supported My Recovery From Depression?

- Olfactory Sensations (Smell) And Stress Reduction

- Health And Mental Health, Should We Screen Children?

- Turning Off The Inner Voice Of Depression: Part II

- Personality, Are You A Warm Or Cold Person?

- Turning Off The Inner Voice Of Depression: Part 1

- Of Anxiety And Depression And Play

- A Strange Question About Recovery From Depression: Why Get Well?

- Depression And Positive Vs. Negative Emotional States

- Depression And Stress At Work

- Single And Alone For The Holidays? 6 Strategies For Surviving And Even Thriving The Holidays Alone

- Resentment Vs.Forgiveness

- Beginning To Heal Through Meditation

- It's The SAD Season

- Talking With A Depressed Partner

- Depression And Marriage

- Resentment, Like Holding Onto Hot Coals

- The Strange Comfort Of Depression

- Managing A Work Life With Depression

- What Does A Depression Diagnosis Mean To You?

- Some Further Thoughts On Depression And Suicide

- Depression & Panic Disorders: Jennifer's Story

- A Discussion Of Life, Ageing And The Denial Of Death

- Depression: Justin's Story

- Creativity And Bipolar Disorder, Is There A Relationship?

- Did My Parents Care Too Much?

- Depression And The Pressure To Conform

- I Wish I Had An Illness...Mental Or Physical

- Depression And Recovering From Rape - Nicole's Story

- Video Blog: Coping With Depression

- Non Prescription Pain Medications, SSRI's And Depression

- When Life Gives You Lemons, Make Lemonade: Coping With Depression As A Result Of Economic Stress

- Postpartum Depression - Joanna's Story

- A New Cause Of Depression

- Staying Busy And Being Happy

- Treating Depression With Medication: A Philosophical Approach

- The Appearance Of A Depressed Person

- Always Predicting Disaster

- Unmasking The Deceiver...Myself

- The Pain Of Rejection By Social Groups

- Professional Sports, Stress And Depression

- No Slouching Here

- Mindfulness Therapy: Learning To Sit With Depression

- Are We Too Materialistic?

- The Holiday Season: When SAD And Grief Occur

- A Discussion Of Disappointment

- The Benefits Of Yoga

- "Breaking Up Is Hard To Do," Why?

- How To Flood Your Life With Confidence

- Living A POSITIVE LIFE With Bipolar (Manic) Depression

- Self Compassion

- Perceptions Of Life Today

- Score Another One For Cognitive Therapy

- Gauging The Effectiveness Of One Component Of Alcoholics Anonymous

- Walk To Washington: Raising Awareness About Major Depression

- Milder Depressions Don't Appear To Benefit From Antidepressant Treatment

- Staying Sober: Dealing With Temptations

- Feeling Good, It's Not Just In The Brain

- Children, ADHD And Stimulant Medication

- Brain Neuroplasticity And Treatment Resistant Depression

- Post Partum Depression And The Importance Of Sleep

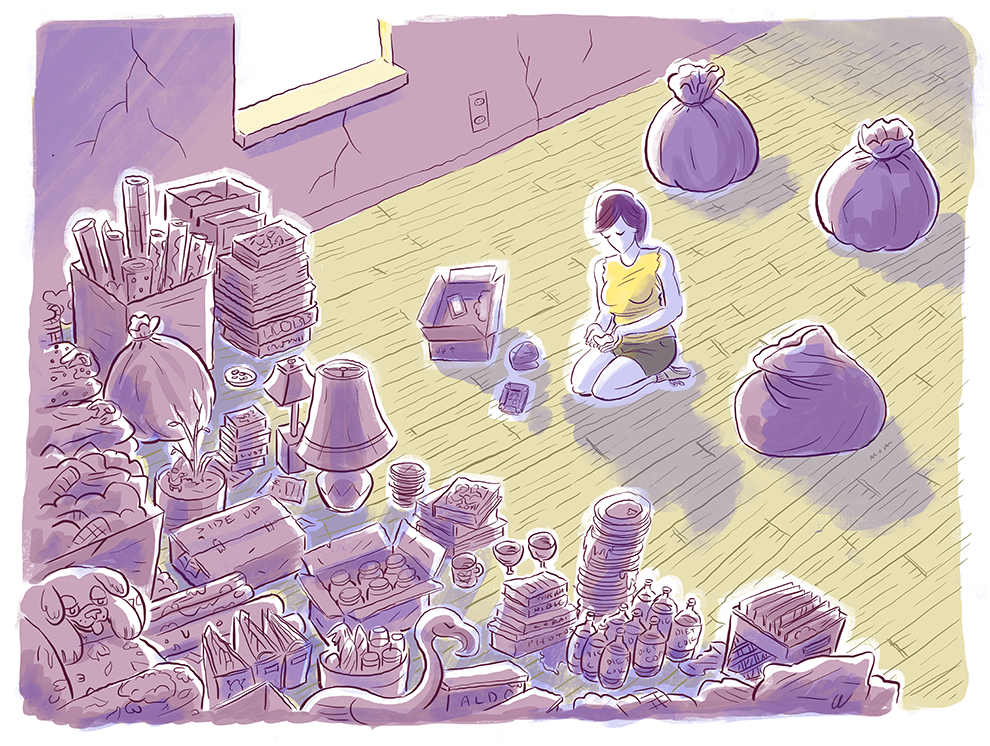

- "The Big Emptiness": Hoarding, OCD, Depression And The Quest For Meaning

- Does Psychotherapy Help Everyone?

