Essay on the HIV/Aids Health Issue in South Africa

The Human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) is one of the major health challenges affecting public health in South Africa. Despite South Africa’s efforts to avail medications for controlling and reducing viral transmission, HIV/AIDS still poses a significant health challenge to the public. The disease has already devastated thousands of families across the country. Deaths resulting from HIV/AIDS have orphaned millions of children and disrupted the normal structure of the community. HIV/AIDS has affected almost every sector of life. The pandemic has largely contributed to the increase in health expenditures in South Africa. The critical level of care required by the patients is forcing the government to divert resources that would otherwise be used to finance other development projects. Apart from overburdening the overall health and social support expenditures in the country, the virus is claiming the lives of hundreds of health practitioners in South Africa. The HIV/AIDS pandemic in South Africa is a complicated public health issue that requires a strategic approach from the national governmental organizations, non-governmental organizations, and international organizations.

Historical Context of HIV/AIDS in South Africa

South Africa reported its first HIV case in 1982, a time when the country was fighting to end the apartheid system (Hodes, 2018). The government ignored the HIV/AIDS problem as the country was facing other serious challenges such as political unrest. The media outlets did not react to the pandemic immediately (Hodes, 2018). Politics dominated major headlines at the time and the public was not immediately made aware of the pandemic. HIV silently began to take hold mostly among the gay population of South Africa and the black population.

Three years after the first case was reported, the department of health initiated a public awareness campaign. The campaign included the use of coffins and skeletons to convey messages about HIV/AIDS in the country (Hodes, 2018). The campaign however did not convey messages on the mode of transmission. In 1987, the apartheid government sought to restrict the civil liberties of infected persons (Hodes, 2018). South Africans diagnosed with HIV were quarantined while immigrants who had the disease or were suspected to have been infected were deported back to their countries.

By 1990, HIV/AIDS prevalence in South Africa had reached an all-time high. The country was at this time transitioning from apartheid to democracy and the government was facing a myriad of challenges which included corruption and abuse of power (Hodes, 2018). There was no elaborate plan by the government to handle the HIV/AIDS issue. The department of health was unable to take the appropriate measures to curb the spread of the disease. Infected people could not access the life-saving antiretroviral treatment (Hodes, 2018). These factors led to the rise of public health activist movements in the country. Members of these movements sought to compel the government to enable public access to testing and treatment of the virus. The movements further sought to force the government to undertake the necessary steps to curb the spread of the virus.

The efforts of the activists saw the formation of The National Aids Convention of South Africa (NACOSA) in 1991 (Geffen and Welte, 2018). This organization sought to strengthen partnerships among civil groups, health workers, and development agencies in a bid to curb the spread of HIV on the. In 1993, the South Africa government published its first plan to intervene HIV/AIDS pandemic issue (Hodes, 2018). Despite all these activities, the response to the pandemic remained inadequate and ineffective. Cultural challenges impeded the government’s efforts in addressing the HIV/AIDS issue. For instance, it was a taboo among some South African communities to talk openly about sex.

Current Developments of HIV/AIDS Pandemic Issue

Currently, South Africa has the highest HIV prevalence rate in the world. Out of the 58 million people in the country, 7.7 million are estimated to have contracted the virus (Avert, 2020). In the Southern Africa region, South Africa alone accounts for 30% of all new HIV infections. Of the 240,000 new infections in 2018, 71,000 were from South Arica (Avert, 2020). The burden of the pandemic has profound implications on the development of South Africa. The high rates of HIV-related infections and deaths have compromised household stability and investments in children.

The government of South Africa has made commendable efforts to address the HIV/AIDS issue. Steps undertaken by the government include enhanced clinical testing and financing the anti-retroviral program (ART) (Avert, 2020). Today, South Africa has the largest antiretroviral treatment in the world (Avert, 2020). This program is largely financed from domestic resources. As a result of the ART program, the national life expectancy in the country has increased from 56 to 63 years.

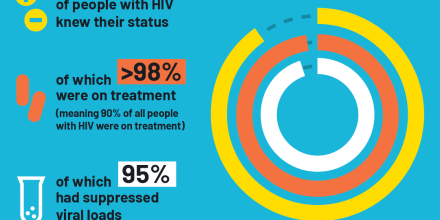

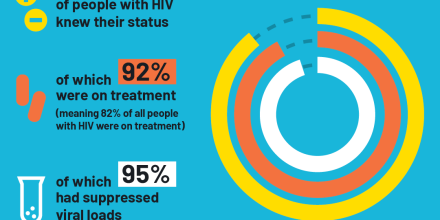

There has been notable progress in the testing and suppression of the virus. A report by the world health organization indicates that 90% of the people living with HIV have so far been tested and 87% of them have enrolled in the treatment program (Avert, 2020). The prevalence, however, remains high especially in the Western Cape and in KwaZulu-Natal areas.

HIV/AIDS Health and Social Policies in South Africa and a Comparative Analysis with the United States

Access to Testing

The government of South Africa has launched a number of HIV testing and care programs. The two recent nationwide testing initiatives are the National HIV testing and the National HIV/AIDS counseling campaign (Avert, 2020). These initiatives were part of the government’s policy to have people working in the private sector and the higher education sector get tested for the virus. As a result of this policy, more than 10 million people have since been tested (Avert, 2020). There have however been discrepancies in the number of women when compared to that of men who present themselves for testing. More women are tested as compared to men. Men are reportedly worried about queuing outside the testing facilities.

Access to HIV testing is a priority in many other countries. In the United States, for instance, the government has undertaken measures to include annual HIV testing for people aged between 15-65 years (Avert, 2019). Such measures include the expansion of the national health insurance program. The rate of people who turn in for HIV testing in the United States of America is however low as compared to that of South Africa. In the United States, people have a low disease risk perception while others are afraid of being stigmatized after diagnosis.

Access to Care and Treatment

The United Nations program introduced the 90-90-90 targets to mitigate the adverse effects of HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS, 2017). In line with the UN’s program, South Africa guarantees free and reliable access to anti-retroviral treatment (ART) (Avert, 2020). At least 4.8 million people in the country are receiving HIV/AIDS treatment as a result of the free access to care and treatment policy (Masquillier et al., 2020). Studies reveal that more women than men are more likely to enroll for ART in South Africa and as a result, the mortality rate of men is twice that of women.

Just like in South Africa, there is free access to care and treatment policy for the people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States (Avert, 2020). Testing for HIV/AIDS in the United States has become widespread over time. However, more than half of the adult population are were yet to turn out for testing as at 2012 (Rizza et al., 2012). The number of people who turn in for these services in the United States is, however, lower when compared with that of South Africa. This can be attributed to lack of awareness and misconceptions related to the HIV/AIDS virus in the United States.

Education and Awareness

The government of South Africa has made numerous efforts to educate the masses and create awareness of the HIV/AIDS pandemic (Avert 2020). The government is determined to use the education policy to provide comprehensive sexuality education in both public and private schools. By the end of the year 2016, only 5% of the schools were offering sexuality education in South Africa (Avert 2020). The government is planning to introduce a system of education that will assist learners to prevent and report incidents of sexual violence.

In the United States, the status of sexual health education is insufficient in most areas. There are claims that sexual education is not taken seriously and in some cases, it does not start early enough for the learners. The number of schools where students are supposed to get advice on HIV prevention keeps decreasing in the United States. Offering HIV/AIDS education and creating awareness has not been taken seriously in the United States. According to the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (2016), many Americans have become complacent about HIV/AIDS and at least a quarter of the patients are not aware of their statuses.

