- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Teen depression

Teen depression is a serious mental health problem that causes a persistent feeling of sadness and loss of interest in activities. It affects how your teenager thinks, feels and behaves, and it can cause emotional, functional and physical problems. Although depression can occur at any time in life, symptoms may be different between teens and adults.

Issues such as peer pressure, academic expectations and changing bodies can bring a lot of ups and downs for teens. But for some teens, the lows are more than just temporary feelings — they're a symptom of depression.

Teen depression isn't a weakness or something that can be overcome with willpower — it can have serious consequences and requires long-term treatment. For most teens, depression symptoms ease with treatment such as medication and psychological counseling.

Products & Services

- A Book: A Practical Guide to Help Kids of All Ages Thrive

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Teen depression signs and symptoms include a change from the teenager's previous attitude and behavior that can cause significant distress and problems at school or home, in social activities, or in other areas of life.

Depression symptoms can vary in severity, but changes in your teen's emotions and behavior may include the examples below.

Emotional changes

Be alert for emotional changes, such as:

- Feelings of sadness, which can include crying spells for no apparent reason

- Frustration or feelings of anger, even over small matters

- Feeling hopeless or empty

- Irritable or annoyed mood

- Loss of interest or pleasure in usual activities

- Loss of interest in, or conflict with, family and friends

- Low self-esteem

- Feelings of worthlessness or guilt

- Fixation on past failures or exaggerated self-blame or self-criticism

- Extreme sensitivity to rejection or failure, and the need for excessive reassurance

- Trouble thinking, concentrating, making decisions and remembering things

- Ongoing sense that life and the future are grim and bleak

- Frequent thoughts of death, dying or suicide

Behavioral changes

Watch for changes in behavior, such as:

- Tiredness and loss of energy

- Insomnia or sleeping too much

- Changes in appetite — decreased appetite and weight loss, or increased cravings for food and weight gain

- Use of alcohol or drugs

- Agitation or restlessness — for example, pacing, hand-wringing or an inability to sit still

- Slowed thinking, speaking or body movements

- Frequent complaints of unexplained body aches and headaches, which may include frequent visits to the school nurse

- Social isolation

- Poor school performance or frequent absences from school

- Less attention to personal hygiene or appearance

- Angry outbursts, disruptive or risky behavior, or other acting-out behaviors

- Self-harm — for example, cutting or burning

- Making a suicide plan or a suicide attempt

What's normal and what's not

It can be difficult to tell the difference between ups and downs that are just part of being a teenager and teen depression. Talk with your teen. Try to determine whether he or she seems capable of managing challenging feelings, or if life seems overwhelming.

When to see a doctor

If depression signs and symptoms continue, begin to interfere in your teen's life, or cause you to have concerns about suicide or your teen's safety, talk to a doctor or a mental health professional trained to work with adolescents. Your teen's family doctor or pediatrician is a good place to start. Or your teen's school may recommend someone.

Depression symptoms likely won't get better on their own — and they may get worse or lead to other problems if untreated. Depressed teenagers may be at risk of suicide, even if signs and symptoms don't appear to be severe.

If you're a teen and you think you may be depressed — or you have a friend who may be depressed — don't wait to get help. Talk to a health care provider such as your doctor or school nurse. Share your concerns with a parent, a close friend, a spiritual leader, a teacher or someone else you trust.

Suicide is often associated with depression. If you think you may hurt yourself or attempt suicide, call 911 or your local emergency number immediately.

Also consider these options if you're having suicidal thoughts:

- Call your mental health professional.

- In the U.S., call or text 988 to reach the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline , available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Or use the Lifeline Chat . The Spanish language phone line is 1-888-628-9454 (toll-free). Services are free and confidential.

- Or contact a crisis service for teenagers in the U.S. called TXT 4 HELP : Text the word "safe" and your current location to 4HELP (44357) for immediate help, with the option for interactive texting.

- Seek help from your primary care doctor or other health care provider.

- Reach out to a close friend or loved one.

- Contact a minister, spiritual leader or someone else in your faith community.

If a loved one or friend is in danger of attempting suicide or has made an attempt:

- Make sure someone stays with that person.

- Call 911 or your local emergency number immediately.

- Or, if you can do so safely, take the person to the nearest hospital emergency room.

Never ignore comments or concerns about suicide. Always take action to get help.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

It's not known exactly what causes depression, but a variety of issues may be involved. These include:

- Brain chemistry. Neurotransmitters are naturally occurring brain chemicals that carry signals to other parts of your brain and body. When these chemicals are abnormal or impaired, the function of nerve receptors and nerve systems changes, leading to depression.

- Hormones. Changes in the body's balance of hormones may be involved in causing or triggering depression.

- Inherited traits. Depression is more common in people whose blood relatives — such as a parent or grandparent — also have the condition.

- Early childhood trauma. Traumatic events during childhood, such as physical or emotional abuse, or loss of a parent, may cause changes in the brain that increase the risk of depression.

- Learned patterns of negative thinking. Teen depression may be linked to learning to feel helpless — rather than learning to feel capable of finding solutions for life's challenges.

Risk factors

Many factors increase the risk of developing or triggering teen depression, including:

- Having issues that negatively impact self-esteem, such as obesity, peer problems, long-term bullying or academic problems

- Having been the victim or witness of violence, such as physical or sexual abuse

- Having other mental health conditions, such as bipolar disorder, an anxiety disorder, a personality disorder, anorexia or bulimia

- Having a learning disability or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Having ongoing pain or a chronic physical illness such as cancer, diabetes or asthma

- Having certain personality traits, such as low self-esteem or being overly dependent, self-critical or pessimistic

- Abusing alcohol, nicotine or other drugs

- Being gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender in an unsupportive environment

Family history and issues with family or others may also increase your teenager's risk of depression, such as:

- Having a parent, grandparent or other blood relative with depression, bipolar disorder or alcohol use problems

- Having a family member who died by suicide

- Having a family with major communication and relationship problems

- Having experienced recent stressful life events, such as parental divorce, parental military service or the death of a loved one

Complications

Untreated depression can result in emotional, behavioral and health problems that affect every area of your teenager's life. Complications related to teen depression may include, for example:

- Alcohol and drug misuse

- Academic problems

- Family conflicts and relationship difficulties

- Suicide attempts or suicide

There's no sure way to prevent depression. However, these strategies may help. Encourage your teenager to:

- Take steps to control stress, increase resilience and boost self-esteem to help handle issues when they arise

- Practice self-care, for example by creating a healthy sleep routine and using electronics responsibly and in moderation

- Reach out for friendship and social support, especially in times of crisis

- Get treatment at the earliest sign of a problem to help prevent depression from worsening

- Maintain ongoing treatment, if recommended, even after symptoms let up, to help prevent a relapse of depression symptoms

Teen depression care at Mayo Clinic

- Depressive disorders. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. https://dsm.psychiatryonline.org. Accessed May 4, 2021.

- Bipolar and related disorders. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. https://dsm.psychiatryonline.org. Accessed May 4, 2021.

- Brown AY. Allscripts EPSi. Mayo Clinic. April 9, 2021.

- Teen depression. National Institute of Mental Health. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/teen-depression/. Accessed March 30, 2022.

- Depression in children and teens. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/The-Depressed-Child-004.aspx. Accessed May 4, 2021.

- Psychotherapy for children and adolescents: Different types. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Psychotherapies-For-Children-And-Adolescents-086.aspx. Accessed May 4, 2021.

- Suicidality in children and adolescents being treated with antidepressant medications. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/postmarket-drug-safety-information-patients-and-providers/suicidality-children-and-adolescents-being-treated-antidepressant-medications. Accessed May 4, 2021.

- Depression medicines. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/consumers/free-publications-women/depression-medicines. Accessed May 4, 2021.

- Building your resilience. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/resilience. Accessed May 4, 2021.