- Of Parking Lots, Stress, Life And Psychotherapy

- Teenagers And Depression: Their Families And Psychotherapy

- Kristie Alley And The Problem Of Obesity And Dieting

- Making Friends, A Matter Of Where You Live?

- Work Place Climate, Depression And Job Searching

- Vegetarian Diets May Harbor Eating Disordered Youngsters:

- Cognitive Distortions, Also Known As

- Young Yet Sad: The Social Phobic

- Alcohol As The Cause Of Depression?

- The Importance Of Recognizing Childhood Successes At School

- Suicide: Does A Person Have The Right To Take His Own Life?

- Suspended From College For Expressing Suicidal Ideation (a Reaction To An NPR Radio Story)

- A Natural Approach To Treating Depression Web Series

- Depression And Spirituality

- National Depression Screening Day Is Just Around The Corner (October 10th!)

- Press "D" For Depression Therapy

- Few People Who Are Depressed Receive Mental Health Services

- "Guns And Suicide" Article And Comments: What About The Anger?

- World Suicide Prevention Day... September 10, 2008

- Mood Changes Linked To Seasonal Fluctuations In Serotonin

- Why Is Happiness So Difficult To Achieve? Part 1

- The Influence Of Culture On The Expression Of Depression

- Low Self Esteem: Eating Or Spending To Escape

- Depression And Diabetes: A Deadly Combination

- Mood Change Doesn't Happen Quickly

- Life: Are We Listening And Living?

- New Hope For People With Major Depression

- Depression: A New Frontier In It's Treatment

- Whisk Those Blues Away

- The Relationship Between Exercise And Mood

- Retail Therapy, Sadness And Spending: The Study Behind The Story

- I'm So Bored!

- Feeling Down During The Winter? You May Have SAD (seasonal Affective Disorder)

- Diabetes, Depression And Life

- Women And Depression

- Problems Connected With Anti Depressant Medications

- Pain And Depression

- Fibromyalgia, It Is Not Just In Your Head

- A Combination Of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy & Antidepressant Medication Works Best For Depressed Adolescents

- Dogs, Depression And Other Health Issues: Is There Something To Be Gained From Illness?

- Anti Depressants And Young People: An Issue Revisited

- Anniversary Reactions

- But, It Still Hurts: Pain-Depression-Pain

- Massive Update For Our Depression Topic Center

- Correlation: Siblings And Depression?

- Interpersonal Therapy May Prevent Future Depressive Episodes

- The Negative Effects Of Pain On Depression

- Depression And Heart Disease

- Our Bipolar Topic Center Has Been Updated

- National Depression Screening Day Is Tomorrow!

- Behavioral Therapy May Be Better Than Cognitive Therapy For Severe Depression

- Perfectionism Probably Creates A Vulnerability For Depression

- Feeling Depressed: Influenced By The Attitudes And Opinions Of Others?

- Botox Fights Depression?

- How Prozac Gets Its Groove On.

- Chronic Cortisol Exposure Causes Mood Disorders

- Heart Attacks And Young Women == Depression

- SSRI Antidepressants Raise Risk Of Premature Birth

- Adult ADHD: Difficult To Diagnose And Often Misunderstood

- NYTimes Has Story On Deep Brain Stim For Depression

- Brain Scan Predicts Who Will Benefit From Cognitive Therapy

- The Midlife Crisis: A Case Of Extreme Stress

- Treating Mother's Depression Helps Protect Their Children

- Maintanence Medications Ward Off Senior Depression Relapse

- Depression Predicts Mental Decline In Seniors

- Dad's Depression Affects Toddler's Behavior, Too

- Stress, Depression a 'Perfect Storm' of Trouble for Heart Patients

- Depression May Worsen Problem of Obesity Among the Poor

- Depression During Pregnancy Linked to Child's Asthma Risk

- Easing Depression May Boost Heart Health, Study Finds

- Risk of Violent Crime Rises With Depression, Study Finds

- Narcotic Painkiller Use Tied to Higher Risk for Depression

- Depression After Stroke Linked to Troubled Sleep

- Binge-Watching TV May Be Sign of Depression, Loneliness

- Depression, Anxiety Can Precede Memory Loss in Alzheimer's, Study Finds

- Health Tip: Is It Grief or Depression?

- 'Tis the Season for Seasonal Affective Disorder

- Mother's Depression Tied to Later Delinquency in Kids

- Nearly 1 in 12 Americans Struggles With Depression, Study Finds

- Early Puberty Linked to Increased Risk of Depression in Teens

- Being the Boss Tied to Depression Risk for Women, But Not Men

- After Breast Cancer, Depression Risk Lingers

- Even Depression May Not Dim Thoughts of Bright Future

- Dark Days Here for Folks With Seasonal Depression

- Depression After Heart Attack May Be More Common for Women

- More Evidence That Exercise May Help Fight Depression

- Obesity and Depression Often Twin Ills, Study Finds

- Teen Girls May Face Greater Risk of Depression

- Weight-Loss Surgery May Not Always Help With Depression

- Nature Walks With Others May Keep Depression at Bay

- One Dose of Antidepressant Changes Brain Connections, Study Says

- Blood Test Spots Adult Depression: Study

- Study Questions Link Between Antidepressants, Miscarriage

- Study: Young Adults Who Had Depression Have 'Hyper-Connected' Brain Networks

- Do Antidepressants in Pregnancy Raise Risks for Mental Woes in Kids?