Legislation

Through legislation, the government of South Africa has managed to minimize cases of discrimination on an HIV status basis. Section 6(1) of the constitution requires the public especially those at the workplace to desist from any form of unfair discrimination based on a person’s HIV status (Mubangizi, 2009). The constitution bars employees from dismissing employees who turn out to be HIV positive. These laws aim to promote a non-discriminatory work environment and curb the stigmatization of HIV patients.

HIV/AIDS Pandemic issue in the Context of Social Divisions in South Africa

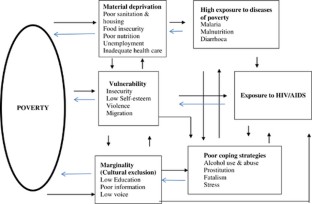

Apart from HIV/AIDS being a medical problem in South Africa, it is a social problem. This is demonstrated by the virus’s widespread, ineffectiveness and the inability of the medical department to control HIV expansion in the country. South Africa is one of the world’s countries that have experienced gross social inequalities (Gordon, Booysen and Mbonigaba, 2020). Such inequalities are mostly based on racial, class, and gender factors. Apartheid for instance has for a long time shaped the social profile and as a result, derailed the efforts to deal with the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

Social divisions and issues related to it have been the major setback in the fight against the virus. Whereas anyone regardless of their social status can get infected with HIV/AIDS, certain groups of people are at a higher risk of getting the infection (Avert, 2020). These groups of people engage in high-risk behaviors while others experience stigma and discrimination. Stigma and discrimination are among the major hindrances for people to seek HIV testing and treatment. If the social issues are well understood and dealt with, the government and international organizations could effectively roll out prevention programs to the people at high risks.

Women in South African society have an unequal cultural, social, and economic status. This is largely a result of inequitable laws and harmful cultural practices that empower men and disempower women. Women are at a higher risk of contracting the virus as compared to men. By 2017, the percentage of women infected stood at 26% while that of men stood at 15% (Avert, 2020). Gender-based violence, poverty, and the low status of women in South Africa are largely to blame for the high disease prevalence among women. A third of women in the country have at one time experienced intimate partner violence.

A report by the world health organization indicated that the HIV prevalence among young women was much higher than that of young men in the year 2018. Intergeneration relationships between older men and young women were understood to be the major force behind this disparity. Discriminative social attitude towards women makes it harder for them to access testing and treatment services.

South Africa is among the countries with the highest unequal distribution of resources (Gordon, Booysen and Mbonigaba, 2020). The HIV/AIDS epidemic in the country has brought about huge demands for medical care in the public health sector. As a result, the disease is more prevalent among the middle class and lower class population.

Preventing early deaths arising from HIV-related infections requires a household member to first identify the infection through testing, and enroll in the treatment program. Though testing is free in South Africa, there are other related expenses such as transport fees. People of the lower class may have problems in financing such expenses. People of the lower social class report lower rates of HIV testing as compared to those of high social class.

Being of a lower social class in South Africa is associated with reduced or no food security, lack of food diversity, and increased chances of skipping meals. Poor women are forced to adopt behaviors that increase their risk of getting infected. These behaviors include commercial sex and early marriages. HIV patients require a balanced diet to boost their immune response to opportunistic infections. In addition, Low-class people may have difficulties accessing protection equipment such as condoms due to their reduced financial capability.

Globally, racial inequalities play a significant role in escalating the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Some ethnic groups are at a higher risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV when compared to other ethnic groups. This is because, in some places such as South Africa, some population groups have higher rates of HIV/AIDS prevalence. The risk of acquiring the infection in these groups is high.

In South Africa, Black African males have high HIV/AIDS prevalence as compared to their counterparts from other races (Avert, 2020). The high prevalence among blacks is created by historical social injustices and unequal social and economic status. The apartheid particularly has contributed significantly to the HIV prevalence among the black community in South Africa (Hodes, 2018). In a country where blacks are the majority, apartheid perpetuated HIV through denial of health services and access to quality education to the black community. Apartheid policies mostly addressed the social and economic advances for the minority white communities at the expense of the black race. Up to date, the black community is yet to recover from the burden of high HIV prevalence which would otherwise not be there had it not for the apartheid system.

Cultural Issues

The high prevalence of HIV/AIDS in South Africa has prompted speculations regarding risk factors that may be unique to the country. Some cultural practices increase the risk of HIV/AIDS in the region. These factors include polygamy, early marriages, and virginity testing. All these vices characterize most South African societies.

Polygamy is not primarily a harmful practice that can directly lead to the spreading of HIV/AIDS. However, how people in polygamous marriages conduct themselves ends up facilitating the spread of the virus. Wives in a polygamous marriage have little or no control over the sexual behaviors of their husbands or co-wives. Infidelity for instance could be a catalyst for the spread if the cheating partner gets infected. In the KwaZulu-Natal community of South Africa, there has been a resurgence of virginity testing (Ngubane, 2020). The public identification of a young girl as a virgin increases her risk of sexual abuse.

Age and Family Status

By 2018, the number of HIV-infected children in South Africa stood at 260,000 and 63% of them were on treatment. These were children of age 0-14 (Avert, 2020). The rate of infection among young children is lower as compared to that of people aged 15 years and above. The decline in new infections among children is attributed to the government’s efforts in preventing mother-to-child HIV transmission. Children are however mostly affected by the HIV pandemic through the loss of their parents and guardians. HIV/AIDS pandemic has orphaned At least 1.2 million children in South Africa (Avert, 2020). This creates another problem as these children lose their providers. They become insecure and vulnerable to HIV due to economic and social insecurities. Such children become targets of sexual predators who force them to have sex in exchange for support.

The Role of International Organizations and Aid Agencies in Addressing the HIV/AIDS Issue

There are many international organizations involved in the fight against the spread of the HIV/AIDS pandemic. These organizations engage in a coordinated effort to stop new HIV infections and ensure that everyone living with the virus has unrestricted access to testing and quality treatment. International Organizations such as the Joint United Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) are responsible for promoting human rights for the patients and producing data for decision making. Some of the prominent international organizations involved in this fight include The Global Fund, The World Health Organization (WHO), and UNAIDS. These organizations undertake the international role of policy formulation and legislation in matters concerning the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

Formulation of Policies

One of the policies adopted by international organizations is the creation of awareness about HIV/AIDS. Kaiser Family Foundation for instance focuses on the provision of the latest data and information about the virus (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2016). The organization conducts research and data analysis on regular basis. In addition, Kaiser Family Foundation works with major news organizations across the world to enable easy access to information. Its information is provided free of charge.

International health organizations aim to build a better and healthier future for people living with HIV/AIDS across the world. These organizations advocate for equality and preservation of human rights regardless of their health status. The World Health Organization particularly provides evidence-based technical support to countries across the world. The organization supports its members in the quest to scale up the treatment of the virus and slow down its spread. The mission of such organizations is to lead collective action on the global HIV response.

The United Nations General Assembly fully recognizes human rights and freedoms. The organization has formulated a number of international regulations and guidelines meant to protect HIV patients across the world. Following a global outcry against the high cost of HIV treatment, the ministerial council in 2001 made a regulation prompting its members to take measures to protect public health (Patterson and London, 2002). The United Nations members were required to allow easier access to medications for people living with the virus.

International organizations have made numerous efforts to form and support national organizations. These national organizations comprise professionals and HIV/AIDS victims who are united in advocating for the rights of patients. With the support of the United Nations Development Programme, many countries have been able to form law associations meant to oversee the implementation of the rights of patients. Organizations such as legal clinics promote laws and policies on human rights and freedom.

Global Issues in the Fight against HIV/AIDS

The global economic crisis is a major hindrance to the international fight against HIV/AIDS. The UNAIDS faces a greater challenge in ensuring that UN agencies heed their call of supporting developing countries that are severely affected by the pandemic. Financing a sustainable response to the disease is a hard task especially for developing nations. With the emergence of other pandemics that require huge financing, international organizations face a challenge in financing the HIV/AIDS control measures.