- Psychiatric medications for children and adolescents: Part I ― How medications are used. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Psychiatric-Medication-For-Children-And-Adolescents-Part-I-How-Medications-Are-Used-021.aspx. Accessed May 4, 2021.

- Psychiatric medications for children and adolescents: Part II ― Types of medications. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Families_and_Youth/Facts_for_Families/FFF-Guide/Psychiatric-Medication-For-Children-And-Adolescents-Part-II-Types-Of-Medications-029.aspx. Accessed May 5, 2021.

- Weersing VR, et al. Evidence-base update of psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2017; doi:10.1080/15374416.2016.1220310.

- Zuckerbrot RA, et al. Guidelines for adolescent depression in primary care (GLAD-PC): Part I. Practice preparation, identification, assessment, and initial management. Pediatrics. 2018; doi:10.1542/peds.2017-4081.

- Cheung AH, et al. Guidelines for adolescent depression in primary care (GLAD-PC): Part II. Treatment and ongoing management. Pediatrics. 2018; doi:10.1542/peds.2017-4082.

- Resilience guide for parents and teachers. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/topics/resilience/guide-parents-teachers. Accessed May 4, 2021.

- Rice F, et al. Adolescent and adult differences in major depression symptoms profiles. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2019; doi:10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.015.

- Haller H, et al. Complementary therapies for clinical depression: An overview of systemic reviews. BMJ Open. 2019; doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028527.

- Ng JY, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine recommendations for depression: A systematic review and assessment of clinical practice guidelines. BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapeutics. 2020; doi:10.1186/s12906-020-03085-1.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 92: Use of psychiatric medications during pregnancy and lactation. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2008; doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31816fd910. Reaffirmed 2019.

- Neavin DR, et al. Treatment of major depressive disorder in pediatric populations. Diseases. 2018; doi:10.3390/diseases6020048.

- Vande Voort JL (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. June 29, 2021.

- Safe Place: TXT 4 HELP. https://www.nationalsafeplace.org/ txt-4-help. Accessed March 30, 2022.

- Antidepressants for children and teens

Associated Procedures

- Acupuncture

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

- Psychotherapy

News from Mayo Clinic

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Know the difference between adult and teen depression April 15, 2022, 04:00 p.m. CDT

Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, has been recognized as one of the top Psychiatry hospitals in the nation for 2023-2024 by U.S. News & World Report.

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Let’s celebrate our doctors!

Join us in celebrating and honoring Mayo Clinic physicians on March 30th for National Doctor’s Day.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Depression in Teens

Barbara Poncelet, CRNP, is a certified pediatric nurse practitioner specializing in teen health.

Steven Gans, MD is board-certified in psychiatry and is an active supervisor, teacher, and mentor at Massachusetts General Hospital.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/steven-gans-1000-51582b7f23b6462f8713961deb74959f.jpg)

Verywell / Jo Zixuan Zhou

As much as 8% of teens experience depression each year, according to one survey. By the time young adults reach age 21, one study found that nearly 15% have had at least one episode of a mood disorder. Depression can cause problems such as difficulties in school, difficulties with relationships, and decreased enjoyment of life. At its worst, depression can lead to suicide, one of the leading causes of death for teens in the United States.

Depression is an illness with many causes and many forms. It is a disorder of a person’s moods or emotions—not an attitude that someone can “control” or “snap out of.” But it is treatable with psychotherapy and/or medication, which is why it's especially important for parents and caregivers to educate themselves about the disorder.

Adults sometimes don’t recognize symptoms of depression in teens because the disorder can look quite different from that in adults. A teenager with depression might have some or all of these signs of the illness:

- Sad or depressed mood

- Feelings of worthlessness or hopelessness

- Loss of interest in things they used to enjoy

- Withdrawal from friends and family

- Inability to sleep or sleeping too much

- Loss of appetite or increased appetite

- Aches and pains that don’t go away, even with treatment

- Irritability

- Feeling tired despite getting enough sleep

- Inability to concentrate

- Thoughts of suicide, talk of suicide, or suicide attempts

Types of Teen Depression

The National Institute of Mental Health states that there are two common forms of depression found in teens: major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder (now known as persistent depressive disorder).

- Major depressive disorder , also called major depression, is characterized by a combination of symptoms that interfere with a person's ability to work, sleep, study, eat, and enjoy once pleasurable activities. Major depression is disabling and prevents a person from functioning normally. An episode of major depression may occur only once in a person's lifetime, but more often, it recurs throughout a person's life.

- Dysthymic disorder , also called dysthymia, is characterized by long-term (two years or longer) but less severe symptoms that may not disable a person but can prevent one from functioning normally or feeling well. People with dysthymia may also experience one or more episodes of major depression during their lifetimes.

There are thought to be many causes of depression . There are most likely many factors behind who develops depression and who doesn’t, and these factors are no different for teens.

- Traumatic life event, such as the loss of a loved one or pet, divorce, or remarriage. Any event that causes distress or trauma, or even just a major change in lifestyle, can trigger depression in a vulnerable individual.

- Social situation/family circumstances. Unfortunately, there are teens who live in difficult circumstances. Domestic violence, substance abuse, poverty or other family issues can cause stress and contribute to depression in a teen.

- Genetics/biology. It has been found that depression runs in families and that there is a genetic basis for depression. Keep in mind, though, that teens who have depression in their family will not necessarily get the illness, and teens without a history of depression in their family can still get the disorder.

- Medical conditions. Occasionally, symptoms of depression can be a sign of another medical illness, such as hypothyroidism, or other disorders.

- Medications/illegal drugs. Some legal, prescription medications can have depression as a side effect. Certain illegal drugs (street drugs) can also cause depression.

Depression in teens is most often diagnosed by a primary care physician.

Researchers suggest that teen depression is often underdiagnosed and undertreated.

If teen depression is suspected, a doctor will often start with a physical exam that may include blood tests. Your teen's pediatrician will want to rule out any other medical illnesses that may be causing or contributing to your teen's symptoms.

Your child will also be given a psychological evaluation. This often involves a depression questionnaire as well as a discussion about the severity and duration of their symptoms.

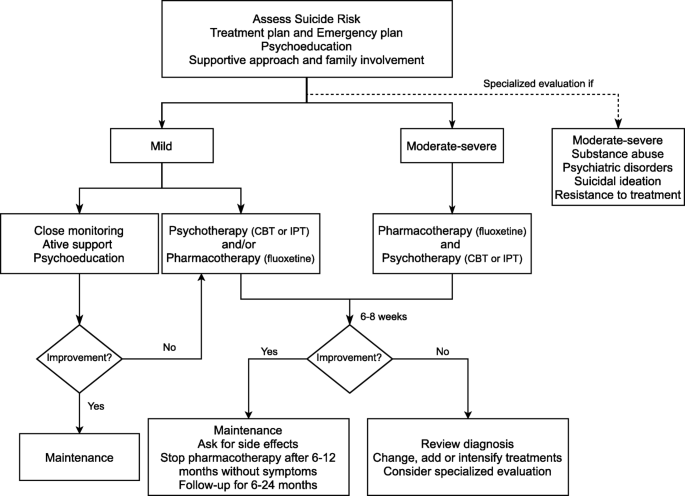

The Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC) recommend the following in the management of teen depression:

- Educating teens and families about treatment options that are available

- Developing a treatment plan that includes specific treatment goals that address functioning at home and school

- Collaborating with other mental health resources in the community

- Creating a safety plan with steps that should be taken if the teen's symptoms become worse or if they experience suicidal thinking

- Considering active support and monitoring before beginning other treatments

- Consulting a mental health specialist if symptoms are moderate or severe

- Incorporating evidence-based treatments such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, interpersonal therapy, and antidepressants

- Continuing to monitor symptoms and functioning during antidepressant treatment; doctors and family member should watch for signs that symptoms are worsening and for suicidal thinking or behaviors

Talk to your teen about your concerns. There may be a specific cause for why they are acting a certain way. Opening up the lines of communication lets your teenager know you care and that you are available to talk about the situation and provide support.

