This site requires Javascript to be turned on. Please enable Javascript and reload the page.

Toni Morrison's "Playing in the Dark" (2007): Overview

Note: This overview started as teaching notes, which I created for a class called "Theories of Literature and Social Justice." An earlier version of this essay can be found here . --Amardeep Singh, April 2021 Toni Morrison was a groundbreaking figure in multiple fields -- as a novelist of course, as an editor who made it to the top of New York publishing, and also as a literary critic! Alongside all of her other work, Toni Morrison’s literary critical essays have also been hugely influential, and continue to be widely cited by scholars of American literature for their insights and arguments.

Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (1992) has been extremely helpful for scholars interested in thinking about race in American literature, especially American literature by non-black authors. It’s helped to engender an entirely new sub-field that didn’t exist when she wrote it, what we now call “whiteness studies.” Quantitatively, Google scholar indicates a minimum of 9400 citations for this book, which puts it in the top tier of literary critical scholarship, up there with Edward Said’s Orientalism (1979) and Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble (1990) as epochal, paradigm-shifting works.

The argument is actually fairly simple. Here it is in my own words: Morrison argues that the figure of Blackness in "mainstream" American literature plays a decisive role in shaping American culture, as described and documented in literary narrative. If what we understand as distinctively American culture is partly about the the invention of a new, individualized man -- the autonomous figure in Emerson and Thoreau’s writings -- Morrison wants us to remember that that new man is specifically a white man, defining himself in opposition to non-white others. In her various readings, Morrison sees Blackness manifested first in the presence of individual Black characters, some of whom might seem marginal on first glance, but also in a more generalized "Africanism" that points to the legacy of the transatlantic slave trade and the institutionalized racism that accompanied it and followed it. To put it quite simply, the idealized image of American individualism is an image of whiteness that has been built on the exclusion of blackness .

For many American literary critics, this was a controversial claim when Morrison made it, in 1992. There has been a powerful resistance to emphasizing the centrality of race or racism in American literary criticism. Earlier generations of literary critics tended to suggest that despite the obvious importance of slavery in American history, the major figures in canonical American literature -- figures like Hawthorne, Poe, Melville, Whitman, Emerson, Thoreau, Edith Wharton, Wharton, Henry James, T.S. Eliot, Willa Cather -- seemed to have fairly little interest in race, and rarely mentioned it. Moreover, despite the acknowledged existence of Black people, indigenous Americans, and immigrants, the narratives composed by writers like Poe and Melville have been understood by mainstream literary critics as essentially "raceless" and "universal." Morrison wants to rebut both of these claims, first by pointing us to a sampling of passages and moments in the works of canonical white authors where race turns out to be very important. And second, the idea that these representations exist outside of race is a power move by the literary establishment for its own ends, by no means something we have to accept as simply and categorically “true.”

For Morrison, and for the generations of critics who have worked on these questions since this book was published, white Americanness is not simply a universal. Whiteness is something that can and should be be named and studied. (This admittedly makes some people uncomfortable. But remember: when we talk about whiteness, we are not talking about white individuals, we’re talking about whiteness as an analytical category .) Second, whiteness is always, always relational -- which is to say, it is defined in relation to non-white others. This emphasis on relationality isn’t likely to be a huge surprise to many people of color; they’ve always understood their identities to be defined in relation to a mainstream American identity that is always presumed to be white.

------------------

Let’s get deeper into the book itself.

First off, Morrison mentions jazz at the very beginning of the book, with reference to a passage in Marie Cardinal’s novel The Words to Say It . There, the music of Louis Armstrong precipitates a psychic crisis in the narrator: “Gripped by panic at the idea of dying there in the middle of spasms, stomping feet, and the crowd howling, I ran into the street like someone possessed.” Toni Morrison goes on to provide a series of remarkably compelling readings of as she puts it, “the way black people ignite critical moments of discovery or change or emphasis in literature not written by them.”

What Africanism became for, and how it functioned in, the literary imagination is of paramount interest because it may be possible to discover, through a close look at literary ‘blackness,’ the nature--even the cause--of literary ‘whiteness.’ (Morrison, 9)

The kind of reading method Morrison employs in her book is what some critics would call dialectical reading (Edward Said would describe it, using musical terminology as “contrapuntal.”) She sees Whiteness and Blackness as intertwined, as producing each other, in American life . Whiteness is a dominant, but it depends upon its subordinate to give it shape, even though it also aims to relegate its other to a position of marginality and partial erasure. Sometimes the marginalization is direct and obvious (as she shows happening in Hemingway’s To Have and Have Not : the Black character on the boat to whom Hemingway refuses to grant agency). At other times, the connection is more associative -- requiring the critic to fill in gaps left by authors whose failure to grant full subjectivity to their Black characters is symptomatic (a great example of this more associative reading method might be with Morrison’s account of Willa Cather’s Sapphira and the Slave Girl ).