The emergence of other infections has derailed the international fight against HIV/AIDS. Currently, the world is battling a new virus. The COVID-19 pandemic has a serious impact on the most vulnerable communities and impedes the progress of the fight against HIV/AIDS. World resources are now redirected to the new virus. At the moment, there is no single country that is immune to the increasing economic cost of the new pandemic.

The HIV/AIDS pandemic poses a significant health threat to South Africa. The complex nature of the disease makes it even harder for the government and other international organizations to develop a comprehensive approach to addressing it. The government and other organizations, however, have made numerous efforts to intensify testing, treatment, and provision of care to HIV patients. All these efforts have been derailed by other social factors such as class differences, gender inequalities, ethnicity, and cultural issues. In its efforts to slow the spread of the disease and mitigate its adverse effects, the government has enacted a number of policies. The policies include free access to HIV testing, education, and the creation of public awareness. International organizations have made numerous efforts to help South Africa and other developing nations in fighting the virus. These include financing the war against the disease and developing policies meant to address the HIV/AIDS issue.

Avert. 2019. HIV and AIDS in the United States of America (USA). [Online] Available at: <https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/western-central-europe-north-america/usa> [Accessed 17 April 2021].

Avert. 2020. HIV and AIDS in South Africa. [Online] Available at: <https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/sub-saharan-africa/south-africa> [Accessed 17 April 2021].

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016. Challenges in HIV Prevention . [Online] Available at: <https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/challenges-508.pdf> [Accessed 6 May 2021].

UNAIDS. 2017. Ending Aids; Progress towards the 90-90-90 targets. [Online] Available at: <https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/Global_AIDS_update_2017_en.pdf> [Accessed 17 April 2021].

Geffen, N. and Welte, A., 2018. Modeling the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic: A review of the substance and role of models in South Africa. Southern African Journal of HIV Medicine , 19(1).

Gordon, T., Booysen, F. and Mbonigaba, J., 2020. Socio-economic inequalities in the multiple dimensions of access to healthcare: the case of South Africa. BMC Public Health, 20(1).

Hodes, R, 2018. ‘HIV/AIDS in South Africa’, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History .

Kaiser Family Foundation. 2016. HIV Awareness and Testing. [Online] Available at: <https://www.kff.org/slideshow/hiv-awareness-and-testing/> [Accessed 17 April 2021

Masquillier, C., Knight, L., Campbell, L., Sematlane, N., Delport, A., Dube, T., and Wouters, E., 2020. Sinako, a study on HIV competent households in South Africa: a cluster-randomized controlled trial protocol. Trials, 21(1).

Mubangizi, J., 2009. HIV/AIDS and the South African Bill of Rights, with specific reference to the approach and role of the courts. African Journal of AIDS Research , 3(2), pp.113-119.

Ngubane, L., 2020. Traditional Practices and Human Rights: An Insight on a Traditional Practice in Inchanga Village of Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. The Oriental Anthropologist: A Bi-annual International Journal of the Science of Man , 20(2), pp.315-331.

Patterson, D. and London, L., 2002. International law, human rights, and HIV/AIDS. [Online] Global Public Health and International Law. Available at: <https://www.who.int/bulletin/archives/80(12)964.pdf> [Accessed 17 April 2021].

Rizza, S., MacGowan, R., Purcell, D., Branson, B. and Temesgen, Z., 2012. HIV Screening in the Health Care Setting: Status, Barriers, and Potential Solutions. Mayo Clinic Proceedings , 87(9), pp.915-924.

Cite this page

Similar essay samples.

- Essay on the Sisters, Araby, and an Encounter

- Essay on Universalism

- Essay on Compare and Contrast Antigen Receptors With Pattern Recogniti...

- Collective Bargaining Gives Employees a Voice

- Essay on the Collapse of Communism and the Dissection of Bicycle Thiev...

- Essay on Performance Appraisal

Programs submenu

Regions submenu, topics submenu, strengthening australia-u.s. defence industrial cooperation: keynote panel, cancelled: strategic landpower dialogue: a conversation with general christopher cavoli, china’s tech sector: economic champions, regulatory targets.

- Abshire-Inamori Leadership Academy

- Aerospace Security Project

- Africa Program

- Americas Program

- Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy

- Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

- Asia Program

- Australia Chair

- Brzezinski Chair in Global Security and Geostrategy

- Brzezinski Institute on Geostrategy

- Chair in U.S.-India Policy Studies

- China Power Project

- Chinese Business and Economics

- Defending Democratic Institutions

- Defense-Industrial Initiatives Group

- Defense 360

- Defense Budget Analysis

- Diversity and Leadership in International Affairs Project

- Economics Program

- Emeritus Chair in Strategy

- Energy Security and Climate Change Program

- Europe, Russia, and Eurasia Program

- Freeman Chair in China Studies

- Futures Lab

- Geoeconomic Council of Advisers

- Global Food and Water Security Program

- Global Health Policy Center

- Hess Center for New Frontiers

- Human Rights Initiative

- Humanitarian Agenda

- Intelligence, National Security, and Technology Program

- International Security Program

- Japan Chair

- Kissinger Chair

- Korea Chair

- Langone Chair in American Leadership

- Middle East Program

- Missile Defense Project

- Project on Fragility and Mobility

- Project on Nuclear Issues

- Project on Prosperity and Development

- Project on Trade and Technology

- Renewing American Innovation Project

- Scholl Chair in International Business

- Smart Women, Smart Power

- Southeast Asia Program

- Stephenson Ocean Security Project

- Strategic Technologies Program

- Transnational Threats Project

- Wadhwani Center for AI and Advanced Technologies

- All Regions

- Australia, New Zealand & Pacific

- Middle East

- Russia and Eurasia

- American Innovation

- Civic Education

- Climate Change

- Cybersecurity

- Defense Budget and Acquisition

- Defense and Security

- Energy and Sustainability

- Food Security

- Gender and International Security

- Geopolitics

- Global Health

- Human Rights

- Humanitarian Assistance

- Intelligence

- International Development

- Maritime Issues and Oceans

- Missile Defense

- Nuclear Issues

- Transnational Threats

- Water Security

The World’s Largest HIV Epidemic in Crisis: HIV in South Africa

Photo: STEPHANE DE SAKUTIN/AFP/Getty Images

Commentary by Sara M. Allinder and Janet Fleischman

Published April 2, 2019

In some communities of KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa, 60 percent of women have HIV. Nearly 4,500 South Africans are newly infected every week; one-third are adolescent girls/young women (AGYW) ages 15-24. These are staggering figures, by any stretch of the imagination. Yet, the HIV epidemic is not being treated like a crisis. In February, we traveled to South Africa, to understand what is happening in these areas with “hyper-endemic” HIV epidemics, where prevalence rates exceed 15 percent among adults. We were alarmed by the complacency toward the rate of new infections at all levels and the absence of an emergency response, especially for young people.

This is no time for business as usual from South Africa or its partners, including the U.S. government through the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). The epidemic is exacerbated by its concentration in 15-49-year-olds, those of reproductive and working age who are the backbone of South Africa. Without aggressive action to reduce the rate of new infections in young people, HIV will continue to take a tremendous toll on the country for years and generations to come. Collective action is needed to push beyond the complacency and internal barriers to implement policies and interventions that directly target HIV prevention and treatment for young people. PEPFAR should ensure its programs support those efforts.

