What Is the Meaning of Language Death?

Rob Atkins / Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Language death is a linguistic term for the end or extinction of a language . It is also called language extinction.

Language Extinction

Distinctions are commonly drawn between an endangered language (one with few or no children learning the language) and an extinct language (one in which the last native speaker has died).

A Language Dies Every Two Weeks

Linguist David Crystal has estimated that "one language [is] dying out somewhere in the world, on average, every two weeks". ( By Hook or by Crook: A Journey in Search of English , 2008).

Language Death

- "Every 14 days a language dies. By 2100, more than half of the more than 7,000 languages spoken on Earth — many of them not yet recorded — may disappear, taking with them a wealth of knowledge about history, culture, the natural environment, and the human brain." (National Geographic Society, Enduring Voices Project)

- "I am always sorry when any language is lost, because languages are the pedigree of nations." (Samuel Johnson, quoted by James Boswell in The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides , 1785)

- "Language death occurs in unstable bilingual or multilingual speech communities as a result of language shift from a regressive minority language to a dominant majority language. (Wolfgang Dressler, "Language Death." 1988)

- "Aboriginal Australia holds some of the world's most endangered languages including Amurdag, which was believed to be extinct until a few years ago when linguists came across speaker Charlie Mangulda living in the Northern Territory." (Holly Bentley, "Mind Your Language." The Guardian , Aug. 13, 2010)

The Effects of a Dominant Language

- "A language is said to be dead when no one speaks it anymore. It may continue to have existence in recorded form, of course — traditionally in writing , more recently as part of a sound or video archive (and it does in a sense 'live on' in this way) — but unless it has fluent speakers one would not talk of it as a 'living language.'...

- "The effects of a dominant language vary markedly in different parts of the world, as do attitudes towards it. In Australia, the presence of English has, directly or indirectly, caused great linguistic devastation, with 90% of languages moribund. But English is not the language which is dominant throughout Latin America: if languages are dying there, it is not through any 'fault' of English. Moreover, the presence of a dominant language does not automatically result in a 90% extinction rate. Russian has long been dominant in the countries of the former USSR, but there the total destruction of local languages has been estimated to be only ( sic ) 50%."(David Crystal, Language Death . Cambridge University Press, 2002)

Aesthetic Loss

- "The main loss when a language dies is not cultural but aesthetic. The click sounds in certain African languages are magnificent to hear. In many Amazonian languages, when you say something you have to specify, with a suffix, where you got the information. The Ket language of Siberia is so awesomely irregular as to seem a work of art.

- "But let’s remember that this aesthetic delight is mainly savored by the outside observer, often a professional savorer like myself. Professional linguists or anthropologists are part of a distinct human minority. . . .

- "At the end of the day, language death is, ironically, a symptom of people coming together. Globalization means hitherto isolated peoples migrating and sharing space. For them to do so and still maintain distinct languages across generations happens only amidst unusually tenacious self-isolation — such as that of the Amish — or brutal segregation. (Jews did not speak Yiddish in order to revel in their diversity but because they lived in an apartheid society.)" (John McWhorter, "The Cosmopolitan Tongue: The Universality of English." World Affairs Journal , Fall 2009)

Steps to Preserve a Language

[T]he best non-linguists can do, in North-America, towards preserving languages, dialects , vocabularies and the like is, among other possible actions, (French linguist Claude Hagège, author of On the Death and Life of Languages , in "Q and A: The Death of Languages." The New York Times , Dec. 16, 2009)

- Participating in associations which, in the US and Canada, work to obtain from local and national governments a recognition of the importance of Indian languages (prosecuted and led to quasi-extinction during the XIXth century) and cultures, such as those of the Algonquian, Athabaskan, Haida, Na-Dene, Nootkan, Penutian, Salishan, Tlingit communities, to name just a few;

- Participating in funding the creation of schools and the appointment and payment of competent teachers;

- Participating in the training of linguists and ethnologists belonging to Indian tribes, in order to foster the publication of grammars and dictionaries, which should also be financially helped;

- Acting in order to introduce the knowledge of Indian cultures as one of the important topics in American and Canadian TV and radio programs.

An Endangered Language in Tabasco

- "The language of Ayapaneco has been spoken in the land now known as Mexico for centuries. It has survived the Spanish conquest , seen off wars, revolutions, famines, and floods. But now, like so many other indigenous languages, it's at risk of extinction.

- "There are just two people left who can speak it fluently — but they refuse to talk to each other. Manuel Segovia, 75, and Isidro Velazquez, 69, live 500 metres apart in the village of Ayapa in the tropical lowlands of the southern state of Tabasco. It is not clear whether there is a long-buried argument behind their mutual avoidance, but people who know them say they have never really enjoyed each other's company.

- "'They don't have a lot in common,' says Daniel Suslak, a linguistic anthropologist from Indiana University, who is involved with a project to produce a dictionary of Ayapaneco. Segovia, he says, can be 'a little prickly' and Velazquez, who is 'more stoic,' rarely likes to leave his home.

- "The dictionary is part of a race against time to revitalize the language before it is definitively too late. 'When I was a boy everybody spoke it,' Segovia told the Guardian by phone. 'It's disappeared little by little, and now I suppose it might die with me.'" (Jo Tuckman, "Language at Risk of Dying Out — Last Two Speakers Aren't Talking." The Guardian , April 13, 2011)

- "Those linguists racing to save dying languages — urging villagers to raise their children in the small and threatened language rather than the bigger national language — face criticism that they are unintentionally helping keep people impoverished by encouraging them to stay in a small-language ghetto." (Robert Lane Greene, You Are What You Speak . Delacorte, 2011)

- Get the Definition of Mother Tongue Plus a Look at Top Languages

- Definition and Examples of Native Languages

- Definition and Examples of Dialect in Linguistics

- Standard English Definitions and Controversies

- Definition and Examples of Prescriptive Grammar

- etymology (words)

- New Englishes: Adapting the Language to Meet New Needs

- Generative Grammar: Definition and Examples

- Indian English, AKA IndE

- Prescriptivism

- Indeterminacy (Language)

- Pragmatics Gives Context to Language

- What Is Transitivity in Grammar?

- Definition and Examples of Dialect Leveling

- Regionalism

- Descriptive Grammar

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Language death Why should we care?

Related Papers

IOSR Journals

Abstract: Language is essential in humans’ lives; it is what takes to differentiate between animals and humans, it is what we use to understand ourselves. Upon all its status in human life, people are still crying of language disappearance, because many died and some are endangered. There are some questions that supposed to be asked, but only few were raised. We tried to look at major areas such as: the importance of languages, the statistics of languages, what really caused the endangerment, and a way out (solution). Though, the issue is very vast, but we tried and narrowed ourselves down to the minimal level just not to confuse readers. Key words: Language, death, endangered, and revitalization

Banu Oralbayeva

Language endangerment, a global phenomenon, is accelerating and 90 percent of the world's languages are about to disappear in 21 st century, leading to the loss of human intellectual and cultural diversity. When Europe colonized the New World and the South, an enormous body of cultural and intellectual wealth of indigenous people was lost completely and it was appreciable only through the language that disappeared with it (Hale, 1998). This research deals with the problem of language loss in the world and seeks answer to critical questions: What does language extinction mean for humankind? What is to be done to save languages from loss? Some scholars suggest that linguists should find solutions whereas others disagree that it is linguists' responsibility to maintain and preserve the currently disappearing languages. Moreover, the research indicates that not only language specialists are participating in this process but also general public, particularly members of the communities whose languages are declining, are contributing their efforts in saving languages from loss.

