MINI REVIEW article

Coping with students’ stress and burnout: learners’ ambiguity of tolerance.

- 1 School of Marxism, Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, China

- 2 School of Marxism, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China

In the learning milieu, academic stress is deemed as the most general mental condition that learners encounter throughout their educational process, and it has been viewed as one of the most central issues not only in general education but also specifically in language learning. Likewise, burnout has been the main point in this situation. The comprehensive sources of stress and the reasons for burnout are pinpointed in the literature so realizing their association with other aspects such as coping strategies, namely tolerance of uncertainty, are at the center of attention as it may help reduce burnout and decrease the level of stress. To this end, the goal of the present study is to prove the influence of the tolerance of ambiguity in explaining the role of stress and burnout. Briefly, some implications are set forth for the educational stakeholders.

Introduction

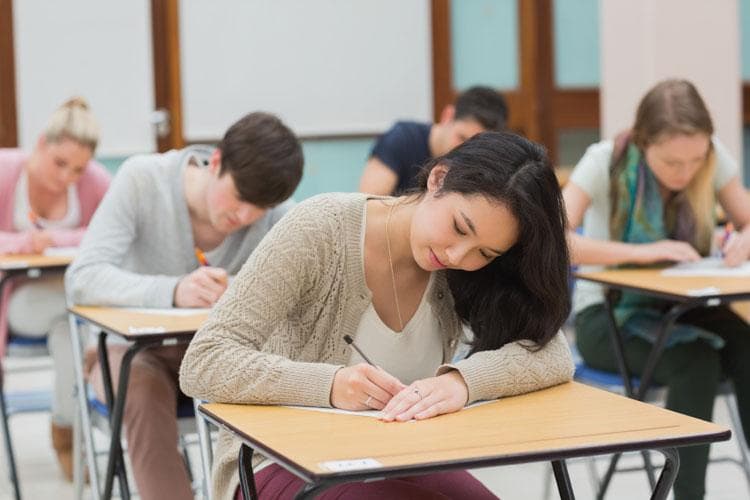

Taking into consideration today’s constantly altering cultural, social, economic, and political climate, it is expected that learners encounter high rates of stress and disclose feelings of being overwhelmed and fatigued ( Cheng et al., 2019 ). Even more important, scholastic stress is encountered because of substantial course work, hard and recurrent testing processes, high self-expectations, and the force to conduct and achieve ( Bedewy and Gabriel, 2015 ). Learners normally encounter difficulties that make the educational setting increasingly stressful when studying a new language, as numerous inquiries have shown, most learners encounter high degrees of academic stress ( Choi et al., 2019 ; Rajoo et al., 2019 ). In the educational cycle, learners with course stress, high course load, or other mental elements have low emotional exhaustion, and a low individual sense of success ( Yang, 2004 ).

In addition, dropout problems are primarily related to high scholastic stress, as they influence learners in several ways ( Kamtsios and Karagiannopoulou, 2015 ). The extent of stress that learners encounter in the foreign language educational cycle might have harmful influences on their scholastic achievement and success ( Iannello et al., 2017 ). Indeed, stress is a significant element that can influence learners’ education and success as learners studying English may encounter more language stress due to the number of mental, societal, and literary elements ( Khattak et al., 2011 ) and accordingly, burnout is also more popular among EFL learners than other learners that are the result of prolonged chronic stress that bring about issues like emotional fatigue, irritability, and physical symptoms like headaches, and intellectual impairment like memory and concentration issues ( Li, 2020 ), and this construct is associated with a variety of adverse consequences, including poor performance, mental distress, and even dropouts from school ( Bask and Salmela-Aro, 2013 ; Wang and Guan, 2020 ).

Although there is much literature on educators’ burnout in educational research, learners’ burnout has not been taken into consideration ( Robins et al., 2018 ) and it has become clear, nonetheless, that burnout is not limited to educators; rather, it can correspondingly happen to learners in foreign language settings ( Li, 2020 ). In fact, from a psychological point of view, like any other career, learners are emotionally and behaviorally involved in a variety of activities that may be considered as “work” that these activities are highly structured, mandatory (participating in class, doing homework, and taking examinations), and targeting success goals ( Schaufeli and Taris, 2005 ). Learners’ burnout is a significant element that has a profound effect on learners’ lives and education as it is a disorder that results from chronic distress or consecutive calamities of inefficacy in a particular profession or discipline ( Salanova and Llorens, 2008 ).

Moreover, a significant element in deciding scholastic achievement is the capability of dealing with life stress ( Kamtsios and Karagiannopoulou, 2015 ; Wang and Guan, 2020 ). To this end, various concepts have been associated with stress and burnout as the latest studies indicated that tolerance of ambiguity, as an emotional construct, may have a key role in adjusting and controlling stress ( Xu and Tracey, 2014 ). Tolerance of ambiguity is characterized as the propensity of a person to be unable to tolerate various responses caused by the discerned lack of prominent, important, or adequate knowledge and maintained by the associated discernment of ambiguity ( Carleton, 2016 ). A sense of ambiguity can be encountered at various phases and areas of life and language learners, for instance, may not be confident about their future objectives or career decisions. Ambiguity is overwhelming for people and can cause stress, and a deconstructive feeling, particularly for those who cannot tolerate it so those people who cannot tolerate ambiguity may regard the indispensability of life’s ambiguity as stressful ( Liao and Wei, 2011 ).

More specifically, people who do not tolerate ambiguity experience stress and anger and believe that it is deconstructive and must be prevented, and they have difficulties operating in unpredictable conditions. Unluckily, people who do not tolerate ambiguity are intolerant of numerous circumstances, as some ambiguities happen in their daily lives and the inclination to respond reconstructively to ambiguity can result in increased stress ( Buhr and Dugas, 2006 ). While individuals have the flexibility to respond to notions and convictions that differ from their own standpoints, others are more likely to decline notions that are inconsistent with their system and ambiguity of tolerance alludes to the way a person or group displays and handles information about an ambiguous circumstance when they experience a set of unknown, intricate, or inconsistent cues ( Nezhad et al., 2013 ). Even though great attention is drawn to these two concepts, stress, and burnout, based on the author’s knowledge, literature on the role of tolerance of ambiguity in the language learning domain is restricted so this study attempts to inspect the EFL learners’ tolerance of ambiguity as interpreters of stress and burnout.

A mounting response to a persistent stressor in the workplace is known as burnout that is characterized by the symptoms of emotional fatigue, depersonalization, and poor individual achievement and student burnout seem to have a grave impact on learners’ scholastic life ( Maslach and Leiter, 2016 ). A three-dimensional syndrome of emotional fatigue, cynicism, and expert efficacy is known as students’ burnout ( Schaufeli and Taris, 2005 ) as academic burnout alludes to learners’ fatigue due to high learning requirements (fatigue), distant and detached behavior toward school assignments, or educators (cynicism), and a sense of incompetence or a sense of absent success as a learner (inefficacy) that is also related to the self-assessment of unsuccessful learners in the academic context ( Zhang et al., 2007 ).

Academic Stress

Academic stress seems to be the most regular psychological condition encountered during their coaching period ( Ramli et al., 2018 ; Han, 2021 ). Stress is regularly utilized systematically to allude to a broad diversity of cycles, like life occurrences and circumstances, intellectual, emotional, and biological responses that such circumstances arouse ( Epel et al., 2018 ). Additionally, scholastic stress is a state created by the pressure of encountering scholastic difficult circumstances among learners ( Alvin, 2007 ). Moreover, it leads to the learners having an individual recognition of the inability to manage both environmental needs and learners’ actual assets. In fact, stress has a prolonged and uniform history as an element that adversely affects a learner’s scholastic background.