- Talk Therapy Plus Meds May Be Best for Severe Depression

- Robin Williams' Death Shines Light on Depression, Substance Abuse

- Fitness May Help Ward Off Depression in Girls

- Coaching May Help Diabetics Battle Depression, Disease Better

- Preschoolers Can Suffer From Depression, Too

- Extra Exercise Could Help Depressed Smokers Quit: Study

- Depression May Make It Harder to Beat Prostate Cancer

- Stress, Depression May Boost Stroke Risk, Study Finds

- As Antidepressant Warnings Toughened, Teen Suicide Attempts Rose: Study

- Weight Gain From Antidepressants Is Minimal, Study Suggests

- Depression Tied to Crohn's Disease Flare-Ups

- Altruism May Help Shield Teens From Depression: Study

- Higher Doses of Antidepressants Linked to Suicidal Behavior in Young Patients: Study

- Internet May Help Seniors Avoid Depression

- Study Ties Antidepressant Use in Pregnancy to Autism Risk in Boys

- Young Dads at Risk of Depressive Symptoms, Study Finds

- ICU-Related Depression Often Overlooked, Study Finds

- Depression May Be Linked to Heart Failure

- Scientists Spot Another Group of Genes That May Raise Depression Risk

- Anxiety Disorders

- Bipolar Disorder

- Information On Specific Drugs

- Pain Management

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder

- Mens Health

- What Is Addiction?

- Signs, Symptoms, & Effects Of Addiction

- What Causes Addiction?

- Mental Health, Dual-Diagnosis, & Behavioral Addictions

- Addiction Treatment

- Addiction Recovery

- Homosexuality And Bisexuality

- Internet Addiction

- Childhood Mental Disorders

- ADHD: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

- Eating Disorders

- Childhood Mental Disorders And Illnesses

- Dissociative Disorders

- Impulse Control Disorders

- Internet Addiction And Media Issues

- Intellectual Disabilities

- Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Disorders

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- Schizophrenia

- Somatic Symptom And Related Disorders

- Tourettes And Other Tic Disorders

- Physical Mental Illness Flipbook

- Suicide Rates Vector Map

- Alzheimers Disease And Other Cognitive Disorders

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

- Colds And Flu

- Crohns Disease / Irritable Bowel

- High Blood Pressure

- Memory Problems

- Men's Health

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Sleep Disorders

- Women's Health

- Anger Management

- Mindfulness

- Stress Reduction And Management

- Weight Loss

- Disabilities

- Domestic Violence And Rape

- Family & Relationship Issues

- Grief & Bereavement Issues

- Relationship Problems

- Self Esteem

- Terrorism & War

- Health Insurance

- Health Policy & Advocacy

- Health Sciences

- Mental Health Professions

- Alternative Mental Health Medicine

- Psychological Testing

- Virtual Outpatient Eating Disorder Treatment

- Child Development And Parenting: Infants

- Child Development And Parenting: Early Childhood

- Sexuality & Sexual Problems

- Homosexuality & Bisexuality

- Aging & Geriatrics

- Death & Dying

- Physical Development: Motor Development

- Vygotsky's Social Developmental Emphasis

- Bullying & Peer Abuse

- Family And Relationship Issues

- Grief And Bereavement

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

My battle with depression and the two things it taught me

I’ve spent a decade slipping in and out of depression, but thanks to the right medicine and loving people, I’m back to being me again

I t’s often said that depression isn’t about feeling sad. It’s part of it, of course, but to compare the life-sapping melancholy of depression to normal sadness is like comparing a paper cut to an amputation. Sadness is a healthy part of every life. Depression progressively eats away your whole being from the inside. It’s with you when you wake up in the morning, telling you there’s nothing or anyone to get up for. It’s with you when the phone rings and you’re too frightened to answer it.

It’s with you when you look into the eyes of those you love, and your eyes prick with tears as you try, and fail, to remember how to love them. It’s with you as you search within for those now eroded things that once made you who you were: your interests, your creativity, your inquisitiveness, your humour, your warmth. And it’s with you as you wake terrified from each nightmare and pace the house, thinking frantically of how you can escape your poisoned life; escape the embrace of the demon that is eating away your mind like a slow drip of acid.

And always, the biggest stigma comes from yourself. You blame yourself for the illness that you can only dimly see.

So why was I depressed? The simple answer is that I don’t know. There was no single factor or trigger that plunged me into it. I’ve turned over many possibilities in my mind. But the best I can conclude is that depression can happen to anyone. I thought I was strong enough to resist it, but I was wrong. That attitude probably explains why I suffered such a serious episode – I resisted seeking help until it was nearly too late.