Current Issues in Linguistic Theory

… death and language maintenance: theoretical, practical …

Lyle Campbell

When Languages Die

K. David Harrison

Chapter 1: Gives an overview of global language extinction, where and why it is happening, and why it matters. Also introducing for the first time the concept of "Language Hotspots".

Ameera F. A

Applied Psycholinguistics

R. Bruce Thompson

International Social Science Journal

Luisa Maffi , Luisa Mafi

Peter K Austin

RELATED PAPERS

Cássia Farias

Henrik Fahlbeck

Revista Alcance

Thelma Valéria Rocha

Chemical Communications

A. Katrusiak

Cement and Concrete Composites

Chao-Lung Hwang

george utsamen

16.Avrillya Ananta

International Journal of Molecular Sciences

Rolland Gyulai

Tanya Behrisch

Lua Nova: Revista de Cultura e Política

Gabriel cohn

Intelligent Automation & Soft Computing

Jong-Hwan Kim

Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz

Mariane Stefani

Revista Cientifica

Rosa Elena Sánchez

Form@re : Open Journal per la Formazione in Rete

Chiara Patuano

T. Florian Jaeger

Toxicology Letters

Michael Kenyi

Clinical Genetics

Dursun Alehan

eTropic: electronic journal of studies in the Tropics

Jessica Faleiro

Cultura_Ciencia_Deporte

Daniel Linares Girela

Accounting. Analysis. Auditing

Viatcheslav Sokolov

Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry

Michael Welch

Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences

M. Lluïsa Sagristà

Africa’s Public Service Delivery and Performance Review

Mareve Biljohn

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Why Does a Language Die?

On the slow demise of tayap in papua new guinea.

I was in Gapun to try to answer a specific question, namely: Why does a language die? It took me a long time to realize that that is the wrong question to ask. Or it is to ask a question that has an obvious answer: a language dies because people stop speaking it.

Of course, one could ask why people stop speaking a language, and that would be a bit more interesting. But when that question is asked by linguists, who are among the few people seriously concerned about language death (along with a few language activists who have discovered, usually too late, that their ancestral tongue is moribund, and brittle), the tenor of the question is always a disappointment, or a scold.

When a linguist or a language activist asks: “Why do speakers of a language stop speaking it?” what they usually really mean is: “Why have speakers of that language failed us? Why have they allowed an irreplaceable artifact, an invaluable jewel in the treasure chest of humanity, an exquisite creation that ought to have been preserved forever—or at least until we get around to documenting all its characteristic phonemes, its possibly unique morphology, and its undoubtedly idiosyncratic syntax—why have those poor shortsighted ingrates who should have known better, in spite of whatever prejudices they may have faced, maybe in spite, even, of the threat of genocide, why oh why didn’t they understand how valuable their language is and teach it to their damn children?”

These days, many linguists who write about language death do so without even considering much the people who speak the languages. They are fond of likening endangered languages to endangered species: an obsolescent Uzbek language is compared to a threatened orchid; a dwindling Papuan language is like a California condor. At a time when we are all encouraged to concern ourselves with the environment and sustainability, many linguists seem to believe that the way to elicit sympathy and support for dying languages (whatever that might mean in practice) is to talk about them in terms of biodiversity and species loss.

There are certainly worse ways of thinking about languages than as fleshy flowers or rare birds. But a difficulty with comparing endangered languages to endangered species is that metaphors like those direct our attention to the natural world. The natural world, however, is precisely where we should not look in order to understand why languages die. After all, tender young orchids are not sent to schools where they are taught in a cosmopolitan language they’ve never heard, and where the only thing they end up learning is how misguided their traditional orchid ways are. California condors are not converted to Christianity and informed that their traditional condor way of life is Satanic.

To be fair, none of those things happen to languages either. But they do happen to people who speak the languages that linguists and language activists are concerned about.

By encouraging us to think in terms of ecosystems rather than political systems, comparisons of endangered languages to endangered species obscure the simple realization that language death is anything but a natural phenomenon . It is, on the contrary, a profoundly social phenomenon. Languages do not die because they exhaust themselves in the fullness of time or are killed off by predatory languages of greater phonological scope or syntactic richness. Languages die because people stop speaking them.

Rather than exploring why a language dies, I came to realize that the question I needed to ask, instead, was: How does a language die? I needed to discover what had to happen in a community, among speakers of a language, that resulted in parents ceasing to teach their language to their children. Where does language death start? How is it sustained? Does it have to involve a conscious decision on anyone’s behalf? Can a language die without anybody really wanting it to?

By my estimate, Tayap will be stone-cold dead in 50 years’ time. When I first arrived in Gapun, the language was spoken by about 90 people, out of a population of 130. Now, 30 years later, it has about 45 speakers, out of a population of about 200. The village grows, the language shrinks.

As far back as anyone in Gapun has been able to remember, though, Tayap has never had more than, at most, about 150 speakers: the entire population of Tayap speakers, when the language was at its peak, would have fit into a single New York City subway car.

Tiny as that count is, such a small language was not unusual for Papua New Guinea. Most languages spoken in the country have fewer than 3,000 speakers. And linguists estimate that about 35 percent of the languages (which means about 350 of them) have never had more than about 500 speakers.

Contrary to received wisdom, and common sense, this constellation of tiny languages was not the result of isolation; it didn’t arise because villages were separated from one another by mountain barriers or impenetrable jungle walls. Quite the opposite: throughout Papua New Guinea, the areas that have the highest degree of linguistic diversity (that is, the most languages) are the ones where people can get around relatively easily, by paddling a canoe along rivers and creeks, for example. The areas where travel is more difficult, for example in the mountains that run like a jagged spine across the center of the country, is where the largest languages are found (the biggest being a language called Enga, with over 200,000 speakers).

The conclusion that linguists have drawn from this counterintuitive distribution of languages is that people in Papua New Guinea have used language as a way of differentiating themselves from one another. Whereas other people throughout the world have come to use religion or food habits or clothing styles to distinguish themselves as a specific group of people in relation to outsiders, Papua New Guineans came to achieve similar results through language. People wanted to be different from their neighbors, and the way they made themselves different was to diverge linguistically.

Large swathes of neighboring groups throughout the mainland share similar traditional beliefs about what happens after one dies; they think related things about sorcery, initiation rituals, and ancestor worship; they have roughly similar myths about how they all originated; and before white colonists started coming to the country in the mid-1800s, they all dressed fairly similarly (and they all do still dress similarly, given the severely limited variety of manufactured clothing available to them today—mostly T-shirts and cloth shorts for men, and for women, baggy, Mother Hubbard–style “meri blouses” introduced by missionaries to promote modesty and cover up brazenly exposed breasts). Neighboring peoples hunt the same pigs and cassowaries that inhabit the rainforest; and they all eat sago, or taro or sweet potato—whichever of those staples their land is capable of growing.

In terms of the languages they speak, though, Papua New Guineans are very different from one another.

While the different groups of people who live in the area where the Tayap language is spoken are not isolated from one another, Tayap itself is a linguistic isolate, which means that it isn’t clearly related to any other language. Its lexicon is unlike any other language’s, and it has a number of other grammatical peculiarities that make it unique among Papuan languages in the region.

No one can explain why Tayap is an isolate. But until the end of World War II, when the villagers began to grow cash crops and relocated their village closer to the mangrove lagoon to try (unsuccessfully) to entice buyers to come buy the rice and, later, the peanuts that they grew so hopefully, Gapun used to lie on top of the highest mountain in the entire lower Sepik basin. At only about 500 meters above sea level, this mountain isn’t particularly high today, but several thousand years ago, it was its own island.