Tolerance of Ambiguity

In a language education setting, tolerance of ambiguity is the capability of coping with new ambiguities without feeling frustration or relying on knowledge sources; thus, learners who tolerate ambiguity are anticipated to comfortably learn a new language, despite encountering uncertainties and foreign phenomena in the structural and cultural dimensions ( Kamran, 2011 ). The absence of dependable or appropriate information is known as ambiguity that mirrors a trend of emotional responses to complexity, confounding, or unfamiliar information or occurrences ( Hillen et al., 2017 ). Poor tolerance of ambiguity can impede the creation of social connections, performance in ambiguous environments, the attainment of intricate notions and abilities, and those who are uncomfortable with an ambiguous situation may pull out of it or keep away from the same situation in the future ( Tynan, 2020 ). When learners face enormous amounts of new information or conflicts in their language classes, it can lead to strong negative emotional reactions such as stress. Ambiguity tolerance is generalized to various aspects of an individual’s emotional and cognitive functions and is characterized by cognitive style, belief, and viewpoint systems, associative and social functions, and problem-solving practices ( Furnham and Marks, 2013 ). Ambiguity of tolerance is characterized as an intellectual prejudice that influences how an individual discerns, interprets, and reacts to an ambiguous circumstance at the level of intellect, emotion, and behavior ( Dugas et al., 2004 ).

Implications and Future Directions

Learners’ stress can lead to a loss of excitement for taking part in the scholastic study. It can also jeopardize the learner’s scholastic future. Therefore, it is crucial to find ways and determine factors that assist learners to lessen their levels of stress and burnout and it is of utmost significance to enable learners to find tactics to use in the case of challenges and to cope with them in the scholastic context, which may decrease the risk of emotional stress. This minireview provides a number of implications for learners in language learning situations. Since a high degree of stress and burnout levels are both linked to diminished life fulfillment, and critical conceptions of dropping out, these regularly bring about low performance and decreased responsibility. Based on the expanding perception of Positive Psychology in language learning ( Wang et al., 2021 ), the concepts of stress and burnout may offer perceptions for educators in employing inhibition and involvement which are suited well into the learning situation focusing on tolerance of ambiguity as an effective way and strategies to counteract stress and burnout may be beneficial both for learners’ language progress, and their well-being. In this way, it can be argued that the intolerance of ambiguity is a person’s understanding of a circumstance centered on a person’s emotions ( Dugas et al., 2004 ). Tolerance of ambiguity has been accepted as a significant element in the remedy of stress and burnout so types of interventions could be premeditated and employed in an educational context to expand learners’ tolerance of ambiguity to eventually diminish the level of stress and burnout ( Shihata et al., 2016 ). Indeed, it is specifically critical to plan and employ approaches to lessen the occurrence of stress and burnout so tolerance of ambiguity, recognized as an emotional perception, can be considered as one way to deal with these problems because those learners who are exceedingly intolerant of ambiguity in case of an ambiguous incident understand the event as irritating and intolerable, while those learners who are tolerant of ambiguity consider the same phenomenon as less irritating. Learners who are more tolerant of ambiguity are more comfortable when faced with unknown cases or unpredictable in various educational circumstances. Students’ success can be affected by tolerance for ambiguity. Since everyday life is full of ambiguity, those who are intolerant of ambiguity can easily find many “reasons” to fret about ( Dugas et al., 2004 ) and learners with more tolerance of ambiguities are more likely to apply language policies to manage and regulate ambiguities ( Varasteh et al., 2016 ).

As a result of the negative impacts of stress and burnout on education, teaching staff representatives, counselors, and others who involve in learners could provide more control by inspiring learners to deal with the probable roots of their trauma, and by helping them find or design active and influential coping strategies to improve their intervention agendas. Furthermore, teachers are supposed to do a better job preparing and instructing their learners to contend with both their stress and consequently their burnout. In addition, more stress management training programs through workshops, seminars, and webinars should be held to assist students to be more relaxed and interested in the process of their education and arrange their future occupation policies and provide required support in their search of further instruction. As this study is a mini review and its purpose is not to implement intervention, ambiguity of tolerance could be regarded as a fundamental societal and emotive aptitude in further research that should be promoted in learners through some interventions with the purpose of addressing academic stress and burnout, so in this way, the results of such quantitative research can be added to the literature to confirm the consequences.

Author Contributions

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

This review was supported by Liaoning social science planning fund “Research on the political construction of the Communist Party of China in the new era,” periodical achievement of (L20BDS016).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Alvin, N. O. (2007). Handling Study Stress: Panduan Agar Anda Bisa Belajar Bersama Anak-Anak Anda. Jakarta: Elex Media Komputindo.

Google Scholar

Bask, M., and Salmela-Aro, K. (2013). Burned out to drop out: exploring the relationship between school burnout and school dropout. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 28, 511–528. doi: 10.1007/s10212-012-0126-5

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bedewy, D., and Gabriel, A. (2015). Examining perceptions of academic stress and its sources among university students: the perception of academic stress scale. Health Psychol. Open 2:2055102915596714. doi: 10.1177/2055102915596714

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Buhr, K., and Dugas, M. J. (2006). Investigating the construct validity of intolerance of uncertainty and its unique relationship with worry. J. Anxiety Disord. 20, 222–236. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.12.004

Carleton, R. N. (2016). Into the unknown: a review and synthesis of contemporary models involving uncertainty. J. Anxiety Disord. 39, 30–43. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.02.007

Cheng, M., Singh, S., Chen, P., Chen, P. Y., Liu, S., and Hsieh, C. J. (2019). Sign-opt: a query-efficient hard-label adversarial attack. arXiv [Preprint] arXiv: 1909.10773,

Choi, C., Lee, J., Yoo, M. S., and Ko, E. (2019). South Korean children’s academic achievement and subjective well-being: the mediation of academic stress and the moderation of perceived fairness of parents and teachers. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 100, 22–30.

Dugas, M. J., Buhr, K., and Ladouceur, R. (2004). “The role of intolerance of uncertainty in etiology and maintenance,” in Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Advances In Research And Practice , eds R. G. Heimberg, C. L. Turk, and D. S. Mennin (New York, NY: Guilford), 143–163.

Epel, E. S., Crosswell, A. D., Mayer, S. E., Prather, A. A., Slavich, G. M., Puterman, E., et al. (2018). More than a feeling: a unified view of stress measurement for population science. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 49:146–169. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2018.03.001

Furnham, A., and Marks, J. (2013). Tolerance of ambiguity: a review of the recent literature. Psychology 4, 717–728. doi: 10.4236/psych.2013.49102

Han, K. (2021). Students’ well-being: the mediating roles of grit and school connectedness. Front. Psychol. 12:787861. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.787861

Hillen, M. A., Gutheil, C. M., Strout, T. D., Smets, E. M. A., and Han, P. K. J. (2017). Tolerance of uncertainty: conceptual analysis, integrative model, and implications for healthcare. Soc. Sci. Med. 180, 62–75. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.024

Iannello, P., Mottini, A., Tirelli, S., Riva, S., and Antonietti, A. (2017). Ambiguity and uncertainty tolerance, need for cognition, and their association with stress. A study among Italian practicing physicians. Med. Educ. Online 22:1270009. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2016.1270009

Kamran, S. K. (2011). Effect of gender on ambiguity tolerance of Iranian English language learners. J. Educ. Pract. 2, 25–32.

Kamtsios, S., and Karagiannopoulou, E. (2015). Exploring relationships between academic hardiness, academic stressors and achievement in university undergraduates. J. Appl. Educ. Policy Res. 1, 53–73.

Khattak, Z. I., Jamshed, T., Ahmad, A., and Baig, M. N. (2011). An investigation into the causes of English language learning anxiety in students at AWKUM. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 15, 1600–1604.

Li, C. (2020). Emotional intelligence and English achievement: the mediating effects of enjoyment, anxiety, and burnout. Foreign Lang. World 1, 69–78.

Liao, K. Y. H., and Wei, M. (2011). Intolerance of uncertainty, depression, and anxiety: the moderating and mediating roles of rumination. J. Clin. Psychol. 67, 1220–1239. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20846

Maslach, C., and Leiter, M. P. (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 15, 103–111. doi: 10.1002/wps.20311

Nezhad, H. Y., Atarodi, I., and Khalili, M. (2013). Why on earth is learners’ patience wearing thin: the interplay between ambiguity tolerance and reading comprehension valence of Iranian intermediate level students. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 3, 1490–1495.

Rajoo, K. S., Karam, D. S., and Abdul Aziz, N. A. (2019). Developing an effective forest therapy program to manage academic stress in conservative societies: a multi-disciplinary approach. Urban For. Urban Green. 43, 126–353.