Let me take you back to 1996. I’d just begun my final year at university and had recently visited my doctor to complain of feeling low. He immediately put me on an antidepressant, and I got down to the business of getting my degree. The pills took a few weeks to work, but the effects were remarkable. Too remarkable. About six weeks in I was leaping from my bed each morning with a vigour and enthusiasm I had never experienced, at least not since early childhood. I started churning out first-class essays and my mind began to make connections with an ease that it had never done before.

The only problem was that the drug did much more. It broke down any fragile sense I had of social appropriateness. I’d frequently say ridiculous and painful things to people I had no right to say them to. So, after a few months, I decided to stop the pills. I ended them abruptly, not realising how foolish that was – and spent a week or two experiencing brain zaps and vertigo. But it was worth it. I still felt good, my mind was still productive, and I regained my sense of social niceties and appropriate behaviour.

I had hoped that was my last brush with mental health problems, but it was not to be.

On reflection, I realise I have spent over a decade dipping in and out of minor bouts of depression – each one slightly worse than the last.

Last spring I was in the grip of depression again. I couldn’t work effectively. I couldn’t earn the income I needed. I began retreating to the safety of my bed – using sleep to escape myself and my exhausted and joyless existence.

So I returned to the doctor and told her about it. It was warm, and I was wearing a cardigan. “I think we should test your thyroid,” she said. “But an antidepressant might help in the meantime.” And here I realised, for all my distaste for the stigmatisation of mental illness, that I stigmatised it in myself. I found myself hoping my thyroid was bust. Tell someone your thyroid’s not working, and they’ll understand and happily wait for you to recover. Tell them you’re depressed, and they might think you’re weak, or lazy, or making it up. I really wanted it to be my thyroid. But, of course, when the blood test came back, it wasn’t. I was depressed.

So I took the antidepressant. And it worked. To begin with. A month into the course, the poisonous cloud began to lift and I even felt my creativity and urge to write begin to return for the first time in years. Not great literature, but fun to write and enjoyed by my friends on social media. And tellingly, my wife said: “You’re becoming more like the person I first met.”

It was a turning point. The drug had given me objectivity about my illness, made me view it for what it was. This was when I realised I had been going through cycles of depression for years. It was a process of gradual erosion, almost impossible to spot while you were experiencing it. But the effects of the drug didn’t last. By September I was both deeply depressed and increasingly angry, behaving erratically and feeling endlessly paranoid.

My wife threatened to frog march me back to the doctor, so I made an appointment and was given another drug. The effects have been miraculous. Nearly two months in and I can feel the old me re-emerging. My engagement and interest is flooding back. I’m back at work and I’m producing copy my clients really love. Only eight weeks ago, the very idea that I would be sitting at home tapping out a blog post of this length on my phone would have made me grunt derisively. But that is what has happened, and I am truly grateful to all those who love and care for me for pushing me along to this stage.

And now, I need to get back to work. Depression may start for no definable reason, but it leaves a growing trail of problems in its wake. The more ill I got, the less work I could do, the more savings I spent and the larger the piles of unpaid bills became. But now I can start to tackle these things.

If you still attach stigma to people with mental illness, please remember two things. One, it could easily happen to you. And two, no one stigmatises their illness more than the people who suffer from it. Reach out to them.

- Mental health

Most viewed

Essays About Depression: Top 8 Examples Plus Prompts

Many people deal with mental health issues throughout their lives; if you are writing essays about depression, you can read essay examples to get started.

An occasional feeling of sadness is something that everyone experiences from time to time. Still, a persistent loss of interest, depressed mood, changes in energy levels, and sleeping problems can indicate mental illness. Thankfully, antidepressant medications, therapy, and other types of treatment can be largely helpful for people living with depression.

People suffering from depression or other mood disorders must work closely with a mental health professional to get the support they need to recover. While family members and other loved ones can help move forward after a depressive episode, it’s also important that people who have suffered from major depressive disorder work with a medical professional to get treatment for both the mental and physical problems that can accompany depression.

If you are writing an essay about depression, here are 8 essay examples to help you write an insightful essay. For help with your essays, check out our round-up of the best essay checkers .

- 1. My Best Friend Saved Me When I Attempted Suicide, But I Didn’t Save Her by Drusilla Moorhouse

- 2. How can I complain? by James Blake

- 3. What it’s like living with depression: A personal essay by Nadine Dirks

- 4. I Have Depression, and I’m Proof that You Never Know the Battle Someone is Waging Inside by Jac Gochoco

- 5. Essay: How I Survived Depression by Cameron Stout

- 6. I Can’t Get Out of My Sweat Pants: An Essay on Depression by Marisa McPeck-Stringham

- 7. This is what depression feels like by Courtenay Harris Bond

8. Opening Up About My Struggle with Recurring Depression by Nora Super

1. what is depression, 2. how is depression diagnosed, 3. causes of depression, 4. different types of depression, 5. who is at risk of depression, 6. can social media cause depression, 7. can anyone experience depression, the final word on essays about depression, is depression common, what are the most effective treatments for depression, top 8 examples, 1. my best friend saved me when i attempted suicide, but i didn’t save her by drusilla moorhouse.