That an isolate language is spoken on the site of what used to be an isolated island suggests that perhaps Tayap is a particularly ancient, autochthonous language that already was in place in some form before the sea receded and the Sepik River was formed, facilitating the various waves of migration from Papua New Guinea’s inland to the coast that began occurring several millennia ago.

Whatever its origin, and despite its minuscule size, the fact that Tayap is as fully formed a language as English, Russian, Navajo, or Zulu means that it must have developed and remained stable for a very long time, for hundreds, maybe thousands, of years. All those years of efflorescence came to an end, though, suddenly and decisively, in the 1980s. By the middle of that decade, children who grew up in the village, for the first time in history, were no longer learning Tayap as their first language. What they were learning, instead, was a language called Tok Pisin.

Tok Pisin has an estimated four million speakers in Papua New Guinea, and it is the most widely spoken language in the country. Unlike Tayap or any of the other native languages that are spoken across the country, though, Tok Pisin—whose name literally means “Talk Pidgin” or “Bird Talk”—has a very short history. Like most of the other pidgin languages that still exist today, such as Jamaican Creole in the Caribbean, or Cameroon Pidgin English in Africa, Tok Pisin arose in the late 1800s as a plantation language. In the Pacific, European colonialists brought together large numbers of men from very different language groups to labor on their plantations; the laborers processed copra (the smoked and dried meat of coconuts, pressed for oil) or collected sea cucumber, a culinary delicacy in Asian cooking, which fueled a massive industry throughout the south Pacific during the mid- to late 1800s.

What did the thousands of men—who had no common language but had to work together, following orders given by their European overseers—do? They invented a new language. That language took much of its vocabulary from the language of the European order givers (so tok means “talk”; sanap means “stand up”; pik means “pig”; misis means, tellingly, “white woman”; and masta , even more tellingly, means “white man”) But its grammar was firmly rooted in the local languages that the men themselves spoke back home.

From its genesis in the late 1800s, Tok Pisin was an object of ridicule for many Europeans and Australians. The prevalence and, to their mind, the distortion of English-based words fooled English speakers into thinking (and many still think) that the language was simply a baby-talk version of English. And most of them spoke it as such, barking orders like “Bring him he come”—their tin ears and racial prejudices preventing them from perceiving the correct form, Kisim i kam . From the perspective of the Papua New Guinean men who spoke the language among themselves, what white people spoke to them was baby talk. They had a derogatory name for it: tok masta (“white man talk”), they called it dismissively, sniggering behind white backs at how badly white people spoke the language they used to boss black people around.

As the decades passed, this invented language set. Verbs gelled, word order settled, a grammar coagulated. Men who were released from their labor contracts brought the language back home with them, spreading it like rhizomes from the plantation to the villages. And just like the bolts of factory-made cloth, machetes, axes, and ceramic seashells that they received as payment when they were sent home, the men brought back Tok Pisin as a prestige object. It was a prized possession, the key to another world. Men who had been away on the plantation together spoke the language to one another in the village, to convey their worldliness and to intimidate their country-bumpkin relatives and neighbors who’d never ventured more than perhaps a few days’ walk beyond the village into which they had been born.

__________________________________

Excerpted from A Death in the Rainforest © 2019 by Don Kulick. Reprinted by permission of Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. All rights reserved.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Previous Article

Next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

How a New Generation of Nigerian Writers Is Salvaging Tradition from Colonial Erasure

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Katrina Esau, one of the last remaining speakers of a Khoisan language that was thought extinct nearly 40 years ago, teaches her native tongue to a group of school children in Upington, South Africa on 21 September 2015. Photo by Mujahid Safodien/AFP/Getty

The death of languages

Endangered languages have sentimental value, it’s true, but are there good philosophical reasons to preserve them.

by Rebecca Roache + BIO

The year 2010 saw the death of Boa Senior, the last living speaker of Aka-Bo, a tribal language native to the Andaman Islands in the Bay of Bengal. News coverage of Boa Senior’s death noted that she had survived the 2004 tsunami – an event that was reportedly foreseen by tribe elders – along with the Japanese occupation of 1942 and the barbaric policies of British colonisers. The linguist Anvita Abbi, who knew Boa Senior for many years, said: ‘After the death of her parents, Boa was the last Bo speaker for 30 to 40 years. She was often very lonely and had to learn an Andamanese version of Hindi in order to communicate with people.’

Tales of language extinction are invariably tragic. But why, exactly? Aka-Bo, like many other extinct languages, did not make a difference to the lives of the vast majority of people. Yet the sense that we lose something valuable when languages die is familiar. Just as familiar, though, is the view that preserving minority languages is a waste of time and resources. I want to attempt to make sense of these conflicting attitudes.

The simplest definition of a minority language is one that is spoken by less than half of some country or region. This makes Mandarin – the world’s most widely spoken language – a minority language in many countries. Usually, when we talk of minority languages, we mean languages that are minority languages even in the country in which they are most widely spoken. That will be our focus here. We’re concerned especially with minority languages that are endangered, or that would be endangered were it not for active efforts to support them.

The sorrow we feel about the death of a language is complicated. Boa Senior’s demise did not merely mark the extinction of a language. It also marked the loss of the culture of which she was once part; a culture that was of great interest to linguists and anthropologists, and whose extinction resulted from oppression and violence. There is, in addition, something melancholy about the very idea of a language’s last speaker; of a person who, like Boa Senior, suffered the loss of everyone to whom she was once able to chat in her mother tongue. All these things – the oppression until death of a once thriving culture, loneliness, and losing loved ones – are bad, regardless of whether they involve language death.

Part of our sadness when a language dies, then, has nothing to do with the language itself. Thriving majority languages do not come with tragic stories, and so they do not arouse our emotions in the same ways. Unsurprisingly, concern for minority languages is often dismissed as sentimental. Researchers on language policy have observed that majority languages tend to be valued for being useful and for facilitating progress, while minority languages are seen as barriers to progress, and the value placed on them is seen as mainly sentimental.

Sentimentality, we tend to think, is an exaggerated emotional attachment to something. It is exaggerated because it does not reflect the value of its object. The late philosopher G A Cohen describes a well-worn, 46-year-old eraser that he bought when he first became a lecturer, and that he would ‘hate to lose’. We all treasure such things – a decades-old rubber, our children’s drawings, a long-expired train ticket from a trip to see the one we love – that are worthless to other people. If the value of minority languages is mainly sentimental, it is comparable to the value that Cohen placed on his old eraser. It would be cruel to destroy it deliberately, yet it would be unreasonable for him to expect society to invest significant resources preserving it. The same might be true of minority languages: their value to some just doesn’t warrant the society-wide effort required to preserve them.

T here are a couple of responses to this. First, the value of minority languages is not purely sentimental. Languages are scientifically interesting. There are whole fields of study devoted to them – to charting their history, relationships to other languages, relationships to the cultures in which they exist, and so on. Understanding languages even helps us to understand the way we think. Some believe that the language we speak influences the thoughts we have, or even that language is what makes thought possible. This claim is associated with the so-called Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which the linguist and cognitive scientist Steven Pinker at Harvard has described as ‘wrong, all wrong’.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is certainly linked to a variety of dubious myths and legends, such as the pervasive but false belief that Eskimos have a mind-bogglingly large number of words for snow. But its core idea is not as wrong-headed as Pinker believes. While there is little evidence that thought would not be possible at all without language, there is plenty of evidence that language influences the way we think and experience the world. For example, depending on which language they are using, fluent German-English bilinguals categorise motion differently, Spanish-Swedish bilinguals represent the passage of time differently, and Dutch-Farsi bilinguals perceive musical pitch differently. Even Pinker apparently finds the link between thought and language compelling: he believes that thoughts are couched in their own language, which he calls ‘mentalese’. In any case, this debate can be settled only empirically, by studying as many different languages (and their speakers) as possible. Which leaves little doubt that languages are valuable for non-sentimental reasons.