Ramli, N. H. H., Alavi, M., Mehrinezhad, S. A., and Ahmadi, A. (2018). Academic stress and self-regulation among university students in Malaysia: mediator role of mindfulness. Behav. Sci. 8, 12–20. doi: 10.3390/bs8010012

Robins, T. G., Roberts, R. M., and Sarris, A. (2018). The role of student burnout in predicting future burnout: exploring the transition from university to the workplace. Higher Educ. Res. Dev. 37, 115–130. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2017.1344827

Salanova, M., and Llorens, S. (2008). Current state of research on burnout and future challenges. Papeles Psicólogo 29, 59–67.

Schaufeli, W. B., and Taris, T. W. (2005). The conceptualization and measurement of burnout: common ground and worlds apart. Work Stress 19, 256–262. doi: 10.1080/02678370500385913

Shihata, S., McEvoy, P. M., Mullan, B. A., and Carleton, R. N. (2016). Intolerance of uncertainty in emotional disorders: what uncertainties remain? J. Anxiety Disord. 41, 115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.05.001

Tynan, M. C. (2020). Multidimensional Tolerance Of Ambiguity: Construct Validity, Academic Success, And Workplace Outcomes. Doctoral dissertation. Ames, IA: Iowa State University.

Varasteh, H., Ghanizadeh, A., and Akbari, O. (2016). The role of task value, effort-regulation, and ambiguity tolerance in predicting EFL learners’ test anxiety, learning strategies, and language achievement. Psychol. Stud. 61, 2–12. doi: 10.1007/s12646-015-0351-5

Wang, Y. L., and Guan, H. F. (2020). Exploring demotivation factors of Chinese learners of English as a foreign language based on positive psychology. Rev. Argent. Clin. Psicol. 29, 851–861. doi: 10.24205/03276716.2020.116

Wang, Y. L., Derakhshan, A., and Zhang, L. J. (2021). Researching and practicing positive psychology in second/foreign language learning and teaching: the past, current status and future directions. Front. Psychol. 12:731721. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.731721

Xu, H., and Tracey, T. J. G. (2014). The role of ambiguity tolerance in career decision making. J. Vocat. Behav. 85, 18–26.

Yang, H. (2004). Factors affecting student burnout and academic achievement in multiple enrolment programs in Taiwan’s technical-vocational colleges. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 24, 283–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ijedudev.2003.12.001

Zhang, Y., Gan, Y., and Cham, H. (2007). Perfectionism, academic burnout, and engagement among Chinese college students: a structural equation modeling analysis. Pers. Individ. Dif. 43, 1529–1540. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.04.010

Keywords : learners’ academic stress, ambiguity of tolerance, burnout, positive psychology, emotional fatigue

Citation: Xu J and Ba Y (2022) Coping With Students’ Stress and Burnout: Learners’ Ambiguity of Tolerance. Front. Psychol. 13:842113. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.842113

Received: 23 December 2021; Accepted: 14 January 2022; Published: 17 February 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Xu and Ba. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jian Xu, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Interventions to reduce burnout in students: A systematic review and meta-analysis

- Open access

- Published: 03 August 2023

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Daniel J. Madigan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9937-1818 1 ,

- Lisa E. Kim 2 &

- Hanna L. Glandorf 1

3751 Accesses

3 Citations

Explore all metrics

Burnout is common among students and can negatively influence their motivation, performance, and wellbeing. However, there is currently little consensus regarding how to intervene effectively. Consequently, we provide the first systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing burnout in students. A systematic literature search returned 17 studies (10 randomized controlled trials and 7 quasi-experimental trials), which included 2,462 students from secondary and tertiary levels of education. These studies used a range of interventions (e.g., mindfulness, rational emotive behavior therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy). When the effects were aggregated across interventions, there was evidence for their effectiveness in reducing total burnout ( g + = 0.90, p = .02, 95% CI: [0.04, 1.75], k = 14). However, we also found evidence for moderation and nonsignificant effects when certain symptoms, designs, and intervention-types were examined. The strongest evidence for effectiveness was for randomized controlled trials, rational emotive behavior therapy, and mindfulness-based interventions. This review provides initial evidence for the efficacy of interventions in reducing burnout in students, but we note that a more systematic examination of particular intervention types, especially those designed to target the organisational-level, would be useful, and to have the most impact in informing policy, so too are studies examining the cost effectiveness of such interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Long-term analysis of a psychoeducational course on university students’ mental well-being

Catherine Hobbs, Sarah Jelbert, … Bruce Hood

Burnout in nursing: a theoretical review

Chiara Dall’Ora, Jane Ball, … Peter Griffiths

Academic Stress Interventions in High Schools: A Systematic Literature Review

Tess Jagiello, Jessica Belcher, … Viviana M. Wuthrich

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Student wellbeing is of growing concern to teachers, parents, and policymakers. This is because students appear to be increasingly susceptible to a range of mental and physical health problems, including depression, loneliness, and anxiety (e.g., Duffy et al., 2019 ; Twenge et al., 2018 ). One particular indication of poor mental wellbeing in a school context is burnout. Burnout not only negatively affects student mental health, but also has further negative consequences for achievement and motivation (e.g., Madigan & Curran, 2021 ; Ribeiro et al., 2018 ; Walburg, 2014 ). These effects may have only been exacerbated as a function of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Salmela-Aro et al., 2022 ). As a consequence, in the present study, we provide the first systematic review and meta-analysis of studies examining interventions aimed at reducing burnout in students. We hope our findings will provide a basis from which to inform relevant policy and practice intending to safeguard student wellbeing.

The concept of burnout came to prominence in the mid-1970s. It was introduced to reflect observations of gradual exhaustion, cynicism, and loss of commitment in human services professionals (Maslach & Jackson, 1981 ). Theorized to arise as a result of chronic work stress, burnout was defined as a multidimensional syndrome comprising three symptoms. These symptoms are exhaustion (feelings of being emotionally overextended and exhausted by one's work), cynicism (a cynical and impersonal response toward recipients of one's care), and reduced efficacy (no longer feeling competent and successful at one’s work; Maslach et al., 1986 ). Much work has since explored complimentary theoretical approaches (e.g., Job Demands-Resources Theory; Bakker & de Vries, 2021 ) and clarified burnout’s distinctiveness from other wellbeing issues (e.g., depression; Meier & Kim, 2022 ). This work has also explored many negative outcomes associated with burnout, of which the most notable include interpersonal conflict, attrition, and reduced performance (Alarcon, 2011 ; Madigan & Kim, 2021a ; Taris, 2006 ). The latter has even been found to be a function of other peoples’ burnout (e.g., teacher burnout leading to worse student performance; Madigan & Kim, 2021b ).

Burnout affects individuals in a range of contexts but appears to be particularly common in education. In this regard, students themselves appear to be especially vulnerable to burnout. Although not formally considered work, the activities that students undertake for education share many similarities with those undertaken in work contexts (Schaufeli et al., 2002 ). For example, they attend classes and complete structured activities with specific goals in mind (e.g., gaining credits, passing a course, obtaining a degree). Accordingly, burnout can be contextualized to the academic domain for students. In this manner, student burnout represents a multidimensional syndrome of exhaustion from studying, cynicism directed towards one’s study, and reduced efficacy in relation to academic work (Salmela-Aro et al., 2009 ; Schaufeli et al., 2002 ).

Like in other work contexts, burnout in students has been linked to many outcomes. In this regard, it appears that burnout comes with several significant costs for students’ mental health. These costs include an increased likelihood of depression, more frequent suicidal ideation, and more intense feelings of anxiety (Walburg, 2014 ). Burnout will also negatively affect students’ motivation. This includes the thwarting of basic psychological needs and resulting shifts from autonomous to more controlled forms of motivation (Cazan, 2015 ; Rehman et al., 2020 ; Zhang et al., 2013 ). It is also possible that students’ self-worth and self-esteem will be negatively affected (Dyrbye et al., 2008 ; IsHak et al., 2013 ; Walburg, 2014 ). Finally, burnout will affect how students behave in the classroom. Such changes include increased apathy, more disruptive behaviours, and even absence from the classroom altogether (Schramer et al., 2019 ; Walburg, 2014 ). Combined, these changes can result in impaired student achievement (Madigan & Curran, 2021 ).