“Just three months earlier, I had been a patient in another medical facility: a mental hospital. My best friend, Denise, had killed herself on Christmas, and days after the funeral, I told my mom that I wanted to die. I couldn’t forgive myself for the role I’d played in Denise’s death: Not only did I fail to save her, but I’m fairly certain I gave her the idea.”

Moorhouse makes painstaking personal confessions throughout this essay on depression, taking the reader along on the roller coaster of ups and downs that come with suicide attempts, dealing with the death of a loved one, and the difficulty of making it through major depressive disorder.

2. How can I complain? by James Blake

“I wanted people to know how I felt, but I didn’t have the vocabulary to tell them. I have gone into a bit of detail here not to make anyone feel sorry for me but to show how a privileged, relatively rich-and-famous-enough-for-zero-pity white man could become depressed against all societal expectations and allowances. If I can be writing this, clearly it isn’t only oppression that causes depression; for me it was largely repression.”

Musician James Blake shares his experience with depression and talks about his struggles with trying to grow up while dealing with existential crises just as he began to hit the peak of his fame. Blake talks about how he experienced guilt and shame around the idea that he had it all on the outside—and so many people deal with issues that he felt were larger than his.

3. What it’s like living with depression: A personal essay by Nadine Dirks

“In my early adulthood, I started to feel withdrawn, down, unmotivated, and constantly sad. What initially seemed like an off-day turned into weeks of painful feelings that seemed they would never let up. It was difficult to enjoy life with other people my age. Depression made typical, everyday tasks—like brushing my teeth—seem monumental. It felt like an invisible chain, keeping me in bed.”

Dirks shares her experience with depression and the struggle she faced to find treatment for mental health issues as a Black woman. Dirks discusses how even though she knew something about her mental health wasn’t quite right, she still struggled to get the diagnosis she needed to move forward and receive proper medical and psychological care.

4. I Have Depression, and I’m Proof that You Never Know the Battle Someone is Waging Inside by Jac Gochoco

“A few years later, at the age of 20, my smile had fallen, and I had given up. The thought of waking up the next morning was too much for me to handle. I was no longer anxious or sad; instead, I felt numb, and that’s when things took a turn for the worse. I called my dad, who lived across the country, and for the first time in my life, I told him everything. It was too late, though. I was not calling for help. I was calling to say goodbye.”

Gochoco describes the war that so many people with depression go through—trying to put on a brave face and a positive public persona while battling demons on the inside. The Olympic weightlifting coach and yoga instructor now work to share the importance of mental health with others.

5. Essay: How I Survived Depression by Cameron Stout

“In 1993, I saw a psychiatrist who prescribed an antidepressant. Within two months, the medication slowly gained traction. As the gray sludge of sadness and apathy washed away, I emerged from a spiral of impending tragedy. I helped raise two wonderful children, built a successful securities-litigation practice, and became an accomplished cyclist. I began to take my mental wellness for granted. “

Princeton alum Cameron Stout shared his experience with depression with his fellow Tigers in Princeton’s alumni magazine, proving that even the most brilliant and successful among us can be rendered powerless by a chemical imbalance. Stout shares his experience with treatment and how working with mental health professionals helped him to come out on the other side of depression.

6. I Can’t Get Out of My Sweat Pants: An Essay on Depression by Marisa McPeck-Stringham

“Sometimes, when the depression got really bad in junior high, I would come straight home from school and change into my pajamas. My dad caught on, and he said something to me at dinner time about being in my pajamas several days in a row way before bedtime. I learned it was better not to change into my pajamas until bedtime. People who are depressed like to hide their problematic behaviors because they are so ashamed of the way they feel. I was very ashamed and yet I didn’t have the words or life experience to voice what I was going through.”

McPeck-Stringham discusses her experience with depression and an eating disorder at a young age; both brought on by struggles to adjust to major life changes. The author experienced depression again in her adult life, and thankfully, she was able to fight through the illness using tried-and-true methods until she regained her mental health.

7. This is what depression feels like by Courtenay Harris Bond

“The smallest tasks seem insurmountable: paying a cell phone bill, lining up a household repair. Sometimes just taking a shower or arranging a play date feels like more than I can manage. My children’s squabbles make me want to scratch the walls. I want to claw out of my own skin. I feel like the light at the end of the tunnel is a solitary candle about to blow out at any moment. At the same time, I feel like the pain will never end.”

Bond does an excellent job of helping readers understand just how difficult depression can be, even for people who have never been through the difficulty of mental illness. Bond states that no matter what people believe the cause to be—chemical imbalance, childhood issues, a combination of the two—depression can make it nearly impossible to function.

“Once again, I spiraled downward. I couldn’t get out of bed. I couldn’t work. I had thoughts of harming myself. This time, my husband urged me to start ECT much sooner in the cycle, and once again, it worked. Within a matter of weeks I was back at work, pretending nothing had happened. I kept pushing myself harder to show everyone that I was “normal.” I thought I had a pattern: I would function at a high level for many years, and then my depression would be triggered by a significant event. I thought I’d be healthy for another ten years.”

Super shares her experience with electroconvulsive therapy and how her depression recurred with a major life event despite several years of solid mental health. Thankfully, Super was able to recognize her symptoms and get help sooner rather than later.