Other things that may help your teen manage symptoms of depression include:

- Talking about concerns with family and friends

- Having a healthy support system

- Using good stress management techniques

- Eating a healthy diet

- Getting regular exercise

- Finding new things to look forward to

- Joining a support group, either offline or online

Also, talk to your pediatrician or family physician if you have concerns about your teen regarding depression. Your provider may be able to discuss the situation with your teen, rule out a medical reason for the behavior, recommend a psychotherapist, or prescribe medication .

Lastly, never ignore the signs or symptoms of depression. Depression is treatable and there is help available for both you and your teen. If left untreated, depression can lead to thoughts of suicide or even the act itself.

If your teen talks about suicide or attempts suicide, get help immediately. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cites suicide as the third leading cause of death for people between the ages of 10 and 24.

If a teen is in immediate danger of suicide, call 911. If you or a loved one is having thoughts of suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 to get support from a trained counselor in your area.

For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database .

Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Georgiades K, Green JG, et al. Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement . Arch Gen Psychiatry . 2012; 69(4): 372-80. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.160

Copeland W, Shanahan L, Costello EJ, Angold A. Cumulative prevalence of psychiatric disorders by young adulthood: A prospective cohort analysis from the Great Smoky Mountains Study . J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry . 2011; 50(3): 252-261. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2010.12.014

Cheung AH, Kozloff N, Sacks D. Pediatric depression: An evidence-based update on treatment interventions . D. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013; 15: 381. doi:10.1007/s11920-013-0381-4

Zuckerbrot RA, Cheung A, Jensen PS, Stein REK, Larague D, GLAD-PC Steering Group. Guidelines for adolescent depression in primary care (GLAD-PC): Part II. Treatment and ongoing management . Pediatrics . 2018; 141(3). pii: e20174082. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-4082

By Barbara Poncelet Barbara Poncelet, CRNP, is a certified pediatric nurse practitioner specializing in teen health.

Parent’s Guide to Teen Depression

Are you feeling suicidal, coping with depression.

- Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD): How to Cope with Severe PMS

- I Feel Depressed: 9 Ways to Deal with Depression

- Depression Types and Causes: Clinical, Major, and Others

- Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT): How it Works and What to Expect

Depression Symptoms and Warning Signs

- Online Therapy: Is it Right for You?

- Mental Health

- Health & Wellness

- Children & Family

- Relationships

Are you or someone you know in crisis?

- Bipolar Disorder

- Eating Disorders

- Grief & Loss

- Personality Disorders

- PTSD & Trauma

- Schizophrenia

- Therapy & Medication

- Exercise & Fitness

- Healthy Eating

- Well-being & Happiness

- Weight Loss

- Work & Career

- Illness & Disability

- Heart Health

- Childhood Issues

- Learning Disabilities

- Family Caregiving

- Teen Issues

- Communication

- Emotional Intelligence

- Love & Friendship

- Domestic Abuse

- Healthy Aging

- Aging Issues

- Alzheimer’s Disease & Dementia

- Senior Housing

- End of Life

- Meet Our Team

What is teen depression?

Signs and symptoms of teen depression, coping with suicidal thoughts, why am i depressed, overcoming teen depression tip 1: talk to an adult you trust, tip 2: try not to isolate yourself—it makes depression worse, tip 3: adopt healthy habits, tip 4: manage stress and anxiety, how to help a depressed teen friend, dealing with teen depression.

No matter how despondent life seems right now, there are many things you can do to start feeling better today. Use these tools to help yourself or a friend.

The teenage years can be really tough and it’s perfectly normal to feel sad or irritable every now and then. But if these feelings don’t go away or become so intense that you feel overwhelmingly hopeless and helpless, you may be suffering from depression.

Teen depression is much more than feeling temporarily sad or down in the dumps. It’s a serious and debilitating mood disorder that can change the way you think, feel, and function in your daily life, causing problems at home, school, and in your social life. When you’re depressed, you may feel hopeless and isolated and it can seem like no one understands. But depression is far more common in teens than you may think. The increased academic pressures, social challenges, and hormonal changes of the teenage years mean that about one in five of us suffer with depression in our teens. You’re not alone and your depression is not a sign of weakness or a character flaw.

Even though it can feel like the black cloud of depression will never lift, there are plenty of things you can do to help yourself deal with symptoms, regain your balance and feel more positive, energetic, and hopeful again.

If you’re a parent or guardian worried about your child…

While it isn’t always easy to differentiate from normal teenage growing pains, teen depression is a serious health problem that goes beyond moodiness. As a parent, your love, guidance, and support can go a long way toward helping your teen overcome depression and get their life back on track. Read Parent’s Guide to Teen Depression .

It can be hard to put into words exactly how depression feels—and we don’t all experience it the same way. For some teens, depression is characterized by feelings of bleakness and despair. For others, it’s a persistent anger or agitation, or simply an overwhelming sense of “emptiness.” However depression affects you, though, there are some common symptoms that you may experience:

- You constantly feel irritable, sad, or angry.

- Nothing seems fun anymore—even the activities you used to love—and you just don’t see the point of forcing yourself to do them.

- You feel bad about yourself—worthless, guilty, or just “wrong” in some way.

- You sleep too much or not enough.

- You’ve turned to alcohol or drugs to try to change the way you feel .

- You have frequent, unexplained headaches or other physical pains or problems.

- Anything and everything makes you cry.

- You’re extremely sensitive to criticism.

- You’ve gained or lost weight without consciously trying to.

- You’re having trouble concentrating, thinking straight, or remembering things. Your grades may be plummeting because of it.

- You feel helpless and hopeless.

- You’re thinking about death or suicide. (If so, talk to someone right away!)

If your negative feelings caused by depression become so overwhelming that you can’t see any solution besides harming yourself or others, you need to get help right away . Asking for help when you’re in the midst of such strong emotions can be really difficult, but it’s vital you reach out to someone you trust—a friend, family member, or teacher, for example. If you don’t feel that you have anyone to talk to, or think that talking to a stranger might be easier, call a suicide helpline . You’ll be able to speak in confidence to someone who understands what you’re going through and can help you deal with your feelings.

Whatever your situation, it takes real courage to face death and step back from the brink. You can use that courage to help you keep going and overcome depression.

There is ALWAYS another solution, even if you can’t see it right now. Many people who have survived a suicide attempt say that they did it because they mistakenly felt there was no other solution to a problem they were experiencing. At the time, they couldn’t see another way out, but in truth, they didn’t really want to die. Remember that no matter how badly you feel, these emotions will pass.

Having thoughts of hurting yourself or others does not make you a bad person. Depression can make you think and feel things that are out of character. No one should judge you or condemn you for these feelings if you are brave enough to talk about them.

If your feelings are uncontrollable, tell yourself to wait 24 hours before you take any action. This can give you time to really think things through and give yourself some distance from the strong emotions that are plaguing you. During this 24-hour period, try to talk to someone—anyone—as long as they are not another suicidal or depressed person. Call a hotline or talk to a friend. What do you have to lose?

If you’re afraid you can’t control yourself, make sure you are never alone. Even if you can’t verbalize your feelings, just stay in public places, hang out with friends or family members, or go to a movie—anything to keep from being by yourself and in danger.

If you're thinking about suicide…

Please read Are You Feeling Suicidal? or call a helpline:

- In the U.S.: 988

- UK: 116 123

- Australia: 13 11 14

- To find a helpline in other countries, visit IASP or Suicide.org .

Remember, suicide is a “permanent solution to a temporary problem.” Please take that first step and reach out now.

Despite what you may have been told, depression is not simply caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain that can be cured with medication. Rather, depression is caused by a combination of biological, psychological, and social factors . Since the teenage years can be a time of great turmoil and uncertainty, you’re likely facing a host of pressures that could contribute to your depression symptoms. These can range from hormonal changes to problems at home or school or questions about who you are and where you fit in.