South Africa remains the epicenter of the HIV pandemic as the largest AIDS epidemic in the world—20 percent of all people living with HIV are in South Africa, and 20 percent of new HIV infections occur there too. The country also faces a high burden of tuberculosis (TB), including multi-drug resistant TB, which amplifies its HIV epidemic. Of particular concern are South Africa’s hyper-epidemics , many in KwaZulu-Natal and Mpumalanga provinces, and the concentration in specific populations like AGYW. Of the estimated 7.2 million South Africans living with HIV, nearly 60 percent are women over the age of 15. HIV prevalence in other key populations—female sex workers, men who have sex with men, transgender women, and people who inject drugs—remains unacceptably high, in some cases double the national prevalence rate of approximately 19 percent .

After the early years of denial, the South African government now finances close to 80 percent of the HIV response, an unparalleled commitment in sub-Saharan Africa, and provides more than 4 million people with life-prolonging anti-retroviral treatment (ART). In 2018, President Cyril Ramaphosa called for an increase of 2 million South Africans on ART by December 2020 through increased testing and treatment.

The problem facing South Africa’s HIV response is that treatment scale-up has stalled, and while new infections have gone down by 42 percent, the rate is not fast enough to bend the curve of the epidemic. New infections in young men and women remain alarmingly high (nearly 87 percent of the total) and viral suppression rates, a key to preventing those living with the virus from passing it on, are under 50 percent for those 15-24 years old. With approximately 45 percent of the population under the age of 25 , the sheer numbers of those becoming infected and overall prevalence of HIV will stay alarmingly high without a massive decline in the new HIV infection rate.

The central question is how to interrupt HIV transmission in young adults, and where and whom to target. One answer is to target AGYW who are at higher risk for HIV acquisition in South Africa, as they are elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa. The reasons are both biological and social, including high rates of teenage pregnancy, an epidemic of gender-based and interpersonal violence; lack of quality education; and widespread poverty and unemployment. High rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) increase the risk of HIV acquisition, and mental health issues can lead to risky behaviors. Professor Olive Shisana, special adviser on social policy to President Cyril Ramaphosa, emphasized the urgency: “New infections are the highest in adolescent girls/young women. We need to close the tap. If we get to them early, we’ll reduce the load on the nation and globally.”

Addressing the range of social, economic, and health issues that put AGYW at risk is one approach. PEPFAR’s DREAMS program—Determined, Resilient, Empowered, Aids-Free, Mentored, and Safe—includes a package of multisectoral interventions to be “layered” for a comprehensive benefit to the young woman. The importance of this layered approach led to DREAMS being adapted by the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria and the South African government in its She Conquers campaign. However, tracking the layering of those services has proven to be a challenge, as has widespread scale up.

Another important approach is to reach young men. The Centre for the Aids Programme of Research in South Africa (Caprisa) has demonstrated that a particularly complicated cycle of transmission involves men ages 25-34 infecting adolescent girls/young women ages 15-24, who then go on to infect their longer-term male partners ages 24-35, and the cycle continues. Prevalence among 20-24-year-old women is three times higher than in men their age. Promoting prevention through behavior and voluntary medical male circumcision (VMMC) and getting those men who are already living with HIV on treatment and virally suppressed so they can’t pass the virus to their partners are critical interventions.

The challenge is reaching the men. “Services are not geared for men and young people,” acknowledged Dr. Yogan Pillay, the deputy director general for the National Department of Health. While adult women come to clinics when they are pregnant or for their children, young men rarely interact with the health system unless they have suffered a major injury. In general, men are less likely to know their HIV status than women or to seek care and treatment if they test positive. Health services seen as not “male friendly” and gender norms around masculinity that equate seeking health care with weakness are two factors. As a result, men 25-34 years old have the lowest viral suppression rates (41.5 percent) of any gender/age band in South Africa. Community outreach is one way to reach AGYW and their male partners, especially those out-of-school who have a substantially higher HIV risk and men older than 25 years, by bringing information and services to where they are. “If you think you can intervene by using the current approach to health delivery, it won’t work,” noted professor Quarraisha Abdool Karim, Caprisa associate scientific director.

For many young adults, HIV is often not seen as a crisis because they have bigger worries: extreme poverty, unemployment and lack of jobs, crumbling school infrastructure. When they live in a community with such high HIV rates, there is a fatalistic feeling that getting infected with HIV is inevitable. Girls and women also face an epidemic of rape and gender-based violence; many young women express more concerns about getting raped or getting pregnant than getting HIV. At one site we visited, the girls stated that getting raped was their number one fear.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) offers a tool to help break the transmission cycle. Oral PrEP taken once a day can reduce vulnerability to infection by 99 percent. In areas where there is so much HIV circulating, every sexual encounter is high risk, and widespread PrEP could be a prevention lynchpin. However, PrEP rollout has been slow and inadequate in South Africa since it was approved in national guidelines in 2016. There have been issues with messaging, health worker sensitization and training, and availability. PrEP scale-up will require extensive outreach to create demand, ensure adherence, and negate any stigma to ensure that all those at high risk can have access. Only an estimated 12,000 people are currently on PrEP at approximately 50 clinics nationwide—shy of the national target of more than 18,000. To put that in further perspective, 12,000 equates to only 5 percent of the 231,000 presumed to be at risk for new infections based on the 2017 rates.

Lack of knowledge can impact young adults’ informed prevention and treatment choices. There has been an associated decline in HIV and treatment literacy, which means that young people often don’t understand how the virus affects the body and the impact of lifelong ART. The most recent national survey data from 2017 shows the same low level of condom use among 15-24-year-olds as the last survey in 2012, an increase in sexual debut before the age of 15 for boys, and an increase in multiple sexual partnerships for women under 24.

One barrier is the provision of basic health education and service delivery in schools. While South Africa has a national policy on school-based health education, some provincial officials, school governing boards, and other gatekeepers often prevent services from being provided, even though the age of consent for health services is 12. Schools are an important entry point because there is a high rate of school retention in South Africa and, once out of school, it is difficult to reach young people.

While we met many dedicated HIV champions across South Africa, and there are commitments from national and provincial officials and existing national strategies, the health and education systems are not providing the necessary information and services for young people, and not enough investment is being made to empower communities and civil society organizations to launch more effective and sustainable responses. There is an absence of targeted outreach, media campaigns, and high-profile champions. Young South Africans told us repeatedly that they wanted more leadership and information on HIV and to see role models of healthy living that make HIV prevention and staying negative cool and demonstrate how to live positively with HIV.

The critical gap in South Africa is not between evidence and policy, but between policy and implementation. While the government is committed to supporting the national HIV treatment program and has issued enabling guidelines, it faces significant challenges to effective implementation. It lacks the resources for an overhaul of the public health infrastructure and to scale up and increase coverage of prevention programs like PrEP and broader programs to address the needs of young adults. In addition, health worker shortages and a rising non-communicable disease (NCD) burden are crippling already overstretched health facilities, and the decentralized health system requires political will at the provincial and district levels to implement services effectively.

Many politicians and local government officials are preoccupied with other issues, such as the economic crisis that has gripped the country in recent years, a legacy of corruption that has crippled the energy sector, and upcoming elections in May. The president’s 2019 State of the Nation address called attention to corruption and gender-based violence, but in stark contrast to last year’s treatment pledge, he did not once mention HIV.

South Africa’s HIV epidemic needs to be treated as a public health emergency. After the elections in May, there is an opportunity for the government to re-commit to fighting HIV, at national, provincial, and district levels. Business as usual is not bringing down new infections or getting patients onto treatment. The government should go beyond strategies and push through barriers to actual implementation, get services into school, and re-educate South Africans about HIV. Enabling nationwide scale-up of PrEP for young adults and all who are at high risk would go along way toward protecting South Africa’s future.