Second, let’s take a closer look at sentimental value. Why do we call some ways of valuing ‘sentimental’? We often do this when someone values something to which they have a particular personal connection, as in the case of Cohen and his eraser. Cohen calls this sort of value personal value . Things that have personal value are valued much less by people who do not have the right sort of personal connection to them. Another way of being sentimental is valuing something that is connected to someone or something that we care about. This sort of value is behind the thriving market in celebrity autographs, and it is why parents around the world stick their children’s drawings to the fridge.

The term ‘sentimental’ is gently pejorative: we view sentimentality as an inferior sort of value (compared with, say, practical usefulness), although we are often happy to indulge each other’s sentimental attachments when they don’t cause us inconvenience. Parents’ sentimentality about their kids’ drawings is not inconvenient to others, but sentimentality about minority languages often is, since they require effort and resources to support. This helps to explain why minority languages, to some people, are just not worth the bother.

However, sentimentality is not so easily set aside. Our culture is underpinned by values that, on close inspection, look very much like sentimentality. Consider the following comparison. We can all agree that it is sentimental of Cohen to insist (as he did) that he would decline an opportunity to upgrade his old eraser to a brand-new one. Yet were the Louvre to decline an offer from a skilled forger to exchange the Mona Lisa for an ‘improved’ copy that eliminated the damage suffered over the years by the original, we are unlikely to view this decision as sentimental. On the contrary, were the museum to accept the forger’s offer, we could expect to find this shocking story make headlines around the world. Our contrasting attitudes disguise the fact that the values involved in these two cases are very similar. In each case, an item with a certain history is valued over another, somewhat improved, item with a different history.

Sentimentality explains why it is better to support endangered natural languages rather than Klingon

This sort of value is ubiquitous. We preserve such things as medieval castles, the Eiffel Tower and the Roman Colosseum not because they are useful but because of their historical and cultural significance. When ISIS fighters smashed 5,000-year-old museum exhibits after capturing Mosul in 2015, outraged journalists focused on the destroyed artefacts’ links with ancient and extinct cultures. Historical and cultural significance is part of why we value languages; indeed, the philosopher Neil Levy has argued that it is the main reason to value them. These ways of valuing things are labelled sentimental in some contexts. If minority languages are valuable partly for sentimental reasons then they are in good company.

While valuing minority languages is often viewed as sentimental, it is just as often admired. The documentary We Still Live Here (2010) tells the story of the revival of the Wampanoag language, a Native American language that was dead for more than a century. The film celebrates the language’s revival and the efforts of Jessie Little Doe Baird, who spearheaded its revival, whose ancestors were native speakers, and whose daughter became the revived language’s first native speaker. Baird received a MacArthur Fellowship to carry out her project, and her success attracted widespread media attention and honours, including a ‘Heroes Among Us’ award from the Boston Celtics basketball team.

Across the Atlantic, Katrina Esau, aged 84, is one of only three remaining speakers of N|uu, a South African ‘click’ language. For the past decade, she has run a school in her home, teaching N|uu to local children in an effort to preserve it. In 2014, she received the Order of the Baobab from the country’s president, Jacob Zuma. Both Baird and Esau have received global news coverage for their efforts, which are acclaimed as positive contributions to their community.

It is fortunate that sentimentality can be a respectable sort of attitude. Without it – that is, focusing solely on the scientific and academic value of languages – it is difficult to explain why it is better to preserve currently existing minority languages rather than revive long-dead languages that nobody living today cares about, or why it is better to support endangered natural languages such as the Lencan languages of Central America rather than artificial languages such as Volapük (constructed by a Roman Catholic priest in 19th-century Germany) and Klingon (the extra-terrestrial language in Star Trek ), or why it is better to preserve endangered natural languages than to invent completely new languages.

Even people who are unsympathetic to efforts to support minority languages are, I imagine, less baffled by Esau’s desire to preserve N|uu than they would be by a campaign for the creation and proliferation of a completely new artificial language. No such campaign exists, of course, despite the fact that creating and promoting a new language would be scientifically interesting. The reason why it’s better to preserve currently existing natural languages than to create new ones is because of the historical and personal value of the former. These are exactly the sort of values associated with sentimentality.

M inority languages, then, are valuable. Does that mean that societies should invest in supporting them? Not necessarily. The value of minority languages might be outweighed by the value of not supporting them. Let’s look at two reasons why this might be the case: the burden that supporting minority languages places on people, and the benefits of reducing language diversity.

While we might value minority languages for similar reasons that we value medieval castles, there is an important difference in how we can go about preserving the two types of thing. Preserving a minority language places a greater burden on people than does preserving a castle. We can preserve a castle by paying people to maintain it. But we can’t preserve a minority language by paying people to carry out maintenance. Instead, we must get people to make the language a big part of their lives, which is necessary if they are to become competent speakers. Some people do this voluntarily, but if we want the language to grow beyond a pool of enthusiasts, we must impose lifestyle changes on people whether they like it or not. Often this involves legislation to ensure that children learn the minority language at school.

Such policies are controversial. Some parents think that it would be better for their children to learn a useful majority language rather than a less useful minority language. However, for native English speakers, the most commonly taught majority languages – French, German, Spanish, Italian – are not as useful as they first seem. A language is useful for a child to learn if it will increase the amount of people she can communicate with, increase the amount of places where she can make herself understood, and perhaps also if it is the language of a neighbouring country. Yet, because English is widely spoken in countries such as France, Germany, Spain and Italy, even an English-speaking monoglot can make himself understood pretty well when visiting these countries. If he decides to invest effort in learning one of these languages, he can expect relatively little return on his investment in terms of usefulness.

If people in English-speaking countries are concerned about teaching children useful languages, we should teach them languages whose native speakers less commonly understand English, such as Arabic and Mandarin – languages that are not commonly taught in schools in the UK and the US. There are, of course, some native English speakers who believe that learning any foreign language is pointless because English is so widely understood – think of the stereotypical British ex-pat living in Spain but not learning Spanish – but this view is clearly not held by parents who are supportive of their children learning some foreign language. So people who support English-speaking children learning French, German and Spanish, but who don’t support them learning a local minority language, will have difficulty defending their position in terms of usefulness. In that case, why is it so widely seen as a good thing for English-speaking children to learn majority languages such as French, German and Spanish? I think it is the same reason that many claim it’s a good thing to learn a minority language: to gain an insight into an unfamiliar culture, to be able to signal respect by speaking to people in the local language, to hone the cognitive skills one gains by learning a language, and so on.

Languages have not become extinct or endangered gently. The history of language death is a violent one

There is also, I think, a special kind of enrichment that children – and people in general – get from learning a minority language connected to their community. They get a new insight into their community’s culture and history. They also gain the ability to participate in aspects of their culture that, without knowing the language, are closed off and even invisible; namely, events and opportunities conducted in the minority language. I write from experience here, having spent the past 18 months or so trying to learn Welsh. I was born and raised in Wales yet, until recently, my main contact with the language consisted mainly of ignoring it. Returning to Wales now, armed with my admittedly modest understanding of Welsh, I have a sense of this long-familiar country becoming visible to me in a new way. I feel pleased and interested when I encounter Welsh speakers. I am happy that my nephew learns Welsh at school. These strong conservative intuitions are – for a non-conservative like me – surprising and somewhat alien. But they are not unique: they centre on benefits that are frequently mentioned by campaigners for minority languages.