7 Writing Prompts on Essays About Depression

When writing essays on depression, it can be challenging to think of essay ideas and questions. Here are six essay topics about depression that you can use in your essay.

Depression can be difficult to define and understand. Discuss the definition of depression, and delve into the signs, symptoms, and possible causes of this mental illness. Depression can result from trauma or personal circumstances, but it can also be a health condition due to genetics. In your essay, look at how depression can be spotted and how it can affect your day-to-day life.

Depression diagnosis can be complicated; this essay topic will be interesting as you can look at the different aspects considered in a diagnosis. While a certain lab test can be conducted, depression can also be diagnosed by a psychiatrist. Research the different ways depression can be diagnosed and discuss the benefits of receiving a diagnosis in this essay.

There are many possible causes of depression; this essay discusses how depression can occur. Possible causes of depression can include trauma, grief, anxiety disorders, and some physical health conditions. Look at each cause and discuss how they can manifest as depression.

There are many different types of depression. This essay topic will investigate each type of depression and its symptoms and causes. Depression symptoms can vary in severity, depending on what is causing it. For example, depression can be linked to medical conditions such as bipolar disorder. This is a different type of depression than depression caused by grief. Discuss the details of the different types of depression and draw comparisons and similarities between them.

Certain genetic traits, socio-economic circumstances, or age can make people more prone to experiencing symptoms of depression. Depression is becoming more and more common amongst young adults and teenagers. Discuss the different groups at risk of experiencing depression and how their circumstances contribute to this risk.

Social media poses many challenges to today’s youth, such as unrealistic beauty standards, cyber-bullying, and only seeing the “highlights” of someone’s life. Can social media cause depression in teens? Delve into the negative impacts of social media when writing this essay. You could compare the positive and negative sides of social media and discuss whether social media causes mental health issues amongst young adults and teenagers.

This essay question poses the question, “can anyone experience depression?” Although those in lower-income households may be prone to experiencing depression, can the rich and famous also experience depression? This essay discusses whether the privileged and wealthy can experience their possible causes. This is a great argumentative essay topic, discuss both sides of this question and draw a conclusion with your final thoughts.

When writing about depression, it is important to study examples of essays to make a compelling essay. You can also use your own research by conducting interviews or pulling information from other sources. As this is a sensitive topic, it is important to approach it with care; you can also write about your own experiences with mental health issues.

Tip: If writing an essay sounds like a lot of work, simplify it. Write a simple 5 paragraph essay instead.

FAQs On Essays About Depression

According to the World Health Organization, about 5% of people under 60 live with depression. The rate is slightly higher—around 6%—for people over 60. Depression can strike at any age, and it’s important that people who are experiencing symptoms of depression receive treatment, no matter their age.

Suppose you’re living with depression or are experiencing some of the symptoms of depression. In that case, it’s important to work closely with your doctor or another healthcare professional to develop a treatment plan that works for you. A combination of antidepressant medication and cognitive behavioral therapy is a good fit for many people, but this isn’t necessarily the case for everyone who suffers from depression. Be sure to check in with your doctor regularly to ensure that you’re making progress toward improving your mental health.

If you’re still stuck, check out our general resource of essay writing topics .

Amanda has an M.S.Ed degree from the University of Pennsylvania in School and Mental Health Counseling and is a National Academy of Sports Medicine Certified Personal Trainer. She has experience writing magazine articles, newspaper articles, SEO-friendly web copy, and blog posts.

View all posts

Personal Stories

We want to hear your story.

Tell us how mental illness has affected your life.

Share Your Story

Find Your Local NAMI

Call the NAMI Helpline at

800-950-6264

Or text "HelpLine" to 62640

If you or someone you know is experiencing a mental health, suicide or substance use crisis or emotional distress, reach out 24/7 to the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline (formerly known as the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline) by dialing or texting 988 or using chat services at suicidepreventionlifeline.org to connect to a trained crisis counselor. You can also get crisis text support via the Crisis Text Line by texting NAMI to 741741 .

Stigma and Living with Depression

Looking back on my life, I consider myself very fortunate. I married an amazing woman; and we have been married 25 years. We have raised two sons of whom we are very proud. I was raised in a loving, supportive home. Both of my parents were active in my childhood. I served honorably as Marine. Work in a job I enjoy and will be able to work the same job in to retirement. Have a nice home in a safe neighborhood. Have lots of friends and many of my family live nearby.

You hear this and may be thinking “What does he have to complain about?” And you may be right. But I also have a dark side that I don’t let many people see. A side I spent my life ignoring and many times waking hoping it doesn’t surface. It’s a side me I spent a lot of time embarrassed by it. That side of me has a name. Depression.

Those who know me usually never know I suffer depression. I have two sides. The outer self. That is the one most people see. Most of the time, I am able to show that I’m content, joyful, and entertaining; but it takes a lot of energy to maintain it.

The other is my inner self. It is stealthy and lurks in the shadows of my mind as an undercurrent that I seldom talked about, rarely show, or can really even explain.

Before I got a proper diagnosis, and really learned about depression, I misunderstood really what it was – and why I fought so hard to deny it. I misunderstood and thought depression meant being sad, mopey, withdrawn, and moody. Of course, I’ve been all of those things at various times, but I didn’t live like that so I can’t be depressed. However, I was completely off course. It is nothing like I thought it was.