For South Africa’s HIV partners, like PEPFAR, the post-election period also provides an opportunity to re-engage with the new government and focus on how to best support targeted interventions toward adolescents and young people. That includes listening to young people and communities, making sure services are available away from clinics in communities and schools, supporting provinces in service provision, and elevating prevention and treatment for young people. Turning the tide on the epidemic will require more than increasing the number of people on treatment; PEPFAR can provide unique support to South Africa to implement a multipronged strategy for young people as an urgent priority.

Sara M. Allinder is executive director and senior fellow and Janet Fleischman is senior associate with the Global Health Policy Center at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C. This commentary is based on their visit to South Africa in February 2019.

Commentary is produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(s).

© 2019 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. All rights reserved.

Sara M. Allinder

Janet Fleischman

Programs & projects.

- Health Security

- Understanding The HIV Epidemic

At a glance: HIV in South Africa

The biggest HIV epidemic in the world

Key statistics: 2021

- 7.5 million people with HIV

- 18.3% adult HIV prevalence

- 210,000 new HIV infections

- 51,000 AIDS-related deaths

- 5.5 million people on antiretroviral treatment

Progress towards targets

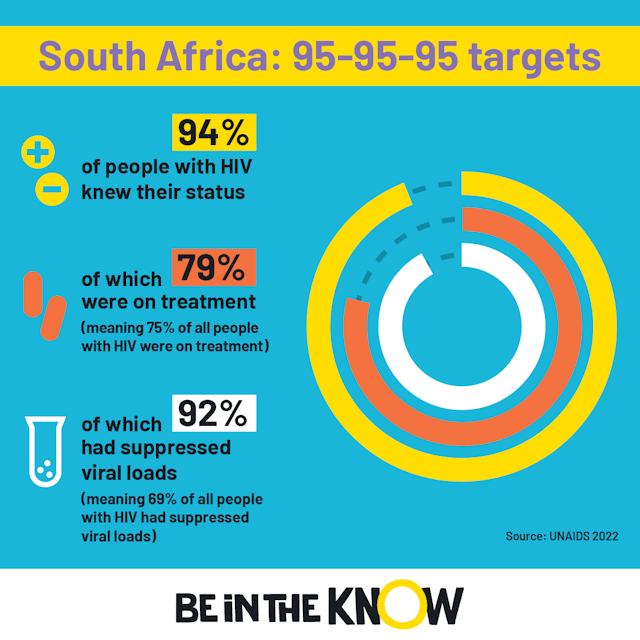

The current targets for HIV testing and treatment are called the 95-95-95 targets and must be reached by 2025 in order to end AIDS by 2030.

In 2021 in South Africa:

Did you know?

South Africa has made huge improvements in getting people to test for HIV in recent years and met the 2020 target of 90% of people with HIV knowing their status in 2018. But it is behind on increasing access to HIV treatment, hampered by the need to provide HIV treatment for more people than any other country in the world.

Preventing HIV in South Africa focuses on:

- prevention of mother-to-child transmission

- distributing condoms, including male and female condoms

- voluntary medical male circumcision

- PrEP – a daily pill that can prevent HIV (vaginal ring and injectable being trialled)

- management of sexually transmitted infections, including partner infections

- linking closely to HIV testing services.

South Africa was the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to fully approve PrEP, which is now being made available to people at high risk of infection, such as sex workers. The country has remained focused on increasing PrEP access in recent years by introducing things such as mobile PrEP clinics, despite the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Testing for HIV is lower among:

- people with a lower socio-economic background

- people living in rural areas.

It is possible to self-test for HIV at home in South Africa, which is popular among young people and people from key affected populations.

Treatment for HIV is:

- started as soon as someone tests positive

- usually a three-in-one tablet

- received by more people with HIV than any other country in the world.

The South African government changed the usual first-line treatment regimen it offers in 2017, to a Dolutegravir-containing fixed dose combination, which has been found to have fewer side effects.

Local context

Women continue to bear a disproportionate burden of the HIV epidemic, with women twice as likely to have HIV than men . Around one-third of women are likely to experience intimate partner violence in South Africa – and this has increased in recent years, linked to the fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic. Violence against women and girls is a huge issue, and can prevent women from testing for HIV and starting and staying on treatment. It also helps drive transmission.

Men in South Africa are less likely than women to use HIV services, including HIV testing and starting and staying on antiretroviral treatment.

It is estimated that around 58% of sex workers have HIV. Female sex workers with HIV are consistently less likely to know their HIV status than other adult women.

Gay men and other men who have sex with men with HIV are much less likely to know their HIV status compared with other men. However, when they do know their HIV status, they are more likely to receive HIV treatment and be virally suppressed.

HIV-related stigma remains an issue – around 17% of people hold discriminatory attitudes towards people with HIV, according to UNAIDS data. But this is lower compared to other countries in the region.

Get the latest news

Keep up-to-date with new developments, research breakthroughs and evidence for what works in sexual health and the HIV response, with our news service.

Explore more

At a glance: HIV in Kenya

At a glance: HIV in Lesotho

At a glance: HIV in Malawi

At a glance: HIV in Nigeria

At a glance: HIV in Uganda

Still can't find what you're looking for, share this page.

- Last updated: 31 March 2023

- Last full review: 01 March 2025

- Next full review: 01 March 2025

HIV and AIDS Prevalence in South Africa Essay

Introduction, podcast overview, information learned.

Countries of the African continent continue to be disproportionately burdened by HIV/AIDS. South Africa has the highest HIV prevalence rates in the world, both among adults and children. In the Africa Science Focus podcast episode, the host and guests, including UNAIDS representatives, discuss the causes of South Africa’s HIV burden (Africa Science Focus, 2022). The podcast was selected as it addresses a disease that remains a critical health and social problem worldwide.

The podcast focuses primarily on the discussion of inequalities in access to treatment and preventative measures in high-risk South African society. According to Africa Science Focus (2022), despite effective HIV/AIDS treatments available around the world, there is a distinct inequality in the ability of South Africa to access them. This disparity is attributed to supply chain complexities, health system shortcomings, poverty, and lingering prejudices (Africa Science Focus, 2022). Although the country made great strides in reducing new infections and the mortality rate, the 90-90-90 UNAID targets of decreasing HIV incidence in the country by 2020 have not been met (Johnson et al., 2020). Overall, many people in South Africa are unaware of their HIV status, have no access to treatment, or are vulnerable to infection due to life circumstances.

The podcast under consideration shed light on some new information concerning approaches to addressing HIV/AIDS and preventing the spread of the disease. According to Africa Science Focus (2022), vulnerable populations should be reached through community work rather than medical facilities. HIV-positive people in South Africa experience concurrent mental health problems, stigma, and breakdown of relationships. Before listening to the podcast, I knew that HIV/AIDS is a significant health problem in South Africa. However, I did not realize how it can be attributed to inequality in the global arena. The condition is on the World Health Organization (WHO) agenda, with the organization working closely with UNAIDS (World Health Organization, 2022). Thus, many community and health organizations are working on reducing HIV incidence in the country.

In summary, HIV/AIDS presents a substantial health problem for South Africa. The Africa Science Focus podcast notes that as the country with the highest HIV prevalence in the world, South Africa does not have the same access to effective HIV treatments as developed countries. Furthermore, the podcast suggests that failure to prevent new infections and reduce transmission can be attributed to the inequality between developing and developed countries.

Africa Science Focus. (2022). Inequality still hampers Africa’s HIV fightback . Sub-Saharan Africa. Web.

Johnson, L. F., Patrick, M., Stephen, C., Patten, G., Dorrington, R. E., Maskew, M., Jamieson, L., & Davies, M.-A. (2020). Steep declines in pediatric aids mortality in South Africa, despite poor progress toward pediatric diagnosis and treatment targets . Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal , 39 (9), 843–848. Web.