As a teen, you’re more likely to suffer from depression if you have a family history of depression or have experienced early childhood trauma, such as the loss of a parent or physical or emotional abuse .

Risk factors for teen depression

Risk factors that can trigger or exacerbate depression in teens include:

- Serious illness, chronic pain, or physical disability .

- Having other mental health conditions, such as anxiety, an eating disorder , learning disorder , or ADHD.

- Alcohol or drug abuse.

- Academic or family problems.

- Trauma from violence or abuse.

- Recent stressful life experiences, such as parental divorce or the death of a loved one.

- Coping with your sexual identity in an unsupportive environment.

- Loneliness and lack of social support.

- Spending too much time on social media .

If you’re being bullied…

The stress of bullying—whether it’s online, at school, or elsewhere—is very difficult to live with. It can make you feel helpless, hopeless, and ashamed: the perfect recipe for depression.

If you’re being bullied, know that it’s not your fault. No matter what a bully says or does, you should not be ashamed of who you are or what you feel. Bullying is abuse and you don’t have to put up with it . You deserve to feel safe, but you’ll most likely need help. Find support from friends who don’t bully and turn to an adult you trust—whether it’s a parent, teacher, counselor, pastor, coach, or the parent of a friend.

Whatever the causes of your depression, the following tips can help you overcome your symptoms, change how you feel, and regain your sense of hope and enthusiasm.

Depression is not your fault, and you didn’t do anything to cause it. However, you do have some control over feeling better. The first step is to ask for help.

Speak to a Licensed Therapist

BetterHelp is an online therapy service that matches you to licensed, accredited therapists who can help with depression, anxiety, relationships, and more. Take the assessment and get matched with a therapist in as little as 48 hours.

Talking to someone about depression

It may seem like there’s no way your parents will be able to help, especially if they are always nagging you or getting angry about your behavior. The truth is, parents hate to see their kids hurting. They may feel frustrated because they don’t understand what is going on with you or know how to help.

- If your parents are abusive in any way, or if they have problems of their own that makes it difficult for them to take care of you, find another adult you trust (such as a relative, teacher, counselor, or coach). This person can either help you approach your parents, or direct you toward the support you need.

- If you truly don’t have anyone you can talk to, there are many hotlines, services, and support groups that can help.

- No matter what, talk to someone, especially if you are having any thoughts of harming yourself or others. Asking for help is the bravest thing you can do, and the first step on your way to feeling better.

The importance of accepting and sharing your feelings

It can be hard to open up about how you’re feeling—especially when you’re feeling depressed, ashamed, or worthless. It’s important to remember that many people struggle with feelings like these at one time or another—it doesn’t mean that you’re weak, fundamentally flawed, or no good. Accepting your feelings and opening up about them with someone you trust will help you feel less alone.

Even though it may not feel like it at the moment, people do love and care about you. If you can muster the courage to talk about your depression, it can—and will—be resolved. Some people think that talking about sad feelings will make them worse, but the opposite is almost always true. It is very helpful to share your worries with someone who will listen and care about what you say. They don’t need to be able to “fix” you; they just need to be good listeners.

Depression causes many of us to withdraw into our shells. You may not feel like seeing anybody or doing anything and some days just getting out of bed in the morning can be difficult. But isolating yourself only makes depression worse. So even if it’s the last thing you want to do, try to force yourself to stay social. As you get out into the world and connect with others, you’ll likely find yourself starting to feel better.

Spend time face-to-face with friends who make you feel good —especially those who are active, upbeat, and understanding. Avoid hanging out with those who abuse drugs or alcohol, get you into trouble, or make you feel judged or insecure.

Get involved in activities you enjoy (or used to). Getting involved in extracurricular activities seem like a daunting prospect when you’re depressed, but you’ll feel better if you do. Choose something you’ve enjoyed in the past, whether it be a sport, an art, dance or music class, or an after-school club. You might not feel motivated at first, but as you start to participate again, your mood and enthusiasm will begin to lift.

Volunteer. Doing things for others is a powerful antidepressant and happiness booster. Volunteering for a cause you believe in can help you feel reconnected to others and the world, and give you the satisfaction of knowing you’re making a difference.

Cut back on your social media use. While it may seem that losing yourself online will temporarily ease depression symptoms, it can actually make you feel even worse. Comparing yourself unfavorably with your peers on social media , for example, only promotes feelings of depression and isolation. Remember: people always exaggerate the positive aspects of their lives online, brushing over the doubts and disappointments that we all experience. And even if you’re just interacting with friends online, it’s no replacement for in-person contact. Eye-to-eye contact, a hug, or even a simple touch on the arm from a friend can make all the difference to how you’re feeling.

Making healthy lifestyle choices can do wonders for your mood. Things like eating right, getting regular exercise, and getting enough sleep have been shown to make a huge difference when it comes to depression.

Get moving! Ever heard of a “runner’s high”? You actually get a rush of endorphins from exercising, which makes you feel instantly happier. Physical activity can be as effective as medications or therapy for depression, so get involved in sports, ride your bike, or take a dance class. Any activity helps! If you’re not feeling up to much, start with a short daily walk, and build from there.

Be smart about what you eat. An unhealthy diet can make you feel sluggish and tired, which worsens depression symptoms. Junk food , refined carbs, and sugary snacks are the worst culprits! They may give you a quick boost, but they’ll leave you feeling worse in the long run. Make sure you’re feeding your mind with plenty of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. Talk to your parents, doctor, or school nurse about how to ensure your diet is adequately nutritious.

Avoid alcohol and drugs. You may be tempted to drink or use drugs in an effort to escape from your feelings and get a “mood boost,” even if just for a short time. However, as well as causing depression in the first place, substance use will only make depression worse in the long run. Alcohol and drug use can also increase suicidal feelings. If you’re addicted to alcohol or drugs , seek help. You will need special treatment for your substance problem on top of whatever treatment you’re receiving for your depression.

Aim for eight hours of sleep each night. Feeling depressed as a teenager typically disrupts your sleep. Whether you’re sleeping too little or too much, your mood will suffer. But you can get on a better sleep schedule by adopting healthy sleep habits.

For many teens, stress and anxiety can go hand-in-hand with depression. Unrelenting stress, doubts, or fears can sap your emotional energy, affect your physical health, send your anxiety levels soaring, and trigger or exacerbate depression.

If you’re suffering from an anxiety disorder , it can manifest itself in a variety of ways. Perhaps you endure intense anxiety attacks that strike without warning, get panicky at the thought of speaking in class, experience uncontrollable, intrusive thoughts, or live in a constant state of worry. Since anxiety makes depression worse (and vice versa), it’s important to get help for both conditions.

Tips for managing stress

Managing the stress in your life starts with identifying the sources of that stress:

- If exams or classes seem overwhelming, for example, talk to a teacher or school counselor, or find ways of improving how you manage your time.

- If you have a health concern you feel you can’t talk to your parents about—such as a pregnancy scare or drug problem —seek medical attention at a clinic or see a doctor. A health professional can guide you towards appropriate treatment (and help you approach your parents if that’s necessary).

- If you’re struggling to fit in or dealing with relationship, friendship, or family difficulties, talk your problems over with your school counselor or a professional therapist. Exercise, meditation , muscle relaxation, and breathing exercises are other good ways to cope with stress.

- If your own negative thoughts and chronic worrying are contributing to your everyday stress levels, you can take steps to break the habit and regain control of your worrying mind.

If you’re a teenager with a friend who seems down or troubled, you may suspect depression. But how do you know it’s not just a passing phase or a bad mood? Look for common warning signs of teen depression:

- Your friend doesn’t want to do the things you guys used to love to do.

- Your friend starts using alcohol or drugs or hanging with a bad crowd.

- Your friend stops going to classes and after-school activities.

- Your friend talks about being bad, ugly, stupid, or worthless.

- Your friend starts talking about death or suicide.