Interventions to reduce burnout

Given the many ways in which burnout can affect individuals across a variety of contexts, a growing body of work has sought to develop and test interventions aimed at reducing burnout symptoms. These interventions have been informed by various theoretical perspectives, including those originally proposed by Maslach and colleagues (e.g., Awa et al., 2010 ). Interventions have, therefore, been designed to target factors at the individual level (e.g., delivering stress management training) as well as at the organizational level (e.g., changing working hours; Maslach et al., 2012 ). In regards to specific examples of such interventions, in addition to traditional cognitive behavioral therapy techniques such as stress management and relaxation, developments from what is known as the third wave of cognitive behavioral therapy including mindfulness have been employed. The former techniques are based around changing underlying cognitive processes and patterns which in turn lead to more adaptive behaviours (e.g., Shafran et al., 2009 ), while the latter relates to the ability to stay attuned to the present in a non-judgmental manner, rather than ruminating about the past or worrying about the future (Kabat-Zinn, 2003 ).

There is evidence to suggest that interventions can indeed be effective in reducing burnout. For example, a review of interventions in physicians showed that they decreased burnout by approximately 10%, with both individual and organizational interventions being effective (West et al., 2016 ). The same is true for interventions with other medical professionals (e.g., nurses; Lee et al., 2016 ). Similarly, a review of the interventions for teacher burnout found small but significant reductions in total burnout, exhaustion, and reduced efficacy (Iancu et al., 2018 ). Finally, there is direct evidence for the effectiveness of burnout interventions in academic contexts. Specifically, a number of systematic reviews have shown that interventions can reduce burnout in medical residents (individuals practicing medicine under supervision; see e.g., Walsh et al., 2019 ), and that these are primarily based around duty hour restrictions (e.g., Williams et al., 2015 ).

What is currently unclear, however, is whether such interventions work for undergraduate and postgraduate students, and also for those in secondary education. This is particularly important because the conditions and experiences of students in these domains will likely differ substantially from those in medical contexts. For example, there will be differences in the hours worked, a different emphasis of training (theoretical vs. practical and field-based), and, especially for secondary students, differences in the type of tasks required of them (e.g., Honney et al., 2010 ). In addition, interventions (and how these are implemented) are likely to vary substantially too (e.g., duty hours do not apply; Busireddy et al., 2017 ). Yet, there is evidence that the performance, motivation, and wellbeing consequences for those engaged in undergraduate and postgraduate programs are just as severe (e.g., Madigan & Curran, 2021 ). There are also likely to be differences in working conditions and associated burnout interventions in comparison to occupations more broadly (see e.g., West et al., 2016 ). Collectively, these issues highlight the importance and necessity of effective student-focused burnout interventions.

The present study

Although intervention studies to reduce burnout in secondary, undergraduate, and postgraduate students have previously been conducted (e.g., Bresó et al., 2011 ), there has been no systematic summary of these studies. Moreover, we currently do not know what types of interventions have been employed, and perhaps more importantly, whether interventions are effective for these students. It is against this background that the present study aims to provide the first systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions aimed at reducing burnout in students. In doing so, given the strength of evidence they provide, we also focus on controlled trials. We first summarize the literature to identify what has been done so far and then conduct a meta-analysis to determine the interventions’ effectiveness. We then aim to discuss the implications for policy and practice.

Literature search

Following relevant recommendations (Page et al., 2021 ), we began with an extensive computerized literature search of the following psychology and education databases: PsychARTICLES, PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Education Abstracts, Educational Administration Abstracts, and ProQuest Dissertations. The following search terms were used: (burnout OR exhaustion OR depersonalization OR cynicism OR “reduced efficacy” OR “professional accomplishment”) AND (student) AND (intervention OR trial OR program OR treatment OR training OR workshop OR experiment OR RCT). The search was conducted in January 2023, and to be inclusive as possible we specified no explicit start date for the search. We included grey literature (theses, dissertations, conference presentations) in an attempt to reduce publication bias. As well as conducting this standardized search, we conducted an exploratory search on GoogleScholar and we also scanned the reference lists of relevant reviews, book chapters, and journal articles.

Inclusion criteria

We included studies in the present review if they: (a) included at least one treatment condition aimed at reducing burnout (either the primary or secondary outcome of the intervention); (b) included a control group; (c) measured burnout as an outcome; (d) examined students; (e) were published in English; (f) were a published journal article, thesis, dissertation, or conference presentation; (g) included a sample that was independent (not included in more than one study); and (h) included a sample of students outside the medical discipline.

Data extraction

We then reviewed studies in full and in order to summarize these studies, the following data were extracted: (a) publication information (authors/year), (b) n for experimental group, (c) n for control group, (d) instructional environment/level (secondary or tertiary), Footnote 1 (e) measure of burnout, (f) study design, (g) mode of delivery, (h) intervention duration, (i) intervention type, and (j) the main findings. Two authors then extracted the data. We calculated inter-rater reliability using Cohen’s Kappa (McHugh, 2012 ). Disagreements were resolved via a consensus among authors with reference to the original material.

Risk of bias

We then provided an assessment of the quality of studies. Here, we followed the assessment process outlined by Iancu et al. ( 2018 ) which was based on the Cochrane Collaboration tool (Higgins & Green, 2011 ). Studies were assessed against the six criteria proposed in this tool (i.e., sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessor, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other potential threats to validity). For each of these criteria, studies were rated as having a low risk of bias, high risk of bias, or unclear risk of bias. Like Iancu et al., we computed three scores representing the total number of criteria on which each study was classified as having a low, high, or unclear risk of bias.

Meta-analytic procedures

In addition to summarizing the studies, we also assessed the effectiveness of burnout interventions for students by means of meta-analysis. In doing so, we examined posttest between group effect sizes (experimental vs. control group). Effect sizes were calculated for each study for each of the following outcome measures: (1) total burnout, (2) exhaustion, (3) cynicism, and (4) reduced efficacy. For those studies that did not report a total burnout score, the average of burnout effect sizes for a given study was used (see Dreison et al., 2018 ).

Following the recommendations of Lipsey and Wilson ( 2001 ), we used random-effects models to derive effect sizes and confidence intervals, as these models allow generalization beyond the present set of studies to future studies (Schmidt et al., 2009 ). An effect is significant ( p < 0.05) if its 95% confidence interval does not include zero. In addition, to ensure statistical independence, each study contributed no more than one effect size per analysis (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001 ). We conducted the analyses using Meta-Essentials (Suurmond et al., 2017 ).

The analyses were based on Hedges’ g (Borenstein et al., 2009 ). Hedge’s g corrects for small samples and results in a less biased estimates compared to Cohen’s d (Borenstein et al., 2009 ). Moreover, it is also possible to interpret Hedge’s g in much the same way as Cohen’s d : with a g of 0.20 considered small, 0.50 considered medium, and 0.80 considered large (Cohen, 1992 ). We used means, standard deviations, and sample sizes to calculate g .

We report the total heterogeneity of the meta-analytic effect sizes ( Q T ), which provides an indication of whether the variance of the meta-analytic effect size is greater than that which would be expected from sampling error. The degree of inconsistency in the observed relationship across studies ( I 2 ) was also calculated. Values of 25%, 50%, and 75% are indicative of low, medium and high levels of heterogeneity (Higgins & Thompson, 2002 ).

Where substantial levels of heterogeneity were found, we conducted subgroup analyses. These analyses centered around the heterogeneity explained by any categorization in the data ( Q B ). When Q B is statistically significant there are differences between categories in terms of their effect sizes. Specific differences can be examined by comparing the overlap between 95% confidence intervals for effect sizes.

Finally, we assessed studies for publication bias. Tests of publication bias examine whether studies with statistically significant results are more likely to be published than non-statistically significant results (Rothstein et al., 2005 ). To do so, we first examined Rosenthal’s ( 1979 ) fail-safe number. This number should be greater than 5 k + 10 (where k is the number of effect sizes; Rosenthal, 1979 ). Then, we calculated Egger’s regression intercept that regresses the effect size on the reciprocal of its standard error (Egger et al., 1997 ). If no publication bias is present, the 95% confidence interval of Egger’s regression coefficient includes zero.

We begin by providing the results of the search and selection process we then provide an overview of the characteristics of the included studies. This includes the design of the studies, the samples recruited, the measures of burnout that were used, and an evaluation of the quality of the studies. We then provide an overview of the interventions. Finally, we report the findings of the meta-analyses. Table 1 provides further details for each study.