World Health Organization. (2022). HIV . World Health Organization. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, January 31). HIV and AIDS Prevalence in South Africa. https://ivypanda.com/essays/hiv-and-aids-prevalence-in-south-africa/

"HIV and AIDS Prevalence in South Africa." IvyPanda , 31 Jan. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/hiv-and-aids-prevalence-in-south-africa/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'HIV and AIDS Prevalence in South Africa'. 31 January.

IvyPanda . 2024. "HIV and AIDS Prevalence in South Africa." January 31, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/hiv-and-aids-prevalence-in-south-africa/.

1. IvyPanda . "HIV and AIDS Prevalence in South Africa." January 31, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/hiv-and-aids-prevalence-in-south-africa/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "HIV and AIDS Prevalence in South Africa." January 31, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/hiv-and-aids-prevalence-in-south-africa/.

- Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome Pathophysiology

- Segregation of HIV-Positive Prisoners

- HIV Prevention Programs in Africa

- HIV/AIDS and International Health Community

- COVID-Related Depression: Lingering Signs of Depression

- Podcasts: Definition and Functions

- HIV-Positive Women's Mental Health Problems

- Deadlocks in Concurrent Computing

- How podcasts differ from radio

- Concurrent Engineering with 3D Printer

- The US and Brazil’s Response to COVID-19

- Epidemiological Study on Salmonella in the Caribbean

- COVID-19 Outbreak and Effectiveness of Vaccines

- The Spread of Monkeypox as a Topic in Healthcare

- The West Africa Ebola Outbreak of 2014-2016

- Society and Politics

- Art and Culture

- Biographies

- Publications

HIV/Aids in South Africa

HIV/Aids is a deadly disease, which is currently not curable. The United Nations AIDS agency (UNAIDS) says the evidence that HIV is the underlying cause of AIDS is ‘irrefutable’. HIV was isolated and identified as the source of what came to be defined as AIDS in 1983/84. HIV destroys blood cells called CD4+ T cells, which are crucial to the normal function of the human immune system. Studies of thousands of people have revealed that most people infected with HIV carry the virus for years before enough damage is done to the immune system for AIDS to develop.

Statistics:

On 21 November 2007, a new UN report said more than three-quarters of Aids-related deaths occurred in sub-Saharan Africa and South Africa was officially the country with the highest prevalence of HIV in the world. The consequences of HIV and AIDS for the economy in the countries in southern Africa are terrible. HIV/Aids is becoming the most devastating disease humankind has ever faced.

In the same UN report on 2007 (UN 2008 Global Report on the HIV and AIDS Epidemic) around 5.7 million South Africans were estimated as having HIV or Aids, including 300 000 children under the age of 15 years. 350 000 people died from AIDS in South Africa in 2007. Women face a greater risk of HIV infection. On average in South Africa there are three women infected with HIV for every two men who are infected. The difference is greatest in the 15-24 age group, where three young women for every one young man are infected.

One of the most significant damages caused by this disease is the number of children orphaned as a result of AIDS. Obtaining accurate statistics on the number of children orphaned is problematic. If orphans are defined as children from birth up to the age of 17 whose mothers have died, UNAIDS estimates that there were 1 400 000 children orphaned due to AIDS living in South Africa at the end of 2007. This figure is higher than for any other country. However, it is estimated that Zimbabwe has 1 000 000 children orphaned due to AIDS among a total population of fewer than 13 million.

How does South Africa celebrate World Aids day? In South Africa, this day was first celebrated in 1996 when the Department of Health organised a special event called the National World AIDS Day in Bloemfontein, Free State, and in Pretoria, Gauteng... read more

Estimates of the numbers of people infected with HIV and dying of AIDS are based on surveys and models. Most people in South Africa do not know their HIV status. Therefore, researchers and statisticians use the prevalence of HIV among groups whose status is known (such as pregnant women attending antenatal classes) to work out the likely prevalence rate in the general population. They also "project" how many people are likely to become infected and die in future, based on what is already known about infection and mortality rates.

Many factors contribute to the spread of HIV. These include: poverty; inequality and social instability; high levels of sexually transmitted infections; the low status of women; sexual violence; high mobility (particularly migrant labour); limited and uneven access to quality medical care; a history of poor leadership in the response to the epidemic and society leaders dying and leaving a generation of children growing up without the care and role models they will normally have. In addition many people in South Africa do not know their HIV status because as a predominantly sexually transmitted disease, its discussion is often taboo. Education, testing, counseling and living positively after being infected play a role in reducing the numbers of infection.

This is a war, it has killed more people than has been the case in all previous wars, we must not continue to be debating, to be arguing, when people are dying and I have no doubt that we have a reasonable and intelligent government, and that if we intensify this debate inside, they will be able to resolve it” - Former South African President, Nelson Mandela, Sunday Times, Sunday 10 Aug 2003

HIV can be transmitted from one person to another through:

Transmission and symptoms:

- Unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse with an infected person

- A mother's infection passing to her child during pregnancy, birth or breastfeeding (called vertical transmission)

- Injections with contaminated needles, which may occur when intravenous drug users share needles, or when health care workers are involved in needle prick accidents

- Use of contaminated surgical instruments, for example during traditional circumcision

- Blood transfusion with infected blood

The only way to know if you are infected is to be tested for HIV infection; you may not have any symptoms for many years.

There are some symptoms that are common warning signs of infection with HIV:

- rapid weight loss

- recurring fever or night sweats

- severe, unexplained fatigue

- swollen glands in the armpits, groin, or neck

- diarrhoea that lasts for more than a week

- white spots or unusual blemishes on the tongue, or in the mouth or throat

- red, brown, pink, or purplish blotches on or under the skin or inside the mouth, nose, or eyelids

- memory loss, depression, and other neurological disorders

However, each of these symptoms can be related to other illnesses so the only way to be sure of HIV infection is to get tested.

Aids Foundation, South Africa [online], available at: www.aids.org.za [accessed 15 April 2009]| History and Science of HIV and Aids [online], available at: www.avert.org [accessed 15 April 2009]|Mandela, N (1998), Keynote Address at a Rally on World AIDS Day. |Mandela, N (2000), Closing Address at the 13th International AIDS Conference .|Bazilli, S., Bond, J., McPhedran, M. and Sherret, L. (2006) Prognosis for the Inequality Virus, Gender, Democracy, Reconstruction & HIV/AIDS in Southern Africa , Concept Paper for the Commonwealth Secretariat, Gender Section, Social Transformation Programmes Division.|Van Wyk, B. (2003). Dark side of the rainbow: the impact of HIV/AIDS on the African renaissance. Centre for the Study of AIDS|Van Wyk, B. (2003). A brief history of a global effort to fund the Campaign against Aids, Centre for the Study of AIDS . Centre for the Study of AIDS.|Van Wyk, B. (2003). The New Drug War. Centre for the Study of AIDS.|Van Wyk, B. (2003). Bringing out the best but mostly the worst in people: addressing HIV/AIDS-related stigma in South Africa.| The SAHARA archive , SAHARA is an alliance of partners established to conduct, support and use social sciences research to prevent the further spread of HIV and mitigate the impact of its devastation in sub-Saharan Africa. The website houses many research papers and publications on HIV/Aids in sub-Saharan Africa| NAM Aids Map , NAM is an award-winning community based HIV information provider. The team at NAM is based in London, in the UK, but their information is known and used across the world. This is a good resource.| TAC, Treatment action Campaign , campaigning for the rights of those living with HIV/Aids in South Africa.|Cameron, E (date unknown) Legal and Human Rights responses to the Hiv/Aids epidemic , prepared for a Court of Appeal exposition.

World Aids Day is internationally observed for the first time The birth of the Treatment Action Campaign

Collections in the Archives

Know something about this topic.