Teens typically rely on their friends more than their parents or other adults, so you may find yourself in the position of being the first—or only—person that your depressed friend confides in. While this might seem like a huge responsibility, there are many things you can do to help :

Get your friend to talk to you. Starting a conversation about depression can be daunting, but you can say something simple: “You seem like you are really down, and not yourself. I really want to help you. Is there anything I can do?”

You don’t need to have the answers. Your friend just needs someone to listen and be supportive. By listening and responding in a non-judgmental and reassuring manner, you are helping in a major way.

Encourage your friend to get help. Urge your depressed friend to talk to a parent, teacher, or counselor. It might be scary for your friend to admit to an authority figure that they have a problem. Having you there might help, so offer to go along for support.

Stick with your friend through the hard times. Depression can make people do and say things that are hurtful or strange. But your friend is going through a very difficult time, so try not to take it personally. Once your friend gets help, they will go back to being the person you know and love. In the meantime, make sure you have other friends or family taking care of you. Your feelings are important and need to be respected, too.

Speak up if your friend is suicidal. If your friend is joking or talking about suicide, giving possessions away, or saying goodbye, tell a trusted adult immediately. Your only responsibility at this point is to get your friend help , and get it fast. Even if you promised not to tell, your friend needs your help. It’s better to have a friend who is temporarily angry at you than one who is no longer alive.

Depression support, suicide prevention help

Depression support.

Find DBSA Chapters/Support Groups or call the NAMI Helpline for support and referrals at 1-800-950-6264

Find Depression support groups in-person and online or call the Mind Infoline at 0300 123 3393

Call the SANE Help Centre at 1800 18 7263

Call Mood Disorders Society of Canada at 519-824-5565

Call the Vandrevala Foundation Helpline (India) at 1860 2662 345 or 1800 2333 330

Suicide prevention help

Call 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988

Call Samaritans UK at 116 123

Call Lifeline Australia at 13 11 14

Visit IASP or Suicide.org to find a helpline near you

More Information

- Depression: What You Need to Know - Depression in teenagers, including symptoms, remedies, and how to talk to your parents. (TeensHealth)

- Depression in Teens - Recognizing and treating adolescent depression. (Mental Health America)

- How to Talk to Your Parents About Getting Help - Speaking up for yourself is the first step to getting better. (Child Mind Institute)

- Petito, A., Pop, T. L., Namazova-Baranova, L., Mestrovic, J., Nigri, L., Vural, M., Sacco, M., Giardino, I., Ferrara, P., & Pettoello-Mantovani, M. (2020). The Burden of Depression in Adolescents and the Importance of Early Recognition. The Journal of Pediatrics, 218, 265-267.e1. Link

- Hallfors, D. D., Waller, M. W., Ford, C. A., Halpern, C. T., Brodish, P. H., & Iritani, B. (2004). Adolescent depression and suicide risk: Association with sex and drug behavior. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 27(3), 224–231. Link

- Merikangas, K. R., He, J., Burstein, M., Swanson, S. A., Avenevoli, S., Cui, L., Benjet, C., Georgiades, K., & Swendsen, J. (2010). Lifetime Prevalence of Mental Disorders in U.S. Adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989. Link

- Bhatia, S. K., & Bhatia, S. C. (2007). Childhood and Adolescent Depression. American Family Physician, 75(1), 73–80. Link

- NIMH » Major Depression. (n.d.). Retrieved July 26, 2021, from Link

- Depressive Disorders. (2013). In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders . American Psychiatric Association. Link

More in Depression

Recognizing the signs and symptoms, and helping your child

How to deal with suicidal thoughts and feelings

Tips for overcoming depression one step at a time

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD)

Coping with severe PMS

I Feel Depressed

9 Ways to Deal with Depression

Depression Types and Causes

What type of depression do you have and what’s causing it?

Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT)

How it works and how to decide if it’s the right treatment for you

Recognizing depression and getting the help you need

Professional therapy, done online

BetterHelp makes starting therapy easy. Take the assessment and get matched with a professional, licensed therapist.

Help us help others

Millions of readers rely on HelpGuide.org for free, evidence-based resources to understand and navigate mental health challenges. Please donate today to help us save, support, and change lives.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

‘It’s Life or Death’: The Mental Health Crisis Among U.S. Teens

Depression, self-harm and suicide are rising among American adolescents. For one 13-year-old, the despair was almost too much to take.

By Matt Richtel

Photographs by Annie Flanagan

Matt Richtel spent more than a year interviewing adolescents and their families for this series on the mental health crisis.

One evening last April, an anxious and free-spirited 13-year-old girl in suburban Minneapolis sprang furious from a chair in the living room and ran from the house — out a sliding door, across the patio, through the backyard and into the woods.

Moments earlier, the girl’s mother, Linda, had stolen a look at her daughter’s smartphone. The teenager, incensed by the intrusion, had grabbed the phone and fled. (The adolescent is being identified by an initial, M, and the parents by first name only, to protect the family’s privacy.)

Linda was alarmed by photos she had seen on the phone. Some showed blood on M’s ankles from intentional self-harm. Others were close-ups of M’s romantic obsession, the anime character Genocide Jack — a brunette girl with a long red tongue who, in a video series, kills high school classmates with scissors.

In the preceding two years, Linda had watched M spiral downward: severe depression, self-harm, a suicide attempt. Now, she followed M into the woods, frantic. “Please tell me where u r,” she texted. “I’m not mad.”

American adolescence is undergoing a drastic change. Three decades ago, the gravest public health threats to teenagers in the United States came from binge drinking, drunken driving, teenage pregnancy and smoking. These have since fallen sharply, replaced by a new public health concern: soaring rates of mental health disorders.

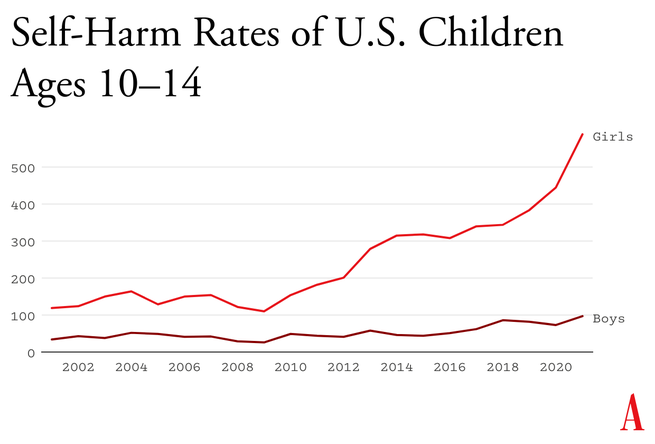

In 2019, 13 percent of adolescents reported having a major depressive episode , a 60 percent increase from 2007 . Emergency room visits by children and adolescents in that period also rose sharply for anxiety, mood disorders and self-harm. And for people ages 10 to 24, suicide rates, stable from 2000 to 2007, leaped nearly 60 percent by 2018, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Emergency room visits for self-harm by children and adolescents rose sharply over the last decade, particularly among young women.

600 E.R. visits

per 100,000

Emergency room visits

for self-inflicted injuries

Ages 10–19

Emergency room visits for self-harm by children and adolescents rose sharply over the last decade, particularly for young women.

room visits

for self-harm

The decline in mental health among teenagers was intensified by the Covid pandemic but predated it, spanning racial and ethnic groups, urban and rural areas and the socioeconomic divide. In December, in a rare public advisory, the U.S. surgeon general warned of a “devastating” mental health crisis among adolescents. Numerous hospital and doctor groups have called it a national emergency , citing rising levels of mental illness, a severe shortage of therapists and treatment options, and insufficient research to explain the trend.