Study selection

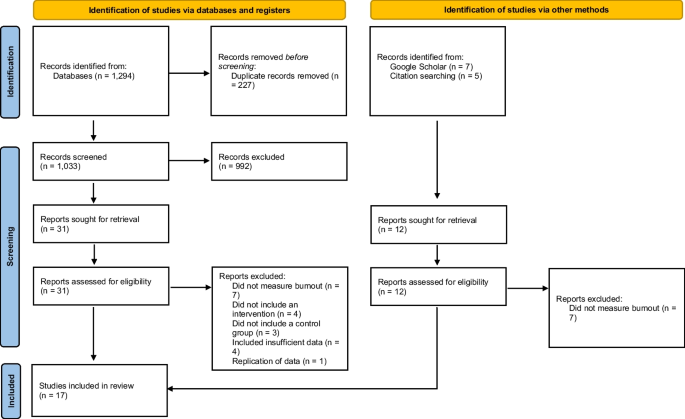

Our search returned 1,294 studies. Once duplicates were removed and abstracts were screened for relevance, 43 studies remained. These studies were then further assessed using the inclusion criteria. When we reviewed full texts, studies were excluded because they did not measure burnout ( n = 14), did not include an intervention ( n = 4), did not include a control group ( n = 3), repeated data published elsewhere ( n = 1), or included insufficient information ( n = 4). These criteria therefore resulted in the final inclusion of 17 studies. We have provided an overview of this process in Fig. 1 . The extracted data can be found in Table 1 . The average value of Cohen’s Kappa across all coded data was 0.92 indicating an excellent level of inter-rater reliability.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) diagram illustrating study selection process

Study designs

Ten of the studies adopted randomized controlled trials and seven studies adopted quasi-experimental trials. In addition, all studies were published journal articles.

Student samples

A total of 2,462 students were recruited across the present studies, of which 1,301 (range = 8–522, median = 30) were in the experimental groups, and 1,161 (range = 6–512, median = 32) in the control groups. In regard to which educational levels the students were recruited from, 15 of the studies were from tertiary settings (13 from undergraduate levels, and two from postgraduate levels) and two studies were from secondary settings.

Measures of burnout

In the 17 studies included in the present review, ten studies used the Maslach Burnout Inventory–Student Survey (Maslach et al., 1996 ). Three studies used the Student Burnout Inventory (Salmela-Aro et al., 2009 ). Three studies used the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory–Student Version (Reis et al., 2015 ) and one study used the original Maslach Burnout Inventory (Maslach et al., 1986 ). We have summarized this information in addition to including evidence for reliability of each measure (Cronbach’s alpha) in Table 2 . Overall, all measures had at least some evidence for their reliability in the student samples (alpha > 0.70; Nunnally, 1978 ), with only a couple of instances where alpha fell below this accepted threshold.

An overview of study quality ratings is presented in Table 1 . On the whole, based on meeting at least three of the criteria, there were five studies that appeared to be at a low risk and twelve studies that appeared to be at low-to-high risk.

Intervention outcomes

We now summarize specific intervention types. In doing so, we elaborate on what they were, how they were delivered, and their associated effectiveness (see also Table 1 for specific details for each study).

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction

Mindfulness relates to the ability to stay attuned to the present, rather than ruminating about the past or worrying about the future. A total of six interventions adopted this approach (two randomized controlled trials, four quasi-experimental studies; Clarkson et al., 2019 ; de Vibe et al., 2013 ; Lo et al. 2021 ; Modrego-Alarcon et al., 2021 ; O'Driscoll et al., 2019a ; O'Driscoll et al., 2019b ). The majority were delivered in person (5/6) and ranged from 4 to 8 weeks in length. 50% were effective in reducing at least one burnout symptom. Those that were effective were typically longer in duration (on average 1.5 h per week for 6 weeks) and adopted a range of delivery methods (in person, group, and online). Effect sizes were typically medium-sized ( g = 0.30–0.70).

Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy

Rational emotive behavior therapy seeks to identify, challenge, and restructure irrational beliefs that are believed to underpin a negative pattern of behavior. Four studies followed this approach (all randomized controlled trials; Ezenwaji et al., 2019 ; Ezeudu et al., 2020 ; Igbokwe et al., 2019 ; Ogbuanya et al., 2019 ). All interventions were delivered in person and were either 10 or 12 weeks in duration (and approximately 20 sessions in total). All interventions were effective in reducing either total burnout or its symptoms with very large effect sizes ( g > 2.00). We note here that all samples were recruited based on high initial burnout levels, which may help explain the very large effects in these studies.

Psychoeducation

Four studies adopted interventions that could be considered psychoeducational (systematic and structured knowledge transfer) (two randomized controlled trials and two quasi-experimental studies; Charbonnier et al., 2022 ; Fang et al., 2021 ; Noh et al., 2020 ; Vuori et al., 2008 ). They were all delivered in a range of formats (online, phone, in person) and ranged from 1 to 8 weeks in duration. Half the Interventions were effective. Total burnout was reduced compared to the control for an intervention designed to helps students approach important goals (that they had been avoiding; Fang et al., 2021 ) and for an intervention promoting skills for the transition from school, specifically in individuals with learning difficulties (Vuori et al., 2008 ). Effect sizes were medium-sized ( g = 0.65).

Two studies utilized exercise as part of the intervention strategy (both randomized controlled trials; May et al., 2019 ; Rosales-Ricardo & Ferreira, 2022 ). May et al. ( 2019 ) compared 4-weeks high intensity interval training to biofeedback and control conditions. Biofeedback resulted in reduced burnout compared to the control with a large effect size ( g > 1.0). Rosales-Ricardo and Ferreira ( 2022 ) compared aerobic exercise (low intensity) to strength training both for 16 weeks (3 times per week). Burnout symptoms reduced following the exercise intervention but not compared to the control group.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

CBT refers to strategies based around changing underlying cognitive processes and patterns. One study adopted this approach adopting a quasi-experimental design (Bresó et al., 2011 ). The intervention specifically used CBT principles to enhance self-efficacy (one’s belief in one’s capacity). A total of 4 sessions over 4 months, delivered in person, resulted in reduced burnout symptoms compared to a healthy control group (but not a stressed control group) with small-to-medium effect sizes ( g = 0.30).

Meta-analytic findings

Overall effect sizes.

Effects sizes for each study can be found in Table 3 . The findings of the meta-analysis can be found in Table 4 . Interventions appeared to be effective in reducing total burnout ( g + = 0.90; p = 0.02, 95% CI: [0.04, 1.75]; k = 14; Q T = 228.34; I 2 = 94.31%). There was however less evidence for their effectiveness in relation to exhaustion ( g + = 0.47; p = 0.06, 95% CI: [-0.03, 0.97]; k = 9; Q T = 33.10; I 2 = 75.83%), cynicism ( g + = 0.51; p = 0.33, 95% CI: [-0.69, 1.71]; k = 9; Q T = 80.54; I 2 = 90.07%), and reduced efficacy ( g + = 0.37; p = 0.28, 95% CI: [-0.59, 1.32]; k = 5; Q T = 20.53; I 2 = 80.51%).

Moderation Analysis

An examination of the total heterogeneity of the meta-analytic effects suggested that there was substantial moderation. We therefore conducted moderation analyses based on the study design (randomised controlled trial versus quasi-experimental trial) and the type of intervention. The results of these analyses are presented in Tables 5 and 6 . For total burnout, studies adopting a randomised controlled design showed larger effects ( g + = 1.60; p = 0.03, 95% CI: [0.16, 3.03]) than studies adopting a quasi-experimental design ( g + = 0.23; p = 0.001, 95% CI: [0.09, 0.37]). The only other significant effect was for quasi-experimental designs for exhaustion ( g + = 0.26; p < 0.001, 95% CI: [0.15, 0.37]). For total burnout, studies employing REBT showed larger effects ( g + = 4.42; p < 0.001, 95% CI: [3.20, 5.64]) than mindfulness ( g + = 0.27; p < 0.001, 95% CI: [0.19, 0.35]), psychoeducation ( g + = 0.22; p = 0.37, 95% CI: [-0.27, 0.71]), and exercise ( g + = 0.79; p = 0.06, 95% CI: [-0.03, 1.62]). The only other significant effect was for mindfulness for exhaustion ( g + = 0.32; p < 0.001, 95% CI: [0.22, 0.43]).