Later in the Preface, she writes:

The principal reason these matters loom large for me is that I do not have quite the same access to these traditionally useful constructs of blackness. Neither blackness nor ‘people of color’ stimulates in me notions of excessive, limitless love, anarchy, or routine dread. I cannot rely on these metaphorical shortcuts because I am a black writer struggling with and through a language that can powerfully evoke and enforce hidden signs of racial superiority, cultural hegemony, and dismissive ‘othering’ of people and language which are by no means marginal or already and completely known and knowable in my work. My vulnerability would lie in romanticizing blackness rather than demonizing it; vilifying whiteness rather than reifying it. The kind of work I have always wanted to do requires me to learn how to maneuver ways to free up the language from its sometimes sinister, frequently lazy, almost always predictable employment of racially informed and determined chains. (Preface, x-xi)

Here, Morrison is writing herself into the story. She sees the ways white writers use blackness as tending towards “metaphorical shortcuts” rather than substantive engagements, as in effect providing a useful set of tropes for those writers rather than a serious point of exploration. I’m also interested in the point where she acknowledges that the danger for a Black writer might lie in “romanticizing Blackness”; here I think she must be referring to what in the 1970s and 80s was called Afrocentric or Black nationalist thinking, and she’s clearly distancing herself from that approach as well. Finally, it’s telling that she always brings it back to language, and she maintains what seems like considerable humility in her engagements on that front.

A final passage from the Preface we might want to consider:

For reasons that should not need explanation here, until very recently, and regardless of the race of the author, the readers of virtually all of American fiction have been positioned as white. I am interested to know what that assumption has meant to the literary imagination. When does racial ‘unconsciousness’ or awareness of race enrich interpretive language, and when does it impoverish it? What does positing one’s writerly self, in the wholly racialized society that is the United States, as unraced and all others as raced entail? What happens to the writerly imagination of a black author who is at some level always conscious of representing one’s own race to, or in spite of, a race of readers that understands itself to be ‘universal’ or race-free? In other words, how is ‘literary whiteness’ and ‘literary blackness’ made, and what is the consequence of that construction? [...] Living in a nation of people who decided that their world view would combine agendas for individual freedom and mechanisms for devastating racial oppression presents a singular landscape for a writer. (Preface, xii-xiii)

Here, Morrison aims to put forward the centrality of race as a topic, and suggest that all of us are implicated in it -- that the construction of an “unraced” reader is a deliberate act. That unraced subject was in fact, she states, “presumed to be white.” Morrison is asking what the consequences might be of, as it were, erasing race, but she is also clearly gesturing towards how we might reinsert it. It might be a little uncomfortable at first to say that Melville and Emerson were white American writers interested in whiteness (and sometimes Blackness), but it is more honest and also potentially more inclusive to do so.

Another key foundational passage from section 1, “Black matters”:

For some time now I have been thinking about the validity or vulnerability of a certain set of assumption conventionally accepted among literary historians and critics and circulated as ‘knowledge.’ This knowledge holds that traditional, canonical American literature is free of, uninformed, and unshaped by the four hundred-year-old presence of, first Africans and then African-Americans in the United States. It assumes that this presence--which shaped the body politic, the Constitution, and the entire history of the culture--has had no significant place or consequence in the origin and development of that culture’s literature. Moreover, such knowledge assumes that the characteristics of our national literature emanate from a particular ‘Americanness’ that is separate from and unaccountable to this presence. [...] The contemplation of this black presence is central to any understanding of our national literature and should not be permitted to hover at the margins of the literary imagination. ( 4-5)

This passage does two things that seem important to underline. First is the way Morrison is frontally challenging a way of thinking that had been accepted as uncontroversially true -- a mode of “factual” knowledge about American literature rather than a constructed argument. What she’s saying in this book would require some people to realize that a good deal of what they had previously thought and said about American authors and American national culture was much more open to challenge than they had probably expected. Second, she’s helping to introduce the idea of the “Africanist presence" she will be referring to throughout the book. She’s clearly interested in the Africanist presence as being both African (especially in the early literature, when many enslaved Black people were either recently brought over from Africa or recently descended from Africans) and eventually in its emergence as African American .

She continues to unpack “American Africanism” on pages 6 and 7. Here is a bit more on the “Africanism” mentioned above:

I am using the term ‘ Africanism ’ not to suggest the larger body of knowledge on Africa that the philosopher Valentin Mudimbe means by the term ‘Africanism,’ nor to suggest the varieties and complexities of African people and their descendants who have inhabited this country. Rather I use it as a term for the denotative and connotative blackness that African peoples have come to signify, as well as the entire range of views, assumptions, readings, and misreadings that accompany Eurocentric learning about these people. (6-7)

It’s safe to say that in many cases, when Morrison uses the term ‘Africanism’ she means it as synonymous with ‘Black’. I do think she’s interested in the ways there are residual echoes and reverberations of African culture and expressive language that have remained with Black folks in the U.S. long after knowledge of African languages disappeared. Some of her novels show us this -- it’s in the connection of ancestor Solomon to Africa in Song of Solomon , or Sethe’s mother and ‘Nan’ in Beloved , who are shown speaking another language at the beginning of the novel -- it seems like they’ve been recently transported to the U.S. (See our overviews of these novels here .)