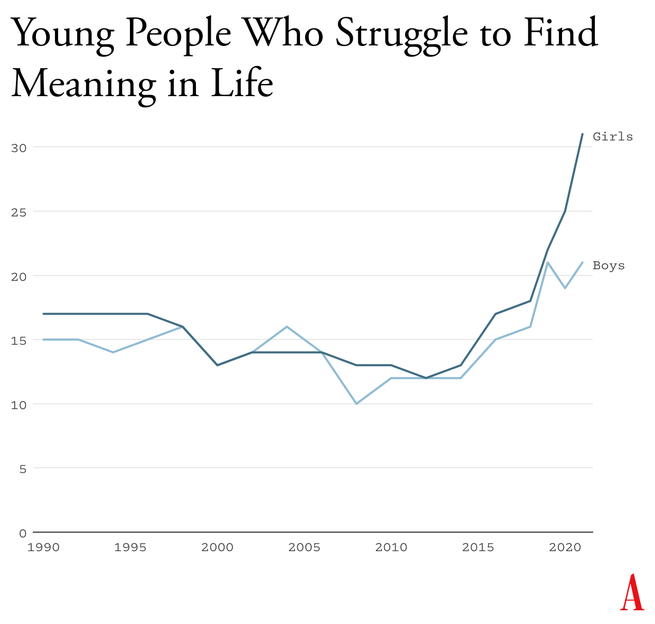

“Young people are more educated; less likely to get pregnant, use drugs; less likely to die of accident or injury,” said Candice Odgers, a psychologist at the University of California, Irvine. “By many markers, kids are doing fantastic and thriving. But there are these really important trends in anxiety, depression and suicide that stop us in our tracks.”

“We need to figure it out,” she said. “Because it’s life or death for these kids.”

Read about how Matt Richtel reported this series .

The crisis is often attributed to the rise of social media , but solid data on the issue is limited, the findings are nuanced and often contradictory and some adolescents appear to be more vulnerable than others to the effects of screen time. Federal research shows that teenagers as a group are also getting less sleep and exercise and spending less in-person time with friends — all crucial for healthy development — at a period in life when it is typical to test boundaries and explore one’s identity. The combined result for some adolescents is a kind of cognitive implosion: anxiety, depression, compulsive behaviors, self-harm and even suicide.

This surge has raised vexing questions. Are these issues inherent to adolescence that merely went unrecognized before — or are they being overdiagnosed now? Historical comparisons are difficult, as some data around certain issues, like teen anxiety and depression, began to be collected relatively recently. But the rising rates of emergency-room visits for suicide and self-harm leave little doubt that the physical nature of the threat has changed significantly.

As M descended, Linda and her husband realized they were part of an unenviable club: bewildered parents of an adolescent in profound distress. Linda talked with parents of other struggling teenagers; not long before the night M fled into the forest, Linda was jolted by the news that a local girl had died by suicide.

“You have no control over what they’re thinking,” Linda said. “I just want to tell people what can happen.”

‘A typical outpatient’

M is one of dozens of teenagers who spoke to The New York Times for a yearlong project exploring the changing nature of adolescence in the United States. The Times was given permission by M and the family to speak with M’s school counselor; M’s medical records were shared with The Times and, with the family’s permission, reviewed by outside experts not involved in M’s care.

“This is a typical outpatient,” said Emily Pluhar, a child and adolescent psychologist at Harvard University, describing M as “an internalizer.”

M, now 14, is tall, with red hair and blue eyes, and has a younger sister and older half brother. By turns shy and outspoken, M has thought extensively about pronouns and currently prefers “they.” At the beginning of seventh grade, M also asked to be called by the name of a popular Japanese anime character, whose first name starts with M. “I think we’re similar in that she’s, like, quiet and smart and plays electric bass, and I really like bass and guitars,” M said.

When M was 4, a psychologist the family consulted to assess M’s school readiness concluded that their “intellectual ability is in the very superior range,” according to the report. M enrolled in kindergarten as one of the younger class members.

At 10, M got a smartphone. Linda and her husband, Tony, both of whom had busy work schedules, worried that the device might lead to heavy screen time, but they felt it was necessary to stay in touch. At 11, M hit another adolescent milestone: puberty.

Over the last century, the age of puberty onset has dropped markedly for girls, to 12 years old today from 14 years old in 1990; the age of onset for boys has followed a similar path. Experts say this shift probably now plays a role in the adolescent mental health crisis, although it is just one of many factors that researchers are still working to understand.

When puberty hits, the brain becomes hypersensitive to social and hierarchical information, even as media flood it with opportunities to explore one’s identity and gauge self-worth. Laurence Steinberg, a psychologist at Temple University, said that ability to maturely grapple with the resulting questions — Who am I? Who are my friends? Where do I fit in? — typically lags behind.

The falling age of puberty, he said, has created a “widening gap” between incoming stimulation and what the young brain can process:

“They’re being exposed to this deluge at a much earlier age.”

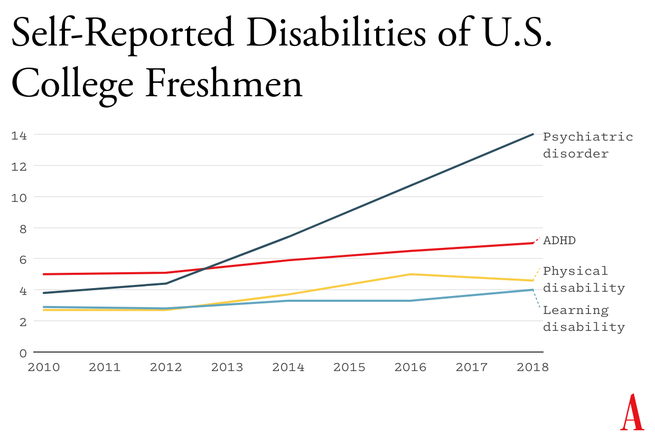

M’s first hint of trouble came in sixth grade, with challenges focusing in class. The school called a meeting with M’s parents. One teacher suggested testing M for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, but Linda and Tony were skeptical. The number of A.D.H.D. diagnoses in the United States rose 39 percent from 2003 to 2016 , according to the C.D.C., and M’s parents, both scientists in biomedical fields, were concerned that consulting an A.D.H.D. specialist would tilt the scales toward that diagnosis.

Instead, Linda tried to help M stay organized with an app that parents and students used to track assignments, test scores and grades. M felt put under a microscope.

“She would say, ‘Can you bring me your iPad so we can check Schoology?’” M recalled about Linda. “I would literally have an anxiety attack because I was so scared.”

By the fall of 2019 — seventh grade — M was struggling socially, too. A close friend got popular, while M often came home from school and got into bed. “I felt like a plus one,” M said. “I just wanted to be unconscious.” Other times, M said, “I just sat in my room and cried.”

The behavior seemed alien to Tony, who had lived a different childhood. As an adolescent in Vermont in the 1980s, he fished and played outdoors. By 15, he had his first serious girlfriend; in 1990, the summer before their senior year, he got her pregnant. Their son was born that December, and Tony and the mother shared custody.

Times have changed. Federal research shows that 38 percent of high-school-age teenagers report having had sex at least once, compared with roughly 50 percent in 1990. The teen birthrate has plummeted.

So has cigarette and alcohol use . In 2019, 4 percent of high school seniors reported having a cigarette in the last 30 days, down from 26.5 percent in 1997 . Alcohol use by high schoolers hit 30-year lows at the same time. Use of OxyContin and other illicit drugs among high schoolers is down sharply over the last 20 years. Vaping of both nicotine and marijuana has risen in recent years, although both dropped sharply during the pandemic .

Rates of smoking, drugs, alcohol and sex declined among high school students over the last decade, continuing trends that started over two decades ago.

One notable exception was a rise in excessive smartphone and computer use over the last decade.

Use a smartphone ,

tablet, computer or

game console at least

3 hours a day, not

including school work

Recently drank

Watch television

3 hours a day

Last sex was

unprotected

Get at least

8 hours of sleep

Feelings of sadness and hopelessness rose over the same decade, and suicidal thoughts increased.