Instead, I refused to face, and wouldn’t share the feelings and thoughts with anyone. I feared that no one would understand and would think I was attention seeking—or worse—lying. I felt I was the only one who was like this. That there was something wrong with me. I had no idea what it was, how to combat it, or what to do about it. So I ignored it.

I’ve had mental illness my whole life. There isn’t a time I can remember where it wasn’t present. It sits there like a fog. Sometimes it is merely a mist, tingling my thoughts. Other times it’s a pervasive thick, dark shroud. It’s the times when the thoughts are darkest that are most debilitating. These are the times that scare me.

It is my hope that my story will help others. Before I started writing this, I asked friends to help me on an experiment. I asked: 1) when they first met me, what was their impression; 2) And over time what do they think of me now.

The responses were overwhelming and positive:

“A stand-up gentleman who was true to his word. Enjoys being with people.” “Resilient and sarcastic.” “A man of integrity, a loyal friend to many, very thoughtful.” “Great guy with a super sense of humor.” “A great friend and excellent teacher.” “Kind, honest, and considerate.” “Principled yet funny.” “Caring and loyal friend.” “I learn and enjoy seeing the world through your eyes.”

Hearing these wonderful words, while cathartic and moving, only frustrates Depression and stokes the fires of self-doubt. The inner self is always chittering away at me. It wants to be surreptitious. It tells me everyone will see me as I really am: an emotional wreck; a procrastinator; a fraud who has managed to fool everyone.

So, instead I “tough it out” and “put on the brave face.” If I pretend it isn’t there, hopefully no one will notice. However, putting on this public persona is emotionally taxing and draining. Eventually it takes its toll. I progressively become numb; and eventually have to completely withdrawal. I stay in that state until it passes – whether a day, several days or sometimes a week.

Although, sometimes it won’t pass. It’s a feeling as though I can’t recharge my drained mental energy. It’s those times when that inner self takes completely over; and I’m filled with unceasing anxiety and utter despair. All I want to do is sleep or cry or hide. I try to fight the feelings, but I sink into depths where I can’t manage them any longer. They become relentless wave that batters me until I have nothing more to fight against it. A fear that I can never get back to being “normal” again.

Sadly, that has happened a few times, and twice with terrible consequences. Those two times I attempted suicide. Looking back, I can remember those nights vividly, and even remember what dark thoughts I had. That utterly scares me.

Yet, through all of this, a life changing event occurred that forced me to face this inner self. I started going to therapy and finally admitted I needed medical help. I explained to my doctor about my depression and anxiety and was referred to a psychiatrist. It took different medicines and adjustments until the right ones worked. When it did, it was life altering. I could finally see through the fog.

Today, that inner self pushes his way in less and less. I don’t think he’ll ever really go away. But when he does come back, I feel empowered to keep him weak with less influence. The journey has been long. But I remain hopeful and look forward to each day.

No matter the great things and accomplishments we have in life, none of those diminish the depression. It’s a pervasive illness that can strike anyone. Just remember we’re never alone. It’s not a weakness to ask for help. There are many out there who love you.

Let’s Talk About Depression: A Personal Narrative .

Trigger warning: references to depression, suicide and self-harm .

It was an exciting vacation until I woke up in the ICU in a hospital in Nasik. I was told I met with an almost fatal accident. The driver died on the spot but I did not come to know until a few months had elapsed. I underwent multiple surgeries and my head had to be tonsured. My otherwise clear face bore deep scars and stitch marks. My spleen had to be removed, which resulted in a long scar on my stomach that will neither fade nor vanish. I got the best medical care and I constantly reminded myself that it could have been worse.

For almost six months, I had family, friends and everyone visiting. But as time passed, I felt something was not right with me. I started feeling lonely and disconnected from everyone. I hated the scars and marks and felt dejected. Every time I looked at my tonsured head, my eyes would well up, despite consoling myself for not liking the way I felt and I looked. It took me a great deal of patience to accept what had happened.

But the demons in my head had already started enjoying themselves at my expense. I started getting sleepless nights. I lost interest in everything. All I wanted to do was sit in a dark room. My energy levels depleted at an alarming rate. All I wanted to do was just lie in bed and avoid any kind of contact with the outside world. I would not want to eat anything. My taste buds seemed to have died. No matter what I ate, I would feel as if my taste buds have gone numb. I no longer enjoyed eating.

The more I read about depression, the more I realised that it is treatable and can be cured with timely and effective intervention.

I started getting thoughts of suicide and self-harm. I had a strong urge to jump off from the terrace. My coping mechanism shut down. I stopped relating to anything. The worst part was the absence of feelings. I neither felt happy nor sad. I stopped aspiring. I stopped learning and growing. Initially, I thought I was being lazy. But things only started getting worse. I knew I had to take help because it was getting pretty bad and living in self-denial mode wasn’t helping me at all. I realised that mental health issues are like any other disease that can be cured with intervention. So one day I took an online test on mental health and even visited a shrink. Both spelt out DEPRESSION.