Another important passage: the subject of the dream is the dreamer:

How does literary utterance arrange itself when it tries to imagine an Africanist other? What are the signs, the codes, the literary strategies designed to accommodate this encounter? What does the inclusion of Africans or African-Americans do to and for the work? As a reader my assumption had always been that nothing “happens”: Africans and their descendants were not, in any sense that matters, there; and when they were there, they were decorative—displays of the agile writer’s technical expertise. I assumed that since the author was not black, the appearance of Africanist characters or narrative or idiom in a work could never be about anything other than the “normal,” unracialized, illusory white world that provided the fictional backdrop. Certainly no American text of the sort I am discussing was ever written for black people—no more than Uncle Tom’s Cabin was written for Uncle Tom to read or be persuaded by. As a writer reading, I came to realize the obvious: the subject of the dream is the dreamer. The fabrication of an Africanist persona is reflexive; an extraordinary meditation on the self; a powerful exploration of the fears and desires that reside in the writerly conscious. It is an astonishing revelation of longing, of terror, of perplexity, of shame, of magnanimity. It requires hard work not to see this. (16-17)

This is a huge breakthrough. In my words: when white writers write about Black people as marginal characters, Morrison isn’t necessarily asking us to invert the paradigm and see those characters as somehow central or definitive (though sometimes they might be). Rather, the construction of racialized others in texts by white writers tells us something about the construction of whiteness in those texts: "the subject of the dream is the dreamer."

I might also note that Morrison’s move here is remarkably parallel to what Edward Said notes in Orientalism with respect to western conceptions of non-western cultures. When American writers construct a discourse of Africanism in their works, they are constructing an inverted mirror -- a fantasy of otherness. They are not, by and large, actually incorporating the actual voices and narratives of people of African descent. When British writers like H. Rider Haggard or Joseph Conrad dreamed of “savages” in sub-Saharan Africa, they were not seeing and hearing real African people; they were imagining an Other to themselves said more about their fantasies than it did to the ethnographic reality of the people they were ostensibly encountering along the Nile or the Congo. (See our introduction to key concepts in Orientalism here .)

-------------------

The next section of “Black Matters” deals with Willa Cather’s Sapphira and the Slave Girl , which as Morrison acknowledges is not a novel of Cather’s people tend to talk about much. Why and how does it fail? What is it about the story that’s unsatisfying?

For Morrison, some of it at least is the way Cather can’t come up with a realistic imagining of either of the major Black characters in the story, Nancy (the daughter) or Til (the mother). She’s particularly blank on Til, whose maternal concern for her daughter who has disappeared is reduced to a single opportunity to ask a question about whether her daughter has made it safely to Canada. Morrison encapsulates her frustration with Cather’s failure of imagination in the following paragraphs:

Rendered voiceless, a cipher, a perfect victim, Nancy runs the risk of losing the reader’s interest. In a curious way, Sapphira’s plotting, like Cather’s plot, is without reference to the characters and exists solely for the ego-gratification of the slave mistress. This becomes obvious when we consider what would have been the consequences of a successful rape. Given the novel’s own terms, there can be no grounds for Sapphira’s thinking that Nancy can be “ruined” in the conventional sense. There is no question of marriage to Martin, to Colbert, to anybody. Then, too, why would such an assault move her slave girl outside her husband’s interest? The probability is that it would secure it. If Mr. Colbert is tempted by Nancy the chaste, is there anything in slavocracy to make him disdain Nancy the unchaste? Such a breakdown in the logic and machinery of plot construction implies the powerful impact race has on narrative—and on narrative strategy. Nancy is not only the victim of Sapphira’s evil, whimsical scheming. She becomes the unconsulted, appropriated ground of Cather’s inquiry into what is of paramount importance to the author: the reckless, unabated power of a white woman gathering identity unto herself from the wholly available and serviceable lives of Africanist others. This seems to me to provide the coordinates of an immensely important moral debate. (24-25)

The key parts for me are in bold above. I do think Morrison is seeing a slippage between the contrivances of Sapphira in the novel and the contrivances of the author: both are white women “gathering identity unto [themselves] from the wholly available and serviceable lives of Africanist others.”

Section 2: “Romancing the Shadow”

This section starts with an account of an Edgar Allen Poe story , The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym , where the death of an African in a stranded boat leads to the apparition of a giant white ghost. The particularities of the reading of this particular story might not be essential for us to grasp: Morrison quickly pivots to an account of early American literature more generally:

Young America distinguished itself by, and understood itself to be, pressing toward a future of freedom, a kind of human dignity believed unprecedented in the world. A whole tradition of “universal” yearnings collapsed into that well-fondled phrase, “the American Dream.” Although this immigrant dream deserves the exhaustive scrutiny it has received in the scholarly disciplines and the arts, it is just as important to know what these people were rushing from as it is to know what they were hastening to. If the New World fed dreams, what was the Old World reality that whetted the appetite for them? And how did that reality caress and grip the shaping of a new one? The flight from the Old World to the New is generally seen to be a flight from oppression and limitation to freedom and possibility. Although, in fact, the escape was sometimes an escape from license—from a society perceived to be unacceptably permissive, ungodly, and undisciplined—for those fleeing for reasons other than religious ones, constraint and limitation impelled the journey. All the Old World offered these immigrants was poverty, prison, social ostracism, and, not infrequently, death. There was of course a clerical, scholarly group of immigrants who came seeking the adventure possible in founding a colony for, rather than against, one or another mother country or fatherland. And of course there were the merchants, who came for the cash. Whatever the reasons, the attraction was of the “clean slate” variety, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity not only to be born again but to be born again in new clothes, as it were. The new setting would provide new raiments of self. This second chance could even benefit from the mistakes of the first. In the New World there was the vision of a limitless future, made more gleaming by the constraint, dissatisfaction, and turmoil left behind. It was a promise genuinely promising. With luck and endurance one could discover freedom; find a way to make God’s law manifest; or end up rich as a prince. The desire for freedom is preceded by oppression; a yearning for God’s law is born of the detestation of human license and corruption; the glamor of riches is in thrall to poverty, hunger, and debt. (33-35)

There’s nothing here that’s very controversial -- these are claims that would be widely accepted as an uncontroversial account of the emergence of the “American mind” -- one of the key facets of American culture. Rugged individualism, egalitarianism, room for free thought and an unconventional orientation to society (i.e., the American tradition of freethinking non-conformism).