Persistently felt

sad or hopeless

Made a suicide plan

Attempted suicide

Injured in a suicide

attempt and needed

medical treatment

Feelings of sadness and hopelessness rose, and suicidal thoughts increased.

Experts cite multiple factors: public awareness campaigns, antismoking laws, parental oversight and a changing social lifestyle that is no longer strictly in-person.

Dr. Nora Volkow, director for the National Institute on Drug Abuse, described drug and alcohol use as “very much of a group dynamic.” She added: “To the extent that kids are not in the same place, one would expect a decrease in the behavior.”

A virtual crush

In the spring of 2020, M retreated further. Bewildered by online classes, M lied about participating, felt guilty and watched YouTube instead, devouring an anime series called “Danganronpa.” It is set in a high school where students learn from the evil headmaster, a bear, that the only way to graduate is to kill a peer.

M became enamored of one of the characters, Genocide Jack (sometimes known as Genocide Jill), who is described on one fan site as a witty “murderous fiend” who “kills handsome men” using scissors.

One night after dinner, M was upstairs and used scissors to cut both ankles. “I was mad at myself for not doing homework,” M said. “I was kind of thinking, ‘Oh, the pain feels good,’ like it was better than being stressed.” M couldn’t recall where the idea came from: “I wanted to hurt myself with anything.”

M’s parents noticed superficial scratches on M’s thighs that resembled cuts but did not raise the subject. Linda worried about the screen time but “it was pandemic,” she said.

When school ended for summer break, M’s mood improved. Over the summer, M discovered the mobile version of the “Danganronpa” video game and how to override the parental screen limits. M played all day.

“I was in front of my screen staring at Jack,” M said. “Then I was playing ‘Trigger Happy Havoc,’ and I was, like, more in love.”

“I was kind of just lonely,” M said. M fantasized about the future with Jack: “I’d want her to almost kill me but not, and then we could spend the rest of our lives together.”

An obsession with a virtual character is not uncommon, experts said. “This is a kid who is a bit lonely, a bit caught up in these narratives,” said Nick Allen, a psychologist at the University of Oregon. “There’s nothing new in coming up with stuff that freaks out their parents.”

Nonetheless, he added, “extremely powerful” online experiences like these can encourage users to think, “That is going to be my identity, my sense of the future, my sense of where I belong socially,” at a time when one’s identity is a work in progress.

Dr. Pluhar of Harvard noted that “the challenge and the progress” of modern adolescence “is there are so many types of identity” — more choices and possibilities, which in turn could be overwhelming. Among the factors shaping mental health, Dr. Pluhar said, is the mind’s churning and obsessing: “Rumination is a big piece of it.”

M had a name for the main source of their mental health challenges: “Loneliness.”

Health experts note that, for all its weight, the adolescent crisis at least is unfolding in a more accepting environment. Mental health issues have shed much of the stigma they carried three decades ago, and parents and adolescents alike are more at ease when discussing the subject among themselves and seeking help.

Indeed, Linda had begun having conversations with other parents who wondered whether the challenges their adolescents were facing represented typical moody teen behavior or something pathological. A colleague told Linda about her daughter’s eating disorder. A mother named Sarah confided that her middle-school-age daughter was in therapy for anxiety and depression. “I told her, ‘I understand where you’re at way better than you think,’” Sarah recalled.

In a nearby suburb, the parents of Elaniv Burnett were struggling to understand their daughter’s desperation. As a young child, Elaniv had been joyful, an eager student and graceful gymnast, her father, Dr. Tatnai Burnett, a gynecological surgeon at the Mayo Clinic, recalled: “The kind of kid where you go, ‘Huh, we should have more kids.’”

But in 2014, when Elaniv was 9, her parents’ marriage began to fracture, and Elaniv injured her ankle; she developed chronic pain, which sidelined her from gymnastics, and she went through a dark period. Then, in 2016, Dr. Burnett, who is Black, was held at gunpoint at home by the police, in full view of the family, after officers responded to a call of a possible intruder.

Recent research has found that wealth, education and opportunity do not shield Black families from mental health issues to the same degree they do for white families. From 1991 to 2017, suicide attempts by Black adolescents rose 73 percent , compared with an 18 percent rise among white adolescents . (The overall suicide rate remains higher among white adolescents.) The suicide rate leaped particularly for Black girls, up 6.6 percent per year on average from 2003 to 2017, new research shows .

In the fall of 2019, Elaniv was diagnosed with major depressive disorder. In a poem in her journal, she wrote: “Thoughts like racecars zoom constant in my head/ Self-hate and worthlessness/ Perpetual, they speed ahead.”

Elaniv began therapy, took medications and enrolled in an outdoor inpatient program in Utah. “We worked on ourselves, worked on our parenting, we changed so many things to try to help meet Elaniv where she was,” Dr. Burnett said. “We controlled electronics, monitored friendships.”

Elaniv’s mother, Tania Gainza, a clinical social worker, saw a generational trend. She had counseled an adolescent for years who was terrified of not meeting expectations. She heard about a local boy who killed himself seemingly without warning.

“There’s something different about this era or generation that makes them much more susceptible or vulnerable,” Ms. Gainza said. “There’s not that community, I guess.”

A rise in loneliness is a key factor, experts said. Recent studies have shown that teenagers in the United States and worldwide increasingly report feeling lonely , even in a period when their internet use has exploded .

“They’re hanging out with friends, but no friends are there,” said Bonnie Nagel, a psychologist at the Oregon Health & Science University. “It’s not the same social connectedness we need and not the kind that prevents one from feeling lonely.”

Often, she said, online social connections amount to seeing “pictures of people hanging out, flaunting it, as if to say, ‘Hey, I’m very socially connected,’ and ‘Hey, look at you by yourself.’”

The pandemic factor

One day in the autumn of 2020, with the pandemic in full swing and eighth grade having gone fully remote, Linda found M sobbing in bed. M confessed to wanting to die.

Linda found an online therapist. After several sessions, “the therapist broke confidentiality,” Linda said. “She said, ‘You need to know about the knife.’”

In M’s night stand, Tony found a pocketknife and a box knife with a cat’s paw image on the handle that M had surreptitiously bought on Amazon and was using to self-harm. One night, M went further, tightening a red hair tie around their neck. “I was trying to see how far I could take it,” M said.

The following February, M entered full-day group therapy. A psychiatrist at the clinic notified the family that M had admitted to being unable to stop cutting, medical records show. Linda “de-knived the house,” she said, and hid all the pills. Then M engaged in a different kind of self-harm: hitting their head with an eight-pound workout barbell.

Linda recalled feeling stunned: “Oh, now I have to get rid of the blunt objects, too.”

M was discharged with a diagnosis of depression and a prescription for antidepressants. From 2015 to 2019, prescriptions for antidepressants rose 38 percent for teenagers compared with 15 percent for adults, according to Express Scripts, a major mail-order pharmacy.

Subsequently, M also received a diagnosis of attention deficit disorder, not A.D.H.D., and given a prescription for methylphenidate, the generic name for medications including Ritalin and Concerta. “I’m still not sure I believe it,” Linda said.

M’s middle school has a trained mental health counselor. In March 2021, M visited him for the first time. During that visit, on a scale of 0 to 10, M ranked hopelessness and anxiety at 9, expressing terror at returning to school, a fear of falling behind and a wish to die.

But M’s mood improved; at a meeting a month later, M ranked hopelessness and sadness at 5 and anxiousness at 2. M felt therapy was crucial but wasn’t sure the medications helped; the school counselor credited M’s improvement to family support and getting back to school. He cautioned the parents, though, that the pendulum could swing back.

Into the forest

Around that time, Linda heard through the grapevine that a girl named Elaniv Burnett had died following an overdose. “I’m sorry, I can’t take it anymore,” Elaniv wrote in a note. Her mother rushed her, still conscious, to the hospital, where Elaniv expressed regret at the overdose and described her terror. She died four days later, at age 15 .