Towards a people's history

The macro-economic impact of HIV/AIDS in South Africa

Journal title, journal issn, volume title, description, collections.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Croat Med J

- v.49(3); 2008 Jun

HIV Infection and AIDS Among Young Women in South Africa

This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Young women in South Africa are at great risk of being infected with HIV. In 2005, HIV infection prevalence in the age group 15-24 years was 16.9% in women and 4.4% in men ( 1 ). The high HIV prevalence in this country is a result of a number of factors which include the following: poverty, violence against women, cultural limitations that promote intergenerational sex, non-condom use and preference for “dry sex,” political factors and challenges that possibly prevented an aggressive response against HIV, recreational drug use, and biological factors such as high prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STI). This essay will present and discuss the prevalence of HIV among young women in South Africa and the reasons for such a high prevalence in the country. I will also give an overview of the intervention programs that are currently under way with an aim to reduce the vulnerability of young women in South Africa. Finally, I will suggest what further interventions need to be provided in order to prevent and control HIV spread in South Africa and other southern African countries.

HIV prevalence among young women in South Africa

HIV prevalence among young women aged 15 years to 24 years in South Africa is estimated at between 15 to 25 percent ( 2 - 4 ). Shisana et al ( 1 ) estimated an estimate of 16.9 percent in 2005. HIV prevalence of about 4 to 6% among young men, although high in comparison with Western countries, is still lower than the prevalence among women ( 3 ). There are also significant racial differences as shown in Table 1 .

Prevalence of HIV infection among South African 2 years or older in 2005*

*Data from Shisana et al ( 1 )

Although there is high HIV prevalence among young women, the distribution is not uniform across the country. Kleinschmidt et al ( 2 ) have reported that lowest levels of infection are found in inland rural areas of the Western Cape and the highest in northwestern parts of KwaZulu Natal, southern Mpumalanga, and eastern Free State. The major metropolitan areas of Johannesburg and Cape Town have intermediate levels of between 7 and 11%.

Attempting to explore the factors that are associated with high HIV prevalence among South African young women is a daunting task, mostly because of the following reasons:

a) Research may examine only a limited scope of factors. For instance, studies designed to explore the role of individual-level determinants of infection (eg, lifetime number of sexual partners, concurrent partners, history of STIs) may not give due recognition to group-level factors, such as percentage of the population living in poverty within a community, racial distribution,, the role of legislation on intimate partner violence, contraceptive use, or availability of health services;

b) limitation in access to communities: much of the studies conducted in South Africa have been conducted in large metropolitan zones or at least in settings which are easily accessible;

c) contradictions arising from studies reporting different effect estimates and different key factors important in the transmission of HIV in a particular setting. For instance, in most of Africa, there is evidence that education level of an individual may be associated with the risk of HIV infection. However, education may be an important factor in one setting but not in another, or the effect of education as an explanatory factor may change over time in the same setting (depending on the stage of the epidemic, a factor such as education may have different associations), or a variable may be measured differently from study to study. For instance, when education is the main variable some studies measure the number of years of schooling completed while other study measure the level of education attained. Certainly, these two measurements may not always measure the same constructs.

d) data on potential confounding variables may not be available from studies conducted in South Africa. It is not always possible to have available data on all aspects of HIV that may potentially affect HIV transmission. For instance, data on injecting drug use in many parts of Africa are lacking. This does not necessarily mean that the practice does not contribute to HIV transmission in these settings. So if injecting illicit drug use and men having sex with men facilitate HIV spread in South Africa, the extent of their contribution to HIV spread is not fully known, as these behaviors are not often studied.

Despite these limitations and potentially many other, there is still a need to explore the “risk factors” of HIV infection and transmission in South Africa, a country which has the largest number of HIV infected persons in the world – an estimated 5 500 000 (95% confidence interval; 4 900 000-6,100,000) ( 5 ).

Biological susceptibility to HIV infection among young women

Pettifor et al ( 4 ) have reported the high efficiency of HIV transmission from men to women in South Africa. They reported that, contrary to previous findings, many HIV infected young women in South Africa had not had significantly more sexual partners than women of similar age in the developed nations. Mean number of lifetime sexual partners was 2.3, but HIV infection prevalence was 21.2%. In many developed countries, infection prevalence estimates are below 1% ( 4 ). Although the results by Pettifor et al may have been affected by under-reporting, there is no reason to believe that South African women would under-report more than the women elsewhere. The finding that many HIV-infected South African young women reported relatively low-risk sexual behaviors is not unusual ( 4 ). A report by Moyo et al ( 6 ) suggests that young people who were in a relationship for at least a year and had sex in the past month were less likely to have used condoms consistently. HIV-infected women in North Carolina ( 7 ) reported that a third of them did not report any known “high risk” behaviors.

The high HIV man to woman transmission rate may be a manifestation of the efficiency of the male “transmitter” and the susceptibility of the woman ( 4 ). Sexually transmitted infections in a male sex partner are important facilitators of HIV transmission ( 8 , 9 ). Furthermore, the immature cervix of the young female is particularly susceptible to the entry of HIV. Other biological factors that have been studied and possibly modulate the susceptibility of young women are the use of hormonal contraceptives, pregnancy, and abnormal vaginal flora ( 10 - 12 ).

South African women may be exposed to HIV infection due to the following reasons: limited treatment opportunities for sexually transmitted infections; young women having sex with young men who are likely to have recent infection; and high pregnancy rates. McPhail et al ( 13 ) surveyed 3618 sexually active young women, 52% of which reported the use of contraceptives in the last 12 months. However, no definitive conclusion has been reached regarding the role of contraception and HIV transmission.

The role of the CCR gene

In the past several years, there has been a growing interest in genetic factors that may help to explain the large differences in HIV prevalence between Africa as opposed to Europe and North America. This resulted in a search for possible genetic differences among races; although race-ethnicity itself is a social and not genetic construct ( 14 ). The CCR5 gene, relatively more common among Caucasians but almost not present among people of African descent, has been suggested to partly be responsible for the differences in HIV prevalence between Africa and Europe and North America ( 15 - 18 ). Iqbal et al ( 19 ) have postulated that the protection from HIV infection in sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya, may be explained by the CCR5 gene. However, the CCR5 gene is not that prevalent even among Caucasians and so its role in the epidemic nature of HIV transmission in southern Africa remains unclear.

Poverty and low status of women

Poverty, both at the individual and the societal level, has been associated with HIV prevalence ( 20 - 23 ). Poor neighborhoods do not have the necessary social infrastructure, which may promote HIV spread. Poor individuals, due to lack of alternatives for earning a livelihood, may be more likely to engage in sex work or other forms of transactional sex. Lopman et al ( 24 ) have reported that HIV prevalence is lower among higher socio-economic classes in that country. As a consequence of Apartheid and the associated racial segregation and discrimination, many South African young women, especially black ones are not educated. Their earning potential within the job market is, therefore, compromised. South Africa has high rates of poverty and unemployment (almost 40% of unemployed).

Transactional sex has been associated with high risk of HIV acquisition in both the developing and developed nations ( 25 ). The most common nationally representative survey of sexual behaviors and HIV infection is the Demographic Health Survey, which is conducted periodically with funding from the United States Agency for International Development of ORC Macro (Maryland) and developing nations’ governments. Survey respondents are simply asked whether men have either provided money or material resources to their non-marital partner. Women are also asked whether they have received money or material gifts from a sexual partner. Any person who reports “yes” to this question is classified as having offered or obtained transactional sex.

Transactional sex has consistently been associated with a high risk of sexually transmitted infections and HIV. While “transactional sex” may be also understood as sex work from the western standpoint, some reports from Africa suggest that exchange of money and material resources may be a different cultural practice ( 26 ). Maganja et al ( 27 ) have reported that in Tanzania, committed sexual partnerships among youth are associated with the expectation that the male will provide material and financial resources to the female partner. The ability of the male partner to provide financial and material resources affects both the duration and the exclusivity of the relationship.