The example she gives of this in the subsequent pages, the story of William Dunbar as recounted in a book called Voyagers to the West , which turns out to be pretty jaw-dropping. Dunbar came from Scotland, immigrated to the early U.S., and maintained a plantation in Mississippi with a number of Black Caribbean slaves. When those slaves rebelled against his authority, he had them beaten -- brutally (four sets of 500 lashes). He was also known as an extremely learned man with thoughts on the new American democratic experiment, a member of the Philosophical society, well-respected by people like Thomas Jefferson .

For Morrison, there is no contradiction here: this is it. Here is her take on how this image of Dunbar seems to perfectly encapsulate the contradiction at the heart of the construction of (white) Americanness:

I take this to be a succinct portrait of the process by which the American as new, white, and male was constituted. It is a formation with at =least four desirable consequences, all of which are referred to in Bailyn’s summation of Dunbar’s character and located in how Dunbar felt “within himself.” Let me repeat: “a sense of authority and autonomy he had not known before, a force that flowed from his absolute control over the lives of others, he emerged a distinctive new man, a borderland gentleman, a man of property in a raw, half-savage world.” A power, a sense of freedom, he had not known before. But what had he known before? Fine education, London sophistication, theological and scientific thought. None of these, one gathers, could provide him with the authority and autonomy that Mississippi planter life did. Also this sense is understood to be a force that flows, already present and ready to spill as a result of his “absolute control over the lives of others.” This force is not a willed domination, a thought-out, calculated choice, but rather a kind of natural resource, a Niagara Falls waiting to drench Dunbar as soon as he is in a position to assume absolute control. Once he has moved into that position, he is resurrected as a new man, a distinctive man—a different man. And whatever his social status in London, in the New World he is a gentleman. More gentle, more man. The site of his transformation is within rawness: he is backgrounded by savagery. (43-44)

Here’s another passage from Morrison that speaks to this more oblique mode of reading:

Explicit or implicit, the Africanist presence informs in compelling and inescapable ways the texture of American literature. It is a dark and abiding presence, there for the literary imagination as both a visible and an invisible mediating force. Even, and especially, when American texts are not ‘about’ Africanist presences or characters or narrative or idiom, the shadow hovers in implication, in sign, in line of demarcation. It is no accident and no mistake that immigrant populations (and much immigrant literature) understood their ‘Americanness’ as an opposition to the resident black population. Race, in fact, now functions as a metaphor so necessary to the construction of Americanness that it rivals the old pseudo-scientific and class-informed racisms whose dynamics we are more used to deciphering. (Morrison, 46-47)

It’s in passages like these that one gets a hint of the ambition and scope of this argument -- it goes to the core of the construction of Americanness itself. One way for critics to try and prove her assertion (in such a short book I think we have to take her readings as suggestive rather than as proven by evidence) might be to go deeper into the ways in which what she calls the Africanist other was a constitutive presence and absence from other works in the American canon. (And since this book was published American literature scholars have been doing this, in a growing sub-field focused on “whiteness studies.” )

--Amardeep Singh, Professor of English. Lehigh University. April 2021 Feel free to email me with questions or comments: amsp [at] lehigh [dot] edu

This page has paths:

This page references:.

- 1 media/Playing in the dark_thumb.jpeg 2021-09-19T08:24:18-04:00 Playing in the Dark Cover 1 Cover of Toni Morrison's Playing in the Dark media/Playing in the dark.jpeg plain 2021-09-19T08:24:18-04:00

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — American Literature — Review of “Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination” by Toni Morrison

Review of "Playing in The Dark: Whiteness and The Literary Imagination" by Toni Morrison

- Categories: American Literature Literary Criticism

About this sample

Words: 353 |

Published: Mar 1, 2019

Words: 353 | Page: 1 | 2 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 660 words

3 pages / 1334 words

2 pages / 1063 words

4 pages / 1709 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on American Literature

The Great Gatsby, a novel written by F. Scott Fitzgerald, is a work of literature that delves into the decadence and moral decay of the American Dream during the 1920s. The focus of the essay is on the novel's tone, which is [...]

UNESCO. (2015). UNESCO World Book Capital Cities: 2001-2018. Retrieved from Press.

The Lottery by Shirley Jackson is a widely recognized short piece of literature in the United States. Published in 1948, it quickly gained popularity due to its psychological aspects. In this analysis essay, we will delve into [...]

America's literary landscape has been shaped by a diverse range of historical, cultural, and social influences, which have in turn reflected and impacted the nation's evolving identity. This essay aims to explore the historical [...]