Publication Bias

Results of publication bias analyses can be found in Table 4 . For the majority of effects there was little evidence for publication bias (e.g., Egger’s intercept was nonsignificant). There was some evidence specifically for reduced efficacy where both Rosenthal’s fail-safe number and Egger’s intercept were indicative of publication bias. The findings for reduced efficacy should therefore be interpreted with caution.

The aim of the present study was to provide the first systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions aimed at reducing burnout in students. We found 17 studies adopting a broad range of intervention strategies, and which focused on secondary and tertiary levels of education. Overall, when considered individually and, when effects were aggregated, for total burnout, we found support for the efficacy of interventions in reducing student burnout. However, we also found evidence for moderation and nonsignificant effects when certain symptoms, designs, and intervention-types were examined. We now discuss the key findings of the review and then make recommendations for future research and provide implications for practice.

Key findings

Although numerous reviews exist examining the effects of interventions on students’ mental health (e.g., Regehr et al., 2013 ), until now, no such review existed for interventions targeting burnout. Its absence was surprising given the serious implications that burnout has for students’ performance, motivation, and mental health (e.g., Walburg, 2014 ). In line with reviews of burnout interventions in other contexts, including teachers (e.g., Iancu et al., 2018 ), we found evidence that researchers have begun to test many different types of interventions to reduce student burnout. This includes interventions based around stress reduction (e.g., mindfulness), challenging irrational beliefs (e.g., rational emotive behavior therapy), as well as more classical approaches (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy). In addition, these interventions have been tested across a range of educational levels, but with most studies focused on tertiary levels.

Again, in line with reviews in other contexts, and in medical residents (e.g., Walsh et al., 2019 ), we found some evidence that the reviewed interventions are effective in reducing burnout symptoms in students. Evidence for this comes from both the individual studies and also from the results of the meta-analyses, at least in context of total burnout. The strongest evidence appears to come from those interventions with a strong theoretical foundation. Most notably, this includes rational emotive behavior therapy where all four interventions, all based on randomized controlled designs, were found to be effective, and meta-analytic effect sizes could be considered large (and larger than other intervention types). However, we note that these studies recruited students with high initial levels of burnout and so it is unclear whether such approaches would be beneficial to students with more moderate symptoms. Meta-analytic effects were also significant for mindfulness-based interventions. This finding is similar to research in other occupations (e.g., nursing; Suleiman-Martos et al., 2020 ). Collectively, then, these findings provide promising evidence that we can likely do something to aid students who may be suffering from high levels of burnout.

Critical considerations and recommendations

We now provide recommendations for future work in this area. The first and perhaps most important consideration for future work is to simply conduct more studies testing burnout interventions. Aside from those examining mindfulness and rational emotive behavior therapy, there has not been any systematic examination of specific interventions or intervention types. In addition, conducting controlled studies, especially those with randomized designs, should be prioritized. As illustrated by our study quality analysis, only five studies were deemed to represent high quality designs, analysis, and reporting. Researchers should therefore attempt to design studies of high quality in order to most accurately determine the effectiveness of burnout interventions.

We note that all of the interventions we summarized in the present review implemented interventions based at the individual-level (i.e., providing students with the skills and resources to overcome burnout). Consequently, there is a need for the development and testing of interventions focusing on the organisational-level. Such studies could look to change factors that may be contributing to chronic stress in students, which could include changes in exam structures, contact hours, and social expectations (e.g., Regehr et al., 2013 ). We know that organizational stressors are involved in the development of stress and burnout (e.g., Parrello et al., 2019 ), as such, testing the efficacy of this type of intervention would be extremely useful in offering alternative means to help students and will likely have broader benefits for student mental health.

Implications for practice

Based on the present findings, we now consider several implications for practice. First, professionals concerned with student burnout in their institutions may wish to examine the characteristics and effectiveness of the interventions they use based on the current study findings. For example, they may wish to incorporate different interventions, such as mindfulness, which boasts a growing body of literature that supports its efficacy in reducing stress and burnout in multiple contexts (Luken & Sammons, 2016 ). In addition, for interventions to be most effective, it is important that they are made readily accessible and available by schools and universities, which could be in the form of after school groups or individual school counselling sessions. Given the increased use of technology in our everyday lives, both offline and online forms of support are recommended.

Further to the interventions reviewed here, there have been recent calls to include skills and techniques that have the potential to safeguard student mental health within educational curricula. For example, the OECD has been emphasizing the importance of students’ social emotional competences, and how they are important for students’ immediate and future success, including their mental health and wellbeing (Chernyshenko et al., 2018 ). In much the same manner, integrating social emotional competencies into educational programs and curricula may be useful for preventing and alleviating some of the stress and burnout that readily develops in schools and universities.

In addition, burnout awareness should be promoted to educators and students as a method to prevent and reduce burnout in students (e.g., Salerno, 2016 ). Such awareness programs and methods should include teaching students to recognize the symptoms of burnout and where and how to seek support when necessary. Additionally, teachers should be equipped to understand how to identify and assist students who may be showing symptoms of burnout, and how to refer them to the appropriate professionals, and to even be able to help these students within their own classrooms too. These strategies should encourage students to both help themselves and accept help from those close by, and will possibly reduce the need to intervene altogether.

Finally, in order to assess and ensure optimal benefits from the interventions, policymakers may also wish to examine their cost-effectiveness. Assessing the cost-effectiveness of interventions has been the subject of little conversation in the burnout literature. Once the effectiveness of an intervention has been established, it is important to consider the resources required to deliver that intervention. This can be approached in two ways: first, by achieving maximal health benefits for a fixed amount of resources and second, by identifying a health status objective and the associated minimal amount of resources required to achieve that objective (see Detsky & Naglie, 1990 ). It will be important for public policy to consider which approach should be adopted in relation to burnout when considering which interventions and/or types of interventions are recommended to institutions that serve students. At this stage, however, studies that examine the cost-effectiveness of burnout interventions need to be conducted. Such an evidence base will have many benefits, especially in relation to lobbying schools and universities to adopt relevant interventions.

We provided the first systematic review and meta-analysis of research examining the efficacy of interventions to reduce burnout in students. When the effects were aggregated across interventions, there was evidence for their effectiveness in reducing burnout, at least for total burnout. There was also evidence for specific types of intervention such as those based on rational emotive behavior therapy and mindfulness. Although this study provides initial evidence to inform practice in reducing burnout in students, we note that a more systematic examination of particular intervention types, especially those designed to target the organisational-level, would be useful, as are studies examining the cost effectiveness of such interventions.

This broad classification was based on UNESCO’s International Standard Classification of Education (2012): Secondary (subject-oriented curriculum and employment relevant skills; e.g., high school) and Tertiary levels (intermediate and advanced academic and professional skills, knowledge and competencies; e.g., university).

Awa, W. L., Plaumann, M., & Walter, U. (2010). Burnout prevention: A review of intervention programs. Patient Education and Counseling, 78 , 184–190.

Article Google Scholar

Alarco, G. M. (2011). A meta-analysis of burnout with job demands, resources, and attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79 , 549–562.

Bakker, A. B., & de Vries, J. D. (2021). Job Demands-Resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 34 (1), 1–21.

Billingsley, B., & Bettini, E. (2019). Special education teacher attrition and retention: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 89 , 697–744.

Borenstein, M., Cooper, H., Hedges, L., & Valentine, J. (2009). Effect sizes for continuous data. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis, 2 , 221–235.

Google Scholar

*Bresó, E., Schaufeli, W. B., & Salanova, M. (2011). Can a self-efficacy-based intervention decrease burnout, increase engagement, and enhance performance? A quasi-experimental study. Higher Education , 61 , 339-355

Busireddy, K. R., Miller, J. A., Ellison, K., Ren, V., Qayyum, R., & Panda, M. (2017). Efficacy of interventions to reduce resident physician burnout: A systematic review. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 9 , 294–301.

Cazan, A. M. (2015). Learning motivation, engagement and burnout among university students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 187 , 413–417.