Poulin ( 28 ) has also explored the role of money transfers among youth in a rural southern district of Malawi. This author found that monetary transfers were expected in male-female sexual relationships. Women were described as gauging the marriage potential of a prospective partner by assessing how much money transfers he was able to make. On the other hand, young men perceived such women as ”gold diggers” and not really committed to marriage.

Despite the fact that there are forms of transactional sex that may not carry higher HIV transmission potential, in general though, transactional sex is more likely to be associated with risk behavior. An individual is less likely to insist on “safer sex” when if she or he were to benefit materially or financially from the sexual transaction. Transactional sex is also associated with casual sex and concurrent sexual partnerships, which are then associated with high likelihood of HIV transmission. The power imbalance that may exist between the person providing the money and the person receiving the money facilitates HIV transmission, since partners are not selected on the basis on criteria other than money.

The role of migrant labor

The role that labor migration has played in the spread of HIV in Southern Africa has been discussed elsewhere ( 29 , 30 ). During the Apartheid period, South Africa had been a major recipient of migrant labor from neighboring countries such as Zimbabwe, Botswana, Swaziland, and even from Zambia and Malawi. Some authors have also described the process of “circular migration” where individuals cycle through urban and rural areas in search of jobs in urban areas and living a subsistence livelihood in rural areas. South African authors have ascribed the spread of HIV to and from South Africa to the way migrant labor camps were run. Adult men (laborers) that are employed in the mines are confined to migrant labor camps. Men are not allowed to come to the mines with their spouses, so a vibrant sex industry and an environment that encourages men having sex with men are probably created. This has at least three important implications. First, the men would transmit HIV and other sexually transmitted infections to their sex partners back home during their holidays or upon the return. Second, these men would also bring sexually transmitted infections acquired in their homeland to the migrant labor camps. Finally, disturbed sex ratios may stimulate the relationships with multiple and concurrent partners and transactional sex. Labor migration within South Africa, where mostly men leave their rural areas in search of employment in urban areas is probably a main driver of HIV spread in South Africa ( 31 , 32 ). Migrant labor movement still continues in South Africa, as people work in large farms and in the mines.

Intergenerational sex

Doherty et al ( 33 ) have reported that dissortative sex, ie, sexual partnerships between individuals from high risk and from low risk groups (mixing of risk groups) is an important driving force of the HIV epidemic. This is contrasted to assortative sexual mixing, ie, sexual partnerships between individuals of similar HIV risk, which would not foster the spread of HIV.

Intergenerational sex, where young women have sex with older men (more than 5 years age difference), is one of the different forms of dissortative sex. Young people, who have had less exposure to sex, are sexually connected with adults, whose HIV infection rates are likely to be higher.

The mechanisms by which inter-generational sex may facilitate HIV transmission are as follows: there is likely to be significant power differentials when the ages of the partners are so much different; condoms are less likely to be used in these relationships; likelihood of HIV discordancy at start of relationship likely to be high.

Research on intergenerational sex suggested that all intergenerational sex is associated with power imbalances, no condom use, manipulation, poverty and the sheer need for economic survival. While such factors may be at play in many intergenerational partnerships, exceptions do exist. Nkosana and Rosenthal’s qualitative research showed that some relationship between young girls and older men were associated with desire for pleasure, enjoyment and sense of equal partnership by the younger partner ( 34 ). However, young women involved in such kind of relationship may fail to appreciate the precarious nature of such relationships.

High risk intergenerational sex may also occur when older men, who know they are infected with HIV, seek unprotected sex with younger women or children ( 35 , 36 ). In South Africa, and many parts of southern Africa, there is a belief that having sex with a virgin is a cure for HIV. The extent to which such practices could be driving the HIV epidemic in South Africa is likely to be small though.

Alcohol and other recreational drug use

There is growing research interest in the role of alcohol and other recreational drugs in the spread of HIV in South Africa ( 37 , 38 ).The growth of the number of taverns and shebeens in poor peri-urban South Africa and its associated lifestyles are a consequence of segregation and discrimination during the Apartheid era. Such places, located largely in the poor neighborhoods, also very often associated with sex work ( 39 ).

Violence against women and rape

Violence against women, and especially rape, are significant problems in South Africa, where it is estimated that more than one woman is raped each second. Jewkes and Abrahams ( 40 ) report that representative community-based surveys have found that among women in the 17-48 age group, there were 2070 such incidents of rape per 100 000 women per year. Compared to consensual sex, rape is a rare event. However, the fact that rape is unsolicited, and is likely to be unsafe (no condom use, tears), makes it an important aspect of the HIV transmission in South Africa. The risk of HIV infection may be minimized by the provision of drug prophylaxis, which may not be readily available, especially in remote rural parts of South Africa ( 41 , 42 ).

Lack of male circumcision

From the mid 1980s, evidence has been accumulating that male circumcision could be associated with lower transmission of HIV ( 43 - 47 ). Countries with high prevalence of circumcision are also likely to have lower prevalence of HIV infection ( 48 , 49 ). However, most of these studies were cross-sectional and, therefore, could not estimate causation ( 50 ). Therefore, randomized controlled trials were conducted in Orange Farm (South Africa), Kisumu (Kenya), and Rakai (Uganda). These studies have demonstrated a protective efficacy of circumcision against HIV acquisition among men of about 60% ( 51 - 53 ).

South Africa’s male circumcision prevalence is below 30% and the majority of men were traditionally circumcised as a rite of passage from childhood into adulthood ( 54 ). Circumcision protects against HIV acquisition potentially through many mechanisms, as has been discussed elsewhere ( 55 ). In brief however, the reduced surface area of potential exposure to HIV, the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases (other than HIV), and the keratinization of the glans penis are all postulated as mechanisms through which circumcision prevents HIV transmission among men. In a community where men are less likely to be infected with HIV (as a consequence of circumcision) women are also likely not to be infected. The fact that a small percent of men in South Africa is circumcised ( 56 ) could at least in part explain the high HIV prevalence among women.

There is already interest to provide circumcision to adolescents and young men in South Africa in order to prevent HIV transmission. Rennie et al ( 57 ) have discussed the operational and ethical issues that may need to be considered in such a scaling-up. These issues include the age of circumcision, consent and assent issues, safety of the procedure within a health system with limited supplies and human resources, and stigma that may be associated with circumcision.

“Dry sex” preference

In many parts of Southern Africa, women insert detergents, antiseptic powders into their vagina in order to make them “dry” or “tight” ( 58 , 59 ). In these settings, it is believed that a highly lubricated vagina diminishes sexual pleasure during insertive penile vaginal sex. A dry vagina or a dry vagina with herbal particles is likely to suffer lesions during sex which may either facilitate transmission of HIV or acquisition of the virus.

While the practice may be blamed for the spread of HIV, its prevalence is not known. Much of the data on this practice has come from studies with small sample size and among selected groups such as sex workers.

The role of AIDS “denialists”

The claim by South Africa’s president Thabo Mbeki and his minister for health that HIV is not the cause of AIDS may have derailed many prevention, treatment, care, and support efforts by various stakeholders in South Africa ( 60 , 61 ). It was not until the South African government lost in courts that significant progress started to be made in the country ( 62 , 63 ).

To what extent the government’s response to HIV has facilitated the rapid spread of infection or not can be debated. This is because South Africa has continued to attract both domestic and international resources in the fight against the virus. There is no doubt, though, that AIDS treatment programs, including the prevention of mother to child transmission through the use of nevirapine, were all delayed because of the government’s reluctance. How this may have affected HIV infection prevalence estimates among young women is probably not known.

Education and HIV infection