'Lust' by Susan Minot creates and brings out the main character of the story in a unique manner. This short story by Minot has many of the elements throughout the story, for example her sexual escapades with different boys set [...]

The novel “Chasing Lincoln’s Killer”, by James Swanson, is about the plotting and killing of President Lincoln; the twelve-day manhunt of John Wilkes Booth. Booth is the murderer of The United States 16th President, Abraham [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination

25 pages • 50 minutes read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Key Figures

Symbols & Motifs

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Morrison thinks that literary critics have long ignored the Africanist presence in American literature . Do you agree or disagree? Use textual evidence to support your position.

What does Morrison mean by “Africanism?” What does it refer to?

According to Morrison, what were the difficulties presented by early American self-definitions?

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By Toni Morrison

Toni Morrison

God Help The Child

Love: A Novel

Song of Solomon

The Bluest Eye

The Origin of Others

Featured Collections

Essays & Speeches

View Collection

Nobel Laureates in Literature

Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination

Author: Toni Morrison Edition: Paperback, 1993 Date Read: September 13, 2020

Toni Morrison’s brilliant discussions of the “Africanist” presence in the fiction of Poe, Melville, Cather, and Hemingway leads to a dramatic reappraisal of the essential characteristics of our literary tradition. She shows how much the themes of freedom and individualism, manhood and innocence, depended on the existence of a black population that was manifestly unfree –and that came to serve white authors as embodiments of their own fears and desires.

Written with the artistic vision that has earned Toni Morrison a pre-eminent place in modern letters, Playing in the Dark will be avidly read by Morrison admirers as well as by students, critics, and scholars of American literature( goodreads.com ).

Should Lit Girls read it?

Everyone should read it! Playing in the Dark is an important book and exceedingly relevant in these times. It will change the way you read and think about your favorite stories; and that can only be positive.

Lit Girls Take:

In Playing in the Dark, Toni Morrison presents a collection of essays adapted from a lectureship she hosted at Harvard in 1990. Reading this book was like sitting through the most interesting and enlightening English class ever.

Throughout this book Morrison looks critically at the role race has played in shaping American literature. From Poe to Hemingway, she illustrates the way race has been used as a tool for American authors and it’s repercussions on our literary culture. Certainly, I cannot say that I was truly able to understand all the nuance of Morrison’s points. For one thing, It has been some time since I attended anything close to an academic lecture. Subsequently, I have not read any of the texts she references so much of this writing went over my head. However, her explanations of the presence of the Africanist persona in “classic” works was nothing short of revelatory.

Perhaps the most interesting take away from these essays was Morrisons’ dissection of the many critiques of these works. The literal and metaphorical representation of race is immensely important in these books. However, its absence from the critiques was enlightening. That says just as much about the critics as it does about the authors, and the larger social climate that influenced their writing. Still, Morrison never discounts the talent of these authors. Similarly, she doesn’t question the worthiness of these books to be counted amongst the classics.

Her argument here is that any reading of these stories need to include a discussion on race. Furthermore, race must be part of the conversation and to leave it out would somehow make the reading incomplete. In other words, we must continue to have conversations about race; and the role race has and continues, to play in our cultural development cannot be written off. Including race in the analysis of classic literature in no way diminishes them. In my opinion, to include race in one’s reading would only enhance the literary experience.

Recently, I have been struggling to better understand the subtle ways in which race is used in our culture. Other than reading stories about experiences different from my own, I was not sure how to proceed. However, thanks to Toni Morrison, I now have a place to start. She has given me the tools to look more critically on all literature, classic and contemporary. Morrison has changed my literary experience. For anyone claiming to be a student of literature, or even just a book nerd, Playing in the Dark is an immensely important piece. For every Lit Girl, this is a must read.

You May Also Like

Life and Death: Twilight Reimagined

A Promised Land

In The Heights: Finding Home

Authors & Events

Recommendations

- New & Noteworthy

- Bestsellers

- Popular Series

- The Must-Read Books of 2023

- Popular Books in Spanish

- Coming Soon

- Literary Fiction

- Mystery & Thriller

- Science Fiction

- Spanish Language Fiction

- Biographies & Memoirs

- Spanish Language Nonfiction

- Dark Star Trilogy

- Ramses the Damned

- Penguin Classics

- Award Winners

- The Parenting Book Guide

- Books to Read Before Bed

- Books for Middle Graders

- Trending Series

- Magic Tree House

- The Last Kids on Earth

- Planet Omar

- Beloved Characters

- The World of Eric Carle

- Llama Llama

- Junie B. Jones

- Peter Rabbit

- Board Books

- Picture Books

- Guided Reading Levels

- Middle Grade

- Activity Books

- Trending This Week

- Top Must-Read Romances

- Page-Turning Series To Start Now

- Books to Cope With Anxiety

- Short Reads

- Anti-Racist Resources

- Staff Picks

- Memoir & Fiction

- Features & Interviews

- Emma Brodie Interview

- James Ellroy Interview

- Nicola Yoon Interview

- Qian Julie Wang Interview

- Deepak Chopra Essay

- How Can I Get Published?