Charbonnier, E., Trémolière, B., Baussard, L., Goncalves, A., Lespiau, F., Philippe, A. G., & Le Vigouroux, S. (2022). Effects of an online self-help intervention on university students’ mental health during COVID-19: A nonrandomized controlled pilot study. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 5 , 100175

Chernyshenko, O., Kankaraš, M., & Drasgow, F. (2018). Social and emotional skills for student success and well-being: Conceptual framework for the OECD study on social and emotional skills (No. 173). OECD Education Working Papers.

*Clarkson, M., Heads, G., Hodgson, D., & Probst, H. (2019). Does the intervention of mindfulness reduce levels of burnout and compassion fatigue and increase resilience in pre-registration students? A pilot study. Radiography, 25 , 4-9.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112 , 155–163.

Cooley, E., & Yovanoff, P. (1996). Supporting professionals-at-risk: Evaluating interventions to reduce burnout and improve retention of special educators. Exceptional Children, 62 , 336–355.

Daya, Z., & Hearn, J. H. (2018). Mindfulness interventions in medical education: A systematic review of their impact on medical student stress, depression, fatigue and burnout. Medical Teacher, 40 , 146–153.

Detsky, A. S., & Naglie, I. G. (1990). A clinician’s guide to cost-effectiveness analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 113 , 147–154.

Dreison, K. C., Luther, L., Bonfils, K. A., Sliter, M. T., McGrew, J. H., & Salyers, M. P. (2018). Job burnout in mental health providers: A meta-analysis of 35 years of intervention research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23 , 18–28.

Duffy, M. E., Twenge, J. M., & Joiner, T. E. (2019). Trends in mood and anxiety symptoms and suicide-related outcomes among US undergraduates, 2007–2018: Evidence from two national surveys. Journal of Adolescent Health, 65 , 590–598.

Dyrbye, L. N., Thomas, M. R., Massie, F. S., Power, D. V., Eacker, A., Harper, W., ... & Sloan, J. A. (2008). Burnout and suicidal ideation among US medical students. Annals of Internal Medicine , 149 , 334–341.

Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315 (7109), 629–634.

*Ezenwaji, I. O., Eseadi, C., Ugwoke, S. C., Vita-Agundu, U. C., Edikpa, E., Okeke, F. C., ... & Njoku, L. G. (2019). A group-focused rational emotive behavior coaching for management of academic burnout among undergraduate students: Implications for school administrators. Medicine, 98 , 1–11.

*Ezeudu, F. O., Nwoji, I. H. N., Dave-Ugwu, P. O., Abaeme, D. O., Ikegbunna, N. R., Agugu, C. V., ... & Nwefuru, B. C. (2020). Intervention for burnout among chemistry education undergraduates in Nigeria. Journal of International Medical Research, 48 , 0300060519867832.

Fanelli, D. (2012). Negative results are disappearing from most disciplines and countries. Scientometrics, 90 , 891–904.

*Fang, C. M., McMahon, K., Miller, M. L., & Rosenthal, M. Z. (2021). A pilot study investigating the efficacy of brief, phone‐based, behavioral interventions for burnout in graduate students. Journal of Clinical Psychology , 77 , 2725-2745.

Friedman, I. (1999). Teachers’ burnout: The concept and its measurement . Jerusalem: Henrieta Szold Institute.

Groot, W., & Maassen van den Brink, H. (2007). The health effects of education. Economics of Education Review, 26 , 186–200.

Higgins, J. P., & Green, S. (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (Vol. 4). West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.

Higgins, J. P., & Thompson, S. G. (2002). Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 21 (11), 1539–1558.

Honney, K., Buszewicz, M., Coppola, W., & Griffin, M. (2010). Comparison of levels of depression in medical and non-medical students. The Clinical Teacher, 7 , 180–184.

Iancu, A. E., Rusu, A., Măroiu, C., Păcurar, R., & Maricuțoiu, L. P. (2018). The effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing teacher burnout: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30 , 373–396.

*Igbokwe, U. L., Nwokenna, E. N., Eseadi, C., Ogbonna, C. S., Nnadi, E. M., Ololo, K. O., ... & Onwube, O. (2019). Intervention for burnout among English education undergraduates: Implications for curriculum innovation. Medicine, 98 , 45–52.

IsHak, W., Nikravesh, R., Lederer, S., Perry, R., Ogunyemi, D., & Bernstein, C. (2013). Burnout in medical students: A systematic review. The Clinical Teacher, 10 , 242–245.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Constructivism in the Human Sciences, 8 (2), 73.

Lee, H. F., Kuo, C. C., Chien, T. W., & Wang, Y. R. (2016). A meta-analysis of the effects of coping strategies on reducing nurse burnout. Applied Nursing Research, 31 , 100–110.

Levine, T. R., Asada, K. J., & Carpenter, C. (2009). Sample sizes and effect sizes are negatively correlated in meta-analyses: Evidence and implications of a publication bias against nonsignificant findings. Communication Monographs, 76 , 286–302.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis . SAGE publications, Inc.

Lo, H. H. M., Ngai, S., & Yam, K. (2021). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on health and social care education: a cohort-controlled study. Mindfulness, 12 (8), 2050–2058.

Luken, M., & Sammons, A. (2016). Systematic review of mindfulness practice for reducing job burnout. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 70 , 7002250020p1-7002250020p10.

Madigan, D. J., & Curran, T. (2021). Does burnout affect academic achievement? A meta-analysis of over 100,000 students. Educational Psychology Review, 33 , 387–405.

Madigan, D. J., & Kim, L. E. (2021a). Towards an understanding of teacher attrition: A meta-analysis of burnout, job satisfaction, and teachers’ intentions to quit. Teaching and Teacher Education, 105 , 103425.

Madigan, D. J., & Kim, L. E. (2021b). Does teacher burnout affect students? A systematic review of its association with academic achievement and student-reported outcomes. International Journal of Educational Research, 105 , 101714.

Maslach, C. (2003). Job burnout: New directions in research and intervention. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12 , 189–192.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 2 , 99–113.

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1996). Maslach Burnout Inventory manual (3rd ed.). Consulting Psychologist Press.

Maslach, C., Leiter, M. P., & Jackson, S. E. (2012). Making a significant difference with burnout interventions: Researcher and practitioner collaboration. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33 , 296–300.

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., Leiter, M. P., Schaufeli, W. B., & Schwab, R. L. (1986). Maslach Burnout Inventory (Vol. 21, pp. 3463–3464). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting psychologists press.

May, R. W., Seibert, G. S., Sanchez-Gonzalez, M. A., & Fincham, F. D. (2019). Self-regulatory biofeedback training: An intervention to reduce school burnout and improve cardiac functioning in college students. Stress, 22 , 1–8.

McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The Kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22 , 276–282.

Meier, S. T., & Kim, S. (2022). Meta-regression analyses of relationships between burnout and depression with sampling and measurement methodological moderators. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 27 (2), 195.

Modrego-Alarcón, M., Lopez-del-Hoyo, Y., Garcia-Campayo, J., Perez-Aranda, A., Navarro-Gil, M., Beltrán-Ruiz, M., & Montero-Marin, J. (2021). Efficacy of a mindfulness-based programme with and without virtual reality support to reduce stress in university students: A randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 142, 103866

Noh, H., Seong, H., & Lee, S. M. (2020). Effects of motivation-based academic group psychotherapy on psychological and physiological academic stress responses among Korean middle school students. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 70 , 399–424.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory . McGraw-Hill.

O’Driscoll, M., Byrne, S., Byrne, H., Lambert, S., & Sahm, L. J. (2019a). An online mindfulness-based intervention for undergraduate pharmacy students: Results of a mixed-methods feasibility study. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 11 , 858–875.

O’Driscoll, M., Sahm, L. J., Byrne, H., Lambert, S., & Byrne, S. (2019b). Impact of a mindfulness-based intervention on undergraduate pharmacy students’ stress and distress: Quantitative results of a mixed-methods study. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 11 , 876–887.

OECD. (2016). Education at a glance 2016: OECD indicators . OECD Publishing.

Book Google Scholar

*Ogbuanya, T. C., Eseadi, C., Orji, C. T., Omeje, J. C., Anyanwu, J. I., Ugwoke, S. C., & Edeh, N. C. (2019). Effect of rational-emotive behavior therapy program on the symptoms of burnout syndrome among undergraduate electronics work students in Nigeria. Psychological Reports, 122 , 4-22.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., ... & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery , 88 , 105906.