Finally, let’s consider a very different reason to resist the view that we should support minority languages. Language diversity is a barrier to successful communication. The Bible has a story about this: as a punishment for building the Tower of Babel, God ‘confused the language of all of the Earth’ by causing people to speak a multiplicity of languages where once they had all spoken the same one. It’s rare these days to encounter the view that our diversity of languages is a curse, but it’s notable that in other areas of communication – such as in the representation of numbers, length and volume – we favour standardisation. The advantages to adopting a single language are clear. It would enable us to travel anywhere in the world, confident that we could communicate with the people we met. We would save money on translation and interpretation. Scientific advances and other news could be shared faster and more thoroughly. By preserving a diversity of languages, we preserve the obstacles to communication. Wouldn’t it be better to allow as many languages as possible to die out, leaving us with just one universal lingua franca ?

It would be difficult, however, to implement a lingua franca peacefully and justly. The very idea calls to mind oppressive past policies, such as the efforts of the Soviet Union to suppress local languages and to force all its citizens to communicate only in Russian. Extinct and endangered languages have not, on the whole, become extinct or endangered gently, by subsequent generations choosing freely to switch to a more dominant language. The history of language death is a violent one, as is reflected in the titles of books on the subject: David Crystal’s Language Death (2000), Daniel Nettle and Suzanne Romaine’s Vanishing Voices: The Extinction of the World’s Languages (2000), and Tove Skutnabb-Kangas’s Linguistic Genocide in Education (2008).

It would, then, be difficult to embrace a lingua franca without harming speakers of other languages. In addition, if we were serious about acting justly, it would not be enough merely to abstain from harming communities of minority language speakers. Given the injustices that such communities have suffered in the past, it might be that they are owed compensation. This is a view commonly held by minority-language campaigners. It is debatable what form this compensation should take, but it seems clear that it should not include wiping out and replacing the local language.

Perhaps, if one were a god creating a world from scratch, it would be better to give the people in that world one language rather than many, like the pre-Babel civilisations described in the Bible. But now that we have a world with a rich diversity of languages, all of which are interwoven with distinct histories and cultures, and many of which have survived ill-treatment and ongoing persecution, yet which continue to be celebrated and defended by their communities and beyond – once we have all these things, there is no going back without sacrificing a great deal of what is important and valuable.

Psychiatry and psychotherapy

The therapist who hated me

Going to a child psychoanalyst four times a week for three years was bad enough. Reading what she wrote about me was worse

Michael Bacon

Consciousness and altered states

A reader’s guide to microdosing

How to use small doses of psychedelics to lift your mood, enhance your focus, and fire your creativity

Tunde Aideyan

The scourge of lookism

It is time to take seriously the painful consequences of appearance discrimination in the workplace

Andrew Mason

Thinkers and theories

Our tools shape our selves

For Bernard Stiegler, a visionary philosopher of our digital age, technics is the defining feature of human experience

Bryan Norton

Family life

A patchwork family

After my marriage failed, I strove to create a new family – one made beautiful by the loving way it’s stitched together

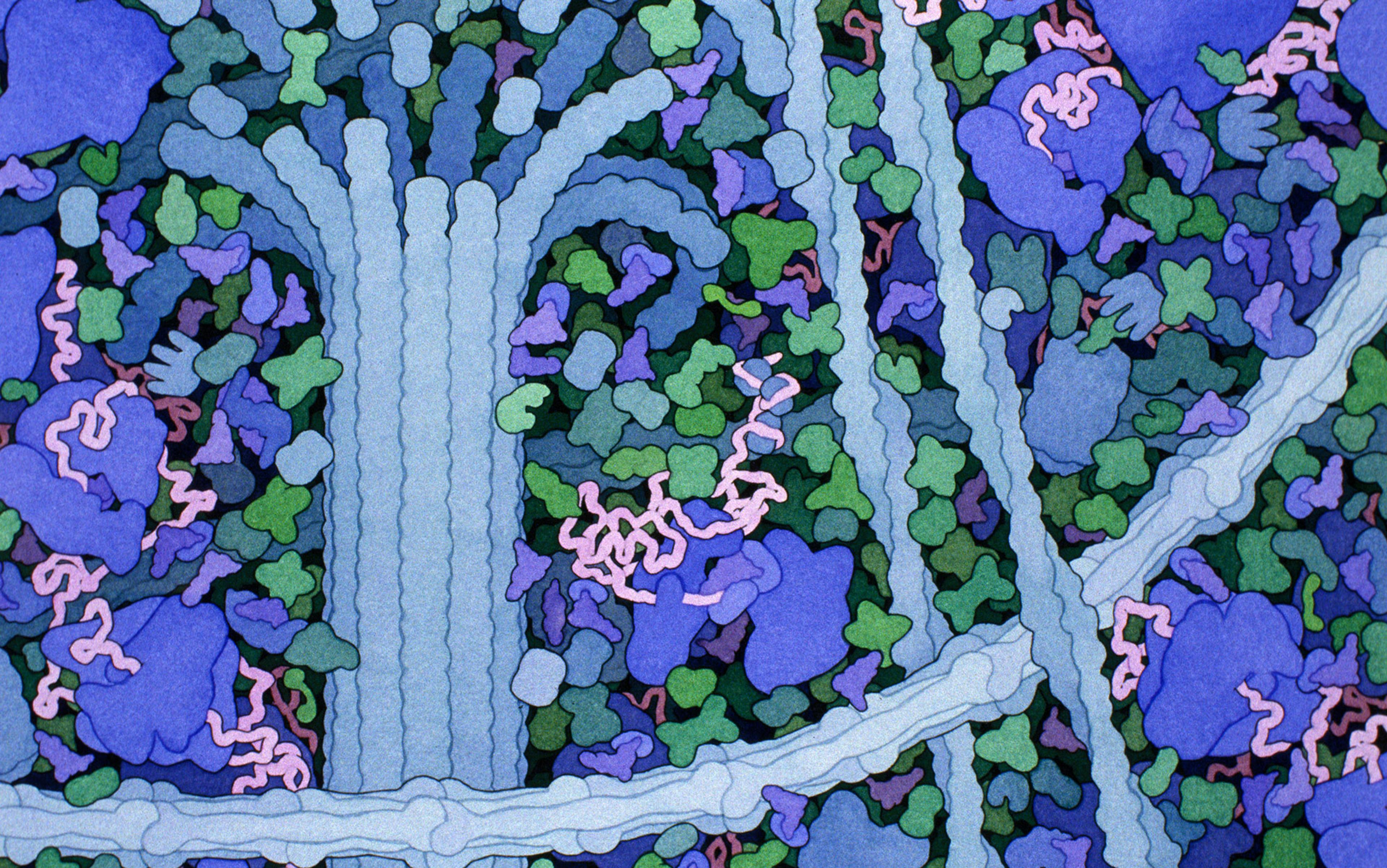

The cell is not a factory

Scientific narratives project social hierarchies onto nature. That’s why we need better metaphors to describe cellular life

Charudatta Navare

Which Language Do You Want to Learn?

- Inside Babbel

- Babbel Bytes

ARTICLES ABOUT

What causes a language to die.

It’s estimated that every two weeks, a language dies. This is an oft-repeated, urgent statistic. But language death, unlike the death of humans, is not easy to wrap your head around. Most people in the world never interact with someone who speaks an endangered language; 96 percent of people in the world speak the 100 largest of the over 7,000 languages in existence today. Much linguistics work today is simply trying to record these languages before they vanish. If a language dies in the forest and no one is there to record it, what does it matter to the world?