- For Book Clubs

- Reese's Book Club

- Oprah’s Book Club

- happy place " data-category="popular" data-location="header">Guide: Happy Place

- the last white man " data-category="popular" data-location="header">Guide: The Last White Man

- Authors & Events >

- Our Authors

- Michelle Obama

- Zadie Smith

- Emily Henry

- Amor Towles

- Colson Whitehead

- In Their Own Words

- Qian Julie Wang

- Patrick Radden Keefe

- Phoebe Robinson

- Emma Brodie

- Ta-Nehisi Coates

- Laura Hankin

- Recommendations >

- 21 Books To Help You Learn Something New

- The Books That Inspired "Saltburn"

- Insightful Therapy Books To Read This Year

- Historical Fiction With Female Protagonists

- Best Thrillers of All Time

- Manga and Graphic Novels

- happy place " data-category="recommendations" data-location="header">Start Reading Happy Place

- How to Make Reading a Habit with James Clear

- Why Reading Is Good for Your Health

- 10 Facts About Taylor Swift

- New Releases

- Memoirs Read by the Author

- Our Most Soothing Narrators

- Press Play for Inspiration

- Audiobooks You Just Can't Pause

- Listen With the Whole Family

Playing In The Dark

Whiteness and the Literary Imagination

By Toni Morrison

By toni morrison read by bahni turpin, category: literary criticism, category: literary criticism | audiobooks.

Jul 27, 1993 | ISBN 9780679745426 | 5-3/16 x 8 --> | ISBN 9780679745426 --> Buy

Jul 24, 2007 | ISBN 9780307388636 | ISBN 9780307388636 --> Buy

May 05, 2020 | 190 Minutes | ISBN 9780593216668 --> Buy

Buy from Other Retailers:

Jul 27, 1993 | ISBN 9780679745426

Jul 24, 2007 | ISBN 9780307388636

May 05, 2020 | ISBN 9780593216668

190 Minutes

Buy the Audiobook Download:

- audiobooks.com

About Playing In The Dark

An immensely persuasive work of literary criticism that opens a new chapter in the American dialogue on race—and promises to change the way we read American literature — from the acclaimed Nobel Prize winner Morrison shows how much the themes of freedom and individualism, manhood and innocence, depended on the existence of a black population that was manifestly unfree –and that came to serve white authors as embodiments of their own fears and desires. According to the Chicago Tribune , Morrison “reimagines and remaps the possibility of America.” Her brilliant discussions of the “Africanist” presence in the fiction of Poe, Melville, Cather, and Hemingway leads to a dramatic reappraisal of the essential characteristics of our literary tradition. Written with the artistic vision that has earned the Nobel Prize-winning author a pre-eminent place in modern letters, Playing in the Dark is an invaluable read for avid Morrison admirers as well as students, critics, and scholars of American literature.

Listen to a sample from Playing In The Dark

Also by toni morrison.

About Toni Morrison

TONI MORRISON is the author of eleven novels and three essay collections. She received the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Pulitzer Prize, and in 1993 the Nobel Prize in Literature. She died in 2019.

Product Details

You may also like.

The Souls of Black Folk

The Devil Finds Work

The Log from the Sea of Cortez

Journal of a Novel

Let Me Tell You What I Mean

Hemingway’s Boat

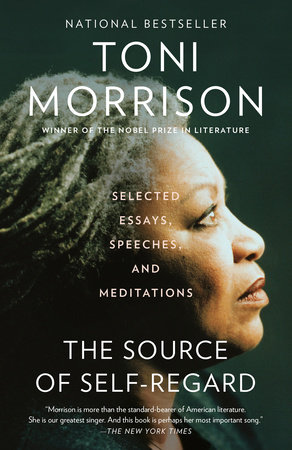

The Source of Self-Regard

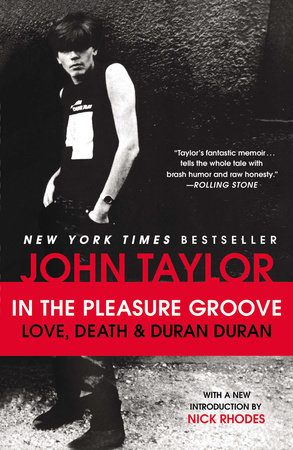

In the Pleasure Groove

“A profound redefinition of American cultural identity.”–Philadelphia Inquirer “By going for the American literary jugular…she places her arguments…at the very heart of contemporary public conversation about what it is to be authentically and originally American. [She] boldly…reimagines and remaps the possibility of America.” –Chicago Tribune “Toni Morrison is the closest thing the country has to a national writer.” — The New York Times Book Review

Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (1992)

From the book racism in america.

- Toni Morrison

- X / Twitter

Supplementary Materials

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

Chapters in this book (27)

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Playing in the dark: whiteness and the literary imagination

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

Obscured text on front cover due to sticker attached.

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

26 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station03.cebu on August 20, 2022

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

- Study Guides

- Homework Questions

Final Video Essay Script willem berry

- Arts & Humanities

The Definitive Voice of Entertainment News

Subscribe for full access to The Hollywood Reporter

site categories

Breaking news, disney declares victory in proxy fight as nelson peltz fails to win board seat, critic’s notebook: beyoncé’s ‘cowboy carter’ is haunted by ghosts of rejection.

The music superstar's latest studio album, the second act of a planned trilogy, addresses detractors while doubling down on her country roots.