Panagioti, M., Panagopoulou, E., Bower, P., Lewith, G., Kontopantelis, E., Chew-Graham, C., ... & Esmail, A. (2017). Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177 , 195–205.

Parrello, S., Ambrosetti, A., Iorio, I., & Castelli, L. (2019). School burnout, relational, and organizational factors. Frontiers in Psychology, 10 , 32–45.

Purvanova, R. K., & Muros, J. P. (2010). Gender differences in burnout: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77 , 168–185.

Regehr, C., Glancy, D., & Pitts, A. (2013). Interventions to reduce stress in university students: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 148 , 1–11.

Rehman, A. U., Bhuttah, T. M., & You, X. (2020). Linking burnout to psychological well-being: The mediating role of social support and learning motivation. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 13 , 545.

Reis, D., Xanthopoulou, D., & Tsaousis, I. (2015). Measuring job and academic burnout with the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OLBI): Factorial invariance across samples and countries. Burnout Research, 2 , 8–18.

Ribeiro, I. J., Pereira, R., Freire, I. V., de Oliveira, B. G., Casotti, C. A., & Boery, E. N. (2018). Stress and quality of life among university students: A systematic literature review. Health Professions Education, 4 , 70–77.

Ridner, S. L., Newton, K. S., Staten, R. R., Crawford, T. N., & Hall, L. A. (2016). Predictors of well-being among college students. Journal of American College Health, 64 , 116–124.

Roeser, R. W., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Jha, A., Cullen, M., Wallace, L., Wilensky, R., Oberle, E., Thomson, K., Taylor, C., & Harrison, J. (2013). Mindfulness training and reductions in teacher stress and burnout: Results from two randomized, waitlist-control field trials. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105 , 787–804.

Rosales-Ricardo, Y., & Ferreira, J. P. (2022). Effects of physical exercise on Burnout syndrome in university students. MEDICC review, 24 , 36–39.

Rosenthal, R. (1979). The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin, 86 (3), 638.

Rothstein, H. R., Sutton, A. J., & Borenstein, M. (2005). Publication bias in meta-analysis (pp. 1–7). Publication bias in meta-analysis.

Salerno, J. P. (2016). Effectiveness of universal school-based mental health awareness programs among youth in the United States: A systematic review. Journal of School Health, 86 , 922–931.

Salmela-Aro, K., Kiuru, N., Leskinen, E., & Nurmi, J. E. (2009). School burnout inventory (SBI) reliability and validity. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 25 , 48–57.

Salmela-Aro, K., Upadyaya, K., Ronkainen, I., & Hietajärvi, L. (2022). Study burnout and engagement during COVID-19 among university students: The role of demands, resources, and psychological needs. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1–18.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. W. (2005). The conceptualization and measurement of burnout: Common ground and worlds apart. Work & Stress, 19 , 256–262.

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3 , 71–92.

Schmidt, F. L., Oh, I. S., & Hayes, T. L. (2009). Fixed-versus random-effects models in meta-analysis: Model properties and an empirical comparison of differences in results. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 62 (1), 97–128.

Schramer, K. M., Rauti, C. M., Kartolo, A. B., & Kwantes, C. T. (2019). Examining burnout in employed university students. Journal of Public Mental Health, 19 , 17–25.

Shafran, R., Clark, D. M., Fairburn, C. G., Arntz, A., Barlow, D. H., Ehlers, A., & Wilson, G. T. (2009). Mind the gap: Improving the dissemination of CBT. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47 (11), 902–909.

Shrier, I., Boivin, J. F., Steele, R. J., Platt, R. W., Furlan, A., Kakuma, R., ... & Rossignol, M. (2007). Should meta-analyses of interventions include observational studies in addition to randomized controlled trials? A critical examination of underlying principles. American Journal of Epidemiology, 166 , 1203–1209.

Shrout, P. E., & Rodgers, J. L. (2018). Psychology, science, and knowledge construction: Broadening perspectives from the replication crisis. Annual Review of Psychology, 69 , 487–510.

Sterne, J. A., Hernán, M. A., Reeves, B. C., Savović, J., Berkman, N. D., Viswanathan, M., ... & Higgins, J. P. (2016). ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ, 355.

Suleiman-Martos, N., Gomez-Urquiza, J. L., Aguayo-Estremera, R., Cañadas-De La Fuente, G. A., De La Fuente-Solana, E. I., & Albendín-García, L. (2020). The effect of mindfulness training on burnout syndrome in nursing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76 , 1124–1140.

Suurmond, R., van Rhee, H., & Hak, T. (2017). Introduction, comparison, and validation of meta-essentials: A free and simple tool for meta-analysis. Research Synthesis Methods, 8 , 537–553.

Taris, T. W. (2006). Is there a relationship between burnout and objective performance? A critical review of 16 studies. Work & Stress, 20 , 316–334.

Twenge, J. M., Joiner, T. E., Rogers, M. L., & Martin, G. N. (2018). Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among US adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clinical Psychological Science, 6 , 3–17.

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2012). International standard classification of education: ISCED 2011. Comparative Social Research, 30 .

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2016). The world needs almost 69 million new teachers to reach the 2030 education goals (No. 39). http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/fs39-the-world-needs-almost-69-million-new-teachers-to-reach-the-2030-education-goals-2016-en.pdf

*De Vibe, M., Solhaug, I., Tyssen, R., Friborg, O., Rosenvinge, J. H., Sørlie, T., & Bjørndal, A. (2013). Mindfulness training for stress management: a randomised controlled study of medical and psychology students. BMC Medical Education, 13 , 107-115

*Vuori, J., Koivisto, P., Mutanen, P., Jokisaari, M., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2008). Towards working life: Effects of an intervention on mental health and transition to post-basic education. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 72 , 67-80.

Walburg, V. (2014). Burnout among high school students: A literature review. Children and Youth Services Review, 42 , 28–33.

Walsh, A. L., Lehmann, S., Zabinski, J., Truskey, M., Purvis, T., Gould, N. F., ... & Chisolm, M. S. (2019). Interventions to prevent and reduce burnout among undergraduate and graduate medical education trainees: a systematic review. Academic Psychiatry, 43(4), 386–395.

West, C. P., Dyrbye, L. N., Erwin, P. J., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2016). Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 388 , 2272–2281.

Williams, D., Tricomi, G., Gupta, J., & Janise, A. (2015). Efficacy of burnout interventions in the medical education pipeline. Academic Psychiatry, 39 , 47–54.

World Health Organization. (2018). EPHO5: Disease prevention, including early detection of illness . World Health Organization.

Zhang, X., Klassen, R. M., & Wang, Y. (2013). Academic burnout and motivation of Chinese secondary students. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 3 , 134–142.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Science, Technology, and Health, York St John University, York, UK

Daniel J. Madigan & Hanna L. Glandorf

Department of Education, University of York, York, UK

Lisa E. Kim

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Daniel J. Madigan .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Daniel J. Madigan

Current Themes of Research:

Burnout in education.

Relevant Publications:

Madigan, D. J., Kim, L. E., Glandorf, H. L., & Kavanagh, O. (2023). Teacher burnout and physical health: A systematic review. International Journal of Educational Research , 119 , 102173.

Madigan, D. J., & Curran, T. (2021). Does burnout affect academic achievement? A meta-analysis of over 100,000 students. Educational Psychology Review , 33 (2), 387-405.

Madigan, D. J., & Kim, L. E. (2021). Does teacher burnout affect students? A systematic review of its association with academic achievement and student-reported outcomes. International Journal of Educational Research , 105 , 101714.

Teacher effectiveness and wellbeing.

Kim, L. E., Oxley, L., & Asbury, K. (2022). “My brain feels like a browser with 100 tabs open”: A longitudinal study of teachers’ mental health and well‐being during the COVID‐19 pandemic. British Journal of Educational Psychology , 92 , 299-318.

Kim, L. E., & Burić, I. (2020). Teacher self-efficacy and burnout: Determining the directions of prediction through an autoregressive cross-lagged panel model. Journal of Educational Psychology , 112 (8), 1661.

Kim, L. E., Jörg, V., & Klassen, R. M. (2019). A meta-analysis of the effects of teacher personality on teacher effectiveness and burnout. Educational Psychology Review , 31 (1), 163-195.

Hanna L. Glandorf

Burnout and health.

Rights and permissions