Don Kulick, a linguist who has written about language death before, decided to write for people who aren’t necessarily linguists. The result is A Death in the Rainforest , which tells the story of Gapun, a single village in Papua New Guinea. Kulick traveled there several times over the course of decades to study the endangered language Tayap. The book is about the language, and it’s also about the forces that are reshaping even the remotest parts of the human world.

How Does A Language Die?

Don Kulick first traveled to Papua New Guinea in 1986 as a doctoral student. He went there to answer the question, “How does a language die?” Papua New Guinea is a prime place to be to find out. In a country that isn’t very large, there are nearly 1,000 languages spoken.

Kulick went to Gapun specifically because it’s almost ideal for observing language death. The community is relatively small, and the local language of Tayap is spoken far more by the elders than the children of the village. Tayap is slowly being edged out by Tok Pisin, which is one of the official languages of the country (along with English). In the decades spanning Kulick’s visits, the number of Tayap speakers dropped from 90 to 45 in a population of fewer than 200 people.

Many chapters in A Death in the Rainforest look at the day-to-day linguistic work that goes into studying a dying language. Kulick meets with Tayap speakers to attempt to document the language before it vanishes. This means learning an entirely new language and creating a writing system to express it. This task is only made trickier when villagers disagree about what a certain word is in Tayap; trying to figure out the Tayap word for “rainbow” sends Kulick on a wild goose chase.

Then, Kulick has to investigate why the language is dying. There are a range of reasons, but it essentially boils down to the fact that children are not being taught the language as much anymore. Stretch that process over a few generations, and just about any language subjected to it will die out.

The result of this is Kulick’s first work, Language Shift and Cultural Reproduction: Socialization, Self, and Syncretism in a Papua New Guinean Village . It’s the kind of name that would scare off anyone but an academic, and it doesn’t place much emphasis on the personal impact language death has on its speakers. This isn’t Kulick’s own flaw, because he’s just mimicking an accepted version of linguistic research.

But in A Death in the Rainforest , Kulick seeks to redress the situation and allow the personalities of Gapun to stand out. He writes that “rather than ‘speak for’ the villagers I write about, this book ‘engages with’ them.” In a field that requires as much human contact as linguistics, this engagement is invaluable, and it’s too often skimmed over in favor of academic rigor in linguistics writing.

Why Does A Language Die?

The villagers in Gapun believe that no one dies a natural death. Instead, each death is an evil act done by sorcerers in nearby villages. Then, the bodies crack open and the people travel underground to Europe, transforming into that villager’s true form: a white person. All this is to say that when Don Kulick arrived in Gapun, they thought he was a deceased villager who had returned to lead the community into the future.

Gapun is very difficult to get to, but Kulick was not the first white person they’d seen. Christian missionaries , explorers and NGO members had passed through before, and some villagers even went to (not very well-run) schools that exposed them to what the world is like outside of their home. And this is enough to have created a situation in which the people of Gapun are sick of their current situation, and want to enter a world with cars and technology that make their lives easier. Tok Pisin is useful because it goes beyond the boundaries of the village.

A Death in the Rainforest covers a range of topics, but it’s hard to avoid the veneration of white culture and how it has infiltrated this community. Even the more fun chapters carry on this theme: Kulick’s analysis of the love letters sent by young men in Gapun shows that they venerate English, even if they don’t understand a word of it.

You can sense Kulick wants to give the reader a look into the humanity of Gapun. Despite some missteps — a chapter that strongly exoticizes the cuisine of Gapun feels out of place, for example — Kulick does his best to acknowledge what it means for him to live in this community.

Kulick is a white man who can come and go as he pleases, and while he does do his best to give back to the community, he is clearly gaining a personal advantage by studying Tayap. And on some occasions, his presence even puts people in the community in danger as stories about the rich white visitor spread through the area. This research, then, was morally ambiguous at best, and that’s why by the end of his last visit in 2010, he decides to never return. Not because he doesn’t care about the villages, but because he knows his impact on the village is ultimately harmful.

Why Should We Care?

Toward the end of this book, Kulick writes, “Linguists who write books about language death usually include a chapter that asks some version of the question: ‘Why should we care?’” He then rattles off the usual answers about cultural value and historical importance, but points out that those are grand, theoretical answers that don’t address the more dire problems. Languages are dying not because of some unstoppable entropy — it’s the long-lasting effects of colonialism that still ripple today. The people of Gapun had been converted to Christianity, conned by corrupt politicians and hurt by NGOs that never stayed for long enough to help out much. With the death of Tayap comes the death of a way of life, as villagers have tried to follow the examples of others only to have the rug pulled out from under them.

A Death in the Rainforest is a microcosm, but that’s largely the point. The situation in Gapun is not the same as the thousands of other endangered languages that are being lost. But where many analyses of language death merely shake their heads over the sadness of it all, this one feels more vital. Perhaps the Gapun belief about death refers more aptly to languages. They do not die of natural causes, but instead are stifled by outside forces. The only difference is that when a language passes away, it doesn’t come back.

This website uses cookies in order to provide you the most relevant information. Please accept cookies for better performance. Read more »

Language Maintenance, Shift, and Death Sociology Essay

The phenomenon of language.

Language is a complex phenomenon, which unites all human beings and impacts their cognitive and communication processes. The ability to communicate with complex signals, which are incorporated in various languages, significantly differentiates humans from other types of living beings on the planet. Apparently, language factor is one of the most important features for any civilization. The reason for this assumption is that language fosters cognitive processes and enables operation with complex and abstract notions. Moreover, the ability to communicate with the help of advanced language systems allows transforming abstract notions into more concrete objects. Thus, enhanced abstract and concrete thinking together with communication enables to create such societies and conditions for their living as cities. Consequently, numerous sciences study the phenomenon of language aiming at defining its basic concepts, systemic features, and other aspects. Currently, it is the object of interest for psychology, linguistics, sociology, history, and other branches of science including their broad range of narrower sub-branches. Furthermore, current reality and history of languages show that they undergo different processes, which include changes in their lexis and systemic structure. Among the most significant aspects demonstrating these processes are language maintenance, language shift, and language death. Thus, this paper investigates these phenomena characterizing them and giving specific examples for them. It is evident that language maintenance, language shift, and language death are the most significant aspects for sociolinguistics. Their analysis would enhance the general understanding of their role for sociolinguistics as well as for such branches as cognitive psychology and history of languages.

Before characterizing the processes, which influence the development and the decay of language systems, one has to characterize the language phenomenon generally and from the position of sociolinguistics. Thus, the language is a systemic phenomenon, which involves the usage of different signs in terms of social agreement. Malathi (2015) defines language as “the communicative means of man, which plays a great part in our life and distinguishes man from the animals.” Moreover, the scholar claims that any current language is the result of the historical movement, and it changes throughout thousands of years (Malathi, 2015). The amount of languages in the world is constantly changing because of social and other interactive reasons. In the contemporary world, it is estimated that there are about 7,000 different languages with 90% of them used by less than 100,000 people (“Languages of the world – Interesting facts about languages”, 2014). What is more, scholars indicate that about 46 languages have only one speaker whereas the majority of humanity speaks about 150-200 languages. The reasons for such statistics vary, but they are inevitably connected with the phenomena of language maintenance, shift, and death. Each language is characterized by structure and its vocabulary filling. Studies indicate that the most part of languages have similar grammatical structure even if they significantly differ in terms of vocabulary and are spoken on different continents (“Languages of the world – Interesting facts about languages”, 2014). One of the critical aspects of any language is its ability to change depending on various internal and external factors. Language changes occure constantly and involve its every level, which may include phonetic, graphic, lexical, grammatical, and other issues (Malathi, 2015). In their turn, language studies can be performed by means of comparing related but different languages existing at the same period of time. Likewise, language studies may focus on historical context comparing one language to another throughout their different stages of historical development. It is evident that many changes in languages reflect their general tendency for the development of more abstract and universal systems (Malathi, 2015). Thus, language maintenance, shift, and even death are the results of this tendency aiming at reaching versatility of the peculiar language system.