By Lovia Gyarkye

Lovia Gyarkye

Arts & Culture Critic

- Share this article on Facebook

- Share this article on Twitter

- Share this article on Flipboard

- Share this article on Email

- Show additional share options

- Share this article on Linkedin

- Share this article on Pinit

- Share this article on Reddit

- Share this article on Tumblr

- Share this article on Whatsapp

- Share this article on Print

- Share this article on Comment

In November 2016, at the 50th annual Country Music Association Awards, Beyoncé performed “Daddy Lessons,” her first explicit foray into country music. On the emotionally intimate, vervy album Lemonade , the song felt inspired by the singer’s Southern origins. Onstage, accompanied by The Chicks and a band wielding the full power of acoustic guitars, horns and harmonicas, it became a full-throated declaration — an affirmation of all that came with Beyoncé’s roots in Alabama, Louisiana and Texas.

Related Stories

Lizzo clarifies she's not quitting music: "i quit giving any negative energy attention", travis kelce on kelce jam and what he learned from taylor swift about live events: "enjoy the people".

Cowboy Carter , Beyoncé’s eighth studio album, confronts these snubs with a wholesale refusal of genre. Although the Americana fantasy is the second installment of the artist’s planned trilogy, she recorded the 27-track project before Renaissance , her boisterous ode to dance music, released in 2022.

The gritty defiance of a woman scorned runs through parts of Cowboy Carter . With this album, Beyoncé tries to build a regenerative narrative around the CMA controversy and Grammy snub. But she can’t shake the ghosts of those rebuffs long enough to let the project soar to the heights of Renaissance or lean into the contradictions that made Lemonade so visceral.

The album opens with a cursory elegy to America’s broken promises and the singer positioning herself as a divine heroine: “I am the one to cleanse me of my Father’s sins,” she declares at the end of “Ameriican Requiem.” She closes with a similarly lamenting verse on “Amen.”

Cowboy Carter , a project more than five years in the making, is tense with competing desires and haunted by the sting of the musician’s institutional rejection: It can feel like defensive posturing couched in righteous reclamation.

There are glimpses of Beyoncé’s frustration, which lends itself to a handful of seductively cocksure and thrillingly disobedient tracks, “Riiverdance,” “II Hands II Heaven,” “Tyrant” and “Sweet Honey Buckiin’” among them. On these songs Beyoncé, a zealous student of craft, bends genre to her will, flaunting her deep appreciation of country, hip-hop and dance to create the funkiest chapter on Cowboy Carter . The crisp transitions and jolting vocal layering are some of her best.

But there are moments when she capitulates to the same forces for approval. On songs like “Bodyguard” and “Levii’s Jeans,” she channels contemporary country, but she also sounds bored while doing it. Those songs function as inoffensive window dressing. What does it mean that an artist of Beyoncé’s stature still feels compelled to vie for institutional recognition? What does it say about the people who need her to?

Renaissance was a bouncy intra-community conversation honoring the Black queer roots of house, disco and techno music within the walls of the artist’s imagined club. Everyone was invited, but Beyoncé seemed to find personal liberation — stretching the bounds of voice as instrument, experimenting with production — in that fictive communion.

Cowboy Carter addresses her detractors and most of the album is weighted by this bid to disprove them. There’s less room for the artist’s imagination unmediated by those ghosts. It makes the handful of moments of explicit Black country music inclusion, like “Blackbiird,” a cover of The Beatles’ Civil Rights-inspired lamentation featuring Adell, Spencer, Kennedy and Roberts, falter when they should lift the spirit.

These artists are mostly relegated to the background, a missed opportunity to harness the power of their voices and to underscore their respective contributions to country music’s fraught terrain. That Post Malone and Miley Cyrus are offered more room is disappointing considering Beyoncé’s call on “Ameriican Requiem” to take up space.

As she did in her CMA performance, the singer doubles down on belonging by claiming her cultural and national heritage. She is surrounded by a dark nothingness, but here I imagine the ghosts are not too far off. They haunt the edges of the cover and the pastoral image of America projected throughout Cowboy Carter . She addresses them directly on “Ameriican Requiem.” “Can you hear me,” she asks. “Or do you fear me?”

The battle has been staged between Beyoncé and the specters; that she will join the struggle to cleanse the nation of its sins feels like merely an afterthought.

THR Newsletters

Sign up for THR news straight to your inbox every day

More from The Hollywood Reporter

While patti lupone vows she’ll never do another musical, she is singing soon onstage in l.a., christopher durang, playwright and tony winner for ‘vanya and sonia and masha and spike,’ dies at 75, women’s march madness 2024: how to watch the ncaa final four online without cable, march madness tournament 2024: where to watch men’s ncaa final four basketball online, ryan o’connell to release essay collection (exclusive), jim parsons, katie holmes, zoey deutch to star in ‘our town’ revival on broadway.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Toni Morrison's "Playing in the Dark" (2007): Overview. Note: This overview started as teaching notes, which I created for a class called "Theories of Literature and Social Justice." An earlier version of this essay can be found here. --Amardeep Singh, April 2021 Toni Morrison was a groundbreaking figure in multiple fields -- as a novelist of ...

for only $0.70/week. Subscribe. Thanks for exploring this SuperSummary Study Guide of "Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination" by Toni Morrison. A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and ...