I couldn’t believe that a livewire like me could be depressed. I started questioning myself. What was I depressed about? What was bothering me and what could I do to help myself? I could not find concrete answers. The shrink put me on medication and it helped me to at least sleep at night. I have always been anti-medicine and paranoid about side effects, so I stopped it mid-way and told myself that I would deal with it myself. I started reading about depression. I started talking about depression and I realised that depression is more common than we think.

According to the World Health Organisation, “Globally, depression is the top cause of illness and disability among young and middle-aged populations. India is home to an estimated 57 million people affected by depression. Interestingly, a higher prevalence of depression among women and working-age adults (20-69 years) have been consistently reported by Indian studies.”

The more I read about depression, the more I realised that it is treatable and can be cured with timely and effective intervention. I was determined to help myself and others, especially women. I had created a Whatsapp group and I named it ‘Let’s Talk’. I had started the group before my accident. I added a few of my friends to the group and encouraged them to talk and share.

India is the country with the most depression cases in the world, according to the World Health Organisation, followed by China and the USA.

Coincidentally, Depression – Let’s Talk was the slogan for World Health Day 2017. 2017 was the darkest year for me as I was trying to get back on my feet after my accident in November 2016. I was determined to at least start talking about depression. I started telling women that talking to each other would be more helpful than talking about each other. I wanted to form a support group and help as many people as I could.

But sadly, most people live in self-denial and some of them would not take depression seriously. It was only when I talked in private to people, I realised that the monster called depression was for real and it could affect a man, woman or a child. India is the country with the most depression cases in the world, according to the World Health Organisation, followed by China and the USA. All the more reason to ACT now!

In my case, writing and talking is helpful. I have my rough days and a part of me is still to come to terms with the post-traumatic stress disorder. But I want to tell everyone that we need to be heard without judgement or criticism. I always encourage people to talk and open up as I feel that is the first step. We heal the moment we are heard.

Also Read: The Yellow Wallpaper Review: When Medical Science Failed Women

Featured image used for representational purpose only. Image source: Deviant Art

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Get Involved .

Monthly donation

As per directions from Reserve Bank of India, credit card standing instructions can't be accepted for monthly donation. Kindly share your name, contact number and email on the following form so that we can generate and share a donation link for your monthly donation.

Contact number

- Campus Culture

- High School

- Top Schools

Addressing Depression in Your Personal Statement

- college application essays

- essay topic

Did you know 20% of teenagers experience depression before reaching adulthood? It is also during this time that college applicants have to answer the most intimate question in order to gain acceptance at their dream school. What defines you?

While it may feel extremely vulnerable to talk about your experience with depression, don’t let that immediately deter you from choosing it as your personal statement essay topic. Here are 5 examples that may help you approach the topic in an essay:

UC Irvine ‘17

Throughout the past few years, I have gone through depression. The inability to focus not only in school, but also in life, is something I have struggled to overcome. The majority of the time, I am able to successfully distinguish my emotions from my academics because of my overly organized tendencies. At other times, the feelings that come with depression are inevitable. Depression, for me, is hopelessness. My biggest struggle with depression is not being able to see the light at the end of the tunnel; therefore, this way of thinking has caused me to feel unmotivated, alone, and frightened. Because of this, I have spent endless nights contemplating my life till 4 or 5 in the morning, I have no motivation to wake up in the mornings, and I feel pain and grief on a daily basis. Keep reading.

Brittanybea

Uc berkeley ‘19.

On a warm August morning I sat shivering and shaking in the waiting room to my doctor’s office. I had my mother make the appointment but didn’t give her the reason; I’m not even sure I really knew the reason. I just knew something was wrong. The past five years had been all uphill - outwardly, at least. I was doing increasingly well in school, growing more independent, and had greater opportunities at my feet. Inwardly, however, was an entirely different story. Those five years felt like an upbeat movie I was watching while in my own personal prison. I was happy for the characters, even excited for their accomplishments. The problem was that my outward self was a character entirely distinct from the internal me. View full essay.

869749923096609FB

Williams college ‘19.

Perhaps the greatest blessing my parents have ever granted me was the move from our apartment in the Bronx to a two-family home in Queens, two blocks away from a public library. The library had all the boons my young heart could desire: bounties of books, air conditioning in the summer, and sweet solace from a dwelling teeming with the cries of an infant sister, a concept I couldn’t yet fathom. Read more.

When I was younger, people chided me for being pessimistic. It was my sincere belief that there were no rewards to be reaped from a life here on earth. I was bored, unhappy, and apathetic. War, injustice, environmental collapse, the mean thing X said to me the other day-it all made me see the world as a tumultuous and unpleasant place. Continue reading.

879216135461584FB

Dish soap, pepper, a toothpick, and an empty pie tin. The first materials I ever used to perform a simple experiment in grade school. Looking back that would be the moment I fell in love with science. I can still feel the excitement I felt as I watched as the pepper dart off to the edges of the pie tin as I touched the water with the end of a soap coated toothpick. Though I didn’t have to question how or why the reaction happened, I never stopped wondering. It was then that a passion for science ignited in me. It was a fire in my soul that could never die out. However, I couldn’t have been more wrong. As I grew older, the fire within me began to dim and in the year 2012, it became extinguished; the world as I knew it had ended. View full profile.