Language Maintenance and Language Shift

First, there is a need for the characteristics of language maintenance and language shift, as they are one of the basic aspects, which characterize any language system. Thus, the studying of these issues is connected with the relationship between the change of stability in habitual language use and ongoing psychological, social, and cultural processes (Fishman, 2013). Subsequently, language maintenance is the factor, which preserves a system of a particular language in its stable state and restrains the influence of exterior factors. Despite the fact it is impossible to completely bypass any of the exterior changes, it preserves the core of the language system allowing it to function without significant transformations. A peculiar feature of contemporary linguistics is that is puts particular stress on the social, political, cultural, and linguistic phenomena of heritage language maintenance and loss (Gonzalez, 2015). The reason for this is that the modern world has a variety of communities, which are characterized by the coexistence of the speakers of different languages. Therefore, there is a danger of losing identity of any particular language because of such active interaction. As characterized by the scholars, the exposure of the discussed phenomena may be observed in the case of coexistence of two linguistically distinguishable populations in contact (Malathi, 2015). Consequently, constant interaction causes the speakers to adopt peculiar grammar structures or lexemes, thus shifting the identity of their language. One of the examples studying the phenomena of language maintenance and shift explores the existence of the Slovenian minority group in one of the regions in northern Italy. Thus, as it was explored by the study of Jagodic (2011), the investigated processes among the Slovenian speakers revealed a persistent degree of language shift. As it was reported by the author, “the analysis of the language use patterns among the Slovenian community members, presented in the first section, has clearly revealed a slow, yet progressive advancing of the processes of the shift towards the use of the Italian language.” The implications of this study advise the community members about establishing activities aimed at language maintenance within the targeted community.

Moreover, it is evident that similar investigations addressing the issues of language maintenance and language shift indicate the fact that minor language communities are endangered by the bigger neighbors. The reason for the fears associated with this phenomenon is that any language is regarded as the core of culture and the basic cultural value (Bradley, Bradley, 2013). Therefore, analyzed issues are relevant for the communities having bilingualism and coexistence of minor and major language populations. Likewise, similar shifts may be observed if minor cultures experience difficulties with mastering their own languages whereas the neighboring language of a major culture is easier to learn. Moreover, such relations can be noticed in case the society supports, tolerates, or represses language minorities for their languages (Bradley, Bradley, 2013). Thus, the tendencies of language shift are observed in the case of Italians’ and Catalonians’ coexisting. The result of this coexistence is that despite former historical opposition between Catalan and Italic communities, the Catalan society has become mostly Spanish-speaking (Newman, Trenchs-Parera, 2015). Likewise, similar historical processes can be detected in the case of the English language history. Thus, Knooihuizen (2015) claims that despite the coexistence of Cornish English, Manx English, and Shetland Scots in Early Modern English period, they had an overall tendency towards unification. The result of this process was becoming of some grammatical forms and lexemes more common, whereas the others were substituted actualizing the scenario of standardization through language shift.

Order-Essays.com Offers Great PowerPoint Presentation Help!

We will create the best slides for your academic paper or business project!

Therefore, gradually, various dialects coexisting in Early Modern English period lost their varieties when facing the reality of the predominant language standard. On the contrary, there are cases in history when English was driven out from certain communities since it was the feature of minor social groups. Such case is described in the study of Perez (2015), who investigates the reasons for social rejection of the English language by the inhabitants of Paraguay’s New Australia. The scholar argues about the fact that at the end of the 20th century, almost 600 colonizers from the UK and Australia settled in Paraguay (Perez, 2015). Their initial goal was setting up the society of pure English-speakers. However, the sociolinguistic history of the community in Paraguay indicates that it was divided into speakers of Spanish and English. As a result of the domination of Spanish language in the country, the English community was underrepresented, which caused English language’s disappearance from Paraguay (Perez, 2015). Thus, even if language may have a majority of speakers worldwide, it may disappear from particular countries with no community support.

Furthermore, there is a need for the discussion of language maintenance and language shift in the time of globalization. Thus, it is evident that the world speakers favor a small list of mostly spoken languages. Among the top five spoken languages in the world are Mandarin, English, Hindustani, Spanish, and Russian with over 1 billion, 508, 497, 392, and 277 million speakers respectively (“Top 10 most spoken languages in the world”, 2008). This fact means that in case there is a community of minor language speakers, its language may be exposed to danger of extinction or language death. Therefore, there is a need for the characteristics of the reasons and factors causing language disappearance

Language Death

A peculiar value of any language lies in the fact that it represents the vision of the world depicted through the perception of the speakers. Thus, the language death is a significant negative event, which causes a loss of cultural individuality represented by it. The existence of any language is supported by a broad range of political, economic, demographic, and social factors (Crystal, 2012). Therefore, these factors may also cause or stimulate the loss of a language. Furthermore, since language cannot be separated from its speakers, one may presume that the first languages appeared with the first humans and their organized communities. Scholars assume that if humans started speaking 200,000 years ago and the first language appeared 100,000 years ago, there might be between 64,000 and 140,000 languages ever existing (Brons, 2014). It is evident that some part of them is already dead, whereas approximately 2,500 of the existing ones are considered endangered (Kornai, 2013). Moreover, there are scientists, who estimate that the total number of languages may be higher up to the proportion of 50-90% of the assumed world’s 6,900 languages (Romaine, 2013). According to various claims, the result of this may be not only social, economic, or political factors but, additionally, the language environment. For instance, Romaine (2013) indicates that environmental changes of the past, which caused hunger and diseases, changed the ecosystems of the existing societies. As a result, their migration and assimilation led to the death of various language groups. However, developing the concept of the ecology of language, Romaine (2013) blends it with other features such as sociological and psychological conditions of each language along with their impact.

Furthermore, some linguists mix sociolinguistic and biological theories in order to find the adequate explanation of the processes of the languages extinction. Thus, Ritchie (2014) refers to the study of Claude Hagege who traces the analogy between the existence of language and theories of evolution. Additionally, the author stresses that certain linguists explored this phenomenon through the prism of Darwinian concepts of natural selection, speciation, and extinction (Ritchie, 2014). A peculiar feature of his views is that he considered that a language may live even though it has no speakers but only written texts. In this sense, texts were regarded as autonomous reproductions of an extinct language. At the same time, Ritchie (2014) argues that the dying languages experience the processes of lexical, phonological, and grammatical erosion. As it is viewed by the scholar, these events are the result of the absence of intergenerational communication and the absence of younger speakers. Additionally, one should note that language death is a natural phenomenon, which is caused by the ignorance of a language towards social resistance and its assimilation into the dominant language (Canagarajah, 2015). Thus, despite scholar claims that psycholinguistic aspects of language assimilation require additional sociolinguistic research (Canagarajah, 2015), he discusses the phenomenon of linguistic emancipation.