Reading Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, Toni Morrison thoughtfully explores the importance of African Americans in the American literary imagination. Morrison shares her concerns with American language and the American literary imagination being both characteristically white, and questions the impact of this whiteness upon American writers.

Playing in the Dark. Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination is a 1992 work of literary criticism by Toni Morrison. In it she develops a reading of major white American authors and traces the way their perceptions of blackness gave defining shape to their works, and thus to the American literary canon.

So begins Toni Morrison's essay, Playing in the Dark. Morrison's map is divided into three sections. The first, "Black Matters," begins with criticism of the American literary canon -- or, as Morrison calls it, "a certain set of assumptions conventionally accepted among literary critics and historians and circulated as "knowledge ...

Nobel Laureates in Literature. Thanks for exploring this SuperSummary Study Guide of "Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination" by Toni Morrison. A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

In Playing in the Dark, Toni Morrison presents a collection of essays adapted from a lectureship she hosted at Harvard in 1990. Reading this book was like sitting through the most interesting and enlightening English class ever. Throughout this book Morrison looks critically at the role race has played in shaping American literature.

In Toni Morrison. A work of criticism, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination, was published in 1992.Many of Morrison's essays and speeches were collected in What Moves at the Margin: Selected Nonfiction (2008; edited by Carolyn C. Denard) and The Source of Self-Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches, and Meditations…. Read More

/// this is what ya'll should be reading instead /// Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination is a 1992 work of literary criticism by Toni Morrison. In 1990, Morrison delivered a series of three lectures at Harvard University; she then adapted the texts to a 91-page book consisting of three essays of metacritical explorations into the operations of whiteness and blackness in ...

Playing In The Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination. Toni Morrison. National Geographic Books, Jul 27, 1993 - Literary Criticism - 112 pages. An immensely persuasive work of literary criticism that opens a new chapter in the American dialogue on race—and promises to change the way we read American literature—from the acclaimed Nobel ...

About Playing In The Dark. An immensely persuasive work of literary criticism that opens a new chapter in the American dialogue on race—and promises to change the way we read American literature—from the acclaimed Nobel Prize winner Morrison shows how much the themes of freedom and individualism, manhood and innocence, depended on the existence of a black population that was manifestly ...

Remove the name "Toni Morrison," however, and PLAYING IN THE DARK would be an unlikely best-seller indeed. For some time now, literary critics have assiduously been exploring the impact of ...

Toni Morrison's Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination is a seminal piece of literary criticism, and a masterclass in the critical thinking skill of interpretation.. Interpretation plays a vital role in critical thinking: it focuses on interrogating accepted meanings and laying down clear definitions on which a strong argument can be built.

In 1990 Toni Morrison delivered the William E. Massey Lectures in the History of American Civilization. The lecture series was revised and published in May 1992 as a slim volume titled Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination. The three essays are metacritical explorations into the operations of whiteness and blackness in the ...

Playing in the Dark. Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Toni Morrison brings the genius of a master writer to this personal inquiry into the significance of African-Americans in the American literary imagination. Her goal, she states at the outset, is to "put forth an argument for extending the study of American literature…draw a map, so to ...

Terrifying, comic, ribald and tragic, Sula is a work that overflows with life. Playing in the Dark Vintage A beautiful, arresting short story by Toni Morrison—the only one she ever wrote—about race and the relationships that shape us through life, with an introduction by Zadie Smith. Twyla and.

Playing in the Dark. Toni Morrison. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, Jul 24, 2007 - Literary Criticism - 112 pages. An immensely persuasive work of literary criticism that opens a new chapter in the American dialogue on race—and promises to change the way we read American literature—from the acclaimed Nobel Prize winner Morrison shows how ...

An immensely persuasive work of literary criticism that opens a new chapter in the American dialogue on race—and promises to change the way we read American literature—from the acclaimed Nobel Prize winnerMorrison shows how much the themes of freedom and individualism, manhood and innocence, depended on the existence of a black population that was manifestly unfree--and that came to serve ...

Morrison, Toni. "Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (1992)" In Racism in America: A Reader, 1-9.Cambridge, MA and London, England: Harvard University Press, 2020.

Toni Morrison. Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1992. 112 pp. $14.95. In "Blueprint for Black Studies and Multiculturalism," Manning Marable declares that "African American Studies is at the edge of a second Renaissance, a new level of growth, institutionalization and theoretical advancement" (30).

Oct 2023. Yolanda E. McFerrin-Surrency. Delores D. Liston. View. Show abstract. PDF | On Dec 31, 2020, Toni Morrison published Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (1992 ...

Playing in the dark: whiteness and the literary imagination by Toni morrison. Publication date 1938 Publisher Harvard university press Collection printdisabled; internetarchivebooks Contributor Internet Archive Language English. Notes. Obscured text on front cover due to sticker attached.

Final Video Essay Script In Toni Morrison's novel, Song of Solomon, she uses a postcolonial criticism lens to discuss historical values, cultural identities, and social constructs to highlight the impact from colonialism and slavery on African American communities. Through Morrisons writing we see themes of identity, culture and the continuous legacy of colonialism.

She is surrounded by a dark nothingness, but here I imagine the ghosts are not too far off. They haunt the edges of the cover and the pastoral image of America projected throughout Cowboy Carter ...