The news was still on Linda’s mind a few weeks later when M fled into the forest.

M’s family had recently returned from visiting both sets of grandparents. One set criticized M’s pronouns, the other M’s heavy screen use. Linda said she felt judged. She stole a look at M’s phone and saw the troubling photos.

“Let’s go for a walk,” she said to M and went upstairs briefly. When she returned, M had vanished, so she followed them into the woods, texting as she frantically looked for flashes of M’s white dress.

Finally M texted back: “I don’t want to talk to you.”

Linda returned home, and Tony went out. He found M along a commonly used trail. They walked, mostly in silence. “Then they were ready to come home,” he recalled.

The school year ended, and M improved, the anxiety ebbing. M took joy spending time with a friend, in person, walking home, strolling the forest.

But a few weeks later, a hurtful text from the friend plunged M into despair again, “like I was back to having no friends.”

M used an exfoliating blade to cut both ankles. “I don’t know how to stop it,” M said. “I can bet $20 that I’ll be in the hospital next year.”

When Linda saw the cuts, she confronted M, who handed over the blade. M let Linda examine the wounds.

“I think that’s good,” Linda said. “They let me look.”

How Matt Richtel spoke to adolescents and their parents for this series

In mid-April, I was speaking to the mother of a suicidal teenager whose struggles I’ve been closely following. I asked how her daughter was doing.

Not well, the mother said: “If we can’t find something drastic to help this kid, this kid will not be here long term.” She started to cry. “It’s out of our hands, it’s out of our control,” she said. “We’re trying everything.”

She added: “It’s like waiting for the end.”

Over nearly 18 months of reporting, I got to know many adolescents and their families and interviewed dozens of doctors, therapists and experts in the science of adolescence. I heard wrenching stories of pain and uncertainty. From the outset, my editors and I discussed how best to handle the identities of people in crisis.

The Times sets a high bar for granting sources anonymity; our stylebook calls it “a last resort” for situations where important information can’t be published any other way. Often, the sources might face a threat to their career or even their safety, whether from a vindictive boss or a hostile government.

In this case, the need for anonymity had a different imperative: to protect the privacy of young, vulnerable adolescents. They have harmed themselves and attempted suicide, and some have threatened to try again. In recounting their stories, we had to be mindful that our first duty was to their safety.

If The Times published the names of these adolescents, they could be easily identified years later. Would that harm their employment opportunities? Would a teen — a legal minor — later regret having exposed his or her identity during a period of pain and struggle? Would seeing the story published amplify ongoing crises?

As a result, some teenagers are identified by first initial only; some of their parents are identified by first name or initial. Over months, I got to know M, J and C, and in Kentucky, I came to know struggling adolescents I identified only by their ages, 12, 13 and 15. In some stories, we did not publish precisely where the families lived.

Everyone I interviewed gave their own consent, and parents were typically present for the interviews with their adolescents. On a few occasions, a parent offered to leave the room, or an adolescent asked for privacy and the parent agreed.

In these articles, I heard grief, confusion and a desperate search for answers. The voices of adolescents and their parents, while shielded by anonymity, deepen an understanding of this mental health crisis.

Matt Richtel is a best-selling author and Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter based in San Francisco. He joined The Times in 2000, and his work has focused on science, technology, business and narrative-driven storytelling around these issues. More about Matt Richtel

Our website uses cookies to offer you the most relevant experience and optimal performance.

By clicking ‘Accept’ you agree to the storing of cookies on your device. Cookie Policies.

- Free Essays

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Synopsis Writing

- Book Report

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Report

- Marketing Plan

- Capstone Project

- Dissertation

- Interview Essay

- Grant Proposal

- Literary Analysis

- PhD Dissertation

- Presentation and Poster

- Research Proposal

- Research Paper

- Thesis Proposal

- Thesis Statement

- Essay Questions

- Excel Homework

- Extended Essay IB

- Film Analysis

- Movie Review

- Proofreading

- Reaction Paper

- White Paper

- Questionnaire

- Annotated Bibliography

- VIP Services

- Discussion Board Post

- Depression in Adolescents Psychology Essay Example

- Free Essays Online >

- Psychology Essay Examples >

- Depression in Adolescents Psychology Essay... >

Depression by definition is simply the mood or emotional state manifested by feelings of low self-worth or guilt and a compact incapacity to relish life. It is deemed to be a common issue among many people in our society today. Every human being experiences periods when they face hardships. Stress and mood changes that follow the difficulties fit the emotional state that marks depression. Sadness, pessimism, and hopelessness become naturally incorporated. The resulting mental symptoms include disturbed sleep and slowing of the thinking process or actions. Depression may be caused by genetic factors that are hereditary. Cases of depression vary depending on the individual; however, in order to make the diagnosing of the problem easier, it has been split into many categories. The examples of these are an acute vs. chronic and mild vs. severe depression.

Main Causes of Depression Among the Teenagers

Adolescence is the period of evolution from infancy to maturity, a stage of significant growth and development, in which substantial physiological, cognitive, psychological, and behavioral deviations take place. Adolescence is a phase of delight and anxiety; of happiness and troubles; of discovery and perplexity (Garber, 2006). It seems that the age peak of depression correlates with the peak years of low self-esteem, which is the early and middle adolescence with the peak period between the age of thirteen and fourteen (Garber, 2006). There may rise a question whether low self-esteem is a precursor for depression and other mood disorders, and if a low self-esteem curtails the resilience of the adolescent, thus making him or her more susceptible to depression.

24/7 Support

Have you got any questions?

Experts have analyzed and estimated that 5% of all teenagers suffer from depression. (Abramson, 1988). Only a small part of this portion is well-diagnosed and treated. There are some factors correlated with the depression among adolescents. Some of them include the proper process of maturing and the stress involved in the process: the influence of sex hormones, conflicts at home, and the loss of close friends and family members through death. This paper investigates the causes of depression in teenagers, the treatments taken to diagnose depression and its prevention. Female adolescents display higher levels of depression-related symptoms as compared to males. There are three main forms of treatment for depression: counseling and psychotherapy; electroconvulsive therapy (ECT); and antidepressant medications. The adolescent depression signs and symptoms vary from changes in emotions and behavior (Abramson, 1988). Emotional changes include such feelings as sadness, frustration over small matters, loss of interest, and frequent suicidal thoughts. Behavioral changes include insomnia, appetite changes, alcohol and substance abuse, agitation, and slowed body movements. Other changes may include poor school performance, absence from school, and self-harm such as tattooing excessively and adopting a risky behavior.

When depression symptoms persist, it is advisable to seek medical attention. A good family doctor or pediatrician is to be consulted to assist the teenager. If the depression symptoms are untreated, they continue getting worse day by day, and this may lead to the risk of the adolescent committing suicide (Begley, 2010). The teenagers should approach someone they trust in case they do not feel comfortable sharing their situation with anyone.

The main causes of depression among the teenagers are induced by a variety of factors. These are the changes in the body balance of hormones, early childhood traumas such as physical abuse, the loss of a parent, which may cause brain changes that may trigger depression (Beck T, 2009). Depression could also result from the inherited traits from one’s bloodline. The teenagers may be linked to learning patterns that make them feel helpless. Neurotransmitters in the human brain cells also seem to play a role in depression. When the brain chemicals are out of balance, this may lead to depression (Begley, 2010). According to rational behavior counselors, it is not essentially nerve-wracking events and positions but rather a propensity toward negative understanding of these events that initiates and upholds despair (Calles J. 2007). When a contrary incident befalls, the depressed adolescent often comprehends the reason for the event as something steady, internal, and global. For example, if a young person does not receive good grades at school, he or she may attribute this disappointment to his or her being “stupid.” This cause is steady (unlikely to change), internal (his or her fault), and global (affecting everything he or she does). There is also an indication of the genomic tendency in the causes of adolescent depression as the depressed adolescents often have high rates of depression among their family members (Springer & Beevers, 2011).