The example of the result of language death may be the Maliseet language, the only speaker of which has lost his linguistic knowledge at a young age (Sodikoff, 2012). As a result, the former speaker of Maliseet has lost one’s cultural reference and identity by means of assimilation with other culture. Consequently, scholars indicate that pidgin- and creole-speaking people are among those speakers, whose languages remain on the fringe of the world’s languages (Sodicoff, 2012). Therefore, they suffer from the pressure of bigger cultural communities and more popular languages, which, in turn, endanger their historically natural community and language.

The best way to know how to write good essays is by getting a sample of an essay from competent experts online. We can give you the essay examples you need for future learning.

Free Essay Examples are here .

The discussed issue shows that the natural language shift towards more favored languages and cultures causes the overall language shift of minor language communities. As a result, younger speakers of these communities refuse to learn their own language and culture giving favor to more popular, useful, or easier language. At the same time, the endangered language itself experiences assimilative processes with the dominating language. The result of this is that its phonemic structure, grammatical structure, and the vocabulary obtain features from the host language. Thus, gradually, language shift causes language death. In order to resists these processes, minor language communities should develop language and culture preserving programs. These programs and initiatives should focus on language maintenance activities maintaining the unicity of the natural language of a peculiar community. As a result, the speakers would preserve cultural resistance towards the communities with major language. Therefore, these actions would allow language to live even in the case of having underrepresented community of its speakers.

Summarizing the presented information, the study comes to a conclusion that language maintenance, language shift, and language death are three significant factors for any society. The reason for this assumption is that any group of speakers has to have language maintenance with the aim of saving the unicity of their language and resisting assimilation. In contrast, language shift is a process of active relationship between the speakers of two languages characterized with a high degree of assimilation. A peculiar feature of this process is that minor language communities tend to lose the features of their languages when faced with major ones. As a result, gradual language shift towards the major culture causes the language death in minor culture. Such death is accompanied by the assimilation of phonemic and grammatical structures of the underrepresented language as well as its vocabulary. Therefore, minor communities require the establishment of measures and initiatives aimed at preserving the existence of their languages. Consequently, the activities towards enhancing language maintenance in minor language community would allow avoiding language death.

Get a Free Price Quote

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- 2024 election

- Solar eclipse

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

- Health Care

5 moving, beautiful essays about death and dying

Share this story.

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: 5 moving, beautiful essays about death and dying

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/45827388/shutterstock_159271091.0.0.jpg)

It is never easy to contemplate the end-of-life, whether its own our experience or that of a loved one.

This has made a recent swath of beautiful essays a surprise. In different publications over the past few weeks, I've stumbled upon writers who were contemplating final days. These are, no doubt, hard stories to read. I had to take breaks as I read about Paul Kalanithi's experience facing metastatic lung cancer while parenting a toddler, and was devastated as I followed Liz Lopatto's contemplations on how to give her ailing cat the best death possible. But I also learned so much from reading these essays, too, about what it means to have a good death versus a difficult end from those forced to grapple with the issue. These are four stories that have stood out to me recently, alongside one essay from a few years ago that sticks with me today.

My Own Life | Oliver Sacks

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3472666/vox-share__12_.0.png)

As recently as last month, popular author and neurologist Oliver Sacks was in great health, even swimming a mile every day. Then, everything changed: the 81-year-old was diagnosed with terminal liver cancer. In a beautiful op-ed , published in late February in the New York Times, he describes his state of mind and how he'll face his final moments. What I liked about this essay is how Sacks describes how his world view shifts as he sees his time on earth getting shorter, and how he thinks about the value of his time.

Before I go | Paul Kalanithi

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3472686/vox-share__13_.0.png)

Kalanthi began noticing symptoms — "weight loss, fevers, night sweats, unremitting back pain, cough" — during his sixth year of residency as a neurologist at Stanford. A CT scan revealed metastatic lung cancer. Kalanthi writes about his daughter, Cady and how he "probably won't live long enough for her to have a memory of me." Much of his essay focuses on an interesting discussion of time, how it's become a double-edged sword. Each day, he sees his daughter grow older, a joy. But every day is also one that brings him closer to his likely death from cancer.

As I lay dying | Laurie Becklund

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3473368/vox-share__16_.0.png)

Becklund's essay was published posthumonously after her death on February 8 of this year. One of the unique issues she grapples with is how to discuss her terminal diagnosis with others and the challenge of not becoming defined by a disease. "Who would ever sign another book contract with a dying woman?" she writes. "Or remember Laurie Becklund, valedictorian, Fulbright scholar, former Times staff writer who exposed the Salvadoran death squads and helped The Times win a Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the 1992 L.A. riots? More important, and more honest, who would ever again look at me just as Laurie?"

Everything I know about a good death I learned from my cat | Liz Lopatto

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3472762/vox-share__14_.0.png)

Dorothy Parker was Lopatto's cat, a stray adopted from a local vet. And Dorothy Parker, known mostly as Dottie, died peacefully when she passed away earlier this month. Lopatto's essay is, in part, about what she learned about end-of-life care for humans from her cat. But perhaps more than that, it's also about the limitations of how much her experience caring for a pet can transfer to caring for another person.

Yes, Lopatto's essay is about a cat rather than a human being. No, it does not make it any easier to read. She describes in searing detail about the experience of caring for another being at the end of life. "Dottie used to weigh almost 20 pounds; she now weighs six," Lopatto writes. "My vet is right about Dottie being close to death, that it’s probably a matter of weeks rather than months."

Letting Go | Atul Gawande

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3472846/vox-share__15_.0.png)

"Letting Go" is a beautiful, difficult true story of death. You know from the very first sentence — "Sara Thomas Monopoli was pregnant with her first child when her doctors learned that she was going to die" — that it is going to be tragic. This story has long been one of my favorite pieces of health care journalism because it grapples so starkly with the difficult realities of end-of-life care.

In the story, Monopoli is diagnosed with stage four lung cancer, a surprise for a non-smoking young woman. It's a devastating death sentence: doctors know that lung cancer that advanced is terminal. Gawande knew this too — Monpoli was his patient. But actually discussing this fact with a young patient with a newborn baby seemed impossible.

"Having any sort of discussion where you begin to say, 'look you probably only have a few months to live. How do we make the best of that time without giving up on the options that you have?' That was a conversation I wasn't ready to have," Gawande recounts of the case in a new Frontline documentary .

What's tragic about Monopoli's case was, of course, her death at an early age, in her 30s. But the tragedy that Gawande hones in on — the type of tragedy we talk about much less — is how terribly Monopoli's last days played out.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

At Vox, we believe that clarity is power, and that power shouldn’t only be available to those who can afford to pay. That’s why we keep our work free. Millions rely on Vox’s clear, high-quality journalism to understand the forces shaping today’s world. Support our mission and help keep Vox free for all by making a financial contribution to Vox today.

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In Politics

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Trump’s “moderation” on abortion is a lie

Biden’s newest student loan forgiveness plan, explained

Trump may sound moderate on abortion. The groups setting his agenda definitely aren’t.

The lies that sell fast fashion

The terrifying and awesome power of solar eclipses

When is the next total solar eclipse?

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The purpose of this paper is to explore themes of language death in various respects, with focus on why we should care about languages dying. This paper also answered some questions regarding the ...

Languages: Why we must save dying tongues. Hundreds of our languages are teetering on the brink of extinction, and as Rachel Nuwer discovers, we may lose more than just words if we allow them to ...

1 What is language death? The phrase 'language death' sounds as stark and Wnal as any other in which that word makes its unwelcome appearance. And it has similar implications and resonances. To say that a language is dead is like saying that a person is dead. It could be no other way - for languages have no existence without people.